“We have frequently printed the word Democracy. Yet I cannot too often repeat that it is a word the real gist of which still sleeps, quite unawaken’d.” — Poet Walt Whitman, 1871

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers Through the Cumberland Gap, George Caleb Bingham, 1851-52, Kemper Art Museum, St. Louis

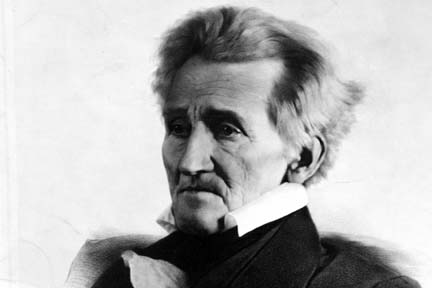

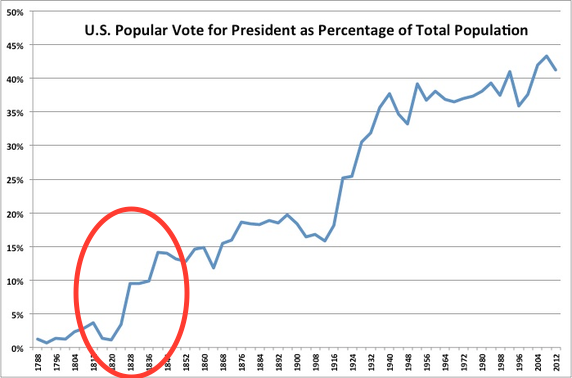

As strange as it seems today, most Americans didn’t embrace the goal of democracy for most of American history. If they had, then it wouldn’t have been such a struggle for most people to attain citizenship and voting rights. In the 1790s, the Federalists argued that those who owned the country should run it because it was they who paid property taxes. But the democratic tide turned with Thomas Jefferson’s election in 1800 and gained momentum in the early 19th century. French travel writer Alexis de Tocqueville observed that America “had arrived at a state of democracy without having to endure a democratic revolution” such as the tumultuous French Revolution. As noted in the Ratcliffe’s optional deep dive below, this gradual democratic transition traced to the tradition of representative government in the colonial era, the widespread availability of land that qualified freeholders to vote, and the liberalizing legacy of the American Revolution’s equal-rights ideology. And it coincided with the few free, propertied black Americans losing their right to vote, along with deporting Native Americans (more below). Among white males, mass democracy was mostly in place by the Jacksonian Era, named for the two-term presidency of Andrew Jackson, aka “Old Hickory.” Reviled as a demagogue by some and beloved by others, Jackson catered to the very voters who had won the vote in the decades since the Revolution. He put such a decisive stamp on the 1820s and ’30s that they are often called the Age of Jackson. It’s also called the “Era of the Common Man” because it was when American politics adjusted to the implications of an enlarged electorate, becoming necessarily populist.

By the 1830s, all white American males could vote, whereas in most of the British colonies and Early Republic only Protestants that owned sufficient property had suffrage. New western states synced their constitutions to the Bill of Rights and wrote their constitutions to allow for white male suffrage. Eventually, the original thirteen states caved in and revised their laws to allow property-less white men to vote (Georgia and Pennsylvania had from the start). If the original thirteen states hadn’t loosened restrictions, more middle-class people would’ve emigrated west partly for more political power. Increased voting rights created a ratchet effect that made it harder to oppose voting rights the way Federalists had in the 1790s. Simple math meant that the more regular men could vote, the harder it was to campaign on the idea that they shouldn’t. While universal white manhood suffrage (UWMS) may not seem generous to modern readers, it was radical for the times. Revolutionary France was the first country to allow it in 1792, preceded and followed by the U.S. piecemeal from 1776 to 1830, and then Switzerland in 1848. The German Confederation and Britain didn’t do likewise until 1866 and 1885, respectively. The U.S. probably wouldn’t have granted suffrage to black men (1870), women (1920), Native Americans (1924-57), and all minorities for keeps (1965) if it hadn’t started down this path with white males.

In this line of thinking, America’s embrace of participatory democracy in the early 19th century, while initially limited to white men, laid the foundation for increased suffrage down the road. But it’s not quite that straightforward because the very white men who newly won the vote were the ones most blocking others from getting it. And abolitionist founders like Alexander Hamilton and John Jay promoted intra-white elitism/meritocracy when it came to voting rights, whereas pro-UWMS Thomas Jefferson, for instance, ended up supporting slavery. As we’ll see in Chapter 22, the inheritors of Jackson’s Democratic Party helped thwart democracy for others after the Civil War. Still, though it didn’t come about until 1965, there seemed to be natural impulse or trajectory built into American history toward democracy, or at least that’s how more Whiggish historians have seen it, at least in retrospect. In the Jacksonian Era, Tocqueville noted that Americans’ most distinctive trademark was a sense of egalitarianism. Non-Whigs, though, reject historical inevitability altogether and are skeptical of oversimplified, uniform trends and single “turning points.” Poet Walt Whitman wrote the words at the top of this chapter after UWMS, but before others won suffrage.

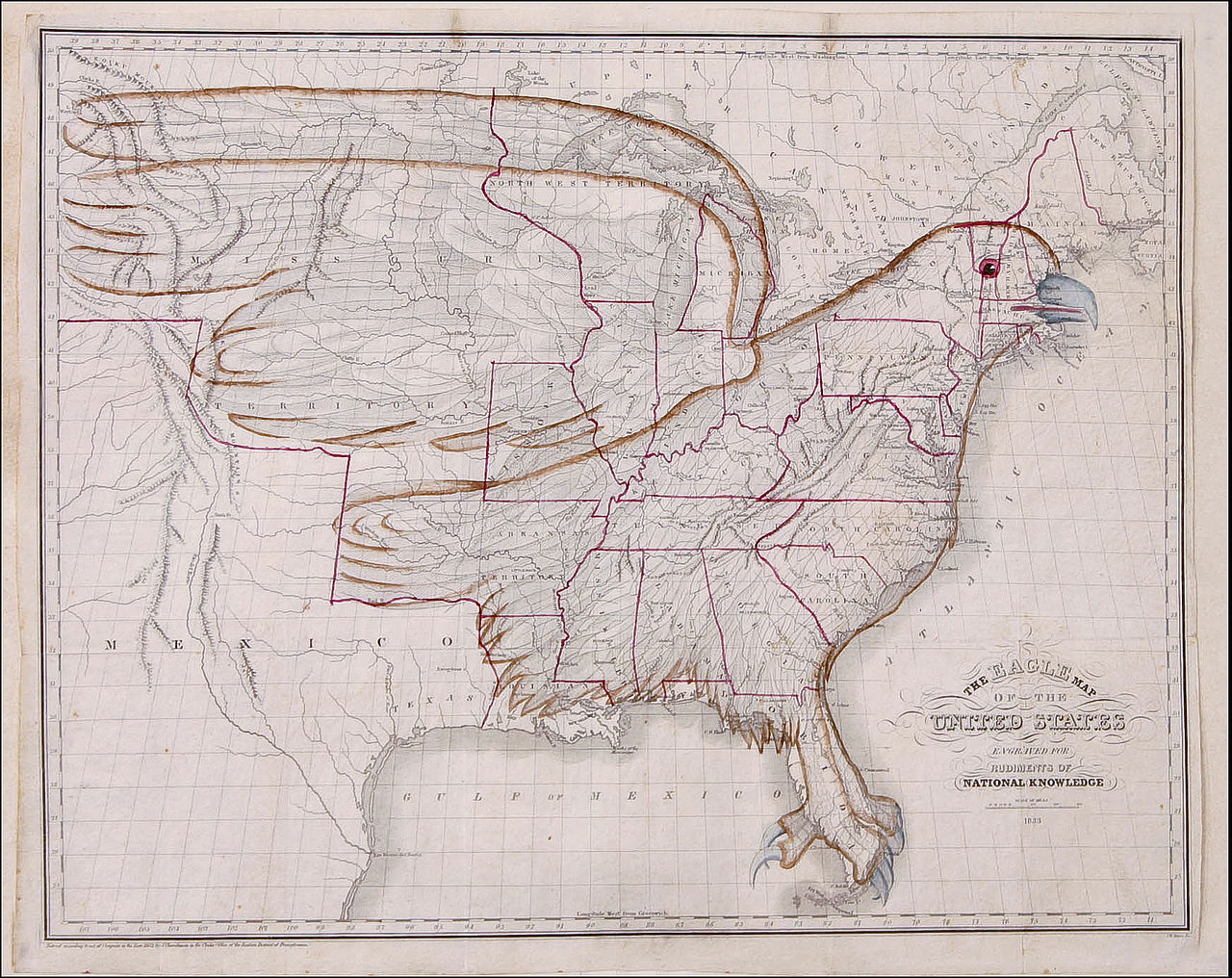

“The Eagle Map of the United States” from Rudiments of National Knowledge, Presented To The Youth Of The United States, And To Enquiring Foreigners, by A Citizen Of Pennsylvania, published by E.L. Carey & A. Hart in Philadelphia, 1833

