“I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them…our so-called stealing of this country was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

“I don’t feel we did wrong in taking this great country away from them…our so-called stealing of this country was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

— Actor John Wayne, 1971

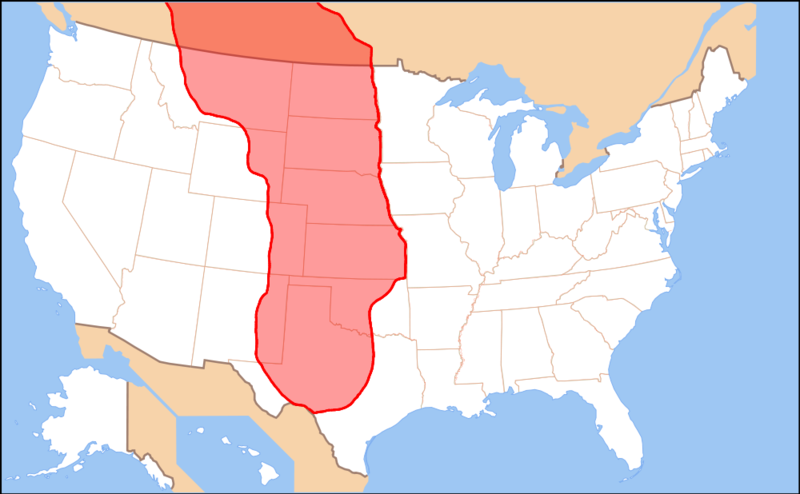

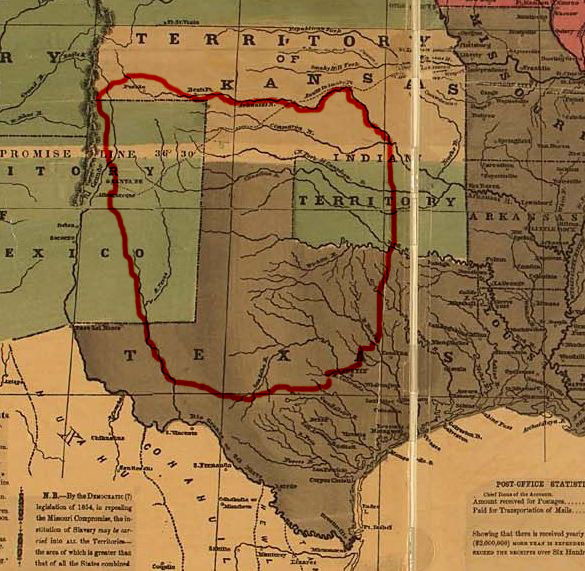

What follows won’t begin to do justice to the people that lived on the Great Plains for centuries, but we’ll at least take a deeper look at what actually happened than “The Duke” did in the quote above, as that’s a low bar to cross. First, some geographic background. The last part of the United States settled by Euro-Americans wasn’t the West Coast but rather the Great Plains, stretching from the Texas Panhandle up through western Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, eastern Colorado, and the western Dakotas into eastern Montana — between the mountains to the west and fertile prairies to the east. This was wide-open, unforgiving terrain with little water, harsh winters, hot summers, tornadoes, and grasshopper plagues. Today’s farmers can tap into the massive underground Ogallala Aquifer, at least for another 20-50 years, but no one is sure what will become of the area when the reservoir runs dry. Scientists think this region and other parts of the West have been plagued by “mega-droughts” intermittently throughout history, wreaking havoc even on Indigenous Americans with low populations and lower water use. Today, the region’s overall population has been declining since the 1930s, in spite of a temporary surge around the Bakken Oil Boom. Some small towns in Kansas have been abandoned altogether.

The Plains’ population was likewise sparse compared to most of the country after the Civil War. Before farmers and ranchers fenced in their homesteads with barbed wire, “cattle herders” or “drovers” drove cows across the range to railheads in towns like Abilene and Dodge City, Kansas, from where they rode to slaughter in Omaha or Chicago. Herders slept on the ground for three months straight in one set of clothes, working in all kinds of weather at $1/day for Whites, 75¢ for Blacks, and 50¢ for Hispanics, whose ancestors invented ranching in Iberia. Most only did it once. At the time, cowboy was usually a derogatory term for outlaw, rustler, or bandit, used in newspaper propaganda to stigmatize drovers/herders who had reputations for letting off steam in railhead towns that were, in turn, trying to attract more “civilized” clientele. As the West got mythologized later in novels like Owen Wister’s The Virginian (1902), cowboys folded into either lawmen or outlaws, but herders were just workers and most didn’t carry handguns. They also owed their existence and survival to corporate employers and the federal government, despite being co-opted in the 20th century as symbols of self-reliance.

Former enslaved workers (Freedman) called Exodusters, in reference to the area’s dust and the Biblical book of Exodus, staked out precarious homesteads on the Great Plains. To overcome concerns about the Plains’ dryness, land speculators pushed the pseudo-scientific theory that plowing released moisture back into the air that would return as rain. “Rain follows the plough!” was their sales pitch. White Soddies built mud huts and busted sod to eke out a hardscrabble living while millions of buffalo grazed under the big sky. Unlike other parts of the country, Euro-Americans on the Plains didn’t hugely outnumber the Native Americans around them in the late 19th century.

The traditional Plains Indians they encountered who hunted buffalo with guns on horseback weren’t really that traditional. Guns and horses didn’t exist in pre-Columbian America — horses had gone extinct thousands of years before — and many of the tribes that inhabited the Plains were pushed out of hunting grounds around the Great Lakes only a few generations before. Spanish conquistadors re-introduced horses to mainland North American in the early 16th century, as we saw in Chapter 1. Writer N. Scott Momaday described the transition among Kiowas on the southern Plains:

About the time of the Pequod War [in 17th-century New England], the Kiowa and the horse came simultaneously upon the southern plains. Then for a hundred years and more the Kiowa and the horse were one. The horse exerted a crucial influence upon virtually every aspect of Kiowa culture. It brought about a revolution. From the pre-horse culture the Kiowas brought only a nomadism and a mythology; the horse brought a new and material way of life. The Kiowa pulled up the roots which had always held him to the ground. He was given the means to prevail against distance. For the first time he could move beyond the limits of his human strength, of his vision, even of his former dreams. No longer was it necessary to stalk the herds, to construct traps, and to carry the meat of the kill on foot. With the horse the Kiowa could acquire enough food in one day to last him many months. He could transport his possessions at will and with only a fraction of his former time and effort.

