Historians used to call the period after the War of 1812 the Era of Good Feelings. Textbooks commonly titled chapters that, and the one prior the Age of Jefferson or Jeffersonian America to signify the influential two-term presidency of Thomas Jefferson. I don’t know if things were really cordial enough after the war to justify the Good Feelings moniker but, if so, then it stands to reason there must have been more hostility in the periods before and after. So, we’ll call the one before the Era of Bad Feelings.

As we’ll see in this chapter, that was true enough from 1800-1815. One Founder killed another, that same man conspired with the head of the military and Spain to carve out a new country on the western frontier (hemming in the U.S.), New England considered secession, America went to war with Britain again, the Americans burned down the Canadian capital, the British returned the favor by burning Washington, Indian relations were worse than usual, and the 1815 eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia led to the “year without a summer” in New England because of persistent sulfate fog, killing crops and livestock. A Shawnee chief named Tecumseh even put a curse on the U.S. Meanwhile, Barbary Pirates brought Yankee shippers to heel in the Mediterranean while a megalomaniac named Napoleon Bonaparte rampaged across Europe, disrupting diplomacy and trade to the point that it threatened America’s export economy. Yet, despite these growth pangs, the United States emerged from the Napoleonic Wars intact and stronger, setting the stage for the relative calm of the Good Feelings Era.

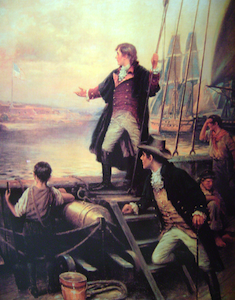

Jefferson 1800 Banner, Smithsonian Museum of American History. Fourteen-Year-Old Craig Wade Discovered This Relic Blowing Down Railroad Tracks In Pittsfield, Massachusetts In 1959.

Election of 1800

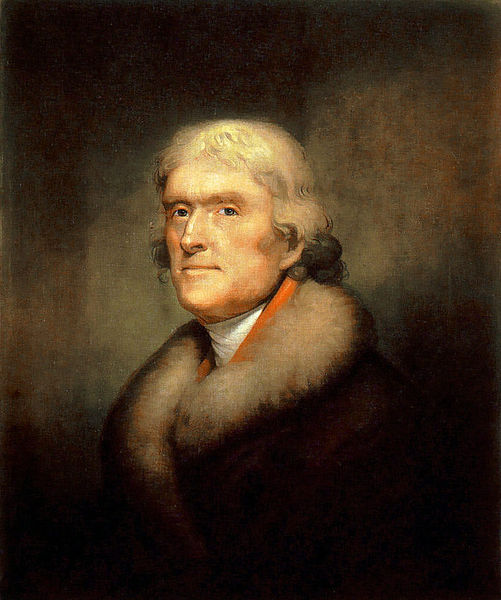

The 19th century kicked off with a nasty, contentious election — the kind that makes politics vexing if interesting to follow. Jefferson liked to call the 1800 election a revolution, which had some truth to it but is a bit of stretch since the basic Constitutional framework didn’t change. Because of the unpopularity of Federalist policies like the Whiskey Tax, Jay Treaty, and Sedition Act, the Democratic-Republican Jefferson won his presidential rematch with Federalist John Adams in 1800. In so doing, he helped set the U.S. on a path toward greater democracy that culminated in full political representation for American adults by 1965, though that wasn’t his intention. But Jefferson supported universal white manhood suffrage, and that was a significant expansion of the electorate beyond white, male landowners.

Per standards of the time, neither candidate gave speeches, campaigned directly, or asked for votes. It was left to their supporters to provide commentary. Adams’ spin doctors claimed that Jefferson’s lack of Christianity would compel him to legalize murder, rape, and incest. Associating him with the worst of the French Revolution, Adams’ supporters warned what a Jefferson presidency would mean: “Be prepared to see your dwellings in flames…female chastity violated, or children writhing on a pike.”

Jefferson’s camp paid off newspapers for favorable editorials and called Adams a “howling hermaphrodite” — a hideous hermaphroditical character which has neither the force nor firmness of a man nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” Helping to establish the standards of accuracy still used in negative campaign ads, Adams’ camp countered that Jefferson was a “mean-spirited, low-lived fellow (plausible enough based on the accusations toward Adams), the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father” (close enough; he had two fully Caucasian parents).

While the mud-slinging might not have scored high on today’s Politifact truth meter, the U.S. nonetheless pulled off a contested election and transfer of power from one faction to the next without civil war. In other words, partisanship didn’t degenerate into anything worse than the usual lies, character assassination, and smearing that typify elections in an open democracy. The 1800 election is a good example of where retrospection imparts to us a false sense of inevitability. To wit: it’s easy looking back to take a peaceful election for granted after we know nothing bad happened, but there was nothing automatic about it from their perspective as it unfolded. In many countries and many instances, such scenarios have led to civil war or candidates not accepting election results and the U.S. had its own problems in 1860-61, 1876, and 2020-21. On that score, the 1800 election was most revolutionary in that it didn’t lead to a real revolution. The peaceful transfer of power isn’t a nice feature of democracies; it’s the essential linchpin. Without it, you can’t have elections, in which case you’re not living in a democracy.

The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans feared one another for good reason, especially since Alexander Hamilton implied that he might use the army he raised during Washington’s administration against the “Virginians” [Democratic-Republicans]. The controversial 1800 election raised tensions more, even though the two candidates most famous for contesting it, oddly enough, weren’t Jefferson and Adams; rather Jefferson and his VP candidate, Aaron Burr. Unlike 1796, voters now chose tickets, or pairs, for the presidency. However, the ballots weren’t clearly marked with P and VP lines and there was a mix-up in the plan for one elector to leave Burr off the ballot. Burr claimed he’d actually tied Jefferson in the election 73-73 which, technically, he had. Burr was charming, intelligent, courageous (he’d fought bravely in the Quebec campaign in 1775-76), and his grandfather was a famous theologian, Jonathan Edwards, but he obviously wasn’t running for president. Voters knew they were voting for Jefferson. But his ploy threw the election into Congress, where none other than Hamilton, Jefferson’s old nemesis, cast the deciding vote against Burr (he’d already helped Jefferson some by criticizing Adams). Said Hamilton: “In a choice of Evils, let them take the least — Jefferson is in every view less dangerous than Burr.” The Twelfth Amendment (1804) clarified the double-ticket process going forward.

Burr Duel & Burr Conspiracy

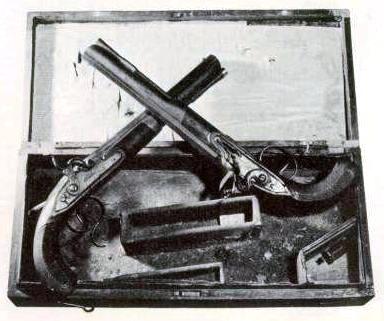

Burr and Hamilton had a quarrelsome history. Burr resented George Washington promoting the lower-ranking Hamilton to general (partly because Washington caught Burr looking through his private papers), and Hamilton backed John Jay over Burr for New York Governor in 1795. Then Hamilton backed his nemesis Jefferson over Burr in the 1800 presidential controversy. Writing that Hamilton had stymied his ambitions at every turn, the “Dark Father” (Burr) challenged Hamilton to a duel, killing him in 1804 before fleeing the country.

Many people considered gunfighting by the traditional code duello passé by the late 18th century, but thin-skinned men of honor carried on the tradition through the 19th century, especially in the South and Old West (it was never really “traditional” in the first place, having been popularized recently by the Continental Army, who picked up on it from Redcoats). Historian Joanne Freeman points out that often gentlemen didn’t intend to kill each other and Hamilton had wiggled out of several potential duels in the past by settling arguments before they reached the field of honor. He had room to do likewise with Burr but couldn’t muster an apology. He was depressed anyway after his son Philip was killed in a duel defending his father’s honor. Dueling was illegal in most places, with punishments varying regionally. Hamilton may have been undone by his own scheme to cheat. He brought long-barreled pistols with hair-trigger settings that only required half of the usual ten pounds of pressure to pull and accidentally squeezed off an early shot over Burr’s head as he was intending to take aim. Other historians, including biographer Ron Chernow, assert that Hamilton missed intentionally and told several people he would ahead of time. Confusing matters more, witnesses disagreed as to who shot first. In any event, Hamilton missed but Burr hit Hamilton above the right hip, fatally piercing his abdomen, kidney, and spine. Sadly for Hamilton’s wife Elizabeth, she lost her son and husband to duels in the space of three years — killed on the same spot in Weehawken, New Jersey.

Suffice it to say, Jefferson dropped Burr from the VP ticket in 1804. Yet, given what came next, it’s surprising that Burr’s duel with Hamilton is what he’s most known for. The bitter ex-vice president, now wanted for murder in New Jersey, purportedly tried to blunt American expansion by starting a new empire carved out of Spanish territory and (hopefully) rebellious Kentucky and Virginia, and including New Orleans. Worse, he conspired with James Wilkinson, Senior Officer of the Army, equivalent today to Army Chief of Staff — a man of whom future president Teddy Roosevelt said, “In all our history, there is no more despicable character.” That’s a stinging insult considering Benedict Arnold’s treachery in the Revolutionary War. Wilkinson served in the Continental Army during the Revolution and even led successful campaigns in the St. Lawrence Valley during the War of 1812 that comes after this story. Yet, after his death, transcripts revealed that for much of that time this dirtbag was an agent of the Spanish Crown, conspiring against the U.S.

