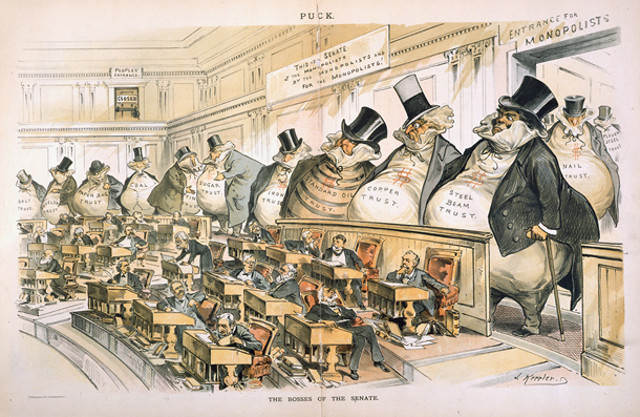

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, America continued to drift in a conservative direction economically as unions weakened, workers worked longer hours for less overtime pay, Wall Street banks grew larger in relation to the rest of the “real” economy, and class lines hardened to the point that America had less upward mobility than European countries. Multinational firms transcended borders after the Cold War, cashing in on capitalism’s global victory and winning the legal right in 2010 to unlimited “dark money” PAC 501(c)(4) campaign donations to buy politicians and judges (as “citizens” corporations were exercising their “free speech”). Religiously, Christian Fundamentalism spread from the Bible Belt across the country and, politically, the Reagan Revolution kept liberals on the defensive. Taxes and faith in government stayed low, with only a tenth as much spent on infrastructure as fifty years earlier (0.3% of GDP vs. 3%) and congressional approval ratings dropped to all-time lows as corporate lobbies brazenly bought off legislators. Ronald Reagan emboldened conservatives in the same way that FDR’s New Deal emboldened liberals a half-century earlier. And, just as FDR would’ve found some of LBJ’s Great Society too liberal, Reagan wouldn’t be conservative enough today to run as a Republican.

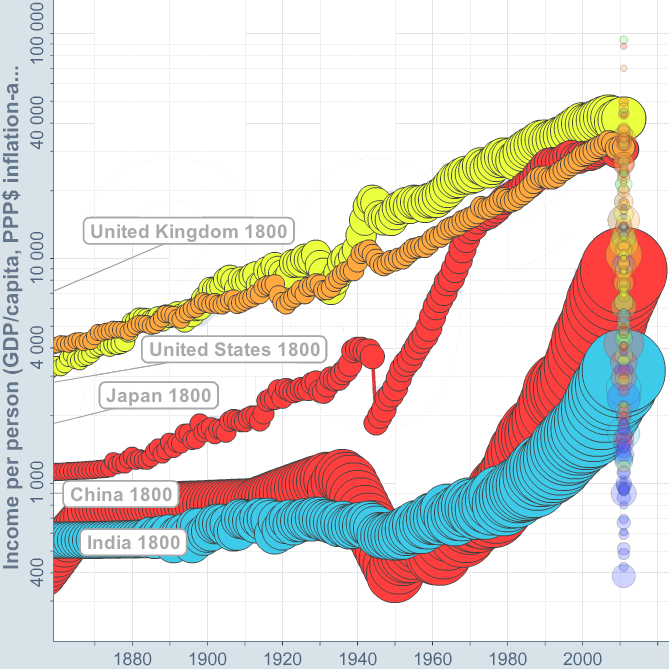

By the mid-2010s, Western countries were shifting away from the traditional left-right economic spectrum that had defined politics for a century toward a dichotomy between those who embraced globalization and the postwar Western alliance (NATO, EU, etc.) and those with a more nationalist viewpoint represented by Donald Trump in the U.S. and Eurosceptics Theresa May in Britain, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Viktor Orbán in Hungary, Marine Le Pen in France, Lech and Jaroslaw Kaczynski in Poland, Beppe Grillo in Italy, and Jörg Meuthen in Germany. Jair Bolsonaro modeled himself after Trump in Brazil and billionaire prime minister Andrej Babiš styled himself the “Czech Donald Trump.” Trump strategist Steve Bannon called Switzerland’s Christoph Blocher — who’d kept Switzerland out of the European Union long before Britain’s “Brexit” — “Trump before Trump.” United in their opposition to unchecked immigration and globalization, these nationalists transcended the left-right economic spectrum. Scottish nationalist and First Minister Nicola Sturgeon was a democratic socialist and Trump was a registered Democrat until 2009. Yet the new globalist-nationalist divide also resulted partly from traditional economic tensions insofar as it tapped into middle-class economic concerns. The issues that defined the old, overlapping economic spectrum were still more important than ever, as gains from increased productivity flowed almost exclusively to the wealthy, frustrating the middle classes and making it hard for the right to argue the merits of trickle-down economics convincingly to a broad GOP coalition. These 2012 numbers from Harvard and Duke’s business schools, published in the left-leaning Mother Jones, explain why:

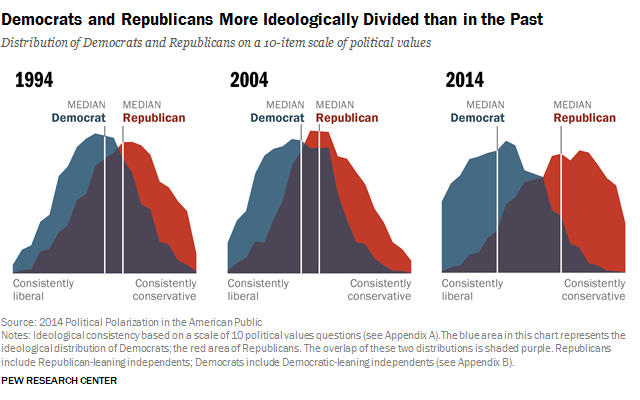

With the world’s top 1% now worth more than the bottom 99%, it’s likely that liberal parties will pursue increasingly socialist means to redistribute wealth (e.g. “Jobs-for-All” with $15 minimum wage, right) while conservative parties steer the conversation away from economics, or at least discourage “class warfare.” In American domestic politics after the Reagan Revolution, the GOP moved to the right and the Democrats followed by moving part way to the right on economics but not culture, and the gap between the two parties grew because of factors we covered in the last half of the previous chapter: media fragmentation, enhanced gerrymandering, and uncompromising, rights-based party strategies, along with the Monica Lewinsky scandal and contested 2000 Election in the optional section. Other factors magnifying partisanship were the end of the Cold War (removing a unifying cause) and greater (not less) transparency on Capitol Hill, leading to fewer backroom compromises outside the view of partisan lobbyists and voters. All this amplified the partisanship that’s been a mainstay of American democracy, creating near dysfunctional Gridlock in Congress worsened by increased parliamentary filibustering that can require 60% super-majorities on Senate bills. Some gridlock is a healthy and natural result of the Constitution’s system of checks-and-balances, though New Yorkers invented the actual term gridlock in the early 1970s to describe traffic. However, too much gridlock disrupts the compromises that keep the political system functioning. For instance, the bipartisan Simpson-Boles plan to balance the budget long-term with small compromises on both sides never even made it out of committee and likely wouldn’t have passed if it did. Meanwhile, among voters, rifts opened in the combustible 1960s evolved and hardened into the “culture wars” of the next half-century.

With the world’s top 1% now worth more than the bottom 99%, it’s likely that liberal parties will pursue increasingly socialist means to redistribute wealth (e.g. “Jobs-for-All” with $15 minimum wage, right) while conservative parties steer the conversation away from economics, or at least discourage “class warfare.” In American domestic politics after the Reagan Revolution, the GOP moved to the right and the Democrats followed by moving part way to the right on economics but not culture, and the gap between the two parties grew because of factors we covered in the last half of the previous chapter: media fragmentation, enhanced gerrymandering, and uncompromising, rights-based party strategies, along with the Monica Lewinsky scandal and contested 2000 Election in the optional section. Other factors magnifying partisanship were the end of the Cold War (removing a unifying cause) and greater (not less) transparency on Capitol Hill, leading to fewer backroom compromises outside the view of partisan lobbyists and voters. All this amplified the partisanship that’s been a mainstay of American democracy, creating near dysfunctional Gridlock in Congress worsened by increased parliamentary filibustering that can require 60% super-majorities on Senate bills. Some gridlock is a healthy and natural result of the Constitution’s system of checks-and-balances, though New Yorkers invented the actual term gridlock in the early 1970s to describe traffic. However, too much gridlock disrupts the compromises that keep the political system functioning. For instance, the bipartisan Simpson-Boles plan to balance the budget long-term with small compromises on both sides never even made it out of committee and likely wouldn’t have passed if it did. Meanwhile, among voters, rifts opened in the combustible 1960s evolved and hardened into the “culture wars” of the next half-century.

Complicating and dovetailing with these culture wars was a libertarian push back against regulations on guns, drugs, sexual orientation, and gambling. Taking advantage of an omission/loophole in the 1934 National Firearms Act — requiring FBI background checks, national database registration, fingerprinting, photo, and fees for fully automatic machine guns, silencers (until recently), hand grenades, missiles, bombs, poison gas, short-barreled rifles, and sawed-off shotguns — and expiration of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (1994-2004), gun lobbies staked out a place among civilians for semi-automatic assault rifles like the AR-15, with some marketing even aimed at children (technically their parents). An ATF-approved kit could purportedly “bump-fire” them into fully-automatic machine guns. Despite no evidence that the U.S. was poised to invade itself or confiscate everyone’s weapons, the National Rifle Association (NRA) promoted assault rifles as a way for citizens to raise arms “against a tyrannical government run amok” (unsurprisingly, the Constitution [Article III, Section 3] forbids as treasonous citizens levying war against the United States). NRA president Wayne LaPierre thought that to ban assault rifles or bump stocks, even for 18-21 year-olds, would lead the U.S. down the path to socialism and argued for better enforcement of existing laws. At five million members, the NRA represents a fairly small percentage of hunters (~ 17 million) and gun owners (~ 1/3 of American adults). The idea the Second Amendment protects against any gun regulation at all is new to American history, dating from the Smith & Wesson smart gun controversy of 2000.

