“This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am president it shall be a government for white men” — Andrew Johnson, U.S. President (1865-69)

Reconstruction is a generic term to describe the rebuilding of any country after a war or natural disaster. For instance, there was a reconstruction after World War II or in Afghanistan and Iraq. In American history, though, Reconstruction with a capital R describes the rebuilding of the South after the Civil War, from 1865-1877. Eighteen-Seventy-Seven doesn’t mark a resolution of any important issues — those are ongoing — but rather the end of the Union Army’s occupation of the South.

The end of the Civil War wasn’t an opportune time to have a president assassinated, as Abraham Lincoln was, especially since his VP Andrew Johnson wasn’t well suited to the task. Whether things would’ve gone better had Lincoln lived we’ll never know, but even the Great Emancipator would’ve struggled mightily with the challenges presented by Reconstruction. Toward the beginning of the war, Lincoln hadn’t tried to ram abolition down Southerner’s throats the way many GOP politicians wanted, saying that direct reform efforts wouldn’t work better than trying to “penetrate the hard shell of a tortoise with a rye straw.” He hoped, instead, to win them over to his cause by reaching their hearts. That didn’t happen. After the war, Southerners were demoralized and they resented those that had been freed and those that freed them.

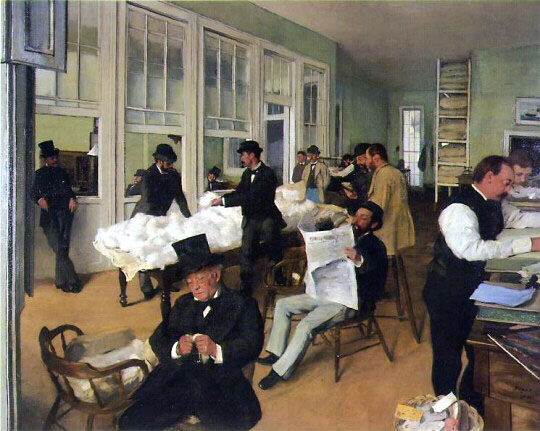

The southern economy was in tatters, the Union Army had wreaked havoc in some areas, and Confederate “greyback” currency was worthless. Black freedom translated into a sudden financial loss for Whites ~ $13 trillion in 2016 dollars (source). Mississippi went from being the richest state in the country per capita for Whites to the poorest. Even if the economy could recover — and cotton exporting did survive and thrive — the regional psyche wasn’t about to heal quickly or easily. Slavery, the linchpin of the South’s economy and social structure, had ended suddenly. The southern U.S. in 1865 was hardly an ideal place for one of the modern world’s early experiments in interracial democracy and, on that score, the North had nothing to offer but its own history of discrimination and segregation toward free Blacks. Places like Cincinnati’s Little Africa and Boston’s [N-word] Hill mainly symbolized that the North had only abolished slavery less than a century earlier. As historian C. Vann Woodward pointed out in The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955), the antebellum North provided a rough template for what transpired more dramatically in the South in the century following the war.

Two overlapping questions were at stake. The first was how, and under what conditions, would southern states be allowed to rejoin the country. That may seem like an odd question since the Union had fought the war to prevent them from leaving. But the Union acknowledged Confederate nationhood in 1863 and there’s a saying in war, that to the victors go the spoils. The North had the leverage to make reentry conditional on Southerners either demonstrating loyalty to the U.S. or in treating Blacks in accordance with new constitutional amendments. Either prospect was grim for many white Southerners. Lincoln advised requiring just 10% of citizens in any given state to sign loyalty oaths before readmitting that state whereas congressional Republicans favored 50%. Toward the end of his life, Lincoln advocated suffrage for literate Blacks and veterans and Congress agreed. That was John Wilkes Booth’s immediate motivation for killing him in April, 1865.

But Congress was in recess in the summer of 1865, leaving President Johnson in charge. Johnson didn’t support Blacks being granted basic civil rights. Johnson tellingly refused to use the term reconstruction, preferring restoration. The extent of those civil rights, or lack thereof, was the second big question posed by Reconstruction: how would Freedmen, as formerly enslaved people were known, fit into society? By June 1865, word of the Confederacy’s loss and emancipation had reached across the South. How would Southern states re-integrate into the U.S. and how would Freedmen be treated?

Jim Crow

Seemingly getting the green light, with no direct communication from Congress otherwise, southern states passed laws called Black Codes returning Freedmen to conditions as closely approximating slavery as possible without actually including ownership. It was illegal for Blacks to be unemployed, but they could only work jobs that Whites wanted them to work — mainly the same tasks they’d done when enslaved. Blacks couldn’t stay out past curfews, own guns, vote, or hold office. If Whites felt black parents weren’t raising their children correctly they could assume guardianship of the children and hold them as apprentice servants.

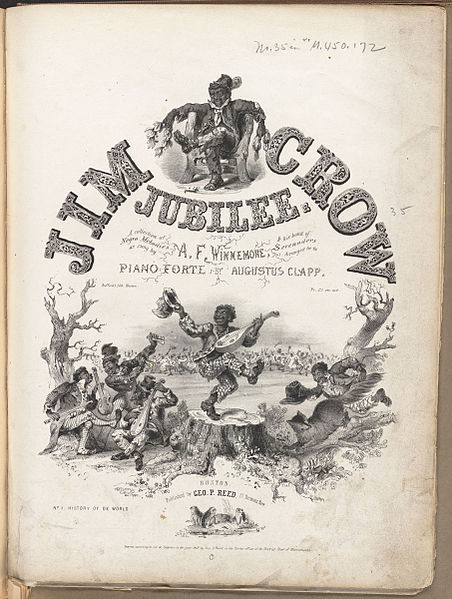

These laws varied depending on the specific locale and state and, as we’ll see below, Blacks could initially vote in some areas. Later, they were known collectively as Jim Crow laws after a popular character in black minstrel shows. The poster on the left isn’t from the South during Reconstruction; it’s from Boston in 1847. In some places, there was conflict between politicians. Republicans in Louisiana objected to Democrats passing a new constitution with strict black codes and the ensuing Mechanics’ Institute Massacre of 1866 led to nearly 300 casualties, most of them Freedmen. Not only did Black Codes vary from place to place, but the black population was mobile. They experienced emancipation for the first time in many areas only when the war ended, not when Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and they were traveling all over trying to locate lost relatives sold to other plantations before the war.

When Congress returned to Washington in the fall of 1865, Radical Republicans led by Thaddeus Stevens were disgruntled with the Black Codes and Johnson, setting the stage for the biggest showdown between the legislative and executive branches up until then. Republicans showed no mercy for “unreconstructed rebels.” Under a program known as Radical Reconstruction, they disenfranchised former Confederate leaders, confiscated some planters’ land, and returned it to the former enslaved people who’d worked it for generations. With the 40 Acres-and-a-Mule plan initiated during the war on Sherman’s March, that land would be redistributed to Freedmen as small family farms. At least that was the idea of Sherman’s Special Field Orders, No. 15 in South Carolina, Georgia, and northern Florida. Even when these transfers actually occurred, Blacks would unknowingly borrow money in the spring at 5000% interest (one of the many disadvantages of illiteracy) and then be virtually owned by the lender as debt peons when they harvested in the fall. Either way, President Johnson revoked the redistribution policy before it ever transferred much land.

Most Blacks ended up as tenant farmers or sharecroppers, many in the same cotton fields they’d worked before the war. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, as long as they were being paid, but Whites blocked other jobs and any avenues of bettering one’s station. In Virginia, for instance, planters thumb-cuffed Freedmen that wouldn’t agree to work their fields for $6/month (< $100 today). Similar to European peasants, sharecroppers worked others’ land, keeping a portion of the crops for themselves (the tenant) and paying rent with the rest, often 50%. This was the fate of most southern Blacks, at least those that escaped prison chain gangs, along with huge numbers of poor Whites.

