When philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson said that America “begins west of the Alleghenies,” he didn’t mean the East wasn’t part of the U.S.; he meant that the frontier was a more quintessential part of American identity. The Wild West has always grabbed more than its share of America’s imagination, and Europe’s, despite having a much smaller population until this past century. Hollywood didn’t film thousands of “easterns” or recycle formulaic backlot movies about coal miners, steelworkers, or accounting clerks. Colleges don’t teach upper-division courses in Eastern History. Eastern Europeans drive pick-ups to American-themed bars to hear country music, not Corvettes to hear Sinatra or Elvis, even if Ted Lasso viewers will note that Amsterdam’s version includes Elvis, Marylin Monroe, a replica Trans Am, and Michael Jordan highlights.

It took over two hundred years for Euro-Americans to work their way from the eastern seaboard to the “Mighty Mississippi” and they were mostly ignorant about the area beyond the river. Among the Founders, Thomas Jefferson was most interested in the trans-Mississippi West but even his knowledge of the area was fuzzy. In 1804-06, the Lewis & Clark Expedition Jefferson sent west mapped much of the northern part of the region and one of its members, Zebulon Pike, branched off from the return trip to explore the southern Rocky Mountains.

Pike didn’t do much to whet fellow Americans’ appetite for the flat plains just east of the mountains by mentioning he’d seen “not a stick of timber.” In 1823, Army surveyor Stephen Long named those future Great Plains the Great American Desert. Long’s term was a bit of an exaggeration, but it spoke to the truth that the West was mostly arid. The map on the left shows average annual rainfall in the Lower 48. In 1869, Grand Canyon explorer John Wesley Powell accurately predicted that “many seasons in a long series will be fruitless” on either side of the Colorado River. More seasons would’ve been fruitless without the work of the Bureau of Reclamation (1901- ) that dammed and diverted water on either side of the river. Powell later directed the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) that planned a systematic mapping of resources to avoid a “heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights.” However, the USGS lost funding when one of its expeditions discovered dinosaur fossils and Congress opposed wasting taxes on “atheistic rubbish.” To this day, Westerners fight over water rights.

As this NASA nighttime “black marble” satellite image shows, even today the interior West is less populated than the West Coast and East (the bright lights in North Dakota are flares from the Bakken Formation). The U.S. might run low on water, but it’s not about to run out of space.

