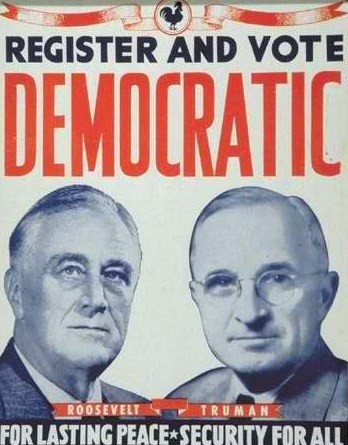

The American vice-presidency is not a powerful post, leading Franklin Roosevelt’s first VP, John Nance Garner, to complain that it was “not worth a bucket of warm piss.” However, as Americans have learned nine times — through four assassinations, four natural deaths, and one resignation — the vice-president is just a heartbeat away from the Oval Office. When FDR ran for a fourth presidential term in 1944, most expected him to retain his second VP, progressive Henry Wallace. But just as the Iowan made his way to the stage to accept the nomination at the Democratic convention amidst a cheering throng of supporters in Chicago Stadium, the chair pounded his gavel and adjourned the meeting for the day. Some reporters said he cited a fire code infraction because of the packed house. This was just as FDR planned because, contrary to public pronouncements in Wallace’s favor, he’d decided to drop him from the ticket. FDR realized he probably wouldn’t survive a fourth term and didn’t want to hand his legacy over to such a liberal idealist. Overnight, the right people were made ambassadors and postmasters and a flurry of threats, bribes, and handshakes ensued. In short, the old Democratic Party “bosses” brought the upstart liberal progressives to heel. When the convention resumed the next day, the police denied some Wallace supporters entrance and scattered the rest. The VP slot belonged to Harry Truman, a feisty, unpretentious no-name from Missouri whom FDR scarcely knew but hoped could balance his ticket and get him the same Midwestern votes Wallace delivered in 1940 without the leftist baggage.

Born in the waning days of the frontier West, Truman failed at farming, oil prospecting, and selling hats, but served admirably as a corporal in WWI. He capitalized on that to rise all the way to the U.S. Senate. Still, few Americans had heard of him. Those that had, associated him with Tom Pendergast’s notoriously corrupt Kansas City political machine, though Truman managed to keep his own nose clean enough. Nonetheless, concerns about that shady machine made Truman leery about stepping too far into the limelight, as did the fact that he’d snuck his wife, Bess, onto the Senate payroll. FDR, who was at a naval station in San Diego minding WWII and didn’t attend the 1944 Democratic convention, barely knew who Truman was. According to one witness, FDR barked into the phone at DNC Chairman Robert Hannegan loud enough that Truman could overhear: “Have you got the fellow lined up yet?” Hannegan said, “No. He is the contrariest [sic] Missouri mule I’ve ever dealt with.” FDR: “Well, tell him that if he wants to break up the Democratic Party in the middle of the war, that’s his responsibility.” Truman: “Oh s**t…I’ll have to say yes, but why in the hell didn’t he tell me in the first place?” Sure enough, Truman ended up as president shortly thereafter when FDR died in April 1945 of a cerebral hemorrhage, just a month before the war in Europe ended. NOTE: Many of the frank conversations you’ll henceforth see quoted in the text, especially from Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, aren’t from public statements but rather Dictabelt and reel-to-reel recordings presidents made in the Oval Office starting in 1940.

Born in the waning days of the frontier West, Truman failed at farming, oil prospecting, and selling hats, but served admirably as a corporal in WWI. He capitalized on that to rise all the way to the U.S. Senate. Still, few Americans had heard of him. Those that had, associated him with Tom Pendergast’s notoriously corrupt Kansas City political machine, though Truman managed to keep his own nose clean enough. Nonetheless, concerns about that shady machine made Truman leery about stepping too far into the limelight, as did the fact that he’d snuck his wife, Bess, onto the Senate payroll. FDR, who was at a naval station in San Diego minding WWII and didn’t attend the 1944 Democratic convention, barely knew who Truman was. According to one witness, FDR barked into the phone at DNC Chairman Robert Hannegan loud enough that Truman could overhear: “Have you got the fellow lined up yet?” Hannegan said, “No. He is the contrariest [sic] Missouri mule I’ve ever dealt with.” FDR: “Well, tell him that if he wants to break up the Democratic Party in the middle of the war, that’s his responsibility.” Truman: “Oh s**t…I’ll have to say yes, but why in the hell didn’t he tell me in the first place?” Sure enough, Truman ended up as president shortly thereafter when FDR died in April 1945 of a cerebral hemorrhage, just a month before the war in Europe ended. NOTE: Many of the frank conversations you’ll henceforth see quoted in the text, especially from Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, aren’t from public statements but rather Dictabelt and reel-to-reel recordings presidents made in the Oval Office starting in 1940.

Aside from handling the farming end of FDR’s New Deal, Henry Wallace was most known for advocating a constructive, even conciliatory, relationship with the Soviet Union, so it’s interesting to ponder how the Cold War would have played out had Truman not ended up on the ticket that fateful day in Chicago. For filmmaker/historian Oliver Stone, the coup d’état against Wallace at the Democratic convention was one of the tragedies of the 20th century, leading to an unnecessary Cold War and nuclear arms race (and his own fighting in Vietnam). However, after the Cold War, Soviet archives confirmed what Wallace’s skeptics in the Democratic Party charged at the time: that Wallace’s progressive wing of the Democratic Party was becoming, essentially, an infiltrated vehicle of the Communist Party USA — at least more than Wallace himself realized at the time. Historians learned more after Boris Yeltsin opened Soviet archives in 1992. Wallace even favored the USSR’s Joseph Stalin over Truman and criticized American postwar aid to Western Europe as a Wall Street plot, even though his “Global New Deal” idea promoted pretty much the same idea. That makes a Wallace presidency a compelling and/or disturbing counterfactual (what if?) scenario because the policies he advocated moved in lockstep with the Soviets in 1948, though by 1952 he viewed the USSR as evil. Truman, on the other hand, approached the Soviet Union with the containment policy we covered in the previous two chapters and bolstered democratic capitalism in Western Europe with the Marshall Plan and in Asia with support for Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. On the domestic front, Truman presided over a proud but anxious country on the cusp of the greatest economic and population boom in its history. Economy

Economy

The United States was as strong economically after WWII as it had ever been or, for that matter, as strong as any country anywhere had ever been. America produced roughly 60% of the world’s oil and steel, 80% of its cars, and owned 75% of its gold. Unions stayed strong for the next thirty years, creating a prosperous working class that, in turn, helped spur a thriving housing and consumer economy. CEOs averaged salaries 20x higher than their lowest-paid employees, compared to 300x higher today. Interest rates stayed low after the war, the GI Bill educated white veterans, and there was a lot of pent-up consumer demand after the long years of depression and war. Of course, when workers get prosperous, the GOP starts looking more appealing to them with their promise of tax cuts so, in some ways, the Democrats later became victims of their own success.

Having relied on defense spending to pull itself out of the Depression, the U.S. continued on that course, especially with the Cold War against the Soviets escalating. The America Truman inherited didn’t launch into its famous post-war economic boom immediately after the war, though. Real GDP dropped 11% from 1945 to ’46, more than twice what it fell during the Great Recession of 2007-11. There were a couple of difficult years with housing shortages and strained labor relations as the country transitioned from WWII. At stake was the question of whether the gains labor made during the Depression, including minimum wage and the right to collective bargaining, were temporary or permanent. While there were several strikes during WWII, labor and management were mostly willing to shelve the argument during the war. Once the war ended, it was game on. Management wanted the 1935 Wagner Act repealed now that the Depression was over, especially the all-important collective bargaining law that compelled management to negotiate with unions. Labor wanted to hang on to their gains and underscored their determination with the Strike Wave: series of (connected) secondary strikes in railroads, coal, steel, and autos in 1945-46.

Truman wasn’t subtle in his reaction to these unwelcome slowdowns in the economy, lambasting management and preparing to have the army take over the railroads. Next, in a potentially absurd abuse of executive powers, he threatened to draft striking coal miners into the military. Both sides, labor and management, lost faith in him. Labor responded by voting Republican in the 1946 midterm elections. Their motto of “Had Enough?” was a time-honored campaign appeal that is low-hanging fruit for any party out of power. But, once in power, the GOP’s first act was to weaken unions. Their Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 outlawed communism among labor leaders, union political contributions, closed shops (right-to-work zones replaced workplaces mandating union membership), and secondary strikes (or boycotts) whereby major unions like steel and auto would strike in unison, as they had in 1946. Truman vetoed the act, knowing that he’d be overridden, just to help win back labor for the Democrats. After the lesson of 1946, unions mostly voted straight-ticket Democrat up until the 1970s. Many union workers still vote Democrat today, though fewer than 12% of Americans now belong to unions. Later, the Supreme Court also shot down Truman’s attempt to nationalize the steel industry by declaring a national emergency just before a 1952 strike.

1948 Election

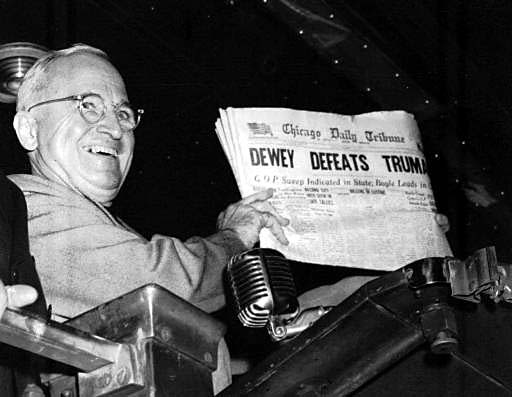

Most commentators expected Truman to lose in 1948 and the Republican nominee Thomas Dewey had a big lead that summer. Like Elliot Ness in Chicago confronting Al Capone, Dewey made his mark as a prosecutor who courageously took on the New York Mafia in the 1930s when they were at the height of their powers. Recollect how divided the Democrats had been in the 1920s along rural/urban, immigrant/WASP lines, when big-city Catholic “wets” like Al Smith failed to connect with dry, rural Protestants. Only the severity of the Depression bridged that gap, allowing FDR to launch the New Deal under the unspoken agreement that as a “party unifier” he wouldn’t push for civil rights. The Democrats stayed in power as FDR was reelected three times, but broke apart along the old fault lines of the 1920s once WWII was over. At first, Truman had doubts he could defeat Dewey, and even privately invited Dwight Eisenhower, leader of the Normandy Invasion in WWII, to take the Democratic nomination with Truman as VP.