Roots

Roots

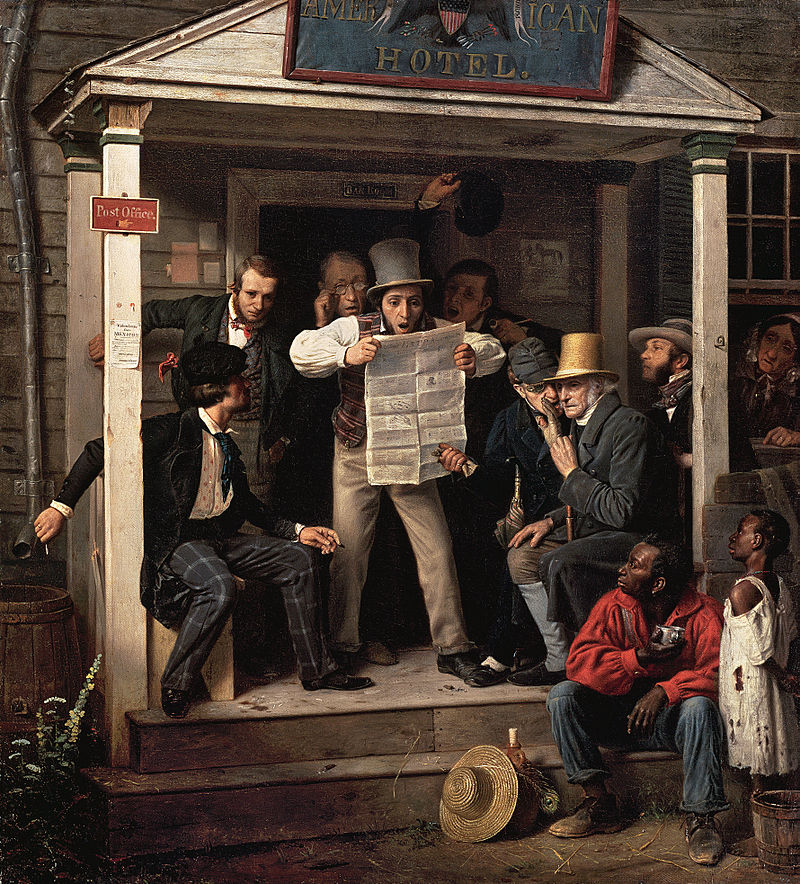

Democracy’s seeds were planted earlier than the 1820s, during the colonial and Revolutionary era, if not back in Classical Greece and Rome, and medieval England. The American Revolution scared away many of the Loyalists most likely to interfere with its egalitarian bent. Then Jefferson’s win in 1800 helped steer the 19th century toward greater suffrage. With a more market-oriented economy in the 1820s and ’30s and steam-powered printing presses providing cheap newspapers filled with political commentary, an increasing number of these newly eligible men voted. The elections they voted in were raucous affairs, with ballot boxes placed in town squares, saloons, and tobacco shops. Voters were susceptible to bribery (often liquid) and intimidation because ballots were out in the open, unlike today’s private polling. But voters were reasonably well-informed. The 1792 Postal Act granted cut rates for newspapers and post offices often left extras lying around for people to read. Newspapers took up a big portion of the postal system’s bulk weight, much the same way that YouTube® and Netflix® swallow bandwidth online today. As we saw in Chapter 10, James Madison considered it “favorable for liberty” for government to not only respect free speech — not controlling newspapers’ content — but also to subsidize the postal system to make it affordable for those newspapers to reach every corner of the country.

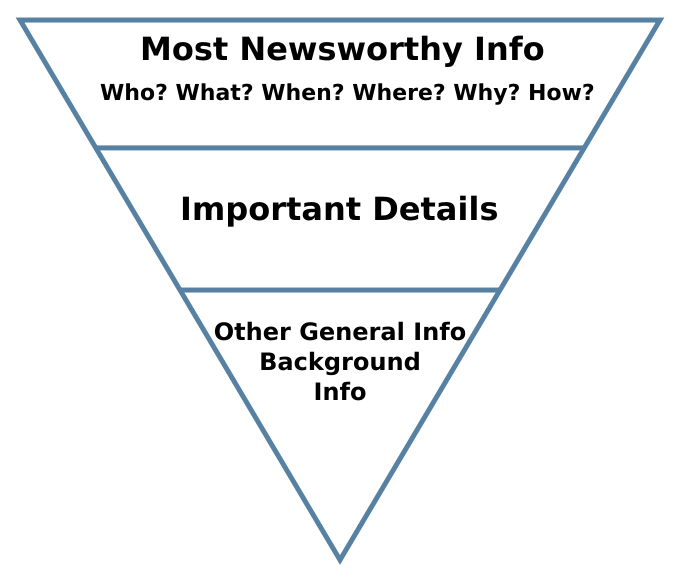

Tocqueville wrote that these accessible newspapers kept rural Americans, at least literate ones, more informed than European farmers. They were printed in large cities, with New York’s Sun (1833-1850) pioneering the mass-circulation penny press, followed by the Philadelphia Public Ledger (1836), New Orleans Picayune (1837), Baltimore Sun (1837), and Cleveland Plain Dealer (1842). News ranged from serious political content and local coverage to fake stories about things like winged Martian “man-bats” and unicorns seen through telescopes. These fanciful stories quickly made the Sun the most successful paper in the world. Historian Matthew Goodman described how hoaxes were democratic because people exercised their own right to distinguish truth from fiction, just as they would at P.T. Barnum’s museum, but penny presses also spread legitimate news while displacing more high-minded six-penny papers that had catered to merchants and politicians. With the advent of telegraphs — about which we’ll cover more in the next chapter — news agencies like the Associated Press (AP, 1846- ) in America and Reuters (1851- ) in Britain aggregated news “wires” for subscribing papers, eventually writing in the top-down inverted pyramid style (right) that put the most important information first so that newspapers could edit out the bottom to save space or cost. Less purely partisan than the Newspaper Wars of the 1790s (Chapter 11), steam-powered papers of the 19th century enhanced participatory democracy while still making it incumbent on readers to distinguish between truth and fiction.

Tocqueville wrote that these accessible newspapers kept rural Americans, at least literate ones, more informed than European farmers. They were printed in large cities, with New York’s Sun (1833-1850) pioneering the mass-circulation penny press, followed by the Philadelphia Public Ledger (1836), New Orleans Picayune (1837), Baltimore Sun (1837), and Cleveland Plain Dealer (1842). News ranged from serious political content and local coverage to fake stories about things like winged Martian “man-bats” and unicorns seen through telescopes. These fanciful stories quickly made the Sun the most successful paper in the world. Historian Matthew Goodman described how hoaxes were democratic because people exercised their own right to distinguish truth from fiction, just as they would at P.T. Barnum’s museum, but penny presses also spread legitimate news while displacing more high-minded six-penny papers that had catered to merchants and politicians. With the advent of telegraphs — about which we’ll cover more in the next chapter — news agencies like the Associated Press (AP, 1846- ) in America and Reuters (1851- ) in Britain aggregated news “wires” for subscribing papers, eventually writing in the top-down inverted pyramid style (right) that put the most important information first so that newspapers could edit out the bottom to save space or cost. Less purely partisan than the Newspaper Wars of the 1790s (Chapter 11), steam-powered papers of the 19th century enhanced participatory democracy while still making it incumbent on readers to distinguish between truth and fiction.

