“We must remain hopeful that laws are not in fact like spider webs which catch only flies and gnats while the hornets and wasps sail through” — Pat Goines, History Professor Emeritus, 2022

You could think of this chapter’s topic, the Progressive Movement, as when Americans first argued seriously about drawing the lines between freedom and order in the modern, industrialized world. Today, it’s the main thing we argue about in politics when nothing dramatic is going on and, often, even then. What is the appropriate balance? What should the role of government be?

The easy answer — the one most likely to blurt out of our mouths after considering the question for five seconds instead of five minutes — is that we should have fewer laws and more freedom. That’s not necessarily a bad response, but it’s probably an issue best dealt with on an item-by-item basis, with an understanding that most rules result from somebody abusing the earlier lack of rule, at which point someone else (other citizens, not an imaginary tyrant) pressed the government to make the rule. Among other things, rules protect the environment, personal safety, privacy, and national security; and governments try at least to prevent monopolies, fraud, discrimination, pandemics, and terrorist attacks. If you don’t think yours does the job well enough, consider a career in public service and become part of the solution.

For people focused on freedom that haven’t experienced true societal chaos, it’s easy to forget that there are no “rights” in the first place without governments, only nature “red in tooth and claw.” Rights are a function of government. Medieval Europe, with small and weak governments, had homicide rates 20-30x higher than the modern U.S. or Europe. Governments are easy and unimaginative targets when disagreements about laws originate among ourselves. In most cases, evil men-in-black from an elitist, distant “deep state” bureaucracy don’t swoop into your town in an unmarked SUV with tinted windows and inflict the rule on a public uniformly opposed to it, though that can happen. Should drunks be able to drive through neighborhoods going 130 mph? Should prostitutes and drug dealers have the right to conduct business in front of your house, or kid’s school, or anywhere? If your answer is no to any of these questions, then you’re at least somewhat sympathetic to the notion of a regulatory state, even if you think of yourself as opposing big government and the phrase regulatory state nauseates you. We don’t live on the Serengeti anymore. You may not be in the same spot on the freedom-order spectrum as your more cautious or reckless neighbor, but neither are you fundamentally opposed. Nor is there a single spectrum to start with. Most people are libertarian in some ways and not in others.

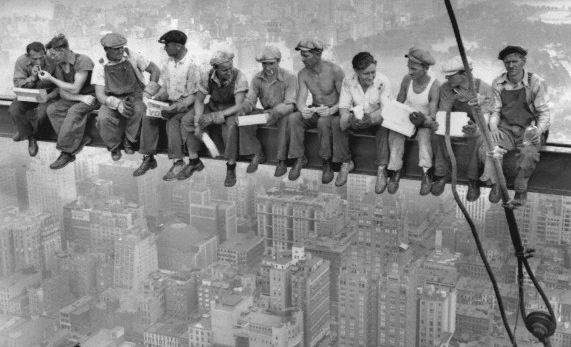

What about these workers taking a lunch break atop the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center? Is it uptight to suggest they should wear harnesses or just smart? Who is liable if a gust of wind comes along and blows them off the girder? The construction company? What about the people they might fall on below? Who would clean up the mess below if they fell? The sidewalk level businesses? The “authorities?” Does the government want them roped up against their will or do the workers want ropes their employers won’t pay for, so they appeal to the government via union voting to force the employers to provide them? In this case, there was nothing to worry about because the photo was staged. But the hypothetical question still stands: are those among us opposed to regulations willing to not sue if the falling worker lands on our relative, or will we look for someone to blame and demand accountability?

America is a litigious society in a way that cuts across political lines and the threat of lawsuits is part of what thickens those maddeningly thick rule-books. If you have a high GPA, study law; it will never go out of style. All of us want the benefits that accrue from protection, law, and order, and none of us want what the British call a “nanny state” crimping our style. Government — the unpopular adult in the room — is where accountability and regulation converge. As Constitutional author James Madison put it in the Federalist #63, “Liberty may be endangered by the abuses of liberty, as well as by the abuses of power.” Can we determine through voting, constructive debate, social media, and town hall meetings how we should conduct ourselves in a way everyone agrees on? Of course not. Are you insane? All we can do is compromise in ways that leave everyone a little unhappy. But if we take the time to consider how all this came about, people might aspire to a bit more civility toward each other as we stew in our collective unhappiness. You need look no further for that story than the Progressive Era, when the contours of our modern squabbles over freedom and order took shape.

Progressive Spirit

First, we should define what Progressivism means more precisely, but only a little more, because this term is hard to nail down. American history is littered with words that have different meanings depending on whether they’re written with a capital or lower-case letter (e.g. Enlightenment, Democratic, Republican, Reconstruction, Populism), and the same goes for progressive. In any era, progressives advocate for changes that they think would improve society, critiquing the status quo in more fundamental ways than those who put more stock in tradition or habit. Or, progressive can have an even more general meaning. For instance, when a CEO says “we need to keep our business progressive,” she just means staying ahead of the competition. But Progressive Era with a capital P refers to the era between roughly 1890 and 1920, give or take a few years and overlapping with the Gilded Age. Though people sometimes used the word at the time, most famously Teddy Roosevelt’s Progressive Party in the 1912 election, it’s more of an umbrella term used retroactively (after the fact) by historians to refer to movements that were all trying to improve American society. Reform meant many things to many people. While no one advocated “big government” (no one ever does), many people hoped for a better government and smarter policies that more fully served the people’s needs and, yes, that sometimes meant bigger.

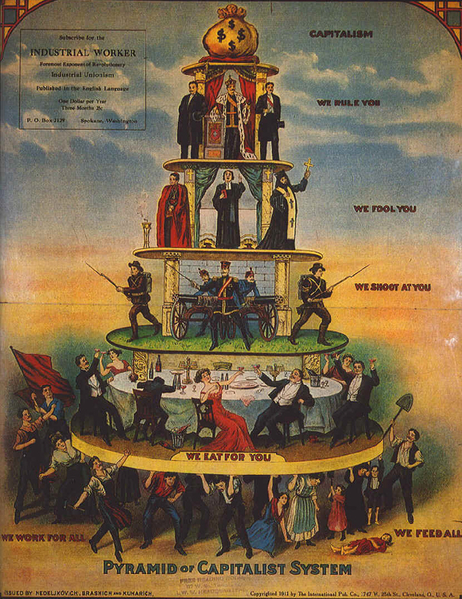

IWW Poster Based on Flyer of the “Union of Russian Socialists” Spread in 1900 and 1901, International Publishing Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1911

Progressives included some leftists or Populists that questioned capitalism fundamentally (as in the poster above), but also business leaders and conservatives trying to improve society, make things more efficient, or diffuse leftist radicals by compromising. This business angle is why historian David Greenberg called Progressivism “a term that back then connoted not today’s Whole Foods leftism but a drive for order, efficiency, pragmatism and professionalism.” One Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson, described Americans of that time as “in a temper to reconstruct economic society.” Progressives also tried to clean up the corrupt political machines we read about in Chapter 2 and, as we’ll see in the next chapter, Progressives reformed and improved local government at the municipal and state levels. We’ll also read more in the next chapter about how Republicans took the lead in spearheading sensible economic regulations. With a century’s worth of hindsight, we can see that Progressives shared an assumption that organizations, whether they be governments, companies, or advocacy groups, could change things for the better: safer, cleaner, healthier, more equitable, civilized, and efficient. Libertarians they weren’t.

Un-Progressive Progressives: Eugenics

Some progressive movements, including those we’ll examine in the next few sections, involved attempts to change society but not the sort of laws and regulations referenced in the chapter title. Progressivism’s disparate movements didn’t necessarily hold common values or see themselves as fighting for a common cause and many wouldn’t be seen as progressive today. For instance, the Ku Klux Klan endorsed alcohol prohibition, which was a Progressive reform movement, but they’re hardly a group that anyone then or now would consider forward-thinking. Historians looking to characterize the era’s “typical Progressive” will find no such animal, and some have even called for retiring the term Progressive Era altogether because it attempts to encompass too many contradictory movements, some now considered regressive, and it was weak relative to other eras on civil rights apart from the Suffragist movement.

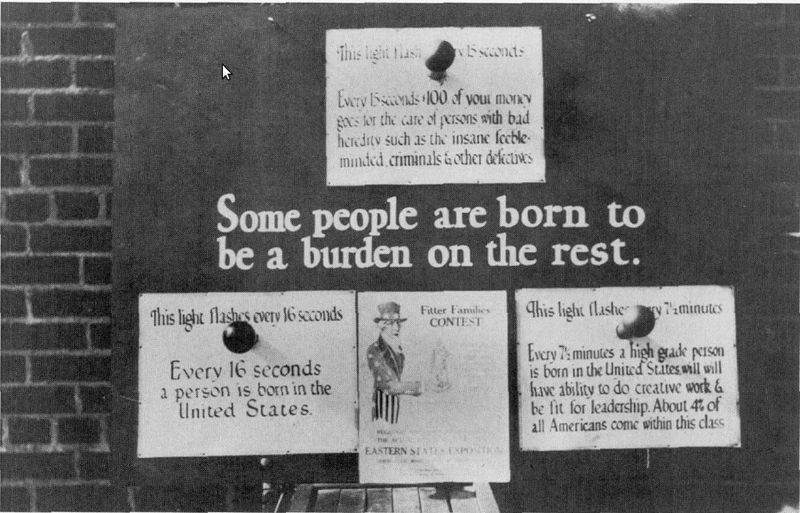

Eugenics Advocacy Poster from the Philadelphia Sesqui-Centennial Exhibition, 1926, American Philosophical Society

The era was more of a regressive era for minorities and included, for instance, one notoriously reactionary attempt to improve society: eugenics, the science of studying genetic differences on behalf of ethnic cleansing through selective breeding and sterilization. In the classic nature vs. nurture question as to why some people are more talented, successful, or better behaved than others, you could think of eugenicists on the far nature side of the debate. In eugenicists’ view, environment and circumstance have nothing to do with one’s fate, only your inherited gene pool. Based on a crude misunderstanding and outright misreading of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, they thought that society should take things a step further by ridding itself of inferior genetic stock — what Darwin would’ve called “unnatural selection” had he still been alive. Such biological racism predates publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859), tracing from the Classical era through the Enlightenment to French Aryan theorist Arthur de Gobineau, and Darwin was a harsh critic of early eugenics. English statistician/anthropologist Sir Francis Galton, Darwin’s half-cousin, coined the phrase eugenics (Greek root: good, or well) in 1883, fifty years before German Nazis applied similar notions on the extreme scale of ethnic cleansing. Galton, completely on the nature side of the debate, coined the dichotomous nature vs. nurture term. Early eugenicists didn’t believe in killing anybody for the most part, but rather limiting the reproductive rights of those they deemed inferior. Galton wasn’t a murderer, but he defined a good society as one where “the weak would find a welcome and a refuge in celibate monasteries or sisterhoods.”