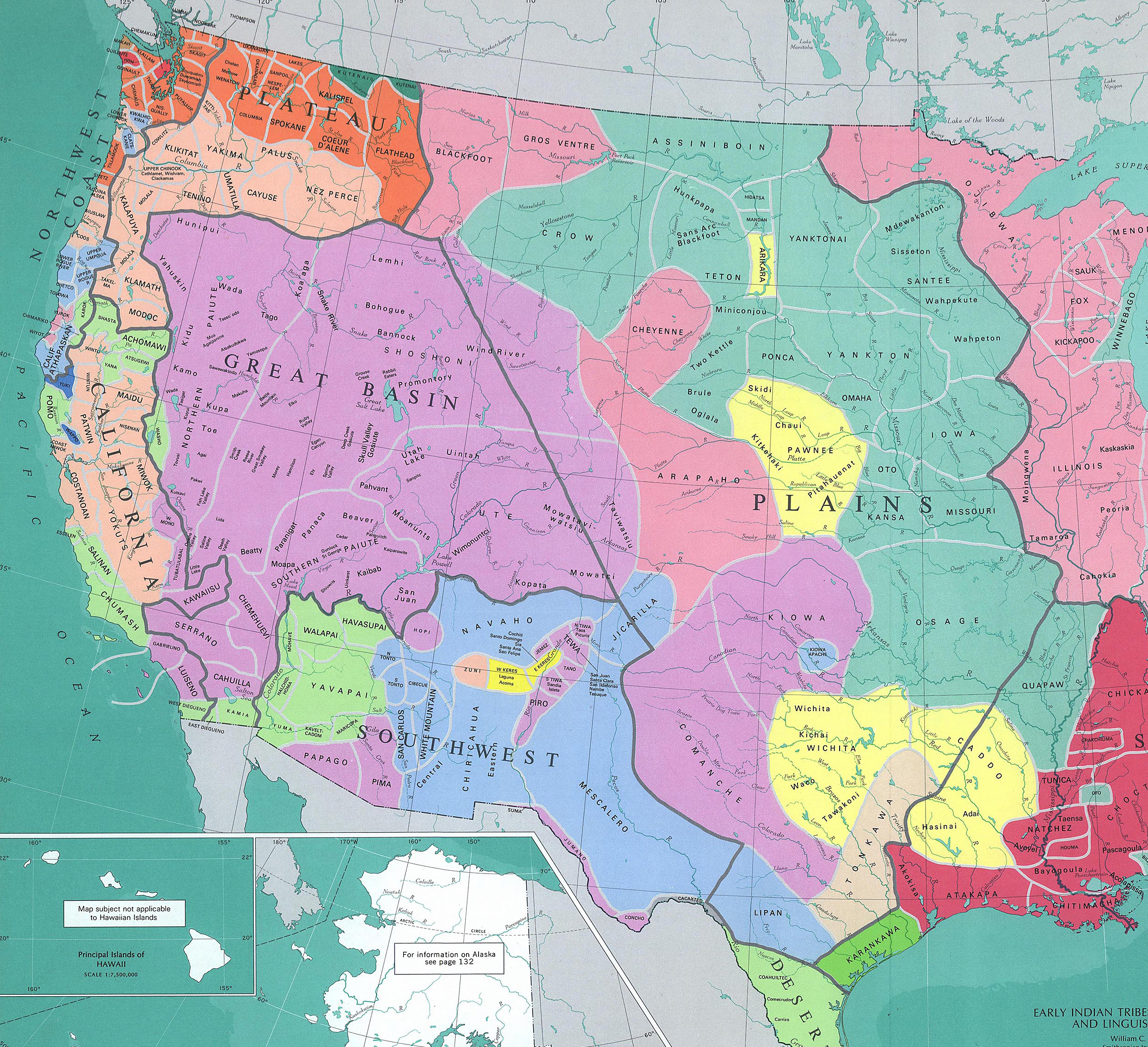

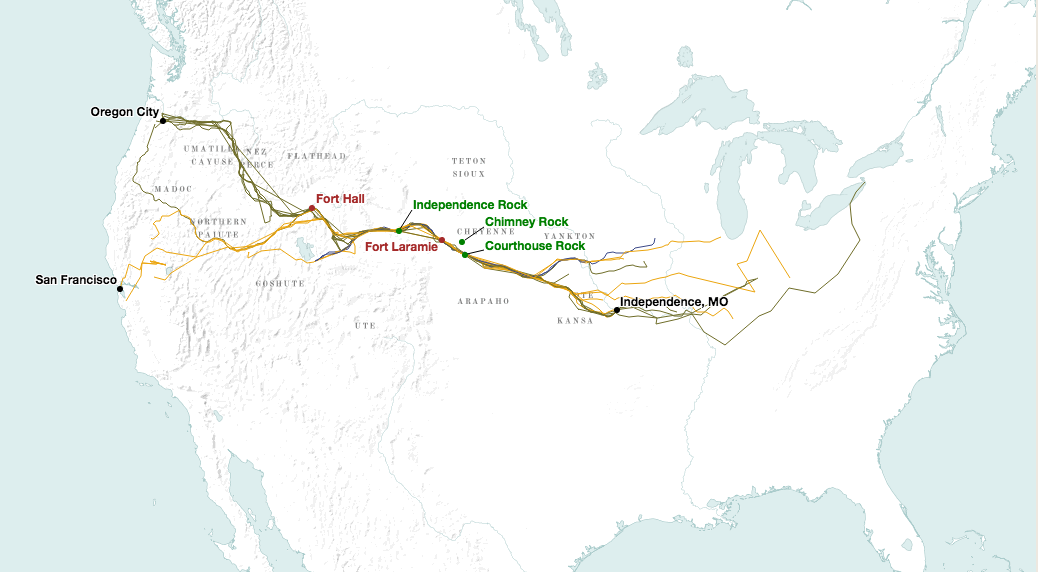

The West gave way to white settlement faster than the East had because the railroad and telegraph tamed its vast geography in the 1860s. In the early to mid-19th century, though, the West was mostly politically uncontrolled territory, claimed by many — Indigenous Americans, Mexicans, Mormons, British, Euro-Americans — but not really governed by anybody. While we’ll briefly examine the interaction of West Coast tribes with American settlers twice here and unpack the Great Plains Indian Wars in Chapter 23, this chapter doesn’t attempt to do justice to the long, rich history of millions of people who lived in western North America over the centuries. Due to your author’s limitations and the scope of our course definition, it’s written from the U.S. vantage point, as implied even in the title “Westward Expansion.” But one could write all this history from a Native American perspective (e.g. Daniel Richter or Ned Blackhawk), with the lens of the camera pointed in the other direction. For Mexicans, this was the North; for Russians the far, remote Southeast; for Britain another potential colony that could connect to eastern Canada; for Mormons their own country to practice their faith; for Indigenous Americans, this was neither north, west, nor east, but rather their ancestral homeland. Enlarge this map to orient yourself, but as we’ll see in Chapter 23, some tribes migrated across entire regions, including from the Great Lakes to the Plains and Mountain West; while others, like Navajos, migrated from the northern Rockies and Alaska into the Southwest sometime around 1400 CE.

From the U.S. perspective, this was the region German painter Emanuel Leutze captured the tail end of in Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, whose giant canvas now graces the House Chamber staircase in the nation’s Capitol. The painting is commonly known as Westward Ho!

Westward, the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (aka Westward Ho!), U.S. Capital, Emmanuel Leutze, 1860

Old West

By the 1810s and ’20s, mountain men trapped in the Rockies, where cold weather and high altitudes made animal furs thicker. They lived solitary lives, using sign language to communicate with Native Americans and gathering once or twice a year to rendezvous and sell their pelts. Some married indigenous women and were content to stay away from white civilization. Like the cowboys of the next generation, eastern corporations employed most of these seemingly independent trappers. They fed the European fur market until killing off most of the beaver. Some of the early traders, especially Jedediah Smith in the late 1820s and later Kit Carson and John C. Frémont, mapped routes along familiar Indian trails that later settlers used for overland trips. Today, highways, especially pre-interstate, follow some of those same routes.

As far as American or European settlers of the sort that farmed and built towns, few ventured into the Trans-Mississippi West as of the 1820s. Railroads still lacked a common gauge, and Northerners and Southerners couldn’t agree on where to build a transcontinental route. Even if they had, significant engineering challenges would have made it difficult to build. Dynamite wasn’t invented yet and the country lacked the Chinese and Irish immigrants that built the railroads in the 1860s. The U.S. government didn’t have much presence in the Trans-Mississippi West either and neither did Mexico’s. What made the West as wide open politically as it was geographically was that neither Washington nor Mexico City was near enough to effectively extend its reach. London and Moscow weren’t even close.

With the advent of better farming implements and victory in the 1832 Black Hawk War, Euro-Americans settled the prairie states of the upper Midwest in the 1830s and ’40s. But there was little motivation to venture beyond the Missouri River. Take a moment to scroll over the 1840s on this Timeline.

The Santa Fe Trail connected Missouri to the fur trade starting in 1821, but there wasn’t much beyond that in terms of roads, canals, or towns. And there was the aforementioned lack of timber and water in most non-mountainous pockets of the West. Since the Pacific and West Coast were more accessible than the mountainous and desert terrain in between, the American frontier didn’t progress uniformly from east to west, as is commonly thought. American missionaries and sugar planters settled Hawaii in the 1820s, but Whites didn’t settle the Great Plains until after the Civil War. San Francisco, Portland, and Salt Lake City are older than Denver, Kansas City, and Omaha.

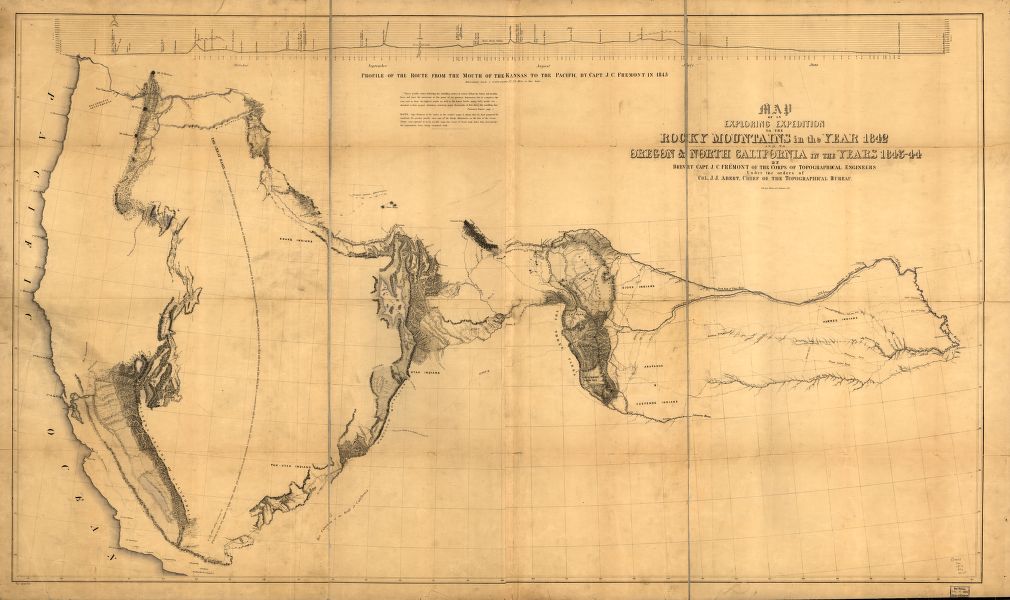

John Fremont, Map of an exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon & North California In the years 1843-44, Library of Congress

