“Those who own the country ought to govern it.” — John Jay, First Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

Looking back, we get a false sense of inevitability about the success of the early United States. Looking forward from 1781, there was less optimism about its prospects and the early U.S. nearly came unraveled. The Revolution was harder than most people today realize. Soldiering was dangerous, thankless and painful, civilians suffered economically because of the long blockade, and politicians put their lives on the line organizing the revolt. Even after the revolt succeeded, a group of officers unhappy with back pay and lack of pension threatened a coup against Continental Congress called the Newburgh Conspiracy that Washington defused with a pleaful speech.

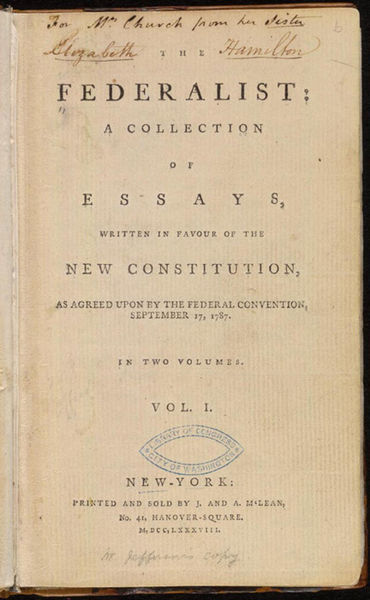

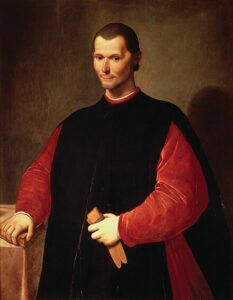

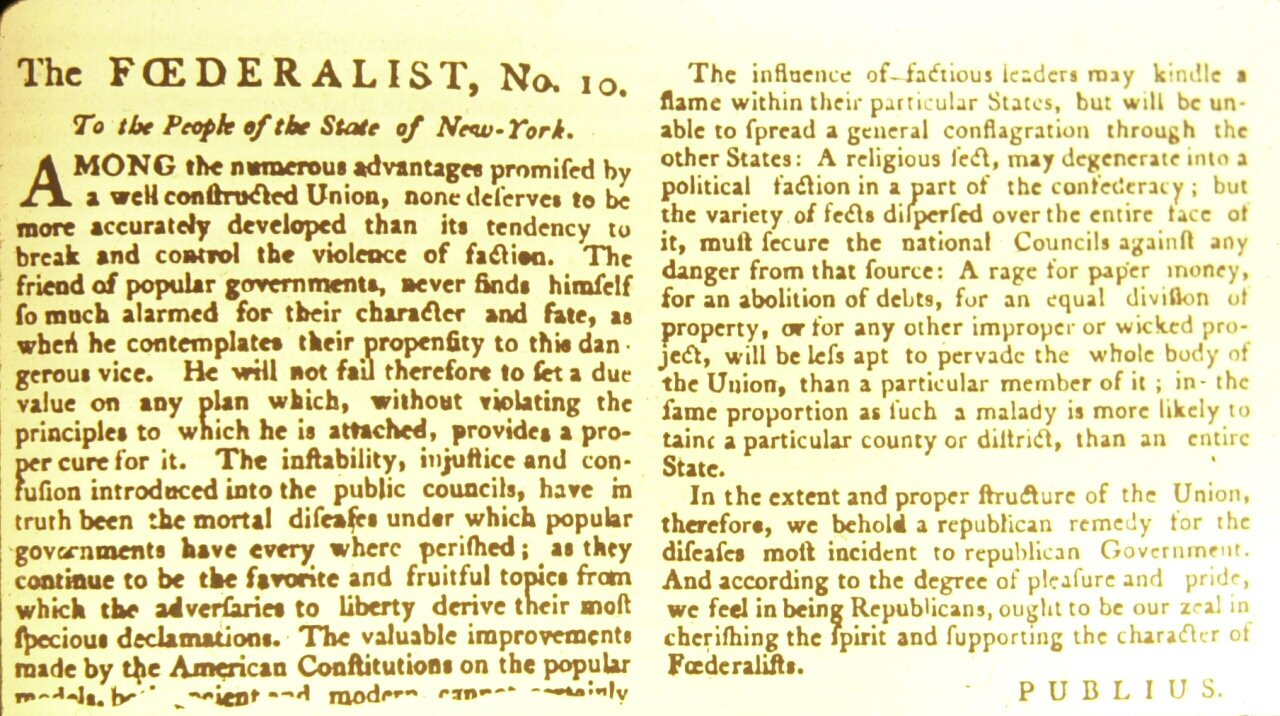

Despite all that, rebelling against a government and even overcoming it is easier than replacing it with a better one. In 1776, Thomas Paine had suggested a republic in Common Sense but Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence provided no blueprint for a new government. Before them lay a daunting challenge but also an opportunity to institutionalize Enlightenment politics. Founder Alexander Hamilton pondered in Federalist No. 1 whether societies are capable of establishing governments based on reflection and choice as opposed to mere accident and force, as argued by Renaissance philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli (right).