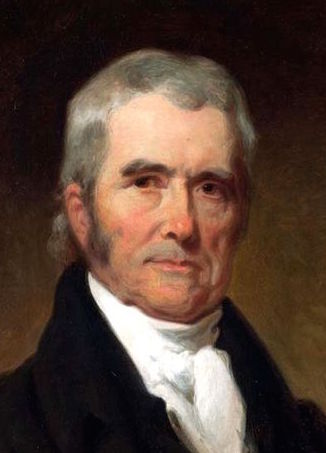

James Wilkinson, by Charles Willson Peale, 1796, Independence National Historical Park Collection, Philadelphia

Burr convinced Jefferson to make Wilkinson president of the new Louisiana Territory. The purported plan was for Wilkinson to use connections to pry Kentucky and Tennessee loose from the Union. Burr, meanwhile, would lead an army and cabal of planters that would carve a new western country out of portions of the Louisiana Territory and lands he’d leased in Spanish-held Florida and Texas. Some Spanish agents were under the impression that they were working for them, but Burr was conspiring with Spanish traitors to double-cross Spain and carve out his own nation. Burr’s men used a small island in the Ohio River bordering present-day West Virginia (then Virginia) as a weapon and supply depot, causing suspicion among local authorities and conspiracy rumors in local newspapers. Jefferson didn’t pay much attention at first as his focus was on naval problems in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. As Burr’s small force sailed down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers toward New Orleans to launch their plan, Wilkinson panicked and ratted out his co-conspirator to Jefferson without ever revealing his own role. The real army captured Burr in Alabama and returned him to Richmond, Virginia in chains. This is at least the common interpretation of Burr’s purported scheme. We don’t have much primary source evidence as to what actually happened, so it’s difficult to distinguish truth from what might have been hearsay or paranoia on Jefferson’s part, and we’ll likely never know for sure.

A Virginia district court cleared Burr in a generous high misdemeanor and treason trial in 1807, meant to set a high standard as to what constitutes treason and how much evidence it would take to prove it. Treason, after all, was (and is) a capital offense, meaning punishable by death. Jefferson imprisoned Burr and wrongly proclaimed his guilt before the trial. But Chief Justice John Marshall, presiding over the federal circuit court in Richmond, understood that, without raising the bar high, political adversaries would forever be trying to eliminate each other through treason accusations; and he didn’t appreciate his second cousin Jefferson’s pre-trial meddling in the case. Being put to death for treason required either a confession or at least two incriminating witnesses, but the prosecution could only muster one each for any of Burr’s actions, and a few others whose testimony seemed to conflict. It was also unclear whether Wilkinson had doctored a letter to him from Burr. Marshall asked prosecutors, “Is this the best you’ve got?” It was and he dismissed Burr. At the request of the defense, the court subpoenaed War Department documents and letters from Wilkinson to Jefferson they thought might help exonerate Burr, but Jefferson didn’t want to concede the judiciary’s power to subpoena the executive branch and withheld most of the material (LC). A key problem for the prosecution was that Burr’s treason hadn’t progressed far beyond the planning stages by the time they apprehended him in Alabama. Burr went to Europe to organize more war against the United States, but British and Spanish leaders weren’t interested in his crackpot plans, so he returned in disguise to live in New York.

Judge Marshall reinforced separation of powers between the executive and judicial branches by not helping Jefferson convict Burr, and Jefferson did likewise by defying the judiciary’s subpoena. But SCOTUS overturned Jefferson’s precedent 8-0 in Nixon v. United States (1974), when Richard Nixon appealed to executive privilege to avoid turning over incriminating tapes to a federal district court.

How Revolutionary Was the 1800 Election?

There is some truth to Jefferson’s assertion about the 1800 election being revolutionary. For one, since Adams favored breaking down church-state separation (declaring fast days, for instance, as president) and Jefferson was religiously unorthodox, the election was a referendum on religious freedom. Jefferson’s victory ensconced the freedom the Founders wrote into the Constitution a decade earlier and dramatic denominational growth in the early 19th century supported Jefferson and Madison’s notion that religious freedom actually helped rather than hindered religion. Jefferson also ended the whiskey tax (as promised) and reduced the federal debt by 33%. And Jefferson democratized the military as we’ll see below with his founding of the academy at West Point. Finally, while his administration didn’t actually overturn the Alien & Sedition Acts — they took on a life of their own, in fact, in the 20th century — they let enforcement lapse. Jefferson didn’t object, though, when state governments in New York and Pennsylvania prosecuted Federalist newspaper editors for seditious libel during his tenure, his original objection to the Sedition Act being that the national government could not abridge freedom of the press, especially for Democratic-Republican journalists.

Most importantly, the fledgling country now had a leader who endorsed spreading the vote to all white males at a critical stage in its history. Without this early move toward universal manhood suffrage, it’s debatable whether the U.S. would have gone so far down the path toward democracy for everyone. As it was, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans grew into a broad-based people’s party in the Jacksonian era of the 1820s and ’30s, known by then simply as the Democrats. The spread of white manhood suffrage arguably put the U.S. on a trajectory toward voting rights for minorities and females. The ancient Roman poet Virgil wrote, “As the twig is bent, the tree inclines.” It’s not quite that simple, though, because it was important to many of those same working-class white men to deny the vote to women, Blacks, Indians, etc. Some of the working-class white males were more adamant about discriminating against others than rich white males like Hamilton were.

President Jefferson himself was a slaveholder who, by now, had dropped his earlier abolitionist leanings. He embodied white America’s contradictions. As we saw in the previous chapter, it was widely rumored at the time that Jefferson maintained “conversations” (sexual relations) with his enslaved concubine, Sally Hemings, known as “Dusky Sally” or the “African Venus” to his Federalist enemies. How the author of the Declaration could have enslaved people is a complicated question, not just to critics anachronistically applying modern standards. Jefferson was widely criticized for his hypocrisy at the time, especially when many of his Virginia neighbors freed or manumitted their enslaved workers after the Revolution. Jefferson arranged to eventually free his and Sally Hemings’ four surviving children, though, per a prenuptial-type agreement he’d struck with the teenager in exchange for her returning from Paris with him in the 1790s. She would’ve otherwise been freed by French law had she remained. He struck a similar deal with Sally’s older brother, James Hemings: he was freed in exchange for returning to teach American chefs French cooking. Historian Rob McDonald observed that, for plantation descendants, “family trees were often tangled vines.”

Jefferson’s Mixed-Race Descendants @ Monticello, 2016, Photo By Author From Thomas Jefferson Foundation Photo

Jefferson’s exchanges with African-American astronomer Benjamin Banneker (previous chapter), along with letters to others about Banneker, reveal a duplicitous side to his personality that resisted racial progress even as he purported to support it (see optional podcast below). And Jefferson’s only book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), contains passages so racially repugnant they’d make a modern Klansmen blush. Yet he argues in the same book (Query XVIII) that, in the event of an uprising, the enslaved would be justified: “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever,” and suggests he’s open to changing his mind on racism. Appreciating and/or loathing Jefferson aren’t mutually exclusive. Rapper Daveed Diggs, who originated Jefferson’s role in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton (2015), put it bluntly if crudely: “You don’t have to separate these things with Jefferson. He can have written this incredible document (the Declaration) and several incredible documents with things that we all believe in, and he sucks. Those are both true and we really have to stop separating them. That’s when we get into trouble and stop letting people be whole people.”

Jefferson played up his republicanism in his 1801 inauguration, when he walked in the mud beside his horse and took pains to avoid the near monarchical foppery of the Washington and Adams “coronations.” When visitors, especially foreign ambassadors, came to the Executive Mansion, Jefferson answered the door himself in slippers with his hair down to accentuate his non-kingliness. State meals there featured “pell-mell” seating, with no attention paid to rank or prominence in terms of what order people sat in. In contrast, Washington never spoke to regular people and often stood on a raised dais to accentuate his authority.

Religiously, Jefferson kept his Deism under wraps, except for maintaining support for what he called “separation of church and state” — a phrase not found in the Constitution, but one subsequent judges have used as a precedent because Jefferson, in essence, nearly co-authored the First Amendment with James Madison and they both described the amendment as such in a letters (Chapter 7). Federalist voters who’d hidden their Bibles after being told Jefferson would confiscate them came to realize it wasn’t going to happen, similar to people today waiting for leaders to confiscate their guns or gold. Why would Jefferson confiscate Bibles when he advocated religious freedom?

Jefferson also set about transforming the military, preventing it from being monopolized by nobility the way it was traditionally in Europe. Likening himself to the Roman aristocrat and retired general Cincinnatus, Washington presided over the Society of Cincinnati (1783-present), whose original members included former Continental Army and French officers but no American militia. Instead of allowing the nepotistic and cliquish Federalists from simply passing down officer commissions to their own friends and sons, Jefferson set up the U.S. Military Academy at West Point to draw cadets from all over the country, in the tradition of the Revolution’s citizen-soldiers. When you consider how factionalism nearly escalated into violence in the 1790s, you can appreciate why Jefferson wanted to purge the military of Federalist domination. While he didn’t want a large military, he wanted a democratic, smart one that drew from the people and could build better bombs and bridges than the enemy. The heart of early West Point was thus the Army Corps of Engineers. As the only real engineering school in the Early Republic, West Point graduated many of the men who mapped and built western railroads and mines in the first half of the 19th century. President Washington actually had the original idea of building an academy at West Point in the 1790s, when none other than Jefferson nixed the plan. It was different now that Jefferson could control the curriculum and admissions.