Manifest Destiny

By the end of the Jacksonian era, with Texas opening up and many farmers losing their land in the Panic of 1837, there were ample motivations for Americans to head west. These motivations mostly matched those that compelled Europeans to explore and settle America in the colonial era: opportunity, precious metals, religious freedom, missionary work, and land. In addition, growing competition between Northerners and Southerners to control the country accelerated western expansion as they raced each other into the region. The notion of Manifest Destiny, a phrase coined by New York journalist John L. O’Sullivan, gave a convenient ideological cloak to expansion: that God ordained that American Protestants spread west and overrun Indians and Catholic Mexicans. If that sounds familiar, it was a carryover from the notions that inspired the English to colonize America centuries earlier, and a variation on the Catholics’ own Discovery Doctrine from Chapter 3 that led to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. Sullivan was trying to convince fellow northerners that the annexation of Texas was in all Americans’ interests, not just southern slaveholders.

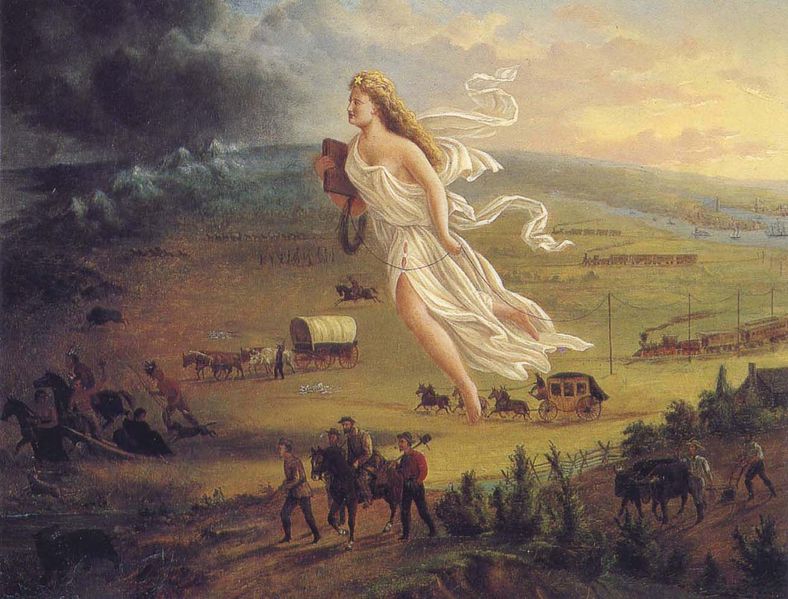

John Gast’s American Progress painting captured the idea best. Civilization, as represented by Columbia in virginal white, is carrying progress west in the form of a Bible, railroad, and telegraph wire. From the east (America) comes light, whereas Native Americans on the left are in the dark, bending in the direction of the oncoming American civilization. Various characters and miscreants could work as fur trappers, scouts, and miners, but when women and infrastructure arrived on the scene, churches, schools, and law-and-order soon followed. It’s easy to forget, though, that most of the settlers who went west were leaving the United States, even if some correctly assumed the area would eventually be annexed. Of course, an esoteric concept like Manifest Destiny wasn’t rolling off the lips of your run-of-the-mill trailblazer in the 1840’s and ’50s; most had likely never heard of it. Nor was there ever a consensus about the idea in the 19th century among leaders, and most Whigs/Republicans opposed expansionists’ policies when they got wrapped up in the Democrats’ push to expand slavery, as we’ll see in the next chapter.

Overland Trails & Oregon Country

Overland Trails & Oregon Country

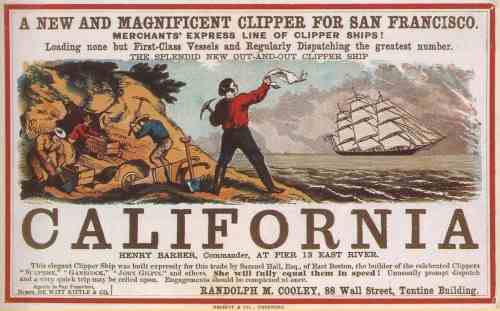

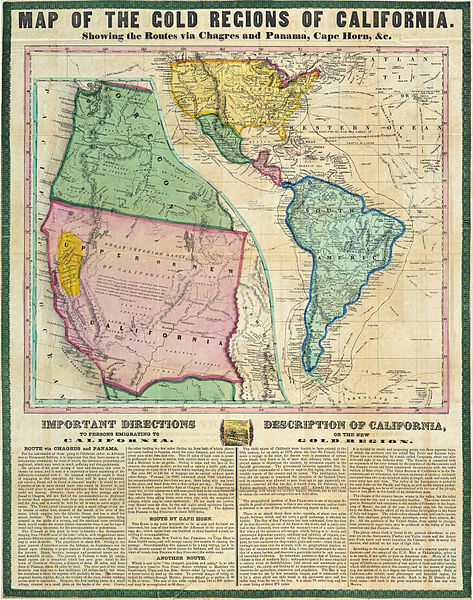

Going east to west wasn’t easy before transcontinental railroads. Water routes around Cape Horn in South America were lengthy and dangerous, and crossing the Panamanian Isthmus presented challenges of its own before the canal opened in 1914. In the 1840s, for around $600 (~$6k in today’s money), a family could outfit a Conestoga Wagon for the Oregon Trail. By the late 1850s, you could take an easier, $4k one-month stagecoach trip from St. Louis to California on the Butterfield Overland Mail Trail that followed a southerly route through northwest Arkansas, Texas, and the desert Southwest.