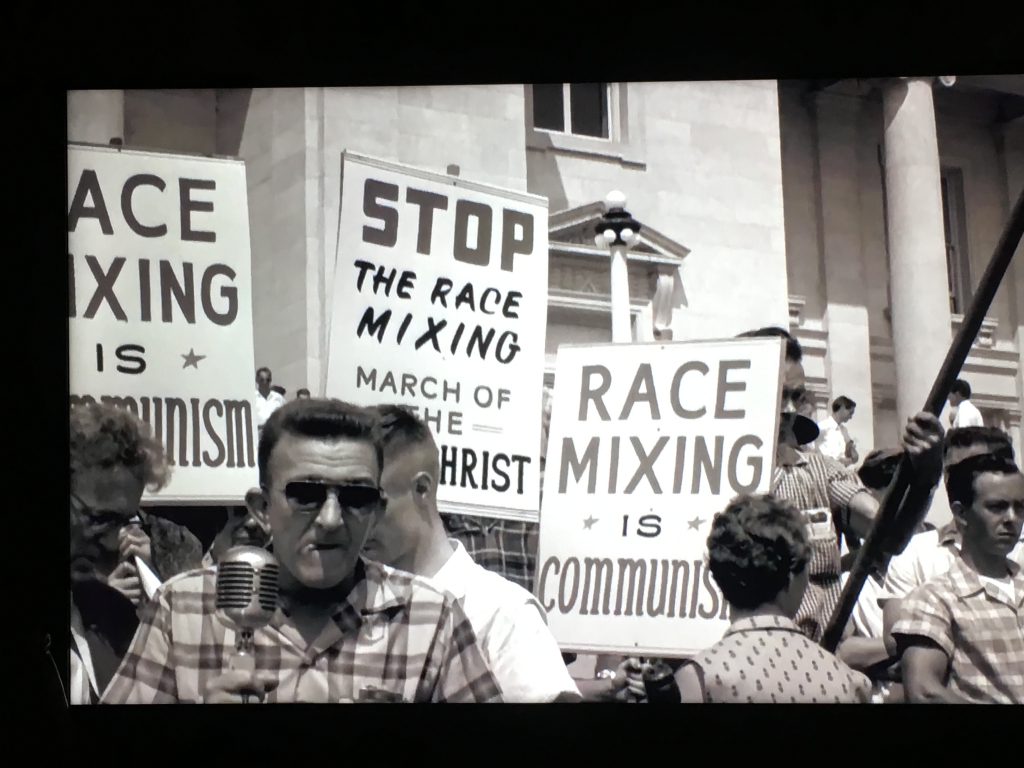

The States’ Rights Party, aka the Dixiecrats, led by Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, threatened to break away or even lead a secessionist movement if the Democrats pushed for civil rights. Some Dixiecrats also opposed continuation of the New Deal but other “Boll Weevils,” as Southern Democrats were known, supported liberal economic policies while opposing racial equality or integration. Northern Democrats ranging from near-left liberals like Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota to progressives like Henry Wallace wanted progress on both fronts and Truman was caught in between. Some progressive Democrats branched off and formed their own Progressive Party (1948-1955). The Democrats were conservative enough overall that Dewey was to their left on many issues — the last time in American history that a Republican candidate has been more liberal than a Democrat.

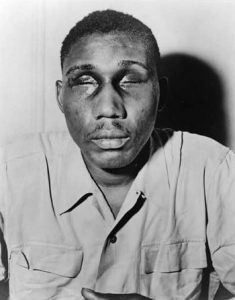

What was Truman’s response to Dixiecratic, Boll Weevil racism? The card-carrying member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who’d even flirted briefly with the Klan in 1924, spoke at the 1948 NAACP convention, campaigned in Harlem, and integrated the military and civil service, the first major institutions in American history to mix races. Truman was disgusted by a South Carolina sheriff bludgeoning out the eyes of World War II veteran Isaac Woodard (left) with a billy club while he was still in uniform, just after being honorably discharged in 1946. An all-white jury acquitted the sheriff, while Southern Democrats accused Truman of being anti-American for siding with Woodard. Truman also pressed the Justice Department to support Blacks in civil rights cases as a way to overcome the Dixiecrats. Truman took his cues from black union leader A. Philip Randolph and renegade southern Democrat Alben Barkley of Kentucky, whom he made his VP candidate. Said Barkley: “There are those who say civil rights are an infringement on states’ rights. I say it is time for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” Woodard did not lose his sight in vain. At this critical juncture in the party’s history, Truman and Barkley began to shed the Democrats’ Confederate past, even as Truman continued to use racial slurs in private. There was nothing inevitable about the Democrats’ shift, just as there was nothing inevitable about the GOP opposing civil rights legislation in the 1960s, and some didn’t.

What was Truman’s response to Dixiecratic, Boll Weevil racism? The card-carrying member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who’d even flirted briefly with the Klan in 1924, spoke at the 1948 NAACP convention, campaigned in Harlem, and integrated the military and civil service, the first major institutions in American history to mix races. Truman was disgusted by a South Carolina sheriff bludgeoning out the eyes of World War II veteran Isaac Woodard (left) with a billy club while he was still in uniform, just after being honorably discharged in 1946. An all-white jury acquitted the sheriff, while Southern Democrats accused Truman of being anti-American for siding with Woodard. Truman also pressed the Justice Department to support Blacks in civil rights cases as a way to overcome the Dixiecrats. Truman took his cues from black union leader A. Philip Randolph and renegade southern Democrat Alben Barkley of Kentucky, whom he made his VP candidate. Said Barkley: “There are those who say civil rights are an infringement on states’ rights. I say it is time for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” Woodard did not lose his sight in vain. At this critical juncture in the party’s history, Truman and Barkley began to shed the Democrats’ Confederate past, even as Truman continued to use racial slurs in private. There was nothing inevitable about the Democrats’ shift, just as there was nothing inevitable about the GOP opposing civil rights legislation in the 1960s, and some didn’t.

Additionally, Truman recognized the new nation of Israel, stating that he couldn’t recollect the Arab-American vote ever swinging an election. Still, everyone expected him to lose in 1948, including his wife Bess who wanted to return to Missouri. But Truman crisscrossed the country in an old-fashioned Whistle-Stop campaign and pulled off a shocking upset (Bess was especially shocked and upset). Since Dewey showed a commanding lead by early evening, most of the major newspapers went to press proclaiming him the victor. However, when all the electoral votes were counted by the next morning, Truman had inched ahead. The disgruntled First Lady moved back to Missouri to wait out the term.

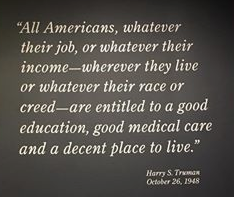

Fair Deal

In his second term, Harry Truman embraced near-left Democrats while calling progressives like Wallace “commies.” Truman pushed a platform to expand the New Deal called the Fair Deal. The Fair Deal supported civil rights legislation, universal health insurance, expansion of Social Security benefits, and repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act that weakened labor the year before. A lot of the Fair Deal was similar to what Dewey proposed for his GOP platform in the 1948 election, but out of step with what more conservative congressional Republicans and Democrats supported. A coalition of conservative northern Republicans and southern and western Democrats then called the “old guard” mostly stymied the Fair Deal. This alliance coalesced in the late 1930s to oppose further extension of FDR’s New Deal. We mentioned in Chapter 9 that the New Deal had racist aspects, but southern Democrats resented that it wasn’t racist enough and, along with western Democrats opposed to the federal government managing land and water rights, they joined with northern Republicans to oppose expanding New Deal liberalism with the Fair Deal.

This bipartisan alliance blocked civil rights legislation supporting black voting rights and prohibiting lynching up until the mid-1960s (the last confirmed black lynching in the U.S. was in Marion, Indiana in 1930, but there were others up through mid-century). Truman got legislation passed forcing the federal government to contract a small portion of its work with minority contractors in 1951. The American Medical Association (AMA), taking advantage of the capitalist-communist Cold War rivalry with the USSR, defeated Truman and military veterans on health insurance. Part of the controversy was over whether undeserving “malingerer” veterans with no real visible disabilities would soak the system to avoid working. However, unlike today, segments of the left also opposed socialized health insurance in 1948. The AFL-CIO, the biggest union in the country, favored sticking with employer-funded insurance as a way to recruit workers if they could win that benefit in negotiations.

The portions of the Fair Deal that made it through Congress were small increases in the minimum wage and expansion of social security benefits to include COLAs (1950) and disability insurance. Truman’s successor, Republican Dwight Eisenhower, infuriated the far right by adding disability insurance to Social Security in 1956. Today ~ 5% of Americans collect disability. Taft-Hartley wasn’t repealed, but neither did unions lose the basic right to collective bargaining that they’d won in the 1930s.

The Fair Deal didn’t add much ground to New Deal liberalism but, by taking the offensive, Truman helped secure the gains won in the 1930s. Sometimes in politics, failing on offense is better than or similar to playing defense. Even in failing to pass the Fair Deal, in other words, Truman cemented the New Deal. Rather than being a temporary phenomenon, the New Deal left a lasting imprint on American politics long after the Depression, up to and including the present.

With moderate Republican Dwight Eisenhower succeeding Truman from 1953-61, core New Deal liberalism like Social Security, minimum wage, and housing loans locked in. Eisenhower was on board with this liberal consensus but, toward the end of his presidency, movement conservatism emerged against his moderation led by Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan (next chapter). Ike also set aside the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) on Alaska’s North Slope, inadvertently triggering an ongoing environmental battle after oil was discovered there in 1968. While he barked about democratic socialism in the 1952 campaign, Eisenhower later said, “Should any party attempt to abolish social security unemployment insurance and eliminate labor laws and farm programs you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do such things. Among them are…Texas millionaires and an occasional politician or business man from other areas. Their number is negligible and they are stupid.” His prediction proved debatable, but it underscores how fundamentally New Deal liberalism was ensconced after WWII as the domestic political spectrum temporarily narrowed. Perhaps that’s because Americans had more urgent things to worry about, like the end of the world.

McCarthyism

Truman’s second term failure resulted less from Fair Deal resistance than from the worsening Cold War, especially the way the Soviet threat played out at home. Truman’s early containment policy succeeded insofar as the U.S. managed to stave off communism in Greece, Turkey, and Iran with no combat troops, and the Soviets hadn’t advanced in central Europe beyond Czechoslovakia. Truman’s diplomatic even-handedness was a big factor in helping him win reelection in 1948. But in his second term, the U.S. experienced several setbacks in the Cold War, including the Soviets exploding an atomic bomb, spy scandals at home, and a communist takeover of China in 1949. Worse, the first two were connected. Klaus Fuchs, a German-British physicist working on the Manhattan Project, sold breakthrough secrets to the Soviets. In fairness, China was not really Truman’s to lose, but TIME’s Henry Luce flayed Truman mercilessly for “losing China” and being soft on communism, which was a factor in motivating him to defend South Korea, though that wasn’t enough for some either. But the same folks trashing Truman on the right — Luce, the Chicago Tribune, and retired Herbert Hoover — were simultaneously accusing him of having committed war crimes in dropping the atomic bombs on Japan in 1945, indicating that a lot of their overseas concern was just domestic mud-tossing. But the public also sided with General Douglas MacArthur in his fight with Truman over whether America should have invaded China during the Korean War (chapter 13). TIME and LIFE were among the mainstream magazines that informed middle-class Americans at the time, along with Saturday Evening Post.

In this charged atmosphere, any man who didn’t knock himself out being “tough on communism” ran the danger of being considered a “fellow traveler” himself (fellow communist). The State Department even fired East Asian experts as an irrational reaction to China’s revolution, leaving the U.S. with no one in the government who spoke Korean or Vietnamese when wars broke out there later. Rather than stand up to the criticism, Truman pandered to the hysteria by instituting loyalty oaths and reviving the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), a panel started in the House of Representatives in the late 1930s to ferret out right-wing influence (Nazi and Klan) in the government. FDR also used the FBI to hunt down left- and right-wing radicals during World War II. The new enemy within was on the left and seemingly no one was above being accused of communism. The CIA and FBI were rightfully finding out what they could about real Soviet espionage and some branches of the government, including the Army, struggled to control espionage. HUAC, though, made a public spectacle of the country’s worst tendencies, including political backstabbing and paranoia. In hoping to defuse his critics, Truman fanned the flames when he should have used an extinguisher instead of bellows on HUAC and just made sure the FBI and CIA were adequately staffed to hunt real spies.

