“England provided the time, America provided the money, and Russia provided the blood.“ — Joseph Stalin?

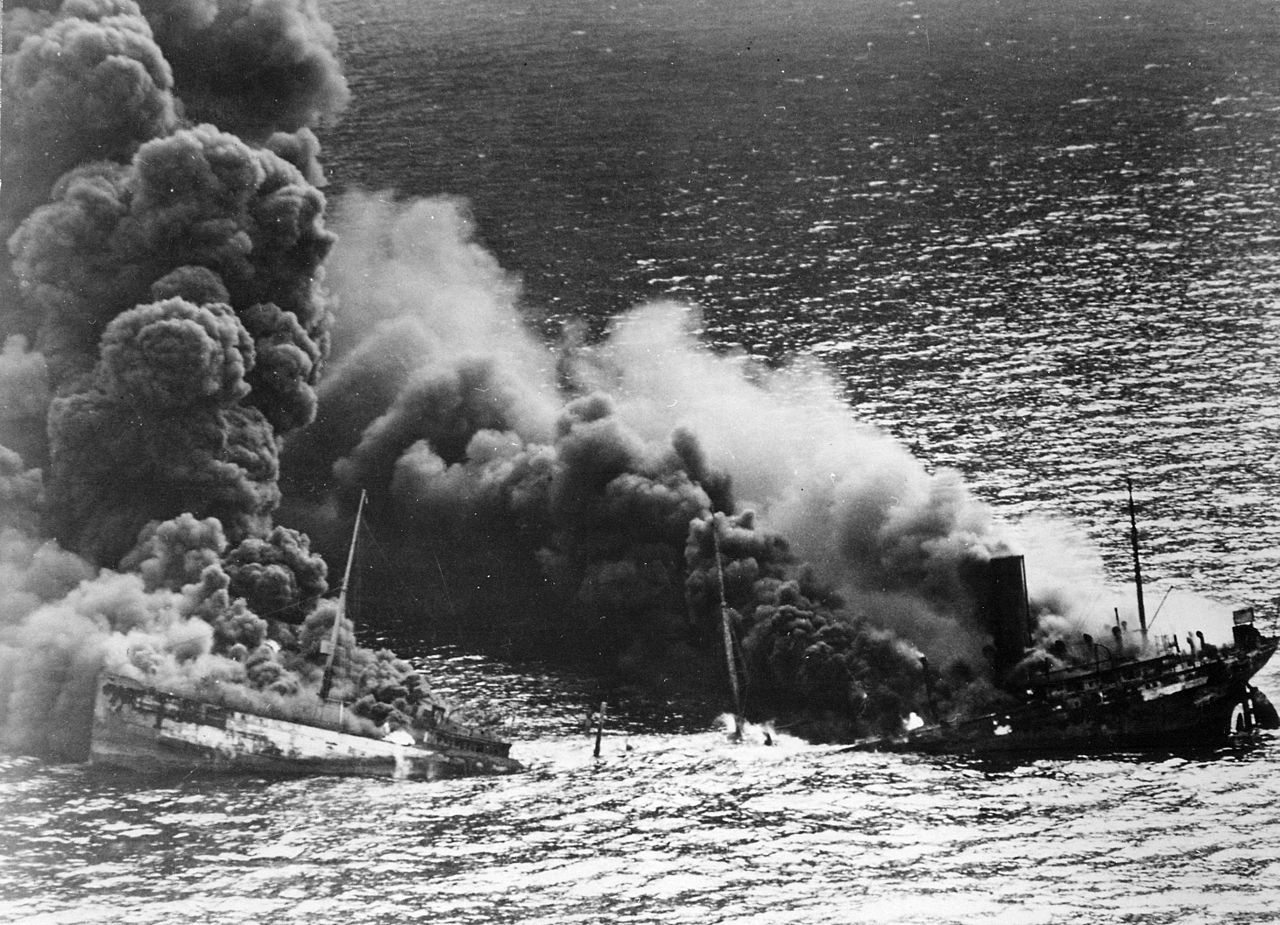

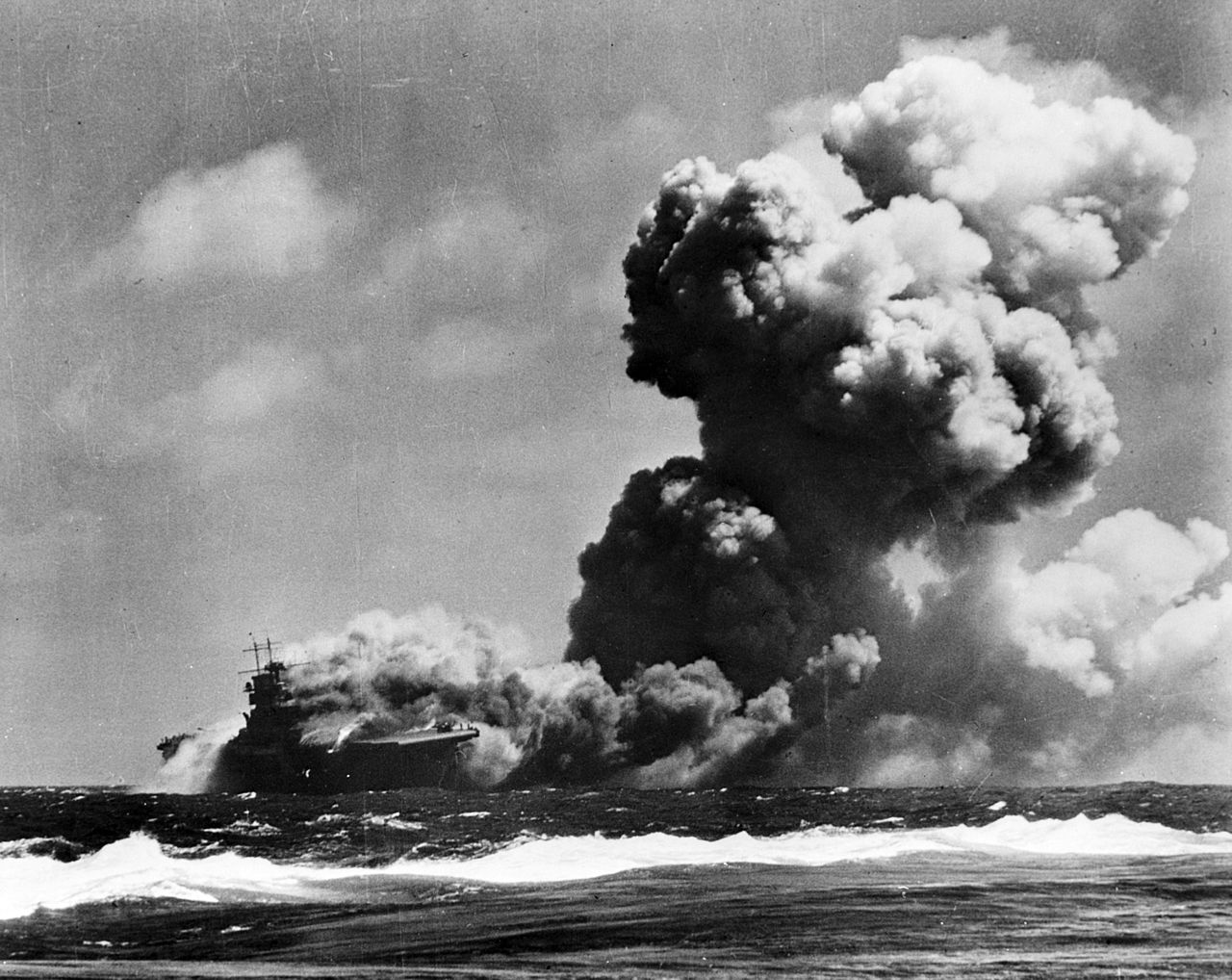

U.S. Aircraft Carrier USS Wasp (CV-7) After Three Torpedo Hits From Japanese Submarine in Solomon Islands, 15 September 1942, Library of Congress

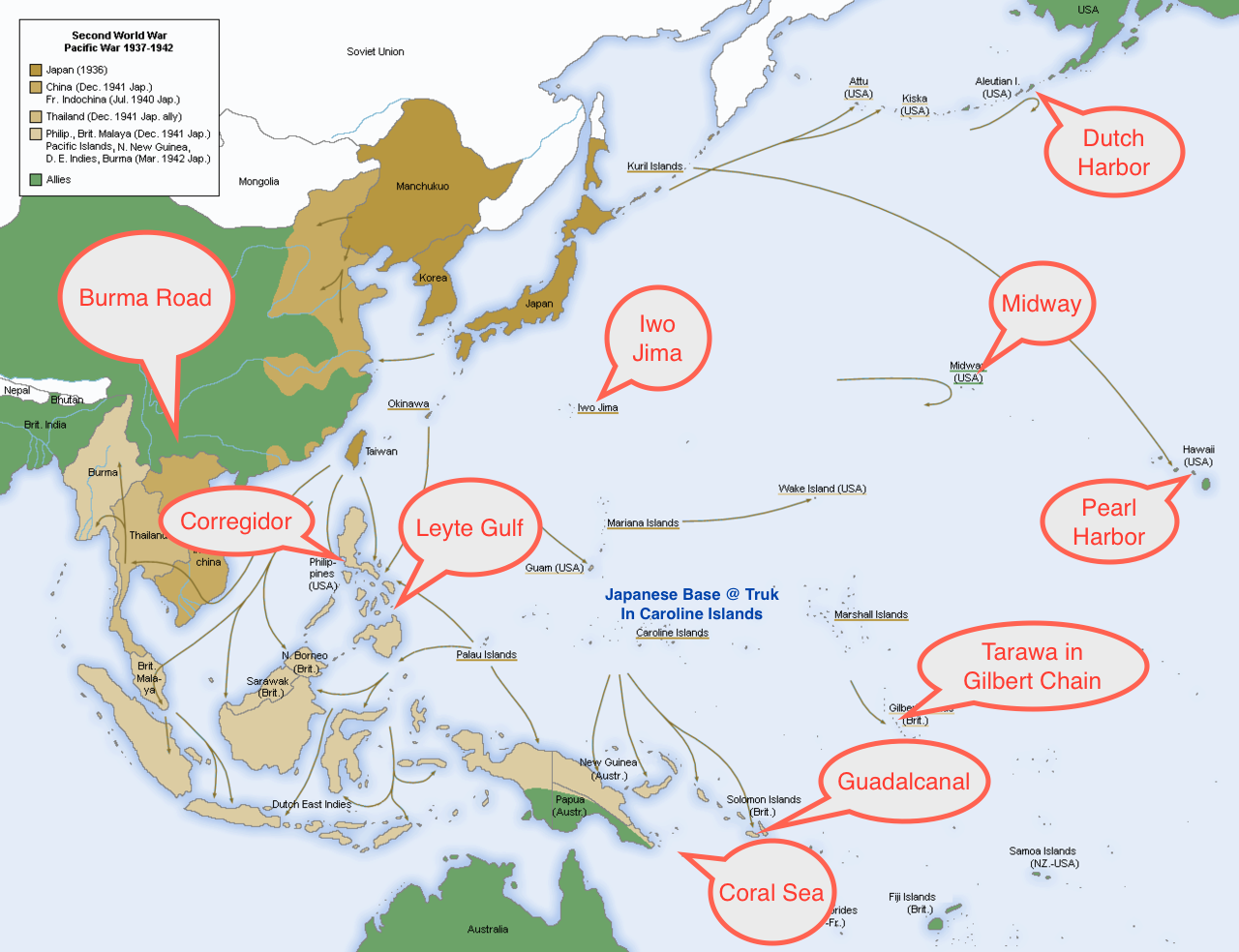

Japan’s attacks in December 1941 weren’t limited to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Within days, Japan attacked Americans in the Philippines and Guam, seized much of the Dutch-held East Indies (Indonesia), conquered British Hong Kong and, by February 1942, decimated British forces at the “impregnable fortress” of Singapore. Singapore was well defended by sea, which is why the Japanese pedaled in from the northern mainland of Malaya (Malaysia) in the “Bicycle Blitz,” also using light enough tanks to negotiate the Malayan jungle. After what Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the “largest capitulation in British history,” the Royal Navy’s long run as ruler of the world’s seas was over. The Japanese massacred 50k Chinese civilians in Singapore while most of the 80k British POW’s eventually died. On December 8th, the day after Pearl Harbor, Japan destroyed America’s undefended airplanes at Clark Air Field and Fort Stotsenburg in the Philippines before they got off the ground. Beleaguered and injured troops retreated to Corregidor Island in Manila Bay with no support to reach them. America’s inter-war strategists had only hoped that, in the event of an attack, their territories in the far western Pacific could hold out on their own as the Navy mustered its fleet in California and Hawaii and focused on protecting the Panama Canal (War Plan Orange).