Complicating and dovetailing with these culture wars was a libertarian push back against regulations on guns, drugs, sexual orientation, and gambling. Taking advantage of an omission/loophole in the 1934 National Firearms Act — requiring FBI background checks, national database registration, fingerprinting, photo, and fees for fully automatic machine guns, silencers (until recently), hand grenades, missiles, bombs, poison gas, short-barreled rifles, and sawed-off shotguns — and expiration of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (1994-2004), gun lobbies staked out a place among civilians for semi-automatic assault rifles like the AR-15, with some marketing even aimed at children (technically their parents). An ATF-approved kit could purportedly “bump-fire” them into fully-automatic machine guns. Despite no evidence that the U.S. was poised to invade itself or confiscate everyone’s weapons, the National Rifle Association (NRA) promoted assault rifles as a way for citizens to raise arms “against a tyrannical government run amok” (unsurprisingly, the Constitution [Article III, Section 3] forbids as treasonous citizens levying war against the United States). NRA president Wayne LaPierre thought that to ban assault rifles or bump stocks, even for 18-21 year-olds, would lead the U.S. down the path to socialism and argued for better enforcement of existing laws. At five million members, the NRA represents a fairly small percentage of hunters (~ 17 million) and gun owners (~ 1/3 of American adults). The idea the Second Amendment protects against any gun regulation at all is new to American history, dating from the Smith & Wesson smart gun controversy of 2000.

Law enforcement was outgunned by protesters in Nevada’s Cliven Bundy Standoff (4.14) and Charlottesville’s Unite the Right Rally (8.17) as citizens combined the Second Amendment right to bear arms with the First Amendment right to free speech and assembly, though in neither case did protesters open fire. Current interpretations of the First and Second Amendments, in other words, were on a collision course in open carry states like Texas without special event restrictions. While overall crime rates, including gun-related violence, fell in the U.S. in the early 21st century, killers used assault rifles in mass shootings in Aurora (2012), Newton (2012), San Bernardino (2015), Orlando (2016), Dallas (2016), Las Vegas (2017), Sutherland Springs, Texas (2017), and Parkland, Florida (2018). Bump kits allowed assassins like Stephen Paddock in Las Vegas to fire off 400-800 rounds per minute and Congress is currently debating whether or not to outlaw them.

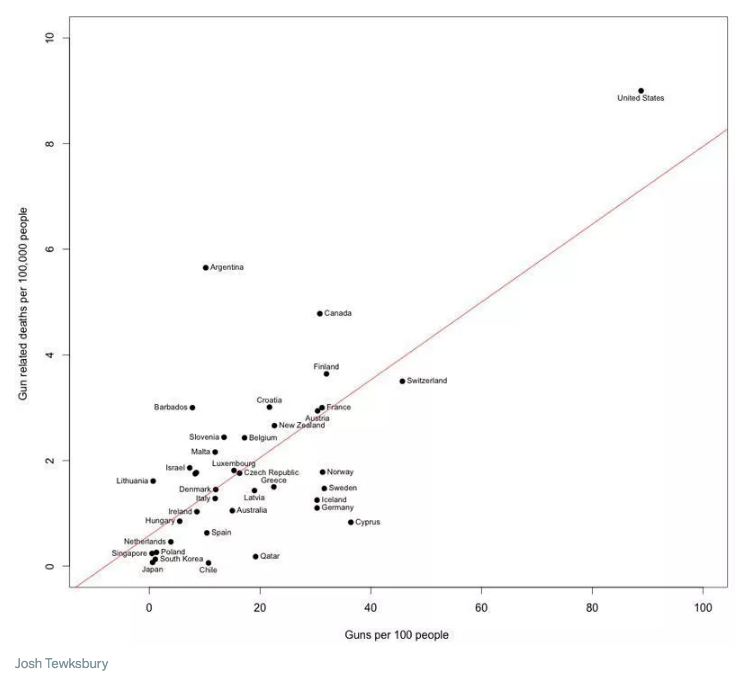

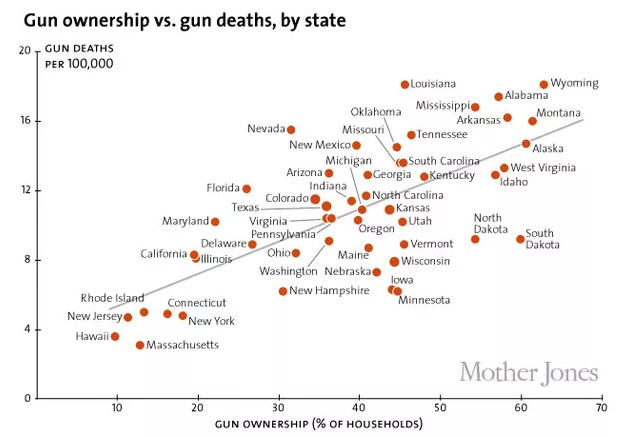

Americans remained divided on guns, with control advocates pointing out the ownership correlation to murder (and suicide) by country and state, while pro-gun lobbies stressed the need for more guns for protection amidst the mass shootings. In 2015, Governor Greg Abbott admonished Texans in a Tweet® for not buying more guns, embarrassed that they’d fallen behind California for a #2 ranking. If the respective sides of the debate shared anything, it was a common concern for safety; they just had opposing views on how to attain safety. This graph charted other points of agreement circa 2017. In “Guns & the Soul of America,” conservative columnist David Brooks interprets guns as being not just for protection or hunting but also a “proxy for larger issues” in the culture war, with guns as “identity markers” for freedom, self-reliance, toughness, responsibility, and controlling one’s own destiny in a post-industrial world.

While the U.S. embraced military weapons for civilians and the NRA and its legislators pushed to re-legalize silencers and loosen background checks, the U.S. simultaneously went in a more liberal but likewise libertarian direction on many social issues, including legalization of marijuana in some states and same-sex marriage everywhere (Chapter 17). If Americans today aren’t more divided than usual, they are at least better sorted by those who stand to gain by magnifying their disagreements (e.g. cable TV manufactured a previously non-existent “War on Christmas”). And they’ve sorted themselves better than ever, often into conservative rural areas and liberal cities, reminiscent of the rural-urban divides of the 1920s. As we saw in the previous chapter’s section on gerrymandering, this geographic segregation results in partisan districts of red conservatives and blue liberals, with interspersed purple that defy categorization (most Americans live in suburbs). The fragmented and partisan media encourages and profits from animosity between citizens, selling more advertising and “clickbait” than they would if politicians cooperated and citizens respectfully disagreed over meaningful issues. A 1960 poll showed that fewer than 5% of Republicans or Democrats cared whether their children married someone from the other party; a 2010 Cass Sunstein study found those numbers had reached 49% among Republicans and 33% among Democrats. This trend might not continue, as polls show that the actual brides and grooms (Millennials) are less rigid ideologically than their parents. In 2014, Pew research showed that 68% of Republican or Republican-leaning young adults identified their political orientation as liberal or mixed and similar polls show some young Democrats identifying as conservative (it’s also possible that many young people don’t know what liberal or conservative mean).

While the U.S. embraced military weapons for civilians and the NRA and its legislators pushed to re-legalize silencers and loosen background checks, the U.S. simultaneously went in a more liberal but likewise libertarian direction on many social issues, including legalization of marijuana in some states and same-sex marriage everywhere (Chapter 17). If Americans today aren’t more divided than usual, they are at least better sorted by those who stand to gain by magnifying their disagreements (e.g. cable TV manufactured a previously non-existent “War on Christmas”). And they’ve sorted themselves better than ever, often into conservative rural areas and liberal cities, reminiscent of the rural-urban divides of the 1920s. As we saw in the previous chapter’s section on gerrymandering, this geographic segregation results in partisan districts of red conservatives and blue liberals, with interspersed purple that defy categorization (most Americans live in suburbs). The fragmented and partisan media encourages and profits from animosity between citizens, selling more advertising and “clickbait” than they would if politicians cooperated and citizens respectfully disagreed over meaningful issues. A 1960 poll showed that fewer than 5% of Republicans or Democrats cared whether their children married someone from the other party; a 2010 Cass Sunstein study found those numbers had reached 49% among Republicans and 33% among Democrats. This trend might not continue, as polls show that the actual brides and grooms (Millennials) are less rigid ideologically than their parents. In 2014, Pew research showed that 68% of Republican or Republican-leaning young adults identified their political orientation as liberal or mixed and similar polls show some young Democrats identifying as conservative (it’s also possible that many young people don’t know what liberal or conservative mean).

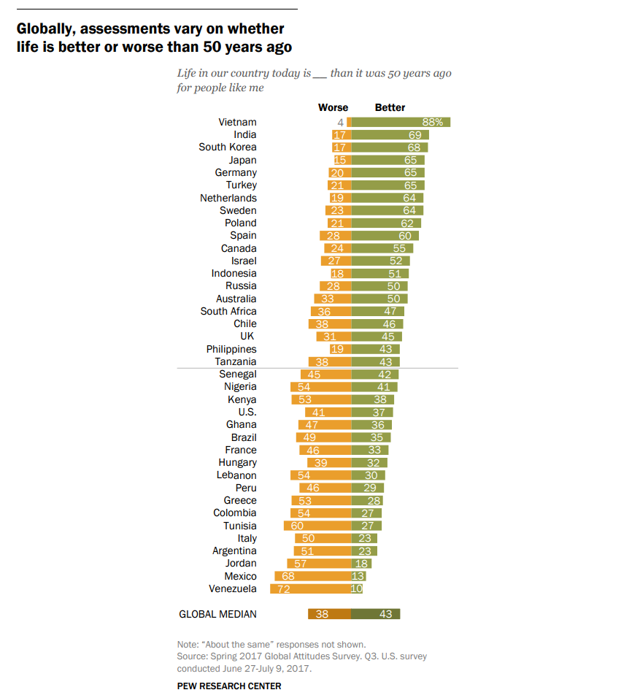

But more than ever, politicians struggled to please voters who disliked each other and, like children, were both defiant toward and dependent on government. As usual, voters also thought things were declining worse than they really were, even as many things were improving. Declinism, aside from being a nearly universal cognitive bias, also sells better, resulting in a situation where most people thought the country was going downhill while their local area was improving, just as they thought public schools were “broken” even though their own children’s’ public schools were good. Americans couldn’t agree on much, but many felt aggrieved and had “had enough” even if they weren’t well-informed enough to know what exactly they’d had enough of. And those that did know didn’t agree with each other. Amidst this hullabaloo, Tweeting®, and indignation — with nearly every imaginable demographic perceiving itself as “under siege” — historians hear echoes of earlier periods in American history. Large, diverse, free-speech democracies are noisy and contentious countries to live in as you’ve already seen from having read Chapters 1-20. Partisan media is a return to the 18th and 19th centuries, while today’s cultural rifts seem mild compared to more severe clashes in the Civil War era, 1920s, and 1960s-70’s, even if those eras weren’t saturated with as much media. In the early 21st century, hyperpartisanship and biased media complicated and clouded debates over globalization/trade, healthcare insurance, and high finance that would’ve been complicated enough to begin with. These are three primary areas we’ll cover below, with some brief economic background to start.