On the northern Plains of Montana, Mandan hunted buffalo without horses and guns for centuries before Whites or Great Lakes tribes arrived. Mandan and Blackfeet herded bison through drive lanes of rocks and brush over cliffs, where other hunters waited with clubs and spears. This technique was called a buffalo jump.

Americans moved into Midwestern prairie states in the 1830s-40’s but then interest shifted to the Far West with the opening of the Oregon Trail, the Mormon Trek, and California Gold Rush before the Civil War. The Plains were too dry to easily yield crops and inhabited by formidable tribes that blocked white settlement. As we saw in Chapter 16, early maps of the area referred to the Great American Desert as being almost uninhabitable.

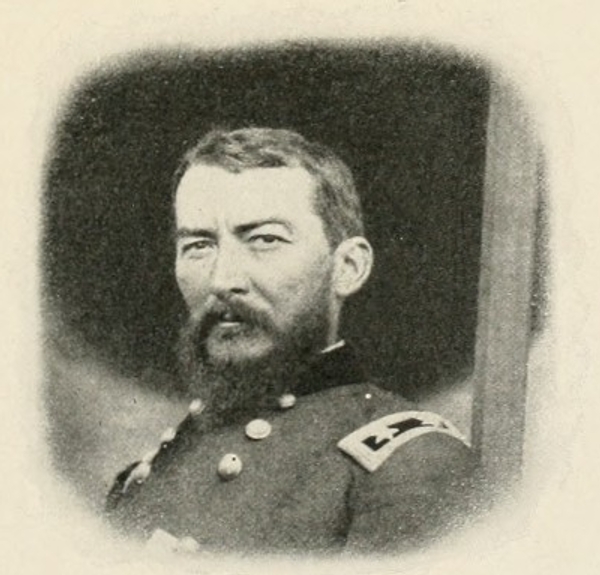

The Plains were the last area in the Lower 48 where Indigenous Americans lived independently before being forced onto reservations. When you hear people talk about Indian Wars in American history, they’re usually referring to warfare on the Plains during and after the Civil War, starting with the Dakota War of 1862 through the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. The same Union Army that fought Confederates was fighting a simultaneous war against Plains Indians, and even employed the same total war tactics used in W.T. Sherman’s March, Philip Sheridan’s (Shenandoah) Valley Campaigns, and U.S. Grant’s Siege of Vicksburg. Sherman and Sheridan both fought out west after the Civil War while Grant oversaw Indian affairs as president from 1869-1877. Their decimation of Plains tribes was every bit as brutal as that of the Spanish in the Caribbean, Russians in Alaska, and colonial and national governments elsewhere in the U.S. and Canada.

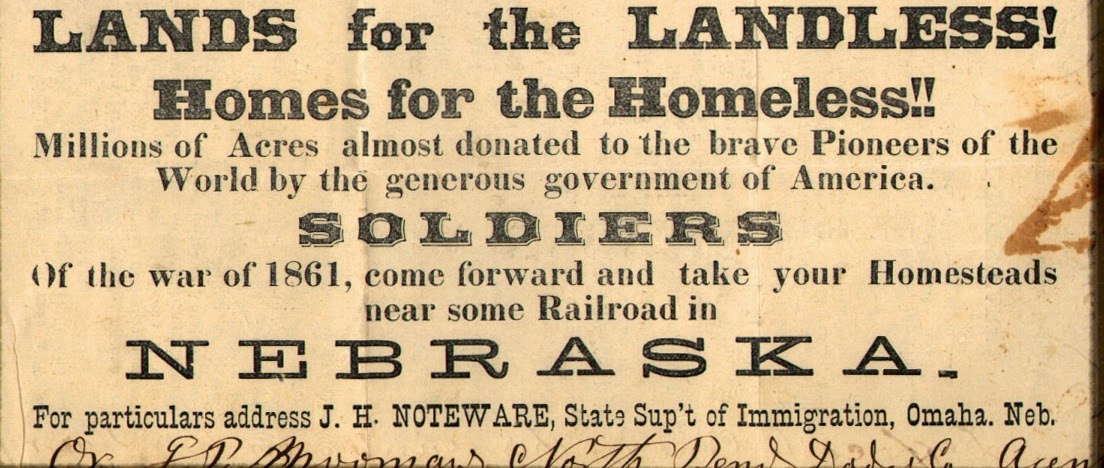

On the Southern Plains, Comanche rode roughshod over anyone and everyone, be they Whites or other Native Americans, in and around territory the Spanish called Comancheria, the southeastern border of which included Austin. By the 1850s, the ruckus over slavery in Kansas impeded white settlement. But, without Southerners in Congress during the Civil War, the Union government promoted western expansion, giving away land to farmers with the Homestead Act of 1862 and, through the Morrill Act, land grants for states in the Midwest and Plains to build colleges, including many of those today ending in “state.” Kiowa journalist Tristan Ahtone traced how the government took land from Native Americans to give to railroads and these colleges, with even eastern schools like MIT using scrip from these land cessions to build their campuses. The government often swapped such land for broken future promises of water rights or healthcare.

In 1864, Lincoln set aside land at Yosemite, California, setting the stage for the country’s first national park at Yellowstone in 1872. Lincoln came into office seeing three regions that he wanted to merge into one nation: the Union, California, and the South. Consequently, his army multi-tasked by bringing the West under Union control as they fought the Confederacy. He also rightly feared that the Confederacy would encroach on western territory if they won, which they seemed to be doing as of 1862.

Abraham Lincoln and 1860s Republicans synthesized rugged individualism with the idea of the collective. Lincoln believed in self-reliance, but self-reliance within a society that provided opportunities for hard workers through subsidized land, public schools, railroads, etc. Individual rights, in general, have always relied on governments for framework. In that regard, Lincoln-era Republicans traced to Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists of the 1790s and antebellum Whigs’ American System (Chapter 13). The Homestead Act wasn’t a free handout; less than 50% of recipients cultivated the land well enough to earn their grant. In rare cases, Exodusters won land grants.