American troops on Corregidor ran low on supplies and had to surrender after FDR ordered their commander, Douglas MacArthur, to evacuate. “Mac” vowed he’d return to the Philippines and did, in 1944, but not in time to save most of his people. The 15k American troops surrendering after the Battle of Bataan (along with 60k Filipinos) was the most since 12k Union troops surrendered to Confederates at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in 1862. The Japanese didn’t respect surrender and treated the soldiers harshly on a long 65-mile Death March up the Bataan Peninsula. Stragglers, like those who broke an ankle or collapsed from heat exhaustion, were clubbed, bayoneted, shot, or beheaded to set an example for the others. They taunted those dying of thirst by putting them near wells then shooting them when they dove for water. Survivors barely stayed alive once they made it to camps at Santo Tomas or Los Baños and even those that did suffered from malnutrition. The Japanese didn’t bury dead POWs, instead throwing them into rat- and maggot-infested piles to decompose. They didn’t rape or even harm captured female nurses, but neither did they give them the proper supplies and medicine to care for male prisoners. Since 1989, veterans have held an annual Bataan Memorial Death March at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico that now includes wounded veterans from other wars, family members, and any supporters on a 26-mile hike through the desert.

American troops on Corregidor ran low on supplies and had to surrender after FDR ordered their commander, Douglas MacArthur, to evacuate. “Mac” vowed he’d return to the Philippines and did, in 1944, but not in time to save most of his people. The 15k American troops surrendering after the Battle of Bataan (along with 60k Filipinos) was the most since 12k Union troops surrendered to Confederates at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in 1862. The Japanese didn’t respect surrender and treated the soldiers harshly on a long 65-mile Death March up the Bataan Peninsula. Stragglers, like those who broke an ankle or collapsed from heat exhaustion, were clubbed, bayoneted, shot, or beheaded to set an example for the others. They taunted those dying of thirst by putting them near wells then shooting them when they dove for water. Survivors barely stayed alive once they made it to camps at Santo Tomas or Los Baños and even those that did suffered from malnutrition. The Japanese didn’t bury dead POWs, instead throwing them into rat- and maggot-infested piles to decompose. They didn’t rape or even harm captured female nurses, but neither did they give them the proper supplies and medicine to care for male prisoners. Since 1989, veterans have held an annual Bataan Memorial Death March at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico that now includes wounded veterans from other wars, family members, and any supporters on a 26-mile hike through the desert.

Some Japanese talked about taking over Africa, Latin America, and the western United States. In March 1942, LIFE magazine ran illustrations of Japanese troops marching past Mt. Rainier (Washington), American demolition teams blowing up the Golden Gate Bridge as they retreated, and firefights in California gas stations. There were only 100k U.S. troops guarding the entire West Coast. Major General Joseph Stilwell, in charge of the California portion, wrote in his diary, “If the Japs had only known, they could have landed anywhere on the coast, and after our handful of ammunition was gone, they could have shot us like pigs in a pen.”

In Europe, Germany held most of the continent and North Africa and was knocking on the door of Moscow and Leningrad in the Soviet Union. In North Africa, Germany threatened the British-held Suez Canal, Europe’s gateway to Persian Gulf oil. As of early 1942, neither Imperial Japan nor Nazi-led German forces had ever been defeated on the battlefield. The Japanese Navy hadn’t lost a major battle since the country modernized in the mid-19th century and they now controlled the entire western Pacific. They gambled they could secure most of Asia before the U.S. got back up on its feet after Pearl Harbor and were right. It was months before the U.S. mobilized its forces and got troops into the Pacific. Animated Map

Allied Strategy

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall had to lead two wars simultaneously. Should America fight both at the same time? If not, which first? The U.S. fought both wars at once, in the process growing their military 40-fold in comparison with what it was in 1940 when it was the 17th-biggest force worldwide. If there was an upside to this challenge, America could fight when and where they wanted since, LIFE magazine aside, the continental U.S. didn’t seem imminently threatened for the time being. They started by mainly trying to defend American territory in the Pacific rather than going on the offensive. Roosevelt told Churchill what he wanted to hear by confirming their “Germany First” strategy but Britain had interests in the Pacific as well. Really, they fought in both theaters at more or less the same rate, with American “boots on the ground” in Asia six months earlier than Europe (North Africa). The American public put a higher priority on fighting Japan who, unlike Germany, had attacked them, but FDR emphasized keeping Britain afloat and opening up Atlantic shipping lanes.

American planners saw Germany as a bigger long-term potential threat to the U.S. than Japan, and England as a sort of giant stationary aircraft carrier from which the U.S. and Britain could bomb Germany. The Pentagon wanted to invade German-held France and move toward Germany on the ground, but Churchill didn’t want a rerun of the previous war with its stalemated Western Front and argued that a failed offensive in France would lose the war. This makes one wonder how exactly the (out-of-office) Churchill was proposing to take a stand against Hitler in 1938 when he derided Neville Chamberlain for signing the Munich Pact. To stop Nazi expansion then likely would’ve required Britain to take a stand in Europe, not just defend itself by air and sea as they did in the 1940-41 Battle of Britain (previous chapter). To the chagrin of some U.S. brass in 1941, Churchill favored fighting Germany in North Africa first to protect Middle Eastern oil and FDR went along with him. While the Western Allies figured out what to do, Germany unwisely focused on its eastern offensive in the Soviet Union.

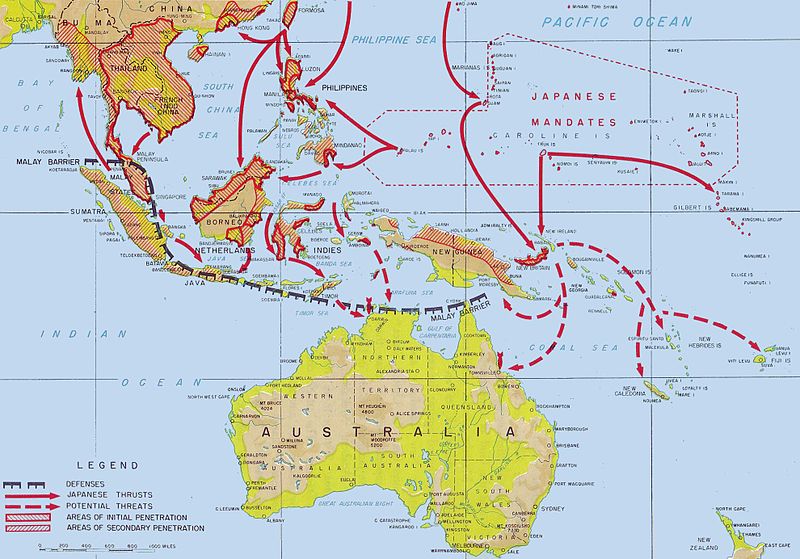

In Asia, American forces couldn’t get at the home island of Japan directly. Planes couldn’t carry enough fuel to make round-trip bombing missions over Japan from any American or British-held points, whether in western China, Hawaii, or Alaska. Their first two objectives were to secure the Burma Road— a makeshift supply route Chinese and Burmese built with hand-held tools (above) to connect them to British-held Burma — and defend the connection across the southern Pacific between the U.S. mainland, Hawaii, and Australia. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with the basics of this map marking spots we’ll be discussing in this chapter and the next.

Pacific War Strategy

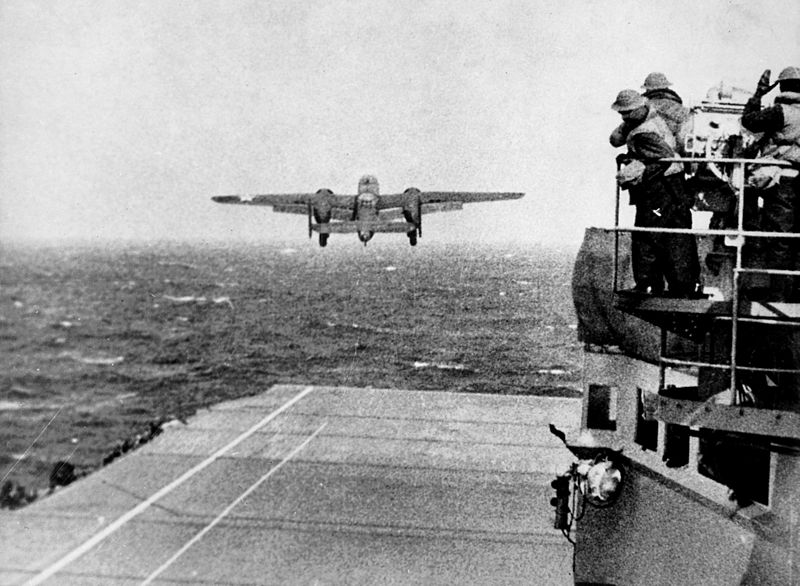

Partly to pique public interest — it had been six months since Pearl Harbor — and partly to inflict damage, the U.S. ran some one-way strategic bombing missions over Japan, known as the Doolittle Raids after their leader, Jimmy Doolittle, an aeronautical whiz kid with a PhD from M.I.T. The bombing mission did minimal damage but they had a large impact on the war because of Japan’s inhumane overreaction and their misunderstanding that the pilots took off from Midway, about which more later. The B-25 Mitchells really took off from the USS Hornet aircraft carrier (below) and crash-landed in China, each pilot with no more on his person than an M1911 pistol, combat knife, map, and compass. In Hollywood’s Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), starring Spencer Tracy as Doolittle, the pilots’ Chinese allies sing the “Star-Spangled Banner” in Mandarin after the survivors regroup in Chungking. The attacks surprised and confused Japan since medium bombers weren’t commonly thought capable of taking off from the short 500-foot runway afforded by even the largest carriers (in videos, they look almost like they’re in slow motion). FDR facetiously and discreetly told reporters they took off from Shangri-La, a mythological place of perpetual youth in the Himalayas. In retribution for the raid, the Japanese tortured and slaughtered a quarter million Chinese in the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign — raping, drowning, dismembering, and infecting local populations with cholera, plague, and typhoid — and threatened to do likewise if the U.S. ever attacked them again. Amidst fractured Sino-American relations today, elders from the Zhejiang and Jiangxi provinces still celebrate reunions with the Children of the Doolittle Raiders.

Aside from the Doolittle Raids, America employed a peripheral strategy in the Pacific, painstakingly nibbling away at Japan’s vast empire from the perimeter in. It fell to Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz‘ Navy and Marines (naval infantry) to gradually retake tiny islands in the Pacific, including the Marshall, Gilbert, Caroline, and Mariana chains, until they worked their way back to within striking range of Japan. Island-hopping cleared shipping lanes for destroyers, cruisers, and aircraft carriers, which were even more valuable than islands as mobile runways. Moreover, they needed to clear Japanese forces from the oil and rubber-rich areas in the outer part of their conquered territory to undermine their war machine. Military brass in Washington remained skeptical of aircraft carriers, though, because they were expensive, lumbering targets that didn’t have a strong track record until later in the war. While “flat-tops” were relatively new, the Naval War College had planned island-hopping as a prelude to an eventual blockade and invasion of Japan as far back as 1906.

The U.S. leapfrogged most insignificant or heavily fortified islands if there was an easier target beyond it. They called this strategy “hitting ’em where they ain’t” after a baseball phrase. Simultaneous to the Central Pacific island campaign, the Army, Marines, and Navy led by Bull Halsey hop-scotched their way up the bigger islands of the Indonesian archipelago (New Guinea and Borneo) toward the Philippines under Douglas MacArthur. The Army and Nimitz-led Navy to the north were both unhappy with this compromise arrangement and jealous of resources sent to the other, but their rivalry worked out for the best insofar as they raced each other toward Japan. Still, after the war the U.S. merged their armed forces at the top, creating the Joint Chiefs of Staff to better coordinate the branches.