But more than ever, politicians struggled to please voters who disliked each other and, like children, were both defiant toward and dependent on government. As usual, voters also thought things were declining worse than they really were, even as many things were improving. Declinism, aside from being a nearly universal cognitive bias, also sells better, resulting in a situation where most people thought the country was going downhill while their local area was improving, just as they thought public schools were “broken” even though their own children’s’ public schools were good. Americans couldn’t agree on much, but many felt aggrieved and had “had enough” even if they weren’t well-informed enough to know what exactly they’d had enough of. And those that did know didn’t agree with each other. Amidst this hullabaloo, Tweeting®, and indignation — with nearly every imaginable demographic perceiving itself as “under siege” — historians hear echoes of earlier periods in American history. Large, diverse, free-speech democracies are noisy and contentious countries to live in as you’ve already seen from having read Chapters 1-20. Partisan media is a return to the 18th and 19th centuries, while today’s cultural rifts seem mild compared to more severe clashes in the Civil War era, 1920s, and 1960s-70’s, even if those eras weren’t saturated with as much media. In the early 21st century, hyperpartisanship and biased media complicated and clouded debates over globalization/trade, healthcare insurance, and high finance that would’ve been complicated enough to begin with. These are three primary areas we’ll cover below, with some brief economic background to start.

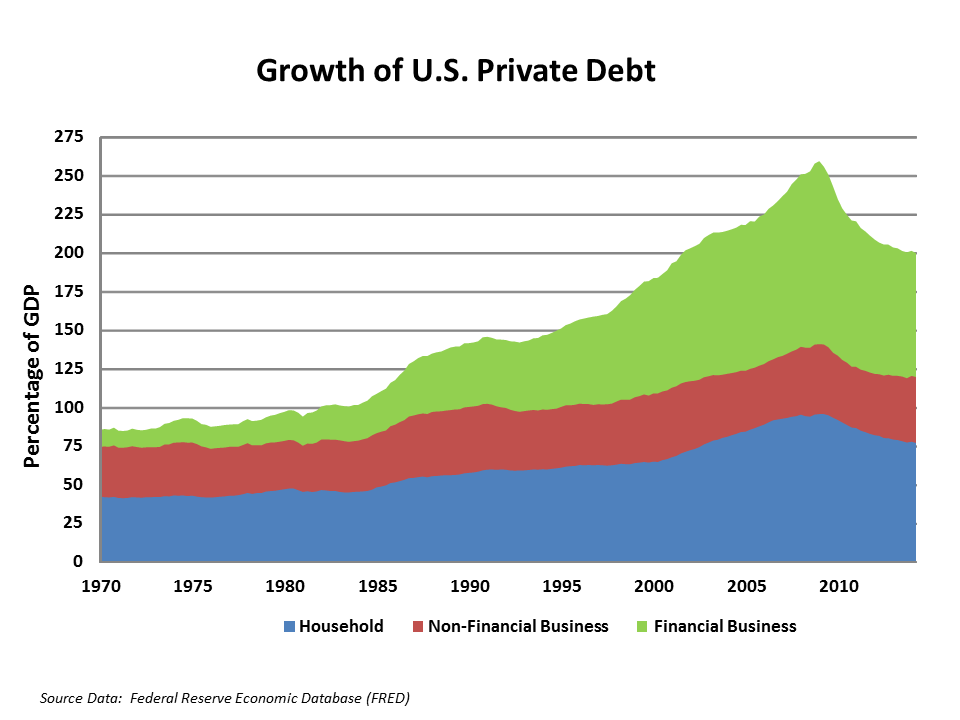

The American economy continued on a path toward increased globalization and automation that began long ago, with American labor competing directly against overseas workers and robots. Information technology assumed a dominant role in most Americans’ jobs and lives, as traditional manufacturing jobs were increasingly outsourced to cheaper labor markets or displaced by automation, compromising middle-class prosperity. Studies showed that more jobs were lost to automation (~85%) than outsourcing (~15%) even though the U.S. lost over 2 million jobs to Chinese manufacturing in the first decade of the 21st century. The verdict isn’t in but, proportionally, the digital age hasn’t yet translated into the domestic job growth that accompanied the steam engine, railroad, electricity, or internal combustion engine, and Wall Street’s expansion hasn’t been accompanied by growth in the “real economy.” In the information technology sector, Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon employ only 150k people between them — less than the total number of Americans entering the workforce each month. Unlike Sears in the 20th century, when you place an order with Amazon, the workers scurrying around the warehouse floor to fill it aren’t people on roller skates, they’re robots. Online retail increasingly replaces “brick-and-mortar” as malls close and For Lease signs pop up in strip malls. Automation and digitization have made businesses more efficient than ever and American manufacturing is stronger than naysayers realize — still the best in the world — but it provides fewer unskilled jobs. Efficiency is a two-edged sword: sometimes technology destroys jobs faster than it creates others. If automated trucks displace our country’s drivers over the next 10-20 years, it’s unlikely we’ll find another 1.7 million jobs for them overnight. It’s a tough labor market for people without at least some training past high school in college, a trade school, or the military, and robots are displacing white-collar and blue-collar workers alike. Yet, many jobs remain unfilled and high schools focusing on Career & Technical Education (CTE) are gaining traction to fill gaps. Despite increased economic productivity, wages have remained largely flat since the 1970s (relative to inflation) except for the wealthy. As they struggled to “keep up with the Joneses” or just pay bills, middle-class Americans borrowed against home equity and the average ratio of household debt-to-disposable income doubled between 1980 and 2015, despite still being relatively low by international standards.

Most likely, the dynamic American economy will adjust as it always has before. Karl Marx feared that steam would spell doom for human workers and John Maynard Keynes feared the same about fuel engines and electricity. A group of scientists lobbied Lyndon Johnson to curtail the development of computers. From employers’ standpoints or that of the free market, robots are more efficient than humans and they never complain, show up late, get sick, join unions, file discrimination suits, demand pensions, or health insurance, etc. So far, at least, these fears of being taken over by robots haven’t been realized on a massive scale, but automation has gained momentum since Marx and Keynes and is well on its way to posing a significant economic challenge. Still, for those with training, America’s job market remains healthy, with unemployment under 5% as of 2017. Humans are unlikely to go the way of the horse, partly because democratic societies have more power over robots than horses had over engines. But, unfortunately, the verdict isn’t in yet on whether the scientists who warned LBJ about computers were right. Hopefully, physicist Stephen Hawking and sci-fi writers are wrong about robots taking over.

Globalization: Pro & Con

Globalization didn’t start in the 20th century. The trend dates to the 15th century in terms of maritime trade and even earlier with overland routes like the Silk Road, and trade has always been a controversial and important part of American history. Free-trading colonial smugglers resented Britain’s restrictive, mercantilist zero-sum trade policies, protectionist Alexander Hamilton aimed to incubate America’s early industrial revolution with tariffs, and trade disputes and embargoes drove the U.S. into the War of 1812. Tariffs were a divisive enough issue between North and South in the 19th century to be a meaningful if secondary cause of the Civil War behind slavery. The U.S. then had high tariffs as the Industrial Revolution kicked into high gear after the Civil War (Chapter 1), but protectionism was widely interpreted as worsening the Great Depression after the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs (Chapter 8) and disparaged in British history because the Corn Laws (1815-1846) artificially raised food prices even as the poor went hungry, enriching landowners at the expense of the working classes and manufacturers.

When the U.S. and Britain set out to remake the world economy in their image after World War II and avoid more depressions (Chapter 13), they strove to encourage as much global trade as possible, though, in reality, there are virtually no countries that favor pure, unadulterated free trade. In America, both sides of nearly all major economic sectors have free trade and protectionist lobbies contributing to politicians. All democratic countries, including those that signed on to the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) in 1947, have voting workers back home demanding favoritism and each country looks to strike the best deals possible. France, for instance, qualified its inclusion in GATT with “cultural exceptions” to help its cinema compete with Hollywood imports and it maintains high agricultural tariffs. Translation: the upside of trade is great, but other countries can’t undermine farm-to-market La France profonde, or “deep France,” with cheap wine, bread, and cheese.

The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies on 19 July 1599, by Andries van Eertvelt, ca. 1610-20

By the early 1990’s, a near consensus of economists favored free trade and globalization threatened America’s working classes more than ever. Competition, outsourcing, and automation had weakened manufacturing labor relative to the rest of the economy, undercutting America’s postwar source of middle-class prosperity and upward mobility for blue-collar workers. Democrats had supported unions since the New Deal of the 1930s and they generally supported a Buy American protectionist platform to help workers, including trade restrictions and taxes (tariffs) on imports. They were the American version of the French farmers, in other words. Tariffs are the primary way to empower protectionism by discouraging free trade and favoring workers from one’s own country. This is more complicated than it might seem, though, because Buy American helps some workers and not others, especially those that work in industries that export and are susceptible to retaliatory tariffs from other countries (e.g. southern cotton exporters in the 19th century). Moreover, tariffs artificially raise prices for everyone. Buy American was also an awkward topic for mainstream Republicans because they fancied themselves as the more patriotic of the two parties but had mostly supported free trade over the years to boost corporate profits, and out of genuine belief that, on the whole, it helps workers.

However, tariffs and protectionism aren’t the only stories; there’s also the issue of how fair trade agreements are once countries agree to trade. They aren’t one-page contracts that declare: “No rules whatsoever. It’s a free-for-all” in large font above the picture of a handshake emblazoned over a Maersk container ship. They’re more like legal documents hundreds of pages long that make it difficult for the average citizen to parse out what they really include.

As we saw in the previous chapter, Bill Clinton’s embrace of free trade created a window of opportunity for Ross Perot to garner significant third-party support in 1992, and Hillary Clinton’s ongoing support of globalization along with mainstream Republicans partially explains Donald Trump’s appeal in 2016. Trump and his advisor Steve Bannon blasted through a door cracked open by Perot a quarter-century earlier, winning big in rural areas and the Rust Belt hit hard by globalization. This will continue to complicate traditional partisan alignments because politicians, by and large, are aware that globalization is probably a net gain for Americans, but there are economic pockets that have suffered a net loss. It’s tempting to appeal to those voters and those voters deserve to be heard.

