by Marisela Perez Maita

Every year in Austin, Texas, the popular festival, South by Southwest, brings a stream of creativity and transformation to the city. Commonly shortened to SXSW, the multi-day festival hosts an array of conferences on different topics and issues, ranging from film and music to education and technology. In March of 2023, two SXSW conferences on art and civil engagement discussed the current role of data handling–one showing its artistic versatility and the other its legal implications on civil rights.

First panel: Data Art: Processes and Perspectives

Artists Jane Adams, Laurie Frick and Sara Miller shared their perspectives and approaches to “data art.” Ranging from different disciplines –Computer Science, Fine Arts and Data Visualization Design–their artwork explores the versatility of modern art and the beauty of mathematical patterns. All three data artists show how the visual representation of quantitative information is another way to illustrate our state as users and consumers. By unifying concepts of art and science, they emphasize the mathematical and computer processes that surround us.

According to freelance artist Laurie Frick, reality and identity can be seen in the rhythms and sequences of users’ data. She shows how these sequences tend to repeat organically and constantly, “There’s something about actions or behavior, what individual people do, that has [a] symphony to it.” Frick said at SXSW. The patterns and repetitions she finds guide her artistic path of intentional visualization, “With my work, I try to make data feel ambient.” Frick said, meaning to transform abstract information into an understandable expression of human experience and interactions. “I try to look at it [data art] a little more poetic[ally] and try to find something that’s true and will be true for a while.”

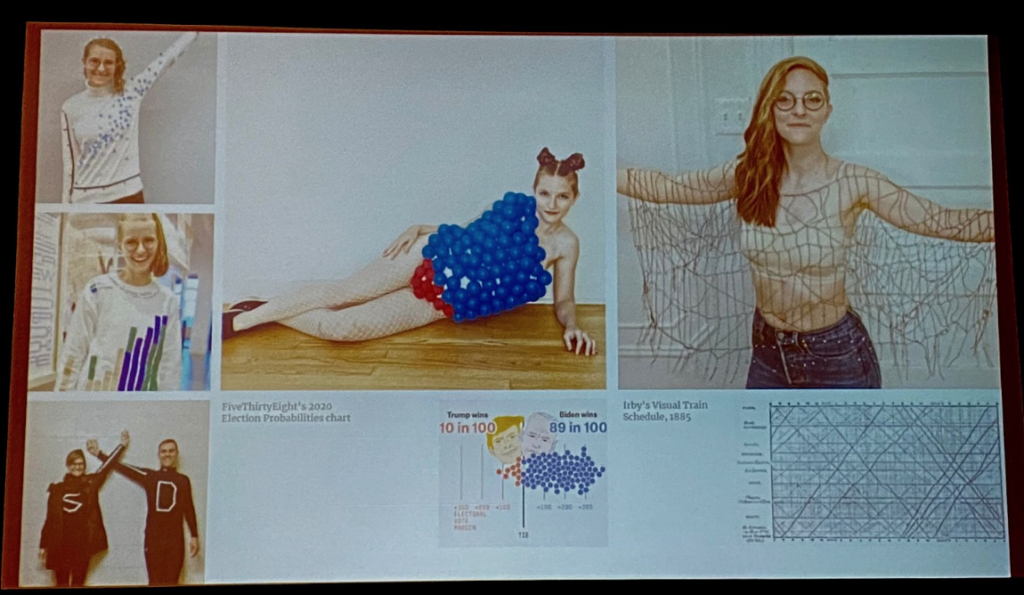

The second speaker, Sarah Miller, says data art is a wide and inclusive spectrum that ranges from AI to hand-crafted sculptural installations. Miller encourages artists to directly use data as inspiration to create something greater or different, or rather as she does, to visualize hard data through art. As a data visualization designer, she has worked with clients such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the University of Chicago, and the Museum of the City of New York.

Conversely, the third speaker Jane Adams has an interesting mix of both science and design. She is a doctoral student in Computer Science at Northeastern University and holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in Emergent Media from Champlain College. She described the discipline as treating data like a medium instead of a subject, pointing out the interesting parallel between data art and data science as involving inquiring processes with different motives, “If you are coming from science, there is faith that your data will still be beautiful, and if it does, it might strengthen it, and your methods can come across more clearly when you take art into account,” Adams said.