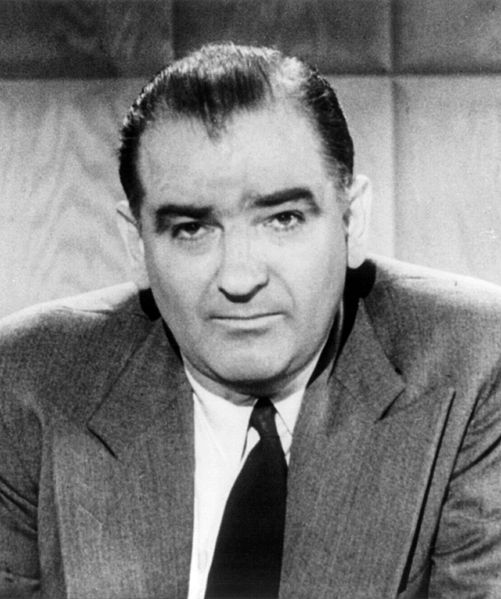

Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) wasn’t on HUAC but chaired similar committees in the Senate. After 1950, he manipulated the spirit HUAC had whipped up from 1947-50. McCarthy was known as “Tail Gunner” for his role in WWII, even though he only occasionally rode along observing on bombing missions as an intelligence officer. He was a tough, energetic, self-educated farm boy and boxer from Appleton, Wisconsin who was a Democrat during the New Deal but switched to the right-wing of the Republican Party. In Washington, though, he was more of a loner than a Republican team player. In February 1950, McCarthy made his initial splash by holding up a sheet of paper with purported names of communist infiltrators at a Republican Women’s Club fundraiser in Wheeling, West Virginia. He sought attention because he was virtually unknown outside his state and higher-profile Republicans were sent to bigger cities than Wheeling for such Lincoln Day dinners.

McCarthy quickly realized that he could destroy pretty much anyone’s career simply by accusing him of being communist, all while raising his own profile. In such a heated environment, the accusation alone sufficed, even without real evidence. If the victim fought back, that merely proved his guilt. McCarthy went so far as to encourage government employees to sift through one another’s files and spy on each other. Anyone who challenged him was “red,” as journalist Drew Pearson discovered. Some Democrats flocked to McCarthy out of fear, including the Kennedys. Young Bobby Kennedy went to work for him as a legal aide while father Joseph, Sr. encouraged his daughters to date him. With their leftist leanings, former New Dealers were subject to attack, but McCarthy steered clear of attacking Franklin Roosevelt. Oftentimes when he saw his victims off-camera, he would apologize and ask them to not take anything personally, suggesting that the whole thing was a kind of theater. Pearson, who unbeknownst to McCarthy was involved in covert ops fighting communism in Western Europe, wrote columns critical of the Wisconsin senator starting in 1950.

Just as Democrats took advantage of Republican resistance to fighting Germany in the late 1930s by associating them with fascism through brown-baiting, now Republicans and conservative Democrats smeared liberals with communism through red-baiting. Even lacking PhotoShop®, they still pasted together pictures of liberal Democrats with communists, similar to Donald Trump’s 2020 re-Tweeting® of Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) wearing turbans. Red-baiting was at odds with what the CIA was trying to accomplish in Western Europe, where their goal was to buttress liberalism to fend off far-left communism. An instrument as blunt as McCarthy would’ve backfired in Europe, opening the door for communism. In America, only a few brave souls stood up to McCarthy, most notably fellow Republican Margaret Chase Smith of Maine, who criticized the “reckless abandon in which unproved charges have been hurled from this side of the aisle.” Out of step with her times, Smith was of the bizarre opinion that Americans had a right to freedom of conscience and speech. Other politicians of both parties criticized McCarthyism behind closed doors but went along with it to placate their constituents.

Recently, some commentators have tried to revive McCarthy’s reputation because it became apparent after the Cold War ended in 1991 that the Soviets indeed had spies throughout the U.S. government and were influential in the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). Both the Americans and Soviets, in fact, infiltrated each other’s governments, nuclear research, militaries, and intelligence agencies. There was the aforementioned Fuchs and, as we saw in Chapter 13, David Greenglass passed critical information to his brother-in-law, Julius Rosenberg. Harry Dexter White in the Treasury Department, who helped shape the Free World’s post-war economic policy, was a Soviet informer during WWII (though, technically, they were then allies). Not all this came to light after the Cold War ended; defecting Soviet spy Elizabeth Bentley named names to the FBI in the 1940s. For reasons like these, the Texas State Board of Education pushed to vindicate McCarthy’s legacy in the states’ public schools in the early 21st century.

But McCarthy wasn’t involved in counter-espionage intelligence such as the Venona Project, leaving him with little more knowledge about Soviet spies than the average man on the street, other than what he heard from others, like Bentley. Post-Cold War revelations show that McCarthy wasn’t insane or irrationally paranoid for suspecting such infiltration, warranting a revised interpretation among any historians who argued otherwise or thought men like Fuchs or Rosenberg were innocent scapegoats. But while some of McCarthy’s charges were true, others were imagined. There’s not enough overlap between real Soviet spies and those McCarthy accused of communist infiltration to rehabilitate his reputation, and he attacked too many non-spies simply for leaning left. Library of Congress historian John Earl Haynes showed that only nine of the 159 names on McCarthy’s subversive lists were actually spies, and a dozen or so others were more sympathetic to Stalin than one might hope and/or security risks (Newsday). At most, that’s 21 of 159 names he smeared that were actually guilty. Really it was nine, since being an American leftist isn’t illegal or treasonous, any more so than being a right-wing member of the John Birch Society or apostle of Ayn Rand. Political freedom is the very trait that most distinguishes free societies from unfree.

Moreover, if McCarthy did have inside knowledge of Venona and revealed names, he would’ve treasonously exposed key secrets, accidentally blowing the operation’s cover. If anything, his unsubstantiated claims gave cover to real spies who could claim that they were being unfairly targeted like other McCarthy victims. Historian Harvey Khler, author of Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, argues that McCarthy’s “wild charges actually made the fight against Soviet communism more difficult.”

The Catholic senator also targeted a disproportionate number of Jews and homosexuals. If McCarthy had been discovering and fingering actual spies outside the top-secret Venona Project, then not only would a revisionist upgrade be in order, we should build a memorial in D.C. to honor the man. But he wasn’t, so we should recognize him for what he was: mainly a cynical opportunist gasbag who lacked any sense of decency and justice. His legacy was manipulating and exposing the paranoid tendencies of an anxious society. Texas Ranger Norm Dixon, chief of internal security and fighting communists in Texas, said of McCarthy: “swatting everything that looked like a mosquito never whipped malaria.”

Red Scare

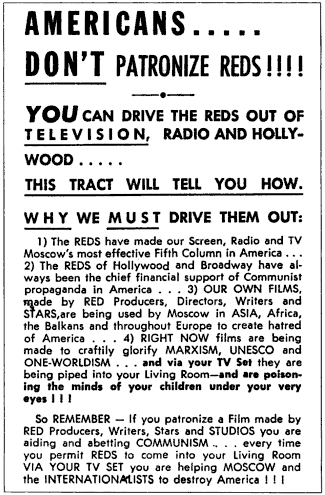

Paranoia within the government spread to the rest of society and popular culture in the Red Scare, the second and more famous in America’s history after an earlier post-WWI outbreak. The Cincinnati Reds baseball team changed their name to the Redlegs just to counter any suspicions as to their political leanings. Hollywood conservatives led by John Wayne, Walt Disney, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Ronald Reagan, Barbara Stanwyck, Ginger Rogers, and Cecile B. Demille led a blacklisting of leftist actors, writers, and directors, trying to push them out of the industry. These actors and directors wouldn’t necessarily have seen themselves as right-wingers on a left-wing witch-hunt, so much as centrists defending America from a menacing threat of surrounding “isms” (people often forget that everyone who cares believes in some sort of ism). Both communism and fascism seemed like real threats in the late 1940s, justifiably enough considering recent history. Here’s the mission statement of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (or MPA):

We believe in, and like, the American way of life: the liberty and freedom which generations before us have fought to create and preserve; the freedom to speak, to think, to live, to worship, to work, and to govern ourselves as individuals, as free men; the right to succeed or fail as free men, according to the measure of our ability and our strength. Believing in these things, we find ourselves in sharp revolt against a rising tide of communism, fascism, and kindred beliefs, that seek by subversive means to undermine and change this way of life; groups that have forfeited their right to exist in this country of ours, because they seek to achieve their change by means other than the vested procedure of the ballot and to deny the right of the majority opinion of the people to rule. In our special field of motion pictures, we resent the growing impression that this industry is made of, and dominated by, Communists, radicals, and crackpots. We believe that we represent the vast majority of the people who serve this great medium of expression. But unfortunately it has been an unorganized majority. This has been almost inevitable. The very love of freedom, of the rights of the individual, make this great majority reluctant to organize. But now we must, or we shall meanly lose “the last, best hope on earth.”

There were many reasonable people in Hollywood who genuinely felt the democratic system itself was at risk and wanted to defend their industry from anyone who threatened it, regardless of who they were. While historians locate them on the right side of the political spectrum, they likely envisioned themselves surrounded by concentric circles of radicalism. The Ku Klux Klan sued Warner Brothers for defamation because of their negative portrayal in Black Legion (1937) and Ronald Reagan, Ginger Rogers, and Doris Day starred in the anti-Klan Storm Warning (1951) at the height of the Red Scare. In The FBI Story (1959), Jimmy Stewart arrests communists but spends equal time going after the KKK, describing them as “opposed to the Bill of Rights.” Likewise, the real FBI under J. Edgar Hoover didn’t just go after leftists, but also the Klan, at least kind of. As historian David Cunningham pointed out, “when pressed to target KKK violence, FBI agents worked to control the Klan’s flaunting of law and order while tacitly supporting its continued presence in communities.”

The MPA formed in 1944, when fascist Germany was still a threat, though there weren’t any active fascist actors or directors in the industry — only anti-Nazi refugees like Fritz Lang, Paul Henreid, and Peter Lorre. By the late 1940s, the alliance’s stance was predicated on the idea that left-leaning actors, writers, and directors wanted to attain power through subversion, revolt, or dismantling the voting system after winning office. Their “blacklist” never had any formal legal authority, but it damaged careers and included people who weren’t communists or didn’t pose any active threat to American democracy. Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, and Frederick March, for instance, were on the list. By taking the “camel’s nose under the tent” slippery slope argument too far, the MPA was instead merely silencing the voices of those they disagreed with. While not technically a violation of free speech rights — only the government itself could be guilty of that — it hypocritically violated the spirit of free speech they mention in the opening paragraph above as worth defending. It was a right-wing version of cancel culture and, like today’s illiberal left, John Wayne and Walt Disney brooked no dissent. Disney, then battling unionized cartoonists, spoke for the alliance when he warned, “Don’t smear the free enterprise system…Don’t smear industrialists…Don’t smear wealth…Don’t smear the profit motive…Don’t deify the common man…Don’t glorify the collective.” It’s a big Lion King-size leap from we’ve been infiltrated to don’t deify American commoners. Really, few leftist actors or directors had any intention of abolishing voting or dismantling the system. In response to the MPA, other actors including Myrna Loy, Henry Fonda, Danny Kaye, Groucho Marx, Lucille Ball, Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland, Katherine Hepburn, and Frank Sinatra organized a Committee for the First Amendment. Bogart and Edward G. Robinson were on the First Amendment Committee initially but withdrew their support when they discovered that some of the Hollywood Ten fired from the industry (Dalton Trumbo and John Howard Lawson) had really been communists.