As we saw in the previous chapter, Bill Clinton’s embrace of free trade created a window of opportunity for Ross Perot to garner significant third-party support in 1992, and Hillary Clinton’s ongoing support of globalization along with mainstream Republicans partially explains Donald Trump’s appeal in 2016. Trump and his advisor Steve Bannon blasted through a door cracked open by Perot a quarter-century earlier, winning big in rural areas and the Rust Belt hit hard by globalization. This will continue to complicate traditional partisan alignments because politicians, by and large, are aware that globalization is probably a net gain for Americans, but there are economic pockets that have suffered a net loss. It’s tempting to appeal to those voters and those voters deserve to be heard.

In 1992, Bill Clinton (D) wanted open trade borders with the United States’ neighbors to the north and south, Canada and Mexico, and, in 2000, he normalized trade relations with China. With the two major candidates, Clinton and George H.W. Bush, supporting free trade in 1992, that left the door open for a third-party candidate to focus on the outsourcing of labor. In his high-pitched Texan accent, Ross Perot quipped, “Do you hear that giant sucking sound? That’s your jobs leaving for Mexico.” He focused on Mexico because the issue at hand was whether the U.S., Canada, and Mexico would open their borders to each other for freer trade through NAFTA, the trilateral North American Free Trade Agreement (logo, left) that Ronald Reagan promoted in the 1980s. George H.W. Bush had agreed to NAFTA and Clinton, too, promised to push it through the Senate. Perot was wrong about huge numbers of jobs leaving for Mexico, but a lot of American manufacturing and customer-service jobs left for China, India, Vietnam, and other places where companies could pay low wages and pollute the environment without concern for American regulations. There was a giant sucking sound, all right; it just went mostly toward Asia instead of Mexico. Meanwhile, workers came north from Mexico and Central America for jobs that existing Americans either weren’t interested in or asked more for. ![]()

The pro-globalization argument is that free trade and outsourcing improve profit margins for American companies, boost American exports, and lower prices for consumers while providing higher wages and economic growth in developing countries. Free trade also offers consumers a wider range of products, ranging from BMWs and Samsung electronics to Harry Potter novels. You could drive a German BMW built in South Carolina or an American Ford or John Deere tractor built in Brazil. The smartphone in your pocket — or maybe you’re even reading this chapter on it — might come from South Korea but contain silicon in its central processor from China, cobalt in its rechargeable battery from the Congo, tantalum in its capacitors from Australia, copper in its circuitry from Chile or Mongolia, plastic in its frame from Saudi Arabian or North Dakotan petroleum, and software in its operating system from India or America. Another pro-globalization argument is that it creates more jobs than it destroys, as foreign companies who otherwise wouldn’t operate in the U.S. open plants and hire American workers. Honda, from Japan, builds almost all the cars and trucks it sells in America in America. In 2014, Silicon Valley-based Apple started making Mac Pros® at Singapore-based Flextronics in northwest Austin, creating 1500 jobs.

Opponents of globalization point out that American manufacturers are undersold, costing jobs and lowering wages as companies exploit and underpay foreign workers. Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus package included a Buy American provision and Donald Trump has advocated protective tariffs on dishwashers, solar panels, aluminum (10%), and steel (25%), along with tariffs on cars and car parts. At the close of the G-7 Summit in June 2018, Trump protested that Russia wasn’t invited and said of Western allies: “if they retaliate [against the tariffs], they’re making a mistake.”

Are such provisions beneficial to the American economy? For at least some workers, yes. When jobs go overseas, they lose theirs and labor unions lose their hard-earned bargaining power. But tariffs also keep prices artificially high on parts and products, costing other workers and consumers. With free trade, other workers make more money because their companies make more and, in theory, that “trickles down” to all of us “invisible beneficiaries.” More directly, it lowers prices. The U.S. could put a tariff on clothing, for instance, and that could save 135k textile jobs. But it would also raise the price of clothing, a key staple item, for 45 million Americans under the poverty line. The same is true of dishwashers, solar panels, aluminum, and steel. Globalization, in sum, is why your smartphone didn’t cost $2k but also why you can no longer make good union wages at the local plant with only a GED or high school diploma. New workers at General Electric’s plant in Louisville earn only half of what their predecessors did in the 1980s (adjusted for inflation).

Return to phones and electronics as an example of globalization’s pros and cons. We take for granted the lower price of products that importing and outsourcing make possible, and might not notice the increased productivity their devices allow for on the job, but we take notice that Americans aren’t employed assembling their products. Their workers are paid less than they would be in America and Apple lays off or adds 100k workers at a time in their Chinese facilities — mobilization on a scale the U.S. hasn’t seen since World War II. But cheap prices are a huge benefit. In Walmart’s case, their lower prices have curbed retail inflation in the U.S. over the last 35 years. (Walmart also saved money by selling bulk items, using barcodes, and coordinating logistics with suppliers — all now customary in retail.) Inflation is always uneven from sector to sector, though, just as the capacity of wages to rise along with inflation varies among occupations. With low inflation in retail and real dollar deflation in electronics and air travel, prices in housing, healthcare and education have risen over the last half-century relative to income. Free trade and outsourcing also help stock returns, because large American corporations not only can make things cheaper, they also do half of their own business overseas. The stock market helps the rich but also workers with company pensions and 401(k)’s that rely on growing a nest egg for retirement.

Most importantly, the U.S. exports too, and when it puts up protective tariffs other countries retaliate by taxing American goods. That happened most famously when the forenamed Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 worsened the Depression, stifling world trade. The shipping company pictured below, UPS, is based in Atlanta and it boosts America’s economy to have them doing business in Italy. No globalization; no UPS gondolas in Venice piloted by a gondolier checking his cheap smartphone. Globalization, then, is a complex issue with many pros and cons, some more visible than others. For a bare-bones look at the downside of globalization view the documentary Detrotopia (2013), that traces the decline of unionized labor and manufacturing in one Rust Belt city, or just look at the dilapidated shell of any abandoned mill across America. There aren’t any comparable documentaries concerning the upside of globalization since that’s harder to nail down. When it comes to what psychologist Daniel Kahneman called “fast and slow thinking,” we can see the downside of globalization in five seconds but might need five minutes to really think through the upside.

The 1992 campaign drew attention to globalization, as did the protests and riots at the 1999 World Trade Organization conference in Seattle. The WTO is the successor to GATT, part of the economic framework the West created after World War II, along with the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, to stimulate global capitalism. The rioters were protesting against the WTO’s free trade policy and the tendency of rich countries to lend money to emerging markets with strings attached, sometimes mandating weak environmental regulations and outlawing unions. Working conditions often seem harsh and exploitive from a western perspective even if the job represents a relatively good opportunity from the employee’s perspective. At the WTO riots, protesters threw bricks through the windows of chains like Starbuck’s that they saw as symbolizing globalization.

Today the outsourcing trend is reversing some, as more manufacturing jobs are returning to the U.S. Some companies, like General Electric, realize that they can monitor and improve on assembly-line efficiency better close to home, while other factors include the rising costs of shipping and increasing wages in countries like China and India, which are finally starting to approach that of non-unionized American labor. Yet, insourcing can also include foreign workers. Under H1-B non-immigrant visas, companies can hire temporary immigrants to do jobs for which there are no “qualified Americans.” Sometimes it’s true there aren’t qualified Americans, but other times that’s a farce. Due to lax oversight, some companies started to define qualified as will do the same job for less money. In 2016, Walt Disney (250 in Data Systems) and Southern California Edison (400 in IT) fired hundreds of American employees and even required them to train their replacements from India before picking up their final paycheck. Corporate America is currently lobbying Congress to loosen H1-B restrictions, while Donald Trump vowed to get rid of the H1-B Visa program in the 2016 campaign.

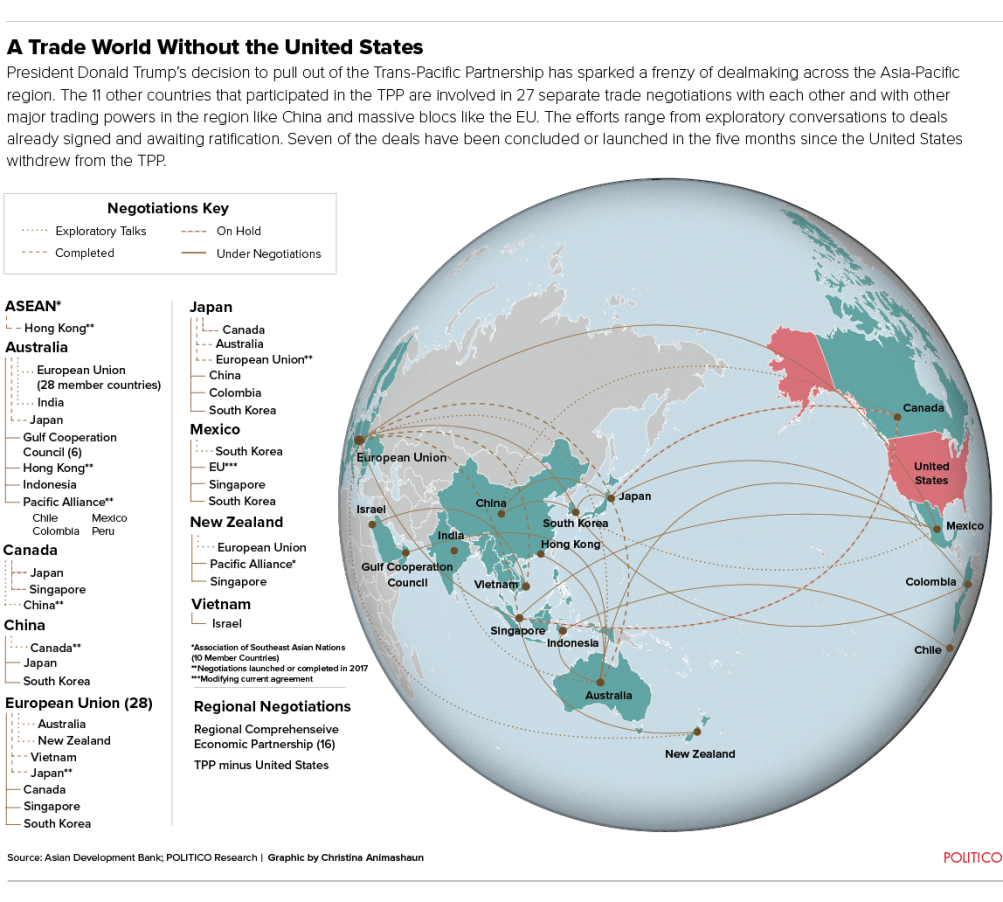

Globalization continues to be a controversial topic in American politics and will continue to be for the foreseeable future. The 2016 election saw two populist candidates, Trump (R) and Bernie Sanders (D), opposed to free trade and they even pressured Hillary Clinton (D) into taking an ambiguous stand against President Obama’s Trans-Pacific Partnership that loosens trade restrictions between NAFTA (U.S., Canada, Mexico) and twelve Pacific Rim countries that constitute 40% of the world economy. If not opposed to trade outright, Sanders and Trump at least wanted to rework the terms of the agreement, though it’s difficult in multilateral (multi-country) agreements to have each country go back to the drawing board because then the others might want to renegotiate and the whole process gets drawn out or falls apart. When Trump became president and pulled the U.S. out of the TPP, other nations started negotiating their own trade agreements. One point of TPP was to check China’s growing hegemony in Asia by striking agreements with its neighbors but not them. With America abandoning its place at the negotiating table, China has assumed a leadership role in brokering these negotiations (even when not participating directly), leveraging their influence as low-cost manufacturers.