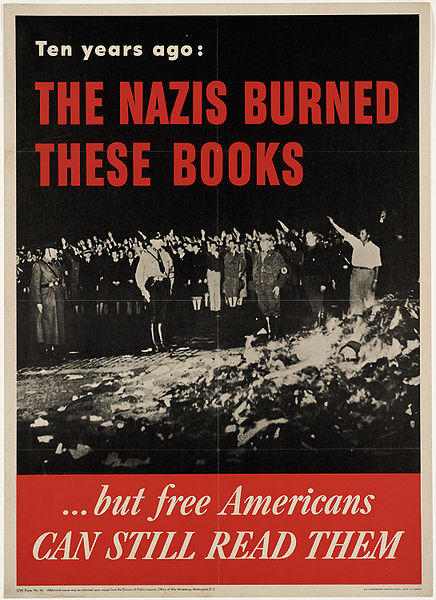

Contributors included more than just combat soldiers and sailors. War would be impossible without non-combatants, some of whom end up in harm’s way. The Merchant Marine and other military personnel formed a vast supply chain back across the Pacific for weapons, ammo, oil, food, mail, etc. Over a billion cigarettes made their way to the front. Armed Forces mechanics repaired equipment and disassembled destroyed aircraft for salvage parts. The Auxiliary Corps included medics (doctors and nurses) and chaplains. None of these people were necessarily safe by virtue of being “behind the lines.” Seventeen times in the Pacific theater, Artie Shaw’s Navy jazz band came under fire while entertaining troops (swing music was a kind of an informal Allied soundtrack to WWII and culturally symbolic in Europe as Nazis considered it sub-human and broadcast mock jazz songs lampooning America). The Navy put the Merchant Marine and Coast Guard under their control for the war’s duration, but their ships were more lightly armed despite being subject to attack. There wasn’t a separate Air Force branch until after the war, but all the branches had pilots and planes, including the Army Air Forces (USAAF). The Pacific War was a massive logistical challenge that succeeded with top-down organization.

The U.S. coveted small islands mainly as spots to build runways on. Planes could then take off from the new airstrip to help soften up the next island. There, Marines landed on the beach while the Navy bombed the island from offshore. Early on, especially, friendly fire sometimes hit the Marines as they landed if the range wasn’t set just right on the Navy’s guns. Wearing hundreds of pounds of gear, seasick Marines waded up on the beach after the front of their Higgins boat dropped open into the maw of enemy fire, desperately trying to find cover before being shot. Survivors worked their way through the jungle trying to root the Japanese out of their bunkers or nests. The pillbox bunkers had holes just large enough for the man inside to point his gun out so Americans shot fire into the hole to burn the soldier to death. If he ran out in a banzai attack, they fought hand-to-hand with a bayonet unless he could be gunned down first. The Japanese rarely surrendered, partly because it went against their Bushido Code and partly because U.S. troops sometimes killed prisoners in retaliation for their own harsh treatment in Japanese POW camps. Lucky Japanese POWs were treated well on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay where the Americans’ top priority was to bug their cells. By listening in on conversations, Japanese-American intelligence officers gradually pieced together an idea of Japan’s naval command structure and which boats covered which parts of the Pacific. Guards kept their sources comfortable and well-fed.

As they fought Japanese, Americans in the Pacific also fought humidity, snakes, jungle rot, and boredom. Snipers climbing trees in the Solomon Islands feared ant nests more than the Japanese. After securing the island, their next objective was to chop down palm trees and build an airstrip as quickly as possible, even though not all the Japanese were usually gone by then and the construction battalions (Seabees or CB’s) were subject to sniper fire. The Seabees were the Navy’s version of the Army Corps of Engineers. It’s easy to overlook engineers’ role in warfare, but crews had to build all the bases, hospitals, roads, piers, tanks, installation points, and airports that made the Pacific campaign possible. Railroad crews, likewise, allowed Allied forces to move around Europe after retreating armies destroyed existing tracks. In the Pacific, the U.S. could ship and store blood, medicine, and food because of the mobile and stationary refrigeration units pioneered by Frederick Jones in the 1930s. Working amidst snipers and the stench of rotting bodies, Seabees developed prefabricated techniques for quick construction that carried over into the post-war suburban housing boom. The islands they built much of this infrastructure on — mostly tiny specks on a map no Americans had heard of prior to 1942 — came at a high cost.

U.S. Marine Casualties on Beach of Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll, Gilbert Islands, November 1943, National Archives

On Tarawa (Gilbert Chain), for instance, 3.7k Americans died for a strip of land about three miles long. Syncing Navy bombardment and Marine landings was difficult in the best of circumstances. At Tarawa, the island’s bombing wasn’t as effective as hoped and the landing craft hung up on sandbars in low tide, leaving vulnerable Marines to wade through the chest-deep sea with their guns held high to get to the beach. After Tarawa, they checked water depth and tides beforehand, used improved precision bombing on the Japanese to soften defenses, and armed the Higgins Boats (landing craft). The photo above testifies to the sacrifice Marines made on this small island, while the photo below shows what they fought to build.

U.S. Intelligence was key throughout the Pacific War. They used Japanese-Americans to help break Japanese codes while passing their own sensitive information among Navajo Indian Code Talkers. Navajo was an unwritten and difficult language, as testified by 19th-century missionaries. For even better security, bilingual Indians developed a code within Navajo. They had to execute the code quickly, often under fire. Code Talkers also included Lakota, Meskwaki, and Comanche Indians, along with Basques. The U.S. used Cherokee and Choctaw to the same effect on the Western Front during WWI and continued using Navajo until midway through the Vietnam War, when they were replaced by computers. Hitler knew about the World War I Code Talkers so he sent a team of thirty anthropologists to the U.S. before World War II to learn Indian languages, but they found them too hard.

The U.S. broke some Japanese codes. They learned that Commander Isoroku Yamamoto, head of the Imperial Fleet, was going to be near Guadalcanal, a remote area in the Solomon Islands near New Guinea, where the U.S. had engaged the Japanese in the war’s first major campaign in August 1942. FDR ordered Yamamoto’s assassination there in April 1943. Like Osama bin Laden in 2011, the hit on Pearl Harbor’s architect (Yamamoto) boosted American morale. Unlike Osama bin Laden, in this case, the U.S. killed a man who liked America and who had initially opposed war against the U.S.

Southwest Pacific

The Japanese established a foothold on the northern coast of New Guinea and threatened to take over Australia. Americans, British, New Zealanders, and Australians fought the Japanese to a year-long muddled victory at Guadalcanal that won them a key airstrip, Henderson Field, and helped save Australia from a Japanese invasion. The Australians’ defense of the Kokoda Trail over New Guinea’s Owen Stanley Range and their stand at Port Moresby were important early victories in the Pacific War for the Allies. The first carrier battles in history occurred in surrounding waters in the Battles of the Coral Sea, Eastern Solomons, and Santa Cruz Islands. These were the first naval engagements where the main ships were often outside each others’ sight and never bothered fighting or firing on each other because their main concern was planes.

The U.S. Navy got off to a rocky start at Guadalcanal and their initial defeat left Marines stranded and surrounded on the island for months without sufficient food or ammunition. Thousands of Americans were killed or suffered from malaria and hunger before reinforcements arrived. Banzai charges led to huge casualties on both sides, especially Japan’s, while pilots in Grumman Wildcat fighters engaged Zeros in aerial dogfights. While torturous for American troops, the Japanese later called Guadalcanal, their “graveyard of the Pacific.” As they awaited supplies, Marines fought off mass, near-suicidal assaults by Japanese forces. Yet 5x more American sailors and Navy pilots died in engagements around Guadalcanal than their more famous Marine counterparts on the mainland.

Guadalcanal and the big naval engagements offshore stemmed the tide of Japanese expansion in the South Pacific in 1942. In the Battle of the Coral Sea, the U.S. Navy inflicted enough damage on Japan’s fleet to limit their capacity the next month in another battle at Midway Island northwest of Hawaii. The naval battles in the southwest Pacific under Bull Halsey were battles of attrition, with America losing or damaging many of its carriers, but victory at Midway Island in June 1942 set the stage for the U.S. to start shrinking Japan’s empire. By mid-1943, the Allies had secured the connection between America and Australia.

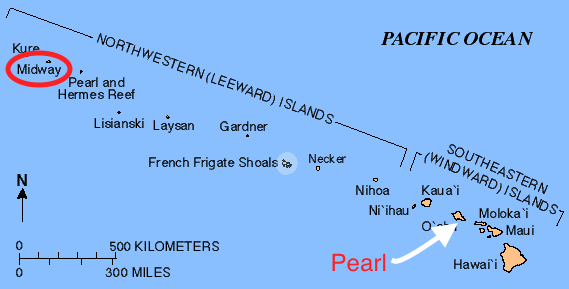

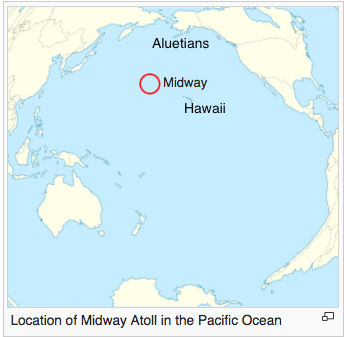

Battle of Midway

Codebreakers discovered that the Japanese mistakenly thought the aforementioned Doolittle Raids originated from Midway Island, a small airstrip northwest of Hawaii, rather than from the USS Hornet. The Japanese resolved to attack Midway, which would’ve given them a potential toehold closer to Hawaii. The Japanese tried to bomb Pearl Harbor again in 1942 but were foiled by cloud cover and their bombs fell in the ocean and mountains. At Midway, Admiral Yamamoto hoped to draw out and defeat American forces from Hawaii. The U.S. learned from Japan’s second Pearl Harbor attack that they couldn’t quite reach Oahu on a roundtrip raid from the Marshall Islands without stopping to refuel, which they’d done at French Frigate Shoals, in the outer northwestern Hawaiian atoll (see map above). The U.S. then started patrolling the Shoals, which was useful in the Midway campaign to shelter America’s carrier fleet. Japan wanted to push their line of control east across the Pacific by taking Midway and Dutch Harbor, Alaska in the Aleutian Chain. Dutch Harbor is north of Midway. Since the war’s course tended to be a progressive push west, it’s easy to forget that things could’ve continued in the other direction, endangering Hawaii, Alaska, and even the U.S. mainland. Americans feared that Hawaii would be conquered and Hawaiians swapped $200 million to the Army for Greenbacks marked HAWAII across the back that could be recognized and not honored if the Japanese seized assets. They burned the unmarked cash and the marked bills stayed in circulation after the war. Meanwhile, FDR directed engineers to build a highway connecting Canada and Alaska as quickly as possible (8 months) to help protect that territory and stage the Aleutian campaign.

Defending Midway involved outsmarting the Japanese. Intelligence isn’t just about intercepting messages; it’s about allowing oneself to be intercepted when it suits you, as George Washington and Ben Franklin excelled at in the American Revolution. The U.S. knew the Japanese were planning a major attack on a location they called “AF.” Experts couldn’t agree on where AF was, so they sent a message they knew the Japanese would intercept from Midway saying that the base there was out of water. They intercepted a Japanese message stating that AF was out of water, confirming the tiny island as the target. Though colleagues guessed the Japanese would attack the Marshall Islands next or Pearl Harbor a second time, Pacific Commander Chester Nimitz trusted this line of intelligence and set the trap. The U.S. didn’t know the exact date, but they positioned their own aircraft carriers nearby in early June 1942 and waited, outside the range of Japanese radar (275 miles).

Defending Midway involved outsmarting the Japanese. Intelligence isn’t just about intercepting messages; it’s about allowing oneself to be intercepted when it suits you, as George Washington and Ben Franklin excelled at in the American Revolution. The U.S. knew the Japanese were planning a major attack on a location they called “AF.” Experts couldn’t agree on where AF was, so they sent a message they knew the Japanese would intercept from Midway saying that the base there was out of water. They intercepted a Japanese message stating that AF was out of water, confirming the tiny island as the target. Though colleagues guessed the Japanese would attack the Marshall Islands next or Pearl Harbor a second time, Pacific Commander Chester Nimitz trusted this line of intelligence and set the trap. The U.S. didn’t know the exact date, but they positioned their own aircraft carriers nearby in early June 1942 and waited, outside the range of Japanese radar (275 miles).