Despite all that, rebelling against a government and even overcoming it is easier than replacing it with a better one. In 1776, Thomas Paine had suggested a republic in Common Sense but Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence provided no blueprint for a new government. Before them lay a daunting challenge but also an opportunity to institutionalize Enlightenment politics. Founder Alexander Hamilton pondered in Federalist No. 1 whether societies are capable of establishing governments based on reflection and choice as opposed to mere accident and force, as argued by Renaissance philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli (right).

The Framers weren’t starting from scratch because the colonies had a long tradition of local self-rule behind them. But they had no self-sufficient economy, little history of unity amongst themselves, and no standing military to speak of. They were trying to create the first major republic since ancient times. Not only do most revolutions fail; there was also little historical precedent for representative governments. The Founders sensed that fragility, too, because they were expert amateur historians, at least of Europe. Ancient Greeks, especially in Athens, pioneered forms of democracy from the 6th-4th centuries BCE, whereby free male citizens (~ 30% of people) voted directly on issues rather than indirectly through elected representatives. But those voters were subject to misinformation, made mistakes, got into ill-advised wars, and killed religious skeptics like Socrates. We saw in Chapter 7 how they banished Anaxagoras for arguing that the Moon was a rock rather than a God. Founders read Greeks like Plato, Aristotle, and Thucydides who thought it was mistaken to grant power to the demos. Classical Rome had voting too, and Roman politician Quintus Tullius Cicero even published a cynical guide in 64 BCE on how to manipulate voters and smear opponents.

The Classical Maison Carrée in Nîmes, France Inspired Buildings Like Jefferson’s Virginia State Capitol and the Supreme Court. The Greek Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis Was Also influential.

Romans provided the most durable example, maintaining a republic for around 500 years (509-27 BCE) that reverted to a dictatorship in the century before Christ as they expanded into a bigger empire. America emulated Classical Rome in its republican government, reliance on slavery, dedication to engineering, and freedoms of divorce and speech. As we’ll see below, America expanded in a way similar to the Roman Empire and adopted Roman measurements. It’s no coincidence that the U.S. modeled its most important buildings and monuments in the Classical style. Still, the fact that Rome’s expansion coincided with its reversion to dictatorship couldn’t have filled America’s Founders with confidence about an expanding republic. More recent smaller republics existed in medieval Switzerland (the Helvetic Republic protected by the Alps from the Austrian monarchy), Italian city-states (Genoa and Florence, 1115-1532 CE), Sweden, Poland, Denmark, the Netherlands (Dutch Republic/United Provinces), and some German and Russian city-states (mercantile republics) where wealthy merchants had managed to wrest power away from the landed nobilities traditionally tied to monarchies. Large-scale republics weren’t a part of Europe’s political landscape, though.

There were older democratic experiments in ancient India, Mesopotamia, and pre-colonial Africa that the Founders were unaware of. Closer to home, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy was a representative government. Local councils and citizen-led committees also go way back in history, even under authoritarian or monarchical rule. There’s always some power among the people regardless of the political system and, for most of history, tribal leaders couldn’t afford to rule as unpopular totalitarians. What stood out about America’s republican experiment wasn’t so much novelty as scale. The English Civil War created a republic of sorts during the Interregnum of the 1650s but they restored their monarchy after just eleven years under the Cromwells’ Commonwealth. Still, England had a long heritage of its landowners presuming that their government owed them something and had gradually evolved a mixed system whereby the Crown shared power with Parliament and ministers.

