Washington On His Way Toward Presidential Inauguration @ Federal Hall in NYC, 1936 WPA Wallpaper @ John Brown House, Providence, RI, Photo By Author

The first decade after the Constitution kicked in was more tumultuous than modern Americans realize. The Early Republic of the 1790s verged on collapse or even civil war as it faced internal rebellion and challenging policy questions over diplomacy, slavery, sectionalism, Indian wars, and economics (trade, taxation, and debt). How powerful would the new national government really be in relation to the states? Would it be a true nation or more of a coalition of smaller state republics? How would it defend itself militarily? How would the U.S. cope with European wars and revolutions? Could the republic sustain peaceful transitions of power between rival factions amidst backstabbing and partisan skulduggery? How strongly, with words or weapons, could Americans protest against their own government?

The new national government confronting these questions started in New York (painting above), then moved to Philadelphia for most of the decade before relocating to Washington, D.C. in 1800. Congress met in a courthouse adjacent to Independence Hall, then still Pennsylvania’s statehouse, while George Washington lived at the President’s House on Philadelphia’s Market Street (right). Washington was the only president voted into office without campaigning. He cultivated an image based on Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who virtuously returned to Rome for a second stint as emperor in 439 BCE after having retired to his farm. Washington, likewise, had “laid down his sword” after the Revolutionary War, only to be (reluctantly?) beckoned back into the messy game of politics. His first term began in 1789 and his second in 1792, in order to get future elections set on even years.

The new national government confronting these questions started in New York (painting above), then moved to Philadelphia for most of the decade before relocating to Washington, D.C. in 1800. Congress met in a courthouse adjacent to Independence Hall, then still Pennsylvania’s statehouse, while George Washington lived at the President’s House on Philadelphia’s Market Street (right). Washington was the only president voted into office without campaigning. He cultivated an image based on Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who virtuously returned to Rome for a second stint as emperor in 439 BCE after having retired to his farm. Washington, likewise, had “laid down his sword” after the Revolutionary War, only to be (reluctantly?) beckoned back into the messy game of politics. His first term began in 1789 and his second in 1792, in order to get future elections set on even years.

The Constitution doesn’t flesh out the president’s administration clearly in Article II but gave Congress the power to create officers for presidents to delegate power to. In the 1790s, Congress established the departments of State, Treasury, War (now Defense), and Post Office (later dropped), but there are now twenty-two. Historian Lindsay Chervinksy argues that the small, cramped room that Washington’s first department heads met in led to the term cabinet and contributed to its contentious, partisan nature. Washington didn’t form his cabinet until two years into his administration, indicating that department heads like Secretary of State and Treasury weren’t in the Founders’ original plans. Since Congress doesn’t administer or enforce laws or policies on their own, they ended up creating more and more agencies in the 20th and 21st centuries under the executive branch, swinging power over to the presidency. Unelected agencies pass more rules than Congress does laws and the president has control over appointing the agency heads (the Cabinet). Yet, Congress created and maintains oversight over all these agencies. For example, the Justice Department is accountable to the House Judiciary Committee.

The Constitution doesn’t flesh out the president’s administration clearly in Article II but gave Congress the power to create officers for presidents to delegate power to. In the 1790s, Congress established the departments of State, Treasury, War (now Defense), and Post Office (later dropped), but there are now twenty-two. Historian Lindsay Chervinksy argues that the small, cramped room that Washington’s first department heads met in led to the term cabinet and contributed to its contentious, partisan nature. Washington didn’t form his cabinet until two years into his administration, indicating that department heads like Secretary of State and Treasury weren’t in the Founders’ original plans. Since Congress doesn’t administer or enforce laws or policies on their own, they ended up creating more and more agencies in the 20th and 21st centuries under the executive branch, swinging power over to the presidency. Unelected agencies pass more rules than Congress does laws and the president has control over appointing the agency heads (the Cabinet). Yet, Congress created and maintains oversight over all these agencies. For example, the Justice Department is accountable to the House Judiciary Committee.

With the Judiciary Act (1789), the First Congress and Washington also established an attorney general under which the Justice Department emerged in 1870 to fight the Ku Klux Klan and the FBI started in 1908 to track anarchists of the sort that assassinated William McKinley in 1901. Founder George Mason noticed a problem with the Justice Department being housed under the president: “The President of the United States has the unrestrained power of granting pardon for treason; which may be sometimes exercised to screen from punishment those whom he had secretly instigated to commit the crime, and thereby prevent a discovery of his own guilt (Objections to the Constitution).” Mason was prescient as modern presidents Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump tried to fend off investigations by their own Justice Departments, raising thorny questions over executive privilege and checks-and-balances within a single branch. In theory, the “JD” is independent of the president, even though it is housed in the executive branch. The highest-presiding law officer in the United States is the Attorney General.

Washington was initially more “hands-off” than are modern presidents, insofar as he did not see it as his place to lead with particular policies or platforms. As Madison explained in the Federalist Papers, the Constitution’s framers intentionally created a relatively weak executive branch to avoid an overbearing king-like leader. At first, Washington just expected to oversee a congress that would lead and get along without bickering. However, the presidency and national government as a whole strengthened during the Federalist Era of the 1790s. Washington’s cabinet members were the policy wonks who set the agenda, though, more than the president himself, as we’ll see below. It’s safe to say that the framers likely underestimated the power of the president’s cabinet.

Washington assumed greater executive power as he went along and even usurped his constitutional power by spending money and forming his own militia without Congressional approval. He arguably had no right to invade Pennsylvania with federal forces during the Whiskey Rebellion (about which more below) without permission from that state’s governor, per Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution. And he had no right to declare neutrality in the war between France and Britain, as declaring war and neutrality is Congress’s prerogative. These actions set a precedent for a stronger executive branch in the future than was likely intended. Washington wasn’t averse to confrontation and had long since established his alpha male credibility during the Revolutionary War, but he found the day-to-day squabbling of politics irritating. He was among those Founders who deplored political parties and hoped they would never make their way to American shores. Yet, Washington and the country as a whole soon discovered that factionalism is inherent in republicanism.

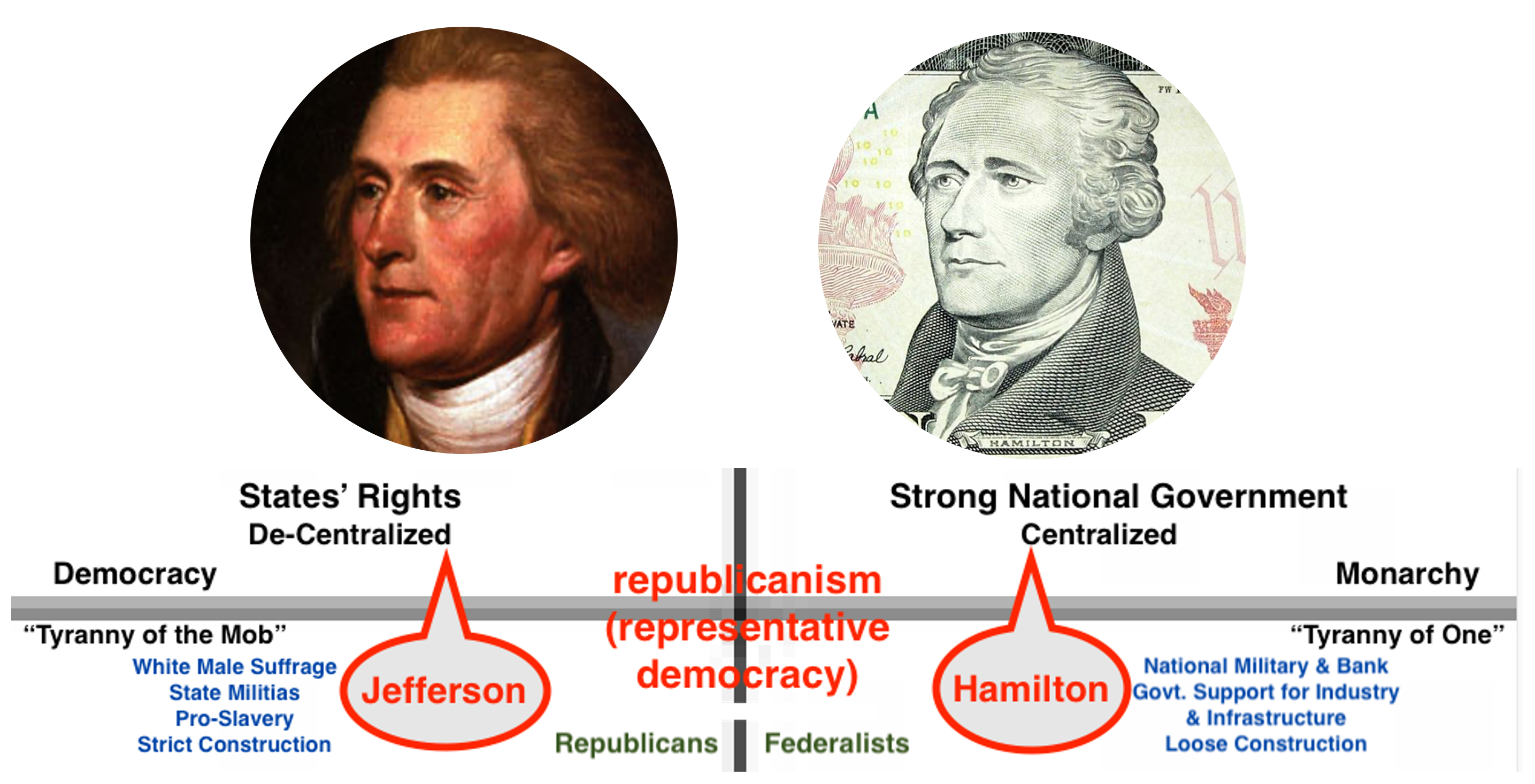

As in biology, war, or sports, there’s a natural tendency in politics to seek advantage by teaming up. In Washington’s case, factions formed right away around members of his own cabinet. Congressmen, voters, and journalists coalesced around either Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson or Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton. The State Department manages foreign relations while the Treasury collects taxes and tariffs, prints money, and manages the national debt while Congress sets the budget. These strong-willed statesmen had divergent views as to how the young republic should develop and neither secretary stayed purely on his own turf of diplomacy or the domestic economy. Historian Andrew O’Shaughnessy wrote that Jefferson and Hamilton “were both fighting for the soul of the American Revolution.”

Because their realms overlapped, Jefferson concerned himself plenty with the domestic economy and Hamilton, likewise, with foreign policy. Jefferson wanted states to retain most of the power in an expansive agricultural empire, whereas Hamilton thought America’s survival depended on thriving industry and a strong central government. The country was lucky to have two of the smartest statesmen in its history just as it formed — and maybe the challenge brought out the best in them — but also lucky to survive as it teetered on civil war between Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans and Hamilton’s Federalists. Meanwhile, unable to swim on its own economically, the U.S. dog-paddled to avoid getting sucked into the whirlpool of European conflicts.