Their work

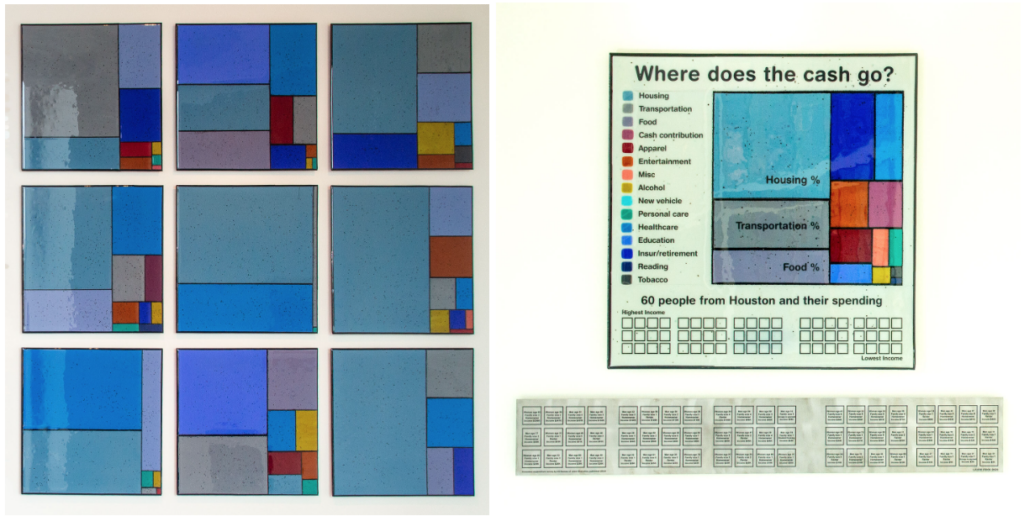

For Frick, being a data artist implies thorough and extensive research. At SXSW she spoke about a commission she did for the Houston Federal Reserve, one of the three branches of money distribution of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Frick was completely mesmerized by the quantity of cash in the bank, “It was like a fortress with billions of dollars in cash inside it” Frick said.

All of her projects start with that: a first glimpse at the information that surrounds her, which soon becomes an inquiring, looking, and researching—or what she calls the hunting process, “Once you’ve got a project, you go home and sit from your computer and you start hunting. Where does the cash go? How often does it transit to people’s hands? What is the history of money?” Frick said.

During her research, Frick found a government survey done by the U.S. Department of Labor trying to understand how people are actually spending money. It was a detailed dataset from the responses of around 6,000 people and their spending on food, clothes, insurance, medical costs and more. As she examined all this information and compared the responses, like someone making $250,000 to another making $10,000, she realized that the answer to her question: “Where does the cash go? ” was determined by income and inequality—she said that this pattern is the one she needed to follow and visualize.

Frick’s artwork is composed of 60 glass squares of different colors and sizes. The color represents a category–housing, transportation, personal care–and the size is the amount of money spent on it. The squares aligned next to each other offer a personalized view of someone’s reality, a crude and transparent representation of their necessities, limitations and behavior.

Moreover, Sarah Miller discussed one of her projects called “The Digital in Architecture,” a report produced by SPACE10, IKEA’s research and design lab. Following an extensive research paper about the history of architecture and the digital tools that are used in architecture, the project explores how those tools affect what gets built and what those creations look like, “It was this really comprehensive paper and we decided to collect data so that we put together our own database of famous buildings and particularly buildings that were mentioned in the two-dimensional paper” Miller said.

Before coming up with a design, Miller and the group of researchers and designers collected information about different aspects of buildings. Answering questions like, “How wide is the building? What’s the purpose? Is it a home? A museum?” Miller said, “We collected all this information and put it into a Google Sheet. And then after that, we came up with kind of sketches and ideas for like how to visualize this.”

The result was a printed tabloid-sized report that maps 160 building projects and their different designs, technology, sustainability and materials. The report follows the principle of data humanism, which aims for data visualization that connects people with numbers. In Miller’s works, the graphic patterns allow readers to closely examine the micro-illustration of each building while they contextualize them in the historical timeline.