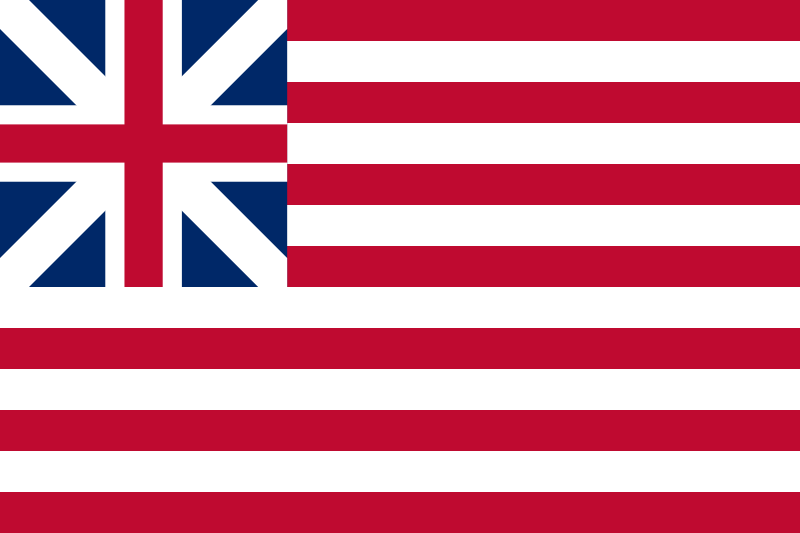

The British American colonies provided the best and most familiar examples of republics because they’d mostly run themselves for 150 years by the time the Revolution rolled around, providing a foundation to erect a new country on. But no country had attempted a single republic on a geographic scale as large as eastern North America since the Romans. The American rebellion hadn’t even aimed to get rid of the king at first, only at protesting British policies on taxes, western expansion, religious freedom, smuggling, and potential abolition. Now, just a few years later, the victors had no king or parliament and were trying to launch a form of government with no promising track record. As of 1777, they hadn’t even settled on a good flag yet. In 1775, back when they wanted to assert their rights but stay in the British Empire, Rebels had adopted their Grand Union Flag from the British East India Co., which operated as an autonomous corporation within the empire (still ironic considering that the BEIC was the target of the Boston Tea Party, but the flags were readily available). As we saw two chapters ago, though, banners building on that basic layout soon morphed into the “Stars and Stripes.”

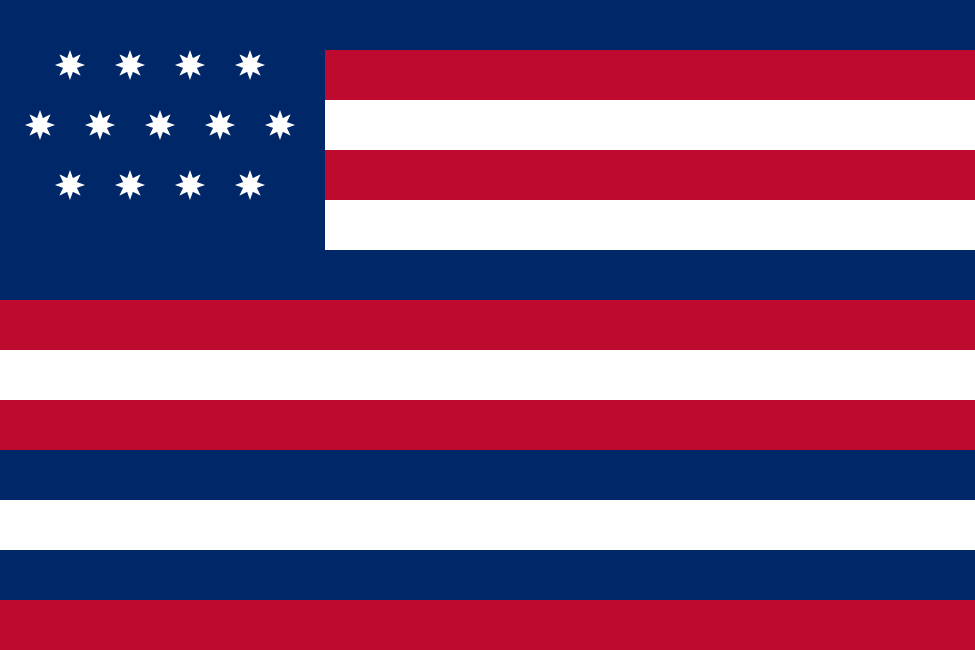

Writing from France in 1778, ambassadors Ben Franklin and John Adams wrote to Naples’ ambassador: “It is with pleasure that we acquaint your excellency that the flag of the United States of America consists of thirteen stripes, alternately red, white, and blue; a small square in the upper angle, next [to] the flagstaff [pole], is a blue field, with thirteen white stars, denoting a new constellation.” Yet, without a picture, people interpreted that description in different ways. John Paul Jones, for instance, flew the ensign on the left over his ships during the war. Jones’ streamer is truer to Adams’ and Franklin’s design than the one Betsy Ross purportedly sewed, though neither seemed to read the directions carefully.

Articles of Confederation: Accomplishments

Americans tried twice to come up with a successful formula for a government uniting states in a union. The first, the Articles of Confederation, was drawn up during the Revolutionary War and lasted until 1789. We still use the second, the Constitution, today. While the United States is a relatively young country, it runs under the oldest major government on Earth, 1789-present, and is the oldest democracy (World Economic Forum). The English/British House of Commons, specifically, has met continuously since 1689, Iceland’s Althing since 930 CE, the Isle of Man’s Tynwald since around the 10th c. CE, and San Marino since 1600 CE.