Sage of Monticello

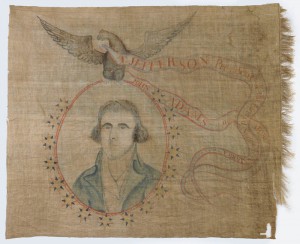

The scientific emphasis of West Point’s early curriculum embodied the Enlightenment, as did most of Jefferson’s passions. He was not just a gentleman scientist; he was an inventor, musician (violinist), linguist (seven languages), architect, educator, brewer, and voracious reader. His home served as an informal museum for western fossils and artifacts. Jefferson even wrote a 500-page Garden Book (1766-1824) that is still in print. His personal library was the largest in America and seeded the Library of Congress in Washington, which still uses his numerical classification system (LLC) for organization. He built a four-sided Lazy Susan bookstand to accommodate whatever four books he happened to be reading at the time. Jefferson was a prolific letter writer — over 19k he penned still exist — and wanted to retain his own copy of anything he sent. So, he invented a mimeograph device that attached to his wrist and made a copy as he was writing. He wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776 on his custom-built portable writing desk. Jefferson also built the country’s first swivel chair, on which he penned the famous document. He invented a spy cipher and modified designs of the macaroni maker and moldboard plow. He introduced America to white asparagus and English peas and even campaigned on behalf of the tomato, a vegetable then thought to be poisonous only because it can be when unripe. Jefferson was a pescatarian, mixing seafood in with vegetables.

And like one of his idols, Isaac Newton, Jefferson obsessed over the Bible despite not being a Christian. Since he thought Christianity had been corrupted by superstition, he took it upon himself to cut-and-paste his own private version of the New Testament Gospels, this one devoid of miracles. Using a scalpel, he assembled this moral pamphlet, the aforementioned Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (aka Jefferson Bible), in four columns: English, Latin, Greek, and French. The public had no knowledge of the Jefferson Bible until after his presidency, but copies were given to freshman congressmen from 1904 to 1954. Jefferson wasn’t the first to take liberties cutting-and-pasting Scripture. Librettist Charles Jennens condensed and imported passages from the Old and New Testaments in G.F. Handel’s exalting Messiah oratorio (1741), including many of the parts that Jefferson later left out.

Jefferson designed his own plantation, Monticello, outside Charlottesville, Virginia, a model of Classical Palladian design including several pioneering gadgets. After completion, he decided that he hadn’t built it properly to take full advantage of the prevailing winds to move breezes through in the summer, so he had it torn down and rebuilt. It’s safe to say he probably would’ve settled for the first version without enslaved workers to rebuild it for him. Monticello included a wall that spun around to give dinner guests privacy, ventilated outhouses, a parquet floor, skylights, and the country’s first clock that kept track of the date with pendulums so long holes had to be drilled into the cellar with Revolutionary War cannonballs as their weights. Another pulley between the cellar and first floor allowed for enslaved workers to load full wine bottles and offload empties without entering the dining room. Like the University of Virginia, aka “Mr. Jefferson’s University,” for which this polymath designed the buildings and curriculum, hired the professors, ordered the books, and maneuvered it through the legislature during his retirement — all in the Enlightenment tradition of science, Classical design, republican politics and a dream that students would “drink of the cup of knowledge” — enslaved workers had an important role at Monticello but were purposefully kept out of sight as much as possible.

Jefferson’s Custom-Made Portable Writing Desk, Used in Philadelphia, 1776, Smithsonian Museum of American History

Unlike the Executive Mansion, Jefferson didn’t answer the door himself at Monticello. A servant let guests in and gave them time to gaze at an Entrance Hall full of maps, Native American artifacts, western fossils, and busts of Enlightenment philosophers. After guests had time to absorb this über man cave, the “Sage of Monticello,” as future president Franklin Roosevelt called Jefferson, came to greet them.

Outside, an overseer whipped enslaved wheat and tobacco field workers, while the barnyard area included a blacksmith’s forge, nailery, merino sheep, and woodworking shop. A panopticon in Monticello’s domed attic allowed Jefferson to spy on his workers from any angle. Those curious about James, John (carpenter), and Sally Hemings’ roles should consult Monticello’s link.

When Jefferson moved as president to the brand-new Federal City he’d also helped design, he transformed the ground floor of the Executive Mansion into another virtual museum of mounted animals and maps. According to unsubstantiated legend, when John Kennedy hosted a dinner for several Nobel Laureates in the 1960s, he remarked that it was the most brains that had been in the White House since Jefferson dined alone. Jefferson’s chief scientific interest as president was western exploration. He now had a chance to promote the agrarian republic he’d always favored over Hamilton’s mixed economy (previous chapter). That meant expansion, a topic that piqued Jefferson’s interest more than any Founder even though he never traveled west of the Appalachian Mountains.

When he served as Minister to France around the time the Montgolfier brothers invented the manned hot air balloon, his first impulse was to organize an expedition to fly from Siberia down the Alaskan coast to map western America. He maybe would’ve considered going in the other direction (west from Virginia), but he had a warped sense of how expansive the west was. Yet, like earlier Dutch and French explorers, he wondered if a Northwest Passage existed connecting eastern America to the Pacific by water. Living just at the dawn of evolutionary theory, he believed in the immutability (permanence) of species and theorized that the West was full of mastodons and other fossilized creatures never seen by Euro-Americans. After winning the 1800 presidential election, Jefferson arrived in office anxious to acquire and explore land beyond the Mississippi River and that became the centerpiece of his first term.

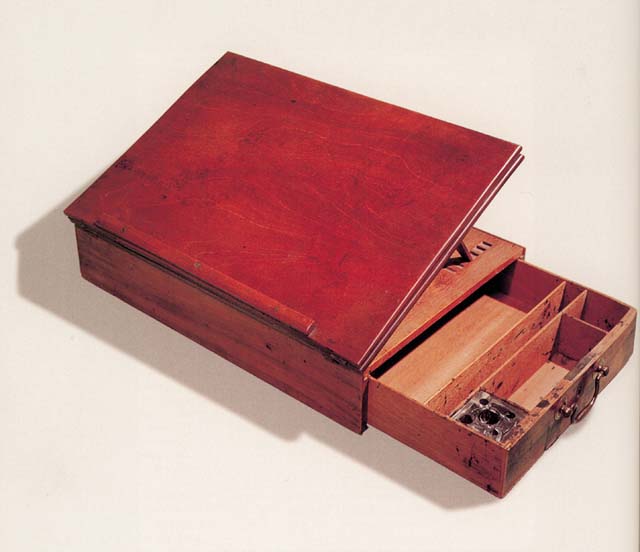

Hoisting of American Colors over Louisiana (Jackson Square, New Orleans), Thure de Thulstrup 1904 Depicting Events of 1804, Cabildo Museum

Louisiana Purchase

Jefferson saw French-held New Orleans as key to exporting American crops since it was near the mouth of the Mississippi and both the Ohio and Missouri River watersheds connected to the Atlantic via that route. He remarked in 1803, “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy . . . that spot is New Orleans.” Those were strong words from such a Francophile and supporter of the French Revolution as Jefferson since France owned New Orleans. French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte valued the area as a “wall of brass” that would hem in America’s western expansion (you could say that Aaron Burr and Napoleon had something in common). In 1803, Jefferson sent agents to France to negotiate either purchasing New Orleans or attaining free trading rights from Napoleon.

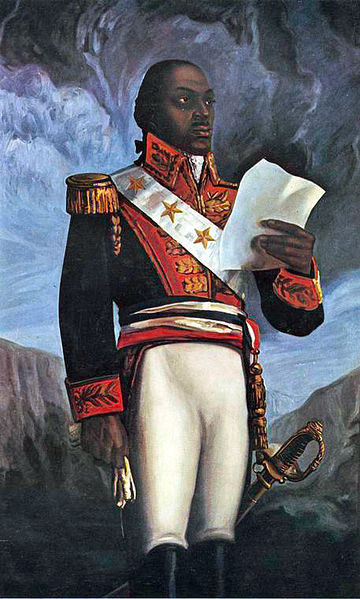

Napoleon’s main interest in America was growing crops to feed enslaved workers in the Caribbean, so with France having lost control of Saint-Domingue (then renamed Haiti) in a slave revolt led by Toussaint Louverture, Napoleon was willing to part with Louisiana. He’d sent 20k troops to quell the Haitian revolt, but many surrendered to yellow fever (mosquito-borne malaria). Napoleon was also skeptical about France’s ability to govern the area given its proximity to the growing U.S. population and America’s expansion. Oddly enough, Spain still governed the area even though France owned the land after 1800. With Haiti a lost cause, Napoleon opted to cut his losses in the Western Hemisphere altogether and focus on conquering Europe, Russia, and North Africa, unifying European states in the mold of the USA, all while fending off the British. Napoleon needed money to invade those areas. Since Congress could only afford Louisiana by borrowing from British banks, he figured that he would allow the U.S. time to repay the loans then conquer England and steal the money from their banks, thus being paid twice for the same transaction. According to legend, this devious scheme occurred to le petit caporal while he was bathing in the tub.

