We’ll start this chapter going way back into ancient “pre-historic” times — partly to provide a backdrop to colonial American history and partly just because “big history” or deep history is interesting and something you should know about as an educated citizen. The text includes places, names, dates, and intricate details just to orient you, but you don’t need to memorize these. Your task is to read actively after going over the 1301 Learning Objectives for this chapter (found under the Chapters-LO’s drop-down above). Don’t stop at very many links. They are there for your general edification if you’re confused about a term or would like to learn more, but you should generally pass over them. You should pay attention to images and maps, though. Always use the arrow down key ↓ instead of the scrollbar when reading online. Also, this is a good time to double-check what class you’ve signed up for. If you’re in 1302 stop reading and start in with the 1302 first chapter on Industry & Technology. Strap on your thinking cap and remember to get up from time-to-time to stretch and drink some water.

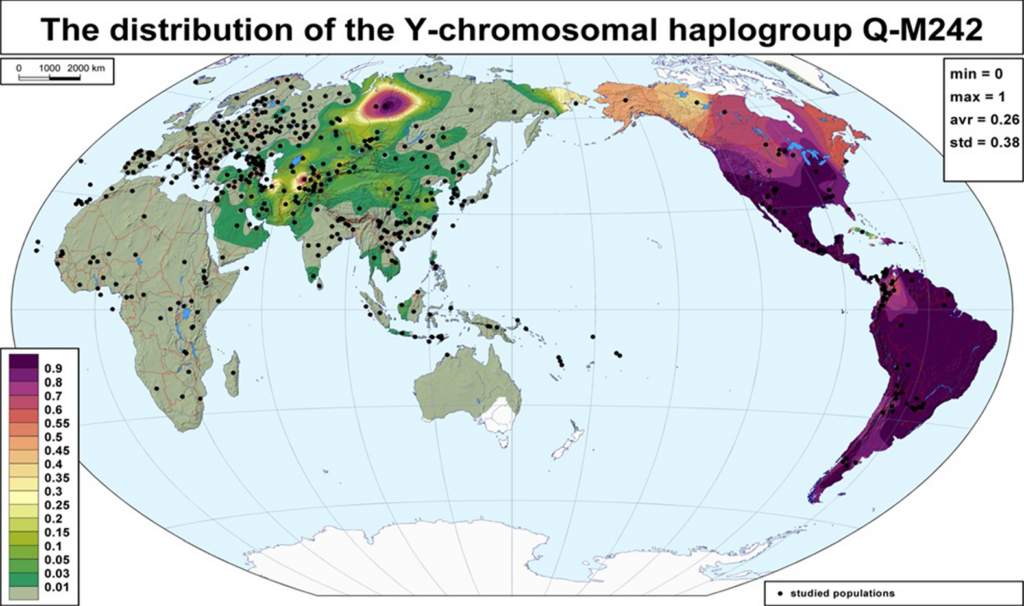

America’s Pre-Columbian era — the 98% of its history that transpired before Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492 — is shrouded in mystery, providing fertile ground for interdisciplinary studies combining history, paleoanthropology, forensic anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics (archaeogenetics combines these). In the early part of this chapter we’ll use these research angles to examine how Asians, the ancestors of today’s Native Americans, first came to America. That question is premised on the idea that humans didn’t originate in America and migrate the other direction or evolve independently in two spots (polygeny). The latter is theoretically possible but exceedingly unlikely given the near-identical DNA of humans everywhere combined with the extreme unlikelihood of any one species coming into being in the first place. If we can safely dismiss that possibility, what about the notion that humanity started in America then migrated to Eurasia? So far, archaeologists have yet to uncover any fossils in the Western Hemisphere remotely as old as those found in Africa, China, and Australia. American fossils only go back around 3% as far as those found in Africa, which is where we still find the most linguistic and genetic ethnic diversity, indicating that’s where people have been the longest.

Archaeologists and physical anthropologists search for ancient remains mainly in drier climates since fossils decompose in moisture. They often use stratigraphy to measure the soil around old skeletons rather than analyze the bones themselves because radiocarbon dating is only accurate back 50k years. Only a small portion of fossils survive worldwide, which is why it’s been so helpful that mitochondrial DNA contains a sort of historical record of our past, with traces of early mutations. Software, in turn, allow for sequencing billions of fragments back into a recognizable double helix while separating it from contaminants like surrounding plant, insect, and bacterial DNA. As this list indicates, the earliest hominin fossil fragments date back 5-7 million years, with the nearly fully intact “Lucy” from 3.2 million years ago and some primate skulls showing enlarged brains from 3.6 million years ago. Archaeologists found most of these bones in the East African Rift, including Kenya and Ethiopia. Recently discovered footprints in nearby Tanzania indicate upright walking as far back as 2.5 million years, and evolutionary anthropologists think these hominids started using fire around that same time.

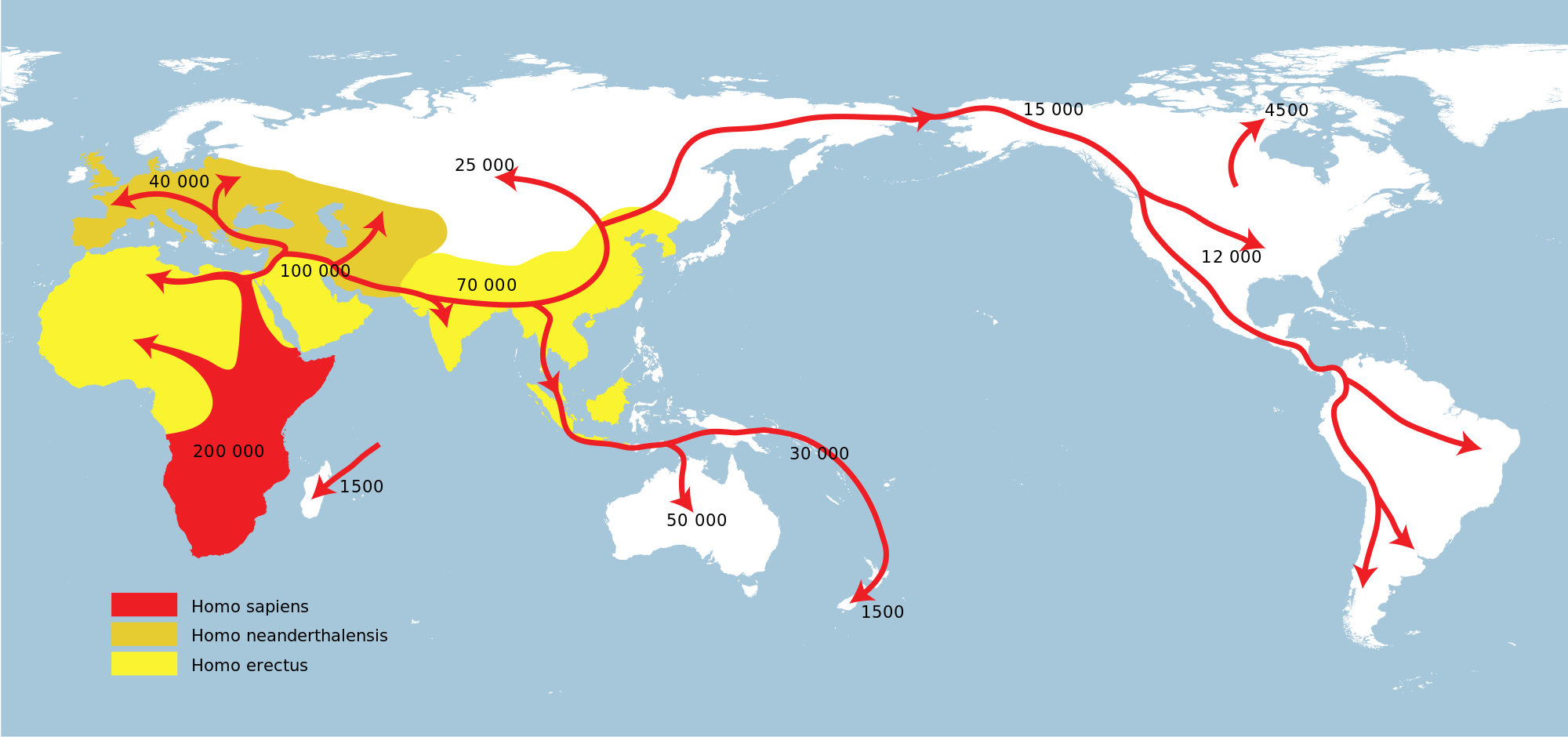

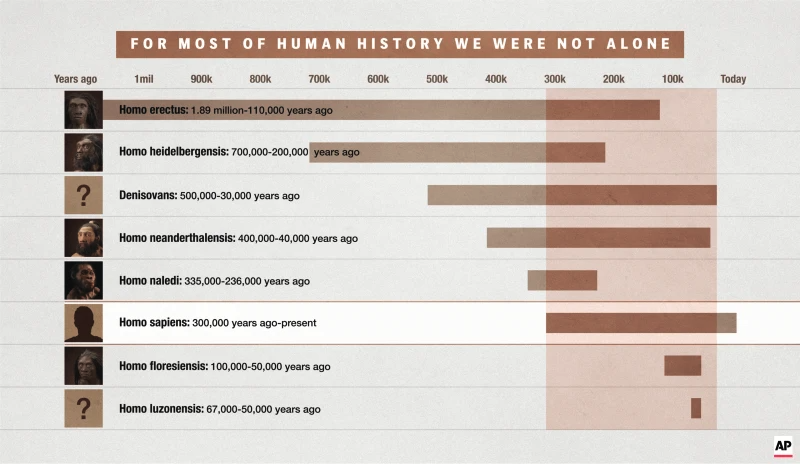

What about “us?” Some archaeologists think that, before humans emerged in their modern form, bipedal hominins migrated from Africa to Asia and Europe ~ 1.8 to 2.1 million years ago (mya), mixing with even earlier Neanderthals (in Europe) and Denisovans (in Asia). Archaeologists call this “Out of Africa 1.” Some archaeologists think these upright men, or Homo erectus (H. erectus), gradually morphed into modern humans, while most think that modern humans migrated out of Africa later as a distinct species. There was interaction with Neanderthals and Denisovans, either way, along with lesser-known hominins and other “ghost species” as yet undiscovered (AP). White blood cells draw their powers of immunity from all these archaic human “cousins” — the more variety the greater the immunity against infections. Geneticists describe inter-breeding as an evolutionary “shortcut” to acquire traits faster than the natural process of mutations. Ed Yong’s optional article below describes other variants that preliminary studies are associating with Neanderthal DNA, most if only slightly.

The earliest African spears and A000 Y-chromosome DNA go back ~ 200k years. Those dates are compatible with the oldest known Homo sapien fossils, discovered in Morocco in 2017, that date to ~300 kya (thousand years ago). Prior to this find, the earliest known fossils were the “Herto Man” bones found in Ethiopia in 2003 that traced to 154-160 kya. Various forms of Homo sapiens likely emerged across Africa and coalesced into what we now think of as humans, with tongues and larynxes suitable for speech/language. While these human ancestors weren’t as fast, strong or well-clawed as much of the game they hunted, they could surround and outlast other animals through teamwork, endurance, and persistence hunting. Sweating gave mostly hairless human hunters an endurance advantage, since furred animals need to rest, panting to release heat and avoid overheating. Ostrich eggs could have provided ancient humans with natural canteens of water, just as they do for modern (African) San hunter-gatherers. Humans can also dive underwater to fish longer than most other mammals. While increasingly large brains and opposable thumbs led to inventing stone tools, those tools and early fish hooks, in turn, provided meat that nourished brains. Fire helped, too, since cooked food releases more energy into the bloodstream than raw food. The development of symbols in language and art helped humans communicate and cooperate with each other and pass down knowledge about how to hunt and fish and which poisonous plants and animals to avoid, especially shellfish, reptiles, and insects. Humans were also the first primates to crack bones to access nutritious marrow. Men were the primary hunters but women and children hunted small game and helped herd, process, and clean larger animals.

Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa into the Middle East, Asia, and Europe, in their case ~ 100-45 kya. Anthropologists call this wave Out of Africa 2. They might have crossed the Sahara Desert by following the Nile River or other now-extinct rivers to the Sinai Peninsula in modern-day Egypt or crossed the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait between modern-day Djibouti/Eritrea and Yemen, likely to escape drought or follow game. In the 1930s, English archaeologists Dorothy Garrod and Dorothea Bate found ten human fossils in caves on Mt. Carmel, Israel that were over 100k years old — to date, the oldest Homo sapien skeletons found outside Africa.

Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa into the Middle East, Asia, and Europe, in their case ~ 100-45 kya. Anthropologists call this wave Out of Africa 2. They might have crossed the Sahara Desert by following the Nile River or other now-extinct rivers to the Sinai Peninsula in modern-day Egypt or crossed the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait between modern-day Djibouti/Eritrea and Yemen, likely to escape drought or follow game. In the 1930s, English archaeologists Dorothy Garrod and Dorothea Bate found ten human fossils in caves on Mt. Carmel, Israel that were over 100k years old — to date, the oldest Homo sapien skeletons found outside Africa.

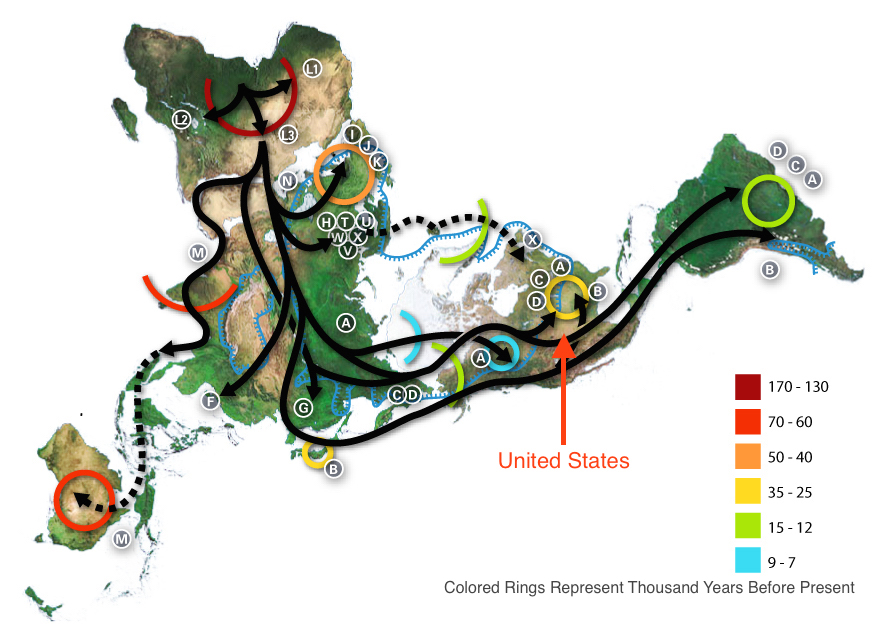

Between 125-65 kya this early human population shrank dramatically during the Great, or Long Bottleneck, with survivors only in Africa. While DNA and fossil evidence support such a contraction, the Bottleneck’s exact timing and cause are still unknown (the Toba eruption theory was one attempt to explain it). Whatever its cause, the Bottleneck triggered another, later migration out of Africa, around 50 kya, when humans spread across Europe, Asia, and Australia during the Late Stone Age, or Upper Paleolithic, taking language, tools, and fire with them. Neanderthals still existed in Europe and interbred with humans, leaving most modern humans with ~ 2% Neanderthal DNA, but Homo sapiens sapiens likely had more developed weapons or brains than H. sapiens neanderthalensis. Sapiens means “wise” or “with mind” but that’s self-branding. More genetic diversity exists today among West African ethnicities left behind than among everyone else who migrated, with the physical traits that differentiate all of us being fairly superficial and recent. Take a moment to study the map at the top of the chapter to get a feel for the overall framework and scope of African migration.

Historians traditionally thought that civilization — if narrowly defined by writing/record-keeping, math, organized religions, governments, and cities — emerged in the Neolithic age with agriculture in the Fertile Crescent (left), especially Mesopotamia (Sumer, in southern Iraq) and Egypt, somewhere between 7-11 kya, with the first written records ~ 5.4 kya. But other agricultural societies with writing grew independently, if later, along the Indus River in India and Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in China, on Crete (Minoan), and in Mesoamerica and Peru (Norte Chico or Caral-Supe). Rather than wheat, as in the Fertile Crescent, Native Americans grew corn, squash, sunflowers, and knotweed. Wheels emerged ~ 3-4 kya when Bronze Age smelting allowed for the metal chiseling of precise joints between the wooden wheel and axle. The Fertile Crescent theory about the origins of civilization is currently being pushed back chronologically, broadened geographically, and complicated by a fuzzier-than-previously-thought distinction between hunter-gatherer and farming societies. Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey is a significant structure, possibly a religious shrine, cut entirely with stone tools dating back 8-9k years BCE (before the common era) and 6k years before Stonehenge. The Talianki site in Ukraine dates to 3.85k BCE, and the Megalithic Temples of Malta from the same era predate the Egyptian pyramids. Archaeologists are discovering new sites all the time and It’s starting to appear that, rather than having a clean break between hunting-gathering and farming, many societies built settlements and practiced some horticulture or seasonal flood-recession farming while still hunting and herding. They likely chose to retain that flexibility because, when game is plentiful, hunting is easier and less time-consuming than farming and less susceptible to environmental problems like drought, flooding, insect plagues, and fire. Fleeing these problems is an advantage of being nomadic. But farming began sometime when Earth warmed after the end of the Last Glacial Period ~ 11.5 kya.

Historians traditionally thought that civilization — if narrowly defined by writing/record-keeping, math, organized religions, governments, and cities — emerged in the Neolithic age with agriculture in the Fertile Crescent (left), especially Mesopotamia (Sumer, in southern Iraq) and Egypt, somewhere between 7-11 kya, with the first written records ~ 5.4 kya. But other agricultural societies with writing grew independently, if later, along the Indus River in India and Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in China, on Crete (Minoan), and in Mesoamerica and Peru (Norte Chico or Caral-Supe). Rather than wheat, as in the Fertile Crescent, Native Americans grew corn, squash, sunflowers, and knotweed. Wheels emerged ~ 3-4 kya when Bronze Age smelting allowed for the metal chiseling of precise joints between the wooden wheel and axle. The Fertile Crescent theory about the origins of civilization is currently being pushed back chronologically, broadened geographically, and complicated by a fuzzier-than-previously-thought distinction between hunter-gatherer and farming societies. Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey is a significant structure, possibly a religious shrine, cut entirely with stone tools dating back 8-9k years BCE (before the common era) and 6k years before Stonehenge. The Talianki site in Ukraine dates to 3.85k BCE, and the Megalithic Temples of Malta from the same era predate the Egyptian pyramids. Archaeologists are discovering new sites all the time and It’s starting to appear that, rather than having a clean break between hunting-gathering and farming, many societies built settlements and practiced some horticulture or seasonal flood-recession farming while still hunting and herding. They likely chose to retain that flexibility because, when game is plentiful, hunting is easier and less time-consuming than farming and less susceptible to environmental problems like drought, flooding, insect plagues, and fire. Fleeing these problems is an advantage of being nomadic. But farming began sometime when Earth warmed after the end of the Last Glacial Period ~ 11.5 kya.

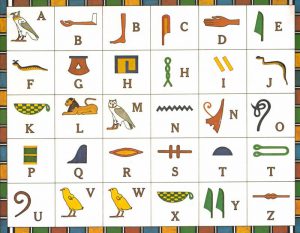

It’s possible, but not proven, that religion and politics may have overlapped insofar as religious sacrifices, especially of bread and beer, morphed into taxes that, in turn, funded early governments. It’s at least likely that grain was used for taxes since it’s tangible, visible (hard to hide), and usually storable. The first known writing comes in the form of Sumerian/Mesopotamian accounting and tax ledgers. Migrants from Canaan working at Serabit el-Khadim in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula transitioned from hieroglyphs to characters that represented sound values, seeding the letters that morphed into the Greek, Latin/Germanic, Hebrew, Arabic, and Tibetan alphabets. Early alphabets were often based on what the beginning of the spoken word represented by an image sounded like, with that image morphing into a letter. Unlike human DNA, writing didn’t have a common origin, but other people like ancient Chinese and Mayans evolved through the same interplay between symbols/marks and sounds via what we’d today call word games or pictograms. This universal pattern of linguistic evolution is called the Rebus Principal, exemplified in the 1865 postcard to the right. The English alphabet has distant roots in Egyptian hieroglyphs, though they’re separated by so many degrees that it’s difficult to see any connection today if you look at the original pictograph and modern letter (left).

A Proto-Indo-European language developed from which most Eurasian languages evolved. Later, groups that domesticated wild horses spread their languages, genes, and diseases at a higher rate than those that migrated on foot. While historians of the ancient world focus on early writing and hieroglyphic records, archaeologists, paleo-anthropologists, geneticists, and linguists rely on artifacts, fossils, soil, DNA and language to uncover how early humans fanned out of East Africa onto the rest of the planet. The advent of radiocarbon dating after 1949 made it easier to date organic material like bones deposited within the last 50k years.

But long before civilization developed in the Fertile Crescent, humans made their way from Siberia to Alaska. It’s unclear exactly how far back Paleo-American history goes or, beyond these early “Indians,” who else visited America without settling in the centuries prior to Christopher Columbus’ voyages to the Caribbean in the late 15th century. Scholars pretty much agree, though, that humans weren’t in the Western Hemisphere prior to 27,000 years ago at the earliest. Sloth-bone pendants found in Brazil in 2023 date from 25-27k years ago, the oldest human ornaments found in the Western Hemisphere. At a minimum, then, humans have been in America since ~ 25 kya, at least 15k years before the traditional dating of civilization in the Fertile Crescent. Today’s Indigenous peoples of the Americas, also known as Native Americans, Amerindians, or American Indians, likely descend from these Paleo-American ancestors, circled in purple on the timeline below.

Paleo-Americans

Colonial Americans saw the physical affinity between Native Americans and Asians — one of the reasons they mistakenly named them Indians as in the South Asian subcontinent — but didn’t know how they arrived in America. Jesuit scholar Jose de Acosta was on the right track as far back as 1590 when he suggested that North America’s proximity to eastern Russia might have provided the vital link to Eurasia. The dominant theory of the past century was that Asians migrated across the Bering Land Bridge (aka Beringia) between Russia and Alaska sometime toward the end of the Last Glacial Period, roughly 11.5k BCE. Bigger cycles called Ice Ages have happened periodically in Earth’s history, and we’re still in one, while glacial periods happen in smaller cycles as Earth’s elliptical orbits around the Sun contract and expand in Milankovitch Cycles. Cold climates provide a precarious existence but have their advantages. Freezing temperatures allowed humans to cross relatively long distances on sledges and nature’s open-air refrigerator allows hunters to kill lots of game at once if they’re skilled and lucky enough to corner a herd. One key invention was the (bone) needle, allowing humans to stay warm by making clothing/shoes and tents out of animal skin, using animal sinew or plant as thread. Hide could even be used instead of wood in boats. Subarctic humans also domesticated grey wolves for pulling dog sleds, an early form of transportation that predated the wheel by 5k years and contributed gradually to the evolution of “man’s best friend.”