Before looking at problems with the Articles that led the Founders to abandon them, it’s worth looking at what worked well under the Congress of the Confederation, or Confederation Congress that operated under the Articles. First, and easiest to overlook, is the very fact that the Rebels, with help from France, won the war with limited resources and domestic support against a formidable military.

Second, it might have been too jarring to go from separate colonies to unified states all at once. The colonies had only unified just prior to the war, mainly for military expediency. The Anti-Federalists who liked things the way they were under the Articles of Confederation, favoring state power and opposing a national government, weren’t irrational reactionaries. They just lost out as problems and threats, external and internal, created a need for more stability. Meanwhile, the Articles of Confederation served as a segue, or transition, from union to real nation between 1777 and 1787. They were a useful stepping-stone as citizens wrapped their heads around identifying with a bigger political unit, a process that wasn’t complete even after a painful civil war 80 years later (and, to avoid sounding too teleological, could revert in the other direction in the future; polls show that ¼ of Americans favor their state seceding). Given the lack of representative governments to study historically, the early individual states provided a laboratory of test cases by each drawing up their own constitutions. The Founders drew on those examples when they drafted a national constitution in 1787. The federal combination of state and national power serves a similar purpose today on a number of issues ranging from healthcare to education to energy. You could think of the respective states as Petri dishes or what 20th-century Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis called the real “laboratories of democracies.”

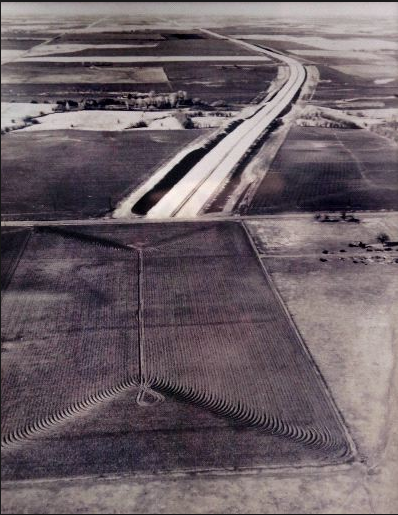

Take, for example, a key issue like hydraulic fracturing, or fracking — the type of drilling that involves horizontally injecting chemicals, sand, and water into shale rock to capture hydrocarbons like natural gas and oil. Fracking has enormous advantages and drawbacks, promising the U.S. boundless supplies of cheap energy and decreasing reliance on the Middle East, while potentially polluting air and water aquifers, using a lot of already scarce freshwater, triggering earthquakes in prone areas (from underground wastewater injection), and accelerating climate change through methane flaring and leaks if done carelessly (methane emissions stay in the atmosphere longer than CO²). States have compromised in different ways, with some banning it altogether (e.g. California and New York) and some saying “drill baby, drill.” Colorado brought drillers and environmentalists together to regulate leaks. If the issue was only before the national government, who knows what would happen, but our system allows states to study each other to see what’s working. Eventually, maybe the national government can adopt a successful state model like Colorado’s through the EPA; or conversely, an EPA hijacked by special interests could override certain states’ smart policy with a uniformly bad policy. More state, county, and municipal power also sustains self-government, an essential component of democracy. And, state and local governments serve the practical purpose of relieving the national government of burdens and tasks that would be inefficient to run out of a central location. If, on the other hand, you’re a person that uniformly favors states’ rights, with no appreciation at all for national power, take a look at the border between Arkansas and Texas before the interstate highway system. That’s a metaphor for a lot of other problems, including being too decentralized to have gone to the Moon, outlawed discrimination, or stood up against global rivals like Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia in the 20th century. We don’t have room here to unpack analogous pros and cons of potential world government, but that won’t be a realistic prospect in our lifetimes anyway, and that’s not the function of the United Nations (1945- ). Today, states’ rights proponents are arguing against national funding to upgrade the nation’s electrical grid, a key step in coping with climate change.

