“The American Revolution as it actually unfolded was so troubling and strange that once the struggle was over, a generation did its best to remove all traces of the truth.” — Historian Nathaniel Philbrick Referring to Benedict Arnold’s Contradictory Role

War between Great Britain and its American colonies began over a year before Continental Congress declared independence in 1776, with many soldiers fighting initially against British policy but not for independence. Soldiers that didn’t favor independence still opposed British policies on taxes, western expansion, religious freedom, slavery/abolition, and smuggling — in varying combinations depending on circumstance and region. By the end of 1775, King George III had blockaded the eastern seaboard but Rebels had British Redcoats surrounded in Boston. Colonial militia led by Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys captured Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York along with its ammunition and cannons. As Allen’s boys celebrated with His Majesty’s liquor, Arnold and his men sailed and rowed across Lake Champlain to St. John, seized British vessels and took control of the strategically important lake. In a herculean effort, Colonel Henry Knox’s Massachusetts and Connecticut militia laboriously hauled sixty tons worth of Ticonderoga cannons, mortars, and howitzers by horse, ox-drawn sledges, and human muscle across the forests, swamps, and rivers of the Berkshire Mountains in the dead of winter, surrounding the Redcoats in the Siege of Boston. Redcoats ransacked mostly empty Boston but eventually fled for Nova Scotia, agreeing to not burn the city in exchange for not being blasted to kingdom come as they sailed from Boston Harbor. If you have an extra 20 minutes or need geographic orientation, view this video (18:44) for an animated map and explanation of the entire war.

George Washington, head of the motley group of farmers and craftsmen known as the Continental Army, guessed right that when the Redcoats came back they’d return to New York rather than Boston. It was more important economically and had a sizable Loyalist population. There were plenty of Rebels there, too, but the size of the British fleet made many of them rethink their position. The British had a small occupying force in the colonies in 1775 but came back with a major army in ’76. Congress declared independence in Philadelphia just as the British sailed into New York and citizens and militia had to decide quickly whom to side with as they heard the public pronouncements. On July 9th, next to the site of the old Dutch fort in New Amsterdam and near today’s Charging Bull on Wall Street, some brave New York Sons of Liberty tore down King George’s statue in Bowling Green to melt it for cannonballs.

Sons of Liberty Pulling Down Statue of King George III, NYC, July 9, 1776, Johannes Adam Simon Oertel (1859). The Anachronistic Painting Includes 1850s Garb On The Statue and American Indians.

New York: A Sobering Start

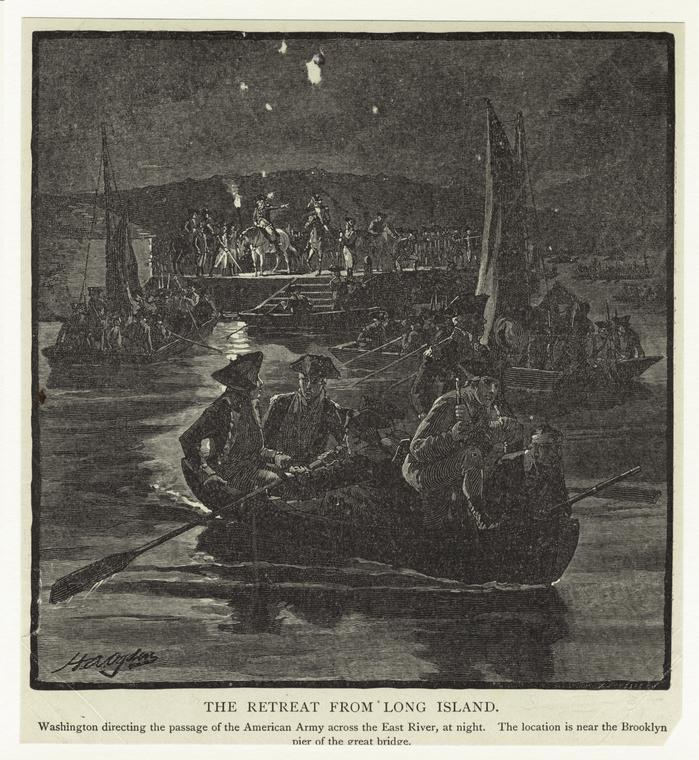

Washington marched his men south from Boston and moved them into position across the East River from Manhattan to Brooklyn Heights, within sight of the Redcoats across the harbor on Staten Island. The British offered Washington a pardon if he’d give up, but he refused. In August 1776, British routed Washington’s green troops, taking the western part of Long Island in the largest battle of the war, the Battle of Brooklyn Heights. The British had the Continentals trapped in Brooklyn but Washington’s men slipped away in the fog, safely across the East River to Kip’s Bay, Manhattan — then known as New York Island, or York City. (Historian David McCullough called the escape in the fog “America’s Dunkirk,” referring to the British evacuation from Nazi-occupied northern France in 1940.) The Brits also failed to pin down the Rebels in Manhattan in September. Washington’s men dug in their heels and won their first battle at Harlem Heights, but lost twice more at White Plains and Fort Washington in northern Manhattan. They gave up and retreated to New Jersey and Pennsylvania that November, leaving Redcoats in control of New York and parts of eastern New Jersey. To mock them, British buglers played traditional fox hunting songs as the Continentals ran away.

Lord Stirling Leading an Attack Against the British at the Battle of Long Island, 1776, Alonzo Chappel, 1858

It wasn’t a great start and some congressmen like John Adams criticized the retreat, but Washington’s men lived to fight another day as the saying goes. The important thing was keeping the army intact and they spent the winter of 1776-77 at Morristown, New Jersey. In May, they moved to the well-entrenched Middlebrook Encampment, positioned near a ridge on First Watchung Mountain from which they could view Redcoats in New York City to the east through a spyglass (monocular) and to the south at New Brunswick, N.J. Washington himself may have been lucky to escape capture that year. Some of his soldiers planned to defect to the British as soon as they invaded New York and rumors spread that they also planned to capture or kill Washington. A man convicted of passing counterfeit Continental bills heard about the plot in prison and relayed it to Washington. They hung the lead conspirator, Thomas Hickey, in front of 20k spectators.

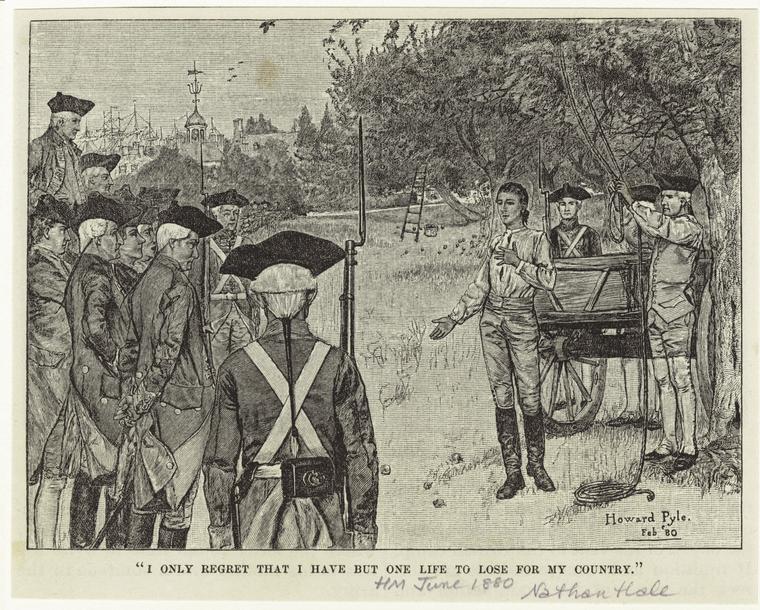

The British captured one Continental spy behind the lines in Manhattan, Nathan Hale, who purportedly said, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country” before the scaffold dropped from under him. The story was apocryphal, but the resistance needed any inspirational stories they could muster. In the 1980s, CIA director William Casey wasn’t so impressed; he wanted Hale’s statue taken down at their Arlington headquarters because he was caught.

After the New York rout, the independence movement seemed on the verge of collapse. That Fall, Redcoats chased Patriots out of Newport, Rhode Island. For the next three years, they held that most important port in New England for slavery, rum, and American piracy. Common Sense author Thomas Paine wrote, “These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country.” Sure enough, they did. Within the space of a few weeks, Washington’s army had shrunk from around 15k regulars to 3-5k. Your author’s own ancestor was a sunshine patriot: clockmaker Effingham Embree deserted Washington when the British promised he could keep his Manhattan shop open if he signed a loyalty oath. Embree’s case was common, as demonstrated by historian Jane Kamensky. While it’s easy to project onto history simple stories of good vs. bad and people “choosing sides,” Kamensky believes that Americans’ sides were often chosen for them by work, marriage, friends, family, money or survival. Many changed sides often, to the chagrin of Thomas Paine, “with the circumstances of every day.”

Washington hadn’t lost that many men to casualties in New York, but he might as well have in terms of the size of his army. He learned early on that his men, while brave in their own way, didn’t like taking orders. They were there for their own reasons and didn’t respond well to authority. If they had, they probably wouldn’t have been rebelling in the first place. Despite this lack of conviction among some, Patriot leaders refused to back down. A three-hour peace conference on Staten Island on 9/11 (1776) was a non-starter. The Howe brothers who led the New York campaign for the British, General William and Admiral Lord Richard, were predisposed toward Americans (some historians have theorized that’s why they allowed Washington to escape twice in the campaign), but their authority was limited to offering pardons and they demanded that the representatives rescind the Declaration of Independence to open negotiations. That wasn’t going to happen when the very people they were talking to, including Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, were from Continental Congress. Congress had already made up its mind and wasn’t turning back.

The independence ship had already set sail regardless of how badly Washington was outnumbered. The British had far more troops: 80k (including 30k Hessian mercenaries) compared to Washington’s 3-20k, depending on the circumstances. The Hessians weren’t really professional soldiers so much as poor farmers sold to the Crown to pay off a debt. Eventually, another 20k black slaves joined His Majesty’s Troops, who promised freedom to loyal slaves. Thirty-thousand Americans had encircled Boston in 1775, the high point of rebel enthusiasm and Washington brought about 20k with him to New York, but lost most of them after the retreat.

The New York campaign symbolized strategic factors. The British occupation of New York was part of their broader plan to conquer port enclaves to snuff out America’s vulnerable import/export economy — similar to what they’d done in Ireland and a continuation of what they’d already been doing with the Prohibitory Act of 1775. They also occupied Philadelphia, forcing Continental Congress to retreat into the woods to meet wherever they could. Washington’s retreat was part of what evolved into his defensive, or Fabian, strategy of avoiding direct conflict with the larger, professionally trained Redcoats, fighting them when and where he chose in quick hit-and-run campaigns. The Continental Army could not afford a war of attrition in which both sides sustained big casualties. They were also under constant threat from smallpox epidemics and had to divide precious time between drilling and building fortifications.