“War News From Mexico” (1848), Richard Caton Woodville, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR

Then there was the rise of the market-oriented economy that we’ll also discuss in the next chapter (14), whereby subsistence farming for one’s own family gave way to higher-yielding surplus crop production to be sold on markets. There’s a saying that people “vote with their pocketbooks” and that’s truer in a market economy than one where most voters are simple dirt farmers, whose lives wouldn’t be much different regardless of who is in power. The Panic of 1819 underscored how integrated most people were into the market economy.

The 1819 Panic started in Europe due to fluctuations after the Napoleonic Wars and Britain reverting £’s to the gold standard. Other factors exacerbated its impact in America, including bad bank loans and saturation of the cotton market. Cotton prices dropped from 34¢ to 15¢/lb. due to over-supply, with more cotton in the pipeline than clothes factories and sellers could keep up with. Unlike the U.S. after the 1930s, there was no safety net for the downturn’s victims, with the indebted doing hard labor in prison, enslaved workers being auctioned, and prostitution and crime on the rise. The Panic of 1819 led to foreclosures on homes and farms that turned many citizens against the National Bank (BUS) started by Alexander Hamilton in the 1790s. You remember the $15 million deal the U.S. got from France for the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. The 15-year bonds were redeemable in gold in 1818, and the BUS couldn’t supply the Treasury. BUS didn’t have enough of the gold they were backing their paper money with. Since the central government ran the bank, voters naturally blamed government for the recession. Bad loans are largely the fault of borrowers or bankers that shouldn’t have put their faith in borrowers to begin with, but people rarely blame themselves for financial difficulties.

Anti-bank sentiment, rational or otherwise, played mainly into the hands of the Democratic-Republicans, the peoples’ party. They’d acquiesced in Hamilton’s bank, re-chartering it even in 1816, but the faction nonetheless appealed to voters who distrusted high finance. Federalists were more the party of big business, but they hadn’t survived the War of 1812. They died off partly because some of them considered secession during the war, but mostly because you can’t oppose poor whites voting if they can – it’s too late since they obviously won’t vote to disenfranchise themselves. A more business-oriented faction of the Democratic-Republicans called the National Republicans (later Whigs) forked out of Jefferson’s old faction by the late 1820s while the rump (original core group) embraced the working classes, craftsmen, yeoman farmers, and frontiersmen. The D-R’s rump group now called themselves by the name the Federalists had used to insult them in the 1790s: the Democrats, or “the Democracy.” If you had to be dumber than a donkey’s ass to allow regular white men to vote then, by God, a kicking donkey their mascot it would be.

Political Parties

Groups organized to mobilize these new voters and cohere their views and opinions. These political parties weren’t run by the government and weren’t generated by the Constitution. They formed outside the government as a way for people to get elected to serve in the government. Founders like George Washington hoped to avoid parties but, as we saw in the previous two chapters, Federalist and Democratic-Republican congressional factions coalesced around Hamilton and Jefferson’s competing policies, respectively, in the 1790s. Next-generation Democrats like Martin Van Buren of New York argued that, far from being a bad thing, actual parties as formal institutions had upsides. For one, they gave unprivileged men like Van Buren, whose parents were tavern-keepers, a stepping-stone into politics by allowing them to work their way up through the organization, similar to a company ladder. They allowed strategists to build coalitions that could garner over 50% of the vote by setting differences aside and uniting against common opponents or issues. In the 19th century, parties organized barbecues, torchlight parades, and meetings to give voters a sense of identity and mobilize (manipulate?) them with slogans, songs, and alcohol. Circus clowns sang about politics and lampooned politicians. Politicians now had to grovel for votes directly, often chopping down a tree and giving a stump speech. By the early 1830s, the Democrats held conventions to nominate single president/vice-president tickets, so that candidates within a party didn’t steal votes from each other. Van Buren was one of the chief architects of America’s first political party, the Democrats. And, within his state, Van Buren created an early political machine, the Albany Regency, named for New York’s capital.

All this required a new generation of politicians. Washington never would’ve lowered himself to begging for votes and no one would’ve been able to hear the soft-spoken Jefferson without a megaphone. Unlike today, when politicians have to endlessly “press the flesh” on campaign trails, Washington refused to shake hands as president, even with elites, because he thought it was beneath the dignity of the office. But political parties are inevitable in a republic because coalitions naturally team up to defeat common enemies. Ideally, they provide a non-violent way to channel peoples’ hatreds and disagreements, though they can lead to war as well. The party system was complicit in bringing about the Civil War in 1860, or at least failed to prevent it, and threatened the constitutional framework in 1876 and 2020. The system tends to spin off third parties like the Workingman’s Party, Populists, Greens, Tea Party, etc., and then revert toward two. The reason is that, as new parties splinter off, they siphon votes, at which point they re-form alliances with one of the existing parties to oppose those they mutually hate more than each other. One historian noted that third parties are like honeybees: “once they’ve stung, they die.” Third parties impact the main two before they die off, as the existing parties co-opt their most popular ideas. On rare occasion, a new party will supplant one of the main parties. That happened in the 1850s when the new Republicans displaced the Whigs. Today, the Freedom Caucus (Tea Party) and Donald Trump supporters are subsumed under the Republican mantle and have transformed the party fundamentally, but haven’t adopted a new name.

This is a good time to remind us that democrat and republican have different meanings depending on whether the first letter is capitalized. Americans all live in a republic or representative democracy, but today’s two main parties, each trying to appeal to a broad electorate with their generic name, are known as the Democrats and Republicans, with caps. Presumably, names that stood for something specific would be too exclusive to win elections. After their inception in the mid-1850s, Republicans also became known as the GOP, for “Grand Old Party.”

Action Jackson

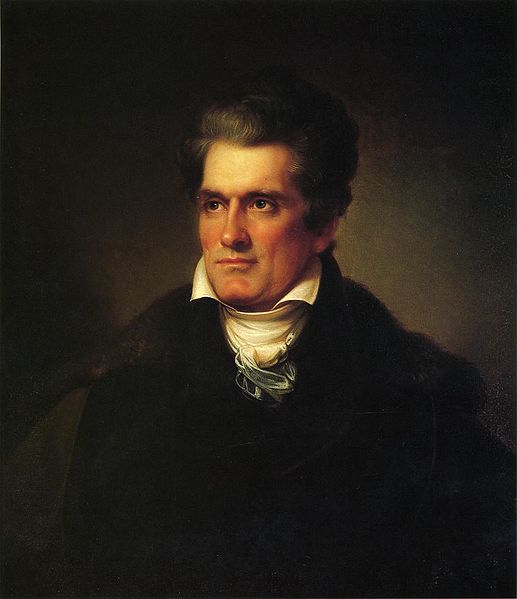

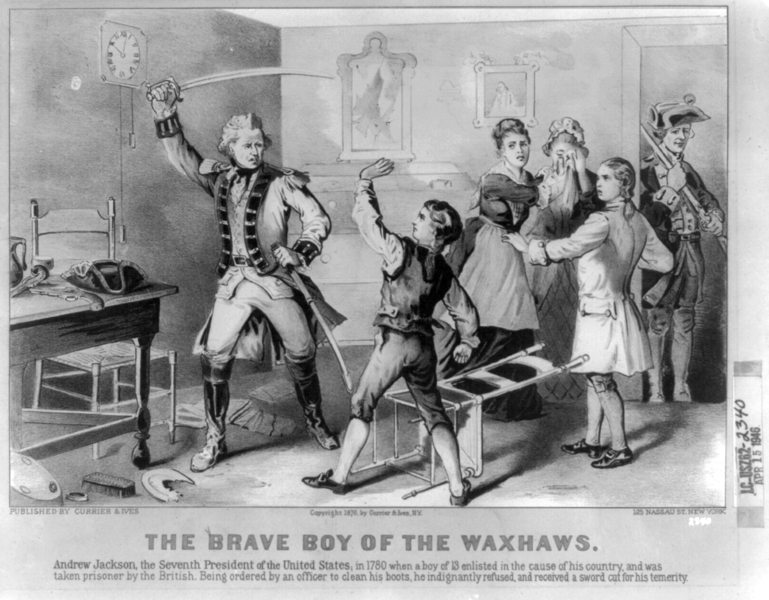

For the figurehead of the Democratic Party in the 1820s, Van Buren favored Andrew Jackson, the most popular and famous man in America and hero of the Battle of New Orleans. Jackson was a rough-hewn frontiersman and the face of a new breed of politicians born into humble circumstances. Regardless of their parents’ wealth, and only Hamilton wasn’t born into some privilege, all the Founders were well educated. Jackson was not and was the first important leader young enough to have not participated directly in the Revolution, though much of his family was killed in it, including his mother. He came from the Carolina frontier and had a scar etched into his cheek where a Redcoat cut him as a young boy when he refused to shine his boots. His father died in a logging accident just weeks before he was born.

