by Hamilton Stewart, Journalism, Distance Learning

The brain signals the body that it needs sustenance, and the state of hunger focuses the entire system on finding food in that environment. Human intelligence itself evolved because hunger made early hominids more effective hunters and gatherers. The old adage goes, empty stomachs are often wiser than empty heads. Hunger is wise.

Hunger is a noun, defined as “a feeling of discomfort or weakness, coupled with the desire to eat (“Hunger,” 2024). It is a sensation caused by insufficient consumption of dietary energy. It is a basic need that must be addressed. The body must consume nutrients to grow and sustain life. Hunger is suffering.

Hunger is also a verb, defined as “having a strong desire or craving for” (“Hunger,” 2024). There is no hunger pang. There is no feeling of discomfort or weakness. There is no physiological need. It is a feeling, but it is one of yearning and longing for something. More than an involuntary stimulation to nourish the body, there is an existential need to nourish the mind and soul. Hunger is a struggle.

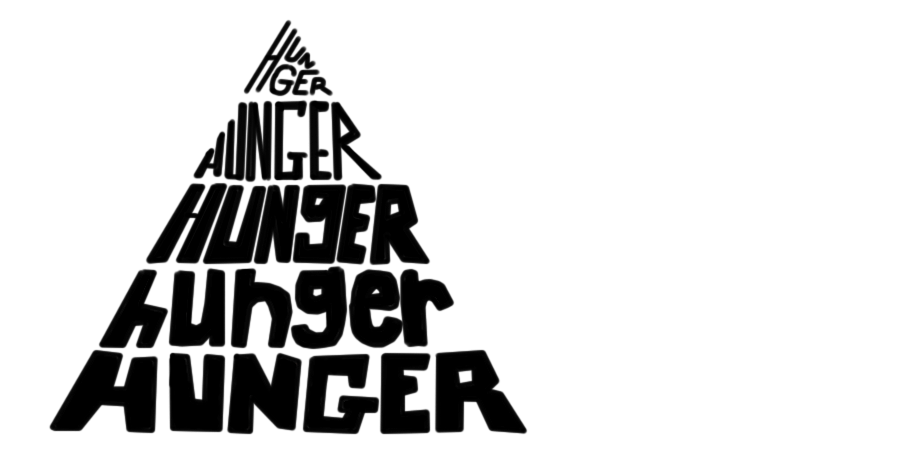

Abraham Maslow first introduced the concept of a hierarchy of needs in a 1943 paper, titled “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Presented as a pyramid, there are five different levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, starting at the lowest level known as physiological needs. Basic requirements are shelter, clothing, temperature regulation, sex, air, and nutrition (Maslow, 1943). Hunger is human.

Malnourishment, famine, and food insecurity are types of hunger that belong on the basic level of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Much like an individual, a society cannot move on to the other levels of more advanced needs until the basic needs are met. Food insecurity has reached unprecedented levels globally. In recent years, the lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, recurrent droughts, and severe weather events like flooding have driven the increase in global hunger. These factors often compound and contribute to the worsening of food insecurity worldwide (Omer, 2024). Hunger is thriving.

Progressing through Maslow’s pyramid, the second level, known as security and safety needs, refers to financial security, health, wellness, and protection from accidents or injuries. Finding a job, living in a safe neighborhood, contributing to a savings account, and obtaining health insurance are all examples of actions motivated by security and safety needs. The safety and physiological levels combined make up what are considered basic needs. These basic needs are vital to survival and Maslow believed that these needs are similar to instincts and play a major role in motivating behavior. The hierarchy theorizes that people are motivated to fulfill basic needs before moving on to other, more advanced needs. Hunger is a catalyst.

Social, esteem, and self-actualization needs make up the remaining levels of the pyramid consisting of advanced needs. Socially, we need love, acceptance, and belonging. For our self-esteem we need appreciation and respect. Self-actualizing people are concerned with personal growth and achieving their potential. Hunger is transcendent.