What was called guerilla warfare by the 19th century wasn’t what the traditional and aristocratic Washington preferred but he had little choice since the war was largely about avoiding taxes and Continental Congress struggled to fund his army. Wouldn’t colonials willingly pay taxes if they had representation? As it turns out, it was actually the taxes part of no taxation without representation that was the kicker. The main pay Congress or states could offer soldiers was land. Pennsylvania, for instance, offered 200-1000 acre lots called depreciation lands in the western part of the state along the Ohio River. Or, they could offer Continental dollars or bonds from the fragile new government — the same one that was meeting in the woods because they’d been chased from Philadelphia. These early U.S. securities later caused a firestorm because soldiers weren’t sure if the notes would be redeemable and many sold them at cut rates to speculators knowledgeable that a national government would form and make good on earlier debt; in fact, as we’ll see in Chapter 11, that very firestorm led to the country’s first two-party system. States also kicked in some local taxes. Whatever the source or form, pay was contingent on victory and promises of future land didn’t help soldiers feed their families or pay for mortgages in the meantime if they left their farms or shops to fight. It’s no wonder many came and went, not so much to desert as to keep things solvent on the home front. Militias supplemented Washington’s regulars and were less reliable, yet proved indispensable and contributed to several major battles. Thomas Paine, bless his heart, donated all his royalties from Common Sense to the Continental Army but that didn’t make much of a dent.

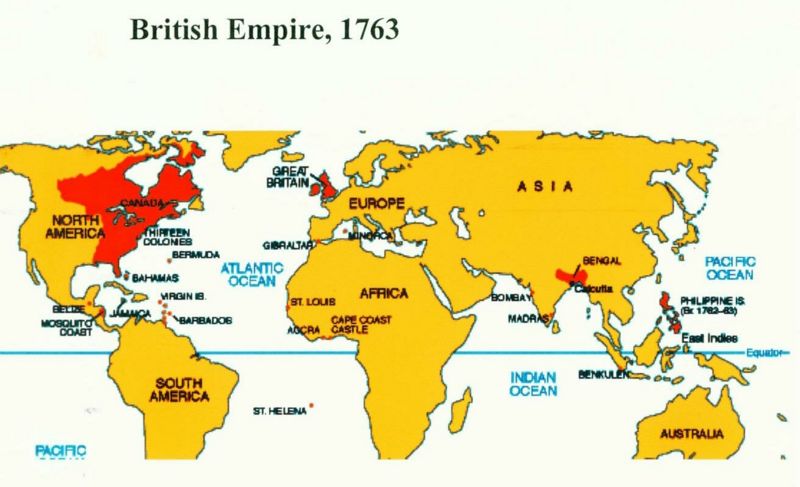

The Rebels had some important advantages, too, though. As insurgents fighting in their own land, they didn’t have to defeat the British so much as they had to hang on until the British gave up. The British, in turn, had to win what John Adams called the “hearts and minds” of the American people, a phrase re-popularized in the 1960s during the Vietnam War when the U.S. was trying to win over the South Vietnamese population. As Carl von Clausewitz argued in On War (1816-1830), wars are both military and political. In this case, the British had to convince America’s non-Indian population of 2.5 million (~ 20% enslaved) that their best bet was staying in the Empire. General Howe couldn’t simply chase down Washington’s men and massacre them. If he had, the military part of the war would have come to an abrupt end but he would have alienated the local population in the meantime. As mentioned in the U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual (2006), excessive power can undermine political legitimacy. That’s not the case in a knock-down drag-out conflict like WWII but it’s true when one power is trying to win over a civilian population as they fight in that population’s land. The Redcoats needed to politely pummel Washington’s men into submission in a gentlemanly way that would win the respect of the public at large, while maybe intimidating them just enough to pay taxes. Complicating this tightrope act, the British had more on their plate than eastern North America. In 1776, they had other colonies in the Americas beyond the thirteen in question along with some in Asia and were struggling to control their next-door neighbor, Ireland. Being a world empire keeps you busy.

Hearts & Minds

With only around 1/3rd of Americans supporting independence (40% max), the Rebels had their own propaganda battles to fight, including getting people to think of the struggle as an actual war for independence rather than a civil rebellion, as the British and Loyalists interpreted it. I’ll use the terms Rebels or Continentals below to describe the forces fighting for independence but, depending on their location, they were also known as Patriots, colonials, Yankees or Whigs (for their political affiliation). Many Americans at the time thought of it as a civil war, but the Rebels cleverly appropriated the name Patriots, a key reversal that glossed over the fact they were committing treason against their country and projected confidence in the prospects of a new nation. The term had a slightly different meaning in the 18th century, anyway, and was considered pejorative by some Englishmen. To draw an imperfect but instructive analogy, consider what Americans’ opinions would be today if Alaskans or Hawaiians wanted to secede from the U.S. Some might be angry while others might sympathize, but virtually no one would describe the insurgents as patriotic. Still, if the Rebels were envisioning a future country and won, then it would make sense for their own history books to describe them as patriots or founders.

Conversely, textbooks today aren’t so kind to Civil War Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis. Since they lost, the victorious country (the U.S.) retains the term civil war rather than the Southern War for Independence, as Confederates called it. In any event, Patriot mobs of the 1770s got the upper hand against Loyalists (or Royals), who tended by nature to be more genteel, wealthier, and better behaved. In the North, Rebels put Loyalists on the defensive and some fled to Canada. In many areas, Rebels disarmed Loyalists and confiscated or burned their property. As for the other 1/3rd in between, they were the type that didn’t care for politics and wanted to be left alone. They claimed allegiance to whichever army was nearby and sold food to whichever army paid the most, usually the British. They figured, arguably with good reason in the near term, that their lives wouldn’t be significantly different regardless of the outcome.

Christmas Surprise

In these trying circumstances, Washington was compelled to cheat a little, at least according to the unwritten codes of 18th-century warfare that more or less prohibited fighting in the dark or in the winter. Realizing the Hessians would be preoccupied and intoxicated on Christmas, he snuck troops across the Delaware River and surrounded their camp at Trenton, New Jersey. He launched a successful attack in the dawn fog on December 26th, 1776 while posing for the most famous painting of the revolution, actually painted years later by a German during the democratic revolutions in mid-19th century Europe.

Washington set the trap by using a double agent to convince the British that his army was elsewhere at the time. The street-to-street fighting in Trenton resulted in hundreds of Hessian mercenaries being captured, some of whom took up Washington’s offer to leave their makeshift POW camp and become American citizens (including actor Rob Lowe’s 5x grandfather). German-Americans appealed to Hessians to defect and they sent the POWs out on work release as farmers, lumberjacks, and musicians. They offered some Hessians land, while others met women and defected to marry and settle in America.

After Trenton, British troops under Charles Cornwallis moved down from New York to avenge the “Christmas Surprise” but, again, as was the case in both Brooklyn and Manhattan, they had a hard time pinning down Washington. Cornwallis was another British general sympathetic, off the record, to the American cause. Cornwallis and his men found Washington and surrounded his army but decided to wait until morning to attack since the Continentals were, literally, stuck in the mud. But Washington could tell from sniffing the air that it would frost. He waited until the mercury dropped and snuck his men out in the middle of the night on frozen roads, passing near Cornwallis’ sentries. A few men stayed behind to stoke the fires, giving British scouts the impression they were still there. Cornwallis got his men up bright and early the next day but Washington’s army was nowhere to be seen. The early bird doesn’t get the worm if the rival bird stays up late the night before. Washington’s men were ten miles down the road whaling on Cornwallis’ second string at Princeton, New Jersey. Neither Trenton nor Princeton was a grand battle in the traditional sense, but they boosted morale for a struggling movement looking for any shred of good news and propagandists exaggerated them for good effect.

Saratoga

Rebels scored a more significant victory the following summer at Saratoga, New York, but Washington wasn’t there. Two of the heroic leaders, rather, were Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold, neither of whose reputations survived the war. Gates wrote up the reports for the battles and ignored Arnold completely because of a rivalry between the two, setting in motion years of frustration on Arnold’s part that culminated in his treason against the U.S. Arnold also shattered his thigh, complicating his service thereafter. A third important hero was Gates’ engineer, Polish immigrant Tadeusz Kościuszko, whose reputation did survive the war as we’ll see below. He later led a democratic Polish uprising snuffed out by Prussia and Russia.

From the British perspective, the Battles of Saratoga underscored the logistical disadvantages of foreign wars in the 18th century. They planned to isolate New England, that they saw as the main source of the rebellion, through a three-pronged attack on the Lake Champlain-Hudson River corridor, a mostly continuous water link connecting the St. Lawrence River to New York Harbor and the Atlantic Ocean. When American forces failed to conquer Quebec in 1775/76 (previous chapter), they retreated south into New York while the British pursued them, hoping to link up with Redcoats in New York City. But Arnold quickly built a small ragtag Navy out of re-purposed merchant ships, galleys, and gondolas called the “Driftwood Fleet,” importing rope, block and tackle, cannons, and anchors from colonies further south, along with shipbuilders from New York City. The British has disassembled their ocean fleet and rebuilt mostly smaller ships for Lake Champlain, but Arnold held them off at the Battle of Valcour Island in 1776, setting a trap in a passage off the island too small for Britain’s one frigate and barge and setting their smaller ships against the wind so they had to row to stay in position instead of manning their main gun batteries. Valcour Island was a draw, but it delayed the British and prevented them from moving south that year.

