“And what do we mean by the Revolution? The War? That was only an effect and consequence of it. The Revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington.” — John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, 1815

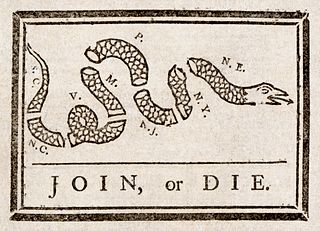

The history of the American Revolution really begins with the French & Indian War (1754-63), without which no rebellion would have taken place when it did. We read about the French & Indian War at the end of Chapter 3 as part of a bigger global conflict between the British and French called the Seven Year’s War that raged across the West Indies/South America, India, Africa, and Asia (the Philippines). The British took over India and North America at the end of the war, ruling the region north of Florida and west to the Mississippi River. Take a look at the map above. Colonists wouldn’t have broken from Britain if they still needed their protection from the French (green), who’d blocked western expansion in the Ohio Valley. Americans and Redcoats fought together against the French but, as the saying goes, familiarity breeds contempt, and colonial militias resented the contempt of their superiors in the British military. Some colonists didn’t think that they needed the British anymore and the population inhabiting these growing, resource-rich colonies was virtually self-selected for rebellion against authority, many of its settlers having emigrated from the British Isles to seek greater freedom. They bristled under British attempts to keep them near the East Coast and quarreled over financial issues regarding taxes and trade. By 1763, it was time to dust off the “Join, or Die” woodcut Ben Franklin had printed in 1754 to rally colonists on behalf of the British against the French; but, this time, they were rallying against their own rulers. Franklin’s idea of unifying the colonies had fallen on deaf ears earlier, but revived twenty years later with formation of the Continental Congress in 1774.

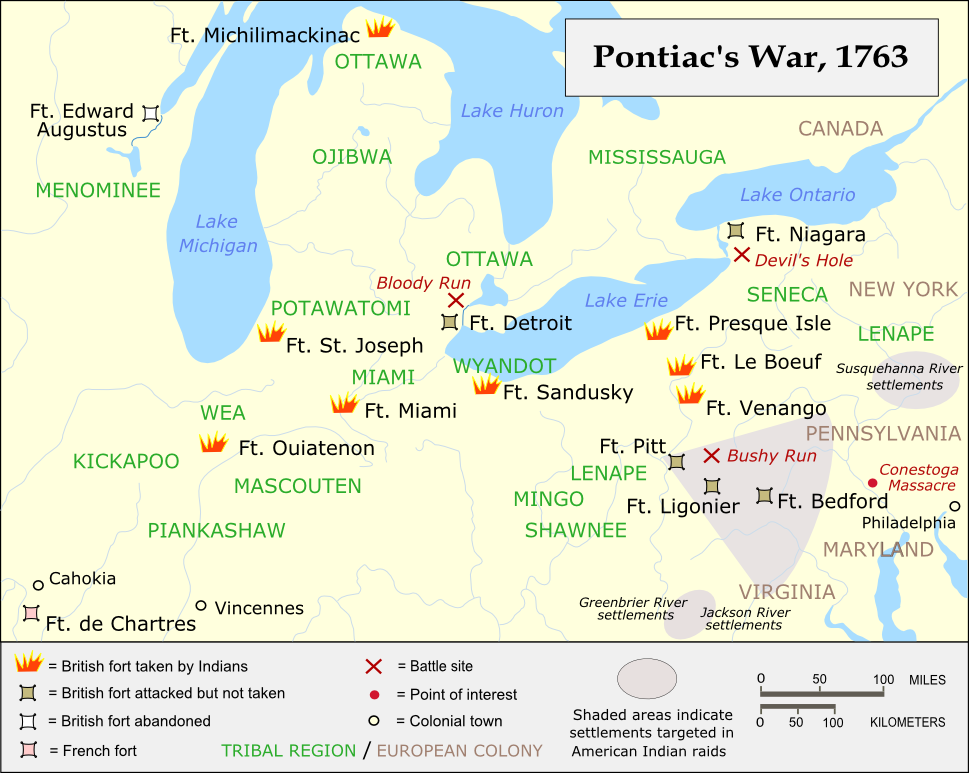

After the French & Indian War, the British tried and failed to defuse Indian conflict along the frontier by drawing a Proclamation Line down the spine of the Appalachian Range (red line in the map above), barring settlement west of that boundary. The British were overextended financially and geographically after their win over France and they wanted to push more settlers along a north-south axis to Anglicize French Canada (make it more English) and establish a claim to Spanish Florida. The idea was also to protect settlers from Indian attacks as the line would constitute a border between them. But the border wasn’t effective in keeping settlers like Daniel Boone from going west and stirred resentment among those who suspected that the British were trying to hem them in so as to better control and tax them. Fighting Native Americans along this frontier during Pontiac’s War of 1763 galvanized settlers even more, forging unity they later employed against the British. British American settlers, unlike their rulers, wanted to expand west and conquer Native Americans, as we saw with Bacon’s Rebellion in Chapter 5.

For Indigenous Americans in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley, it’s no coincidence that they tried to unite at this point, primarily under the Ottawa leader Pontiac. As we saw in Chapter 3, tribes in the French Pays d’en Haut (“upper country”) triangulated their relationship with Europeans by playing French and British off each other — shifting alliances based on diplomatic and trade terms. Neither British nor French could afford to sever their alliance with all Native Americans out of fear that they would join the other side and gang up on them. After 1763, the French were gone and it was basically expansion-minded Whites against Indians, now a commonly used term among British Americans instead of individual tribal names like Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, Iroquois, Cherokee, etc. Pontiac followed the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) prophet Neolin, who discouraged dependence on white trade goods, especially alcohol, and advised other tribes to “take up the hatchet and drive the dogs clothed in red [British] off the lands.” Indians began to see themselves increasingly as one group but struggled to unify. Linguistic barriers and traditional rivalries made it difficult for tribes to communicate and cooperate with each other. Pontiac’s uprising was a brutal conflict that included treacheries on both sides and civilian casualties. Ben Franklin nearly triggered a revolt in Pennsylvania when he criticized the vigilante Paxton Boys who murdered 20 innocent (Iroquoian) Susquehannocks in the Conestoga Massacre, calling them barbarians who’d “brought eternal disgrace to their race and religion.” In response, the Paxton Boys marched on Philadelphia to vent their anger, but Franklin raised a militia and talked them down, promising to hear their grievances. Indian affairs were then the subtext of another conflict between settlers and British authorities in the same area a year later, the Black Boys Rebellion. Pennsylvania colony was split among Quakers who lived peacefully with Native Americans and more recent Scots-Irish and German settlers along its western frontier who advocated more aggression. Pontiac’s War mostly bound the colonists together in a shared traumatic experience, helping to lay the foundation for future cooperation against the British and galvanizing them against Indigenous Americans.

Geographic expansion and Indian conflict, then, complicated Britain’s relationship with their American colonists. Also, some masters feared Britain’s potential power to abolish slavery. Yet, as is often the case in human conflict, be it marital, commercial, political, or military, money was also an important root of the problem. The British tried to crack down on smuggling, regulate currency, and collect import taxes, enforcing the Navigation Acts they’d passed in mid-century to enforce their mercantilist monopoly on American trade. They were trying to steer more trade toward England and away from France and the Netherlands because that was the whole point of colonizing; otherwise the “mother country” is paying to run the place while others reap the profit. American merchants protested against British officials being able to search their homes and warehouses for contraband. One of their lawyers in Boston, James Otis, Jr., wrote, “Taxation without representation was tyranny.” They’d been arguing the same since at least as far back as 1750.

Taxes were a key aggravation since the British had borrowed so much money to win the French & Indian War. They spent over 50% of their annual budget financing interest on their debt, compared to modern Americans who pay ~ 7%. Parliament argued that the war was fought for the colonists’ benefit, so it was time they started to pay their fair share. Taxes are hard to measure because they varied among the colonies and were levied in a variety of forms, including tobacco, fur, rum, and coins. But most historians agree that American colonists paid only ~ 10% of the average English citizen. Ohio State’s Ben Baack put the colonial average ~ 2-4% of English taxpayers. Colonists argued that the French war was not for their benefit but rather for Britain’s own — that was the price of empire — and, regardless, they should not have to pay any taxes if they had no representation in the Parliament that taxed them.

Rebellion Fit For An Englishman

Let’s step back to get some perspective on the colonists’ complaint. First, they paid mainly only import taxes to the home country while benefiting from living under the protection of the world’s biggest navy and enjoying significant political freedom and self-government within the colonies. Propertied white males could vote at least in the lower houses of all the assemblies, though some colonies had royally appointed governors. Roughly 20% of white colonial Americans (~ 40% of pale males) could vote in local elections, but none in Parliament. Eighteenth-century British Americans had similar status to today’s residents of Insular Territories — Guam, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, Northern Marianas, etc. — who (other than Samoans) are U.S. citizens, can vote in local but not national elections, serve in the military, and pay payroll but not income taxes. Their representatives in Congress can serve on committees and even sponsor legislation, but not cast final votes. Washington, D.C. residents also pay federal income taxes with no congressional representation. This wasn’t Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia the colonists were living in. If you think of British colonial rule as too onerous, ask yourself how much sleep you’ve lost over U.S. denial of citizenship to Samoans or political representation to Puerto Ricans. Now imagine if they only paid 1/20th as much as you in taxes while benefiting from Uncle Sam’s military protection.

Second, political representation proportional to British Americans’ small population wouldn’t have helped the colonists much. Parliament could’ve just called their no taxation without representation bluff and given them a small number of seats in the House of Commons. However, that would’ve opened the door for the entire United Kingdom and the American colonies were bound to grow bigger, to say nothing of India, later.

Third, representation of any kind barely existed outside the British Empire in 1763 and complaining about its lack thereof would not have even made sense elsewhere. Unlike absolutist European and Asian monarchies, England had a tradition of rights among its people — a contract between ruler and ruled — that dated back (at least in myth) to Magna Carta of the late Middle Ages through Edward Coke’s Petition of Right, the English Civil War, and Glorious Revolution. In the English Civil War of the 1640s, Puritans beheaded their king and set up the biggest republic the world had seen in 1700 years. The monarchy restored but, after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, it never regained true power from Parliament and ministers (see the 1689 Bill of Rights). Nothing tells us more about a society than its imagination. England’s fantasy medieval monarch, King Arthur, didn’t sit at the head of rectangular table at Camelot; his knight advisers shared with him a round table. Had they been office jockeys, Arthur would’ve had an open cubicle.

American Brits reared in this proto-republican tradition saw themselves as entitled to certain rights as British subjects and had long since grown used to governing their own affairs with little interference from home beyond British attempts to regulate shipping with the Navigation Acts. Moreover, by the mid-18th century, the colonists paid taxes to their locally elected governments, so paying more to the British would’ve added a second layer. And, as colonies, they enjoyed less political autonomy than countries like Australia and Canada do today within the British Commonwealth.