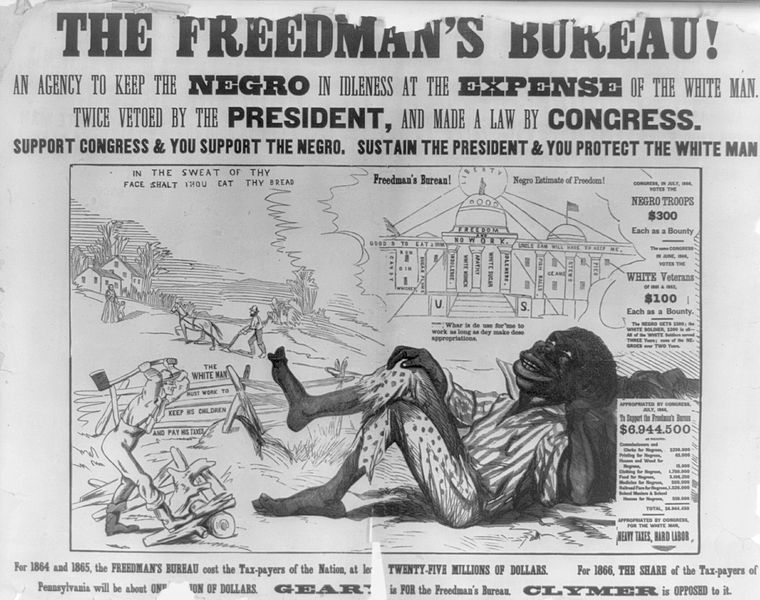

Cotton didn’t go away because of the Civil War. Production expanded, in fact, though cotton never regained its status in proportion to the rest of the economy as northern industry grew. Meanwhile, the advent of mechanized agriculture in the early 20th century displaced sharecroppers (black and white), forcing many to seek factory work in cities. Radical Republicans also overcame Johnson’s veto and set up Freedmen’s Bureaus to help Blacks attain food and clothing, rudimentary healthcare and educations, legal aid, and help locating lost family members.

Freedmen’s Bureaus did some good but lacked adequate funding and were lampooned by critics as a waste of time. Of course, their critics also didn’t think Blacks had the right to educations, healthcare, or courtrooms in the first place. While the bureaus were well-intended, some of the Republican policies in the South probably had more to do with vindictiveness toward the Confederacy than genuine concern for the welfare of Freedmen. Tapping into the religious undertones Lincoln expressed in various speeches, Radical Republicans preached “regeneration before reconstruction” whereas President Johnson advocated less rigorous “restoration.” Unlike Johnson, Congressional Republicans wanted certain Southerners, namely Confederate leaders and big planters, to atone for their sins. But at no point during Reconstruction did they roll out a red carpet and invite Freedmen to come north and compete for jobs. That didn’t happen until around World War I and, when it did, racial conflict came with it. Prior to the Civil War, northern Republicans had preached the upside of a racially purified, all-white society.

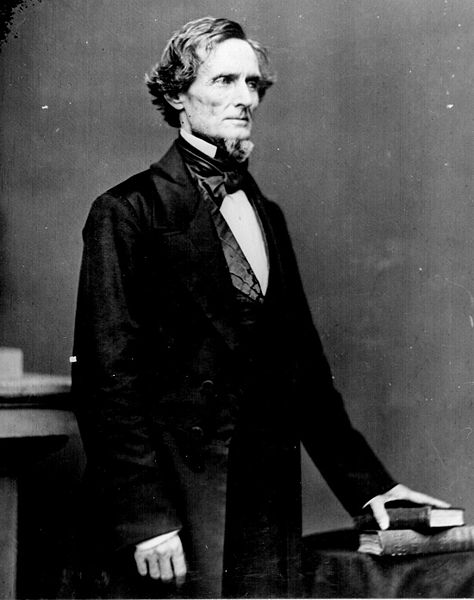

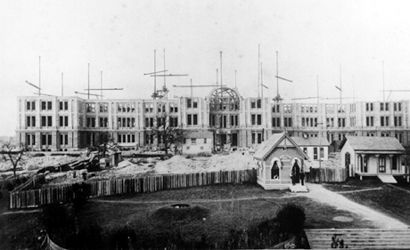

In some places, Black Codes held while in others the rich planters really did lose power and Blacks were elected to legislatures. Laws permitting black men to vote paved the way for the Fifteenth Amendment and were really what defined the radical in the late 1860s phase known as “Radical Reconstruction.” There were 2k Blacks in southern statehouses from 1868 to 1875 — more than at any time in history, including the present. In this topsy-turvy world, African-American Hiram Revels even replaced former Confederate President Jefferson Davis as a Senator from Mississippi. Since the federal government was giving out land grants to states to build colleges, a formerly enslaved man from Fredericksburg and Giddings, Texas named Matthew Gaines secured the charter to build Texas A&M University near a train stop later called College Station. A coalition of liberal history professors and College Republicans put the wheels in motion to finally get Gaines’ statue built on campus in the early 2020s.

Amendments & Impeachment

To counter Black Codes, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act (1866) and the Military Reconstruction Act (1867) that were designed to support black citizenship but weren’t properly or uniformly enforced. With the southern states not voting anyway, even as they had representatives that sat in Congress, Northern Republicans ensconced those civil rights more permanently by passing constitutional amendments. The Thirteenth had already passed in 1865, ending slavery. Now the Fourteenth Amendment of 1868, sometimes called the Civil Rights Amendment, granted basic rights of citizenship to all Americans by forcing states to honor most rights guaranteed in the Bill of Rights. Prior to the Fourteenth, the Bill of Rights applied only against the national government, not against state governments, meaning that states — especially the original thirteen, but also southern states after the Civil War — could abridge their citizens’ rights to freedom of religion, speech, fair and speedy trials, etc. James Madison tried to get an amendment passed in 1791 to apply the Bill of Rights against states but it failed the Senate after passing the House, and SCOTUS ruled against applying them within states in Barron v. Baltimore (1833). After Reconstruction, most of the Bill of Rights were gradually incorporated at the state level, with one initial exception being the Second Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment, like the Civil War itself, strengthened the national government at the expense of states, resetting American history as part of what historian Eric Foner called the Second Founding. The “Congress shall make no law…” restraining, strict-constructionist theme of the Constitution gave way to a looser “Congress shall have the power to…” This Constitutional reboot is one of the most profound impacts of the Civil War. Whereas many Founders envisioned the states as the true protectors of liberty and the national government a necessary evil they grudgingly went along with — with the Second Amendment as the ultimate expression of that outlook — it turns out the states were the real menace to democracy and the national government was the emancipator and guarantor of civil rights. The Fourteenth Amendment turned Reconstruction into an ongoing process that outlasted the period from 1865-1877 and today it is the most important overall amendment in court cases involving a wide range of issues.

While the U.S. chose not to charge Confederates with treason or pursue war crimes against them for the most part (Andersonville POW Commandant Henry Wirz was an exception), the Fourteenth punished the South directly, with its third section denying ex-Confederates the right to serve in office and fourth section requiring that southern states pay the Union’s war debt. Both objectives were dead letters by 1868, though they remain in the Constitution to this day like vestigial organs.