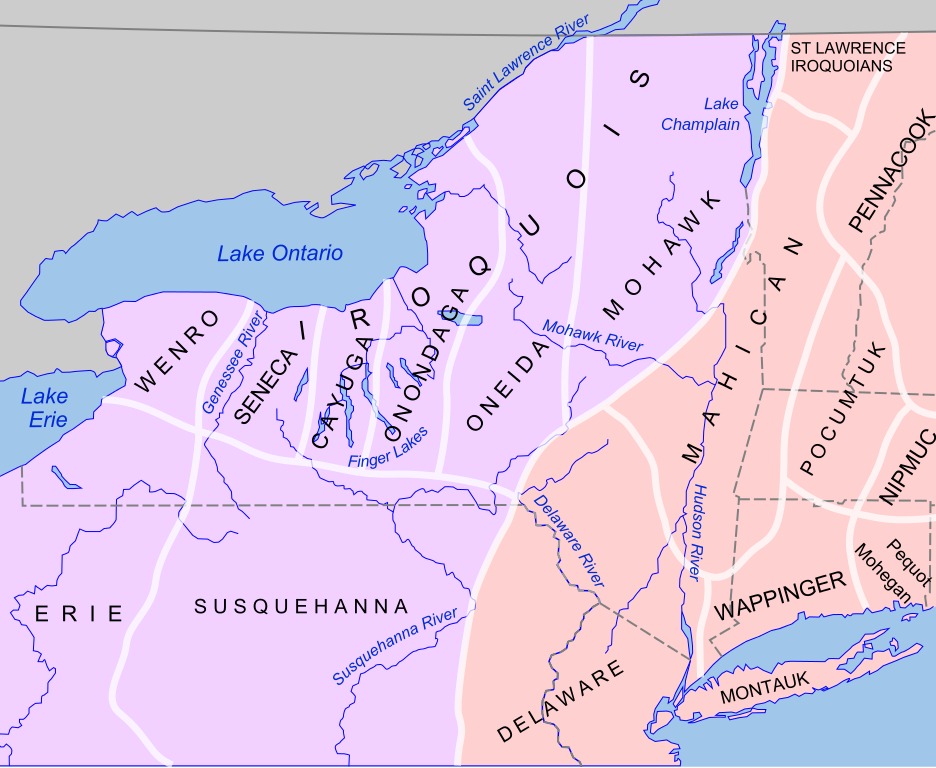

The next summer, 1777, one British column was supposed to approach from the west and Great Lakes, another would approach from the south coming up the Hudson River, while a third would come from the north down Lake Champlain. The three would rendezvous near Albany, New York, then march east and snuff out the rebellion where it started, in New England. Unfortunately for the army coming south, the other two armies never arrived. Barry St. Leger didn’t make it down the Mohawk River Valley after being turned back at the Siege of Ft. Stanwix by Arnold, and William Howe never made it up the Hudson River after invading Philadelphia, being under the impression that he was only obligated to go north if time permitted. That’s why Washington wasn’t there because he was trying (and failing) to keep Howe out of Philadelphia.

The next summer, 1777, one British column was supposed to approach from the west and Great Lakes, another would approach from the south coming up the Hudson River, while a third would come from the north down Lake Champlain. The three would rendezvous near Albany, New York, then march east and snuff out the rebellion where it started, in New England. Unfortunately for the army coming south, the other two armies never arrived. Barry St. Leger didn’t make it down the Mohawk River Valley after being turned back at the Siege of Ft. Stanwix by Arnold, and William Howe never made it up the Hudson River after invading Philadelphia, being under the impression that he was only obligated to go north if time permitted. That’s why Washington wasn’t there because he was trying (and failing) to keep Howe out of Philadelphia.

General Johnny Burgoyne’s third column floating down Champlain got off to a promising start, recapturing Fort Ticonderoga near the southern tip of the lake but ultimately found itself trapped alone between the lake and Hudson River. The wilderness between the lake and river was denser than they’d realized, making the distance between the two seem larger than it had looked on a map back in England, especially loaded down with 30 wagons. Wiser heads in England familiar with previous campaigns in the French & Indian War warned Burgoyne of that very fact, but they didn’t prevail. Had the British possessed some form of modern communication the debacle might have been avoided but, in the 18th century, their only hope for such an ambitious undertaking was to plan it months ahead of time then part ways and hope for the best. The plan also relied on support from Indian allies, who abandoned Burgoyne once they realized the other two armies weren’t going to show.

Complicating matters, “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne had come to America looking for a little R&R, with prostitutes and booze in tow, while the wife and kids held down the fort in London. To his credit, the arrogant playboy confidently placed bets on himself winning before he left town. His entourage cruised merrily down Lake Champlain but their supply line proved cumbersome and unwieldy as they tried to maneuver on land over to the Hudson. Nonetheless, the Brits continued to pursue the Continental Army as they fled south. Area farmers led by Kościuszko rushed in and surrounded Burgoyne’s troops, chopping down trees in his path to bog him down. Some were upset that Indians fighting with Burgoyne had slain the fiancé of a Loyalist, Jane McCrea, even though they were Rebels themselves, not Loyalists.

Tadeusz Kościuszko Wearing the Eagle of the Society of the Cincinnati, Awarded by General Washington, Portrait by Karl Gottlieb Schweikart

The style of fighting also took the British off guard. Traditional codes of honor dictated that soldiers not shoot officers marked by ribbons on their uniforms, but the practical farmers were happy to have the most important men specially marked and shot them first. They fired new guns that, unlike traditional smooth-bored muskets, had rifled (or spiraled, grooved) barrels, allowing greater distance and accuracy for their cylindrically-shaped bullets. Morgan’s Riflemen led by Daniel Morgan made good use of the improved weapon and was one of several militias that, collectively, might have contributed as much to Rebel victory as Washington’s Continental Army. Other important militia battles included Cowpens and Kings Mountain in South Carolina in 1780, and there was an all African- and Native American militia in the North, the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, that served for eight years, 1775-1783.

After a series of battles spread over a month, including Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights, Burgoyne gave up on St. Leger and Howe and raised the white flag. Kościuszko selected the high ground at Bemis Heights that made the difference. Burgoyne surrendered his entire army, nearly 6k men, in a stupendous victory for the struggling Continental Army, losing his bet back home. General Gates wrote his wife, “If old England is not by this lesson taught humility, then she is an obstinate old slut, bent upon her ruin.”

French Alliance

The French covertly purchased the bullets loaded into those rifles, as they did the solid cast de Valliere cannons that could shoot longer and straighter than their British counterparts. French arms dealer Pierre Beaumarchais funneled weapons to America and sent exaggerated reports to France about rebel heroics around Boston, hoping to convince King Louis XVI to side with them. The eccentric watchmaker and financier was a perfect cover since he was best known as a playwright who worked with Mozart on operas, including The Barber of Seville (1773) and The Marriage of Figaro (1778). The Americans couldn’t pay him in full but, nearly 200 years later, President John Kennedy wrote a check to his descendants.

The Saratoga victory was just the news Beaumarchais and Benjamin Franklin in Paris could parlay into an overt (public) alliance between America and France, a power still looking to avenge their defeat to the British in the French & Indian War. The question was whether or not the “United States” was for real and whether their soldiers could prove themselves on the battlefield against the British. Saratoga proved they could.

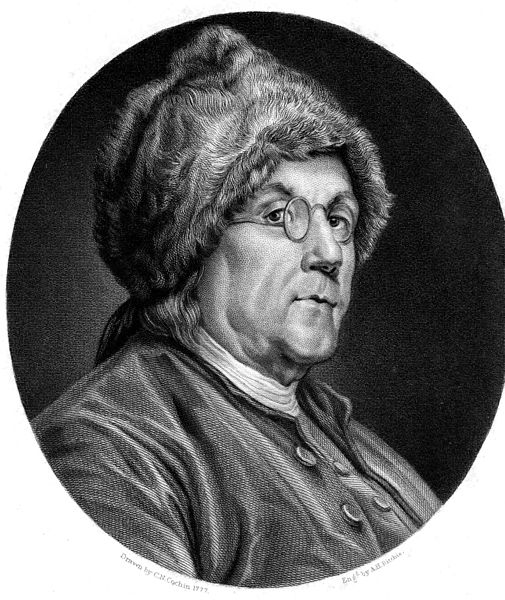

Franklin was too old to fight in this war but indispensable to victory because of his role as ambassador to France. He arrived in Paris in a coonskin cap similar to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s, pandering to the Enlightenment philosophes’ infatuation with the natural man and bearing his famous lightning rods as gifts. Hardly a woodsman himself, he’d ordered his costume from Canada and mainly liked it because it kept his head warm. Historian Jess McHugh said that the role-playing Franklin rose through the ranks of European society with a “fake it ’till you make it” strategy, showing cleverness and ambition on his part. The “electrical ambassador” was a crowd favorite in Paris, with his recognizable, bespectacled face appearing on various novelty items, including spittoons. King Louis XVI put Franklin’s likeness in his chamber pot because he was tired of the American celebrity stealing his thunder. Franklin even became Grand Master of the local Freemason lodge, Les Neuf Soeurs. Tailors sewed “insurgent coats” and “lightning-conductor dresses” while hairdressers created coiffures à la Boston and à la Philadelphia. Their attention wasn’t just on Franklin but rather the nascent American republic, with its emphasis on low taxes and disregard for monarchy. Unlike the British, who howled throughout the war about American hypocrisy regarding slavery, the French performed plays set in the idyllic Virginia countryside with enslaved workers and masters alongside each other singing about liberty.

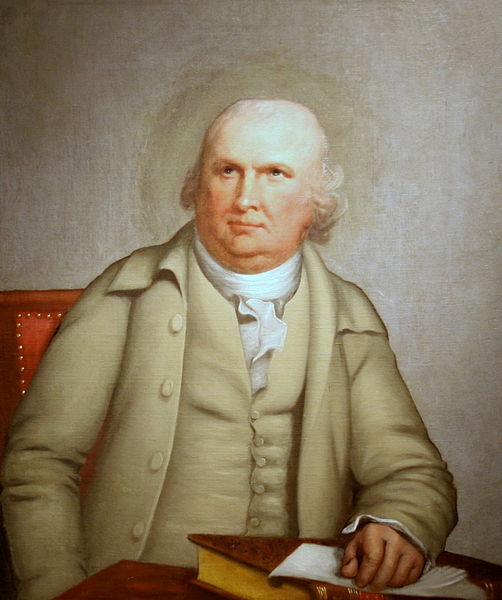

Franklin’s colleagues on the diplomatic mission, John Adams and Silas Deane, grew frustrated with his partying and frivolity but he was just biding his time. When news of the Saratoga victory hit Paris, conveniently after the French Navy had time to rebuild its fleet, Franklin struck while the iron was hot and secured a military and commercial alliance with France that obligated both to continue fighting against the British until the war concluded. His own secretary, Edward Bancroft, was a British double agent, but Franklin didn’t mind that the British knew about the potential French-American alliance (Bancroft got £1k annually from Continental Congress and a matching £1k from Britain). Simultaneously, Franklin cleverly sent peace feelers to the British he knew the French would intercept to increase his leverage. Miraculously, Franklin managed to coax a huge commitment from an absolutist French king to fund a republican revolution. Franklin graciously told Louis XVI, “if all monarchs ruled with your benevolence, there’d be no need for republics.” A lover of chess, this alliance was the best move of Franklin’s long career. For good measure, he enlisted European nobles, featured elsewhere in this chapter, that fought effectively with Washington’s Continental Army, including Baron von Steuben (Prussia), Marquis de Lafayette (France), and Casimir Pulaski (Poland).