Eugenics was mainstream enough in early 20th-century America that many county fairs had “fittest human stock” contests instead of normal beauty pageants, with doctors included on the judging panel. The fittest families got blue ribbons, just like the livestock they were showing, and had to submit detailed records of family traits and pedigree. A 1939 documentary about the future, New Roadways, features plastic surgery for prisoners, premised on the idea that not being handsome enough had prevented incarcerated males from making the requisite social connections for a functional existence. In the Progressive Era, leading American universities researched eugenics, funded by the Carnegie Institution and Rockefeller Foundation. Carnegie money even backed a 1911 report by the American Breeders Association that at least entertained the notion of euthanasia as one of several options to deal with undesirable people. They advocated the “humane” method of death by gas chamber (hydrogen cyanide chambers were invented in Nevada in 1924), but there’s no solid evidence that they carried through on the idea. At the very most, American euthanasia was very isolated and never widespread. Exact comparisons with Nazi Germany, therefore, constitute a false equivalent (see Rear Defogger #4 in menu above). Most American eugenicists didn’t support euthanasia or eugenicide (extermination); they just thought that people who had problems or were different than them shouldn’t be allowed to have children. John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie were joined in this chorus by phone inventor Alexander Graham Bell (Chapter 1) and John Harvey Kellogg, a holistic physician who ran a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan and co-invented Corn Flakes® along with his brother, Will. Of course, in the long run, selective breeding would have the same exterminating impact on a targeted population as eugenicide. In 1927, the Supreme Court backed Virginia sterilization laws in Buck v. Bell, with Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes arguing that sterilization was more humane than executions or the future starvation of those too imbecilic to care for themselves.

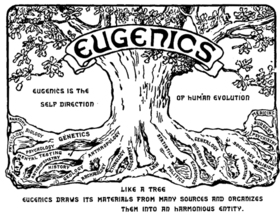

Logo From Second International Eugenics Conference, 1921, Celebrating Its Interdisciplinary Foundations

Who was “unfit?” In California that included groupings as subjective as “bad girls,” but eugenicists’ ultimate goal was to rid the U.S. of criminals, the infirm, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, Jews, Eastern Europeans, and poor “hill country” Whites. Keep in mind that eugenics never actually happened in America on a large scale — otherwise most of us wouldn’t be around — but it did happen in certain pockets of the country. The Carnegie Institute established a facility at Cold Springs Harbor, New York with millions of index cards where they hoped to catalog the entire American population in preparation for the removal of whole peoples and bloodlines, or “family trunks.” Their leading intellectual beacon was Stanford University President David Starr Jordan, author of Blood of the Nation: Study in the Decay of Nations by Survival of the Unfit (1902). The U.S. Army War College conducted a 1925 study that determined Blacks could never serve ably in combat due to inferiority and cowardice. One influential figure was Army doctor Paul Popenoe, author of Applied Eugenics (1918), who started Ladies’ Home Journal and was a founding practitioner of marriage counseling.

Eugenic policy took many forms, including outlawing interracial marriage in half the states, but also included over 60k coerced sterilizations of “unfit” men and women by the 1930s. Most states have since issued formal apologies to victims’ family members. Native American women were subject to involuntary sterilization up until 1970. California still sterilized some female prisoners as late as 2010 and has since offered apologies and compensation (see optional articles below). While the United States never systematically implemented eugenics on a large scale, it influenced racist immigration reform passed in the 1920s (Chapter 7); and it helped inspire more extreme, genocidal applications in Nazi Germany, explored in more detail in the optional section of Chapter 10.

As Mark Twain likely didn’t say but might have: “history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes.” Eugenics will be another example when, shorn of its racist origins, it echoes in the transhumanism that endorses genetically improving humans. The technology is already there, so we’ll be wrestling with ethical dilemmas about genetics into the foreseeable future.

Birth Control & Family Planning

Like marriage counseling, birth control’s history overlaps with the eugenics movement, though in both instances they eventually shed any association with it. Likewise, the history of sex advice books is entangled with eugenics. Negative eugenics was the sort described in the section above, discouraging reproduction, but positive eugenics encouraged the “fit” of the preferred gene pool to reproduce with how-to manuals. Genetics itself has some overlap with eugenics, though that scientific field originated on its own. In none of these cases should one’s opinion on the subject have any more do with their roots than wearing cotton does with slavery or driving a Volkswagen has to do with Nazi Germany.

The figure most associated with birth control, Margaret (Higgins) Sanger, is a case in point. As an obstetrical nurse, she took on the 1873 Comstock Law that interpreted birth control and information about birth control as lewd and indecent. Sanger, whose mother had 18 pregnancies in 22 years, founded the American Birth Control League in 1921 — forerunner to Planned Parenthood — promoted sex education and crusaded to both avoid abortions and make abortions safer than the illegal “back alley” operations involving turpentine and knitting needles. Sanger’s reputation suffers from her association with eugenics. John D. Rockefeller was an anonymous donor on Sanger’s behalf and she indeed encouraged the poor to have fewer kids. She wrote that “we need not more of the fit, but fewer of the unfit. The propagation of the degenerate, the imbecile, the feeble-minded, should be prevented.” The masthead of Sanger’s Birth Control Review (1917-1928) read “Birth Control: To Create a Race of Thoroughbreds.” She even gave a lecture on birth control to the Women’s Auxiliary of the KKK, which she enjoyed but said she had to use childlike terminology to make them understand. For Sanger, embracing eugenics was possibly a tactical move to reach a broader audience than those interested in, or supportive of, contraception. Or, like many historical figures, maybe Sanger just held a constellation of views that later seem like a contradictory combination of progressive and regressive (e.g.’s John Muir, Teddy Roosevelt, Che Guevera, most people that have ever lived). History is full of shifting baselines, which is why contemporary people also won’t pass muster with future generations if their goal is to scour us for imperfections.

But Sanger’s motives were more complex than racist eugenicists. One of her most infamous letters, to eugenicist Clarence Gamble of Procter & Gamble, is a good example of how misleading it can be to take quotations out of context. Sanger’s critics on the left and right have seized upon the passage that includes “We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population,” indicating that Sanger was conspiring to exterminate African Americans. However, the full passage reads: “We do not want word to go out that we want to exterminate the Negro population and the [black] minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to any of their more rebellious members.” The full quote sheds an entirely different light on the passage, indicating that Sanger is worried that people will misunderstand her cause as promoting the extermination of African Americans, which is why she wants black spokesmen to clarify that’s not the case. The reason she didn’t want the extermination idea to get out, in other words, was because it was false. She was advocating birth control and family planning among impoverished people, not extermination. One wonders about the various agendas, other than sloppy research, motivating historians to omit the rest of the sentence.

By the mid-1930s, Sanger convinced the mainstream medical community, including the AMA, to accept birth control as a legitimate part of family planning that patients didn’t have to withhold from their doctors. However, it came under attack from some circles again starting in the 1970s, especially because of Planned Parenthood’s association with counseling abortion as the last line of defense against unwanted pregnancies. And, in 2020, Planned Parenthood of Greater New York removed Sanger’s name from its NYC Health Center because of her support for eugenics. While Sanger’s eugenic beliefs, including what she wrote in The Pivot of Civilization (1922), partially motivated her promotion of birth control, her legacy shouldn’t be reduced to that. Many pundits and judges have implied that, if Sanger endorsed eugenics and started Planned Parenthood then, conversely, people who now support Planned Parenthood or are pro-choice must support eugenics, as suggested extensively in the 2022 Dobbs v Jackson case that overturned 1973’s Roe v. Wade (Dobbs Brief PDF). Obviously, that’s not the case, regardless of the merits of abortions. Today’s culture wars over abortion and public funding of Planned Parenthood are the subtexts of renewed interest in Margaret Sanger. Meanwhile, the organization has posted a statement on their site denouncing Sanger’s involvement with eugenics, saying that she was so intent on her mission of birth control that she aligned herself with ideologies and organizations that were explicitly ableist and white supremacist.

Capitalism & Christianity

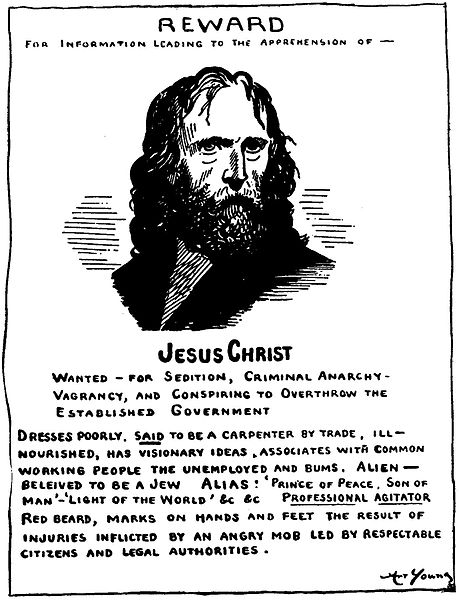

Most historians understand Progressivism as society’s collective reaction to the dramatic changes of industrialization and urbanization. One concrete accomplishment for labor during the Progressive Era was strengthened unions, through which many workers won the right to 40-hour workweeks (+ OT) and safer conditions than those described in the first two chapters. A related angle is to see it as the reconciliation of two American pillars: the moral impulse of Christianity and the ruthlessness of no-holds-barred industrial capitalism. No one definition fits perfectly, including this, since some Progressives weren’t Christians, capitalism wasn’t uniformly ruthless, and progressive issues transcended the economy. But the bottom-line amorality of unfettered free markets conflicted with the Social Gospel of helping others then prominent among both Protestants and Catholics, and Progressives helped reconcile capitalism with Christianity. The drawing below, appearing in the pro-labor magazine The Masses, draws on that tension between commoners and free markets, suggesting that modern capitalist societies would view Jesus as an outlaw because of his advocacy for the poor. Less inflammatory, the era’s churches provided charities and built hospitals and schools, furthering efforts they’d started centuries earlier.

