On August 31, 1989, ACC officially closed Ridgeview, the former L. C. Anderson High School and the school’s first full-time campus. In 1986, the ACC Board of Trustees had voted to pull out of the facility, which ACC had been leasing from the Austin Independent School District, because of structural problems deemed too expensive to correct and because of the abduction and murder of a female student whose body was discovered in the mostly abandoned and crime-infested Booker T. Washington housing project across the street from the campus. But actually shutting Ridgeview down, just as the College was realizing its new financial security and opening brand new teaching and learning facilities in north and southeast Austin, hit many east-Austinites hard. They rejected arguments that the new campuses would more than make up for their neighborhood’s loss by providing up-to-date educational opportunities.

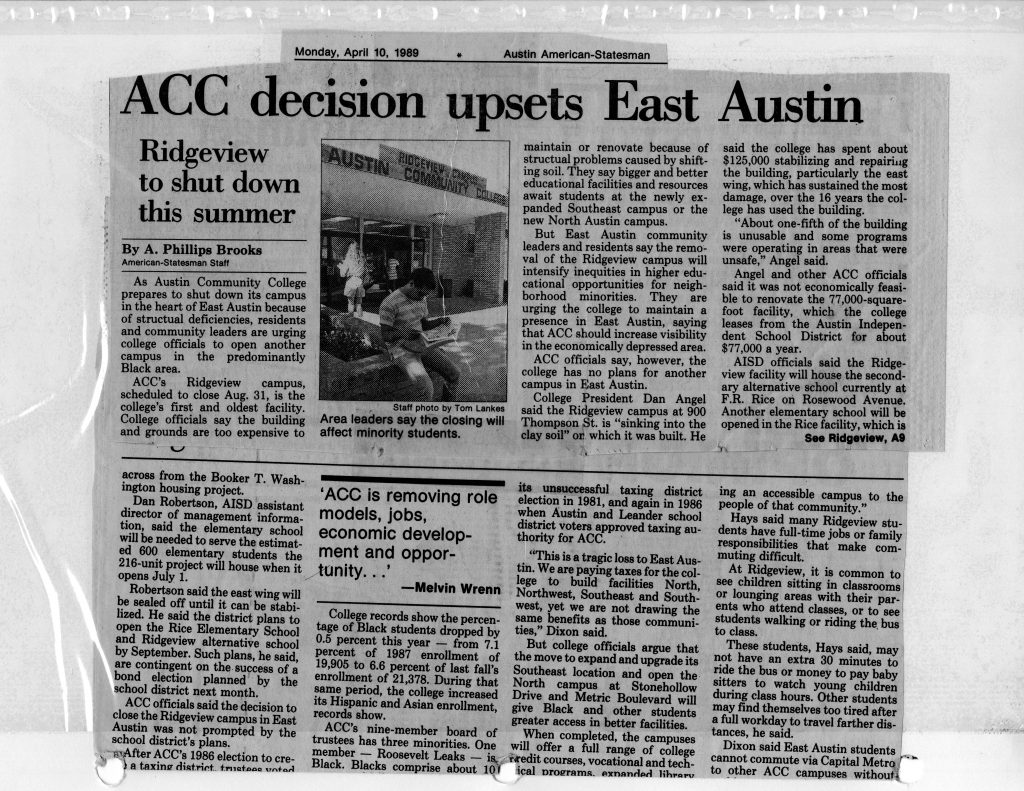

Angry voices from the East Austin community rose in a chorus of condemnation of Ridgeview’s closing, and ACC officials’ rationale for the move only elevated oponents’ temperature. What precipitated the move, ACC President Dan Angel explained, was with the site more than the adequacy of the building. Engineers reported that shifting soil was causing structural damage to the building. Ridgeview, Angel said, was actually “sinking into the soil.” ACC had already spent $125,000 trying to shore up the facility, but spending more money, with no great likelihood that the situation was fixable, just didn’t make sense. Then Angel pointed to the new Riverside campus and declared that East Austin was gaining a “first-rate, beautiful facility.”

Many black East Austinites rejected the College’s rationale for the move, especially the implication that Riverside was in their neighborhood. State representative Wilhelmina Delco pointed out that Riverside was actually in the heavily Hispanic area south of the Colorado River, which was “nowhere near the same as having a campus in East Austin.” Furthermore, even with Ridgeview, ACC under-served East Austin. The percentage of black students had recently declined, and only 7.3 percent of Ridgeview’s 4,100 students were black. Moreover, only one of the nine members of ACC’s Board of Trustees was black. Closing Ridgeview confirmed ACC’s lack of commitment to East Austin and its tax-paying citizens. Melvin Wren, head of the local National Business League, worried that the loss of 300 Ridgeview jobs would dampen the neighborhood’s economy. “The long-term effect will be devastating.” And Rev. Freddie Dixon, pastor of Wesley United Methodist Church, complained about ACC’s ingratitude after he and other East Austin residents had campaigned in 1986 on behalf of ACC’s successful tax and bond referendum. History instructor Roland Hayes pointed out that distances and the lack of direct bus lines between ACC campuses made access difficult and even impossible to many East Austin residents with.

Most of those who spoke out against closing Ridgeview added that they hoped that ACC would soon build another facility in their neighborhood.