“You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.” — Leo Tolstoy

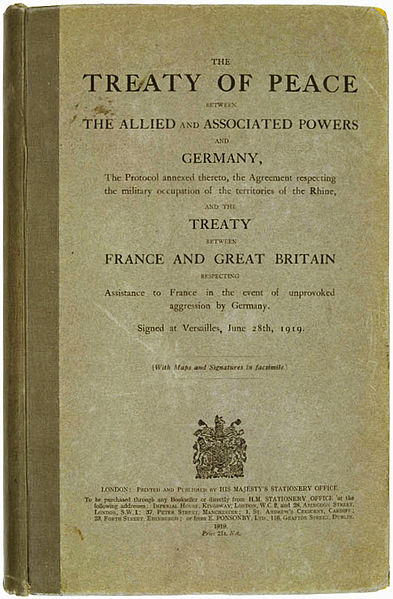

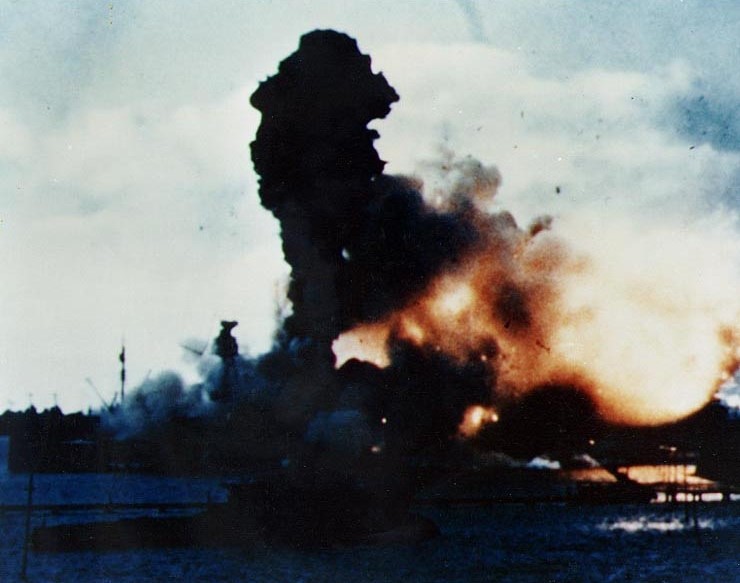

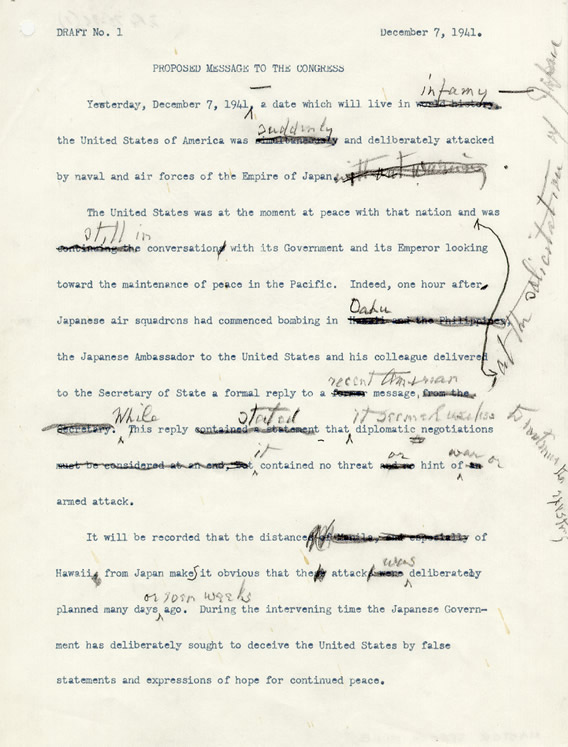

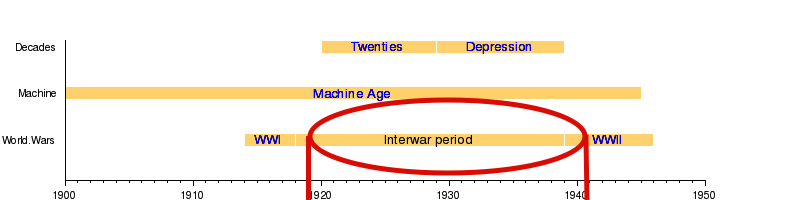

After the 1919 Versailles Treaty ended World War I, there was an understandable push to prevent a major war from ever happening again. In hindsight, though, this Long Armistice was just a break from fighting before World War II, which in the United States’ case started with Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in 1941. The conflict started earlier in Asia (1937) and Europe (1939). How did the armistice come unraveled? For one, the dedication to peace among most countries allowed aggressive ones like Japan and Germany to get away with more than they otherwise would have. That appeasement is a typical starting point in many interwar accounts. The non-aggressor nations also weren’t able to provide an effective international framework of their own between the wars. Britain led prior to World War I and the U.S. after World War II, but no one country stepped up between the wars to maintain stability.

Once the world economy started to crumble in the late 1920s, nations reverted to protectionism instead of reaffirming open trade agreements. The U.S. reinstated tariffs as global trade stalled, forcing American allies to rely on Germany repaying them their debt. As we saw in Chapter 8, the U.S., Britain, and Europe remained yoked together under tight monetary policy tied to the gold standard, inhibiting stimulus spending when the Depression set in. Congress passing the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in 1930 only made things worse.

In the United States’ case, that inward economic turn matched their diplomatic isolationism. Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations never gained effective traction and didn’t grant itself the authority to intervene militarily or economically. The U.S. didn’t join the League even though its president, Woodrow Wilson, founded it (see cartoon, below). America’s League opponents weren’t mere reactionaries; they made a solid isolationist case that membership over-committed the U.S. to intervene all over the world in conflicts that didn’t really concern Americans. That being said, the American boycott weakened the League and helped prevent it from being able to counter Japan or Germany. As we’ll see, a multitude of factors was to blame for World War II and they unfolded in two distinct regions. Japanese and German militarization created two simultaneous threats in Asia and Europe. While the two theaters overlapped and influenced each other, we’ll divide our discussion of the run-up to WWII geographically.

Gap in the Bridge (Cartoon About Absence of the USA From the League of Nations), Depicted as the Missing Keystone of the Arch, w. Cigar Symbolizing Uncle Sam Enjoying Wealth, Leonard Raven-Hill, Punch Magazine, 1919

WWII In Asia

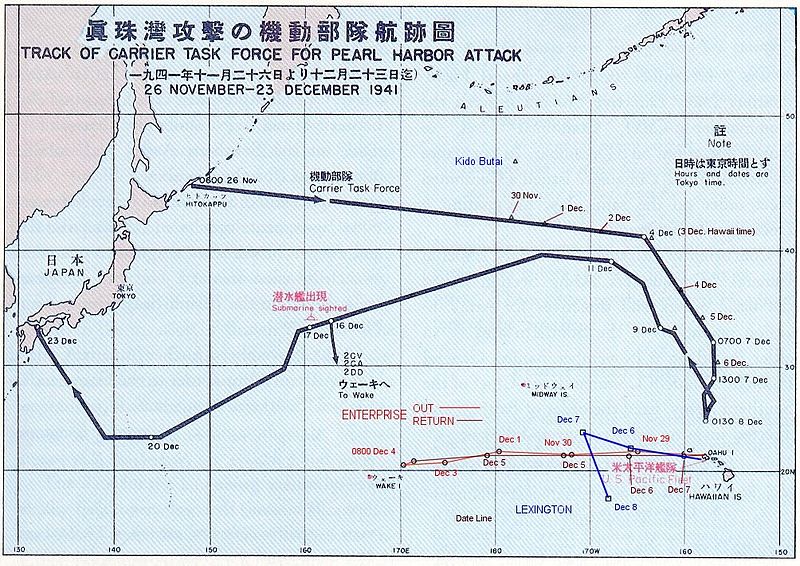

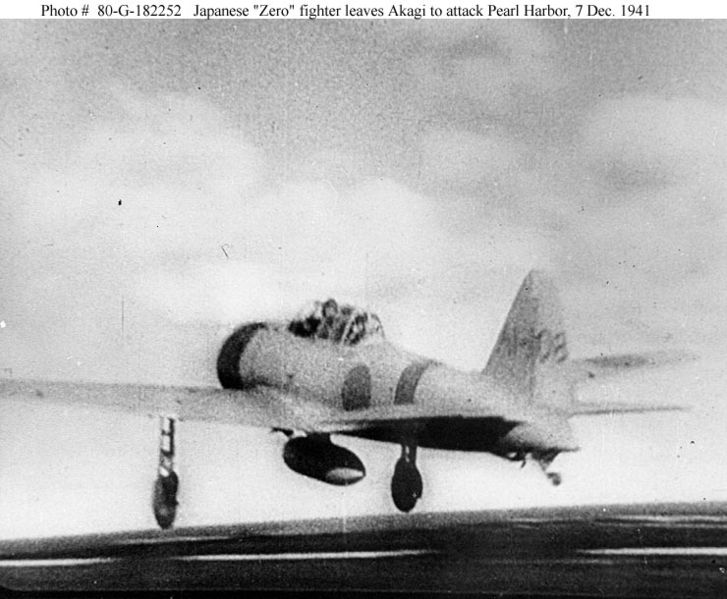

In Asia, the U.S. and Britain were leery of Japan’s rapid industrial and military buildup. During WWI, the Japanese took advantage of Europe’s preoccupation and their alliance with Britain to expand their holdings in the Pacific, especially at the expense of Germany. At the Washington Naval Conference after the war, Japan agreed to freeze the proportion of their battleship tonnage in relation to Britain and the U.S. at a 3-5-5 ratio (unlike Japan, the U.S. and Britain had to maintain two-ocean navies). However, nobody anticipated the advent of aircraft carriers (aka flat-tops), which weren’t included in the agreement. Restrictions on traditional capital ships only motivated the U.S. and Japan to put more money and research into carriers. Likewise, the Versailles Treaty’s restrictions on traditional armaments only motivated Germany to research rocketry. The U.S. also started a special Air Corps within the Army that became the Army Air Force (USAAF) and branched off into the Air Force after World War II, and they trained pilots in the Navy/Marines. While planes didn’t have a huge impact on the outcome of WWI, they evolved to the point that everyone could see that future wars would be won or lost in the air. After WWI, the U.S. also scrapped over half its aging naval fleet and shrunk its standing army down to 136k.

Regardless of how many carriers or planes they built, Japan was slamming shut the Open Door Policy that had kept China’s spoils evenly divided amongst Japan and the West since the late 19th century. Just as the U.S. claimed all the Western Hemisphere as its sphere of influence starting in the 1820s, Japan now countered the American Monroe Doctrine and Roosevelt Corollary with the euphemistically-named Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Translation: Japan was taking over Asia. They were following the same logic Alfred T. Mahan had laid out for the U.S. in the 1890s in terms of acquiring overseas territories (markets) and building a strong navy to fuel domestic industry (Chapter 3). Mahan based his theories on Britain’s rise to maritime and naval prominence and the British model, not America’s, fit Japan best. Like England, Japan was a small island country and had even fewer natural resources (some coal), but they hoped to dominate the western Pacific economically with a superior navy. They conquered Okinawa and the remaining Ryukyu Islands in 1879 and they coveted raw materials on the Chinese mainland and in Russia’s far eastern territory.

