A Guide to Thinking Critically About History

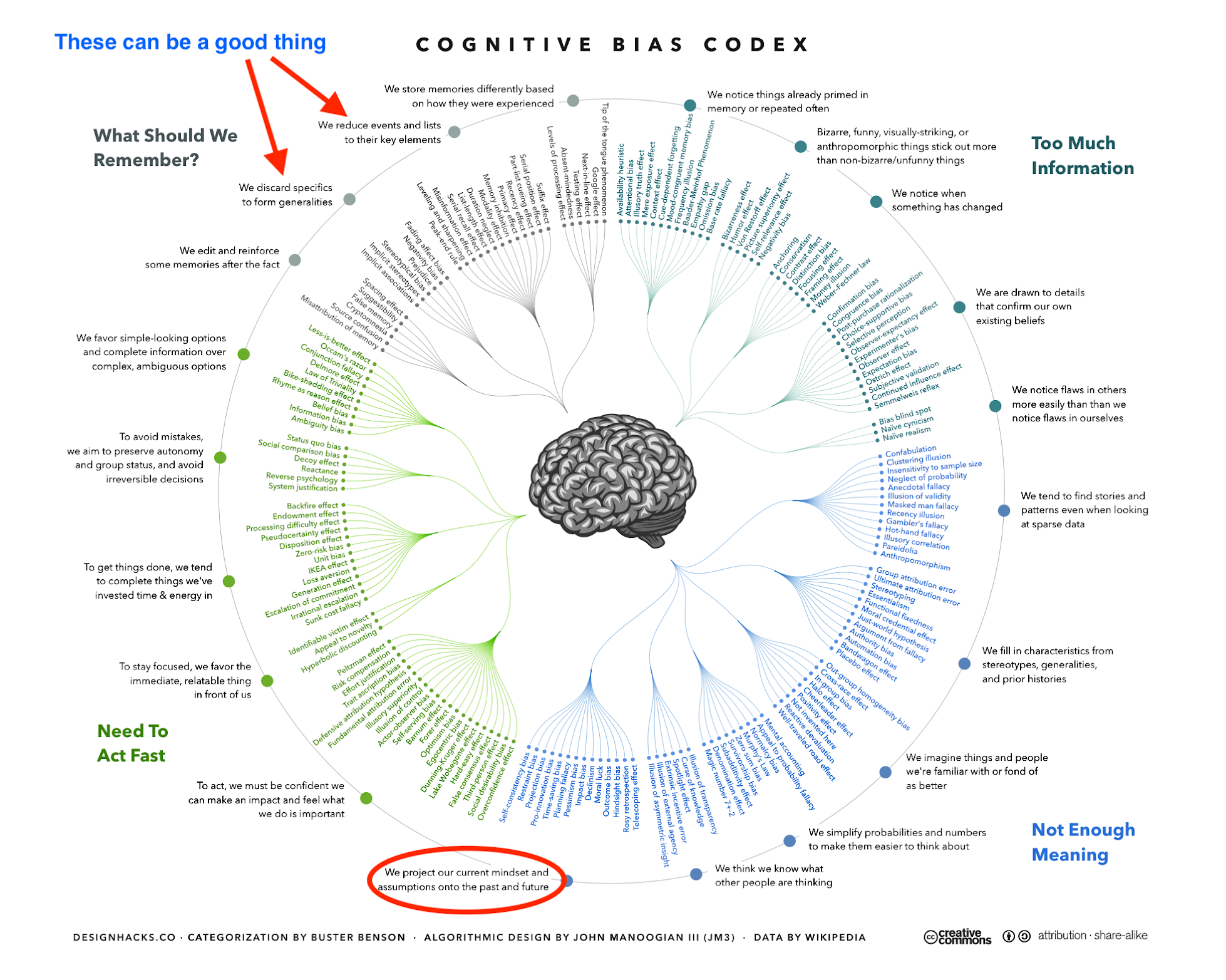

From time to time, we’ll be referring in class or online to argumentative fallacies as we interpret history and the way it’s interpreted by others. I’ll sometimes use the numerical codes below in the comment box for your written work (e.g. RD-1 will refer to Item #1 on the Rear Defogger page). All of us, students and professional historians alike, can easily fall into habits of crooked thinking. In fact, the more people care about a subject, the more likely they are to make questionable leaps of logic or play argumentative games, even if subconsciously. Fallacies, rhetorical fortresses, and cognitive biases transcend political partisanship and aren’t things that dumb people are guilty of as opposed to smart people. They are tire ruts that all of us fall into because our brains resist sound thinking about matters other than those directly related to our own survival. It takes too much energy and burns calories we could otherwise use for useful things like hunting for food and building shelters. Yet, think we must because many of these matters are related to our survival. Intellectual laziness and fallacies are to be avoided as best we can when studying history, just as cognitive distortions are discouraged in behavioral psychology. Understanding these tire ruts enables System 2 Thinking (aka, thinking slow instead of [too] fast). The links and list below can help us defrost the rear windshield, so to speak, as we look behind us (thus the title of our page).

For others — politicians, salesmen, lawyers, professors, journalists, magicians, or anyone putting a spin on things — knowledge of fallacies, framing, and crooked thinking constitute a virtual playbook of how to manipulate their audience without actually lying. For that reason alone, understanding common biases and argumentative fallacies should be a basic part of citizens’ educations as they embark on a world of voting, buying, litigating, learning, posting, and debating. Historical interpretation is an excellent vehicle to acquaint ourselves with these nuts and bolts of argumentation. One can make infinitely bad arguments on behalf of truth, but there are limits to the quality of cases one can make on behalf of a false proposition. At the conclusion of this course, you should be familiar with the habits of mind that it takes to understand history and arguments about history. Today’s media landscape affords the best opportunities ever for gathering good and diverse information, but it’s also flooded with “noise,” misinformation, disinformation, and bad arguments. Scientist E.O. Wilson wrote (optimistically) that “We are drowning in information while starving for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely.” I’d offer a bleaker suggestion that the world will continue to be run by people willing and able to manipulate those unable to understand argumentation, as it’s always been, and that historical interpretations are often an ingredient in that manipulation.

Tedious? Perhaps. But, without a long history of philosophers and psychologists unpacking how to argue and think, you’d probably be running around right now trying to kill game with a stick instead of looking at your screen in air conditioning.

Topic Drop Ins (w. numerical codes)

Most of the content below involves history and politics/media, but it occasionally dabbles in UFOs, fringe theories, weather, and nutrition to demonstrate a point. If it seems purely like a list of negative things to avoid, remember that, in each case, the inverse is a positive step toward clearing the rear window and, by extension, the front windshield.

1. Be Wary of Subtext(s)

2. Missing the Big Picture & Broader Historical Context

3. Over-interpretation of Roots or Results

4. False Analogy, False Equivalence or Lack of Perspective

5. False Premise (and debatable premise)

6. Confusing Association/Correlation & Causation, or Cause-and-Effect (post hoc fallacy)

7. Over-Generalizations

8. Conflation (Lumping Together), Not Distinguishing Nuance, Mixing Apples-Oranges (and association fallacy)

9. False Dichotomy (false choice)

10. Irrelevance

11. Long Leaps of Logic

12. Anchor Bias

13. Bandwagon Effect

14. Argument From Ignorance & Argument From Authority

15. Confused Terminology

16. Focusing Effect & Reductionism (tunnel vision)

17. Framing Effect

18. Non-Comparative Comparisons

19. Excessive Slippery Slopes

20. Straw Man (or Bogeyman)

21. Selective Observation (including “my side” bias)

22. Shifting Baselines

23. Circular Reasoning

24. No Back-Up or Argument Support

25. Confusing Quantity & Quality of Evidence

26. Teleological Thinking & Determinism

27. Shoehorning or Retrofitting (related to Prophecy)

28. Historians’ Fallacy

29. Fundamental Attribution Error & Actor-Observer Bias

30. Anachronism

31. Chronological Error / Sequencing

32. Counterfactual History

33. Too Many Contingencies

34. Progressophobia

35. Ad Hominem Attacks & Rhetorical Fortresses

36. Fallacy Fallacy

Other Sites

Is History Written By The Winners? History Today

1. Be Wary of Subtext(s)

There’s usually a story behind the story that is the reason we’re talking about it. The reason is that virtually no one actually cares about history, only how to employ history to make a point about the present and future.

Ex. 1: The most common use of subtext connects to a story’s broader context. In 1980, Ronald Reagan gave a speech at the Neshoba County Fair outside Philadelphia, Mississippi reminding voters during a discussion on education that he’d always admired Southerners’ appreciation for states’ rights. As is often the case in American politics, the subtext behind the code word states’ rights was race. This wasn’t about education (the text); Reagan was telling the audience that he was on their side regarding the Civil Rights legislation of the 1960s (against it). When Confederate flags flew in the audience, it wasn’t out of pride for the local schoolhouse. There was already subtext behind the location of the speech. This was subtextpalooza. Philadelphia, Mississippi was where three civil rights workers were killed by the sheriff and Ku Klux Klan in 1964. While Reagan didn’t endorse that violence (he wasn’t that vulgar), the town was a symbolic place to recruit southern, white voters. Reagan’s Neshoba Co. speech manipulated his audiences’ perceived sense of history on behalf of the GOP’s Southern Strategy.