Perhaps conflict theory best explains food insecurity (Coser, 1956). Conflict is the main driver of hunger in most of the world’s food crises. Conflict breeds hunger. Conflicts in Syria, Gaza, and Ukraine can disrupt markets, driving up prices, and damaging livelihoods. It can displace farmers and destroy agricultural assets and food stocks. Displacement is both a driver and a consequence of food insecurity. When people are displaced, they can lose access to essential resources like food, clean water, and healthcare and become more vulnerable to malnutrition and hunger. Hunger is well-traveled.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 2 is to end hunger by 2030. Ongoing conflict, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and extreme weather events have intensified existing inequalities globally, making this goal even more challenging. Today, more people are hungry than at any other point in human history. They are concentrated in the developing world, and their hunger has been exacerbated by several factors related to conflict theory. Over 800 million people, or 10% of the world’s population, go to bed hungry (FAO, et al. 2023.) Hunger never sleeps.

In the United States, however, what strikes us is not hunger, but obesity. According to a recent World Health Organization (WHO) study, more than 1.6 billion people globally are overweight or obese. This epidemic is not limited to America and Western Europe. It is visible in Central and South America, South Africa, and East Asia. In China, the prevalence of childhood obesity rose from 1.5% to 12.6% in eight years. In South Africa, 30.5% of black women are obese (FAO, et al., 2023). Hunger is confusing.

Escalating global hunger and obesity levels might seem like a contradiction, but it is part of a single global food crisis, with environmental, economic, and geopolitical factors. It is perhaps the most glaring way in which global inequality is evident. For most of history, humans hunted or grew food for their own consumption and traveled only short distances from source to stomach. Today, production is concentrated in parts of the world where transportation, refrigeration, and fertilization escalated and became more globally connected and energy-intensive than ever before. Well before the 1970s oil crisis and current biofuel controversy, food and energy systems have been inseparable. This system created a sustained caloric rift dividing western Europe and North America from much of the rest of the world. The combination of energy-intense agriculture and distribution with globalized asymmetry of consumption patterns made food crises on a global scale possible. Hunger is calculated.

Perhaps the old axiom holds that society is a mass of people who get hungry at the same time. The question is, hungry for what? On the developed side of the caloric rift, fat is accumulating at a startling rate. On the developing side, huge populations are increasingly vulnerable to famine and hunger. In 2024, we live in a world divided into fat and hungry zones. People who live in the hungry zones are hungry in the most fundamental sense of the word. Those fortunate enough to live in the fat zones are hungry for the advanced levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. These are fat zone problems. Hunger is biased.

Once the needs at the bottom three levels of Maslow’s hierarchy have been satisfied, the esteem needs begin to play a more prominent role in motivating our behavior to acquire the respect and appreciation of our peers. This is about needing to accomplish things, having our efforts recognized, and contributing to the world. Together, the social and esteem levels make up what is known as the psychological needs of the hierarchy. Hunger is mental.

The top level of Maslow’s hierarchy is the self-actualization needs. In short, it is about achieving one’s full potential. Once we fat zoners are comfortable enough that our survival is assured and we can focus our bandwidth on existential crises, we pursue the need to self-actualize. As Maslow put it, “What a man can be, he must be.” Hunger is subjective.

People today living in hungry zones around the world know true hunger. The physical kind. The kind that hurts. The kind that is ever present develops its personality and shapes the way a person makes decisions by conditioning them to operate from a mindset of scarcity. The hungry zoners have what Maslow (1943) calls deficiency needs which arise from deprivation. Satisfying these lower-level needs is important to avoid unpleasant feelings or consequences. Hunger is denial.

Fat zoners have growth needs. A mindset of abundance allows for these so-called needs. These are the advanced needs at the top of Maslow’s pyramid. These needs don’t stem from a lack of something, but a desire to grow as a person. Hunger is desire.

As Europeans colonized the world and built food systems that underpinned their industrialization and development, they embedded dietary inequality within these systems. The global food crisis is a product of these past practices. One of the greatest challenges of the twenty-first century, then, is to find a way of overcoming this history and producing a more equitable global food system, one in which the fat zoners lose some weight and the hungry zoners gain some. Hunger is balance. Hunger is equity. Hunger is a hierarchy.

Works Cited

Coser, L. A. (1956). The Functions of Social Conflict. New York Free Press.

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2023). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en

“Hunger.” Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, Retrieved March 10, 2024. https://www.oed.com/dictionary/hunger_n?tab=factsheet#1153877.

Maslow, A.H. (1943). “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review.

Omer, S. (2024). Global Hunger: 7 Facts You Need to Know.” World Vision. https://www.worldvision.org/hunger-news-stories/world-hunger-facts.