In the ensuing battle, fighter pilots passed each other in the sky without even bothering to engage in dogfights. Their goal, rather, was to attack each other’s carriers; if they succeeded, their rival pilots wouldn’t have any place to land. The Japanese started off bombing Midway as planned but when one of their planes spotted the American carrier fleet, Admiral Chūichi Nagumo changed course and tried to destroy them instead. That took precious time, as the Japanese planes had to retool on deck from bombs to torpedoes. In the meantime, wave after wave of American pilots attacked Japanese carriers with no success. Of the torpedo bombers that took off from the Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown carriers, most were lost or had to ditch their planes at sea and none hit the Japanese carriers, as the torpedoes they dropped malfunctioned.

U.S. Navy Douglas SBD-3 “Dauntless” Dive Bombers Scouting Squadron From USS Hornet, Battle of Midway, 6 June 1942, U.S. Navy

The first waves’ efforts weren’t in vain, though. They used up Zeros’ valuable fuel and ammunition and forced them to lower altitudes, freeing up higher altitudes for dive bombers. Another group of Douglas SBD-3 dive bombers led by Commander Wade McCluskey couldn’t find the fleet and turned around as they ran low on fuel. He had an entire squadron following him that he didn’t want to ditch in the sea if they ran out of gas. But in a cloud break under him, McCluskey spotted the wake behind a Japanese destroyer that he figured was steaming toward the main carrier group. He was right and his gamble paid off. His squadron nose-dived and destroyed three Japanese carriers along with several smaller ships – five of the most productive minutes in U.S. military history. The carriers were still off-loading bombs and reloading torpedoes on deck, making them more combustible than if their munitions were stowed in magazines like normal. They destroyed the fourth Japanese carrier at Midway shortly after. The U.S. lost just the Yorktown CV-5, later replaced by the eponymous CV-10 (1943-1970).

The Battle of Midway was the first naval defeat of Japan’s modern history and a costly one at that. Four of Japan’s six carriers were gone, along with 40% of their top tier pilots (over 3k killed). Military historian John Keegan called Midway the “most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare.” For one, it allowed the U.S. to catch up to Japan in the size of its carrier fleet. From then on, the war proceeded progressively in America’s favor, even though they had no way of knowing that then and the vast majority of fighting was still to come. At the time, Americans were trying to fend off another Pearl Harbor-like attack. As it turns out, the Japanese were never able to execute their “Eastern Plan,” or takeover of Hawaii. They reported a victory at Midway to their citizens and imprisoned reporters who witnessed what really happened. Oscar-winning director John Ford, most famous for his work with John Wayne, was in the service and Admiral Chester Nimitz ordered that he document the battle as best he could:

Arsenal of Democracy

Arsenal of Democracy

Losing four carriers in one battle was a significant setback for Japan. The U.S., conversely, spared three carriers by chance when they left Pearl Harbor just before Japan’s attack in December 1941. America’s industrial advantage over Japan grew as the war progressed because U.S. factories were never bombed and the U.S. was a larger country to begin with. Spearheaded by the War Production Board, the U.S. was out-producing Japan at a 15:1 ratio by war’s end. Stanford historian David Kennedy wrote that, after Pearl Harbor, it was as if somebody raised the East Coast and dumped money from banks and the government out across the rest of the country. The population doubled in western states because of ship and plane manufacturing.

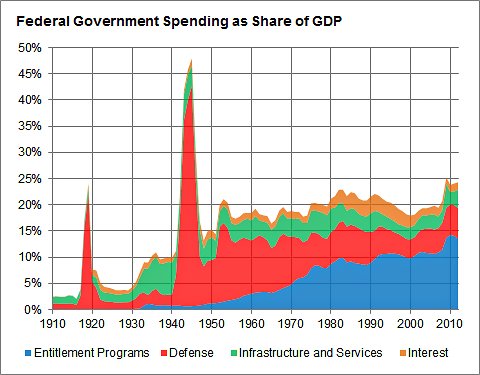

The uptick in government defense spending far surpassed any stimulus FDR tried during the New Deal. The debt ballooned and taxes skyrocketed (the top bracket to 81-94% during WWII and the early Cold War), as federal outlays increased by 1000%, from $9.1 billion in 1939 to 92.7 in 1945, the peak year. Wealthy Americans paid effective tax rates of ~ 60% during World War II. In today’s dollars, the war cost about $4.5 trillion dollars. Even higher taxes couldn’t pay the cost and the government enlisted Hollywood to spearhead a giant bond drive through its Stars Over America campaign. They raised an additional $300 billion in war bonds — a significant contribution.

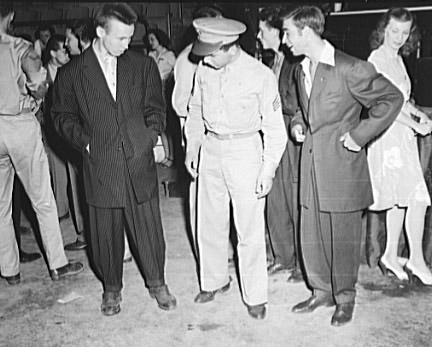

The Depression was over but that didn’t mean times were easy. Tempers flared between races and between urban and rural Americans as hoards crowded into factory boomtowns looking for work. There were housing shortages and some people even shared beds with two other tenants, each taking 8-hour turns. Racial violence broke out in Detroit, Harlem, Beaumont, and Los Angeles. Fake news spread that Jewish businessmen were profiteering from hoarded rubber rations and that Blacks joining “Eleanor Roosevelt Clubs” were stockpiling weapons for a mass race riot while Japanese-American prisoners were hoarding meat and sugar rations. Luckily, these rumors didn’t gain the traction that they might have with today’s social media, cable TV, etc.

In Los Angeles, police more or less turned the streets over to white mobs for three days during the Zoot Suit Riots, as Navy sailors wielding baseball bats beat up Hispanics, Blacks, and Filipinos. The fighting started when white sailors working at an armory walked through a Mexican-American neighborhood on the way home from downtown bars. There was back and forth for weeks leading up to the riots, with the sailors taking particular aim at a style of dress known as a “zoot suit” popular among pachuco street gangs. Their specific complaint was that they were made of wool, which was being rationed during the war. They thought that bootleg tailors and their customers were flaunting the war effort, especially since sailors’ attire was so tight and used less fabric. Young men wearing Zoot Suits were beaten and had their clothes ripped off as the LAPD watched and did nothing. A smaller riot ensued in New York where sailors took exception to jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s outfit as he walked down the sidewalk arm-in-arm with a date they saw as too pale-skinned.

In the end, WWII helped ignite the modern Civil Rights Movement by forcing Americans to re-examine their own racism when fighting Japan and Germany. No longer needing conservative Democrats’ support for the New Deal, FDR rose up on behalf of civil rights by outlawing discrimination in the munitions industry. When bus and trolley drivers in Philadelphia refused to work because the transit system integrated their workforce (for menial tasks other than driving), it interfered with workers commuting to the city’s important naval shipyards. FDR promptly ordered in federal troops to break their “sickout” (strike). Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802, that used incentives to integrate the armaments industry, was the first federal intervention on behalf of Blacks since Reconstruction in the early 1870s.

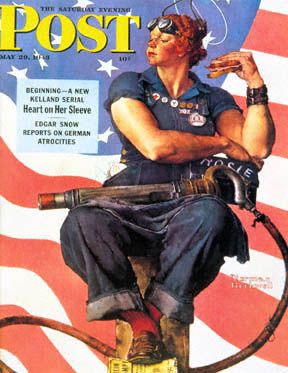

“Rosie the Riveter” Operating a Hand Drill at Vultee-Nashville, Tennessee, Working On A-31 Vengeance Dive Bomber, ca. 1943

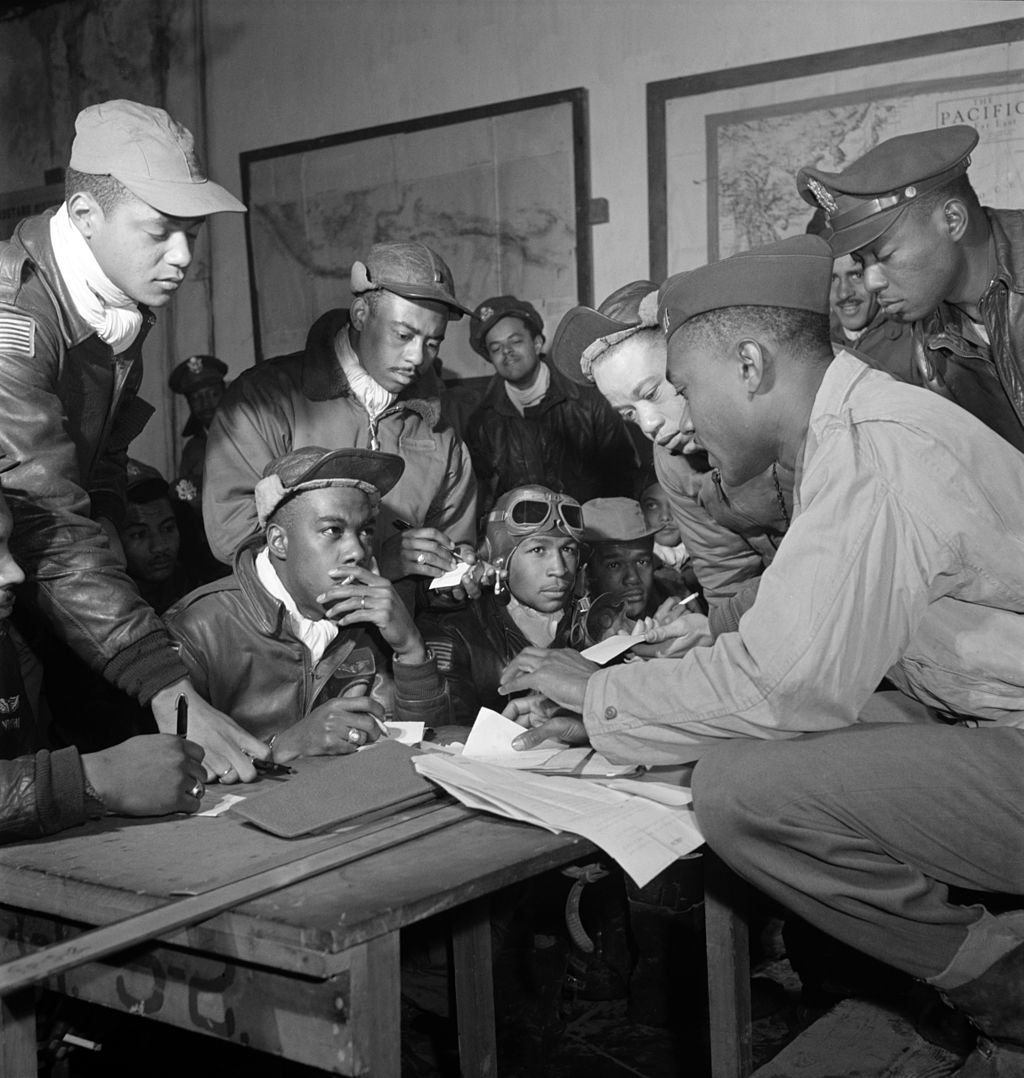

On the battlefield, Blacks fought in segregated units, doing their part to support a democracy that denied them basic citizenship. The Tuskegee Airmen, for instance, flew fighter escort and bombing missions over Europe. They were known as “Red Tails” or “Red-Tail Angels” because of the distinctive red tail fins on their Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters.

The African-American symbol for the war was the Double V: victory for democracy abroad and at home. After the war, the military was the first major institution in American society to integrate. Hispanic troops were integrated during the war because Latinos were categorized as white. The exception was Puerto Ricans from the island (as opposed to the mainland), who were considered black. The Puerto Rican 65th Infantry Regiment fought in Europe as a segregated unit.