“People Escaping from the Indian massacre of 1862 in Minnesota, at Dinner on a Prairie,” Photo by Adrian J. Ebell, Library of Congress

After the Civil War, renewed emigration from Europe, especially Germany and Scandinavia, fueled settlement of the upper Midwest and Plains. The government loaned money and ceded massive tracts of land to railroad companies who, supposedly, couldn’t afford real estate down payments up front. The government gave away around 10% of the country to either settlers or railroads, including more land to railroad companies than the entire square mileage of New England. This often resulted in a checkerboarding land-use pattern because the government gave alternate one square-mile plots to settlers or the railroads. The five transcontinental railroads still in existence today all came into being between the Civil War and 1900. These projects, along with the discovery of gold in the northern Plains and Rockies, forced the final showdown between the U.S. and remaining independent tribes.

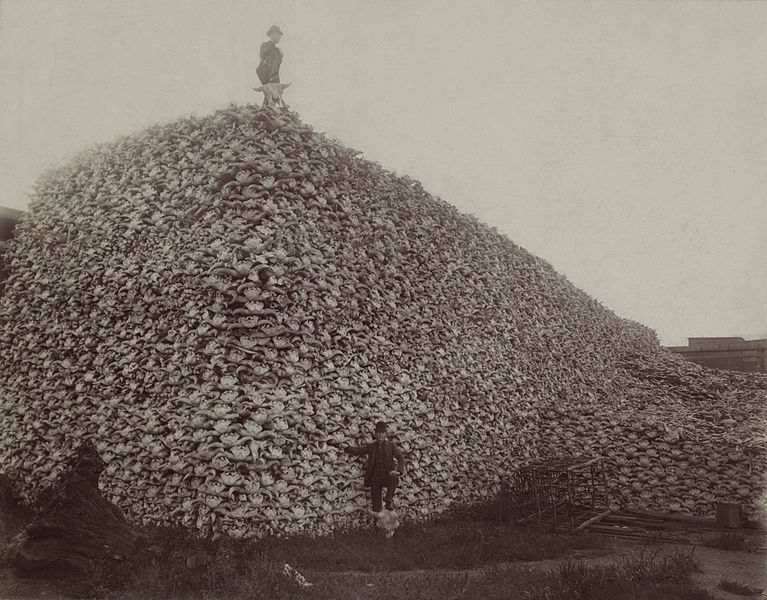

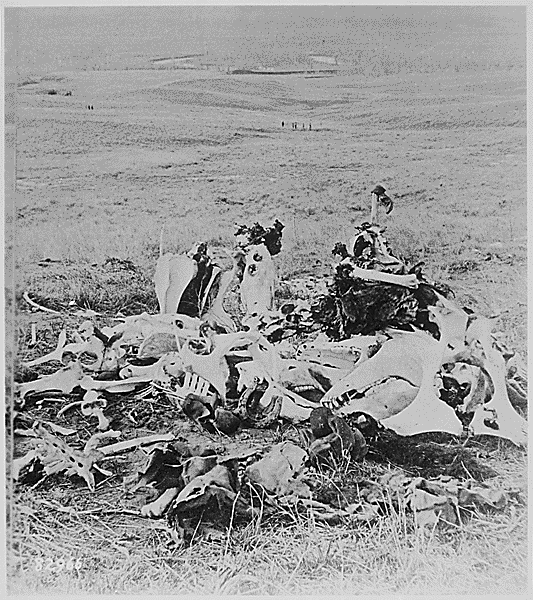

Native Americans interfered with railroad construction, killing workers. And the buffalo Indians counted on for survival (for meat, robes, tools, etc.) interfered with the iron horse (trains) by grazing on tracks. Consequently, the government wanted to push Native Americans to either side of the transcontinental routes, moving them onto reservations. Killing buffalo in droves served the dual purpose of clearing the tracks and undermining indigenous economies. Army soldiers killed buffalo and passenger trains even stopped amidst herds so travelers could pull out their rifles and fire away. When they were done, they moved on, leaving the carcasses behind. So many buffalo died that, at times, their rotting flesh could be smelled throughout the region.

There were numerous forced marches onto reservations similar to the Trail of Tears back east in the 1830s (Chapter 13). Ponca of (modern) Nebraska’s Niobrara River Valley were sent to a reservation that the government accidentally ceded to other tribes in an 1868 Treaty. Then the Army marched them to northern Oklahoma with many dying along the way. When their chief, Standing Bear, returned to Nebraska to press their case, authorities arrested and imprisoned him. He sued with the help of local pro bono attorneys and, in Standing Bear v. Crook (1879), a district court ruled for the first time in history that Native Americans have legal rights in the U.S. It was an important first step toward citizenship, attained for Indigenous Americans nationwide in 1924.

Southwestern tribes presented a similar obstacle to Whites. In a forced migration similar to the Ponca’s called the Long Walk, an army led by Kit Carson and American-allied tribes pushed Navajos onto the Bosque Redondo reservation near the Four Corners area of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. East of there, the combined effect of diseases (mainly cholera and smallpox) and more Whites moving into Texas weakened the once mighty Comanches. As the Civil War was going on back east, the Army headquartered at Ft. Bowie was fighting Apaches to clear western mail routes.