Ex. 2: This one also has to do with race. In the 1995 O.J. Simpson trial, the text was the actual murder case but subtexts were race and celebrity. Simpson was a famous African-American football player accused of killing his white wife and another man. The broader context was decades of racial tension between the LAPD and the city’s African-American community, including a recent miscarriage of justice in the trial of Rodney King, in which an all-white suburban jury exonerated officers that illegally beat King up on film.

Ex. 3: In HH 1302 Chapter 4, Margaret Sanger’s reputation and association with eugenics are in the spotlight because of her founding role in Planned Parenthood. The text is Margaret Sanger, but the subtext is whether American taxpayers should fund Planned Parenthood given that they advise and/or perform abortions. No one cares about Margaret Sanger; all of us, pro-life and pro-choice, care about abortion rights going forward.

Ex. 4: Normally, the Secretary of State isn’t held accountable for everyday security matters at embassies around the world. The subtext of controversy surrounding the 2012 Benghazi tragedy was SOS Hillary Clinton’s upcoming run at the 2016 presidency. Republicans wouldn’t have investigated Benghazi ten times if they hadn’t anticipated running against the woman who was Secretary of State at the time (Wiki).

Ex. 5: Cryptocurrency and one’s attitude toward it carry with it a subtext about one’s attitude toward governments and nationalism. Those skeptical of today’s nation-states, or at least their capacity to manage currencies effectively, are more likely to favor cryptocurrencies.

Ex. 6: In Chapter 18 on the Vietnam War, President Diem doesn’t win over many South Vietnamese with his support of Catholicism at the expense of Buddhism. The subtext was the perception among critics that Diem was a western lackey, underscored by his endorsement of the “white man’s religion.” France brought Catholicism when they colonized Vietnam in the 19th century. Catholicism symbolized suspicions that Diem was America’s puppet, just as Bao Dai had been France’s puppet.

Ex. 7: Subtext can also refer to the message one sends beyond the actual text of the message. A student emails his/her professor and asks, “based on my current scores, can I still make a B?” This might be a situation where the student can’t do the math (which is fine and we can work with) or doesn’t understand the grading scale (which can be clarified), but it’s most likely an email with the following subtext: I could probably figure this out on my own but I’m too lazy so I’m just going to have you do it for me because my time is more valuable than yours. Word to the wise: this is not a subtext you want to convey to future bosses on the job.

2. Missing the Big Picture & Broader Historical Context

This is can be connected to Subtexts (as in the LAPD example above), Selective Observation (#21 below), “not seeing the forest for the trees,” and Shifting Baselines (#22 below).

Ex. 1: After the atomic attacks on Japan in 1945, many military leaders in the U.S. voiced their disapproval of nuclear weapons. They may have been genuinely opposed, but it’s worth noting that most of those opposed came from branches of the armed forces that stood to lose funds relative to the Air Force as it branched out of the Army and formed its own wing that included nuclear weapons. That’s one context of the argument, with others being moral, strategic, etc. Later, when the Army and Navy got funding for some of their own nuclear weapons, criticism died down quickly. Always be aware of the motivations and biases of various actors in the historical play, but also understand that motivation alone doesn’t prove guilt. Cui bono (who profits?) is a very worthwhile question to ask, but it’s not enough. That’s why a common plot device in crime mysteries is to have multiple promising suspects.

Ex. 2: When you consider whether aliens from another planet invaded Los Angeles in February 1942, consider the context. Civilians and military on the West Coast were understandably on edge in the months just after Pearl Harbor. The night before the alleged attack, Japanese subs fired on an oil rig just north of Los Angeles, near Santa Barbara. Might these factors have contributed to why the military would overreact to a weather balloon? Weigh that versus the unlikelihood that beings from another planet would visit, coincidentally, right as all this was happening. The same goes in general with the timing of the UFO phenomenon and the early Cold War and humanity’s own explorations into space (more below).

Ex. 3: Archaeologists unearthed human remains beneath Benjamin Franklin’s London home and dated the bones to his stay there (1750s-70’s). Imaginative theories popped up connecting rituals to his membership in the Masons and alleged association with the Illuminati, and even devil worship. Context presents a more likely if boring explanation. Franklin was interested in science and anatomy and, at the time, the only real way to study corpses was to purchase them on a grave-robbing black market. We don’t know for sure how the bodies ended up under his basement, but anatomical research is a far more likely explanation than Satanic worship.

Ex. 4: During the Protestant Reformation, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Pope Leo X might have cracked down harder on Martin Luther’s heresy. However, in the larger context, they were hesitant to alienate local princes like Frederick of Saxony that supported Luther because they needed their support in fending off a potential Muslim invasion. These princes understood this context and leveraged the situation to gain power at the expense of the Catholic Church.

Ex. 5: When Henry VIII appealed to Pope Clement VII for an annulment to his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the Pope didn’t refuse him just because Henry was a high-profile king or that the Church believed marriage was for life. The broader context was that Clement didn’t want to alienate the powerful Holy Roman Emperor, the Spanish King Charles V, who was Catherine’s nephew. This led to the English Reformation, which led to English colonization of America, which led to the United States.

Ex. 6: Franklin Roosevelt has been criticized as racist for not wanting African American Marian Anderson to sing at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939. It’s true that he didn’t want her to, but one of his reasons, along with fear of alienating southern Democrats, was that he feared violence on the part of the KKK. Maybe these reasons still aren’t good enough but, either way, his concerns weren’t as they might’ve appeared on the surface (with politicians, they never are). The context underlying this episode is FDR’s attempt to unite the liberal and southern wings of the Democratic Party to pass New Deal legislation.

Ex. 7: In our textbook (1302: 14) I mention that John Kennedy appears clueless on one recording about the presence of American missiles in Turkey. A reader might interpret that as meaning that my overall interpretation of Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis was cluelessness and incompetence, which is not the case — that’s just one incident within a bigger story. Look for bigger, more general interpretations rather than focusing on one sliver of an argument.

Ex. 8: The Russia Hoax Hoax: the idea that since the Steele Dossier was bogus, there were procedural mistakes in initiating the Carter Page investigation, and Hillary’s Clinton’s lawyer shouldn’t have investigated wrongdoings at Alfa-Bank, therefore the whole idea that Donald Trump was working with Russia during the 2016 election was wrong and he was unfairly persecuted. But most journalists never saw these other matters as important trees in the collusion forest and neither did the Mueller Report, which documents two-hundred pages of suspicious collusion between Trump’s campaign and Russia and several examples of potential obstruction of justice in the second two-hundred pages. Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign manager during the summer of 2016, seemed incline to auction off eastern Ukraine in exchange for Russia’s aid in the election, and later testified to as much. In Michael Wolff’s Fire & Fury, Trump’s chief strategist Steve Bannon said Trump, Jr., Jared Kushner, and Manafort’s meeting with Russians at Trump Tower to get dirt on Hillary Clinton was treasonous and unpatriotic. The Russia Hoax Hoax is Exhibit 1A in “missing the forest for the trees.” The most important trees were ones that were in the open, including Trump’s business interests in Russia, the sudden reversal to a pro-Russian foreign policy during the 2016 GOP convention, the glaring fact that the man who led that convention, Manafort, worked for the wrong (pro-Russian) Ukrainian Viktor Yanukovych, Trump’s incessant obstruction of the investigation into Russia’s interference in the election, Trump’s “joke” that Russia should find Hillary Clinton’s missing emails followed hours later by them attempting to do so, and the fact that, at Helsinki, Trump openly sided with Russia against his own country’s intelligence agencies as they tried to investigate Russian involvement in the election, causing Vlad Putin to nearly burst out laughing, though Trump later argued un-persuasively that was a slip of the tongue. Most important is the bigger context that Putin had every reason to help as Trump would hopefully rattle American democracy’s cage. Motive doesn’t prove guilt, but Putin has a long pattern of interfering in other countries and suspected that Hillary had done that in Russia as Secretary of State. Trump didn’t challenge Putin about his interference in the 2016 election, which Republicans, the CIA, and FBI all agreed happened regardless of Trump’s connection to Russia. In their 2010 election, six years before Trump supporters did likewise with Hillary Clinton, Yanukovych supporters chanted “Lock Her Up” toward their rival, pro-western Yulia Tymoshenko (right), co-leader of the Orange Revolution, whom they imprisoned until 2017 on spurious charges after defeating her. Sadly, the editorial staff of Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal was all in on this Russia Hoax fallacy. But the Russia Hoax Hoax isn’t just right-wing spin; it’s also the product of the left searching for and not finding hidden secrets and “smoking guns” instead of just connecting dots that they did know about.