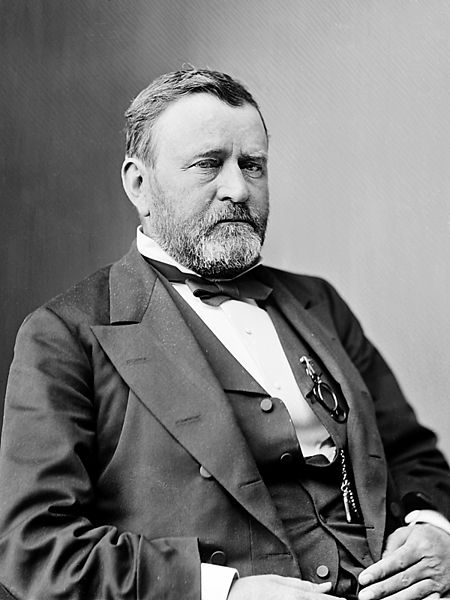

Complicating an already difficult phase of American history, early Reconstruction played out under Andrew Johnson’s chaotic presidency. Johnson drank heavily and even suggested during his “Swing Around the Circle [speaking] Tour” (below, with Ulysses S. Grant to his left) that he wished the Confederacy had won the Civil War, all the while suppressing reports of southern black murders and tortures in the northern press. See the quote at the top of the chapter. Journalist Adam Serwer wrote that, convinced most of the country was on his side, the president “gave angry speeches before raucous crowds, comparing himself to Lincoln, calling for some Radical Republicans to be hanged as traitors, and blaming [the] New Orleans riot on those who had called for Black suffrage in the first place, saying, ‘Every drop of blood that was shed is upon their skirts and they are responsible.’ He blocked the measures that Congress took up to protect the rights of the emancipated, describing them as racist against white people. He told Black leaders that he was their ‘Moses,’ even as he denied their aspirations to full citizenship.” Johnson’s rabid racism made him a poor choice as Lincoln’s second VP, even though it’s understandable why Lincoln ran on a mixed ticket in 1864.

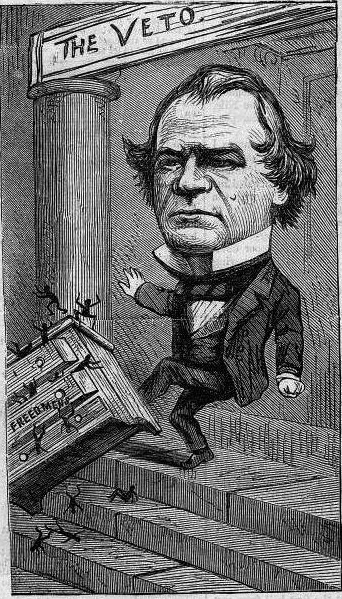

Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment and vowed to obstruct its passage, just as he’d gone out of his way to block the Freedmen’s Bureaus and not enforce the earlier civil rights laws while complaining loudly about the “Africanization” of the country. He also didn’t support any potential Fifteenth Amendment granting Blacks the vote, and even seemed to question the legality of Congress since representation hadn’t been restored to all Southern states. Presidents don’t have an actual Constitutional (legal, official) role in the amendment process, but their support or opposition can sometimes influence their passage. President Johnson’s opposition to civil rights was the real reason House Republicans impeached him, though they trumped up technical charges concerning the illegal way he’d replaced one of Lincoln’s cabinet members (Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War) in violation of their new Tenure of Office Act. Some Republicans also feared that President Johnson, as commander-in-chief, might lead a coup d’etat using the Army to back a new Congress of allied northern and southern Democrats, kicking out the Republicans. Of the eleven articles of impeachment drawn up against Johnson, nine concerned the Tenure of Office Act. The other two focused on Reconstruction and his general insubordination and abuse of power — for bringing “disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach,” onto “the Congress of the United States” and for his “intemperate, inflammatory and scandalous harangues, and therein utter loud threats and bitter menaces, as well against Congress as the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries, jeers, and laughter of the multitudes then assembled in hearing.”

Johnson opposed the Fourteenth Amendment and vowed to obstruct its passage, just as he’d gone out of his way to block the Freedmen’s Bureaus and not enforce the earlier civil rights laws while complaining loudly about the “Africanization” of the country. He also didn’t support any potential Fifteenth Amendment granting Blacks the vote, and even seemed to question the legality of Congress since representation hadn’t been restored to all Southern states. Presidents don’t have an actual Constitutional (legal, official) role in the amendment process, but their support or opposition can sometimes influence their passage. President Johnson’s opposition to civil rights was the real reason House Republicans impeached him, though they trumped up technical charges concerning the illegal way he’d replaced one of Lincoln’s cabinet members (Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War) in violation of their new Tenure of Office Act. Some Republicans also feared that President Johnson, as commander-in-chief, might lead a coup d’etat using the Army to back a new Congress of allied northern and southern Democrats, kicking out the Republicans. Of the eleven articles of impeachment drawn up against Johnson, nine concerned the Tenure of Office Act. The other two focused on Reconstruction and his general insubordination and abuse of power — for bringing “disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach,” onto “the Congress of the United States” and for his “intemperate, inflammatory and scandalous harangues, and therein utter loud threats and bitter menaces, as well against Congress as the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries, jeers, and laughter of the multitudes then assembled in hearing.”

When Johnson backed down on his Reconstruction policy, the Senate allowed him to escape in their trial – the next phase of the process after the House impeaches a president. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court presides over the Senate trial, which requires a two-thirds vote to remove a president from office. Four presidents have been impeached in American history: Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump escaped conviction in the Senate trial phase (Johnson by just one vote and Clinton and Trump 2x by huge margins), and Richard Nixon preemptively resigned as the House drew up articles of impeachment. Besides passing the word that he was done opposing Reconstruction, another factor that saved Andrew Johnson was that the president pro tempore of the Senate who stood to replace him, Benjamin Wade, favored women’s suffrage, which most Senators didn’t (there was no VP, as Lincoln’s assassination vacated that office).

Since some southern states passed legislation to keep African Americans from voting, the Fifteenth Amendment was added to secure black suffrage in 1870. Northern Republicans needed the southern black vote if enslaved workers were freed; otherwise, they could potentially form an alliance with southern Whites and constitute a threat to northern hegemony. It was important then, for Blacks to know that northern Republicans had been the ones responsible for backing their suffrage. Conversely, one reason for Southerners’ continued opposition to a constitutional amendment replacing the electoral college with a popular vote for president was their fear that northern politicians would more readily appeal directly to black voters if, that is, they could vote. In any event, the Fifteenth Amendment only secured black male suffrage, since women didn’t have the right to vote yet. The Fifteenth stated that the vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Passage of these Civil War Amendments gets to the heart of why it was advantageous to keep former Confederate states out of the Union temporarily. Radical Republicans argued that the Confederacy had, in practice, formed its own polity, which not only rationalized the victorious North imposing its will on southern states with occupying forces, but had the added advantage of allowing northern states to pass important Constitutional amendments. It requires ¾ of the states to pass an amendment and none of them would’ve ever passed if the former Confederacy had voting seats in Congress after the war. Even with that advantage, the Thirteenth Amendment barely passed anyway. The Confederate states’ condition of readmission, then, was signing off on the new amendments, as Texas did in 1870. In the meantime, the ongoing, if limited, Union military occupation (per the Military Reconstruction Act) kept the South in line as the amendments passed and the southern states only had non-voting seats in Congress. The U.S. Army had less than 30k troops after the war, though, with most in the West fighting Native Americans.

Reduced Version of “The Fifteenth Amendment, Celebrated May 19th, 1870,” Published & Printed by Thomas Kelly

However, passing amendments is one thing, and enforcing and interpreting them is another. There’s always some wiggle room and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth were notorious exceptions. The Fourteenth outlawed states (state governments) from discriminating based on race, but what about the people that lived within states and ran private stores, inns, or restaurants? The Fifteenth outlawed denying votes based on race, but what about denying votes to everyone whose grandparents had been enslaved (the Grandfather Clause), or everyone who couldn’t read with a special exemption for Whites who couldn’t, or how about charging poll taxes with a special exemption for Whites who couldn’t afford it? None of these were explicitly outlawed by the Fifteenth, at least not as long as the Supreme Court was in a “healing mood” from the Civil War.

