ACC’s new president, Dr. Roberto Aguero, was a shy but persistent 53-year-old third generation Tejano who grew up in Camp Wood, Texas, a small town deep in the southwest Hill Country. One day in the autumn of 1967, he sat at his desk in the 11-th grade English classroom at Nueces Canyon High School reading The Voice of Bugle Ann, a slim and dramatic children’s novel that was made into a popular motion picture in the mid-1930s. His teacher took it away, telling him he was wasting his time on children’s literature. She urged him instead to read Leon Uris’ formidable novel Exodus. He did and learned about Jews’ flight from persecution in Egypt during Biblical times, the Holocaust at the hands of the Nazis during World War II, and the formation of modern Israel mid-way through the Twentieth Century. This was young Aguero’s introduction to cultures other than his own and put him on track for personal discovery and enlightenment. As a young man, Aguero encountered the community college movement. After high school, he enrolled in Southwest Texas Junior College in nearby Uvalde. Aguero’s path from there led toward a rewarding career in educational leadership. Following high school, he earned bachelor’s degrees in English and science from Angelo State University, a master’s degree in education from Stephen F. Austin State University, and a doctorate in curriculum and instruction from Penn State University. At that point, Aguero doubled-down on his dream of leading a community college in his home state.

He soon began living the dream. Dallas County Community-College District hired him to lead its Eastfield College. From there he quickly reached the position of vice chancellor for educational affairs and faced the same kinds of existential issues that most other leaders of the community college movement encountered. The immediate challenge was to find ways to educate and train legions of new students in Central Texas, including those who, in previous years, would have been regarded as “not college material” either because they could not perform college-level work or could not afford to try.

For a long time, ivy-covered walls had symbolized the elite world of higher education, separated and rising primary and secondary public education. Industry and college leaders together now began to look at higher education very differently, imagining and talking excitedly about “open doors” to higher education for all who wanted it rather than walls and tests to serve the interests of elites who felt entitled to it. Nor was higher ed entirely, or even mostly, academic. Leaders in ACC’s new biotech programs became the new “buzz” around Austin. During the 1990s, biotech imagery featured “pipelines,” seamless conduits that channeled endless streams of students from primary to secondary classrooms and through two-year community colleges and four-year universities through pipelines to high-paying work-places for manufacturing computer components and devices and network design and manufacturing facilities. Meanwhile, Early College Start speeded up the pipelines, thereby shortening the time it took most students to complete the requirements for certification in a number of technology-based fields, pleasing employers and students alike. The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board announced a goal of 500,000 new college in four-year schools by 2015.

Meanwhile, however, the “pipelines” began filling up, clogging up the “flow” of students seeking better lives for themselves and their families. The University of Texas at Austin announced it would cap undergraduate enrollments over that number would have to be in undergraduate programs in other four-year schools and in community colleges. The only way to attain that goal was through the state’s community colleges. Failure to meet the Coordinating Board’s goal might well cause high-tech companies to abandon their present situations which could be catastrophic to Central-Texas local economies that depended on high-tech.

Another problem with that plan was that the pipeline was not seamless, and the seams leaked. Many entering first- year students did not possess basic math and literacy skills to enable them to acquire the knowledge offered in colleges and universities, and instead of moving on, large numbers of students. ACC, for one school, was willing to teach basic skills courses, but students had to pay fees to take them and offer developmental courses in math, reading, and writing, but they were not free. And typically, community colleges offered developmental reading and writing courses and made it a requirement for moving into degree-plan courses. Many students became frustrates, disheartened, and ended up dropping out of school.