Ex. 8: The Russia Hoax Hoax: the idea that since the Steele Dossier was bogus, there were procedural mistakes in initiating the Carter Page investigation, and Hillary’s Clinton’s lawyer shouldn’t have investigated wrongdoings at Alfa-Bank, therefore the whole idea that Donald Trump was working with Russia during the 2016 election was wrong and he was unfairly persecuted. But most journalists never saw these other matters as important trees in the collusion forest and neither did the Mueller Report, which documents two-hundred pages of suspicious collusion between Trump’s campaign and Russia and several examples of potential obstruction of justice in the second two-hundred pages. Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign manager during the summer of 2016, seemed incline to auction off eastern Ukraine in exchange for Russia’s aid in the election, and later testified to as much. In Michael Wolff’s Fire & Fury, Trump’s chief strategist Steve Bannon said Trump, Jr., Jared Kushner, and Manafort’s meeting with Russians at Trump Tower to get dirt on Hillary Clinton was treasonous and unpatriotic. The Russia Hoax Hoax is Exhibit 1A in “missing the forest for the trees.” The most important trees were ones that were in the open, including Trump’s business interests in Russia, the sudden reversal to a pro-Russian foreign policy during the 2016 GOP convention, the glaring fact that the man who led that convention, Manafort, worked for the wrong (pro-Russian) Ukrainian Viktor Yanukovych, Trump’s incessant obstruction of the investigation into Russia’s interference in the election, Trump’s “joke” that Russia should find Hillary Clinton’s missing emails followed hours later by them attempting to do so, and the fact that, at Helsinki, Trump openly sided with Russia against his own country’s intelligence agencies as they tried to investigate Russian involvement in the election, causing Vlad Putin to nearly burst out laughing, though Trump later argued un-persuasively that was a slip of the tongue. Most important is the bigger context that Putin had every reason to help as Trump would hopefully rattle American democracy’s cage. Motive doesn’t prove guilt, but Putin has a long pattern of interfering in other countries and suspected that Hillary had done that in Russia as Secretary of State. Trump didn’t challenge Putin about his interference in the 2016 election, which Republicans, the CIA, and FBI all agreed happened regardless of Trump’s connection to Russia. In their 2010 election, six years before Trump supporters did likewise with Hillary Clinton, Yanukovych supporters chanted “Lock Her Up” toward their rival, pro-western Yulia Tymoshenko (right), co-leader of the Orange Revolution, whom they imprisoned until 2017 on spurious charges after defeating her. Sadly, the editorial staff of Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal was all in on this Russia Hoax fallacy. But the Russia Hoax Hoax isn’t just right-wing spin; it’s also the product of the left searching for and not finding hidden secrets and “smoking guns” instead of just connecting dots that they did know about.

Ex. 9: The claim that Donald Trump lost the 2020 election due to voter fraud hinges on the believer missing the forest for the trees. The key to believing such claims is to find an isolated case of fraud and assume that can be extrapolated onto a larger scale, when really it was just isolated. When the Associated Press studied such claims over six contested states that Trump lost in 2020, they found only 475 cases (AP). The key to believing in the conspiracy is not knowing that 475 is a small number out of tens of millions of voters and not remotely enough to swing the election, combined with the assumption that those 475 cheated on behalf of Biden rather than Trump combined with not realizing that most elections have scattered instances of fraud.

Ex. 10: We almost take it for granted today that supporters of church-state separation are anti-religious. But a longer view makes one realize that everyone’s beliefs would’ve been outlawed at some point by some government. Thomas Jefferson and James Madison’s idea that complete, uncompromising religious freedom and lack of government interference would actually benefit rather than hinder religion was arguably borne out over the course of American history. No religion maintains any legal preference over any other in the United States and the U.S. is one of the most religious countries in the world. Historically, being religious often made people more likely to favor religious freedom, not oppose it.

Ex. 11: This Civil War blog is an example of missing the big picture and selective observation. The author uses primary sources and is genuinely engaged in trying to understand the Civil War in the context of the times, but he’s over-focusing on one of those contexts, taxation/tariffs, at the expense of many others, including western expansion, the potential conflict between wage labor and slavery, Lincoln’s personal evolution between 1858 and ’65, thousands of soldier’s letters and, most jaw-dropping, the entire history of the 1850s, when the biggest controversies in the country concerned slavery, not tariffs. No Confederate soldiers marched off to war in 1861 saying that they were fighting against tariffs, though many mentioned things other than slavery. The author doesn’t unpack the southern declarations of independence, except to mention them briefly to support of the idea that war wasn’t about slavery because “of the 11 seceding states, only 6 cited slavery as [their] primary cause for leaving the union.” This blog isn’t a reactionary defense of southern heritage and is worth reading for the “trees” about taxes/tariffs, but the author misses a vast forest in arguing that these trees mean the Civil War wasn’t about slavery. South Carolina secessionists and Confederate politicians told us otherwise directly.

Ex. 12: The idea that tearing down Confederate statues is an example of rewriting history is subconsciously premised on the idea that erecting them in the first place was an attempt to accurately portray history or to honor an accurate interpretation of why the Confederacy fought. If putting the statues up in the first place was attempt to mislead the public as to the war’s aims or, more bluntly, just to intimidate African Americans, then it’s harder to sympathize with bemoaning their demise.

Ex. 13: This a modern-day example of missing the big picture.

Someone once told me that he opposed wind power because birds sometimes get killed in the turbines. While we all love birds, and the problems they have in turbines might be one of many factors we think about when considering energy, it’s best to step back and look at our overall energy use. What are the overall percentages of production broken down by coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear, hydro, wind, solar, etc.? What are the cost/benefit analyses of each type of energy? How important is climate change and how much will it cost? Can we do a better job of protecting birds as we build and run turbines? It might be best to consider all these things before deciding that you oppose all wind power because some birds get killed. The same goes with all the pros and cons of all types of energy and, for that matter, with the pros and cons of any topic.

Always think of the historical context surrounding whatever issue or event it is that you’re studying. Often that sheds new light and will lead you to interpret things in a different way. It’s impossible, for instance, to understand the American Revolution without understanding the broader context of the British Empire and European diplomacy. It’s impossible to understand Nazism without understanding its connection to World War I and historical antisemitism. It’s impossible to understand American race relations without understanding slavery and the Mexican war. Context is why it’s impossible to understand anything well without understanding its history, which is why you’re taking this class.

3. Over-interpretation of Roots or Results

Be wary of judging something based on its long-term historical roots or of judging something historical based on what someone does with it later.

Ex. 1: Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, was a racist and/or dabbled in eugenics. Therefore, people like Hillary Clinton who support Planned Parenthood today are trying to commit genocide against inner-city Blacks. Modern liberals, whatever their other faults, aren’t into genocide, and neither was Sanger.

Ex. 2: Adolf Hitler encouraged the invention of the Volkswagen Beetle, so today’s VW’s should be associated with Nazism.

Ex. 3: Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection is wrong because, after his death, people misapplied social Darwinism to racist eugenics or to justify unbridled capitalism (William Jennings Bryan’s critique in the 1926 Scopes trial).

4. False Analogy, False Equivalence or Lack of Perspective

Avoid unwarranted equivocation and what psychologists call “magnification.” And don’t over-rely on whataboutism, the fine art of not addressing an argument by steering immediately to another argument, as in “well, what about….?”

Ex. 1: Should American Christians be intolerant toward Muslims? Well, look at Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father. One of his first acts as President was to send the Navy into battle against North African Muslims. True, but he didn’t do that because they were Muslims, rather because they were pirates. Conveniently flushed down the Memory Hole: Jefferson advocated religious tolerance toward all American citizens, including Muslims.

Ex. 2: The red lights should go on whenever anyone describes the U.S. government as “tyrannical,” even if it is overbearing in a particular instance. Describing any of the democratic countries’ governments as generally tyrannical waters down the term and is likely coming from the mouth or pen of someone unfamiliar with real tyranny or with a warped sense of reality. They’re “magnifying” and over-generalizing from instances where democratic governments really are overbearing. If the majority in a democracy passes a law, such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act, you might not like it, but the law wasn’t passed by a dictatorship against the wishes of the people. There’s a difference. The same goes with the 2001 Patriot Act, which a critical balance of voters supported. Democratic countries like the U.S. experience the advantages and disadvantages of not being tyrannical.

Ex. 3: Americans were just as bad as Germans during WWII because they held Japanese citizens in concentration camps. This is a false equivalent brought on by confusing terminology and a lack of perspective and knowledge of what happened. While it’s true that the U.S. imprisoned innocent Japanese-American citizens and that one could technically call internment camps “concentration camps” because they were set up to concentrate (and cordon off) a particular population, the U.S. crucially didn’t enslave, torture, and murder Japanese-Americans in these camps.

Ex. 4: American eugenicists influenced German Nazis prior to the Holocaust. However, for the most part, they had no agenda to exterminate anyone, only to sterilize “undesirables” before they had children. Thus, we can’t equate the American eugenics movement with the Holocaust. Like the Japanese internment camps, that’s a false equivalent. You can understand that while simultaneously criticizing eugenics and internment camps.

Ex. 5: Dr. Ben Carson argued that since the Affordable Healthcare Act (aka Obamacare) requires people to purchase health insurance, it’s “worse than slavery.” It’s helpful in today’s media to say provocative things to draw attention to yourself, but the comparison shows a lack of perspective on both issues. Ultimately, this one is a matter of opinion (his assertion isn’t demonstrably false), but most reasonable people would argue that he’s either “magnifying” the downside of the insurance mandate and/or isn’t fully aware of the enslaved experience despite being African-American himself.

Ex. 6: Another example of a false equivalent would be to say, if we mention that the Sun is the center of the Solar System then, to be fair, we should give equal time to the idea that the Earth is actually the center of the Solar System. This one’s not a matter of opinion. The geocentric model doesn’t deserve equal time because it’s wrong. It deserves no time.