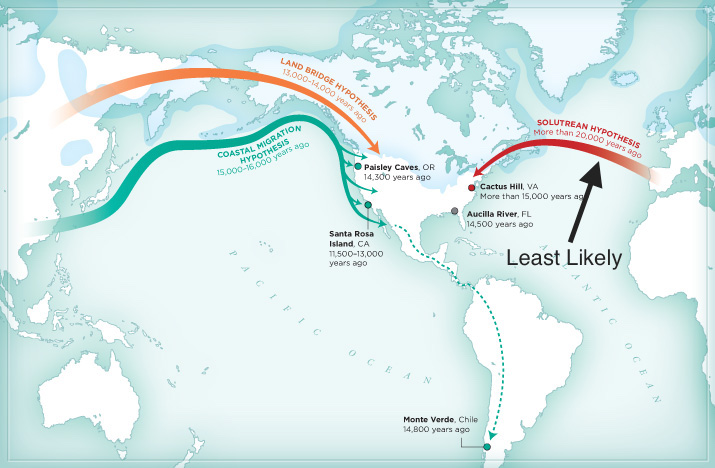

There was near consensus on the Beringia theory as of the 1960s. But in the early 21st century, scholars started to theorize that people came by multiple means in multiple waves — at least three main ones, according to ethnohistorian Donald Fixico — from different places. Beringia Theory hasn’t been overturned in recent decades but rather complicated and expanded. Some studies indicated that the 8.9k BP (before present) Kennewick Man found along the Columbia River in Washington in 1996 and 9.4k BP Spirit Cave Mummy found in Nevada in 1940 more closely resemble the Morori of the Chatham Islands (southeast of New Zealand) or the Jōmon and Ainu of Japan and eastern Russia, respectively, than they do modern Indigenous Americans, at least as far as their skull and bone shapes. Danish scientists who examined the Kennewick skull in 2015 disagreed, arguing that it was most similar to modern Native Americans. This genetic map indicates that most modern Native Americans descend from Paleo-Siberians, but that later groups also migrated to the Arctic.

Like theories on the emergence of farming in the Neolithic, Beringia Theory is being complicated and enhanced but not overturned. Some scholars now suspect that hunters didn’t actually cross a sheet of ice on the Bering Land Bridge but rather an ice-free corridor that opened as the ice retreated. That corridor is now underwater because ocean levels rose when much of the ice worldwide melted. And Paleo-Americans didn’t necessarily have to come by land. They might have skirted the coastline in primitive boats along a nearly continuous “kelp highway” or even sailed the open ocean in good weather. We know that Chumash people lived off the California coast in the Channel Islands (right) up to 13k years ago, proving their familiarity with ocean-going boats. Beringia theory has a wide window of opportunity because the Last Glacial Period, lasted from ~ 115 kya to 11 kya, with maximum coverage between 20-26.5 kya.

Like theories on the emergence of farming in the Neolithic, Beringia Theory is being complicated and enhanced but not overturned. Some scholars now suspect that hunters didn’t actually cross a sheet of ice on the Bering Land Bridge but rather an ice-free corridor that opened as the ice retreated. That corridor is now underwater because ocean levels rose when much of the ice worldwide melted. And Paleo-Americans didn’t necessarily have to come by land. They might have skirted the coastline in primitive boats along a nearly continuous “kelp highway” or even sailed the open ocean in good weather. We know that Chumash people lived off the California coast in the Channel Islands (right) up to 13k years ago, proving their familiarity with ocean-going boats. Beringia theory has a wide window of opportunity because the Last Glacial Period, lasted from ~ 115 kya to 11 kya, with maximum coverage between 20-26.5 kya.

In 2021, archaeologists discovered footprints near White Sands, New Mexico dating back 21-23k years.

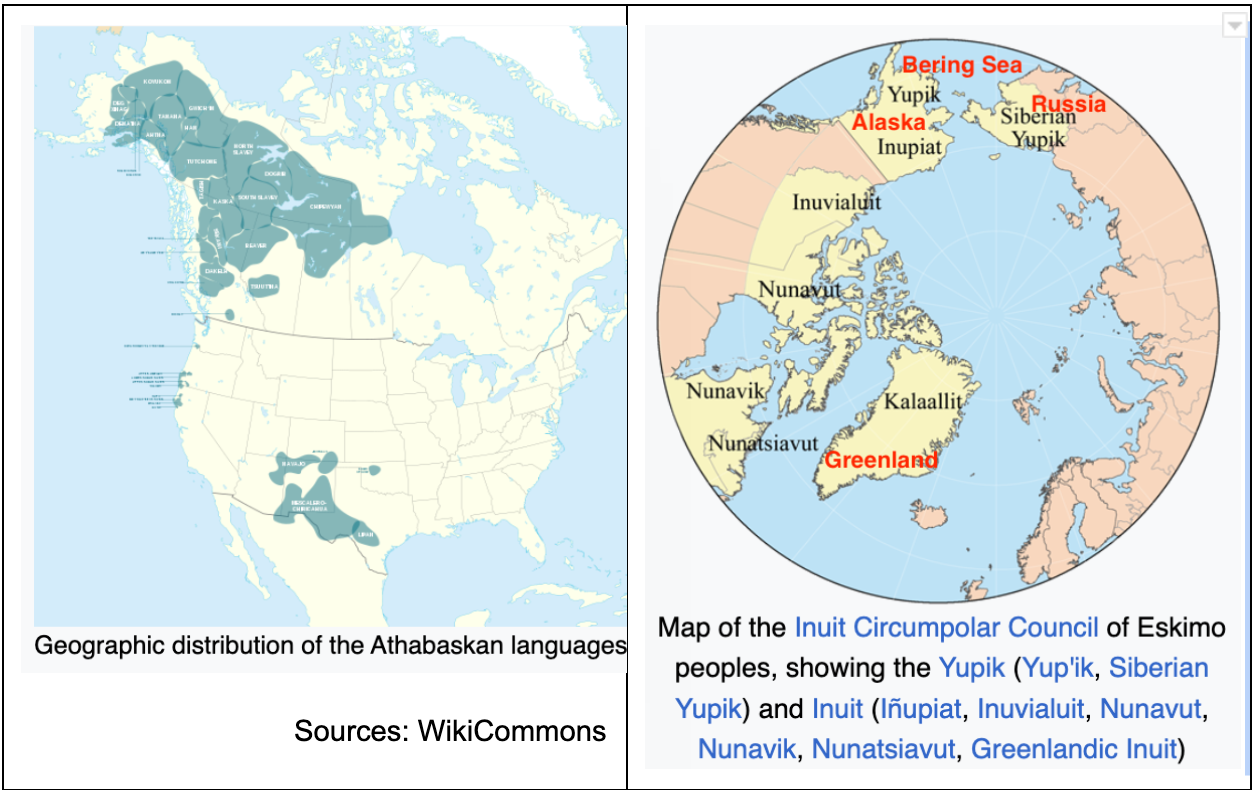

A newer Beringian Standstill theory posits that people may have lived in Beringia for thousands of years before migrating south. Key sites supporting this theory are found among the ice packs of the Yukon Territory that are melting because of climate change. There, archaeologists have found atlatls (spear-throwing levers), arrow-shafts, and human-worked (cut, scratched) fossil remains of horses, bison, and mammoths dating back 24k years. Today’s Dené (Athabaskan) and Yupik/Inuit speakers exhibit DNA admixtures from Chukchi people that migrated later from Siberia. But, so far, scientists haven’t found any Subarctic fossil remains that pre-date the sloth-bone pendants discovered in Brazil in 2023.

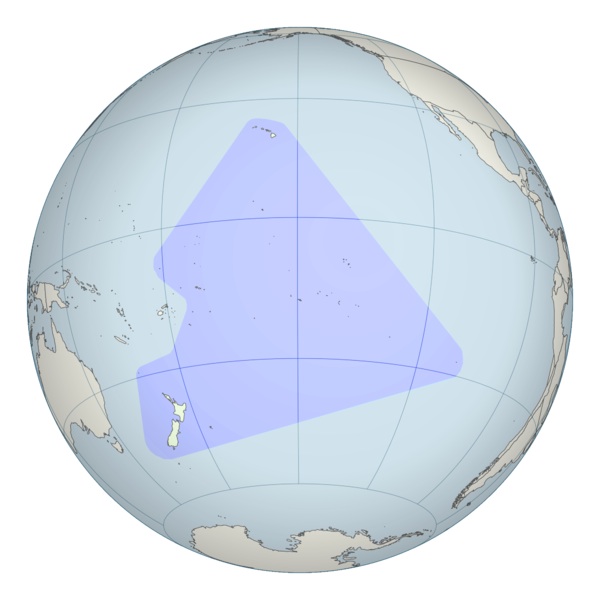

Were ancient people also capable of oceangoing navigation beyond the Chumash’s short trips? We know that medieval Polynesians were, as shown by those intrepid explorers who settled Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, and Easter Island. In 1947, Norwegian anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl demonstrated how a small rudimentary craft could cross the Pacific with his Kon-Tiki voyage, even though historians reject his claim that Polynesia was settled east-to-west by Indigenous Americans rather than west-to-east. But even without Heyerdahl’s experiment, Pacific Islanders had long since demonstrated their navigational expertise in currents, swells, and stars (more below).

Whoever the first Americans were, and wherever they came from, they are known collectively as Paleo-Indians, Paleo-Americans, or sometimes Clovis People after the ancient bison found near Clovis, New Mexico in 1929 with an arrowhead lodged in its bones. Formerly-enslaved cowboy George McJunkin discovered the fossil outside Clovis after a flash flood. Ancient bison (Bison antiquus) were about 30% bigger than modern buffalo and similar fluted projectiles have been found in mastodons (right, more similar to elephants) and wooly mammoths, another animal presumed extinct. The Clovis arrowhead (or projectile) proved the existence of human hunters in America at least 11k years back since that’s when the last incarnations of ancient bison went extinct. Arrowheads don’t carve themselves. After the discovery of several more Clovis Points, archaeologists theorized about the frozen land bridge between Russia and Alaska and looked for new sites, detailed in the optional section below.

Archaeologists are also exploring an Atlantic land bridge to America similar to Beringia. Digging below the Clovis layer, they discovered stone blade tools near Cactus Hill, Virginia similar to Neolithic projectiles being carved in France’s Solutré region from 17-22 kya. These could be examples of convergence: two things, especially simpler objects, being made independently that happen to look the same or operate in the same way. Arrowheads, after all, aren’t complex. Still, the same glaciation that created land bridges from America to Asia could have frozen a bridge between America and Europe, connecting Greenland, Iceland, Ireland, and Nova Scotia. That’s led some archaeologists to entertain the Solutrean Hypothesis of ancient European migration to America ~ 21 kya. Other artifacts found in the Chesapeake Bay suggest the same. It’s a politically volatile theory because today’s Native Americans would be reluctant to embrace the idea that Europeans inhabited the Americas prior to the Vikings in the Middle Ages, while alt-right white nationalists surely would, though the ancient groups could’ve mixed without conflict or never interacted and whatever happened, if anything, would’ve been so long ago as to be virtually irrelevant to our understanding of post-1492. Amerindians’ claim to being America’s first inhabitants is the political subtext of the scientific debate, whereas arrowheads and glaciations are the text. In this case, the Solutrean Hypothesis isn’t strong as of yet, anyway. Archaeologists haven’t discovered the fossil remains of any ancient Caucasians in eastern North America and tool evidence is weaker than Pacific theories, with far fewer European-style arrowheads and none lodged in mastodons, mammoths, or ancient bison. However, some X2 mtDNA from the Near East, Caucuses, and southern Europe is found in both ancient and modern Indigenous Americans, especially Ojibwe, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Siouan tribes. In history as in science, we follow the evidence wherever it leads us, and Oppenheimer’s optional article below suggests it’s too soon to close the book on the Solutrean theory, though this DNA could’ve arrived from the Pacific route.