Andrew Jackson (ca. 1780) disobeys British Redcoats as a brave lad in this Currier & Ives Painting, 1876.

Jackson’s minimal formal education didn’t mean he wasn’t intelligent, but he was foremost a man of action, thus the title of our sub-heading. Like Abraham Lincoln a generation later and hundreds of other 19th-century politicians, he taught himself to read well enough to become a country lawyer, honing his trade in an office rather than attending one of America’s expensive law schools. Jackson led filibusters (private military expeditions) that cleared Indigenous Americans off frontier land, then resold it for a higher price. Through these means, Memphis and Nashville came to be. Jackson earned his nickname, Old Hickory, honestly — hickory being a hardwood used for hunting bows and wheel spokes. He carried two slugs around inside him, one near his lung and the other in his shoulder, as souvenirs of his life as a dueler, brawler, and soldier. The ball in his lung, which he took in a duel before killing his opponent, caused “Two-Gun Andy” constant problems and he often pulled out a handkerchief to cough up blood, sometimes for theatrical effect.

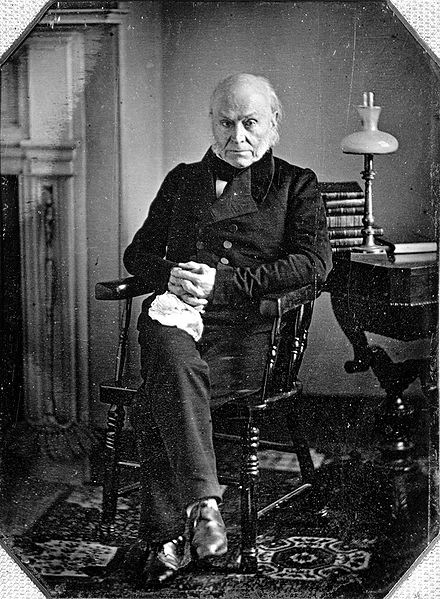

In the 1824 election, Jackson won more popular votes than the other three candidates (43%) but failed to win an electoral majority. Democrats undercut their chances by running three candidates who stole votes from each other. At that time, there was no apparatus to compel candidates otherwise. That threw the election into the House of Representatives, where some of the congressmen who helped John Quincy Adams (right) win the presidency won cabinet appointments in his administration. This “Corrupt Bargain” was legal, but it looked bad considering that Jackson won the popular vote. It looked worse, yet, considering that Adams (National Republican) symbolized the older Founding elite as John Adams’ son, while Jackson represented the “common man” voter and frontiersman. They were not only attracted to his take-charge, no-nonsense style; now they were angry that their democratic will had been denied. But Old Hickory’s story didn’t end with his loss in 1824.

Jackson’s loss mobilized the Democratic Party just as more voters became eligible and they pioneered party politics by broadening and solidifying their coalition. It’s easy for voters to get frustrated because few people agree with all the items on any one party’s platform. But parties provide the best mechanism for anyone serious about winning precisely because they create broad, umbrella coalitions among people who don’t agree on everything. For 1828, the Democrats nominated Jackson and Jackson alone — three years early (1825) to avoid stealing votes from each other — and they arrived at a comprehensive platform they took to the voters. Platforms are agendas or lists of ideas and positions on major issues. They also made sure to win mid-terms elections so that they could control votes in the House in case no one, including Jackson, won a majority of electoral votes. The Democrats’ theme was “Hunters of Kentucky,” a song that commemorated Jackson’s 1815 victory at New Orleans and captured the populist spirit of their party’s southern and western base.

Jackson came out swinging in 1828, accusing Adams of being an educated, elitist dandy. Indeed, Adams’ childhood tutor was Thomas Jefferson! They even accused him of, in effect, being a pimp, for procuring the services of the world’s oldest profession on behalf of a Russian diplomat. Adams’ camp shot back that Jackson’s mom was a prostitute brought over by Redcoats who married a mulatto, and that Jackson stole his wife Rachel from another man and married her before her divorce came through, making her a bigamist. In truth, the Jacksons never knew her earlier divorce wasn’t finalized but, technically, the charges were true. Rachel took the news hard and died of a heart attack just as Andrew was winning the election. Jackson was already “outside the beltway” (an outsider candidate) long before freeways encircled Washington, D.C., but now the thin-skinned, confrontational brawler arrived in the town he hated with an even bigger chip on his shoulder, thinking that his political enemies had killed his wife. “May God Almighty forgive her murderers,” Jackson said. “I never can.”

The “Jackson Men” stormed the Federal City for the celebration, crashing the most famous inaugural ball in presidential history. Only a generation before, Martha Washington attributed a small grease stain on the Executive Mansion wall to “Democratick rabble.” One can almost envision her nose angled upwards as she said it. Now, in 1829, Jackson’s ruffians tore down the drapes and chandeliers, muddied the carpet, and essentially threw themselves a kegger on the White House lawn. Later, when Jackson supporters in upstate New York sent him a 1400-lb. block of cheddar even bigger than Jefferson’s 1235-lb. “mammoth cheese,” he invited 10k guests to the White House to share it before it stunk up the place in the summer heat. They ate it in under two hours.