By the 1760s, the long period of relative self-rule and lax enforcement known as the Era of Salutary Neglect was ending. The British wanted the colonies to quit smuggling and start paying their own way to offset the cost of the French & Indian War. There was no real constitutional precedent to reference because the British Constitution was not a written document so much as an evolving political tradition. Later, the U.S. avoided such problems as best they could by writing down their constitution. Parliament argued that all its colonial subjects (like today’s U.S. citizens of D.C. or Puerto Rico) were virtually represented, while colonists argued for no taxation without representation. The American rebellion, in short, wasn’t launched to commence a novel, grand experiment in democracy, but rather to protest what independent-minded colonial Brits saw as backsliding. They knew they’d been lucky to enjoy a significant amount of liberty while still enjoying the privileges and military protection of being in the British Empire, but a significant minority of Americans saw things trending in the wrong direction. An equal number of Americans saw no major problem and maintained their loyalty to England while another third or so didn’t care.

Currency was also controversial. With no gold or silver mines, the colonies usually had an outflow of hard currency, making specie (coins) an impractical solution for legal tender. Most backcountry transactions relied on bartering of commodities (e.g. tobacco, hay, rum, nails, etc.), but foreign merchants demanded gold or silver in port cities. Locally printed colonial money was spotty and unreliable and depreciated when taken overseas. The British standardized colonial money with the Currency Act of 1764, that encouraged the use of (British) pound sterling by regulating colonial money and prohibiting it from use in debt transactions, the basis of most import-export trade. This tightening of the money supply was a major grievance for the next decade, though the British repealed the act in 1774, before the actual revolution. Taxes were even more contentious.

Tax Disputes, Military Occupation & Resistance

The first tax after the French & Indian War, the Sugar Act of 1764, met little resistance because colonists had paid (or cheated on) such external import duties since the Molasses Act of 1733. The 1733 law was enacted to prevent colonists from smuggling molasses from the French Caribbean. However, rum was New England’s primary export (80%) and the British Caribbean couldn’t supply enough molasses to support the Atlantic trade, let alone the colonists’ own rum consumption, which was high by today’s standards. George Washington won an election to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758 by buying off 391 eligible voters in his district with 160 gallons of rum, beer, and cider. The 1764 Sugar Act lowered the earlier molasses tax by 50% in an attempt to limit cheating enough that they could actually collect some duty. The colonists voiced their displeasure at being taxed without representation, but mostly they just kept cheating. (Spoiler alert: later we’ll see colonists throw an even bigger fit when the British lower rather than raise another import tax).

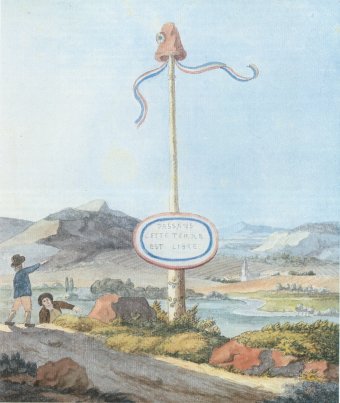

Liberty Pole on the Moselle River (modern Luxembourg) in 1793, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, WikiCommons

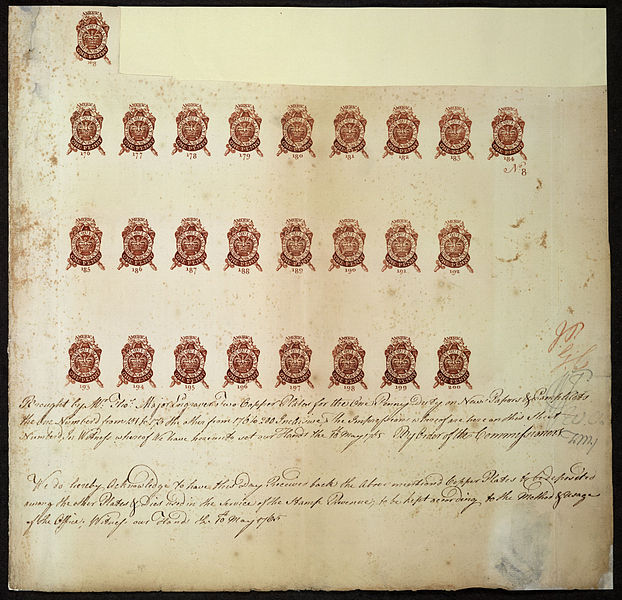

The Stamp Act of 1765, though, was more controversial because it was internal, not just levied at the docks, and there was no way to smuggle around it. It was also unpopular because it was enacted partly to pay for enforcing the already unpopular Proclamation Line along the western frontier. Because of its big backlash, many historians use it to date the beginning of the American Revolution. The Stamp Act created a series of annoying taxes of roughly one penny on legal transactions, including marriage licenses, deeds, wills, contracts, and newspapers and magazines. Even playing cards were supposed to have the royal stamp. It was the first time the British levied an everyday tax within the colonies and it was payable in silver, which was in short supply. The Stamp Act also threatened freedom of the press as it included a provision for cutting off paper supply to “troublesome” newspapers.

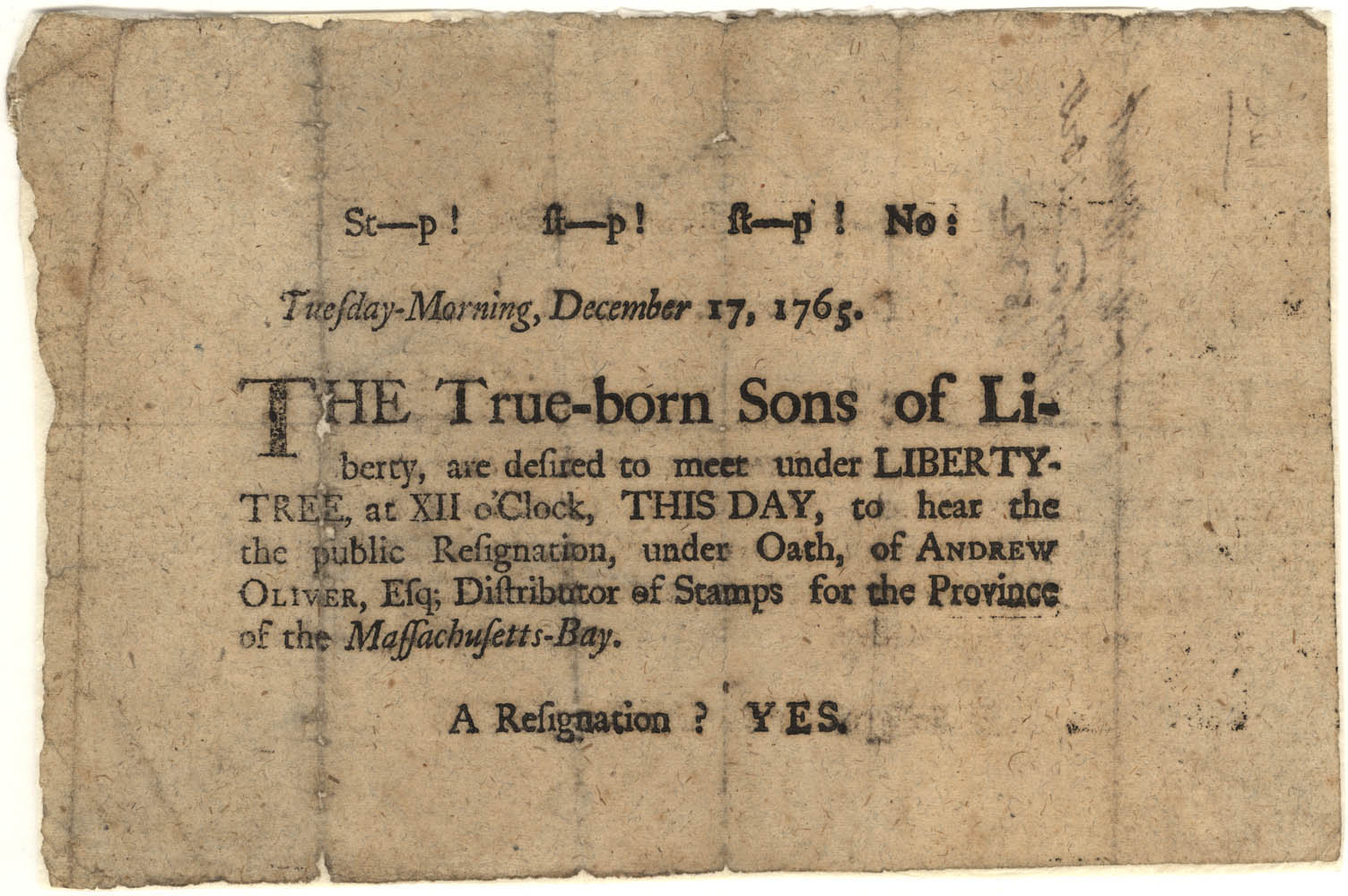

The response was vigorous and rowdy, with tax collectors being tarred and feathered, temporarily buried alive or burned in effigy, and rebels protesting with signs, songs, parades, and the like. Since “liberty was dead,” the rebels held mock funerals for it, carting liberty’s coffin through the streets. A congress met in New York to petition King George III and Parliament. Across the colonies, loosely affiliated groups calling themselves the Sons of Liberty popped up. In New York, they commemorated the repeal of the Stamp Act annually by erecting Liberty Poles, a tradition that dated back to the Roman senate’s assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE. The British kept sawing them down until the Sons of Liberty secured their fourth pole with iron bands and the British blew it up. Liberty Poles and Liberty Trees (Boston) were ubiquitous throughout the colonies and in Europe during the American and French Revolutions. Boston’s Sons of Liberty branch intimidated tax-collector Andrew Oliver into resigning and ransacked the mansion of loyalist Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Some colonists mistakenly thought that Ben Franklin had written the law since, up until then, he generally favored British rule, and had attended King George III’s coronation, and was in London on negotiations at the time. But Franklin actually opposed the tax and, partly to allay these suspicions, drew up this cartoon to protest:

The Stamp Act also had a powerful opponent in the British House of Commons, former Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder, who said: “I rejoice that America has resisted.” When Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, rebels mistakenly concluded that their resistance was the lone cause when, really, there was a change of leadership in England and parliamentarians like Pitt opposed the tax. Anglo-Irish parliamentarian Edmund Burke, most famous for his conservative Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), also sided with colonial Americans in a 1775 House of Commons speech. Burke argued in vain that Britain missed an opportunity to convince colonials, by respecting their distinctly British notions of liberty, that their best chance to preserve those liberties was within the empire. The British might exert more influence in North America, India, and parts of the Caribbean and Southeast Asia even today had they taken that route. It’s impossible to know because that is a counterfactual scenario (Rear Defogger #32).