Who Came Next?

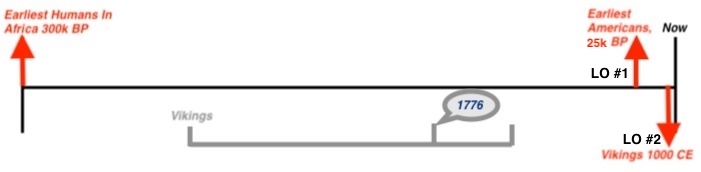

We’ll now move up the timeline from the Stone Age history thousands of years ago to the past 1000 years. In the graph above, we’ve been looking in previous sections at the earliest humans in Africa on the far left, and earliest Americans dating from ~ 25k BP. You should now be transitioning from Learning Objective 1:1 to LO 1:2.

We are shifting from the earliest Americans ~ 25 kya up to the Vikings around a thousand years ago (right, blue arrow). It doesn’t look like a big space on a timeline that stretches as far back as 300 kya, but it’s a long time. For perspective, if you imagine how long ago Jesus lived in the Roman Empire; 12x as long transpired between Siberian-Asian tribes making their way to Alaska and Scandinavian Vikings fishing off Canadian shores. The tiny space between the Vikings and present (now) expands to the grey timeline beneath the black, which includes the founding of the United States in 1776.

We are shifting from the earliest Americans ~ 25 kya up to the Vikings around a thousand years ago (right, blue arrow). It doesn’t look like a big space on a timeline that stretches as far back as 300 kya, but it’s a long time. For perspective, if you imagine how long ago Jesus lived in the Roman Empire; 12x as long transpired between Siberian-Asian tribes making their way to Alaska and Scandinavian Vikings fishing off Canadian shores. The tiny space between the Vikings and present (now) expands to the grey timeline beneath the black, which includes the founding of the United States in 1776.

Long after Paleo-Indians first arrived in America, who came next? One of the intriguing things about early American history is the soft and circumstantial evidence for Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact: stories of people who arrived long after Paleo-Indians but shortly before Christopher Columbus and the Spanish colonized the Caribbean. They point to purported African, (modern) Asian, and European influence in the Americas prior to 1492. Most of these theories aren’t persuasive enough to convince a broad audience, but collectively they suggest that we might not know all there is to know. Some of these theories are fodder for late-night documentaries, while others are academic but haven’t attained a consensus view. One theory — that Scandinavian Vikings built settlements on the northeastern coast of Canada around 1000 C.E. — is widely accepted as fact. Historiography, the study of history, is an ongoing argument. Recent books have argued less persuasively for Chinese explorations of the Americas in the early 15th century and African exploration of eastern South America in the late Middle Ages. Scholars are skeptical about the Chinese theory. Early Ming Dynasty-Chinese had the technological wherewithal in the early 15th century for trans-Pacific voyages, but their famous commander Zheng He made no mention of America in his otherwise thorough navigational writings. Diffusionist scholars point to similarities between ancient African art and that of certain American Indians like the Olmec.

Other theories are seemingly fables from popular culture or driven by political agendas. Let’s examine some of these fringe theories first before looking at more promising scholarship concerning Polynesians and Vikings, because it’s important to be able to distinguish between convincing and unconvincing scholarship. Ancient Welsh and Irish legends tell of trips across the Atlantic in the Middle Ages. Mandan Indians of the upper Missouri River supposedly shared some language and physical traits with the Welsh and even built similarly styled boats. At least that was the theory of Brits making claims to the West that predated Spanish claims, including Welshman John Dee, an advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. The agenda fueling their theory was the English rivalry with Spain for control of North America. Fishermen from Bristol, England likewise claimed to have been fishing off the North American coast before Columbus and keeping their grounds a secret, but they didn’t mention it until after Columbus. Some theorists connected a mysterious tower in Newport, Rhode Island to the medieval Scottish Knights Templars (affiliated with Freemasons), but carbon dating suggests it was built in the 17th century, after Puritans came to New England. One pattern you’ll pick up on if you investigate fringe theories is that the Knights Templar and Masons seemed to have their hand in everything, similar to today’s George Soros conspiracy theories. Others connect Templars and 14th-century Scottish/Norwegian nobleman Henry Sinclair to North American Expeditions (including Oak Island) and point to the striking similarity between the Templars’ flag and that of the Mi ‘ kmaq Indians. Finally, the Book of Mormon tells of one of the Lost Tribes of Israel coming to the Americas and being wiped out by Indians; but there’s no convincing archaeological evidence to suggest that. Someone in ancient times mined large amounts of copper from the Great Lakes region and some suggest that Europeans mined it to combine with tin to make bronze. However, there’s no evidence from Europe indicating that they came to America during the Bronze Age and more recent scholarship shows that Indians mined the copper themselves for their own use.

The Kensington Runestone a 19th-century Minnesota farmer purportedly hit with his plow had Norse inscribed on it, meaning, if authentic, that Scandinavians explored as far inland as the Midwest. The legend held enough water, at least, for Minnesota’s NFL team to name themselves the Vikings, but it turned out to be a hoax. The farmer, Olof Öhman, was Swedish and hoped to spin Scandinavians as the first American immigrants to offset discrimination. The Newberry Tablet found in Michigan in 1896 was another such purported artifact, in that case with (Greek) Minoan symbols. In 2010, amateur archaeologists pulled a 500-pound rock carving from the Arkansas River near Tulsa, Oklahoma with an Apis bull on it similar to those etched in ancient Egypt. Nearby caves contain Ogham carvings. Ogham is a Celtic Irish dialect used from the 4th-10th century CE (Common Era). Drawings in the Anubis Cave on the Oklahoma Panhandle are either a hoax or an important early Celtic-American ruin. They exhibit shadow plays during the seasonal equinoxes. A state history museum in Lansing houses over 3k Michigan Relics of purported Near Eastern origin “discovered” from 1890-1920 that academic scholars deem as hoaxes.

Recently, explorers discovered a Runic tombstone with 12th-century English characters in a cave in the Mustang Mountains of southern Arizona. Like the other artifacts, it doesn’t reveal obvious, telltale signs of being a hoax, but there’s no solid evidence from Welsh, Minoan, Celtic, or medieval English history of overseas explorations. There are some hints of Welsh explorers sailing across the Atlantic from Wales, but nothing definitive. It’s probable that Irish explorers made it to Iceland, but no further. Whatever happened in the Middle Ages, it seems that Indigenous Americans were unfamiliar with European civilization when the Spanish arrived on the American mainland in the early 16th century. It’s plausible that some Europeans or Africans sailed to the Western Hemisphere earlier and just never returned to report what they discovered, but that’s pure conjecture. Other than the Vikings, these pre-Columbian theories are suggestive or entertaining but count as fringe theories or pseudo-archaeology. Some of them might pan out later, but let’s not confuse them with scholarship that relies on more stringent standards of evidence. Be open-minded but not soft-minded.

Better evidence suggests that Polynesians (and possibly Japanese) visited the western coasts of the Americas and that Scandinavian Vikings fished off the northeastern coasts of what’s now Canada. DNA analysis of Chileans and Ecuadorians shows some common traits with Japanese, supporting an earlier theory based on similarities between Andean and Jomon (medieval Japanese) pottery. The Zuni language of Arizona has traits similar to Japanese.

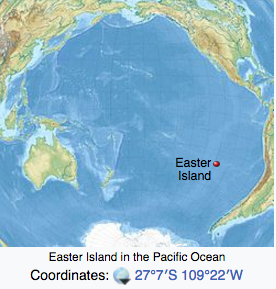

Scattered but increasingly convincing evidence indicates Polynesian contact with the Western Hemisphere. As mentioned above, we know that medieval Pacific Islanders sailed over a vast portion of the ocean around the 11th-13th centuries CE. They could even tack into the wind on long dugout canoes with outriggers and eventually sailed with double-hulled catamarans. Some archaeologists think Polynesians first settled Hawaii as far back as the 3rd c. CE while most think it was later, around 1200 CE. The last island Polynesians settled was Easter Island in the southeastern Pacific. If they could make it from Marquesas Islands-Tahiti-Bora Bora-Raiatea to Hawaii and Easter Island, Polynesians could’ve reached the Western Hemisphere — what medieval Hawaiians called the “land of mist and frogs.” Easter Island is just 2k miles west of Chile. For perspective, Easter Island (109°22′W) is east of Phoenix, Arizona (112°04′W), even though the map on the right doesn’t suggest that because of its particular angle.

Scattered but increasingly convincing evidence indicates Polynesian contact with the Western Hemisphere. As mentioned above, we know that medieval Pacific Islanders sailed over a vast portion of the ocean around the 11th-13th centuries CE. They could even tack into the wind on long dugout canoes with outriggers and eventually sailed with double-hulled catamarans. Some archaeologists think Polynesians first settled Hawaii as far back as the 3rd c. CE while most think it was later, around 1200 CE. The last island Polynesians settled was Easter Island in the southeastern Pacific. If they could make it from Marquesas Islands-Tahiti-Bora Bora-Raiatea to Hawaii and Easter Island, Polynesians could’ve reached the Western Hemisphere — what medieval Hawaiians called the “land of mist and frogs.” Easter Island is just 2k miles west of Chile. For perspective, Easter Island (109°22′W) is east of Phoenix, Arizona (112°04′W), even though the map on the right doesn’t suggest that because of its particular angle.

There is genetic, nutritional, archaeological, and linguistic evidence that Polynesians reached the Western Hemisphere. Polynesian DNA has shown up among the Mapuche of Chile and Argentina and a now-extinct Brazilian tribe. Geneticists caution that contact may have occurred later among enslaved workers captured from different parts of the world. But Polynesian-South American contact would also explain how the sweet potato arrived in Hawaii and Easter Island (or vice-versa) and why the Hawaiian word for the vegetable, Kumara, is so similar to that used in Ecuador and Peru: Kumar. Moreover, archaeologists unearthed Polynesian chicken bones in South America. Recently, geologists matched a Hawaiian obsidian arrowhead with rock from Pachuca, in southern Mexico, not otherwise present in Hawaii. Around the 13th century, the aforementioned Chumash of California started using Polynesian fish-hooks and building distinctly Hawaiian-style canoes. Finally, more conclusive DNA research conducted in 2020 indicated that Polynesians mixed with Native South Americans sometime around 1200 C.E. (Stanford Medicine News Center). There’s mounting evidence, in sum, for pre-Columbian contact between Polynesia and mainland America.