This had repercussions as helping America came back to haunt Louis XVI. The commitment was so large that it bankrupted his monarchy and contributed to his overthrow in the French Revolution a decade later (Chapter 11), and Jefferson even helped revolutionaries draft their declaration. Spain and Holland joined the treaty, the last such European alliance the U.S. entered into until World War II. John Adams secured U.S. diplomatic recognition and a five million-guilder loan from the Netherlands while negotiating a trade agreement with neighboring Prussia. Adams’ embassy at the Hague, Netherlands was the first American embassy on foreign soil. Like the French, the Dutch and Spanish had provided covert aid to the Americans at Saratoga, before the formal alliance.

When wealthy American merchants learned that their loans to Continental Congress would be backed by European gold and silver, they grew more patriotic and agreed to 6% tax-free bonds to help finance the war. Those closest to Congress’ soon-to-be Superintendent of Finance, Robert Morris, learned of the impending alliance first and grabbed up the bonds. Morris mentored one of Washington’s young soldiers, Alexander Hamilton, who later shaped the country’s financial system as Secretary of the Treasury. A relieved Washington mollified (and motivated) his officers by paying them with the new bonds. This might seem like a dry offshoot of the war, but this bridge between government, the military, and finance is a big reason why the United States came into being. In retrospect, we think of the war’s participants as anticipating a great nation but, at the time, there wasn’t much motivation for the united in United States other than the war itself. The union nearly fell apart after the war but the interests of wealthy Americans and officers in redeeming their bonds helped stitch the union together. Many soldiers, though, were later embittered that they sold their land claims or bonds cheap, not realizing that the government really would pay them off.

While the Franco-American alliance was a huge boost to the Americans, it also rallied the English public more behind the war than they had been. Prior to Saratoga, many Britons weren’t interested and some Whigs even backed the American Rebels. With France in the war, the pro-American British faction fell silent, at least for a while, and more MPs (members of Parliament) and citizens started paying attention. Yet, more importantly, the Franco-American alliance dispersed the war geographically, making it harder for the British to focus on the North American mainland. It shifted the war south as the British moved the French navy and Caribbean to the top of their priority list and they abandoned Philadelphia to double-down on New York City.

War @ Sea

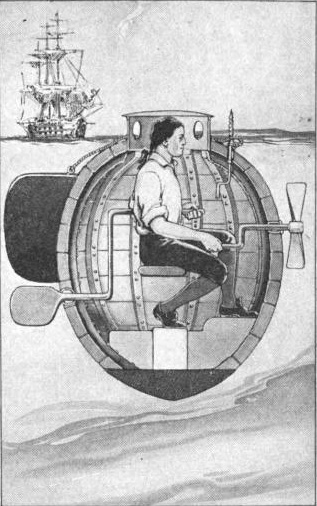

With more countries involved, the war spread to the Caribbean, Netherlands, Gibraltar, and India, at which point King George said it was “a joke” to continue worrying about “winning back Pennsylvania.” The British were concerned with holding Canada, protecting England from invasion, and fighting a worldwide naval conflict. Without a sizable navy, the U.S. harassed the British as best they could. Washington and Ben Franklin ran an informal navy of privateers (sanctioned pirates with letters of marque) numbering around 1500 vessels, that captured over 2k British ships. One of Franklin’s biggest goals, other than bedeviling the Royal Navy, was to seize hostages to trade back for American POWs. Patriot David Bushnell also constructed the first submersible in history used in combat, its interior lit with glowing fungi, though the Turtle failed in its mission to attach explosives to British ships in New York Harbor. It was difficult to maneuver and the British found the early submarine and sank it.

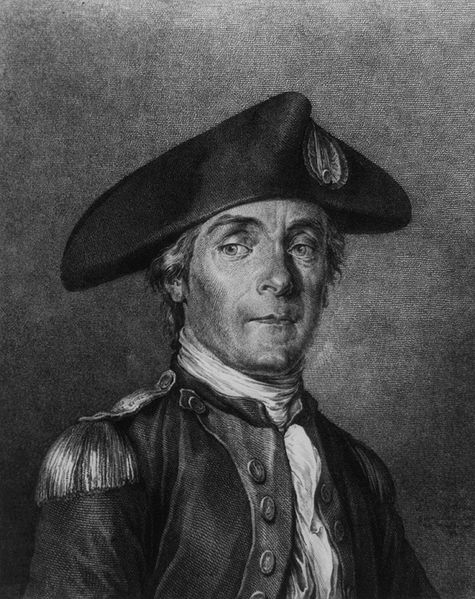

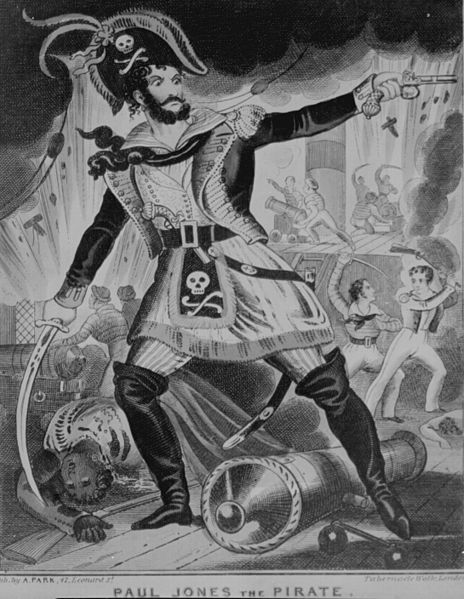

One of the Navy’s earliest leaders was Benedict Arnold, whose forenamed Driftwood Fleet stalled British advances on Lake Champlain in 1776. The U.S. also sent some ships off the coast of Ireland to attack the British on their way to America. The American Navy’s biggest hero was Scottish-born John Paul Jones, not to be confused with the namesake bassist from Led Zeppelin. French Queen Marie Antoinette’s milliner created a hat à la John Paul Jones with a plume she declared she’d like to put on his cap if she was so honored as to meet him. Notice the difference between the French and British portraits of Jones on the left and right.

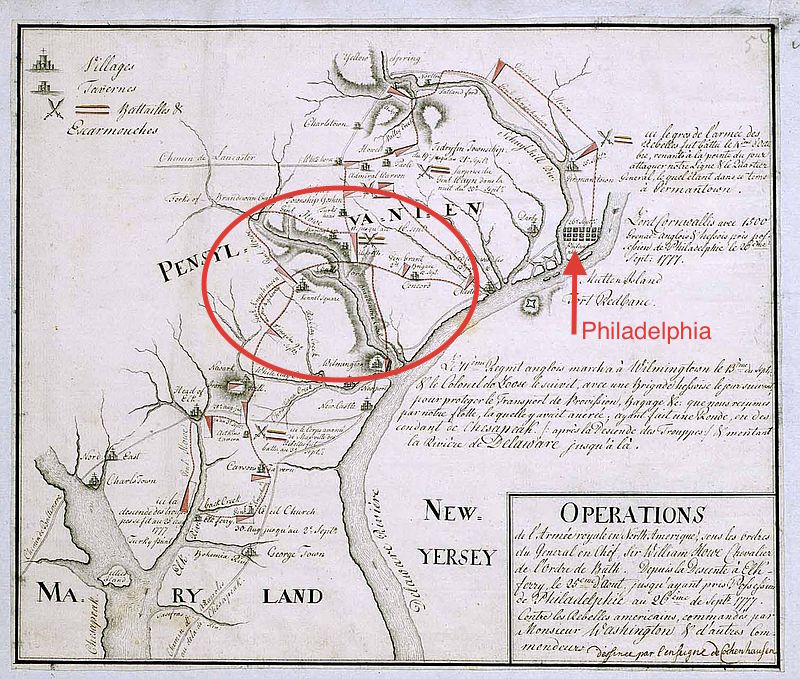

Hessian Map of Philadelphia Campaign (Brandywine), Marburg State Library (Germany) & West Jersey History Project (Text in French)

Philadelphia & Valley Forge

Word of the French alliance came none too soon for Washington. While British General William Howe left Johnny Burgoyne in the lurch by not going up the Hudson River to rendezvous at Albany (Saratoga), he succeeded in taking the key enclave of Philadelphia in September 1777. Washington’s army put up a stiffer fight than they had in New York but Howe still prevailed at the 11-hour Battle of Brandywine Creek on 9/11, sending 12k Continentals into retreat (circled in the map above). The Redcoats soon seized the Patriot capital, though Rebels held on to Fort Mifflin on the Delaware River south of Philadelphia despite experiencing the worst bombardment of the war from 250 British warships pounding them with a thousand cannonballs per hour for five days.

A second bright spot was the heroics of another Polish immigrant, Casimir Pulaski. Pulaski was renowned for his horsemanship in Poland’s struggle for independence from Russia and Benjamin Franklin recommended him to Washington. When he arrived in Boston from France, he wrote Washington: “I came here, where freedom is being defended, to serve it, and to live and die for it.” He made his way to Washington’s camp and led a daring mounted charge at Brandywine that prevented the British from capturing Washington (likely ending the Revolution) and went on to train the United States’ fledgling calvary as a brigadier general.

Sidenote: When historians and archaeologists moved Pulaski’s remains from a plantation to his monument in Savannah, Georgia, they noticed that his bones more resembled those of a woman than a man. Upon further examination, they determined that the “Father of the American Cavalry” was intersex. His Polish baptism records Pulaski as female with a debilitatadis (debility).

In the winter of 1777-78, Washington struggled to keep his ragtag army together at Valley Forge, their fort north of Philadelphia on the Schuylkill River. They’d fought well enough defending Philadelphia to gain confidence but still needed to hone their skills. The heroic defense of Ft. Mifflin bought them enough time to retreat to Valley Forge after the Brandywine defeat. Washington brought Pulaski with him to help augment their infantry with cavalry. They built a secure fort at Valley Forge but many soldiers still died of flu, typhus, typhoid, scurvy, and dysentery while apathetic civilians sold food to the British, who paid higher rates. Oneida People brought corn to the hungry troops. Some men froze to death and Washington personally shot captured deserters. It’s no wonder that someone once said of the American Revolution that “Seldom have so few done so much for so many” — a phrase British Prime Minister Winston Churchill recycled to praise the Royal Air Force after the German Blitzkrieg during WWII. After the war, tight-fisted taxpayers in some states didn’t even authorize the promised gift of land to soldiers whose sacrifice won them their independence.

