“A man wrote me and said: ‘You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.’ If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost.” — Ronald Reagan (R), January 1989

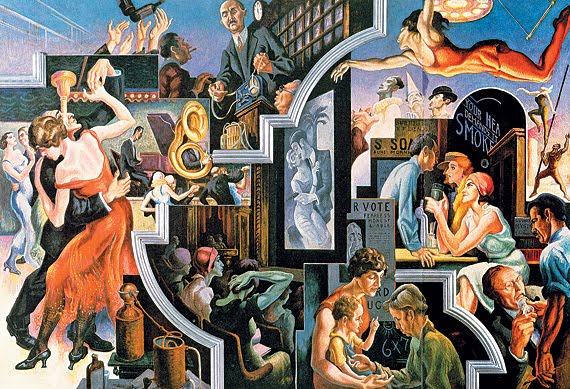

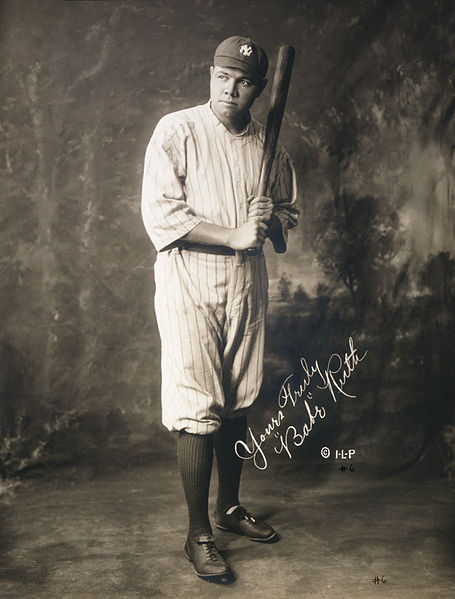

When we think of the 1920s, many of us have an image of grainy black-and-white film showing Flappers doing the Charleston on a skyscraper beam or plane wing to a soundtrack of Dixieland jazz. Flappers were fashionable young women who eschewed bulky petticoats and heavy skirts for a lighter style, shorter “bobbed” hair, tight felt hats, and (per their name) galoshes that flapped if left unbuckled. If you’re a sports fan, maybe the image is Babe Ruth knocking a home run out of Yankee Stadium. Either way, the decade’s overriding image is frivolity and exuberance, often fueled by illegal alcohol (though hopefully, that didn’t apply to the skyscraper dancers or to most of Ruth’s 714 home runs). Everyone in the 1920s seems to enjoy being filmed unless the cops are dumping out their booze bottles.

These images aren’t wrong, but they’re woefully insufficient. The Twenties is the first decade to come along where we need to be on guard against superficial impressions. We’ve all seen shows or commercials that condense entire decades down to iconic images: the sailor kissing his girl in Times Square when WWII ended in 1945, hippies twirling in the park or Apollo missions in the ’60s, depressing gas lines or disco balls in the ’70s, etc. These iconic clichés obscure any era’s underlying complexity and often only represent the experiences of a handful. I had dozens of relatives alive in the 1960s. To the best of my knowledge, none twirled in a park in a tie-dye shirt and I know for sure that none walked on the moon.

We’ll dig beneath the surface of the 1920s and look at social conflict, immigration, politics, and industry alongside the mass entertainment in those old films and on radios that’s dominated popular culture ever since. We’ll conclude by analyzing how alcohol Prohibition backfired and created the Mafia.

Nativism

Modern Americans are familiar with controversies over immigration. The U.S. has always been a land of newcomers but its people go through waves of relative hospitality and xenophobia, or fear of outsiders. The Order of the Star-Spangled Banner (also known as the American Party and, later, the “Know-Nothings”) were a major force against Catholic immigration in the 1850s, though they’ve faded into the background of our historical memory because their cause was eclipsed by the sectional crisis preceding the Civil War and they folded into the GOP. In economic boom times, Mexican workers were welcomed but then deported in recessions like the 1930s. The 1920s came on the heels of over half a century of increasing immigration by Catholics, Jews, and southern and eastern Europeans who didn’t fit the mold of “native stock” WASPs (short for white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants). WASPs and other Americans from northern and western Europe didn’t consider the newcomers real Americans. The phrase WASP can refer more narrowly to the wealthy, East Coast, privately-educated Anglo-Americans who ran American business, politics, and diplomacy.

There’s a scene in the movie Petrified Forest (1936) in which somebody compares 1930s gangsters with Old West outlaws. The grandfather says that they’re different because “gangsters aren’t American.” He doesn’t say real American the way some people thought of Barack Obama, as sort of a tweener; he left out that qualifier and just said, “not American.” That was typical of how many “Native Americans” looked at even 2nd or 3rd-generation Italian-Americans, assuming that described the gangster in question. The WASPs had seen enough by the 1920s and dug in to retain their hold on American identity. It was partly due to World War I, that exposed soldiers to French ways and triggered a threatening Bolshevik revolution in Russia. That overlapped with tension at home between rural, more slow-paced, traditional America and the fast-growing cities. Cities were seen as repositories of all that was dangerous and alien to white Protestant farmers: immigrants, factories, moral promiscuity, and new ideas. WWI just widened the spigot of threats.

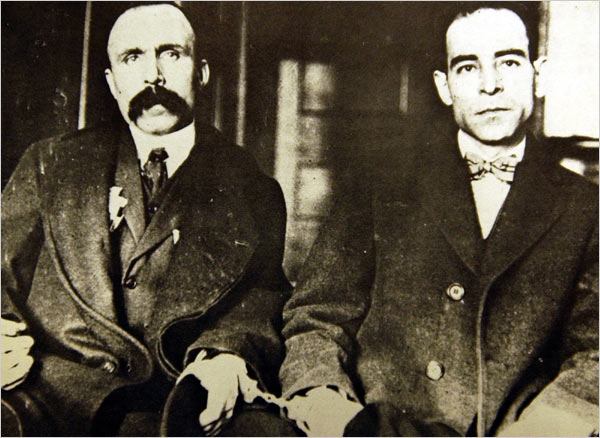

In the previous chapter, we saw how America’s First Red Scare (1919-20) stoked fear of Italian and Russian immigrants. In 1920, immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti stood accused of murdering a guard and paymaster in a shoe factory robbery in Braintree, Massachusetts, sealing WASP’ier Americans’ convictions that they were under siege from abroad. Legions of supporters across the globe protested their eventual conviction based on the flimsiness of the evidence and one radical bombed the judge’s home. But, for both supporters and detractors, Sacco and Vanzetti’s high-profile trial and 1927 electrocutions were more about the subtext of their Italian ethnicity and anarchist political convictions than about the robbery. They were exonerated posthumously in 1977.

Town & Country

In the 1920s, the usual xenophobic/nativist tensions had another demographic dimension. The 1920 census showed that, for the first time in U.S. history, city dwellers and suburbanites outnumbered those in small towns and rural areas, raising fears that a traditional way of life was being eclipsed. The pristine rural purity they imagined never existed in the first place, but there was definite truth to the notion that a traditional way of life was going by the wayside. Prohibition and the Ku Klux Klan can be partially understood as attempts to hang on to that traditional way of life, but they only made city dwellers and immigrants resent “country bumpkins” or “rubes,” worsening the problem. The caricatures of the hillbilly and hick emerged around this time, whereas they wouldn’t have made sense before the 1920s because most folks were rural to begin with, and even 19th-century cities had livestock and smelled like farms. The widely-syndicated comic strip Li’l Abner (1934-77) poked fun at hillbillies in the fictional Appalachian town of Dogpatch. The term jaywalker comes from country “jays” in Los Angeles who, not used to urban traffic and more familiar with horses, stepped out in front of cars and buses. Imagine if you’d grown up when people and animals roamed freely in the streets. It would take some getting used to learning to look in both directions before crossing. This was especially a source of tension early on when only the wealthy could afford cars.

The rural-urban split, as historians call it, also had an economic dimension. The 1920s was an uneven period for agriculture because exports declined after WWI and drought on the Southern Plains set in by decade’s end. Meanwhile, the cities were booming because of renewed industrialism and electrification. The 1920s resonates with modern Americans increasingly divided politically and economically not just into red (conservative) and blue (liberal) states, but also the disputed “Big Sort” of blue “island” cities within otherwise red states, of which Austin is a prime example.

KKK Ascendant

KKK Ascendant

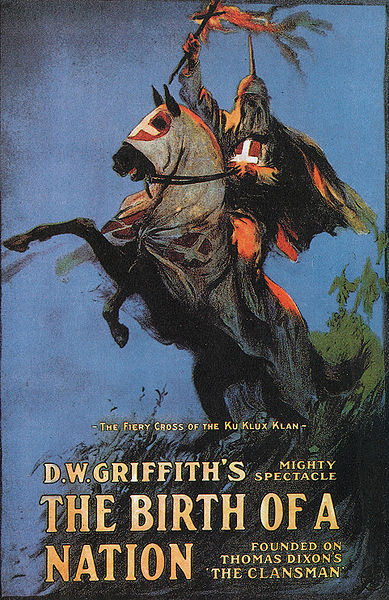

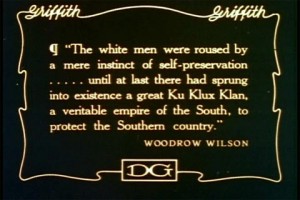

The 1920s version of the rural-urban split manifested in several ways, most famously the Ku Klux Klan’s (KKK) dramatic resurgence. A popular silent-era movie, Kentuckian D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), based on a book by Klansman Thomas Dixon, was a sprawling Civil War-era epic that glorified the vigilante organization. While the Woodrow Wilson quote on the left is torn out of context (he wasn’t a Klan supporter), he endorsed the movie’s basic version of Reconstruction — this from the U.S. president who started the United Nations. The new Klan started in Georgia and Alabama but, after 1920, had national not just regional appeal. They had booming urban chapters in Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Portland and represented the attitude of many Americans, urban and rural, North and South, who hated Jews, Catholics, Blacks, Mexicans, homosexuals, intellectuals, union organizers, and anyone else that didn’t fit the mold of the America they saw slipping away, including adulterers. Klan “night riders” abused all these groups physically, with most murders aimed at African Americans. They hated the Jewish producers who dominated Hollywood at Paramount, 20th-Century Fox, Columbia, Universal, MGM, and Warner Brothers, and paradoxically overlapped with the Catholics mainly responsible for regulating films (Chapter 4). For the Klan, early movies celebrated the drinking, womanizing, and criminal behavior they associated with Catholic immigrants and modernity, and they didn’t want gangsters or adulterous women depicted in movies unless they suffered punishments for their actions.