Hamilton & the Federalists

It’s easy to characterize Hamilton as an elitist because he thought most white males were too uneducated to vote, but he was a founding member of a manumission society in New York (despite owning an enslaved servant) and the only Founder not born into favorable circumstances. He was a bastard child, an old-fashioned term for children born out of wedlock, from the small Caribbean island of Nevis — the only Founder born outside the original thirteen colonies. He grew up in St. Croix, in the Virgin Islands. He wrote such an eloquent account of a hurricane that destroyed St. Croix in 1772 that townspeople pitched in to send him to the mainland colonies for an education. He attended Columbia University in New York (then King’s College) and converted to the patriot cause under the tutelage of tailor-haberdasher Hercules Mulligan, later an important spy who helped save Washington from being kidnapped (Chapter 9). While living with Mulligan, Hamilton joined the Sons of Liberty and the precocious teenager published two anonymous essays supporting Continental Congress in its stance against British oppression. He fought heroically in the Revolution at White Plains, Long Island, and Trenton, and led a bayonet charge at Yorktown. Hamilton attracted Washington’s attention, eventually becoming his aide-de-camp (right-hand man) and, in effect, his surrogate son since the Washingtons had no children.

While not the most famous of the Founders, the “dude on the ten” reemerged onto the American stage in the Broadway hip-hop musical Hamilton (2015) by Grammy- and Tony-Award winner Lin-Manuel Miranda. The first run starred African-American and Latino actors portraying principal roles as Hamilton, Washington, Madison, Jefferson, Marquis de Lafayette, and Aaron Burr. We saw earlier how a 1914 painting of the first Thanksgiving could at least tell us about 1914, if not 1621. Likewise, Hamilton is a great primary source archive of 2015, if not 1795. Having minority actors play white roles resonated during Barack Obama’s second term as America’s first African-American president, it was pro-immigration in an era of increasing diversity and anti-immigration pushback, and lines like “this is not a moment, it’s a movement” and “history has its eyes on you” synced with social movements like Black Lives Matter. Conservatives, meanwhile, asked tough questions as to why we no longer tolerated white actors playing other races just as we embraced the inverse. Miranda said audience receptions shifted from hope to defiance as Obama gave way to Donald Trump. As with every topic in history, we interpret Hamilton through the prism of the present day. That’s why history is an ongoing argument.

While not the most famous of the Founders, the “dude on the ten” reemerged onto the American stage in the Broadway hip-hop musical Hamilton (2015) by Grammy- and Tony-Award winner Lin-Manuel Miranda. The first run starred African-American and Latino actors portraying principal roles as Hamilton, Washington, Madison, Jefferson, Marquis de Lafayette, and Aaron Burr. We saw earlier how a 1914 painting of the first Thanksgiving could at least tell us about 1914, if not 1621. Likewise, Hamilton is a great primary source archive of 2015, if not 1795. Having minority actors play white roles resonated during Barack Obama’s second term as America’s first African-American president, it was pro-immigration in an era of increasing diversity and anti-immigration pushback, and lines like “this is not a moment, it’s a movement” and “history has its eyes on you” synced with social movements like Black Lives Matter. Conservatives, meanwhile, asked tough questions as to why we no longer tolerated white actors playing other races just as we embraced the inverse. Miranda said audience receptions shifted from hope to defiance as Obama gave way to Donald Trump. As with every topic in history, we interpret Hamilton through the prism of the present day. That’s why history is an ongoing argument.

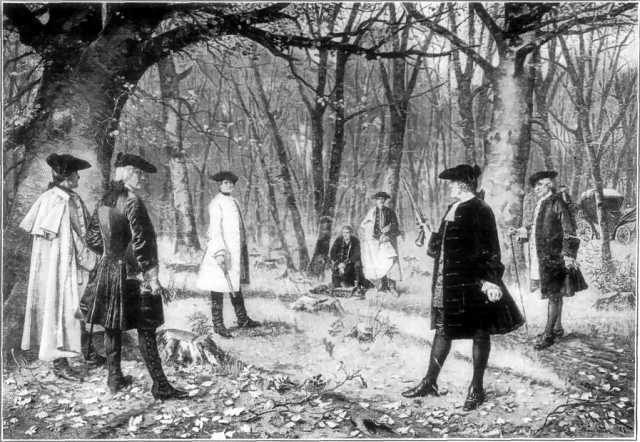

Hamilton didn’t believe in European aristocracy, where mediocrity inherited power by birthright, but he believed in meritocracy, whereby deserving people could work their way up into power, just as he did. He’d pulled himself up by his own bootstraps, even if the saying wasn’t around yet. His up-and-coming status likely contributed to other elite Founders’ wariness. Speaking more of Hamilton’s professional ambition than love life, John Adams said that the Treasury Secretary “had a superabundance of secretions that he could not find enough whores to draw off…the same vapors produced his lies and slanders by which he totally destroyed his [Federalist] party forever and finally lost his life in the field of honor [his duel with Aaron Burr in 1804 – next chapter].”

Hamilton had some monumental tasks before him. He was tasked not just with running, but really creating the Treasury, drafting the first budget, starting the Coast Guard and Customs Service, and setting monetary policy. He basically started America’s financial system from scratch, and was the biggest influence later on Canada’s (the Bank of Montreal’s 1817 charter copied the First National Bank’s verbatim). Just as Madison immersed himself in political history before the Constitutional convention, Hamilton was well-versed in the financial histories of Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Republic, and Britain. He didn’t want the Constitution and anti-Federalist, states’ rights sentiment stifling the young country, keeping it from developing into an economic power. He thought the fragile young republic needed leadership from the central government and that a diverse economy, including both farming and industry, would provide the best foundation. For Hamilton, the U.S. could only survive by competing on European terms, with the national government overseeing a self-sufficient manufacturing base, protected by a strong military, central bank, solid patent office, and tariffs (import duties) to discourage foreign competition. Hamilton predated the association of pro-business with free markets and weak government. In the Early Republic, to be pro-business was to favor a stronger central government and oppose free trade.

As Treasury Secretary, Hamilton jump-started a planned industrial village at Paterson, New Jersey below the Great Falls of the Passaic River northwest of Manhattan. The initial Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.) at Paterson went belly up in 1795 but, in the 19th century, grew into a source for firearms, locomotives, paper, and cotton/silk industries. Samuel Colt later manufactured rifles and revolvers there. If Hamilton were alive in our time, he would unapologetically embrace the idea of a military-industrial complex. That’s what strong countries like Britain had, where a central bank facilitated an expansionary government working cooperatively with munitions manufacturers and shipbuilders. Hamilton’s bank idea was based on the Bank of England, established in 1694 to fund one of England’s many wars against France. With an empire “on which the Sun never set,” the Brits didn’t dither around babbling about states’ rights, strict constitutional principles or, heaven forbid, free trade.

America needed protection not only from European powers but also Native Americans on the frontier. Early in Washington’s presidency, a coalition of Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware Indians led by Blue Jacket and Little Turtle routed a small, ill-equipped, insufficiently trained and disorganized army in the Indiana Territory at the Battle of the Wabash (aka St. Clair’s Defeat). Camp followers ate through too many provisions and Commander Arthur St. Clair II was so overweight he had to be carted through the woods. Proportionally, Wabash was America’s worst defeat ever at the hands of Indigenous Americans and the president blew a gasket when he found out. His private secretary reported that, uncharacteristically, Washington was screaming down curses on St. Clair, who, of course, wasn’t there and whom Washington had warned against surprise attacks. This was when Washington usurped his Constitutional authority by calling up a national militia without Congressional approval — laying the foundation for future Executive Orders — and the Wabash defeat led to calls for a more substantial multi-regiment standing army. General “Mad” Anthony Wayne strengthened the new Legion of the U.S. and they won control of the Ohio Territory from combined Indian-British forces at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

The Legion’s strengthening and expansion is an easy-to-overlook but key point in America’s history because, as we learned in the previous chapter’s section on the Second Amendment, the idea of the government having a standing (permanent) national army was controversial. Like Whigs in Britain, anti-Federalist republicans saw standing armies as tilting too much power toward a central government and such armies tended to recruit unsavory mercenaries as soldiers — the sort that colonials didn’t like living in their cities prior to the Revolution. Militias, conversely, ideally drew from regular, dependable men with a stake in society. Washington, though, saw the U.S. winning the Revolution not because of militias, as commonly thought, but in spite of undisciplined militias. While Washington was angry about the Wabash fiasco, it conveniently helped enlarge and strengthen the army he’d been promoting since the Revolution. In 1796, the Legion of the U.S. (now 1st and 3rd Infantry) was renamed the U.S. Army.

Internationally, Hamilton thought of the U.S. as a potential player in the Atlantic world in relation to other European powers, even while avoiding alliances and unnecessary entanglements. Once, when speaking about the need for a stronger military, he started a sentence, “With Canada on our left, and Latin America on our right…” What’s telling is his perspective looking east across the Atlantic. Jefferson undoubtedly would have started the sentence, “With Canada on our right, and Latin America on our left” because his idea was to leave Europe in the rearview mirror and look west. Had Jefferson lived into the 1830s, he would’ve fist-bumped Horace Greeley when the New York Tribune editor advised, “Go west, young man. There is health in the country, and room away from our crowds of idlers and imbeciles.”

Hamilton was a broad, or loose constructionist, meaning that he thought that if the Constitution didn’t expressly prohibit the national government from doing something necessary and proper to conduct its affairs, then it could. The “Elastic Clause” (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 18) was one of his favorites because it gives Congress all the powers “necessary and proper” to carry out its business, along with the “Supremacy Clause” (Article 6, Clause 2) that gives the national government precedence over conflicting state laws or constitutions. In Miranda’s Hamilton, his character tells Jefferson, “The Union needs a boost; you’d rather give it a sedative.” Hamilton hoped to promote manufacturing, make the U.S. self-sufficient, and create a bank more substantial and public than the Revolutionary-era Bank of North America that the government could run its business through and lead the economy. He advocated revenue-raising tariffs (import taxes) as a source of income for the government but also wanted to foster healthy trading partnerships abroad. Hamilton also wanted to foster some less healthy trading relationships, insofar as he and his assistant Trench Coxe encouraged smuggling as much pirated technology out of England as possible, especially in textiles (clothing, fabrics). Hamilton’s interpretation of the Elastic Clause was itself elastic, as earlier when he was arguing for Constitutional ratification in Federalist No. 33, he implied that the clause only meant that the national government could conduct business it was expressly tasked with elsewhere in the Constitution — nothing more.