Many officers, including those like Benedict Arnold and Horatio Gates who had proven themselves at Saratoga, questioned whether Washington should even be in charge as commander since he did not have an impressive battlefield résumé. But Washington had wisely repositioned Arnold just before Saratoga, sending him north to help Gates fight Burgoyne, precisely the sort of move that one would expect of a good commander. And, to his credit, Washington realized that battlefield strategy was not his strength. He was not a battlefield tactician; why would he be since he was, by trade, a tobacco farmer? His men weren’t disciplined enough in battle, either. It’s one thing to hoot and holler and fire off a few rounds while hiding behind a stone wall like the Minutemen did during the British retreat from Lexington and Concord. It’s quite another to confront a real army and stand your ground in the face of gleaming bayonets when you’re not trained.

With his back against the wall at Valley Forge, Washington made three key choices. First, with what little funds Congress could muster, Washington imported his own mercenary to drill his troops: Prussian General Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the French & Indian War. Steuben communicated with Washington and the other officers through a French interpreter. Steuben drilled the troops in the formal art of war as it was then practiced in Europe, teaching them to reload faster and how to fight with bayonets, march more efficiently, and counter-attack in battle. Washington’s men were using their bayonets as tools and eating knives but hadn’t learned to fight with them in close quarters, where they were more effective than difficult to load muskets.

Steuben also had a little heart-to-heart with Washington about leadership. He encouraged Washington to not go so rough on his troops all the time and to thank them for their sacrifice and service – to inspire rather than just coerce them. He helped Washington teach his men to “relish the trade of soldiering,” a tough sell in any century, let alone the 18th. While it may have seemed like an abstract pipedream to freezing, sick soldiers and may seem corny today, they needed to be reminded that the war would lead to a new republic. If you pardon a football analogy, it was time for the halftime speech. Steuben also set up a better sanitation system and encouraged officers living off-site with their wives to return to camp.

Second, Washington tricked the British into thinking that his army was bigger than it was. With many of his men sick and others disgruntled, cold and hungry, the Redcoats probably could’ve destroyed them right then and there by attacking Valley Forge, ending the revolution. Washington made public proclamations to the effect that his army was roughly 40k, knowing the British would never believe it. Simultaneously, he forged detailed inventories of his army and supplies showing his “true” strength to be only around 9k, not 40k. Historians disagree on how large, exactly, the Continental Army was at that point, but most agree it had shrunk to something far smaller than that. Washington saw to it those documents fell into the hands of known British spies who relayed them to General Howe. Howe didn’t think he could take down an army quite as large as 9k and chose to wait until the following spring to engage. This episode is a good example of why it’s helpful to leave moles in place once you discover them because they’re ideal for conveying misinformation. As we saw, Franklin did likewise in Paris.

A third smart move was Washington’s inoculation of troops against smallpox, the most feared “distemper” of the era. Inoculations originated in China, India, and the Ottoman Empire. They were still just gaining traction in the colonies and understandably so; it was counterintuitive to give people a little dose of disease to prevent them from getting more. Puritan minister Cotton Mather (1663-1728) promoted inoculations in New England, having learned about them from an enslaved worker, but Edward Jenner didn’t prove that patients acquire immunity to the satisfaction of science until twenty years after the Revolutionary War. Jenner was first to develop a separate vaccine as opposed to an inoculation, using cowpox (vaccine derives from the Latin for cow). Great Awakening theologian and Princeton president Jonathan Edwards (Chapter 7) had died of an inoculation twenty years before Valley Forge and Congress opposed the idea. At first, Washington also opposed the practice, and even forbade his soldiers from being inoculated in 1775-76 because he feared it would weaken them. But he’d changed his mind by 1777 as the outbreak worsened among his men, and he was receiving complaints that they were spreading it to their hometowns on leave. There were no hypodermic needles for an easy shot. Doctors cut the patient and infected him with a small dose drawn from a victim’s pustules. Washington understood the science behind the idea, partly because he knew that he’d been immune himself since a non-lethal bout with smallpox as a boy. And he realized that epidemics were the scourge of 18th-century armies.

Just as it’s impossible to understand World War I apart from its contemporaneous Flu Pandemic, the Revolutionary War was inseparable from smallpox and malaria. Many young men didn’t volunteer for either side to avoid high odds of contracting smallpox or bringing it home to their families. In the previous chapter, we saw that one motivation for writing the Third Amendment against the quartering of troops in private homes was fear of smallpox and that applied to both Redcoats and Washington’s troops. The Continental Army spread smallpox in Morristown, New Jersey the summer after Valley Forge (1777) when they invited themselves into private homes, after which Washington inoculated civilians. For armies, one big round of smallpox could result in defeat, which in the case of Valley Forge would’ve ended the U.S. before it really started. Whereas ~ 30% of smallpox victims usually died, only one in fifty (2%) of Washington’s inoculated soldiers lost his life. These inoculations, along with the tireless work of a dedicated staff of surgeons and nurses, helped keep the Continental Army intact. Malaria, in turn, rendered large numbers of Redcoats inactive but Americans had better immunity to it. Historians estimate, astonishingly, that around of half of the people that have ever lived (52 billion) have died of malaria. But at least the mosquitoes that carry the disease helped launch the United States.

The revitalized troops got a chance to prove themselves the following summer when they intercepted British Commander-in-Chief Sir Henry Clinton’s Redcoats at Monmouth, New Jersey, as they marched from Philadelphia to New York. The Redcoats chose to abandon the capital they’d fought so hard to win the previous year because they feared a French naval blockade would trap them there (Philadelphia is an inland port). In sweltering heat, the Continentals fought the Redcoats to a draw at Monmouth in a traditional European-style pitched battle. They held the field at the end of the day and the British re-routed to the coast to catch boats to New York. Townswomen later immortalized as Molly Pitchers brought pitchers of water to thirsty Rebels and some “manned” cannons. Several American women also fought in rebel armies disguised as men, most famously Deborah Sampson, who was honorably discharged after fighting for a year-and-a-half. A British counterpart doing likewise in the Royal Navy is the subject of the traditional ballad “Jack Monroe,” later covered as “Jack-A-Roe” by Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, and the Grateful Dead.

Washington had the nagging sense that his army could have won the Monmouth battle outright if not for the hesitancy of General Charles Lee, whom he reluctantly charged with leading the assault instead of French General Marquis de Lafayette. Believing he was outnumbered roughly 2:1, Lee retreated even after he had Clinton’s troops on the run and was later court-martialed because Washington had ordered him to pursue. Washington never discovered the full truth but General Howe’s relatives did many years later. Rummaging through his desk, they found documents suggesting that Lee might have been paid by the British to fight ineffectively that day.

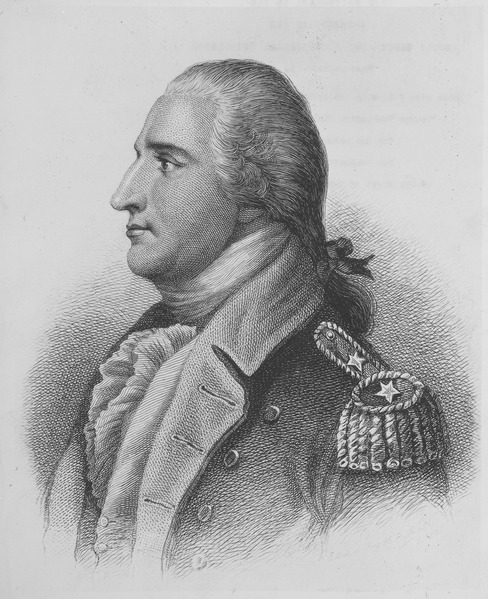

Treason & Espionage

The next year, Washington became fully aware of an even more notorious traitor: Benedict Arnold. Arnold was so effective early in the war — at New Haven, Fort Ticonderoga, Lake Champlain twice in 1775 and ’76, and Saratoga in 1777 where he defied orders and stormed back into battle after Horatio Gates relieved him of his command — that some have argued the U.S. would never have won the Revolution without him. Gates tried to take credit for Saratoga but soldiers reported that Arnold was the true hero, leading a courageous charge. Moreover, Arnold helped form the “original eight” of the U.S. Marines Corps (naval infantry) in 1775 at Tun Tavern.

Yet, his treason in 1778 is so infamous that Arnold’s name is synonymous with traitor. Why did he do it? Arnold resented not being credited with what he’d done on the battlefield, especially at Saratoga where he’d shattered his leg, leaving the left two inches shorter than the right. Instead, he’d been passed over for promotions in favor of seemingly lesser men. Washington seemed to be in his corner, but no one else. Privately, Washington wrote Arnold that he’d only passed him over for major general because he feared other men would quit if he didn’t award them. Arnold then tried to quit twice and both times Washington refused to accept his resignation. Radical Patriots in Congress led by Joseph Reed even tried to convict him on (trumped-up?) smuggling charges, though he was exonerated in a court-martial. This was a lot to take for the man that Johnny Burgoyne, in his testimony before Parliament, claimed was personally responsible for his defeat at Saratoga, the most important battle of the war. But there was increasing tension throughout the states/colonies between Continental regulars (especially officers) and militias. Local authorities hired militiamen as thugs when they were home to harass pacifists or people whose loyalties they suspected. Arnold rode an ostentatious carriage and was known to wear red, of all colors, on occasion. After the British evacuated Philadelphia, even the Continental Army’s best soldier didn’t escape these vigilantes’ wrath. Militias and Congress might have convinced Arnold to reconsider his loyalties, thus inadvertently causing the treason they falsely suspected. In May 1780, the exasperated Arnold wrote Washington: “Having made every sacrifice of fortune and blood, and become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet the ungrateful returns I have received of my countrymen, but as Congress have stamped ingratitude as a current coin I must take it. I wish your Excellency for your long and eminent services may not be paid off in the same coin.” In retrospect, this letter might be interpreted as a fond farewell, as Arnold had changed sides within a few months.

After one failed courtship with another woman, Arnold married Peggy Shippen, recycling the same love letters he wrote to the first. The Shippens, if not outright Loyalists, were better off when the British occupied Philadelphia and certainly didn’t favor the revolutionary government that was persecuting Arnold. The newlyweds’ lavish parties ran the couple into debt. As a Protestant, Arnold also felt betrayed by the American alliance with “papist” (Catholic) France. For him, that was like making a deal with the devil. All this made Arnold a “turnable” candidate for the British to approach. For a sum of ~ $130k in today’s money, the British bought Arnold, keeping him embedded on the American side.