Jefferson’s men contacted Napoleon about New Orleans and, after not hearing back for weeks, were pleasantly surprised by a counter-offer of $15 million for the entire Louisiana Territory, the middle 1/3rd of the current Lower 48, in white on the map below encompassing the Missouri, Arkansas, and western Mississippi River valleys. The $15 billion was divided between land (11.25) and claims of U.S. citizens against France (3.75). Adjusted for inflation, this came to ~ $500 billion today, plus forgiveness of some French debts. American diplomats could barely grab the quill and ink fast enough and certainly didn’t have time to sail home and back to get formal permission from Congress. For 4¢/acre (ac), the Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the U.S. without a single shot fired, winning Americans the right to displace the region’s indigenous inhabitants. The area also included coal, gold, silver, lead and copper deposits. The president didn’t have authorization for such acquisitions, but Jefferson slid his strict constructionist constitutionalism under the rug this time and got away with it other than some bemused grumbling. It was hypocritical for sure, especially since the money used for the purchase was from Hamilton’s bond sales — that Jefferson also complained about as exceeding constitutional bounds — but it was too good to pass up. Ironically, the slaveholder Jefferson (and entire slaveholding South) had benefitted from the success of the Haitian slave revolt.

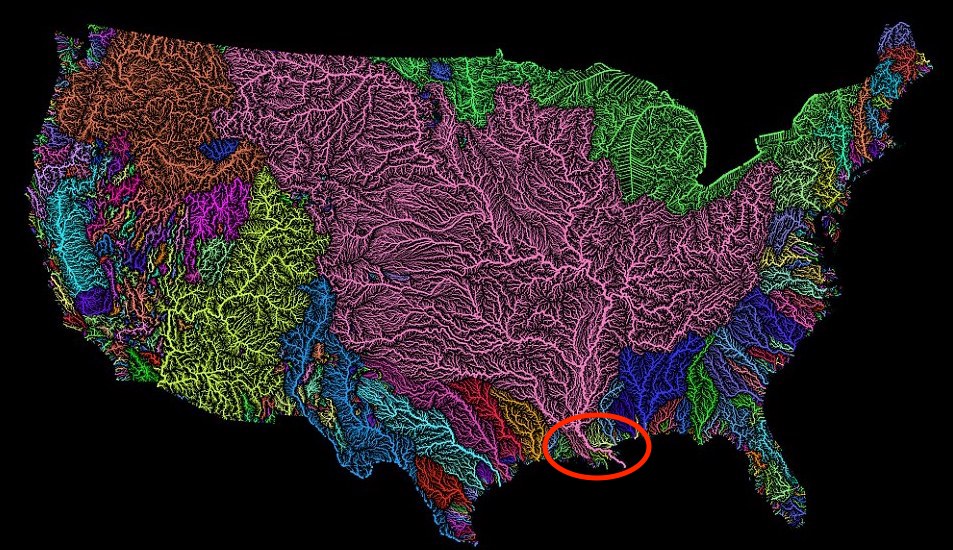

Like Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, Jefferson was an enemy of government spending who rang up an unusually large debt, though we should remind ourselves when assessing presidents that, ultimately, Congress controls budgets. At the time, there was some grumbling here and there, but no one in their right mind suggested that the Louisiana Purchase wasn’t a smart move from the American perspective. It was arguably the greatest swindle of all time given the fertile soil of the central U.S. and a price tag at 4¢ ac that would come to around $1.35 in today’s money (the average acre in Texas is now ~ $4k). The U.S. couldn’t really afford Louisiana, even at a bargain, but it could resell any land it acquired to its own citizens; that’s why there were no national income taxes until the 20th century (tariffs were the other source of revenue). During a big centennial celebration in St. Louis a century later to celebrate the Louisiana Purchase, Americans learned more about the now-famous Lewis & Clark Army exploration of Louisiana and the Oregon Country beyond. This color-coded map of connected U.S. river basins illustrates why Jefferson saw New Orleans as a key port for so much future commerce, and why he sent Lewis and Clark to learn more about western water routes:

Lewis & Clark Expedition

Jefferson was already planning to explore the new territory even before he struck the deal for the Louisiana Purchase. At the time, explorations mattered in intra-European debates as to who could lay claim to territory. And, even early in its history, the U.S. anticipated trading with Asia (namely China) as much as Europe, so it was interested in acquiring Pacific ports. Jefferson enlisted two trusted Virginia neighbors, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, to take crash courses in botany, zoology, and cartography from the Sage himself at the Executive Mansion. Lewis and Clark met each other in Washington’s army during the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s.

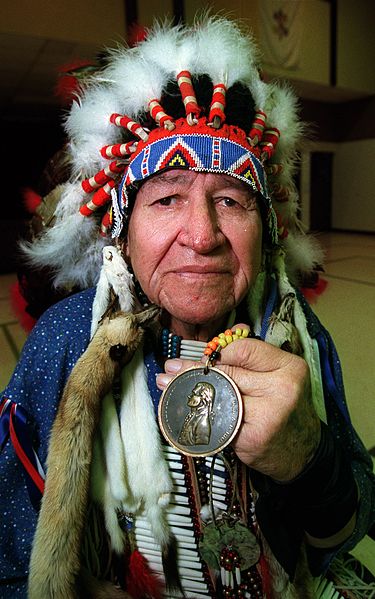

Lewis and Clark led the Corps of Discovery military expedition down the Ohio River, up the Mississippi to St. Louis, then up the Missouri River all the way to the Oregon Country from 1803-1805. Jefferson thought Oregon was too far away to ever become part of the U.S., but he hoped for a friendly alliance with whatever country Whites would someday settle there. He wanted to initiate friendly Indian relations along the entire route, instructing Lewis and Clark to drive a wedge between Indians and the Spanish who controlled the Southwest. Jefferson launched a similar Red River Expedition further south in 1806 to find the headwaters of the Arkansas and Red Rivers that the Spanish turned back with no shots fired, which is why you haven’t heard of its less famous leaders, Freeman and Custis. Lewis and Clark gave Native Americans coins called Peace Medals with Jefferson’s bust on one side and an ax and pipe on the other, symbolizing that their “new white father” represented trade and peace. We can only imagine what they thought of that condescending phrase if, indeed, it ever came through in translation.

As mentioned, Jefferson was also interested in finding a Northwest Passage whereby one could travel all the way to the Pacific by boat, the same route the French and Dutch searched for in vain centuries earlier. Lewis and Clark were to map the entire region and collect as many plant and animal specimens as possible, then schlep them home 2k miles to decorate Monticello’s man cave (entrance hall). They brought home a Mandan Buffalo Robe like the one below. Jefferson wanted them to investigate evidence of pre-Columbian Welsh contact among the Mandan, as well. He might have had ancestors from Wales himself, or maybe he was concerned about potential British claims on the West. It’s unclear what his motives were, exactly, in this letter to Lewis, other than to mention a map he’d mailed drawn by a man Jefferson believed the Spanish sent to investigate the Welsh mystery.

Despite the seeming goodwill of this first American foray into the Far West, Jefferson’s Indian policy wasn’t oriented toward long-term peaceful co-existence. He was fascinated with Native American culture from an anthropological perspective but also wanted them out of the way in order to clear the land for a future agricultural empire. While later American presidents, especially Andrew Jackson, are most famously associated with Indian removal (next chapter), the Founders initiated the policy. Both Jackson and Jefferson saw it as a more humane alternative than war, which it was, even if those two options weren’t the only alternatives. At first, Jefferson wanted to assimilate American Indians as a condition of allowing them to stay, forcing them to convert to Christianity (despite his own heterodoxy), develop written languages, stop hunting for a living, and start farming in straight rows. He suspected that since they would never comply, Whites could then take their land on those grounds — an assumption that proved false in the case of Cherokees and some other “Civilized Tribes.”

Later, Jefferson developed a covert strategy of indebting Indigenous Americans so that they would sell off land to repay their debts. Eventually, they’d be so surrounded by Whites that they’d leave of their own volition. He hoped that would “get rid of the pests, without giving offense.” In the meantime, “If we are constrained to raise the hatchet against any tribe, we will never lay it down until that tribe is exterminated, or driven beyond the Mississippi.” While he never advocated initiating preemptive war against Native Americans, and even wanted to “cultivate their love” during the removal process, dropping the “e” word (extermination) on an entire tribe is no small matter. Rather than associate Indian Removal purely with Jackson, Martin Van Buren, and the Trail of Tears, we should understand it as a policy the Founders started that continued through later presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, culminating in later wars and expulsions on the Great Plains and Southwest. Was their forced expulsion morally justified? Most people today would argue no, but neither is there a movement afoot among its critics to give the country back to the descendants of its original inhabitants. It’s common among today’s politicians to say we need to “take America back.” That must seem like an odd remark to American Indians, as their population dropped from 650k to 250k during the 19th century and far more than that from the 15th to 18th centuries.

The Lewis & Clark Expedition got critical assistance, though, from a Shoshone intermediary named Sacagawea, an updating of the familiar theme we’ve already seen with Cortès-Malinalli, John Smith-Pocahontas, and early Pilgrims-Tisquantum. She married Corps member Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader. While Sacagawea didn’t lead the expedition as depicted in legendary accounts, she and Charbonneau translated and helped the Corps of Discovery get horses, cross the Rockies and Bitterroots, and trade for more canoes as they dropped into the Snake and Columbia Rivers on the western slope. They called her “Janey,” Army slang for girl. Less famous Western Shoshones Old Toby (Swooping Eagle), Tetoharska, and Twisted Hair guided the Corps along their path. Sacagawea’s mere presence signaled that they came in peace since no Indian war party would tow along a young bride and mother. There was, as we learned in earlier chapters, no Northwest Passage that far south, just the mountainous Continental Divide that Lewis and Clark discovered, from which all rivers flowed into either the Pacific or Gulf of Mexico. Further north, Norwegian Roald Amundsen traversed the first passage from Greenland to Alaska in 1906. Like the French and Dutch before them, Americans learned much in their failed quest to find the Northwest Passage.