Ex. 7: The January 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol has led to a lot of shaky whataboutism on the part of its apologists. For instance: what about BLM protestors throwing rocks at federal building? It’s a false equivocation because BLM protestors aren’t president of the United States and throwing rocks is an example of vandalism rather than an attempt to overturn an election. It might be a bad thing, but it’s nowhere near being as serious of an issue.

Ex. 8: People often liken giving COVID-19 a Chinese nickname to the erroneous “Spanish Flu” moniker from 1918-19. But that’s a false equivalent as the 1918-19 influenza pandemics really weren’t from Spain, whereas COVID-19 originated in China. The problem with “Spanish Flu,” in other words, isn’t that it’s politically incorrect, but rather factually incorrect. It might be completely unnecessary, or inspired by a cheap appeal to racism, to name COVID-19 after China, but it did originate there. In Spain’s case, since they weren’t involved in WWI their government didn’t censor mention of influenza in their press. Since people first read about it in Spanish newspapers, they mistakenly thought that it originated there. Many countries also nicknamed their version of the flu after their rivals, leading to widespread confusion.

Ex. 9: The state history standards Florida released in 2023 instructed students to learn about violence perpetuated against and by African Americans in riots such as Tulsa, OK and Ocoee, FL in the 1920s. While it’s true that African Americans might’ve fought back, it’s absurd to equate that with white mobs attacking them unprovoked in the first place and burning down their neighborhoods to prevent them form running businesses or voting, etc. That would be like blaming Americans for Pearl Harbor because they fired off some anti-aircraft artillery.

Note: Lack of perspective isn’t really a “fallacy,” but gaining perspective is one of the big advantages of studying history.

Ex. 9: Declinism. It’s helpful when you’re experiencing the near-universal human emotion that the world is going downhill to step back and understand that every era thinks of itself that way. There is virtually no such thing as a civilization that examines itself and pronounces that things are looking up and that people seem to be behaving better. The reason you’re especially aware of the immorality of your own era is mainly that you’re especially aware of your own era to begin with and that your layers of naivete are peeling off like onion skin as you age. Harry Truman was closer to the truth when he said that “there’s nothing new in the world except the history that you don’t know.” We discuss declinism’s close cousin progressophobia in entry #34 below.

Ex. 10: It adds perspective on UFO history to realize that, at every point in history, humans have seen things in the sky that make sense to their own given time period. In the Middle Ages, they saw angels. In the late 19th century, people didn’t see silvery disks but rather “mystery airship” dirigibles powered by pedaling Martians. That’s likely because they were aware of hot-air balloons and bicycles and were on the verge of inventing powered aircraft. In the 1950s, they saw craft similar to what we were trying to build ourselves to get into space and similar to what science-fiction writers imagined. Why no sleek, modern-looking craft in the Middle Ages? Why no pedal-powered dirigibles in the 21st century? Note: your author has gotten more open-minded about this in the 21st century. But, still, the Navy and Customs-Border Patrol saw and tracked high-end drones at the exact point in human history when we’re developing drones.

More examples of Whataboutism:

Ex. 11: Being a pro-choice Democrat because pro-life Republicans don’t do enough to help people after they’re born.

Ex. 12: Liking Donald Trump because other presidents have done bad things, too.

5. False Premise &/or Debatable Premise

Always consider the assumptions that an argument is based on. Example #2-10 above argues that the idea religious people should favor breaking down the separation of church and state is based on a premise, that involving the government strengthens peoples’ religious faith. That premise isn’t necessarily false, but it is most certainly debatable.

Ex. 1: We’re mystified that children from wealthier families are suffering from a disproportionate amount of asthma. Why is that? Maybe being reared in a clean environment lowers one’s immunity. That argument is premised (rightly or wrongly) on the idea that the poor raise their children in dirty environments. If that’s wrong, the argument falls apart.

Ex. 2: Examine the following phrase: “My mother is someone who, in all respects, should be a Republican. She works hard, is very religious and has strong family values. Yet, because she is a Hindu and Indian-American she votes Democrat.” It’s based on two debatable premises, or assumptions: that Democrats don’t believe in hard work, family or religion, and Republicans are racist. Those sound more like ideas that the respective parties think about each other than how people define themselves.

Ex. 2: The item above about Jefferson and Muslim pirates is premised on the idea that modern Americans should think or act in the same way as the Founding Fathers. That’s not a “false” premise, but it’s a debatable premise one would want to consider when making or hearing out the argument. It’s an appeal or argument from authority. Jefferson had slaves, too. Should we?

Ex. 3: The debate over whether Harry Truman should have dropped atomic bombs on Japan is premised on the reasonable assumption that he ordered the attacks. However, there’s no actual proof of such an order. This lack of proof, in turn, doesn’t prove that he didn’t. That fallacy is known as an appeal or argument from ignorance.

Ex. 4: FOX Commentator Greg Gutfeld explained on C-SPAN that the purpose of conservatives is to make liberals possible. To wit: conservatives take the initiative to create a business (taking risk, going into debt, working long hours, sleeping on the floor, etc.) so that a liberal can come along later and demand higher wages as an employee or benefit from re-distributed taxes. Whatever the argument’s other merits, the premise that job-creators are conservatives is an over-generalization. A 2012 poll of small-business owners, for instance, showed that about 45% identify as Republicans or Tea Partiers and 30% as Democrats with the rest independents. Among larger corporations, much of the cutting-edge entrepreneurship of the last 30-40 years has come from the “bluest” areas like Silicon Valley and the Pacific Northwest. “Blue Islands” (liberal strongholds) are more prosperous, in general, than “red” areas. Why would that be if they’re filled with unassertive pikers waiting around for job-creators? Moreover, conservative ranchers and farmers in “red states” receive billions each year in government subsidies — far more proportionally than “blue states.”

Ex. 5: Arguments over affirmative action at elite schools are normally premised on the idea that all students are better off at elite schools. Likewise, arguments against affirmative action are often premised on the idea that Whites are disadvantaged by such policies. However, sometimes Whites take spots from Asian-Americans to fulfill informal quotas.

Ex. 6: We often mistakenly assume that history moves uniformly, rather than in stops, starts, and regressions. Haven’t things gotten steadily and gradually better for women and minorities over the course of American history? In the big picture, yes, but not necessarily in any given small picture. Southern Blacks in some areas were arguably better off in the first few years after the Civil War (Radical Reconstruction) than they were in either the South or North a generation later. Women were less likely to work in most careers in the 1950s than earlier in the 20th century. Gains are hard won and often groups have to continue to fight to hang on to what they’ve won. Don’t assume that history progresses uniformly.

Ex. 7: We often bemoan the fact that we’ve lost the true meaning of Christmas or that it’s become too commercialized or less religious. That’s based on an unspoken assumption or premise that Christmas was traditionally a more religious holiday “back in the good ole’ days.” Here’s a good example of where history sheds a different light because Christmas has gotten more religious over time. Traditional Christmas was a more pagan and unruly celebration. Pagan Christmas celebrations kept the tradition alive for enough centuries that it was later able to take root as the relatively wholesome, religious (if commercialized) holiday. Of course, this whole discussion is premised on the idea that it’s a good thing for Christmas to be more wholesome, not less.

Ex. 8: Donald Trump’s idea that the U.S. was going to pull out of trade deals and diplomatic alliances and, instead, operate in its own best interests, was premised on the idea that the U.S. entered into such deals for the benefit of others rather than itself. But the reason America entered into trade deals and alliances wasn’t charity but rather because it reasoned, rightfully or wrongfully, that it was in its own best interests to create an international framework that played by its rules of democratic capitalism.

Ex. 9: The atomic attacks on Japan were justified because they killed fewer people than a landed invasion would have. That may be true, but it leaves out the possibility of other options. It’s premised on the notion that there were no other options. It’s incumbent on the person making that argument to rule out other options rather than just comparing the first two.

Ex. 10: Since my ancestor who fought in the Civil War didn’t own slaves, the war couldn’t have been about slavery. That’s based on the false premise that the motivations of individuals fighting in a war match those of the political leaders who are enlisting them to fight. They often do not. In this case, most of the soldiers who either volunteered or were drafted to fight for the Confederacy didn’t own slaves, but that doesn’t mean that the CSA didn’t secede from the U.S. to defend and perpetuate slavery. Nor does it necessarily mean that the non-slave-owning soldiers didn’t support slavery. But even if they didn’t, hundreds of letters prove that volunteers on both sides of the Civil War fought for reasons unrelated to bigger political contexts like preserving the Union, slavery or states’ rights, including boredom, showing off for women, honor, religion, etc. Once both sides ran out of volunteers and turned to conscription, then the soldiers’ motivations had even less to do with the political leaders.

Ex. 11: Based on the legislation they support, modern Democrats and Republicans seem to agree that higher voter participation favors Democrats. That’s not necessarily the case according to Shaw & Petrocik’s The Turnout Myth (2020). This may or may not be a false premise, but anyone that thinks or acts on it in either party should at least consider the premise carefully. Trump may have made a similar mistake in the 2020 election by opposing mail-in ballots: because they skew older, Republicans normally benefit from mail-in voting.