American farmers that export meat, grain, wine, and dairy products to food importers like Vietnam and Japan didn’t fully think things through when they supported protectionism and opposed TPP in the 2016 election, just as they didn’t realize how much corn they export to Mexico when denouncing NAFTA. When corn prices plummeted after Trump threatened to dismantle NAFTA, he agreed to pull back and renegotiate instead, for the time being. In Spring 2018, Trump threatened tariffs on steel and aluminum from Mexico and Canada, and in Fall 2018 started renegotiating a slightly re-branded version of NAFTA called USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) that the respective countries haven’t yet signed. The deal would strengthen pharma’s proprietary rights against generic drug makers, open the U.S. to the Canadian dairy market, and require that automobiles must get 75% of their parts from within their country of origin to qualify for tariff-free imports to the other countries.

American farmers that export meat, grain, wine, and dairy products to food importers like Vietnam and Japan didn’t fully think things through when they supported protectionism and opposed TPP in the 2016 election, just as they didn’t realize how much corn they export to Mexico when denouncing NAFTA. When corn prices plummeted after Trump threatened to dismantle NAFTA, he agreed to pull back and renegotiate instead, for the time being. In Spring 2018, Trump threatened tariffs on steel and aluminum from Mexico and Canada, and in Fall 2018 started renegotiating a slightly re-branded version of NAFTA called USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement) that the respective countries haven’t yet signed. The deal would strengthen pharma’s proprietary rights against generic drug makers, open the U.S. to the Canadian dairy market, and require that automobiles must get 75% of their parts from within their country of origin to qualify for tariff-free imports to the other countries.

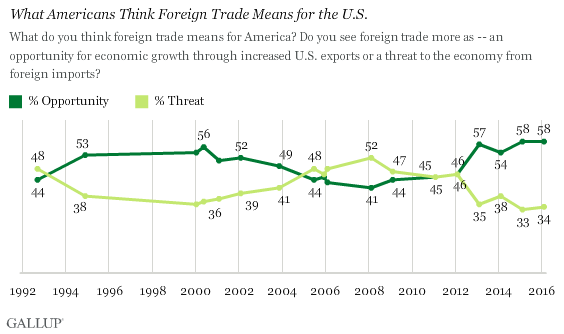

It was paradoxical to have all the candidates in 2016 more or less support protectionism at a time when Gallup polls showed that 58% of Americans (above) and nearly all economists favored free trade. Such polls are confusing because many voters might not fully understand the give-and-take and simply favor all the advantages of protectionism combined with all the advantages of free trade, or some might just want trade terms renegotiated for a “better deal” even if they’ve never read the existing terms (TPP, after all, got rid of tariffs that were hurting American exporters; without TPP, they’ll have to pay them). Polls likewise show that voters simultaneously want better benefits/services and lower taxes; the fact that they can’t get both is part of what drives their resentment toward government.

Looking at America’s negative balance of trade (importing more than we export), Donald Trump sees deficits as disadvantageous, though many economists point out that wealthier countries tend to import more than they export because they have more money to spend. Trump would like to get out of broad multilateral agreements and renegotiate bilateral one-on-one “beautiful deals” with each country that favor America.

But economists point out that when one country overplays its hand, other countries ice them out and sign separate agreements with each other (above) — thus the advantage of multilateral pacts. Countries are more willing to lower their own tariffs if it gives them access to multiple countries, not just one. A new TPP-11 (led by Japan but excluding the U.S. and, still, China) formed immediately after Trump’s withdrawal announcement. By mid-2017, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the EU had started negotiating lower tariffs with Asian food importers, hoping to undersell American farmers. With the U.S. and post-Brexit (post-EU) Britain on the sidelines, the Europe Union renegotiated with Vietnam, Malaysia, and Mexico, and Japan offered the EU the same deal on agricultural imports that it took the U.S. two years to hammer out during the TPP negotiations. An alliance of Latin American countries including Mexico, Peru, Chile, and Colombia formed their own Pacific Alliance to negotiate with Asian countries while China, sensing blood in the water, formed a 15-country regional partnership in Asia to rival TPP-11.

Healthcare Insurance

Like globalization, healthcare insurance played an increasingly large role in politics starting with the 1992 campaign. The main problem was escalating costs that outran inflation in the rest of the economy. While America socialized some healthcare coverage for the elderly in 1965 with Medicare, it has an unusual and spotty arrangement for everyone under 65 whereby employers, rather than the government, are expected to provide workers insurance subsidies, split anywhere from full coverage to a 50/50 match. It stems from WWII, when price controls (to prevent inflation) prevented companies from giving raises, so in a low-unemployment economy they attracted workers with benefits instead, including health insurance. It’s difficult to measure how many Americans die annually because they lack insurance because it’s impossible to control for multiple factors across a wide population and many people go on and off insurance. The uninsured rarely have preventative checkups that might save them years later. Studies prior to 2009 ranged from 18k to 45k deaths annually according to factcheck.org. If we use a low estimate of 16k, then over a million Americans have died from lack of coverage since WWII.

Nonetheless, the employer-subsidized insurance system works well for many people, especially at big companies. But it leaves others with no coverage and presents complications for small businesses, especially, because wider pools lower cost — the reason many countries spread risk among the whole population with cheaper government-run systems. That makes Americans more conservative about sticking to big companies and less likely to start up small businesses, hampering entrepreneurship. In America prior to 2013, it was expensive to buy individual coverage if you fell through the cracks and prohibitively expensive if you’d already been sick. In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked the United States 37th in the overall efficiency of its healthcare system. Most developed countries have cheaper healthcare with higher overall customer satisfaction, lower infant mortality, and longer life expectancies, but longer waiting periods for non-emergency procedures and less choice in choosing doctors. Teddy Roosevelt advocated universal (socialized) healthcare insurance as part of his Bull Moose campaign in 1912 and Harry Truman did likewise as part of the Fair Deal in 1948, but both initiatives were defeated.

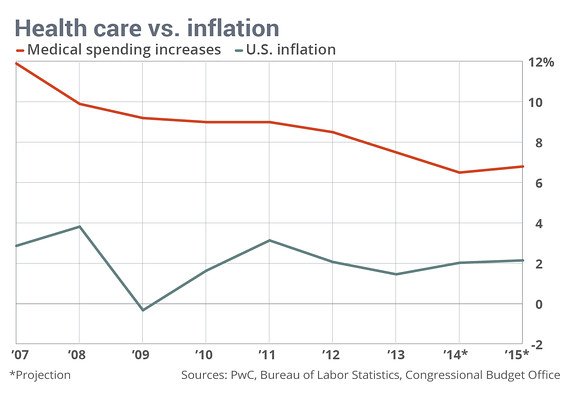

It’s important to distinguish between healthcare insurance and the healthcare itself, which also remains in private hands in America’s system and that of most other countries with socialized coverage (Japan and England are exceptions, along with communist countries). Most countries, and all developed nations outside the U.S., at least partly socialize insurance for those of any age. That way everyone pays in and everyone’s covered. The overall cost is lower per taxpayer than what American employee/employer combinations pay because, unlike profit-motivated private insurance companies, governments operate the system at cost. The young pay for the poor, but grow old themselves; men pay for women’s procedures but don’t complain because they have wives, sisters, and daughters. Yet, contrary to a common assumption among liberals, most other countries don’t have a purely single-payer public system; most supplement basic coverage with optional for-profit insurance companies. What other countries do have are stricter government-mandated price controls on what healthcare providers charge. While often seen as the bogeymen, American insurance companies lack bargaining power with providers (pharmaceuticals, hospitals, doctors, etc.) and can be victimized by high costs, inconsistency, fraud, or unnecessary procedures — costs that they pass on to patients/employers. One American can pay $1k for a colonoscopy while another pays $5k for the same procedure. As of 2012, according to an International Federation of Health Plans survey, MRI’s averaged $1080 in the U.S. and $280 in France. C-section births averaged $3676 in the U.S. and $606 in Canada. A bottle of Nexium® for acid reflux costs $202 in the U.S., $32 in Great Britain. Improving technology and over-charging contribute to inflation rates in medicine that always outrun the rest of the economy.

In the American healthcare debate, many analysts focus on these high provider costs while consumers/patients and the political left, especially, focus on glitches in insurance. As mentioned, profit margins of private insurance companies exceed the tax burden of socialized health insurance elsewhere. While socialized healthcare insurance raises taxes in other countries, that’s more than offset in the U.S. by higher costs for private insurance. And, prior to 2013, “job lock” problems arose in the employee benefit system when workers with pre-existing conditions (past illnesses) tried to switch jobs because, understandably, no new employer wanted to take on the increased risk of future medical costs. Formerly sick employees (~ 18% of all workers) in 45 states lacked portability, in other words, trapping them and putting them at the mercy of one employer, or on the outside looking in if they lost their job. Also, those that were covered risked having their coverage rescinded after paying premiums for years if the insurance company could find an error on the original application sheet, which they flagged but didn’t notify the holder about until he or she got ill. These rescissions, aka “frivolous cancellations” or “catastrophic cancellations,” filled up America’s bankruptcy courts with families whose finances (i.e. lives) were being ruined by runaway medical bills. Prior to 2013, the majority of personal bankruptcy cases in the U.S. involved medical hardship. Rescissions were outlawed in some states, and now everywhere by Obamacare, but as recently as 2009 Blue Cross employees testified before Congress that their company paid bonuses to representatives that could cancel coverage for paying policyholders once they got sick.