An unstable monarchy further muddled colonial relations. The young, inexperienced King George III likely suffered from bipolar affective disorder, compounded by pressure and possibly related to a porphyria skin disorder triggered by arsenic in his medicine or makeup. In one episode, he shook hands with an oak branch thinking he’d met the King of Prussia, and he claimed that he couldn’t see himself in mirrors. Related to much of the European royalty that purportedly carried hereditary madness, George sometimes wore a straightjacket at the insistence of his ministers. But, just as we have to remind ourselves that Reformation history was mostly written by Protestants, we should be skeptical of American historians depicting King George III as erratic, as primary source accounts may have been overblown. In any event, George exacerbated diplomacy by overreacting.

Complicating communications, the lag of ships crossing the Atlantic confused colonists and rulers alike. Atlantic trips could last anywhere from a few weeks to a few months. A becalmed ship could drift for days depending on weather in the Doldrums, the equatorial zone where prevailing trade winds meet. That made it difficult to follow the parliamentary debate over the Stamp Act. Such delays were especially common on trips to America, as trips back to England or Europe tracked westerly trade winds further north in the Atlantic.

When Parliament rescinded the tax they also issued the First Quartering Act that stationed troops and warships in the colonies and the Declaratory Act of 1766 that reaffirmed their right to tax. It was as if Parliament said, “Okay, you got your way this time, but don’t forget that, from here on out, we do have the authority to tax you whenever we please and here are some soldiers to remind you of it.” These occupying forces were an ongoing source of tension since most had to find part-time work to supplement their low pay and they slept in town commons in unsanitary camps. In England, they offered felons a choice between prison and the military – considered a virtual death sentence because of the likelihood of contracting disease or dying in combat or at sea. Running a global empire was not all tea and crumpets.

When Parliament rescinded the tax they also issued the First Quartering Act that stationed troops and warships in the colonies and the Declaratory Act of 1766 that reaffirmed their right to tax. It was as if Parliament said, “Okay, you got your way this time, but don’t forget that, from here on out, we do have the authority to tax you whenever we please and here are some soldiers to remind you of it.” These occupying forces were an ongoing source of tension since most had to find part-time work to supplement their low pay and they slept in town commons in unsanitary camps. In England, they offered felons a choice between prison and the military – considered a virtual death sentence because of the likelihood of contracting disease or dying in combat or at sea. Running a global empire was not all tea and crumpets.

The Townshend Duties of 1767-68 threw fuel on the fire, especially since part of the tax went toward the troops there to collect the tax in the first place, which Ben Franklin likened to “setting up a blacksmith’s forge in a magazine of gunpowder.” It would be like if, today, a significant portion of your income taxes went toward funding the IRS, whereas really it’s ~ .003% of the budget. The Townshend law taxed imports that colonists relied on from Britain such as lead, paper, paint, glass, and tea. Resistors boycotted these goods in organized fashion, forming non-importation groups to network their cause. Women sewed their own homespun to undersell English cloth exports. Wearing the rougher cloth became a badge of resistance. In the 20th century, Mahatma Gandhi did the same with Indian cotton to protest British rule, and his Salt March to peacefully boycott British-taxed salt by harvesting it instead from evaporated seawater triggered a movement that led to India’s independence in 1947. Gandhi, in turn, influenced Martin Luther King, Jr. Boycotting works if everyone sticks to it.

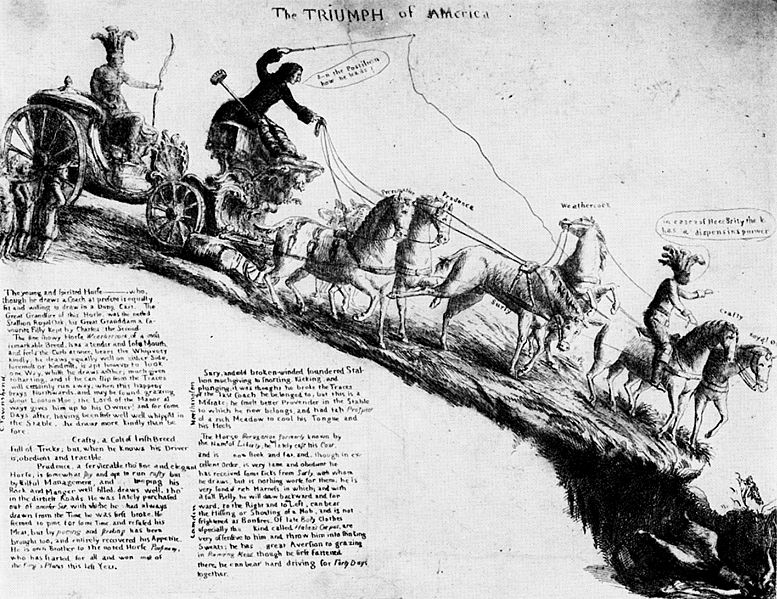

Fearing that taxes would only make the colonists more self-sufficient, English merchants and manufacturers blinked first, pressing Parliament to rescind the duties. After Parliament repealed all the taxes except for the one on tea in 1770 (Americans couldn’t grow their own tea), rebels could see a clear pattern that resistance got results. It had seemingly worked twice with the Stamp Act and Townshend Duties. A cartoon in an English newspaper entitled “Triumph of America” predicted that Parliament would struggle to rein in the American team of horses from here on out (below), representing what we’d today call the “slippery slope argument.” In the meantime, non-importation organizations provided a valuable network colonists could build on in future years. In just two years, the British had managed to alienate pretty much every level of society: merchants and lawyers with the Stamp Act, consumers with the Townshend Duties, and laborers with Redcoats competing for part-time jobs.

The Triumph of America: Lord Pitt Drives America’s Triumphal Chariot into the Abyss, Cartoon Appeared in London Newspapers, 1766

A relative lull ensued in the early 1770s with no new taxes and little broad-based resistance. True believers like the Sons of Liberty worked overtime to fire everyone else up with anniversary celebrations of the great Stamp Act revolt while reminding people of the many still unresolved disputes. These disputes included trade, ongoing taxes, state-sanctioned religion, military occupation, and the right of customs officials to search and seizure through legally-questionable Writs of Assistance. These writs were like long-terms warrants or could amount to what we’d today call stop-and-frisk to interrogate smugglers.

In 1772, a Rhode Island branch of the Sons of Liberty led British customs officials on a chase that grounded their vessel, the HMS Gaspée. Before high tide could free it, the mob boarded, looted, and burned the ship, then shot and imprisoned the captain. They were retaliating for recent British attempts to enforce their longstanding trade restrictions on the colonists, and local courts offered the Brits no hope of justice since they sided with smugglers. Their ringleader was a local merchant, pirate, and slave trader named John Brown, not to be confused with a famous namesake abolitionist a century later. This John Brown’s great-grandfather started Rhode Island & Providence Plantation with Roger Williams in 1638 and the family founded their namesake Ivy League university in Providence.

Charles DeWolfe Brownell, The Burning of the Gaspee, 1892, John Brown House, Providence RI, Photo by Author

The protest echoed an earlier riot in Boston surrounding seizure of wine merchant-smuggler John Hancock’s sloop the Liberty. While historians don’t calculate British taxes as being worthy of much protest, it may be that the crackdown on smuggling did more to threaten New England’s economy. Hancock was an elite businessman who had enjoyed a special handshake arrangement with the forenamed Governor Hutchinson; he paid Hutchinson a kickback to look the other way. But when the Crown sent more troops to occupy Boston after the Stamp Act Riots, that arrangement ended. The Crown’s stricter rules backfired because the wealthy Hancock formed an alliance with maltster-brewer Sam Adams whom, according to traditional accounts at least, was associated with the unrulier Sons of Liberty street mob. Modern scholarship indicates that Adams was less a rabble-rouser than an upright conservative looking to establish a new “Christian Sparta” and that rowdier depictions of Adams came from pro-British Loyalist sources. In any event, John Hancock and Sam Adams teamed up to trade goods on the black market and resist British authority. They helped to cement revolutionary ties across class lines.

Tensions also mounted over control of colonial timber, with the Crown mandating that the tallest trees be preserved as masts for the Royal Navy. Some New Hampshire sawmills were hoarding logs marked for the navy and their owners’ arrest set off the Pine Tree Riot. The light fines assessed to the guilty parties underscored the limits of British authority in more remote areas of their empire, and some historians suggest that the arguments over lumber set the stage for the Tea Party the following year. As with the Gaspée Affair, the Pine Tree Riot resulted from disagreements over who had ultimate control over the American economy, the colonists or British Parliament.

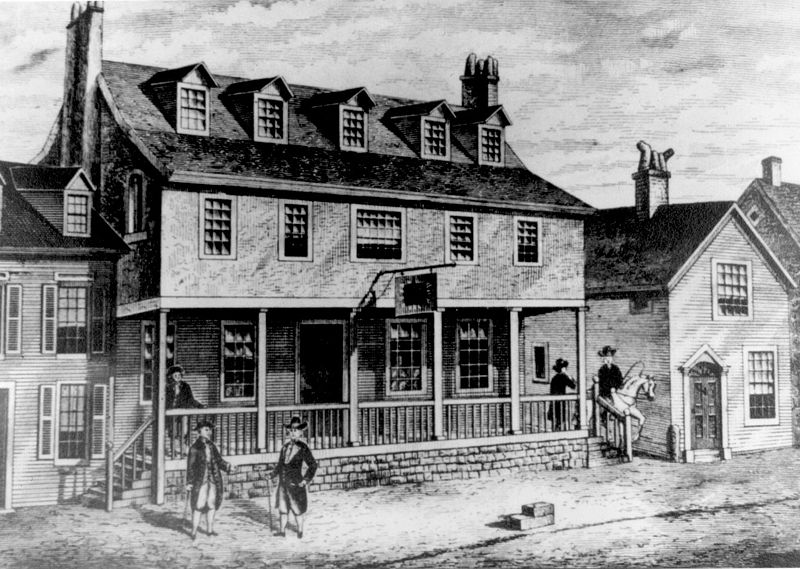

Rebels met in taverns, airing their grievances and reinforcing their organizational ties. Bars served not only as meeting places but also post offices and courthouses. Even the strict Puritans legally required that each town have a heated tavern next to the unheated churches where congregations attended “all-day” service since they broke for meals next door. Four important rebel taverns were the Raleigh in Williamsburg, Virginia, Fraunces in New York City, Green Dragon in Boston, and Tun in Philadelphia, that doubled as a Masonic Lodge and is where the Marines formed in 1775. Boston’s famous branch of the Sons of Liberty met in the basement of the Green Dragon, the “Headquarters of the Revolution.” As a saying went, over brew a revolution grew.

Lacking cloud space or a smartphone, Benjamin Franklin even initiated a colonial-wide postal system to keep people in contact that later morphed into the U.S. Postal System (like the Marines, the USPS is a year older than the U.S., beginning in 1775). The overriding issue was that the colonies had enjoyed over a century of neglect before the British tried to assert greater control in the mid-18th century. But by then there was seemingly no pressing need for British protection, at least on land; we’ll see later that Americans overestimated their ability to protect themselves at sea. And the aforementioned Proclamation Line, while not always obeyed, inhibited western expansion. Import taxes continued on tea and sugar.