This was the golden age of the new Klan, the original chapters of which originated during Reconstruction when Union troops occupied the South after the Civil War. The federal government outlawed that original Klan during Reconstruction, but Birth of a Nation spurred renewed interest, and it was released at just the right time to capitalize on renewed xenophobia. Newspaper editor William Simmons called for a meeting to rejuvenate the dormant group and they burned a ceremonial cross at Stone Mountain, outside Atlanta. Simmons served as Imperial Wizard from 1915-39. Desmond Ang’s optional study below shows a strong correlation between klaverns (Klan chapters) and proximity to theaters showing Birth of a Nation. They recruited among Protestant churches and Freemasons. The Women’s Ku Klux Klan, formed in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1923, bridged the Klan to Prohibition, which became a centerpiece of its platform and brought them into conflict with bootleggers.

World War I was also a factor. Membership in far-right hate groups spikes when veterans return home. While the percentage of veterans attracted to these groups is so tiny as to be immeasurable (less than 1%), the percentage of new recruits in hate groups is so weighted toward veterans that America being in a postwar period is the single biggest predictor of increased activity — a larger indicator than racial or economic tension, immigration, etc. Prominent examples include George Lincoln Rockwell (WWII vet, Holocaust denier and American Nazi Party commander in the ’60s) and Timothy McVeigh (Gulf War veteran and perpetrator of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing). Both men were drummed out of the military, all branches of which are inclusive and condemn such ideology.

The 1920s was the one decade in American history when the Klan went mainstream enough that they could march proudly through the streets of any town, including 40k through Washington, D.C. (right). They sponsored baseball teams, baby beauty contests, christenings, road rallies, picnics, father-son outings, and junior leagues. The Face At Your Window (1920) showed American Legionnaires dressed a lot like Klansmen beating up Bolshevik radicals, hinting at more overlap between the Klan and mainstream conservatism and militarism than you’d see in other decades. Future president Harry Truman purportedly signed on briefly when he ran for office in Missouri in 1924, though he quickly withdrew his $10 membership fee when they demanded that he not hire any Catholics if he won. That was typical of Democratic politicians in the 1920s, who had to join the Klan briefly during primary elections to avoid being outflanked on racism by open “klandidates” like those in Texas or the Klan-endorsed mayoral candidates who won in Denver, Indianapolis, and Atlanta. Indiana was ground zero for a while, and the Klan even had politicians in Saskatchewan, Canada. The Klan could be anti-Black, anti-Catholic, anti-Mexican, or anti-immigrant, depending on locale. In the Pacific Northwest, they were anti-labor when loggers fought with the timber industry.

At its peak, the organization counted from 3-5 million members, before corruption, murders, and sex scandals contributed to its decline after 1925. Public relations suffered when D.C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan, kidnapped and raped a white woman, Madge Oberholtzer, ultimately mutilating her to death by a staph infection caused by biting and chewing. Before that, according to the best-selling book Freakonomics (2005), the Klan thrived as a pyramid scheme, with members being paid to sign up new initiates and sell paraphernalia like costumes and an assortment of merchandise starting with a K. Promoters called “klegals” signed up new members and “kluxed” the money upward toward the leaders. The Klan built on the post-WWI spirit of Red Summer when Whites lashed out at Blacks and Mexicans who’d moved north in the Great Migration.

Postcard of Leo Frank’s Lynching, Frey’s Hill (Frey’s Mill?) Cobb County, Georgia, 1915, Kenneth G. Rogers Collection, Atlanta History Center

New southern chapters also tapped into the post-Civil War resentment toward Yankee carpetbagger businessmen south of the Mason-Dixon Line, such as Jewish factory superintendent Leo Frank, whom they wrongly suspected of strangling a 13-year-old girl. He was pardoned posthumously in 1982, but in 1915 Georgia politicians used the trial to encourage a Klan revival. More wholesome Klan gatherings tapped into the decade’s penchant for nostalgic Americana and white pride, but lynchings like that of Frank or suspected black criminals also drew enthusiastic crowds and were the subject of a thriving postcard trade. It’s safe to say that, had social media then existed, lynching posts would’ve generated likes and wows interspersed with the occasional socially-conscious angries or sads. In Valdosta, Georgia in 1918, a white mob lynched African American Mary Turner for protesting her husband’s lynching the day before, then stomped to death her eight-month-old newborn infant when it fell to the ground. But racism was national rather than merely southern. In 1923, University of Minnesota football players stomped/spiked Iowa State African American Jack Trice, who died two days later. The schools didn’t play again for 66 years, but no one thought to punish the players.

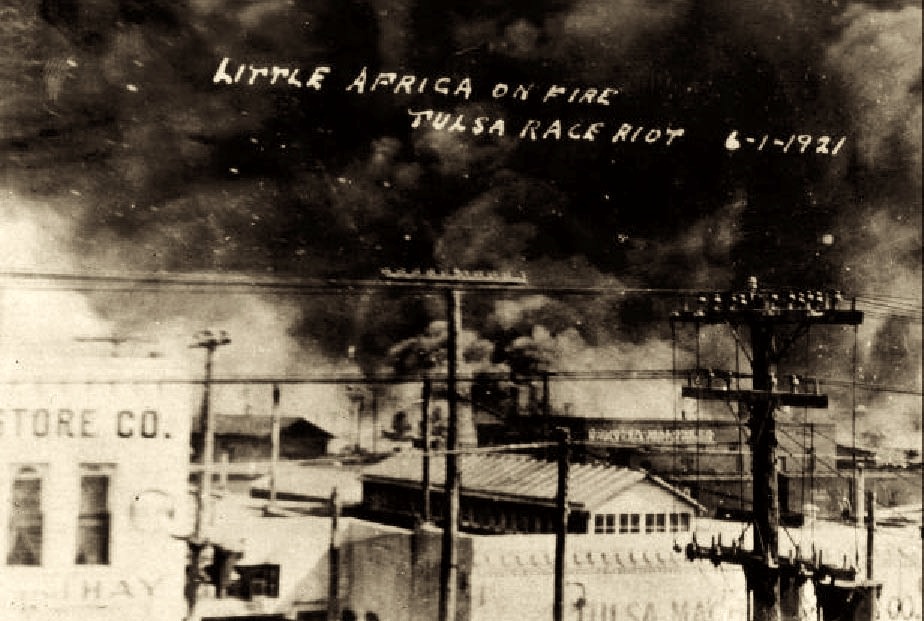

White banks wouldn’t lend to Blacks, making it impossible for them to start businesses. But, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, African Americans had followed the advice of activists Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois by opening their own bank which, in turn, lent to black entrepreneurs. Some had money to invest because there was oil on the land Cherokees had granted them at the end of the Trail of Tears when slavery was abolished in 1865. That, combined with Exodusters moving into Oklahoma after the Civil War, made greater Tulsa and surrounding towns the most prosperous African-American economy in the country, with the black neighborhood of Greenwood known colloquially as Black Wall Street.

In 1921, after 19-year-old African American Dick Rowland purportedly accosted a white woman in an elevator, armed Blacks surrounded Tulsa’s courthouse to protect him when the Tulsa Tribune posted a call-to-arms entitled “To Lynch Negro Tonight!” A street riot ensued that killed twelve (ten white and two black) after a white man tried to grab an Army-issued .45 from WWI vet O.B. Mann, asking “[N-word], where are you going with that pistol?” The following day, the sheriff deputized hundreds of Whites who destroyed Greenwood entirely (residential and commercial), burning down 30 square blocks and going door-to-door to torch houses and round up Blacks, marching them into temporary internment camps overseen by the National Guard and forcing them to carry identification badges. In the end, at least 36 died, possibly many more, with an all-white jury and Tulsa’s mayor T.D. Evans blaming the victims. No one was ever charged, despite a series of drive-by machine-gun shootings, grenade attacks, arsons, and even kerosene petrol bombs (aka Molotov cocktails) dropped from private airplanes. No one received compensation for their lost homes or businesses, or funeral bills. Given its traditional omission from textbooks until the 1990s, many Americans never learned about Tulsa until HBO’s Watchmen, based on a 1986 DC Comics series, came out in 2019, 98 years later. The massacre traumatized African Americans so badly that many didn’t tell their children or grandchildren about it, similar to combat veterans, though some oral histories survived. The city of Tulsa, with many of the culprits in charge, never investigated and mostly covered it up by destroying police records and cutting articles out of the Tribune before transferring to microfilm. They burned many victims in unmarked graves, making it hard to measure the death toll. The following year, 1922, 15k cheered a Klan march through downtown and, in 1923, a Klan-owned company built a meeting hall atop Greenwood’s ruins known as “Be No Hall” for its rules: Be No Negro, Be No Jew, Be No Catholic, Be No Immigrant. The city began to release information in the 1990s, and has since uncovered graves, but some of the best primary source documentation came, ironically, from the KKK’s souvenir postcards of “Little Africa” burning (above) and victims’ charred remains.

Given its traditional omission from textbooks until the 1990s, many Americans never learned about Tulsa until HBO’s Watchmen, based on a 1986 DC Comics series, came out in 2019, 98 years later. The massacre traumatized African Americans so badly that many didn’t tell their children or grandchildren about it, similar to combat veterans, though some oral histories survived. The city of Tulsa, with many of the culprits in charge, never investigated and mostly covered it up by destroying police records and cutting articles out of the Tribune before transferring to microfilm. They burned many victims in unmarked graves, making it hard to measure the death toll. The following year, 1922, 15k cheered a Klan march through downtown and, in 1923, a Klan-owned company built a meeting hall atop Greenwood’s ruins known as “Be No Hall” for its rules: Be No Negro, Be No Jew, Be No Catholic, Be No Immigrant. The city began to release information in the 1990s, and has since uncovered graves, but some of the best primary source documentation came, ironically, from the KKK’s souvenir postcards of “Little Africa” burning (above) and victims’ charred remains.

The Tulsa Race Massacre was not unprecedented. In Wilmington, North Carolina in 1898, 2k Democrats overthrew an elected bi-racial Fusionist government (Republicans and Populists), killing hundreds and destroying a black-owned newspaper. Commentators spun the Wilmington Insurrection as a “race riot,” which it was, but with the implication that Blacks initiated it when really it was a violent coup led by supremacists. In Abraham Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois, an entire black neighborhood was destroyed in a smaller 1908 riot that led white progressives to help co-found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP also used Mary Turner’s case in its anti-lynching crusades. While the prospect of black-on-white rape fueled much racism and paranoia and was featured in Birth of a Nation, the elevator incident was just the Tulsa Massacre’s pretext, escalated by the next day’s fight outside the courthouse. The real target was Greenwood and its broader implication that African Americans had access to middle class mobility. The subtext was for minorities to steer clear of finance or running small businesses, as that’s white stuff. Mobs razed neighborhoods and massacred Blacks in Elaine, Arkansas (1919), Ocoee, Florida (1920), and Rosewood, Florida (1923), with virtually no one punished — all an extension of Red Summer after World War I. Ocoee elected as its mayor the leader of a mob that murdered over 30 African Americans to prevent blacks voting in a U.S. presidential election and it became a sundown town, with minorities only allowed for daytime work or visits. In 1912, lynch mobs in Forsyth County, Georgia chased away their entire African-American population of 1100 after two unsolved rapes.