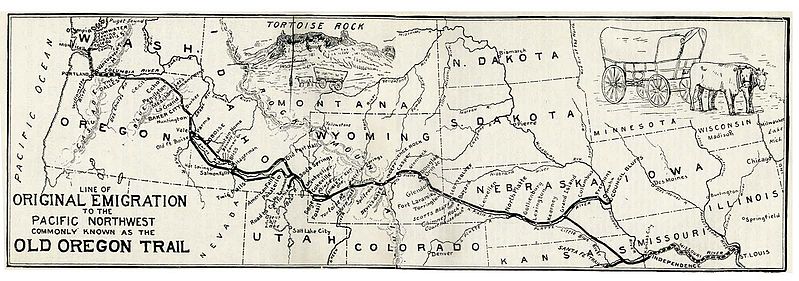

“Line of Original Emigration to the Pacific Northwest Commonly Known as the Old Oregon Trail” from The Ox Team or the Old Oregon Trail 1852-1906, Ezra Meeker, 1907, University of Texas Libraries

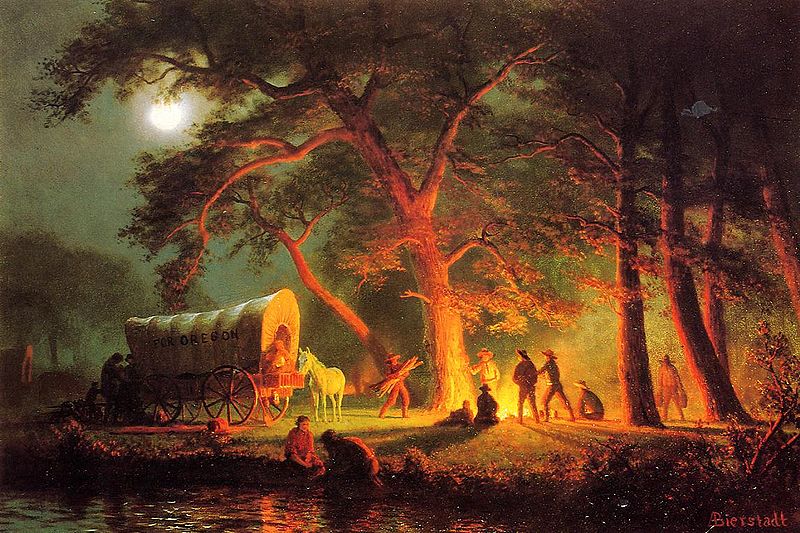

The Overland Trail was an alternative, overlapping route to the Oregon Trail commonly used by the 1860s. Those that could walk on the Oregon Trail did so to avoid weighing down the wagons that required constant maintenance to fix wheels, axles, and tarps. Wooden wheels expanded or contracted in extreme weather, causing more headaches. Indian attacks were few in comparison to what later settlers experienced since the wagon trains were only passing through. When attacks did occur, pioneers “circled their wagons” for protection.

Trips lasted around five to six months, with wagon trains leaving late enough in the year for the grasses on the Plains to feed their draft animals, and early enough, hopefully, to avoid winter storms in the second range of mountains, the Cascades and Sierra Nevada. They rested on Sunday and rode 5-15 miles daily the rest of the week. Families signed up with wagon masters and trail bosses who (hopefully) had experience. The Sierras can experience dramatic weather fluctuations regardless of season when storms from the Pacific collide with the mountains. The famous Donner Party was trapped in the Sierra range in an early November snowstorm after being sold an untested “shortcut” map of Nevada. They resorted to cannibalism before survivors stumbled out of the pass the following spring. In less extreme cases, snow could scare game away that trekkers relied on for food, as the animals migrated or went into hibernation. For a harsh depiction of the Oregon Trail after the Civil War, see Taylor Sheridan’s Yellowstone prequel 1883 (2021-22).

Oregon City on the Willamette River, John Mix Stanley, ca. 1850-52, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth

At their peak, thousands plied the well-worn trails in a given year, kicking up a thick cloud of dust that fell on those behind them. In the mid-1840s, congestion backed up the Oregon Trail in the summer. Oregon beckoned farmers hurt by the 1837 Panic and others, including European immigrants, seeking new opportunity in the fertile fields of the Willamette Valley — advertised back east as a “land of flowing milk and honey.” This was one area that wasn’t arid in the least, though they hadn’t been told how often it rained. The valley stretched south from their settlement at present-day Portland, or what they first called Oregon City. Some of the New Englanders who moved there wanted to name the new town at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers Boston, but they lost out to people from Portland, Maine in a coin toss (the Portland Penny is on display at the Oregon Historical Society).

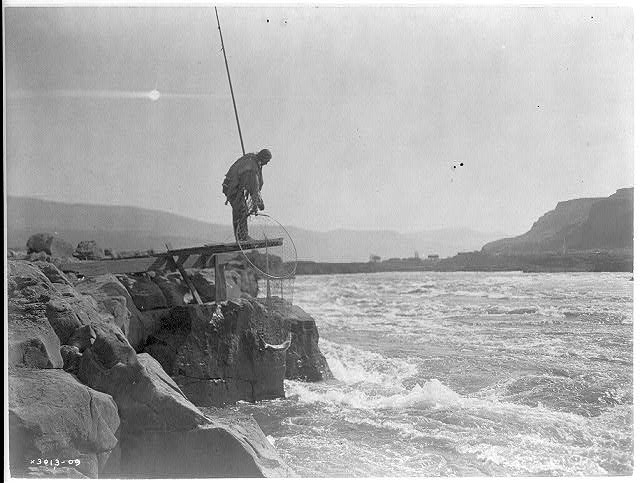

The Oregon Country included what we now think of as the entire Pacific Northwest, including Oregon, Washington, Idaho, a smidgen of western Montana, and all of (Canadian) British Columbia. It was a vast region sparsely populated by Indigenous Americans who relied mainly on fishing and a smattering of white fur traders and missionaries. Britain also made a claim on the area. Russia colonized as far east as Alaska, but Oregon was too far from Moscow for them to make any reasonable claim. The British and Americans decided on a novel plan, agreeing in 1816 to share the Columbia District for thirty years and argue about it later. In the meantime, most of the new settlers who moved into the southern portion of the territory were from the United States.

Wasco-Wishram (Tlakluit-Echeloot) Fishing Platform on Columbia River, Photo by Edward Curtis, 1910, Library of Congress

Because the Oregon Trail brought together strangers in close proximity, it conveyed diseases. Measles, cholera, and smallpox moved up and down the crowded trail, killing hordes of children, especially. To this day, tombstones mark portions of the trail. Eventually, these afflictions made their way to the end of the route, affecting Native Americans in Oregon and complicating the efforts of missionaries there. Western expansion coincided with the latter Great Awakening and Protestant missionaries like Marcus and Narcissa Whitman helped blaze the original trail west through the Rockies. In Oregon, they competed with Jesuits hoping to convert natives to Catholicism. Each side tried anything they could to convince the local population that the rival form of Christianity would lead them to damnation. Unable to overcome the language barrier, they showed Native Americans drawings (calendars they called them) to describe their respective faiths. The Protestant drawings depicted Martin Luther leading followers to Heaven with a Pope beckoning them to Hell. The Catholic version was essentially the same drawing upside down. Some missionaries threatened to turn off waterfalls if Indians didn’t convert, while others, out of desperation, threatened germ warfare.