The MPA formed in 1944, when fascist Germany was still a threat, though there weren’t any active fascist actors or directors in the industry — only anti-Nazi refugees like Fritz Lang, Paul Henreid, and Peter Lorre. By the late 1940s, the alliance’s stance was predicated on the idea that left-leaning actors, writers, and directors wanted to attain power through subversion, revolt, or dismantling the voting system after winning office. Their “blacklist” never had any formal legal authority, but it damaged careers and included people who weren’t communists or didn’t pose any active threat to American democracy. Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, and Frederick March, for instance, were on the list. By taking the “camel’s nose under the tent” slippery slope argument too far, the MPA was instead merely silencing the voices of those they disagreed with. While not technically a violation of free speech rights — only the government itself could be guilty of that — it hypocritically violated the spirit of free speech they mention in the opening paragraph above as worth defending. It was a right-wing version of cancel culture and, like today’s illiberal left, John Wayne and Walt Disney brooked no dissent. Disney, then battling unionized cartoonists, spoke for the alliance when he warned, “Don’t smear the free enterprise system…Don’t smear industrialists…Don’t smear wealth…Don’t smear the profit motive…Don’t deify the common man…Don’t glorify the collective.” It’s a big Lion King-size leap from we’ve been infiltrated to don’t deify American commoners. Really, few leftist actors or directors had any intention of abolishing voting or dismantling the system. In response to the MPA, other actors including Myrna Loy, Henry Fonda, Danny Kaye, Groucho Marx, Lucille Ball, Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland, Katherine Hepburn, and Frank Sinatra organized a Committee for the First Amendment. Bogart and Edward G. Robinson were on the First Amendment Committee initially but withdrew their support when they discovered that some of the Hollywood Ten fired from the industry (Dalton Trumbo and John Howard Lawson) had really been communists.

Free speech was a legally relevant issue once the MPA began testifying before Congress in 1947. HUAC interrogations of Hollywood leftists like John Garfield were among the most notorious violations of the First Amendment in American history, along with the Sedition Acts of the 1790s and World War I. Imagine what would happen had congressional Democrats interrogated Clint Eastwood, Arnold Schwarzenegger or Mel Gibson under suspicion of being conservative and they were kicked out of the industry, with Eastwood forced to “ghost direct” under a pseudonym. It would’ve been outrageous and implausible for a variety of reasons, including the simple fact that being conservative isn’t illegal in a free society. The differentiating factor in the early Cold War was the threat of Soviet infiltration, but the Soviets never infiltrated Hollywood. Screenwriter and ex-communist Martin Berkeley salvaged his career in the 1950s by ratting out 150 colleagues. Director Orson Welles observed that “witnesses weren’t testifying to save their lives; they testified to save their swimming pools.”

In the end, around fifty directors and producers signed on to blacklist anyone who wouldn’t submit to interrogation before the House Un-American Activities Committee. One victim of the Hollywood Blacklist, Arthur Miller, wrote a metaphoric attack on this culture of suspicion called The Crucible (1953). The play concerned the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 when people were killed simply for being accused rather than proven guilty. Miller couldn’t write a play about the Red Scare itself for obvious reasons. While it surely traumatized Miller being interrogated and charged with contempt of Congress for refusing to rat out other leftists, it no doubt comforted him to have his future wife Marilyn Monroe at his side during the hearings.

Eisenhower & McCarthyism

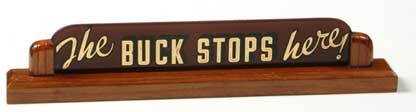

McCarthy stole Truman’s thunder in the early 1950s. By reinvigorating HUAC, Truman fanned flames that, if they didn’t consume him personally, at least displaced whatever momentum the Fair Deal agenda would’ve otherwise had. About ¼ of Americans read Hearst newspapers that backed McCarthy. In 1952, the Democrats took the unusual action of not nominating Truman for another term even though he was eligible. As more Americans came to appreciate civil rights reform, Medicare, and the early success of Cold War containment strategy, Truman’s stock rose among historians. However, his 22% approval ratings shortly before he left office are still the lowest in history — lower even than Richard Nixon when he resigned in disgrace in 1974 as he was being impeached. A common joke went that “to err is Truman.” In truth, when people say they want a “strong leader,” what they really mean is that they want a leader to stand up to people they disagree with while caving in to their own wishes. Politicians like Truman, that actually have a spine, are bound to alienate nearly everyone given enough time. Then, years later, when a contemporary politician craters on behalf of a policy someone opposes, they lament that a “guy like Truman” isn’t around anymore to take charge and say “the Buck stops here!”

“The Buck Stops Here” Sign From President Truman’s White House Desk, From Federal Reformatory in El Reno, Oklahoma, Truman Library & Museum

At the time, Truman hadn’t yet aged like a fine wine in history books and Democrats hoped to nominate popular war hero Dwight Eisenhower, aka “Ike,” as their candidate. Ike was a centrist and wasn’t sure at first which party he’d belong to were he to become a politician, but he eventually accepted the Republican nomination. As NATO commander, he also wanted to displace potential GOP candidate Robert Taft because he saw him as too isolationist. Ike saw the early Cold War as the wrong time for America to turn inward again, the way it had after World War I, and Taft didn’t support NATO.

The outwardly affable Ike won the election and served two terms, from 1953-61. He gave people the impression of being simpler and more easygoing than he really was, but no one rises through the ranks of the military to lead the European effort in World War II without being bright and cunning. Anyone unfortunate enough to sit down at the bridge or poker table with Ike discovered that in short order. This was the man, after all, who tricked Hitler into thinking the Allied invasion of 1944 was planned for a different spot.

The outwardly affable Ike won the election and served two terms, from 1953-61. He gave people the impression of being simpler and more easygoing than he really was, but no one rises through the ranks of the military to lead the European effort in World War II without being bright and cunning. Anyone unfortunate enough to sit down at the bridge or poker table with Ike discovered that in short order. This was the man, after all, who tricked Hitler into thinking the Allied invasion of 1944 was planned for a different spot.

Eisenhower demonstrated his political prowess by nominating Richard Nixon as his VP running mate. Nixon was so adamantly anti-communist that it inoculated Ike against McCarthy’s attacks. Nixon earned his nickname “Tricky Dick” in a 1950 California senatorial race against Helen Gahagan Douglas, former actress and lover of Texas Congressman Lyndon Johnson. Picking up on a line from some of her earlier opponents in the primary, Tricky Dick argued that anyone open to civil rights progress for Blacks must be a Soviet sympathizer. It says a lot about the contradictory state of early Cold War America that anyone who endorsed true democracy by opposing racism was suspected of being a communist, providing fodder for enemy propagandists. There’s a saying that politics can make for strange bedfellows. In this case, many of America’s most ardent anti-communists unwittingly agreed with Soviets that racism was a core American value — so definitional that any non-racist couldn’t be a true American. Yikes! Included among the Hollywood Ten was the director of Crossfire (1947), a noirish social drama that condemned anti-Semitism and racism in general but had nothing whatsoever to do with communism.

Exploiting anti-communist hysteria and misogyny simultaneously, Nixon accused Helen Douglas of being “pink down to her underwear” and won the race, even garnering some secret funds from Democrat John Kennedy. All of us have good and bad instincts, and politicians like Nixon can succeed in democracies by appealing to the latter.  However, he nearly torpedoed Ike’s campaign with an illegal fund-raising snafu. Nixon rectified the situation with his infamous Checkers Speech, in which he apologized for taking illegal contributions but refused to return one critical gift: a pet Cocker Spaniel puppy named “Checkers” that he’d given to his children. It was a good example of spinning a potentially negative incident to one’s advantage. Voters don’t care about anything else once they’re thinking of puppies. Canines can play a big role in politics. In 1944, FDR scored points at a Teamster’s Convention in the wake of Republican rumors that he’d wasted taxpayer dollars using a destroyer to rescue his Scottish Terrier Fala, who’d been left behind in the Aleutian Islands after a conference. To uproarious applause, Roosevelt said, “I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks…but Fala resents attacks!” A study during the 1992 presidential election found that, while only 15% of the voters knew the candidates’ stance on the death penalty and 5% on the capital gains tax, 86% knew that the Bush’s dog was named “Millie.” In America, presidential dogs are obligatory (pet list).

However, he nearly torpedoed Ike’s campaign with an illegal fund-raising snafu. Nixon rectified the situation with his infamous Checkers Speech, in which he apologized for taking illegal contributions but refused to return one critical gift: a pet Cocker Spaniel puppy named “Checkers” that he’d given to his children. It was a good example of spinning a potentially negative incident to one’s advantage. Voters don’t care about anything else once they’re thinking of puppies. Canines can play a big role in politics. In 1944, FDR scored points at a Teamster’s Convention in the wake of Republican rumors that he’d wasted taxpayer dollars using a destroyer to rescue his Scottish Terrier Fala, who’d been left behind in the Aleutian Islands after a conference. To uproarious applause, Roosevelt said, “I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks…but Fala resents attacks!” A study during the 1992 presidential election found that, while only 15% of the voters knew the candidates’ stance on the death penalty and 5% on the capital gains tax, 86% knew that the Bush’s dog was named “Millie.” In America, presidential dogs are obligatory (pet list).

Eisenhower thought Nixon was a creep but this was the height of the McCarthy era and he needed someone to stay on the anti-communist offensive when the situation called for it. By letting Nixon be his equivalent of a hockey enforcer or “goon,” he could maintain his dignity by staying above the fray himself. As a young Congressman from California, Nixon earned his stripes through his investigation of diplomat Alger Hiss. Nixon based his investigation on the charges of Whittaker Chambers, himself a former courier for the Soviet underground who’d renounced communism. There’s a near consensus today that Hiss was a Soviet spy, but we’ll know more when HUAC files are unsealed in 2026.

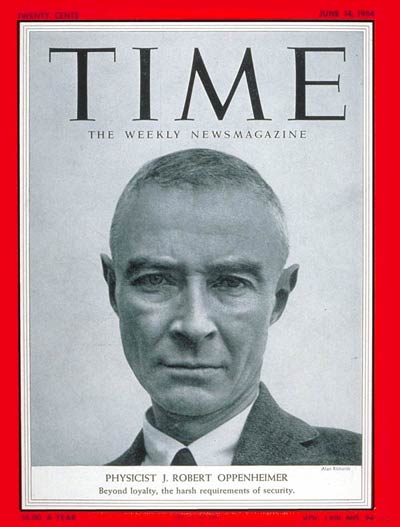

The Atomic Energy Commission that grew out of the Manhattan Project was in a paranoid frame of mind after the Klaus Fuchs and Alger Hiss revelations. The AEC revoked security clearance for J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “Father of the Atomic Bomb” who disapproved of the new hydrogen bombs. Edward Teller, who favored the hydrogen bomb as a way to deter future Hitlers, testified against Oppenheimer, who was suspected of being a communist and spy. Of course, if Oppenheimer had been a spy he likely would’ve just worked on the hydrogen bomb rather than resist it. Thus, the McCarthy-era government questioned the loyalty and disgraced the legacy of the man who brought an early end to WWII. Soviet archives declassified by Russia in 2014 show that the KGB saw no hope in recruiting the left-leaning Oppenheimer despite a preponderance of his grad students, along with his wife and sisters, being communists. After outing his marital affairs and ruining his career, the AEC board revoked his clearance because of “unreliability” but ruled that he was innocent of being a spy.

The Atomic Energy Commission that grew out of the Manhattan Project was in a paranoid frame of mind after the Klaus Fuchs and Alger Hiss revelations. The AEC revoked security clearance for J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “Father of the Atomic Bomb” who disapproved of the new hydrogen bombs. Edward Teller, who favored the hydrogen bomb as a way to deter future Hitlers, testified against Oppenheimer, who was suspected of being a communist and spy. Of course, if Oppenheimer had been a spy he likely would’ve just worked on the hydrogen bomb rather than resist it. Thus, the McCarthy-era government questioned the loyalty and disgraced the legacy of the man who brought an early end to WWII. Soviet archives declassified by Russia in 2014 show that the KGB saw no hope in recruiting the left-leaning Oppenheimer despite a preponderance of his grad students, along with his wife and sisters, being communists. After outing his marital affairs and ruining his career, the AEC board revoked his clearance because of “unreliability” but ruled that he was innocent of being a spy.