Not everyone went along with the vigilantism. In Texas, Williamson County District Attorney Dan Moody, Jr. courageously prosecuted four Klansmen for beating and killing a white northern salesman and was later elected state governor. Moody’s predecessor, Texas Governor “Ma” Ferguson, also opposed the Klan despite being a conservative and populist on many other issues and not supporting women’s suffrage (she served as a stand-in for her husband James, who’d been impeached on corruption charges).

Family Leaving Damaged Home After 1919 Chicago Race Riot, New York Public Library-Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

The Klan was active in Texas, though, including Austin. Beyond sporadic, ritualistic murders, chapters would scrape the skin off of young black men by dragging them up and down the streets of towns like Waco, Belton, or Sherman behind a Model T, just to send a message. But discrimination transcended vigilantism to include all kinds of rules and laws embedded in society — what later became known as structural, institutional, or systemic racism, but were then more explicit and known as “Jim Crow laws,” after the name of a 19th-century minstrel show character. Austin Blacks learned and ate in segregated schools and restaurants, and couldn’t swim in pools (including Barton Springs), try on clothes at stores, rent out ice skates, or attend movies at the Paramount or Stateside. In 1928, Austin established a formal plan to move all minorities to the east side, with Blacks and Hispanics north and south of 6th street, respectively. No minority outside the boundary could get utilities. (More in Chapter 15).

Give Us Your Tired, Your Poor, Your Huddled Masses…Or Not

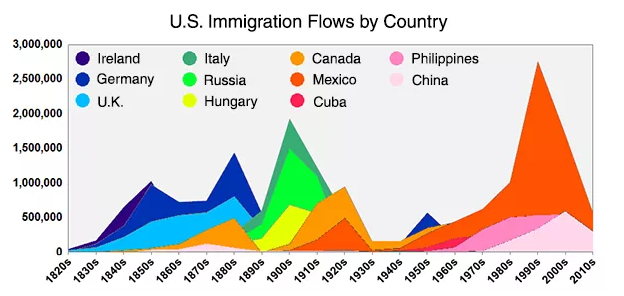

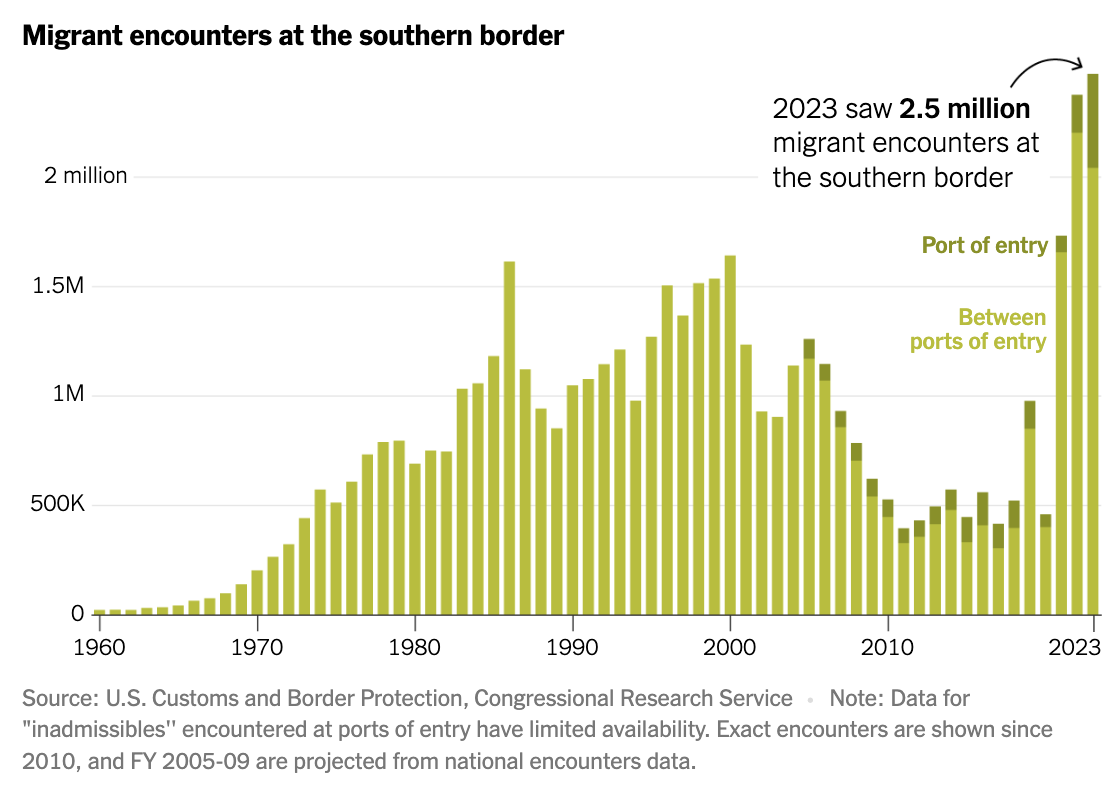

Famine and industrialization — including factories, improved rail and sea transportation, and the mechanization of agriculture — spurred emigration from Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Many went to Britain or America, especially the U.S., Canada, and Brazil, in search of economic opportunity and religious freedom (see peaks above). In the 1920s, though, racism and nativism virtually closed off immigration to the U.S. from eastern and southern Europe. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924 limited future immigration levels to 2% of ethnic ratios as measured by the 1890 Census, taken when the number of Whites from the “wrong parts of Europe” was lower, while updating and affirming anti-Asian immigration law. These laws more or less reset immigration law to the 1790 Naturalization Act that limited American migrants to Europeans, often further defined as Christian, which could be further defined as Protestant Christian. Senator Johnson hoped the 1920s laws would “stop a stream of alien blood.” You’ll be reading below about Joseph Pulitzer and Harry Houdini. Neither likely could’ve migrated to America post-1924 because they were Hungarian, as were two of Henry Ford’s key engineers, József Galamb and Jenő Farkas. The Immigration Act was engineered by lobbyist Harry Laughlin, America’s leading eugenicist and superintendent of the Eugenics Records Office, mainly to block “dysgenic” Italians and Eastern European Jews. Johnson-Reed didn’t cover immigration from Mexico or Latin America (and the census then classified Hispanics as white), but the prevailing mood and recent border conflicts during the Mexican Revolution hastened formation of the U.S. Border Patrol in 1924. The government repatriated thousands of Mexican-Americans back across the border, many of whom had been in the U.S. for generations working the railroads and cotton fields of Texas and the Southwest. Georgia Governor Clifford Walker promoted a steel wall across the border to keep out immigrants.

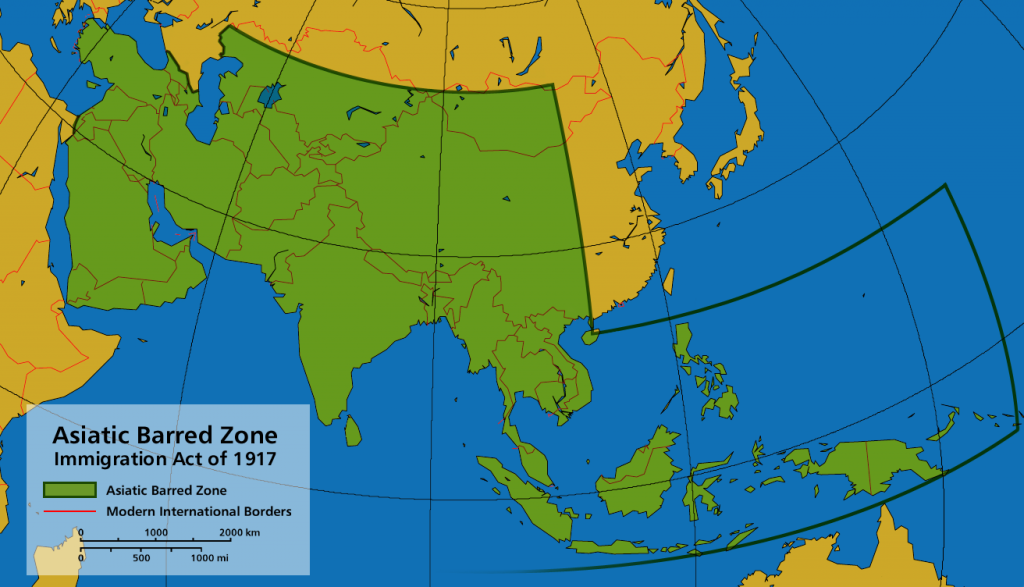

Immigration xenophobia traced to the Great War: the Immigration Act of 1917 set the tone for the ’20s by renewing and expanding East Asian immigration restrictions from the late 19th century to exclude South Asians and Middle Easterners, and barring white European contract laborers, alcoholics, political radicals, polygamists, prostitutes, vagrants, epileptics, illiterates over 16, paupers, anyone mentally or physically ill, and “idiots.”

The 1917 Act Added South Asia & Middle East To Existing (1882) Immigration Restrictions From East Asia, WikiCommons

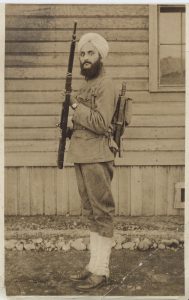

Although the Statue of Liberty has a bronze plaque from Emma Lazarus’ “New Colossus” poem that reads “Give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” the door more or less slammed shut between the mid-1920s and mid-’60s. In one of the poorest argued cases in their history, the Supreme Court ruled in 1923 that Indian American Bhagat Singh Thind, a WWI veteran (left), wasn’t an American citizen because he “didn’t fit the common man’s perception of a white man.” The 1924 Racial Integrity Act, set up to reinforce sterilization policies and prevent interracial marriage, and oblivious to what we now know about DNA, officially divided all Americans into “white and colored.”

Although the Statue of Liberty has a bronze plaque from Emma Lazarus’ “New Colossus” poem that reads “Give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” the door more or less slammed shut between the mid-1920s and mid-’60s. In one of the poorest argued cases in their history, the Supreme Court ruled in 1923 that Indian American Bhagat Singh Thind, a WWI veteran (left), wasn’t an American citizen because he “didn’t fit the common man’s perception of a white man.” The 1924 Racial Integrity Act, set up to reinforce sterilization policies and prevent interracial marriage, and oblivious to what we now know about DNA, officially divided all Americans into “white and colored.”

