“I once said ‘We Will Bury You’ and got into trouble with it. Of course, we will not bury you with a shovel. Your own working class will bury you.” –- Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev Speaking to West, 1963

More so than many of the advisers, politicians, and physicists around him, the Cold War conflicted President Dwight Eisenhower, aka “Ike.” To understand why you need to grasp the unprecedented magnitude of the Cold War. A 1959 Strategic Air Command battle plan declassified in 2015 lays out U.S. plans for a wave of B-47 and B-52 bombing raids that would’ve killed an estimated 285 million people the first day in China, the USSR, and Eastern Europe, with Western European allies sacrificed as collateral damage from radiation fallout (visualization). Those estimates don’t include long-term radiation poisoning or a potential nuclear winter. The Soviets had similar plans for the Western Hemisphere. Ike, the Supreme Allied Commander from WWII, said as he entered the White House in 1953 that “wars are stupid, and can start stupid.” He explained his concern about the prospect of destroying the Soviet Union to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1954: “Here would be a great area from the Elbe to Vladivostok…torn up and destroyed, without government, without communications, just an area of starvation and disaster. I ask you, what would the civilized world do about it?” In the video above in 1953, he talked about the arms race as a colossal waste of resources.

Like Richard Nixon and [post-Iraq/Afghanistan] Obama-Trump-Biden, Eisenhower was what historians call a “retrenchment” president, overseeing a gradual pullback and re-orientation after a conflict rather than increased military intervention. In Ike’s case, he wanted to end direct conflict in Korea. Yet, to the chagrin of Winston Churchill, when Josef Stalin died in 1953, Eisenhower didn’t initially pursue a more peaceful dialog with his successors. As the USSR quickly transitioned from Stalin to Georgy Malenkov and Vyacheslav Molotov to Nikita Khrushchev, intelligence suggested that the new leaders wanted to reconsider their relationship with the West, but Ike “doubted the wisdom” of talking to the Soviets at the time and suspected it was just another ploy for Soviet propaganda. The new leader Khrushchev was an improvement over Stalin, no doubt, but was hardcore enough in his own right. He was the general primarily responsible for the Soviets’ defense of Stalingrad during WWII and helped Stalin carry out purges, though he later denounced them.

The bottom line for Ike was that the U.S. had to play a leading role internationally to maintain peace and that required staying strong militarily. The world seemed to be coming apart at the seams in the early 1950s. The Arms Race was on after the Soviets exploded an atomic bomb in 1949 and then quickly matched America’s 1952 hydrogen bomb test in 1953. The U.S. was at war in Korea against Soviet and Chinese-backed troops and China had gone communist in 1949. The Soviets were flexing their muscle in Eastern Europe, Egypt was starting to lean left, Iran was a mess, and there were colonial wars going on against the French in Algeria and Indochina. The Soviets’ long-term goal, at least as far as American intelligence could tell, was the overthrow of the U.S. government. Ike had all he could do to walk an eight-year tightrope between capitulation and nuclear annihilation.

Some historians doubt that anything could’ve been done at that point to ease tensions, given the deep ideological rifts between the two powers and the added complication of the nuclear arms race. Eisenhower’s foreign policy is a good example of the limitations on individual power. On the one hand, individuals had more power than ever because leaders in the U.S. and USSR had “their fingers on the button.” Yet Eisenhower couldn’t stem the bigger tide of history and wind down the Cold War, as he hoped. Just as the Renaissance Italian Niccolò Machiavelli (right) wrote about the tension between fortune and free will in The Prince (1532), modern historians talk about structure versus individual agency. “Agents” like presidents have only so much power to nudge the “structure,” or tectonic shifts, of history in one direction or another. If you envision political leaders on land, then economics, technology, and social/cultural history are moving beneath them deep in Earth’s crust. The advent of Web 2.0, for instance, was a seismic shift in your own time, arguably more important than the actions of any individual politicians. Power always flows in multiple directions simultaneously. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that “circumstances rule men; men do not rule circumstances.” Even Abraham Lincoln, who had as much individual impact as any American president, said, “I claim not to have controlled events, but rather that events have controlled me.” The Cold War onset of nuclear power was one such tectonic shift and, like Lincoln, Eisenhower could only manipulate events as best he could.

Some historians doubt that anything could’ve been done at that point to ease tensions, given the deep ideological rifts between the two powers and the added complication of the nuclear arms race. Eisenhower’s foreign policy is a good example of the limitations on individual power. On the one hand, individuals had more power than ever because leaders in the U.S. and USSR had “their fingers on the button.” Yet Eisenhower couldn’t stem the bigger tide of history and wind down the Cold War, as he hoped. Just as the Renaissance Italian Niccolò Machiavelli (right) wrote about the tension between fortune and free will in The Prince (1532), modern historians talk about structure versus individual agency. “Agents” like presidents have only so much power to nudge the “structure,” or tectonic shifts, of history in one direction or another. If you envision political leaders on land, then economics, technology, and social/cultural history are moving beneath them deep in Earth’s crust. The advent of Web 2.0, for instance, was a seismic shift in your own time, arguably more important than the actions of any individual politicians. Power always flows in multiple directions simultaneously. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that “circumstances rule men; men do not rule circumstances.” Even Abraham Lincoln, who had as much individual impact as any American president, said, “I claim not to have controlled events, but rather that events have controlled me.” The Cold War onset of nuclear power was one such tectonic shift and, like Lincoln, Eisenhower could only manipulate events as best he could.

Paradoxically, Eisenhower could see the insanity of the Cold War and wanted to end it, but instead oversaw the buildup of America’s nuclear arsenal. The U.S. nuclear stockpile grew from 50 weapons to 12,000 in the 1950s. He and his Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, preferred bombs as deterrents to the large-personnel army Ike oversaw during WWII. In terms of cost-effectiveness, nukes seemed to offer the U.S. more “bang for the buck.” Yet Ike differed from many of his contemporaries, including Pentagon advisors and VP Richard Nixon, in his belief that nuclear weapons should not actually be used, except out of desperation. As we saw in Chapter 12, he opposed the atomic attacks on Japan that ended WWII. As president, he showed restraint, willing to use the nuclear threat of what he called “massive retaliation” but preferring to avoid bombing or even any armed intervention whenever possible. This deterrent threat is still around today, which is why the U.S. and Russia fear escalating war with each other.

When he campaigned in 1952, Ike promised to abandon Truman’s containment policy in favor of a more aggressive liberation policy toward communist-controlled areas. But he quickly abandoned that idea and reverted to the more moderate, containment policy. Eisenhower signaled that approach early by arranging an armistice to draw down the Korean War, though he threatened a nuclear attack to do it. He resisted intervention in the 1956 Hungarian Uprising against Soviet control of that Eastern Bloc country, even after American agents had encouraged the rebellion. In the Formosa Straits between China and Taiwan, Ike avoided being pulled into a major conflict over the small islands of Quemoy and Matsu, but he used Chinese operations there as an opportunity to declare America’s commitment to protecting Taiwan, which continues to this day. Ike scolded his advisors for their reckless willingness to resort to atomic weapons: “You boys must be crazy. We can’t use those awful things against Asians for the second time in less than ten years.” Likewise, in Laos and Vietnam, he was hesitant to commit U.S. troops to ground combat but offered assistance to non-communists in the form of aid, training, etc.

When he campaigned in 1952, Ike promised to abandon Truman’s containment policy in favor of a more aggressive liberation policy toward communist-controlled areas. But he quickly abandoned that idea and reverted to the more moderate, containment policy. Eisenhower signaled that approach early by arranging an armistice to draw down the Korean War, though he threatened a nuclear attack to do it. He resisted intervention in the 1956 Hungarian Uprising against Soviet control of that Eastern Bloc country, even after American agents had encouraged the rebellion. In the Formosa Straits between China and Taiwan, Ike avoided being pulled into a major conflict over the small islands of Quemoy and Matsu, but he used Chinese operations there as an opportunity to declare America’s commitment to protecting Taiwan, which continues to this day. Ike scolded his advisors for their reckless willingness to resort to atomic weapons: “You boys must be crazy. We can’t use those awful things against Asians for the second time in less than ten years.” Likewise, in Laos and Vietnam, he was hesitant to commit U.S. troops to ground combat but offered assistance to non-communists in the form of aid, training, etc.

Containment Gets Complicated

Ike stayed the course with Truman’s Containment Policy, despite his initial promises to the contrary. He transformed Cold War tactics, however, by pioneering use of the new Central Intelligence Agency, or CIA. The president realized that small, secret covert operations were cheaper, nimbler, and less noisy than traditional military missions – ideal, for instance, in staging revolutionary coups d’état. In doing so, Ike blazed another new trail in Cold War policy: overthrowing democracies. That sounds strange at first to American readers, because the ostensible purpose of the Cold War was to see through the victory of democracy over communism and Americans juxtaposed the two forms of government. Since the USSR (Soviet Union) and other hard-core communist countries were dictatorships, the confusion was natural. America, after all, was a capitalist democracy and the USSR was a communist dictatorship. But democracy is the political opposite of dictatorship, and communism is the economic opposite of capitalism. Oftentimes capitalism and democracy have dovetailed well and reinforced each other, especially in Anglo-American history. But there’s also tension between the two (e.g., slavery in the U.S.) and sometimes they work at cross-purposes when the will of the people interferes with companies maximizing profits. At times, during the Cold War, the U.S. overthrew or at least helped overthrow socialist democracies and replace them with capitalist dictatorships.

Let’s put this in proper perspective before we unpack it any further. The U.S. has spurred democracy more than any nation by setting an early example as the modern world’s first large republic in the 1780s, the Union’s victory in the Civil War, and by supporting democratic allies. America’s victories over Germany in WWI, Germany and Japan in WWII, and the USSR in the Cold War catalyzed an ongoing, global democratic revolution. But along the way, the U.S. hasn’t always backed free elections and it hindered democracy in Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America during the Cold War.