Take, for example, a key issue like hydraulic fracturing, or fracking — the type of drilling that involves horizontally injecting chemicals, sand, and water into shale rock to capture hydrocarbons like natural gas and oil. Fracking has enormous advantages and drawbacks, promising the U.S. boundless supplies of cheap energy and decreasing reliance on the Middle East, while potentially polluting air and water aquifers, using a lot of already scarce freshwater, triggering earthquakes in prone areas (from underground wastewater injection), and accelerating climate change through methane flaring and leaks if done carelessly (methane emissions stay in the atmosphere longer than CO²). States have compromised in different ways, with some banning it altogether (e.g. California and New York) and some saying “drill baby, drill.” Colorado brought drillers and environmentalists together to regulate leaks. If the issue was only before the national government, who knows what would happen, but our system allows states to study each other to see what’s working. Eventually, maybe the national government can adopt a successful state model like Colorado’s through the EPA; or conversely, an EPA hijacked by special interests could override certain states’ smart policy with a uniformly bad policy. More state, county, and municipal power also sustains self-government, an essential component of democracy. And, state and local governments serve the practical purpose of relieving the national government of burdens and tasks that would be inefficient to run out of a central location. If, on the other hand, you’re a person that uniformly favors states’ rights, with no appreciation at all for national power, take a look at the border between Arkansas and Texas before the interstate highway system. That’s a metaphor for a lot of other problems, including being too decentralized to have gone to the Moon, outlawed discrimination, or stood up against global rivals like Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia in the 20th century. We don’t have room here to unpack analogous pros and cons of potential world government, but that won’t be a realistic prospect in our lifetimes anyway, and that’s not the function of the United Nations (1945- ). Today, states’ rights proponents are arguing against national funding to upgrade the nation’s electrical grid, a key step in coping with climate change.