Despite America’s occasional fits of xenophobia, keep in mind that most countries didn’t populate themselves mostly through immigration the way the U.S. did, and today some disallow immigration altogether. For instance, while Denmark is invoked as a successful model of democratic socialism with free healthcare and college tuition, it protects its mostly white working class with strict immigration laws. People are more likely to share in homogeneous societies. Unlike Europe, though, the United States excels at assimilation. Indian-American Journalist Fareed Zakaria noted that the U.S. is so good at assimilating immigrants that first-generation parents often struggle to retain traditions among their children.

Cover of Theater Programme for Israel Zangwill’s play “The Melting Pot,” 1916, University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections Department

The U.S., today, has the most immigration in the world, but not the highest rates (13.7 % of U.S. citizens were born elsewhere). Immigration can depress wages in some sectors, but it provides skilled and unskilled labor, boosts technological ingenuity, correlates with high entrepreneurship, and is a net contributor to Social Security. Today, half of America’s PhD’s in math, science, and engineering are foreign-born, as are nearly 2.5 million people growing and distributing food, and 1.7 million in healthcare, with ~ 1/3 of the nurses in big cities. Since these aren’t vocations for which we have a surplus of native-born labor, it’s safe to say that, if we cut off immigration, we’d quickly become dumber, hungrier, and unhealthier. Home construction would slow to a snail’s pace. Some of America’s best entrepreneurs were first- or second-generation immigrants, across sectors like information technology (Apple, Amazon, Google, eBay, Yahoo, PayPal), retail (Proctor & Gamble, Colgate, Kraft Heinz, Nordstrom, Kohl’s, Levi Strauss & Co.), manufacturing (U.S. Steel, General Electric, DuPont, Honeywell, Emerson, Boeing, Tesla/SpaceX), banking (Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Capital One), media (Fox News, Comcast/Xfinity), and pharmaceuticals (Pfizer). The Paypal Mafia that launched YouTube, Yelp, LinkedIn, etc. included first-generation immigrants from South Africa, Germany, China, Poland, and Ukraine. Immigrants mined iron ore and coal, grew crops, and built America’s railroads and the atomic bomb that ended World War II. Forced immigrants built the nation’s capitol and grew many crops, including the cotton that fueled the early industrial revolution and dominated America’s exports to Europe in the 19th century. As of 2019, recent immigrants had started 45% of companies on the Fortune 500. Comedian George Carlin joked that “the reason they call it the American Dream is that you have to be asleep to believe it.” But, for immigrants, the land of opportunity isn’t just a corny cliché. Economically and culturally, the list of immigrant contributions to the U.S. is too vast to catalog here. Swedes brought log cabins. Spanish and Mexicans brought cowboys, ranching, and rodeos. Dutch brought golf, bowling, sledding, skating, the Easter Bunny, and one of many traditions that fed into modern Santa Claus. Jewish migrants invented comic book superheroes and, ironically, wrote iconic Christmas tunes (Stanford), including the best-selling song in history, “White Christmas,” that became a favorite of homesick overseas troops during World War II. Russian immigrant Israel Beilin, who changed his name to Irving Berlin, composed it. First-generation immigrants even invented hot dogs and baseball.

America’s unique history makes all anti-immigration sentiment, other than that of Indigenous Americans, hypocritical, and even their ancestors emigrated from Asia thousands of years ago. As depicted in this 1870 Thomas Nast cartoon “Throwing Down the Ladder By Which They Rose,” any American who opposes immigration is throwing down the same ladder their family used. However, the U.S. is an attractive enough country that it can’t begin to accommodate everyone who would come if it threw open the gates and completely opened its borders in the spirit of the plaque on Lady Liberty. The question is: who gets in and who doesn’t? The 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act removed the Asian ban and the 1965 Immigration Act, under which the U.S. still operates — with the ban on homosexuals removed in 1990 and banning of welfare benefits for the first five years in 1996 — maintained quotas but eliminated racial and geographic restrictions except for a 7% annual cap on any one country, creating long waiting periods of 15+ years from China and India. Post-1965, the Statue of Liberty’s message aligned better with reality than it had for the previous forty years. Prior to 1965, 70% of all U.S. immigrants were from Britain, Ireland, or Germany. Like the 1920s, these are challenging times for voters and citizens when it comes to immigration, with diverging Republican and Democratic parties staking out more radical positions than their immediate predecessors — sanity and compromise characterized immigration debates as recently as 2014 — with both parties operating on the shaky premise that more immigration equals more Democratic votes. For more on controversies surrounding modern immigration, see the optional section below.

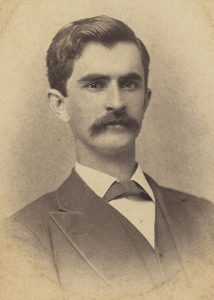

It’s easy to learn about prevailing ideas in historical eras and assume that everyone agreed with them, but there’s never consensus in any era, including ours. German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (left), for instance, pushed back against eugenics (Chapter 4 and 10) and the racist immigration policies of the 1920s. Congress hired him to investigate whether eastern and southern European immigration was contaminating the American gene pool. His report denounced eugenics as unscientific, but they overrode him. His was the minority viewpoint in the 1920s, but Boas’ ideas stood the test of time and were influential down the road. While there are geographic clusters in DNA that can be important to, for instance, medical research, he understood race partly as what we’d later call a social construct. Boas wrote that “the existence of any pure race with special endowments is a myth, as is the belief that there are races all of whose members are foredoomed to eternal inferiority.”

It’s easy to learn about prevailing ideas in historical eras and assume that everyone agreed with them, but there’s never consensus in any era, including ours. German-American anthropologist Franz Boas (left), for instance, pushed back against eugenics (Chapter 4 and 10) and the racist immigration policies of the 1920s. Congress hired him to investigate whether eastern and southern European immigration was contaminating the American gene pool. His report denounced eugenics as unscientific, but they overrode him. His was the minority viewpoint in the 1920s, but Boas’ ideas stood the test of time and were influential down the road. While there are geographic clusters in DNA that can be important to, for instance, medical research, he understood race partly as what we’d later call a social construct. Boas wrote that “the existence of any pure race with special endowments is a myth, as is the belief that there are races all of whose members are foredoomed to eternal inferiority.”

Scopes Monkey Trial

Scopes Monkey Trial

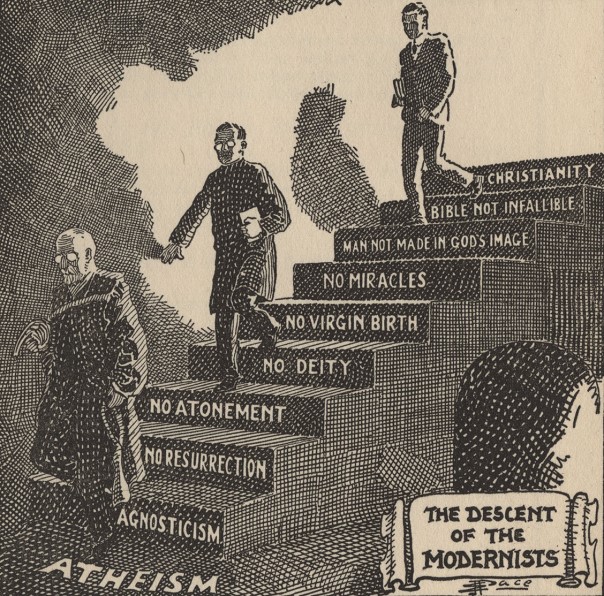

In the 1920s, new ideas also put off traditionalists, especially Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Many states forbade the teaching of evolution in public schools, including Tennessee with the 1925 Butler Act. In Dayton, Tennessee, businessmen and the school board thought they could drum up attention and tourist dollars by assigning a textbook with sections on evolution, extinction, and eugenics to a substitute public high school biology teacher, John Scopes. Evolution and extinction are intertwined ideas because they both deny the (unchanging) immutability of species implied in a fundamentalist reading of the Bible, instead endorsing transmutation and the idea that extinction is part of the evolutionary process. Had man really descended from the creatures that the Bible taught God had given man dominion over? While the idea that humans are animals took some getting used to, evolution was widely accepted after the 1870s and generated surprisingly little controversy in the late 19th century. The evidence, if not as incontrovertible as today, was persuasive to those who read Darwin or followed the research of real geneticists like Augustinian friar Gregor Mendel. What changed was the widespread advent of public high schools during the Progressive Era. Now mainstream Americans had to confront the theory and its unsettling implications. And, as explored and updated in the optional article below by Joshua Zeitz, they had to confront the tension inherent in democracy between protecting individual rights and the rights of majorities to exercise their power through local politics. Christian fundamentalism, as now interpreted, was refined in the early 20th century, marked by publication of A.C. Dixon’s The Fundamentals (1910-15). Dixon (right) opposed evolutionary theory and the strain of 19th-century Christian liberalism emerging in mainline Protestantism that challenged literal Scriptural interpretations and endorsed the Social Gospel of the Progressive Era. Dixon, who ministered in Baltimore, Brooklyn, Boston, Chicago (Moody Church), and London, but whose teachings gained most traction in rural areas, was arguably the most influential modern American theologian, introducing an apocalyptic strain into fundamentalism. Oil barons Milton and Lyman Stewart funded Dixon’s ministry and the oil industry continued a lasting alliance with fundamentalism, especially in Sun Belt cities like Los Angeles and Dallas.