The ensuing subversion of the Fifteenth Amendment — despite the support of at least one president in Republican Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893) — didn’t just thwart democracy for millions of African-American men, it also warped the entire political system. Earlier in the course, we talked about the 3/5th’s compromise, whereby southern states were allowed to count 60% of their enslaved workforce for purposes of representation even though the enslaved couldn’t vote. After the Civil War, they enjoyed what historians call the “5/5th’s compromise” as long as they could prevent Blacks from voting, since Freedmen now fully counted in determining population for representation (how many congressmen a state had in the House of Representatives). This was not just a subversion of the Fifteenth Amendment, but also the Fourteenth, Section 2 of which was written to prevent this very problem. Historian Alexander Keyssar noted how this scam swung power to white Southerners: “In 1904, for example, Delaware had cast roughly the same number of votes for Congress as Georgia had, but Georgia had eleven representatives while Delaware had only one.” These same southern Democrats made sure that Section 2 of the Fourteenth went unenforced.

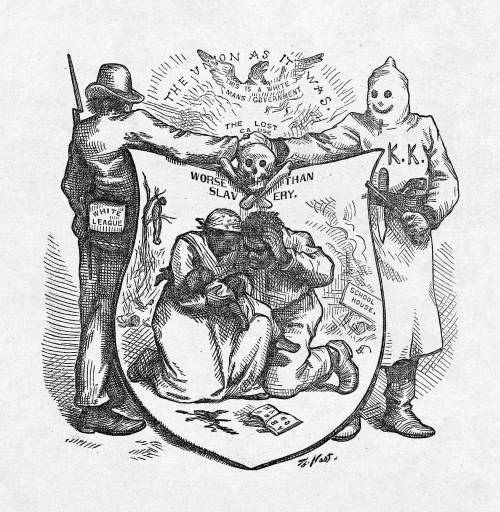

The Title Alludes to the Old 1862 Copperhead Campaign Slogan “The Union as it was, the Constitution as it is.” Cartoon by Thomas Nast, 1874, Harper’s Weekly

Vigilantism & Southern Redemption

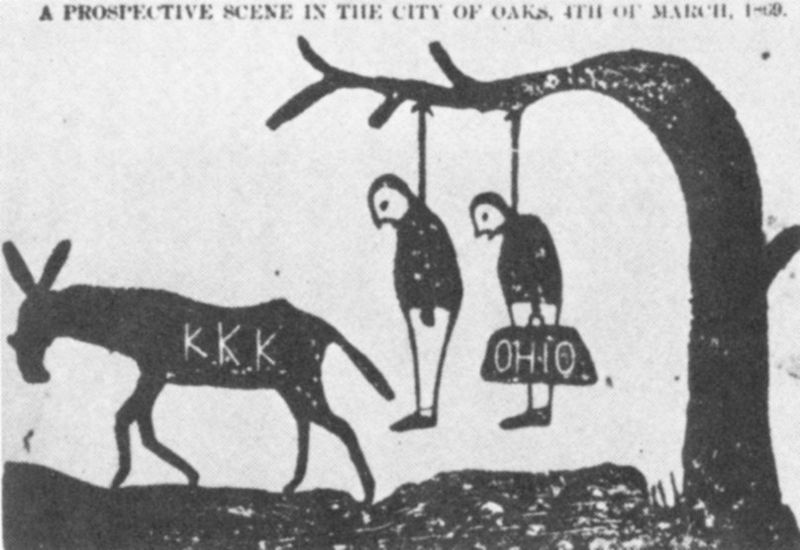

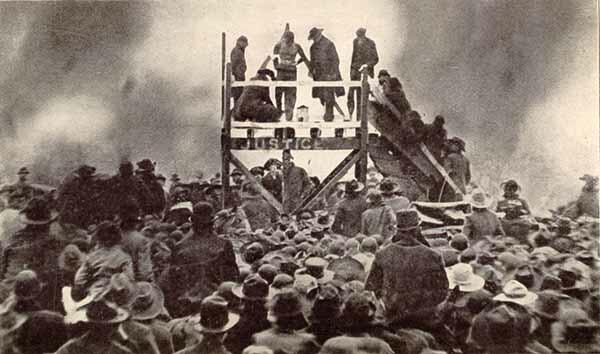

Finally, what about people taking the law into their own hands and simply beating up, torturing, or killing black voters? That was the preferred tactic of vigilante groups that arose to defend the South in the absence of the Confederate Army. White League, Red Shirts, Knights of the White Camellia, White Liners, and Ku Klux Klan sometimes fought directly against Union forces as paramilitary groups, especially in the more contested Upper South. This is when northern judges began interpreting the Second Amendment as based on individual gun ownership rights, in order to prevent southern states from using the Constitution to form militias. The Klan’s first incarnation started in Tennessee, the White League in Grant Parish, Louisiana, and the Red Shirts in Mississippi and South Carolina. Instead of fighting Union troops directly, though, these “rifle clubs” (often comprised of Confederate veterans) usually intimidated black and white Republican voters, purportedly including carpetbagger businessmen from the North who scooped up cheap, confiscated land and charged high rent to white sharecroppers. There isn’t much primary source evidence to support the existence of carpetbaggers, but a few must have existed to fuel the legend. Carpetbagger also applied to northern transplant Republicans serving in southern legislatures, including some free Blacks and enslaved escapees returning to their home states.

The Klan’s tactics included rape, genital mutilation, and murder, the reports of which some southern newspapers glorified (above) or dismissed as “fairy tales.” One ostensible purpose of the vigilantes was to protect the honor of white girls from black men, who would presumably rape them once freed from slavery. White plantation owners had free access to their enslaved females for centuries, so people expected some retribution, though it never materialized in disproportionate numbers.

Another purpose of the Klan was to seize guns from Blacks and deny them the right to own weapons. To save the government money, free Blacks that fought for the Union during the Civil War had often been allowed to keep their rifle instead of receiving their last paycheck. The phrase about prying guns from one’s “cold dead hands” made famous by NRA President Charlton Heston in 2000 originated among Freedmen during Reconstruction. As mentioned, interpreting the Second Amendment as concerning individual rights instead of state militias originated during the Civil War era with northern judges downplaying the right of Southern states to form militias, and to help Freedmen secure Second Amendment rights, via the Fourteenth. However, the Second wasn’t officially incorporated against the states until McDonald v. Chicago (2010). Had 2A applied in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Blacks could’ve owned weapons throughout the country.

Not all former Confederates agreed with prolonging resistance to northern rule. John Singleton Mosby, a cavalry battalion commander in the Civil War known as the “Gray Ghost,” thought that Republicans offered the South the best hope to rebuild their society. Mosby went to work for the Grant administration as a lawyer then served as ambassador to Hong Kong. Many Southerners, however, stuck with the Democrats and a sizable minority with vigilante groups.

The Klan branded itself along themes similar to groups that arose in Scotland in previous centuries — many rural Americans were of Scotch-Irish ancestry — but mostly traced their lineage to America’s Anglo-Saxon founders. They dressed in hoods to scare Blacks into thinking they were ghosts of dead Confederate soldiers coming back to haunt them. Just as Nazis appropriated the previously peaceful swastika symbol, the Klan used conical hats similar to the capirote worn in Spain on Easter to represent equality and anonymity during confession. Union forces confronted the KKK, virtually dismantling the original “social club” by enforcing Ulysses S. Grant’s 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act. Some Klansmen even escaped to Canada, of all places. A new Klan emerged around 1915. But eventually, President Grant instructed Union forces to stand down and they ceded territory to the other vigilantes. While Grant had the reputation for being “the Butcher” because of the ruthlessness of the Vicksburg and Overland Campaigns, his battlefield experiences only made him hate war. The last thing he wanted under his presidency was a resumption of the Civil War. Obviously, at some point, Southerners would end up controlling the South; the Union couldn’t occupy the region forever.