George Kennan, who worked in the American embassy in Moscow, laid the foundation for America’s ambiguous, Janus-faced policy early in the Cold War when he helped President Truman formulate the Containment Doctrine. Kennan said the U.S. had about 50% of the world’s wealth and just over 6% of the world’s population. The goal was to “devise a pattern of relationships to maintain that position of disparity without detriment to our national security. To do so we’ll have to dispense with all sentimentality and daydreaming…[we should refrain, especially in the Far East] from unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of living standards and democratization.” (PPS/23) Kennan’s frank words weren’t something politicians echoed in State-of-the-Union talks or U.N. speeches for obvious reasons. But his prescribed policy fits the ensuing Cold War historical record well — better at least than an oversimplified narrative of the West supporting human rights, living standards, and democracy at all costs. While positive things sometimes followed in the wake of American interventions, they weren’t the overriding priority. The United States usually valued capitalism more than democracy when the two conflicted.

In the Cold War, democracies in poorer countries commonly interfered with developed countries’ corporate profits, meaning they had to be snuffed out and replaced with dictatorships friendly to Western interests. Nine times out of ten, the word interests is code for money and, nine times out of ten, one of the first things people do in emerging countries when they win the right to vote is to keep more money and natural resources in their own hands. Turns out, they have interests too. That’s why the U.S. mostly blocked self-determination in Latin America dating back to Teddy Roosevelt’s Corollary of 1904, as we saw in Chapter 3, and that policy continued during the Cold War.

Several Cold War examples illustrate America’s follow-through on Kennan’s advice, including Iran, Guatemala, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil, and Chile (Chapter 19). Other than Israel, there are no examples where the U.S. supported democracy to the detriment of its economic interests. Sometimes, at least, looking out for economic interests could overlap with defending democracy. In South Korea and Taiwan, America’s dictatorial allies evolved into democracies, and the U.S. installed a republic in Grenada in 1983. The Philippines has gone through periods of dictatorship since independence in 1946 but has been a democracy since 1986. Despite the shaky premises of America’s Iraq invasion in 2003 and ensuing chaos, the U.S. did replace Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship with a government that represents some of the people. Other countries weren’t so lucky.

In Iran (then Persia) in the early 1950s, their new democracy wanted a fairer share of oil profits than the 80/20 split under their arrangement with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co., an antecedent to British Petroleum (BP). In 1951, Iranians seized control of the main British refinery in the Abadan Crisis. The U.S. and Standard Oil of California (now Chevron) shared Saudi Arabian oil with the House of Saud 50/50, making the Brits look bad. When Iranians won the vote, they naturally questioned why Britain was plundering 80% of their oil money. However, becoming “owners, or controllers” of oil, as Winston Churchill put it, was critical for the British. Under Churchill’s own tenure as First Lord of the Admiralty, they’d transitioned their naval ships from coal-fired steam to oil-burning internal combustion, but Britain has domestic coal and not much oil. The government assumed majority control of BP to run it with military considerations in mind.

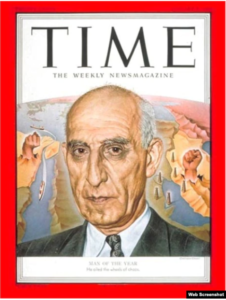

Granted, Anglo-Iranian relations weren’t a pure case of plunder. In the early to mid-20th century, poor countries needed Western engineering to drill for oil. When BP pulled their staff out of Iran during the Abadan Crisis, production plummeted nearly to zero. The British convinced President Eisenhower that Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, constituted a communist threat, leaving out mention of a recent book he’d written denouncing communism. Before Ike, Harry Truman initially liked Mossaddegh because he’d brought democracy to the Middle East, and he visited the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia and George Washington’s plantation at Mt. Vernon to underscore a potential American connection. While not elected directly by the people, he’d been chosen by Iran’s elected parliament, similar to how prime ministers were nominated in England. TIME magazine even named him Man of the Year for 1951 (right). But Mosaddegh wanted full Iranian control of Iranian oil, and the consequent British blockade hurt the Iranian economy and lowered his popularity among the military and mullahs. With Teddy Roosevelt’s grandson, Kermit, leading Operation Ajax, the CIA and British MI6 helped overthrow Mosaddegh and elevated the monarch Shah to a full-on dictator. Operating out of the basement of the American embassy in Tehran, Roosevelt bribed newspapers to accuse Mosaddegh of homosexuality and communism. The Shah hadn’t been a mere figurehead prior to that and had the power to remove prime ministers, so some of the public backed him when Mosaddegh’s popularity plummeted because of Britain’s oil blockade. The U.S. got a 40% share of oil exports for their trouble, much to the chagrin of Saudis and Kuwaitis who didn’t welcome the competition. Most of all, the U.S. got an ally in the region that could hopefully stymie any potential Soviet expansion toward the Persian Gulf. The Shah kept the oil flowing cheaply to BP in return for the money and weapons he needed to stay in power, and he unapologetically murdered and tortured dissidents. In 2023, the CIA acknowledged its undemocratic role in the 1953 coup (AP).

Granted, Anglo-Iranian relations weren’t a pure case of plunder. In the early to mid-20th century, poor countries needed Western engineering to drill for oil. When BP pulled their staff out of Iran during the Abadan Crisis, production plummeted nearly to zero. The British convinced President Eisenhower that Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, constituted a communist threat, leaving out mention of a recent book he’d written denouncing communism. Before Ike, Harry Truman initially liked Mossaddegh because he’d brought democracy to the Middle East, and he visited the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia and George Washington’s plantation at Mt. Vernon to underscore a potential American connection. While not elected directly by the people, he’d been chosen by Iran’s elected parliament, similar to how prime ministers were nominated in England. TIME magazine even named him Man of the Year for 1951 (right). But Mosaddegh wanted full Iranian control of Iranian oil, and the consequent British blockade hurt the Iranian economy and lowered his popularity among the military and mullahs. With Teddy Roosevelt’s grandson, Kermit, leading Operation Ajax, the CIA and British MI6 helped overthrow Mosaddegh and elevated the monarch Shah to a full-on dictator. Operating out of the basement of the American embassy in Tehran, Roosevelt bribed newspapers to accuse Mosaddegh of homosexuality and communism. The Shah hadn’t been a mere figurehead prior to that and had the power to remove prime ministers, so some of the public backed him when Mosaddegh’s popularity plummeted because of Britain’s oil blockade. The U.S. got a 40% share of oil exports for their trouble, much to the chagrin of Saudis and Kuwaitis who didn’t welcome the competition. Most of all, the U.S. got an ally in the region that could hopefully stymie any potential Soviet expansion toward the Persian Gulf. The Shah kept the oil flowing cheaply to BP in return for the money and weapons he needed to stay in power, and he unapologetically murdered and tortured dissidents. In 2023, the CIA acknowledged its undemocratic role in the 1953 coup (AP).

As was the case elsewhere, American military in Iran had full immunity from Iranian courts. These factors, especially support for the Shah, incurred the wrath of many Iranians toward the West, contributing to the Hostage Crisis of 1978-80 and poor relations today with the United States. However, blaming America entirely for Mosaddegh’s downfall is a misleading interpretation perpetuated by modern Iranian leaders hostile to the U.S., Kermit Roosevelt’s autobiography exaggerating his role, and American historians inclined to critique western colonialism. But Iran’s parliamentary system would’ve been healthier without Britain driving such a hard bargain on oil and the CIA nosing around in a coup. If there was one silver lining in this cloud, the Shah emancipated Iranian women, allowing them to attain educations and become doctors and lawyers, drive, wear what they’d like, and enjoy full reproductive rights and legal equality regarding marriage and divorce. He also abolished polygamy and raised the minimum marriage age from 13 to 16. Iranian women lost those rights when Muslim fundamentalists took over the country with their own coup in 1978-79.

America played a more decisive role in Guatemala. Their democracy wanted to boot out the United Fruit Company of Boston (Chiquita brand®), that owned one-third of the country, and take their land back. The company also estimated its land at low value to avoid taxes, so when the country offered to pay the company an indemnity for the nationalized land, they used the same low figures. United Fruit (UFC) ran a major operation throughout Latin America and a plan to keep the company’s real estate was on President Truman’s table as early as 1951. The U.S. had supported a puppet dictatorship led by Jorge Ubico until he was overthrown in 1944, and his two democratically-elected successors instituted reforms to help workers while allowing a communist party to exist within the democracy. Things came to a head after Eisenhower took office, partly because Ike’s Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, owned shares in UFC and his brother, Allen Dulles, was CIA Director. The Dulles brothers were key players during the Cold War and motivated by more than just the fruit company. Eisenhower had originally backed democracy in Iran, for instance, before they talked him out of it.

A small group of CIA operatives and guerrilla rebels got control of the main radio station and used broadcasts to drive a wedge between the country’s army and president, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. The false flag coup resulted in America’s installation of dictator Carlos Castillo Armas, whose faults were many, but who kept cheap bananas flowing north. Ike was impressed with how inexpensive and easy the coup was and how worthwhile it was to hire a professional propagandist, Edward Bernays, to dupe the citizens (Bernays, about whom you can learn more below under optional reading, was Sigmund Freud’s nephew and a veteran of Woodrow Wilson’s propaganda efforts during World War I). This certainly beat the heck out of leading large armies across North Africa or France, as Ike had done in the “Big One.” Best of all, no one really found out about it at the time, except for other Latin American revolutionaries who learned a few lessons of their own from the incident (more later).