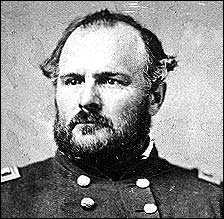

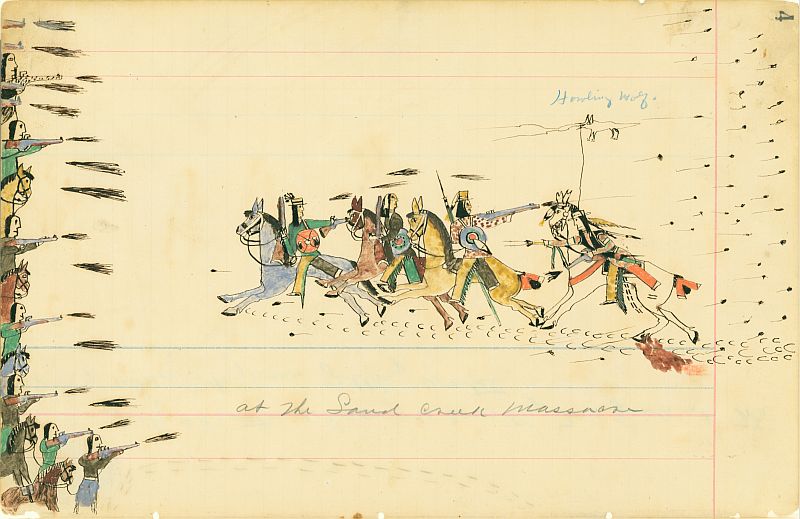

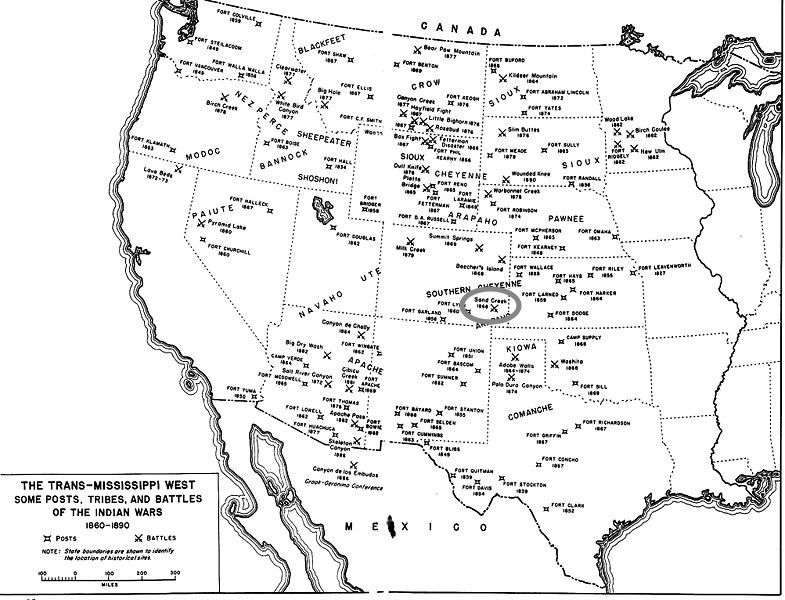

In Colorado, relations between Native Americans and the government worsened after Colonel John Chivington — part-time Methodist preacher, Freemason, and abolitionist — led a massacre of innocent Arapahos and Cheyennes at Sand Creek and Smoky Hill River, who had already agreed to move onto a reservation. Colorado’s governor wanted all Native Americans gone to appeal to white settlers and, when local press harassed Chivington’s men for not having killed any Indians, he burnished his reputation by ordering them to “kill Cheyenne whenever and wherever found.” As he callously put it in his call to arms, “Kill ‘em all, big and small, nits make lice.” Wearing a peace medal President Abraham Lincoln had personally given him in Washington in 1863, Cheyenne Chief Lean Bear confidently rode out to greet Chivington but died before he hit the ground when the colonel’s men shot him. After the smoke cleared, soldiers rode over to pump him full of more bullets. Lincoln’s words proved prophetic, as he’d warned Lean Bear that “his children (Army officers) might terrorize Western tribes and ignore peace treaties, because it wasn’t always possible for any father to have his children do precisely as he wishes them to do.” Hardest hit was Black Kettle’s Wutapai band who, on the bad advice of other U.S. soldiers, flew an American flag with a white surrender flag under it over their village, adjacent to an American fort.

Denver feted Chivington’s men with a victory parade in which they hung male and female genitalia and other body parts around their necks and carried torn-out fetuses — the “nits” if you will — as souvenirs. These macabre trophies hung for months at the Apollo Theater and in local saloons. Not all Americans approved of the attacks and the government court-martialed Chivington. Here’s what Kit Carson had to say:

Jis to think of that dog Chivington and his dirty hounds, up thar at Sand Creek. His men shot down squaws, and blew the brains out of little innocent children. You call sich soldiers Christians, do ye? And Indians savages? What der yer spose our Heavenly Father, who made both them and us, thinks of these things? I tell you what, I don’t like a hostile red skin any more than you do. And when they are hostile, I’ve fought ’em, hard as any man. But I never yet drew a bead on a squaw or papoose, and I despise the man who would.

The Sand Creek Massacre destroyed whatever prior trust existed between Plains Indians and the American government, decimated the Southern Cheyenne, and, counter-productive to American intentions, discouraged many Native Americans from moving onto reservations since they naturally feared they’d be killed, with their women and children mutilated, if they surrendered. And many of the very tribal elders who advocated for peace were murdered in the massacre. Historian Ari Kelman researched how living descendants, local residents, and the National Park Service worked together to construct an appropriate memorial. The government commemorated the location (in SE Colorado below) as a National Historic Site in 2007. The Park Service describes the events there as “chaotic, horrific, tumultuous and bloody.”

The next year, 1865, the Army attacked tribes in the Powder River Basin of the Wyoming and Montana territories after a gold discovery. In retaliation, Oglala Lakota of the Sioux Nation, led by Red Cloud, lured and ambushed U.S. troops in the Fetterman Massacre of 1866, near Fort Phil Kearney. They beheaded, disemboweled, scalped, and castrated all troops except for one young bugler, whom they respectfully covered with a buffalo robe after his futile attempts to fend off attacks with his horn. Such mutilations were as traditional among Native Americans as they were among Europeans and colonial Americans. Plains tribes marked their prey distinctively.