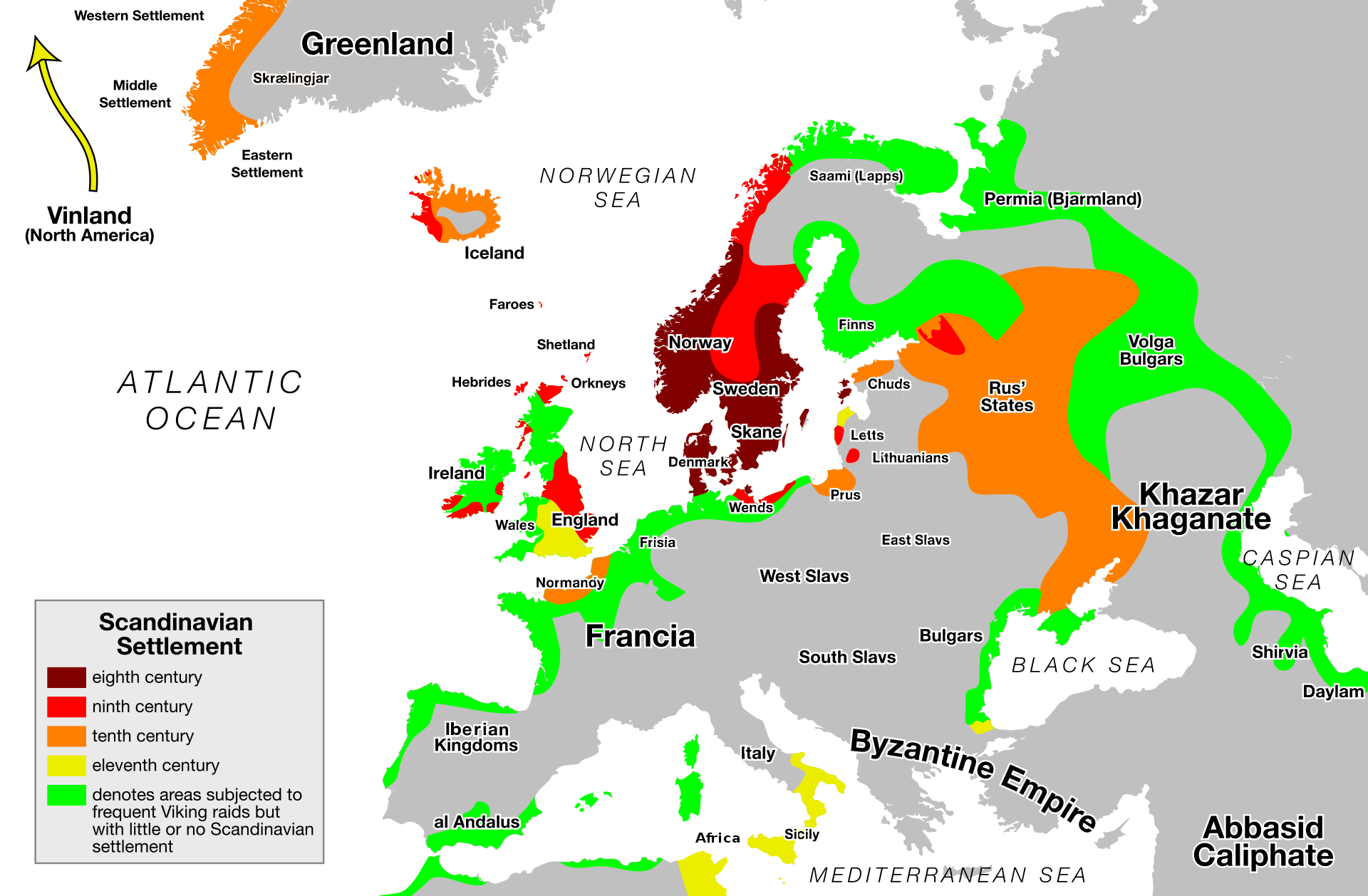

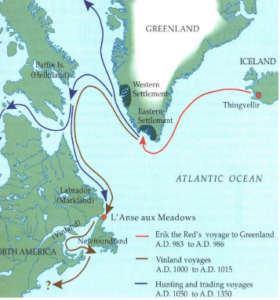

The first Europeans we can definitively say came to the Western Hemisphere were Scandinavian Vikings, who fished off of what’s now the northeastern coast of Canada in the Middle Ages. Vikings traded as far south as Asia Minor (Turkey) and conquered much of northern Europe and Britain (above). They settled Iceland and a smaller group of a couple thousand farmed and hunted for valuable walrus tusk ivory in the southern part of Greenland from ~ 900 to 1500 CE, disappearing for reasons archaeologists still debate (they’d already hunted walruses into extinction on Iceland). King Olaf I of Norway (r. 995-1000) sent “Leif the Lucky” to Greenland to spread Christianity. According to the 13th and 14th-century Sagas of Icelanders, Bjarni Herjólfsson sighted North America in 986 CE when lost and he might have visited Baffin Island (Nunavut Territory), where archaeologists found masks and paintings depicting Caucasians along with Viking tools and yarn fragments. Vikings named and perhaps even mapped Markland (southern Labrador), Helluland (Baffin Island), and Vinland (probably Novia Scotia). According to the Sagas, Leif Erikson — son of Erik the Red, whom Greenlanders banished on multiple murder charges — settled Vinland in the late 10th or early 11th c. CE, so named because they found wine grapes there.

The first Europeans we can definitively say came to the Western Hemisphere were Scandinavian Vikings, who fished off of what’s now the northeastern coast of Canada in the Middle Ages. Vikings traded as far south as Asia Minor (Turkey) and conquered much of northern Europe and Britain (above). They settled Iceland and a smaller group of a couple thousand farmed and hunted for valuable walrus tusk ivory in the southern part of Greenland from ~ 900 to 1500 CE, disappearing for reasons archaeologists still debate (they’d already hunted walruses into extinction on Iceland). King Olaf I of Norway (r. 995-1000) sent “Leif the Lucky” to Greenland to spread Christianity. According to the 13th and 14th-century Sagas of Icelanders, Bjarni Herjólfsson sighted North America in 986 CE when lost and he might have visited Baffin Island (Nunavut Territory), where archaeologists found masks and paintings depicting Caucasians along with Viking tools and yarn fragments. Vikings named and perhaps even mapped Markland (southern Labrador), Helluland (Baffin Island), and Vinland (probably Novia Scotia). According to the Sagas, Leif Erikson — son of Erik the Red, whom Greenlanders banished on multiple murder charges — settled Vinland in the late 10th or early 11th c. CE, so named because they found wine grapes there.

These Viking settlers and explorers were illiterate, explaining the lack of primary sources dating from the 10th and 11th centuries. Yet the same 13th-century Sagas stories appeared first in German-born Adam of Bremen’s Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg (1073-1076). For years, historians considered the Deeds and Sagas mythological tales but they’re both told in a matter-of-fact tone, with no sense that the authors are spinning what they consider an extraordinary tale or accomplishment. Then, in 1960, archaeologists uncovered a small Viking village on the northern tip of Newfoundland. The sod longhouses Vikings built at L’Anse aux Meadows (pronounced Lance-a-Meadows) used the same construction and nails as Vikings built in Iceland and Greenland around 1000 CE. The blacksmith who made the nails used an iron smelting furnace built in the same circular fashion lined with clay as those in Iceland and Norway. Indians didn’t forge iron or make the kind of Viking armor discovered at L’Anse aux Meadows. In 1968, they discovered a distinctly Norse-style bronze pin and bone needle. They also found a stone oil lamp and boat repair shop with worn rivets. There’s too much detail there in common with Viking technology for it to be an example of (coincidental) convergence.

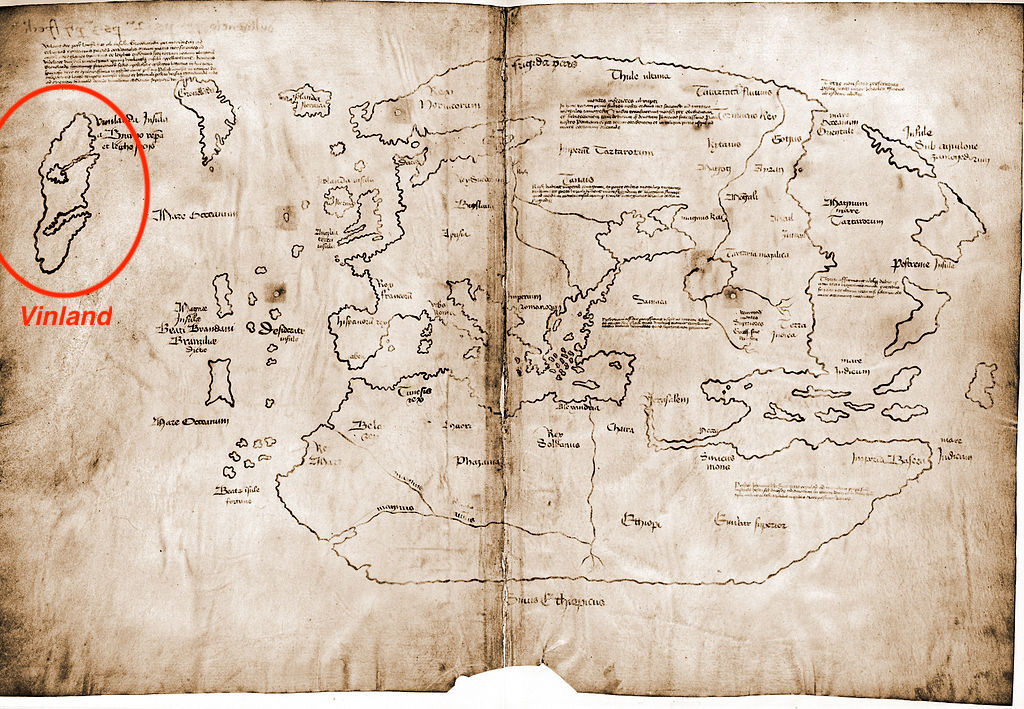

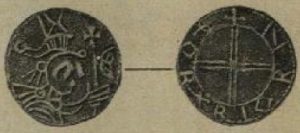

Vikings abandoned L’Anse aux Meadows, though the controversial and unauthenticated Vinland Map (above) purchased by Yale University in 1957 and carbon-dated to 1450 CE suggests that Vikings settled somewhere in Vinland for over a century and were acknowledged by the Catholic Church that even sent a bishop to America — the same Church that backed Columbus’ claim to discover America. The Sagas also say that Vikings explored the coast and built one to three more settlements at Vinland, but Indians they called Skræling (likely Mi’kmaqs) repulsed them and they left. But other than the disputed Kensington Stone (almost surely a hoax), there’s no evidence that Vikings settled further inland, let alone anything as far west as Minnesota. There is evidence that Vikings returned to North America from time-to-time in the Middle Ages to trade woolen textiles for animal pelts. One Viking coin, the Maine Penny matching that on the upper right, was discovered in what’s now northern Maine but, if real, was likely “trickle-traded” down the coast by Indians. Most scholars think that Yale’s Vinland Map, despite the age of the paper, is a forgery based on its ink, an overly accurate outline of Greenland (the northern coast of which hadn’t been explored by the 15th century), and the fact that Europeans didn’t seem to have any clue about America prior to Columbus mapping the Caribbean in 1492. Future archaeological digs, aided by satellites and LIDAR, might tell us more about the extent of Viking settlements in North America.