Japanese fed themselves the usual gibberish about God liking them better than others. What else could explain their racial superiority over other Asians? In Japan’s case, Emperor Hirohito lent credence to their version of Manifest Destiny but its Parliament (National Diet) and generals, led by Hideki Tōjō (prime minister starting in 1941), pursued military expansion most aggressively. There was an internal debate about the government’s direction and militarists asserted greater control and took charge after the 7.9-magnitude Kantō Earthquake that destroyed Tokyo in 1923, killing over 140k. Touting order after the disaster, they kept communism and republicanism at bay, moving the country toward fascism. By the 1920s, Japanese schools were denigrating the Chinese. Religious chauvinism and racism provided ideological frosting on the cake, with the main goal being economic growth.

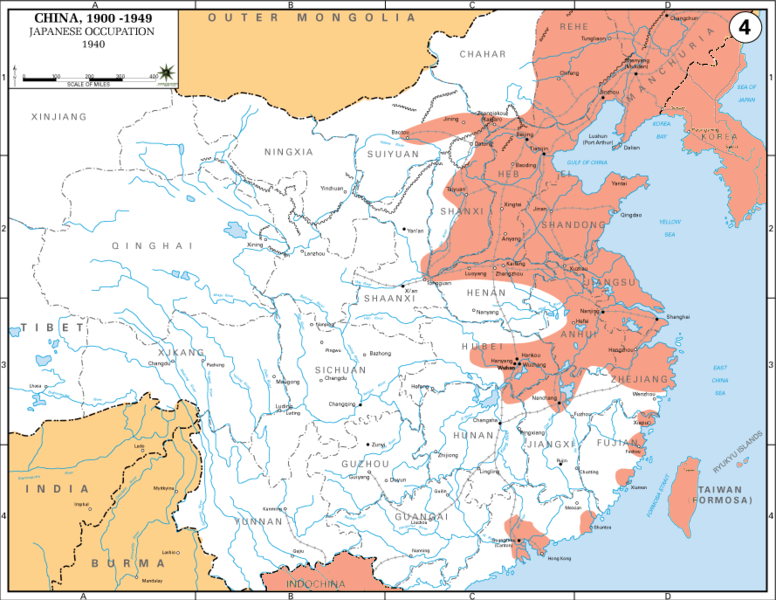

Unlike Europeans, Japanese weren’t haunted by memories of the Great War. They’d profited from WWI by acquiring German islands in the Versailles Treaty and their last major war was a happy memory: victory over Russia in the northwest Pacific in 1905. Now, the extension of Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok was threatening Japan’s potential control of Manchuria in northeastern China. But their expansion began earlier, closest to home in the Ryukyu Islands in 1879, that they renamed Okinawa. In 1895, Japan laid claim to the iron and coal-rich Korean Peninsula and Taiwan (then Formosa) in the First Sino-Japanese War against China’s Qing Dynasty. They annexed Korea in 1910. In 1931, hoping to offset the Depression, Japan took over Manchuria, a mineral and coal-rich area with good soil for soy and barley. Roundly condemned by foreign statesmen for this act of naked aggression, the Japanese walked out on the League of Nations, but the League didn’t act to stop their Manchurian invasion. Smaller skirmishes with China ensued from 1932-37 and, while the U.S. sold them oil, scrap metal, and steel, Japan conquered most of China in 1937 in the Second Sino-Japanese War, kicking off World War II in the Pacific with attacks on Peking (Beijing) and Shanghai.

Following the “Three Alls” motto, Japanese forces were instructed to “kill all, loot all, burn all” in a scorched-earth campaign. They raped, poisoned, and brutalized Chinese civilians on a massive scale, just as they soon would throughout Asia. At Nanjing, they slaughtered so many in six weeks that they faced logistical challenges dealing with the corpses and eventually had to force Chinese survivors to bury the body parts themselves or to walk into their own graves to be buried alive. The leader of Japan’s secret service in Shanghai said, “we can do anything to such creatures.”

Tragically, China inadvertently killed half a million of its own people when they opened the floodgates on the Yellow River in an attempt to stop the Japanese invasion. Fifteen million Chinese died in the eight-year war against Japan but they never capitulated. Japan eventually got bogged down in China, especially after Soviet troops defeated them in Outer Mongolia in the Battles of Khalkhyn Gol in 1939. If they hadn’t, they might not have looked to the southwest Pacific for oil in 1941, bringing them into conflict with the Americans and British, about which more later. Before Khalkhyn Gol, the army had preferred the northern approach whereas the navy coveted oil and rubber toward the south, including French Indochina (Vietnam) and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia).

Chemical Warfare in the Sino-Japanese War, Hunan Front Near Changsha, 1941, Cabinet Printing Bureau of the Empire of Japan

The U.S. feigned some disapproval over the 1937 Japanese invasion of China but wasn’t put off enough to discontinue feeding the war machine. America was in a depression and needed the money. Japan then slowly encroached further and further across Asia, taking over French-held Indochina (Vietnam, Laos & Cambodia) in 1940. At that point, the U.S. was concerned for its own oil interests in Indonesia and cut Japan off from oil, scrap metal, and steel, demanding that they retreat out of Indochina. We’ll revisit Asia below after first examining Europe between the wars.

Weimar Germany

History is full of mistakes that leaders and nations would correct if only they could rewind the clock. The punitive treatment of Germany at the end of WWI is an obvious example — one we’ll see that the U.S. learned from and corrected after WWII. Of course, we don’t know for sure that Germany wouldn’t have caused problems for the rest of Europe even if they’d been dealt more generous terms at the Versailles Peace Conference. Drawing a simple, straight line from the Great War to Nazi Germany is overly deterministic, given that nearly fifteen years transpired in between. But martyrdom and vengeance fueled the Nazis’ rise. It’s impossible to understand Nazism without understanding the context of WWI. Instead of that bloodbath being the “war to end all wars,” as advertised, critics called its concluding Versailles Treaty the “peace to end all peace.”

While Germany’s invasion of Belgium in 1914 was rightfully condemned as worsening an already volatile situation, it was unfair that Germany was singled out and blamed for the Great War. Austria, for one, could’ve dealt with the Archduke’s assassination without punishing the entire Serbian population for the actions of the Black Hand terrorists (Serb army) and Britain could’ve stayed out altogether. As we saw in the Great War chapter, American diplomats inserted the so-called War Guilt Clause regarding Germany, despite President Woodrow Wilson’s initial promise of lenient terms. Others have argued that the clause mentioned no such thing and that Germans played up the guilt factor to elicit international sympathy. The text reads: “The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.”

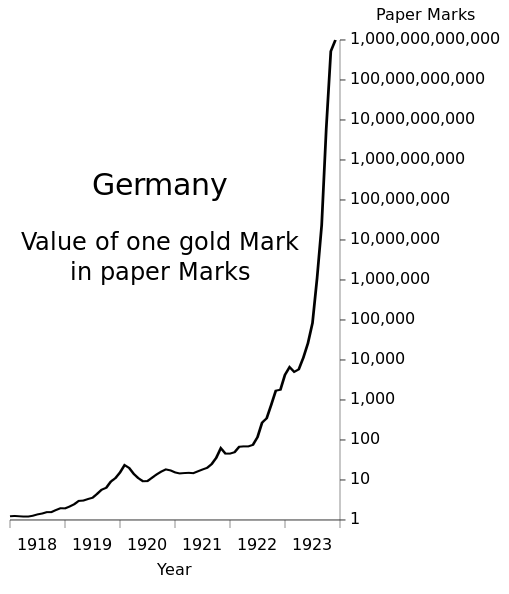

Between August and November 1923, a U.S. Dollar Went From Being Worth 630,000 Deutsche Mark to 630 Billion DM.

All the losers, not just Germany, got the blame. Either way, it was unrealistic, unfair and counterproductive to expect Germany to pay the victors’ debts. Kaiser Wilhelm had to abdicate his throne, they destroyed their submarines, planes, and battleships, and Germany gave up territory in the west to France and east to the reconstituted country of Poland along with overseas colonies in the Pacific and Africa. Adding insult to injury, the Allies embargoed Germany for another year-and-a-half, ostracizing them just when Western Allies should’ve been propping up the struggling democracy that ruled the country in the 1920s. The Weimar Republic (or Deutsches Reich), named after the city in Germany where the new constitution was written, practiced a form of government that Britain and the U.S. should’ve been supporting since they had a stake in displacing other options. Instead, the Weimar Republic struggled to get out from under the Versailles Treaty restrictions. They experienced hyperinflation in the early 1920s due to the German Mark’s devaluation (especially in relation to the British pound), recovered briefly, and then sank into a depression that exacerbated the worldwide 1930s slowdown.

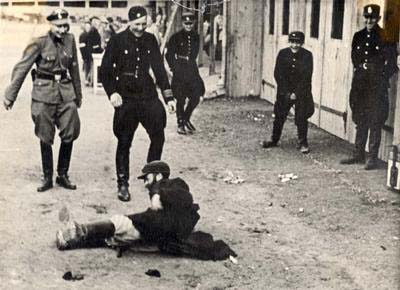

When Germany fell behind on its payments from 1923-25, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr Valley in northern Rhineland, Germany’s industrial heartland, demanding coal and steel to pay off their debt. Coal shortages triggered German inflation and Nazis filmed French soldiers kicking around Germans who failed to doff their caps and killing uncooperative miners and factory workers. The humiliation of the Ruhr Valley occupation played directly into Nazis’ hands as they recruited resentful Germans in nearby Bavaria.

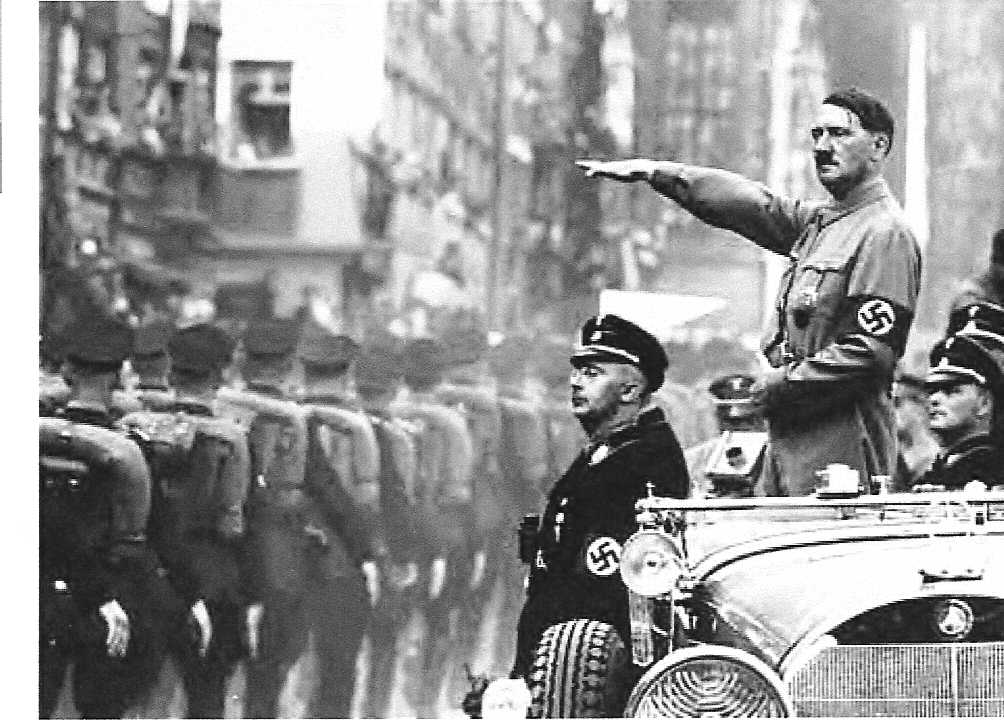

Hitler @ Nuremberg Rally, 1928, National Archives Collection of Foreign Records Seized, Heinrich Hoffman Collection

Germany’s erratic economy also played into Nazis’ hands. The U.S. restructured Germany’s debt under the 1924 Dawes Plan that staggered their payments, tied repayment to productivity in the German economy, and extended the reparation deadline. But Germany was still mainly borrowing from private U.S. lenders to pay off its debt to the U.S. government. Dawes also called for the withdrawal of Allied troops from the Ruhr Valley. That temporarily resolved Germany’s economic crisis and led to a brief rebound. However, the U.S. wouldn’t forgive Britain or France their debts, so those countries needed Germany’s full payments to repay America. Ultimately, the U.S. lent to Germany and the reparations just cycled back to the U.S. via Britain and France. Germany’s economy was tethered to Western countries as they experienced their own downturns. The American Dawes Plan gave way to the 1929 Young Plan, that reduced the amount owed by 20% down to 122 billion Gold Marks (around $8 billion 1929 dollars or ~ $100 billion today), with the final installment due in 1988. These measures didn’t suffice, especially after the American Stock Market Crash and Smoot-Hawley Tariff contributed to a worldwide slowdown. President Herbert Hoover declared a one-year moratorium on German debt in 1931 but that didn’t help much, either. Adding fuel to the fire — in a precursor to the Credit Default Swaps that got the world in trouble in 2008 — by 1931, Britain’s top investment banks had sold credit guarantees to investors in German debt. When Germany defaulted the British government went from surplus to debt as they bailed out their financial sector.