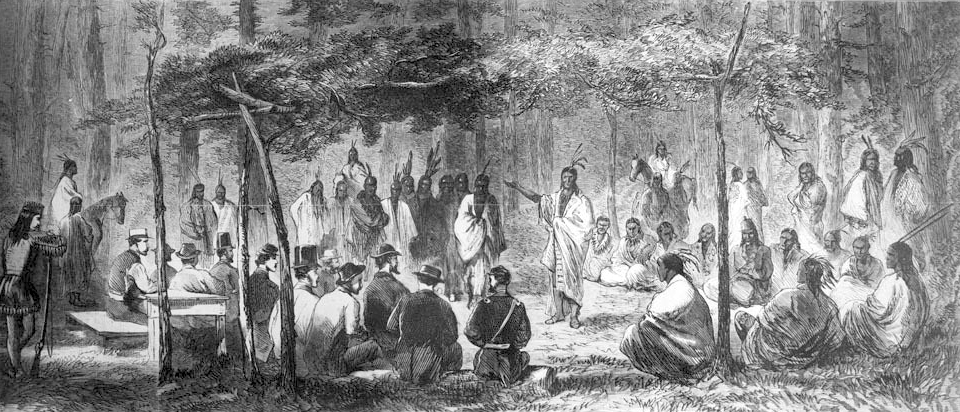

Council at Medicine Lodge Creek w. Kiowa & Comanche Peoples, J. Howland in Harper’s Weekly, 1867, WikiCommons

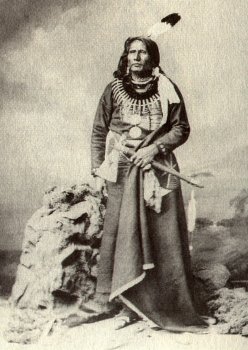

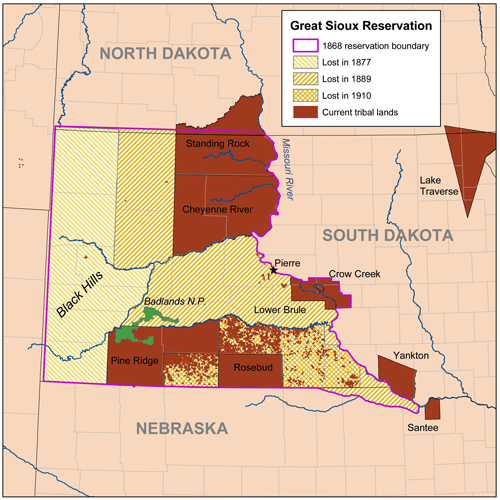

In the resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), the vast lands granted to the major Plains tribes in the 1851 Treaty of the same name shrunk considerably, ostensibly to ensure civilization. The government moved many Native Americans to reservations in Oklahoma via the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty and the desolate Black Hills of the Dakota Territory, where European Americans figured they’d never have any reason to settle. Lakotas occupied the Black Hills after pushing out Kiowas and Crows in the 18th century. In the words of historian Peter Cozzens, Lakotas valued the Ȟe Sápa or Paha Sapa (“hills that are black”) not for their mystic aura but rather as their “meat locker, a game reserve to be tapped in times of hunger.” A less defined unceded territory spread further to the south and west, where Lakotas and Cheyennes could still hunt. Holdouts led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse refused to move onto the reservations, condemning those who took wasichus (Whites) up on their offers of free food and supplies. Others decided to accept the deal while they had the chance since their future prospects looked dim anyway, and they appreciated the four promised years’ worth of meat and flour.