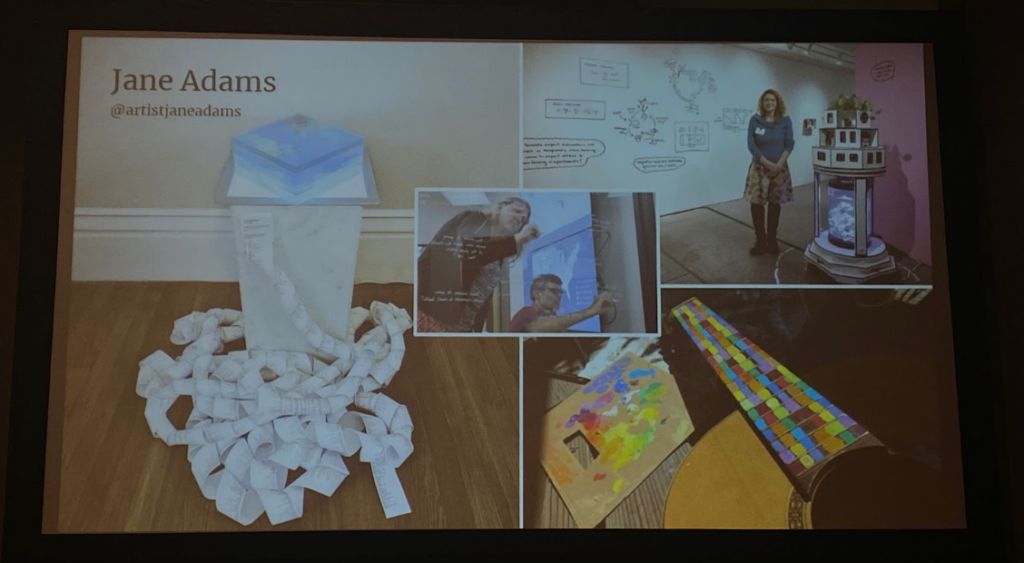

Lastly, Jane Adams talked about her most recent work —a sculpture of a Latent Walk video captured by an Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) model she trained. IRL is a technology that, in Adam’s case, is used to extract stock images from aerial drone photographs. From this, Adams scripted down over 17,000 images, printing them in transparent films and layering them one upon another. However, Adams soon decided to add a new element to the piece, “What you’ll see coiled around the bottom is actually something that I added after based on joyful discussions that I’ve been having with people about training data and ethics,” the artist said, “I was wondering what it would look like to actually credit every single photographer who had contributed art to the training data. So that’s actually a 120-foot roll of all of the credits for all of the training data that was in the model.”

Among the three artists, Adams’s work is the most related to robotics and computer science. She focuses on interactive mixed-media installations, aquaponic sculptures, and GAN art, exploring the evolving relationship between art and science.

As shown by the panelists, data art is as broad and diverse as the artists want it to be. Their work can’t be compared to the work of statisticians and analysts, and yet data artists allow a communicative path between us and the digital and quantitative world we have created.

Second panel. It’s Time to Stop Denying Privacy as a Civil Right

From artistic visualizations and subjective interpretations, the civil engagement panel flipped the conversation on data 180-degrees at a different panel in the Hilton Hotel. Speakers Christopher Wood, Nicol Turner-Lee, Koustubh “K.J.” Bagch and Amy Hinojosa explored the exhaustive spectrum of data surveillance and its abuse of user privacy. Without being aware of why, when, nor how often it happens, users’ information gets collected and sold to a hidden market composed of third-party apps, big companies and the government. In addition to exposing this hard-to-perceive network, the speakers emphasized the importance of affording data privacy as a civil right.

The discussion was led by entrepreneur Christopher Wood, the executive director and co-founder of LGBT Tech, a national organization that works at the intersection of LGBTQ+ and technology. According to Wood–who has 15 years of experience advocating for the LGBTQ+ community– data surveillance is especially dangerous for populations who have been historically marginalized. LGBT Tech’s mission is to ensure LGBT communities are addressed in public policy conversations. To start the panel, Wood asked the panelists what data privacy concerns they had and how they addressed them in their work.

For Hinojosa, people should have a say on their own health care decision and who has access to it—but data collecting and sharing have grown unbridled. The unclear ownership opens a door to unregulated access to personal healthcare information, “Be it women, trans kind, people of color, anyone who these legislators think are making healthcare decisions that are against their version of morality, are vulnerable to be targeted and persecuted for it.” Hinojosa said.

Amy Hinojosa, the president of the oldest and largest Latina membership organization in the United States, the Mexican American Women’s National Association (MANA), explained that her 16 years working in the organization on behalf of women has made her overly concerned about the weaponization of women’s healthcare data, especially the one of reproductive care. She brought up the Dobbs vs. Jackson Supreme Court decision and its detrimental effect on abortion access and healthcare privacy, “If you are using a period app or tracking your ovulation because you’re trying to get pregnant, this is now information that’s being tracked and in many cases shared, and there’s nothing to protect you.”

Moreover, Koustubh “K.J.” Bagchi is the Chamber of Progress of New America’s Open Technology Institute (OTI). Based in Washington, New America is a center-left association that focuses on public policy issues related to national security, gender, economy, technology and more. Working with 28 industry partners—such as Amazon, Crypto and FinTech—OTI operates at the intersection of policy and technology to bring reforms that foster open and secure communication networks. Bagchi has worked over 10 years on issues that impact marginalized communities, from working for a Washington D.C. council member on consumer protection to now chairing tech policy initiatives between OTI and partner companies.