Sometimes, historians and textbook writers need a common theme in which to toss a bunch of topics that don’t otherwise fit into more thematically unified chapters, like World War I. The Progressive Era fits that everything-but-the-kitchen-sink bill for the period between 1890-1920. A final way to understand the Progressive Era would be to look it up on Wikipedia and you should feel free, but not required, to consult that and other sources to augment these definitions. The late 19th and early 20th centuries obviously weren’t the first time in human history that conflicts over rules and laws occurred to anybody, but industrialization, urbanization, and population growth magnified those conflicts.

Tackling poverty and poor working conditions, for instance, was a primary agenda of some Progressive reformers. Chicagoan Jane Addams built Hull House to feed and educate poor children, arguing that the environment of poverty, not inherently or genetically bad character, triggered a cycle of social problems. Addams, in other words, was on the opposite end of the spectrum in the nature vs. nurture argument from eugenicists, on the side of nurture. Likewise, Dr. Alice Hamilton studied typhoid and the effects of factories on workers, arguing that working and living conditions impact one’s health. Working conditions were a good example of how different Progressives worked at cross-purposes. As we’ll see below, some focused on worker efficiency and speeding up assembly lines, while others focused on safety and ameliorating unhealthy or unsanitary conditions and chemical exposures that could cause long-term diseases or short-term conditions like phossy jaw, caused by overexposure to phosphorus.

The idea that your employer owes you a safe working environment, something most of us today take for granted as a reasonable expectation, was born in the Progressive Era. It’s safe to say that the vast majority of today’s libertarians probably wouldn’t be okay with being seriously injured at work because their employer was too cheap or lazy to take proper precautions. It’s a good illustration of how the regulatory impulse is much easier to oppose after one’s protected by regulations. A true bona fide libertarian, on the other hand, supports laws against violent crime and defending property, but doesn’t mind breathing smog, mercury-filled lakes and streams, getting fired just before his pension kicks in, being discriminated against because someone doesn’t like where his ancestors are from, and putting out his own house fire with a garden hose as his kid buys crack at the corner mart. Who amongst us fits that bill?

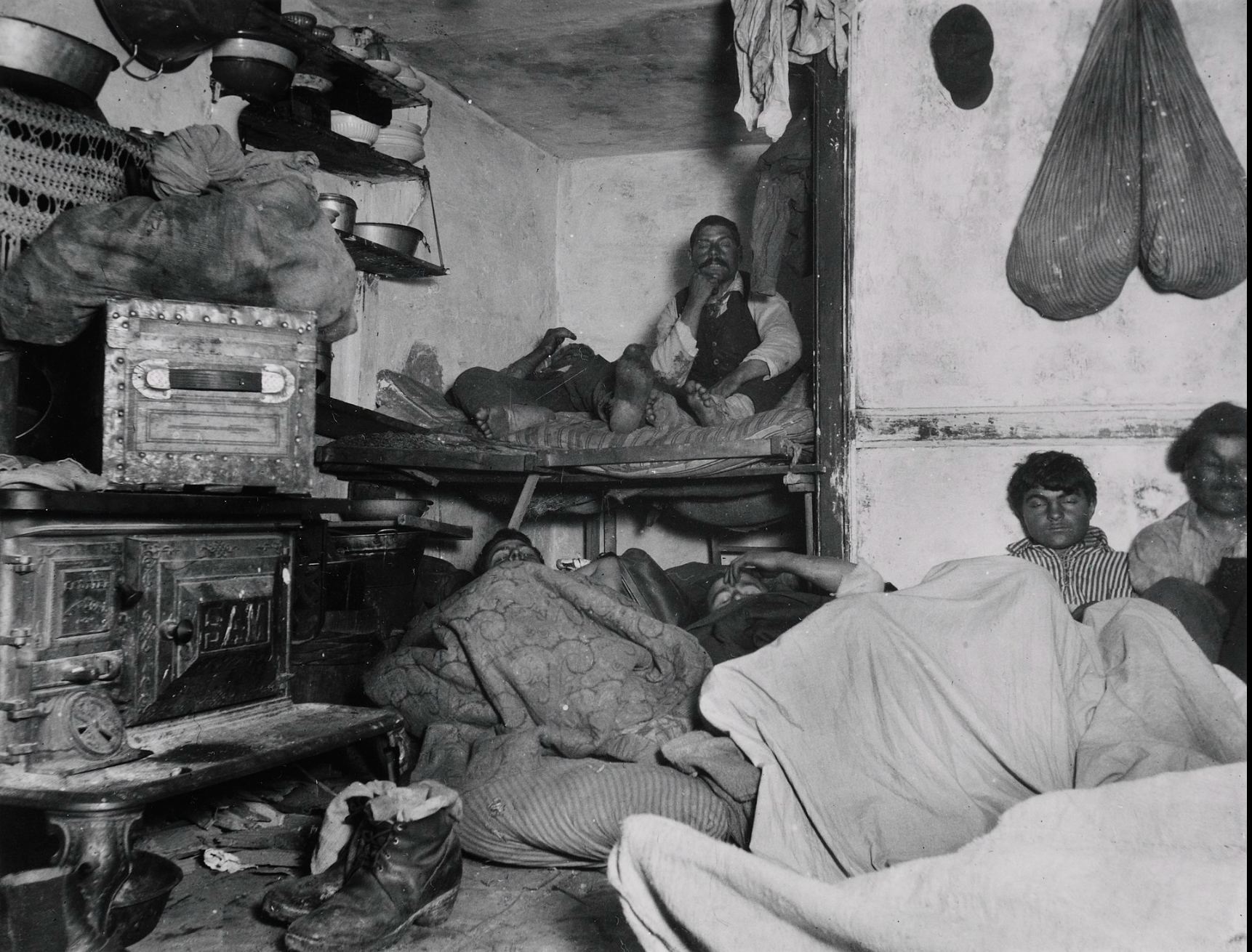

The Progressive Era was when politicians hammered out many of these regulations and people from across the spectrum became more aware of problems around them. Muckraking journalists, so named because they “raked up the muck,” drew the public’s attention to corporate malfeasance, as with Ida Tarbell’s investigation into Standard Oil Trust in McClure’s Magazine. Nellie Bly faked insanity to go undercover in a women’s asylum, reporting on the abusive staff there. Bly worked for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World at the time, a paper known more to history for its sensationalized Yellow Journalism but that also engaged in investigative journalism on behalf of poor and oppressed Americans. Pulitzer, a Jewish Hungarian immigrant, was, among other things, a muckraker. That accounted for his popularity among the working classes, along with his sensationalism. He got in trouble with Teddy Roosevelt for questioning the Panamanian Revolution that enabled the namesake canal’s construction (previous chapter). Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine informed people about squalid living and working conditions through photography. Riis, taking advantage of the recent invention of magnesium flash powder to light otherwise dim rooms (above), triggered progressive legislation that cleaned up tenements with publication of his photo book How the Other Half Lives (1890). Lincoln Steffens drew the public’s attention to the corruption of urban political machines in The Shame of the Cities (1904). McClure’s published Steffens and Tarbell’s investigations in serial form, spread out over successive issues. Later, we’ll discuss Upton Sinclair, the man President Teddy Roosevelt had in mind when he coined the term muckraker.