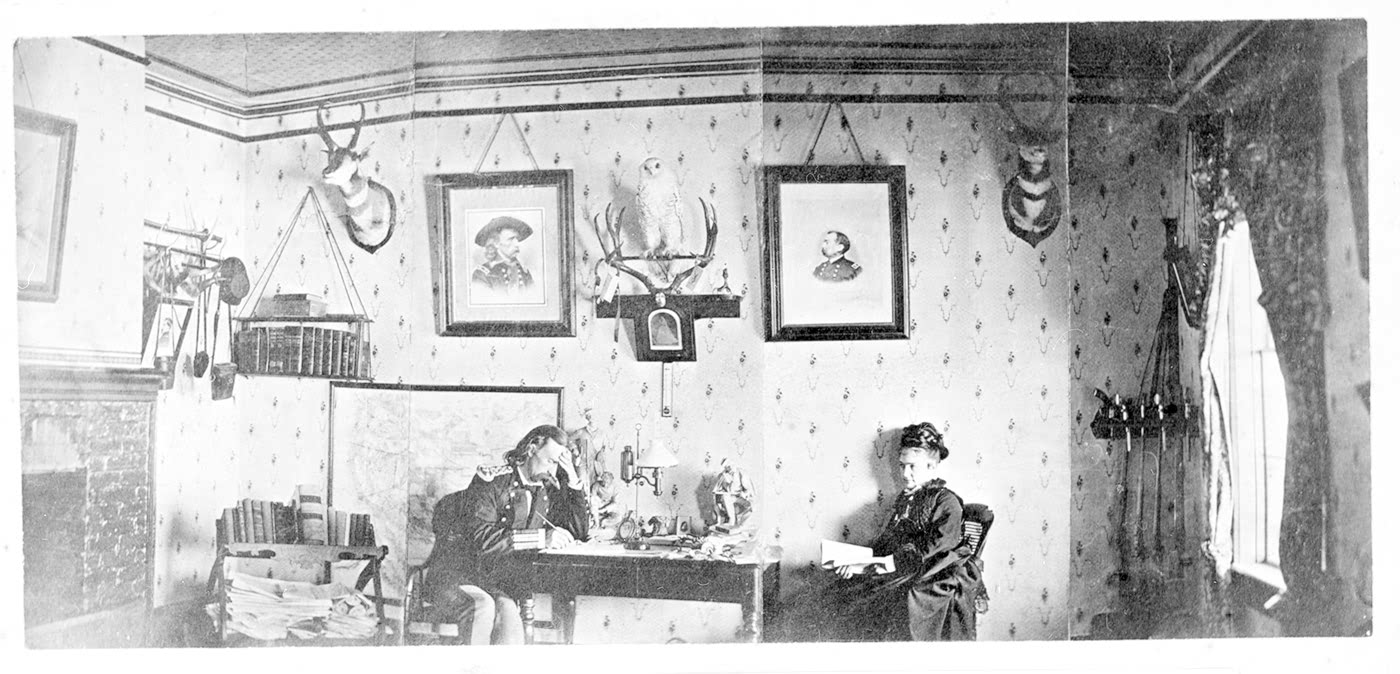

In 1870, the Army massacred ~ 200 Piegan Blackfeet (mainly women, elderly, and children already suffering from smallpox) in the Marias Massacre in the Montana Territory. This attack was so unjustified that most of public back east opposed it and U.S. Grant’s administration tried to reform the Bureau of Indian Affairs. But then the Army discovered gold along the northwestern border of the Black Hills in 1874 and the government asked the Northern Sioux, as they called Lakotas, if they could buy the territory back (Sioux is a French corruption of “Nadouessioux,” an Ojibwe word meaning snake, or enemy). President Ulysses S. Grant came to office in 1869 promising peace in the West, conceding that “our dealings with the Indians properly lay us open to charges of cruelty and swindling.” And Grant could plausibly tell the Lakota delegation that visited the White House in 1875 that he and the relatively small military were powerless to keep miners out of the Black Hills. This is the setting of HBO’s Deadwood (2004-06), for readers familiar with that series. However, documents in the Library of Congress and U.S. Military Academy Library demonstrate how gold motivated Grant to condone war in 1876 behind the back of Congress and the public and undermine the Fort Laramie Treaty. He cherry-picked a hawkish inner cabal that circumvented the normal chain-of-command, avoiding those like W.T. Sherman who’d signed the Laramie Treaty and wrote Grant to complain of “whites looking for gold [who] kill Indians just as they would kill bears and pay no regard for treaties.” Grant didn’t invite Sherman into his inner circle, though he included two of Sherman’s hawkish subordinates, Phil Sheridan and George Crook, the defendant in the aforementioned Standing Bear case.

The secret commission asked the “wild” (non-reservation) Lakotas if the U.S. could purchase mining rights knowing they’d said no, then ordered them to the reservation by an impossibly short mid-winter deadline, all the while fabricating fake complaints against them. They knew that horses were weak from hunger in the winter and couldn’t travel to summits. Conveniently, independent Lakotas refused Grant’s request that they move onto the reservation, with Sitting Bull purportedly picking up a pile of dirt and telling a messenger, “I do not want to sell or lease any land to the government — not even as much as this.” Grant, who’d been so critical years earlier of President Polk’s manufactured casus belli against Mexico in south Texas (Chapter 17), now had his wish: Lakotas were “provoking conflict” and the U.S. had no choice but to defend itself against the “untamable” Indians, the same ones that told Chicago Inter Ocean field reporter William Curtis that they had no desire to fight. Renewed war ensued that included perhaps the most ignominious battle defeat in U.S. history, but ultimately the demise of free Lakotas by 1877.

In 1876, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Oglala, and Lakota (Hunkpapa) warriors wiped out an entire U.S. battalion led by the recklessly courageous and egotistical George Armstrong Custer. Custer’s men found gold in 1874 along the Little Bighorn River in southeastern Montana and were clearing the area of Indigenous Americans to make way for settlers and miners. Custer wrote his brother-in-law that his foray into the Black Hills would “open a rich vein of wealth.” But as the Helena Daily Herald reported on July 5th, 1876, the day after the country’s 100th birthday, they were “cut to pieces…in a terrible fight.” The rout shocked Americans back east, most of whom had never even seen an Indian and took it for granted that the Army had mostly subdued them. Now, in the midst of the nation’s centennial celebration in Philadelphia, came word that the dashing, long-haired Lt. Col. Custer — perhaps the most famous non-major general from the Civil War and leader of the heroic Michigan Wolverine Calvary’s charge at Gettysburg — was dead along with all his men. He’d accidentally led his 7th Cavalry into a larger-than-expected encampment led by Sitting Bull and defended by Crazy Horse and other warriors.

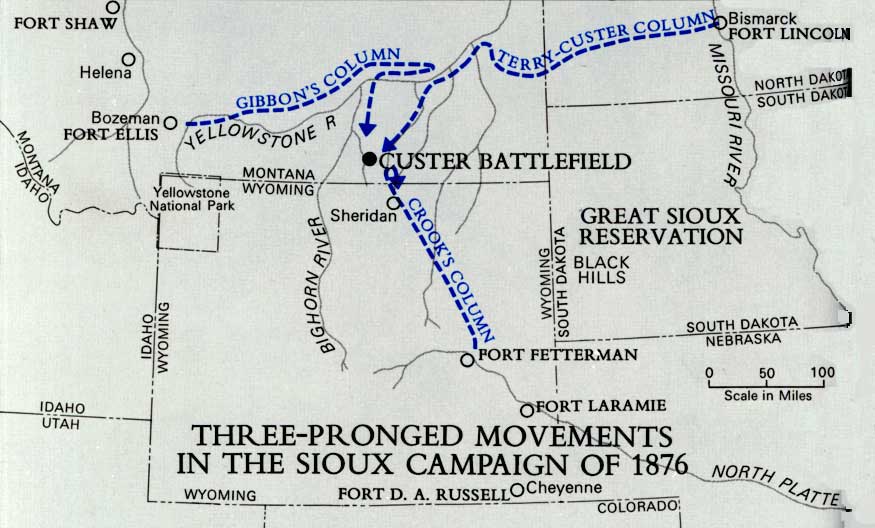

The Army’s attacks on Lakotas and Cheyenne had been brutal leading up to that, with infants left to freeze to death, and this group wasn’t about to allow a repeat of Sand Creek, Custer’s 1868 attack at the Washita River in Oklahoma, or the 1870 Marias Massacre of Piegan Blackfeet in Montana. Custer had come to expect that warriors would run to the rescue of their women and children before fighting and he complained that he would prefer them to “stand and fight.” This time, he stumbled into a bigger camp (6-7k) and there were plenty of warriors who stood and fought (1.5k) while others stayed back with the families. That was partly because they’d been emboldened by Sitting Bull’s vision of victory during his Sun Dance days earlier. Custer’s men arrived before three other columns led by Crook, Alfred Terry, and John Gibbon that they were supposed to rendezvous with near the headwaters of the Little Bighorn River (above). Along with Marcus Reno’s three companies, they decided to fight anyway, fearing that the Indians would scatter before Terry’s larger force arrived and not realizing initially that they were outnumbered 7:1.