The Weimar Republic had political problems as well. Its constitution muddled the relationship between the chancellors, presidents, and Reichstag (Parliament). It allowed leaders to rule without Parliament’s consent in an emergency but didn’t clearly define emergency. Germany had a multi-party democracy, with each party winning seats in the Reichstag proportional to their percentage of votes. The center didn’t hold under World War I general and 1920s President Paul von Hindenburg. In the 1928 elections, the Nazis won less than 3% of votes, but WWI flying ace Hermann Göring (Gestapo founder and Luftwaffe head) and Joseph Goebbels (Nazi Propaganda Minister) won seats, and Goebbels later said they entered Parliament like “wolves into the sheep’s pen.” Democracy offers a portal through which fascism can enter insofar as true political freedom allows for extremism and free speech allows for disinformation. Goebbels gloated, “this will always be one of the best jokes of democracy — that it gave its deadliest enemies the means by which it was destroyed.”

Rise of Nazis

Like all European countries where monarchies fell at the end of WWI, Germany was volatile afterward as factions competed to fill the vacuum. The three main options were democratic capitalism (republicanism, classical liberalism), communism, and fascism — a jingoistic form of dictatorship that compels allegiance to a militaristic state, including by corporations. Fascism promotes order, racial superiority, and militarism. Fascism includes a cult of personality around a particular leader who advertises himself as the sole solution to a nation’s problems, encourages violence among followers toward scapegoats, undermines trust in liberal institutions like elections, courts, and free press, lies incessantly while accusing others of lying (to the point his followers no longer recognize truth), employs racism and victimization in grievance politics (often with promises of vendettas), and sees himself as above the law. Historian Robert Paxton offers this definition:

Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.

Since fascism promises to get rid of democracy’s inefficiency, argumentation, and messiness, it’s appealing to countries undergoing the sort of trauma Germany was suffering in the late 1920s and early ’30s. Neighboring Italy also struggled after WWI. Its dictator, Benito Mussolini, defined fascism as “the state which educates its citizens in civic virtue, gives them a consciousness of their mission, and welds them into unity.” Mussolini manufactured chaos than capitalized by offering stability. Violence and disorder from his own street militias convinced King Victor Emanuele III to deny aid to Prime Minister Luigi Facta and appoint Mussolini after Facta resigned.

Adolf Hitler’s paramilitary group, the Nazis, was one group promoting fascism in Germany. Economically, the Nazis didn’t fit easily into the traditional right-left spectrum. Their full name was the National Socialist German Workers Party, implying a left-leaning stance, but Nazis hated communists and considered them their arch enemies along with Jews (the term Nazi predates this era, referring to backward farmers, and was first applied by opponents). The dislike between communists and Nazis was mutual as early as 1929, indicated by a scene from the classic silent documentary Man with a Movie Camera, in which a young Soviet woman takes aim at a Swastika in a carnival shooting gallery. After WWI, Hitler was an army spy who ferreted out communists. On the other hand, Nazis claimed at first to hate the crassness of capitalism and the red in their flag represented a peoples’ movement; they were populists who appealed to the masses. Their early platforms included pension funds for senior citizens. And Lenin’s totalitarianism no doubt influenced Hitler and Mussolini. One complication for Hitler economically was that his special army of street thugs, the Brownshirts (or Sturmabteilung aka SA), were anti-capitalist, but industrialists like steel magnate Fritz Thyssen and Henry Ford eventually bankrolled the Nazis’ rise to power, along with gold confiscated from Jewish bankers. When that tension became irreconcilable by 1934, Hitler had the SS murder left-wing factions (Strasserists) and Brownshirt/SA leaders on the Night of the Long Knives and the capitalists took control. Industrial monopolies in steel, rubber, and coal supported Hitler and helped bring him to power. In Italy, Mussolini described fascism as a “merger between state and corporate power.” The Night of the Long Knives marked the ascendance of the SS over the SA and commenced the systematic castration and imprisonment of homosexuals.

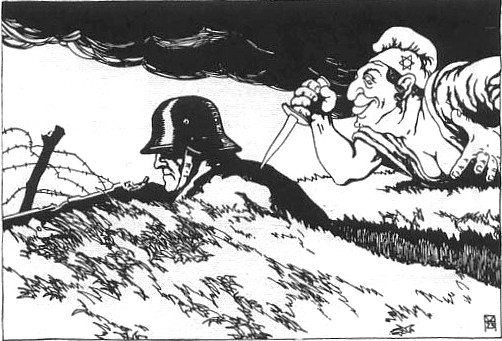

Hitler had fought for Germany rather than his native Austria in WWI because of his admiration for Germany. He reinvented himself there after his rejection to art school resulted in him living like a bum on Vienna’s streets prior to the war. Corporal Hitler loved the trenches and sanctioned killing of the Great War, in which he won the Iron Cross for his dangerous work as a courier. Like some others in the military, he despised the “November criminals” who capitulated to the Allies in the armistice that ended the war. The Nazis’ stab-in-the-back myth, or Dolchstoßlegende — an extreme example of grievance politics — blamed a cabal of Marxists, Jews, and republicans for overthrowing the Hohenzollern monarchy at the end of WWI, giving up the fight even though Germany wasn’t defeated. This distorted legend underestimated the extreme pressure Germany’s military and economy were actually under by the fall of 1918. The German Revolution of 1918-19 did replace the monarchy with the Weimar Republic, but Germany gave up for a reason.

Hitler interpreted his numerous escapes during WWI as a sign that God had singled him out for the divine mission of running Germany. He was convalescing from a mustard gas attack when the war ended and may have suffered a groin injury at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He often recounted his miraculous recovery at a Berlin hospital, when he regained his sight and had a vision of Jews stabbing the German eagle. As specialists in hate, there was plenty more room under the Nazi tent for others besides Jews and communists, including Gypsies (Romani), Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, and disabled, all of whom they wanted exterminated.

Hitler and a band of former generals, including Erich Ludendorff, tried but failed to take over Munich in 1923 in the Beer Hall Putsch, after which Hitler was arrested. His eloquent and passionate trial defense increased his notoriety, though. He won over a portion of the jury and, rather than being executed, he got five years in comfortable house arrest. There, he dictated Mein Kampf, or My Struggle, to editor Rudolph Hess, condemning the Versailles settlement and blaming Germany’s small Jewish population for problems in banking and their potential to bring about communism (Lenin was ¼ Jewish). Banking and communism aren’t generally grouped together for obvious reasons but, in Hitler’s mind, both were at fault. Jews had controlled much of Germany’s gold, but mainly because it was illegal for them to hold currency. As mentioned, Nazis confiscated much of it, using it to finance their military. Swiss banks laundered stamped Jewish bullion for the Nazis.

Mein Kampf didn’t sell well at first, as Hitler was mostly forgotten in the mid-1920s because fascist groups were still marginal. After the Stock Market Crash of 1929 worsened Germany’s economy, Hitler’s message of order and violence resonated among a critical balance of those suffering from hunger and inflation and they intimidated many others. He made it compulsory reading after he seized power in 1933 and the royalties made him rich. Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf, “Only the application of brute force used continuously and ruthlessly can bring about the decision in favor of the side it supports.”

The Nazis’ popularity rose to ~ 20% after the Stock Market Crash in 1929. By the early 1930s, the chancellors (appointed by the president) were overriding the Reichstag, culminating in Chancellor Hitler. No one party was able to establish clear rule and the far left and far right challenged the Republic’s existence upheld by centrists: Social Democrats (SPD) and the Catholic Center Party, or Zentrum. Nazis won ~ 37% of votes in the 1932 election. Hindenburg, an independent, temporarily dissolved Parliament and named Hitler chancellor in 1933 despite initially opposing him. While Nazis entered power via democracy, the actual naming of Hitler as chancellor resulted from a backroom deal as Germany’s economy went into a tailspin in early 1933, not an actual election. Nazi Storm Troopers fought communists in the streets prior to the 1932 elections while Hitler campaigned tirelessly, averaging five speeches a day. By then, Nazis constituted a plurality in the Reichstag if not an actual majority, polling especially well in cities and among rural Protestants in the north. Meanwhile, Hitler dismissed media critical of him as luginpresse, or “lying press.” In short, Nazis came to power through a combination of democratic elections, media manipulation/propaganda, warped history, and street-level intimidation. Hitler still seemed like a marginal nutcase to most by 1928 when Germany’s economy was on the mend, but after the 1929 Crash left six million unemployed (24%) the public yearned for order amidst the chaos. Order was the Nazis’ specialty, or at least their promise.

The Nazis’ popularity rose to ~ 20% after the Stock Market Crash in 1929. By the early 1930s, the chancellors (appointed by the president) were overriding the Reichstag, culminating in Chancellor Hitler. No one party was able to establish clear rule and the far left and far right challenged the Republic’s existence upheld by centrists: Social Democrats (SPD) and the Catholic Center Party, or Zentrum. Nazis won ~ 37% of votes in the 1932 election. Hindenburg, an independent, temporarily dissolved Parliament and named Hitler chancellor in 1933 despite initially opposing him. While Nazis entered power via democracy, the actual naming of Hitler as chancellor resulted from a backroom deal as Germany’s economy went into a tailspin in early 1933, not an actual election. Nazi Storm Troopers fought communists in the streets prior to the 1932 elections while Hitler campaigned tirelessly, averaging five speeches a day. By then, Nazis constituted a plurality in the Reichstag if not an actual majority, polling especially well in cities and among rural Protestants in the north. Meanwhile, Hitler dismissed media critical of him as luginpresse, or “lying press.” In short, Nazis came to power through a combination of democratic elections, media manipulation/propaganda, warped history, and street-level intimidation. Hitler still seemed like a marginal nutcase to most by 1928 when Germany’s economy was on the mend, but after the 1929 Crash left six million unemployed (24%) the public yearned for order amidst the chaos. Order was the Nazis’ specialty, or at least their promise.