Ex. 12: Our first reaction is often to boycott international organizations like the WHO or Olympics (1980) when we oppose something that organization is doing or stands for or the host country. That is premised on the debatable, but not false, premise that boycotts are more effective than engagement.

Ex. 13: One purported appeal of racists is their “integrity” or that they “tell it like it is.” While ostensibly a defiance of undue political correctness, that idea is premised on two things: first, that, in reality but not spin, Whites are superior or claims of modern racism are overblown; and, second, that the people who disagree are not only wrong, but purposely lying about it (otherwise, integrity isn’t a distinguishing factor that sets apart racists). In other words, racially progressive people must agree, deep-down, with racists and are only claiming to think otherwise.

Ex. 14: There’s a school of realpolitik foreign policy theory that labels itself realists. Their quasi-isolationist angle of moderating our diplomatic ambitions and recognizing the potential depravity and bad faith of other actors isn’t necessarily without merit, but their name is based on two premises, the first irritating and the second debatable. First, their name suggests that everyone that disagrees is driven by idealism and insufficiently aware of the real world. But any theoretical school could claim this about other schools, because the reason anyone believes in anything is that they think it’s realistic, whether it is or not. In the case of foreign relations, an idealist could argue that our only realistic hope for long-term survival is total nuclear disarmament, and indeed self-styled realists like Henry Kissinger have argued just that. Realists contrast themselves with interventionist liberals like Woodrow Wilson and modern neoconservatives who thought American global hegemony was necessary for world peace. But whether they were right or wrong, interventionists’ motivation was based on what they saw as a realistic assessment, not to promote idealism (i.e. “look, the only realistic way to maintain stability is if the U.S. acts as world policeman.”). The second premise is more interesting: that idealism is necessarily ineffective. Is it really true? Regardless of what one thinks of organized religion, is it not the case that Jesus and Mohammad changed world history? Didn’t Gandhi and Martin Luther King impact civil rights with their idealism?

Ex. 15: The idea that the U.S. entered into peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese because of the 1968 Tet Offensive is premised on the idea that the battle was an American defeat. However, if the battle was actually a communist defeat, then it’s plausible that the U.S. was already willing to negotiate and it was actually the North Vietnamese who were ready for peace talks because of Tet. This is not only an example of a false premise, but potentially confuses cause and effect, our next topic.

Ex. 16: One of America’s longest and most epic environmental debates was over oil extraction in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), set aside by Eisenhower’s administration in Alaska’s North Slope in 1960. They started drilling in nearby Prudhoe Bay after 1968, hitting peak production in the 1970s when the state-long pipeline to Port Valdez was built. Everyone on both sides of the debate assumed that, if they opened up parts of the nature reserve, companies would bid to drill there, but only a few did. By the time Trump enabled that in 2017 (as pork in this tax bill), fossil fuel companies were cautious about long-term capital investments in oil since drivers were transitioning to electric and hybrid vehicles.

6. Confusing Association & Causation, or Cause-and-Effect

If A and B are simultaneous, or B occurs just after A, that doesn’t mean that A caused B (though it might have). The Latin term for the fallacy that if B follows A, A must have caused B is post hoc ergo propter hoc, usually just shortened to post hoc fallacy. Also, be wary of attributing an overly-essential relationship between two things that aren’t intrinsically connected (e.g., the New Deal and racism).

Ex. 1:

A. Pioneers moving onto the Great Plains cleared forests to grow crops.

B. It then rained a lot.

C. Chopping down trees makes it rain.

Unscrupulous real estate agents got a lot of mileage out this one among 19th-century European emigrants.

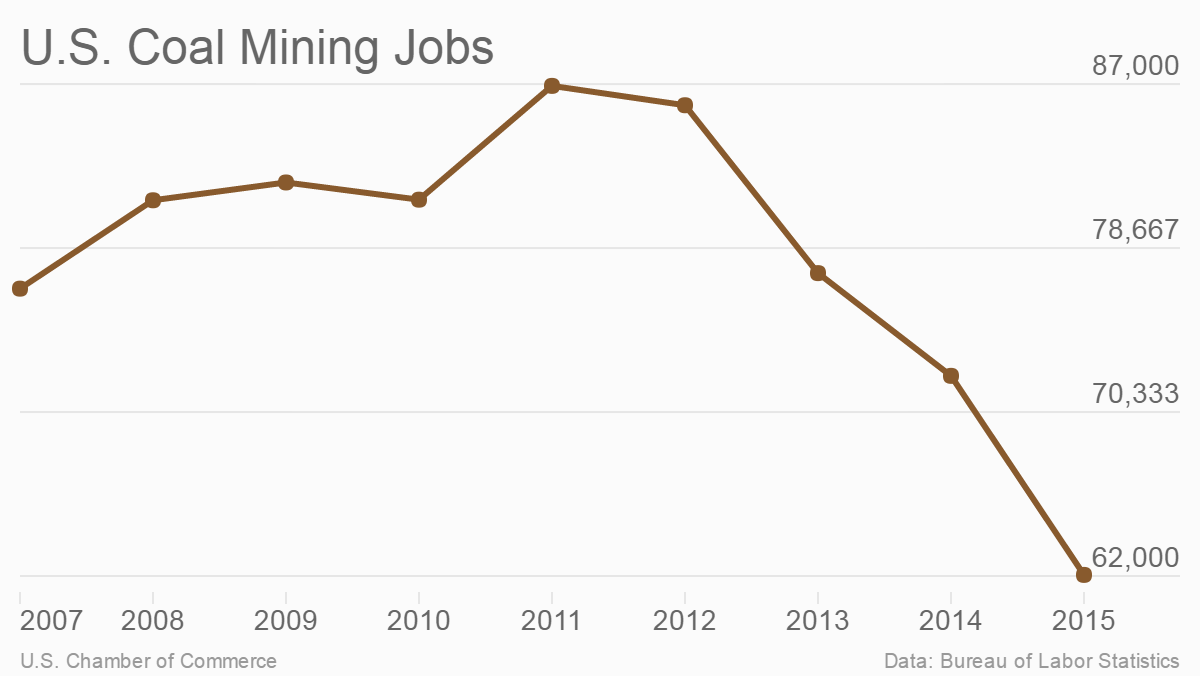

Ex. 2: Always be skeptical of, “well President so-and-so tried X, and we all saw what happened….” We might not have seen exactly what happened. Are we sure that the president’s action or mere presence in the Oval Office was the only thing acting on whatever phenomenon we’re talking about? Was the president even responsible for it happening in the first place, or was it something Congress passed and he signed (or overrode his veto), or something that happened in society while he/she was president? Also, presidents the impact of one president’s actions might not be felt until subsequent presidents are in office. Reality is complicated and political leaders aren’t Gods.

Ex. 3: Civil rights writer Ta-Nehisi Coates has implied, based mainly on New Deal racism, that there is an intrinsic (essential) connection between progressive, leftist politics and racism — that progressivism is inherently white. However, many minorities and civil rights leaders have been economic progressives, and there’s no reason to think that progressivism and racism are intrinsically linked. There’s no lasting causal relationship between leftist politics and racism, even though progressive Democrats of the 1930s had to forestall civil rights in order to bring Southern Democrats on board for the New Deal. If there is, we need to discover and do something about it.

Ex. 4: For critics of the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff, protectionism worsened the economic downturn of the Great Depression. Economist Paul Krugman argues that, while Smoot-Hawley was undoubtedly a moderate net loss (as is all protectionism for the broader population), such an interpretation confuses cause and effect. The decline in trade was even worse before Smoot-Hawley than after and was a result (not just cause) of the worsening recession.

Ex. 5: Issues involving equality of opportunity vs. equality of results/outcome naturally involve questions of cause-and-effect. Unequal hiring outcomes only prove discrimination if the group charging discrimination had the same number of applicants and same qualifications. There may be numerous other reasons why that wasn’t the case. The group being supposedly discriminated against has agency, too, and is acting (or could be acting) as a cause on the results, not just the effect. The EEOC v. Sears (1980-86) district court case is a good example, in which the the plaintiff charged Sears with discrimination because 50% of their sales staff, nationwide, weren’t female. They lost because they couldn’t prove that 50% of the applicants willing to work the long hours required of those jobs were female. The reasons why fewer women wanted to work longer hours is complicated, no doubt involving the demands of child-rearing, etc., but it would’ve been oversimplifying the situation to merely say the whole thing was Sears’ fault or that there’s no other explanation besides discrimination.

Ex. 6: Here’s a sentence with a couple of problems: “I think one of the biggest factors that caused the outbreak of the [Salem Witch] trials is that they were always accused of being women.” First, the fact that victims were often women is an attribute of the Salem Witch Trials, but not necessarily the cause of the trials, though misogyny is worth investigating as a factor. But if misogyny was the lone or primary cause there would’ve been witch trials going on wherever and whenever women have existed, which is everywhere all the time. Second, the problem wasn’t that suspected witches were accused of being women — anyone accused of being a witch rather than a warlock is female — but rather that women were disproportionately accused of being witches.