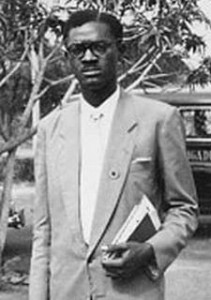

More or less the same story unfolded in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Africa in 1960, which was especially unfortunate given the exploitation Congolese had suffered under Belgium’s colonial rule in their quest for the region’s rubber (worst when governed privately from 1885 to 1908 by King Leopold II). The CIA lent support to Patrice Lumumba’s kidnapping and execution when he brought democratic socialism to that newly independent country, concerned mainly with supporting its NATO ally, Belgium. It gave the U.S. pause when Lumumba appealed to the USSR for backing (like Egypt, below), undermining his simultaneous request to the U.S. for aid and trained emigrants on an awkward trip to Washington one month after Congo gained independence from Belgium. Lumumba also struggled with a military mutiny and his election threatened profits of Belgian diamond and copper companies, so the NATO partners murdered him. Also, as argued in future politician Newt Gingrich’s 1971 Ph.D. dissertation, democracy in the Congo would’ve resulted in a voting black majority outnumbering white ex-colonials. As in South Africa, post-colonials deemed that unacceptable, even though there are racial majorities in all democracies.

The U.S. public was mostly unaware of such operations until Idaho Senator Frank Church led a series of congressional hearings on the CIA in 1975 that culminated in an executive order from President Gerald Ford ending American assassinations of foreign politicians. It was bad public relations to kill elected leaders if caught, and Ford could identify after being shot at by one of the (Charles) Manson Girls, Squeaky Fromme. Ford also served on the Warren Commission, whose research into John Kennedy’s assassination revealed that JFK hired the Mafia to try to kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro. While there was no proof that Castro returned the favor, such scenarios were more likely to unfold if the U.S. continued knocking off leaders. As for Lumumba’s death, Belgium officially apologized in 2002 but the CIA never accounted for their role, detailed in Stuart Reid’s optional article below as America’s first hit on a foreign leader, ambiguously green-lit by Eisenhower while he maintained enough distance for plausible deniability. So ended the African continent’s first foray into democracy. On the eastern Horn of Africa, the U.S. opposed a democratic uprising in Eritrea, maneuvering to keep it part of the Ethiopian regime that was allied with the U.S. against the USSR.

In Brazil, the U.S. backed a 1964 military coup d’état to overthrow leftist João Goulart’s presidency in favor of a right-wing military dictatorship. Thus, while the U.S. boosted the overall cause of democracy worldwide by winning the Cold War, in doing so they overthrew the first democracy in post-colonial Africa and major democracies in the Middle East (Iran) and Latin America (Brazil). As we’ll see in Chapter 18, in its biggest military venture of the Cold War, the U.S. prevented elections in Vietnam out of fear that communists would win. The U.S. even supported a military junta in Greece, of all places, the birthplace of democracy. Aside from fears of having the wrong people win elections, there was often genuine concern about the difficulty of conducting fair elections in unstable regions. It’s hard to pull off completely clean elections even in stable countries and the U.S. valued the dependability of dictators in fending off communism. People wrongly remember ideological simplicity as one upside of the Cold War. Even at the time, most Americans never knew how complicated it was.

The Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis

The Soviets and Americans couldn’t just run roughshod over the rest of the world, though. In fact, both spent more time kissing up than assassinating leaders. They had to behave reasonably well to curry favor and win developing countries over to their respective ways of life. Countries could gain favors from either superpower by threatening to align themselves with the other. Most countries had to choose — India and communist Yugoslavia were notable exceptions (non-aligned movement) — but countries could also get aid that they otherwise would not have received. Eritrea, for instance, got millions in U.S. aid during the Cold War and maintained friendly relations for the most part. Egypt was another case in point.

President Eisenhower hoped to loan money for weapons and a dam near the source of the Nile River at Aswan, to better regulate flooding in the lower Nile Valley and boost agricultural productivity, but the deal fell through. Eisenhower learned that Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser was playing the Americans and Soviets off against each other, hoping to bid up economic and military aid. It also concerned the U.S. that Egypt would use American weapons on their ally Israel. Moreover, it angered Secretary of State Dulles that Egypt recognized Red (communist, mainland) China while the U.S. only recognized Taiwan. In the meantime, southern Senators expressed their concern that helping Egypt’s cotton production threatened U.S. exports. Much to Nasser’s humiliation, Ike retracted the loan offer, sending the new leader into the arms of the Soviets, whom Ike hoped wouldn’t be able to afford the dam’s high cost. Nasser also opposed America’s attempt with the Baghdad Pact (1955-79) to build a NATO-like coalition in the Middle East with Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey to block Soviet influence.

In 1956, Egypt needed more funding and seized the all-important Suez Canal in the northeastern part of the country, built by French and British engineers in the 19th century. Nasser scuttled ships at the canal’s northern entrance to block Europeans from Middle Eastern oil and planned to tax ships for passage. British shareholders dominated the joint-stock Suez Canal Company that owned and ran the canal and Britain already sensed they were losing access to cheap Persian Gulf oil when Mosaddegh’s nomination in Iran threatened to nationalize that country’s oil supply. They saw Egypt as a quasi-colony even if, officially, it no longer was an actual colony. Britain got the American CIA to bail them out in Iran and wanted more U.S. aid in helping to secure the all-important choke point of the Suez Canal — Europe’s passage to the Persian Gulf and East Asia. Led by Prime Minister Anthony Eden, the Brits told the U.S. that “Nasser’s removal and installation of a regime in Egypt less hostile to the West [okay with British control of the Suez]…must rank high among our objectives.” By the 20th century, the British were getting into the habit of throwing the word our around loosely to underscore their American alliance. Eden also hoped that boats would need trained British pilots to navigate the narrow channel, but the Soviets trained Egyptian pilots. After nearly three months of negotiation, with the U.S. both condemning Nasser’s actions but also discouraging force, the British concocted a phony war whereby Israel would attack Egypt and Britain and France would intervene to separate the combatants and protect the canal.

But this time, Ike didn’t bail out the British the way he had in Iran three years earlier. Eisenhower didn’t want a big incident enticing the Soviets or disrupting his upcoming presidential reelection, and that fall the Soviets invaded Hungary to put down an uprising, further distracting him. After their brief war on the Sinai Peninsula and Port Said on the canal, which Britain was on the verge of winning, the nearly apoplectic Ike ordered the allies out of Suez under threat of withholding monetary aid and driving down their currency. He simultaneously sent a message to the USSR directing them to stay out, as well, or be “hit with everything in the bucket.” Who knows how that translated into Russian, but Ike wasn’t talking about his wish list of things to do before he died; he’d already led the Normandy Invasion and won the presidency by then. He meant that he was going to nuke the Soviets back into the Stone Age if they went near the canal. The Soviets, in turn, threatened to nuke Paris and London if the British and French didn’t retreat, inadvertently strengthening Ike’s hand. While the United Nations, not the U.S., officially ordered the French, British, and Israelis to retreat, the upshot was that the U.S. and Soviets were taking over the region from the old imperial powers. Egypt, in turn, retained control of the Suez Canal. Prime Minister Eden’s secretary remarked that Britain, “could never again resort to military action, outside British territories, without at least American acquiescence.” The Suez Crisis showed how the U.S. was able to order European and Israeli allies around during the Cold War while fending off the Soviets at the same time. Nonetheless, according to VP Richard Nixon, Eisenhower called the Suez Crisis his greatest foreign policy failure and regretted that he didn’t support Britain and France.

Soviet money and Egyptian engineering and labor built the High Aswan Dam in the 1960s (right). The Suez Crisis packed a powerful punch historically given that it was a relative blip on the screen at the time. Israel had easy enough success in the brief war prior to their withdrawal that it helped convince them to take more territory from Egypt eleven years later in the 1967 Six-Day War, that we’ll revisit in Chapter 19. Also, Western Europeans resolved to get partly out from under American control. I say partly because they still wanted an alliance and for the U.S. to foot the bill for big-ticket military spending. But Great Britain and France both developed their own nuclear bombs after Suez.

Soviet money and Egyptian engineering and labor built the High Aswan Dam in the 1960s (right). The Suez Crisis packed a powerful punch historically given that it was a relative blip on the screen at the time. Israel had easy enough success in the brief war prior to their withdrawal that it helped convince them to take more territory from Egypt eleven years later in the 1967 Six-Day War, that we’ll revisit in Chapter 19. Also, Western Europeans resolved to get partly out from under American control. I say partly because they still wanted an alliance and for the U.S. to foot the bill for big-ticket military spending. But Great Britain and France both developed their own nuclear bombs after Suez.

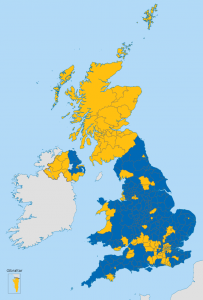

Europe as a whole moved toward its common Community (1957- ), culminating in the European Union (EU, 1992- ), realizing that uniting was their only hope to maintain power in the modern world. The U.S. and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Eden’s predecessor) advocated Western European integration after WWII foremost as a way to avoid regional conflicts like the two world wars, but Suez added the motivation of regional strength. Goods, services, workers, and people moved freely between EU member countries post-1992 to bolster economic strength, similar to the way Americans can move between states and are free to work and own property in different states. This is the system that’s on the ropes now because a vocal (and voting) minority of Britons came to resent immigrant workers from Eastern Europe in the 2010s (despite low unemployment), leading to their 2016 Brexit vote, when Britain exited the EU. Britain likely would’ve stayed in the EU if they could’ve sealed their borders but, obviously — as pointed out by German Chancellor Angela Merkel — that would’ve undermined one of the EU’s key features (that would be like Texas saying that it would like to remain in the U.S. as long as Californians can’t move there). Brexit could weaken Britain and Europe’s economies and motivate independence movements in Scotland and Northern Ireland, the districts of which mostly voted to remain in the EU (yellow, left).