As for Joe McCarthy, he and Ike danced around each other cautiously, at least at first. Publicly the new president said that, while he appreciated congressional work (i.e., HUAC and McCarthy in the Senate), investigations into communist subversion would now lie squarely on the shoulders of the executive branch. Also, in keeping with American principles, suspects would be considered innocent until proven guilty. That was a thinly veiled slam on McCarthy, but Ike later said he didn’t want to get into a “pissing contest with a skunk.” (He may not have realized that, when McCarthy was a young politician campaigning in Wisconsin, he used to establish his down-home credibility by saying that, as a boy, he’d been tasked with the dirty work of killing skunks.) McCarthy, in turn, formally endorsed “the General,” as he called Ike, but wished that it were he, rather than Ike, in the Oval Office. He technically had more power than ever, chairing a committee on government operations with the GOP in firm control of the Senate, but his influence was waning. He sent two agents to Europe to review the libraries of American embassies abroad and make sure they didn’t contain leftist literature. That trip didn’t go well and European and American presses mocked the agents. McCarthy was the last thing the U.S. needed in Europe as it tried to persuade leftists on the merits of democratic capitalism. Eventually, Ike called anti-communist rhetoric “tragically stupid and ultimately worthless.” After McCarthy’s library tour, Ike made a commencement speech at Dartmouth where he warned: “Don’t join the book burners. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book…how will we defeat communism, unless we know what it is and what it teaches and why it [has] appeal for so many?”

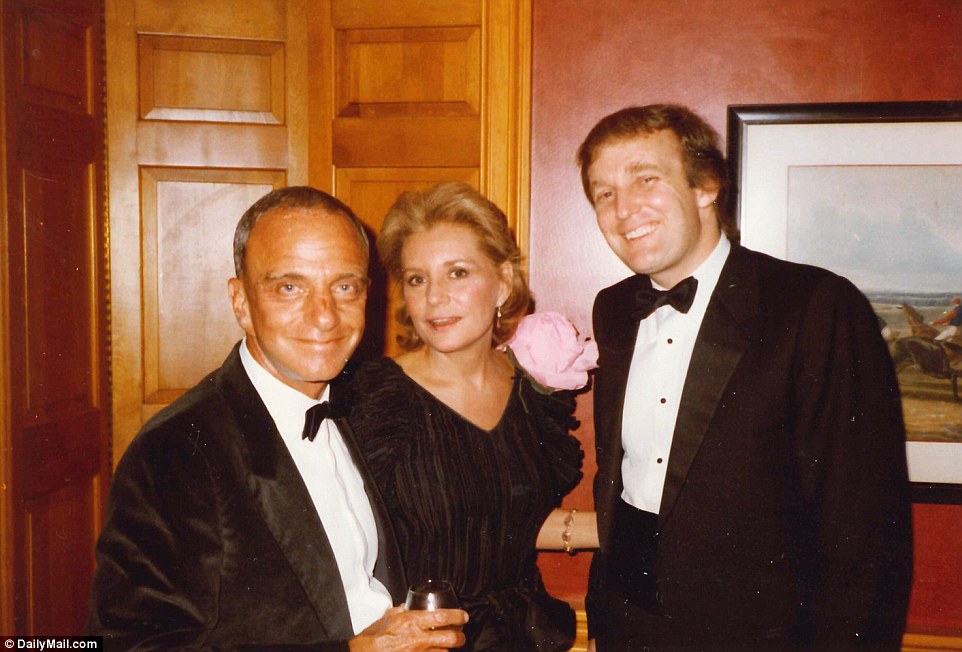

McCarthy eventually went too far by investigating the CIA and its director Allen Dulles, and George Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff in WWII. He didn’t accuse Marshall directly of treason but attacked high-ranking brass for allowing smaller-scale communist infiltration among the signal corps at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where the forenamed Julius Rosenberg worked. Dulles told Eisenhower he’d resign if McCarthy didn’t steer clear of the CIA and Eisenhower was protective of the Army as well. During the 1954 Army-McCarthy Hearings, the Army charged that McCarthy’s staff sought favor within the service for a man that McCarthy’s chief aide, Roy Cohn, purportedly had an affair with. Historians now think the man in question, G. David Shine, was heterosexual, but the tactic worked. The Army fended off McCarthy by threatening to out Cohn. Cohn went on to provide legal counsel to Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, Aristotle Onassis, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, and Mafiosi Tony Salerno, Carmine Galante, and John Gotti. He was Rupert Murdoch and Donald Trump’s lawyer in the 1970s but was disbarred in 1986 on ethics charges and died of AIDS later that year. He helped hone Trump’s combative style whereby he stays on the offensive. As Truman said: “There is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know.”

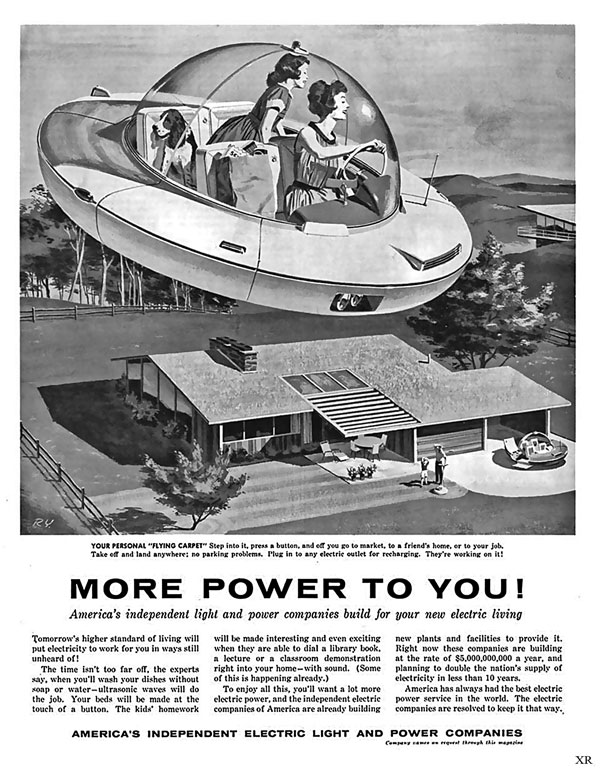

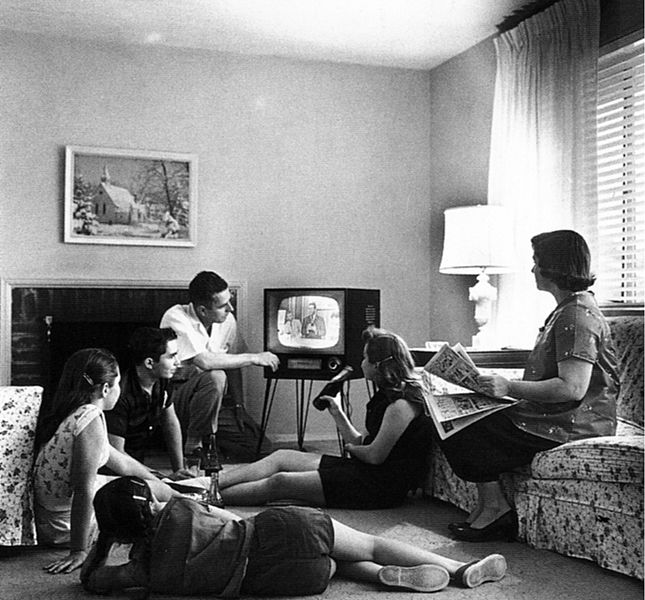

The media, not the Army, is who really brought down McCarthy. Television’s growth slowed in the early 1940s, with copper, rubber, and tungsten diverted for the war, but started to go mainstream in the late 1940s. Ownership grew from 3 million to 55 million TVs during the 1950s. By McCarthy’s time, most middle-class homes had a set that showed single-sponsor shows in the evenings. As more Americans got TVs and saw McCarthy in action the public turned on him, especially after an hour-long documentary by journalist Edward R. Murrow, who courageously urged Americans to not confuse dissent with disloyalty. An earlier McCarthy critic, who coined the term McCarthyism, was the Washington Post’s Herbert Block, whose daily Herblock cartoons insightfully critiqued American politics from 1929-2001. Another cartoonist, Walt Kelly, joined Block in 1953. After the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812, U.S. Navy Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry famously said, “We have met the enemy, and they are ours.” Kelly’s Pogo character paraphrased, in reference to McCarthyism: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” Journalists like Murrow, Block, and Kelly turned the tide and Eisenhower joked that McCarthyism had turned to McCarthywasm.

In 1954, McCarthy confidently talked about the positive impact television would have on his mission, saying, “I think — and I’m glad we’re on television — I think the millions of people can see how low that a man can sink. I repeat: They can see how low an, an alleged man, can sink.” He was right but the person they saw sinking was McCarthy, not the defendants. That year, the Army-McCarthy Hearings were the first time most Americans saw “Tail-Gunner Joe” on TV and many didn’t like him, especially with McCarthy appearing intoxicated during the afternoon sessions. Army lawyer Joseph Welch famously stood up to him, asking “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last?” The Senate censured him though some congressmen, like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, were still too scared to vote against him. McCarthy died from alcohol-related hepatitis in 1957, at age 48.

Military Industrial Complex

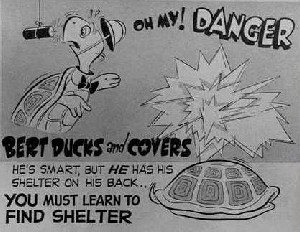

Eisenhower’s domestic agenda was closely tied to Cold War foreign policy, emphasizing military spending as a way to keep pace with the USSR. Fearing nuclear war, some people were building fallout shelters in their backyards with weeks worth of dry foodstuffs and supplies. The nice ones even had wet bars. Schools showed kids cartoons featuring a turtle named Bert, who taught them to “duck and cover” in the case of an atomic attack.

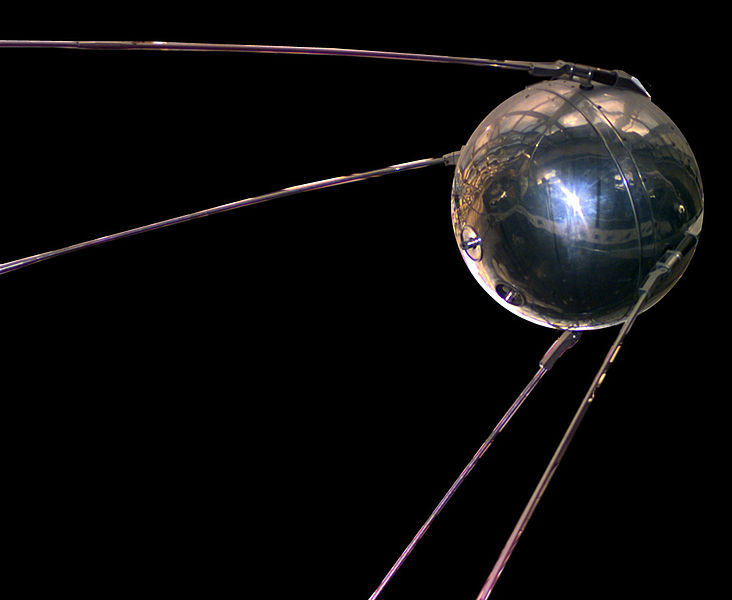

Paranoia went up a notch when Soviets got the early lead in the Space Race. Sputnik I was just an 184-pound ball, but Sputnik II sent a stray dog named Laika into space, and it required putting a six-ton rocket into orbit to launch the satellites. It was the strength of Soviet rockets/missiles that threatened the U.S., not dogs in space in big steel beach balls. Ike wasn’t privately concerned with Sputnik and actually appreciated the fact that it established a free fly-zone precedent in space that could even apply to the U-2 flyovers.