Whitman Mission Near Walla Walla, From Samuel Clark, Pioneer Days Of Oregon History, Vol. 2, WikiCommons

While they didn’t actually have diseases at their disposal, some threatened to uncork vials of smallpox on Native Americans skeptical of Christianity. That came back to haunt the missionaries when smallpox and measles spread into the area for real. Naturally, some Indigenous Americans suspected that they had inflicted them deliberately. At Fort Walla Walla, in present-day southeastern Washington, Cayuse Indians killed a dozen Protestants in the Whitman Massacre. They cleaved open Marcus Whitman’s skull with a hatchet to release the evil spirits they thought dwelled there. Like the more famous Battle of Little Big Horn a generation later, the massacre played well into Americans’ agenda. It sanctioned retribution, leading to the deaths of many Northwest Indians in the ensuing Cayuse War and in spinoffs further south like the Rogue River Wars. They moved survivors onto reservations. As for who ultimately controlled the area, Americans and British agreed to split it 50-50 in 1846, with the British getting British Columbia and Americans getting the portion south of the 49º Parallel later subdivided into Oregon, Washington, and Idaho territories.

In the Bow, Qunhulahl, a Masked Man Personating the Thunderbird, Dances as Others Row to the Shore of the Bride’s Village, (Kwakiutl Tribe of British Columbia), Photo by Edward Curtis, 1914, Library of Congress

Mormon Trek & War

The Oregon Trail included Mormons, a hardy group of religious refugees who hauled their belongings across the Rockies by hand in the dead of winter. Mormonism grew out of the Second Great Awakening like dozens of other new denominations, but its story is especially interesting because it’s a thriving religion now, nationally and globally, and it was important then because Mormons were trailblazing western pioneers.

Joseph Smith Receiving the Golden Plates From the Angel Moroni at the Hill Cumorah, C.C.A. Christensen

Mormonism’s upstate New York birthplace was interesting in its own right because the Great Awakening spread there like such wildfire that it became known as the Burned-over District. Shakers, Millerites, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Spiritualists also called the area home. In the 1820s-’30s, Joseph Smith started the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) there after claiming to receive revelations on the Hill Cumorah from gold plates that came to be known as the Book of Mormon (re-titled by the LDS in 1981 as Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ). The angel Moroni was Smith’s treasure guardian that, according to later accounts, led him to the plates.

Mormons incorporated typical folk magic traditions of New England. Like his father, Smith was a scryer, meaning that he interpreted omens, signs, or instructions on how to find hidden treasures by peering into seer stones in the bottom of a white stovetop hat through a peep hole. He denounced scrying after being sued as an imposter by a Pennsylvania farmer upset over their failure to find silver with the method.

Eighteen months later, Smith found the gold plates under a rock, which he translated into English. Others said he used peep stones for the translation. He wouldn’t show skeptical editors the tablets, only the chest he said contained them and said they were in Reformed Egyptian, combining Egyptian language and Hebrew learning. Smith’s translation reads in a similar style to the King James Version of the Bible. According to Mark Twain, portions of the Book of Mormon were plagiarized directly. The LDS also considers the KJV Bible a sacred text, along with its Doctrine & Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price.

The Book of Mormon told how one of the Lost Tribes of Israel had made their way to America 600 years before Christ. The groups splintered and fought each other. Before the Nephites’ demise, Mormon recorded the story and bequeathed it to his son, Moroni, who buried the plates that Smith later found in upstate New York. God punished the victorious Lamanites by darkening their skin and turning them into the Indians who later greeted white explorers. Christ himself appeared in the Americas shortly after his resurrection (3 Nephi 11). Toward the end of his life, Smith’s unfinished work The Book of Abraham (1835- ) also described the planet/star Kolob as the heavenly body nearest to God’s throne, and where Earth was created 6k years ago before being relocated to its current solar system. Mormon director Glen Larson later featured Kolob in his Battlestar Galactica TV series (1978, 1980 & 2003-9). Smith, a Freemason, added several Masonic-like rituals to the Mormon’s ceremonies (similarities).

The persecution Mormons suffered at the hands of other Americans helped forge their bonds, as has been the case with other religions in other places, but numerous early followers nonetheless became disenchanted with Smith after he led the group to Kirtland, Ohio. Smith led a revamped group to Jackson County, Missouri in 1838, where Mormons encountered some of the harshest persecution ever aimed at an American religious sect. After several violent disputes between Mormons and local “Gentiles” as they called them, the state’s governor issued an extermination order, Missouri Executive Order 44, to kill all Mormons or drive them out of the state. They escaped and thrived by building Nauvoo, Illinois, a bustling town on the Mississippi River.

As early as 1832, Smith practiced polygamy, a tradition common in some parts of the world but not in Western civilization. He claimed an angel of God appeared before him with a drawn sword and commanded him to preach polygamy or face destruction. His wife, Emma Smith, denied that Joseph himself ever had multiple wives, but other sources indicate he had between 30 and 33. In any event, polygamy gave mainstream Christians more cause to scorn Mormons beyond their holding of communal property and a third testament grafted onto the Judeo-Christian Bible, especially as they argued after 1852 that God and Jesus himself were polygamists.

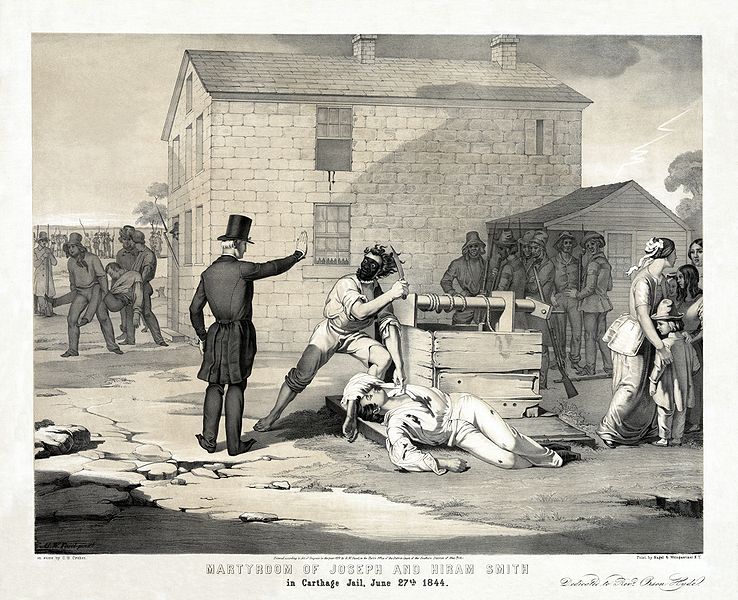

An angry mob broke into the jail in nearby Carthage where Smith was being held for destroying an opponent’s press in 1844. They shot his brother Hyrum dead through the front door. They shot Joseph and either pushed him out of the second-story window or he fell or jumped out. Artistic renditions of Smith’s death vary widely. Some show him martyring himself by leaping out the window while others have a beam of light from heaven protecting his body from mutilation. Purportedly, his last words were “Oh Lord my God” (the first part of the Masonic cry of distress).