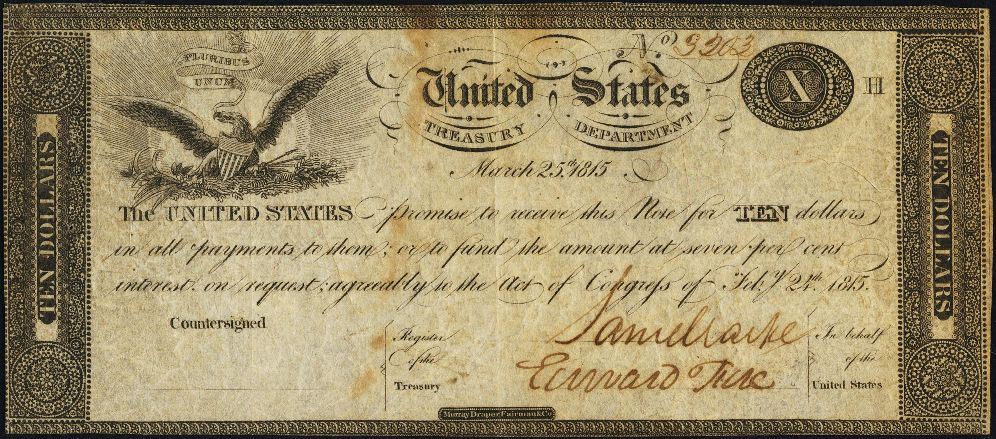

With his Assumption Plan, Hamilton advised the national government to provide stability and credibility to the young country by assuming, or taking over, all the state debts. The national government was $50 million in debt from the war and the states collectively owed another $25 million, mostly to French and Spanish banks. Hamilton’s idea was to consolidate debt at the national level and the government would then finance its debt through customs duties (tariffs) and issuing new securities (i.e. treasuries or bonds) that would, in turn, give the wealthiest American investors a stake in its survival.

The concept was similar to paying Washington’s officers in war bonds during the Revolution. In that case, it made the officers want to win more to collect; in this case, bond investors would have a stake in the U.S. surviving and winning wars. States that had already paid off some of their debt, like Virginia, understandably didn’t think their citizens should have to help pay off other less responsible states’ full debt at the national level.

This was a turning point in the country’s history as Hamilton consolidated a national economy with a centralized, government-led bank and currency. As mentioned in the previous chapter, this unified approach strengthened the American economy over the long term in comparison to looser federations like modern Europe. American workers can move freely between states with higher or lower unemployment, unhampered by separate state currencies or need for work visas. A dollar in Texas is a dollar in California. American credit has remained strong, whereas who knows what would’ve happened if individual states had been running separate monetary systems. Even with Hamilton’s system, though, it was another 80 years before the U.S. truly standardized its currency. The Constitution grants the national government the right to coin money (Article I, Section 8, Clause 5) but was silent on bank notes, so initially states and banks printed their own cash. It wasn’t until the Civil War that northern states agreed on a shared consensus honoring “greenbacks” (U.S. cash). Meanwhile, the way Hamilton’s plans played out in the short term was controversial, leaving some people justifiably angry and embroiling his faction in a major political rivalry with Jefferson’s.

This was a turning point in the country’s history as Hamilton consolidated a national economy with a centralized, government-led bank and currency. As mentioned in the previous chapter, this unified approach strengthened the American economy over the long term in comparison to looser federations like modern Europe. American workers can move freely between states with higher or lower unemployment, unhampered by separate state currencies or need for work visas. A dollar in Texas is a dollar in California. American credit has remained strong, whereas who knows what would’ve happened if individual states had been running separate monetary systems. Even with Hamilton’s system, though, it was another 80 years before the U.S. truly standardized its currency. The Constitution grants the national government the right to coin money (Article I, Section 8, Clause 5) but was silent on bank notes, so initially states and banks printed their own cash. It wasn’t until the Civil War that northern states agreed on a shared consensus honoring “greenbacks” (U.S. cash). Meanwhile, the way Hamilton’s plans played out in the short term was controversial, leaving some people justifiably angry and embroiling his faction in a major political rivalry with Jefferson’s.

Here’s why: to make good on their credit, the government also redeemed bonds (IOU’s) paid to Continental soldiers at full value, including those that soldiers pawned off at steep discounts because they were unsure of whether the new nation would remain solvent. As we saw in the previous chapter with Daniel Shays’ Rebellion, speculators that gambled it would and bought the bonds cheap were seen as ripping off veterans, especially if those investors were connected to Hamilton’s circle and were privy to the Assumption Plan, which was insider trading. One of Hamilton’s lieutenants in the Treasury, William Duer, personally stood to make a fortune if they converted the discounted notes at full face value.

This controversy over how to clean up America’s books led to a split between Hamilton and James Madison, co-author along with Hamilton of the Federalist Papers that had helped get the Constitution explained and ratified a few years prior. When he returned from his work as Minister to France in late 1789 to start his work as Secretary of State, Jefferson sided with his neighbor Madison. They were understandably upset that congressmen who supported the bank got shares before its initial public offering. The resulting factions became the Federalist-Republican split that divided Washington’s cabinet, led by the Federalist Hamilton and the Republican Jefferson. They say, “Money is the root of all evil.” If a bit of an overstatement, it was, in this case, at least the root of America’s first two-party system. Jefferson and Madison called investors in the Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) “dabblers in federal filth.”

Jefferson & the Republicans

The Jeffersonians saw no need for a national bank or any elaborate debt refinancing. The Constitution puts the House of Representatives in charge of raising revenue (Article I, Section 7, Clause 1), but Congress was in recess in 1789 when Washington instructed Hamilton to raise necessary funds. During an excursion on the Hudson River with their colleague Robert Livingston, Jefferson and his allies formed a group they called the Republicans to fight Hamilton’s bank. But their concerns went beyond the national bank and the corruption surrounding it.

Jefferson and James Madison didn’t want to mimic Europe or import the nascent industrial revolution to American shores – quite the contrary. For one, they saw farmers and landowners as more dependable patriots than businessmen. Jefferson wrote: “Merchants have no country. The mere spot they stand on does not constitute so strong an attachment as that from which they draw their gains.” (TJ to Horatio Spafford, 3.17.1814). The Virginians saw manufacturing as a source of pollution and urban squalor and viewed big cities, in the Enlightenment natural man tradition, as hastening the decline of civilization, even though America’s largest cities were then only around 10k people. Jefferson hoped America would remain a predominantly rural country, with honest yeoman farmers, small craftsmen, and fishermen (including whalers) forming the backbone of the economy. The U.S. would avoid the historical evolution of civilizations from this idealized state of innocence toward decadent urbanization, instead expanding geographically toward the Pacific Ocean. There would be no need for strong national government or a large standing military in Jefferson’s scenario. He wasn’t anti-government; he believed in strong, participatory government at the local or state level. More local yet, he viewed almost all decision-making occurring in wards (small counties) among an active, well-educated citizenry. If Jefferson were alive today, the part of our government he’d most appreciate would likely be city councils and school boards. In the Jeffersonian scenario, America would avoid European wars and, if someone attacked, it would simply embargo some of the agricultural and fishing exports it traded to others in exchange for manufactured items (you may already pick up on a flaw in this plan…stay tuned for the next chapter). When it came to factories, you could think of Jefferson as a neo-NIMBY (Not-In-My-Backyard). Britain and Europe’s working classes could live in squalor under the soot. As for his romantic view of farming, Jefferson didn’t have to bust his own sod at Monticello as he had a staff of enslaved workers for that.

In the Jeffersonian scenario, America would avoid European wars and, if someone attacked, it would simply embargo some of the agricultural and fishing exports it traded to others in exchange for manufactured items (you may already pick up on a flaw in this plan…stay tuned for the next chapter). When it came to factories, you could think of Jefferson as a neo-NIMBY (Not-In-My-Backyard). Britain and Europe’s working classes could live in squalor under the soot. As for his romantic view of farming, Jefferson didn’t have to bust his own sod at Monticello as he had a staff of enslaved workers for that.

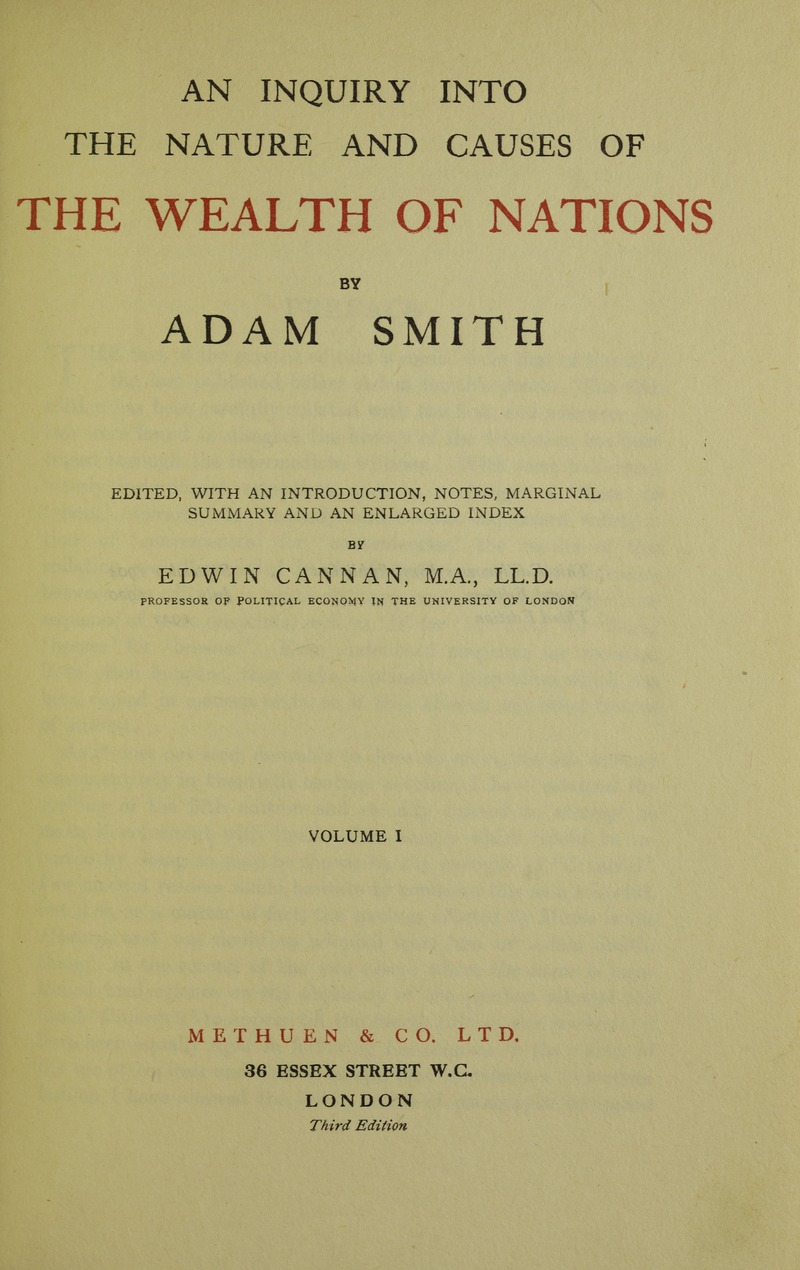

Constitutionally, Jefferson was a strict constructionist believing that, unless the text expressly authorized the national government to do something, it could not. Strict constructionists emphasized the Tenth Amendment, which grants the states power over all matters not expressly enumerated in the main body of the Constitution. Of course, no one at the time could envision a national government that would finance railroads and interstate highway systems, fight titanic global wars, build hydrogen bombs, go to the moon, invent the Internet, build water systems, conduct medical research, prevent the spread of disease, provide a public pension system for the elderly and a safety net for the unemployed, and make all the kids go to school where they’d be fed a meal and do pull-ups. But, if they had, the strict constructionists would have opposed it. States’ rights conflicted with broad interpretations of the Commerce Clause (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3), that grants the national government power over interstate commerce and, potentially, a national ban on slavery. The important thing at the time, though, was that the strict constructionists opposed Hamilton’s ideas for a national bank and trade tariffs. And as followers of Scottish economist Adam Smith, author of the influential Wealth of Nations (1776), Jefferson and Madison favored free trade over the mercantilist model of countries and influential guilds hoarding wealth/gold by channeling trade with restrictions and import duties.