Some of the colonists’ complaints were longstanding, predating the post-French & Indian War taxes. Everyone, regardless of their faith, had to pay tithes to the established Church of England formed when Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church in 1534. In America, the Church of England was usually known as the Anglican Church. While laws allowing for the mild torture of non-Anglicans in nine of the colonies went mostly unenforced, the tax aggravated colonials who prided themselves on their relative religious freedom in relation to English and Europeans. And there were colonies like Virginia where over half of the Baptist and Presbyterian ministers had been jailed briefly at some point, especially if they preached to African Americans or, worse yet, were African-American. Other Protestant dissenters had holes poked in their tongues or hounds released on them.

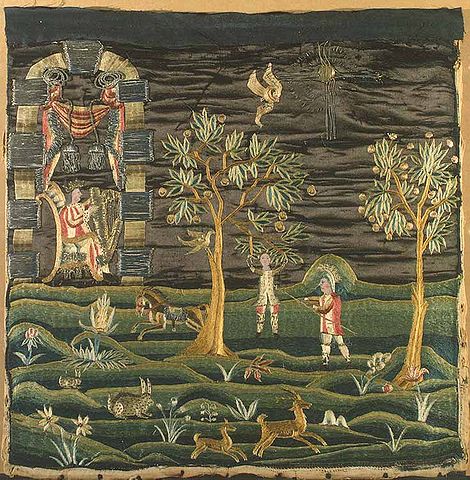

As we saw in earlier chapters, some dissenters even migrated mainly for religious freedom. A pattern emerged of dissenters from the established church agitating for more freedom while Anglicans tended, by and large, to appreciate the benefits of being in the British Empire. These Anglicans were more likely to remain Loyalists to Britain once musket balls flew in 1775. Non-Anglican ministers like Jonathan Mayhew and John Witherspoon, in turn, could fire up their congregations, leading British politicians to blame bad relations on the “Presbyterian Revolution.” In the House of Commons, Horace Walpole bemoaned that “Cousin America has run off with the Presbyterian parson (Witherspoon), and that is the end of it.” The Great Awakening primed a generation of colonial American Protestants for rebellion against authority, as had the Calvinists’ and Quakers’ break from the established church. Historian Christine Heyrman called the First Great Awakening a “dress rehearsal” for the Revolution. The artist that created this (primary source) silk needlework below depicted the Biblical figure of Absalom suffering under the rule of his father, King David, symbolized by King George III. The king on the left is playing his harp, oblivious to the anguish of his children (the colonists), while the figure executing Absalom, Joab, is dressed as a Redcoat.

The Hanging of Absalom (silk, weft-silk fabric, foil-wrapped threads, paper, watercolor), Attributed to Faith Robinson Trumbull, c. 1770. Lyman Allyn Art Museum @ Connecticut College, New London

Finally, Redcoat or “Lobster-Back” soldiers still occupied town commons and took up jobs, which was an ongoing nuisance. The American Revolution, while led by an elite of mostly multi-millionaires (adjusted for inflation), was launched in a combination of streets, taverns, and pulpits. While the stakes weren’t as earth-shatteringly high as those of the 20th century (i.e. fascism vs. democracy, communism vs. capitalism, etc.), it was nonetheless a spirited uprising expressed in rallies, debates, celebrations, songs, pamphlets, posters, and sermons. And the revolution was violent by modern standards when it degenerated into war in 1775. But, as of the early 1770s, that was a long way off and no one anticipated war or a new country.

Boston Massacre

In 1770, two years before the Gaspée Incident and Pine Tree Riot, Lobster-Backs in Boston caused an uproar when they fired their muskets into an angry crowd. Ten days earlier, British customs officer Ebenezer Richardson shot dead eleven-year-old German immigrant Christopher Seider, which had the whole city on edge. Seider was part of a mob throwing rocks at Richardson’s windows. Similar to American experiences later in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, the British found that counter-insurgency (occupying) forces, even those with instructions to treat civilians well, tend to wear out their welcome because of these inevitable conflicts.

According to legend, shortly after Seider’s death, a cable-maker asked a Redcoat if he was looking for work and when he replied yes the man retorted, “Wee then, go and clean my s**t house [outhouse].” That led to a small-scale melee. Then on March 5th, a soldier assaulted a young wigmaker’s apprentice, striking him on the head with his musket. The apprentice was hollering at him to pay his boss and the soldier ignored him at first because he’d already paid. The ensuing fracas forced the retreating Redcoats back in front of their customs house where a mob pelted them with snowballs/ice, rocks, oyster shells, and sticks — taunting and daring them. Some brandished clubs and cutlasses (short swords). One rioter yelled, “Come on you rascals! You bloody backs, you lobster scoundrels, fire if you dare, God damn you, fire and be damned, we know you dare not.”

At the Vietnam War protests at Kent State in 1970, students harassed National Guardsmen because they knew the soldiers wouldn’t retaliate, but one did. The same thing happened in Boston 200 years earlier. One snow-baller hit a Redcoat hard enough that he dropped his musket and fired it when he picked it back up. Others followed suit and fired into the crowd, killing five men and injuring six. They were probably scared out of their wits being surrounded by an angry mob of nearly 400.

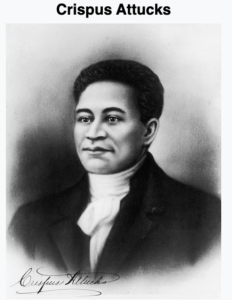

Rather than being lynched, the guilty soldiers were lucky enough to be defended by John Adams, who got their trials delayed and sentences reduced to branded thumbs (m for manslaughter). Adams wanted to demonstrate Americans’ ability to conduct a fair and just trial amidst an atmosphere of vigilantism. Quoting from an established legal text, Hale’s Pleas of the Crown, Adams said, “It is better that five guilty persons should escape unpunished than one innocent person should die.” A murder charge would’ve brought the death penalty but they used the Benefit of Clergy loophole to avoid it, an 18th-century law whereby a first offender (not necessarily of the cloth) could get a reduced sentence by reciting Scripture. Adams, falling short of today’s standards of political correctness, argued for an even lighter sentence since they were surrounded by a “motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and mollatoes, Irish teagues, and outlandish jack tarrs [sailors].” One victim, Crispus Attucks, was of African and, perhaps, Native American descent. Adams played to the jury’s prejudice by selectively highlighting witness testimony that underscored Attucks’ aggression toward the British. We’ll hear more from Attucks in Chapter 18 as he becomes a pawn in the culture wars of the 1850s.

Rather than being lynched, the guilty soldiers were lucky enough to be defended by John Adams, who got their trials delayed and sentences reduced to branded thumbs (m for manslaughter). Adams wanted to demonstrate Americans’ ability to conduct a fair and just trial amidst an atmosphere of vigilantism. Quoting from an established legal text, Hale’s Pleas of the Crown, Adams said, “It is better that five guilty persons should escape unpunished than one innocent person should die.” A murder charge would’ve brought the death penalty but they used the Benefit of Clergy loophole to avoid it, an 18th-century law whereby a first offender (not necessarily of the cloth) could get a reduced sentence by reciting Scripture. Adams, falling short of today’s standards of political correctness, argued for an even lighter sentence since they were surrounded by a “motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and mollatoes, Irish teagues, and outlandish jack tarrs [sailors].” One victim, Crispus Attucks, was of African and, perhaps, Native American descent. Adams played to the jury’s prejudice by selectively highlighting witness testimony that underscored Attucks’ aggression toward the British. We’ll hear more from Attucks in Chapter 18 as he becomes a pawn in the culture wars of the 1850s.

Publicists like silversmith-recycler-poet Paul Revere spun the event as a massacre (above), exploiting the shooting into a cause célèbre against British rule. Ironically, the Boston Massacre occurred the very day Parliament rescinded most of the Townshend duties, March 5th, 1770, though no one on either side of the pond was aware of the coincidence because of the communication lag and lack of submarine fiber optic cables.

The Bostonian Paying the Excise-Man, 1774, British Propaganda Cartoon Depicting Tarring & Feathering of British Customs Officer After the Boston Tea Party, Brown University

Boston Tea Party

Britain left the Townshend tax on tea, leading to a crisis three years later, also in Boston. In 1773, Parliament restored the nearly bankrupt British East India Co.’s monopoly as the sole importers of tea to the Americas. Tea was as popular in the 18th century as coffee today and the BEIC joint-stock company was so large and powerful that it flew its own flag. Its army was twice as big as Britain’s Redcoats. As an attempt to dissuade Americans from smuggling Dutch tea, the Tea Act actually lowered the price of tea below the going rate by exempting the BEIC from taxes, despite continuing fat dividends and high salaries. The company could now ship directly from China to America, skipping the British import duty, and sold directly to distributors instead of middlemen. By lowering the price, the new law followed the same pattern set by the earlier Sugar Act. Parliament was allowing the BEIC to dump its surplus in America at a cut-rate to undersell smugglers.

Salvaging the BEIC buoyed stock markets in London and Amsterdam, as it was the second-biggest financial concern in the empire behind the Bank of England. In fact, the company’s revenue was actually greater than that of the government and many company men had bought their way into Parliament. But the BEIC was struggling in India due to political unrest, like that in America, and famine in Bengal, which the British callously exacerbated. Powerful people stood to lose fortunes. For the wealthy at least, the British East India Co. was what we’d now call “too big to fail.”

In 1773, this lowering of tea prices might have pleased American consumers, but some didn’t like the precedent of cutting out smugglers. Consumers often complain that middlemen just raise prices, ideally preferring what economists call disintermediation. But that price hike is what middlemen call a living. Smuggling tea from the Dutch and molasses from France was a time-honored right Americans wanted to hold onto even if it raised prices. The more conspiratorial tea-sippers joined forces with those who disliked the “drug” to start with, or who disliked the flea infestations that often accompanied British boats from China. Others protested the blurring of lines between the British government and the country’s biggest corporation (BEIC). Tapping into the mostly dormant organizations of 1765 and 1767, protesters organized a boycott throughout the colonies and most major harbors either turned away the tea boats or stored the tea in warehouses to sell later, in Charleston’s case to help finance rebellion.

In Massachusetts, Governor Thomas Hutchinson ordered the tea off-loaded into a warehouse in customary fashion. But, in the ensuing “Destruction of the Tea” or “Tea Riot” as it was known until sanitized for 19th-century schoolchildren, the Sons of Liberty — fortified by rum punch consumed at the Green Dragon, led by Sam Adams, and dressed as Mohawk Indians to maintain their anonymity — stormed aboard three small vessels and dumped 45 tons of tea into Boston harbor; actually into the mud and clams since the tide was out. Forty-five was symbolic, signifying the Sons of Liberty’s support for parliamentarian John Wilkes, whose Issue #45 accused King George of lying to Parliament. Wilkes then fled England. This was hard work as each of the 342 chests of tea they hauled out of the ship’s hold weighed 400 pounds.