After Nazis claimed victory in disputed 1933 elections, they set about dismantling the democracy that had brought them to power. In the euphemistically titled Law to Remedy the Distress of the People, or Enabling Bill, they outlawed future elections. The Burning of the Reichstag (Parliament building) was the key pretext for Nazis suspending republicanism (voting and civil liberties) and eradicating communists at the same time, killing two birds with one stone. They blamed a Dutch communist for the fire and beheaded him while non-Nazis (and most historians) suspected the Nazis themselves of arson in a false-flag operation. To this day, the term Reichstag Fire signifies a power grab whereby leaders manufacture a crisis or exploit a real one to blame opponents, distract citizens, or convince citizens to surrender liberties (e.g., the Japanese far-right exploited the 1923 earthquake, even though they didn’t manufacture that crisis, and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán did likewise in his “Coronavirus Coup”). Nazis won more parliamentary elections shortly thereafter, giving them an outright majority rather than a mere plurality, but any semblance of democracy evaporated. Hitler said, “There will be no mercy now. Anyone standing in the way will be cut down.” Nazis thereafter arrested and detained people without pressing charges or allowing them to stand trial and passed the Enabling Bill that, based on a perpetual post-Reichstag “state of emergency,” transitioned Germany into a dictatorship. With the peoples’ support (some polls suggested ~ 90%, though it was risky to voice opposition) Hitler conflated the offices of chancellor and president into Der Führer (leader). Most of those opposed moved west to the Saar, then controlled by France but soon reconquered by Germany.

The Reichstag fire and response intimidated and/or brought on board many middle-class Germans otherwise skeptical of the new regime. Nazis ostracized centrists/republicans (i.e., Social Democrats and Center Catholic Party) as “socio-traitors” for not going along with book burnings, harassments, and heavy-handed tactics. In the Berlin suburb of Köpenick, Sturmabteilung (SA) rounded up hundreds and tortured to death 91 resistant Jews, Social Democrats, communists, and Catholics in the “Week of Bloodshed,” throwing their corpses in the river. Nazis beat prisoners until their kidneys exploded and poured hot tar in open wounds. As one German put it in 1933, “Every day the opposition is tortured with whips and electric drills. Better to celebrate and howl with the wolves.” Those that refused to raise their hand and Heil Hitler (salute) were sent off to the camps with the others.

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out–

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me–and there was no one left to speak for me.

— Martin Niemöller, German Protestant Pastor

Rebuilding Germany

Politically, Nazis despised the disorganized ineptitude of democracies, with their respect for debate and free speech. Fascists could claim that their dictatorships got things done, most famously expressed in the phrase trains ran on time. Hitler implemented a more aggressive Keynesian strategy of stimulus spending than his contemporary Franklin Roosevelt, rebuilding the country and putting people back to work. Relative to GDP, Germany spent about 5x more than the New Dealers and it worked. The Nazis pioneered interstate engineering (four-lane roads, on-ramps/exits, overpasses) in their Autobahn, that they hoped could move their military around the country more efficiently than dirt roads had during WWI. The project actually began under the Weimar Republic but had floundered.

Hitler not only admired Henry Ford’s anti-Semitism, but also the industrial efficiency of his plants, and hoped to jumpstart Germany’s economy with their own car for the common folk, the Volkswagen. Hitler suggested the aerodynamic “beetle” shape to its designer, Ferdinand Porsche, who shared the dream of a car for the people. They invited Ford to Germany and awarded the industrialist the Grand Cross of the German Eagle on his 75th birthday.

Nazis reveled in the country’s economic rebound and patriotic resurgence. They excelled at pageantry, hosting orchestrated public festivals where Germans camped out and celebrated their culture. In huge stadiums, they heard inspiring speeches and showed their allegiance in choreographed, well-documented spectacles. Hugo Boss designed sharp uniforms for the SS and Hitler Youth. Nazis indoctrinated youth and Hitler said that he hoped to see, again, in their eyes “the gleam of the beast of prey.” Hitler Youth and Brownshirts marched to songs adapted from Harvard’s fight song, written by Hitler’s friend and Harvard alum Ernst Hanfstaengl (right). They held Nazi Party Rallies in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) from 1923-1938. Hitler loved film and was at least as adept on the radio as FDR. He took acting lessons and began to excel after the invention of sound film. He studied dramatic gestures in opera and cultivated a domineering persona to better manipulate the masses, of which he said, “they’re feminine and stupid…only emotion and hatred can keep them under control.” Charlie Chaplin called Hitler the best actor he’d ever seen.

Nazis reveled in the country’s economic rebound and patriotic resurgence. They excelled at pageantry, hosting orchestrated public festivals where Germans camped out and celebrated their culture. In huge stadiums, they heard inspiring speeches and showed their allegiance in choreographed, well-documented spectacles. Hugo Boss designed sharp uniforms for the SS and Hitler Youth. Nazis indoctrinated youth and Hitler said that he hoped to see, again, in their eyes “the gleam of the beast of prey.” Hitler Youth and Brownshirts marched to songs adapted from Harvard’s fight song, written by Hitler’s friend and Harvard alum Ernst Hanfstaengl (right). They held Nazi Party Rallies in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) from 1923-1938. Hitler loved film and was at least as adept on the radio as FDR. He took acting lessons and began to excel after the invention of sound film. He studied dramatic gestures in opera and cultivated a domineering persona to better manipulate the masses, of which he said, “they’re feminine and stupid…only emotion and hatred can keep them under control.” Charlie Chaplin called Hitler the best actor he’d ever seen.

The Totenehrung (honoring of the fallen) at the 1934 Nuremberg Rally. SS leader Heinrich Himmler, Adolf Hitler and SA leader Viktor Lutze (from L to R) on the stone terrace in front of the Ehrenhalle (Hall of Honor) in the Luitpoldarena. In the background is the crescent-shaped Ehrentribüne (the Tribune of Honor).

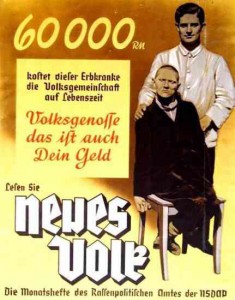

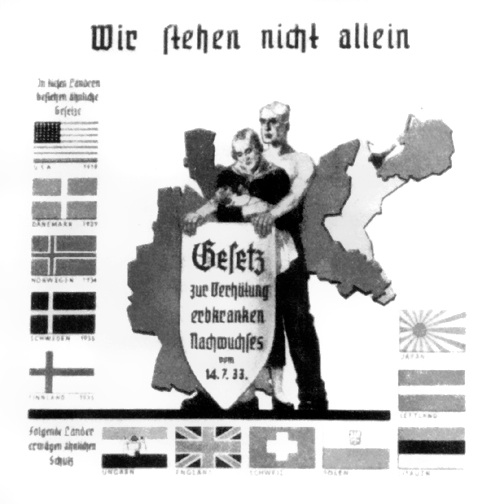

Germany started a breeding program between single women and Nazi officers called Lebensborn to propagate their new super race. Their political agenda started off innocuously in comparison with what came later: instituting prayer in public schools, loosening up gun laws (except for Jews), banning homosexuality, revoking Jewish citizenship, and banning intermarriage between Jews and Gentiles (non-Jews) with the Nuremberg Laws. German Jews were then Jews in Germany, but not Germans. Heinrich Himmler was the main architect of the Final Solution, or what Hitler called “the final solution to the Jewish question:” extermination. Himmler led the top-secret police/paramilitary rung, the Schutzstaffle, or SS.

The first concentration camps opened in 1933 but were mostly kept under wraps. Nazis were thuggish relative to most governments but stayed within the mainstream enough to curry cautious acceptance among fellow Europeans. Jews seemed no worse off legally than minorities in many countries as long as one didn’t know about the camps. Winston Churchill of Great Britain, for instance, appreciated Nazis as a bulwark against Soviet communism; and they were preventing the sort of Bolshevik revolution that happened in Russia in 1917. Nazis salvaged their reputation by curbing inflation and turning around the German economy. When the German Hindenburg airship blew up docking in New Jersey in 1937, Franklin Roosevelt sent Hitler a condolence note from his fishing boat off the Texas coast. The gigantic and infamous Zeppelin (4x larger than the Goodyear blimp) had symbolized Nazi strength at events like the Nuremberg rallies and 1936 Olympics.

1936 Berlin Olympics

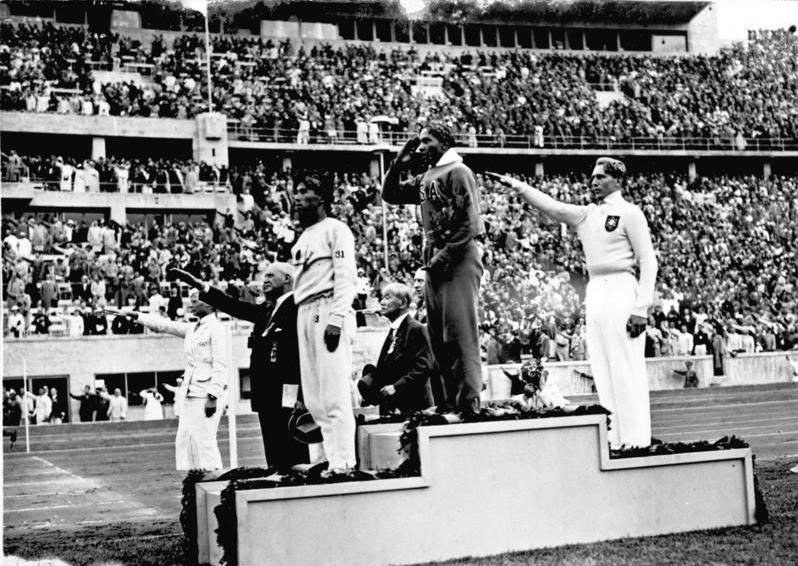

Germany showcased its rebuilt country in the 1936 Olympics. The mere fact that Berlin was chosen for the games signaled their readmission into the international community and tacit approval of fascism. Nazis took full advantage by building the first substantial Olympic village, temporarily taking down anti-Semitic billboards, clearing out Gypsies (Romani), outlawing prostitution, and treating foreign journalists and athletes hospitably. Visitors were oblivious to construction of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp north of Berlin. The sports complex was magnificent by 1930s standards and the same Hindenburg balloon that crashed in New Jersey a year later flew over the main stadium during opening ceremonies. Nazis underscored their connection with the ancient Greek Olympic founders by relaying the torch from Athens to Berlin — a tradition that lives on. Some International Olympic Committee (IOC) members thought Germany was a good choice to host the games because they embraced eugenics, similar to the ancient Greek Spartans’ killing of deformed babies.

Hitler hoped to use the Olympics to prove the superiority of fascist regimes and largely succeeded. Germany, Italy, and Japan did well. Germany finished first in the overall medal count with the U.S. second, and American Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage argued that the U.S. should consider that as a lesson on the upside of fascism. Shortly after those comments, and likely because of them, Brundage became IOC president. But fascists didn’t win every event: African-American Jesse Owens (left) famously humiliated Hitler by winning four gold medals in track & field. The record-breaking sprinter from Ohio St. upset Hitler’s notion of Aryan superiority in front of a packed house and early television cameras. On a promotional tour across Europe after the Games, Owens quit and went home because, with no stipend, he was tired of sleeping in airplane hangers and begging for food. Brundage consequently stripped him of his amateur status and he had to rely on gimmick races against horses and trains. He got a victory celebration at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel but, as an African American, had to take the freight elevator to attend. Since FDR refused to meet with any black athletes, Owens said: “Hitler didn’t snub me — it was [Roosevelt] who snubbed me.”