Meanwhile, some bigger companies suffer because they’re burdened with paying the long-term healthcare for pensioned retirees. For instance, with the good contracts the United Auto Workers union won in the mid-20th century, Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors were on the hook for all their retirees’ healthcare. Those obligations grew increasingly burdensome as life expectancies rose. If you bought an American vehicle before the 2007 collective bargaining agreement and GM’s 2009 bankruptcy restructuring, most of your money didn’t go to the materials or people who designed, built, shipped, and sold it; it went to pensions, to the tune of nearly $5 billion annually, industry-wide. The UAW Retiree Medical Benefits Trust now administers a much leaner independent fund with contributions from the Big Three automakers, some in the form of stock. Other companies like Walmart don’t have unions to worry about. They can shove much of their employees’ healthcare costs off onto the public dole (Medicaid) for the rest of us to pay. Medicaid is mostly state-managed, jointly-funded (state/national) healthcare insurance for the poor, passed in the same 1965 legislation as Medicare. It’s easy to see why the prevailing trend in the American workforce has been away from defined benefit pensions and toward defined contribution 401(k)’s, where companies aren’t on the hook for retirees’ healthcare. With a 401(k), employers might match a monthly contribution, but the employee is subjected to his or her own market risks. Additionally, once the employee qualifies for Social Security, they’ll receive some healthcare subsidies from the government in the form of Medicare.

Bill and Hillary Clinton made the biggest push since Harry Truman (or maybe Richard Nixon) to reform the system, though they didn’t end up pushing for universal coverage because they understood that private insurers had enough pull among politicians to block any legislation that would’ve cost them their business. Even as it was, when the Clintons crafted a patchwork bill in 1993 to address the most serious of the aforementioned problems, insurers filled the airwaves with baloney about how people would no longer get to choose their doctors. The bill lost in 1994, but a watered-down version passed in 1996 forcing companies to hire formerly sick workers. The hitch was that insurance companies retained the right to charge more. It was a classic case of corporations paying politicians to water down legislation. Insurance companies are among the biggest donors in Washington. Starting in 1986, the government allowed laid-off employees to continue purchasing healthcare through employer coverage temporarily through COBRA (at higher rates) and backed emergency care for anyone who came to a hospital through EMTALA. While the uninsured poor don’t have access to long-term care for diseases like cancer, heart disease, or diabetes, all Americans contribute to their emergency room care.

In response to the long-term threat of universal coverage, conservatives at think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute and Heritage Foundation formulated the mandate system. Mandates are compromises that require employers or individuals to purchase insurance from private companies, but force insurance companies to cover costlier patients, including the elderly, sick or those with pre-existing conditions. To offset the cost of covering those that need it, the young and healthy have to buy coverage, which is arguably smart anyway since catastrophic injuries or illnesses can impact people of any age. The Heritage Foundation’s Stuart Butler started promoting this market-based solution in 1989 though the idea goes back further, at least to the Nixon era, and included backing from Mark Pauly and Newt Gingrich. Butler’s idea required people to buy catastrophic coverage rather than comprehensive coverage. Famous free-market economist Milton Friedman published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal in 1991 promoting individual mandates. Along with his Secretary of Health & Human Services, Dr. Louis Sullivan, George H.W. Bush proposed the mandate idea in 1992 (minus the small employer requirement), but it died quickly in Congress, defeated by Democrats who either wanted an extension of Medicare to the whole population or just didn’t want to cooperate with Bush for partisan reasons with an upcoming election. No Republicans at the time mentioned anything about such a proposal being unconstitutional because the Congressional Budget Office said it was, in effect, a tax. Like Obama’s future plan, Bush and Sullivan put an emphasis on preventative care in order to keep down the costs of treating patients after they develop serious illnesses. Richard Nixon’s idea of an employer mandate suffered a similar fate to Bush’s in 1972, defeated by Ted Kennedy and other Democrats hoping for a simpler, more thorough-going single-payer system. In 1993, Republican Senators John Chafee (RI) and Bob Dole (KS) introduced a privatized mandate plan called HEART, for Health Equity & Access Reform Today Act, to counter Hillary Clinton’s Health Security Act, which they called “Hillarycare.” For many conservatives, an individual mandate for each household was preferable to an employer mandate and discouraged “free riders” that, for instance, took advantage of emergency rooms without buying any insurance. More libertarian conservatives at the CATO Institute opposed the idea from the outset. Ironically, Barack Obama, the man destined to become famously associated with the idea, opposed mandates during his 2008 campaign. Ted Kennedy later regretted his opposition to Nixon’s 1972 plan, but his home state of Massachusetts pioneered a mandate plan under Republican Governor Mitt Romney in 2006, that became the basis for the national government’s Patient Protection & Affordable Healthcare Act in 2010, aka Affordable Care Act (ACA) or “Obamacare.”

While the most unpopular feature is the mandate for young people to buy coverage, polls show that around 95% wisely want coverage anyway. Moreover, under any wider pool insurance system, the healthy pay for the unhealthy and men and women pay for each others’ maladies, just as homeowners who don’t suffer from fires, floods, or tornadoes pay for those who do (albeit with some adjustments for risk factors). That’s the very nature of insurance. You don’t cancel your home insurance if your house hasn’t burned down yet. To make coverage as affordable as possible for small businesses and those that need to buy individual coverage, each state under the mandate system either sets up its own online exchange for comparison shopping or feeds into a similar national exchange.

The Affordable Care Act version mandates free preventive care to lower costs, caps insurance company profit margins at 15% (20% for smaller companies) to bring costs more in line with other countries, prevents insurance companies from capping annual payouts to patients, and, at least through 2016, taxes those in the wealthiest bracket an extra 3.8% on investments (capital gains) and 0.9% on income to pay for expanded Medicaid coverage. There’s also a 40% excise tax on premium “cadillac” insurance plans for the wealthy. Around half of those who gained insurance coverage through the ACA did so through these subsidized Medicaid expansions. Insurance companies can’t cut off sick patients/customers, but the young and healthy have to buy insurance to help balance that out. Premiums for the elderly can’t be more than 3x higher than those for the young. Also, companies with over fifty full-time employees have to provide insurance. The ACA also taxes insurance companies and medical equipment makers.

The plan is often mistaken for socialism by conservative critics, but at their core mandates preserve health insurance for the free market by forcing individuals and companies to buy insurance rather than the government providing it for them. That’s the whole point. It is partly socialist because of the taxes and Medicaid expansion, and customers below the poverty line are subsidized on the exchanges. However, conservative think tanks pioneered the idea to stave off a full-blown socialist alternative whereby taxes provide insurance for everyone the way they do for those over 65 with Medicare Plans A and D or for some veterans with Veteran’s Affairs (VA). It’s a system that Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Sweden are moving toward. What is also socialist in the current and pre-Obamacare system is that employers who subsidize healthcare can deduct that from their taxes, meaning that all taxpaying Americans, including ones that aren’t covered, help subsidize those that are covered at larger companies. The widely popular Medicare is also socialist insofar as taxpayers fund a government-administered plan. As was the case with ACA, opponents of Medicare in the 1960s filled radio waves with unfounded rumors of “government-run death panels.” Medicare led to no such death panels and it’s worked fairly well, all things considered, but it’s also expensive and takes up a growing portion of the federal budget.

Again, there is a certain price to be paid for the fact that life expectancies are rising, especially when the elderly spend a lot on healthcare. Still, the fact that people are living longer is something most of us would argue is a good problem. There is no free quality healthcare; the money is either coming out of your paycheck if it’s from your employer (all of it, ultimately, not just the half they “match”), your own pocket through “out-of-pocket” bills, or your paycheck through taxes. The question is what setup provides quality healthcare in the most equitable and affordable way possible. The hybrid Affordable Care Act is a complicated, sprawling attempt to manipulate the free market through government intervention. It attempts to smooth over the worst glitches in the old system, but lobbyists ranging from insurers, drug companies, and hospitals all had a hand in crafting the legislation. Insurance lobbies convinced Obama and Congress to drop the idea of a “public option” being included on the new national insurance exchange, HealthCare.gov, though individual states retained the option to add their own non-profit public option (none did). Amish, Mennonites, American Indians, and prisoners aren’t mandated to buy insurance. For patients that don’t purchase insurance on the state or national exchanges — still most Americans, who continue to get their insurance from employers — the legislation doesn’t include any price controls on hospitals or drug companies, as those lobbies paid pennies on the dollar to avoid it.

Similar to ACA, polls showed that Americans favored much of what was in Clinton’s 1993-94 legislation when posed questions about items in the bill and opposed it when Hillary’s name was mentioned in conjunction with those same items. Both are telling examples of how spin can trump substance in politics, and how the way questions are spun dictates how respondents “frame” the question. Partisanship is now such an overriding factor in politics that when a Democratic president pushed a conservative idea in Congress, zero Republicans voted in favor, and many confused voters thought a socialist revolution was at hand, while others feared Nazism (in 2012, two of the top five books on the New York Times bestseller list, by Anne Coulter and Glenn Beck, argued that Obamacare would lead to concentration camps). Republican strategist Frank Luntz and Senate Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) instructed colleagues to block any real reform and to deny Obama bipartisan cover. Nixon and Bush suffered similar, if less inflammatory, responses from Democrats when they pushed mandate plans in 1972 and 1992. Much of the public misread the mandate idea as socialist in 2009 because they were spring-loaded to suspect President Obama of being a leftist and were unaware of its right-wing origins and purpose. Said Michael Anne Kyle of the Harvard Business School, “It was the ultimate troll, for Obama to pass Republican health reform,” accomplishing a liberal end (better coverage) through conservative means (the market).