Southern colonists saw the tea destruction as juvenile vandalism and the British were not amused either. They demanded immediate compensation for lost income amounting to over one million dollars, adjusted for inflation. They saw any leniency toward Boston as signaling leniency toward rebels like Wilkes in England. Parliament even berated Ben Franklin over the affair just because he was an easy, in-person target, even though he was in London on a mission to improve colonial relations and supported Massachusetts compensating for the tea after he learned of the riot.

Like most colonials of his generation, Franklin was proud and grateful to be British, but after his interrogation before the King’s Privy Council in the “Royal Cockpit” behind the Palace of Whitehall, so named because Henry VIII once held cockfights there, he began to entertain thoughts of independence. When they scapegoated him for the Tea Party, accusing him of inciting a riot he’d tried to prevent, Franklin started questioning his loyalty to Britain. While he maintained Loyalist and English friends, historian Sheila Skemp described it as the moment “when Franklin became an American.” That cost him his relationship with his Loyalist son William and, more importantly, the Brits lost a key ally who could’ve come in handy down the road. Franklin’s popularity soared back in the colonies, though. Four years later, when Franklin secured an alliance with France to help fight Britain (next chapter), he wore the same coat he’d worn in the cockpit, to “give it a little revenge.”

The history of the history of the Tea Destruction is interesting in its own right. Not only did textbooks change the name to Tea Party after the 1830s, there’s little mention of the event at all in early histories of the Revolution prior to that. Early historians wanted to downplay any potentially criminal behavior in association with the Revolution, and early American political leaders didn’t want to encourage vigilante behavior among their own angry citizens. Vandalism is just the tip of the iceberg, though, when it comes to the potential complications in how nations study and celebrate their beginnings. Historian Danielle Allen noted: “At the end of the day, to be a successful society is to avoid revolution. So we have to celebrate as our origin something that every society also wishes to avoid.”

British Clamp Down

Though contemporary Southerners likewise saw the initial tea dumping as inappropriate, they sided with Massachusetts when Britain overreacted by closing Boston’s harbor (allowing shipping in Salem), barring hometown sheriffs and jury trials (sending cases to England), and dismantling the colony’s locally-elected government (the General Court). Boston merchant John Andrews wrote his brother-in-law in Philadelphia that the British threatened to “make the town a desolate wilderness…with grass growing in the streets.” In the early-20th century, British overreactions to protests in South Asia triggered escalation, leading to India’s independence in 1947. The same happened in colonial America in the 1770s, though in each case the British might’ve struggled to maintain control regardless of whether they tried lenient or harsh policies. Yet, it wasn’t inevitable that either country would gain independence, because not much in history is.

After the Destruction of the Tea, the British strengthened the First Quartering Act, allowing for troops being housed in any public building (e.g. warehouses, barns, etc.) if local authorities didn’t cooperate in building barracks. A myth grew that this Second Quartering Act allowed troops to stay in citizens’ homes, which was useful Patriotic propaganda. Redcoats, after all, were rough characters that men didn’t want sleeping under the same roofs as their wives and daughters. From time-to-time, Redcoats did actually invade homes uninvited and, when they did, sometimes harassed its inhabitants or spread smallpox. This contributed to Americans barring the practice during peacetime in the Third Amendment to the Constitution. You may have wondered why, in the Bill of Rights, you have the constitutional right to not host soldiers against your will. Ironically, though, because of the exact wording of the Bill of Rights’ protection against it, soldiers can stay in your house during a war if so determined by lawmakers: “No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.” Really, that means that lawmakers could require quartering during a war, but that hasn’t happened.

In a separate act meant to appease French settlers to the north and west — but one that rebels misinterpreted as being aimed at them — the British allowed Catholics to worship freely in Quebec, no longer having to swear oaths to the Anglican Church, and, at least according to American patriots, banned self-government there. The British were actually enacting traditional French civil codes and making sure French citizens could vote and worship along with the British. Though French Canada was vanquished in 1763 as a political entity, their settlers weren’t forced to evacuate. Québécoirs speak French to this day.

In the 18th century, their presence stoked anti-Catholic sentiments among Protestant Americans, as did the Quebec Act. Paul Revere drew a widely distributed cartoon entitled This Sir, is the Meaning of the Quebec Act, showing Catholic bishops celebrating having conquered the Americas. Sam Adams wrote that “more was to be feared from Popery in America” than taxation. Really, French Catholics then just had religious freedom, of the exact sort that British American rebels supposedly supported themselves against the Church of England.

More importantly, the Quebec Act reinforced the Proclamation Line that aimed to keep Americans out of that very area, especially since Quebec expanded to include the entire Ohio Valley and Great Lakes — now western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. In modern college sports terminology, nearly the whole Big 10 was in Canada. Two more laws, the Restraining Acts, expanded British control over New England governments that had run virtually on their own for 150 years except for a brief interruption in the 1680s and prohibited American fishing in the North Atlantic, an important and lucrative industry. Other colonies were angered rather than intimidated by the crackdown on Boston. Collectively, these Coercive (or Intolerable) Acts triggered a chain of events that led to armed conflict, but not yet calls for independence. In Virginia, proto-Founders issued the Fairfax Resolves affirming their basic rights within the English system and renewing calls for boycotts. Virginian Patrick Henry concluded a dramatic speech at St. John’s Church in Richmond with the rallying cry Give Me Liberty Or Give Me Death!

Virginians weren’t just upset with the Coercive (Intolerable) Acts or Quebec Act. The Chesapeake tobacco gentry was descending further and further into the debt of English merchants and they suspected the British of depressing tobacco prices to worsen their plight. Just as New England smugglers resented mercantilist constraints on tea and rum, Southerners complained that the British economic system threatened their independence and even honor. Planters more accustomed to domination than submission complained incessantly that the British were reducing them to “slavery.” The forenamed Edmund Burke, who otherwise supported the colonies, bemoaned that, for slaveholders, freedom was “not only an enjoyment, but a kind of rank and privilege.” Even Virginian Edmund Randolph agreed that “the existence of slavery, however, baneful to virtue, begat a pride which nourished a quick and acute sense of the rights of a freeman.”

Also, Scottish banks were calling in Virginia planters’ loans because the banks had over-invested in the struggling British East India Co. — the same outfit Parliament was trying to save with the Tea Act that triggered the Boston riot. Finally, the British dissolved Virginia’s House of Burgesses the same way they had Massachusetts’ General Court, with royally-appointed Governor Lord Dunmore assuming full control and revolutionary politicians retreating to the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg to plot their next moves.

Patrick Henry’s fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson was even bolder than Henry or the Fairfax Resolves authors, arguing, in the spirit of John Locke, that rulers were servants of the people, not vice-versa, in a pamphlet entitled Summary View of the Rights of British America. Jefferson argued that the Virginia House of Burgesses should have equality with Parliament and that King George should avoid becoming “a blight on history.” Writing in public in 1774 that kings should avoid being blights on history wasn’t like Tweeting an op-ed about Barack Obama or Donald Trump. Jefferson was guilty of a capital crime at this point and would commit his dipped quill to parchment even more treasonously two years later with the Declaration of Independence. Britain tried to teach its colonists a lesson by punishing Boston severely but their strategy backfired, only rallying other Americans to the point they were willing to risk their necks.

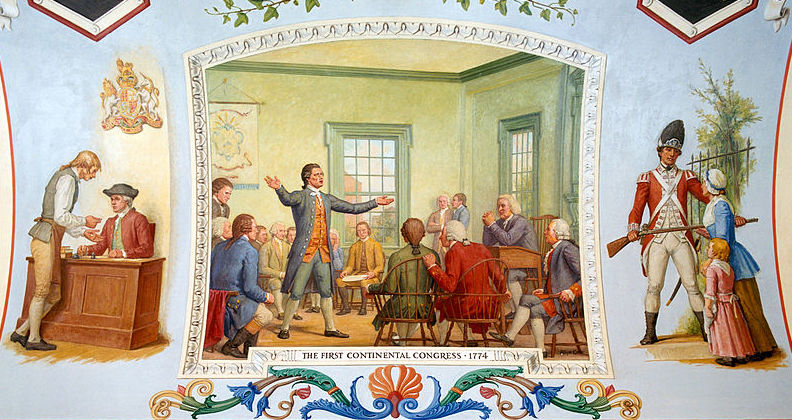

Colonial representatives met under one roof for the first time, forming the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia and creating shadow governments called Committees of Correspondence atop the foundation of earlier networks like the non-importation clubs. Along with churches, coffee houses, and taverns, they provided what network theory would describe as nodes, with couriers like those described in the section below providing links. In retrospect, the First Continental Congress was the germ of the future U.S. government though no one knew it at the time. Still, as of 1774, there was no talk of breaking away and forming a separate country, only addressing grievances within the British Empire. But Continental Congress threatened to embargo all British trade if the Intolerable Acts weren’t repealed.

Siege of Boston & United States Birth Pangs

Small-scale sporadic fighting broke out across New England and rebels stole British ammunition and weapons stockpiles from places like Fort William & Mary in New Hampshire and Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Outside Boston in April 1775, Minutemen trained to be “ready at a moment’s notice” mustered in preparation for fighting Redcoats. It turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy as Redcoats (aka Regulars) were sent to keep Minutemen from drilling outside Boston, leading to a fight. This was the setting for the famous “Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” to warn the Minutemen of Lexington and Concord that the “British were coming.” Actually, he didn’t yell anything because he would’ve given himself away, but that was part of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem Paul Revere’s Ride, written on the eve of the Civil War in 1860. The phrase wouldn’t have made sense anyway because Revere and other rebels saw themselves as British. Revere and his friends had to cross the Charles River in silence to avoid the attention of a nearby warship, but their oars would’ve made too much noise in their metal locks. So a nearby woman offered her flannel petticoat, which they tore up and wrapped around their oars.

British General Thomas Gage hoped to find Sam Adams and John Hancock in Lexington or Concord to imprison them and to seize rebel armaments. The warning system set up by Revere, William Dawes, and ringleader Joseph Warren gave militia time to prepare, though Revere never made it to deliver the word. Redcoat sentries captured him while another man, Samuel Prescott, hurdled a fence on his horse and evaded capture. Why don’t we know about Prescott? Because his name wouldn’t have rhymed with “listen children and you will hear…” in Longfellow’s poem (neither would Revere’s, for that matter, if he’d kept his French Huguenot birth name, Rivoire). The Minutemen had been in a local tavern all day and would’ve been caught by surprise without Prescott’s message. Following the “Shot Heard Round The World” at the North Bridge in Concord — no one knows for sure who shot first, least of all those who’d been in the tavern all day — farmers fired away at the British from trees and behind stone walls as the shocked Brits high-tailed it back to Boston like jackrabbits at a greyhound convention.