Suffragist Movement

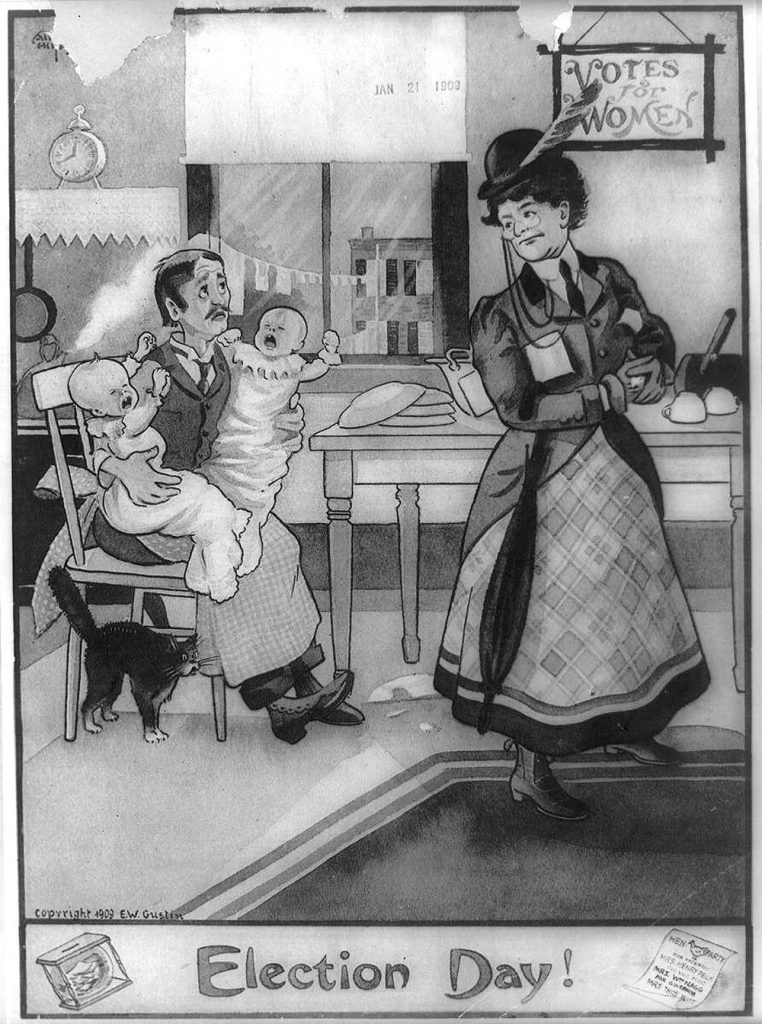

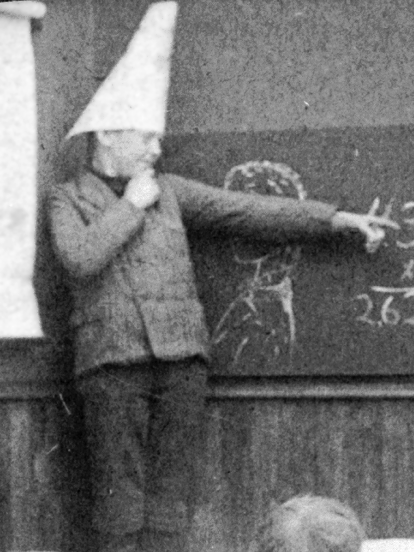

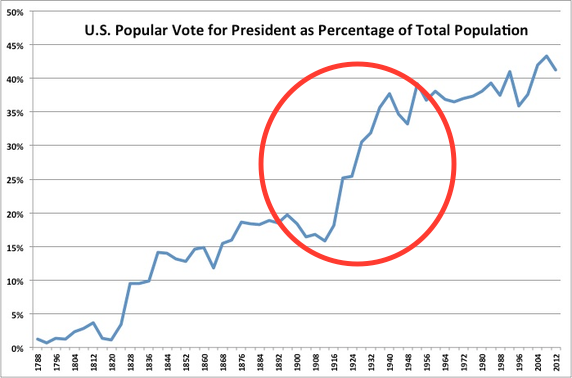

Expanding democracy and agitating for social justice were parts of Progressivism as well, though an obvious blind spot of most Progressives was race. Progressives, by and large, failed to reinforce the early Civil Rights movement. Other than a handful of forward thinkers like the co-founders of NAACP, the era’s white reformers did less to fight discrimination than those of the mid-19th or mid-20th centuries. But the Suffragist movement that launched in the 1840s culminated in the Nineteenth Amendment of 1920 prohibiting voting restrictions based on sex. You’ll sometimes hear the phrase suffragette, instead, but that term was coined by opponents to belittle their efforts. From the outset, the Suffragists’ concern for voting merged with other feminist concerns about access to equal-paying jobs, marital and property laws, etc. As of the 1840s, married women, especially, had no legal standing whatsoever, with all their property and money absorbed into that of their husbands. Many people, including some women adhering to traditional codes of patriarchy, felt that women didn’t belong in the public sphere and some even thought it lowered their prestige to enter into the corrupt world of business and politics. Unsurprisingly, in 1905, former president Grover Cleveland (D) said, “Sensible and responsible women don’t want to vote.” A bit more surprisingly, his wife Frances agreed. In fact, when President Woodrow Wilson was considering whether or not to back a national law giving all American women the right to vote, his desk was deluged with letters from female anti-suffragists, with one pleading to “leave us a little longer in the quiet of our homes, to rear our children well and care for our husbands with undivided interest.” The slippery-slope fear was that women who chose to be housewives would lose that right. As indicated by this 1909 poster, other opponents of women’s suffrage held to the same zero-sum fallacy that hindered the civil rights movement: in this case, that men and women would be forced to switch places. Some opponents thought suffragists were insane or that wanting to vote meant they wanted to “be men.”

Just as many women opposed suffrage, many men supported it. If they hadn’t, the laws never would’ve changed because women couldn’t vote to grant themselves the vote if they didn’t have it yet (conversely, once the U.S. granted property-less white men, women, and minorities the franchise it was too late to go back unless that group voted to disenfranchise themselves). But opposition came from many fronts. When Thomas Edison tried showing short suffragist videos before movies, audiences booed, either because they didn’t support the cause or thought the activists weren’t pretty enough to be on screen. Meanwhile the textile and alcohol industries opposed the movement because they feared that voting women would organize unions or support prohibition, respectively. The women’s movement also coincided with a broader anti-suffrage movement caused by concern over Catholic and Jewish immigration from the wrong parts of Europe. In the Gilded Age, the whole trajectory of American voting rights could’ve gone in the opposite direction toward less democracy, but it didn’t.

Prior to the 19th Amendment, women could vote in some states but not others. Rural western states pioneered female suffrage, with the Wyoming territory becoming the first place on Earth to allow it in 1869. Western lawmakers hoped to attract more women because their populations were mostly male. There were women in power like Utah Senator Martha Hughes Cannon and Montana congresswomen Jeanette Rankin before most American women could even vote. Cannon was a polygamist wife and advocated polygamous marriage. In 1896 she defeated her own husband in the senate race, but later exiled in Europe to avoid testifying against him after polygamy was outlawed.

Suffragists excelled at organization and pageantry, dressing well and marching in parades. In a big 1913 parade through Washington, D.C., organizer Alice Paul symbolically put a woman on a white horse at the front of the march ahead of the “Great Demand” float. Cavalry had to escort the marchers as counter-protesters pelted the women with snowballs, rocks, and lit cigarettes. Over 100 women were hospitalized. Still, they garnered so much attention that when Woodrow Wilson showed up at the nearby train station for his upcoming presidential inauguration, journalists weren’t there. Smaller pilgrimages from around the eastern half of the country fed into this 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession, that divided women by profession to accentuate their economic roles.

Paul, the daughter of Quaker parents, picked up where earlier 19th-century leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) and Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) left off and led the final, successful push for women’s suffrage. Some people assume that agitating requires wearing menacing masks, hating “the man” (or men, as it were, in this case), throwing bricks, or acting obnoxious, but that’s usually counter-productive. Suffragists protested with aplomb and a sense of flair. They didn’t hate men, they knew what they wanted, and they knew they were right.

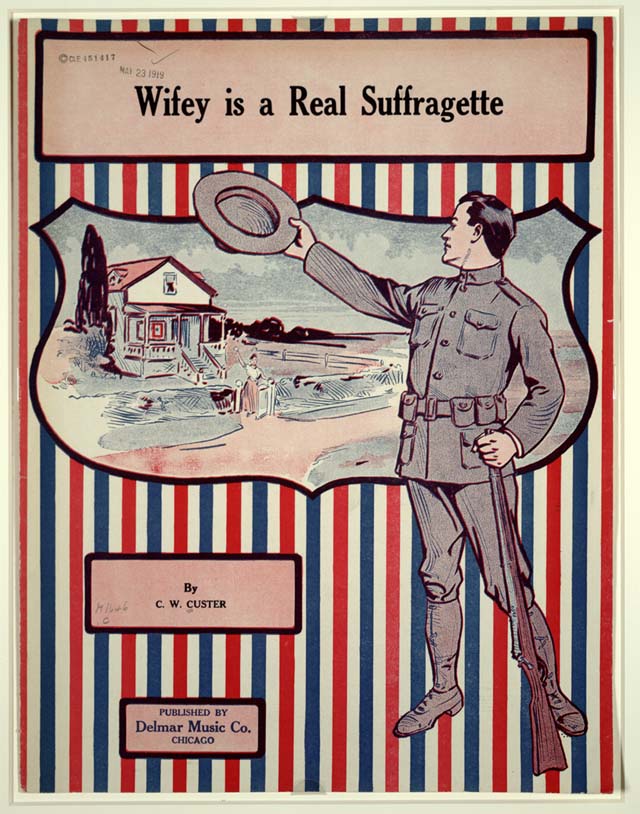

Sheet Music For An Anti-Suffragette Song Arguing That Women Shouldn’t Be Worrying About Themselves While The Country Is At War, 1919, Library of Congress

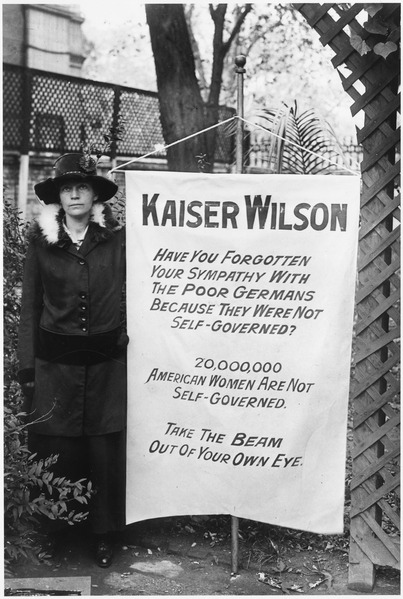

As President Wilson argued for U.S. involvement in World War I to promote democracy, “Silent Sentinel” Suffragists picketing in front of the White House pointed to the obvious hypocrisy of denying women the vote. Wilson had voted for suffrage in a New Jersey referendum, but the native Virginian opposed a national law on the grounds of states’ rights. Some onlookers didn’t approve and pelted the picketers with tomatoes and eggs. Critics can always argue against reform when the country is at war because it’s a distraction (right), but reformers can likewise ask why those same critics bother themselves with opposition to reform when the country is at war. Either way, domestic history never comes to a halt when the U.S. is at war and usually even accelerates. Wilson had the women arrested for obstructing traffic, but when wardens force-fed them in prison (Occoquan Workhouse) to stop their hunger strikes, public sentiment swung in their favor. Wardens force-fed prisoners with a mixture of eggs and milk through their nasal passages rather than mouths. A similar thing happened in Britain, where Alice Paul had also gone on a hunger strike. English martyr Emily Davison fatally threw herself in front of King George V’s horse to rally supporters (optional video). British women over 21 of all economic classes gained the vote in 1928, but their suffragist movement was more violent than the American version. World War I also caused more American women to work in industry to replace soldiers, further weakening the already weak argument that they shouldn’t vote because they weren’t active in the economy.

Congress and enough hold-out states capitulated and the Nineteenth Amendment became law in 1920, the largest single expansion of democracy in American history. Women have outvoted men in every presidential election since 1964. While presidents don’t have a formal role in passing amendments, their support can make or break the process, as seen by Abraham Lincoln’s tireless campaigning for the Thirteenth abolishing slavery. Wilson came around to the Suffragists’ view by 1918 and supported the Nineteenth after being cajoled by his activist daughter Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre (left), who later supported his idea of a League of Nations (Chapter 6). With over 20k women serving stateside and abroad in the Navy and Marines and more working in factories, Wilson said, “We have made partners of women in this war. Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Like Lincoln’s views on slavery and Barack Obama’s on same-sex marriage, Wilson’s views on suffrage evolved while he was in office. Regressive on civil rights toward African Americans and, at times, German-Americans, Wilson sounded like he leapt forward a century in a time capsule when saying, in 19A’s context, “we should show democracy as all-inclusive.”

Congress and enough hold-out states capitulated and the Nineteenth Amendment became law in 1920, the largest single expansion of democracy in American history. Women have outvoted men in every presidential election since 1964. While presidents don’t have a formal role in passing amendments, their support can make or break the process, as seen by Abraham Lincoln’s tireless campaigning for the Thirteenth abolishing slavery. Wilson came around to the Suffragists’ view by 1918 and supported the Nineteenth after being cajoled by his activist daughter Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre (left), who later supported his idea of a League of Nations (Chapter 6). With over 20k women serving stateside and abroad in the Navy and Marines and more working in factories, Wilson said, “We have made partners of women in this war. Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Like Lincoln’s views on slavery and Barack Obama’s on same-sex marriage, Wilson’s views on suffrage evolved while he was in office. Regressive on civil rights toward African Americans and, at times, German-Americans, Wilson sounded like he leapt forward a century in a time capsule when saying, in 19A’s context, “we should show democracy as all-inclusive.”