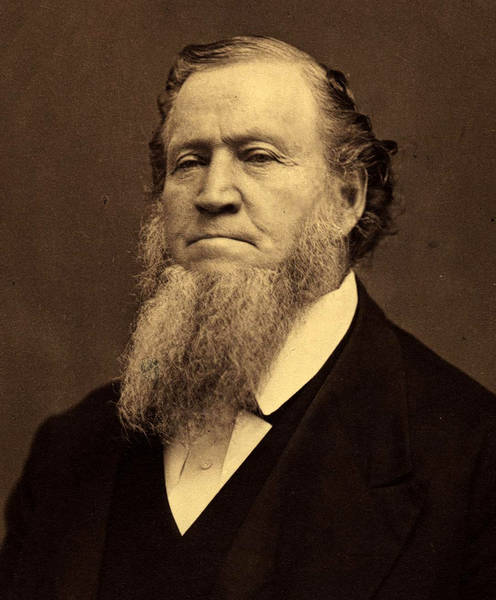

Mormons found that American religious freedom had its limits and left the U.S. for a sparsely populated part of northern Mexico later called Utah. Some escaped to Texas but most followed their new leader Brigham Young, head of the polygamist faction, to found their own country. Like the Old Testament figure who led enslaved Jews out of Egypt, the “Mormon Moses” led his dedicated band west through the snow in 1846-47, breaking through South Pass in the Rockies and declaring the Salt Lake Valley in the Great Basin as their new Zion (Jerusalem), or Promised Land. More handcart pioneers followed in the 1850s, laboriously hauling two-wheeled carts all the way from the railroad’s western terminus at Iowa City across the Plains and Rockies to Utah.

Mormon Pioneers Crossing Platte River in Nebraska, Re-Enactment From PBS Documentary “Sweetwater Rescue,” WikiCommons

Take a few minutes to orient yourself with this Animated Map of western trails. Along the way, Mormons ran into famous scout Jim Bridger, who told them that California and Oregon were both opening up to American settlement. That nixed both those options. Despite being in northern Mexico, Young and his followers claimed most of the Southwest as their own, naming it Deseret from a phrase in the Book of Mormon meaning a hive of busy bees. Deseret became part of the U.S. the next year, after the Mexican War of 1846-48. They called its capital “Great Salt Lake City.”

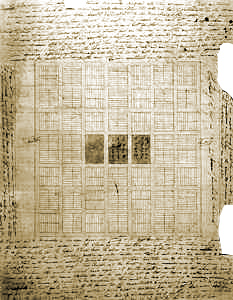

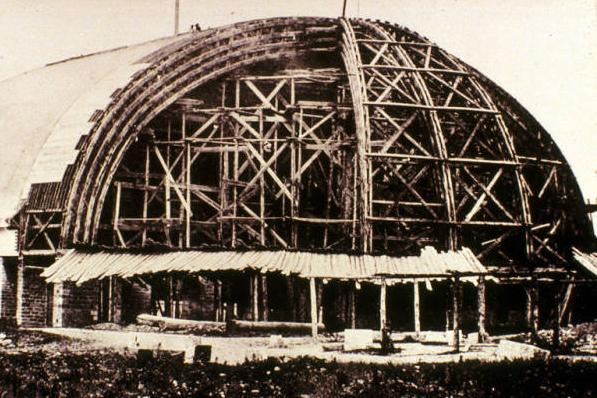

Salt Lake City quickly grew into the most prosperous city in the West, with beautiful homes, broad boulevards, little crime, and a large tabernacle built over a series of years like the Gothic Cathedrals of Europe, if more rudimentary. Inspired by their fallen leader Smith’s Plat of the City of Zion (in turn inspired by Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance), they created a grid of dispersed urban farmers. Young ordered that the streets be wide enough for a wagon to turn around without “resorting to profanity.” Elsewhere in the Great Basin, they applied Smith’s Plat to Orem, Moab, St. George, and Provo, Utah, now home to Young’s namesake university.

Mormons were tough and resourceful. They overcame a plague of crickets and irrigated the Salt Lake Valley, transforming the desert into fertile farms. Polygamy hadn’t helped Mormons much in Illinois, but its utility became apparent out west. Frontiers, in general, kill off more men than women, and polygamy provided widows with new homes. Also, Missourians had killed mainly male Mormons after Executive Order 44, leaving many widows homeless. That imbalance no doubt contributed to Smith’s revelation to preach polygamy.

For a while, the Latter-Day Saints were safely out of the government’s reach but, by the 1850s, the U.S. viewed the sect as a burr in its saddle. In 1857, some Mormons slaughtered a wagon train of Arkansans on their way to California. Disguised as Paiute Indians, the Mormons first hoped to only harass or rob them, suspecting that some of the settlers had been involved in the Haun’s Mill Massacre of 1838 back in Missouri. But the settlers circled their wagons in classic fashion, leading to a five-day standoff. Mormons didn’t want word of what was happening to get out and panicked. They sent in a state militia pretending to act as intermediaries, asking the Arkansans to hand over their weapons in exchange for safe passage, then betrayed them and killed 120, allowing 17 under the age of seven to live.

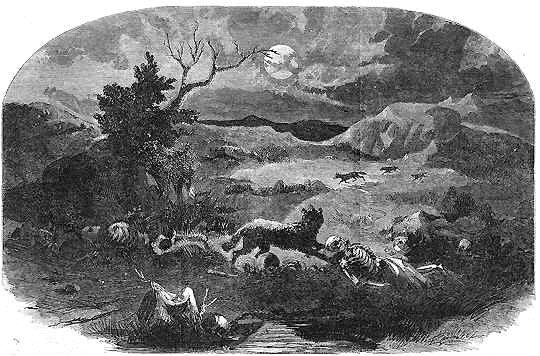

Brigham Young distanced himself from the Mountain Meadows Massacre, the biggest mass murder in U.S. history prior to the Oklahoma City bombings in 1995. But the murders played directly into the hands of Easterners who carried a grudge against Mormons to start with, giving them the pretext for revenge. Harper’s Weekly relayed the graphic scene as “one too horrible and sickening for language to describe,” though they gave it a try: “Human skulls, disjointed bones, ghastly skulls and the hair of women were scattered in frightful profusion over a distance of two miles. The remains were not buried at all until after they’d been dismembered by the wolves and the flesh stripped from the bones.”