Then, Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and Benedict Arnold seized British cannons by surprise at Fort Ticonderoga. Troops under Henry Knox hauled them by hand across upstate New York and Massachusetts to the outskirts of Boston, where 30k angry Yankees surrounded the Redcoats. The Second Continental Congress sent Virginian George Washington north to form the rebel militia into a coherent army. They didn’t have anyone else at their disposal with military experience and Washington even wore his old uniform from the French & Indian War to congressional meetings. Washington took command of what he called the “Troops of the United Provinces of North America.” U.P.N.A. easily enough could’ve become the name of the new country. Washington’s task was to take ten companies of riflemen from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland with him to link with the Massachusetts militia. At no point in the coming war, though, did he really have a full-blown professional army. Washington struggled throughout to unify various state militias, with citizen-soldiers often coming and going on their own terms.

Historians now suspect the Troops of the United Provinces of North America moniker morphed gradually into United States of America, with no one really drawing attention to that fact that they’d named a new country. Of course, there was no new country yet despite Continental Congress ruling as a de facto government and having already formed an army, navy, and marines. On Christmas Day, 1775 Washington wrote about the “United Colonies” and, on January 2, 1776, his aid used the term United States of America in a letter.

This is worth a brief digression if you’ll allow because the USA is an interesting name regardless of who came up with it. Had they gone with a single word (e.g. France, Mexico, Japan) they may have come up with something like America or Columbia, perhaps Washington ten years later. Instead, the name describes a concept, maybe because they improvised it gradually. The federal idea of a national tier sharing power with existing states underneath was embedded in the name of the country before the Founders actually chose or designed such a system, or even declared independence. That wasn’t a given; they could’ve started a country with no states or separate states with no unified country. Their choice is only obvious in retrospect.

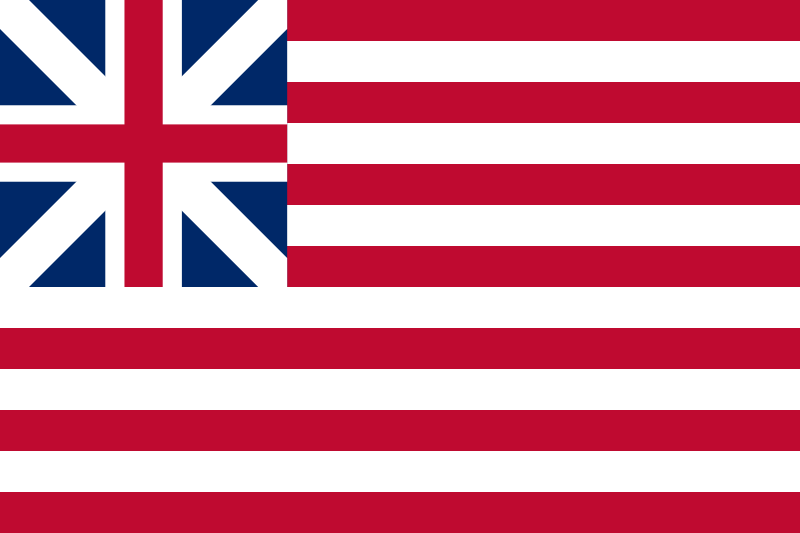

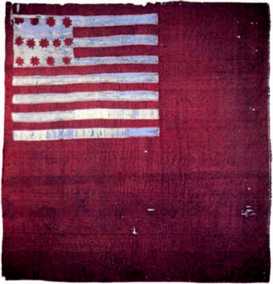

Also around this time, Washington’s army unfurled the Grand Union Flag, or Continental Colors, a precursor to the Stars & Stripes. At first blush, they seem to have stolen their design from (of all people!) the British East India Co., importers of the very tea the Sons of Liberty ceremoniously tossed into Boston’s harbor in 1773. Yet, they put some thought into this transitional banner. The thirteen stripes represent colonial autonomy, but the Union Jack in the upper left corner shows their continued allegiance to the United Kingdom. You can see how easily something like Commonwealth status (e.g. Australia, Canada, New Zealand) could’ve come about. This pennant indicates that compromise was still on the table as of 1775. By 1777, though, you see early versions of a flag with the same layout but stars signifying new states in the upper left. As this site chronicles in detail, the first-ever known image of such a flag comes from the Chester County Militia, flown at the Battle of Brandywine (outside Philadelphia) in 1777.

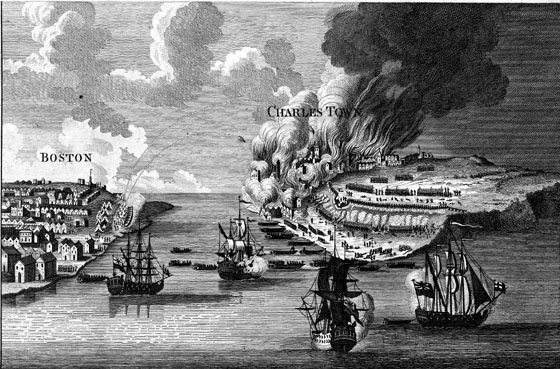

Back to our story. With Washington in charge at Cambridge, Massachusetts, his army kept the British trapped in the Siege of Boston. Instructed not to fire “until they saw the whites of their enemies’ eyes” to preserve limited ammunition, rebels prepared for Redcoats to come across Charleston Bay from Boston proper, where they awaited on Breed’s and Bunker Hill. They fought the British to a standstill until they ran out of munitions and retreated. It was a costly victory for the Redcoats, whose leader remarked that the success “was too dearly bought.” They’d expected to punish an unruly mob rather than fight an army that looked them in the eye.

View of the Attack on Bunker’s Hill with the Burning of Charlestown, Engraving by Lodge After Drawing by Millar American Antiquarian Society