Just before he left office, on Christmas Day 1868, President Andrew Johnson offered amnesty to all Confederates. Under Grant, they returned to power. In 1872, Congress granted ex-Confederates amnesty from Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which bars from office anyone who has engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the U.S. that has previously sworn to uphold the Constitution (this is the section that Colorado’s Supreme Court used to bar Trump from running in that state’s primary in 2024). Former Confederates won back control of most areas by the early 1870s, with the understanding that they couldn’t re-institute slavery. They were led by Yellow Dog Democrats who favored voting for former Confederates, even a cowardly “yellow dog,” over anyone else. While Republicans briefly controlled South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida backed by federal troops, Democratic Redeemer governments won control of the entire Southeast by 1877, and they disenfranchised black male voters. Redemptionists redeemed Whites from the “negro misrule” of early Reconstruction. Mississippi’s 1890 constitutional convention put it bluntly: “Let us tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the Universe…We came here to exclude the negro. Nothing short of that will answer.” Despite their party’s name, the Redeemer Democrats subverted bona fide democracy in favor of an apartheid-like system that ruled through violence and intimidation. Their counter-revolutionary success is why some historians claim the North won the war, but the South won Reconstruction.

In Wilmington, North Carolina in 1898, for instance, 2k white Democrats overthrew an elected bi-racial Fusionist government (Republicans and Populists), killing hundreds and burning down a black-owned newspaper and the local Republican headquarters. Commentators spun the Wilmington Insurrection as a “race riot,” which it was, but with the implication that Blacks initiated it when really it was a violent coup led by supremacists. In today’s culture wars, Florida’s GOP is requiring that teachers equivocate both sides’ violence in racial massacres — mentioning Ocoee, Tulsa & Rosewood in particular — unnecessarily rectifying the image of old school Democrats instead of cashing in on, what was then, their own party’s forward thinking. But party identities shift so much historically that they become meaningless within a few decades. Wilmington demonstrates how insurrections can occur, supposedly, within the system rather than declaring themselves as outright revolutionaries. Democrats forced Republicans to sign the requisite paperwork at gunpoint, keeping it all within the system. Journalist Adam Serwer wrote that Wilmington’s insurrectionists “believed themselves not usurpers of the established political order, but agents of its restoration because, as they put it, the Framers ‘did not anticipate the enfranchisement of an ignorant population of African origin’.”

Lost Cause

Southerners, then, also won the battle of historical interpretation, especially in the Southeast but, to a surprising extent, even the North. For nearly a century after the war, Democrats in many states made it illegal for public schools to teach that the South’s cause in the Civil War was connected to the “peculiar institution” of slavery. Southern socialites played an active role in re-writing history to erase slavery as the war’s cause, with the Confederate declarations of secession flushed down the memory hole. Georgian Mildred Lewis Rutherford (aka “Miss Millie”), pro-slavery historian general of the Daughters of the American Confederacy, argued in A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks (1919) that public schools should reject any text arguing that “the South fought to hold her slaves.” Instead, the civic religion of The Lost Cause obscured slavery’s importance, emphasizing states’ rights, duty, and honor, as represented by the ambiguously pro-slavery Robert E. Lee. Lee had brine rubbed into the wounds of his enslaved people after they were whipped and once called enslavement “necessary for their instruction as a race;” but he called slavery a “political and moral evil” in 1856 and planned to manumit his enslaved staff five years after his death if his Arlington estate was financially sound. Historian Gary Gallagher said, “you could even pretend that Lee was sort of anti-slavery if you squint just right and stand on your head and turn the lights out.” Frederick Douglass bemoaned how northern newspapers praised Lee’s character in his 1870 obituaries. It’s probably not coincidental that Lee’s Army’s “Stars & Bars” streamer became the lasting symbol of the Confederacy rather than either of the actual political Confederate flags. While there’s no evidence that Lee planned to end southern slavery if the Confederacy won, he opposed the erection of the Confederate monuments that later stirred controversy, including many of him, predicting that they would only “keep open the sores of war” — prophetic considering what happened in the 21st century.

The forenamed “Grey Ghost” Mosby (left) also opposed statues that attempted to erase or rewrite history by downplaying slavery, because that’s what he fought to protect. In a 1907 letter to Sam Chapman, Mosby wrote:

The forenamed “Grey Ghost” Mosby (left) also opposed statues that attempted to erase or rewrite history by downplaying slavery, because that’s what he fought to protect. In a 1907 letter to Sam Chapman, Mosby wrote:

“People must be judged by the standard of their own age. If it was right to own slaves as property it was right to fight for it. The South went to war on account of Slavery. South Carolina went to war ― as she said in her Secession proclamation ― because slavery [would] not be secure under Lincoln. South Carolina ought to know what was the cause for her seceding. […] I am not ashamed of having fought on the side of slavery. The truth is the modern Virginians departed from the teachings of the Fathers. John C. Calhoun’s last speech had a bitter attack on Mr. Jefferson for his amendment to the Ordinance of `87 prohibiting slavery in the Northwest Territory.” (Wiki)

Jim Crow-era Lost Cause proponents from the 1890s-1920s put up most of the statues in question to underscore their commitment to segregation and disenfranchising Blacks, avoiding honoring Confederate generals like James Longstreet that later supported black suffrage or worked with authorities against the Ku Klux Klan. Many military historians see Longstreet as the best corps commander on either side of the war, but he fought with Blacks against the White League in New Orleans’ Battle of Canal Street (1874) — an apostasy causing Lost Cause historians to blame him for the defeat at Gettysburg even though Lee overrode Longstreet’s sound advice to go around Cemetery Ridge, arguably blowing the Confederacy’s best post-1861 chance to win the war (previous chapter). Trump inverted the Lee-Longstreet story on the 2024 campaign trail to attract voters inclined toward Lee’s mythology (Newsweek > Jon Stewart). J.E.B. Stuart was another scapegoat for the Gettysburg loss that took the historical blame off Lee.

The movement kicked off with publication of The Lost Cause Regained (1868) by journalist Edward Pollard, that emphasized states rights and revised his 1866 book that stressed slavery’s nobility. The cause was lost to start with because they’d faced an enemy with overwhelming resources, even though their soldiers were superior. Actual Confederate veterans never disparaged Union soldiers, but their fans didn’t realize that slighting an opponent doesn’t burnish ones’ own reputation, win or lose. Moreover, though they’d lost the war, the South had fought for morally superior causes like states’ rights, while slavery, hereafter often referred to as “slavery, so-called,” was only incidental. In his follow-up book, Pollard called on Southerners to honor Confederate heritage by always resisting national power, setting up the cataclysmic civil rights struggles of the 1960s.

The states’ rights interpretation rang especially true during Reconstruction when there really was tension between the national government and the Union-occupied southern states. Julius Howell, a 101-year-old Confederate veteran interviewed in 1947, said they fought for states’ rights because the national government imposed its will after the war. In effect, he was arguing that the South seceded in 1860 because of how they were treated after 1865, showing how time clouds the memories even of those who personally lived through something. But as we also saw in Chapter 19 on Secession, prior to the Civil War, Confederate leaders showed no consistent adherence to states’ rights except as a means to an end — a fallback position after their failed attempt to exert national power on slavery’s behalf. Before the war, Southerners opposed new states deciding whether to legalize slavery on their own out west, and Confederate states lacked the power to legislate slavery within the Confederacy. The very people spinning the Lost Cause interpretation after 1865 clarified that they were fighting to preserve slavery in 1860-61, before it was known as “slavery, so-called.” At some point, either before or after the Civil War, their interpretative wires got crossed. I’m guessing after.