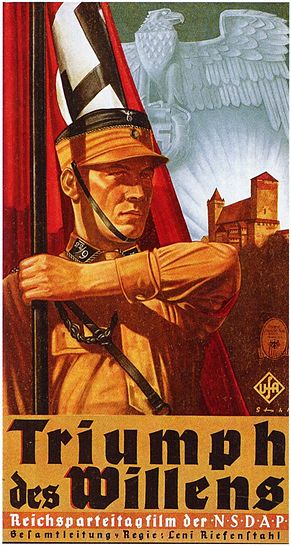

The Olympics bought Hitler time and helped camouflage the Nazis’ real intentions, though the IOC awarded Germany the Winter Olympics in 1940 even after news of the Holocaust had leaked out (those Games were eventually canceled). Documentarian Leni Riefenstahl chronicled the 1936 Olympics and the 1934 Nuremberg Rally in Triumph of the Will. These aesthetically sophisticated films are must-sees for any student interested in propaganda or how the Nazis won over Germans in the 1930s. Riefenstahl was a great filmmaker despite her friendship with Hitler, having pioneered documentaries in the same way that German roadbuilders pioneered freeways.

Expansion

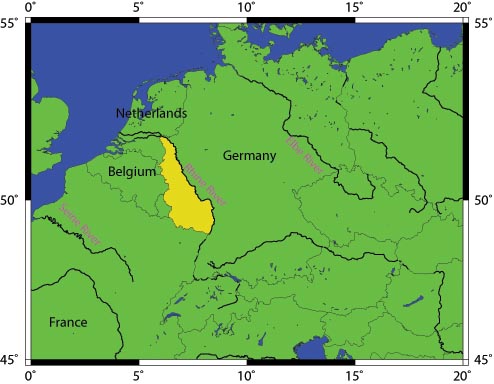

The Versailles agreement barred Germany from maintaining anything but a skeletal defense and most European powers, including Germany, pledged peace and promises of arbitration in disputes to one another in the Locarno Treaties of 1925. But France and the USSR signed a mutual pact in 1935 (similar to 1892), outraging Germany, and Germany was openly violating terms of the Versailles and Locarno treaties by the mid-1930s. Their economic revival wasn’t just based on highways, but also munitions. They made their first expansionary move in March 1936, retaking the Rhineland region ceded to France after WWI. That included the industrially important Ruhr Valley (the Ruhr is a Rhine River tributary).

Hitler actually instructed his troops to turn back if the French challenged them, but no such opposition materialized. Regions like the Saarland voted to rejoin Germany, despite the fact that the French-held areas were refugees for Nazi opponents. The Saarland vote surprised France. Germany claimed the Rhineland takeover was a justified response to the treaty France signed with the USSR, and the Versailles Treaty indeed called for a referendum there after fifteen years.

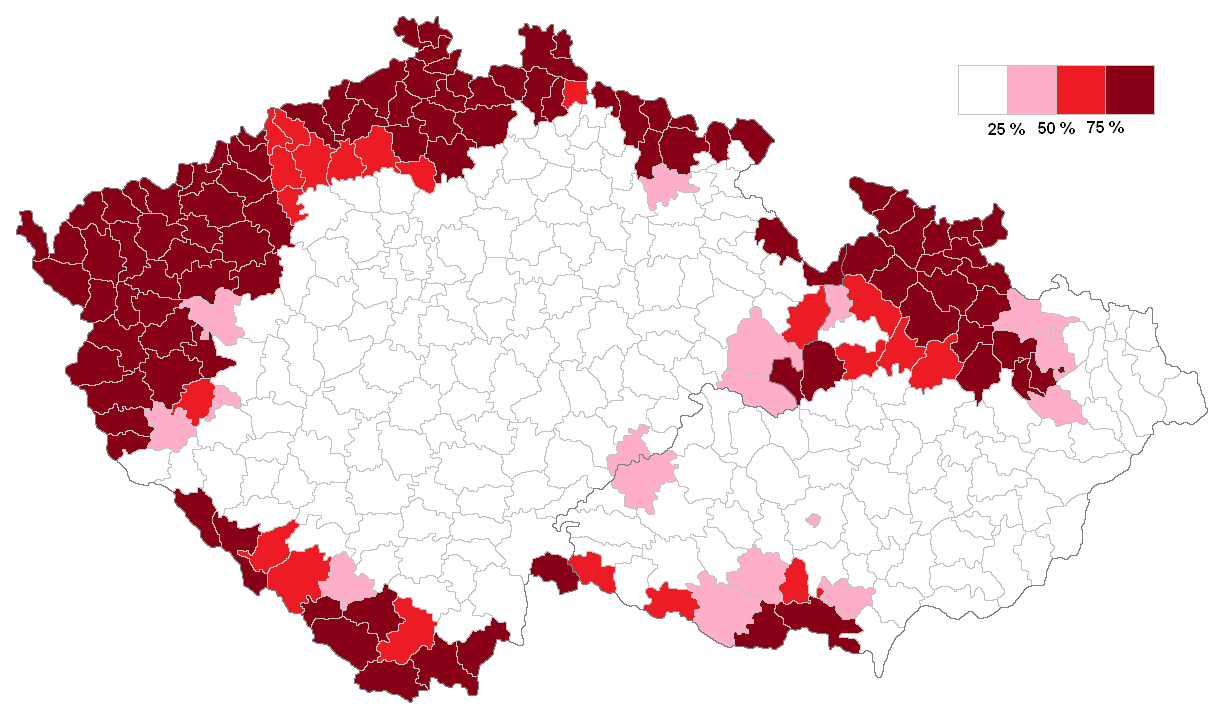

Czech districts with an ethnic German population in 1934 of 25% or more (pink), 50% or more (red), and 75 % or more (dark red) in 1935

Their next move was Hitler’s home country, where Austrian Nazis helped expedite a mostly bloodless takeover called the Anschluss in March 1938. Then, in October 1938, they made demands on the German-speaking Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia, a country created from scratch at Versailles. The Nazis had sympathizers and collaborators in virtually every European country. Most Austrians supported becoming part of Grossdeutschland (Greater Germany). Oswald Mosley was the leading fascist in England. Among the majority of Brits that opposed Mosley, Hitler took advantage of their desire for peace, knowing that he could get away with more than he would have had they not been haunted by WWI. And he took advantage of widespread anti-Semitism throughout the Western world. When WWII broke out, only Denmark, among occupied countries, refused to cooperate with their arrest, instead smuggling Jews in fishing boats to neutral Sweden.

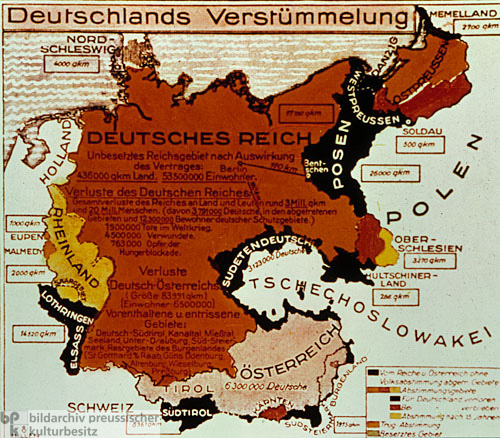

Like every country on the make, Germany was only “defending itself” and its acquisition or reacquisition of German-speaking territory gave that narrative a shred of truth early on. The word for Germany’s army, the Wehrmacht, translates to defense force. The title of this 1928 map of territory lost in the Versailles agreement translates to “Germany’s mutilation:”

Anti-Semitism Worsens

Anti-Semitism Worsens

The German Jewish population only slowly lost faith in the idea that Germans and Western Europeans were too sophisticated and progressive to go for the type of rampant anti-Semitism more associated with Eastern Europe. Aside from being de-emancipated by the Nuremberg Laws, they were forced to wear yellow Star of Davids. On Kristallnacht, the “night of the broken glass” in 1938, Hitler’s paramilitary troops pillaged Jewish businesses and synagogues throughout Germany and Austria, killing hundreds as they rounded up 30k Jews to be sent off to concentration camps. They blamed Jews for the damage since they’d been the targets, fined them, and required that all the insurance money go to the state. The pretext for the attacks was the assassination of a German official in Paris by a Jewish teenager from Poland. FDR ordered American Ambassador Hugh Wilson home after the Kristallnacht. Wilson supported Hitler and broke with his predecessor William Dodd’s (1933-37) policy by attending a Nuremberg Rally. Wilson complained that “Jewish-controlled” critics back home sang “hymns of hate while efforts are made over here to build a better future.” For more on American corporate funding and ideological support for Nazi eugenics, see the optional section at the bottom of the chapter on Nazi ideology (anti-Semitism, religion, science, history, philosophy).

The German Weapons Act of 1938 loosened up gun restrictions, deregulating rifles and shotguns altogether for Gentiles while banning Jewish ownership, manufacture or dealing of firearms. Modern American enthusiasts inclined to liken gun registration to Nazism have their history mostly backward. While it would still be an irrelevant and bad analogy, a better comparison would be to liken gun control advocates to the Weimar Republic, since they toughened gun laws from 1919-32 in an effort to tame the sort of paramilitary groups Hitler led. Those were the laws the Nazis repealed in time for Gentiles to use guns on Jews during the Kristallnacht. Previously Nazis tightened up registration laws for social democrats, another potential enemy they didn’t want armed. What’s not backward about modern gun enthusiasts’ interpretation is that the Nazis took advantage of gun registrations to confiscate Jewish guns, though it’s worth pointing out that in the vast majority of historical cases registration hasn’t led to confiscation. However, having guns wouldn’t have helped Jews much as they were vastly outnumbered.

Many Jews (~ 25%) migrated when they could up through 1938, when immigration quotas even went unfilled. Shanghai offered an unlikely refuge for 17k refugees from Germany and Austria. The International Settlement within the Chinese city that the British, French, Americans, Italians, and Portuguese carved out in the nineteenth century (Chapter 3) included small populations of Sephardic Jewish traders from Iraq and Ashkenazi Jews who fled Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 (Holocaust Museum). When Japan conquered Shanghai in 1937, they didn’t establish a naturalization policy, leaving a loophole whereby refugees could move there and the existing Jewish population helped them assimilate.

However, Western countries tightened their immigration restrictions once the going got rough in Germany. Some Jews had escaped to England earlier and later aided the Allies in translating bugged conversations of German POWs. In the U.S., Jewish refugee Albert Einstein helped convince FDR to develop the atomic bomb. (Other notable Jewish immigrants in the 1930s included future diplomat Henry Kissinger and founders of the influential Blue Note Record label.) But by 1938, Jews could still leave Germany with an exit tax and no one would take them, at least not in large numbers. Polls showed that most Americans disapproved of Nazi policies, but less than 20% of the “Greatest Generation” favored opening American shores to Jewish immigrant refugees. Eighty-five percent of Protestants and Catholics opposed offering Jews refuge, as did 25% of Jewish Americans. We should remember, at least, that few people knew about the concentration camps in the late 1930s.

Despite his own anti-Semitism (see optional article below), Franklin Roosevelt organized a conference at Evian, France to discuss the escalating Jewish refugee situation. Of the 32 countries participating in the Evian Conference, all expressed sympathy for the Jewish plight, just not quite enough to offer refuge. Only the Dominican Republic agreed to significantly loosen its immigration restrictions. Australian delegate Sir Thomas White typified the others’ attitude — and echoed Hitler’s justification for the Holocaust — stating that “Australia didn’t have a racial problem and we’re not desirous of importing one.”