After wintering near the Oregon Coast, and long since having been given up for dead back east, the Corps divided upon their return route and made further discoveries in 1805-1806 (e.g. Pike’s Peak by Zebulon Pike) before returning to “Washington City” to top up Jefferson’s happy meter. The previously unknown prairie dog enamored the president and they multiplied in the yard of the Executive Mansion. Pike even returned a pair of grizzly bear cubs to Jefferson in 1807, who relocated them to Peale’s Museum in Philadelphia.

While pleased with his mementos, the hard-to-please Jefferson was disappointed that Lewis and Clark didn’t find the Northwest Passage and never hyped their trip. Only fourteen-hundred copies of their journal made it into print in 1814 and they weren’t famous. Future settlers into the Oregon Country didn’t follow their indirect route. Lewis and Clark didn’t gain traction until the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, whose promoters drew attention to the journey’s centennial as a way to underscore their city’s connection to the Louisiana Purchase. Sacagawea came to the Corps of Discovery’s aid once again by appearing in Suffragist Eva Emery Dye’s exaggerated biography of 1902, published in anticipation of the St. Louis expo.

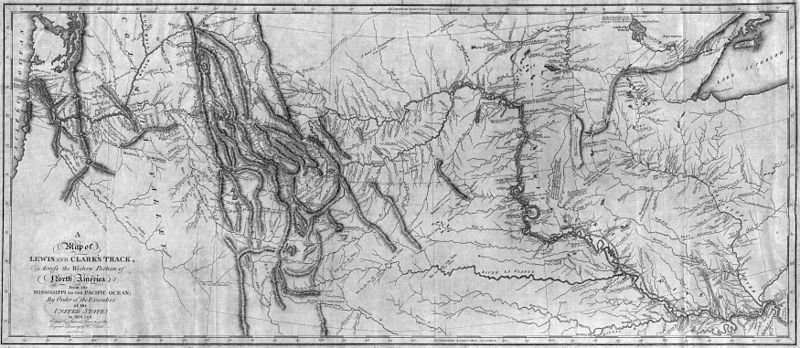

A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track, Across the Western Portion of North America From the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean, Copied by Samuel Lewis From the Original Drawing of William Clark, 1814

Today, campers and hikers can still explore the Lewis & Clark trail. The route is well known, partly because of the quality of the original maps (above) and partly because the Corps unwittingly left mercury deposits wherever they went for future archaeologists to discover. At the instruction of Philadelphia doctor Benjamin Rush, a friend of Jefferson’s and signer of the Declaration, they packed medicinal wine and Turkish opium to calm their nerves, and emetics to induce vomiting. They also took along 50% mercury tablets called Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pills (aka “thunder clappers”) to combat ailments on the theory that one should combat poison with poison. Since the body discharges poison, mercury deposits still mark where the Corps dug latrines. Other than one crew member that died of appendicitis, and despite a few hair-raising scuffles with grizzly bears and tense encounters with Native Americans, there were few casualties on the expedition (a wolf bit Clark’s hand in his sleep). Naturalist John Muir later wrote that they could’ve scarcely been more fortunate if they’d stayed home.

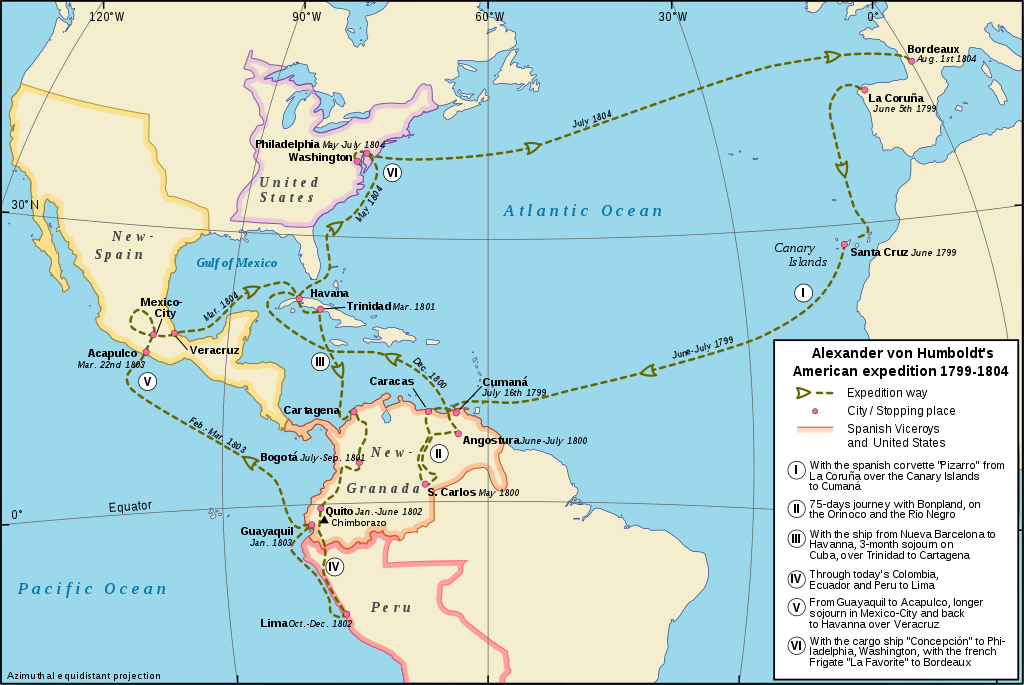

If Lewis and Clark couldn’t completely top up his happy meter, it was because of Jefferson’s insatiable curiosity and his ambition to draw Europeans’ attention to the Americas. Prussian scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt visited Jefferson in Washington during the Lewis & Clark expedition as part of his Latin American tour (below). Humboldt raised Jefferson’s standards as to the quality of data he now expected from animal and plant specimens and cartography and Humboldt’s was a hard act to follow.

One event right up Jefferson and Humboldt’s alley was excavation of what they initially thought was a woolly mammoth but really a mastodon outside Montgomery, New York in 1801, the remains of which contributed to, but didn’t fully constitute, the world’s first articulated prehistoric skeleton — assembled by the artist of the event’s painting below, Charles Willson Peale, an Enlightenment polymath on par with Jefferson and Humboldt.

Jefferson lived just at the dawn of evolutionary theory and assumed that any fossils they found were of animals still roaming the west. He sent the bones to Europe to prove the animals’ existence but they didn’t make as much of a splash as he hoped. Leaders instead chose Niagara Falls, New York and Natural Bridge, Virginia as more promising national symbols/monuments than the mastodon skeleton. You can see an early mash-up of Niagara and Natural Bridge in the bottom left-hand corner of Henry Schenck Tanner’s 1825 map of the United States:

Barbary & Napoleonic Wars

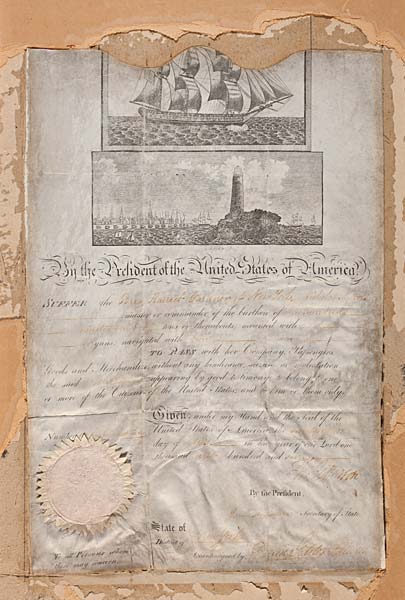

Western expansion made Jefferson’s first term successful but, like many presidents, his second term didn’t go as well. This stands to reason because, without at least a moderately successful first, there is no second. Jefferson’s Achilles’ heel was foreign policy, where he failed to steer the U.S. clear of European entanglements. At first, his focus was on North Africa, defending America’s Mediterranean shipping against Muslim pirates in the Barbary Wars. Jefferson wasn’t opposed to Islam — and famously wrote that Muslims, along with Christians, Jews, and Hindus, should be afforded full religious freedom within America — he just opposed American shipping being exploited by pirates who happened to be Muslim. When Jefferson came into office in 1801, the U.S. was spending 20% of its entire national budget paying ransom to the Barbary Pirates. The British had protected colonial Americans’ shipping, but now the U.S. was on its own without a significant navy or familiar flag and the Brits watched, bemused, as Americans struggled with piracy. At their root, governments and militaries are more elaborate versions of protection rackets. When gangsters offer protection to neighborhood businesses, what they really mean is give us money or we’ll destroy your business because, in truth, the “protection” they’re offering is really mostly from them. The upside is that gangsters will also protect the business from rivals because it’s their turf and they don’t want their income disrupted. Likewise, governments levy taxes in exchange for military protection. Since American merchants weren’t yet paying enough for their own legal protection, they had to pay ransom to conduct business overseas. This “passport” was typical of those signed by early presidents to send along with merchant vessels, who paid fees to collectors with scalloped receipts to match the top portion.