Scholars at Vanderbilt University called the Agrarians updated and refined the Lost Cause theory in the 1930s, arguing that an acquisitive, overbearing, industrializing North essentially attacked the bucolic South in a war of railroads and factories versus traditional farms. Their interpretation coincided with the popularity of the book and movie Gone With the Wind. But the original ringleader of Lost Cause revisionism was Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who penned a 1,500-page tome entitled The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1881) and spoke across the South throughout retirement. Davis argued that slavery was the occasion for the war but not the cause, and that the U.S. and Confederacy preceded from similar ethical and political frameworks — the latter theory one that modern historians increasingly entertain even if the former is nonsensical. He made the best arguments on behalf of secession that he could, pointing out Lincoln’s hypocrisy in denying the constitutionality of the Mexican War and Lincoln’s view that Mexico had the right to the same self-rule that Davis argued the Confederacy should have had. Of course, Mexico wasn’t in the United States and the reverse argument could be used on Davis insofar as he didn’t respect Mexican sovereignty or right to self-rule in the 1840s, but that’s another matter. More importantly, most of the arguments Davis made on behalf of states’ rights as an alternative cause concerned the right of states to have slavery, lending credence to the argument he was trying to debunk. A teacher trying to make a case for slavery as foundational to the war could start by just assigning Jeff Davis’ own book about how it wasn’t.

Nonetheless, all of us contribute taxes to museums and historical sites like Alabama’s Confederate Memorial Park that perpetuate the Lost Cause interpretation. After Hurricane Katrina destroyed Davis’ Presidential Library and beach home Beauvoir in Biloxi, Mississippi in 2005, U.S. taxpayers spent millions to restore the new library, operated by the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV). The cemetery features an engraving from English poet Philip Stanhope Worsley dedicated to Robert E. Lee: “No nation rose so white and fair, none fell so pure of crime.” The bookshop sells books on southern heroism and northern treachery and runs a machine that flattens pennies, replacing Abe Lincoln with Davis’ profile. The SCV is a peaceful group that disavows any association with the KKK and condemns violence. Yet, it sells books with favorable reinterpretations of Confederate general and Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose popularity spiked with the election of Barack Obama, stressing parts of his biography other than when he murdered black POWs in the Ft. Pillow Massacre. With members in all fifty states, Europe, Australia, and South America, the SCV has counted among its own Harry Truman, Clint Eastwood, Paul “Bear” Bryant, Hank Williams, Jr., and Pat Buchanan. Their main purposes are charity, assisting genealogical research, and heritage defense. For some white Southerners, heritage connects innocuously to regional or ancestral pride, perhaps peppered with a dash of Lynyrd Skynyrd or Dukes of Hazzard reruns. The SCV defines heritage defense as educating the public that the Confederate cause didn’t concern slavery and that the Confederate battle flag doesn’t symbolize racism — a tougher sell after the Klan and other hate groups adopted Lee’s battle flag in the 20th century. The SCV site is worth checking out for those interested in Neo-Confederates and the general topic of historical revisionism. (Revisionism is often misunderstood by the public as a bad thing, but all interpretations are subject to revision from all camps. To argue otherwise is to over-estimate the dependability of early drafts and under-estimate the subjectivity of all interpretations. The Lost Cause argument itself is a classic and influential, if poorly argued, example of revisionism.)

In 2012, the front page of the SCV site included a reenactor warning of “people in your town who will try to tell you lies about what caused the Civil War,” meaning those who argue that its root cause was slavery. That’s me I guess, but I’m open to changing my mind, so I popped the hood on their Research > History drop-down to hear them out. Their history section highlighted Lyon Gardner Taylor’s Confederate Catechism (3rd ed. 1929), an iconic primary source for the Lost Cause. The Catechism traces resentment between the regions back to the Jay Treaty of 1785, the Jefferson-Burr election of 1800, and the South Carolina Nullification Crisis of 1832-33. It conveniently skips over the Sectional Crisis of 1846-60 before getting to the deal-breaking Lincoln election in 1860, which it accurately depicts as posing a direct challenge to Dred Scott (1857). Lincoln’s platform “repudiated the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court authorizing Southerners to carry their slaves into the territories.” It’s the same argument Lincoln and Douglas debated in 1858 and that motivated southern Democrats to seek a national law enforcing Dred Scott in their 1860 platform. Then again, if the idea was to either dismiss slavery as being connected to the war or emphasize states’ rights, it would be best to avoid spotlighting the Dred Scott case since it denied territorial sovereignty. As a catechism, the pamphlet asks a series of anticipated questions and provides the convert with rebuttals to memorize. Heading #2 asks the all-important question, was slavery the cause of secession or the war? This is the drum-roll moment and perfect opportunity to explain to skeptical outsiders — liars in your hometown if you will — how slavery didn’t cause secession. The explanation is that it was, instead, the “vindictive, intemperate” anti-slavery movement that was at the bottom of all the troubles.” So the Civil War wasn’t caused by slavery, but rather opposition to slavery. Here’s a better and shorter catechism for citizens interested in confronting our country’s true heritage: when we spill a lot of ink explaining how something isn’t about race, is it really? Yes.

Reconstruction Fizzles

In the late 19th century, the U.S. government acquiesced in and adapted to Redeemer Rule in the South. President Grant phased out Radical Reconstruction and Union forces retreated in 1877. Faced with an economic recession that cut jobs for factory and railroad workers and fearing the migration of Freedmen, northern Democrats crushed pro-Reconstruction Republicans in the 1874 mid-term elections, taking over the House of Representatives. In the 1876 presidential election, New York Democrat Samuel Tilden seemingly won a close election over ex-Union general and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Tilden won the popular vote and led the electoral college 184-165 with 20 votes in four states contested. Republicans cried foul, claiming that the White League and Red Shirts were scaring their voters from the polls in the South. Democrats could scarcely deny the charge since vigilante “social clubs” were bragging about how many voters they’d murdered on election night, taking credit for the victory. If they’d killed even a handful, how many less courageous (or wiser) people avoided the polls altogether?

Northern Republicans, meanwhile, cheated worse, likely, than any party in any election in American history. The fact that Western Union was intercepting Democrats’ messages and relaying them to the Republicans doesn’t distinguish 1876 as worse then typical elections. But Republican-controlled returning boards stole votes through fraud and bribery and even enlisted the U.S. Army to steal ballots. In Louisiana, they threw out one in 10 votes statewide, most of them for Democrats.

The two parties held a behind-closed-doors meeting organized by a federal commission, off-limits to journalists (and future historians). The resulting Compromise of 1877 was clear enough, though: Hayes won the election and the Union Army retreated from what remained of its southern occupation, Louisiana and (fittingly) South Carolina. As for the fate of African-Americans, Hayes hoped for “wise, honest, and peaceful local, self-government,” in effect letting the foxes guard the henhouse and abandoning them to Jim Crow. In addition, Congress would help stimulate industrialization in the South and build a southern transcontinental railroad (the 5th overall) connecting Texas to California. It’s ironic given some of the economic debates of the 1850s that, as part of their agreement to leave the South after the war, the North gave into southern demand for, rather than refusal of, subsidies from the national government to aid industrialization. After all, opposition to such measures was part of what fueled the southern Democrats for decades, dating all the way back to Jefferson. According to some, it was even the very cause of the Civil War. In that way, Americans after the Civil War were similar to many today that want the government to stay out of their business as they demand protection, better roads, aid, emergency relief, and subsidies. The sign of one protester around 2010 read “Government: Keep Your Hands Off My Medicare!”

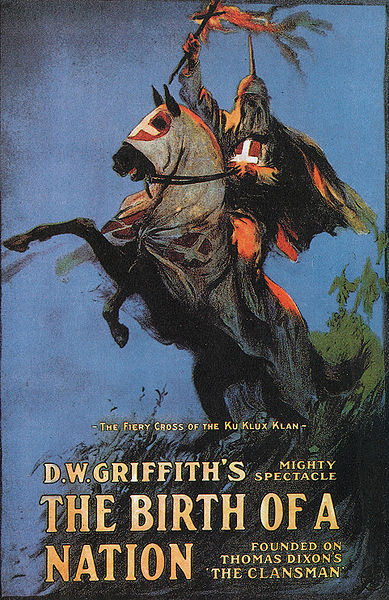

Reconstruction as a formal period in American history was over, even if we’re still shaking out its full implications. Slowly, the regional wounds began to heal. Northerners began touring the beautiful old plantations and many shared in the idealization of the antebellum (pre-war) South as a fully functioning society where everyone knew their place. Union and Confederate soldiers socialized at reunions, with many saying they connected more to the opposition than those back home who hadn’t fought. The best documented of these get-togethers was the 50th Anniversary Gettysburg Reunion in 1913 that we saw in the previous chapter. It didn’t always bode well for Blacks, though, when Whites talked about “healing wounds,” as racism was often the tie that bound. In the “happy ending” of our nation’s first feature-length film, Birth of a Nation (1915), after the white families split by war have reconciled through marriage and the Klan has brought Blacks to heel, the title card reads: “The former enemies of North and South are united again in common defense of their Aryan birthright.”