Ex. 7: Another head-scratcher: “If women gaining the right to vote was such an invaluable accomplishment for equality, then why were we such a better nation during the Early Republic than we are now?” This claim has a few problems. First, it’s premised on the fact that the early U.S. was a better country than the current U.S. That’s a matter of opinion, but one that many historians would contest, so it demands further explanation. Second, it’s one thing to argue that things were better during the Early Republic and quite another to argue that women being disenfranchised was why things were better. There might just be an association between those two phenomena rather than causation.

Ex. 8: Comedian Jon Stewart laid into Jim Cramer, host of MSNBC’s Mad Money, after the 2009-09 Financial Crisis, blaming the crisis partly on America’s obsession with the stock market. Encouraging retail investors to pick stocks on shows like Mad Money may not be sage advice, but the stock market collapse was an effect, not a cause, of the financial crisis, which originated in real estate and its derivative shadow market.

Ex. 9: The political structure of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy has similarities with the U.S. Constitution. And the American Founders (and Montesquieu, who influenced James Madison) were aware of the Iroquois and admired them. But it doesn’t follow that their political system directly influenced the Founders. We know what they were studying and reading about in the run-up to writing the Constitution. They were focused on Rome, Britain, and their own thirteen states, all of whom had their own constitutions. The Iroquois theory is more interesting; it’s just wrong. Indian republics should be appreciated in their own right.

Think through what you’re arguing. Before attributing B to A, analyze the connection between A and B.

7. Over-Generalizations

The following examples aren’t uniformly true just because they aren’t uniformly false. It’s nitpicky for sure (some might even call it “politically correct”), but if you don’t use adjectives like some or most, you are, in effect, using all. In cases like 1A or 1B, instead of reacting to the claim itself, just look around you.

Ex. 1: In his infamous January 6th (2021) speech, Trump urged his followers to take back their country by arguing “you built America!” Other groups argue the same thing, but no one demographic built America. The fact that lots of people contributed to America’s economy shouldn’t be too challenging to wrap one’s head around. If you’re skeptical about any particular demographic, let me know and I’ll fill you in on the basics.

Ex. 2: Southerners who switched from the Democrats to the Republicans in the late 20th century did so because they opposed the civil rights movement. Some, no doubt, actually opposed New Deal and Great Society liberalism for other reasons, though that’s difficult to believe for those viewing history through a single lens.

Ex. 3: Muslims want to kill infidels. It’s true that some do, but the vast, vast majority don’t.

8. Conflation (Lumping Together), Not Distinguishing Nuance, Mixing Apples-Oranges, non sequitur (Latin: “it doesn’t follow”), Red Herring

This can overlap with #7. Distinguish the various elements and nuance of an argument. Avoid conflating two distinct assertions and “mixing apples and oranges.” To do so deliberately is to “throw a red herring” into the argument.

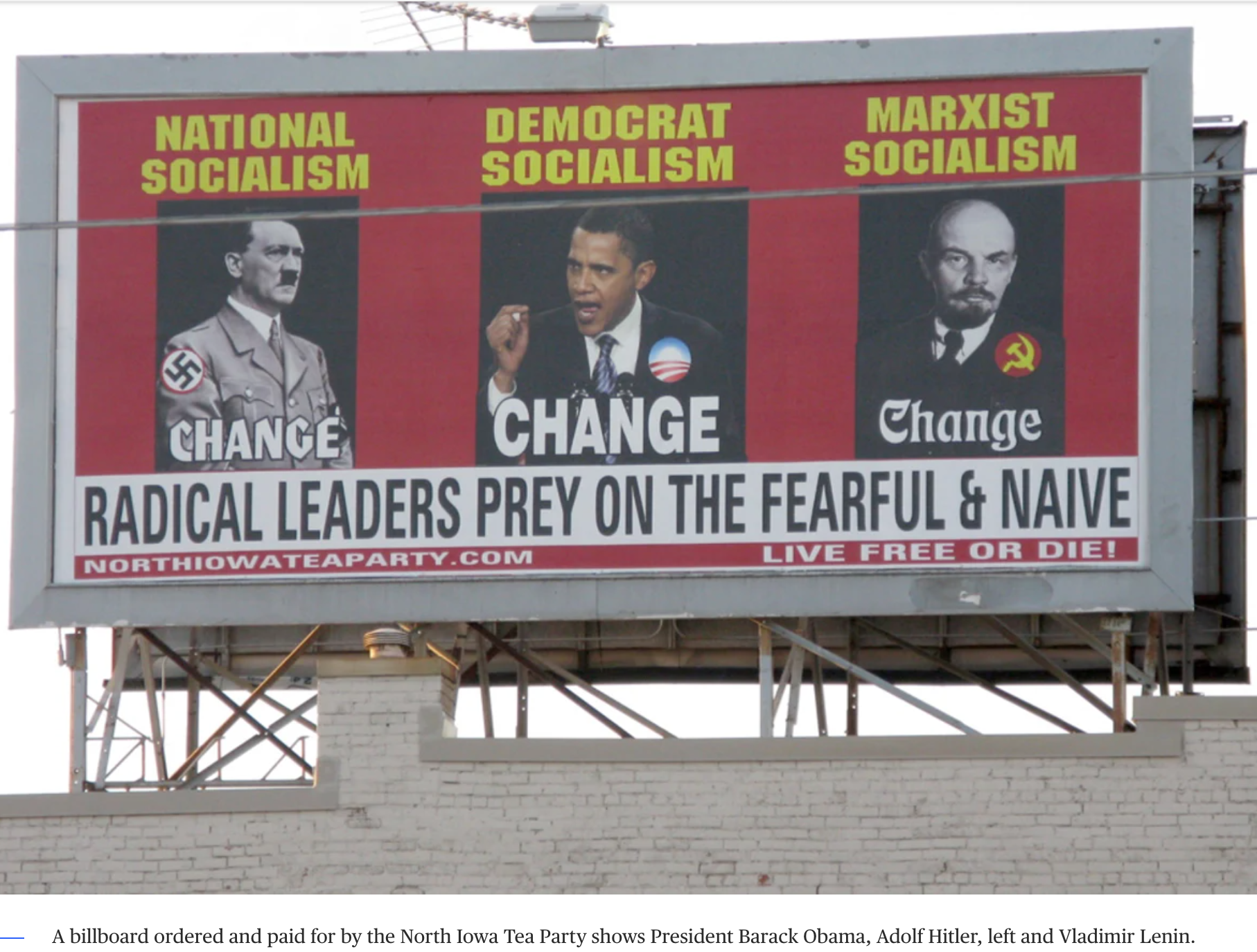

Ex. 1: The habit of Americans to compare everyone they disagree with to fascists. What do George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump have in common? All have been likened to Adolf Hitler. Granted, some Americans might have more fascist tendencies than others — truer now than ever as Trump threatens a “one-day dictatorship” if elected in 2024 — but, at least with politicians that don’t have real fascist inclinations, dare to have the fortitude, emotional restraint, and intellectual insight to consider that someone can disagree with you without being “just like Hitler.” And Trump isn’t like Hitler, either, for that matter despite seemingly favoring authoritarianism over democracy. Over-arguing that someone is a Nazi is so common in American society that it has a name: Reductio ad Hitlerum. This is partly a subset of basic association fallacy that occurs when someone is attacked or defended based on the idea that they have something in common positively or negatively with another person, group or idea. For instance, arguing that we should build highways isn’t the same as sanctioning the Holocaust even though the Nazis that perpetrated the Holocaust also built highways. Hitler breathed oxygen, too, but that doesn’t mean that you’re a Nazi if you also breath oxygen. This fallacy spun out of control during Barack Obama’s presidency as he was accused of Nazism simultaneously by the Occupy Wall Street left and Tea Party right for reasons seemingly unrelated to Hitler’s Germany.

Ex. 1: The habit of Americans to compare everyone they disagree with to fascists. What do George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump have in common? All have been likened to Adolf Hitler. Granted, some Americans might have more fascist tendencies than others — truer now than ever as Trump threatens a “one-day dictatorship” if elected in 2024 — but, at least with politicians that don’t have real fascist inclinations, dare to have the fortitude, emotional restraint, and intellectual insight to consider that someone can disagree with you without being “just like Hitler.” And Trump isn’t like Hitler, either, for that matter despite seemingly favoring authoritarianism over democracy. Over-arguing that someone is a Nazi is so common in American society that it has a name: Reductio ad Hitlerum. This is partly a subset of basic association fallacy that occurs when someone is attacked or defended based on the idea that they have something in common positively or negatively with another person, group or idea. For instance, arguing that we should build highways isn’t the same as sanctioning the Holocaust even though the Nazis that perpetrated the Holocaust also built highways. Hitler breathed oxygen, too, but that doesn’t mean that you’re a Nazi if you also breath oxygen. This fallacy spun out of control during Barack Obama’s presidency as he was accused of Nazism simultaneously by the Occupy Wall Street left and Tea Party right for reasons seemingly unrelated to Hitler’s Germany.

By then, Reductio ad Hitlerum was barely even an association fallacy, having diluted into a generic word used synonymously with something I disagree with for any reason or, simpler yet, a rule, by people with no real knowledge of Nazi Germany — core terminology for Edgelords making the news with outlandish claims. That would explain Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) complaining that COVID mask requirements on the House floor were “exactly the type of abuse” as Jews “being put in trains and taken to gas chambers in Nazi Germany.” Equating a perceived draconian or stupid rule with murder is an obvious false equivalent (see #4 above), but the joke is on us because we’re giving her attention. If true fascism ever emerges in the U.S., it’s safe to say it won’t be led by someone like Obama given that fascists hate liberalism and minorities, especially mixed-race ones like him.