Ships Passport Signed By President Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison, ca. 1801-09, history.org

The area had been notorious for a long time, with Jihadists terrorizing the Christian Mediterranean since the 16th century in revenge for the Moorish expulsion from Iberia in 1492 (Chapter 3). Historians estimate that over a million European Christians were enslaved and sent to North Africa between 1530 and 1800, perhaps ~ 8% as many as enslaved Africans sent to the New World. The fledgling U.S. Navy fought there on and off for fifteen years before merchant vessels were able to stop paying tribute by 1815. Echoes of those battles are still heard in the Marines’ Hymn, with its “shores of Tripoli.”

Burning of USS Philadelphia in Tripoli Harbor (1804), Edward Moran, 1896, Naval History & Heritage Command

But Jefferson hoped to avoid more expensive and dangerous European conflicts. To be fair, George Washington had naively hoped America could avoid European entanglements as well, but it wasn’t to be. Jefferson’s policy of maintaining a small military and relying on agricultural exports to leverage American power came back to haunt him in his second term. He mistakenly figured that embargoing American produce would be enough to keep others in line, buying into Thomas Paine’s reasoning that “Europe will need America as long as Europe needs to eat.” The flaw in their theory was that Europeans didn’t need American imports as much as Americans needed exports. There were plenty of farms in Europe, after all. Instead, whenever France and Britain clashed, both sides sank American ships headed for the other country. The same dynamic drew America into World War I a century later, except in that case it was France and Britain on the same side opposing Germany.

In this case, the Napoleonic Wars were the culprit, as the British and French navies took turns on American merchants, just as they had in the 1790s. The U.S. had the Mosquito Fleet, so-called due to its small size, but nothing big enough to confront either navy if those navies were at full force. In a series of wars that eventually killed 3.5 million soldiers, Napoleon was trying to unite all of Europe in an economic alliance arrayed against the British Empire and didn’t want America trading with Britain. Britain naturally didn’t want America trading with continental Europe and felt betrayed that their “cousins” across the pond would even consider such a thing.

Jefferson’s response was consistent with the policy he’d laid out. He cut off American exports to Britain and Europe to punish the offending belligerents. But such executive privilege was entirely inconsistent with his strict constructionist constitutionalism. The executive branch didn’t have the right to intervene in the economy in such a fundamental way, at least according to the way Jefferson interpreted the Constitution before he was in the executive branch himself. In fact, the president didn’t have the right to slap an embargo on the entire American export economy according to anyone’s reading of the Constitution, strict or loose. On this score, Jefferson’s presidency was a good example of the proverb, Where you stand is a matter of where you sit.

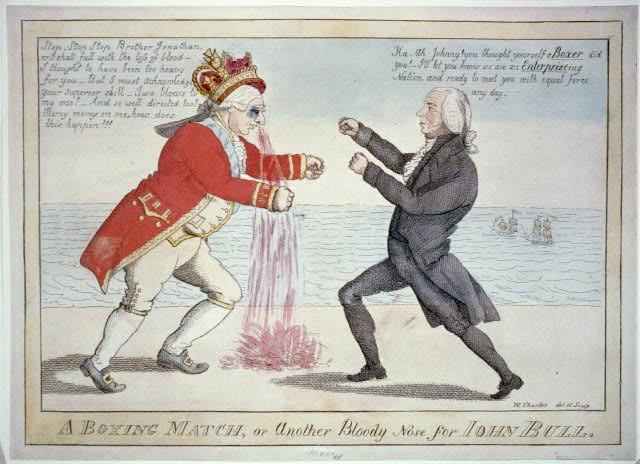

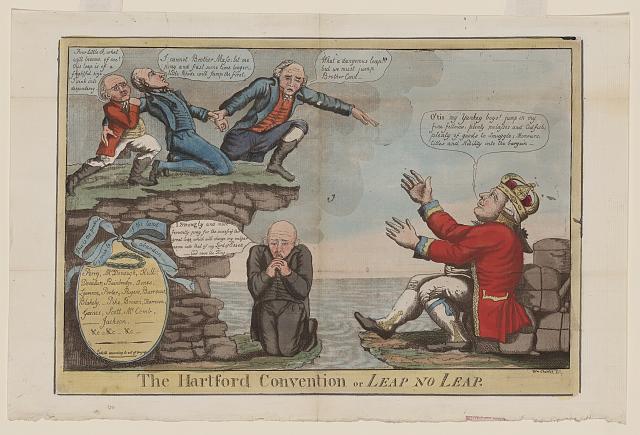

The bigger problem, though, was practical rather than constitutional. An embargo was what King George III had done to punish America with the Prohibitory Act of 1775. Your author even referred to George’s action in Chapter 8 as “economic warfare.” To say coastal merchants were displeased with this “dambargo” would be to understate the case (enlarge cartoon). Prices of normally exported goods plummeted more in the U.S. than they rose in France or Britain, victimizing Americans. The small-government advocate Jefferson even used U.S. gunboats to interdict New England smugglers, which they viewed as a spiteful move from a Southern farmer and, again, echoed the run-up to the American Revolution.

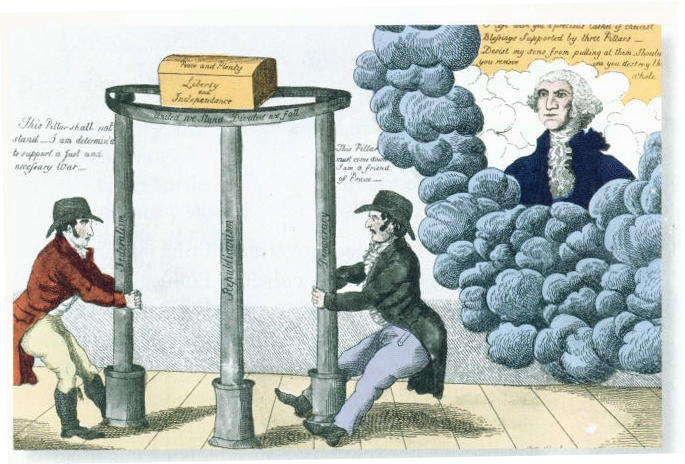

This crisis was regionally divisive in a country just starting to unify. We naturally think of the Southern Confederacy in 1860-61 when we think of secession because they followed through; but the first group to consider seceding from the U.S. was, arguably, the Democratic-Republicans in the 1790s (nullification at least had secessionist implications), and the second was northeastern Federalists during the embargo and ensuing war. At their 1814-15 Hartford Convention, the inheritors of Alexander Hamilton’s platform discussed whether they would be better off economically rejoining the British Empire, though most opposed the move. Federalist presses raked Jefferson over the coals mercilessly, making him relieved that Washington had established a two-term tradition if, indeed, he could’ve been re-elected as president for a third term. Jefferson served out his second term and retreated to his sanctuary at Monticello, hoping that incoming president James Madison could sort out the problems.

War of 1812

He couldn’t. Madison limited the embargo to just Britain and France, rather than all of Europe, and it started to have some effect, but still not enough. Meantime, American smugglers started getting flak from across the Atlantic. Many British merchants had been willing to look the other way as American runners undercut their business because they held U.S. Treasury notes (bonds) and illicit trade indirectly helped ensure the health of the U.S. National Bank. But by 1811, those notes were paid off. With no stake in America, they pressed Parliament to defend Britain’s mercantilist shipping interests.

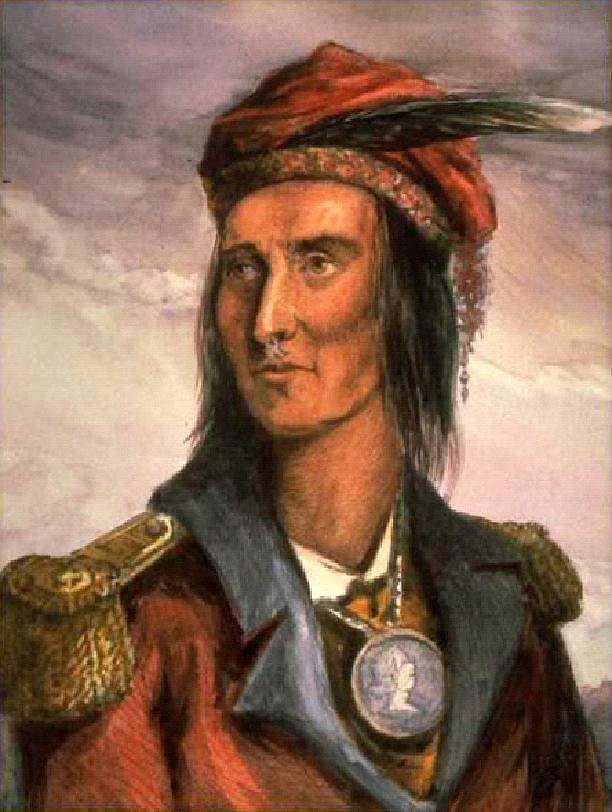

The larger truth was that the U.S. had never really gotten out from under the British thumb. Despite agreements to the contrary in 1783 ending the Revolution and the Jay Treaty of 1795, Redcoats remained in western forts where they forged Native American alliances to block American settlers. In 1811, Americans led by William Henry Harrison destroyed the village of Prophetstown in the Battle of Tippecanoe in Indiana Territory, motivating Shawnee leaders Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa to seek an alliance with the British. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy kidnapped American sailors in the Atlantic and impressed around 8k into service. The British claimed the captives were deserters they were returning to service, which was often the case since sailors could make more money on American merchant ships.

