story by Aaron Moeller, Vice President of NeuroBats of ACCess Autism, ACC GROW associate, Music

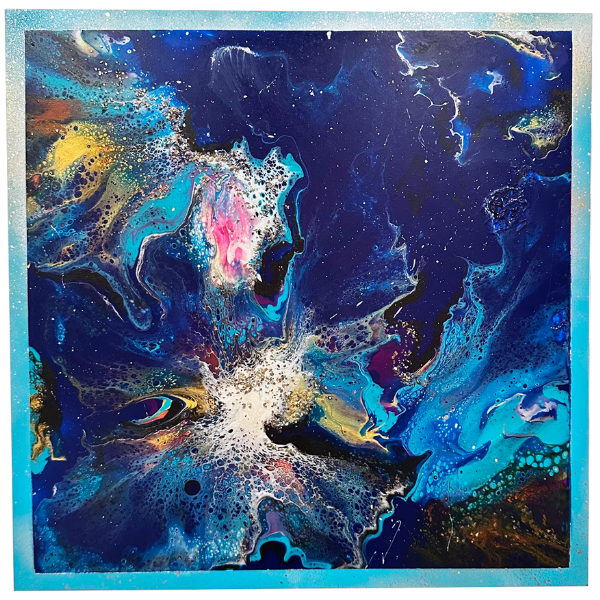

illustrations by Danielle Moak, President of NeuroBats of ACCess Autism, ACC GROW associate, Game Art

Content warning: Mentions of self- injurious behavior and sexual assault.

Many times, I feel as if I am a fish without a school and lost at sea.

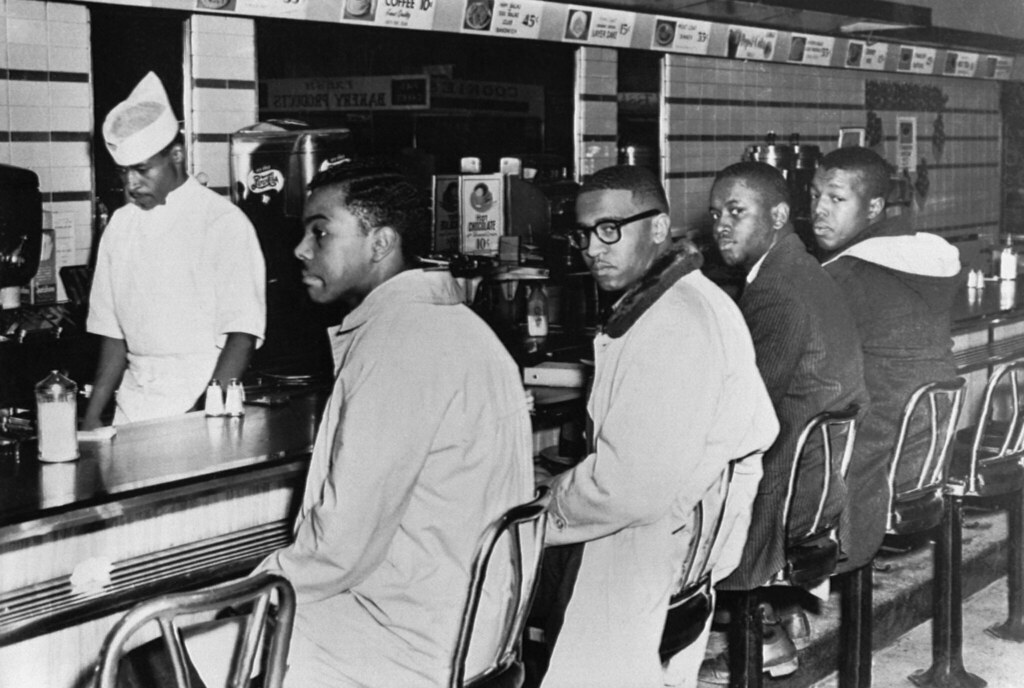

Around me are sharks of every shape. The world abroad has people who can do amazing things. In my community, there are other fish like me. We recognize each other, listen, and lift each other up. The entire world should learn a lesson from our community; we are all equal, and everyone deserves to be seen.

When I leave my community and venture out into the world, I experience a different feeling. I can sense the phoniness and the competition permeating everything. It reminds me of sharks fighting over the last fish carcass. Being in the world and disconnected from my community makes me never want to leave them. In our own spaces, we use our voices to ensure that everyone around us is heard. My college’s leadership had recognized me in the past and given me opportunities I will never forget; however, that changed when a wave came in and pulled me out to sea and away from my institution.

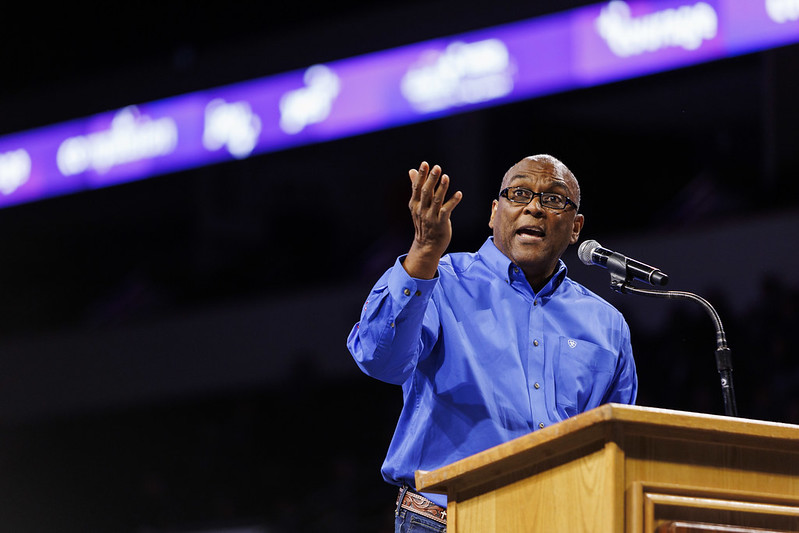

Last year, I submitted a proposal to talk at SXSW EDU, an international convention. This was the first time I would ever do something like this. My talk would be about how it feels to be an autistic student. I also talk about the abuse and trauma I have experienced in my life but also how I was able to triumph over it all. This was one of the most fulfilling experiences I have ever had; having my peers stand beside me and those who attended my presentation saved me from intrusive thoughts that “nobody would care.”