The Nineteenth Amendment, in theory, gave all American women the right to vote, which at the time realistically meant white women. The Fifteenth Amendment (1870) granting black men the right to vote had been divisive within the movement because some Suffragists supported it, arguing that it was an important step toward democracy, while others resisted because it put black men ahead of white women. In the 19th century, African-American abolitionists Frederick Douglas and Sojourner Truth supported women’s suffrage. Progressive-era Suffragists included civil rights leaders like Ida B. Wells (left), who helped launch the NAACP and crusaded against vigilante lynching and fellow NAACP charter member Mary Church Terrell (right), the country’s first black female college graduate (Oberlin). For a five-minute video on Wells, see the optionals at the bottom of the chapter. During California’s suffragist referendum (before the 19th Amendment), Latinas in Los Angeles, Chinese in San Francisco, and African-American women in Oakland all participated along with Whites. Wells participated in the 1913 parade through Washington but Paul sent her to the back along with other minorities.

The Nineteenth Amendment, in theory, gave all American women the right to vote, which at the time realistically meant white women. The Fifteenth Amendment (1870) granting black men the right to vote had been divisive within the movement because some Suffragists supported it, arguing that it was an important step toward democracy, while others resisted because it put black men ahead of white women. In the 19th century, African-American abolitionists Frederick Douglas and Sojourner Truth supported women’s suffrage. Progressive-era Suffragists included civil rights leaders like Ida B. Wells (left), who helped launch the NAACP and crusaded against vigilante lynching and fellow NAACP charter member Mary Church Terrell (right), the country’s first black female college graduate (Oberlin). For a five-minute video on Wells, see the optionals at the bottom of the chapter. During California’s suffragist referendum (before the 19th Amendment), Latinas in Los Angeles, Chinese in San Francisco, and African-American women in Oakland all participated along with Whites. Wells participated in the 1913 parade through Washington but Paul sent her to the back along with other minorities.

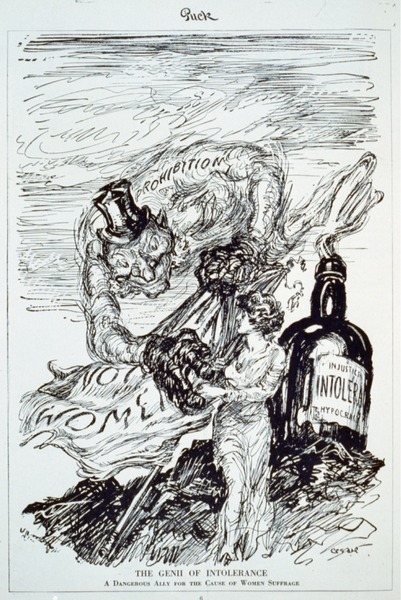

Progressive-era white Suffragists, like their 19th-century predecessors, were divided on race. Some racists supported women’s suffrage hoping to double the white vote (if black women couldn’t) while “dry” racists hoped that women would help outlaw alcohol. Suffragist and temperance reformer Frances Willard, paradoxically the daughter of abolitionists, said, “better whiskey and more of it is the rallying cry of the great, dark-faced mobs.” Susan B. Anthony had lobbied for temperance and the prohibitionist wing of women’s suffrage was international. Willard’s Women’s Christian Temperance Union was active in Canada, Newfoundland, India, Sweden, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia. Temperance, women’s suffrage, and civil rights were a complicated trio of issues, leading to strange bedfellows and opponents.

Finally, Suffragists made another seemingly small contribution to American democracy that’s now more important than ever. A common refrain in our current environment of hyper-partisanship and fragmented media is that voters lack objective information. But the League of Women Voters (1920) issues bipartisan pamphlets (or online PDFs) before every election, with versions tailored for any location, available in English and Spanish. They maintain objectivity by letting candidates submit their own responses to common questions. That way voters aren’t filtering information through biased media and negative TV ads. Here’s a sample of their Voters Guide for readers interested in candidates and referendums along with information on registration and polling locations. It’s not perfect; it’s just more perfect than anything else.

Finally, Suffragists made another seemingly small contribution to American democracy that’s now more important than ever. A common refrain in our current environment of hyper-partisanship and fragmented media is that voters lack objective information. But the League of Women Voters (1920) issues bipartisan pamphlets (or online PDFs) before every election, with versions tailored for any location, available in English and Spanish. They maintain objectivity by letting candidates submit their own responses to common questions. That way voters aren’t filtering information through biased media and negative TV ads. Here’s a sample of their Voters Guide for readers interested in candidates and referendums along with information on registration and polling locations. It’s not perfect; it’s just more perfect than anything else.

The Regulatory State

Progressivism also dealt with more mundane but practical issues. When New York City firemen were called to the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, their hoses didn’t fit on Baltimore’s hydrants. That compelled the National Institute of Standards (then Bureau) to standardize hose couplings and galvanized their general push to standardize gauges, fasteners, prong plugs, window sizes, etc. Any sane person would agree that standardized fittings make life easier. Today we take it for granted, or at least cross our fingers, that the things we buy at stores will fit on/in our homes, engines, or gadgets. The borehole for a door knob, for instance, is often 2 ⅛”. This push for efficiency was one part of the Progressive Era that lasted into the 1920s rather than dying out around World War I. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover brought together hundreds of industries in the ’20’s including aviation, automobiles, and electronics. They honed measurements and even came up with an agreed-upon bread loaf size. We’ve all heard of horsepower and, if we take the time to think, are aware that it dates to an age when horses did much of our work. But who gets to decide what one unit of mechanical hp(I) actually is? James Watt had the original idea for hp units, but the ultimate arbiters are institutions like the standards bureau. Would you prefer to leave a subjective guesstimate up to each car salesman? Hoover exported a lot of these standards through trade agreements by the Bureau’s foreign division. This is one example of business and government working in tandem as standardization improved efficiency in accounting, shipping/distribution, and retail commerce.

Fireworks are a better example of Progressivism pushing into a marginal area that a reasonable libertarian might prefer that the government stay out of. As more and more kids injured themselves on the Fourth of July, overwhelming emergency rooms, the government stepped in to regulate fireworks, outlawing the types that were blowing their hands off. By 1900, more kids were injured annually on July 4th than the total number of casualties in the Revolutionary War they were celebrating. It is a trivial but symbolic example of the quandary posed by the Progressive spirit: should we take measures that make sense on a collective scale if it means compromising our individual freedoms? Should you have the right to fracture your skull wrecking a bicycle or fly through your car windshield, or does society have the right to force you to wear a helmet or seatbelt if that danger raises everyone’s insurance rates?

1906 Pure Food & Drug Act

In a true laissez-faire system, meatpackers can kill you with spoiled meat and it’s your problem. The same goes for prescription medications. The free market will motivate your surviving relatives and friends to buy meat or pills elsewhere. In a regulated system, the producers and pharmacists are forced to sell you unspoiled meat and labeled government-tested medication. Food and drug control were the first big federal government intrusions into the free market after railroad regulations.

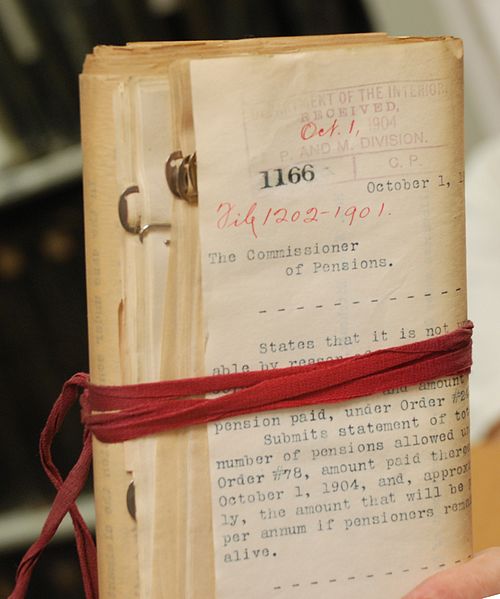

The 1906 Pure Food & Drug Act was the culmination of a group effort involving crusaders, muckraking journalists, a president, and industry lobbyists that weren’t selling shady products. Crusaders Alice Lakey and Harvey W. Wiley had led the Pure Food Movement dating back to the late 19th century. Lakey spearheaded the PFM by lecturing, lobbying, and writing on the dangers of chemical preservatives in food and milk. Wiley did likewise and, in 1902, took things a step further from his post at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Wiley called for volunteers to take part in a study the media dubbed the “Poison Squad.” Unlike most government guinea pigs, that tended to be minorities (e.g. Tuskegee syphilis experiment) or military (nuclear weapons testing), the Poison Squad was mostly enthusiastic young college lads eager to cash in on the promise of $5/month plus free room and board and to demonstrate their robust constitutions. Their motto was “Only the Brave dare eat the fare.” However, their “board” was food laced with formaldehyde (pork), salicylic acid (canned fruit), borax (country ham), and copper sulfate and alum in a host of other items. The control subjects got this normal food straight off the grocery shelves, whereas others got uncontaminated food that the USDA struggled to track down straight from farms because organic food was so rare. Wiley initially thought that he’d prove these chemical preservatives should be limited, but his subjects’ declining digestive health convinced him that they should be banned altogether. Wiley later served as commissioner of the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and worked in the chemical lab at Good Housekeeping magazine.

For Progressives, Wiley and Lakey were heroes; but for libertarians, their influence set a bad precedent insofar as it extended the government’s role all the way into Americans’ bodies. Use of the worst chemical preservatives, including formaldehyde, fell out of favor in the free market because of news about the Poison Squad and they weren’t included in the Pure Food & Drug Act that passed in 1906, but the research that brought their toxicity to light was government-funded. Lakey, meanwhile, influenced state laws mandating that fresh milk be undiluted with water. The federal Pure Food & Drug Act (1906) focused more on meat and medicine labeling.

President Teddy Roosevelt supported reform in the meat industry, and when meatpackers resisted government inspections he threatened to release the results of an investigation that included graphic details. They backed down. Many large companies supported reform as they needed to comply with European regulations to export anyway. Regulation came about partly because of Lakey and Wiley’s groundwork, partly because of spoiled canned meat that killed soldiers in the Spanish-American War (the same brands sold to consumers), partly because big packers supported regulations they knew their smaller competitors couldn’t keep up with, and partly because Upton Sinclair’s muckraking novel The Jungle (1906) revealed details that Roosevelt had threatened to release.