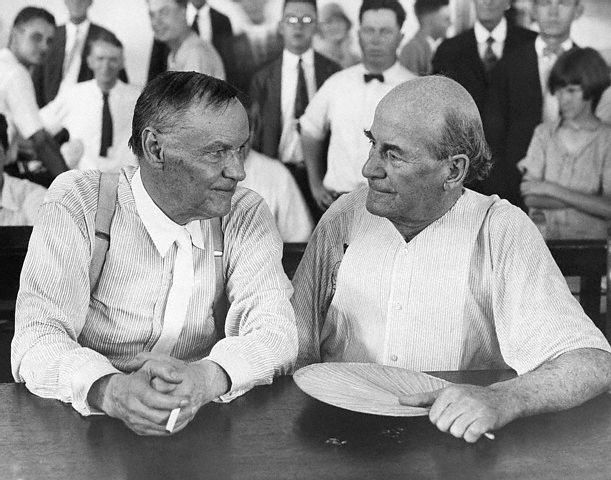

The Scopes case was somewhat of a farce insofar as the state had actually approved the text, despite the Butler Act, and Scopes wasn’t even sure at first if he’d taught anything having to do with evolution. Nonetheless, he agreed to go along with the case at the urging of the American Civil Liberties Union, who was advertising for a test case in the Chattanooga Times. The text, George William Hunter’s A Civic Biology (1914), would instead stand out today because of its racist eugenic passages, but the controversy at the time was over evolution. Scopes was indicted and the resulting Scopes “Monkey Trial” was perhaps the most famous in American history. It was the first trial broadcast on radio (WGN Chicago), creating a media sensation similar to the O.J. Simpson murder trial in 1994. It pit two high-profile attorneys against each other: agnostic Clarence Darrow of Chicago arguing for the defendant and Fundamentalist Christian William Jennings Bryan arguing for the plaintiff, Tennessee. You may recognize Bryan. He was a three-time Democratic presidential candidate (losing in 1896, 1900 and 1908), Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson and, some say, the inspiration for the Lion in Frank Baum’s Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

The Scopes trial pitted reason and modernity against faith and tradition, going straight to the heart of the rural-urban split in 1920s America. In a rare case where the defense cross-examined a counsel for the prosecution, Darrow grilled Bryan on the Bible, his supposed area of expertise. While Darrow was reared on the “Great Agnostic” Robert G. Ingersoll in his youth (Chapter 1), his superior Biblical knowledge allowed him to argue circles around the aging Bryan, who thought evolutionary theory opened the door for a ruthless, survival-of-the-fittest, capitalist society. As we saw in Chapter 3, by the Gilded Age, Darwin had been hijacked by Social Darwinists to justify class warfare, so Bryan’s fears weren’t unwarranted. Not all Creationists are the same. Bryan was a “day-age” creationist insofar as he saw each of the seven days in the Genesis creation story as representing a long geological epoch, but he thought evolution constituted a slippery slope to atheism (right). Sadly, after several days arguing the high-profile case in the stifling heat of the crowded courtroom and then outdoors, the humiliated Bryan died in his sleep five days later. A few tourist dollars came in with a carnival atmosphere and even caged monkeys but, for the most part, the city planners’ gambit was a bust.

The Scopes trial pitted reason and modernity against faith and tradition, going straight to the heart of the rural-urban split in 1920s America. In a rare case where the defense cross-examined a counsel for the prosecution, Darrow grilled Bryan on the Bible, his supposed area of expertise. While Darrow was reared on the “Great Agnostic” Robert G. Ingersoll in his youth (Chapter 1), his superior Biblical knowledge allowed him to argue circles around the aging Bryan, who thought evolutionary theory opened the door for a ruthless, survival-of-the-fittest, capitalist society. As we saw in Chapter 3, by the Gilded Age, Darwin had been hijacked by Social Darwinists to justify class warfare, so Bryan’s fears weren’t unwarranted. Not all Creationists are the same. Bryan was a “day-age” creationist insofar as he saw each of the seven days in the Genesis creation story as representing a long geological epoch, but he thought evolution constituted a slippery slope to atheism (right). Sadly, after several days arguing the high-profile case in the stifling heat of the crowded courtroom and then outdoors, the humiliated Bryan died in his sleep five days later. A few tourist dollars came in with a carnival atmosphere and even caged monkeys but, for the most part, the city planners’ gambit was a bust.

At least Bryan and Tennessee won the case, though their State Supreme Court later acquitted Scopes. It was Pyrrhic victory for Fundamentalists since Darrow had cornered Bryan into admitting that he didn’t take everything in the Bible literally, but the case still galvanized their effort to keep evolution illegal in public schools up until the 1968 Epperson v. Arkansas Supreme Court case. Texas outlawed evolution in its public schools shortly after the Scopes case, spearheaded by Ma Ferguson. The debate continues today in the form of evolution/natural selection versus intelligent design or fine-tuned universe, “equal time,” and “teach the controversy” debates, with evolution’s inclusion in public school curriculums motivating many parents to home-school their children or send them to private schools. As for Dayton, Tennessee, they continue to cash in on “evo-tourism” dollars by hosting an annual Scopes Trial Play & Festival, vindicating the town fathers’ original strategy.

Democrats Divided

Democrats Divided

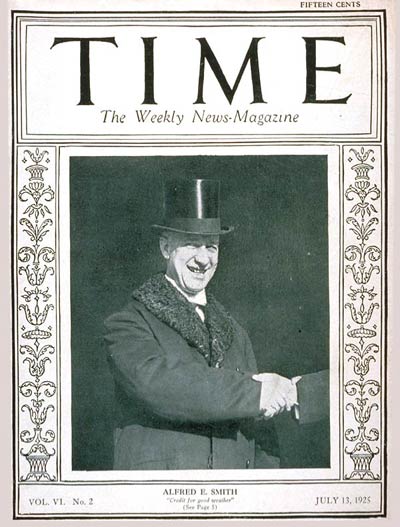

Politically, Scopes wasn’t Democrat versus Republican; mostly it was rural Democrats versus urban Democrats. In that charged rural/urban environment, Democrats failed to unite working classes on the national level in the 1920s. How could they, when they represented both intellectuals and Fundamentalists, and both ethnic immigrants from northern and Midwestern factories and mines and the remnants of the Confederacy that hated them? The Klan ran five state legislatures in the mid-1920s, not just in Texas and Oklahoma, but also Indiana, Colorado, and Oregon. The Democratic Solid South could dominate local and state elections, as could the Democratic machines of northern cities, but the two factions couldn’t find a common platform when they gathered for their national convention in New York’s Madison Square Garden to nominate a presidential candidate. The KKK tried to take over the boisterous 1924 Convention as northern Democrats failed to add anti-lynching legislation to the plank along with an outright denunciation of the Klan. This was an open convention, before primaries determined candidates ahead of time. The southern-and-western faction nominated William McAdoo of California (Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law) and shouted “booze, booze, booze” at supporters of Irish Catholic New Yorker Al Smith because of his wetness (support for repealing Prohibition). As with culture wars in the 2020s, 1920s tribes talked past each other with whataboutisms; in this case, racists rationalized their position by associating their opponents with alcohol. Smith supporters chanted back “Ku Klux McAdoo” because he refused to denounce the Klan, while Smith (right) condemned lynching and racial violence. Eventually, the Democrats nominated compromise candidate John Davis, but Republican Calvin Coolidge annihilated him in the 1924 election as Progressive and ex-Republican Robert La Follette (P-WI) stole more votes from Davis than Coolidge.

The same was true in 1928, when Al Smith won the Democratic nomination. Smith, a self-described “uneducated Mick [Irishmen] from the Fourth Ward,” latched onto the Tammany Hall political machine as an errand boy, educating himself in law and politics like a 20th-century urban version of Abraham Lincoln. He’d dropped out in 8th grade and joked that he’d only earned an “FFM” degree from rolling barrels and cleaning fish at the Fulton Fish Market. Some Democrats couldn’t abide with the prospect of a former scrappy, street kid from Manhattan’s Lower East Side occupying the Oval Office. As Smith campaigned across the South, Texans and Oklahomans jeered and pelted him with rotten fruit, the preferred projectile of rural Americans who wanted to harass but not seriously harm others. Many southern Democrats didn’t appreciate his New York accent, religion, or wetness. Bob Jones, founder of the South Carolina college bearing his name, spoke for some reactionaries when he said of the Yankee, “I’d rather have a [N-word] in the White House than see Al Smith as president.” Scores of other conservative Protestants didn’t share Jones’ bigotry and Smith won some southeastern states, but Herbert Hoover dominated the North and won the presidency. Democrats struggled to unite a diverse coalition under a single umbrella and lost three presidential elections in the 1920s. Comedian Will Rogers quipped, “I belong to no organized political party…I’m a Democrat.” Rogers also captured the hypocrisy and indecision over Prohibition, joking that his home state of Oklahoma “would vote dry for as long as people can stagger to the polls.”

L-R: President Warren G. Harding, First Lady Mrs. Florence Harding, Mrs. Grace Goodhue Coolidge, Vice President Calvin Coolidge, ca. 1921, National Photo Company-Library of Congress

GOP In Control

The GOP was better suited to the laissez-faire (free market) tendencies of booming economies, anyway, and the 1920s were booming. The Progressive Era mostly petered out, with no new major legislation, but they didn’t repeal the Progressive legislation of the previous thirty years. That’s because Progressivism — defined not just by politicians and activists, but also forward-thinking business managers — hadn’t killed off business so much as it improved life for workers and strengthened the middle class, laying the foundation for 1920s prosperity. A decently paid workforce with more time off provided the customers to buy products as the U.S. moved toward a consumer-driven economy. Still, the country’s prevailing political mood was to let the vibrant new economy run without further interference. Republicans controlled both branches of Congress and of three Republican presidents in a row – Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover – the first two, especially, shared their Secretary of Treasury Andrew Mellon’s view that Washington shouldn’t be poking around Wall Street or the wider economy, other than to keep tariffs high to protect American industry. Mellon cut the top tax rate from 77 to 24% and loosened up stock market restrictions, allowing investors to leverage their bets by going in debt, or on margin (you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to suspect that we’ll hear more about that in the next chapter).

Calvin [“Get Cool with”] Coolidge, future president Ronald Reagan’s second-favorite president behind Franklin Roosevelt, captured the era’s tone when he said, “The chief business of the American people is business.” Other than farming, which suffered due to the rebuilding of Europe after the war and dry weather, Harding and Coolidge presided over a strong economy that manufactured nearly half the world’s goods. Like China and Southeast Asia today in the popular imagination, the U.S. was the “workshop of the world” (really, it’s still the U.S.). Even wheat farming on the Southern Plains boomed until drought set in. Underlying the strong industrial economy were the advent of mass-produced cars and electricity going mainstream, now a half-century after Thomas Edison first developed an efficient light bulb and a century after Georg Ohm and Michael Faraday laid the groundwork for electrical engineering.

New Industrialism

Building out the electrical grid not only powered homes, offices, and factories, but the whole economy insofar as it created markets for electronic appliances. Most of America was juiced by 1930, augmenting the already thriving Industrial Revolution. Replacing steam engines, electric “dynamos” powered factory assembly lines, many dedicated to making plug-in appliances like refrigerators, washers/dryers, vacuum cleaners, and radios that themselves ran on electricity. Two years after the first radio station went on air in Pittsburgh in 1920 (KDKA), Americans spent $60 million on radios, parts, and accessories. Not only did new sectors open up in consumer durables, but also electricians were needed to wire homes and buildings. Times were good for both management and labor, as the 40-hour work-week became the norm for blue-collar workers. Railroad workers won the right to the eight-hour day and time-and-a-half for overtime with the Adamson Act of 1916. Other industries followed suit when the Supreme Court upheld the act’s constitutionality.