Unlike many of the earlier cavalry attacks, the warriors were well armed this time. They’d traded enough buffalo robes to settlers in previous years to amass an arsenal of Winchester and Henry rifles. Unlike the single-shot Springfield 1873s used by the 7th Cavalry, these repeating rifles could fire off magazines of twelve to sixteen rounds before having to be reloaded. A skilled soldier was lucky to shoot that many rounds in a minute with the Springfield and, when it jammed, he could only use it as a club. In this case, Native Americans had the same advantage Union troops enjoyed on Sherman’s March through Georgia during the Civil War. The result was the annihilation of 268 men, or 1% of the entire U.S. military, that had trimmed down considerably after the Civil War. Ignoring Sitting Bull’s warning to respect the victims, vengeful warriors who had lost their families in earlier attacks disfigured the soldiers so that they’d not enjoy the afterlife, battering their brains out and strewing their insides across the field. There are conflicting reports as to what happened to Custer’s body. One story is that Sioux warriors preserved Custer because two Cheyenne women told them he’d had a brief relationship the prior year with a woman in their tribe, and he was therefore considered a relative. Another is that warriors denigrated Custer’s remains like the rest, including puncturing his eardrums because he wouldn’t listen. Custer had a Native American scout, Hunkpapa Sioux Bloody Knife, who also died at Little Bighorn.

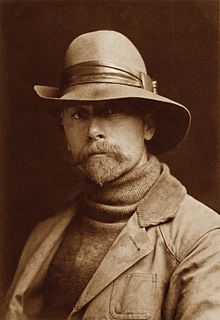

Several Crows, enemies of the Sioux, also fought with Custer. Years later, they told ethnographer and photographer Edward Curtis that, when Custer saw Reno’s men being routed early in the battle, he dismounted and watched, despite protests on the Crows’ part to go help. Custer, a bitter enemy of Reno, said, “No. Let them fight. There will be plenty of fighting left for us to do.” Suffice it to say, Curtis’s revisionism didn’t go over well with turn-of-the-century Americans, including his patron Theodore Roosevelt (then president), who scolded Curtis in a letter.

The Lakota’s Battle of the Greasy Grass — known to Whites as the Battle of Little Bighorn or, in common lore, as Custer’s Last Stand — was the U.S. Army’s worst defeat at the hands of Indigenous Americans since the Battle of Wabash (St. Clair’s Defeat) in 1791. Yet, it was probably the worst thing that could’ve happened to Plains tribes. The U.S. doubled down its efforts to control holdouts who hadn’t moved to reservations. They moved the Northern Cheyenne to Fort Reno in the Oklahoma Territory to join the Southern Cheyenne, but they broke out and marched north through Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Montana, fighting the Army and settlers along the way. They ended up on a reservation in Montana but lost half of their people during the Northern Cheyenne Exodus of 1878-79, later depicted in Mari Sandoz‘ 1953 novel Cheyenne Autumn and director John Ford’s 1964 western by that same name. The Army also dispatched more troops to the Plains and Northwest, where they captured fleeing Nez Perce just miles from the Canadian border and sent them to Oklahoma, where most of them died. In 1980, the Supreme Court awarded damages to Lakotas for their lost land, an unclaimed settlement now worth over a billion dollars with accrued interest. They hope someday to reclaim the Black Hills instead.

Inspired by Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka, some Native Americans engaged in ghost dances meant to encourage others to revive their traditional economies and not rely on white trade. They hoped tribes would disavow coffee, sugar, and bacon, for instance, or other items they relied on Whites for. Ghost dances offended settlers who saw them as an affront to Christianity and American power. In 1890, the Army mowed down buffalo and dancers led by Lakota chief Spotted Elk at Wounded Knee, South Dakota with Hotchkiss guns and buried them in a mass grave. Wounded Knee marked the end of 19th-century Indian resistance on the Plains. Adding insult to injury, reservations shrank in size. In 1889, the government opened up much of Oklahoma, originally set aside as one large reservation, in one of the great land rushes in history. Indian territories had already shrunk some in Oklahoma in the Reconstruction Treaties, to punish tribes for their alliances with Confederates during the Civil War. In 1889, Sooner or Boomer squatters rushed across the border to claim more land before it officially opened. In Chapter 13 we saw how the Supreme Court respected Indian treaties, in that case with Cherokees in Georgia; but in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock (1903), SCOTUS ruled that Congress had the right to abrogate (break) treaties with Oklahoma Indians, including the forenamed Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867.

Like other wars, those on the Great Plains included cultural warfare, not just military and economic. That included destroying native religions. After suffering defeat at Palo Duro Canyon in the Texas Panhandle and being led on a forced march to the Old Stone Corral prison in Oklahoma, the Kiowas’ Tai-me sun dance suffered the same fate as the ghost dances. Writer Momaday described the tragedy: “Before the dance could begin, a company of soldiers rode out from Fort Sill under orders to disperse the tribe. Forbidden without cause the central act of their faith, having seen the wild herds slaughtered and left to rot upon the ground, the Kiowas backed away forever from the medicine tree. That was July 20, 1890, at the great bend of the Washita. My grandmother was there. Without bitterness, and for as long as she lived, she bore a vision of deicide.”

Indigenous Americans were faced with the choice of either staying on reservations or assimilating into mainstream American society, though they lacked basic rights of citizenship such as voting until 1924. Many that left reservations had trouble adjusting, especially those in big cities surrounded by noise, lights, and crowded streets. Alcoholism and poverty plagued many that left or stayed on reservations. The Dawes Act of 1887 allowed Native Americans to take farmland and gain citizenship if they chose, but that farmland was carved out of the reservations, making them yet smaller. Academics studied Indigenous Americans hoping to document native cultures before they evaporated altogether. Zunis adopted one of these researchers, Frank Hamilton Cushing of the Smithsonian Institute, who became known as Medicine Flower.

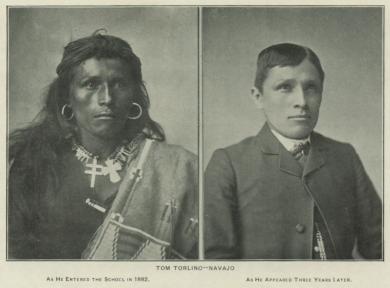

Well-intentioned Whites provided tuition for some Native Americans to attend off-reservation boarding schools designed to drum indigenous culture out of them and convert them to white dress, behavior, and thinking. At the most famous, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, its founder Richard Henry Pratt’s chilling motto was “kill the Indian and save the man.” Despite their disregard, and even contempt, for the students’ native culture and occasional physical abuse, many students received decent educations and job training and often did better than their reservation counterparts staying sober.