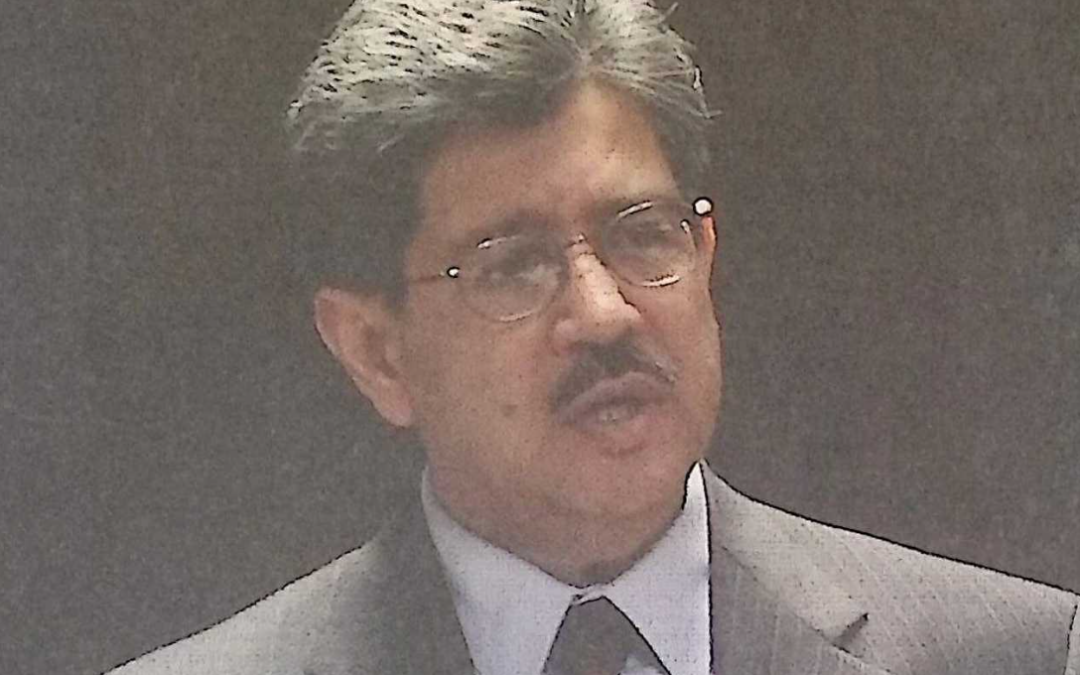

Meanwhile, in Austin, ACC president Richard Fonte submitted his resignation, under the weight of ACC Faculty Senate sanctions, to take a position in Washington, D. C. Aguero’s dream of leading an entire community-college system beckoned him. “I feel like I’ve been preparing for this all my life.” Now, at age 53, he intended to have a positive impact on this community.” The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), the regional accreditation authority had notified ACC that due to battling among members of the Board of Trustees and two votes of “no confidence” in the President, ACC was in danger of losing its accreditation. Furthermore, failure of the human relations office to properly care that faculty credentials were up up-to-date and verified that faculty were qualified to teach the courses that were assigned to them violated SACS standards. The solution to the problem was as galling as the problem itself. All faculty were instructed to update their personnel files to verify that they were indeed qualified to teach the courses assigned to them, and if they could not prove their bona fides, they would not be allowed to continue teaching those courses until or unless they took the courses in question again to prove their qualifications. It was indeed “trifling.” Aguero thus managed to persuade SACS to reinstate ACC to good standing with the BOT.

Meanwhile, President Aguero presided over the opening of ACC’s new South Austin Campus. This too posed frustrating problems and disappointments. First, because South Austin was the venue for many live music performances, planners committed ACC to developing the South Austin Campus as a training ground for students interested in careers in the music industry. In addition to regular classrooms for core college courses, early designs included an outdoor stage and expensive recording studios for live music programs. Funding for the $21 million South Austin Campus would come from the $99 million tax and bond package that voters had approved in the April 2003 tax-bond election and which had been the source of great excitement at that time. But planners did not supply the BOT with accurate cost appraisals, and contractors could not keep up with the unrealistic time and cost estimates. Finally, President Aguero broke the bad news to the Board: the project would not be finished until the fall of 2006. Aguero told Board members: “It was unrealistic to believe that many programs could be included at that price.”