President Teddy Roosevelt supported reform in the meat industry, and when meatpackers resisted government inspections he threatened to release the results of an investigation that included graphic details. They backed down. Many large companies supported reform as they needed to comply with European regulations to export anyway. Regulation came about partly because of Lakey and Wiley’s groundwork, partly because of spoiled canned meat that killed soldiers in the Spanish-American War (the same brands sold to consumers), partly because big packers supported regulations they knew their smaller competitors couldn’t keep up with, and partly because Upton Sinclair’s muckraking novel The Jungle (1906) revealed details that Roosevelt had threatened to release.

The author had worked undercover in a Chicago meatpacking plant. It wasn’t pretty. He described how they shoveled dead rats into sausage-grinding machines, how filth and guts were swept off the floor and packaged as “potted ham,” and how diseased cows were slaughtered for beef. Some workers were so frozen that their ears broke off when they rubbed them. Sinclair intended the book as a critique of capitalism itself, but readers were mainly just grossed out by the graphic, if somewhat fictionalized, depictions of slaughterhouses. Sinclair wrote of his audience that he had “aimed for heads, and hit them in the stomach.” Teddy Roosevelt didn’t like the socialist polemic toward the novel’s end, despite his own leftist leanings, but he sent a team to Chicago to investigate. They covered up their most lurid findings, but their report nonetheless helped spur change.

That same year, 1906, the U.S. passed the Pure Food & Drug Act that regulates meat production and drug labeling and created the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), though today the Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulates meat via the FSIS while the FDA handles other foods, and started requiring food labels in 1990. The FSIS limits but does not eliminate pathogens like E. coli and salmonella. Food regulation wasn’t simply a case where consumers wanted the laws and producers didn’t. Producers that were careful about selling healthier goods, like H.J. Heinz of Pittsburgh, lobbied on the law’s behalf because they knew it favored clean businesses and/or larger businesses. Profit margins don’t shrink if you’re already sweeping rat droppings into the trash. Likewise, E.R. Squibb, founder of today’s pharmaceutical giant Bristol-Meyers Squibb, was influential in ensuring that medicine included standardized dosages and ingredients in its packaging. Regulation also tends to reinforce the status quo, as big companies can not only afford complying but also have enough political pull to help craft it, which is likely what Big Tech will do with artificial intelligence.

We’re stuck in an ongoing regulatory balancing act that can’t please everyone. Today, the multi-billion dollar dietary supplement industry isn’t regulated by the FDA and most of its products are worthless or placebos, with some harmful. Over 75% don’t even contain the basic ingredients advertised, let alone provide evidence that those ingredients work. Some undoubtedly work, but even their reputations suffer because of the many that don’t. Yet, consumers get frustrated with too much regulation. One problem is that regulations accrete over time, each one well-intended but together comprising a growing binder that’s overwhelming to small businesses, especially, that can’t afford a legal team. People can’t follow rules when the rulebook is over a thousand pages.

When these rules hit a tipping point, either in government or within large companies or institutions, the process and paperwork is known as red tape or regulatory creep. If you read a headline that says “Red Tape Holds Up Bridge,” you can trust the engineering (it’s not actually held up by tape), but it might take a while to build. Red tape drives people crazy because there are so many rules and regulations to keep up with. Bureaucratic bloat is a related term, referring not so much to the growth of rules but to the endless expansion of departments and committees within institutions. Of course, complaints about red tape provide an excellent cover for those that want to grow profits by retracting sensible regulations that really protect people. Con artists that sell placebos as herbal supplements no doubt oppose adding “red tape.” As these gray areas are negotiated and hammered out, regulators get familiar with the regulated. FDA medical officer Curtis Wright got a cushy job with Purdue Pharma in 1996, one year after overseeing a positive review of OxyContin® that helped spur the modern opioid crisis. After the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, it came out that regulators from the former Minerals Management Service partied with oil company executives. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) corruption on Wall Street is notorious. The crudest form of such corruption is bribery, but more common yet is regulatory capture, when regulators start making concessions to the very people they’re policing because they start to identify and socialize with them. Regulators and regulatees merge as people switch careers back and forth between the revolving door of industry, lobbying, and government. Regulatory delegation is another problem. When Boeing designed and tested its 737 MAX in the 2010’s, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) farmed out its oversight of the plane’s MCAS stabilizing software to delegates on Boeing’s payroll, who left MCAS out of pilot manuals so as to avoid the cost of having to re-train them in flight simulators, even though Boeing’s test pilot crashed in his own simulation. Combined with faulty angle-of-attack sensors on their planes’ noses, to which the software responded by forcing nosedives, two passenger jets crashed in Indonesia and Ethiopia in 2018-19, killing 346 passengers and crew. The 2017 repeal by the Trump administration of Obama-era safety guidelines for transporting hazardous chemicals was seemingly another case of deregulation contributing to an accident, the Norfolk Southern’s 2023 derailment near East Palestine, Ohio. But that train wasn’t carrying enough hazardous materials to have fallen under the Obama law (FactCheck.org).

When these rules hit a tipping point, either in government or within large companies or institutions, the process and paperwork is known as red tape or regulatory creep. If you read a headline that says “Red Tape Holds Up Bridge,” you can trust the engineering (it’s not actually held up by tape), but it might take a while to build. Red tape drives people crazy because there are so many rules and regulations to keep up with. Bureaucratic bloat is a related term, referring not so much to the growth of rules but to the endless expansion of departments and committees within institutions. Of course, complaints about red tape provide an excellent cover for those that want to grow profits by retracting sensible regulations that really protect people. Con artists that sell placebos as herbal supplements no doubt oppose adding “red tape.” As these gray areas are negotiated and hammered out, regulators get familiar with the regulated. FDA medical officer Curtis Wright got a cushy job with Purdue Pharma in 1996, one year after overseeing a positive review of OxyContin® that helped spur the modern opioid crisis. After the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, it came out that regulators from the former Minerals Management Service partied with oil company executives. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) corruption on Wall Street is notorious. The crudest form of such corruption is bribery, but more common yet is regulatory capture, when regulators start making concessions to the very people they’re policing because they start to identify and socialize with them. Regulators and regulatees merge as people switch careers back and forth between the revolving door of industry, lobbying, and government. Regulatory delegation is another problem. When Boeing designed and tested its 737 MAX in the 2010’s, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) farmed out its oversight of the plane’s MCAS stabilizing software to delegates on Boeing’s payroll, who left MCAS out of pilot manuals so as to avoid the cost of having to re-train them in flight simulators, even though Boeing’s test pilot crashed in his own simulation. Combined with faulty angle-of-attack sensors on their planes’ noses, to which the software responded by forcing nosedives, two passenger jets crashed in Indonesia and Ethiopia in 2018-19, killing 346 passengers and crew. The 2017 repeal by the Trump administration of Obama-era safety guidelines for transporting hazardous chemicals was seemingly another case of deregulation contributing to an accident, the Norfolk Southern’s 2023 derailment near East Palestine, Ohio. But that train wasn’t carrying enough hazardous materials to have fallen under the Obama law (FactCheck.org).

After Enron, Tyco, and WorldCom plundered their employees and investors with “creative accounting” in the late 1990s, there was an understandable push for stricter regulations. But now when you pay tuition, you’re paying more so that your school can stay in compliance with Sarbanes-Oxley (2002, aka “Sarbox”), including risk management and internal auditing. That, of course, requires more staff, as does compliance with human resource codes, financial aid requirements, accreditation, internal safety, treatment of Veterans, athletic eligibility, etc. Ironically, California can’t build a high-speed rail that would be a net gain for the environment because of too many environmental regulations. Each thick rulebook has a reason because we all want accountability, but you can see how bureaucracy begins to “bloat.” We even need more bureaucracy to watch over the ones watching over others because they, too, need to be accountable (e.g., internal affairs within large police departments). Former President Ronald Reagan was right when he called bureaus the “nearest thing to eternal life we’ll ever see on this earth.” But when Reagan said that “government can’t solve the problem; government is the problem,” he was too easily overlooking that crime wouldn’t disappear if we just got rid of police. In other words, the ultimate blame doesn’t go to the government, but rather the corrupt accountants, deadbeat borrowers, racist HR departments, shortcutting companies, etc. who bequeathed to us layers of regulation because of their greed. We wouldn’t need government to be the unpopular adult in the room if we didn’t have bratty kids.

A lot of red tape is at the local level, where there seems to be less anti-government push back. Tried building a house lately? Inspectors demand dozens of highly detailed specifications, driving builders, homeowners, and contractors nuts. City laws overlap and contradict neighborhood covenants, leading to lawsuits, delays, and even bankruptcies. On the other hand, American homes don’t burn down and blow over as easily as those in most countries. Shouldn’t your neighbor have the right to throw rusty old refrigerators in his front ditch? It’s his property and, after all, this is the land of freedom. True, but if his junk is unsightly and driving down your real estate value, then… You can see the train of thought. Given the economic impact of a neighbor’s unsightly property, we’re willing to deny him the most basic freedoms through Homeowner’s Associations (HOA’s). A “man’s home is his castle” as far as protection, but you can’t paint your castle the wrong color, or plant a tree in the wrong place, or make any alterations whatsoever that aren’t in your neighbor’s favorite agreed-upon castle style. We love the regulations we think we hate so much that we even get together and make up extra ones with our neighbors when the government isn’t involved.

We’re nuts for nitpicky regulations in public, too. As you’re standing there celebrating freedom on the 4th of July, make sure to not stand in the wrong place for too long. We have laws against loitering. The U.S. leads the world in loitering regulations. Don’t blame the government; the politicians themselves wouldn’t mind revoking them. Why would they care? But who among us freedom-lovers wants people we think look weird or don’t like to be able to just stand wherever they want breathing oxygen? Having a criminal gang loitering on the sidewalk or on a certain street corner could destroy almost any small business, scaring away customers.

Yet walking away from the spot you’re not supposed to stand in can also be problematic. A 2015 Department of Justice Investigation found the police in Ferguson, Missouri had been arresting Blacks for a crime they called “manner of roadside walking” (i.e. sagging jeans?). Laws against standing or walking are a convenient excuse to crack down on gangs, prostitutes, and bums when they’re not actually in the act of doing anything otherwise illegal or, in the Ferguson case, for straight racial profiling of innocent people to raise revenue through fines. Our real dream is our own freedom to do as we choose combined with the freedom from being around other people exercising freedoms we don’t like. No government on Earth could provide what any one person sees as just the right mixture.