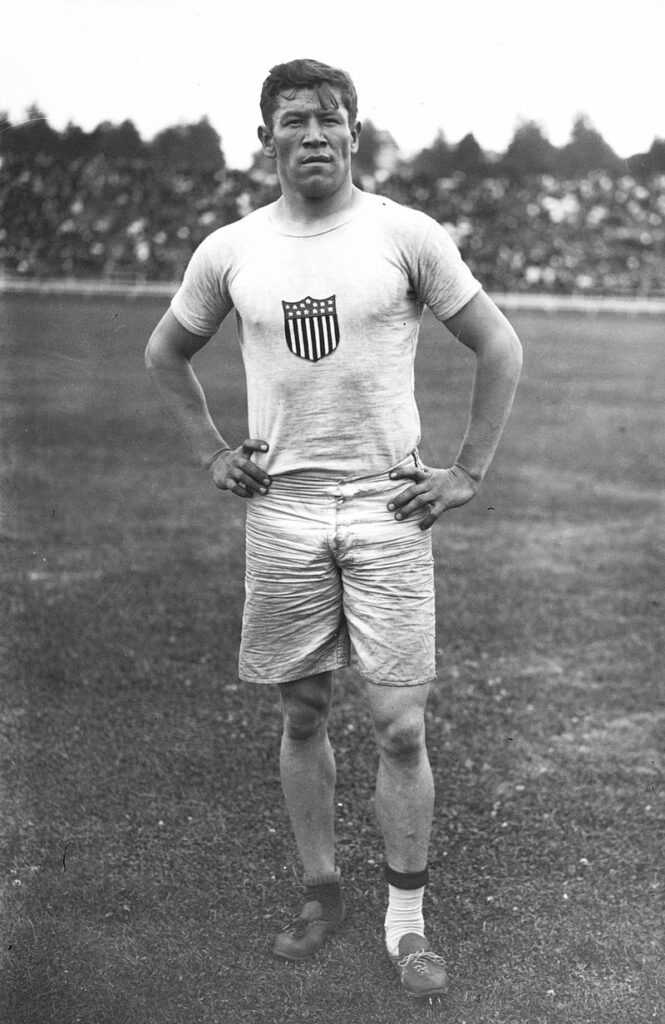

Carlisle had a great football team led by one of the best athletes of all time, Jim Thorpe, or Wa-tho-Huk (path lit by lightning), who was Sac & Fox, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Menominee, English and French. In the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, he won gold medals in the decathlon and classic pentathlon (with a score 3x higher than the runner-up), but had his medals stripped when duplicitous officials discovered he’d played pro baseball, violating his amateur status. Stockholm was sandwiched between two college football seasons that would’ve won back-to-back Heismans, had that trophy existed. Thorpe then spent six years playing major league baseball and launched pro football as its first superstar and president of what became the NFL (National Football League). Yet, he wasn’t a U.S. citizen as this unfolded since no Native Americans were until 1924. They won voting rights on a state-by-state basis between 1924 and 1957.

When authorities celebrated the Olympic accomplishments of Thorpe and Hopi distance runner Louis Tewanima, also from Carlisle, their compliments were condescending. Gushing with pride as looked at Tewanima, Carlisle’s superintendent Moses Friedman boasted, “His people had been giving the government much trouble and were opposed to progress and education…they came with long hair and some of them with earrings. They were pagans and opposed to education and American civilization…I wanted you to know of his advancement in civilization and as a man.” Turning to Thorpe, he said, “By your achievement, you have immeasurably improved your race. By your victory, you have inspired your people to live a cleaner, healthier, and more vigorous life.”

Before the Plains were even settled, entrepreneurs were already packaging and selling romanticized versions of the Old West to eastern American and European audiences in the form of dime novels and circuses such as Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. Not long after, early Hollywood movies filmed in the deserts outside Los Angeles mythologized the West even before many of its original heroes had died. Wyatt Earp lived to see movies about himself. Men like Cody and “Wild Bill” Hickok had spent time in the West themselves as cattle herders, scouts, lawmen, trappers, Indian fighters, etc.

The relative openness and lawlessness of Western mythology attracted audiences to carnivals that reenacted famous scenes. Along with rodeo events and sharpshooters like Annie Oakley, these shows employed Native Americans, too. Apache Chief Geronimo, who’d surrendered to U.S. forces in Arizona in 1886, played a dancing bear and autographed photos to survive. Sitting Bull, who’d been at the real Little Big Horn, reenacted Custer’s Last Stand for audiences in New York, London, and Paris before being shot by the Army at Standing Rock Reservation in 1890 for evading arrest. As detailed in David Maraniss’ biography Path Lit By Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe,” the Sac & Fox athlete was the last of symbolic Native Americans glorified by white audiences, following Geronimo, Sitting Bull, Iron Tail (Oglala Lakota), and Crazy Horse, “some defanged, all romanticized, exaggerated yet diminished at the same time.”

In 2016, U.S. Army veterans led by Wes Clark, Jr., the son of a former NATO Supreme Commander (above), attended the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota. In an emotional ceremony at its casino, they bowed to Sioux tribal leaders to atone for the pain caused to Native Americans by the U.S. military. Clark offered a much different take than actor John Wayne’s self-serving subjectivity at the top of the chapter:

Many of us, me particularly, are from the units that have hurt you over the many years. We came. We fought you. We took your land. We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents [Mt. Rushmore] onto your sacred mountain. Then we took still more land and then we took your children and then we tried to take your language and we tried to eliminate your language that God gave you, and the Creator gave you. We didn’t respect you, we polluted your Earth, we’ve hurt you in so many ways but we’ve come to say that we are sorry. We are at your service and we beg for your forgiveness.

Leonard Crow Dog offered forgiveness and plead for world peace, adding “we do not own the land, the land owns us.”

Optional Reading, Viewing & Listening:

Tatanka Iyotake: Reimagining Sitting Bull (NEH)

The William F. Cody Archive (NEH)

Peter Cozzens, “Grant’s Uncivil War,” (Smithsonian Magazine, 11.16)

B. Lynn Ingram, “The West Without Water: What Can Past Droughts Tell Us About Tomorrow?” (Origins)

This American Life: Little War On The Prairie (WBEZ-PRX)