However, the government’s private contractor fumbled its rollout of HealthCare.gov. Some people showed up in hospitals and drugstores only to find their new insurance carrier hadn’t processed their paperwork yet, and many have to renew their plan annually. Some companies keep so-called “29’ers” just under 30 hours a week to avoid having to buy insurance for them, while other small companies stay just under the fifty-employee threshold to avoid having to provide insurance. In an effort to control costs, people covered under policies purchased on HealthCare.gov will be offered “narrow networks” of providers who’ve agreed to keep costs down. That will no doubt annoy, but both narrow networks and sketchy customer service are issues many workers already experience on their regular employer-provided systems. As of 2014, over 70% of customers using the federal exchange were happy with the cost and quality of their coverage. Some insurance companies have grown less hostile to ACA as they’ve realized that expanded coverage means more overall profit, despite the 15% cap on profit margin. By 2015, the ACA had cleared two hurdles in the Supreme Court.

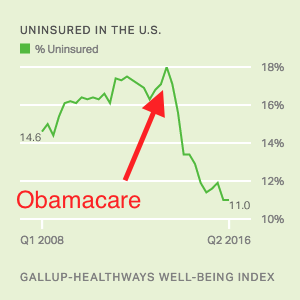

The number of uninsured Americans has fallen, but the cost of most people’s insurance rose the first year. Would it have risen as much without the ACA? It’s impossible to tell. With the fine for not buying insurance relatively low — in 2016, it rose to 2.5% of total household adjusted gross income, or $695 per adult and $347.50 per child, to a maximum of $2,085 — not as many young Americans bought coverage as hoped, raising concern that insurance companies still won’t have enough to cover everyone else, or that the government will have to make up the difference. Consult this official site for updated facts from the Congressional Budget Office, Census Bureau, Center for Disease Control, and RAND Corporation (think tank).

By the end of Barack Obama’s administration, the ACA was trending toward the death spiral caused by the low penalty for healthy young people not joining, causing insurance companies to raise rates for everyone else using the markets (not those already covered by their existing employer-sponsored plan). Insurance companies are uncertain moving forward whether the cost-sharing reductions and mandate will continue. “Death spiral” is bit hyperbolic, though, because while Obamacare has failed to cause the hoped-for “bending of the curve” on medical inflation, the rate of increase on premiums isn’t higher than it was before 2009 (538). Also, even with these rising premiums, insurance on the ACA exchange is still cheaper than buying stand-alone insurance or COBRA coverage by a considerable margin. Less than 5% of Americans are on the Obamacare public exchanges, with ~ 50% on employer-subsidized, ~ 35% on government-subsidized plans (public employees, military, politicians, Medicare/Medicaid, etc.), and ~ 10% uninsured (Kaiser Health, 2015).

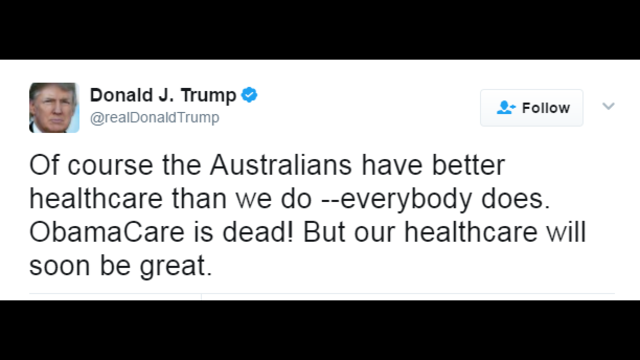

Supposedly, Donald Trump’s 2016 election meant that the ACA would be dismantled or reformed, as he promised during his campaign that he had a better plan that would cover everyone for cheaper without reducing Medicaid. But unless congressional Republicans really replace and improve upon the ACA rather than just repeal it, they will deprive millions of Americans, including many Trump voters, of their insurance. The Congressional Budget Office predicts that a simple repeal with no replacement will throw 32 million Americans off insurance within a decade and double premiums — numbers that discourage all but the most libertarian conservatives like Rand Paul (KY-R) and Freedom Caucus Chair Mark Meadows (NC-R). Now, in the words of Senator Lindsey Graham (SC-R), the GOP is like the “dog that caught the car,” with no agreed-upon replacement strategy as Trump was bluffing about his secret plan. A month into his first term, the new president conceded that revamping ACA would be “unbelievably complex….nobody knew that healthcare could be so complicated.” President Trump said that people were now starting to love Obamacare, but “There’s nothing to love. It’s a disaster, folks.” Congress wrote a repeal bill but it didn’t pass. Trump cajoled House Republicans to support the bill and called it “tremendous” but then Tweeted® that it was “mean” and that Australia had a better healthcare system than the U.S. (Australia has socialized coverage for everyone combined with supplemental private insurance).

Polls showed that only ~ 15-20% of Americans supported straight repeal, leading former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee to argue for repeal of the Seventeenth Amendment granting citizens the right to vote for Senators (prior to 1913, state legislators voted for U.S. Senators). Huckabee is the father of White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders.

In the words of journalist Jonathan Chait, Obamacare, however imperfect, “squared the minimal humanitarian needs of the public with the demands of the medical industry.” As for former President Obama, he fully endorses replacing ACA as long as the new plan provides better coverage for less money. In December 2017, Congress passed a tax reform bill that removed the mandate as of 2019. Stay tuned; the story of the Affordable Care Act is far from over. For now, the insurance exchanges and subsidies for poor subscribers remain even without the mandate. Whatever happens next, the key for voters will be whether or not some solution can at least bend the curve on medical inflation (premiums and provider costs) while maintaining quality care and shielding families from bankruptcies and premature deaths.

How Big Banks Got Too Big To Fail & (Maybe) Stayed That Way

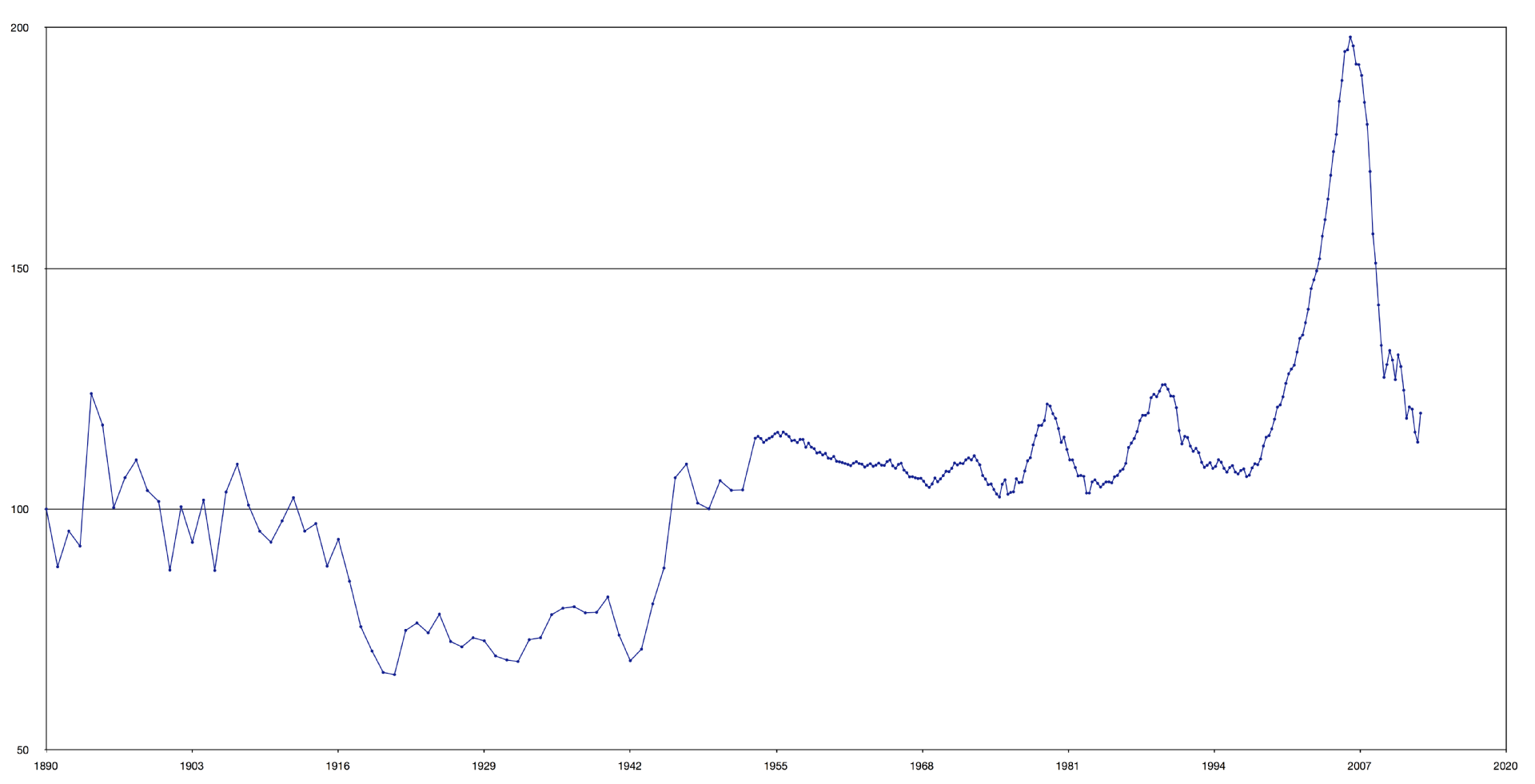

Bill Clinton fared far better with the rest of the economy in the 1990s than he had healthcare insurance. The economy was booming by the end of his first term and incumbents rarely lose re-elections in that scenario. As the saying goes, people “vote with their pocketbooks.” By the mid-90’s, the emerging Internet fueled explosive growth in the technology sector and better-than-anticipated petroleum discoveries drove oil down to one-fifth the price of the Carter years, adjusted for inflation. A tax hike on the rich from 36% to 39.6% didn’t inhibit things either. The government ran annual budget surpluses for the first time in decades. It’s easy to see, then, why Clinton would’ve gone along with Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan, his two Secretaries of Treasury (Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers), bank lobbyists and Republicans in loosening up Wall Street regulations even further than they’d already been loosened by Reagan. Greenspan kept interest rates low, fueling a speculative bubble in real estate. Low interests rates not only encourage borrowing, they also fuel the stock market because comparison shoppers prefer investing in stocks to low-yielding bonds.