Ex. 2: Arguing that enslaved workers helped build early America doesn’t mean one is endorsing slavery. Those are two different things.

Ex. 3: America was founded as a Christian nation because many of the Founders were Christian. The fact that many Founders were Christian does not mean that they legally enshrined Christianity as the official religion of the United States in the Constitution, just as the fact that many Founders were Deists doesn’t mean that they didn’t. The personal faith of Founders and what they enshrined legally in the Constitution are two different things. Both assertions might be true, both might be false, or the first might be true and the second false, or vice-versa; but in any event, they should not be conflated as the same assertion.

Ex. 4: Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) arguing that trickle-down economics works because he pulled himself up by the bootstraps. The two concepts overlap, sort of. They’re cousins, at least, and both concern economics and class. But people can pull themselves up by the bootstraps without trickle-down economics and effective trickle-down economics wouldn’t necessarily spur people to pull themselves up by the bootstraps.

Ex. 5: In his Pulitzer-prize winning book on polio, author David Oshinsky argues that some organizations exaggerated the threat in order to raise funds. Some readers have interpreted this as meaning that polio was a hoax. That’s not the case and not what the author argued. People can play up real threats to garner funds. It happens all the time in budgetary fights.

Ex. 6: During the 2016 campaign, we heard that Hillary Clinton was caught on tape saying that she wanted to overturn the Second Amendment (the right to bear arms). Two things here: 1. Presidents don’t pass or overturn Constitutional amendments. 2. She never said she wanted to; she said that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment in the D.C. v. Heller (2008) case was flawed, which many scholars agree with.

Ex. 7: Japan was close to surrendering at the end of World War II before the atomic attack because Einstein, Leo Szilard, and Admiral Leahy opposed using the atomic bombs. If you were compiling a list of reasons for and against bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, those two items might be in the same column, but A doesn’t follow from B. This is a non sequitur and “mixing of apples and oranges.”

Ex. 8: Some say the Civil War was about slavery but, in fact, the North was racist. That’s lumping together different parts of the issue. The second assertion doesn’t conflict with the first; they’re not mutually exclusive. It’s a non sequitur because A doesn’t follow from B. It’s also a false dichotomy.

9. False Dichotomy

Understand false choices: things that aren’t mutually exclusive.

Ex. 1: Many people are on one side or the other between sympathizing with black victims of police brutality or respecting the police and appreciating the difficulty of their tasks. However, the two ideas of respecting the police and expecting that they do their jobs properly aren’t mutually exclusive. All of you have brains big enough to encompass two ideas at the same time, including respecting police work while also recognizing and condemning police corruption and unnecessary brutality.

Ex. 2a: This example, popular in 2A sanctuaries, is relatively new in American society, as responsible gun-owners and the NRA supported common-sense regulations within living memory: we should arm civilians, including mentally-ill teenage boys, with military-grade weapons because “I like guns” and don’t want to revoke the Second Amendment. We can still allow people to hunt and own guns without selling bumped-up ARs to lunatics. This banks heavily on the slippery-slope theory (#19-3 below), especially considering that we’ve often had regulations before and no one outlawed hunting or, with the rare exception of Washington, D.C. and Chicago (since overturned by the Supreme Court), owning firearms for personal protection. If anything, we need more people hunting deer and wild boars, not less. A common retort is: “but we couldn’t completely stop the wrong people from getting semi-automatic rifles anyway.” True, but the question isn’t whether we would completely stop mass murders, but whether we would increase or decrease them with regulations. Maintaining the current situation of 500 mass shootings per year or zero mass murders is another false dichotomy. Don’t let perfection be the enemy of good. We don’t have laws in our society so that we can completely eliminate the crime. No is arguing, for instance, that since we still have murders, we should just give up and legalize murder.

Ex. 2b: After the Uvalde shooting in 2022, the Texas GOP said that we should focus on mental health instead of background checks, but those two things aren’t mutually exclusive. Guns are false choice-a-palooza. Mental health could even be part of background checks rather than something we focus on instead of background checks.

The following are edited examples drawn from anonymous papers:

Ex. 3: Many people think of spy work as glamorous but, in real life, it’s often one-sided. One-sided isn’t the opposite of glamorous. James Bond was glamorous, but he still worked for Her Majesty’s Secret Service, not UNICEF.

Ex. 4: America was not an imperialist country in the late 19th century because they were trying to expand trade and market access. There’s no contradiction between imperialism and economic growth. In fact, that’s why countries imperialize. It’s like saying “I didn’t beat my neighbor up because he deserved it for stealing my trash can.”

Ex. 5: Did the Americans win the Revolutionary War because of Washington’s tenacity, wit, and courage, or did the British just give up? Couldn’t the British have given up because of Washington’s tenacity, wit, and courage, or despite of or, more likely, because of reasons that didn’t have much to do with Washington?

Ex. 6: Many historians think that the battle of Saratoga was a game-changer because it brought the French into the Revolutionary War. Really, though, upstate New York remained contested between Rebels and Loyalists. The two ideas aren’t mutually exclusive; they could both be true.

Ex. 7: Columbus didn’t discover America because he thought he was heading to Asia (and/or still thought he was near Asia while in the Caribbean). Setting aside the fact that no European was first to “discover” America, did Columbus’ intent or geographical misconception really mean that he didn’t discover (from the European perspective) a new continent? No.

Ex. 8: I couldn’t discover anything about the author’s biases (for a book review) because he is still alive. Does an author have to be dead for a reviewer to uncover biases?

Ex. 9: A lot of people tend to think of economics on a left wing-right spectrum, but really a lot of emerging technologies come out of garages, like Steve Jobs’ Apple computer. What does that have to do with left and right?

Ex. 10: This one is a variation on Senator Hatch’s comment above, in #8-6: a student writes that Nancy Eisenberg’s White Trash examines how the class system has always existed in the U.S. even though the popular narrative is that America is a place where anyone can succeed. This is an example of a false dichotomy because someone could work their way up through the class system, and also an example of how one little word can change or nuance an argument. This statement wouldn’t be a false dichotomy if it said the book examines how a rigid class system has always existed in America.

Ex. 11: People credit the Arsenal of Democracy with protecting democracy and winning World War II, but really it was a boondoggle for profiteers. The two things aren’t mutually exclusive, so the BUT in the sentence should be an AND.

Ex. 12: I believe that Edward Snowden didn’t undermine national security because the public has the right to know what its intelligence community is doing. Again, not mutually exclusive. A more honest way to support the pro-Snowden thesis (if one were to take it) is to say that some undermining of national security is an acceptable cost for the benefit of more transparency among our intelligence agencies. Whether that undermining was real or hypothetical in this case is another matter.

Ex. 13: The U.S. claimed to expand further in the Pacific because of Manifest Destiny, but really it was unjustified. The idea it was unjustified is separate from whether or not it motivated them or not.

Ex. 14: The text explains the causes of World War I, but the outside article contradicts that by saying the war shouldn’t have happened. Ditto. If the textbook says that someone killed their neighbor because their dog was barking, that doesn’t that it’s arguing that they should’ve killed their neighbor because their dog was barking.

Ex. 15: Some people claim that the U.S. was unsure whether or not Japan would attack the Lower 48 but, in truth, the conditions at internment camps were horrible. The justification for the camps and their conditions are two different things.

Ex. 16: The textbook argues that the U. S. is trying to protect Taiwan, but the author of the article I read argues, instead, that these efforts backfired. Intent and impact are two different things.

Ex. 17: The textbook argues that Prohibition wasn’t properly enforced, but the article I read says that it was popular when they first passed the legislation. It’s popularity and effectiveness are two different things.

Ex. 18: Some say the New Deal hurt the poor via excise taxes, but really customers were protected by the FDIC. Taxes and banking are two different things.

Ex. 19: Roe v. Wade authorized abortions to women as a civil right, but the article contradicts that by mentioning that it should be illegal. Wishing that Roe v. Wade didn’t pass is different than arguing that it didn’t.

Ex. 20: Thomas DiLorenzo argues that the New Deal lengthened the Great Depression. The textbook agrees with that by saying that the Supreme Court ruled the NRA and AAA unconstitutional. The effectiveness of the New Deal is unrelated to whether SCOTUS thought it was unconstitutional.

Ex. 21: Was Christopher Columbus an intrepid explorer or ruthless exploiter? How about both?

10. Irrelevance

Make sure to “stay on point.” You don’t have time to meander. This will be important later as you deal with clients, customers, patients, etc.

11. Long Leaps of Logic

If you have to take a running jump, you might not make it over the mud puddle.

Ex. 1:

A. It’s ridiculous, and even downright arrogant, to suppose we are the only life in the universe. Undoubtedly the case. So far so good.