Europe as a whole moved toward its common Community (1957- ), culminating in the European Union (EU, 1992- ), realizing that uniting was their only hope to maintain power in the modern world. The U.S. and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Eden’s predecessor) advocated Western European integration after WWII foremost as a way to avoid regional conflicts like the two world wars, but Suez added the motivation of regional strength. Goods, services, workers, and people moved freely between EU member countries post-1992 to bolster economic strength, similar to the way Americans can move between states and are free to work and own property in different states. This is the system that’s on the ropes now because a vocal (and voting) minority of Britons came to resent immigrant workers from Eastern Europe in the 2010s (despite low unemployment), leading to their 2016 Brexit vote, when Britain exited the EU. Britain likely would’ve stayed in the EU if they could’ve sealed their borders but, obviously — as pointed out by German Chancellor Angela Merkel — that would’ve undermined one of the EU’s key features (that would be like Texas saying that it would like to remain in the U.S. as long as Californians can’t move there). Brexit could weaken Britain and Europe’s economies and motivate independence movements in Scotland and Northern Ireland, the districts of which mostly voted to remain in the EU (yellow, left).

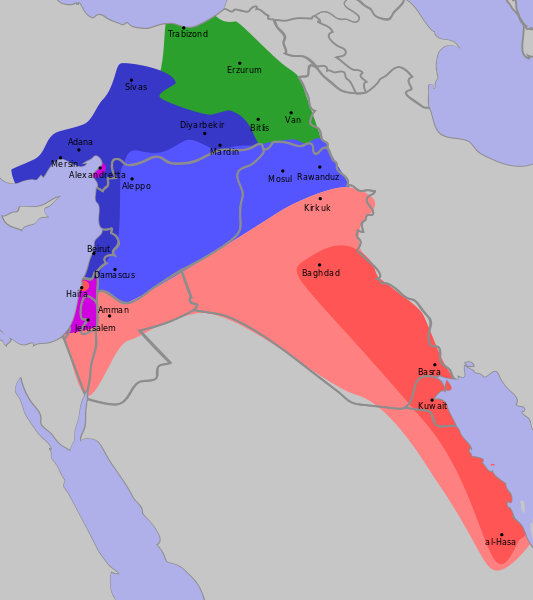

The Suez Crisis also helped re-ignite the Pan-Arab movement that traced back to World War I, when Arab countries that had been under Ottoman rule realized they’d been duped in their British alliance during the Arab Revolt. Really, they’d just been taken over by Britain and France. You may remember the Sykes-Picot Agreement from Chapter 6 on the Great War (right). The Suez Crisis fueled Arab Nationalism in the Middle East, whereby leaders like Nasser strove to get out from under Western domination. Saudi royalty was an exception because they profited from Western oil alliances. Western support for Israel added fuel to the fire. The British lost their allies in Jordan and Kuwait and their ambassador in Baghdad warned that, by colluding with Israel in the Suez Crisis, Britain had imperiled the lives of its Iraqi allies and the monarchy itself. Sure enough, Iraq’s monarchy was overthrown in a bloody coup in 1958, leading to Ba’athist rule.

Later, as part of this ongoing pan-Arab movement, newcomers like Muammar Gaddafi of Libya and Ba’athist Saddam Hussein of Iraq nationalized their oil fields, meaning that they wrested control away from Western oil companies. This was theft technically since the companies made the initial investments to get the oil flowing and owned the equipment and rights. But it was also theft of a bigger sort for developed countries to plunder Arab resources. Arab nationalism would’ve happened regardless of the Suez Crisis, but the crisis marked a renewed effort among those striving for more regional independence. As we’ll see in Chapter 19, Arab oil cartels soon followed, as did a series of wars against Western-backed Israel. Ike, meanwhile, reaffirmed America’s containment policy in the Middle East, specifically, with the 1957 Eisenhower Doctrine against communist expansion.

Nuclear World

The U.S. reasoned that their only option to defend themselves against the USSR was a big nuclear deterrent. Instead of ending the Cold War, Ike swelled the nuclear arsenal and went nowhere without the “nuclear football” — a special satchel with the Commander-in-chief’s codes to bomb the Soviet Union. It made the news on January 6 when some of those storming the U.S. Capitol vowed to lynch VP Mike Pence, who had the satchel with him.

Hydrogen bombs got bigger and bigger, with the USSR matching the U.S. step-for-step. By using traditional fission triggers (uranium or plutonium) to fuse hydrogen atoms, the “Supers” were mimicking, on a tiny scale, how the Sun fuses hydrogen and helium. The Earth’s magnetosphere shields it from the radioactivity of the solar wind, but astronauts have to protect themselves from the Sun’s radiation. Hydrogen bomb research revealed to physicists the Sun’s approximate lifespan of around 10 billion years (don’t worry, it’s in middle age).

The U.S. tested its biggest H-bombs in the Pacific but continued research on medium and small bombs at the Nevada Test Site north of Las Vegas (right) throughout the 1950s, sometimes accidentally dropping radioactive dust on nearby towns if weather forecasts proved incorrect and the wind blew in the wrong direction. They set up mock homes with mannequins and filmed the impact and used entrenched soldiers as guinea pigs from a few miles out. Soldiers wore goggles and underwent psychological tests as they walked toward ground zero. They radiated animals closer up, including dogs, goats, sheep, rats, and pigs wearing army clothing because pigs’ skin is similar to humans. The tests were an attraction in Las Vegas, where tourists could watch from a distance with sunglasses and feel the shock waves rattle the windows. It was fun for the whole family.

The U.S. tested its biggest H-bombs in the Pacific but continued research on medium and small bombs at the Nevada Test Site north of Las Vegas (right) throughout the 1950s, sometimes accidentally dropping radioactive dust on nearby towns if weather forecasts proved incorrect and the wind blew in the wrong direction. They set up mock homes with mannequins and filmed the impact and used entrenched soldiers as guinea pigs from a few miles out. Soldiers wore goggles and underwent psychological tests as they walked toward ground zero. They radiated animals closer up, including dogs, goats, sheep, rats, and pigs wearing army clothing because pigs’ skin is similar to humans. The tests were an attraction in Las Vegas, where tourists could watch from a distance with sunglasses and feel the shock waves rattle the windows. It was fun for the whole family.