Some lucky office workers labored in better conditions, too, because of air conditioning. AC, along with elevators and telephones, enabled skyscrapers, making it bearable to work on high floors that would otherwise get too warm and be too hard to get to by stairs. Willis Carrier introduced the first real system at a movie theater in New York in 1929. Hollywood was suffering from lower ticket sales in the summer because theaters were too stuffy. No AC, no summer blockbusters. Carrier modeled home units at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Air conditioning raised worker productivity, home comfort levels — probably lengthening lives — and CO² levels in the atmosphere, if only about half as much as heaters. Air conditioning contributed to the demise of front porch socializing but also to Southern industrialization. Textile mills, for instance, could now set up nearer cotton fields. Assembly lines moved south as well. James Duke made over four million cigarettes per day in Durham, North Carolina. Steel mills like those in Pittsburgh, Gary, Baltimore, and Cleveland popped up in Birmingham, Alabama after the discovery of hematite (red ore) at nearby Red Mountain.

Ultimately, AC led to a demographic shift in America away from the industrial Northeast toward the Sunbelt, boosting cities like Miami, Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Phoenix. This occurred gradually over the next century, accelerated by the interstate highway system’s construction in the 1950s-’60s. In 1909, Las Vegas had fewer than a thousand residents. It would’ve stayed that way without air conditioning, better highways, and construction of Hoover Dam (next chapter).

Meanwhile, Clarence Birdseye’s breakthroughs led to prepackaged foods when he discovered how to flash-freeze food without destroying nutrients and flavor. His epiphany came when living among the Inuit fishermen of Labrador, among whom he discovered that the quicker the freezing process, the smaller the ice crystals; the smaller the crystals the fewer the nutrients lost and flavor destroyed. America had entered the age of frozen foods, making two-income families more practical because they sped up meal preparation, just as electric washers and dryers sped up and simplified laundry. Today, flash-frozen is more nutritious than all but the most freshly-picked produce.

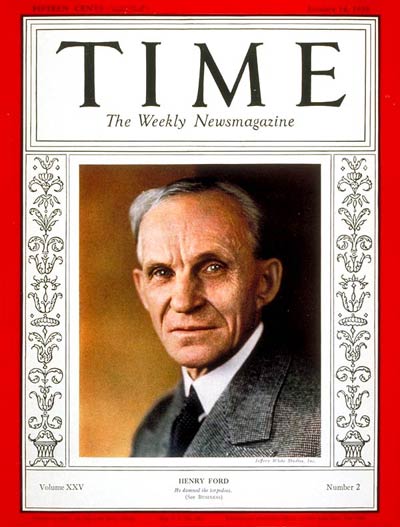

Auto Industry & Henry Ford

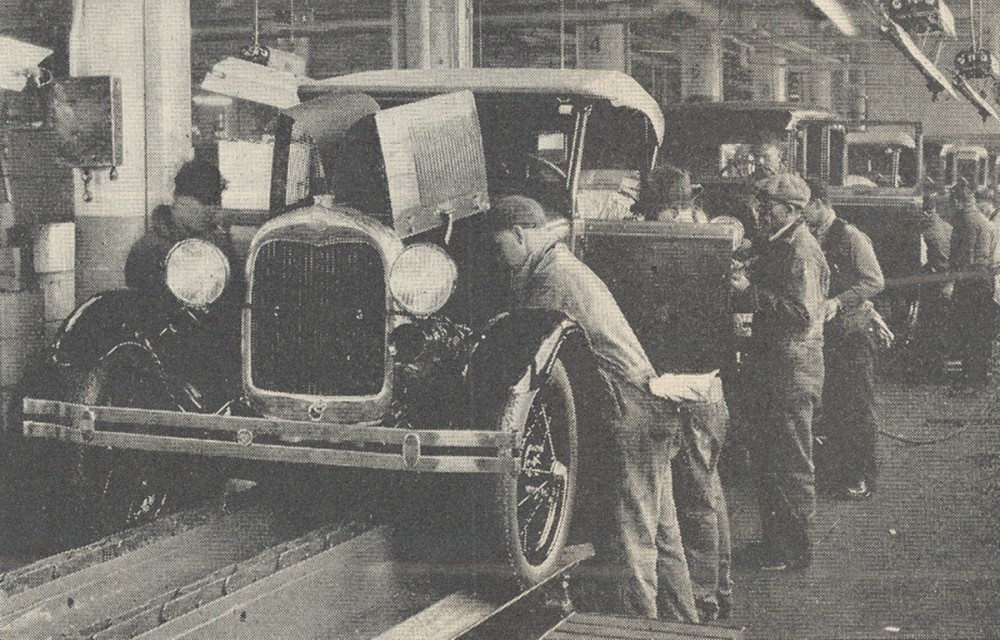

No manufacturing sector exemplified the New Industrialism better than cars and trucks. Henry Ford led the way among dozens of automakers around Detroit, Michigan, aka the “Motor City.” He, too, moved to eight-hour shifts in the 1910s, increasing production in the process. Ford didn’t invent the automobile but he was a good mechanic and brilliant businessman who understood the need to build an affordable, practical car for the masses. Ransom Olds had a similar notion and started building the Oldsmobile Curved Dash on an assembly line in 1901, but Ford’s post-1911 line, engineered by Danish immigrant William Knudsen, was bigger and powered by electricity — similar in scope to a meatpacking plant except in reverse: assembling cars rather than disassembling pigs and cows. While most early “horseless carriage” makers were obsessed with winning races, Olds and Ford realized the potential mass-market appeal of cars long before roads, bridges, and gas stations were there to service them. Ironically, Ford had to win races to make a name for himself in the auto industry and attract investors (below). “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday,” so the saying goes. Racing stayed relevant as the testing ground of cars, leading to innovations like the rearview mirror, disc brakes, seat belts, and fuel injection.

Ford wasn’t trying to spur the growth of cities, highways, and suburbs. Rather, he thought cars could save rural America by making it easier for farm families to get around. He understood the isolation of rural life and rightly thought that improved transportation would make living in the country more amenable. Despite a limited education, Ford knew his way around the courtroom, too. He was among the first to profit from the government’s anti-trust movement, as he won a case in 1911 against the ALAM (Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers) cartel that controlled automotive patents, the same year the government broke up Standard Oil. People instinctively think of monopoly-busting as anti-business, but it spurs competition for both customers (lower prices) and competitors. Ford also branched out beyond cars. As with horseless carriages, Ford didn’t invent tractors but he was first to mass-produce them (Fordsons). He was involved in the advent of modern supermarkets and airports and started a utopian rubber plantation in Brazil called Fordlândia — utopian not so much for the workforce but for securing Ford cheap supplies of rubber (vertical integration). He had hopes for mass marketing planes he called “flying flippers,” as flipper was slang for car (similar to those flown over Slovakia in 2022). The first passenger airline, Stout Air Services (1925-30), connected Ford’s Dearborn airport to Cleveland and Grand Rapids. But earth-bound flippers were Ford’s specialty.

Ford wasn’t trying to spur the growth of cities, highways, and suburbs. Rather, he thought cars could save rural America by making it easier for farm families to get around. He understood the isolation of rural life and rightly thought that improved transportation would make living in the country more amenable. Despite a limited education, Ford knew his way around the courtroom, too. He was among the first to profit from the government’s anti-trust movement, as he won a case in 1911 against the ALAM (Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers) cartel that controlled automotive patents, the same year the government broke up Standard Oil. People instinctively think of monopoly-busting as anti-business, but it spurs competition for both customers (lower prices) and competitors. Ford also branched out beyond cars. As with horseless carriages, Ford didn’t invent tractors but he was first to mass-produce them (Fordsons). He was involved in the advent of modern supermarkets and airports and started a utopian rubber plantation in Brazil called Fordlândia — utopian not so much for the workforce but for securing Ford cheap supplies of rubber (vertical integration). He had hopes for mass marketing planes he called “flying flippers,” as flipper was slang for car (similar to those flown over Slovakia in 2022). The first passenger airline, Stout Air Services (1925-30), connected Ford’s Dearborn airport to Cleveland and Grand Rapids. But earth-bound flippers were Ford’s specialty.

Ford synthesized the assembly-line systems pioneered by Olds and meatpackers and attention to detail and efficiency promoted by Frederick Winslow Taylor and Richard Sears. He started Ford Motor Company in 1903, working his way through the alphabet with Models A-S. Each had a weakness he was dissatisfied with until he finally struck gold with the two-speed, four-cylinder, 20 HP Model T in 1908, a game-changing machine in world history. At his Highland Park plant outside Detroit, Ford tinkered with production just as he tinkered with transmissions. Gone were the movers and pushers of his early garages, replaced first by a rolling track, then gravity, and finally by an electric conveyor belt moving in front of stationary workers as Ford hovered nearby with his stopwatch. Precision engineering was key, as there was no time to stop and file down parts that didn’t fit. Ford also streamlined his engine, removing the water pump and need for a fuel pump by making sure the gas tank was higher than the engine. By 1923, his crew could bang out a Model T every 15-40 seconds, with each car taking about an hour-and-a-half to build start-to-finish. Today’s Volkswagen plant in Wolfsburg, Germany turns out a VW every 16 seconds, about the same rate, except with the help of 12k position-control, stationary industrial robots. Ford built parts in Michigan and distributed knock-down kits for assembling Model T’s in West Coast cities, Japan, and throughout Europe and Latin America.

Between 1908 and 1927, 15 million “Tin Lizzies” rolled off the assembly line. Because of efficiency of scale, its price plummeted from $850 to $260, making it affordable for the middle-classes. By the mid-20’s there was a market in used cars, offering mobility to the lower middle-classes. The Model T chassis could be converted into pickups, delivery trucks, etc. They proved their durability as ambulances on the Western Front in World War I. Each no-frills car came with few options outside the toolkit under the driver’s side seat. At first, even windshields were optional. Its hand-cranked magnetic generator powered the lights and ignited the engine. With few mechanics, owners had to do most of their maintenance and just starting it was a tedious 10-step process. Without a fuel pump, the car could run out of gas on extended inclines. Drivers adventuring west as “sagebrushers” needed trailers to haul extra gear, making their outfits look like a cross between a modern SUV and 19th-century covered wagon. In 1915, the AAA advised motorists to check loose nuts and bolts before every trip, know how to change brake pads, and keep gas, oil, two spares, two jacks, chains, copper wire, extra spark plugs, and a spade, axe, and rope in their vehicle at all times. While it doesn’t look durable to modern eyes, the Model T was sturdy enough to handle dirt and gravel roads in an era with few paved roads. For that matter, the Western Front in WWI didn’t have paved roads between trenches and field hospitals. Ford started building enclosed passenger cabins after Essex pioneered the trend away from open touring cars in 1922.