It wasn’t easy for Gentiles to enter America for that matter since authorities feared Nazi sympathizers coming to spy or cause damage as Germans had during WWI. The family of Captain Georg Johannes (Baron) Von Trapp — subject of The Sound of Music (1964) — was detained at Ellis Island and nearly deported back to Europe, where they probably would’ve been arrested and liquidated by the Nazis. An Austrian naval commander decorated for service at the Boxer Rebellion and in WWI, Baron von Trapp (left) refused to fly the Swastika at their estate and then refused an invitation for his family to sing at Hitler’s birthday party. They fled Europe and headed for America with traveler’s visas (their 2nd trip there), but his wife Maria accidentally told the customs agent that they hoped to stay. Luckily, a family friend vouched for them and the Trapp Family Singers settled in Vermont and began touring the country.

Most Jewish immigrants were less fortunate. Defying First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s wishes, Franklin refused to loosen immigration laws once large numbers of refugees tried to escape in the late 1930s. The U.S. and Cuba turned away the MS St. Louis with nearly 1k Jewish refugees on board in 1939, though the passengers aboard the “voyage of the damned” eventually gained asylum in England, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Allowing the passengers entry into the U.S. would’ve violated the immigration quotas set in the 1920s. The U.S. allowed a total of ~ 211k Jewish immigrants from 1939-46. FDR purportedly complained about having to listen to Jewish sob stories about the plight of refugees (HNN). His Asst. Secretary of State, Breckenridge Long, was also anti-Semitic and, crucially, in charge of dispensing visas.

Nazis relished the harshness of Anglo-American immigration policy. One German diplomat gloated, “Since in many countries it was recently regarded as wholly incomprehensible why Germany did not want to preserve in its population an element like the Jews…it appears outstanding that countries seem in no way anxious to make use of those elements themselves now that the opportunity offers.” The tightening up of foreign borders in the late ’30s helped seal the fate of Jews trapped in Europe. Cartoonist Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss, captured the prevailing sentiment of most Americans regarding refugees circa 1941:

Fascism & the Axis Powers

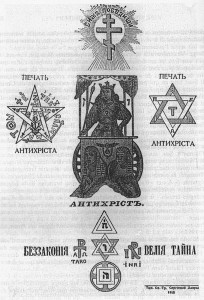

Liberalism (broadly defined) was declining in Europe by the 1930s as republics struggled to establish order amidst the post-WWI chaos. Spanish fascists under Francisco Franco won their Civil War over left-leaning Loyalist Republicans (and 3k American volunteers in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade) and an alliance of fascists and Catholics won a short skirmish over social democrats in Austria in 1934 (the Februarkämpfe), setting that German-speaking country up for an easy annexation by Nazis in the 1938 Anschluss. Spain’s neighbor Portugal came under the rule of fascist António de Oliveira. Hitler said that only three things were capable of world domination: Catholicism, Fascism, and Freemasonry.

Fascist Benito Mussolini took over Italy in 1922. In Africa, Italy controlled Libya and Somalia and, in 1935, they bombed Ethiopians armed with spears into submission. Their aerial blitz, along with similar civilian attacks by Spanish fascists, anticipated larger attacks in WWII (the Germans bombed Paris and London some toward the very end of WWI). Nazis didn’t establish a formal alliance with Franco’s Spanish fascists but allowed them to use their civilians to test out German aerial bombs.

Mussolini was one of Hitler’s inspirations around the time he wrote Mein Kampf. The Heil Hitler right-hand salute the Nazis made famous started with Mussolini, who argued that handshakes were too effeminate. Americans used a similar salute for the Pledge of Allegiance after its invention in 1892 but switched to the hand over the heart during WWII. Just as Hitler was proud of the fascists’ performance in the 1936 Olympics, Mussolini crowed about Italy’s back-to-back wins in the 1934 and ’38 soccer World Cup. He dreamed of reviving the old Roman Empire’s glory (originally, the Heil salute started with Caesar, as in “Hail Caesar”). While Mussolini shared Hitler’s love of violence and recruited paramilitary Blackshirts who could win street battles, he wasn’t publicly anti-Semitic. His own mistress was Jewish and Jews even gained equality under Italian fascism. Mussolini had been a communist when he was younger — even gaining the positive admiration of Lenin — but, like Hitler, he grew to despise communists and blamed them for Italy’s weakness during the Great War. Mussolini also temporarily stamped out the Mafia’s influence in Sicily and throughout Italy. Unfortunately, for the U.S., that led to emigration during the height of Prohibition and the sudden influx of new gangsters kick-started a re-jostling in New York called the Castellammarese War. When the dust settled, the modern American Mafia was born, led by Lucky Luciano and the “Commission” of Five Families.

Back in Europe Der Führer (Hitler) established an alliance with Il Duce (Mussolini) as Germany and Italy formed the Axis Powers, so named because the two countries formed an axis running north to south in central Europe. After Japan’s invasion of Manchuria and Italy’s conquering of Ethiopia, Hitler realized how impotent the League of Nations would be in the face of naked aggression. Germany’s Rhineland, Austrian, and Czechoslovakian (Sudetenland) invasions came on their heels.

Munich Pact & Nazi-Soviet Pact

After the Austrian invasion, the Allies met with Adolf Hitler in Munich. In the 1938 Munich Pact, Hitler agreed not to expand any further beyond what he’d already taken, plus the Sudetenland portion of Czechoslovakia, but the Allies got nothing in return other than temporary peace and that empty promise. Hitler invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia five months later and Poland and France within two years. As American Ambassador to the United Kingdom’s Court of St. James (Britain), Joseph Kennedy, Sr. represented the U.S. by proxy at Munich, while Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain represented Great Britain and Édouard Daladier France. Winston Churchill, who was out of power in Britain, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and America’s Soviet Ambassador Joseph Davies all wanted to unite against Hitler in a collective security pact, but that didn’t happen. Chamberlain shared Churchill’s earlier view that a strong Germany provided a bulwark against Soviet communism, but held onto the idea longer than Churchill. For his part, Hitler failed to form a hoped-for alliance with Britain. Franklin Roosevelt was skeptical off the record but cabled “good man” to Chamberlain after the Allies signed the Munich Pact with Hitler.

Remember Munich has become a catchphrase among Hawks in almost any circumstance since, meaning that problems are better nipped in the bud (thwarted) early on before they get out of control later (another less famous meaning is to remember the eleven Israeli athletes killed by terrorists in the 1972 Munich Olympics). The much-reviled Munich Pact is often either the reason for war or at least the reason provided to the public to justify war if there are other reasons. In The Godfather (1972), capo Peter Clemenza favors avoiding the Munich mistake by escalating a gang war without delay. Delay or inaction are inevitably equated with spinelessness or naiveté in this line of thinking — an old idea that just had a name after 1938. This Lesson of Munich, i.e., that appeasement only feeds the aggressor’s appetite, is worth considering for sure but has also narrowed American options ever since in areas like Vietnam and Iraq, leading to knee-jerk, escalate-first-and-ask-questions-later strategies haunted by what critics call the “ghost of Munich.” It also contributed to western countries forming NATO during the Cold War to oppose the Soviet Union (more in Chapter 13). But countries that never dither (as hawks call it) are easy to bait, for one thing, allowing enemies to dictate when, where, and how they employ resources. The smartest policy is always to keep a range of options on the table, including diplomacy, delayed action, or swift action. In America’s Civil War, for instance, the Confederacy should’ve invaded Washington, D.C. early in 1861, before it was defended. Churchill himself reminded readers that all historical contexts are different. Oversimplified historical analogies and trite phrases like Remember Munich can be worse than historical amnesia. And if the image on the right of Chamberlain shaking Hitler’s hand is a bad look, especially standing on a lower step, that too is irrelevant to the question of whether it’s wise to rush into war.

In this case, even our idea that Munich was a mistake in the first place isn’t as straightforward as it might seem. Readers familiar with WWII history might gasp or faint initially upon reading this but permit me to explain. None of the Allies had large armies in 1938 and they weren’t prepared for war. If they’d challenged Hitler then, they might have lost the war or, later, won a more difficult victory. The U.S. military, for instance, was about the same size as Sweden’s (330k), 17th biggest in the world, and had fewer than 500 machine guns. The British could’ve mustered two ill-equipped divisions for a continental invasion. Because of changes in their constitutional status, UK Commonwealth countries Canada, Australia, and New Zealand wouldn’t have necessarily fallen in behind Britain (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland) if they declared war, the way they had in World War I. The British also lacked faith in the French military because of so much turnover among their political leaders; Third Republic governments averaged nine-month tenures in the 1930s. Also, despite opening communications with Stalin, the British still envisioned the Soviet Union as enemies not potential allies against Hitler. Chamberlain wasn’t motivated so much by naiveté toward Germany as distrust of the Soviets. The British public wasn’t riled up about Germany taking over German-speaking areas like the Rhineland or Austria, let alone part of newly-created Czechoslovakia (1919). Was it their job to go save people who, for all they knew, didn’t want to be saved? Austria hadn’t put up a fight anyway and the Rhineland voted to return to Germany. The Munich Pact also delayed Germany’s attack on the rest of Czechoslovakia, which Hitler later regretted. We know from archives opened in the 1950s that British military brass and MI6 told Chamberlain point-blank there was no hope of defending Czechoslovakia, but that their prospects for winning a long, protracted war were decent if they had time to build planes and ships. What sort of political ruler would have rushed in troops immediately based on that advice? Instead, British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) opened their code-breaking headquarters at Bletchley Park in 1938 to prepare for a war that both they and Chamberlain anticipated eventually fighting.