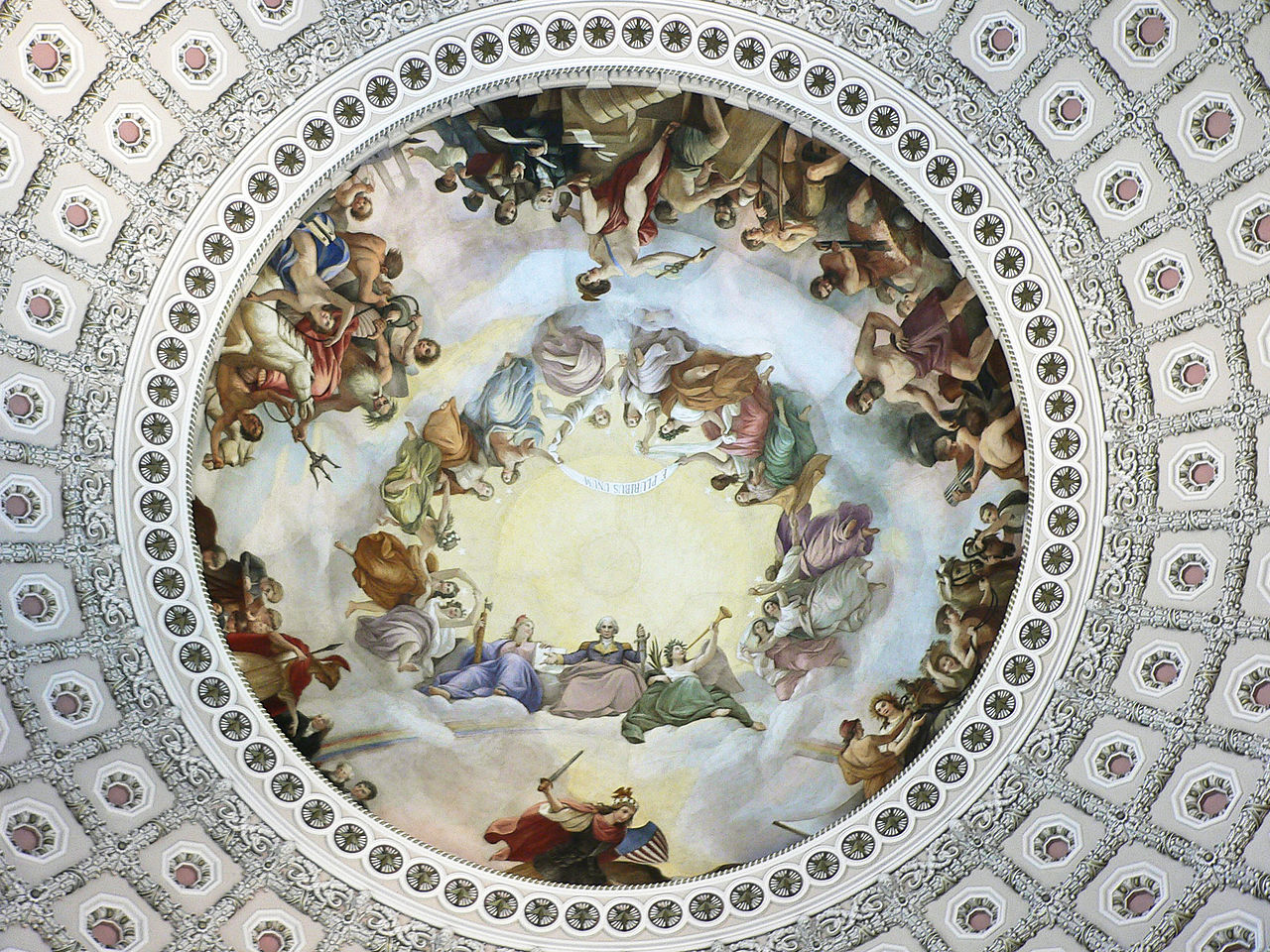

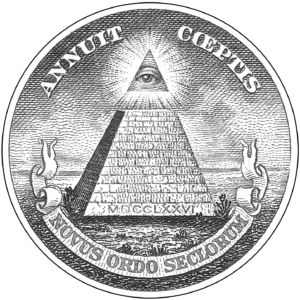

The federal setup only seems obvious in retrospect, whereas at the founding they easily could’ve remained as thirteen loosely affiliated states or, conversely, abolished the states except as administrative districts and united unambiguously as one nation. America’s motto of E Pluribus Unum (out of many, one), captured in the Capitol Rotunda painting below and on American currency, could’ve been just Pluribus or Unum. Instead, the thirteen angels in Constantino Brumidi’s Apotheosis of Washington (1865) retain their identities but form an interlocking circle.

The Apotheosis of Washington (as seen looking up from the Capitol rotunda), Constantino Brumidi, 1865

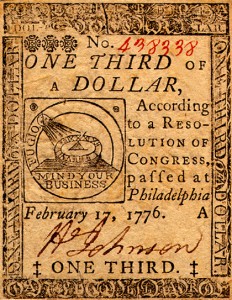

Third among accomplishments under the Confederation Congress, the country survived the economic turbulence of its first decade, when there was no strong national currency as the states reeled under war debt. The phrase ain’t worth a continental originated in the 1780s when counterfeiting was common, with the best engravers working for criminals since they paid more than the government. The country itself was flat broke, with Congress indebted to the states and foreign countries. The economy had to be cleaned up and re-organized down the road (more next chapter) but, in the meantime, at least the chaos didn’t take down the fledgling country. Still, economic instability was a reason for, not against, creating a more unified national government.