I was proud that I was the only student at my college to get accepted. I prepared for over a year for this presentation, and I allowed myself to completely unmask and divulge my autism so that the audience could understand, to the best of their ability, how it feels to be autistic in a world that feels like it is not made for me.

After I finished the presentation, I was elated; I had accomplished the impossible, at least impossible to myself. I never believed I had a voice that could reach others and propel institutional change. I was always told that autism did not exist, that it was an excuse to be lazy, and that nobody cared, but I proved everyone who told me that wrong.

However, after I gave this presentation, my entire world crumbled. I began having intense flashbacks from my past. I had never spoken about such personal and secret parts of my past to such a large group of people, which included me being sexually assaulted, having to learn how to mask to survive, and how writing became an outlet for me to use my voice in advocacy.

It felt like my entire mind became an ocean, and I was lost at sea. I desperately needed to get ashore but did not know how to ask for help. I would look around and see everyone around me, but my world felt like an underwater volcano about to erupt, one nobody could see coming. I screamed internally, waiting for someone to hear me.

I would look online for some closure. Someone there may acknowledge what I have done. My entire life, I have wanted to build and create something—something that can withstand time and create a legacy for me, one that helps other autistic students after me. That is why I did that presentation: to let other autistic and neurodivergent people know that they have a voice, too.

My brain told me, “Nobody cares about what you did; it is worthless, and you made a fool of yourself.” It told me this for weeks.

A month passed, and now, my favorite month, Autism Acceptance Month, was upon me. April is very special to my friends and I. It reminds us that we deserve to be recognized and that we are humans who also deserve respect and understanding. I could not get myself to smile, though, and I faded into bleak silence as I sunk deeper into my depression.

“Everyone forgot about your accomplishments; they are not even that good. Get over yourself. Nobody cares,” my brain would tell itself.

I would search online to see if my institution had posted about my presentation, but I did not see it. I desperately kept refreshing the webpage to see if they would acknowledge me, not just an autistic student, but a non-binary, gay, first-generation Hispanic student who vulnerably put themself out there to educate others on my experience being autistic in college and what support our institution offers. Yet, with every click of the mouse, there was nothing. I then waited to see if my institution would recognize Autism Acceptance Month, but they did not.

I began to sink even deeper. I lost sight of who I was and why I was alive. Why should I live in a world that does not recognize me or the pain I go through? I did not want to withstand it anymore. I did not want to live.

I could not handle the noise inside of my head. It felt like a thousand knives were scraping my bones, and I was grasping at them, but every time I lunged, the knives cut deeper. I convinced myself that I would never succeed and be recognized no matter what I did. I would never be like other students who are “good enough” to be on the front page of my institution’s social media accounts. What did I do or say that was so wrong? Is it because I am autistic?

I screamed and pulled my hair out while I tried to understand what was happening. I just wanted the pain, noise, and intrusive thoughts to end. Was it true that nobody cared about my accomplishments? Probably not, but that did not matter. When my college fears acknowledging me, I feel disconnected from the institution I love. If my brain tells me I will never end up like those successful students on the front page, what evidence do I have to refute that? My mind may be correct. Maybe I am not meant to do great things, and perhaps I am meant to wallow in filth until I die.

I went to work and saw my friends again after some time. I saw my Transformation Coach and everyone who has always stood beside me. I looked at them all and told them I loved our community; they did not know I had already given up.

I looked at all of them from head to toe. I noticed their clothes, their faces, and how they smiled at me when I met them in the eye.

They are my support group.

I was asked to think about why I do advocacy work. Seeing them reminded me that we do this for the greater good, for others like us who may not be as privileged.

I have a community, yet I cannot forget the feeling deep inside me, one that my intrusive thoughts were trying to surface. That we are not worth acknowledging.

Why is it so important that my neurodivergent community and I are acknowledged for our work? If my institution acknowledges us, it gives the greater internal and external community hope that this is where anyone can find a sense of belonging.

My community may not be what everyone defines as “perfect.” My friends may not be enough for my institution to acknowledge publicly and consistently, but I can accept them just as they recognize me. I can continue using my voice to lift my community just as they lift me.

In the end, the feeling of isolation may never fade. Why are we not good enough to be acknowledged? Why are our accomplishments, the trials we have overextended ourselves to achieve, not presentable?

I began remembering everything our community has created to highlight autistic and neurodivergent voices, including our artwork, newsletters, presentations, and more. It made me realize I was being noticed the entire time—by those who matter the most.

At that moment, I was no longer lost at sea; I was pulled ashore. My community and Transformation Coach held me up even though I could not breathe. They held me together when my institution’s fishing lure tangled me. They helped me stay calm when there were only sharks circling me.

They knew the exact words and when to say them; I did not need to beg them for it. That is what I wish my institution did for autistic and neurodivergent students: not acknowledge us because we are neurodivergent but because we are human, too. In the vast ocean of people, there is room for each color to swim. Will others notice and bring us to shore, or will we be lost at sea?

This article was last updated on 10/16/2024: The caption for the first photo was revised from “Drowning in Overwhem” to “Drowning in Overwhelming. Please note the online copy reflects the update, earlier printed copies may not.