Several Tuskegee Airmen at Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945, Photo by Toni Frissell, Library of Congress

The government not only enforced integration in the weapons industry, they basically took over sectors of the economy with the War Production Board. Learning lessons from WWI, they compelled cooperation rather than ask for volunteers and, this time, they promised to buy up any unneeded surplus at the end of war — not just weapons but also machine tools like drills, lathes, and grinders. They took over entire plants and/or built new plants that companies could keep after the war. They set aside competitive capitalism temporarily with technology-sharing licensing agreements between companies. The federal system can shift power up and down the chain-of-command, but WWII was one instance that necessitated a powerful national government. This was all hands on deck.

The government also instituted rations on items like rubber and vinyl, making tires hard to come by and temporarily ending the recording industry by breaking up many big band acts. The speed limit dropped to 35 m.p.h. to preserve rubber. Non-essential drivers got four gallons of fuel a week, while drivers helping the war effort got eight (Japanese expansion into SE Asia also lowered American oil supplies). Whiskey production dropped as distillers made industrial alcohol. The government regulated basic staples like flour and sugar. People griped and cheated here and there, but there was no widespread libertarian resistance to the denial of basic freedoms, as people understood that their sacrifices were temporary and necessary.

Japan controlled 90% of the world’s natural rubber supply, which led not only to strict rationing but also hastened the evolution of synthetic rubber, especially at B.F. Goodrich.

Car production virtually came to a halt as the military compelled contracts with Ford, GM, and Chrysler for planes/fuselages, tanks, guns, and jeeps. There were only 139 American cars built from 1942-43. FDR commissioned ex-Ford and GM production engineer William Knudsen as a lieutenant general to oversee war materials and coordinate with the War Production Board. Edsel Ford built a bomber factory before succumbing to stomach cancer at 49, when his son Hank (Henry Ford II) returned from the front to take over.

Shipyards and plants produced weapons at a staggering rate. Bechtel and Kaiser Shipyards in California (Sausalito, Richmond) and Portland, Oregon made cargo Liberty ships in just over four days (start-to-finish), completing two each per day, while the Navy employed civilians at their dry docks in Long Beach. Boeing averaged around fifteen B-17F “Flying Fortresses” per day in Seattle and as many B-29 “Superfortresses” in Renton, Washington and Wichita, Kansas. Henry Ford’s Willow Run plant in Michigan averaged just under the same rate for B-24 Liberators. In Detroit, Chrysler built more tanks than all of Germany and contributed parts to the atomic bomb that ended the Pacific War (next chapter).

Stuart Symington turned Emerson Electric in St. Louis into the world’s biggest manufacturer of aerial gun turrets and later headed the Air Force. Bath Iron Works in Maine made a destroyer every three weeks. Henry Kaiser built dry-docks to take advantage of the sub-assembly system of dividing up tasks and, on Ford’s advice, pioneered the use in shipbuilding of welding rather than riveting — ideal for a large, unskilled workforce because it requires less strength and skill and less time to get up to speed. Similar shipyards popped up in coastal towns from Pascagoula, Mississippi to Groton, Connecticut (submarines). Mobile, Alabama’s population jumped from 80k to 200k, with many workers living in tents and makeshift trailer parks. Boeing designed bombers and collaborated with other companies like Lockheed, Douglas, Bell, and Glenn Martin to build them. Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica helped Boeing build bombers and converted design of their popular DC-3 passenger airliners to durable and versatile C-47 transport planes used throughout the war (e.g., paratroopers at Normandy) and during the 1948 Berlin Airlift. North American Aviation in Los Angeles, Columbus, Kansas City, and Dallas made fighters like the Lockheed P-38 Lightning and the B-25 Mitchell bombers used in the Doolittle Raid. Later we’ll see the importance of one of their most famous fighters, the P-51 Mustang.

Chicago was a key Midwestern cog in the Arsenal of Democracy, including Albert Kahn’s highly-regarded Dodge plant that made B-29 engines and inspired similar factories in the Soviet Union. Chicago’s naval bases conducted pilot training on Lake Michigan and its production included tanks, bombs, torpedoes, minesweepers, and landing craft. Kraft transitioned from food to radar, Hammond Organ made gas cans and caskets, Chicago Roller Skate Co. made grenades, Victor Adding Machine made Norton bomb-sights, etc. You get the idea. Last, but certainly not least, atom-splitting physicists led by Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago triggered a self-sustaining nuclear reaction in a squash court under their football stadium (below) — the key breakthrough that allowed the Manhattan Project to build atomic weapons three years later, in 1945 (about which more in the next chapter).

The government was as involved in the economy as it had been during the Depression, except that this time Roosevelt was trying to curb inflation instead of deflation. With people making more money, but consumer goods scarce from rations, the concern was that prices would skyrocket, devaluing the dollar. FDR capped salaries, taxed the wealthy and corporations at high rates, set price ceilings on consumer goods, and encouraged people to stop installment buying and spend on war bonds instead. MGM even pitched in with a short propaganda film called Inflation (1943), depicting Satan colluding with Hitler to devalue the dollar.

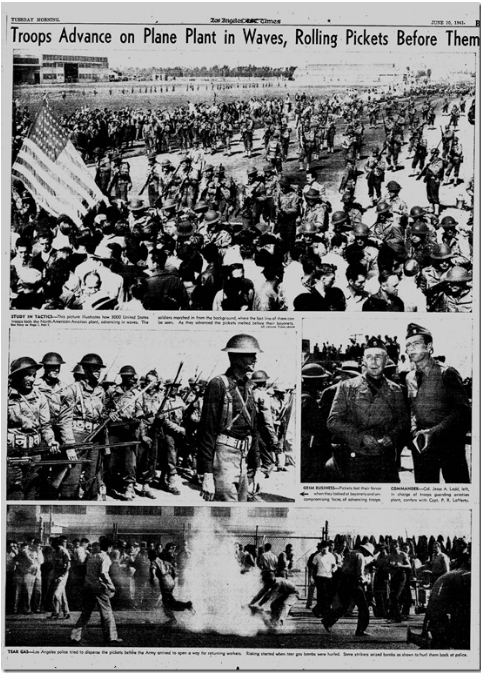

For liberal historians, World War II not only transformed the economy in a positive way; it inadvertently allowed a “snake in the grass” insofar as business leaders themselves infiltrated FDR’s economic cabinet at the expense of more worker-friendly New Dealers. When the UAW (United Auto, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Makers of America) struck at North American Aviation’s Los Angeles plant in June 1941, five months before Pearl Harbor, FDR exercised emergency powers and sent in troops to disperse picketers and briefly seize the factory until the strike ended (LA Times).

The manufacturing efficiency Ford and Knudsen pioneered in Detroit paid dividends for the Arsenal of Democracy, FDR’s famous catchphrase for wartime America, coined even before the U.S. entered the war, in 1940, especially for Detroit. FDR formed the War Production months before Pearl Harbor, anticipating what might happen. Airplane production, especially, disproved Luftwaffe Commander Hermann Göring, who said in 1942, “The Americans are good about making fancy cars and refrigerators, but that doesn’t mean they are any good at making aircraft. They are bluffing. They are excellent at bluffing.” He was very wrong. While Henry Ford’s earlier support for Hitler didn’t help the Allied cause, his production methods helped bring down Germany and Japan. “Fordism” helped the USSR, too, as they made T-34 tanks at a higher rate than Germany could keep up with, in factories outside the range of Nazi bombers. Prussian-born architect Albert Kahn, who designed auto plants for Ford and Dodge, moved to the USSR and designed 30 factories during the war. The U.S., meanwhile, sold Jeeps to its allies by the square mile (“jeep” came from GP, shorthand for general purpose). The U.S. built 40% of the weapons during the war, its allies another 30%, and the Axis Powers the remaining 30%. Simply put, the United States could make planes, ships, and tanks faster than they were being destroyed, while the Axis Powers struggled to rebuild bombed-out factories, railroads, and oil refineries. This distinguishing factor was critical to the Allied victory in WWII.

Women @ War

Women worked in transportation, agriculture, and factories, where they comprised ~ 15% of personnel. Vultee/Convair Aircraft in Downey, California was first to build fighters on an assembly line and first to use women in the production phase. The song “Rosie the Riveter,” while about one woman, came to represent this entire part of the workforce. Latinas were called Rosita Riveters. While these workers were the biggest and most memorable face of female involvement in the war, others were directly involved in the military as nurses, spies, entertainers (USO), pilots, and mathematicians. In all, around 500 American women died overseas during the war. OSS agent Julia Child, later famous as a French cook, developed a shark repellent that kept fish from exploding undersea mines intended for German U-boats.

Child joined the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, forerunner to the CIA) because she was too tall to be a WASP. WASPs (Women’s Airforce Service Pilots) trained male pilots. Army psychologists figured that having women in the cockpit soothed men’s nerves and made the challenge seem more attainable, especially with large bombers. Female pilots also ferried planes between non-combat zones. The purported soothing effect of women in the air led to more stewardesses than stewards as flight attendants on commercial flights after the war. Cornelia Fort was the first American to realize that Pearl Harbor was being attacked. On the morning of December 7, 1941, she was working in Oahu as a civilian flight instructor when she found herself surrounded by Japanese fighters — a scene depicted in the classic film Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). She survived but was killed as a WASP in a mid-air collision in 1943. In 2010, President Obama awarded the 300 surviving and previously unrecognized WASPs Medals of Honor. The Navy also had an all-female volunteer unit called WAVES (Women Accepted For Volunteer Emergency Service).

Child joined the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, forerunner to the CIA) because she was too tall to be a WASP. WASPs (Women’s Airforce Service Pilots) trained male pilots. Army psychologists figured that having women in the cockpit soothed men’s nerves and made the challenge seem more attainable, especially with large bombers. Female pilots also ferried planes between non-combat zones. The purported soothing effect of women in the air led to more stewardesses than stewards as flight attendants on commercial flights after the war. Cornelia Fort was the first American to realize that Pearl Harbor was being attacked. On the morning of December 7, 1941, she was working in Oahu as a civilian flight instructor when she found herself surrounded by Japanese fighters — a scene depicted in the classic film Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). She survived but was killed as a WASP in a mid-air collision in 1943. In 2010, President Obama awarded the 300 surviving and previously unrecognized WASPs Medals of Honor. The Navy also had an all-female volunteer unit called WAVES (Women Accepted For Volunteer Emergency Service).

Other mathematically inclined women, nicknamed “computers,” crunched tens of thousands of equations in the Los Alamos calculation wards, searching for the best ways to set off a nuclear reaction. Stanislaw Ulam invented the Monte Carlo Method of random sampling they used, soon done by real computers and applied to numerous other fields including biology, engineering, telecommunications, and business. More female computers worked at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia), figuring tedious equations to develop range tables for artillery and aerial bombing. Range tables took into account variables like wind speed, elevation, and temperature. In both cases, these human computers were performing the exhaustive workload that electronic computers would soon assume. The Philadelphia group also worked as programmers on some of those early electronic computers. Human computers also worked on early NASA programs, depicted in Hidden Figures (2016).

Even in WWII, there was tension over gender roles. Some men were threatened or put off by Rosie Riveters and WASPs and feared the war would embolden a feminist movement. Consequently, the government was tasked with a balancing act in its promotional films, often featuring the Riveters assuring anxious viewers that they looked forward to returning to the domestic sphere after the war. Some historians think the role of wartime women in manufacturing was a net loss for feminism because these disclaimer films provided an idealized image of the prototypical 1950s housewife.

Japanese Americans

Unlike WWI, German-Americans didn’t get the brunt of persecution this time. The government imprisoned some, but those camps only served as recruiting grounds for the American Bund, the biggest U.S. Nazi chapter. Germans were harder to distinguish from the rest of the population than Japanese anyway. There were even more German-Americans than Anglo-Americans. In central Texas, the weekly German-language newspaper Das Wochenblatt condemned Nazism and the KKK (this was a rare German paper the government didn’t shut down during WWI). The U.S. also used Jewish German- and Austrian-Americans called the Ritchie Boys, some first-generation immigrants, in the Military Intelligence Service, a special unit outside the Army’s OSS.