There’s often a bigger context to these stories and, in this case, mass murder, polygamy, and territorial land claims got entangled in the broader sectional crisis back east. President James Buchanan saw war against Mormons as a way to unite feuding Northerners and Southerners — or, as historians allege, a cowardly way to dodge the more intractable issues of sectionalism. The actual Mormon War never really materialized. The army bogged down in a Rocky Mountain snowstorm and, like the Whiskey Rebels of 1794 and South Carolina Tariff Nullifiers of 1833, Mormons were not about to take on the U.S. anyway. Nonetheless, the show of force allowed the U.S. to take control of the region. “Buchanan’s Blunder” at least succeeded in shrinking Deseret down to a smaller section called Utah after the local Utes, in the process redefining the territorial borders, including Nevada and western Colorado. And the U.S. banned polygamy in that smaller territory.

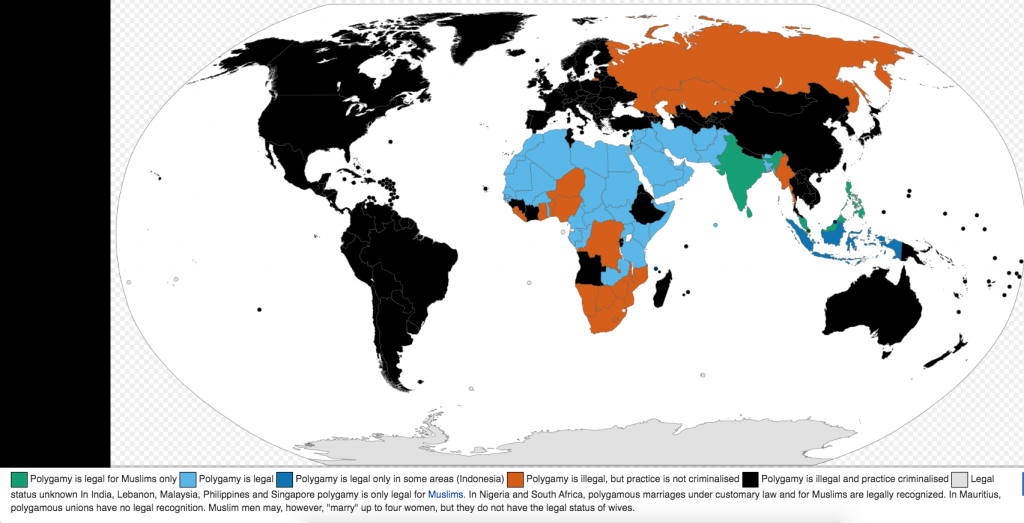

Polygamy became an important test case for the First Amendment right to religious freedom. In Reynolds v. U.S. (1878), the Supreme Court distinguished religious freedom from religious practice, supporting the government’s ban on polygamy in the new territory. The Court cited Thomas Jefferson’s 1802 Letter to the Danbury Baptists, in which he wrote that “the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions.” Failure to distinguish between freedom (opinions) and practice (actions) would, in theory, legalize far worse than polygamy, like human sacrifice for example. Religious freedom couldn’t override other parts of the penal code. The Supreme Court buttressed their polygamy ban (i.e. the constitutionality of the 1862 Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act signed by Abraham Lincoln) on English common law tradition and definitions of marriage dating back to the laws of King James I. The federal government gave Mormons leeway before enforcement kicked in, especially with the Civil War going on. They grandfathered the law, in other words. President Lincoln compared Mormonism to a type of log he’d encountered farming that was “too hard to split, too wet to burn and too heavy to move, so we plow around it…you go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone, I will let him alone.” Even by the 1860s, the West still wasn’t really controlled by the U.S. However, in 1882 the Edmunds Act made polygamy a felony. Had he been alive, that would’ve made, among others, the Cherokee linguist, soldier, and diplomat Sequoyah a felon. The Mormon Church ceased performing new polygamous marriages in 1890 and Utah became a state in 1896. They banned polygamous marriages outright in 1904. Here’s a map of where polygamy is currently legal worldwide:

Gold Rush

Further west, a town altogether different than Salt Lake City sprung up later named San Francisco, known then as Yerba Buena Cove. The “city by the bay” and Salt Lake City were as different as Puritan New England and Virginia were in colonial times. San Francisco was an excellent deepwater harbor that would have become a major city someday, regardless. But it boomed starting in 1848 because carpenter James Marshall discovered gold inland on miller John Sutter’s land, along the South Fork of the American River. Sacramento sprouted up around Sutter’s Fort and became the state capital two years later. California grew so quickly that it skipped territorial status and became a state in 1850.

The sought-after nuggets came from deep in the Earth’s crust. Like volcanic magma, gold magma seeps up to the surface over a geological subduction zone, in this case where the Pacific plate runs under the North American plate. Geologists estimate that ~80% of the gold in California is still un-mined. News of the treasure spread around the world, especially after the New York Herald reported the strike in August 1848. By the following spring, Forty-Niners from the U.S., South America, Europe, and Asia descended on northern California, becoming the Golden State’s “founding fathers.” It was far bigger than America’s first two gold rushes — North Carolina 1799 and Georgia 1828 — because there was more gold and the land was unclaimed. Six more strikes followed that of Marshall at Sutter’s Mill. Even the crews of the ships that brought the 49’ers rushed to the goldfields, leaving their ships behind unguarded. So many abandoned ships clogged the harbor that the city sank them, poured sand on top, extended the city, and built new piers further out in the bay. Like Manhattan, San Francisco expanded on a garbage foundation.

As is usually the case, those “mining the miners” made out best, or at least earned money most consistently. Sam Brannan, a general store owner near Sutter’s Mill that stood to profit, was first to spread the news. Real estate, prostitution, and hardware were thriving industries and, to this day, some investors say a pick-and-shovel play is better than investing directly in whatever is currently standing in for gold. Too many people try that and only a few can get rich, so better to be the one selling the picks, axes, and shovels to the miners. Unscrupulous merchants even advertised false claims then sold tools to everyone who rushed in that direction. Arsonists set fires to San Francisco hotels on the theory that miners would be gone or wouldn’t take the time to retrieve their gold as they rushed out of the building; then the arsonists moved in and mined the ashes.

Other businessmen were more legitimate. Some hunted professionally, especially ducks, to feed San Francisco’s population as it boomed from 1k to 25k in 1849 with few nearby wheat or corn fields. Domingo Ghirardelli, who migrated from Italy via South America, sold chocolate while James Folger of New England sold canned coffee that could be easily transported to the mining fields. Isidore Boudin from Burgundy, France established a sourdough bread bakery that still uses its original “mother dough” from the Gold Rush era. Robber Baron Leland Stanford used the money he made selling groceries and supplies to miners to stake his claim in politics, railroads, and later his namesake university. Entrepreneur and real estate mogul Mary Ellen Pleasant (right) became the first African-American millionaire in American history, later contributing money to abolitionist causes. Levi Strauss learned that miners were tearing up their trousers, so he backed a designer who’d developed copper rivets to hold denim pants together better, in the process inventing the world’s most famous blue jeans (blue jeans, formerly known as blue-dyed “negro cloth,” have a long history that predates riveted jeans). Next time you pull on a pair of 501’s®, you can thank the Pacific plate for running under North America and creating gold magma.