At the time of Sputnik’s orbit, the U.S. was further along than Eisenhower let on in its pursuit of “artificial moons” (satellites), but the Vanguard TV3 rocket failed a televised launch in December 1957 that the press dubbed “kaputnik” (previous chapter). The government turned to Wernher von Braun, whose team launched the Explorer I satellite in January 1958. Ike wanted to take the projects out of the military’s hands and give them some semblance of true, scientific importance and, after WWII (privately, even before), Von Braun was more interested in pure space exploration than weaponry. Ike capitalized on Sputnik and Soviet development of an ICBM (long-range) missile to create NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Whereas today NASA has branched out into climatology, geology, asteroid defense, and planetary explorations, the early Space Race was mainly just a public relations spin on the high-tech arms race.

At the time of Sputnik’s orbit, the U.S. was further along than Eisenhower let on in its pursuit of “artificial moons” (satellites), but the Vanguard TV3 rocket failed a televised launch in December 1957 that the press dubbed “kaputnik” (previous chapter). The government turned to Wernher von Braun, whose team launched the Explorer I satellite in January 1958. Ike wanted to take the projects out of the military’s hands and give them some semblance of true, scientific importance and, after WWII (privately, even before), Von Braun was more interested in pure space exploration than weaponry. Ike capitalized on Sputnik and Soviet development of an ICBM (long-range) missile to create NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Whereas today NASA has branched out into climatology, geology, asteroid defense, and planetary explorations, the early Space Race was mainly just a public relations spin on the high-tech arms race.

Despite their fallout shelters, taxpayers were more enthusiastic to contribute dollars for space than defense, even if the same rockets that carried astronaut capsules on their tips could be refitted to carry nuclear warheads. NASA funneled billions in public money to aerospace companies like Chrysler Aviation, who built Von Braun’s Redstone Rockets, named for the arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama where they were developed. Redstones were the key link between NASA’s rockets and long-range ballistic missiles, followed by the Atlas and Titan series. The Air Force and NASA quickly realized that they couldn’t control these powerful rockets without quantum leaps forward in computing for their navigation systems. Computer science, the application of logic to electric currents, had come a long way since John Vincent Atanasoff invented the first electronic digital version at Iowa State College in the 1930s, but they were too big for use on weapons or transport. Integrated circuits and microprocessors changed that.

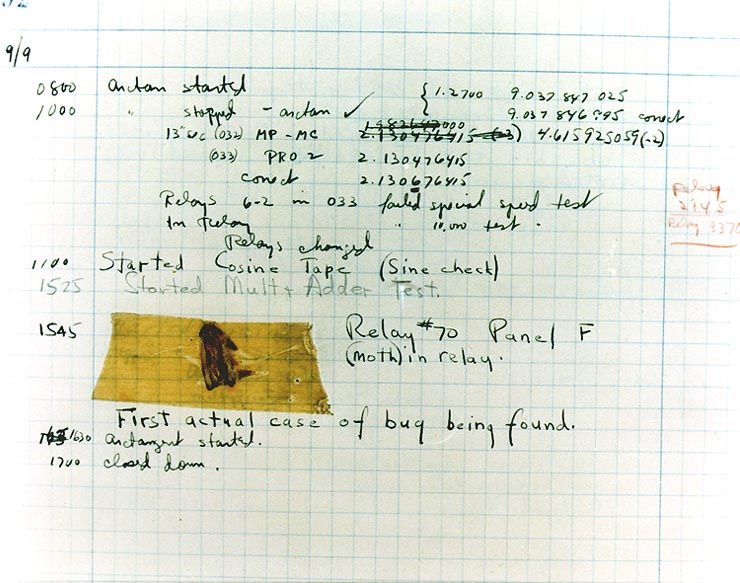

The Term “Computer Bug” Comes From An Actual Moth Shorting The Relay Of A Harvard Mark II Computer In 1947, Naval Surface Warfare Center Computer Museum

It’s a commonly held notion today that only free markets spur growth and innovation while governments just drag down the economy. It’s surprising how many people nod their heads in approval at this balderdash despite the obvious contradictions of recent history. Military spending during the Cold War was an example of how government-funded research and cooperation with private contractors, venture capitalists, and universities spurred the economy. Boeing’s contracts for the Minuteman Missile paid, in turn, for Fairchild Semiconductor’s research on silicon transistors. Under Ike’s successor, John Kennedy, NASA funded Fairchild’s work on integrated circuits, or microchips, because they needed computers smaller than a barn if they were going to send them on rockets to the Moon, or Moscow. Silicon integrated circuits were smaller, cheaper, and faster than the hand-assembled transistor circuit boards of the 1950s. Today chips don’t run just computer systems and phones, they run cars, planes, satellites, medical devices, weapons, robots, etc. Government-subsidized chip foundries and Fairchild spawned dozens of “Fairchildren” in Silicon Valley (Santa Clara Valley and San Jose, California) — home today to Apple, Alphabet (Google), Nvidia, Hewlett-Packard, Cisco, eBay, Adobe, Yahoo, Meta (Facebook/Instagram), Netflix, LinkedIn, etc.

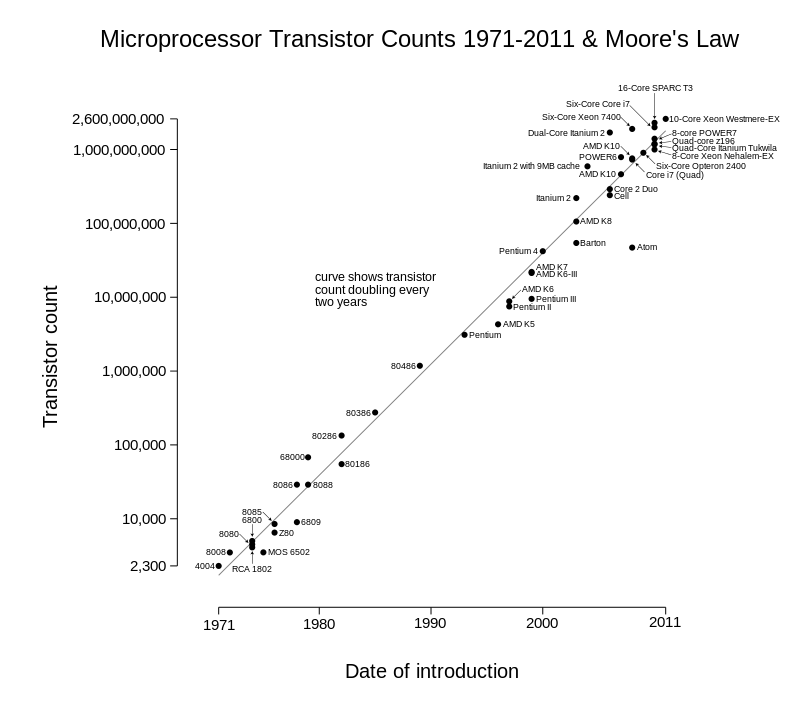

Early pioneers included Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments, who developed an integrated germanium (Ge) chip shortly before Robert Noyce’s superior silicon (Si) version. Science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov called Kilby’s idea of using the same material to integrate a smaller transistor chip instead of using component parts “the most important moment since man emerged as a life form,” though he wasn’t around to see today’s machine learning model transformers crucial for generative artificial intelligence. Noyce, the “mayor of Silicon Valley,” was the link between Fairchild and its direct descendant, Intel, whose engineers developed single-chip microprocessors (e.g., 4004) that truly kicked off the digital age. Intel co-founder Gordon Moore predicted the number of transistors that could be placed on a single (dense) integrated circuit would double every year. Today, the updated Moore’s Law predicts that every 18 months computers will either double in power for the same cost or halve in cost for the same power, though heat dissipation problems might finally bend Moore’s curve. (If you’d like to see your STEM friends argue, ask them to debate whether Moore’s law is still in play.) Soon the giga– and tera– prefixes before byte will give way to peta– and exa-. Intel epitomized the creative, hard-working, egalitarian culture that contrasted Silicon Valley with stuffier, old-school companies. They encouraged employees to innovate and bounce ideas off management, regardless of their place in the chain-of-command.

Intel, Texas Instruments, and IBM laid the groundwork that made early personal computers like the Apple II (1977) and IBM 5150 (1981) possible. IBM was an older firm that profited from government contracts during the arms race. They built navigation systems for the Atlas and Titan missiles and reinvested those profits on the 360 Series (1964), the first mainframe computers to incorporate integrated circuitry. After public funding seeded the information technology plant, private venture capital took over from there, targeting a market far bigger than any government: us. The key to mainstream personal computers and smartphones was the graphical user interface (GUI) that Apple and Microsoft heisted from Xerox PARC to make their operating systems more user-friendly.

Defense spending stayed around 10-12% of GDP in the 1950s-60’s, compared to 3-4% today (16% of federal budget). NASA spin-off technologies led to advances in health and medicine, firefighting, water purification, food safety, solar cells/panels, pollution remediation, freeze-dried food for military personnel, and consumer products (e.g., Velcro®, WD-40® and Tang®, though astronaut Buzz Aldrin complained that the fruit-flavored drink “sucked”). Government-funded research like DARPA (then ARPA) led to much of the technology that surrounds us. Satellites, for instance, made cell phones (and their apps), advanced weather forecasting, and global-positioning systems (GPS) possible, while revolutionizing television, media coverage, and warfare. Other DARPA technology included ultraviolet filtering lenses, high-resolution optical scanners, remote medical diagnostics, improved battery-operated tools, memory foam, and quartz watches. Composite materials, lightweight computer equipment, long-range data links, digital flight controls, and artificial intelligence, in conjunction with GPS, enabled drones (UAVs). Currently, the U.S. Air Force trains more remote pilots than fighter and bomber pilots combined. Moreover, research into ocean floors on behalf of nuclear submarines led to the plate tectonic theory that underpins modern geology and our understanding of other planets. Since 2004, DARPA has sponsored driverless car races. In the first, no car went further than eight miles on a 45-mile track.

DARPA’s most conspicuous contribution was ARPANET (1969), the precursor to the Internet, created along with NORAD’s SAGE so that radar and missile sites could communicate with each other in case of a first-strike nuclear attack by the Soviets. Even the computers the Internet ran on were the product of government research during WWII and the Cold War, and Air Force funding at Stanford created the first search engine in 1963, thirty-five years before Google. For twenty years, the Internet was mainly the domain of government, military, and academics at research centers like MIT, with small networks around Boston and Los Angeles. UCLA’s first message, LOGIN, only registered LO before crashing Stanford’s server. But the invention of the World Wide Web (or “Web”) by Briton Tim Berners-Lee in 1989 allowed for a broader system of linked hypertext documents with domain names, and most Americans were online by 2000, triggering a revolution so profound that historians liken it to the widespread adoption of printing and paper during the Renaissance.

This ARPANET Map is from 1972. Before the Internet sent its first TCP/IP packet January 1st, 1983, the original WAN was the ARPANET. Run by the military, it connected researchers at military bases and a select few universities with military sponsorships, connected by dedicated 56K phone lines. The net could not grow beyond 256 hosts. 8-bit addresses allowed 64 nodes (locations) and 4 hosts (servers) per node. Clients were dumb terminals connected directly to hosts with serial cables or dial-up modems.