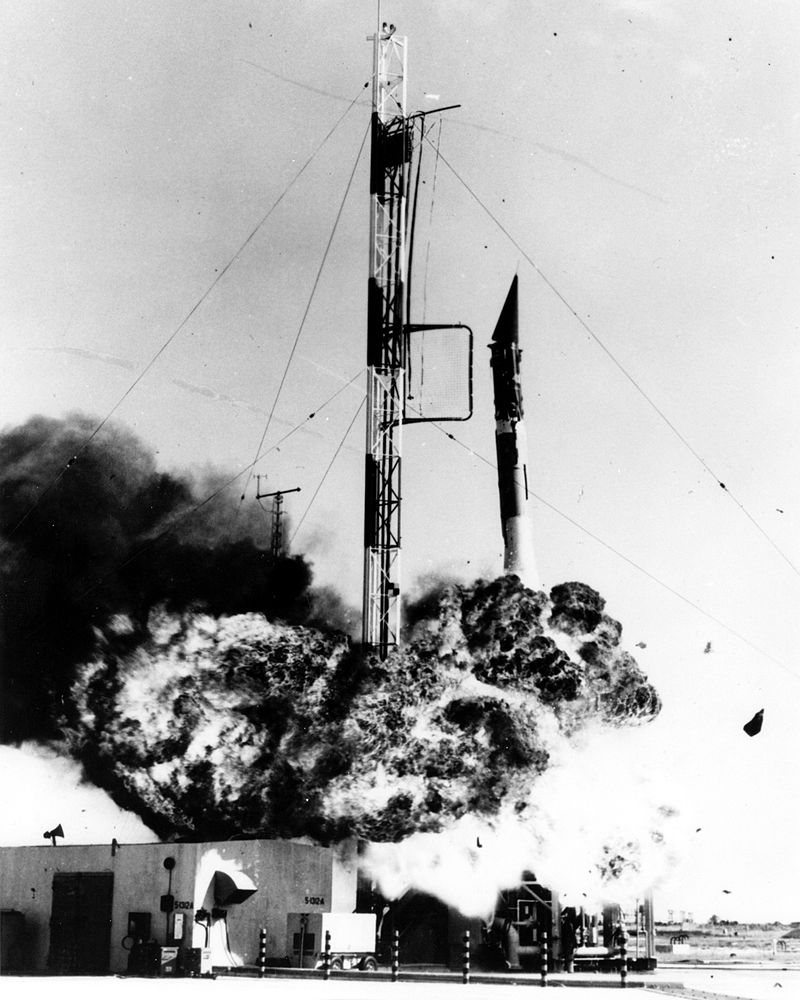

Rocket research paralleled bomb research. As you’ll remember, the U.S. recruited the prize German at the end of WWII, Wernher von Braun, but Soviets had their own homegrown superstar in Sergei Korolev. As a young man, Von Braun idolized American Robert Goddard, the father of liquid-fueled rocketry. At first, Eisenhower kept him on ice at Fort Bliss in El Paso, worried that his Nazi/SS roots would endanger public relations. The American rocket programs — Army’s Redstone, Navy’s Vanguard, and Air Force’s Atlas — lagged behind the Soviets, as symbolized by the Soviets’ launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957. However, for Ike and the military, Sputnik’s launch and orbit weren’t nearly as important as what happened weeks earlier, when a Korolev missile delivered a dummy warhead on target from Moscow to the Kamchatka Peninsula on the USSR’s Pacific coast. As you can see from the map below, that effectively put them in range of the United States. Russia is just 56 miles from Alaska but neither Siberia (eastern Russia) nor Alaska are populated enough to make them meaningful targets. Meanwhile, America’s Vanguard rockets struggled to get off the ground, with the first exploding on lift-off and the second shortly after. Ike brought Von Braun off the bench and started NASA and numerous offshoots, as we’ll see in the next chapter. One connection between pure science and the arms race was that any rocket strong enough to carry a 5-ton nuclear warhead could carry a capsule instead and propel it to the 17.2k m.p.h. necessary to stay in orbit. Rockets require tremendous thrust to escape Earth’s gravity and engineers initially favored hydrogen liquid propellant, not gas-turbine jet fuel, to trigger the necessary launchpad explosion. But multi-stage liquid-fueled rockets propelled capsules to the Moon and planets, aided by gravity assist “slingshot” maneuvers. The Mariner Program (1962-73) launched unmanned fly-by and orbiter craft to the inner planets (Venus, Mars, and Mercury) — an astounding feat considering that less than sixty years had transpired since the Wright Brothers. The multi-stage idea traced to Russian Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), a pioneer of astronautics who didn’t live to see space travel. Despite Tsiolkovsky and Korolev’s reputations, Von Braun, channeling his inner Elon Musk, hoped that siding with the U.S. after WWII instead of the USSR afforded him his best chance at a manned mission to Mars (see his 1952 book The Mars Project).

Before missiles could be relied on to carry bombs, the Strategic Air Command kept a fleet of bomb-toting B-52 Stratofortresses and B-36 Peacemakers aloft so that they could drop their payloads on the USSR if the Soviets struck first. These “Buffs” were prepared 24/7 to reduce the USSR to “a smoking, radioactive ruin within two hours,” in the words of one officer. Shot down crews could arm a “dead man’s switch” (SWESS) to detonate the bomb once the plane dropped below a certain altitude. Air Force General Curtis Lemay (Chapters 12 & 13) led SAC from 1948 to 1957.

BARKSDALE AIR FORCE BASE, La., Munitions on Display Show the Full Capabilities of the B-52 Stratofortress, U.S. Air Force Photo by Tech. Sgt. Robert J. Horstman

Luckily, SAC didn’t reduce the U.S. or its allies to ruins by accident. Accidents (aka Broken Arrows) turned out to be almost as big of a threat as the Soviet Union, especially since fire could melt the solder on the circuit boards running a bomb’s safety switches. In 1950, an Air Force Convair bomber on a mission from Fairbanks to Fort Worth dropped a still undiscovered atomic bomb into the Pacific before crash-landing in British Columbia. In 1958, an Air Force B-47 accidentally dropped an atomic bomb on a farm outside Mars Bluff, South Carolina, but it didn’t have the plutonium core inserted in it and caused no radioactive release. In 1961, a B-52 carrying two 24-megaton plutonium H-bombs spun out of control and broke apart over Goldsboro, North Carolina because of a fuel leak. As the fuselage fell to Earth, centrifugal forces in the cockpit pulled the lanyard that released its bombs. One of the bombs went through all of its arming steps to detonate and, when it hit the ground, the firing signal triggered. Of the four safety switch interlocks on the device, two failed, one didn’t activate, and the fourth stayed locked in place, preventing the USAF from obliterating a large portion of the Mid-Atlantic. Depending on wind, the Goldsboro accident could have blanketed the capital in Washington, among other places, with radioactive fallout, with each bomb ~ 250x more powerful than than those used in Japan in 1945. Had the device with two arm/safe switches on arm gone off, it would’ve also detonated the second one that came down nearby in a parachute. In 1966, a B-52 collided with a tanker during a mid-air refueling over Palomares, Spain and four hydrogen bombs fell to Earth in parachutes. Luckily, the bombs didn’t explode on impact even though the conventional explosives on the outer shell detonated. The three that hit the ground released small amounts of radiation, but the one that fell in the Mediterranean didn’t and the U.S. found it two months later, winning a race with the Soviets. They had less luck in Greenland after a B-52 crashed there in 1968 toting four H-bombs after a cabin fire forced the crew to eject (Thule Air Base Crash). Documents released under the Freedom of Information Act revealed that Air Force and Danish officials found three but the secondary stage of a fourth bomb 100x more powerful than the Hiroshima A-bomb is still buried somewhere under the ice of North Star Bay or scattered into component parts. There’s another subterranean U.S. missile launch base in northern Greenland, Camp Century, that’s leaking radiation and PCBs that we’ll have to deal with later this century if the ice melts. The Museum of Nuclear Science & History in Albuquerque, New Mexico has some of the dented fallen bombs on display. Hydrogen bombs are detonated above ground zero to maximize their impact radius, as were the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

With the advent of missiles, the U.S. and Canada bunkered their own launching system headquarters deep inside Cheyenne Mountain, Colorado with NORAD, standing for North American Aerospace Defense Command (despite the improper acronym). This nerve center could retaliate if a pre-emptive Soviet strike wiped out surface defense infrastructure. That was key to deterrence or MAD: mutually assured destruction. NORAD was earthquake proof and maintained a month’s worth of food and water, along with its own electrical generator. As far as NORAD’s capacity to wage war after most of the country was wiped out, the “brain would function long after the body was dead.” They also constructed bunkers for congressmen, under Greenbrier Resort in West Virginia, and under the White House. More underground bases for the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FEMA were built at Mt. Pony and Mt. Weather, near Washington. Greenbrier had full-sized replicas of the House and Senate chambers.

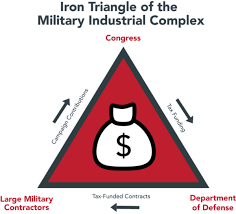

As we saw in World Wars I and II, the government doesn’t make its own weapons in a factory; they hire private contractors. The same politicians who escalated the arms race had defense contractors pushing them to keep the government on a high military budget, even if, as suggested in the previous chapter, that was as much a result as a cause of the spending. It would’ve happened either way, in other words, regardless of lobbying. Still, none other than Eisenhower himself feared the contractor’s influence. He discussed the potential conflict of interest in his 1961 Farewell Address, warning that lobbyists seek influence in policy-making and coining the phrase military-industrial complex to describe the iron triangle of defense contractors, politicians, and the Pentagon. To wit: the same contractors that stand to profit from war (or the threat thereof) are making “campaign donations” to the politicians in charge of making war, creating a potential conflict of interest. Contractors had some impact on American involvement in Vietnam (e.g., Dow Chemical & Monsanto made Agent Orange) and were among those pushing George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003. In Iraq’s case, key contracting lobbyists were construction and energy companies that stood to rebuild Iraq. While the military-industrial complex is prone to corruption, and wary citizens should watch contractors like a hawk, it’s not an inherently bad thing for the government to subcontract weapons manufacturing. After all, a couple of chapters ago we were crediting the “arsenal of democracy” with winning World War II. That was just earlier terminology for the military-industrial complex. Likewise, abolition didn’t win out over slavery in the Civil War because of human moral evolution, but rather because the industrial might of the North wore down the Confederacy.

As we saw in World Wars I and II, the government doesn’t make its own weapons in a factory; they hire private contractors. The same politicians who escalated the arms race had defense contractors pushing them to keep the government on a high military budget, even if, as suggested in the previous chapter, that was as much a result as a cause of the spending. It would’ve happened either way, in other words, regardless of lobbying. Still, none other than Eisenhower himself feared the contractor’s influence. He discussed the potential conflict of interest in his 1961 Farewell Address, warning that lobbyists seek influence in policy-making and coining the phrase military-industrial complex to describe the iron triangle of defense contractors, politicians, and the Pentagon. To wit: the same contractors that stand to profit from war (or the threat thereof) are making “campaign donations” to the politicians in charge of making war, creating a potential conflict of interest. Contractors had some impact on American involvement in Vietnam (e.g., Dow Chemical & Monsanto made Agent Orange) and were among those pushing George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003. In Iraq’s case, key contracting lobbyists were construction and energy companies that stood to rebuild Iraq. While the military-industrial complex is prone to corruption, and wary citizens should watch contractors like a hawk, it’s not an inherently bad thing for the government to subcontract weapons manufacturing. After all, a couple of chapters ago we were crediting the “arsenal of democracy” with winning World War II. That was just earlier terminology for the military-industrial complex. Likewise, abolition didn’t win out over slavery in the Civil War because of human moral evolution, but rather because the industrial might of the North wore down the Confederacy.

Toward the end of his presidency, Eisenhower wanted to defuse the Cold War. He hoped to swap materials with the Soviets for nuclear power rather than weapons (Atoms-for-Peace), and he was the first president to discuss arms reduction (of course, he was the first to preside over such a large arsenal). Ike was willing to submit to nearly whatever on-site inspection terms the new Soviet General Secretary proposed to mutually reduce nuclear stockpiles.