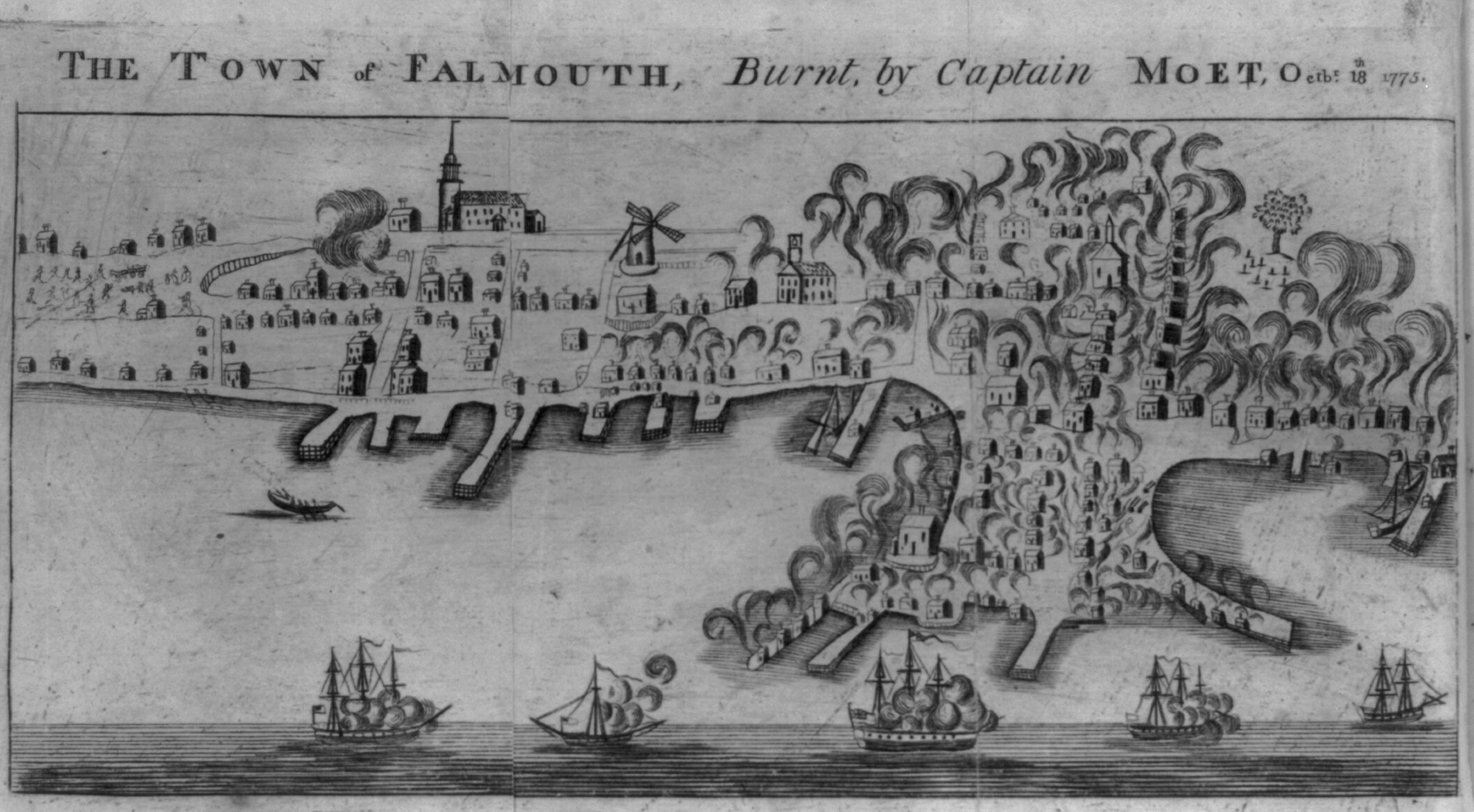

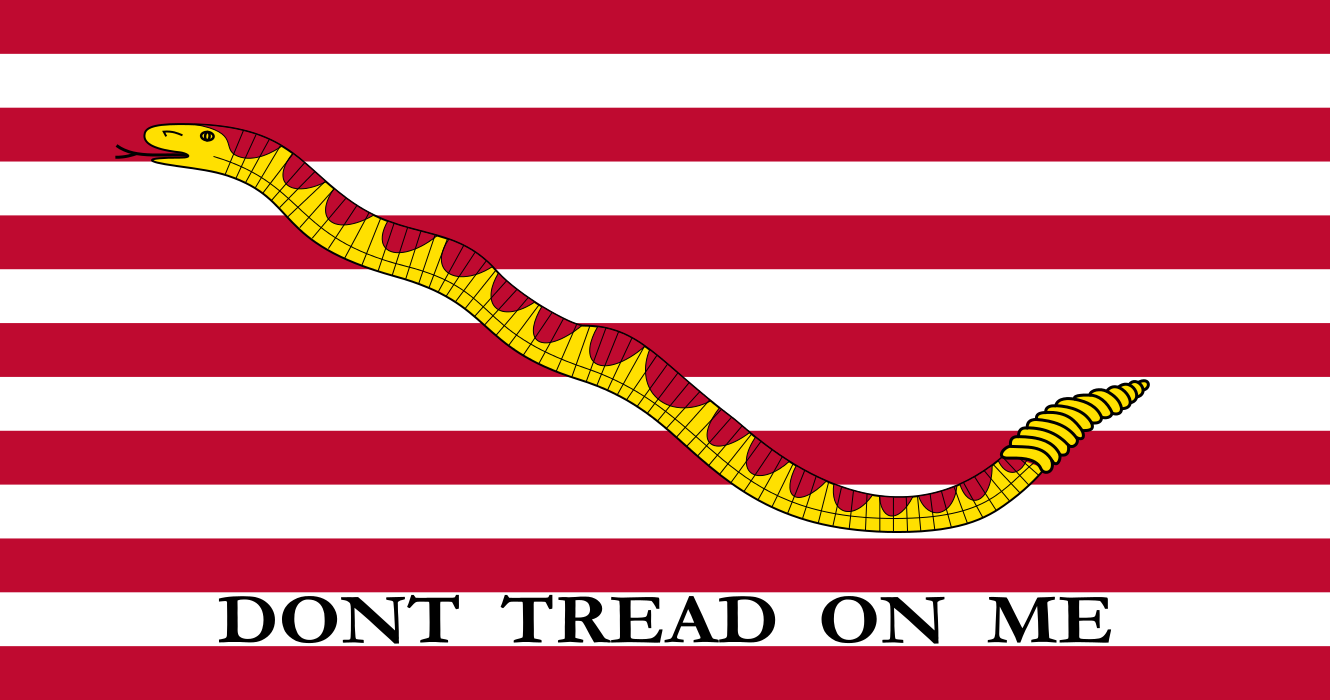

The British put Boston astern, agreeing not to burn the city if the Americans didn’t fire on them as they sailed for home. Before that, in October 1775, the Royal Navy laid siege to Falmouth, Maine (now Portland), burning ships and razing the harbor town. The British also bombed and burned Norfolk, Virginia on New Year’s Day 1776, where rebels kept the fire ablaze by burning Loyalists’ homes. The Burning of Falmouth motivated Continental Congress to start its own small Continental Navy, the beginning of the modern branch. Their first U.S. Navy Jack was more direct than the Grand Union Flag, (supposedly) with a snake saying don’t tread on me, designed for the early Marines by none other than Ben Franklin, he of the Join or Die cartoon from 1754. Even if raising a militia was technically within their colonial rights, forming a navy and marines was an act of treason.

The British put Boston astern, agreeing not to burn the city if the Americans didn’t fire on them as they sailed for home. Before that, in October 1775, the Royal Navy laid siege to Falmouth, Maine (now Portland), burning ships and razing the harbor town. The British also bombed and burned Norfolk, Virginia on New Year’s Day 1776, where rebels kept the fire ablaze by burning Loyalists’ homes. The Burning of Falmouth motivated Continental Congress to start its own small Continental Navy, the beginning of the modern branch. Their first U.S. Navy Jack was more direct than the Grand Union Flag, (supposedly) with a snake saying don’t tread on me, designed for the early Marines by none other than Ben Franklin, he of the Join or Die cartoon from 1754. Even if raising a militia was technically within their colonial rights, forming a navy and marines was an act of treason.

Collectively, all these battles in New England touched off the military phase of the American Revolution. However, in the meantime, Continental Congress sent an Olive Branch Petition to King George III asking for reconciliation. Olive branches are a universal sign of peace. The Union Jack was still on their flag, after all. But George refused their offer, if he even read it. He called the rebel colonists “deluded” and their leaders “traitorous.” George’s rejection of the petition lent credence to John Adams’ argument that the rebels had already passed the point of no return. Continental soldiers burned copies of the King’s speech after it was read to them. Given the debate about representative government then ongoing, George was a fitting example of the downside to hereditary rule. Instead of seeking a compromise or resolution, the erratic, unstable king issued the Prohibitory Act in December 1775 that blockaded all American harbors. Given the colonies’ dependence on Atlantic trade, it was an act of virtual economic warfare.

It’s tempting for us to project modern notions of democracy on colonial Americans and assume that they all opposed monarchical authority. But many colonists felt betrayed by a king to whom they owed their allegiance precisely because it was his job to protect them. The tension was inherent in Britain’s colonial model because, in order to enforce law and order in the Empire, King George had to wage war on his own subjects. In this version of Backstory (35:40-37:14), historian Peter Onuf explains this “protection covenant.” For many Americans, the problem was that George broke the covenant, not that there was a covenant. John Adams didn’t want a stronger Parliament in relation to tyrannical King George; he longed for a stronger king to protect the colonists from a tyrannical Parliament. When the revolutionary Virginians met at Raleigh Tavern after their royally-appointed Governor Dunmore dissolved their House of Burgesses, they toasted King George. This is an important distinction because it explains why some framers lobbied for a stronger executive branch run by an individual (a president) during the Constitutional Convention twelve years later. It’s also a reminder of how late in the game most rebels were still loyal to England rather than envisioning independence. But forming a military was a defiant step on their part, and King George III’s Prohibitory Act was a harsh retaliatory measure.

Canadian Campaign

Preparing for war with the mother country, Second Continental Congress sent a delegation led by Ben Franklin to Quebec to try and convince Canadians to join the cause as a fourteenth colony. When they refused, Congress launched an ill-advised campaign to conquer Canada to prevent the British from using it as a staging area. This was the first of two U.S. attempts to conquer Canada, the other being the War of 1812. George Washington ordered troops to respect the Canadians’ Catholic faith while taking the colony, helping to establish a principle of religious freedom at a time when Protestants dominated Continental Congress and some rebels were leveraging anti-Catholic sentiment to oppose the Quebec Act.

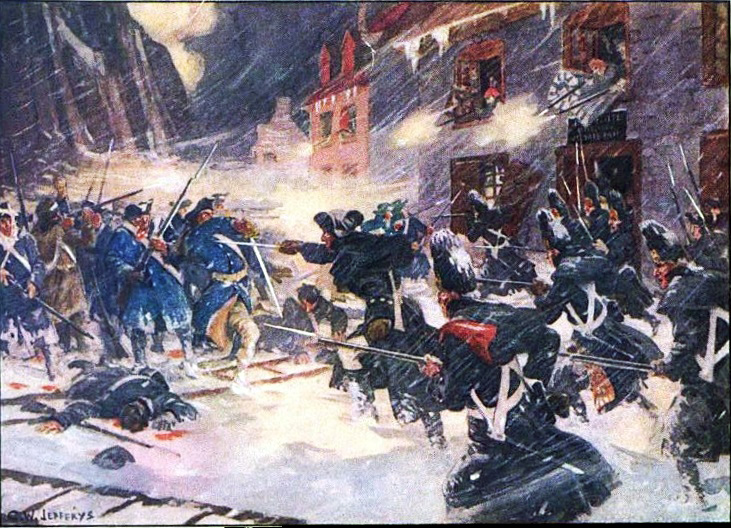

The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec December 31 1775, John Trumbull, Yale U. Art Gallery

After slogging hundreds of miles through the snow across New England, an invading force led by Richard Montgomery and future traitor Benedict Arnold took Montreal but failed to capture Quebec City and the campaign collapsed (painting above). We’ll hear more from Arnold in the next chapter as he first became a crucial hero for the rebels before turning coat. Some troops quit when the church bells tolled midnight on New Year’s Eve because they were only being paid through 1775. With this defeat at the Battle of Quebec, the Invasion of Canada ended. The newly formed Continental Marines also laid siege to British outposts in Nova Scotia and Nassau, Bahamas. Not yet formally at war, and not yet even a country, Continental Congress was attacking the British from Canada to the Caribbean.

Common Sense

Common Sense

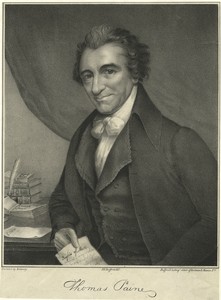

In February 1776, recent English immigrant Thomas Paine published a pamphlet as influential as any ever written on American soil, arguing for Americans to break from Britain and form their own country. He was part of the English Whig faction that had long resisted absolute, centralized power, especially from the monarchy or royal ministers. Paine, a former corset-maker and customs official, suggested a decentralized system similar to how the country would soon be set up in its first decade under the Articles of Confederation (Chapter 10).

Breaking away from Britain altogether had seemed preposterous just a year before, but Paine had the audacity to say publicly what many had already been thinking in the back of their minds: ‘Tis Time To Part. Paine claimed that everyone he overheard or spoke to thought nationhood was inevitable in America; it was just a matter of when not if. Washington was already moving in that direction while fighting the British and King George’s rebuttal of the Olive Branch Petition solidified the idea of independence in many people’s minds because the King himself suggested that it was already happening.

Around a third of Americans remained staunchly loyal to their king and would remain so during the coming war, but another 33-40% now found themselves solidly in the rebel camp, with another third or so neutral. Paine’s Common Sense sensibly countered the main arguments against independence. Aren’t Americans the children of the parent British Crown? “Then the more shame upon her conduct. Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families.” Doesn’t hereditary rule prevent civil wars? “Were this true, it would be weighty; whereas, it is the most barefaced falsity ever imposed upon mankind. The whole history of England disowns the fact.” Was America too small? It was in 1776, but simple demographic extrapolation, including research by Ben Franklin, showed that it would soon be larger than Great Britain. “There is something very absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.” Weren’t kings enshrined by Divine Right? “Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.” While not Christian himself, Paine understood the rebellion’s religious underpinnings. He wrote the pamphlet in the language and cadence of a sermon, cleverly inviting his audience to consider that Old Testament Jews had rejected monarchical authority. Paine wrote with clear italics and commas so that Common Sense could be read out loud in sermons, taverns, and coffeehouses.

All this came from a man who’d been genuinely fond of the British Empire. Like Ben Franklin, Paine saw Britain’s as the best, freest political system on Earth. But both men passed a threshold and came to view British rule as increasingly and irredeemably aristocratic and unenlightened, despite the freedoms that had been won there in relation to other European countries. They knew British Americans had it good, but things were backsliding in the wrong direction.

Colonial coup d’états

The key shifts toward actual independence happened within individual colonies. Continental Congress instructed each colony to form their own, independent governments on May 10th, 1776. States were forming and declaring independence before the upper, national tier did on July 4th. The democratically-elected Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly favored staying in the Empire, but a more radical militia took over the colony in an armed coup. No shots were fired as the Assembly led by John Dickinson backed down in the face of 4k protesters and voluntarily gave up power. Dickinson (left) had helped launch the rebellion with his resistance to the Townshend Duties in Letters From An American Farmer (1767) and reworked some of Jefferson’s writings into Declaration of the Causes & Necessity of Taking Up Arms (1775). Consequently, his overthrow at the hands of independence-seeking rebels in 1776 indicates how far the Revolution had progressed.