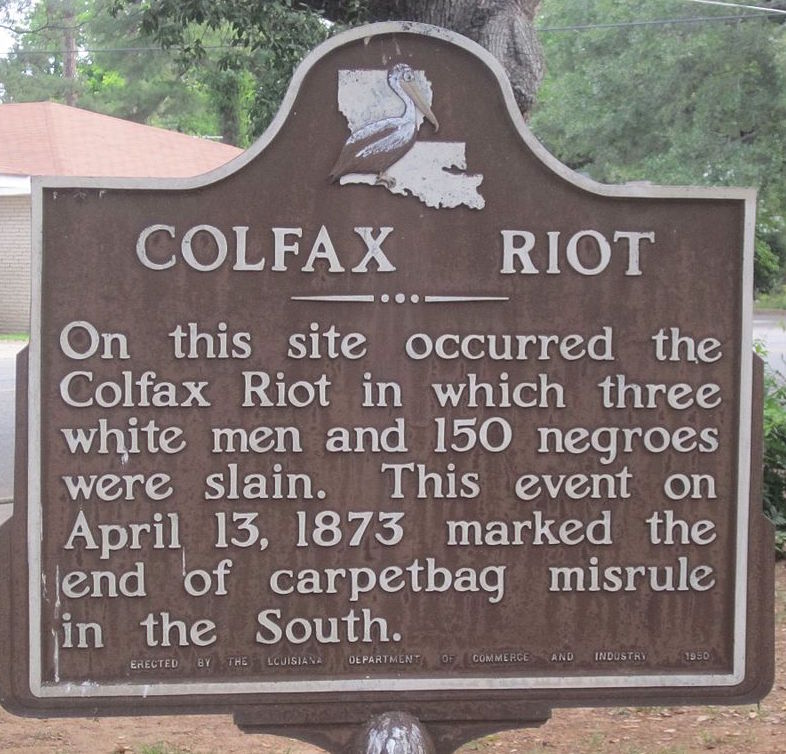

The Supreme Court did its part by watering down the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. While the Fourteenth did ultimately apply the Bill of Rights against states, that wasn’t the case at first. In U.S. v. Cruikshank (1876), concerning violence in Louisiana between white vigilante groups and black Republicans, the Court ruled that civil rights were purely a state matter and that the national government couldn’t intervene. That was eight years after the Fourteenth Amendment’s passage and, as mentioned above, one of its framers’ purposes was to guarantee Second Amendment rights to Freedmen. The Cruickshank case opened the doors for white vigilantes to mete out violence at will against Blacks in the Jim Crow era, as they had in the Colfax Massacre after a disputed gubernatorial election between Democrats and Republicans in 1872. In the worst racial violence of Reconstruction, Whites killed 150 black Republicans and militia at Louisiana’s Colfax County Courthouse (now Grant Parish) on Easter Sunday 1873 and escaped prosecution, leaving Democrats in control of the state. Twentieth-century Whites celebrated the event with this 1950 historical marker:

In the late 19th century, the Court took on a cluster of Civil Rights Cases (1883) that all asked the same fundamental question about the Fourteenth: did people who lived in states, including businesses and political parties, have the right to discriminate or violate their fellow citizens’ rights, even though state governments didn’t? The answer was yes until the Court revisited the question again in the Heart of Atlanta Motel case in 1964, a century after the Civil War. Williams v. Mississippi (1898) approved poll taxes and literacy tests while United States v. Harris (1882) ruled that the federal government didn’t have jurisdiction over murder cases, meaning that Whites could lynch or burn Blacks as long as their state governments didn’t stand in the way. Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) likewise confirmed that segregation didn’t violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as long as facilities were purportedly equal (in that case, passenger trains; in later cases, schools).

Twentieth-century Civil Rights leaders dusted off and reinvigorated the Civil War Amendments, vindicating the hopes of Charles Sumner — he on the receiving end of Preston “Bully” Brooks’ cane during the Bleeding Kansas controversy (Chapter 18) — who called the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth “sleeping giants.” Unlike South Africa after Apartheid, the U.S. didn’t junk its constitution and start over to make racial progress, but rather strengthened its existing constitution. This is the Second Founding that Dr. Foner described above. But the enhanced interpretations of the Civil War/Reconstruction amendments were still on the distant horizon as of the 1870s. In the meantime, Foner wrote that Blacks faced a “wave of counter-revolutionary terror…that lacks a counterpart either in the American experience or in that of the other Western Hemisphere societies that abolished slavery in the nineteenth century.” Texas courts “indicted some 500 white men for the murder of blacks in 1865 and 1866, but not one was convicted.” During Reconstruction, the Supreme Court let state governments gut the Fourteenth and Fifteenth as best they could. Alabama rewrote its constitution in 1901 to “establish white supremacy,” reducing the number of eligible black voters from 181k to 3k. At 40x the length of the U.S. Constitution, it is the longest still-operative constitution in the world, though the racist elements were overruled by subsequent Supreme Court cases in the 1960s.

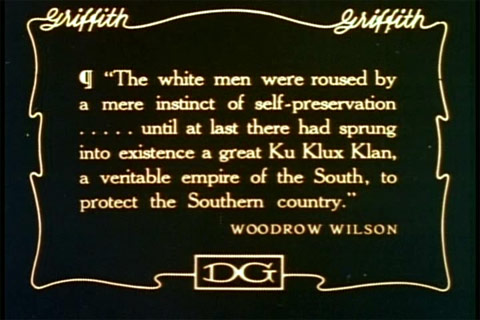

In 1915, the forenamed Birth of a Nation idealized the Klan as protagonists who restored honor and saved the region from evil-doing Yankee carpetbaggers and bands of raping Blacks, portrayed by white actors in blackface. Black politicians who served during early Reconstruction are depicted as cartoonishly incompetent, which was key to arguments against allowing African Americans to vote prior to 1965. President Woodrow Wilson, a Virginian, screened the film in the basement of the White House and the former history professor essentially concurred with its interpretation, though the quote itself might be torn out of context as he didn’t support the KKK. According to the common line of argumentation, Reconstruction had failed. Why? Because Whites had been too nice to Blacks and given them too much power before they were ready. What’s surprising is how widespread that consensus was. It wasn’t just how things were viewed in the former Confederacy. That was the mainstream interpretation taught in textbooks across the country, including northern politician Claude Bowers’ The Tragic Era (1929) and those of Ivy League professors like Columbia’s Charles Dunning, of the Dunning School of Reconstruction. There’s a saying that winners write the history but, with America’s Civil War, the losers wrote the history and the winners went along with it as the two bonded over racism. Frederick Douglass had seen this coming, wondering out loud, “In what position will this stupendous reconciliation leave the colored people?”

Reconstruction is a classic example of how differently the same history can be viewed through the lens of different times. All of us view history through the prism of the present. For many Americans today, it seems preposterous to blame Reconstruction’s failings on Blacks, even if they’re reading the same information as those that made Birth of a Nation or wrote The Tragic Era. For most modern historians, Reconstruction policy didn’t fail so much because of its own flaws as it was overthrown by vigilante, domestic terrorists who subverted democracy through violence.