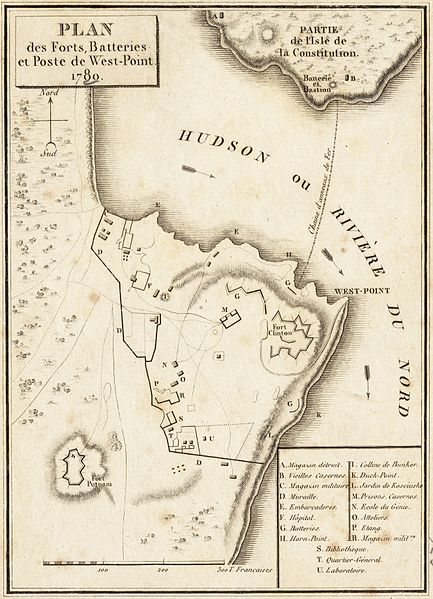

Later that summer, Washington entrusted Arnold with a strategic spot at West Point, where the Hudson River curved enough that vessels needed to slow down. Rebels laid a chain netting most of the way across the river to Constitution Island hoping to ensnare the slowing boats as they rounded the bend, to assault them from batteries along the bank. The key spot would later become site of the United States Military Academy (1802). Had the British captured West Point, they would’ve controlled the Hudson, dividing the middle and southern colonies from New England. Today, West Point has a statue overlooking the Hudson of its main designer, the forenamed Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko.

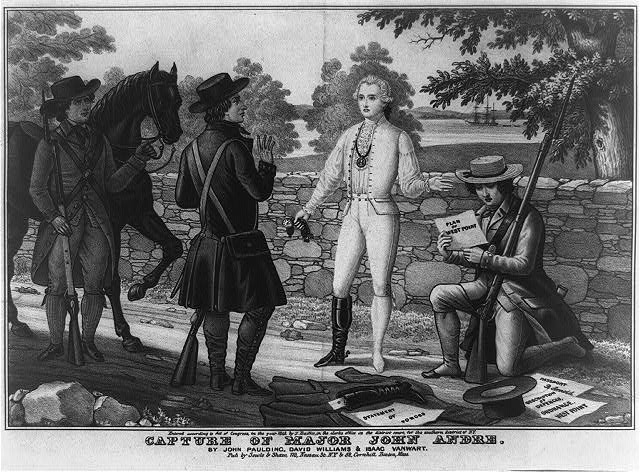

However, three AWOL Patriot soldiers coincidentally happened to mug Arnold’s civilian-dressed go-between, William Howe’s Major John André, as he relayed the fort plans to the British. They didn’t want his wallet but rather his sharp-looking boots; at least that was the dashing officer’s story. Unfortunately for Arnold and André, that’s where André stashed the plans. The official version the Patriots told was that they just interrogated André when they discovered he was a British officer behind enemy lines and found the plans in his stockings after removing his boots.

Capture of Major John Andre by John Paulding, David Williams & Isaac Vanwart, Lithograph by J. Baillie, 1845

Washington interpreted André’s capture as so unlikely and coincidental that it could only be explained by divine intervention, or Providence as he called it. He wanted to swap André for Arnold so that he could punish the traitor but the British valued Arnold more than André for his military prowess (he was commissioned as a brigadier general but given a low salary since his plot had failed). Andre’s capture wasn’t just luck or Providence; it was a case of Washington’s own carefully cultivated espionage paying off.

The future first president employed spies in and around occupied New York, the Setauket or Culper Ring led by Benjamin Tallmadge, that kept their ears to the ground for British troop movements. Their main source of news and information in Manhattan was Quaker Robert Townsend, whose father owned a home on Long Island that spies met in. The Culper Ring alerted Washington that he had traitors among his officers and bodyguards. Tailor and agent Hercules Mulligan also prevented Washington’s capture by warning him in time through his courier slave, Cato (New York’s loyalist governor William Tryon was part of a conspiracy to kill Washington). Spy Abraham Woodhull, alias Samuel Culper, was the central character in the AMC mini-series TURN: Washington’s Spies (2014-17) — a story that never would’ve come to light if a sharp-eyed Long Island historian in the 1930s hadn’t noticed the similarity between Townsend’s handwriting and some he’d seen in anonymous, coded letters to Washington.

Washington relished espionage and tradecraft, keeping up with state-of-the-art invisible ink and alphanumeric ciphers, and he relied on the Culper/Setauket group to keep him informed about the greater New York area. The Culper Ring — including Tallmadge, Townsend, Woodhull, Anna Strong, and Robert Brewster — was crucial to keeping the Revolution alive in the North as the fighting shifted toward the South and Caribbean. Not only did they help foil Arnold’s plot to capture the key fort on the Hudson, they helped the French navy find safe harbor in America. In 1780, the spies learned that the British knew of the impending French landing at Newport, Rhode Island, so Washington used misinformation (counter-espionage) to feign an attack on New York. The British waited there for an attack that never happened, leaving Newport open for the French. The French then sailed from Newport to Virginia to trap the British at Yorktown, as we’ll see below.

Arnold’s plan wouldn’t have been foiled without the Culper Ring and, since Washington was visiting West Point, the British might have captured him. The boot-stealing Patriots delivered John André to Ring members. They took their prisoner to the Old ’76 House tavern in Tappan, New York, where they extracted the requisite information that Arnold was the ringleader of a treasonous plot to relinquish West Point to the Brits. His job was to keep enough men out collecting wood or on other duties that the fort wasn’t fully manned and to relay information about the fort’s layout so that the British would know what to expect when they laid siege. They also considered another kidnapping plot on Washington during one of his visits there.

André’s capture unfolded the very day Washington arrived at West Point to check up on things. He found the traitor’s abandoned, pregnant wife Peggy upstairs at their headquarters. Because of a dispatch that he mistakenly received intended for Washington, Arnold had already figured out the jig was up and fled the scene, leaving her behind. Much was made at the time about how Washington comforted Peggy as she went into a deranged, hysterical fit. However, in the 1920s, historians uncovered documents in the Sir Henry Clinton Collection indicating that it was all an act and that she’d likely orchestrated the whole plan. Women played a significant role in the boycotts leading up to the war, participated in battles as we just saw at Monmouth, and the most important propagandist/early historian of the war was Mercy Otis Warren. So too, it’s possible that Peggy Shippen Arnold was behind the most infamous treason in American history.

Women also worked for the American side against the British. Since most men assumed they weren’t interested in politics or didn’t form their own opinions, Rebel women made ideal spies for overhearing conversations from Loyalist husbands, friends, and extended family. They devised ingenious ways to send messages, including particular ways to hang clothes on the line, as Anna Strong did for the Culper Ring to signal which inlet Robert Brewster would pick up information in before rowing the 12 miles back across Long Island Sound to Connecticut. There’s some evidence that a woman known only as Agent 355 might’ve used her relationship to John André to alert the Culper Ring to Benedict Arnold even before the boot-stealing affair that nabbed André.

After Arnold’s defection, the demoralized Washington realized that, aside from his under-sized, under-funded shrinking army, he now had his most trusted, talented general selling secrets to the British. The Continentals reluctantly hung André. I say reluctantly because the major was so charming that even his captors had come to like him and respect his bravery. After Washington turned down his request to go before a firing squad, André refused to be blindfolded and wrapped the noose around his neck himself.

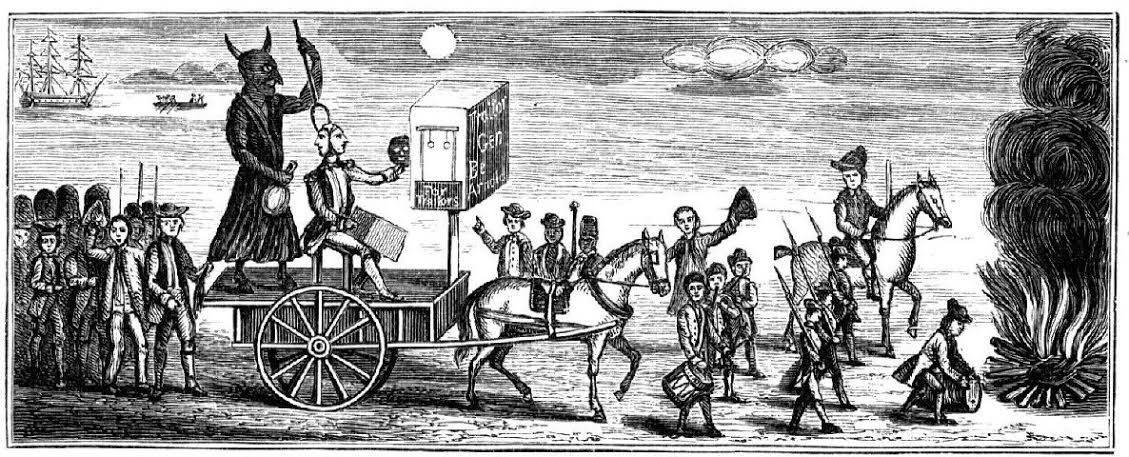

Philadelphians Paraded A Two-Faced Effigy Of Arnold Through The Streets Before Burning It, Library of Congress, 1780

As for Arnold, his legacy was destroyed in the U.S. but there’s no denying his early and crucial role in the war. He died in 1801 wearing his Continental Army blue with the sword-knot and epaulets that Washington awarded him, saying “Let me die in my old uniform, the uniform in which I fought my battles. God forgive me for ever putting on any other.” Today there’s a monument at West Point to honor the best generals of the Revolutionary War. One is conspicuously blank but everyone knows it represents Arnold. Saratoga National Historical Park, where Arnold injured his leg, has a monument of just his boot that reads: “In memory of the most brilliant soldier in the Continental Army, who was desperately wounded on this spot, winning for his country the decisive battle of the American Revolution, and for himself the rank of Major General.”