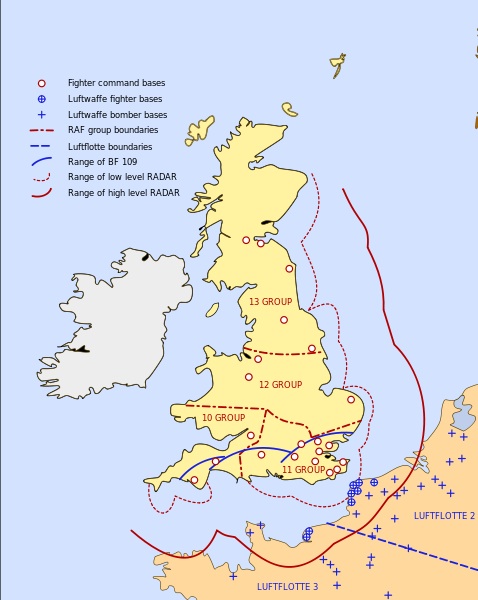

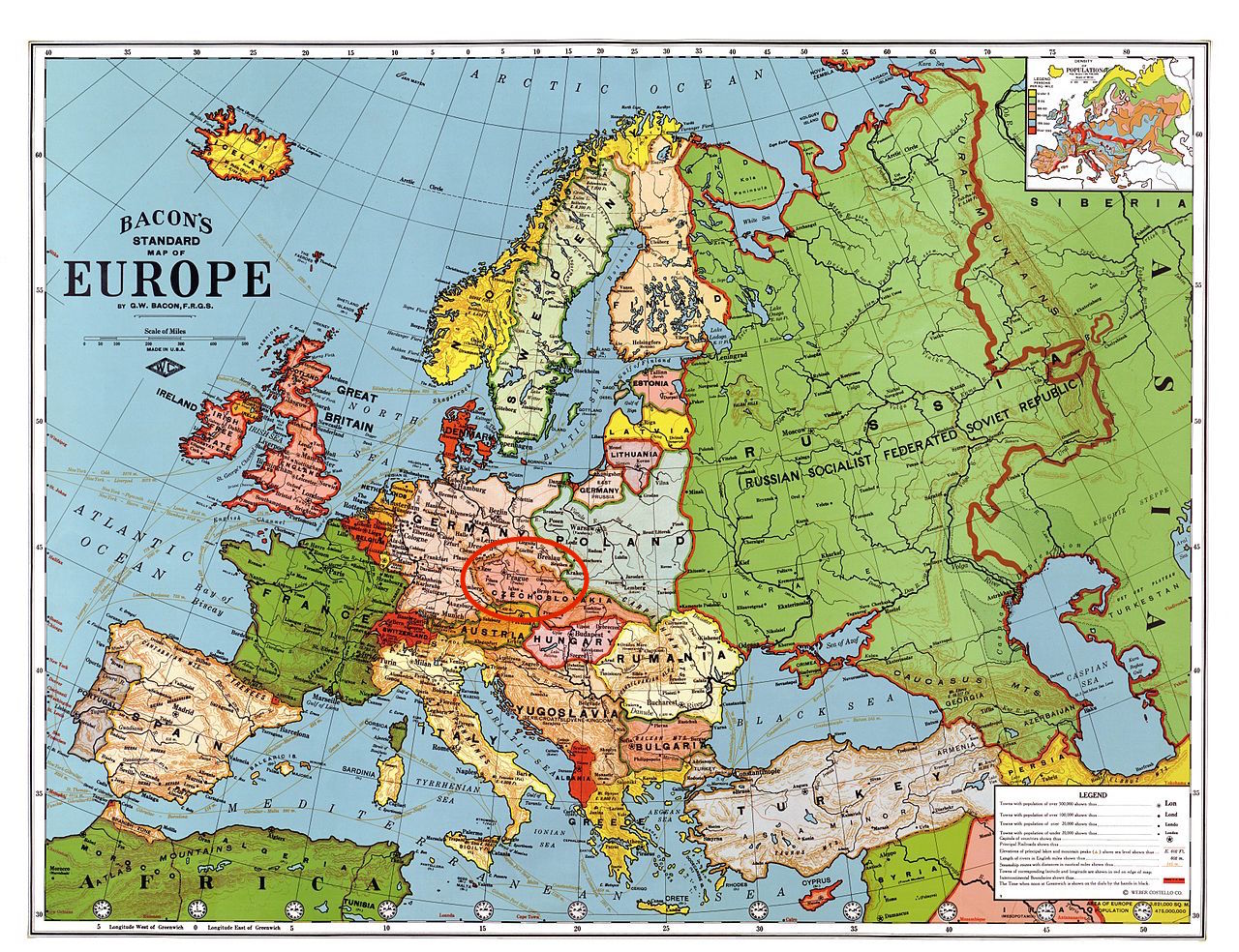

The Allies’ real mistake was not making better use of the time they bought in Munich so that they’d be better prepared later. Ambassador Kennedy’s son John argued just that in his senior thesis at Harvard, later published as Why England Slept, an allusion to Churchill’s While England Slept. When Germany attacked in 1940, France was no stronger than they were two years earlier and Britain was only slowly strengthening, its main gains coming in the Royal Air Force (RAF). In Britain’s case, it was wiser for them to prepare more at home than to take a futile stand in a small part of Czechoslovakia where a third of the people spoke German, tucked on the other side of Germany (red circle below). That’s slowly but surely what they did and the RAF’s fighter technology was further along in 1940 than ’38. With the benefit of hindsight, Britain could’ve done even more to prepare under prime ministers Chamberlain and his predecessor Stanley Baldwin.

Europe in 1923 w. Sudetenland Circled, George Washington Bacon, Library of Congress’ Map & Geography Division

Ethnic distribution in Austria-Hungary in 1911: regions with a German majority are depicted in pink, those with Czech majorities in blue

Critics later derided Neville Chamberlain for his broken promise of “peace in our time” and Winston Churchill capitalized by returning to power as Britain’s Prime Minister. But Churchill’s argument that Britain missed its chance to stymie Hitler at Munich was unrealistic, at least minus the aforementioned three-way pact with the Americans and Soviets that he favored along with Davies and Stalin. Not only were British and French citizens desperate to avoid another war — and so far, they hadn’t been directly attacked — but Churchill himself wasn’t willing to open a western front once the war began! Should Chamberlain have been expected to open an eastern front even earlier or a western front to draw German forces from Czechoslovakia? Geography matters here.

Not everyone agrees that the Western Allies were less prepared in relation to Germany in 1938 than they were in 1939 or ’40. Hitler’s own generals argued at the Nuremberg Trials after the war that the Allies missed a chance to defeat Germany as late as 1938, pointing out that bad intelligence caused the Allies to overestimate the strength of German forces at the time. They’d supposedly tricked American spies and visitors into overestimating the size of their Luftwaffe, or air force. Some historians think likewise, arguing that Germany would’ve been easier to defeat in 1938 than after 1939. Even diplomat George Kennan, who later argued against over-applying the lessons of Munich, wrote here that Germany’s generals lacked confidence in their capacity to defeat the Czechs and were even considering a coup if Britain and France hadn’t capitulated at Munich. So, there was widespread disagreement as to Germany’s power circa 1938, and both sides’ military felt unprepared for war. British military intelligence tended to overestimate German strength prior to Munich and underestimate it after according to this line of thinking. Also, Germany occupied far more territory by 1940, including northern Europe, Poland, southeastern Europe, and North Africa, presumably making them harder to reign in, though their resources were spread thinner, partly offsetting this factor.

The classic appeasement-was-a-mistake interpretation of Munich isn’t necessarily wrong, but it needs to be predicated on this angle: that the Allies were stronger in relation to Germany proportionally in 1938 than they were by 1939-40. Without that critical premise, the argument falls apart and the Free World should be grateful that the maligned Chamberlain was in power rather than the revered Churchill. Churchill himself allowed for the advantages of buying time in his Second World War (1948-1953), writing that, as of 1938:

“No one could deny that we were hideously unprepared for war. Who had been more forward in proving this than I and my friends? Great Britain had allowed herself to be far surpassed by the strength of the German Air Force. All of our vulnerable points were unprotected…If Hitler was honest and a lasting peace had in fact been achieved, Chamberlain was right. If, unhappily, he had been deceived, at least we should gain a breathing space to repair the worst of our neglects.”

Why, then, did Churchill think that Munich was a mistake, both as it unfolded and in retrospect? Because, while the extra time aided Britain, allowing for arms buildup and the development of the Hurricane and Spitfire planes that defeated the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain two years later, the French army was stronger in relation to Germany in 1938 than they were two years later and Germany was able to recruit even more soldiers from the areas it conquered after 1938. But, also, Churchill was a political opportunist and used German aggression after Munich to gain power as prime minister over Chamberlain.

Churchill and Kennan’s calculations aside, the Munich Pact’s more simplified teleological critique is a classic case of “armchair quarterbacking” as American sports fans say, or criticizing only with the benefit of hindsight or being out of power. And even if Churchill and Kennan were right about Munich, it doesn’t follow that it’s smart to put “boots on the ground” as quickly as possible in every future scenario, as both men attested to. As for Ambassador Kennedy, who was also anti-Semitic, he clung too long to his German appeasement policy, ruining his presidential hopes with pessimistic comments about democracy’s bleak prospects. Meanwhile, his son John got around a medical disqualification and went on to command a PT (patrol torpedo) boat in the Pacific, bolstering his future political opportunities.

Absent any collective security with the Western Allies, Stalin worried that his army wasn’t strong enough to take on Hitler by himself. Germany signed a truce with the USSR whereby the countries agreed to not fight on an eastern front in any future war and to divvy up Poland, the country that lay between them. With the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, Hitler was just stalling, giving his military time to catch its breath and grow stronger after taking Czechoslovakia and Austria. After a failed attempt to conquer Britain, he broke the truce and invaded the Soviet Union (USSR) in June 1941 with Operation Barbarossa, even after the Soviets helped supply Germany’s French invasion and Nazi officers attended a military parade in Moscow in May 1941. Hitler hoped to divide the USSR and acquire the oil fields of the Caucasus, in the country’s southern part. Seizing the oil would not only fuel the Third Reich but also paralyze the Soviet Red Army. The Nazi-Soviet Pact also brought a temporary end to the conflict between Japan and the USSR in Mongolia, since Japan was allied with Germany and Germany was allied with the USSR (for now).

The Western Allies never forgot Stalin’s willingness in 1939 to deflect German military aggression in their direction. Of course, Stalin could argue that the Western Allies had tried to do the same to him at Munich in 1938. Either way, when Hitler invaded the USSR in 1941, the Allies were slow to come to Stalin’s aid. By then they’d felt Germany’s wrath across Europe, from Poland to France, the Low Countries (Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg), Scandinavia, Greece, and Britain.

World War II in Europe

Germany’s Blitzkrieg (lightning warfare) invasion of Poland in September 1939 started World War II in Europe. In his Obersalzberg Speech on the battle’s eve, Hitler laid out his ruthless ambition to expand German territory:

Our strength consists in our speed and in our brutality. Genghis Khan led millions of women and children to slaughter—with premeditation and a happy heart. History sees in him solely the founder of a state. It’s a matter of indifference to me what a weak western European civilization will say about me. I have issued the command—and I’ll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad—that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formation in readiness—for the present only in the East—with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks to-day of the annihilation of the Armenians?

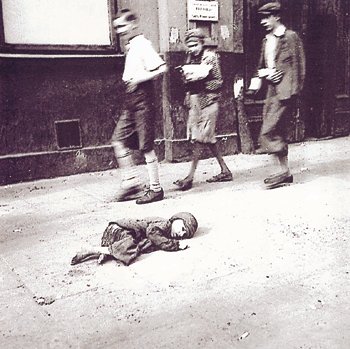

“A starving child lying in a ghetto street,” Warsaw Poland, by Heinz Joest, a Wehrmacht Sergeant, Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial Museum, Israel

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini made similar comments in the Political & Social Doctrine of Fascism (1932). For Mussolini, peace was “born of the renunciation of the struggle and an act of cowardice in the face of sacrifice.” Two countries Germany invaded, Poland and Czechoslovakia, weren’t countries until the new map drawn up at Versailles in 1919, probably making them less resilient to attack. The Jewish child on the left is in the Warsaw Ghetto, where Germans rounded up almost the entire population and sent them to camps. After Poland’s invasion, France and Britain — still under the leadership of Neville Chamberlain — declared war on Germany, and Hitler turned his attention west after resting and rebuilding his forces during the Sitzkrieg. British called the Sitzkrieg the “Bore War” while American journalists dubbed it the “Phony War.” Germany conquered Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands in April and May of 1940. British-led coalition forces under First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill tried to stem the Norwegian invasion but failed, lowering Brits’ confidence in Chamberlain and leading to the ascension, ironically, of Churchill as the new Prime Minister. We’ve seen Churchill fail spectacularly at Gallipoli (Chapter 6) and as Chancellor of the Exchequer (Chapter 8) but he rose to the occasion during World War II, as we’ll see below.