The image below of the Statue of Liberty’s arm is a metaphor for Reconstruction. The French gave the iconic statue to the U.S. to celebrate the Union’s victory in the Civil War, with broken shackles around its ankles representing emancipation, sent overseas in parts to be assembled later, facing east to inspire European democracy. Gustave Eiffel, of namesake Paris tower fame, built the steel skeleton for Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s design, with the ground-level head doubling as advertisement for his firm. But in this 1877 photo, the statue, like Radical Reconstruction’s aim of citizenship for Freedmen, is incomplete. Before “Lady Liberty” (officially Liberty Enlightening the World) was assembled in New York Harbor, the Times wrote, “They have not been able to procure a whole statue, but they have ornamented the city with a nice large piece of the intended statue’s arm.” Likewise, Reconstruction only started an ongoing and uneven process toward racial justice. But, today, few Americans of any political persuasion would condemn Reconstruction for granting Blacks too many “special rights” or granting them “too soon.” In free societies, history is an ongoing argument.

Post-1877

You could think of Reconstruction as a contest over the status of formerly enslaved people. On one end of the spectrum was full equality and citizenship promoted by Radical Republicans and embodied in the amendments, 13-15. On the other end is an attempt to return Freedmen to a status as close to slavery as possible without technically being slavery. Reconstruction was fought out in the gray area in between and neither side won outright. African Americans made progress but only at the cost of violent backlash. Blacks ended up not as enslaved workers but as second-class citizens who worked mainly as sharecroppers or servants and, for the most part, after Radical Reconstruction (1865-67), couldn’t vote or hold office. Those that resisted ended up in chain gangs, burned, or swinging from a rope. One lasting effect of this domestic terrorism and institutionalized brutality is the Department of Justice, set up in 1870 under the executive branch’s attorney general to reign in white vigilante groups before the North gave up.

Convict Laborers Working On Granite Columns For Texas State Capitol, ca. 1885, AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, AUSTIN PUBLIC LIBRARY

With the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition on slavery exempting the penal system, affirmed in Ruffin v. Virginia (1871), prison chain gangs built much of the South’s infrastructure that taxpayers wouldn’t otherwise finance in a system similar to 20th-century Soviet gulags. Like many states, Texas leased its convicts and even operation of its prison in Huntsville to private firms prior to 1915. Convict Lease historian Theresa Jach detailed how A.J. Ward & Dewey ran Huntsville with its 20% white population working a textile mill while the 80% of Blacks worked adjacent cotton fields. Persistent sex scandals between staff and female prisoners finally forced the state to cancel its contract. They then leased to Cunningham & Ellis, who used prisoners to grow cane for Imperial Sugar. The Texas State Capitol in Austin was quarried by such workers in the mid-1880s, with limestone from near Oak Hill at “Convict Hill” and exterior Red Granite from Marble Falls. The prisoners worked on the Capitol with the Granite Cutters Union. Some of the prisoners were real criminals, but many weren’t or were subjected to unreasonable sentences.

The worst of these southern gulags was the Parchman Farm State Penitentiary in Mississippi. Historian David Oshinsky called Parchman the “closest thing to slavery that survived the Civil War.” There, state governor James Vardaman, aka “the great white chief,” sometimes had a prisoner released so that he and his dogs could hunt him down in the surrounding woods for sport. Vardaman said that “if it is necessary every Negro in the state will be lynched; it will be done to maintain white supremacy.” Later in his career, after educator and civil rights activist Booker T. Washington dined with President Teddy Roosevelt, Vardaman said the White House was “so saturated with the odor of the [N-word] that rats have taken refuge in the stable.” More recently, former L.A. Clippers owner Donald Sterling said something similar explaining why he didn’t allow black tenants in one of his Hollywood apartment complexes. Despite Washington’s education, Vardaman thought he had no more right to vote than the “coconut-headed chocolate-colored typical little coon who [shines] my boots every morning.”

To this day, most states in the Deep South don’t pay prisoners for labor and those that refuse to work get stuck in solitary confinement. Elsewhere, prisoners average around 60¢/hour in wages. One Louisiana politician even argued that the state should hold minor criminals to longer sentences because its prisons clear so much profit farming out cheap labor.

Many of the historical problems with unfair incarceration stemmed from the all-white jury system. Today we’re inclined to think of jury duty as a nuisance or obligation, but when groups don’t have the right to sit on juries it means that other races can run roughshod over them, precluding any hope of real justice. Minorities didn’t have the right to sit on juries in much of the U.S. until Hernandez v. Texas (1954). If it seems odd that America hasn’t solved all its racial problems yet, consider that slavery existed in North America for 250 years and the Civil War ended it only 150 years ago.

As of 2011, nearly 40% of Americans understood that the Civil War was caused by slavery, with 60% of those under 30 thinking it was caused by states’ rights (PEW). Hopefully, the 21st century will see increasing numbers of Americans able to confront the country’s history head on, but historiography will always be an argument enmeshed in culture wars. Those of you taking History 1302 later on will learn of Second Reconstruction in the modern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s, when Congress established more inclusive immigration policy and courts fleshed out the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to ensure greater racial equality, this time with Democrats leading the charge. Toward the end of the optional article below, UT historian Peniel E. Joseph argues that we’re now entering a more broadly-defined phase of Third Reconstruction as we aim to fulfill the original Reconstructionists’ dream of an equitable, multi-racial democracy.

Optional Further Reading & Viewing:

Jefferson Davis Papers (Rice Univ.)

Reconstruction: The Second Civil War (NEH)

Virtual Exhibit: People & Politics After the Civil War (Digital History)

Jourdan Anderson’s 1865 Letter To His Old Master (Letters of Note)

Eric Foner, “Why Reconstruction Matters” (New York Times 3.28.15)

Eric Foner, “Confederate Statues And ‘Our’ History” (New York Times, 8.20.17)

Eric Foner, “Broken Promises of Reconstruction Relevant to Today’s Racial Justice Movement” (The Hill, 8.24.10)

Eric Foner, “A Traitor to the Traitors: The Confederate General James Longstreet Became a Champion of Reconstruction. Why?” (Atlantic, 12.23)

James Sidbury, “Making History: Houston’s ‘Spirit of the Confederacy'” (Not Even Past, 2020)

M. Hardy, “Blood & Sugar: A Former Prison Guard’s Quixotic Campaign To Make A Houston Suburb Confront Its History” (Texas Monthly, 1.17)

“Voter Fraud, Suppression, and Partisanship: A Look At the 1876 Election” (HNN-CBS, 10.25.20)

(N.O. Mayor) Mitch Landrieu, “On the Removal of Four Confederate Monuments In New Orleans”

Ex-Texas Governor Rick Perry’s Speech On Jesse Washington @ National Press Club (2015)

Brenda Wineapple, “The First President To Be Impeached” (American Scholar, 3.4.19)

Peter Baker, “You Think This Is Chaos? The Election of 1876 Was Worse” (New York Times, 1.5.21)

Louis Masur, “How the South Rose Again” (American Scholar, 3.4.19) REVIEWS GATES’ STONY THE ROAD

Adam Serwer, “The Myth of the Kindly General Lee,” (Atlantic, 6.20)

Douglas Egerton, “Terrorized African Americans Found Their Champion In Civil War Hero Robert Smalls” (Smithsonian, 9.18)

Pema Levy, “Another Monument To White Supremacy That Should Come Down? The Electoral College” (Mother Jones, 7.15.20)

Adam Serwer, “The New Reconstruction” (Atlantic, 10.20)

Kate Groetzenger, “Civil Rights Advocates Push to Confront Texas’ Dark History of Convict Leasing” (Texas Observer, 3.26.19)

Frank Hyman, “The Confederacy Was a Con Job On Whites, And Still is” (McClatchy, 3.6.17)

Peniel E. Joseph, “The Revolution Never Ended: How Black Americans Kept Reconstruction Alive” (Atlantic, 12.23)

Justin Zeitz, “Why Was It So Hard For Nikki Haley To Say ‘Slavery?’: History Has The Answer” (Politico, 12.23)