These simultaneous humiliations on the frontier and Atlantic were more than the War Hawks in Congress could bear, and Britain compounded friction with southern plantation owners by disrupting, and threatening to further disrupt, what remained of the Atlantic slave trade (in theory, illegal anyway after 1808). The Hawks convinced President Madison that it was time for a Second War for Independence. New England bankers and merchants didn’t support the war but enough Southerners and Westerners did to get the declaration through Congress. The British had bigger fish to fry while fighting Napoleon, so they agreed to all the American demands, revoking their 1807 Orders in Council of warfare against anyone violating their boycott of France. But this was the most notorious case ever of communication lag across the Atlantic causing problems. Word of the Anglo-American truce didn’t make it back across the Atlantic in time to prevent war from breaking out: the War of 1812 that lasted from 1812 to 1815. When Madison heard that the British revoked the Orders in Council, he changed the terms of the war to include the impressment of sailors even though the British had also agreed to stop taking sailors. They’d even ordered their commander of the North American naval station to negotiate a settlement. The war drums were beating so loud in Congress that it was too late for the president to stop what was already in motion. For one thing, this would be a good pretext to conquer Canada.

Off the record, British politicians agreed that they could do without the forts of the Old Northwest or kidnapping American sailors, so they were not too concerned with the Americans as long as they didn’t try to take Canada. But, as in 1775, the U.S. tried to do just that in 1812. A British-backed Native American confederacy led by Shawnee chief Tecumseh blocked their first try, causing the U.S. to temporarily cede the Michigan Territory after they lost Fort Detroit. Detroit fell so easily that the Army court-martialed the commanding general, William Hull, and President Madison only spared him from execution because he’d been a hero in the Revolutionary War. Two other invasions, at Niagara and Montreal, failed, with some American militia refusing to cross the border into Canada. The only morale booster for Americans was a series of upset frigate victories by the outnumbered Navy in the Atlantic against the vaunted Royal Navy. The most famous of these ships, the wooden-hulled, three-masted USS Constitution, earned the nickname “Old Ironsides” by withstanding British cannonballs.

The following year, in its 1813 Great Lakes campaign, the U.S. burned the Upper Canadian capital of York, later rebuilt as Toronto. The retired Jefferson remarked that seizing Canada and laying claim to all of North America would only be a “matter of marching,” but the campaign ultimately failed despite numerous incursions and victories along the way. Still, the U.S. built and sailed ships impressively well in the Great Lakes, winning all six single-ship actions in the Battle of Lake Erie and helping to secure future control of what became the Midwest. After being rowed under fire from the burning USS Lawrence to the USS Niagara and leading his sailors to victory, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry famously dispatched the message: “We have seen the enemy, and they are ours; two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop.” Perry’s naval victory helped convince the British to settle for an ambiguous peace a year later.

But north of the 49° parallel, the United States’ failure to “lay their axe to the root” of British North America emboldened a sense of identity among Canadians that later led to nationhood and virtual independence from Britain within the Commonwealth. Repelling the 1813 American invasion was the first time that French-, Scottish-, German- and British-Canadians united in a common cause. Many Canadians had emigrated from the U.S. to take advantage of land grants and were sympathetic to the U.S. cause prior to the burning of York and Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario). At the time, Christian nations could be brutal toward what they perceived as savages but generally didn’t attack each other’s civilians. This was an exception. The winter of 1813-14 was especially tragic along the Niagara River since many neighbors worked and worshiped with people across the border. Undisciplined troops razing and burning Canadian towns in the heart of winter, sending people out to die in the cold, led to a series of reprisals in American towns like Buffalo, New York. One soldier reported seeing hogs feeding on the dead bodies of American refugees from burned towns. In retrospect, it’s more likely that Canada would have become part of the U.S. without the American invasion.

Then the Napoleonic Wars ended, something the War Hawks never anticipated. In the Battle of Waterloo, Belgium, the British defeated Napoleon, leading to the phrase “met his Waterloo” (and to the city of Austin’s original name). Without Napoleon to worry about, the British could send a full force of battalions and frigates to America to battle the American Navy and choke off its export economy. They blockaded New York and Philadelphia, dropping annual export profits from $40 to 2.5 million. And since the Democratic-Republicans didn’t renew the National Bank when its first charter expired in 1811, the U.S. had no way to raise money for troops. It always pays to think through contingencies in warfare and the anti-bank party of Jefferson and Madison had left themselves vulnerable by attacking Canada while cutting off their own source of funding. Hamilton must’ve been rolling over in his grave. In the two countries’ bloodiest-ever land battle (1700 casualties), Redcoats repulsed the Americans’ last assault on Canada at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane outside Niagara Falls, Ontario. Southeast of there, New York Harbor was well fortified with batteries at Governors Island, but the Royal Navy blockaded New York and Philadelphia and the U.S. had no other defense to speak of on the East Coast besides a smattering of militias.

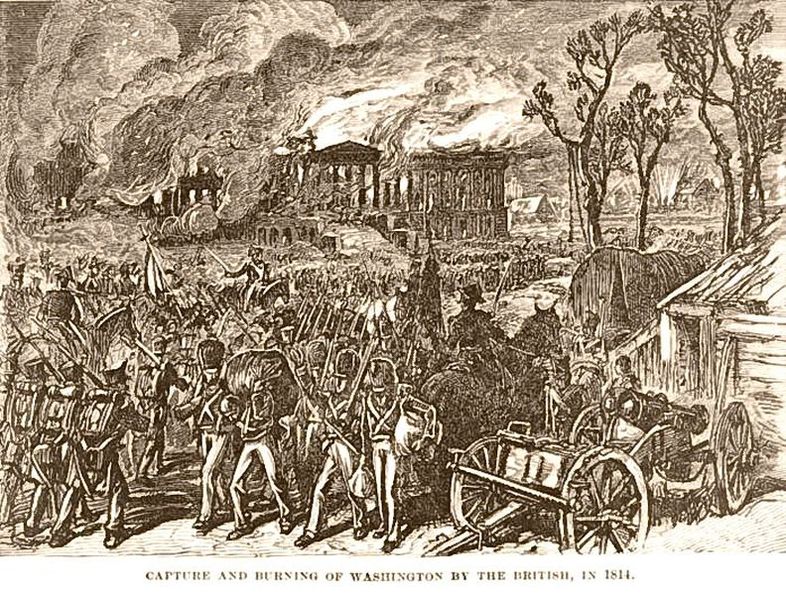

In 1814, the British sailed into the Chesapeake Bay, marched right into Washington and razed the U.S. capital, including the Capitol, outnumbering defending forces 5k to 500. A few regulars and militia tried to confront the Redcoats six miles outside of Washington at Bladensburg, Maryland but fled in the face of British Congreve Rockets (early small missiles). Their capitulation in the “Bladensburg Races” has been called the greatest disgrace in American military history. However, the few there fought valiantly enough that the British didn’t burn the Marine barracks in Washington out of respect; it was the only building left standing. In truth, the blame lay not with the military, most of which was in Canada, but with the President, Congress, and Secretary of War John Armstrong, Jr., who were negligent in assuming that the British would never attack the capital. They didn’t realize that Redcoats wanted to deal Yankees a crushing and symbolic blow from which they’d never rise again to challenge their authority. It wasn’t customary for civilized countries to destroy each other’s capitals, but the British thought their Americans “cousins” had stabbed them in the back for no reason while they were fighting Napoleon, and fighting Napoleon should’ve been everybody’s fight.

Portrait of Dolley Madison, First Lady of the United States, ca. 1873 or Earlier, Artist Unknown, University of Texas

President Madison and his wife, Dolley, fled the city on horseback, though she heroically returned with enslaved workers to rescue the country’s most cherished heirloom, Gilbert Stuart’s life-size portrait of George Washington. Had Dolley been captured, the British likely would’ve paraded her through the streets of London in a cage. The wine was poured and meat still on the spit when Redcoats arrived in the Executive Mansion. They finished off the First Couple’s dinner and emptied their wine cellar, toasting “Lil’ Jimmy” (Madison) before torching the Executive Mansion.

It wasn’t the finest hour in the history of the American presidency or the nation’s history. Worse, with the National Bank gone and import tariffs drying up, American coffers were empty. Oceanic trade plummeted from $40 million in 1811 (much of it illegal) to $2.6 million in 1814. Thirty-eight years after its inception, the U.S. was bankrupt with a razed capital and its president (Madison) fleeing the British on horseback, likely watching the conflagration from a distance and wondering what he’d created back in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention.

Some interpreters consider it divine intervention that a tornado hit Washington during the invasion but, if so, it came too late to save the key buildings and caused collateral damage, killing some Americans. At least the thunderstorm from which the tornado emerged put out the fires. Either way, the British had had enough and they proceeded up the Chesapeake to Baltimore, where they planned to rout America’s own pirate nest. Unlike Washington, a tiny “sheep’s pasture” of 8k people at the time, Baltimore was a major port and shipbuilding center.