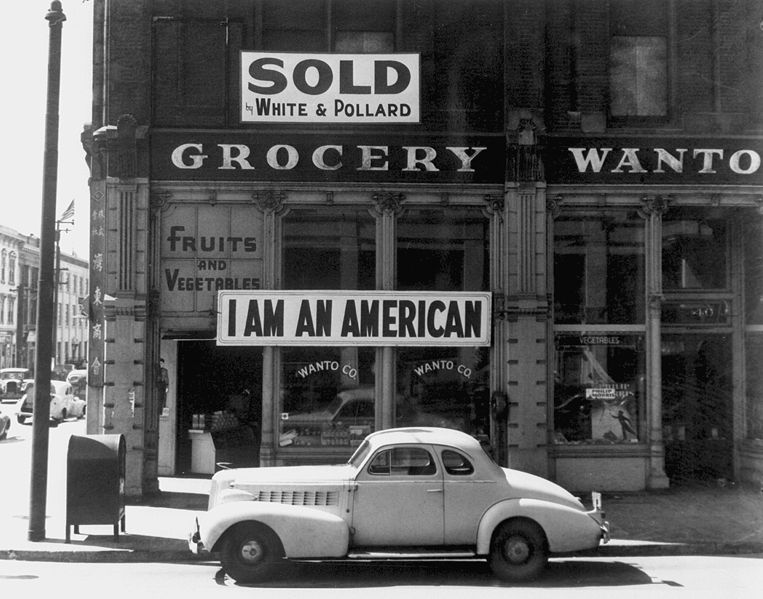

Japanese Americans, regardless of how long they’d been in the country (some were WWI veterans), were given a short amount of time to sell their homes and businesses and concentrated in twelve internment camps across the West. The average time to sell and move into assembly stations (usually horse stables) was two weeks, but sometimes as short as 48 hours. Some weren’t prisoners, strictly speaking, insofar as they could leave; but they couldn’t work or own property elsewhere and children had to attend camp schools. So, really, Japanese-Americans had no choice but to stay and to submit to forced labor, often constructing their own prisons. Others weren’t allowed to leave and were shot if they tried. Future Star Trek actor George Takei (Sulu) remembered reciting the Pledge of Allegiance lines “with liberty and justice for all” while staring at the window at barbed wire. Like most families, Takei’s lost their home and business (a dry cleaners) permanently. Despite his earlier flirtations with Hitler, William Randolph Hearst supported the war once it started and focused his many newspapers on demonizing Asian Americans.

The internment camp order came directly from the top, as FDR’s Executive Order 9066 (FDR issued the most executive orders, or actions that circumvent Congress, of any president). Small businesses competing with Japanese Americans also lobbied for EO 9066 and white California farmers happily scooped up the discounted land. Though the FBI testified before Congress that Japanese Americans posed no security threat, FDR’s racial profiling order dovetailed with widespread American sentiment toward Asians dating to the 19th century. And, as was the case in his reluctance to welcome Holocaust refugees, FDR’s policy toward Asian Americans was complicated by his own racial prejudice (JJ).

Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy wrote that “These people are not ‘internees.’ They are under no suspicion for the most part and were moved largely because we felt we could not control our own white citizens in California.” But Army Western Defense Commander John L. Dewitt told Congress, “We must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map.” Luckily it didn’t come to that, but Dewitt’s remarks indicate this situation could have degenerated considerably, especially if the Japanese had been successful in the Pacific War. In that scenario (per McCloy’s comment) one warped, hypothetical upside of the internment camps is that they could’ve provided protection; unless those running the camps agreed with Dewitt, in which case they would’ve become more similar to German concentration camps.

Despite the internment, many Japanese Americans fought in the war, including some who’d been in the camps themselves. They served in the forenamed Military Intelligence Service in the Pacific or in combat in Europe. Using Japanese Americans in combat in the Pacific would’ve created complications, including potential confusion like that seen with Hawaiians in the chaos of December 7th, 1941. During the Italian campaign, the Japanese-American 442nd Infantry Regiment became the most decorated unit in American history. It was partly because a racist commander threw them into the line of fire so often, seeing them as expendable, but also speaks to their valor and patriotism.

Another Japanese-American, Fred Korematsu, sued the U.S. Government for violating his civil rights. He lost his case, but it was an important one nonetheless because the Supreme Court ruled that only the wartime emergency justified racial discrimination. That opened the door for post-war litigation from groups like the NAACP as we’ll see in coming chapters. President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the National Medal of Honor in 1998. Interning the entire Japanese-American population, including people with American roots, especially with the FBI reporting there was no danger, was an overreaction the government formally apologized for years later. Ronald Reagan signed a reparations bill for former captives in 1988.

In hindsight, there never was a significant Japanese threat within the 48 states that then comprised the U.S., but that wasn’t clear at the time. Hindsight is 20/20, as the saying goes. Japanese subs sank several merchant ships off the West Coast, sparred with the Navy, and were spotted off the San Francisco coast. Two weeks after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese sank the Union Oil tanker SS Montebello off the California coast near Port San Luis. They fired on historic Fort Stevens at the Columbia River’s mouth and a lighthouse on Vancouver Island. The Japanese weren’t inflicting much damage, but they were lurking off the coast, making their presence known. As for espionage, Japan did have some in the Lower 48, but they cleverly used Caucasians (NPS), of whom 18 were tried and ten convicted. Yoshio Muto spied out of Japan’s San Francisco consulate for a few weeks after Pearl Harbor before being called home, and Intercepted messages show that they hoped to recruit Japanese-American spies but they couldn’t find anyone willing.

The Battle of Los Angeles

In February 1942, a Japanese sub fired on an oil field north of Santa Barbara and a tanker near Los Angeles. The night after the Santa Barbara attack, February 24-25th — three months after Pearl Harbor — anti-aircraft artillery at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro unleashed a middle-of-the-night barrage at a mystery aircraft over the city in the Great L.A. Air Raid. There was confusion over whether the target was a Japanese craft testing L.A.’s air defense, which was formidable, or an American false flag to rationalize the internment of 20k Japanese from the city’s Little Tokyo district, while others later speculated that it was a UFO based on a retouched newspaper photo. Most likely, though, it was an understandable but frantic reaction to our own weather balloon, used to gauge the wind to help fighter pilots in case they had to defend the city.

George Marshall (Army) reported to President Roosevelt that it was dozens of Japanese planes though, mysteriously, none dropped bombs or were shot down. Frank Knox (Navy) said it was a false alarm caused by over-active imaginations and skittish nerves. Context is the key to understanding this story. In the over 89k days of American history, it’s hard to imagine a night more primed for jittery nerves and quick triggers than the early morning hours of February 25th, 1942. The Japanese had just attacked Santa Barbara and Angelinos wondered if they were targeted as the next Pearl Harbor. The Army was on Green Alert all night with mounted .50 caliber machine guns pointed skyward and anxious radar operators interpreting weather anomalies, birds, etc. (radar was crude then by today’s standards). The 37th Coast Artillery Brigade would not be caught napping like the forces at Pearl Harbor.

Literally speaking, the Army’s target was “unidentified,” for sure, if not from outer space. Imagine the odds of aliens crossing vast galaxies to visit Los Angeles the night after Japanese subs fired on the same area. On the other hand, if the object in the photo above was a weather balloon, it’s surprising it wasn’t shot down. But maybe there is no object. The L.A. Times enhanced the negative (which is missing) and it’s not clear whether it shows an object or just a confluence of lights surrounded by explosions from 12.8 lb. anti-aircraft shells. At least five people died from heart attacks or auto accidents directly brought on by the stress and several structures burned. Whatever it was or wasn’t, the “Battle of Los Angeles” was the deadliest night of WWII in the continental United States.

The Japanese also managed to start a few small forest fires in the Northwest, but the only Americans killed in the Lower 48 (other than incidentally in the L.A. Air Raid) were an unfortunate family from Coos Bay, Oregon who chanced upon a high-altitude fire balloon Fu-Go, of the sort that started the forest fires. Japanese internment commenced about a week after the submarine attacks in Southern California.

Battle of the Atlantic: Gulf of Mexico, East Coast & South America

At the time, Germany presented a more immediate threat to the U.S. than Japan, with their U-boats in close proximity to the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico. Unlike the Pacific, the Atlantic naval battle came right up to mainland American shores. Early in the war, the U.S. struggled to get supplies across the Atlantic to Britain. Britain not only had to survive but also serve as a base for a potential Allied invasion of Germany. The European war’s fate hinged on the Battle of the Atlantic. From England, Allied planes could run round-trip bombing missions and, eventually, land forces could cross over from there to the coast of northern France.

The Germans went straight to the source in Operation Drumbeat, aka “the Happy Time” or “American shooting season,” under Admiral Karl Dönitz. Unbeknownst to most students of history, the U.S. lost more shipping close to its mainland than at Pearl Harbor. In May 1942 alone, Germany sank over 40 ships in the Gulf of Mexico, from which most of the world’s oil then flowed (one historian called it the era’s Arabian Gulf). The Yucatan Channel (left), the narrow strait between Mexico and Cuba, was especially vulnerable because all Gulf traffic passed through there.

The Germans went straight to the source in Operation Drumbeat, aka “the Happy Time” or “American shooting season,” under Admiral Karl Dönitz. Unbeknownst to most students of history, the U.S. lost more shipping close to its mainland than at Pearl Harbor. In May 1942 alone, Germany sank over 40 ships in the Gulf of Mexico, from which most of the world’s oil then flowed (one historian called it the era’s Arabian Gulf). The Yucatan Channel (left), the narrow strait between Mexico and Cuba, was especially vulnerable because all Gulf traffic passed through there.

Germans also brazenly patrolled the East Coast, especially when cities and FDR’s administration refused to order a blackout because they didn’t want to interrupt commerce. Consequently, U-boat periscopes could see the outlines of otherwise darkened merchant and Navy vessels as they crossed in front of lit skylines. The SS Gulfamerica sank off the coast near Jacksonville, Florida for that reason in 1942.