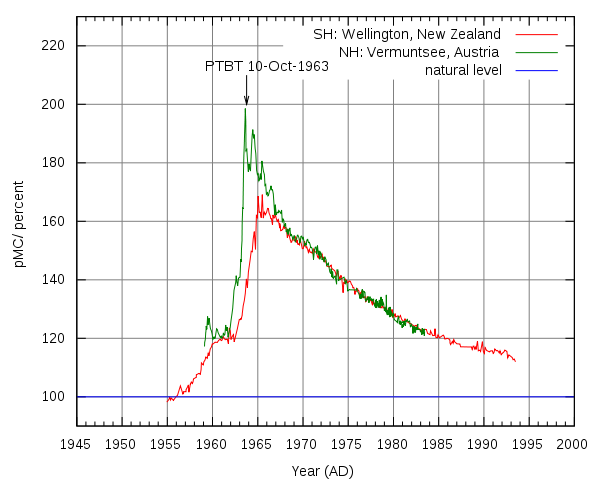

Stalin’s ultimate successor Nikita Khrushchev came to Camp David, a presidential retreat in Maryland named after Ike’s son, and agreed on the basic framework of an above-ground test ban that kicked in by 1963. Prior to the “partial” or “limited” above-ground test ban, the U.S. and Soviets were bombing themselves on a regular basis, albeit in unpopulated areas. Khrushchev famously (and wrongly) said, “We will bury you,” in reference to communism’s impending victory over capitalism, but he and Ike were former allies from WWII and they got along reasonably well given the circumstances (and looked similar). They also agreed to reduce (small-scale) tactical nuclear weapons, the sort designed for battlefield use, though the U.S. maintains tactical nukes along the Korean border to this day, and Russia has them as well.

U-2 Incident

Two events foiled Eisenhower’s peace initiative: the downing of an American spy plane over the USSR and a communist revolution in Cuba. With Ike about to meet Khrushchev in Paris for another summit and then visit Moscow a month later, the president was dubious about the CIA flying spy missions over the Soviet Union. Khrushchev was excited too and the Soviets were busy scrubbing down Moscow’s streets and buildings and preparing for a first-ever American presidential visit. Khrushchev had been to the U.S. and the Soviets were building new hotels and even a golf course for Eisenhower’s follow-up trip. In February, Ike voiced concern that a mishap could tarnish his integrity in Soviet eyes and prophetically feared a downed plane being “put on display in Moscow.” However, Ike only expressly forbade any flights after May 1st. The CIA wanted to collect information that he could use at the Paris Summit and scheduled a mission for May Day (May 1st), the Soviet equivalent of the American Fourth of July. April 30th might’ve been a better move.

U-2 Reconnaissance Aircraft in Flight, Photo by Master Sgt. Rose Reynolds, Date Unknown, Beale Air Force Base, California (CA)

Some background helps to explain what happened next. After the Soviets rejected Eisenhower’s Open Skies offer, whereby each side would’ve granted open access to view each other’s military installations, the U.S. searched for better reconnaissance. During Truman’s administration, they’d started a top-secret balloon program called Project Mogul (1947-49) to alert them to what the Soviets were exploding through high-altitude remote sound detection, but it didn’t pan out — though one balloon inadvertently sparked UFO conspiracy theories when it crash-landed outside Roswell, New Mexico in 1947. In 1955, the CIA developed the high-altitude U-2 reconnaissance plane at Lockheed’s Skunk Works and their then-secret, high-security Area 51 base in Groom Lake, Nevada. The 110-ft. wing-span U-2 was basically an unarmed tin-can fuselage with a Pratt & Whitney turbojet engine and high-powered telephoto lens camera pointing at the ground.

The CIA mistakenly thought the U-2 flew high enough at 70k feet (13 miles) to be outside the range of Soviet radar and SAMs (surface-to-air missiles) – that was the point of its unique light-weight design. American pilots could take off from either Turkey or Pakistan (one source of America’s longstanding uneasy alliance) and take pictures of sensitive military sites, especially nuclear missile bases. A U-2 “Dragon Lady” took pictures over a base in Kazakhstan in 1957 showing that the Soviets had built an inter-continental ballistic missile, aka ICBM. That intensified the arms race, as building better long-range missiles became America’s top priority. The same year, the U.S. developed the first of its Atlas Rocket series that carried nuclear warheads 100x more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Per normal protocol, on May 1st, 1960 the CIA instructed U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers to commit suicide with a prick of shellfish poison to avoid capture if anything went wrong, but he also had a parachute in case he went down over friendly territory. The poison hung from his neck hidden in a silver dollar like a “good luck charm,” as he later put it. Powers would be the first U-2 pilot to fly all the way over the Soviet Union and land in Scandinavia, hoping to take pictures of a new base north of Moscow. Planners didn’t anticipate a scenario whereby a Soviet missile would get near enough Powers’ plane to damage it and knock it out of the sky without destroying it. Powers was also tempting fate by flying lower than he was supposed to.

The Soviets knew about the U-2 all along but allowed the flights to continue because they didn’t want the U.S. to know that they knew, or for the Americans to realize how strong their radar was. They had the equipment in place to shoot down a U-2 when they developed the S-75 Dvina (or SA-2 Guideline) surface-to-air missile in 1957. Alas, they couldn’t tolerate Powers buzzing Moscow during their May Day parade and shot him down with a SAM over Sverdlovsk, in the Ural Mountains. For good measure, they sent a jet up to ram him but it missed. The missile blast blew both wings off the U-2 but the fuselage didn’t disintegrate the way planners had promised Ike. In the heat of the moment, with “the nose pointed at the sky,” Powers couldn’t get the self-destruction mechanism activated for the plane and also elected to not self-destruct himself with the poison. He ejected and parachuted into a throng of ecstatic Russian farmers, reconsidering suicide as he plunged into the “tortures and unknown horrors” that awaited him.

Khrushchev cabled Eisenhower stating that they had an American plane burned beyond recognition. Ike assured him it was just a weather plane (with some sources scapegoating NASA), but then Khrushchev revealed they had a captured pilot “alive and kicking” and retrieved the camera and film off the plane, and that the KGB had always known about the U-2’s anyway. There’s no footage indicating how maroon, exactly, Eisenhower’s bald head got as he heard this from the translator. The Soviets displayed what was left of the U-2 in Moscow’s Gorky Park and imprisoned Powers for 21 months. They didn’t torture him physically but subjected him to intense “psychological pressure,” including sleep deprivation, bright spotlights, death threats, and questioning, but allowed his wife one conjugal visit.

As chronicled in the Coen Brothers’ and Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies (2015), America swapped Powers for Soviet spy Rudolf Abel, but the U-2 Incident ruined Ike’s hopes of ending his second term by winding down the Cold War. Nikita Khrushchev was angry at the Paris Summit and demanded that Ike repudiate the flyovers, which he refused to do. An apocryphal tale and fake photo spread showing Khrushchev banging his shoe against the podium at the United Nations. At the very least, he made belligerent speeches about the U.S. at the U.N. Any goodwill engendered from Khrushchev’s visit to America — where he’d playfully poked men’s beer bellies, visited Iowa farms, spoken at a Hollywood luncheon, and threw a small tantrum when his security wouldn’t let him visit Disneyland — evaporated, and the Cold War raged on. Ike never visited the Soviet Union. Burnt out from fighting WWII as Supreme Allied Commander and the Cold War as NATO Commander and two-term president — and having endured a heart attack, stroke, and intestinal surgery — Ike basically checked out after cancellation of the Paris summit, losing interest in daily affairs and playing golf in the last months of his presidency, half-joking that he’d rather someone “shoot him in the head” than have to deal with it.

To avoid such incidents in the future, the U.S. stepped up its research on drones (unmanned aircraft) that became prominent during the War on Terror in the early 21st century. After brief experiments with space spies in the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, unmanned satellites mostly superseded the need for U-2’s, though they returned to the news in 2023 when they scoped out Chinese spy balloons over North America. The CIA and USAF, respectively, also developed planes that could fly higher and faster than the U-2 with the titanium-clad A-12 (Project Oxcart) and Mach 3+ SR-71 Blackbird (below), both also developed by Lockheed’s Skunk Works and tested at Area 51 (Groom Lake). Later they used Area 51 to advance yet stealthier aircraft like the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk fighter and Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit Bomber that showed less radar signatures because of their shapes and radar-absorbing skins.

SR-71B Trainer With Second Cockpit For Instructor Over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, 1994, Photo Judson Brohmer, USAF

As for Gary Powers, Congress exonerated him in 1962, he test-flew U-2’s for Lockheed and later piloted a traffic report helicopter for a Los Angeles TV station. He died on the job in 1977 when his helicopter ran out of gas in midair because of a faulty fuel gauge. In 2012, the Air Force awarded Powers a posthumous Silver Star Medal for maintaining loyalty during captivity.

Cuban Revolution

Soviet relations went awry anyway because of events closer to home. America hoped to contain communism anywhere and everywhere starting in 1950 with NSC-68 (Chapter 13). In 1959, communist dictator Fidel Castro took over Cuba just 90 miles off the Florida coast. The U.S. had more or less run Cuba after the Spanish-American War of 1898 but gradually ceded qualified autonomy by the 1930s, when Cuba was allowed to run their government as long as they didn’t do anything contrary to U.S. interests.

In the 1930s and again after 1952, America carried on a lucrative trade with dictator Fulgencio Batista but he was unpopular with many Cubans. The Italian-American Mafia controlled the capital of Havana, on the northern coast across from Florida. Gangsters like Lucky Luciano forged Cuban relations in the 1920s smuggling rum during Prohibition and eventually moved there to escape American law enforcement. Batista used the Mafia to skim profits from the national lottery, along with running gambling, drug, and prostitution rackets. The U.S. government looked the other way in return for Mafiosi helping the Navy engineer its Sicily Invasion during WWII. Like Las Vegas (but unlike Chicago or New York), criminals ran Havana after the war, and it was a mainstream tourist destination for sun-worshipping Americans. Stars like Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole entertained gangsters and tourists alike. Cuba wasn’t so much a Banana Republic as a Bordello Republic. American officials finally had Luciano deported when they realized that Havana was a conduit for heroin from Marseilles, France into New Orleans, Tampa, and Miami.

Poor Cubans resented criminals plundering their country, be they Cuban or American. They were exposed to and controlled by the worst face of capitalism. The exorbitant Hotel Habana Riviera, built on the backs of Cubans for Lucky Luciano’s lieutenant Meyer Lansky, symbolized the government’s misallocation of resources. The people were angry and fed up, as expressed later in the pro-Castro propaganda film I Am Cuba (1964) that was banned in both the U.S. and USSR but admired by directors Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese.