As a policy institution, New America gets involved with any local-level issue, and aims to resonate with the lawmakers of the whole country. “The common theme of all these roles [within the organization] is how do we actually empower individuals to know what their rights are when it comes to this variety of issues? And also what policies should we be advocating for to make sure that folks are actually adequately protected?” Bagchi said. The conversation of privacy is usually centered on the bigger companies—Google, Amazon, Apple—when actually, the government is a crucial agent in the cycle as well, Baghci added, “There is not enough conversation around the fact that our government has found a way to collect data from consumers and users all across the country, without using the sort of traditional legal protections that we’re used to.”

The law allows “probable cause” to protect individuals against unwarranted intrusions into their private lives—but jurisdictions get blurrier in the online space. According to Baghi, the government slips away from legal repercussions by making deals with entities known as data brokers—businesses that collect information both from public and private views. Information can be aggregated from social media profiles or companies’ websites, or agreements with third-party apps. Data brokers make deals with developers to include a software development kit that, once the user downloads the app, allows the data broker to collect anonymous location data, “What’s been happening is that they [data brokers] have been selling that data to the government. To law enforcement entities all across the nation on a commercial basis,” Baghi said at the panel.

He then referenced an incident with The Department of Homeland Security surveilling Muslim users through praying apps in 2020, “There were three separate apps that were essentially helping users identify mosques in their area or to identify what time and direction they should pray” Bagchi said, “One of these apps had over 10,000 downloads, and this information was sold to agencies that have historically surveilled Muslim communities.” The case was revealed through investigations by the non-profit organization Electronic Frontier Foundation and shared by newspapers like The Guardian and Los Angeles Times.

Likewise, Baghis’ points illustrate the fortified surveillance that Nicole Turner-Lee asserted in the conference, “We’ve emboldened a system of technological surveillance that lends itself to discriminatory, racist, homophobic and gender violence, and it’s done in a way that it’s so opaque that we don’t even know what’s happening to us.”

Turner-Lee is the director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, where she focuses on legislative and regulatory policies targeting high-tech industries and telecommunications. She explained the implications of the normalized “trade-off”—people accepting cookies, terms and conditions, or giving their driver’s license picture without knowing that consent can lead to discriminatory outputs.

Privacy policies are not comprehensible, so it makes it even harder for consumers and users to understand what they’re signing up for; Turner-Lee said, “Most privacy policies are written for lawyers, not for basic individuals who are navigating quickly through stuff.”

The speakers described how technology appears to be based on an incompressible trade-off economy where users can’t say what, how much, and how often information is collected about them; but it’s either accepting the whole deal or not accessing the online space where everyone lives, so users click yes by default.

“The challenge is when you are marginalized and the extent to which that data, either too little of it or too much, also plays a role in sort of demonizing and weaponizing it against you,” Turner-Lee said. She brought up the case of three misidentified African-American men who were accused of crimes they did not commit after the police used facial recognition software. This technology has shown significant flaws with Black and Asian faces, and yet law enforcement keeps relying on it on a regular basis. Hence, as Turner-Lee points out, the concerning implications of minorities consenting to provide personal data–be it pictures or information–under a system of inequality that already targets them.

The conversation on government surveillance and legislation’s lack of clarity in the growing digital domain could only lead to a discussion over civil rights. As Woods said, “It becomes a civil right issue where we’re not counted, we’re not included, we’re not at the table and therefore it’s really easy to say that we don’t exist, but yet we’re the ones suffering on both sides of that coin and that data.”

States such as California, Vermont, Colorado and Oregon have taken the initiative in passing privacy bills that regulate data brokers. Yet, Turned-Leed explained, that state variation policies lead to a different kind of complexity. As states start developing and designing privacy laws, they set the bar. Action that resonates with preemption, of whether or not the government should actually permit and abide by state rule.

Moreover, Turner-Lee points out the possibility of privacy laws reflecting a lot of the sentiment against critical race theory and the state’s transgender community, reemphasizing Hinojosa’s concern about legislators’ morality on top of people’s rights. Turner-Lee stressed the necessity of a federal mandate that guides the conversation and emboldens civil protection in the digital space as well, “We’ve seen brokers and other algorithms skirt on the edges where they’re violating civil rights law without any type of recourse or reprimand,” Turner-Lee said.

The work of the SXSW panelists Woods, Hinojosa, Baghi and Turner-Lee aims to educate communities, organizations and consumers to better understand what they’re giving up when they click cookies, and encourage them to start advocating for their rights and demand comprehensive policies.

“We do need regulation,” Turner-Lee said. “I think what we found with regulation at least inspires companies to not just think about their reputational appearance, but to do things that are in much more better compliance for consumers–and that’s something I think as I look at it as a former advocate, still an advocate on the research side, without regulation, it’s hard to enforce anything.”

Update: In July Governor Abbott signed the Texas Data Privacy and Security Act (TDPSA) that regulates data brokers operating in the state, becoming the 10th state– and 5th in 2023– to pass a comprehensive privacy law. The act will be effective in July 2024.