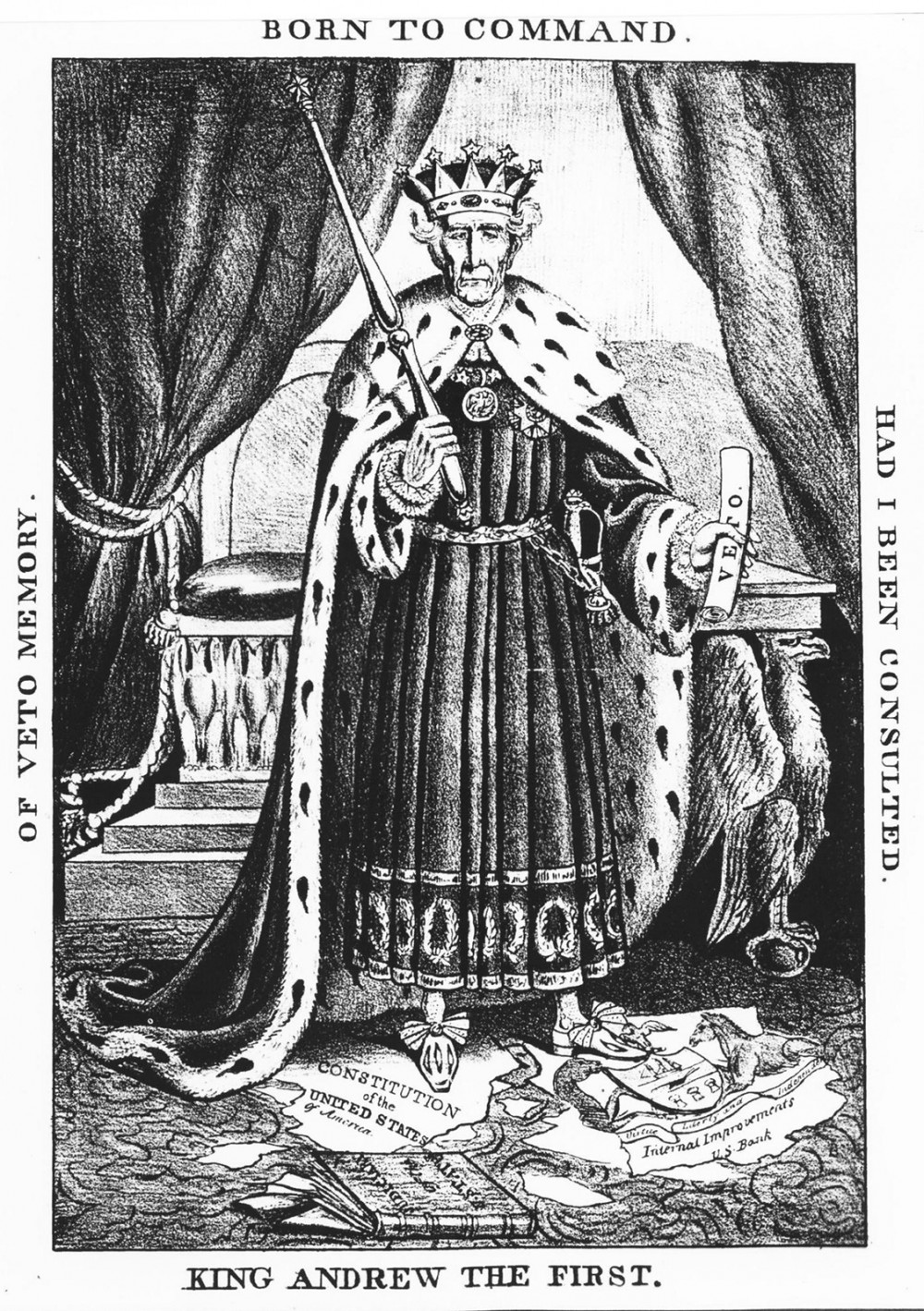

Their hero, Jackson, strengthened the executive branch in relation to both the legislative (Congress) and judicial (courts) branches, as well as the states. He came to office with a clear platform, unlike the overseer-type administrations that characterized most of the earlier presidents, Jefferson being the main exception. Previous presidents, for instance, understood the veto as intended for unconstitutional or crazy congressional laws, but Jackson understood that part of the checks and balances system was the president’s right to veto any law he disagreed with, just as Congress can override the president’s veto with a 2/3rd majority. His twelve vetoes eclipsed the previous six administrations’ ten total.

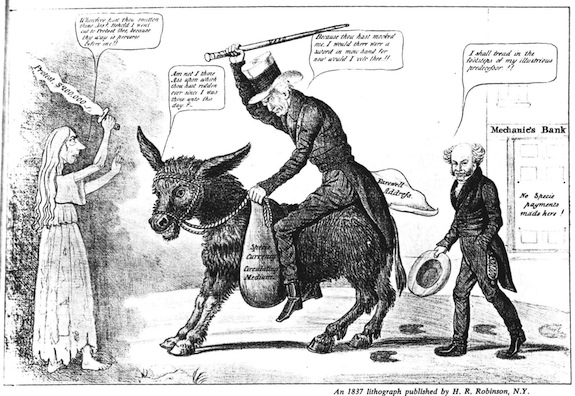

Bank War

A good example of both Jackson’s agenda and willingness to veto was his stance against the National Bank. Jackson thought that only specie, defined as hard money (coin) or precious metals like gold and silver, should be used as currency. It’s ironic that Jackson ended up on paper money instead of a coin (above). Jackson represented what we’d later call blue-collar workers and distrusted financiers who shuffled some paper around and made more money than producers who worked with their hands. We can only shudder to imagine what Jackson and his followers would’ve thought of the financial meltdown of 2008, when $10 trillion evaporated from American households, mainly because of the irresponsibility of mortgage lenders and big banks and the complexity of Wall Street’s derivative products. In Jacksonian America, the biggest bank was associated with the government and, as mentioned, tied in the public’s imagination to the Panic of 1819.

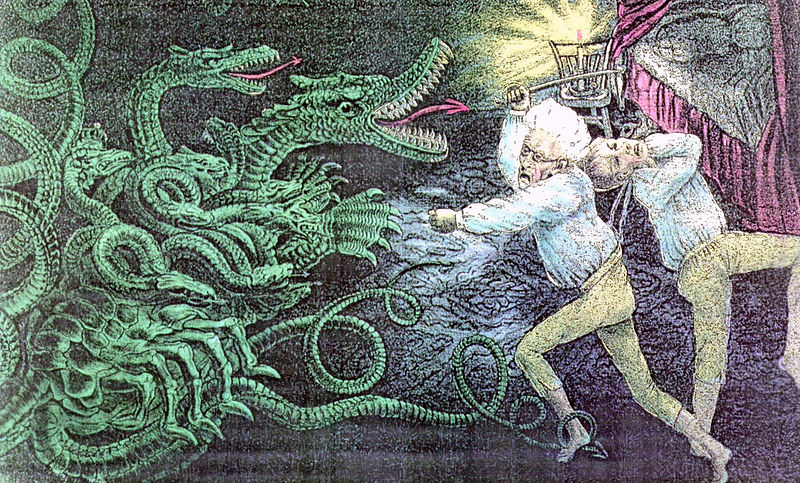

Proponents of the National Bank feared that, when it came up for its second re-chartering in 1836, Jackson would veto it without concern for the political fallout because he would be a lame duck at the tail end of his second administration. They brought it up for re-chartering four years early in the 1832 election, thinking that Jackson wouldn’t dare block it, but he called their bluff and happily “killed the monster” anyway (cartoon above).

During Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign he promised to “drain the swamp” but adopted a pro-Wall Street platform early in his presidency. Still, especially after Barack Obama tried to replace Jackson on the $20 bill with Harriet Tubman, Trump identified with Jackson’s persona and cultural populism and, like Harry Truman, named him as his favorite president, visiting his Hermitage plantation outside Nashville. Other favorites include Abraham Lincoln > George Washington, Lyndon Johnson > Franklin Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan > Calvin Coolidge, and Barack Obama > Abraham Lincoln. Advisor Steve Bannon (below right) also identified with Jackson’s economic populism, nationalism, and anti-establishment outlook.

After firing an uncooperative Treasury Secretary and listening to state bank supporters like his VP Van Buren, Andrew Jackson’s administration drained the National Bank and redistributed the money to state banks. But Jackson destroyed a system that he didn’t really understand as well as its founder, Alexander Hamilton, had. This, unfortunately, only spread the type of corruption and over-speculation in western land that Jackson feared. Old Hickory naïvely shared the common association of corruption only with higher levels of power, but it thrives in decentralized state and local settings where fewer people are paying attention. And, skipping forward a century, favoring Jackson’s vision over Hamilton’s might have exacerbated bank failures during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when many small banks had their money loaned just to local economies hurt by, say, the Dust Bowl; whereas bigger banks with local branches might’ve been able to weather the downturn because their loans were spread around (it’s counterfactual history in the U.S., but no banks failed in 1930s Canada, where they’d followed Hamilton’s model). With the Bank War, we see Jackson strengthening the executive branch in relation to Congress, but not strengthening the American economy.

Tariff of Abominations

Despite Jackson’s hostility toward the National Bank, he was somewhat of a Unionist. True, he was a slaveholder and looked out for the constituents Democrats had catered to dating back to Jefferson’s day, indicating an inclination toward states’ rights. But, banks and slavery aside, Jackson did not otherwise favor state power over the national government, at least not when he was the one presiding over the national government. The national government supported slavery anyway as of the 1830s. The controversy over tariffs, or import taxes, was a case in point that underscored Jackson’s Unionist leanings. Northern manufacturers favored protectionism to boost American industries so that they could compete with European manufacturers with access to cheaper labor. Free trade advocates they were not. Southerners had less to gain from manufacturing and relied instead on exporting cotton to Europeans, who could slap retaliatory tariffs on American imports. Tariffs only made the items they bought in the U.S. more expensive and threatened their exports, so they favored free trade.