Vikings abandoned L’Anse aux Meadows, though the controversial and unauthenticated Vinland Map (above) purchased by Yale University in 1957 and carbon-dated to 1450 CE suggests that Vikings settled somewhere in Vinland for over a century and were acknowledged by the Catholic Church that even sent a bishop to America — the same Church that backed Columbus’ claim to discover America. The Sagas also say that Vikings explored the coast and built one to three more settlements at Vinland, but Indians they called Skræling (likely Mi’kmaqs) repulsed them and they left. But other than the disputed Kensington Stone (almost surely a hoax), there’s no evidence that Vikings settled further inland, let alone anything as far west as Minnesota. There is evidence that Vikings returned to North America from time-to-time in the Middle Ages to trade woolen textiles for animal pelts. One Viking coin, the Maine Penny matching that on the upper right, was discovered in what’s now northern Maine but, if real, was likely “trickle-traded” down the coast by Indians. Most scholars think that Yale’s Vinland Map, despite the age of the paper, is a forgery based on its ink, an overly accurate outline of Greenland (the northern coast of which hadn’t been explored by the 15th century), and the fact that Europeans didn’t seem to have any clue about America prior to Columbus mapping the Caribbean in 1492. Future archaeological digs, aided by satellites and LIDAR, might tell us more about the extent of Viking settlements in North America.

The geographic scale of Viking expansion puts a different spin on the traditional view of medieval Europe as landlocked until, suddenly, there was an Age of Exploration. But, neither Vikings, Polynesians, nor anyone else who came from (modern) Asia, Africa, or Europe made a significant impact on the Western Hemisphere until the Age of Exploration. Spanish colonization starting in 1492 signaled the disruption of Pre-Columbian America when conquistadors settled the Caribbean and mainland stretching from Peru to the present-day American Southwest. We’ll cover that in Chapter 3 but, for now, let’s examine what Europeans of all nationalities encountered when they landed in the New World and vice-versa.

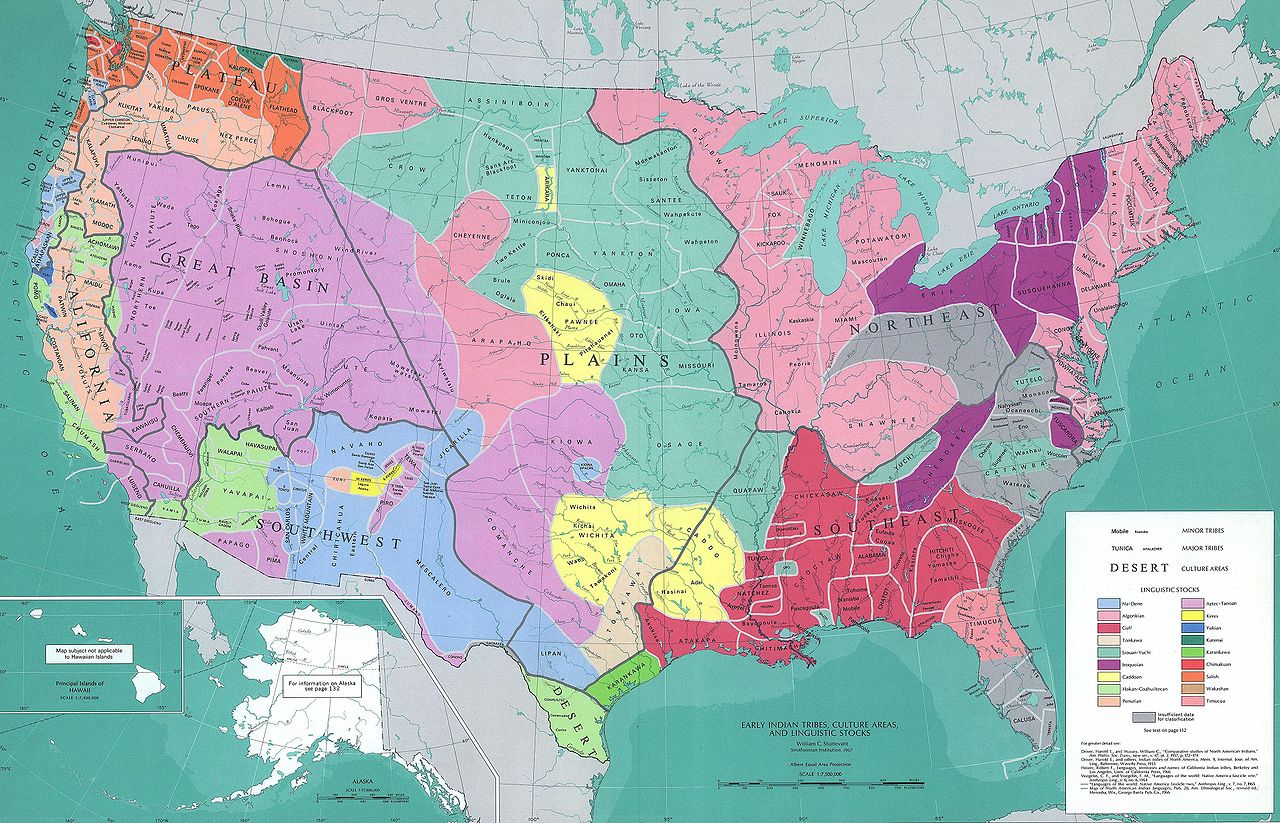

1491

Europeans didn’t encounter Indigenous Americans that defined themselves as a single group, but rather thousands of different tribes with different names, languages, religions, clothing, economies, and traditions. Some tribes, like the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux formed alliances and learned each others’ languages, while others communicated via sign language. But, if Amerindians had been a single group, they could’ve easily warded off the (initially) small number of European invaders even without guns. Instead, many tribes defined themselves in opposition to each other and many along the coast initially viewed Whites, if warily, mainly as potential trading partners.

Historians know little about the Indians who inhabited America before 1492 because so much of their history was lost or disregarded and most of their buildings were biodegradable. Most lived in oral cultures that passed on stories and religions but nothing in the form of written evidence. Consequently, the study of pre-Columbian America has come more under the rubric of anthropology/folklore studies and archaeology than history, because historians tend to prefer written evidence. The best histories though, in this case, are oral.

Smaller nomadic groups traveled seasonally, hunting game, while larger, farming societies built monuments and cities rivaling those of the “Old World.” Despite this diversity, some general trends held across the Americas. Most religions were polytheistic, meaning that Indians worshiped multiple Gods, similar to many societies around the world (including Classical Greeks and Romans), but different from the monotheism of the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition. Native American religions revered all living things along with the sky, wind, and stars — a form of pantheism. Some tribes cast teenage boys into the wilderness, where sensory deprivation caused by hunger, cold or narcotics created a hallucinatory state in which the dreamer encountered his spiritual identity. The spirit purportedly took the form of an animal or an inanimate object like a rock, tree or lightning. The young man would take a new name from this Manitou, as the Algonquians called it, and pray to it at important or transitional times such as war, big hunts or marriage. Most tribes, though, had other guides, totems, or messengers instead of spirit animals.

Oftentimes the most revered religious figure in a tribe was either a shaman (medicine man) or, among farmers, an astronomer, who was responsible for keeping the calendar critical to survival for planting and harvesting. The field of archaeoastronomy studies the way people around the world marked the heavens to keep time and the Americas include several good sites. In New Mexico, Chaco Canyon’s Great Kiva marks solstices, equinoxes and eclipses, and several of Chaco’s buildings orient to solar, lunar and cardinal directions. Central American cities also aligned geographically so as to underscore their inhabitants’ relationship with the cosmos.

Most farming societies were in the fertile area of Mesoamerica, especially the areas around modern Mexico (the Toltec, Maya, and Aztec), Peru (Inca), and, to a lesser extent, around the Amazon River. In Mexico, an unknown group of perhaps ~ 125k centered around Teotihuacan as far back as 2k years ago, overlapping with the Roman Empire in Europe. With its Pyramid of the Moon and Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan was then one of the biggest cities in the world. Native American farming laid the foundation for modern American agriculture as Indians grew increasingly better strains of corn (maize) and potatoes over centuries that Whites later adopted. Selective breeding at least, if not outright genetically modified organisms (GMOs), predates industrialized agriculture.

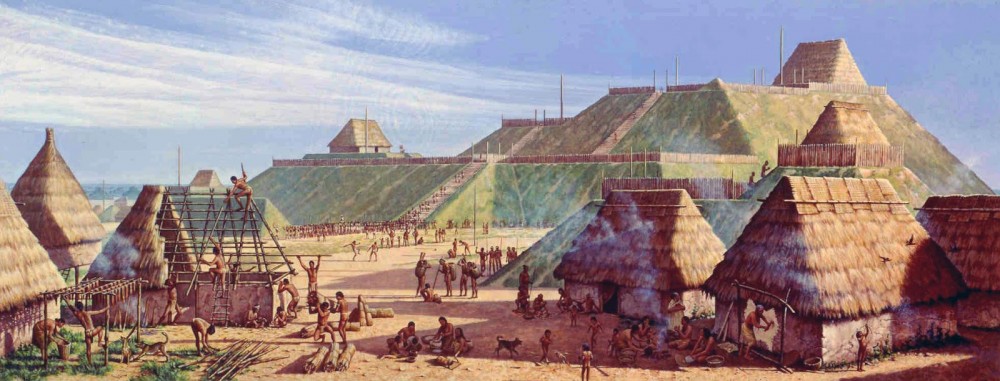

In the last century, archaeologists have discovered similar, if smaller, mound-building cultures in the present-day U.S., in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys. Most prominent among these is Cahokia, a settlement south of present-day St. Louis that had around 10k inhabitants. Currently being excavated with the help of drones, Cahokia was aligned with the movement of the Moon and Sun and included dozens of plazas, markets, sports fields, and religious sites. Cahokians likely traded with Mayans based on how they grew corn and some human fossil remains with notched teeth in the Mesoamerican style.

Poverty Point in northeastern Louisiana is another major mound site, dating from 1700-1100 BCE. What confused early explorers and later historians was that the most densely populated indigenous villages were the ones most likely to have been wiped out by European diseases before Whites ever saw them. These diseases moved along trade routes, passed by Indians who contracted them from Europeans along the coasts. Smaller nomadic bands, on the other hand, sometimes dodged epidemics and survived to meet Whites when they later made their way inland.