Constitutionally, Jefferson was a strict constructionist believing that, unless the text expressly authorized the national government to do something, it could not. Strict constructionists emphasized the Tenth Amendment, which grants the states power over all matters not expressly enumerated in the main body of the Constitution. Of course, no one at the time could envision a national government that would finance railroads and interstate highway systems, fight titanic global wars, build hydrogen bombs, go to the moon, invent the Internet, build water systems, conduct medical research, prevent the spread of disease, provide a public pension system for the elderly and a safety net for the unemployed, and make all the kids go to school where they’d be fed a meal and do pull-ups. But, if they had, the strict constructionists would have opposed it. States’ rights conflicted with broad interpretations of the Commerce Clause (Article 1, Section 8, Clause 3), that grants the national government power over interstate commerce and, potentially, a national ban on slavery. The important thing at the time, though, was that the strict constructionists opposed Hamilton’s ideas for a national bank and trade tariffs. And as followers of Scottish economist Adam Smith, author of the influential Wealth of Nations (1776), Jefferson and Madison favored free trade over the mercantilist model of countries and influential guilds hoarding wealth/gold by channeling trade with restrictions and import duties.

As Jefferson is wrongly thought to have said about minimalism, “That which governs least governs best.” The phrase belies Jefferson’s passion for strong local government but is true to his vision for a minimalist national tier. However, he never said it in the first place; Henry David Thoreau picked it up from a magazine, attributed it to Jefferson in Civil Disobedience (1849), and it’s been with him ever since until Ronald Reagan grabbed it in the 1980s. Along with his support of slavery, his states’ rights commitment made Jefferson popular in the South and West, where he endorsed spreading the vote to all white males, including the property-less. He helped bring about such universal white manhood suffrage in the Old Northwest, too, by authoring the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 (previous chapter).

Dinner Deal

As Hamilton and Jefferson’s allies fought these conflicting ideas out in the newly formed Congress, things ground to a virtual halt. Nothing passed. Contrary to popular opinion, gridlock is not always bad. Rather, it’s part of how our branches of government and political parties check and balance each other. Congress, after all, isn’t a factory whose goal is to produce as many laws as possible. If the parties are balanced, then it’s perfectly within their right to block each other over genuine policy disagreements. Having said that, total gridlock is bad and the framers envisioned some compromise. It was especially bad for the new U.S. government to stumble out of the gate into gridlock, accomplishing nothing while skeptical Europeans looked on bemused. Would this new constitution even work at all?

It was best for all concerned, in this case, to compromise. Jefferson brought together Hamilton and the Republicans’ congressional leader, James Madison. Over food and wine, the principals agreed to what became known as the Dinner Deal. Really, the actual dinner is partly a symbolic legend for a compromise they hammered out in various negotiations and in Congress. Jefferson and Madison consented to Hamiltonian finance in exchange for Federalists agreeing to move the capital away from the “stinking sewer of New York City” to a more Southerly locale – specifically a new city in the Virginians’ backyard, just north of Washington’s plantation at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers. There’s no official record of how many glasses of wine Jefferson had before calling Hamilton’s hometown a stinking sewer, or what Hamilton muttered under his breath as he agreed to turn the nation’s capital into a southern plantation. Philadelphia, more central than NYC, would be used as the temporary capital in the 1790s. That, at least, is the common interpretation of the Dinner Deal, drawn from Jefferson’s writings. In truth, Madison already had the necessary votes to move the capital, but what he and Jefferson coaxed out of Hamilton on the night of June 20, 1790, was a $1.5 million reduction in the amount their home state of Virginia contributed toward national debt assumption.

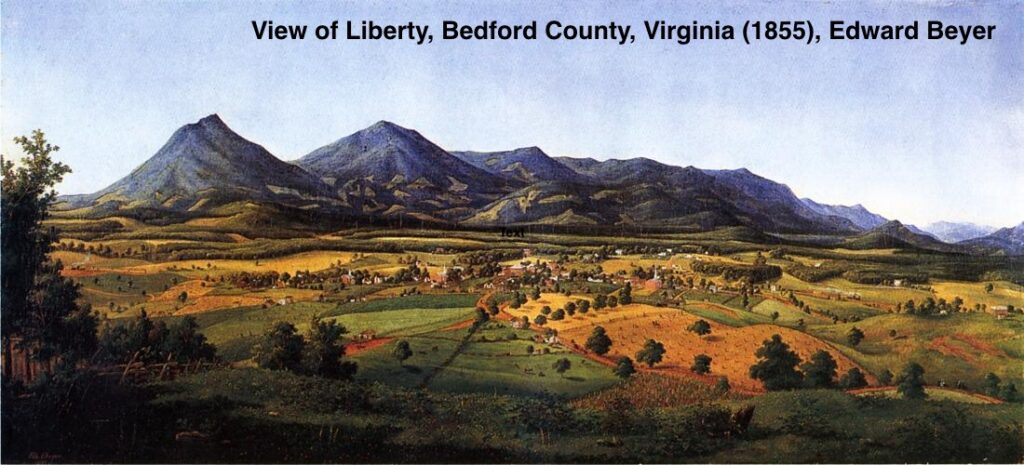

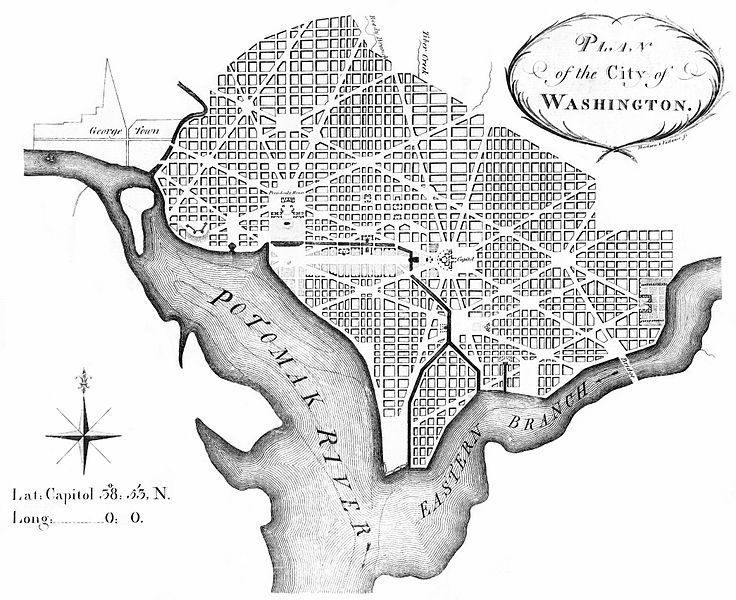

Plan of the City of Washington, Engraving on Paper, Andrew Ellicott, Revised From Pierre (Peter) Charles L’Enfant, Thackara & Vallance sc., Philadelphia 1792, Library of Congress

Thereafter, Southerners hoped to keep a closer eye on things in the new District of Columbia, nestled between the existing ports and slave auctions of Alexandria, Virginia and Georgetown, Maryland. Jefferson and Washington helped oversee construction of the new “Washington City,” aka the Federal City. Jefferson named the legislative building the capitol, Latin for city on a hill. Above is French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s original design from 1792. African American Benjamin Banneker, an important astronomer and almanac author from Maryland, also contributed to D.C.’s design. Banneker’s cabin burned the day of his funeral in 1806, destroying all his records regarding the Federal City, clocks he’d made, and other research.

Thereafter, Southerners hoped to keep a closer eye on things in the new District of Columbia, nestled between the existing ports and slave auctions of Alexandria, Virginia and Georgetown, Maryland. Jefferson and Washington helped oversee construction of the new “Washington City,” aka the Federal City. Jefferson named the legislative building the capitol, Latin for city on a hill. Above is French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s original design from 1792. African American Benjamin Banneker, an important astronomer and almanac author from Maryland, also contributed to D.C.’s design. Banneker’s cabin burned the day of his funeral in 1806, destroying all his records regarding the Federal City, clocks he’d made, and other research.

In return for the southern capital and reduction in Virginia’s contribution to debt reduction, Jefferson and Madison called off the Republican dogs in Congress and Hamilton got his way with debt assumption. And Hamilton later secured passage of the First Bank of the United States (BUS) and establishment of a national currency, along with keeping the military at the national level, as Charles Pinckney and George Mason suggested in the previous chapter. Madison didn’t openly endorse Hamilton’s ideas, but neither did he strenuously oppose them. Later, Jefferson and Madison came to regret the bargain, claiming they’d been duped. Implicit in the legislation was the idea that Congress would have to raise taxes somehow or another, beyond tariffs to help finance debt assumption (treasuries would just incur more debt, kicking the proverbial can down the road). That came the following year with the Whiskey Tax, as we’ll see below.

In 1794, the U.S. minted its first silver dollar coin in Philadelphia, while Jefferson lobbied successfully for the continuation of other local and private currencies and for the decimal system: dollar portions equaled an even one hundred cents. The government didn’t begin to monopolize paper money greenbacks until the Civil War (1862) and some local and private currency continued until 1913, when Congress created the Federal Reserve to manage cash. Although Andrew Jackson terminated the public/private National Bank in the 1830s, a non-profit, public, centralized “banker’s bank” emerged with the Federal Reserve in 1913. With passage of the 1790 Funding Act, brokers began buying and selling restructured U.S. debt that had been assumed from the states and, to this day, the default rate on U.S. debt securities is 0%. These treasuries (bonds, notes) got off to a good start in the 1790s because Europeans, skittish over the Napoleonic Wars, saw the young U.S. as the safest place to put their money despite its unproven reputation. In the minds of modern Chinese, Japanese, and Saudi Arabians, U.S. bonds are still the safest money in the world outside of perhaps gold or, maybe in the future, some decentralized cryptocurrency.