President George W. Bush Presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan @ White House, 2005, Photo by Shealah Craighead

Between 2001 and ’05 the Fed pumped cash into the economy to keep it healthy after the 9/11 attacks and the collapse of the dot.com bubble. As a libertarian apostle of Ayn Rand, Greenspan believed that traders would naturally self-regulate as they pursued their selfish interests. But with the Federal Reserve’s role, this wasn’t a purely free market economy. Greenspan’s system privatized profit while socializing risk because markets either went up or the Fed lowered interest rates to bump them up. His successor Ben Bernanke followed the same policies after 2006. While the Fed was set up originally in 1913 to smooth out fluctuations in the economy, Greenspan’s high growth but bubble-prone policy ultimately made markets more erratic and he later testified before Congress that his strategy of deregulation had been a mistake.

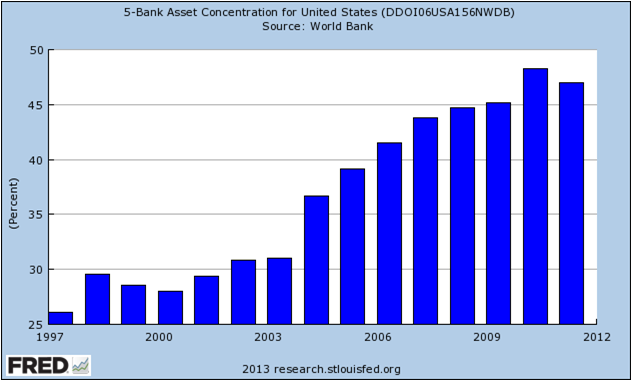

Commentators often speak of the Law of Unintended Consequences to describe how either passing or eliminating laws often has unforeseen consequences (e.g. defensive treaties leading to World War I). In this case, three deregulations (eliminations of laws) contributed to a financial meltdown a decade later. The first was the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 (GLB) repealing the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act from FDR’s New Deal that had set up a firewall between riskier bank investments and regular bank customer savings. For the half-century after Glass-Steagall, there hadn’t been many bank failures in America — the reason reformers like Texas Senator Phil Gramm argued that the law was outdated. In retrospect, though, Glass-Steagall might have been partly why the U.S. didn’t have bank failures. But Gramm was coming from the mindset that regulations only slow the economy. The GLB Act didn’t affect the major investment banks involved in the 2007-09 meltdown (other than allowing some mergers), but it affected commercial banks like Bank of America and Citibank on the periphery of the crisis. Additionally, anonymous surveys of chief financial officers show that many were increasingly asked to “cook the books” after the banking/accounting deregulations of the Reagan era. When such “creative accounting” led to scandals at Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco in 2001, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act restricted such practices, but predictably the financial industry just lobbied for exemptions. The never-ending back and forth of regulating and deregulating is complicated by a revolving door of career paths between finance, lobbying, and politics. Robert Rubin, for instance, went from Goldman Sachs to serving as Clinton’s second Treasury Secretary, back to Citigroup. The deregulatory policies he promoted in public office benefited both firms. Moreover, the $26 million he earned at Citigroup included bailout money from the government after the system he helped set up failed. In what’s known as regulatory capture, many of the regulators in agencies like the SEC (Securities & Exchange Commission, 1934- ) are familiar socially and professionally with the investors they regulate.

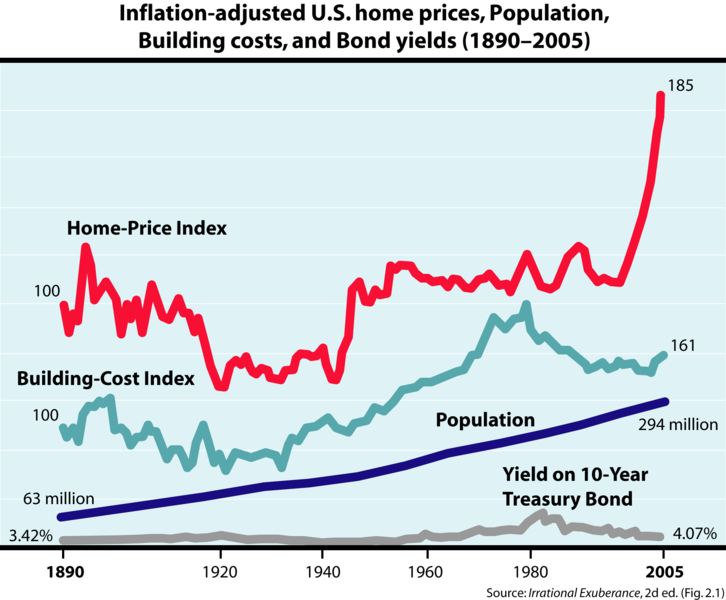

A second deregulation impacted the coming crisis more than Glass-Steagall’s repeal. A big cause of the 2007-09 meltdown and the danger it posed to the rest of the economy was a three-fold loosening up of leverage ratios by the SEC in 2004. Investment banks could now gamble their clients’ money on a 30:1 ratio, rather than 10:1. The amount they paid politicians to change the law was “pennies-on-the-dollar” (minimal in relation to profits). The financial industry lobbied around $600 million to politicians to deregulate in the decade prior to the meltdown while raking in trillions because of the boost to short-term performance. Bankers got big bonuses if their bets paid off and shareholders or taxpayers got the bill if they lost, in the form of plummeting stock or bailouts. Head I win; tails you lose. The men who “incompetently” ran the big banks into the ground walked away with hundreds of millions of dollars in bonuses and salaries they’d already made based on short-term returns. It seems, rather, that the real incompetence lay with the politicians and voters who drank too much deregulatory Kool-Aid®. Banks leveraged more in real estate than other parts of their portfolios. For every $1 that Americans spent on housing, Wall Street bet at least another $30 that the housing bubble would increase in perpetuity. With such leveraged bets, even a small 3-4% dip in housing prices would wipe out the banks…that is unless the government (i.e. taxpayers) came to their rescue because allowing them to collapse would’ve cratered the entire American economy, if not the world’s.

A third deregulation was the repeal of obscure laws that originated after the Panic of 1907 and 1929 Crash outlawing bucket shops. Bucket shops were gambling parlors, essentially, where people without actual share ownership just bet on the stock market the way one would bet on horses or football games. No official transaction occurs on any institutional exchange. Congress quietly repealed portions of those laws and another from the New Deal in the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, on the last vote of the last day of the 2000 session — the kind of dull scene on C-SPAN cable that viewers flipped past with the remote control. That changed how big financial firms bought and sold complicated financial products called derivatives. Here’s where things get very tedious if they haven’t gotten tedious enough already, so just strap in and do your best to comprehend.

Two derivatives threatened the economy in the early 21st century: real estate-based mortgage-backed securities and credit default swaps to insure against the failure of those mortgage-backed securities. A good starting point to understanding mortgage-backed securities is realizing that your mortgage — the loan you took out on your house, store/business, studio, farm, ranch, or condominium — can be bought by those that want to assume the risk of you not paying it off in exchange for the gain of you paying interest on the loan. Your job is to pay it off, not decide to whom you pay. Mortgage-backed securities (MBS’s) are bundles of real estate mortgages that are sold as investments to other people who then own parts of your loan. The seeming upside of MBS’s was the traditional stability of the American real estate market. Their key flaw was that when mortgages were securitized — packaged and sold as financial products like stocks or bonds — the bank no longer lost their money if the homeowner defaulted on the loan because they’d sold it to someone else. Thus, banks no longer had as much incentive to not lend to borrowers they suspected might not be able to pay them back.

Invented by Salomon Brothers’ Lew Ranieri in 1977, mortgage-backed securities were bunched into portfolios called collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that few people, including investors at other banks or rating companies like Standard’s & Poor, studied in enough detail to examine all the high-risk mortgages they included. At this point, your home loan had been so “sliced and diced” that it would’ve been difficult to trace. In The Big Short (2015), based on Michael Lewis’ 2010 namesake book, the narrator tells viewers that Ranieri had a bigger impact on their lives than Michael Jordan, iPods® and YouTube® combined, even though no one had heard of him. Lewis adds that the opaque, complicated, boringness of high finance is deliberate as it shields Americans from the reality of Wall Street corruption — in this case that bankers were getting rich from short-term bonuses by hiding bad, high-risk loans into bundles of seemingly stable real estate investments that were sold to other banks, investors, pension funds, etc. CDO’s included the lowest-rated tranches of sub-prime mortgages that they couldn’t hide in normal MBS’s — ones with high variable rates scheduled to go up in 2007. Adding fuel to the fire, bankers took advantage of the deregulations regarding leverage ratios and bucket shops to place side bets on the CDO’s called synthetic CDO’s. The amount of money riding on these unregulated derivatives was about 5x more than the CDO’s themselves. Billionaire investor Warren Buffett called these complicated types of derivatives “weapons of mass destruction” because they were unregulated and only served to encourage reckless investment. It’s safe to say that when 19th-century president Andrew Jackson complained of unscrupulous financiers profiting off the hard-earned money of farmers and craftsmen by simply re-shuffling it, he scarcely could’ve imagined anything as esoteric as 21st-century Wall Street.

Invented by Salomon Brothers’ Lew Ranieri in 1977, mortgage-backed securities were bunched into portfolios called collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) that few people, including investors at other banks or rating companies like Standard’s & Poor, studied in enough detail to examine all the high-risk mortgages they included. At this point, your home loan had been so “sliced and diced” that it would’ve been difficult to trace. In The Big Short (2015), based on Michael Lewis’ 2010 namesake book, the narrator tells viewers that Ranieri had a bigger impact on their lives than Michael Jordan, iPods® and YouTube® combined, even though no one had heard of him. Lewis adds that the opaque, complicated, boringness of high finance is deliberate as it shields Americans from the reality of Wall Street corruption — in this case that bankers were getting rich from short-term bonuses by hiding bad, high-risk loans into bundles of seemingly stable real estate investments that were sold to other banks, investors, pension funds, etc. CDO’s included the lowest-rated tranches of sub-prime mortgages that they couldn’t hide in normal MBS’s — ones with high variable rates scheduled to go up in 2007. Adding fuel to the fire, bankers took advantage of the deregulations regarding leverage ratios and bucket shops to place side bets on the CDO’s called synthetic CDO’s. The amount of money riding on these unregulated derivatives was about 5x more than the CDO’s themselves. Billionaire investor Warren Buffett called these complicated types of derivatives “weapons of mass destruction” because they were unregulated and only served to encourage reckless investment. It’s safe to say that when 19th-century president Andrew Jackson complained of unscrupulous financiers profiting off the hard-earned money of farmers and craftsmen by simply re-shuffling it, he scarcely could’ve imagined anything as esoteric as 21st-century Wall Street.