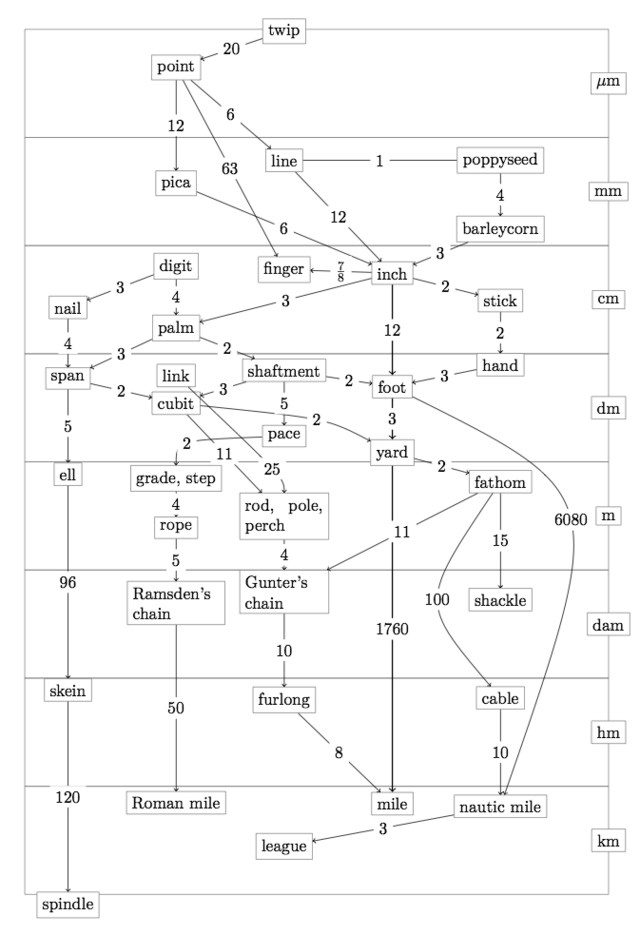

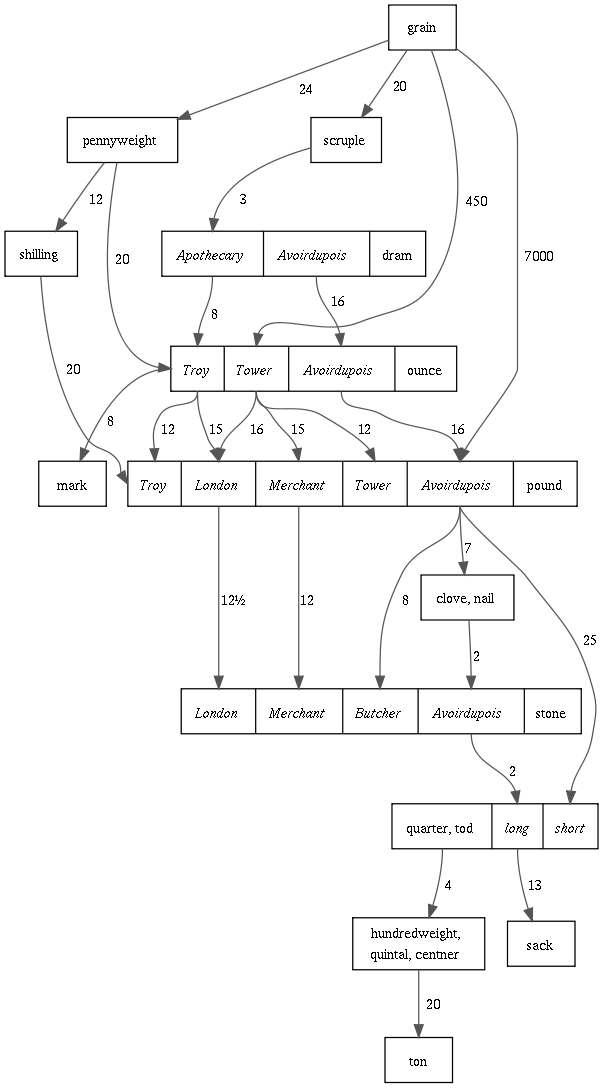

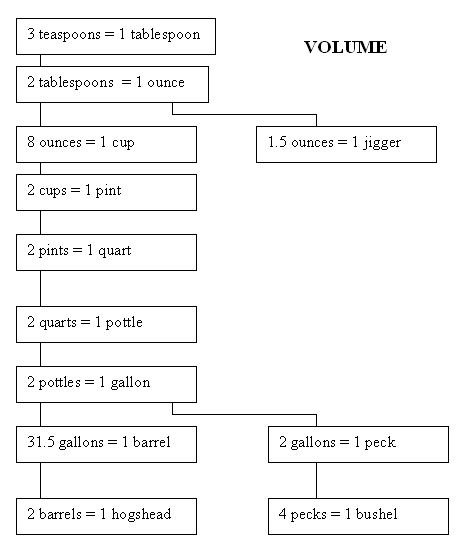

Fourth, Congress established standards for weight, volume, and distance, unfortunately adopting the English (or Imperial) System just a few years before the French institutionalized the more intuitive, user-friendly metric system during their revolution. Today, the U.S. is one of just three countries, along with Liberia and Myanmar, that officially use the Imperial System, though Britain often does in practice despite being officially metric. The association of metric with Enlightenment France is one reason that some Americans resisted transitioning later to “atheistic” units. Early U.S. customary measurements were roughly similar to those codified in Britain in 1824:

Dating back to Roman and Anglo-Saxon history, these proportions have some folksy charm but lack common standards and baselines. There were two different measures of a foot, one international and one U.S. survey. Only an expert could take you from a grain to a ton (left) and few among us could gauge the difference between a Gunter’s chain and a furlong (above). Volume isn’t a total mess, though it’s not readily apparent how many jiggers equal a hogshead (below). In an age before accurate scales, it’s a wonder more barterers didn’t strangle each other. That might partially explain why, as a matter of custom, deals and lawsuits were negotiated, sealed, and settled over a pottle or two of liquor.

The military adopted the Metric System for some precision measurements in 1949 and, after the Metric Conversion Act (1975), Americans adopted metric in science, some industry (e.g. auto fasteners), and track & field (1980s). The rest of us remain stuck in a classic case of path dependence, whereby it’s impractical and inefficient in the short run to convert to what would be a more efficient system in the long run (the same is true of the purposely slow QWERTY keyboard layout). An auto mechanic, for instance, might have an easier time of it living in Europe or Asia and just using metric; second-best would be to live in America before 1975 and just use the English system; third-best would be to live in modern America and have to transition back-and-forth between inches and millimeters. In 1999, NASA lost its Mars Climate Orbiter because of a mix-up between metric and English (newton-seconds [N s] vs. pound-seconds [lbf s]).