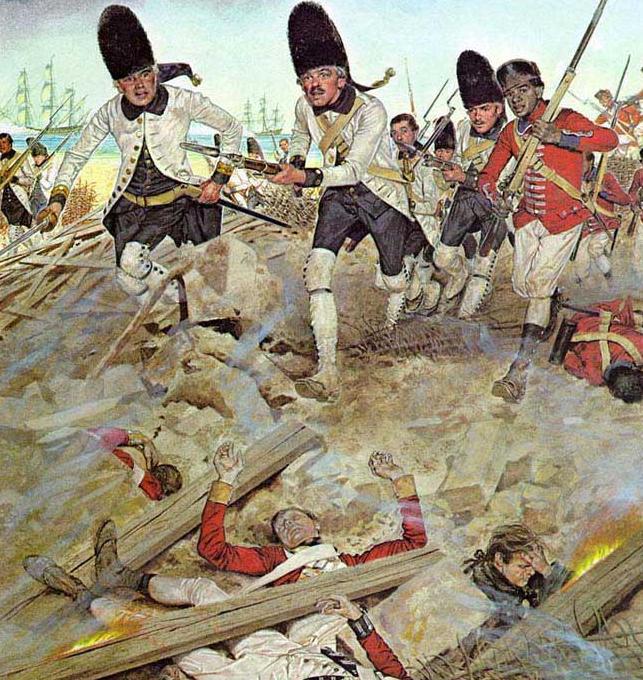

Spanish Grenadiers & Militia Pour Into Ft. George in Battle of Pensacola, Florida, U.S. Army Center of Military History

Southern Civil War

The silver lining in these clouds was the French and Spanish alliance, which especially helped American Rebels in the South. The Spanish fought the British in Louisiana, the Caribbean, and West Florida. An army of Indians, free Blacks, Creoles, and Spanish under Louisiana Governor Bernardo de Gálvez (Galveston’s namesake) defeated Redcoats for control of Natchez, Baton Rouge, and Mobile. Then, his hurricane-battered navy defeated the British in the two-month Siege of Pensacola in 1781. Encircling the British around the southern perimeter of the colonies prevented their northern troops from being resupplied from that direction and forced them to fight on two fronts. Tying up Redcoats in Pensacola prevented them from fighting in some of the critical southern battles we’ll discuss below, including Yorktown, and Spanish naval help guarding Cap Francois, Haiti freed up French ships to fight the Royal Navy in the Atlantic. Even before the alliance, Gálvez helped Patriots by shuttling weapons, medicine, and fabric for Continental uniforms up the Mississippi River duty-free in exchange for hemp, flax, furs, and meat.

The French supplied much-needed money for the Continental Army and the American rebellion became secondary from the British perspective — put on the back burner in favor of securing fishing rights in the North Atlantic and gaining territory in the sugar-rich Caribbean from the French. The Caribbean factor also swung the center of gravity in the mainland American war south, where the fighting between American Loyalists and Rebels was intense. It’s easy for modern Americans to forget that the Revolutionary War was also a civil war. Southern Loyalists stood their ground. The British tried the enclave (port) strategy in the South, holding Savannah, Georgia but failing to take Charleston, South Carolina until late in the war. In the Siege of Savannah, free black French-Haitians fought alongside Americans trying to capture the city.

Painted by William Ranney in 1845, this depiction of the Battle of Cowpens shows an unnamed black soldier (left) firing his pistol and saving the life of Colonel William Washington (on white horse in center).

American troops under Nathaniel Greene led British troops under Cornwallis and Banastre “the Butcher” Tarleton on a wild goose chase across the Carolinas that included battles at the Cowpens, King’s Mountain (between rival American militias), and Guilford Courthouse. At times, the Rebels survived on alligators and frogs. Tarleton got his nickname because he violated an unwritten code of 18th-century conduct. After fighting ceased around sundown, it was customary to quit the battlefield and allow your opponents to treat and retrieve the wounded. However, a misunderstanding occurred at the Battle of Waxhaw when a Rebel musket ball hit Tarleton’s horse just as he was asking for quarter. The British thought someone had deliberately shot at Tarleton himself as he was raising the white flag and he instructed his men to go around and finish off all the American casualties with bayonets. Tarleton also had a reputation for wreaking havoc on the civilian population, raiding and pillaging in a manner that presaged Sherman’s March through Georgia in the Civil War.

One hero for the Rebels was South Carolinian Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox,” who led guerilla-type raids on the British, eluded Tarleton’s capture, and was the subject of the only profitable movie ever made about the Revolution: The Patriot (2000). The movie’s savagery is accurate, except that it was true of both sides, not just the British-Loyalist. Mel Gibson’s Marion character, whom historian Sean Busick called “an 18th-century Rambo,” is based on that of Parson Weem’s 19th-century semi-fictional account. Weems was the hagiographer who invented the story of young George Washington cutting down the cherry tree.

Yorktown

The long fighting in the Carolinas had served a purpose, wearing down the British and exhausting their supplies. After rebel victories at the Cowpens and King’s Mountain, demoralized British troops made their way up to Virginia where, led by Benedict Arnold, they sent the state’s governor, Thomas Jefferson, galloping away from his home atop Monticello as they neared. Jefferson’s enemies seized on his seeming cowardice and it bothered him the rest of his life, but the Revolution needed Jefferson alive (likewise, during WWII America didn’t need John Wayne on the battlefield; they needed him making movies about the battlefield).

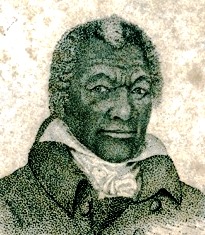

James Armistead Lafayette, After Painting By John Martin, ca. 1824, Cropped From Image @ Virginia Historical Society

Cut off by the Spanish from the Gulf of Mexico, the British marched to the tip of the Yorktown Peninsula in Virginia to be resupplied by ships from New York. They sent enslaved spy James Armistead to learn more about American and French movements, not realizing that Armistead was actually a double agent, posing as a runaway slave from Rebels, who told the Rebels about the British whereabouts at Yorktown. Armistead worked first for Arnold after Arnold switched sides, even mapping routes for him, then infiltrated Cornwallis’ camp. Based on Armistead’s intelligence, and with help up north from the forenamed Culper Ring that helped the French secure Newport, Rhode Island, this is when Washington feigned an attack on New York before diverting south along with his trusted French sidekick, the Marquis de Lafayette. All the Lafayettes and Fayettevilles across America? That’s who they’re named after. When Lafayette returned to the U.S. in 1824 on a reunion tour, 43 years after Yorktown, he recognized the elderly Armistead in the crowd. He stopped the carriage and ran to embrace him. Armistead had added Lafayette to his name in 1787 when the Virginia Assembly freed him to honor his service. He became a successful Virginia landowner and acquired three enslaved workers, along with receiving a military pension. As for Benedict Arnold, we suggested above that, despite his treason, he fought so effectively earlier in the war that the Rebels — “we” for most readers — might not have won without him. Arnold also helped the Rebels by feeding intel via James Armistead Lafayette.

Washington, Steuben, and Lafayette joined with French forces led by Comte de Rochambeau. French forces outnumbered American at ~ 4:1 ratio. With the French Navy blockading the Chesapeake, they had the British trapped at the end of Yorktown Peninsula. Under François Joseph Paul de Grasse, the French fleet won an underrated but major engagement with the British off Virginia’s shore known as the Battle of the Capes in September 1781, aka the Battle of the Chesapeake (above). Cornwallis scuttled much of his fleet on the York River to block the French (circled in red below), but they were trapped from either approach, land or sea.

From the York River’s banks, French artillery used hot-shot (furnace-heated cannonballs) to set ablaze the timber, spars, and rigging of the 44-gun HMS Charon, sending Cornwallis’ biggest warship to the river bed where it still sits.

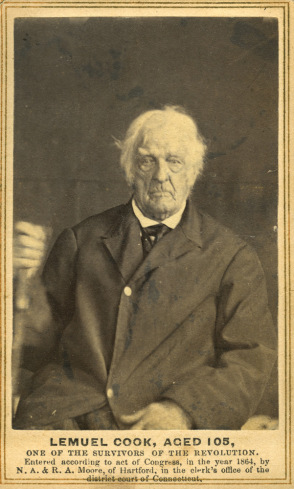

After the protracted Siege of Yorktown on land, Cornwallis surrendered 30k Redcoats in October. Animated Map (Last Slide) According to one veteran of the campaign, Lemuel Cook (right), Washington instructed his men to not laugh at the British because it was “bad enough to surrender without being insulted.” After the battle, Americans including Washington and Jefferson retrieved enslaved workers that had gone over to fight with the British, though twelve of Washington’s slipped away. Washington was also upset that the French fleet then left the colonies because he wanted them to stay to help liberate Charleston and New York. He wasn’t envisioning the war as over after Yorktown, which indeed it was not.

The Yorktown loss wouldn’t necessarily have meant the British lost the war. No one at the time saw the battle as a “roll the credits” moment. Brits still occupied the ports of Charleston, Savannah, and New York for another year and Washington’s army had shrunk to 5k men. Another 20k slaves escaped with the aid of the British when they finally did retreat in 1792. Even as late as 1783, a combined force of British, American Loyalists (free and enslaved), and Chickasaw Indians attacked pro-American French and Spanish troops at Arkansas Post, near the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers. However, support in England for war against the colonies was evaporating by 1781 and Yorktown and the preceding civil war in the Carolinas discouraged American Loyalists. Whigs who sympathized with American independence now controlled Parliament and the English public had long since lost any interest in the rebellion. King George III saw Yorktown as a mere setback, but the defeat convinced Prime Minister Lord North to cut his losses in the colonies and focus on the broader naval battle with the French and Spanish. Who would the newly independent Americans conduct most of their trade with? Probably, the British anyway. The British could now profit from American trade without the hassle or overhead of governing their surly subjects. Moreover, given America’s military weakness minus French aid, the British wouldn’t need to comply by whatever terms they agreed to at war’s end.

Siege of Yorktown (Rochambeau & Washington), October 1781, Auguste Couder, 1836, Palace of Versailles

Outcome

In retrospect, though not obvious at the time, the United States was in effect an independent country as of October 1781, but the broader war between France/Spain and Great Britain didn’t end until 1783. The American independence portion wasn’t an easy victory. The roughly 25k casualties represented 1% of the population, the equivalent of over three million today. While the military fight was an uphill struggle and one of the most violent wars in American history measured by casualty rate, the difficult task of building a new country lay ahead. Insofar as it was a tax revolt, the Revolution backfired because Americans soon found out it’s more expensive to run a country than to be another country’s colony. Still, the colonists had independence and could represent themselves politically, at least those who owned a fair amount of land.

Congress could not come through on their obligation to help the French over the next two years of their war with Britain, but at least they did not double-cross France and sign a separate treaty with the British. In the meantime, the British kept American privateer POWs on board the HMS Jersey (aka “Old Jersey” or “Hell”) for the two years between 1781-83, during which time hundreds more died from diseases, starvation and torture. Both sides tortured POWs during the war.