B. Therefore, aliens with one head, two arms and two legs (just like us) from outer space come here in spaceships to visit and suck blood and marrow from our cattle. Whoa, Nellie. That’s a mighty long way from A to B. It may be that humanoid-like aliens suck cow blood, but for a believer arguing with a skeptic, it doesn’t suffice to retort, “Do you really think we’re alone in the universe?” This is the same issue with Lumping Together and Conflation mentioned in #8. These are two different assertions and the second doesn’t necessarily follow from the first. The existence of money doesn’t mean that you just won the lottery.

Ex. 2: MS-13 is an Hispanic criminal gang, so Hispanics immigrating to the U.S. are criminals.

12. Anchor Bias

I learned it differently when I was young, therefore, you’re wrong now.

Ex. 1: A student raises his/her hand in class and says, “Actually that’s not true because I heard that….” except that they usually only imply and leave out the because I heard that. It’s possible the teacher is wrong but, either way, that has nothing to do with which order the listener hears something in. Why trust the first person you heard something from more than the second?

13. Bandwagon Effect

Believing something because lots of other people believe it.

“Groupthink,” as it’s often called, isn’t irrelevant — there might be a good reason an idea is popular — but the “hive mind” isn’t always right. Once upon a time, the majority thought the Earth was flat. Likewise, the fact that 99% of humans now think the Earth is spherical isn’t necessarily a good reason to agree, even though this time they’re right. Once an opinion gets up into the 99% range, you should at least consider hopping on the bandwagon, but you have every right not to. Either way, examine the evidence.

14a. Argument From Ignorance

Argument from ignorance has two distinct versions: It can assert that a proposition is true because it has not yet been proven false, or a proposition is false because it has not yet been proven true. Both are false dichotomies, or false choices. The first version often takes the form “If someone else can’t come up with a good explanation, then the answer is no doubt….”

Ex. 1: The master of this fallacy was German pseudo-archaeologist Erich von Däniken, who made a mint selling books like Chariots of the Gods? (1968) that basically argued that anything archaeologists couldn’t explain with down-to-Earth explanations was proof of “paleo-contact” with aliens. Unsurprisingly, he’d served time for fraud and embezzlement. In 2009, the “History Channel” launched a successful series called Ancient Aliens based on his theories. At Erich von Däniken’s conventions, in a renunciation of the scientific revolution, his followers chanted “reason sucks! reason sucks!”

Ex. 2: Regarding the Russia Hoax Hoax above (#2-9), the Mueller Report didn’t find any smoking guns; therefore, the Mueller Report exonerated Donald Trump. Anticipating this fallacy, the Report stated that it did not exonerate Trump, but the GOP spun it as such.

If you have a mystery that another person can’t explain or account for with a logical explanation, that doesn’t mean your highly specific supernatural explanation is right. It’s more likely that there are other options even if neither person is smart enough to suggest them. If you’re dog or toddler doesn’t know that 2+2=4, that doesn’t mean that it equals five.

14b. Argument From Authority

Argument from ignorance has a distant cousin called argument from authority (or appeal to authority), though their main similarities are in their names. See #5-2 above. Authority can mean something (in fact, today we’re too skeptical toward experts), but it’s not enough. Dwight Eisenhower’s granddaughter thinks that he signed treaties with Grays (aliens), but her being related to him isn’t enough to overcome her lack of good evidence for such a fantastic claim. Still, as fallacies go, be wary of this one, since as mentioned, it can cut both ways. You really should trust real doctors more than a witch doctors.

15. Confused Terminology

Read questions or analyze problems carefully by making sure what’s under discussion.

Ex. 1: What were some of the costly mistakes the South made during the Civil War? Answer: their army was too small. Their small army wasn’t really a mistake because they didn’t have a choice in the matter; it was more of a disadvantage that they had to cope with. A better example of a mistake would be Robert E. Lee’s decision to invade the North, which was arguably a poor decision (at least in hindsight — see #28 below). Mistakes involve choices.

16a. Focusing Effect & Reductionism

Historical events don’t have to happen for a single reason, so be wary of flattening interpretations by reducing to one factor or seeing things through singular lenses (e.g., economic, political, racial). History usually happens because of multiple forces acting simultaneously. When it comes to lenses, use a Swiss army knife whenever possible.

Ex. 1: The stock market dropped by 1% yesterday because of a decrease in new housing starts. More likely the 1% was the cumulative effect of thousands of different things acting on the market at the same time, including (maybe most prominently) news about housing.

Ex. 2: The Great Depression kicked in because of the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The crash was an important factor, no doubt, but there was already an ongoing recession caused by saturation of the durable goods market, a real estate slowdown, and erratic monetary policy from the Federal Reserve. Why limit yourself to one factor, as long as they don’t conflict?

Ex. 3: Some historians argue that the Salem Witch Trials happened because of frequent Indian attacks, while others argue they stemmed from economic tension or rivalries between denominations. Others argue they occurred because of the Puritans’ supernatural, fundamentalist worldview. Why ask which one is right? Because you’re trying to sell a book or compete for academic turf, that’s why. But for those interpreting the event, why couldn’t all those factors have contributed at the same time? Do they actually conflict?

Be open, instead, to the concept of the Perfect Storm. Things can (and most likely do) happen because of multiple factors occurring simultaneously. It’s possible as long as the causes aren’t mutually exclusive.

16b. Too Little Focusing: Applying Broad Principles From Specific Examples

Ex. 1: The failure of Prohibition demonstrates that “you can’t legislate morality.” Isn’t this just a catchy phrase our neurons associate with the singular example that the government failed to outlaw alcohol effectively? Turn this around by forgetting alcohol for a moment and asking yourself whether society has any laws that haven’t failed or aren’t unpopular that pertain to morality. “You can’t legislate morality” is far too broad of a claim to apply to all of history and society.

Ex. 2: The “Munich” effect. If the traditional thinking goes that western Allies should’ve confronted rather than appease Hitler in 1938, as they did with the Munich Pact, then we should always intervene without delay in every situation henceforth so as to not create a bigger problem down the road. But all situations are different. If applying historical lessons was as easy as the Munich crowd suggests, we would’ve figured things out long ago.

17. Framing Effect

Consider the angle or spin of how things have been presented to you. What’s been included? What’s been left out? All arts of manipulation are based on framing, including political campaigning, selling, and (especially) marketing. Advertisers, salesmen, and carnies specialize in framing and magicians take it to extremes as it’s their main modus operandi (m.o.). They understand our mental “tire ruts.” Politicians must learn to manipulate voters’ views through framing to win elections. For all these vocations, framing enabled by our gullibility is the key to their livelihood — so much so that the economy might collapse if we wised up. Mark Twain’s fictional Tom Sawyer got his friends to help him paint a fence by framing it as being fun. Consider how the same movie or restaurant recommendation sounds coming from someone you respect versus someone you disrespect. If a doctor prescribes 24 antibiotic pills of the same color, the patient will usually quit taking them when they feel better, even if there are some left. But if the doctor instructs the patient to take 18 white pills first, then finish up by taking 6 blues, they’ll finish the prescription. One study showed that people like an ice cream called Frosh considerably better than the same ice cream when called Frish. Why? Because the o sound is “bigger and creamier” whereas the latter sounds like fish. A 2012 study at Washington University showed that 222 MBA students (45 female) who were shown prospectuses of the same company — except with some examples listing a female CEO and others a male CEO — overwhelmingly described the finances of the company being run by a female as being in worse shape. When a 2015 study asked a group of white Americans how much they think black Americans earn per year on average, the average response was around $29k. However, when the same group was asked later in the same study how much African Americans earned, the figure jumped to $37k. Framing is also important in historical interpretation and lies at the heart of partisan hypocrisy (liberals and conservatives predictably like or dislike policies based on whether it’s coming from the mouth of a Democrat or Republican).

Ex. 1: Andrew Jackson is often criticized for his Indian Removal policy, and justifiably so. The Trail of Tears, which occurred under his successor (Van Buren) but was a direct result of his policy, was unnecessarily cruel. Yet, if you zoom out with the camera and take a longer view, Jackson’s Indian policies were part of a consistent overall policy started by the Founding Fathers continuing on through Abraham Lincoln and U.S. Grant. Should Jackson be singled out as the president we blame Indian policy on while ignoring the topic altogether when talking about those on Mt. Rushmore like Washington, Jefferson or Lincoln?

As demonstrated in examples #2-5 below, studies show that when Democrats and Republicans are shown various political options and policies, the biggest determining factor in whether they favor or oppose the policy is whether there is a (D) or (R) next to the name of whoever is introducing the idea. Usually, voters will switch their opinions if the idea gets associated with the rival tribe.

Ex. 2: Many Americans who opposed “‘Obamacare” liked the main features of the 2009 Patient Protection & Affordable Healthcare Act. Why, if they were the same thing? Because of how the question was framed. When it was called “Obamacare” the question really concerned whether or not one liked Obama. Conservatives introduced and promoted the idea of mandates and healthcare exchanges, then turned against the bill passed and signed by a Democratic congress and president. Zero Republicans voted for the ACA. At that point, the “market-based solution” they’d promoted in earlier debates transformed into big government-run “socialized medicine.”

Ex. 3: Likewise, in a study by Ariel Edwards-Levy, Republican voters were asked whether the economy had improved between 2008-9 (the height of the financial crisis) and 2016. Most thought it had, but the numbers dropped 20% when they were asked later in the same questionnaire whether the economy had improved during Barack Obama’s presidency (the same years).