As the tariff debate ensued, Jackson had a falling out with his vice-president, John C. Calhoun, during a soap operatic episode involving one of the cabinet member’s wives, Peggy Eaton, whose purported history as a practitioner of the world’s oldest profession ruffled other cabinet wives’ feathers. This Petticoat Affair was interesting enough in its own right (we don’t have space here), but the upshot of it was that Calhoun resigned as VP and returned to his home state of South Carolina, where he led resistance to the “tariff of abominations.” He recycled Jefferson and Madison’s old Nullification Theory from the controversy over the Sedition Act in the 1790s: the theory that states could nullify any national law they deemed unconstitutional. Sure enough, like the Sedition Act, the 1828 Tariff was unconstitutional; in this case, because it was a protective, high tariff rather than a legal, moderate, revenue-raising tariff (high tariffs don’t raise any revenue because no one imports the item). On the other hand, if any state could overturn a national law per nullification theory, then the states would have much of the power, especially if their own courts ruled on constitutionality.

Jackson thought the South Carolina Tariff Crisis, or Nullification Crisis, offered him an excellent opportunity to get in front of an army and wage war on South Carolina, ala George Washington in the Whiskey Rebellion (and, unknowingly inspire Abraham Lincoln to confront the same state when it seceded from the U.S, in 1861). Jackson was reaffirming the power of the executive branch and national government over the states. He didn’t favor the tariff but neither did he like a state defying the nation on his watch. Congress authorized military action as the Force Bill (1833) though no battle ever materialized. In the meantime, Jackson quietly went to Congress and asked them to lower the tariff, which they reduced by 50%. The combination of those two actions settled down the more rebellious Carolina Fire-Eaters. Jackson came across looking like a strong-willed Unionist but regretted for the rest of his life that he missed his chance to “hang Calhoun from the nearest tree.”

In this states’ rights struggle, ostensibly just over tariffs, slavery lurked just under the surface as a subtext. Would the national government ever have the right to outlaw slavery within the states? Jackson opined to the Washington Globe in 1833 that, after failing with tariffs, nullifiers would now turn their attention to slavery “to produce a dissolution of the Union…through the agitation of the slave question.’

Yet, in the short-term, the Tariff Crisis inadvertently delayed a sectional crisis. When Calhoun resigned from the vice-presidency (mainly because his wife refused to socialize with Peggy Eaton), Martin Van Buren replaced him. With Van Buren being from New York and Jackson from Tennessee, their administration helped forge a national identity for the Democratic Party. Rather than morphing into a regional southern and western party, they stayed strong along a north-south axis, with a common support for slavery binding them together even as the practice died out in the North. That helped stave off regional conflict for another quarter-century, though the Democrats ultimately broke apart regionally in 1860. The South seceded from the Union shortly after the Democrats split into northern and southern factions at their 1860 summer convention, vindicating Jackson’s prediction from nearly thirty years prior.

Indian Removal

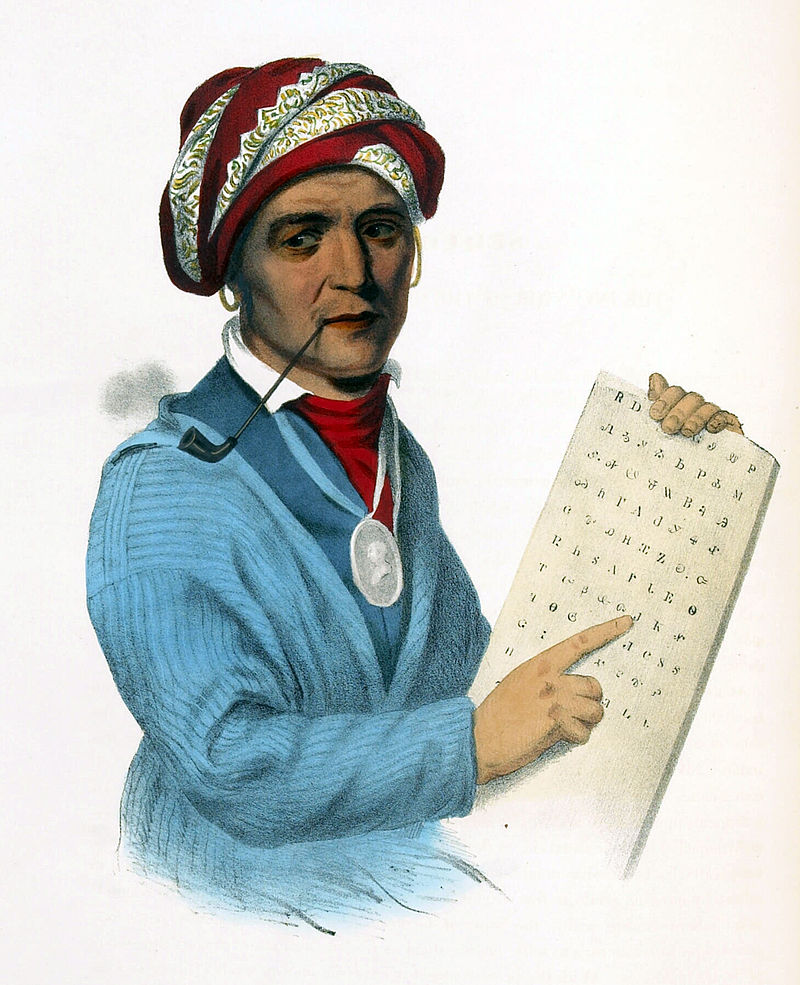

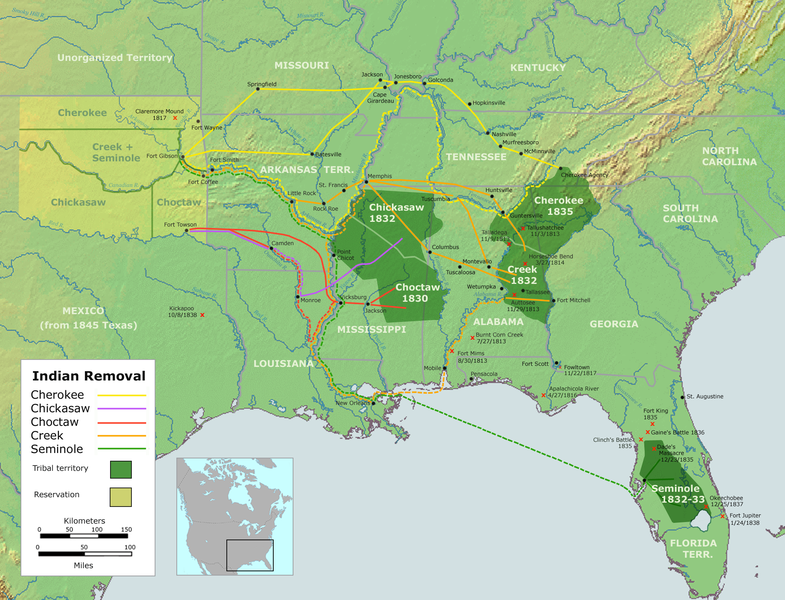

If Jackson put South Carolina in its proper place, he overstepped his bounds in his treatment of American Indians and the Supreme Court. In fairness to his harsh reputation, Jackson’s policy toward Indigenous Americans was no less enlightened in some ways than the presidents that preceded and followed. As we saw in Chapter 3, Europeans granted themselves the right to conquer and take land from anyone on Earth not ruled by a Christian sovereign through the Discovery Doctrine. As we saw in Chapter 9, George Washington saw the “merciless savages” as “wolves and beasts” that deserved nothing from Whites but “total ruin.” Washington thought buying land from Native Americans would be more cost-effective, though, than war. And as we saw in Chapter 12, a harsh policy of displacement complicated by broken treaties continued from Founders on through the administrations of Abraham Lincoln and his successors, all the way to 1890 and beyond. At the beginning of the 19th century, Thomas Jefferson told Native Americans they had to migrate west or acculturate among Whites, defined as converting to Christianity, farming instead of hunting, and developing a written language. American rulers underestimated how many groups would take them up on their offer, which some of the Five Civilized Tribes did, including even buying enslaved Africans to grow cotton. These major southeastern tribes included the Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, Cherokees, and Seminoles. Many had been settled farmers on their own for centuries. One Cherokee, Sequoyah (right), was purportedly the first known person in history to develop a written language by himself, despite not reading any other language. His wife and daughter helped him develop and match the characters to the Cherokee spoken language.