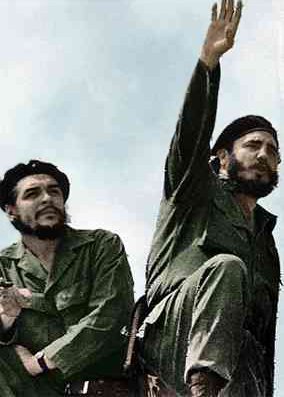

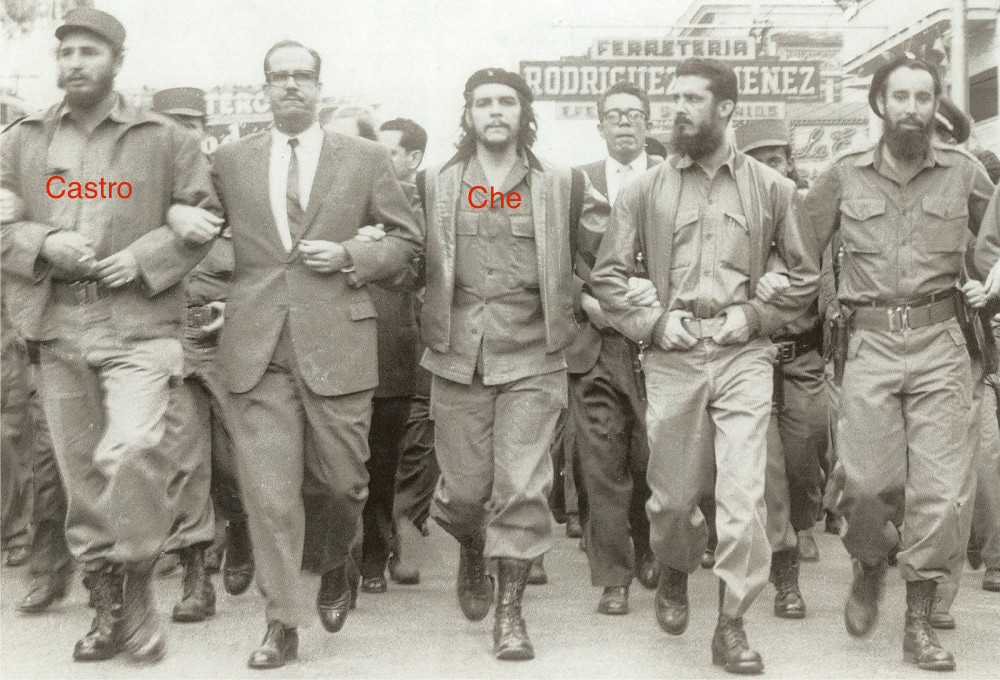

The Batista regime jailed rebel lawyer Fidel Castro in 1953, but when released he led another rebellion. The Mafia covered their bases, running guns to Castro in case he won while still working with Batista. The U.S. cut off support for Batista in 1958 when his government’s torture and execution of rebels got out of hand and eventually, in a final act of kleptocracy, he fled the country for the Dominican Republic, then Spain, with $300 million, draining the government’s treasury. Working out of bases in the Sierra Maestra Mountains of southeastern Cuba, revolutionaries including Castro’s brother Raul and Argentine doctor Ernesto “Che” Guevara fought their way toward Havana and took over the capital as Batista fled. Theirs was more of a middle-class rebellion than the peasant uprising associated with communist revolutions in Asia.

At first, optimists hoped for democratic socialism and Castro was popular among many Americans. In this interview with American television host Ed Sullivan (1.11.59), on the same show that had hosted Elvis Presley and, five years later, the Beatles, Castro promised that Batista’s will be the last ever dictatorship in Cuba, that there would be upcoming elections, and expresses his hopes for friendship with the U.S. Castro denounced Marxism and promised “representative government, social justice, and a well-planned economy.” However, the democratic part of the equation evaporated quickly and Castro and Che established a Marxist dictatorship. As finance minister, Guevara signed currency with just his first name. Their betrayal of representative government alienated many fellow fighters in the Segundo Frente Nacional de Escambray or SFNE (Second National Front of the Escambray [central mountains]), including Americans like El Yanqui Comandante (Yankee Commander) William Morgan, and many democratic socialists abandoned the revolution.

Most of the Mafia Dons cut their losses and fled, leaving behind assets and real estate. Castro took control of most private property, starting with his mother’s farm just to set an example. The regime executed or imprisoned its opponents while others escaped to Florida. Crime dried up and Cuba’s poor gained access to education, clean water, and modest healthcare. But Cubans had no more political freedom than they’d enjoyed under Batista.

Castro had no choice but to attempt a friendly relationship with the U.S. government given its size and proximity, but Eisenhower wasn’t happy with this dramatic transgression of Containment Doctrine. It flew directly in the face of America’s entire foreign policy for the prior fifteen years. As U.S. corporations lost their land, Eisenhower’s administration cut off American sugar imports and, via the CIA, authorized the Mafia to kill Castro. When Castro flew to D.C., Eisenhower waited until he was moments from the White House then took off to play golf, leaving VP Richard Nixon instructions to tell Castro to “go to Hell,” the same three-word message Zachary Taylor sent Santa Anna in the Mexican War in 1848. Ike’s anger was understandable given Castro’s betrayal of democratic socialism, but giving Castro the cold shoulder threw him onto Khrushchev’s lap, who was more than willing to aid the Cubans and establish a Soviet foothold near the U.S.

Strategically, the proximity of intermediate nuclear missiles barely mattered by the late 1950s. By 1960, each side was well on its way to developing reliable, long-range ICBMs. Consequently, it wasn’t imperative for the Soviets to build launch sites near enough America to deliver intermediate-range missiles. Politically, though, the spread of communism so close to U.S. shores was an embarrassment, worsened by Cuba’s alliance with the USSR. By the time Eisenhower left office, he had plans on the table to use the CIA to invade Cuba and overthrow Castro. A similar plan had worked well in Guatemala in 1954, so why not in Cuba? Presumably, most of the Cuban people hated Castro and loved the U.S., so as soon as a small force hit the beach everyone would rally around it. At least that was the plan. But Castro learned from the Guatemalan overthrow, too, and resolved to not be separated from his army as readily as Jacobo Árbenz had. In fact, he’d lead his own army so they’d be ready when the Americans came. The wheels were in motion for a Cuban invasion when Ike’s successor, John F. Kennedy (JFK), took office in 1961.

Kennedy As Cold Warrior

JFK continued with the same containment strategy as his predecessors. Ignoring Ike’s warning about the military-industrial complex, he even set up a commission to help expedite relations between corporate contractors and the Pentagon. Military spending boomed. Kennedy put intermediate-range missiles in Italy and Turkey, within range of Moscow and much of the USSR. Because these Jupiter Missiles were immobile, above-ground, and took a long time to launch, they were arguably more of a conspicuous first-strike target than a deterrent to prevent war. Tennessee Senator Al Gore, Sr. warned JFK’s Secretary of State Dean Rusk that they’d likely provoke the Soviets to try and get their own missiles within range of America. The U.S. also put missiles in Okinawa (off Japan) aimed at China, though that only came to light in 2012.

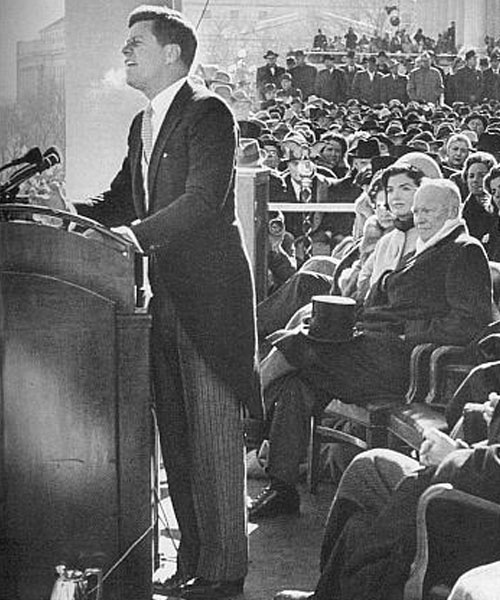

Being younger than Ike with less military pedigree (he was a PT boat commander in the Pacific during WWII), JFK was anxious to prove his mettle against communism. In his inaugural address, he said, “let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we will pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to ensure the survival and success of liberty.” He got an early test when the Soviets built a wall through Berlin to stop emigration to the western (free) sector and tried to compel the U.S., British, and French to withdraw from West Berlin. They refused, but the standoff known as the Berlin Crisis of 1961 brought the Cold War factions to the brink of conflict, with missile silos on alert and soldiers and tanks lined up hundreds of yards from each other.

Communists put up barbed wire overnight, then built a brick wall that they’d transformed into higher concrete walls by 1989. Two years later, JFK delivered a resilient speech in Berlin, in the shadow of the famous Wall built in 1961 to keep East Berliners from escaping, of whom 20% had already escaped to West Germany via West Berlin. Kennedy famously concluded with “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a Berliner), underscoring America’s NATO commitment to defending Europe. An urban legend developed, perpetuated by German cartoonists, the BBC, and New York Times, that, because of the popularity of a pastry called the Berliner, he was also saying, “I am a jelly-filled donut!” Really, his speechwriters used ein correctly as an indefinite article since he was speaking of his Berlin residency in a figurative sense. In any event, the crowd roared in approval, knowing what he meant. President Ronald Reagan made a similar speech at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate in 1987, telling then-Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, “Tear down this wall!”