Other businessmen were more legitimate. Some hunted professionally, especially ducks, to feed San Francisco’s population as it boomed from 1k to 25k in 1849 with few nearby wheat or corn fields. Domingo Ghirardelli, who migrated from Italy via South America, sold chocolate while James Folger of New England sold canned coffee that could be easily transported to the mining fields. Isidore Boudin from Burgundy, France established a sourdough bread bakery that still uses its original “mother dough” from the Gold Rush era. Robber Baron Leland Stanford used the money he made selling groceries and supplies to miners to stake his claim in politics, railroads, and later his namesake university. Entrepreneur and real estate mogul Mary Ellen Pleasant (right) became the first African-American millionaire in American history, later contributing money to abolitionist causes. Levi Strauss learned that miners were tearing up their trousers, so he backed a designer who’d developed copper rivets to hold denim pants together better, in the process inventing the world’s most famous blue jeans (blue jeans, formerly known as blue-dyed “negro cloth,” have a long history that predates riveted jeans). Next time you pull on a pair of 501’s®, you can thank the Pacific plate for running under North America and creating gold magma.

Meanwhile, those that sought the actual gold found themselves waist-deep in ice-cold streams, panning silt to filter the tiny nuggets. The “Ballad of the Lousy Miner” captured their plight. Others re-routed rivers and streams into more elaborate sluices. Placer gold in rivers indicated more substantial ore deposits nearby, and larger outfits dug out mines. Indeed, some made it rich, but less than 5% came home with any appreciable wealth. Most struggled for small scraps of gold dust that wasn’t enough to buy food or pay rent. Many gambled and drank away their measly earnings. At first, it was a multi-cultural operation, including some free Blacks. There were already Cantonese merchants living in the area before gold was discovered, who spread the word to Asia. But, after being kicked out of mining, Chinese retreated to service industries like restaurants and laundries in their Chinatown enclave back in San Francisco, the nation’s most famous. For these immigrants, Chinatown became their promised “gold mountain.”

Other minorities didn’t fare so well. Americans tossed out the agreements they made with Hispanics at the end of the Mexican War, disenfranchised them, and took their land. When they protested, newcomers bogged them down in court cases so lengthy they induced bankruptcy. As in Texas, newcomers were less sympathetic than Whites who’d lived in the area alongside Californios, such as the Boston merchants who arrived in the 1830s.

Similar to the termination order Missouri’s governor put on Mormons, county officials in northern California offered $5 for severed Indian heads, redeemable at their offices in Shasta City. One resident remembered seeing settlers ride into town with eight or ten heads hanging from their mules. Yes, you read that correctly; officials paid citizens cash for severed Native American heads. Other jurisdictions paid for scalps, with men, women, and children fetching different rates. The state government got into the act, too, leading an expedition against Indians along the Pitt River in 1859. Journalists are prone to exaggeration, but here’s what San Francisco’s Alta California newspaper reported on the efforts of their militia near Fort Crook:

The camp was taken completely by surprise, as the Indians knew that they [w]ere innocent of any depredations, and were confident in the kind feelings of the whites towards them. The attacking party rushed upon them, blowing out their brains and splitting their heads open with tomahawks. Little children in baskets, and even babes, had their heads smashed to pieces or cut open….The children, scarcely able to run, toddled toward the squaws for protection, crying with fright, but were overtaken, slaughtered like wild animals and thrown into piles. (Source CDNC)

Eight years earlier, Governor Peter Burnett wrote, “A war of extermination will continue to be waged…until the Indian race becomes extinct.” In 1852, the California Legislature paid militias $1.1 million to kill Indigenous Americans. Officials statewide backed white squatters and crimes by individual Native Americans were punishable by wiping out their entire home village. Lynching Mexican-Americans, moreover, was common. Genocide is not a term we should take lightly or overuse, so as to prevent robbing it of its meaning (deliberate extermination). But we have seen two genocidal policies enacted in this chapter, both by local governments.

San Francisco set the blueprint for mining towns elsewhere – Reno (silver), Denver (gold, silver, lead, copper), Phoenix (gold), Boise/Idaho City (gold), Butte (copper, silver, gold), and Seattle (gateway to Alaskan gold) also boomed and survived. These towns, too, had successful “pick-and-axers.” Born sixty miles south of the Arctic Circle, Swedish immigrant Johan Nordström moved to Seattle at sixteen and supplied shoes to miners headed to the Klondike Gold Rush in Alaska, using seed money from his own gold claims. Dozens of other settlements, like Bannack, Montana, died away as ghost towns once their mines went bust (or streams in Bannack’s case).

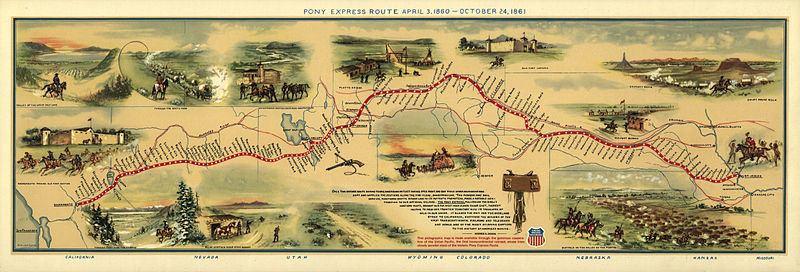

The Wild West of these mining towns gave the era and region its distinctive flavor, along with cowboys of the next generation. Gold Rush-era songs included “Oh! Susanna” and a Mexican tune later Anglicized into “Oh My Darling, Clementine.” Meanwhile, further east, Americans fretted over the West’s future economy. California was really a separate economy with plenty of its own currency (gold bullion), spurring national politicians into settling the West faster than they otherwise might have. Abraham Lincoln, in particular, promoted construction of the transcontinental telegraph and railroad to northern California in the 1860s for that reason, and the Pony Express followed more or less the same route. But even a decade before, California’s growth helped trigger the sectional crisis between North and South. Would planters import enslaved workers there or would the 49’ers that came to mine gold and service miners take control? The balance of power for the whole country was at stake.

Optional Reading & Viewing:

Joseph Smith Papers (Church Historians’ Press)

Joseph Smith-History, Extracts From the History of Joseph Smith, the Prophet (CJCLDS)

Cameron Addis, “The Whitman Massacre: Religion & Manifest Destiny on the Columbia Plateau, 1809-1858” (Journal of the Early Republic, 2005)

Gilbert King, “The Aftermath of Mountain Meadows” (Smithsonian, n.d.)