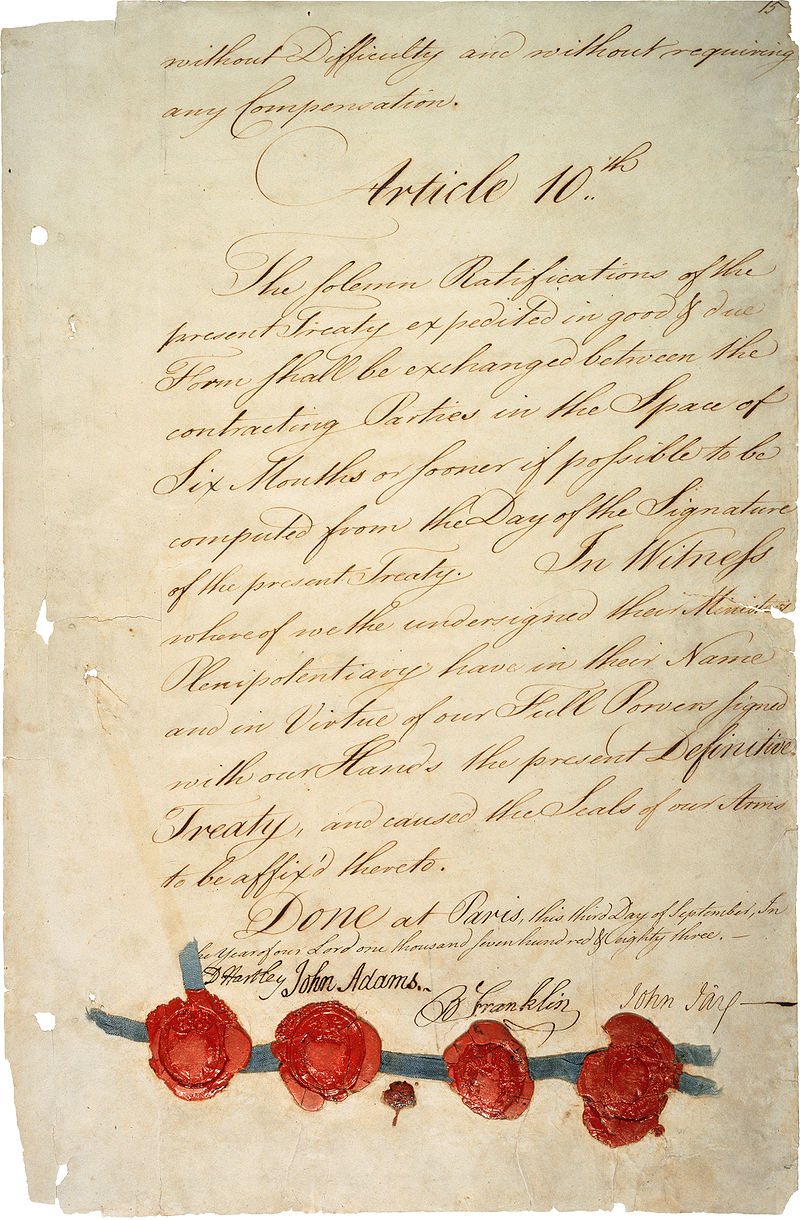

Meanwhile, the broader war raged on as British and French navies fought in the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean, and North Sea/English Channel. By 1783, the dispute that started in Boston over taxes and smuggling was a sprawling global conflict ranging from Gibraltar to Senegambia (West Africa) to India to Indonesia to Guyana, Jamaica and the Bahamas in the Caribbean, finally ending with French victory at the Battle of Cuddalore in the Bay of Bengal in June 1783. Britain coveted Indian cotton, silk, textiles, opium, spices, tea, and precious stones even more than anything in North America, and successfully fended off a French takeover there despite that naval loss, which was actually months after the ink had dried on the Treaty of Paris (above) that officially ended the war. If not a world war in the modern sense, the Revolutionary War was one of the periodic global jostles for power that marked the colonial age.

And conflict continued in North America as the young U.S. contended with Native Americans on the western frontier. During the Revolutionary War, tribes constituting the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy, were divided on whom to side with, especially since the Confederacy’s Great Law of Peace dictated that they think ahead multiple generations as to what served their long-term interests (Iroquois, in effect, tried to bring their descendants in on their decision-making). Mohawk Joseph Brant led Indian and white Loyalist forces against the Rebels. He was an important enough Iroquois leader to have met George Washington and King George III in England. Other Iroquois tribes (Seneca, Onondaga, Cayuga) also sided with the British and were consequently wiped out by American forces. In the words of historian Caitlin Fitz, “Colonial and Indian towns alike were burned to ashes, crops destroyed, heads skinned, skulls shattered.” Troops led by General John Sullivan and directed by Washington decimated the British-aligned Iroquois tribes of upstate New York in 1779, burning 40 villages in North America’s oldest democracy. Iroquois called Washington Hanodagonyes, or “town destroyer.” Iroquois tribes like the Oneida and Tuscarora that allied with American Rebels didn’t fare much better in the short term or any better at all in the long term than those that sided with the British, though in 1778 Washington credited Oneidas with helping to win back Boston and Philadelphia and aiding at Valley Forge. Elsewhere, Washington did not order Pennsylvania militia to club and scalp to death nearly a hundred Christian Lenape (Delaware) men, women, and children who were not allied with the British in the Gnadenhutten Massacre (1782), but neither did he pursue bringing the killers to justice. Conflict between settlers and Indigenous Americans along the western frontier spun out of the Revolutionary era and continued for years after. Thomas Jefferson set the tone for future American leaders by calling American Indians “merciless savages” in the Declaration of Independence. General Washington likewise called them “merciless and savages” and “wolves and beasts” who deserved nothing but annihilation at the hands of Whites, though he later mostly favored diplomatic over violent solutions.

The war also sectionalized slavery. We naturally think of the Civil War as abolishing slavery, but the Revolution led to abolition in northern states. Less dependent on slaves economically, they found the Declaration of Independence incompatible with the institution and, one-by-one, abolished slavery after the war. Pennsylvania, with its Quaker population, was the first in 1777, and New York and New Jersey last by 1830s, with most of the illegal slave trade running through Rhode Island. In Massachusetts, slaves Mum Bett (right) and Quock Walker sued the state for their freedom and won, leading to statewide abolition. Upper Southern states also debated slavery and some made it easier to manumit enslaved workers, but the practice held there and went unchallenged in the Deep South. Northern states replaced slavery with a system of segregation and discrimination toward their relatively small black populations that later served as a template for the post-Civil War “Jim Crow” South.

The war also sectionalized slavery. We naturally think of the Civil War as abolishing slavery, but the Revolution led to abolition in northern states. Less dependent on slaves economically, they found the Declaration of Independence incompatible with the institution and, one-by-one, abolished slavery after the war. Pennsylvania, with its Quaker population, was the first in 1777, and New York and New Jersey last by 1830s, with most of the illegal slave trade running through Rhode Island. In Massachusetts, slaves Mum Bett (right) and Quock Walker sued the state for their freedom and won, leading to statewide abolition. Upper Southern states also debated slavery and some made it easier to manumit enslaved workers, but the practice held there and went unchallenged in the Deep South. Northern states replaced slavery with a system of segregation and discrimination toward their relatively small black populations that later served as a template for the post-Civil War “Jim Crow” South.

Other Black Loyalists fled the country with the help of British forces, with most ending up in Nova Scotia (Canada) and London, and some later migrating to Sierra Leone. In the near term, the brutal economics of cotton compromised the higher ideals of the Revolution, as slavery grew in importance in the 19th century. Keep in mind, though, that the British had promised freedom to enslaved Loyalists. If they had won and actually followed through on that promise (another big if), then a failed Revolution would have abolished slavery in all of British America. British abolitionism in the war was mainly strategic, though, so we shouldn’t assume that they would’ve actually freed enslaved workers if they won. Human bondage was legal in the British Empire until 1833.

American independence prevented England from using its American colonies as a dumping ground for criminals (they’d also transplanted formerly incarcerated debtors in Georgia colony). Consequently, they founded Australia in 1788, leading to more displacement of indigenous peoples and seeding another major country on the other side of the globe. Prior to 1853, they offshored many convicts to nearby Tasmania, the island on the map above southeast of the mainland.

Conclusion

The Revolutionary War raised more questions than it settled. Could the U.S. survive economically? Who would govern the new country and how? Could the former British colonists sustain republicanism? Washington’s army wasn’t much in 1781, but neither was Congress and he probably could have declared himself king. But, at the nation’s first capitol in Baltimore (today’s Maryland State House), he literally and figuratively laid down his arms (sword) before Continental Congress, establishing a precedent that is easy for modern Americans to take for granted but doesn’t usually follow from revolutions: the military being subsumed under civilian, political control. Though only property-holding white males could vote in eleven of the states, the same as under the British, the Founders stayed committed to republicanism. We’ll examine their struggle to forge a new nation from the loosely knit alliance of states in the next chapter.

The war created a nation that grew into a world power by the dawn of the 20th century and, after numerous painful twists and turns, a multi-racial democracy after 1965. The United States waited until the global war’s conclusion then signed the aforementioned Treaty of Paris that allowed the British to retain the upper part of North America (Canada) but gave the U.S. the area below between the Atlantic and Mississippi River, except for Florida which stayed in Spain’s hands, along with what’s now the American Southwest. Prior to 1812, Spain’s claim to Florida was bigger than the current states’ panhandle borders. The U.S. took all of Florida in 1819 as part of the Adams-Onís Treaty, whereby the U.S. promised to never invade Spanish Texas. The British not only hung on to Canada, but also Jamaica, Gibraltar, and India, despite Ben Franklin spreading fake news in newspapers during treaty negotiations about how American Indians allied with the British presented King George III with bags of scalps from American women and children (Founders Online). For all their troubles — and one could argue that the American Revolution was won with the tonnage and firepower of the French Navy — France didn’t get much out of the war territorially, other than Britain returning (African) Senegal to France. Still, the oldest Western monarchy, France, had ironically seeded the world’s next big republic, the greatest since Classical Rome. But once the British realized that the U.S. wasn’t yet congealing into a strong unified state or maintaining a big military, they decided to stay in the forts they occupied in new American territory, defying the Paris Treaty. It would take a “second war for independence,” the War of 1812, to clear the path for Americans to settle the West.

Optional Viewing & Reading:

Explore the American Revolution (NEH)

Animated Map 18:44 (Battlefield Trust)

Diplomacy & the American Revolution, 1776-1783, State Department-Office of the Historian

Amy Crawford, “The Swamp Fox,” Smithsonian (June 2007)

Holger Hoock, “Mangled Bodies: Atrocity in the American Revolutionary War,” Past & Present (February 2016 ) > JSTOR

John McNeil, “How the Lowly Mosquito Helped America Gain Independence,” Smithsonian (June 2016)

Valley Forge Interpreters, “The General von Steuben Statue: Interpreting LGBTQ+ Histories of the Revolution,” National Park Service (n.d.)

Alice George, “The American Revolution Was Just One Battlefront In A Huge World War,” Smithsonian (June 2018)

B.J. Armstrong, “The American Revolution, Naval Power, and the 21st Century,” War on the Rocks (July 2021)