Internal documents later showed that JFK considered a first-strike nuclear attack against the Soviets in retaliation for construction of the Berlin Wall, which would’ve been a wildly incommensurate response. But the same documents also show that his primary concern was finding ways around the Berlin conflict that avoided war. It was better to underscore America’s NATO commitment to the rest of Europe than start WWIII over a concrete barrier separating East and West Berlin. The Soviets, meanwhile, resumed above-ground tests and exploded the gigantic 58-megaton hydrogen bomb Tsar Bomba (yields).

JFK also tried to modernize the military, as do most presidents with varying luck, reinvigorating Special Forces like the Army Rangers and Navy Seals. He did so in anticipation of challenging, small-scale operations in Third-World countries that he called Flexible Response and thought would dominate modern warfare more than big, traditional battles. Vietnam became an early test case for Kennedy’s idea as he sent in Green Berets to train South Vietnamese allies. He also started the Peace Corps as a way for the U.S. to win people over in emerging countries and dissuade them from favoring communism.

Bay of Pigs

Cuba was an excellent opportunity for Kennedy to accomplish something Ike hadn’t gotten around to when he left office. He authorized the already planned CIA invasion of Playa Girón, a southern harbor known to Americans as the “Bay of Pigs,” though they altered Ike’s original plan in some key ways that backfired. First, the CIA feigned an attack on the west coast to draw off the main troops led by Che Guevara, then they struck from the south. Kennedy minimized air support (8 Douglas A-26 Invaders) because he didn’t want too high profile of an invasion to incur a response by the Soviets in Berlin, and later air support missed their rendezvous because of a mix-up over time zones. By the time the CIA-trained, Cuban exile troops arrived, the secret was out. Some ships sank on coral reefs and backup paratroopers landed in the wrong spot. The mission’s two assumptions – that the CIA could handle it on their own with a small handful of rebels and no assistance from the military, and that the Cuban people would rally around the rebel force – both proved false. Instead, Castro’s forces surrounded the invaders and no one rallied behind the “Yankees,” either because they were loyal to Castro or scared of him. Che Guevara saw firsthand the CIA overthrow Árbenz’ government in Guatemala, and he and Castro learned from that experience how they would do things differently, not allowing the Yankees to drive a wedge between their military and government.

JFK mistakenly privileged CIA intel over military advisers like Curtis Lemay who warned that the plan wouldn’t work. The Bay of Pigs Invasion was a fiasco from the U.S. perspective, resulting in the death or capture of all the forces in three days and getting Kennedy’s presidency off to a rough start just two months in. The U.S. was also caught red-handed lying about the plot at the United Nations. The U.S. swapped cash and medicine for the survivors and Che sent a thank you note to Kennedy for solidifying a shaky revolution. Off the record, JFK wondered how a consensus of “experts” led him astray, but rather than shirk responsibility he stepped up publicly and accepted full blame. The public’s response? His approval rating soared to 83%. If there was any upside to the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy learned to not trust his advisers and that helped prepare him for the next Cuban crisis in 1962, when he wisely overrode nearly everyone around him. Ike met with JFK at Camp David to lecture him on the importance of hearing out a wide range of opinions, including skeptics.

Operation Mongoose

Operation Mongoose

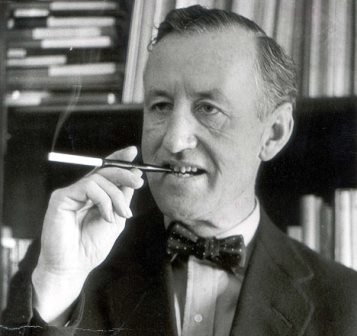

In the meantime, the CIA’s Operation Mongoose continued to run strategic missions over Cuba, bombing railroads and factories, poisoning sugar, and engaging in other petty forms of propaganda and psychological warfare, all the while trying to kill Castro as the Mafia did the same. James Bond creator Ian Fleming (right) served as a consultant to the CIA, just as he had with its predecessor, the Army OSS. American troops at Guantánamo Naval Base (aka “Gitmo”) tried to goad the Cubans into attacking the base by firing on fishermen, hoping for a pretext for a major invasion. American troops amassed in Texas and Florida preparing for such an invasion. There’s much lore about how the CIA tried to kill Castro, including putting toxic thallium (the “poisoner’s poison”) in his socks and Fleming’s idea to get at him through his beard. Mongoose became a pet project of Bobby Kennedy, John’s attorney general brother, who thought that Castro’s death was America’s top priority and met weekly with CIA planners. There was even an unrealized plan to frame the Cubans for any potential tragedies in the American space program. Right-wing mercenaries also threatened Cuba from bases in Latin America and the CIA smuggled 14k Cuban children to Miami in Operation Peter Pan.

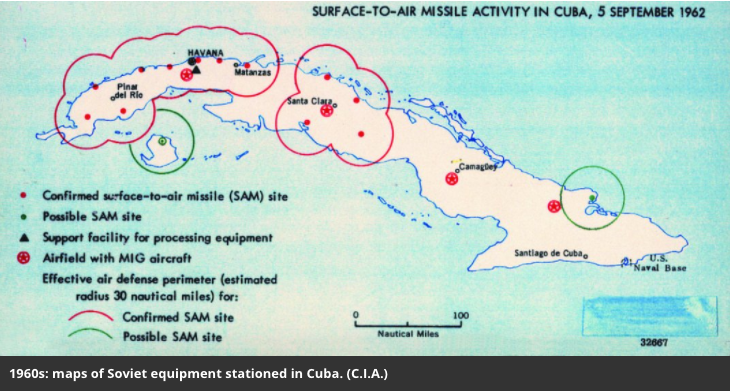

Mongoose was the biggest CIA operation to date but its failure bolstered Castro’s popularity and it strengthened the Soviets’ argument that the only way to protect Cuba’s sovereignty was to arm the island with missiles. The Soviets also wanted to influence communism throughout Latin America and prove to China that they were the leading force for communism. Che engineered an alliance with the USSR culminating in a November 1961 agreement for the Soviets to send 43k troops (under their command), medium-range bombers, and intermediate-range nuclear-tipped missiles. The Soviets wanted intermediate-range missiles in Cuba to counter America’s Thor Missiles in England and Jupiters in Italy and Turkey. Castro thought they should be open about the arrangement, but Khrushchev thought it would be wiser to sneak them in.

Memorial Service March for Victims of the La Coubre Explosion, Havana, 1960, Museo Che Guevara (Centro de Estudios Che Guevara en La Habana, Cuba)

‘Eyeball to Eyeball:’ The Cuban Missile Crisis

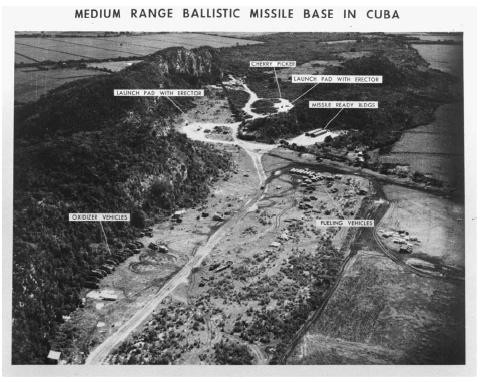

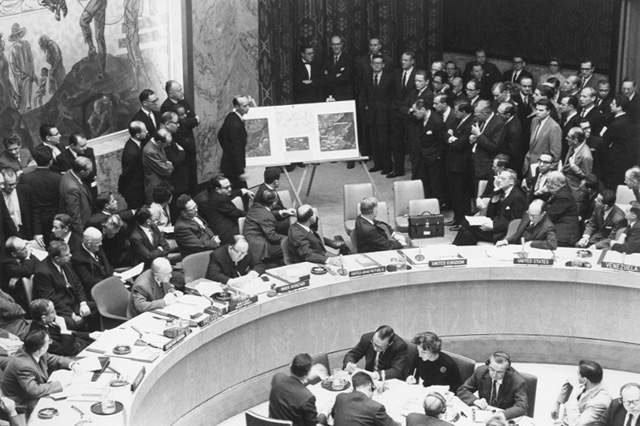

Despite the setback at the Bay of the Pigs, Kennedy was focused on the Berlin Crisis, convinced that the Soviets would make their next move in Europe. But he took heed when congressional Republicans urged him to monitor Cuba and resume U-2 flyovers there. In 1962, American spy planes confirmed their fears that the Soviets were constructing launch pads in Cuba and building a base. Low-flying Goddard jets took photos that confirmed the U-2 high-altitude photos in greater detail. What followed was the most harrowing event of modern history, the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The U.S. had a mole in the Kremlin, Oleg Penkovsky, whose Menshevik father was killed by the Bolsheviks. He told them about the SS-4 missiles in Cuba that could reach the southeastern U.S., and that longer-range SS-5’s were on the way that could reach the entire Lower 48. The missiles the U.S. knew about from the photos were the thousand-mile SS-4’s aimed at roughly 30-80 million Americans, depending on how one measures range and accuracy (the total American population was then ~ 180 million). The U.S. felt threatened by the missiles in the same way that Soviets did by the Thors and Jupiters. Indeed, Khrushchev later said he was “giving them a little bit of their own medicine.” Kennedy huddled over the photos with his “ExComm” team (Executive Committee on the National Security Council) on October 16, 1962. The following exchange would defy belief except that a tape recorder was running (transcript). JFK obviously knew about the Turkish missiles at one point because he’d leaked it to the press to mollify Republican criticism of him being weak on communism. So it’s difficult to tell here whether Kennedy was temporarily clueless or just being sarcastic:

JFK: “Why does he put these in there, though? … It’s just as if we suddenly began to put a major number of MRBMs [medium-range ballistic missiles] in Turkey. Now that’d be goddamned dangerous, I would think.”

McGeorge Bundy (National Security Adviser): “Well we did it, Mr. President.”