The Pennsylvania Committee of [Militia] Privates created a new government that favored independence from Britain and granted voting rights to militia members. Much to the chagrin of John Adams, who favored a more stable and conservative future, Pennsylvania got rid of all property qualifications for voting, a radically democratic step at the time. That feature purportedly led to a big shouting match between Adams and Thomas Paine at a Philadelphia hotel. Many years later (1805), lamenting his radically democratic politics, Adams described Paine as “a mongrel between pig and puppy, begotten by a wild boar, on a bitch wolf.”

Pennsylvania severed its ties to the British Crown in May 1776. The coup was influential because its participants convinced Continental Congress to declare that all colonial legislatures that derived their power from the Crown should be suppressed. Paine took part in this rebellion personally, along with mathematician James Cannon and scientist Thomas Young. Benjamin Franklin supported the coup and Pennsylvania’s new constitution, as did others in Continental Congress like Sam Adams and John Adams, despite his reservations about the broadened suffrage. All this was happening in the same town, Philadelphia, where Continental Congress met, making it all the more important. That critical third or more of the population that favored independence seized the initiative and three other colonies declared their independence from the mother country even before Pennsylvania: South Carolina (March 26th), North Carolina (April 12th), and Rhode Island (May 4th). Without these four states, it’s unlikely Continental Congress would’ve tried to break away and form a country. The Revolution was both a top-down and grassroots rebellion.

Take a break, read the Declaration of Independence, then return to read about its origins and how its meaning evolved later.

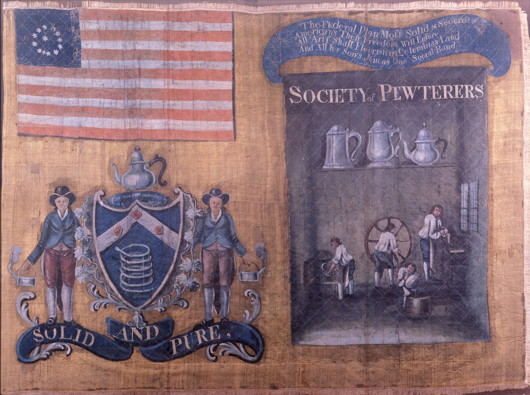

Independence

Churches, trade guilds, and various colonial bodies and assemblies followed these states’ lead. In American Scripture (1997), historian Pauline Maier researched and documented how these local declarations coalesced into a national declaration. Continental Congress unified them under one umbrella and renamed the “United Colonies” the United States of America. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a “motion for independency” on June 7th for “free and independent states.” Congress formed a committee to write up a declaration on June 11th, approved the resolution on July 2nd — the day it was announced in Philadelphia newspapers — and approved the written declaration announcing the resolution on July 4th, 1776, signing it on August 2nd. If the colonies were going to break from Britain their best chance of survival was to unite as one country, at least for military purposes. As Franklin punned, “We must all hang together, or surely we will hang apart.”

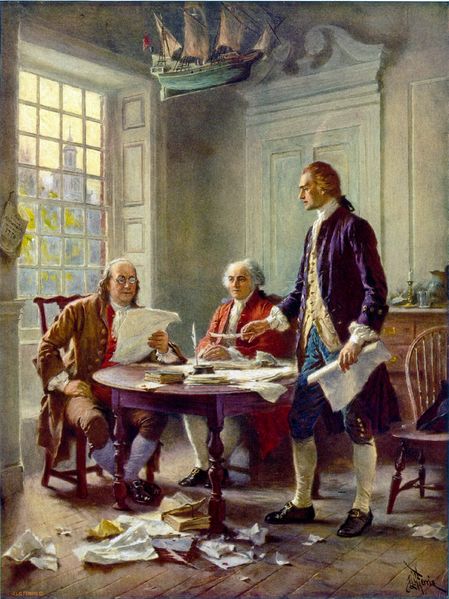

The committee of five that Continental Congress assigned to write the Declaration included Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin. They assigned the actual writing portion of the task to the youngest of the group, Jefferson (33), because of his reputation for penmanship and perhaps his proven disregard for the noose. “He was no Moses receiving the Ten Commandments from the hand of God,” wrote Maier, “but a man who had to prepare a written text with little time to waste and who … drew on earlier documents of his own and other people’s creation.” While Jefferson’s product lacked originality, it nonetheless became the most famous revolutionary document in world history, the Declaration of Independence. This articulate justification for the American stance shifted blame from Parliament, heretofore the usual target, directly onto the king, beseeching King George III to tame Parliament. It was especially intended for other European eyes, such as the British-hating French, who might be enlisted as allies in the fight to come, and the Spanish. Real countries are diplomatically recognized by other countries — why, for instance, that ISIS never became a real country even when they controlled an area in Iraq and Syria the size of Indiana. The committee hoped that the Declaration would help win recognition from key countries.

They did not have to look far for language or ideas. Jefferson’s introduction is similar to that of his fellow Virginian George Mason’s preamble to that colony’s own declaration, though they were written simultaneously. Ben Franklin also convinced Jefferson to change “we hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable, that all men are created equal” to “self-evident,” an old lawyer’s trick to make disagreeing with a point seem unreasonable. Jefferson drew his broader inspiration from the European Enlightenment (Chapter 7). He tapped into the Radical Whig ideology of British resistors to tyranny such as Thomas Paine and John Locke. Locke argued in the late 17th century for “natural rights” to life, liberty, and estate, at least for upper-class white males — similar to Jefferson’s life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness (Locke used the pursuit of happiness phrase himself elsewhere in his writings). They meant happiness the way the Greek philosopher Aristotle used eudaimonia, which wasn’t so much having fun as being engaged and living a meaningful, constructive life. Had Jefferson texted the Declaration, he wouldn’t have added a yellow, smiley face emoji in the happiness passage. As we saw above, even Whigs in England like Edmund Burke argued on behalf of the colonists. Closer to home, Sam Adams argued for the colonists’ right to life, liberty, and property in 1772. Radical English Whigs had long argued that “all men are created equal.” Prior to 1774, American rebels didn’t say or write anything more radical than former Whig Prime Minister William Pitt’s aforementioned speech against the Stamp Act in the House of Commons in 1765. Colonists were especially well-versed in “country whig” ideology that traced to the English Civil War and Commonwealth of the mid-17th century, when Puritan republicans dethroned Charles I. They were eternally vigilant and suspicious of conspiracies on the part of the king and his ministers to usurp power from Parliament and read pamphlets to that effect. The American Revolution was a natural extension of the republican trajectory English Whigs had been on for a while. Declarations, in general, were British, tracing to the forenamed Magna Carta (1215) and Declaration of Rights (1689). America’s was a Whig revolution on the outskirts of the Empire, led by men familiar with what they saw as their British rights.

Some have even argued that Thomas Paine wrote the Declaration, but he was too controversial of a character for Congress to ascribe his name to it. For people who believe that theory, based on his wording and use of capital letters, the mysterious handprint on the back of the document might be Paine’s. However, the writing seems in line with Jefferson’s. In any event, Paine was mostly written out of American history for the next century-and-a-half because he argued in The Age of Reason (1794-1807) that sacred religious texts were really written and inspired by humans. Aside from the aforementioned insults Adams lobbed at him, Paine’s deism inspired others to call him a Judas, reptile, hog, mad dog, souse, louse, and arch-beast. That’s just what we see in print. A century later, Teddy Roosevelt dismissed Paine as a “filthy, little atheist.” Despite his enormous role in founding the U.S., which we’ll see more of in the next two chapters, I can safely assume my reader didn’t attend Paine High School.

Some misconceptions surround the Declaration. First, it did not create a new government the way the Constitution did in 1789, though it did create a new country independent from Britain as long as the rebels won. It was essentially a declaration of war against Britain, or at least a divorce petition. If the rebels had lost, it would just be a forgotten document in a civil war and we wouldn’t be calling its signers founders. Second, while Jefferson argued that the rebels were exercising God-given rights, he took care to attribute their powers not to the Judeo-Christian God, but rather the God of Nature. That was remarkable phrasing given that the colonies had far more Christians than Deists, even if Deism was disproportionately popular among the Founders themselves. Most representatives in Continental Congress were Christian and Jefferson didn’t intend to exclude Christianity so much as to include and broaden beyond it. Some of the Founders recognized that America was a diverse country religiously and people of all faiths and beliefs would be welcome under the tent. They enshrined that principle legally in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights 15 years later.

Third, Jefferson did not abolish slavery in his original draft, as is sometimes thought, though he condemned Britain for abetting a slave trade that he called “execrable commerce.” Mostly, he was criticizing the British for inciting enslaved workers to rise up against their American masters, as they started to do in 1774. In blaming the British king for the slave trade, Jefferson was anticipating, however lamely, the long-standing questions from England about why “we always hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes” (Samuel Johnson). The Declaration Committee probably dropped Jefferson’s condemnation of slavery to avoid drawing attention to the brazen hypocrisy (and projection) of a slave-owner and other slave-owners condemning the trade. For those who think that criticizing slavery is merely an anachronistic, politically correct application of today’s standards onto yesteryear, it’s worth noting Jefferson’s description of “cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him [King George], captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” To his credit, Jefferson did un-hypocritically try to ban the importation of slaves into Virginia in 1778 and abolish slavery in all new western territories in 1784. In the optional podcast below, historian Robert Olwell conjectures that might be why Jefferson changed Locke’s life, liberty, and property to life, liberty, and happiness in the Declaration, to avoid future legal wrangling over slaves as property. Likewise, Abraham Lincoln argued 80 years later that Jefferson snuck in the all men are created equal phrase to help future generations abolish slavery. Whatever the case, Jefferson’s fellow planters in South Carolina and Georgia would’ve refused to join a union without slavery. Those states were important economically and geographically, especially with Spain lurking as rulers of Florida at the time. But slavery was legal in all thirteen colonies/states as of 1776 and some northern politicians objected to abolition as well.

In Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance & the Origins of the United States of America (2014), University of Houston historian Gerald Horne argued that avoiding an anticipated British Empire-wide abolition of slavery was one cause of the rebellion. England didn’t actually end up abolishing slavery until 1833 but, if Horne is right, supporting slavery must be included along with others mentioned in this chapter as a significant cause of the American Revolution. In that line of reasoning, Americans fought in 1776 partly for the same reason Confederates rebelled in 1861. South Carolina and Georgia are key to Horne’s argument, as many slaveholders scared off by insurrections in Jamaica and Antigua migrated there, and they feared that freed slaves in Spanish-held Florida would lead a war against the southern British colonies. Independence inspired them because they feared that Britain might abolish slavery. In Virginia, the first militias raised to fight were to put down a potential slave revolt. Once the rebellion started, the British offered freedom to enslaved workers in many areas who helped them fight rebels via Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation. Many masters were fighting to maintain the liberty to enslave. Also, Britain’s highest court implied in the 1772 Somerset v. Stewart case that any colonial slaves who made their way to England would be freed, rendering imperial power even more threatening than it would’ve been due to just taxes, navigation acts, and religious tithes. Historian Alan Taylor wrote that “patriots rallied support by associating the British with slaves, bandits, and Indians.”