Investors started buying and selling bonds and stock shares at 68 Wall Street in lower Manhattan, under a Buttonwood tree. In time, they institutionalized themselves as the New York Stock Exchange and moved indoors. The first shares on the exchange were those of the original North American Bank, the government’s First Bank of the United States (BUS), and then Hamilton’s own Bank of New York, now BNY Mellon. Unlike most countries, America’s financial capital of New York and political capital of Washington are in separate spots, but the government actually started near the Stock Exchange before it moved to Philadelphia (the original Federal Hall, below, burned in 1812). Since Hamilton is the “godfather of Wall Street,” his reputation has risen and fallen in lockstep with markets. His name was dirt in the Great Depression of the 1930s, but favorable biographies started popping up as last-minute Father’s Day presents from Barnes & Noble during the bull run of the 1980s-’90s, and he’s found a fresh audience with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical.

Investors started buying and selling bonds and stock shares at 68 Wall Street in lower Manhattan, under a Buttonwood tree. In time, they institutionalized themselves as the New York Stock Exchange and moved indoors. The first shares on the exchange were those of the original North American Bank, the government’s First Bank of the United States (BUS), and then Hamilton’s own Bank of New York, now BNY Mellon. Unlike most countries, America’s financial capital of New York and political capital of Washington are in separate spots, but the government actually started near the Stock Exchange before it moved to Philadelphia (the original Federal Hall, below, burned in 1812). Since Hamilton is the “godfather of Wall Street,” his reputation has risen and fallen in lockstep with markets. His name was dirt in the Great Depression of the 1930s, but favorable biographies started popping up as last-minute Father’s Day presents from Barnes & Noble during the bull run of the 1980s-’90s, and he’s found a fresh audience with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical.

As for separating political and financial power geographically, many U.S. states followed suit, which is why state capitals are often somewhere other than the biggest cities (e.g. Sacramento, Olympia, Salem, Albany, Tallahassee, Columbus, Springfield, Lansing, Harrisburg, Austin, etc.). That is why some commentators disliked one of Amazon’s HQ2’s going to Washington, D.C. (Arlington, Virginia), because financial clout and political power are difficult enough to keep untangled in our system as it is without having business and political leaders living next to each other.

French Revolution

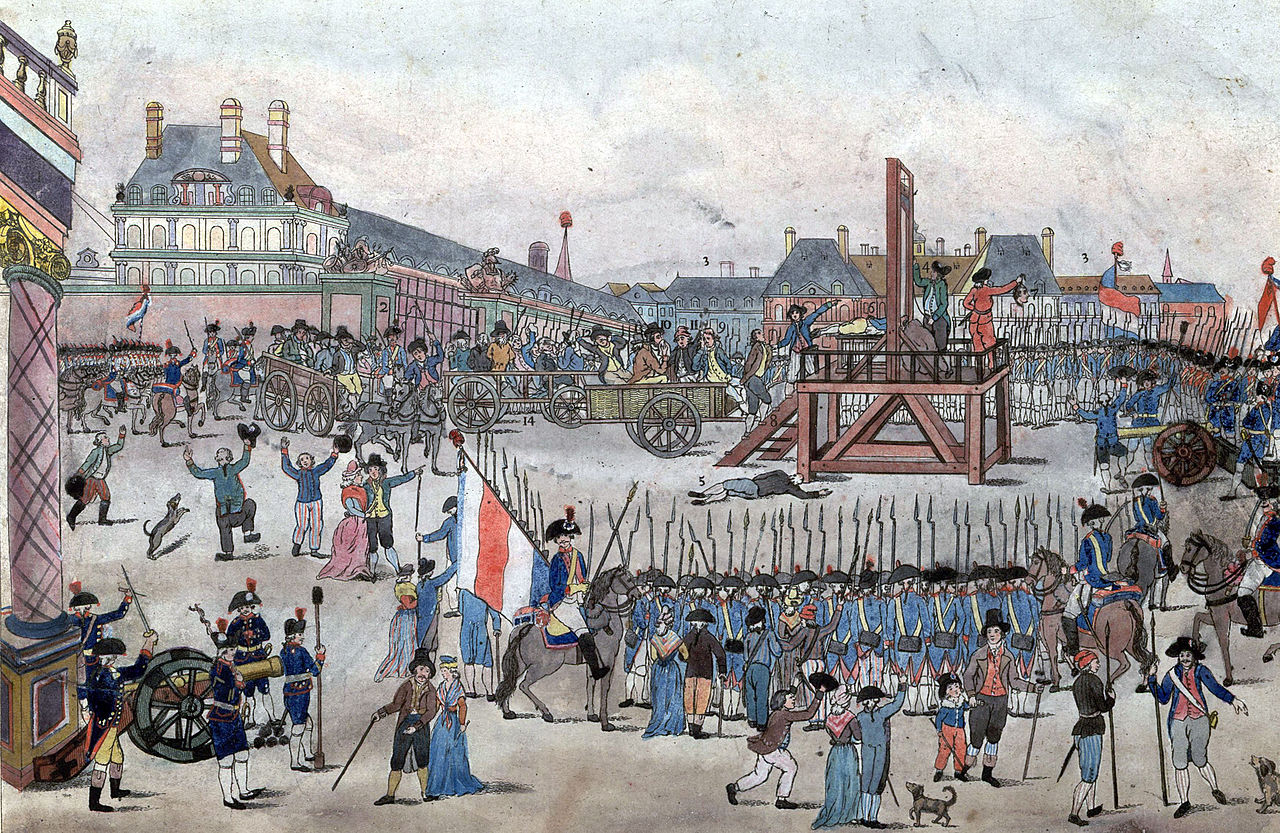

European politics complicated this already divisive political atmosphere, compounding partisanship between Federalists and Republicans. The brief English Commonwealth of the 17th century notwithstanding, the French Revolution was the first lasting overthrow of a monarch, leading to the decapitation of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette in 1793 and the wholesale, if temporary, overhaul of France into a republic.

Storming of the Tuileries on 10. Aug. 1792 During the French Revolution, Jean Duplessis-Bertaux, 1793

As we saw in Chapter 9, the French Revolution was connected to the American Revolution, since King Louis XVI was so intent on defeating Britain that he ran the Crown into debt. In 1781, the year French helped Americans defeat Brits at Yorktown, the French Navy was running a budget 5x its normal amount. While focusing French support on Americans, the king inadvertently helped popularize republican ideas among France’s middle and upper classes, who now sought to overthrow him. In the meantime, drought caused several bad harvests in a row, emboldening the hungry lower classes that were already upset about a new salt tax. French aristocracy (~ top 2%) and the Catholic Church exempted themselves from taxes, pushing all the burden on the poor, farmers, tradesmen, and bourgeoisie (merchant class). As we learned from the American Revolution, those are bad groups to alienate simultaneously.

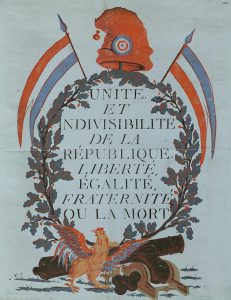

The resulting revolution inspired causes associated with its now-famous motto of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (right), including the abolition of slavery in French colonies, more racial equality at home (tearing down ghetto walls to integrate Jews), establishment of a modern legal system, creation of a non-Christian/Roman calendar, and endorsement of a rational metric measuring system. Republicans looted the royal art collection to seed the Louvre Museum, that opened in 1793. Oddly, the revolutionaries outlawed smiling in portraits, which had recently come into fashion due to improved dentistry. They refashioned Christian cathedrals, including Notre Dame, as Temples of Reason and threw some priests into the Seine River tied to rocks. Forty-thousand French parishes in 1789 shrunk to hundreds by 1794. Under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796, French armies seized Rome and imprisoned the Pope. Revolutionaries converted the famous Mont Saint-Michel abbey/monastery into a state prison and converted monks into guards. Opponents and suspected opponents of the Revolutionary Reign of Terror died by the thousands, including the king and queen, virtue of Joseph-Ignace Guillotine’s new humane tool of capital punishment (see Robespierre’s head displayed below). Revolutionaries imprisoned and nearly killed Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense (Chapter 8), because he lobbied to grant Louis XVI asylum in the U.S. as thanks for his role in winning the American Revolution and because he opposed capital punishment on moral grounds, especially a vengeance killing.

The resulting revolution inspired causes associated with its now-famous motto of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (right), including the abolition of slavery in French colonies, more racial equality at home (tearing down ghetto walls to integrate Jews), establishment of a modern legal system, creation of a non-Christian/Roman calendar, and endorsement of a rational metric measuring system. Republicans looted the royal art collection to seed the Louvre Museum, that opened in 1793. Oddly, the revolutionaries outlawed smiling in portraits, which had recently come into fashion due to improved dentistry. They refashioned Christian cathedrals, including Notre Dame, as Temples of Reason and threw some priests into the Seine River tied to rocks. Forty-thousand French parishes in 1789 shrunk to hundreds by 1794. Under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796, French armies seized Rome and imprisoned the Pope. Revolutionaries converted the famous Mont Saint-Michel abbey/monastery into a state prison and converted monks into guards. Opponents and suspected opponents of the Revolutionary Reign of Terror died by the thousands, including the king and queen, virtue of Joseph-Ignace Guillotine’s new humane tool of capital punishment (see Robespierre’s head displayed below). Revolutionaries imprisoned and nearly killed Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense (Chapter 8), because he lobbied to grant Louis XVI asylum in the U.S. as thanks for his role in winning the American Revolution and because he opposed capital punishment on moral grounds, especially a vengeance killing.

The French Revolution was a full-blown Civilization 2.0 reset powered by Enlightenment ideas but stained with horrific streaks of violence, paranoia, and intolerance — a paradoxically illiberal form of liberalism. Charles Dickens put it more eloquently in Tale of Two Cities (1859): “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” The French Revolution ushered in modern history and, despite being republican, was a mass upheaval that set the stage for 20th-century totalitarian uprisings in Russia, Germany, and China. France itself reverted back to authoritarian rule, with more democratic uprisings in 1830 and 1848, and didn’t stabilize as a republic until the 1870s.

Thomas Jefferson supported the French Revolution early on, prior to its worst excesses. In fact, he was an important participant: as American Minister to France, he helped his old friend Marquis de Lafayette draft the French Declaration of the Rights of Man & of the Citizen, the French counterpart to the Declaration of Independence (Lafayette fought with Washington in the Revolutionary War). Jefferson didn’t always approve of the Revolution’s more violent and chaotic aspects, but when challenged to defend the uprising (before the Reign of Terror) he said, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.” How, after all, did monarchs come to power in the first place? Did they peacefully ask for their thrones without harming anyone?