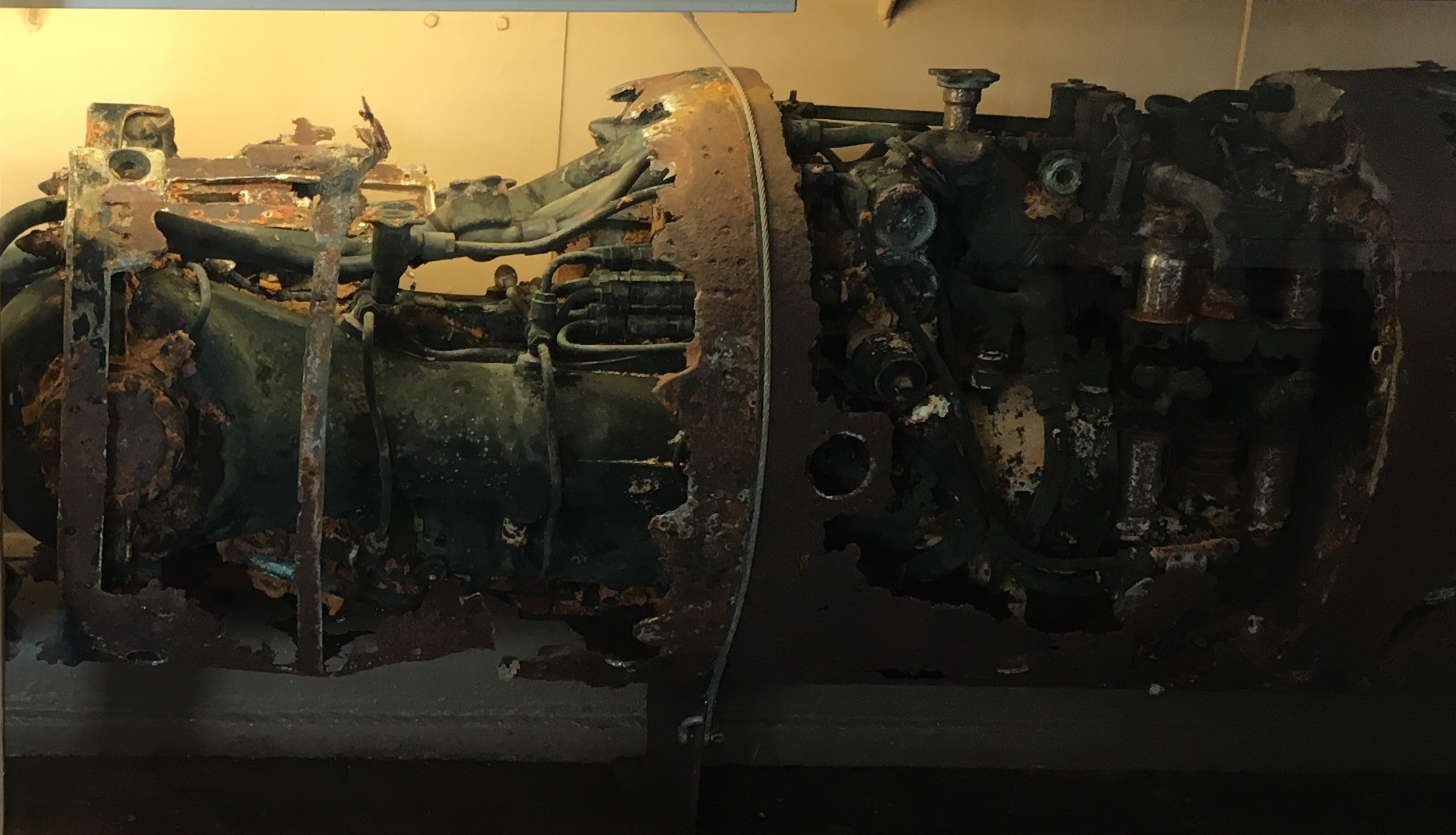

In the open ocean, swarms of U-boat “Wolfpacks” decimated shipping through 1942, with the Kriegsmarine winning at ~ 35:1 ratio. Torpedo explosions under ships caused the water to “sink” suddenly underneath, breaking their hulls in half. In the first year America entered the war, Navy and merchant ships went down at a steady rate as Germany now had the green light to attack them at will. That’s a major reason Hitler declared war on the U.S. just after Pearl Harbor, hoping to starve out Britain. The best defense was depth charges that could destroy a sub with hydraulic shock if dropped close enough or even trigger a secondary explosion within the sub, as happened once off the Louisiana coast in 1942. The German U-166 sank the steam passenger ship Robert E. Lee as it ferried construction workers from Trinidad to New Orleans, but an American PC-461-class submarine chaser destroyed the U-boat with a depth charge (both wrecks remain on the Gulf’s bottom). However, with 906 Allied ships lost in U.S. waters early in the war, only 12 U-boats were sunk, a worse ratio even than the mid-Atlantic.

But U-boats had another weakness: their internal combustion engines ran in conjunction with batteries that had to be recharged periodically at the surface, making them vulnerable to air attack when surfacing. U-boats spent over 85% of their time near the surface. Unfortunately, the middle of the Atlantic was outside the range of Allied planes that could seize on this weakness, making this region most vulnerable to Wolfpacks. Over 3k American merchant ships sank in 1942-43, ~1% of the 300k that supplied Britain. Improvements in on-board radar and sonar were the key to closing this “Atlantic Gap” as the “hunter became the prey.”

Airborne radar also improved for attacking submarines closer to shore, with Allied engineers developing small, microwave-based magnetrons that could fit in the nose of planes and detect objects as small as submarine periscopes on or near the ocean surface. The U.S. trained pilots, mechanics, and navigators in the new radar at a secluded base in the Everglades near the coast at Boca Raton, Florida (above), detecting old sunken ships for practice. Admiral Dönitz didn’t understand why U-boats were suddenly and increasingly on the receiving end of torpedoes and depth charges. German U-boat crews then had a 75% chance of dying, the worst odds of all the German armed services. Of the technology Britain shared with America during the war (including computer and atomic technology), the cavity magnetron radar was the first to pay dividends, turning the Atlantic battle in the Allies’ favor.

A final factor that favored the Allies against U-boats was getting the upper-hand in cryptography. Nazis in South America were alerting the Kriegsmarine to Allied shipping routes. Cryptanalyst Elizabeth Friedman Smith (right), on whose head the Mafia had placed a bounty during Prohibition because she decoded their cipher for the FBI, was able to break their codes twice. The first time, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover alerted Brazilian authorities too early, so Germany knew their code was broken and they came up with a second, better-encrypted cipher. She broke that as well, though by that point even the cleverest humans were reaching their capacity and on the verge of being replaced by computers, as we’ll see in the next chapter. Smith’s work also broke the back of fascist governments in Argentina and Bolivia, helping to keep Nazism from gaining a firmer foothold in South America, which would’ve complicated matters for the Allies. Her role was classified for the rest of her life and J. Edgar Hoover stamped FBI on all her work to steal credit. The Army’s Cipher Bureau where she worked seeded the NSA (National Security Administration), that began in 1952.

A final factor that favored the Allies against U-boats was getting the upper-hand in cryptography. Nazis in South America were alerting the Kriegsmarine to Allied shipping routes. Cryptanalyst Elizabeth Friedman Smith (right), on whose head the Mafia had placed a bounty during Prohibition because she decoded their cipher for the FBI, was able to break their codes twice. The first time, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover alerted Brazilian authorities too early, so Germany knew their code was broken and they came up with a second, better-encrypted cipher. She broke that as well, though by that point even the cleverest humans were reaching their capacity and on the verge of being replaced by computers, as we’ll see in the next chapter. Smith’s work also broke the back of fascist governments in Argentina and Bolivia, helping to keep Nazism from gaining a firmer foothold in South America, which would’ve complicated matters for the Allies. Her role was classified for the rest of her life and J. Edgar Hoover stamped FBI on all her work to steal credit. The Army’s Cipher Bureau where she worked seeded the NSA (National Security Administration), that began in 1952.

Welders Use the Stovepipe Method on the Big Inch Pipeline That Was Really 24″ (610 MM), Photo by John Vachon, Library of Congress

Even when they were winning the Battle of the Atlantic, Germany wasn’t able to touch American oil fields in Texas, Oklahoma, or California regardless of whether they bombed tankers in the Gulf. To support the Arsenal of Democracy, Petroleum Administration for War engineers and oil companies built a pipeline (“Little Big Inch”) from East Texas to Chicago for kerosene, gasoline, heating oil, and diesel, and another (“Big Inch“) to carry crude oil from East Texas to shipyards in New York and Philadelphia.

After the Allies got the upper hand in the Atlantic, Germany’s American Theater consisted mainly of failed saboteurs and spy rings. Some German operatives came ashore from U-boats — one group in Long Island and the other in Ponte Vedra Beach (south of Jacksonville, FL) — but authorities apprehended them before they could accomplish their task of destroying railroads, mines, canals, power plants, and aluminum factories. The Long Island group planned to pour sand into giant DC converters nine stories under New York’s Grand Central Station that powered the Northeast’s diesel-electric trains; the sand would’ve melted into glass and seized the motors. Their ringleader, George John Dasch, evidently lost faith in the Nazi cause (or the mission), defected, and turned in his accomplices. He was convicted of treason, but not executed.

Adolf Hitler obsessed over bombing New York City, the setting of his favorite movie King Kong (1933), but the Messerschmitt factory was never able to develop a long-enough range bomber for round-trip missions to the East Coast. Japan developed a hybrid submarine/aircraft carrier, the I-400-class SuperSub, to bomb the West Coast and Panama Canal, but it wasn’t finished until war’s end. The U.S. destroyed it off the coast of Hawaii in 1946 to avoid sharing the technology with the Soviets per a wartime agreement.

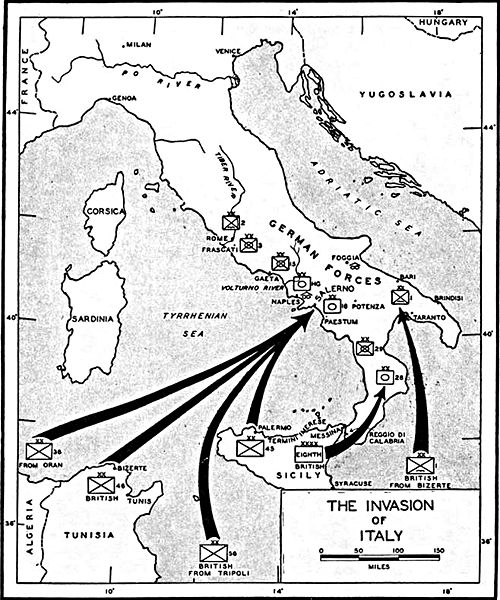

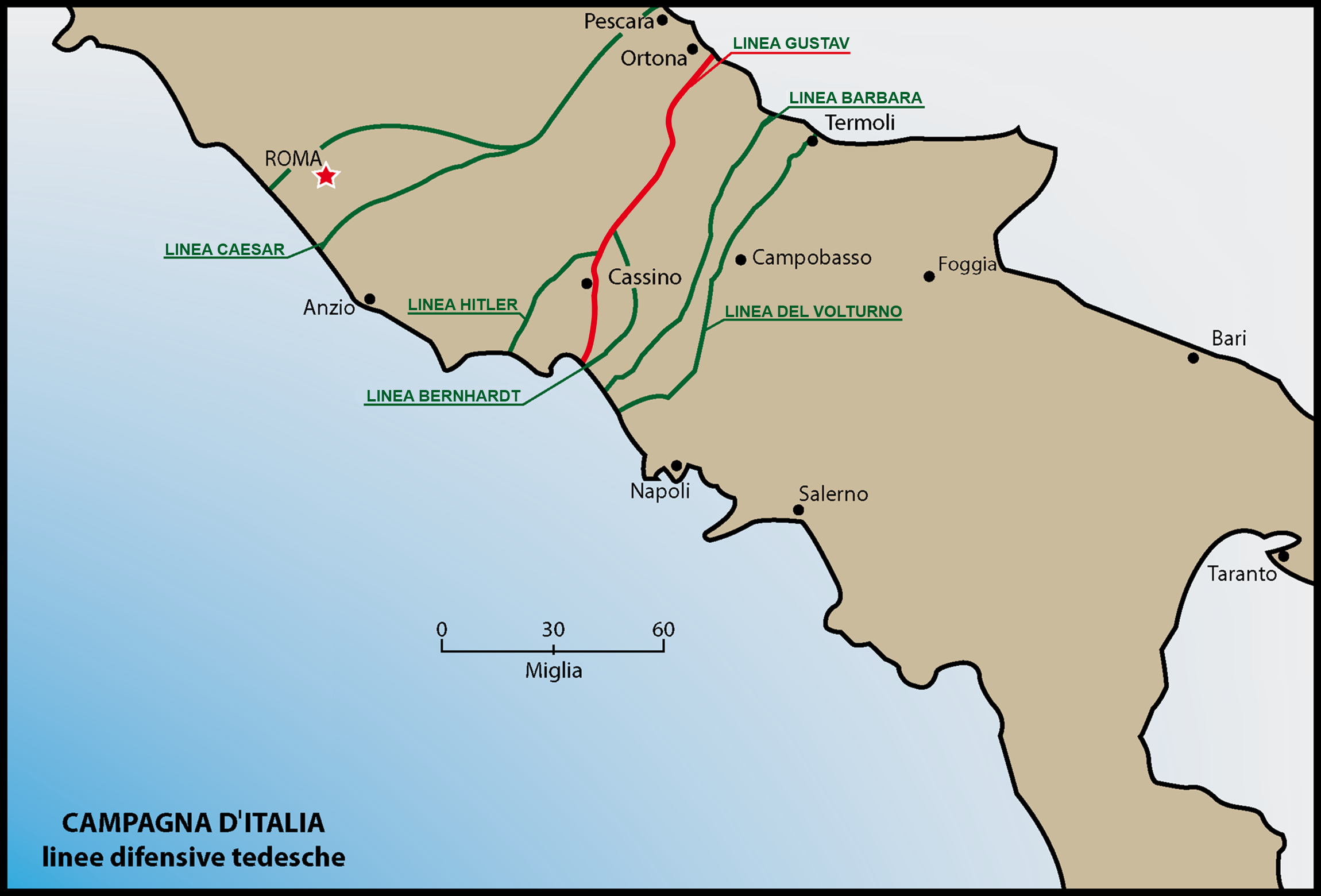

North Africa & Italy

In Europe, as in Asia, the Allies executed a peripheral strategy, pushing Nazis and Italians out of North Africa and working their way up the Italian “boot” (boot-shaped peninsula). Take a moment to study the map above to orient yourself geographically. North Africa is in the bottom left-hand corner. We’ll use the term Allies to describe the U.S. side of the war, but President Roosevelt often used the term United Nations at the time to describe the nations pledged to fight “Hitlerism” in Europe. After World War I, the British had no appetite for another stalemated western front in France, and neither the U.S. nor Britain was ready early on for a direct land invasion of heavily guarded Germany, though the U.S. was more game than Britain. The North African Campaign (Operation TORCH) against German, Italian, and pro-Nazi “Vichy” French forces was controversial from the start, as some Pentagon advisors thought the indirect approach was a waste of time (Pentagon is a common metonym for the DoD, but the actual Pentagon, the pentagon-shaped building housing the Department of Defense, opened right at this time in January 1943).