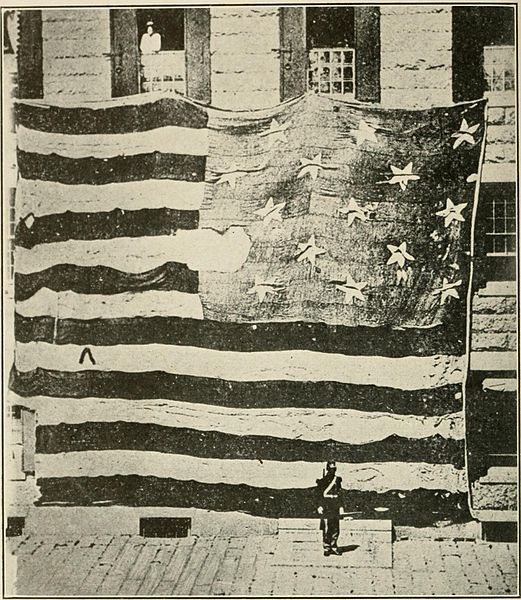

Flag That Floated Over Fort McHenry in 1814 the Night Francis Scott Key Penned Lyrics to the Star-Spangled Banner

Americans had better luck in Baltimore. Merchants and pirates scuttled their ships at the harbor’s entrance to block the British fleet. The British would’ve destroyed their ships anyway had they entered the harbor. Given that choice, it was smarter to sink the ships and block their path to save the city. As the British bombed Fort McHenry, at the harbor’s entrance, American POW Francis Scott Key wrote a poem entitled the “Defense of Fort McHenry.” It became the Star-Spangled Banner when put to the tune of the British song “To Anacreon in Heaven,” and the U.S. anthem during World War I, officially in 1931. During World War II, the tradition began of playing the anthem before baseball games, later adopted to other sports. Meanwhile, a myth emerged that repainting/whitewashing the foundation of the burnt Executive Mansion (formerly called the “executive’s palace”) led to the term White House. No one really knows when the term came into common usage, but it no doubt had to do with its light-colored edifice and was officially so named by Teddy Roosevelt in 1901.

Further west, the war was less lopsided. Like the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 intensified ongoing warfare between Native Americans and Euro-Americans along the frontier, in this case partly because one of the war’s causes was British aid to tribes in the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes. There was also conflict in the Southeast with Creeks and Cherokees, as white planters began to scoop up more cotton-growing land, some of which Native Americans occupied per. However, the British and Americans agreed that with the Napoleonic Wars over the root cause of their disagreement in the Atlantic had resolved itself. As long as the British held Canada, they weren’t overly concerned with staying in the Ohio Valley, where Americans were gaining population and momentum anyway.

At first, when they thought they’d won the war outright after their conquest of Washington, D.C., the Brits planned to negotiate a buffer state for Indians between the U.S. and Canada in the Ohio Valley and basically put an end to America’s western expansion in the north. But the defense of Baltimore and a key late American naval victory on Lake Champlain, the Battle of Plattsburgh Bay, weakened their hand, and they abandoned their indigenous allies. They would leave it to American settlers and Native Americans to fight over the Midwest and Great Lakes on their own. Interest in the war was evaporating in England anyway, and Prime Minister Lord Liverpool wanted to wind things down quickly. The Treaty of Ghent (Belgium) ended the American-British part of the Napoleonic War. The Ghent truce mostly restored things to the way they’d been before the war between the countries, status quo ante bellum. But just as word of the original truce never crossed the Atlantic on time, one of the war’s major battles happened after the peace treaty was signed. The whole affair might never have occurred if only the Doldrums were windier or the trans-Atlantic telegraph had been laid seventy years prior. However, neither side had formally ratified the treaty.

As the ink was drying on the un-ratified treaty in Ghent, British troops were already launching an invasion of the Lower Mississippi Valley. A ragtag collection of farmers and militia, some free and some enslaved, outnumbered 3:1 and led by Tennessean Andrew Jackson, stopped the Redcoats cold in their tracks at New Orleans. Jackson enlisted aid from local pirates Pierre and Jean Lafitte (“Hellish banditti” he called them), who were granted presidential pardons and later established a pirate colony on Galveston Island. In the biggest unaided American victory to date (the French helped at Saratoga & Yorktown during the Revolution), Jackson’s men built a massive mud berm around the city and cut down 2k Redcoats while suffering only 62 casualties, blunting the Brits’ Mississippi campaign. The entire “Rednecks vs. Redcoats” battle lasted just twenty-five minutes.

In accomplishing what the defenders of Washington, D.C. had failed, the defenders of New Orleans arguably helped save the nation. Federalist Timothy Pickering, leader of the secessionist faction, said that if the British took New Orleans, he’d “consider the Union as severed.” Regardless of the mix-up on timing and communication, Americans of the time interpreted the Battle of New Orleans as having won the war. While technically the treaty had already been signed two weeks earlier, the British may have occupied the area had they won but, instead, the stupendous victory ended the war in upbeat fashion for Americans. Jackson parlayed his fame into a successful military and political career, culminating in a two-term presidency (next chapter). For many years, Americans celebrated the anniversary of the New Orleans battle, helping to keep the focus on Jackson.

Conclusion

After the patriotic upsurge at the end of the war, the Federalists who had considered secession found themselves in an embarrassing situation. Even though secessionists represented only a minority of Federalists, the party didn’t survive the war. The National Republicans and Whigs revived their pro-business platform later but, by now, all white men could vote so the revamped versions had no choice but to embrace democracy. But there were still plenty of business issues to discuss. Contrary to Jefferson’s original goal of keeping the U.S. economy focused on farming, his embargo and the War of 1812 forced American merchants to become more self-sufficient. Consequently, the apostle of agrarianism ironically accelerated the Industrial Revolution on American shores. Jefferson also helped import the concept of interchangeable parts from France, a key aspect of the Industrial Revolution (Chapter 14). Jefferson didn’t help his own cause much if his goal was to keep industry out of the U.S.

Another underrated impact of the embargo and war was that it motivated New England merchants to seek markets in the Pacific Basin. New England merchants sailed around South America, traded and hunted for sea-otter furs in the Pacific Northwest, swapped guns and iron tools to Hawaiians for pork, salt, freshwater, and sandalwood, then traded sandalwood and sea-otter furs to China for porcelain, silk, and tea. It’s possible that without gaining this foothold, capitalized on shortly thereafter by New England missionaries who settled in Hawaii around 1820, America would’ve ceded the central Pacific to Britain, Japan, or Russia.

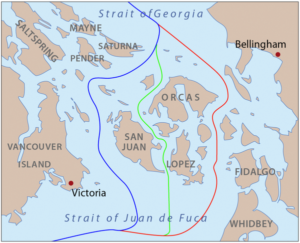

As for the upper portion of North America, the U.S. hasn’t invaded Canada since and, after Canada gained independence within the United Kingdom in 1867, the line separating the two countries became the longest undefended border in the world. Historians tend to discourage counterfactual theories (“what might have been” or “what if…”), but it’s not too difficult in this case to imagine Canada as part of the U.S. if the invasion had gone well, or the upper Midwest as part of Canada if the Great Lakes Naval campaign had gone worse. It’s more difficult to imagine a lasting Indian buffer state had the British won late in Baltimore and on Lake Champlain. One of the lasting effects of the much-maligned War of 1812 was that it precluded future wars between Americans and British over the west. Aside from a dispute over the Oregon Country thirty years later, and minor spats over the borders of Maine, Minnesota, and the San Juan Islands in Puget Sound (the Pig War, right), all resolved diplomatically, the two countries peacefully divided the continent along the 49º parallel.

As for the upper portion of North America, the U.S. hasn’t invaded Canada since and, after Canada gained independence within the United Kingdom in 1867, the line separating the two countries became the longest undefended border in the world. Historians tend to discourage counterfactual theories (“what might have been” or “what if…”), but it’s not too difficult in this case to imagine Canada as part of the U.S. if the invasion had gone well, or the upper Midwest as part of Canada if the Great Lakes Naval campaign had gone worse. It’s more difficult to imagine a lasting Indian buffer state had the British won late in Baltimore and on Lake Champlain. One of the lasting effects of the much-maligned War of 1812 was that it precluded future wars between Americans and British over the west. Aside from a dispute over the Oregon Country thirty years later, and minor spats over the borders of Maine, Minnesota, and the San Juan Islands in Puget Sound (the Pig War, right), all resolved diplomatically, the two countries peacefully divided the continent along the 49º parallel.

America had won its 2nd War for Independence, Britain had contained a side skirmish while defeating Napoleon, Canada was on its way toward nationhood, and the indigenous people of the Midwest faced nearly inevitable defeat in the face of American expansion. Unlike the Imperial Wars (including the French & Indian War), the Revolutionary War, and War of 1812, there were no longer two competing groups of Whites enlisting Native Americans to fight for them.

Optional Reading, Viewing & Listening:

Monticello Explorer (Virtual Tour)

Journals of Lewis & Clark (Univ. of Nebraska)

Jefferson’s Letter to the Danbury Baptists, January 1st, 1802

Jefferson’s Blood, PBS Frontline

Jefferson’s Hints to Americans Travelling [sic] to Europe (Founders Online)

PODCAST (27:16): Armenta, Thorson & Wollerton, “Benjamin Banneker Challenges Thomas Jefferson” (Monticello)

Peter Charles Hoffer, “Why Burr’s Conspiracy Trial Is Relevant Today,” History News Network

Backstory, “War of 1812: Which One Was That?” (52:02, Virginia Foundation for the Humanities)

[Jefferson’s] American Indian Policy; A Conversation With David Wilkins (Lumbee Nation), Monticello

Jefferson’s Recommended Reading (John Uebersax)

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an (Denise Spellberg)

“America on Fire,” Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine (July-August 2014)

Securing the Republic, 1801-1829, Department of State, Office of the Historian