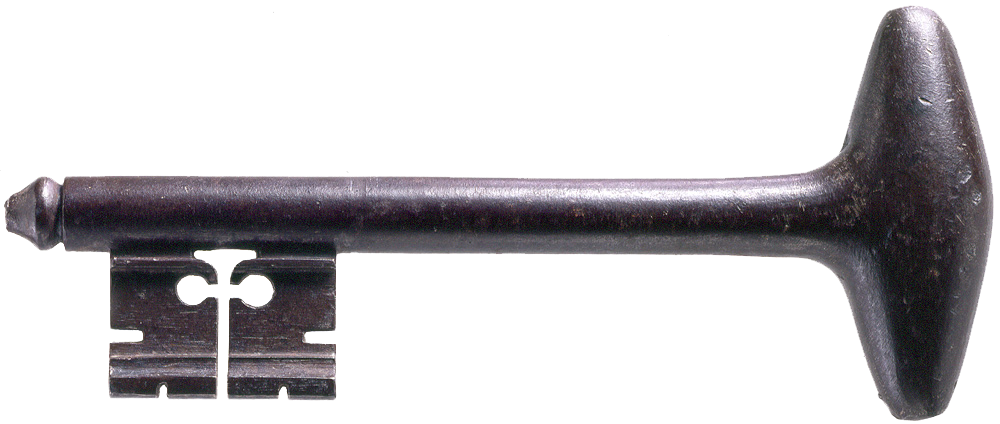

Bastille Key Presented to George Washington From Lafayette via Thomas Paine, Mount Vernon Collection

President Washington didn’t share Jefferson’s enthusiasm for the upheaval in France. His administration was cool toward a revolution that it saw moving too far, too fast. Washington also felt some loyalty to the French Crown from the Revolutionary War and even had a life-sized portrait of Louis XVI at his plantation in Mt. Vernon. Washington politely accepted France’s gift of the main Bastille key to the state prison rebels stormed to release prisoners in one of the revolution’s iconic moments. His old compatriot from the Revolutionary War, Lafayette, sent it after all, even if Washington wasn’t exactly a let’s-free-prisoners kind of guy. And there was another complication. Britain went to war to quash the French Revolution and Washington was hesitant to stir up the British hornet’s nest. As pro-British and pro-French mobs clashed in American streets, Washington issued a formal Neutrality Proclamation. Such a proclamation was not really a Constitutional privilege of the executive branch, but it at least stated the president’s position.

French revolutionaries sent an ambassador to America, Edmond-Charles Genêt, to curry favor with Washington and hire privateers to seize British ships. This is when Washington, to put it in modern urban slang, “gave France the Heisman,” meaning that he distanced himself like the football player stiff-arming an opponent on the famous trophy. “Citizen Genêt,” as he was known to the revolutionary government, wanted the U.S. to abandon its neutrality in an ongoing war between Britain and France and support the French Revolution, but Washington wouldn’t budge. The first president denounced Genêt’s crimes against British shipping and promotion of Democratic-Republican societies. In a rare case where the Anglophile Hamilton and Francophile Jefferson agreed (albeit for different reasons), they supported Washington demanding that Genêt take it back a notch. The “Citizen Genêt Affair” was an early indicator that the U.S. was hesitant to stray too far from its British roots and that President Washington was not radically inclined, defined here as democratic. When the more radical and bloodthirsty Jacobin Club took power in Paris, they issued an arrest warrant for Genêt. Realizing that he’d be sent to the guillotine, Hamilton, Genêt’s most vocal critic, convinced Washington to grant the enthusiastic democrat asylum in America.

French revolutionaries sent an ambassador to America, Edmond-Charles Genêt, to curry favor with Washington and hire privateers to seize British ships. This is when Washington, to put it in modern urban slang, “gave France the Heisman,” meaning that he distanced himself like the football player stiff-arming an opponent on the famous trophy. “Citizen Genêt,” as he was known to the revolutionary government, wanted the U.S. to abandon its neutrality in an ongoing war between Britain and France and support the French Revolution, but Washington wouldn’t budge. The first president denounced Genêt’s crimes against British shipping and promotion of Democratic-Republican societies. In a rare case where the Anglophile Hamilton and Francophile Jefferson agreed (albeit for different reasons), they supported Washington demanding that Genêt take it back a notch. The “Citizen Genêt Affair” was an early indicator that the U.S. was hesitant to stray too far from its British roots and that President Washington was not radically inclined, defined here as democratic. When the more radical and bloodthirsty Jacobin Club took power in Paris, they issued an arrest warrant for Genêt. Realizing that he’d be sent to the guillotine, Hamilton, Genêt’s most vocal critic, convinced Washington to grant the enthusiastic democrat asylum in America.

Meanwhile, other European monarchs didn’t sit by idly hoping that a democratic revolution wouldn’t happen to them. You need look no further than the Arab Spring of 2011 to see that such movements are contagious. Monarchies wanted to nip the French Revolution in the bud to discourage such developments elsewhere. Consequently, the French Revolutionary governments — a series of governments that violently displaced each other in rapid succession — didn’t just have their hands full at home; they were at war with the rest of Europe and Britain. Meanwhile, Russians and Prussians crushed a democratic uprising in Poland led by our old friend from Chapter 9, Tadeusz Kościuszko (engineer of West Point), wiping that country off the map until the 20th century.

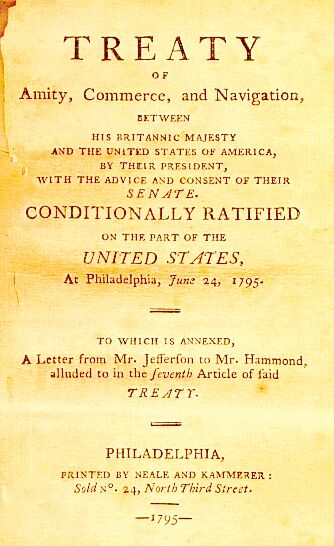

The Washington Administration was hesitant to alienate the British, in particular, since American shipping was susceptible to British attacks in the Atlantic and the U.S. relied on trade with their former colonizers. The U.S. traded with France, as well, but it was hard to say how things would play out there. Britain was a more proven entity and more important to the American economy. Washington chose the lesser of two evils, signing the Jay Treaty (1794-95), whereby the U.S. sided with Britain and the British made empty promises to evacuate the forts of the Old Northwest and ceased attacking American shipping, but the U.S. got virtually nothing else in return. The British had already agreed to evacuate their western forts in the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War and never left. Nor did they even leave after the Jay Treaty, and didn’t until 1815. Worse, with the U.S.-British treaty, the French Navy, the same one that helped the U.S. gain its independence fifteen years earlier, started attacking American ships on their way to Britain.

For Jeffersonians, the Jay Treaty was coddling up to the enemy when they should have been embracing the spread of democracy in Europe by siding with France. Hadn’t France helped the Americans defeat Britain? Whose side were we on in the struggle between monarchy and freedom? The new Constitution gave the president treaty-making powers (Article II, Section 2, Clause 2), but only with approval by two-thirds of the Senate. Republicans demanded to see confidential documents related to the treaty, but Washington refused, declaring executive privilege.

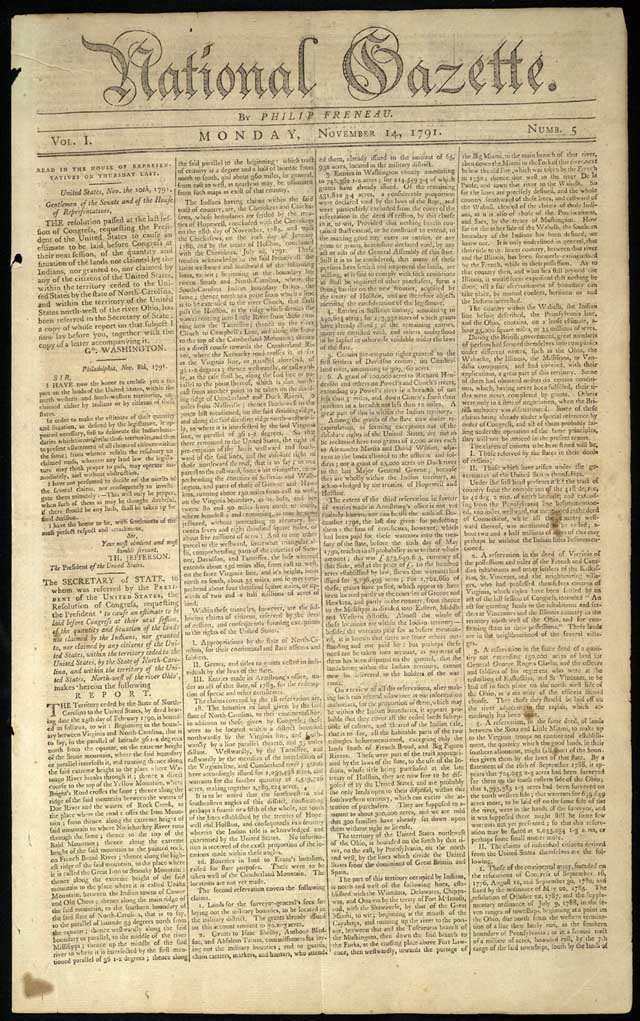

Newspaper War

Newspaper War

Foreign relations drove the wedge deeper between America’s political factions, fueling the Newspaper War. The Federalists and Republicans each had newspapers in Philadelphia cranking out partisan combinations of propaganda and facts on a daily basis. Sound familiar? Breitbart and Huffington Post weren’t around yet so, in this version of narrowcasting, Jefferson’s henchman fulminated in the Philadelphia Aurora (edited by Franklin’s grandson Benjamin Franklin Bache) and Philip Freneau’s National Gazette while Hamilton smeared the opposition through John Fenno’s Gazette of the United States. Hamilton and Jefferson were both guilty of doling out federal contracts to their respective editors (Hamilton for printing and Jefferson for translating). Jefferson’s men excoriated Washington behind his back even as Jefferson served in his administration, but in print they mostly trashed Hamilton. Around this time, Federalists started insulting Jefferson’s Republicans by calling them the Democratic-Republicans, to ridicule their support of the French Revolution and white male suffrage at home. No one called themselves Democratic-Republicans at the time, though, preferring Republican, or a Madison or Franklin, indicating that Republicans identified themselves not just with Jefferson. Later some started to call their group the Democracy, sounding more like a cabal than a political faction.

An aside that we’ll return to in future chapters:

Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans (originally just Republicans) are the historical precursor to today’s Democratic Party. After 1824, a branch forked off calling themselves the National Republicans. They held views more similar to the Federalists of the 1790s and, by the early 1830s, were calling themselves Whigs. The Whigs formed the primary trunk of the anti-slavery Republican Party formed in the mid-1850s, direct precursor to today’s Republican Party. The first president for today’s Republican Party was Abraham Lincoln, elected in 1860.

Jefferson encouraged his followers to “take up [their] pen[s]…and cut [Hamilton] to pieces in the face of the public.” But, in this heated partisan environment, Jefferson blinked first. He quit on President Washington and moved home to his Monticello plantation outside Charlottesville, Virginia, from where he licked his wounds and rallied his rank-and-file supporters. Meanwhile, Republican presses in Philadelphia still hammered Federalists mercilessly at every turn. But with Jefferson gone, Hamilton had Washington’s ear and could commence building a military that the Republicans thought was aimed at them rather than foreign adversaries. As it turns out, their fears were somewhat justified. Sometimes, as the saying goes, even paranoids have [real] enemies.