Government-funded innovation continues today. R&D Magazine ranks the top hundred inventions each year. In 2011, 77 of those were at least partly funded by the federal government. Lost amidst the Solyndra controversy in 2012 was the fact that 98% of the renewable energy ventures supported by Obama’s 2009-19 Stimulus were still in business. Most of them got funding before Obama arrived as part of George W. Bush’s 2005 Energy Policy Act. In a 2015 Atlantic interview, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates said, “Yes the government will be somewhat inept — but the private sector is, in general, inept. How many companies do venture capitalists invest in that go poorly?” As even the Wall Street Journal noted, former Clinton Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers was obviously mistaken when he called the government a “crappy venture capitalist.” A fairer criticism from the right would be that the government has unfair advantages as a venture capitalist — namely our taxes — which no doubt accounts for its disproportionate success.

It may or may not be disturbing that the Cold War arms race spurred the postwar economic boom, depending on your perspective, and a small-government advocate could argue that a free market would’ve produced even better technology on its own. Either way, it’s nonsense to argue that taxpayer-funded government spending can’t produce results when the military-industrial complex shaped our modern economy. We exist in the shadow of Cold War military spending. The government also spurred growth by subsidizing college tuitions, especially via the GI Bill. While none of us enjoy paying taxes and free markets definitely produce innovation on their own (e.g., Edison’s), be wary of broad, simplified generalizations about the relationship between the government and economy. Atlantic writer James Fallows pointed out that, if you fly over America in a small plane and look below, you’ll see the government’s imprint everywhere: land divided up per the Land Ordinance of 1785, roads, dams and bridges, railroads, public schools and universities, and WPA projects; then you’ll land at a small airport built during the Cold War. It’s within this framework — not in a vacuum — that American private enterprise has thrived. If you don’t think the public/private model holds any value at all, try going a day without your smartphone. Half of us couldn’t go five minutes, let alone one day. While you’re at it, don’t drive on the freeway or use water from municipal systems.

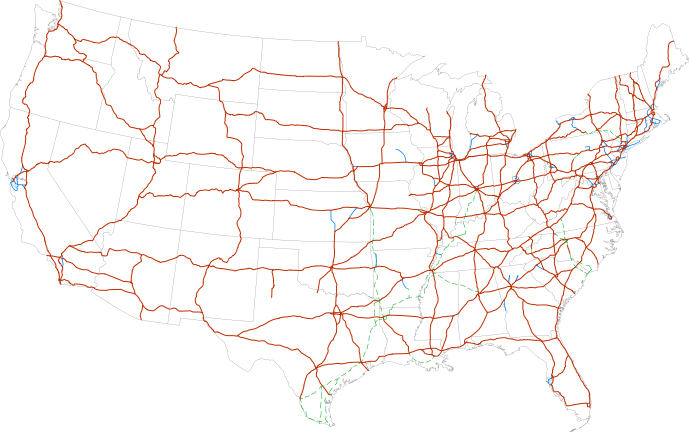

Infrastructure Eisenhower also spurred economic growth by promoting and signing the gas tax-financed Interstate Highway Act of 1956 that built on earlier state legislation dating back to the 1920s and Pennsylvania and New Jersey’s pioneering four-lane turnpikes. As part of the New Deal, Roosevelt pushed through the Pennsylvania Turnpike just in time for the 1940 election (he won that state) and its banked turns, lack of stop signs, and low grades and big cuts through the Allegheny Mountains influenced the engineering of the national plan in the 1950s, though the latter’s financing didn’t rely on tolls. But after Pearl Harbor, FDR allocated resources and the best road-builders toward the Alaskan Highway to defend that territory and the interstate idea went on the back burner.

Eisenhower also spurred economic growth by promoting and signing the gas tax-financed Interstate Highway Act of 1956 that built on earlier state legislation dating back to the 1920s and Pennsylvania and New Jersey’s pioneering four-lane turnpikes. As part of the New Deal, Roosevelt pushed through the Pennsylvania Turnpike just in time for the 1940 election (he won that state) and its banked turns, lack of stop signs, and low grades and big cuts through the Allegheny Mountains influenced the engineering of the national plan in the 1950s, though the latter’s financing didn’t rely on tolls. But after Pearl Harbor, FDR allocated resources and the best road-builders toward the Alaskan Highway to defend that territory and the interstate idea went on the back burner.

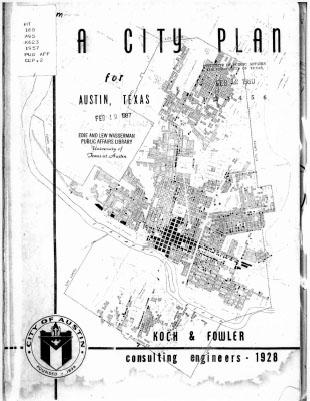

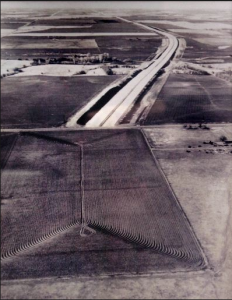

As a former general, Ike had military efficiency in mind primarily, envisioning a four-lane system similar to the German Autobahn he’d seen during WWII that armed convoys could move around on, with the updated version having high enough overpasses (17 ft.) that nuclear warheads could pass underneath. Ike also figured that freeways would allow cities to evacuate and rebuild faster in the event of a nuclear strike. As vile as the Nazis were, Eisenhower preferred their roads to those he’d seen on the Army’s torturous 62-day convoy across America in 1919. Prior to the mid-1950s, some states had modern roads, but the overall network was mostly an inconsistent patchwork of mud, gravel, and two-lane county roads. Kansas had a new four-lane turnpike that just stopped at the Oklahoma border. Arkansas’ I-49 stopped at the Texas border (right). Even motorists and truckers whose path wasn’t blocked by a field had to stop at every light in every town their highway bisected and couldn’t pass each other safely in between. To get a feel for what driving across the country was like before the 1960s, take U.S. 79 from Round Rock, TX to Shreveport, LA. Interstates had the potential to further unite the United States.

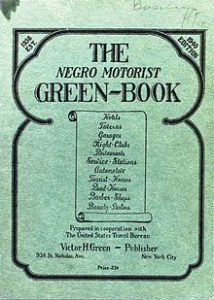

Interstates were the biggest federal project in U.S. history — bigger than any New Deal stimulus, the Manhattan Project, or the Moon landing — and made transportation and trucking more efficient. The concrete ribbons running horizontally across the country end in zero, running from I-10 across the Southeast to I-90 across the north, while the vertical roads end in 5, from I-5 in the west to I-95 in the east (many of the earlier state highways used similar numbering). The interstates match or exceed what Classical Romans built in efficiency and scale and were indispensable to the growth of Sunbelt cities like Dallas, Houston, and Phoenix. The two-lane trans-continental highways they displaced (e.g., Route 66 and Lincoln Highway) make for good memories with their kitschy diners and motels now that people don’t have to rely on them, and it’s interesting that many of those roads were built on old Indian trails that were in turn built on old animal trails toward salt licks. But kitsch doesn’t equal practicality. The same motels and restaurants we look back on nostalgically today were flush up against the right of way, making expansion to four lanes impossible. The two-lane cross-country routes could also be a nightmare for Blacks and Hispanics with few places to eat or sleep and they were more likely to accidentally drive into segregated sundown counties or towns at their peril. Special road guides (right) provided a sort of 20th-century underground railroad of minority-owned businesses and Whites progressive enough to serve minorities food out of a separate drive-through window instead of denying them service altogether. Esso, a subsidiary of Standard (now ExxonMobil), sold gas to minorities and allowed them to franchise stations.

Better freeways dovetailed with one of postwar America’s most underrated inventions: the intermodal container. Frustrated with watching longshoremen time-consumingly offload supplies from separate crates into his trailers via the traditional break-bulk method, North Carolina trucker Malcolm McLean (left) designed a standardized container that could fit on ships, trains, and semi-trucks alike, using straddle carriers in between. Today, virtually all shipping other than dry-bulk commodities uses intermodal containers, of which there are ~ 20 million worldwide. Their Achilles’ heel is that the same efficiency that makes them good for shipping also makes them handy for smuggling contraband, people or (potentially) bombs. They also put tens of thousands of longshoremen out of work, but that’s a price of almost all progress and automation.

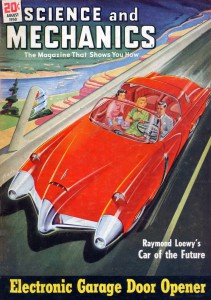

Car, truck, oil, and tire companies were pushing city and state multi-lane freeways long before Ike saw the Autobahn or the national government built the interstates. These industries bought electric streetcar lines from municipalities and destroyed them while road-builders lobbied for contracts. Similar scenarios played out in Latin America, where trains fell out of favor in oil-rich areas. In the infamous L.A. Streetcar Conspiracy, the Pacific Electric Railway sold its tracks and subway system to a shell company that was really a consortium of General Motors (GM), Standard Oil, Philips Petroleum, Firestone Tires, and Mack Trucks. The same group did likewise in Baltimore, Newark, Oakland, and several smaller cities, replacing streetcars with GM buses which they hoped, in turn, would mostly give way to cars. Angelinos later regretted the move when the freeways filled up with congestion and exhaust caused daily smog to settle between the mountains and ocean; and today L.A. is uncovering their old streetcar tracks where they can and rebuilding urban rail. A court found the consortium guilty of conspiracy in 1949 but, by then, the transition was well underway and the public that could afford them preferred cars anyway. In 1955, GM bought and sealed off the “Ghost Terminal” central subway depot. On a lighter note, the Streetcar Conspiracy formed the plot of the classic animation Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1989).

Car, truck, oil, and tire companies were pushing city and state multi-lane freeways long before Ike saw the Autobahn or the national government built the interstates. These industries bought electric streetcar lines from municipalities and destroyed them while road-builders lobbied for contracts. Similar scenarios played out in Latin America, where trains fell out of favor in oil-rich areas. In the infamous L.A. Streetcar Conspiracy, the Pacific Electric Railway sold its tracks and subway system to a shell company that was really a consortium of General Motors (GM), Standard Oil, Philips Petroleum, Firestone Tires, and Mack Trucks. The same group did likewise in Baltimore, Newark, Oakland, and several smaller cities, replacing streetcars with GM buses which they hoped, in turn, would mostly give way to cars. Angelinos later regretted the move when the freeways filled up with congestion and exhaust caused daily smog to settle between the mountains and ocean; and today L.A. is uncovering their old streetcar tracks where they can and rebuilding urban rail. A court found the consortium guilty of conspiracy in 1949 but, by then, the transition was well underway and the public that could afford them preferred cars anyway. In 1955, GM bought and sealed off the “Ghost Terminal” central subway depot. On a lighter note, the Streetcar Conspiracy formed the plot of the classic animation Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1989).

This is a good time to pause and consider that, as counter-intuitive as it may seem to those suffering from progressophobia, some things have improved historically. Not only have we outlawed segregated gas stations, motels and restaurants, we’ve also made driving safer. Because of better highways, seatbelts, anti-drunk driving campaigns, traffic laws, and safer cars, the fatality rate on America’s roads is an astounding 40x lower than a century ago, at 1.1 deaths per million miles driven, though still higher than other countries. But vehicular death rates, especially if defined to include pedestrians and bikers, have been rising since 2011 (AP).