Ford paid decent wages but turned his line up to maximum capacity at around one foot per minute. He disallowed talking, laughing, or whistling on the line. Although the work required more mechanical skill than commonly thought, it was monotonous. Despite being among the first factory owners to give employees weekends off (1926), many workers couldn’t take the grind, leading to high turnover known as “Forditis.” He also reserved the right for his Sociological Department to enter workers’ homes to make sure they were clean and that the workers were married and weren’t drinking, spending their paychecks frivolously, or sending checks back to their home countries. If this sounds extreme, understand that today’s companies have the right to secretly screen, test, spy on, and track employees in ways that would make Ford blanch. At least he was transparent.

Ford paid decent wages but turned his line up to maximum capacity at around one foot per minute. He disallowed talking, laughing, or whistling on the line. Although the work required more mechanical skill than commonly thought, it was monotonous. Despite being among the first factory owners to give employees weekends off (1926), many workers couldn’t take the grind, leading to high turnover known as “Forditis.” He also reserved the right for his Sociological Department to enter workers’ homes to make sure they were clean and that the workers were married and weren’t drinking, spending their paychecks frivolously, or sending checks back to their home countries. If this sounds extreme, understand that today’s companies have the right to secretly screen, test, spy on, and track employees in ways that would make Ford blanch. At least he was transparent.

Immigrants studied at Ford’s own ESL school before graduating at the Pageant of the Ford Melting Pot, with students in native costumes going into a giant pot where teachers stirred giant spoons before graduates emerged in American clothes waving a U.S. flag. Such proactive assimilation wasn’t just a Gentile project. Joseph Pulitzer’s [New York] World featured guides for fellow immigrants to American styles, customs, and etiquette (his paper also raised funds among children for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal). In 1914, Ford raised wages to $5/day, or what comes to around $14.50/hr. or $30k/year gross, adjusted for inflation — exactly double the 2015 minimum wage. He paid African-Americans 90¢ on the white dollar, which was nearly unheard of elsewhere in the country and contributed to the Great Migration. However, they had to perform the most dangerous tasks of pouring steel in the foundry and lifting engines. Ford argued that good pay made workers less likely to quit and better able to afford the cars themselves. Unlike Karl Marx or the 19th-century industrialists Marx condemned, Ford saw workers not just as the exploited proletariat but rather as potential consumers. His assembly line workers drove Model-T’s. For Ford, that included minorities and the immigrants from Poland, Russia, and the Middle East that he assimilated.

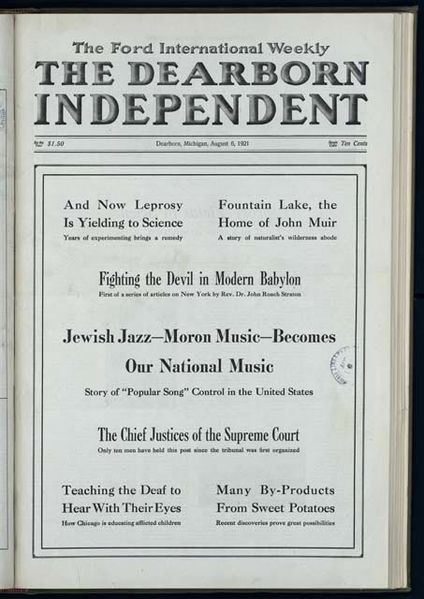

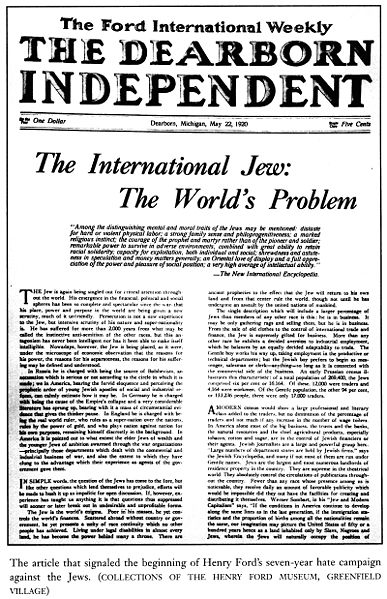

Many working-class Americans idolized Ford because he’d done so well for himself despite not having gone past 8th grade. The more the press rode him for his ignorance of American history, etc., the more common people rallied behind him. But Ford’s melting pot workforce belied deeper bigotry. His anti-Semitism showed the underbelly of intellectual ignorance and he took advantage of his stature to spread that ignorance. Ford dealerships across the country distributed his Dearborn Independent weekly that explained how Jewish people were destroying the country and world. This was typical fare: “The Jews are the scavengers of the country…wherever there’s anything wrong with the country, you’ll find the Jews on the job there.” The paper ran Protocols of the Elders of Zion in serial form, a translated forgery from Czarist Russia depicting a Jewish conspiracy to take over the economy and media. The KKK bound and published 96 of the articles as The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem. Whereas the Protocols perpetuated the blood libel myth that Jews drank Gentile children’s blood during Passover, QAnon today posits that liberal conspirators are operating a cannibalistic, child sex-trafficking ring, likewise appealing to maternalism.

According to testimonies at the Nuremberg Trials after the Holocaust, The International Jew influenced Nazi ideology. The works attracted the attention of Adolf Hitler, who had a photo of Henry Ford in his office and who had him write the foreword to his American edition of Mein Kampf. Nazis awarded the aging industrialist the Grand Cross of the German Eagle in 1938. His subsidiary in Germany, Ford Werke, worked enslaved Jews. Ford, then, represented not only the efficiency of the new industrialism but also the xenophobia of the 1920s. For him, Jews were “mere hucksters…traders who didn’t want to produce, but make something out of what someone else produces.” But Ford wasn’t a Nazi himself; he’d even been somewhat of a pacifist when he tried to organize peace talks to end World War I. Stay tuned to this story because, despite his toxic and influential anti-Semitism, and despite helping to sustain and sanction Nazism, Ford’s manufacturing technique contributed to America’s victory in WWII.

Despite Ford’s anti-Semitism, Jewish architect Albert Kahn designed the Highland Park plant and its successor. From 1916 to 1928, Ford and Kahn built the largest factory in world history at River Rouge, near Ford’s farm outside Detroit. It was a model of vertical integration, complete with its own blast furnaces to smelt ore, foundries, tool works, power plant, fire department, security, and railroad connections to feed its 120 miles of conveyor belts. They dredged the nearby river to allow for freighters. The plant used more water daily than the cities of Detroit, Cincinnati, and New Orleans combined and employed 75k workers. Though he and Kahn conceived this colossal vanguard of industrialization, the River Rouge Complex was so gigantic, noisy, and heartless that Ford grew to hate it and gradually quit visiting. He put his time into a nostalgic 19th-century village called Greenfield and transplanted to the village his original small factory, the Wright Brothers’ bicycle shop from Dayton, Ohio, and his idol Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park from New Jersey. Today, it’s the biggest museum in America. Like Tesla, Ford worked for Edison but, unlike Tesla, Edison supported Ford’s ventures.

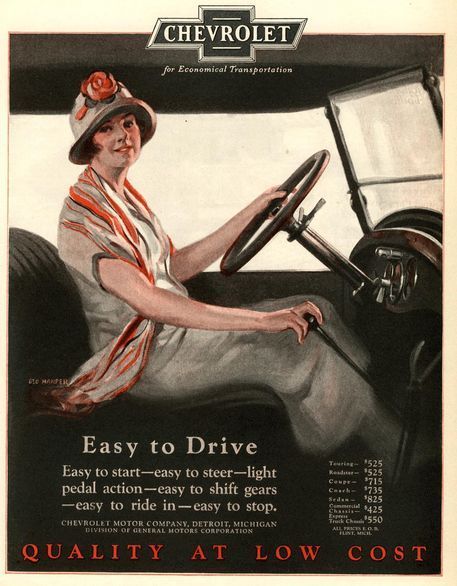

In the 1910s, Ford sold over half the cars in the world, but a consortium of other manufacturers including Pontiac, Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac formed General Motors (GM) to whittle away at Ford’s market share. Cadillac was the remnant of one of Ford’s own earlier companies. GM tried to buy out Ford, too, but his $3 million asking price was too high. Walter Chrysler retooled GM along the lines of Ford’s efficient assembly. After GM ousted its CEO, William Durant, Durant hired Swiss racer/designer Louis Chevrolet (right) to form his own company and, after Durant bought enough stock to regain leadership in GM, Chevrolet joined GM. Ford’s chief engineers, Horace and John Dodge, were unhappy that Ford never paid out dividends to his original minority investors (including the Dodge brothers), instead reinvesting back into the company. Ford hired his son Edsel as president to send fear into Wall Street, driving down Ford’s price enough that he could buy back his minority investors’ stock cheaply until he owned 100% of it himself (for perspective, consider that John Rockefeller never owned more than 25% of Standard Oil). Edsel was an innovative engineer and had a mind for business, but Henry never intended on letting his son run the company for as long as he was alive; the stock ruse was a classic “poop and scoop” as opposed to the reverse “pump and dump.” The Dodge Brothers, whom Ford bought out for $25 million, left to form their own company but both died from flu complications at the end of World War I. Chrysler, who didn’t get along with Durant, then left GM and bought Dodge, renaming it Chrysler. There were hundreds of early car companies, but clear winners emerged by the 1920s that enjoyed an economy of scale and resources for efficient mass production. The “Big Three” that dominated for the next half-century was in place: Ford, GM, and Chrysler.

In the 1910s, Ford sold over half the cars in the world, but a consortium of other manufacturers including Pontiac, Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac formed General Motors (GM) to whittle away at Ford’s market share. Cadillac was the remnant of one of Ford’s own earlier companies. GM tried to buy out Ford, too, but his $3 million asking price was too high. Walter Chrysler retooled GM along the lines of Ford’s efficient assembly. After GM ousted its CEO, William Durant, Durant hired Swiss racer/designer Louis Chevrolet (right) to form his own company and, after Durant bought enough stock to regain leadership in GM, Chevrolet joined GM. Ford’s chief engineers, Horace and John Dodge, were unhappy that Ford never paid out dividends to his original minority investors (including the Dodge brothers), instead reinvesting back into the company. Ford hired his son Edsel as president to send fear into Wall Street, driving down Ford’s price enough that he could buy back his minority investors’ stock cheaply until he owned 100% of it himself (for perspective, consider that John Rockefeller never owned more than 25% of Standard Oil). Edsel was an innovative engineer and had a mind for business, but Henry never intended on letting his son run the company for as long as he was alive; the stock ruse was a classic “poop and scoop” as opposed to the reverse “pump and dump.” The Dodge Brothers, whom Ford bought out for $25 million, left to form their own company but both died from flu complications at the end of World War I. Chrysler, who didn’t get along with Durant, then left GM and bought Dodge, renaming it Chrysler. There were hundreds of early car companies, but clear winners emerged by the 1920s that enjoyed an economy of scale and resources for efficient mass production. The “Big Three” that dominated for the next half-century was in place: Ford, GM, and Chrysler.