Whiskey Rebellion

Militaries, however necessary, aren’t cheap and Congress still needed to subsidize Hamilton’s Assumption Plan. The U.S. was already almost $80 million in debt. One irony of the Revolution was that, after fighting a war over taxes, Americans were soon paying more than they ever had as colonists in the British Empire. How could it be otherwise? They now had to run their own country. At least they had greater representation, for those genuinely concerned with that principle. Hamilton wanted to spread the tax burden to the interior so that coastal merchants wouldn’t have to shoulder more than their share. But tax offenders in southwestern Pennsylvania were sent to a federal courthouse in Philadelphia, hundreds of miles away, meaning they’d have to leave their farms behind to appeal their cases. Moreover, the government wasn’t doing as much as westerners hoped to fight Native Americans and secure trading rights from the Spanish on the Mississippi River, key tributaries of which drained from their Ohio Valley. For many westerners, the American Revolution had just shifted the source of evil from London to Philadelphia. In both cases, citizens were answering to a power that seemed remote and didn’t address their concerns. Historian David Houpt wrote that “The Revolution bequeathed a complex legacy that combines a commitment to freedom and liberty with a suspicion of centralized authority.” That’s true today and definitely was in the 1790s, with memories of the war against Britain still fresh.

Hamilton convinced Washington to pay off Revolutionary War debt by taxing distilled spirits. In some respects, this tax was more unfair than anything the British enacted earlier. Congress went along with the idea partly because they preferred an excise tax on manufacturing to a traditional land tax because most of them were big landowners. Congress also liked the fact that the federal government would collect the tax since citizens could intimidate and resist state collectors. Hamilton even produced a letter from the Philadelphia College of Physicians showing the ill effects of alcohol, especially the low-grade spirits distilled on the frontier. Here, Hamilton agreed with Jefferson, who favored wine over whiskey and audaciously lobbied for lowering wine import duties to combat drunkenness (yes, you read that correctly).

Most Americans preferred bartering to using currency for everyday transactions and whiskey barrels were virtually a currency in their own right in the backcountry. Settlers traded whiskey for salt, sugar, iron, powder, and shot. They even paid ministers in barrels. Whiskey made from leftover grain had the additional advantage of keeping, so it was an ideal way to preserve wealth and guard against inflation. The barrels were an agreed-upon size and their content was reasonably consistent. Western farmers who couldn’t readily ship large quantities of grain across the Allegheny Mountains distilled surplus grain into more transportable whiskey. One in six farmers had a small pot still as whiskey had replaced rum as the drink of choice by the late 18th century. While rum made sense in colonial port cities since it depended on the Caribbean molasses trade, frontiersmen were familiar with whiskey from Scotland and Ireland and grew the ingredient cereal grains like barley, wheat, and rye. Many of the settlers around the Forks-of-the-Ohio region of western Pennsylvania (modern Pittsburgh) were rough-hewn Scotch-Irish who’d resisted similar English liquor taxes back in the Old Country. As was the case there, the American showdown pitted smaller, artisanal distillers against bigger professionals because the more one distilled, the less one paid proportionally.

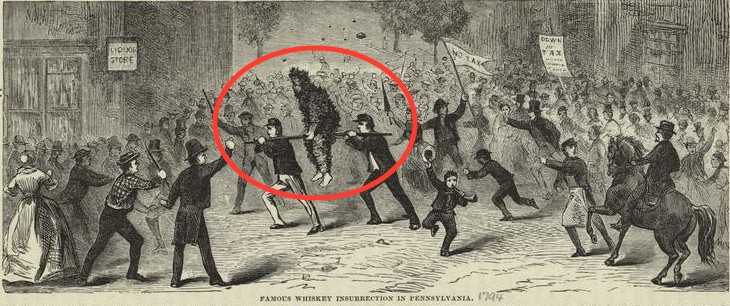

Famous Whiskey Insurrection In Pennsylvania, R. M. Devens, 1882, New York Public Library Digital Collection. Note Tarred Tax Collector

In the ensuing Whiskey Rebellion (1791-1794), frontiersmen from Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Virginia reacted to the tax the same way colonials had reacted to the Stamp Tax a quarter-century earlier: by threatening bodily harm toward anyone who, by God, dared collect it. Whiskey Tax collectors were tarred and feathered, robbed, and beaten at gunpoint. Distillers burned their houses down. If collectors were federal rather than local, all the better. Many of the rebels were in Democratic-Republican societies opposed to Washington’s administration and many were Revolutionary War veterans, fighting for the same principles of local representation they had before. In that way, the Whiskey Rebellion was an early test of whether the new national government really had power over the states and the people.

But the rebels weren’t just angry hillbillies opposing all taxes, or even a national government; they opposed Hamilton’s insistence on consolidating the industry by favoring bigger distillers with regressive taxes that went toward paying interest to wealthy federal bondholders. They expressed as much in well-reasoned editorials, petitions, and pamphlets. Rather than an equal or progressive tax, rates were based on a complicated ratio formula regarding the gallons of wash (fermented grain and water) a distiller’s pot could hold. There was an option to pay a flat fee instead, but only larger distillers could afford the higher flat fee, and they could better pass the cost onto customers. The government was taxing whiskey as it left the still instead of at the point-of-sale, costing even those who made it for their own consumption. Taxing as each batch was prepared punished those who made smaller batches because bigger stills made more whiskey per batch. Had they taxed the overall amount of whiskey made or sold (point-of-sale), they would’ve taxed large distillers at the same rate as small distillers. The upshot is that the regressive tax favored larger, year-round distillers and punished less efficient, seasonal one-pot farmers and frontiersmen.

It was no accident. Hamilton knew how Parliament colluded with big distillers to wipe out one-pot operations in the British Isles. He was a rare man of broad vision and microscopic attention to detail. That’s what made Hamilton so effective and/or dangerous, depending on one’s perspective. Distilleries were just one example of how Hamilton wanted to consolidate and gain efficiency of scale across agriculture and industry that would help fund the government’s budget in the meantime. Today, Hamilton likely would’ve granted concessions to Anheuser-Busch InBev, MillerCoors, and Pabst at the expense of local craft brewers, perhaps requiring the use of wholesale distributors that smaller brewers couldn’t afford. Then he would’ve taxed the big breweries to fund drones and missiles.

Adding insult to injury, each barrel taxed had to be registered with a representative from the Treasury Department, but frontier distillers couldn’t afford to pay for the registration in currency. Rebels would’ve burned Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) to the ground if authorities hadn’t bribed them with, you guessed it, alcohol. Other well-lubricated rebels talked of forming a western state named Westsylvania and seceding from the U.S., and even had a flag. In response, the national government passed a law making it a capital offense to discuss secession and made raising freedom-symbolizing liberty poles seditious (ironic considering the Stamp Act protests).

Adding insult to injury, each barrel taxed had to be registered with a representative from the Treasury Department, but frontier distillers couldn’t afford to pay for the registration in currency. Rebels would’ve burned Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) to the ground if authorities hadn’t bribed them with, you guessed it, alcohol. Other well-lubricated rebels talked of forming a western state named Westsylvania and seceding from the U.S., and even had a flag. In response, the national government passed a law making it a capital offense to discuss secession and made raising freedom-symbolizing liberty poles seditious (ironic considering the Stamp Act protests).

First, Washington sent peace commissioners to resolve the matter. Then, he took matters into his own hands in 1794 and resolved to collect the tax himself at the head of a militia that, at 13k, matched the biggest army he’d led during the Revolutionary War. Think about that: within a generation of that war, the U.S. was raising as many troops against its own citizens as the Continental Army had against Britain. The Whiskey Rebellion also occasioned the first draft in American history and was the first and only time the sitting president ever led troops in the field as Commander-in-chief, though Abraham Lincoln occasionally visited battlefields around Washington, D.C. during the Civil War. Washington compelled area governors to nationalize their state militias to gather his force. Two years earlier he’d signed the first Militia Act, granting himself authority to lead troops domestically. They updated the law numerous times and today translates roughly into the president’s authority to call in the National Guard.

General Henry “Lighthouse Harry” Lee assumed command as the militia approached Pittsburgh, while Hamilton stayed on as a civilian advisor and President Washington returned to Philadelphia. The militia used up its own whiskey on the way over mountains and when they bought more from the rebels it conveniently gave the rebels enough extra money to pay their taxes. They arrested several rebels illegally (violating their Fourth Amendment rights with unlawful search and seizure) but released them due to insufficient evidence after they signed loyalty oaths.

In the Aughts, historians and students viewed the Whiskey Rebellion through the prism of America’s post-9/11 revived police state, with its increased powers of domestic surveillance and imprisonment at Guantánamo Bay and abroad. Sympathetic to the rebels, historian William Hogeland wrote: “hundreds of ordinary citizens were rousted from beds by pumped-up dragoons, marched through the snow to holding pens, detained indefinitely on no charge, harshly interrogated, physically and mentally abused, and made to open their homes to search and property to seizure — all without warrants and on the basis of no evidence.” Yet, despite these initial transgressions and abuses of power, the government only convicted a few rebels and Washington ultimately pardoned them.

The Whiskey Rebellion was the first time the American national government ever used force against its own citizens — in contrast with Shays’ Rebellion when the Confederation Congress was powerless to do so. That was one of the reasons some advocated creating a national government in the first place. With Hamilton, Lee, and Washington bearing down on them, most of the distillers gave up or fled into the hills or west to Tennessee and Kentucky, beyond the reach of the national government. Those in Bourbon County, Kentucky distilled primarily corn mash, leading to the famous whiskey of that name (an etymology disputed by those on New Orleans’ Bourbon Street). Rebel leader David Bradford accepted a land grant in Spanish West Florida (Louisiana) and built the Myrtles Plantation. Westylvania never materialized. In 1798, George Washington opened the largest whiskey distillery in America on his own plantation in Mount Vernon, servicing drinkers of nearby Alexandria, Virginia.

The remaining rebels agreed in principle to pay the tax but, in reality, it proved nearly impossible to collect. Meanwhile, the Whiskey Rebellion was a notch in Jefferson’s belt as it played into the Democratic-Republicans’ portrayal of the Federalist regime as over-bearing, even though D-R leaders tactfully distanced themselves from the hooliganism and mayhem of the early rioting, just as the Founders played down and condemned the Boston Tea Party in 1773 even as they supported its cause. It was a notch in Washington’s belt, too, because he’d shown Americans and Europeans that he and his government were in charge of the country and had ways of raising revenue; and he managed to do it with little bloodshed. Above is the painting version of a “photo-op” for the Federalists to send to Europe, symbolizing that the government was running the country. After Jefferson became president, his administration repealed the Whiskey Tax in 1802. But that was only after Jefferson lost his first bid for the presidency in 1796. The Whiskey Rebellion underscored the challenge all democracies face in balancing free speech and assembly with maintaining law and order and funding the government.