The Axis Powers of Germany and Italy signed the Tripartite Pact with their imperial counterpart Japan in September 1940. Germany and Japan reinforced each other because Japan coveted the European-held colonies of Asia. Germany kept Britain, France, and the Netherlands at bay in Europe, making it impossible for them to defend their territories in Shanghai, British Hong Kong and Singapore, French Indochina (Vietnam), and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). The same dynamic explains why Hitler declared war on the United States days after Pearl Harbor, as we’ll see below. Prior to that, it wasn’t worth ramping up the quasi-war in the Atlantic enough to draw America into the European war, as happened in 1918. After Pearl Harbor, Hitler figured that the U.S. couldn’t fight two wars at once against Japan and Germany, so why not go all-out in the Atlantic to blockade Britain?

When Germany revved its war engine again in May 1940, they had an easier time invading France than they had in 1914. France built a series of bunkers along their shared border called the Maginot Line but didn’t anticipate that German tanks would daringly go through forested areas. Since this took longer, drivers fueled themselves with a methamphetamine stimulant called Pervitin — 35 million total tablets to be precise according to researcher Norman Ohler. After feigning an attack on more well-guarded portions of Belgium, Germany’s main divisions poured into the less defended Ardennes Forest, encircling French and British forces on the coast as part of their Manstein Plan. The Netherlands fell around the same time.

Desperate Allied forces from Britain, Belgium, Australia, and Canada fought with the French on the continent but had to be rescued from Dunkirk on the northeast French coast. The city was largely on fire, with its fuel tanks exploded, but German forces halted outside Dunkirk hoping their Luftwaffe Stuka dive-bombers could finish the job. The Stuka’s sirens wailed as they dove for psychological effect (Jericho-Trompete or “Jericho Trumpets” as the Germans called them). United Kingdom Prime Minister Winston Churchill refused to consider negotiating with Germany or Italy despite the advice of Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax. Anticipating the upcoming Battle of Britain and seemingly willing to cut some losses, Churchill also refused to expose too many Royal Navy ships to U-boat attacks and mines to rescue the trapped forces. Though harsh and demoralizing to those trapped with their backs to the North Sea, preserving most planes, ships, and troops was a key to future success because they “lived to fight another day.” Still, Churchill warned that wars weren’t won with retreats, and the British left most of their artillery, trucks, and tanks in German hands, along with ~ 50k troops (now POWs). The famous retreat is the subject of Dunkirk (2017) and Darkest Hour (2017), the former of which inadvertently whitewashes the affair by excluding the many Africans and South Asians in the British and French armies and British merchant fleet.

French forces fought hard for a while, but France’s conservative government failed to anticipate a Nazi attack because they thought they had a good relationship with Hitler, and the army was unable to pull their act together in time despite having more tanks and artillery than Germany. Within a matter of months, outnumbered, outgunned Nazis controlled two-thirds of France, setting up a collaborative government in the town of Vichy. They took over the entire country in December, 1942. Germany vengefully and symbolically forced France to sign off control of their country in the same train car in which they’d been forced to capitulate in 1918. Free French forces left the country to fight another day, while uncooperative citizens formed an underground resistance to courageously pester Nazis as best they could through railroad sabotage, car bombings, assassinations, etc.

B ritish Special Operations Executives infiltrated France with spies to help the French Resistance. Espionage became an important part of the war effort and the SOE often used unlikely agents as spies because they were less visible and likely to attract attention. One important radio operator working behind German lines in France, for instance, was Noor Inayat Khan, daughter of a Parisian Sufi instructor. She won the George Cross, the highest civilian wartime honor in the United Kingdom. The average life expectancy of radio operators behind enemy lines was six weeks and Khan died at Dachau concentration camp after relaying important messages for two years, refusing to relinquish details about her network even when tortured by interrogators. American-born jazz singer Josephine Baker (right) was another unlikely spy working in Vichy France. She relayed information in invisible ink on her sheet music and her profession offered a convenient cover for moving around the country. She also shared some secrets with the Free French that the Americans and British intended to keep to themselves because they didn’t trust their leader, Charles de Gaulle. In 2021, France inducted Baker into its Pantheon monument to historical heroes (AP). She personally raised the equivalent of over $11 million today to support the French Resistance against Nazi occupation. A third SOE spy that later worked directly for the OSS (precursor to the CIA) was American Virginia Hall. She relayed funding from the Allies to the French Resistance, overcoming the challenges of her prosthetic leg. Germans nicknamed her the “limping lady” and, for a while, she topped their most-wanted list. Their stories are just three of thousands that contributed to the Allies’ ultimate victory.

ritish Special Operations Executives infiltrated France with spies to help the French Resistance. Espionage became an important part of the war effort and the SOE often used unlikely agents as spies because they were less visible and likely to attract attention. One important radio operator working behind German lines in France, for instance, was Noor Inayat Khan, daughter of a Parisian Sufi instructor. She won the George Cross, the highest civilian wartime honor in the United Kingdom. The average life expectancy of radio operators behind enemy lines was six weeks and Khan died at Dachau concentration camp after relaying important messages for two years, refusing to relinquish details about her network even when tortured by interrogators. American-born jazz singer Josephine Baker (right) was another unlikely spy working in Vichy France. She relayed information in invisible ink on her sheet music and her profession offered a convenient cover for moving around the country. She also shared some secrets with the Free French that the Americans and British intended to keep to themselves because they didn’t trust their leader, Charles de Gaulle. In 2021, France inducted Baker into its Pantheon monument to historical heroes (AP). She personally raised the equivalent of over $11 million today to support the French Resistance against Nazi occupation. A third SOE spy that later worked directly for the OSS (precursor to the CIA) was American Virginia Hall. She relayed funding from the Allies to the French Resistance, overcoming the challenges of her prosthetic leg. Germans nicknamed her the “limping lady” and, for a while, she topped their most-wanted list. Their stories are just three of thousands that contributed to the Allies’ ultimate victory.

Winston Churchill couldn’t convince the French to destroy their navy as they retreated and he didn’t want it to end up in German hands. Thus in July 1940, Britain destroyed the French fleet and harbor at Mers-el-Kébir in Operation Catapult — an operation about half as large and deadly as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. The attack helped win over FDR, who was impressed with Churchill’s ruthlessness.

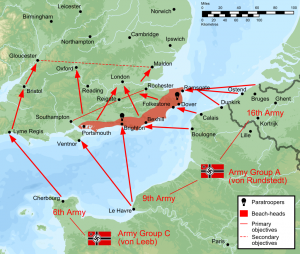

With Germany occupying most of France, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, and southeastern Europe after the Battle of Greece in April 1941, they now controlled nearly the entire continent. They reached an accord with Franco’s fascist regime in Spain, but not a formal alliance like they had with Italy. Swiss banks agreed to help finance the Reich in exchange for maintaining Switzerland’s traditional neutrality. Britain stood virtually alone as they fended off Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe in the summer and fall of 1940. But, as relayed in the optional section below, the British fended off the German Blitzkrieg in the Battle of Britain, serving up Hitler his first real defeat. Operation Sea Lion (right), Germany’s proposed UK land invasion, never happened, stopping Germany’s momentum in the west, saving England from invasion, and arguably helping to defend America.

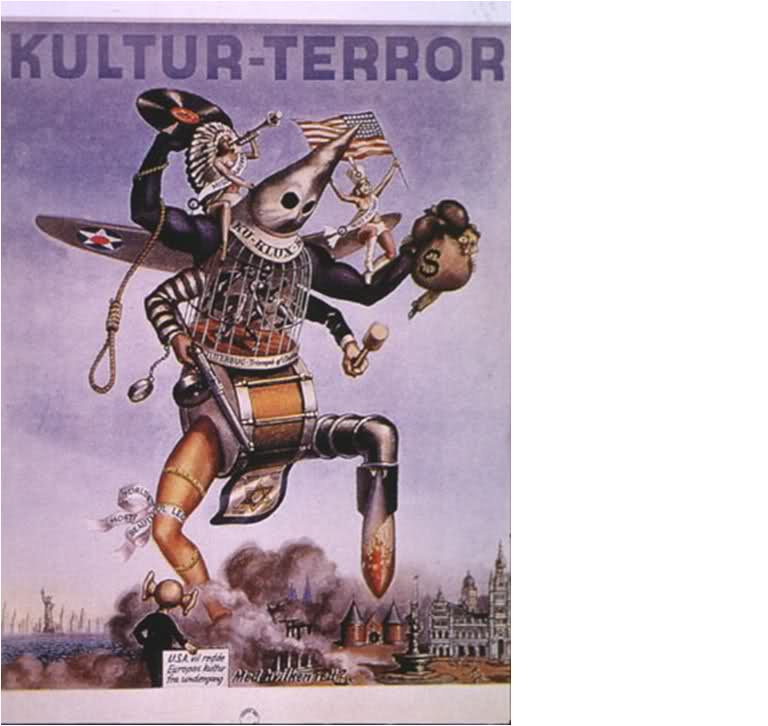

Instead, “stiff-upper-lipped” pilots, radar operators, munitions makers, and politicians — inventors of the original “Keep Calm & Carry On” posters and led by Winston Churchill flashing his “V for Victory” sign (right) — held off the Luftwaffe. Hitler finally gave up and decided to attack England with rockets launched from France as he focused his efforts on invading the USSR. Der Führer later pointed to the Battle of Britain as the turning point in the war. Frustrated at their inability to defeat Britain through the air, Germany turned east and invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 in Operation Barbarossa, dishonoring the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939. Hitler had planned this all along, but only after defeating Britain first. Germany’s Soviet invasion was welcome news all considered for the Western Allies but, still, it didn’t clear up Atlantic shipping lanes. Britain was still losing the Battle of the Atlantic by the summer of 1941, as “Wolfpacks” of German U-boats wreaked havoc on shipping from North America to Britain.

Interwar America

Winston Churchill desperately sought an American alliance. He said, “Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war…If we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age.” But in Depression-era America, there was only lukewarm concern for the Nazis’ onslaught.

Germany didn’t inspire much sympathy either. Despite its large German-American population, few Americans sided with them. The U.S. Nazi parties, the German American Bund and Free Society of Teutonia, were small and never posed a serious threat to U.S. security, despite being accepted enough to march in public parades (above); or, at least at seems like that in retrospect. The Bund ran 25 summer camps where young Nazis could hunt and fish and, similar to the German Lebensborn, blonde teenagers were encouraged to mate with each other. Their rallies changed FDR’s name to Frank D. Rosenfeld and called the New Deal the “Jew Deal.” The FBI, aided by undercover agents, tracked American Nazis in the late 1930s and rolled them up once war broke out, retaining some spies as double agents. New York’s District Attorney Thomas Dewey, later the GOP’s 1948 presidential candidate, had already prosecuted Bund leader Fritz Kuhn on embezzlement charges 1939.

But if Nazism never caught on, neither did most Americans favor intervention in another European war, especially because America’s stake in WWI was so muddled. Also, some American companies did business with the German Reich (e.g., GE, GM, Ford, DuPont, Kodak, Coca-Cola, Chase Bank, ITT, RCA, Gillette, and Standard Oil) and an IBM subsidiary made Hollerith punch cards to help the Nazis catalog and track the movements of Jews in Germany (IBM & the Holocaust). Standard Oil of New Jersey (later part of Exxon) sold to Germany as late as 1942. Like Ford, IBM’s Tom Watson was a Nazi favorite. General Motors’ Alfred Sloan sought contracts to motorize the German war machine via Opel, commenting that he “admired the strength, irrepressible determination and sheer magnitude of Hitler’s vision.” Sloan envied how much direct power corporations had in fascist governments.