GM and Chrysler/Dodge attacked Ford where he was weakest: the stodgy Model T never changed and its 20 HP engine wasn’t very strong. The Dodge brothers introduced the 35 HP all-steel unibody chassis Model 30 Series, which became a favorite of moonshiners during Prohibition. General Motors pioneered hydraulic brakes and electric starters while Ford stuck with mechanical brakes (friction) and the hard-to-use hand crank until 1919. GM excelled at planned obsolescence, introducing different colors and yearly model changes into a sector that suffered from too much durability. If Ford sold practicality, GM under Alfred P. Sloan marketed the aspirational. To maintain status, upwardly-striving Americans could dream of moving up the chain from Chevy to Cadillac. The other two companies followed GM’s tier business model, with Ford adding Mercury and Lincoln on top while Chrysler slotted Dodge and Plymouth below.

GM and Chrysler/Dodge attacked Ford where he was weakest: the stodgy Model T never changed and its 20 HP engine wasn’t very strong. The Dodge brothers introduced the 35 HP all-steel unibody chassis Model 30 Series, which became a favorite of moonshiners during Prohibition. General Motors pioneered hydraulic brakes and electric starters while Ford stuck with mechanical brakes (friction) and the hard-to-use hand crank until 1919. GM excelled at planned obsolescence, introducing different colors and yearly model changes into a sector that suffered from too much durability. If Ford sold practicality, GM under Alfred P. Sloan marketed the aspirational. To maintain status, upwardly-striving Americans could dream of moving up the chain from Chevy to Cadillac. The other two companies followed GM’s tier business model, with Ford adding Mercury and Lincoln on top while Chrysler slotted Dodge and Plymouth below.

Ford stubbornly refused yearly model changes at first, even firing advisors who suggested it. As for paint, he once said customers “could have any color they’d like as long as it was black” (that dried faster). Henry shot down and ridiculed Edsel’s ideas and Knudsen left for GM in 1924. Finally, by 1927, Ford discontinued the Model T and diversified into the revived Model A, built at River Rouge with an electric starter and available in a range of colors on installment plans. Edsel (right) designed the Model A and widened the valves to give it 40 HP but Henry took the credit and resented his son’s contribution. GM experimented briefly with the more powerful eight-cylinder engine, but Ford was first to mass-produce the iconic V8 in 1932. By now, he’d also publicly recanted his anti-Semitism because, as he un-remorsefully explained on his deathbed, “too many Jews were driving Chevys.” In his last interview in 1947, he said, “I’ll take my factory down brick by brick before I’ll let any Jew speculators get stock in the company.”

Ford stubbornly refused yearly model changes at first, even firing advisors who suggested it. As for paint, he once said customers “could have any color they’d like as long as it was black” (that dried faster). Henry shot down and ridiculed Edsel’s ideas and Knudsen left for GM in 1924. Finally, by 1927, Ford discontinued the Model T and diversified into the revived Model A, built at River Rouge with an electric starter and available in a range of colors on installment plans. Edsel (right) designed the Model A and widened the valves to give it 40 HP but Henry took the credit and resented his son’s contribution. GM experimented briefly with the more powerful eight-cylinder engine, but Ford was first to mass-produce the iconic V8 in 1932. By now, he’d also publicly recanted his anti-Semitism because, as he un-remorsefully explained on his deathbed, “too many Jews were driving Chevys.” In his last interview in 1947, he said, “I’ll take my factory down brick by brick before I’ll let any Jew speculators get stock in the company.”

Automobiles came to occupy a similar place in the American economy that trains had earlier. Cars and trucks were not only big businesses for manufacturers and dealers, they also provided markets for steel, rubber, oil, gas, upholstery, mechanics, and road builders. That fact made news in 2009 as the government debated bailing out General Motors. For every job at GM, there were ten more from companies feeding into GM. After the 1920s, cities built suburbs around highways, shopping malls went up at highway intersections, and drive-in restaurants, theaters, and dry cleaners sprouted up along roads lined with billboards. In California, the first drive-ins were A&W Root Beer stands. Better roads and cars gave rise to family vacations that had previously been limited to train routes. Dating habits changed, despite Ford shrinking the Model T’s backseat to restrict procreation. Cars ushered in modern American life. Most cities had streetcars early in the twentieth century but, outside of Chicago and the East Coast, where density made subways and urban rail practical, cities abandoned or tore up most tracks and replaced them with highways as Americans came to favor cars and trucks. Buses filled in the gaps for other commuters. The state and federal governments taxed gasoline to pay for a new system of bridges and paved highways made of concrete or asphalt, a sticky petroleum by-product mixed with gravel.

L-R: Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, President Warren G. Harding, and Harvey S. Firestone, 1921, NYT Photo Archive

Los Angeles was the most notorious and influential example of car culture, where a city, or series of cities in their case, destroyed mass transit infrastructure in favor of freeways. Critics since have bemoaned the L.A. Streetcar Conspiracy because the city took money from GM and oil and tire companies, and GM actually bought the trains to destroy them. But the public was trending in that direction anyway, as people preferred the freedom cars afforded them. Later, freeway and street congestion and limited parking offset the freedom of cars, so western cities like L.A., Portland, Seattle-Tacoma, Denver, Dallas, and Phoenix scrambled to rebuild the mass transit they’d taken out earlier in the 20th century. Cars also created a small industry in racing. By the 1920s, each Memorial Day weekend over a 100k spectators gathered for the Indianapolis 500 (we’ll hear about Daytona below).

As mentioned, we’ll revisit Ford when examining World War II. Before that, novelist Aldous Huxley depicted a world converted to “Fordism” in his dystopian Brave New World (1932). His new World State is centered on mass production, standardization, and consumption, with time measured in A.F. for after Ford and people exclaiming “By Ford!” in reference to their creator. The Christian crucifix has been lopped off to form a T, as in Model T. Unlike George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), that depicts a totalitarian government, Huxley’s World State placates and modifies citizens with drugs and psychological conditioning, manipulating desire rather than inflicting pain. Whereas the government burns books in Orwell’s 1984, there’s no need to in Brave New World because blissed-out, air-headed consumerism has obliterated any desire to read.

Entertainment

Ford influenced other industries, like Harley-Davidson motorcycles, Hershey Co. chocolate (eventually 25 million Kisses® per day), Coca-Cola, Wrigley gum, and Max Factor’s makeup. All applied mass-production assembly line systems and built global businesses, and all had five-day, 40-hour weeks and paid fair wages in a safe workplace. Hershey recycled George Pullman’s old idea of a nice company town, with schools, churches, parks, sports arena, country club, and zoo. He sold mass-produced chocolate to middle-classes that hadn’t been able to afford it the same way Ford had with cars. In Pittsburgh, Heinz offered healthcare insurance, starting the employer-funded model that went mainstream during World War II and continues today with mixed results.

With improved working conditions and fewer hours, a new consumer market for mass entertainment emerged in the 1920s. The years after WWI saw the convergence and maturation of key inventions and industries, including movies, records, and radio, or “wireless.” Motion pictures started to come of age in the 1910s, but the ’20s saw the first large-scale proliferation of theaters. By the early ’30s, they were often air-conditioned at a time when few homes were, making them summer retreats and boosting double-features. Theaters were owned by big companies that churned out movies on an assembly line of their own called the studio system. The vertically integrated studios not only owned the theaters, they also owned the actors, in a sense, whom they kept under contract. Stars rarely branched out on their own with talent agencies until after WWII.

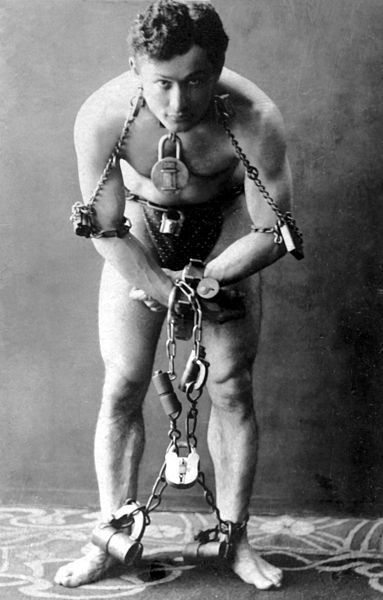

The 1920s saw the first generation of movie stars, most notably Mary Pickford and comedians Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. All movie buffs should see Keaton classics Sherlock, Jr. (1924) and The General (1926). By 1927, engineers discovered how to merge film and sound, creating the first talkies and driving many actors whose accents didn’t fit the WASP ideal out of business. Movie stars weren’t the only ones who could be filmed. Film magnified the advantage of performing unlikely feats like walking on a trapeze wire, escaping out of a coffin thrown into a river, or flying stunts. Keaton also did his own hair-raising stunts. The dancers doing the Charleston on a skyscraper beam we mentioned at the top of the chapter wouldn’t have risked their lives if they weren’t showing off for a camera. Escape artists like Harry Houdini, a poor immigrant, made a living by daring escapes, but it wouldn’t have paid the bills or attracted live audiences for upcoming stunts if film hadn’t spread his feats to millions.

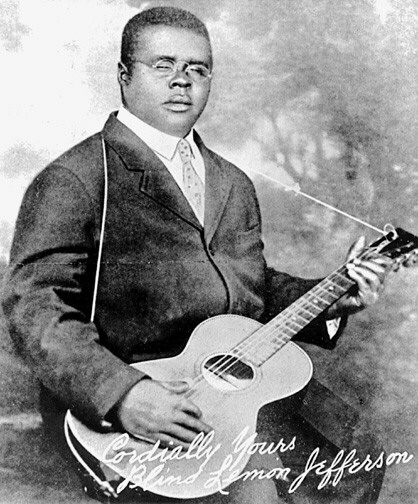

Radio had an equally big impact after improvements in vacuum tube technology, later applied to early television. By 1930, 60% of Americans owned a radio, transforming sports, entertainment, and, as we’ll see in coming chapters, politics. Soap operas, now associated with TV, started on radio in the 1920s. Radio brought large spectator sports like baseball, prizefights, horse races, and college football into Americans’ living rooms for the first time. By increasing interest in sports, radio paradoxically led to greater attendance at live events. Broadcasting the 1921 World Series between the Giants and Yankees, for instance, boosted attendance at ballparks the next year. Prior to radio, only people in big cities who went to games ever experienced major league baseball and there were no big-league teams in the South or West. Everyone else had to follow box scores in newspapers the next day and boys collected player cards from cigarette boxes. Radio and advent of the home run fence re-energized an already popular game, turning stars like the Yankees’ Babe Ruth into household names. Ruth’s notorious drinking and womanizing symbolized the decade’s trademark hedonism. In St. Louis, KMOX’s 50k-watt AM transmitter broadcast Cardinals games across the Midwest and as far south as Texas, creating a regional fan base.