Despite rigorous basic training in the California’s Mojave Desert beforehand, green U.S. troops lost early battles in North Africa to the Afrika Korps, including Kasserine Pass in Tunisia in early 1943, inadvertently strengthening the case of those who suggested not invading Germany too early. The gigantic amphibious landing on the coast, conducted after a perilous trip across the Atlantic, didn’t go well but provided the U.S. with lessons they applied the next year at Normandy when they attacked German-held territory in France. They knew then, for instance, that it was best to have the front door of the landing craft open rather than make the troops climb over the walls, and to not let the ocean fry the electronics in the tanks as they offloaded them. American GI’s were mostly brave citizen soldiers, not professional mercenaries or hardened peasants. Even their leader, Dwight Eisenhower, hadn’t actually seen combat in WWI. After initially encountering half-hearted Vichy French on the coast, Americans encountered seasoned troops who feared their officers more than the enemy. German officers killed anyone who didn’t fight hard, as did America’s Soviet allies. Officers executed over 15k German soldiers and 20k Soviets for cowardice during WWII; the U.S. shot 1 and Britain 0. American generals Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton and their troops learned from the setback at Kasserine Pass and slowly turned the momentum in the desert.

The time in North Africa wasn’t wasted because Germany was squandering men, money, and energy in their ill-advised Soviet Union invasion (Operation Barbarossa) while the Allies delayed their western invasion. Invading France sooner would’ve drawn off German troops from the USSR. Also, the Western Allies helped end Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy. Meanwhile, the Allies let the Soviets absorb the brunt of Nazi punishment for as long as possible. Only charity would’ve compelled them to do otherwise. Animated Map Ninety percent of German troops were in Russia. Even after the Western Allies invaded France, 4.5x more Russians died on the Eastern Front than did Americans and Brits in the eleven months between the Normandy Invasion and Germany’s defeat. But North Africa was more than just a diversionary tactic. Fighting there seasoned American troops that needed experience and also weakened Italy, whose 10th Army the British destroyed in 1940.

In northwest Africa, American troops defeated the Germans and encouraged people of cities like Casablanca, Morocco to side with the Allies. In the Desert War the previous year in north-central and northeast Africa, the British prevented Germany from seizing the Suez Canal, which would have given them access to Persian Gulf oil and potential control of India. With the help of Free French, the British also defeated Vichy French and Nazis in Syria and Lebanon to prevent northern access to Suez. Oil is the lifeblood of modern war machines and was one of Hitler’s motives for invading both Africa and the USSR. The British also captured German officers for the first time in North Africa. They treated the high-ranking POWs well but bugged their conversations and learned about the German war effort, including widespread discontent with Hitler and the V-2 Rocket’s development. Jewish refugees translated conversations from German to English. The generals’ accounts of atrocities in Eastern Europe later provided incriminating evidence in the post-war Nuremberg war crime trials.

Britain defeated Italian forces in Libya first and Hitler sent in German reinforcements to regain territory and win access to the Suez Canal and oil fields beyond. Britain’s victory over German Erwin “the Desert Fox” Rommel at the 2nd Battle of El Alamein, east of Alexandria and Cairo in October 1942, was a turning point in the European war. It was the first major Nazi defeat (other than the Battle of Britain), just as Midway was the first major setback for the Japanese. Like Americans at Midway, Brits employed deception in Egypt against Germans and Italians. Just as they tricked the Luftwaffe into bombing already ravaged parts of East London, they set up an elaborate fake Cairo to trick nighttime German pilots into bombing sand and lightbulbs. Bernard Montgomery (aka “Monty”), who later worked with Eisenhower in the French invasion of 1944, led British and Australian forces. British Prime Minister Churchill said of the victory at El Alamein, “It is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Later, Churchill said more simply that “before El Alamein, we never had a victory. After El-Alamein, we never had a defeat.”

The Americans, British, Dutch, Canadians, Australians, and Free French vanquished Germany and Italy from Africa. They chased the Axis Powers to the island of Sicily, west of mainland Italy, then painstakingly up the mountainous and heavily mined Italian boot after “mini-Normandy” landings at Salerno and Anzio. Before landing in Sicily, the British tricked the Nazis into thinking they were heading for Sardinia and Greece instead by having a corpse wash up on the Spanish shore with false invasion plans (Operation Mincemeat). Dwight Eisenhower gave George “Blood & Guts” Patton command of the U.S. 7th Army before their invasion of Sicily. Meanwhile, as part of Operation Husky, the Justice Department reduced sentences for New York Mafiosi like Lucky Luciano who, in turn, helped police American ports and shared their knowledge of Sicily and used their connections there to swing the population against Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and his Blackshirt paramilitaries.

On the Italian mainland, Americans landing in Salerno linked with British troops who’d landed further south. In retrospect, the Allies would’ve been better off landing above Rome had their only goal been to work their way toward Germany, but that wasn’t their real goal anyway and would’ve involved a nearly impossible route through the Alps. The Italian campaign’s primary goals were to defeat fascist Italy and to satisfy the Soviets that the Western Allies had opened a second front at a time when they weren’t fully prepared to attack Nazi forces in France and Germany.

The campaign hastened the end of fascist rule in Italy under Mussolini and occupied some German forces in the meantime. The Italian people rose up and overthrew Mussolini in July 1943, nearly two years before the war ended, and the new government capitulated to Eisenhower and the Allies. But then fearing a German reprisal, the politicians fled the country, leaving behind the Italian army, whom the Germans quickly crushed and disarmed. That left Italian citizens in the lurch and German Luftwaffe, SS/Gestapo, and Afrika Corps to control them and defend Rome from the Americans.

Pope Pius XII initially embraced Mussolini when the dictator granted the Vatican City State sovereignty as a country in 1929. Catholics also negotiated an uneasy accord with the occupying Nazis, as the Allies were hesitant to bomb the Eternal City, the cradle of Western civilization. The Nazis collected money the Vatican needed from German parishioners, first voluntarily and then by force. Moreover, the Pope feared Germany’s enemy, the USSR, more than Germany, because he feared atheism more than anti-Semitism. Nazis and Catholics had already sealed their truce in the 1933 Concordat, or Reichskonkordat, signed by Nuncio Eugenio Pacelli, who became Pope Pius. In 1937, Pius condemned Hitler and the Nazis’ version of Christianity that denied Jesus was Jewish. But Pius was neutral on the German occupation of Italy and didn’t come to the public defense of Rome’s 8k Jews, some of whom were hiding out in the Vatican’s walls. Today, the Vatican’s position is that their neutrality was intended to deflect attention from the fact that they were secretly providing sanctuary and helping Jews escape (by their estimation up to 85k, based on the number of baptismal certificates written out to Jews proving they’d been converted to Catholicism). That didn’t last, though. Reluctantly, the Pope wrote to his diplomatic intermediaries that “the Holy See was not wanting to be faced with the need to voice its disapproval” of Nazis arresting Italian Jews. The Gestapo collected gold tribute in the form of jewelry and tooth fillings and then deported some prisoners to Auschwitz while executing others. For more on this story, see the optional article below, as the Church declassified documents in 2020.

Pius condemned Nazism in the harshest terms after Hitler fell from power. One of history’s big “what if?” or counterfactual questions is: what would have happened if Pius had put his full moral authority behind resisting the Nazis? Many Nazis working concentration camps in Germany and Poland were Catholic and might have listened to the Pope. Perhaps the Church’s resistance would’ve been futile and counterproductive, as they supposed. For some historians, though, the Vicar of Christ (the Pope, Bishop of Rome) wielded tremendous influence on European Catholics, including Germans, and missed an opportunity to compromise the Nazi’s popularity, forcing Hitler to scale back on the Final Solution. Until 1965, Catholic doctrine taught that Jews were cursed because they’d killed Christ (deicide), causing Britain’s leading historian of Christianity, Diarmaid MacCulloch, to partially implicate Christianity in the Holocaust.

Germany

While the Allies hadn’t yet invaded German-held France or Germany, they had an advantage in Europe they lacked in Asia insofar as they could fly round-trip bombing missions over Germany in B-17 Flying Fortresses. That was one reason it was critical to keep Germany from overtaking Britain since American, British, and Free French planes took off from England. The bombing raids were dangerous, with casualty rates hovering over 70% for a term of a couple months (30 missions). Daytime missions were subject to anti-aircraft fire and Luftwaffe attacks while nighttime raids were less effective because they couldn’t see blacked-out targets. The first time America’s 8th Air Force tried a major day raid in August 1943 — aimed at the Regensburg Messerschmitt factory and Schweinfurt ball-bearing plant — they lost most of their group: 60 bombers with crews of ~ 10 each. The Regensburg-Schweinfurt Mission convinced the Allies that the B-17’s weren’t up to the task by themselves because they didn’t have enough guns. By 1944, long-range P-51 Mustangs escorted the bombers, giving them a better chance. The Mustangs’ design was an American variation on the British Spitfires made famous during the 1940 Battle of Britain. American, British, Russian, Mexican, and Brazilian pilots also flew P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers for short- and mid-range escorts in Europe and Asia. While more cumbersome than Spitfires and Mustangs (likened by pilots to driving a fine sports car), the sturdy and versatile Thunderbolt fighters could carry 2500 pounds of bombs — more than half that of a B-17 Flying Fortress.

The British used Spitfires for aerial reconnaissance over Germany, taking millions of photos that Royal Air Force (RAF) photo interpreters (PI’s) at Medmenham converted to 3D using stereoscopy. The graphics allowed the Allies to assess bombing raids, ferret out fake decoy targets and, in conjunction with bugging POW officers, learn about the German rocket facility on the Baltic island of Peenemünde. Amidst heavy flak, American pilot John Blyth photographed large bunkers and rocket launching pads, or “heavy sites,” in northern France, near the English Channel. They connected the Peenemünde photos with the French sites to determine that Nazis were preparing to launch missiles at England. Winston Churchill was skeptical at first because he thought missiles seemed too futuristic to be true. However, the PI’s convinced him to authorize Allied raids on the sites with Operation Crossbow that crippled and slowed the German flying bomb/rocket program. The RAF also used 3D images to gauge the amount of water backing up behind important hydro dams so that they could maximize “bouncing bomb” damage and flood German industry and farms in the Ruhr Valley during Operation Chastise.

Earlier in the war, also based on reconnaissance photos, British commandos captured a German Würzburg radar in a daring airborne raid into the French coastal town of Bruneval (see Operation Biting). Technicians reverse-engineered the modular radar after they returned it across the Channel, giving them clues how to improve harder-to-repair British radar and also gaining insight into jamming German systems. This allowed undetected Allied bombers to level the key port of Hamburg, Germany with incendiary bombs in 1943. In Operation Gomorrah, the RAF and USAAF killed 35k civilians who either suffocated to death in shelters or were swept up into the vortex of a fire tornado. To avoid raids like Bruneval in the future, Nazis surrounded their radar installations with barbed wire, making them easier to spot and target from the air.

Downed Allied pilots who escaped capture tried to make their way back to Britain via a network of cooperative resistors and enablers similar to the Underground Railroad in 19th-century America. The Comet Line wound its way from Brussels, where pilots were given false identities and new clothes, through occupied France to the Pyrenees Mountains, then from San Sebastian, Spain to Gibraltar and back to Britain.

Bombing missions that encountered too much fog or clouds dropped their payloads over an agreed-upon jettison zone over the Channel, because you can’t land planes carrying bombs. According to one theory, a transport plane including jazz trombonist and bandleader Glenn Miller flew too low over a drop from an Avro Lancaster bomber squadron, killing Miller by friendly fire in December 1944. Another theory is that Miller’s single-engine Noorduyn Norseman (with a defective carburetor) just went down in cloudy, icy weather — the same storm that gave Hitler cover for the Battle of the Bulge (next chapter).