Drugs & Alcohol

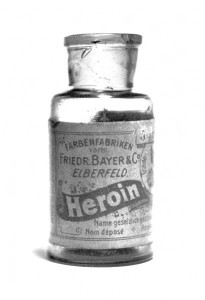

The 1906 Pure Food & Drug Act law also forced pharmacies to label medications. All drugs, pharmaceutical or recreational, were legal in America as of the mid-19th century. Cocaine was used as a local anesthetic and Coca-Cola® included trace amounts of the cocaine precursor ecgonine. As we saw in the previous chapter, Bayer marketed heroin for children’s colds. But opium abuse reached problematic levels among the upper-middle classes in the late 19th century. The 1914 Harrison Act banned over-the-counter sales of narcotics, limiting their use to doctor-authorized prescriptions. This law included opiates and cocaine but excluded cannabis (marijuana), which had been on earlier failed measures (the Mann Bill and Foster Bill) and remained subject to state and municipal control until 1937. The Harrison Act was the first attempt to transfer responsibility to the national government, though many states restricted drugs and poisons in the late 19th century. In general, broadening our view to include state laws pushes back our timeframe for the Progressive Era. Like the Pure Food & Drug Act (which dealt with products crossing state lines), the Harrison Act was arguably unconstitutional. Under the 10th Amendment, rights not enumerated (granted) to the national government in the Constitution’s text revert to state police authority. Still, the Supreme Court backed the Harrison Act in U.S. v. Doremus and Webb v. U.S. (1919). The Commerce Clause is the constitutional toehold for such laws, giving the national government authority over commerce crossing interstate lines.

The 1906 Pure Food & Drug Act law also forced pharmacies to label medications. All drugs, pharmaceutical or recreational, were legal in America as of the mid-19th century. Cocaine was used as a local anesthetic and Coca-Cola® included trace amounts of the cocaine precursor ecgonine. As we saw in the previous chapter, Bayer marketed heroin for children’s colds. But opium abuse reached problematic levels among the upper-middle classes in the late 19th century. The 1914 Harrison Act banned over-the-counter sales of narcotics, limiting their use to doctor-authorized prescriptions. This law included opiates and cocaine but excluded cannabis (marijuana), which had been on earlier failed measures (the Mann Bill and Foster Bill) and remained subject to state and municipal control until 1937. The Harrison Act was the first attempt to transfer responsibility to the national government, though many states restricted drugs and poisons in the late 19th century. In general, broadening our view to include state laws pushes back our timeframe for the Progressive Era. Like the Pure Food & Drug Act (which dealt with products crossing state lines), the Harrison Act was arguably unconstitutional. Under the 10th Amendment, rights not enumerated (granted) to the national government in the Constitution’s text revert to state police authority. Still, the Supreme Court backed the Harrison Act in U.S. v. Doremus and Webb v. U.S. (1919). The Commerce Clause is the constitutional toehold for such laws, giving the national government authority over commerce crossing interstate lines.

It was the same with railroad legislation in the 1880s and the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, though in all three cases the products in question didn’t always cross state lines. Cultural factors also influenced narcotics regulation. For instance, anti-marijuana laws were used to deport Mexicans from the Southwest (added to the list in 1937, when jobs were scarce), and anti-cocaine propaganda warned of black musicians using the drug to seduce white women. However unhealthy or addictive these drugs were in their own right — and local marijuana laws weren’t limited to the Southwest — their legal status was often as enmeshed in politics as it was their chemical properties. Despite racial stereotypes promoted by Federal Bureau of Narcotics Commissioner Harry Anslinger in his infamous 1930s “reefer madness” campaign, many Mexicans also feared that marijuana caused madness and violence and Mexico banned the drug two decades prior to the United States. In the U.S. today, marijuana is still classified as a Schedule 1 drug by the national government even as several states have legalized small amounts for recreational use, as was briefly the case in ten states in the 1970s. There’s also a bipartisan trend toward legalizing medicinal marijuana.

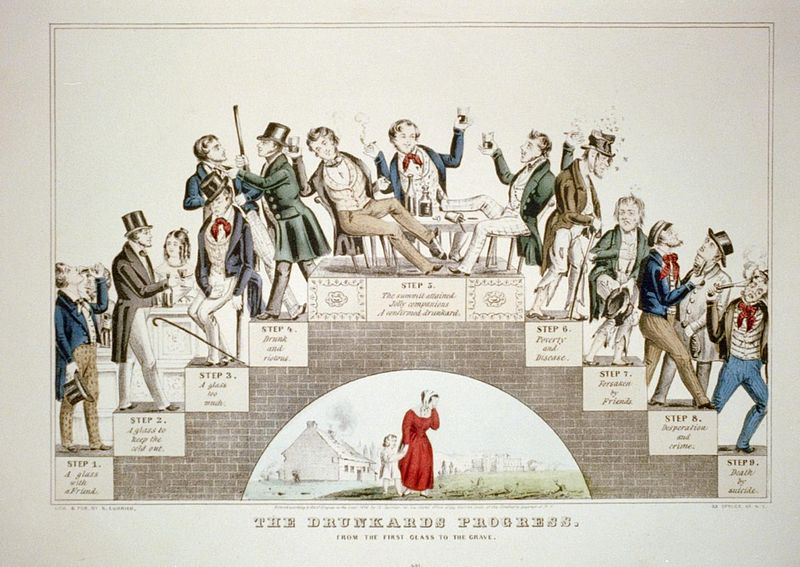

“The Genii of Intolerance – A Dangerous Ally for the Cause of Women Suffrage,” by Oscar Edward Cesare, Puck Magazine, September 1915

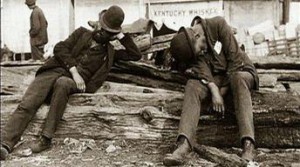

Alcohol wasn’t included in the Harrison Act. Like women’s voting, liquor laws varied from state-to-state and county-to-county (and still do), creating a patchwork of dry and wet laws. Open Option Laws from the 1850s allowed for dry sub-divisions within wet counties but not vice-versa. In the 19th century, the temperance movement took aim at a variety of social problems including poverty, laziness, and domestic abuse — the idea being that banning booze could eradicate all these problems in one fell swoop. The issue was tangled in the suffragist movement because drinkers and their suppliers feared that, if women won the right to vote, they’d push through prohibition. And, like that movement, it was connected to the Industrial Revolution. Alcohol didn’t mix well with machinery and lowered productivity, and industrialization contributed to the mass production and distribution of alcohol, lowering its price. All these critiques of alcohol date to the 19th century, but sufficient momentum built to outlaw alcohol in the early 20th century. More Americans were driving cars and trucks by the 1910s and people quickly discovered that drinking and driving don’t mix. Then, when the anti-Catholic movement picked up among WASPs (white Anglo-Saxon Protestants), tee-totaling took a cultural turn as the temperance movement tied alcohol abuse to Catholic immigrants. Finally, fighting World War I in the 1917-18 against heavy-drinking Germany pushed temperance over the top. You could now fight poverty, laziness, domestic abuse, low productivity, drunk driving, Catholicism, and Kaiser Wilhelm II all at once simply by banning alcohol. Progressive reformers viewed Prohibition as a panacea, or remedy for all ills, albeit a kinder and friendlier version than eugenics.

There were powerful business interests at work, too. Hollywood studios thought that people would be more likely to attend movies if drinking wasn’t an option, and Coca-Cola supported an alcohol ban for an obvious reason. Desperate brewers, meanwhile, tried to convince the government to only ban hard alcohol but, by World War I, it was too late and many brewers were German anyway (e.g., Miller, Pabst, Schlitz, Busch) at a time when the U.S. was fighting Germany. In an unusual cross-cultural alliance, German brewers even paid poll taxes for Hispanics and Blacks in Texas so that they could vote, banking that they’d support alcohol. This all-or-nothing approach to alcohol emerged during the 19th-century Market Revolution when Americans tended to cluster into an early culture war of tipplers versus teetotalers, with less space for moderate beer and wine drinkers than elsewhere and more or less all of the tippler faction male. To this day, the U.S. has higher-than-global averages of both people that abuse alcohol and abstain altogether.

The Volstead Act and 18th Amendment outlawed the production and sale of liquor, except for religious sacraments, home-brewing, and doctor’s prescriptions. Canada legalized liquor the very same week, recognizing an opportunity when they saw one. All the borders fought uphill battles trying to keep out bootleggers and many drinkers made their own bathtub gin, or “moonshine.” Alcohol’s black market drove crime rates sky-high and corrupted police departments in the process, as we’ll unpack in Chapter 7 on the 1920s. President Franklin Roosevelt revoked the Volstead Act in 1933 and the 21st Amendment undid the 18th.