By Jackson’s administration, though, Whites coveted that cotton land and gold in the aptly-named White County, Georgia and started overturning treaties to take it for themselves. Jackson disingenuously sold his 1830 Indian Removal Act as voluntary, telling Congress that it would “be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers, and seek a home in a distant land.” The Indian Removal Act barely passed the House of Representatives, 101-97, enabling Jackson and his successor Martin Van Buren to oversee what historian Kevin Waite called the first mass, forced deportation in human history. Take a moment to scroll over the 1830s on the Invasion of America’s timeline.

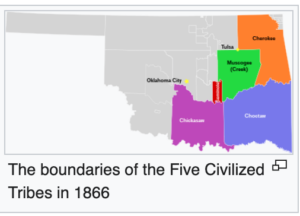

In Georgia, Cherokees led by John Ross, the son of a Cherokee mother and Scottish father, sued based on their treaties and actually won in the Supreme Court on their second try in Worcester v. Georgia (1832). But, unlike every president before and most after, Jackson didn’t honor the judicial branch as the final arbiter of American law. He purportedly told Chief Justice John Marshall to go enforce the ruling himself — really, the executive branch’s job — though Jackson later selectively endorsed judicial supremacy in the South Carolina Nullification Crisis (above). On Indian removal, Congress was nearly split and Jackson (POTUS) unconstitutionally overrode the Supreme Court (SCOTUS). Technically, the Constitution does not give the Court final say but, without that power, the judicial branch is powerless against the other two. Obviously, they don’t have an army. Ruth Bader Ginsberg didn’t drive a tank. After Marbury v. Madison (1803) politicians had agreed that the Supreme Court was the final arbiter of law, though various actors have challenged judicial supremacy, ranging from Abraham Lincoln’s GOP in the 1850s to J.D. Vance (R-OH) in the 2020s, who quoted Jackson directly. Despite the Court’s ruling that the Cherokee could remain on their property in Worcester, Jackson forced the remaining Indians west to Oklahoma, then part of the western Arkansas Territory (lower right). Oklahoma is a combination of the Choctaw words okla for people and humma for red. Ironically, Jackson and the Cherokees had been allies in his own battle against Creeks in the War of 1812, at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in Alabama.

By the time Jackson left office, nearly 50k Native American non-combatants had been pushed west in an ethnic cleansing, if one defines the term as deportation rather than outright genocide. Most deportees were southeastern, but the idea was to clear all eastern tribes (e.g. Delawares from the Ohio Valley were uprooted multiple times). Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, made those who refused to go voluntarily march west in the dead of winter, 1838, on the Trail of Tears. Thousands died on the trail of exposure, disease (cholera, flu, measles), immobility, and starvation. Seminoles, led by Osceola, held out against the U.S. Army, leading them on futile chase through the Florida Everglades. Not all Americans supported Indian Removal. SCOTUS obviously didn’t. Transcendental philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a long, angry letter to Van Buren, calling the forced march and confiscation of property an “outrage” that would make the U.S. “stink to the world.” Other white opponents of Indian removal included educator Catharine Beecher and the ABCFM that sent Protestant missionaries to the frontier and across the globe. Davy Crockett, who we’ll read more about in coming chapters, voted against it. It’s never inevitable which direction history goes, but the 19th-century U.S. Indian policy die was cast: broken treaties and deportation onto reservations.

By the time Jackson left office, nearly 50k Native American non-combatants had been pushed west in an ethnic cleansing, if one defines the term as deportation rather than outright genocide. Most deportees were southeastern, but the idea was to clear all eastern tribes (e.g. Delawares from the Ohio Valley were uprooted multiple times). Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, made those who refused to go voluntarily march west in the dead of winter, 1838, on the Trail of Tears. Thousands died on the trail of exposure, disease (cholera, flu, measles), immobility, and starvation. Seminoles, led by Osceola, held out against the U.S. Army, leading them on futile chase through the Florida Everglades. Not all Americans supported Indian Removal. SCOTUS obviously didn’t. Transcendental philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a long, angry letter to Van Buren, calling the forced march and confiscation of property an “outrage” that would make the U.S. “stink to the world.” Other white opponents of Indian removal included educator Catharine Beecher and the ABCFM that sent Protestant missionaries to the frontier and across the globe. Davy Crockett, who we’ll read more about in coming chapters, voted against it. It’s never inevitable which direction history goes, but the 19th-century U.S. Indian policy die was cast: broken treaties and deportation onto reservations.

George Catlin, Os-ce-o-lá, The Black Drink, a Warrior of Great Distinction, 1838, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Sequoyah’s 86-character syllabary helped bind together the Cherokee diaspora after they were scattered by the Indian Removal Act, ending up in Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Mexico, with some holdouts remaining in the Great Smoky Mountains.

In 2019, the Cherokee Nation named its first delegate to the House of Representatives, per the 1835 Treaty of New Echota.

Opposition to Jackson

Opposition to Jackson

Opposition to Old Hickory formed by the early 1830s, not just in reaction to his strong-armed tactics, but because the U.S. hadn’t really had two parties since the demise of the Federalists years earlier. Though the Federalists were out of the picture, their idea of a strong national government supporting business was still alive. A new party calling themselves the Whigs, led by Kentuckian Henry Clay, established a platform they called the American System: higher tariffs, renewal of the National Bank, support for education, and promotion of internal improvements (infrastructure) like roads, bridges, and canals. The Democrats said the Whigs favored industry over farming, but there was nothing anti-farming about their stance beside tariffs arguably hurting exporting cotton planters. Otherwise, most farmers stood to gain from improved infrastructure. But the Whigs included many southern Planters, too, who thought that Jackson’s conservative banking policies slowed down the growth of “King Cotton.”

The name Whigs was a clever way for the new party to shed the elitist reputation of the Federalists, but their ideas traced to Alexander Hamilton in the 1790s. Before that, the Whigs, you’ll remember, were the British party that supported the people in Parliament’s House of Commons (and American Revolution) and opposed the Tories, aristocracy, and king. The American Whigs even tried spinning Jackson as a king — an obvious contradiction in terms since he was fairly elected and grew up in a log cabin with (for a while) his single mom, but it resonated among people who thought he’d abused power. Even during his candidacy, critics feared that Jackson would become an “American [Napoleon] Bonaparte.” This turned out to be a common pattern in American politics, as opposition parties commonly accuse sitting presidents of being dictators. One lunatic tried to assassinate Jackson but, when his pistol misfired, the president beat the daylights out of him with his walking cane and tried to frame a senator he disliked. Old Hickory didn’t need the Secret Service. Davy Crockett was among those who wrestled the assassin, Richard Lawrence, to the ground. Lawrence was a house painter possibly suffering from lead poisoning.