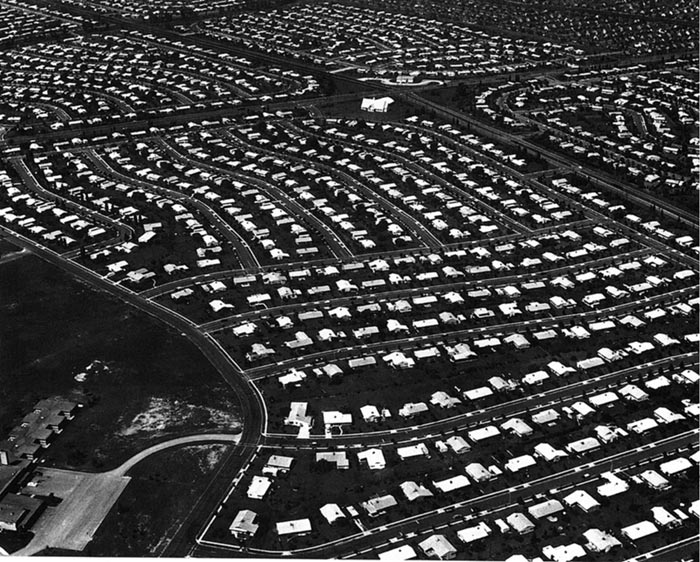

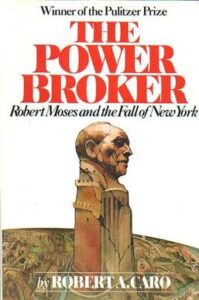

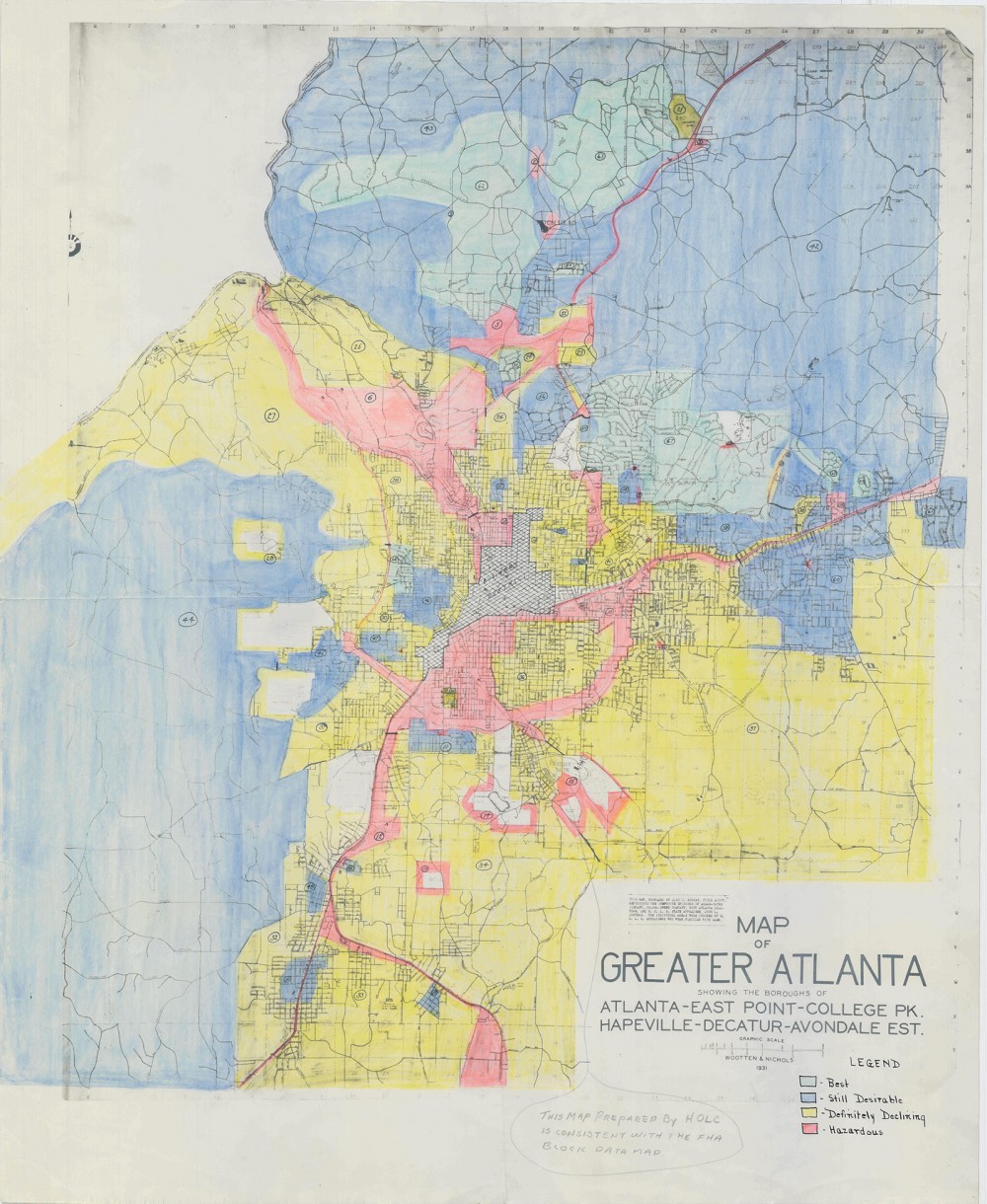

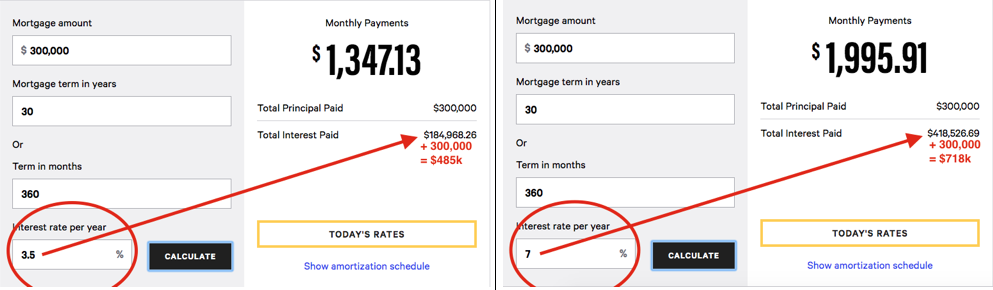

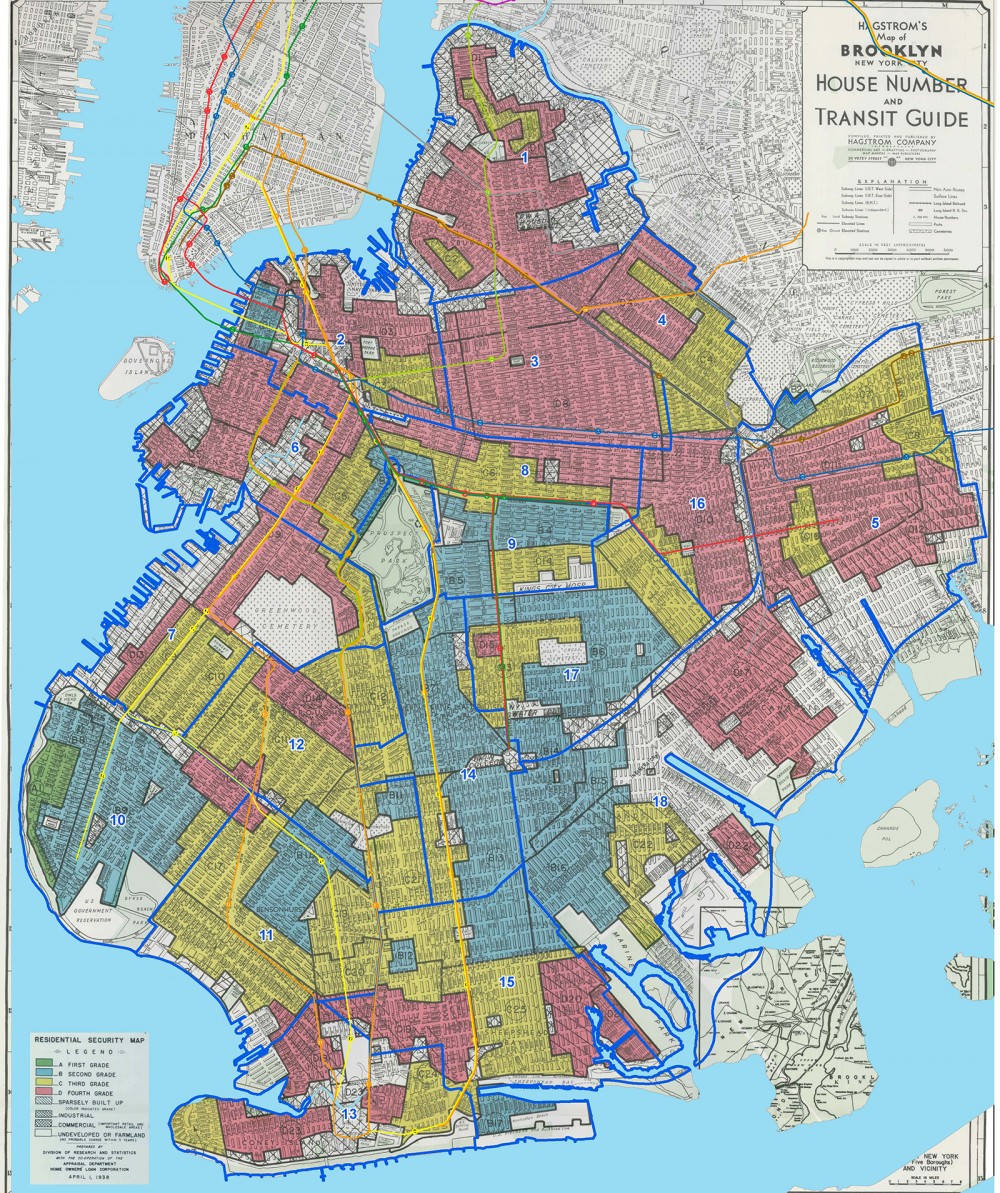

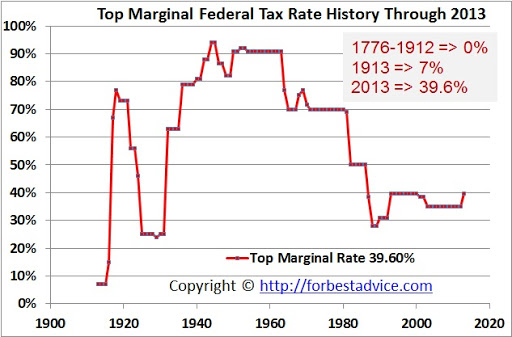

This is also a good time to pause and emphasize a broader point that history is not just about big events, wars, and politicians, etc. Virtually everything about where and how we live, including building our lives around cars rather than mass transit, is part of a historical legacy. Understanding that legacy helps citizens think about what they want and why they want it. Very little just happens naturally or organically in a vacuum. National and local leaders make decisions and those decisions shape society, including, for instance, Houston’s case when leaders chose to let the city grow with less hands-on zoning than normal. The earlier decision to build the Houston Ship Canal rather than use Galveston as the main port was political, too. Historian Michael Marino argues that modern America’s “very existence is predicated on the widespread availability of cheap gas” and gas was cheaper adjusted for inflation after WWII (~ $1.60/gallon) than it is today. As we saw beginning in the 1920s, America’s embrace of cars dictated how the country grew. Suburbs were orientated around car commuters rather than buses or subways, and retail catered to cars with drive-in movies, drive-through fast food and cleaners, and shopping malls at the intersections of major highways.