Columbian Exchange

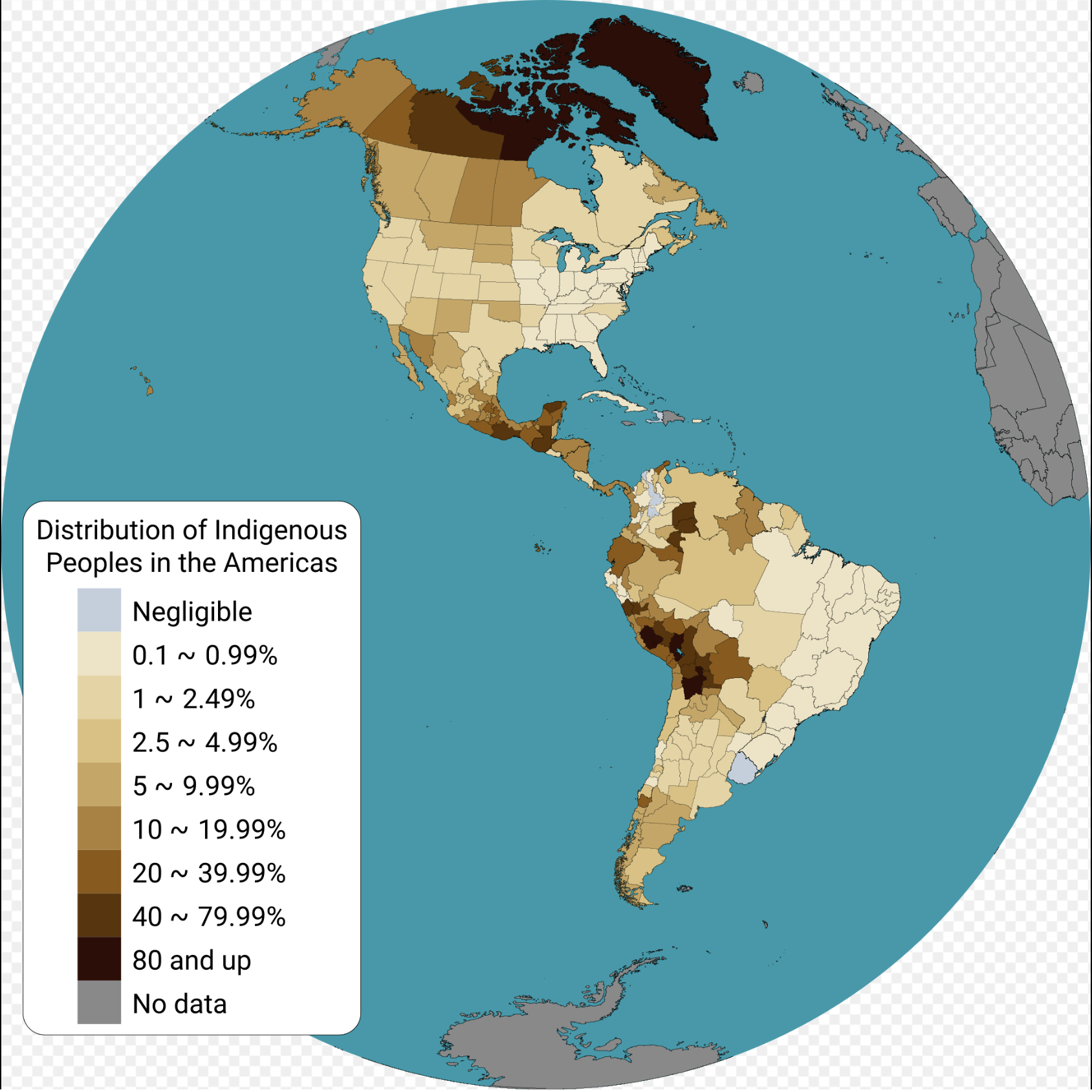

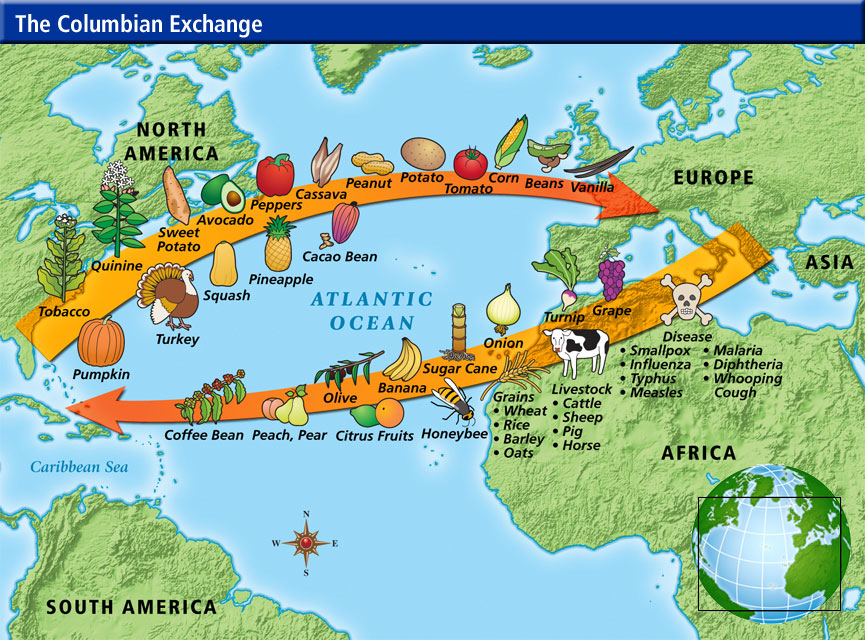

Humans were not all that crossed the Atlantic during the Age of Exploration. Diseases, plants, and animals all transformed both hemispheres so dramatically that neither would be recognizable today in its pre-Columbian form. These transactions are known as the Columbian Exchange, after the title of a 1972 book by University of Texas historian Alfred Crosby.  Even more so than usual after 1492, biology wove its way into history as profoundly as the actions of politicians, theologians, chiefs, shamans, or generals. Though the Columbian Exchange included some traded items, it doesn’t refer so much to the normal trading of commodities as the incidental biology that went along with that trade. Disease is most important. American Indians, being isolated from Europeans, Africans, Middle Easterners, and Asians for thousands of years on separate continents, hadn’t built up immunities to most Old World illnesses (including smallpox, measles, cholera, typhoid, malaria, Bubonic plague, influenza, and common colds). Consequently, they suffered their effects at a disproportionate rate. Some estimates are as high as 60-90% of native populations killed in the centuries following Columbus’ arrival, but we’ll probably never know even a rough approximation of the New World population in 1491. Historian Ned Blackhawk estimates that North America’s overall population nearly halved between 1492 and 1776 (the U.S. founding), from 7-8 million to 4 million.

Even more so than usual after 1492, biology wove its way into history as profoundly as the actions of politicians, theologians, chiefs, shamans, or generals. Though the Columbian Exchange included some traded items, it doesn’t refer so much to the normal trading of commodities as the incidental biology that went along with that trade. Disease is most important. American Indians, being isolated from Europeans, Africans, Middle Easterners, and Asians for thousands of years on separate continents, hadn’t built up immunities to most Old World illnesses (including smallpox, measles, cholera, typhoid, malaria, Bubonic plague, influenza, and common colds). Consequently, they suffered their effects at a disproportionate rate. Some estimates are as high as 60-90% of native populations killed in the centuries following Columbus’ arrival, but we’ll probably never know even a rough approximation of the New World population in 1491. Historian Ned Blackhawk estimates that North America’s overall population nearly halved between 1492 and 1776 (the U.S. founding), from 7-8 million to 4 million.

Conversely, syphilis and tuberculosis might have made their way from America onto the Eurasian continent for the first time, killing millions over the succeeding centuries before penicillin and other cures were developed. Recent research from Pompeii, Italy indicates that European syphilis might have pre-dated American contact. Syphilis is difficult to track because it went by so many names. The English called it “French Disease,” the French called it “Naples Disease,” and Russians called it “Polish Disease.” Syphilis, it seems, was a disease most often contracted when away from home. New diseases had hit Europeans before, when the opening of the Silk Road to Asia (Chapter 2) brought plague-carrying fleas west.

During the Columbian Exchange, Europeans introduced horses, cattle, pigs, and sheep into America, themselves incubators of infectious diseases (e.g. pigs carry influenza). In the case of horses, they were re-introduced, since they’d existed in America up until around 10 kya. Horses might have migrated across the same Bering Land Bridge as humans, except in the opposite direction. Their lack of horses was likely one reason why Mesoamerican empires like those of the Incas and Aztecs were smaller geographically than Old World counterparts like the Roman, Greek (Alexandrian), and Chinese (Mongol). Horses figure prominently in the first known cave art from ~ 35 kya (right), from Chauvet Cave in southeastern France, and were first domesticated in central Asia (present-day Kazakhstan) ~ 6 kya.

During the Columbian Exchange, Europeans introduced horses, cattle, pigs, and sheep into America, themselves incubators of infectious diseases (e.g. pigs carry influenza). In the case of horses, they were re-introduced, since they’d existed in America up until around 10 kya. Horses might have migrated across the same Bering Land Bridge as humans, except in the opposite direction. Their lack of horses was likely one reason why Mesoamerican empires like those of the Incas and Aztecs were smaller geographically than Old World counterparts like the Roman, Greek (Alexandrian), and Chinese (Mongol). Horses figure prominently in the first known cave art from ~ 35 kya (right), from Chauvet Cave in southeastern France, and were first domesticated in central Asia (present-day Kazakhstan) ~ 6 kya.

Buffalo, rattlesnakes, llamas, and catfish had never been seen in Europe (and became novelty items as exotic pets) while rats, bees, cats, and earthworms made their way to America for the first time. Crops went back and forth across the Atlantic, transforming American, Euro-American, African, and European agriculture. Corn became prominent in Africa, for instance. Potatoes seemed odd to Europeans at first because, as stem tubers, they grow underground. But the Incan potato found its way to Germany, Russia, and the British Isles, and the French monarchy encouraged their peasants to plant them to offset their reliance on wheat. Peanuts, pumpkins, squash, avocados, pineapples, strawberries, zucchini, and chili peppers were new to Europe, among dozens of other staples now taken for granted. Tomatoes, first cultivated by Aztecs, made their way most famously to Italy.

The Irish grew dependent on a single potato strain while under English occupation, and roughly a fifth of their population starved to death in the 1840s when blight infected the crop during the Potato Famine – the worst natural disaster in modern history. Another fifth migrated to America, seeding an Irish-American population ~ 6x larger than the Irish population. The English unnecessarily allowed one million Irish to perish in the 1840s without feeding them surplus crops in order to not disrupt commodities markets, even requiring that livestock, oats, and barley be exported from other parts of Ireland to England. They fed some that were willing to drop the Mc-prefix from their surname or convert from Catholic to Protestant Christianity. Finally, they sent some corn, but the Irish didn’t know how to grind it into flour or cook it. Most of the aid that arrived in Ireland came from the Ottoman Empire, Anglo-American Quakers, and American Choctaw Indians familiar with such hardship from the Trail of Tears. Irish-Americans never forgot England’s callousness. As they worked their way into the American Democratic Party, Irish immigrants stayed committed to the idea that governments are responsible for the welfare of the disadvantaged. This is just one of many examples of how biology overlaps with human history.

Tobacco and sugar are other examples. Slave-grown Tobacco made its way to western Europe for the first time and laid the foundation for the southern British colonies in what became the United States, as we’ll explore in more detail in Chapter 5. Mediterranean sugar arrived in the Caribbean, where planters transformed it into rum and combined it with South American cocoa to create chocolate, a new European obsession. Before making its way to the Mediterranean, natural cane migrated from the South Pacific (New Guinea) to the Middle East in the 13th century, then to Europe. It was grown in the Levant, Spain, Sicily, and Cyprus. Traders valued sugar, previously only found in fruit and honey, on par with precious gems. Dutch-style windmills with British cranks and shafts crushed the husks while enslaved West Africans laboriously boiled cane juice down to brown sugar that British dropped in their tea from China. Later, refineries in London and Glasgow, Scotland (aka “sugaropolis”) leached out the molasses and vitamins and minerals altogether, producing the long shelf life, powdery “white gold” we’ve come to know and love. Humans had long since evolved to seek out sugar in nature, but mass production made it too readily available. It was a relatively safe way to stimulate the brain’s pleasure zones, but overuse could lead to diabetes and rotten teeth. Black teeth like those of Queen Elizabeth were so trendy in England as a sign of wealth that some people colored their teeth. Europeans’ newfound love for chocolate and tobacco drove the trade in human trafficking, as millions of kidnapped Africans involuntarily crossed the Atlantic to work on plantations.

Coming of the White Man, Joshua Shaw, 1850, Elizabeth Waldo-Dentzel Collection, Northridge, California

These Beaver Hunting Grounds Would’ve Included Land Extending To The East Coast In the 16th & 17th Centuries, Courtesy of C.J. Lippert-WikiCommons

Europeans & Indigenous Americans

Indians and Whites traded tobacco as a kind of default currency, along with furs. White traders coveted pelts as fur coats, robes, and hats became popular in Europe while Indigenous Americans preferred European guns, iron (axes, nails, saws, kettles), wool, and alcohol. Some tribes over-hunted beaver and other pelt-bearing animals like deer, bears, ermines (white-coated weasels), or skunks. Colonial American muskets weren’t long for accuracy (they were often bent anyway), but rather because Whites swapped them for beaver pelts based on the gun’s length.