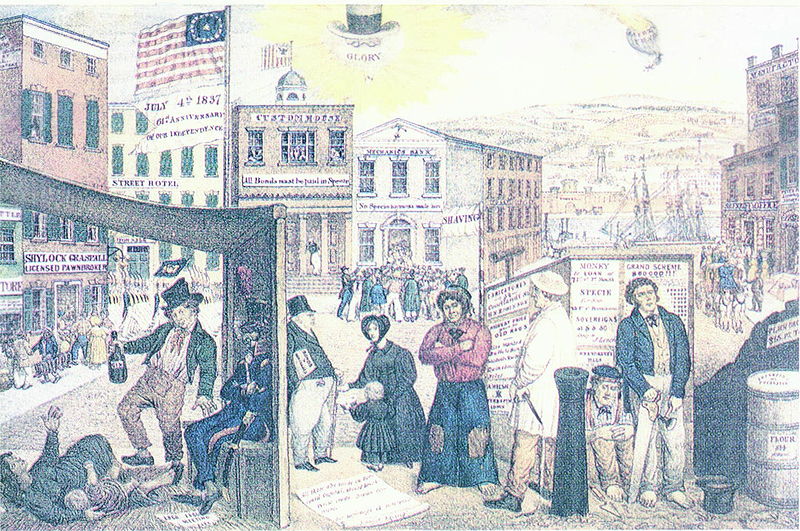

Jackson’s second term ended in March 1837, when he and his successor, Martin Van Buren, established a tradition of president-elects (Van Buren) picking up incumbents (Jackson) and traveling to the inauguration together to underscore America’s peaceful transition of power. Despite some tension here and there (e.g. Franklin Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover in 1933), this tradition mostly continued into modern times (Trump-Obama 2017), 2021 being an exception. But 1837 wasn’t really a transition of power anyway, since Van Buren was Jackson’s VP. Van Buren struggled with the country’s second recession, this one caused by another glut in the fast-growing cotton market, a Hessian fly infestation, and fallout from Jackson’s dismantling of the National Bank. Jackson’s 1836 Specie Circular mandated that all government land be purchased with gold or silver and that, combined with British banks fearing a downturn in cotton land, dried up credit, making it harder to borrow. Due to the ensuing Panic of 1837, really a severe recession that lasted until the mid-1840s, his opponents called him Martin Van Ruin and the bad economy set the table for the Whigs to make their first successful run at the White House in 1840.

1840 Election

1840 Election

Despite their different platform, Whigs copied the Democrats’ campaigning blueprint. Like Jackson, they too nominated a War of 1812 hero, William Henry Harrison, who also had a catchy nickname: Old Tippecanoe, after his 1811 victory at Tippecanoe Creek in Indiana. Democrats cried foul because of Harrison’s seeming lack of interest and experience in politics, saying that he’d never even voted and had mostly just sat on his front porch rocker drinking whiskey since the war. One Democratic newspaper opined, “Give him a barrel of hard cider and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and take my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin.” Neither charge was true. Harrison, in fact, had run for office several times and, while he ran a distillery for a while, forsook alcohol when he saw its ill effects. But justice was served. Democrats’ slanders accidentally played into Whig hands, who emphasized his apolitical, outsider status. They “took ownership” as we’d say today and even coined the phrase Log Cabin Campaign. The last thing voters want in their elected officials is a politician, a word generally spoken with a sneer on one’s face. E.C. Booz’s distillery gave voters log cabin-shaped whiskey bottles with “Tippecanoe & Tyler Too” emblazoned on them (Tyler was Harrison’s VP). Harrison caught wind of the fact that his Democratic opponent, Van Buren, had hired a French-trained chef in the White House and played up his contrasting love of “raw beef and salt.”

Harrison won the 1840 election and proceeded to give a one-hour-and-forty-minute inaugural speech in a driving sleet storm. He caught pneumonia and died a month later. Legend attributed his death not to divine punishment for his lengthy speech, but rather to the curse Shawnee Indian Tecumseh put on the U.S. at the Battle of Tippecanoe, as Harrison became the first victim of the Zero Curse. Presidents elected in a year ending in zero died in office for seven administrations in a row: Harrison, Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, Harding, Franklin Roosevelt, and Kennedy. Ronald Reagan, elected in 1980, was shot but lived, breaking the curse.

Age of the Common Man?

It’s easy for modern students, born into a democratic society, to notice the glaring limitations of the Jacksonian Era. It’s worth noting that the Democrats’ opponents, while supposedly more “elitist” in their endorsement of infrastructure and the bank, were more open to abolition and respecting the rights of women and American Indians than the working-class men who voted Democrat. To this day, elite is a slippery term in American political jargon, often a term wealthy Whites use pejoratively to discourage workers from listening to progressives. Jacksonian democracy was a decidedly white man’s democracy. Racism wasn’t something that was just taken for granted because it was an earlier era, that we notice today because we’re anachronistically applying modern standards. Once regular white men got the right to vote, they blocked women and minorities from getting that same right.

Nevertheless, with their populist appeal, early Democrats set the long-term pattern for electoral politics. Numerous movies, most famously Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, played to voters’ frustrations about a seemingly over-powerful distant government unresponsive to the people. Today’s politicians fall all over themselves to prove who is most “outside the beltway,” to use Ross Perot’s phrase from 1992, even though their obvious career goal is to be inside the beltway. We’re caught in a loop of voting people in to clean up the system who are running for office to enjoy the spoils of the system. Once in office, they can’t get anything done without making the sort of backroom deals they opposed as candidates or working with well-funded lobbies (industry representatives and interest groups) that control campaign money for the next election. If you don’t submit, your party support evaporates and no one will vote for any bills you introduce or place you on key committees. Then, come election time, campaigners use the money lobbies give them to run commercials accusing their opponent of being beholden to lobbies.

Another feature is the contest to see who can come across as most “regular,” like you and me. No campaigner in his or her right mind would consider a good education a selling point. Self-styled “populists” like Trump, Ron DeSantis, Steven Bannon, Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley, and Bill O’Reilly don’t hype their own Ivy League educations; they just tap into our hatred of “coastal elites.” Each politician, no matter how privileged, has to weave a rags-to-riches narrative into his or her biography, with parents whose calloused hands taught them the value of hard work. In keeping with Harrison’s raw beef, George H.W. Bush talked up his love of pork rinds and Bill Clinton was a fixture at McDonald’s eating Big Macs®. If you plan on running for office, your author advises against running on a pro-kale platform. Should it even be voters’ overriding goal to elect regular people to the White House? Obviously, one has to be fairly extraordinary to even aspire to higher office, as was Andrew Jackson. And what’s so great about mediocrity? But do Americans at least elect extraordinary people from ordinary backgrounds, like Jackson? It varies from year to year. In 1996, for instance, presidential candidates Clinton and Bob Dole both hailed from middle-class backgrounds, in Clinton’s case lower middle-class. But, in 2000 and 2004, when George W. Bush ran against Al Gore, Jr. and John Kerry, respectively, the election pitted sons of prominent politicians and Yale graduates against each other. In the case of Kerry and Bush, both were members of the same fraternity at Yale, Skull & Bones, a privileged group among the privileged. Privilege is still a big advantage in politics (Roosevelts, Kennedys, Bushes, Romney, Trump) and wealth is essential for an effective third-party candidate (Nader, Perot). But people from regular backgrounds with extraordinary ability and/or ambition occupy the White House around half the time (Truman, Nixon, Carter, Reagan, Clinton, Obama, Biden). Like Van Buren, their only chance was to rise up through a political party or, in Reagan’s case, gain fame in another profession first, acting. John McCain and Lyndon Johnson were tweeners, the sons of a Navy admiral/commander and state politician, respectively. The Age of Jackson, not the American Revolution, gave ordinary white men a chance to participate. The American Revolution planted the seeds of democracy that sprouted in the 19th and 20th centuries and continues to widen the pool of potential candidates in the 21st. Since 1965, the United States has been figuring out how to operate a multi-racial democracy.

Optional Reading & Researching:

Donald Ratcliffe, “The Right to Vote & the Rise of Democracy, 1787-1828” (Journal of the Early Republic, 2013) w. ACC EID

Origin of the Republican Elephant (Danbury GOP)

Hamilton Craig, “The Progressive Case For Andrew Jackson” (Compact, 10.4.22)

Walter Mead, “The Jacksonian Revolt,” (Foreign Affairs Reprint, 1.17)

Dan Jackson, “How Northern England Made the Southern United States” (History Today, 10.31.19)

Susan Glasser, “The Man Who Put Jackson In Trump’s Oval Office” [Mead] (Politico, 1.18)

Early Voting: American Election Returns, 1787-1825 (Tufts Univ.)

Sam Rosenfeld, “What Defines the Democratic Party?” (New Republic, 2.22)

Joshua Rothman, “Andrew Jackson and the C & O Canal” (We’re History, 1.29.19)