Adams Caught In The Middle

Jefferson ran for president in 1796 against his old friend John Adams, with whom he’d served in Continental Congress twenty years earlier. Washington could have served a third term (the 22nd Amendment prohibiting that wasn’t added until 1951), but he’d had enough and was ready to retire to his plantation at Mt. Vernon. There was much whiskey to be distilled and he was ready for some quality time with Martha. Washington probably wouldn’t have run even for a second term if the intense partisanship of the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans hadn’t threatened to destabilize the young nation.

The 1796 election was critical to American history because it was the first test of opposing factions running against each other and it established a precedent of non-violence. The threat was there, at least in the minds of some but, fortunately, nasty politics and mudslinging won out over civil war. Washington also helped establish the precedent of peaceful transitions of power by stepping down after two terms. However, the election also revealed an important glitch in the Constitution. Not foreseeing political parties, it awarded the vice-presidency to the candidate with the second-most electoral votes. In other words, the candidates didn’t run on tickets with pairs of presidents and vice-presidents. The 12th Amendment of 1804 solved the problem, combining electoral tickets with a president and vice-president.

When Adams won, Jefferson was thus serving as VP under the man he’d just run against. He wasn’t much interested in aiding Adams, so he concentrated on defining the vice-president’s role as president of the Senate, writing procedural manuals still used in Congress today. Adams reached out to his old friend Jefferson hoping for bipartisan reconciliation, but the red-haired Virginian chose to mobilize against Adams as the Democratic-Republicans hoped to defeat him in 1800.

Adams struggled with his own Federalist faction, as well. The High Federalists, as they were called, were more militant in their views than the moderate Adams and wanted him to attack the Democratic-Republicans and France more aggressively, stopping democracy in its tracks. Alexander Hamilton really did consider using the new army against “the Virginians,” the way they’d appeared ready to do during the Whiskey Rebellion. That wasn’t just paranoia on the Jeffersonians’ part.

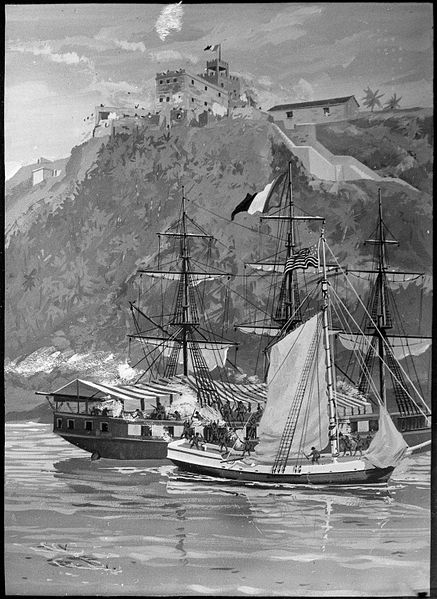

USS Constellation (left), Captures French Frigate L’Insurgente in Quasi-War, 2.9.1799. Navy History & Heritage Command / National Archives

Capture of the French Privateer Sandwich by Armed Marines on the Sloop Sally, From the U.S. Frigate Constitution, Puerto Plata Harbor, Santo Domingo, 11 May 1800, National Archives

The High Federalists wanted full-blown war against France, but Adams resisted. When American diplomats went to Paris to negotiate an end to shipping attacks in the Atlantic, the French humiliated them by demanding $10k just to talk to them in what became known as the XYZ Affair. The French were angry that they’d gone into debt helping to launch the U.S. then, under Washington, the Federalists turned around and sided with Britain against them with the Jay Treaty. Still, Adams made the unpopular decision to not escalate and declare war on France. It cost him at the time, but most historians see his prudence as perhaps a nation-saving decision, with the U.S. Navy being so small at the time. While Adams wisely didn’t ramp up the conflict, a limited Quasi-War between the French and fledgling Navy continued through the 1790s. It was a substantive conflict despite the quasi-qualifier as the French seized 330 American ships. Congress authorized the use of 25 vessels to patrol the coast and Caribbean against French privateers.

Flirting With Civil War

Unlike the Quasi-War, where he held his ground, Adams capitulated to High Federalists with the Alien & Sedition Acts of 1798, outlawing Jeffersonian newspapers and thereby undermining the First Amendment right to free speech within a decade of the Bill of Rights’ ratification. The First Amendment got off to a very rocky start. The Federalists lamely spun their Sedition Law as merely beefing up libel laws that prohibited factually false incriminations. However, the law not only banned false speech, but also “scandalous or malicious writing against the government” and even conspiring to oppose government measures. If the Sedition Act hadn’t expired in 1800, Americans today wouldn’t live in a liberal democracy or enjoy free speech. The Alien portion of the act made foreign immigration more difficult in order to keep French citizens from moving to the U.S. to spread democracy or, in some cases, counter-revolutionary ideas. The Alien Enemies Act stayed on the books, empowering presidents during the War of 1812, WWI, and WWII (Japanese internment camps).

Philadelphia, in particular, was filling up with French refugees, some from the slave rebellion in Haiti and others who fled the French Revolution first to England and then to the U.S. when France went to war with Britain. In this capital city of 40k, Federalists saw a growing population of ~ 5k French opening up bakeries and bookstores and offering French language and dance lessons to young Philadelphians. The Alien Act was intended not only to preserve America’s Anglo identity but also undermine Jefferson’s support since most French supported the Democratic-Republicans, who still formerly just went by Republicans. Luckily for the U.S., the connections French aristocracy made in the 1790s before they left helped smooth passage of the Louisiana Purchase early in the next century, as those same men brokered the deal (more next chapter).

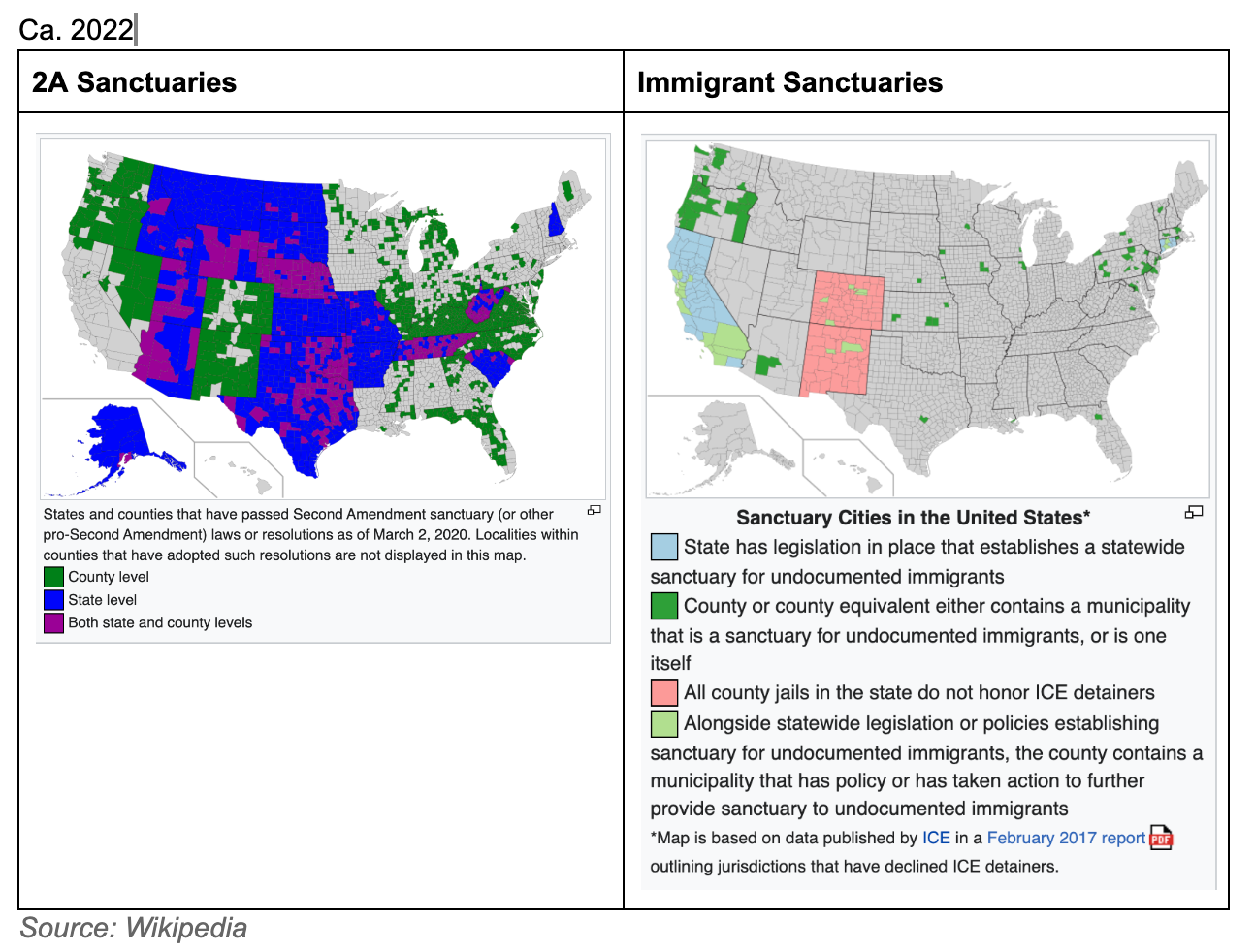

Jefferson and Madison would’ve been jailed themselves had they protested in print, so they wrote anonymously in the Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions. This is the same Jefferson that was signing his name to treasonous manifestos against the British in the 1770s, but in defying the country he’d helped start he couldn’t sign his name. The anonymous Democratic-Republicans argued that states had the right of judicial review over national laws and, if they found a law unconstitutional — in this case, the Alien or Sedition Acts — they could nullify it within their state’s borders, though their final drafts avoided that term, with Madison writing that states could “interpose” to undermine national authority. Nullification Theory, or what Jefferson called “cission,” had radical implications insofar as it would give states ultimate power over the national government, in effect creating a loose union of states with no real top tier. Nonetheless, it was influential in the evolution of states’ rights theory as the country moved toward civil war in the nineteenth century. South Carolina employed it in 1832-33 to oppose tariffs and Massachusetts in the 1850s to oppose the Fugitive Slave Act. Opponents of the 2009 Affordable Healthcare Act (aka Obamacare), such as Texas Governor Rick Perry, revived nullification theory more recently. Today, blue (liberal) and red (conservative) states sue blue and red presidential administrations to resist executive orders, and nullification theory echoes in the “sanctuaries” that defy federal gun laws in red areas (e.g. red flags, background checks) and immigration enforcement or cannabis laws in blue areas. Madison and Jefferson overshot with the Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions, leading to Federalist victories in the 1798 mid-terms even in the South, where zero states signed on to their radical (even secessionist?) states’ rights ideology. But the Federalists had overplayed their hand, as well, and the unpopularity of their Jay Treaty, Whiskey Act, and Alien & Sedition Acts positioned VP Jefferson nicely for another run at the presidency. His 1800 victory defused his states’ rights radicalism, as he was now in control of the national government. But with the Federalists considering using their new army on “Virginians” (Democratic-Republicans) and the Democratic-Republicans defying the national government with the Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions, the young country had been to the brink of civil war in the 1790s.