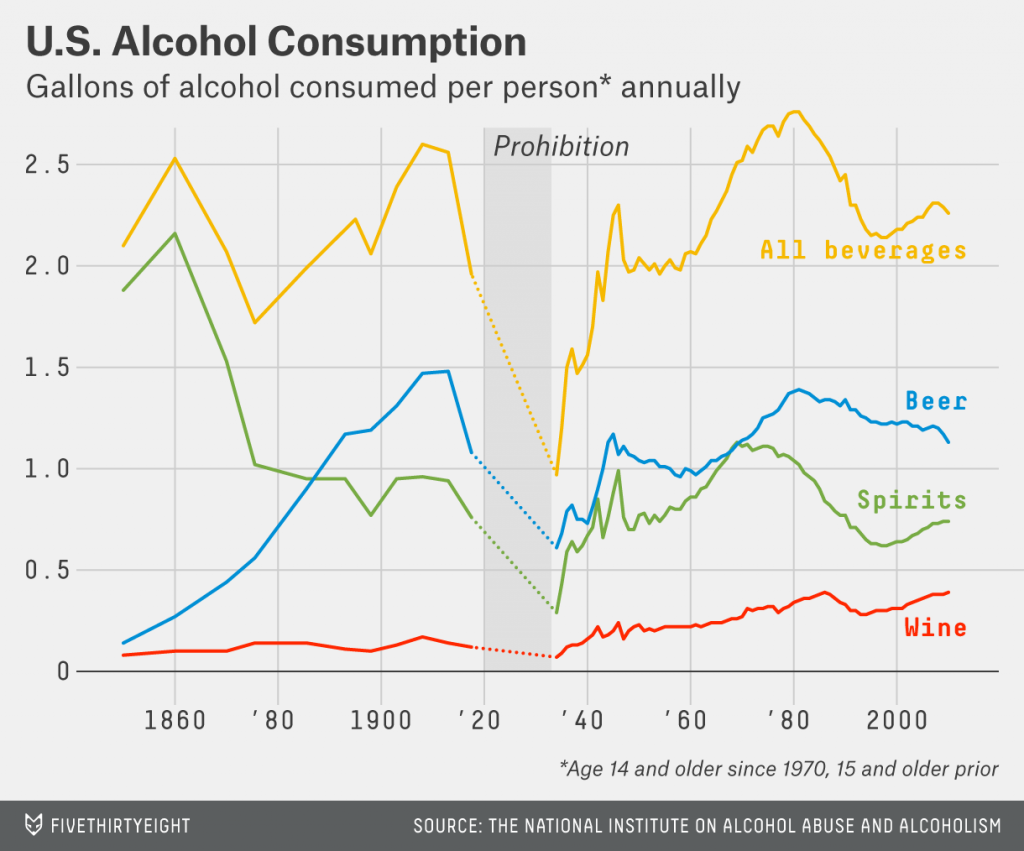

Certainly, Prohibition failed if its goal was to eliminate alcohol from society altogether, but that’s not a fair standard. It’s easy for us to forget how pervasive and damaging liquor was before Prohibition. The temperance movement was not as merely reactionary as we remember it, nor local. At least 23 other countries likewise tried to ban alcohol around the same time. The Klan might have supported Prohibition but, so too, did civil rights leaders like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, like Frederick Douglass before them, while others saw the liquor interests as pure, predatory capitalists. Mahatma Gandhi advocated prohibition in India, where many states today disallow alcohol, along with entire Muslim countries in the Middle East. Drinking did indeed worsen domestic abuse, poverty, and laziness, and we need to be wary of a shifting baseline here because American men drank more hard alcohol than today (see Rear Defogger #22). Some historians estimate that, before the Industrial Revolution, drinking rates were at least 3x higher than today, despite a recent uptick in the 21st century, when numbers rose steadily every year from 2000 to 2020. Alcohol consumption declined ~ 20% at first with Prohibition and liver cirrhosis declined along with it. Even by 1935, two years after Prohibition’s repeal, per capita intake was less than half of what it had been earlier in the century. It’s hard for historians to judge Prohibition’s impact on drinking because it overlaps with the advent of driving, movies, World War I, and a recession in 1921. Historians never have the luxury of controlled experiments. It’s possible we drink less hard alcohol (aka liquor, spirits, or booze) today because we have more to distract us and need to drive more. And it’s also questionable whether we should gauge the usefulness of laws on whether they entirely eliminate a problem, a common thread of argument. We haven’t eliminated murder, but no one is suggesting that we legalize it. Is it not the case that we’ve at least reduced homicides by outlawing them? Would reimposing the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (1994-2004) eliminate mass shootings? No, but that’s the wrong question.

Certainly, Prohibition failed if its goal was to eliminate alcohol from society altogether, but that’s not a fair standard. It’s easy for us to forget how pervasive and damaging liquor was before Prohibition. The temperance movement was not as merely reactionary as we remember it, nor local. At least 23 other countries likewise tried to ban alcohol around the same time. The Klan might have supported Prohibition but, so too, did civil rights leaders like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, like Frederick Douglass before them, while others saw the liquor interests as pure, predatory capitalists. Mahatma Gandhi advocated prohibition in India, where many states today disallow alcohol, along with entire Muslim countries in the Middle East. Drinking did indeed worsen domestic abuse, poverty, and laziness, and we need to be wary of a shifting baseline here because American men drank more hard alcohol than today (see Rear Defogger #22). Some historians estimate that, before the Industrial Revolution, drinking rates were at least 3x higher than today, despite a recent uptick in the 21st century, when numbers rose steadily every year from 2000 to 2020. Alcohol consumption declined ~ 20% at first with Prohibition and liver cirrhosis declined along with it. Even by 1935, two years after Prohibition’s repeal, per capita intake was less than half of what it had been earlier in the century. It’s hard for historians to judge Prohibition’s impact on drinking because it overlaps with the advent of driving, movies, World War I, and a recession in 1921. Historians never have the luxury of controlled experiments. It’s possible we drink less hard alcohol (aka liquor, spirits, or booze) today because we have more to distract us and need to drive more. And it’s also questionable whether we should gauge the usefulness of laws on whether they entirely eliminate a problem, a common thread of argument. We haven’t eliminated murder, but no one is suggesting that we legalize it. Is it not the case that we’ve at least reduced homicides by outlawing them? Would reimposing the Federal Assault Weapons Ban (1994-2004) eliminate mass shootings? No, but that’s the wrong question.

Another questionable interpretation is the idea that Prohibition’s failure proved it’s “impossible to legislate morality.” Obviously, hundreds of laws deal with morality rather than mere property rights — like murder and rape, for instance. Wasn’t the ban on slavery after 1865 an example of legislating morality? Be wary of drawing broad conclusions or principles from individual cases. First, ask yourself if the principle applies to other cases. Even if we narrow the conversation to chemical substances, the statement is problematic. When drinkers argue that “drugs” are immoral, isn’t that an example of their morals being shaped by the law? If so, it proves that we can legislate morality.

Maybe a clearer lesson to draw from Prohibition is that any law, regardless of its moral status, is difficult to enforce and counter-productive if a critical mass of the population dislikes and/or defies it. During Prohibition, even some of the same congressmen who passed the Volstead Act to please their voters had a secret stash in the House chambers. At some point, society has to weigh the downside of repealing the law versus the loss of life, effort, jail space, and cost put into outlawing it (tax expenditure and loss of potential tax revenue). Such logic compelled some states to legalize recreational marijuana after 2012. In Prohibition’s case, sympathetic juries often refused to convict bootleggers. Another lesson from Prohibition is that you can’t outlaw something unless taxpayers are willing to put the resources into enforcing it. In Prohibition’s case, neither the national government nor local or state agencies ever took charge of enforcement, each hoping to push costs off on the other. At one point, the entire state of New York had around 1500 people enforcing the alcohol ban. Most nights, there were city blocks in Manhattan with more people than that getting blottoed.

Mann Act

The government went after prostitution around the same time as drinking. Sometimes law enforcement refers to prostitution as vice (as in vice squad) but that term also has a broader meaning, referring to any immoral behavior. The federal Mann Act that outlawed prostitution, debauchery, and moving women across state lines for “immoral purposes” subsumed a patchwork of local laws. Legislators relying on Interstate Commerce stretched the definition of interstate during the Progressive Era and, in this case, the meaning of immorality. This so-called “white slavery law” was ostensibly aimed at sex trafficking, but its ambiguous language allowed authorities to prevent Jewish and black men from traveling with Gentile/white wives or girlfriends between states, or even in cars that could potentially travel between states given enough gas in their tanks. Originally, though, the white referred not to race but rather the victims’ innocence and purity. At its best, the Mann Act helped curb, and still helps curb, sex trafficking (a combination of kidnapping, slavery, and prostitution). At its most absurd, it was basically a law against black men being with white women, allowing profiling police to break out the billy club for whatever encounters they deemed immoral. Several states had already outlawed miscegenation, including any inter-racial marriage. But the Mann Act was versatile and could be used by Feds to go after whoever they deemed unfit. In 1924, the Mann Act brought down Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard Edward Young Clarke. Later, rock-and-roll pioneer Chuck Berry and politician Matt Gaetz (R-FL) were suspected of violating the Mann Act.

What about regular prostitution? The world’s oldest profession raises the same questions as other Progressive legislation as to whether it should be regulated to start with and, if so, whether it should be regulated at the state or national level (today, Nevada is the only state with legalized prostitution). One could argue that prostitution between consenting adults doesn’t harm anyone else and, therefore, isn’t the government’s business. That would meet the utilitarian test of moderate libertarianism insofar as the behavior in question arguably doesn’t harm others. On the other hand, prostitution commonly involves abuse, drug addiction, and the spread of communicable diseases (STDs), and can overlap with human trafficking (i.e. kidnapping and slavery). If you set legalities aside, the bottom line is that most Americans don’t care that much about what consenting adults do behind closed doors, but neither do they want prostitutes in front of their businesses, homes, or schools. Having laws on the books allow police to look the other way in some contexts and enforce in others. That has utility but also opens up the possibility of double standards and profiling.

The Mann Act’s racial overtones coincided with the rise of heavyweight fighter Jack Johnson. The African American wasn’t just pummeling white fighters; he drove convertibles down the road in a fur coat with white girlfriends and wives. Johnson was what was known in the era’s common parlance as uppity, or proud. His behavior earned him the condemnation of conservative black civil rights leader Booker T. Washington and Whites. After he married a second white woman (the first committed suicide), two southern ministers suggested that he be lynched. The only explanation some Whites could fathom for their marriage was that he’d abducted her somehow or another, leading to the Mann Act’s “white slavery” double meaning. Around this time, boxing was banned from movie theaters and bouts were limited to 15 rounds (gloves were already widespread in the late 19th century).

Self-Regulation in Sports & Movies

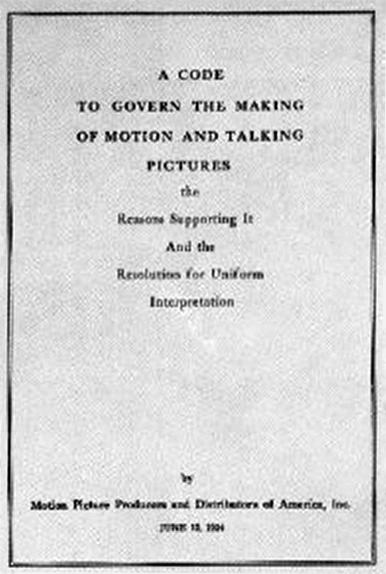

Progressive reforms impacted most forms of entertainment in one way or another. Sometimes industries take the initiative of regulating themselves before the government steps in. Texas power providers, ~ 85% private retailers since 2002, set up their own group called ERCOT to manage the state’s grid, for instance. Preemptive self-regulation is a wise move because it allows an industry to better control terms. Facebook®, for example, disallowed pornography and violence from the outset and, later, filtered inflammatory and fake news — the flames of which its own algorithm helps fan — but, so far, the government hasn’t stepped in to regulate speech on social media. Consequently, debates over censorship on Facebook® and Twitter® don’t concern the First Amendment, since they’re private companies.