Pushing west in pursuit of more fur brought Indians into more conflict with each other, exacerbating traditional military rivalries and causing an accordion effect of migration. Eastern tribes moved west as they pursued animal pelts, pushing others even further west. As we’ll see in Chapter 23, the seemingly traditional Plains Indians Euro-Americans encountered who hunted buffalo with guns on horseback weren’t really that traditional. Guns and horses didn’t exist in pre-Columbian America and many of the tribes that inhabited the Plains supplanted previous tribes after having been pushed out of hunting grounds around the Great Lakes because of this accordion effect. Lakota Sioux, for instance, displaced Kiowas and Crows in the Black Hills in the 18th century. Kickapoos in the Great Lakes region moved to Kansas, then northeast Texas where they mixed with Cherokees that had migrated there from northern Arkansas after having been kicked out of the Great Smoky Mountains, then they both got kicked out of Texas, with some moving to Coahuila, Sonora, and Durango, Mexico and others to Oklahoma. Their ancestral grounds are in many places.

At least Native Americans were acquiring useful items from Europeans. Axes improved Indians’ capacity to fell trees, kettles were easy to cook in over open fires, and wool dried quicker than other cloths or skins. In England, Quaker Abraham Darby I learned to coke-smelt pig iron in a blast furnace, making it cheaper, thinner, and more durable than cast-iron heated with coal. That innovation made his cooking pots ideal for loading on boats and trading in America, Africa or Asia. Nineteenth-century Sioux tribes on the Great Plains acquired guns from Whites, along with smallpox inoculations. Europeans also traded alcohol to Native Americans, which proved detrimental.

The sort of Indian battles shown by Hollywood over the last century happened, to be sure — if anything more brutal than normally depicted. But on a day-to-day basis, Whites and Indians more commonly crossed paths in trade, missionary work, and romance. Europeans killed more Indians accidentally by transmitting disease than through warfare. Intermarriage was common, especially in Latin America where few Spaniards or Portuguese brought wives and families with them to the New World. Likewise, French fur traders often married Indians.

More bizarre, Indians abducted Europeans to replace those who had died in combat against Whites. Indians had complicated rules of engagement in war, the subtleties of which often escaped newcomers. Sometimes they fought to kill, other times merely to mark their enemies, more similar to a sport. If Whites killed Indians during the wrong type of engagement, the latter usually wanted someone to replace the person whom they felt was wrongfully murdered. Indians didn’t share the common Judeo-Christian dichotomy of murder in civilian life being bad and murder in war being good; there were gradations in between.

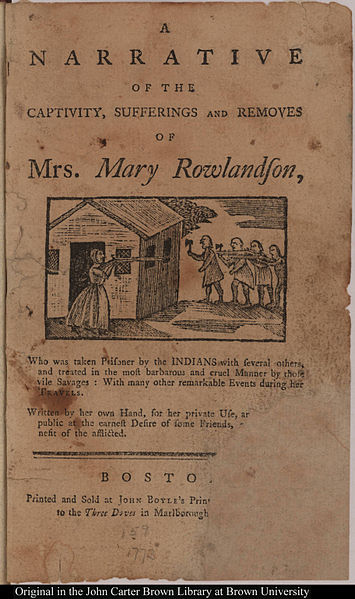

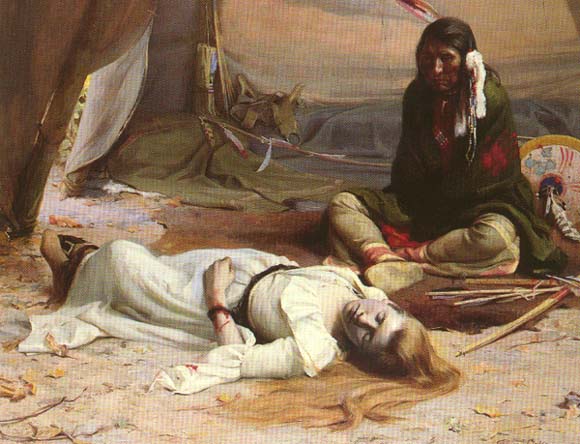

White Captivity Narratives told of these abductees’ varied experiences and were the first type of American literature to sell in Europe. Captives were mildly tortured and/or initiated before being ceremoniously transformed into full-fledged members of the tribe, sometimes even being made to live with the deceased member’s wife and expected to raise his children. But once hazed and inducted, Whites were treated as equals and could even work their way up into positions of leadership. Most grown Whites found the adjustment difficult and tried to run away or be traded back. Many children, though, preferred Indian life and never wanted to return.

One young girl, Eunice Williams, was taken from her western Massachusetts home in the 1704 Deerfield Raid and didn’t return until over a decade later to greet her parents. She had to sleep outside because she hadn’t been in a structure with a low-hanging roof the entire time and the house made her feel claustrophobic. She no longer spoke English and told her parents through a translator that it was too late; she no longer knew them or had any desire to return to their society. She’d also converted to Catholicism, which was problematic as her father was a Puritan (Protestant) minister. Similar stories played out among thousands of people. An ancestor of actor Christopher Meloni from Law & Order: SVU was raised Protestant in Puritan Groton, Massachusetts, captured by Native Americans during an early war between Britain and France, and spent twelve years in captivity before being ransomed to French Catholics in Quebec who were looking to boost their population. He reinvented himself as a French Catholic farmer after being born as a British Protestant.

A fictional variation plays out in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), as John Wayne relentlessly hunts down his niece, who was captured by Comanches. The movie is loosely based on the life of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was captured in 1836 and rescued against her will by Texas Rangers. The filmmakers researched 64 cases of Indian child abductions in 19th-century Texas.

Such stories were surprisingly typical in colonial America and would be difficult to match today in terms of dramatic culture clash. Humans would have to meet aliens on another planet to reproduce the lack of familiarity then between Europeans and American Indians. Since women farmed in Indian societies, Whites noted how lazy Indian men were and Indians noted how feminine white farmers were. Since gold wasn’t scarce in the Caribbean, Indians there would trade chests full in exchange for trinkets, falconry bells, or mirrors that they saw as miraculous. Imagine how amazing a mirror would be if you’d never seen yourself. Indians on the East Coast scarcely knew what to make of the “smelly hairy people” who arrived on their shores (Indians did not grow facial hair), while Europeans conceived of Indians alternately as either brutal, backward savages or — usually from a distance — idealized children of the wilderness, uncorrupted by the degenerating effects of civilization. British called the latter, positive stereotype the noble savage, the French le bon sauvage. Interaction between Indigenous Americans and Euro-Americans will play out over the remainder of our course and continues today.

Optional Reading & Viewing:

Texas A&M Center for the Study of the First Americans

Sam Haselby, “What Big History Misses,” Aeon, 2021

Nikhil Krishnan, “Justice for Neanderthals! What the Debate About Our Long-Dead Cousins Reveals About Us,” The Guardian, September 2023

Jennifer Raff Forbes Blog & Raff, “Rejecting the Solutrean Hypothesis,” The Guardian, February 2018

Jennifer Raff, “The First Americans: The Story of Wonderful, Uncertain Science,” Aeon > Bunk, December 2022

Stephen Oppenheimer, et al. “Solutrean Hypothesis: Genetics, the Mammoth in the Room,” World Archaeology, 12.14 (> JSTOR w. ACC ID)

Fen Montaigne, “The Fertile Shore,” Smithsonian, January 2020

Douglas Preston, “The 9,000-Year-Old-Man Speaks,” Smithsonian, September 2014

Gary Gugliotta, “The First Americans,” Smithsonian, February 2013

Hanae Armitage, “Polynesians, Native Americans Made Contact Before European Arrival, Genetic Study Finds,” Stanford Medicine, July 2020

Charles C. Mann, “1491,” Atlantic Monthly, March 2002

Shan Wang, “What Do You Know About America, 1491?,” Atlantic, October 2023

Glenn Hodges, “Tracking the First Americans,” National Geographic, January 2015

Elizabeth Culotta & Ann Gibbons, “Almost All People Living Outside Africa Trace Back To A Single Migration More Than 50,000 Years Ago,” Science, September 2016

Adam Rutherford, “A New History of the First Peoples in the Americas,” Atlantic, October 2017

Carl Zimmer, “Oldest Fossils of Homo Sapiens Found in Morocco, Altering History of Our Species,” New York Times (6.6.17)

Roberto Ferdman, “How Corn Worked Its Way Into Just About Everything,” Washington Post (7.14.15)

Valerie Hansen, “Vikings in America.” Aeon (September 2020)

Margot Kuithems, et al. “Evidence for European Presence in America in AD 1021,” Nature News, 10.21

William O’Connor, “How the Vikings Saved Europe and Got a Terrible Reputation,” Daily Beast (7.12.17)

Guenter Lewy, “Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?” HNN, September 2004

Alexander Medlicott, Jr., “Return to This Land of Light: A Plea to an Unredeemed Captive” (JSTOR, New England Quarterly 38 2, 1965)

Ross Anderson, “The Search For America’s Atlantis,” Atlantic (9.7.21)

Katherine Kornei, “Vikings Were in the Americas Exactly 1000 Years Ago,” New York Times (10.20.21)

Megan Gannon, “The Knotty Question of When Humans Made the Americas Home,” Essay/Unearthed (9.4.19)

Alexander Ewen, “The Death of the Bering Strait Theory,” Indian Country Today (9.18)

Ed Yong, “The Link Between Neanderthal DNA and Depression Risk,” Atlantic: Science (2.11.16)

Optional Reading On Clovis Sites:

After the discovery of several more Clovis Points, archaeologists theorized about the frozen land bridge between Russia and Alaska and looked for new sites. A trove of arrowheads with trademark Clovis fluting (grooves) was discovered outside Bozeman, Montana in 1968, dating to 13 kya. The remains of an infant boy, later named Anzick-1, were near the Bozeman Clovis Points. Subsequent research revealed a mixture of 33% Siberian-66% East Asian DNA that can no longer be found in Asia, only America, and that Anzick dated to 12.5 kya. The remains of a female skeleton named Naia found in an underwater cave off the Yucatan Peninsula date back 12-13k years. In 2011, researchers from Texas A&M’s Center for the Study of First Americans re-examined a mastodon rib found near Sequim, Washington in 1977, confirming an earlier study that the animal was nearly 13.8k years old, with a projectile point embedded in it that DNA and protein analysis showed came from another animal. A controversial archaeological site called Monte Verde in northern Patagonia (Chile) dates to 13.5-14.8 kya (some say older), challenging the “Clovis First” 12-13k theory that some scholars still irrationally adhere to. Animal matter and DNA extracted from fossilized human excrement in the Paisley Caves of eastern Oregon date back 14.3k years. Another mammoth tusk found next to a knife along Florida’s Aucilla River (the Page-Ladson Sink) in the 1980s was 14.5 kya. A site in Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, discovered in 2019, dates back 15k years. Artifacts from the Buttermilk Creek Complex north of Austin, Texas date back 15.5k years, at least according to a technique called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) that measures how long it’s been since sunlight hit the soil around artifacts. Charcoal also dates well, making fire pits useful. The Meadowcraft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania could go back 16-19 kya. Research into ancient America is ongoing and you don’t need to get bogged down in the details and all estimated dates, but you get the basic idea. Also remember that the oldest known sites don’t mean that there aren’t yet older, still undiscovered, sites.