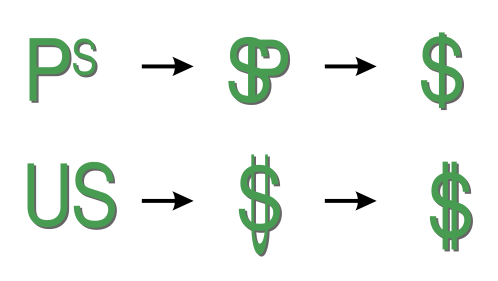

Thankfully, Thomas Jefferson established U.S. currency in metric units of ten from the beginning. The early dollars, pegged to British currency, were similar in size and composition to Spanish dollars, and Spanish dollars and Mexican pesos were legal tender in the U.S. until 1857. As we saw in Chapter 3, one theory is that the pesos’ scroll-wrapped columns (the Pillars of Hercules on the Spanish coat-of-arms) gave rise to the famous $ sign. Another theory is that it grew out of shorthand for U.S. For those that cared to keep time — and within half a century nearly everyone would need to — they retained the Babylonian sexagesimal (base 60) system of sixty seconds in a minute, sixty minutes in an hour and 360 degrees in a circle.

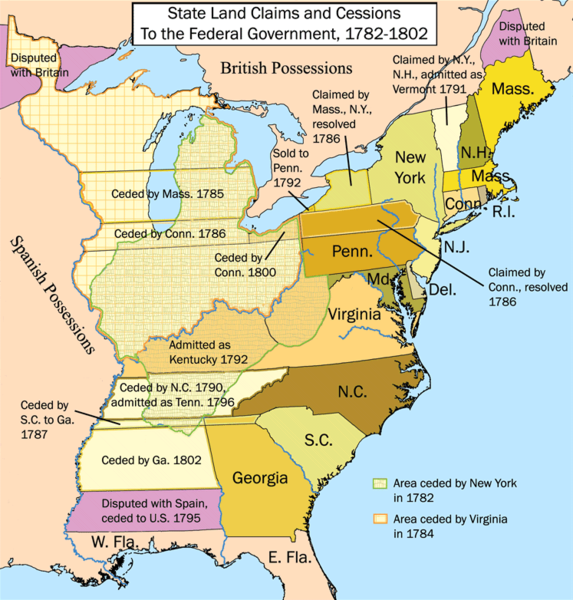

As a fifth accomplishment, the Confederation Congress settled disputes between the states over western lands, which is another problem easy to overlook in hindsight. Some of the original colonial charters granted territory “from sea to sea,” one of the reasons the colonists resented the British Proclamation Line along the Appalachians. In the 1760s, Connecticut and Virginia invaded parts of Pennsylvania. By the 1780s, maps were starting to show a series of difficult-to-manage horizontal bands and more states were claiming areas above and below their respective stripes. Virginia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut claimed the Old Northwest Territory in the Great Lakes region. Smaller units also threatened to break away from existing states. The rebel state of Franklin (aka Frankland, or the Free Republic of Franklin), now in Tennessee, seceded from North Carolina. America’s early history is a reminder that there was nothing given about the states’ borders; each had to be negotiated or even fought over.

The Confederation Congress convinced the states to do the reasonable thing and give up their western claims. Consequently, they not only won the Revolutionary War, they might’ve prevented civil wars. However, they accidentally sowed the seeds for civil war down the road by regionalizing slavery. They banned slavery in the old Northwest Territories (black in the map on lower right) but failed to in new territories south of the Ohio River, thus creating a north-south divide over slavery when the original northeastern states gradually abolished slavery after the Revolution. While we remember Thomas Jefferson most as a slaveholder and defender of slavery later in life, he suggested the anti-slavery provision in the Northwest Ordinance, making him an important early abolitionist. His 1784 plan even called for prohibiting slavery in all new western territories, including those in the South, but Congress didn’t pass it. The fact that his amendment lost by only one vote is a striking example of how history could’ve gone in a completely different direction. Still, slavery’s decline in the North after the Revolution and the Jefferson-inspired Article 6 of the Northwest Ordinance prohibiting it in the Old Northwest set the stage for the Union’s abolition of all slavery during the Civil War. Consequently, Civil War-era Southerners were ambiguous toward Jefferson.

Confederation Congress also set up a procedure in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 whereby the new western lands could become territories after attaining a population of 60k, then draft a state constitution in line with national constitutional principles and apply for statehood. These new states would come in as equal partners with the old states. Instead of adopting the British model of growing subordinate colonies – the system the colonies had chafed under – the U.S. adopted the Roman model of growing into contiguous areas, with new areas enjoying equal status. The Romans could be exceedingly harsh in this process, as in Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars, in which his legions murdered and enslaved most of the French population. But, after conquering, Romans granted some survivors full citizenship and often allowed them to retain distinct languages, religions, customs, etc. This Roman growth-through-expansion rather than colonization model was essentially what Thomas Jefferson updated with his Empire of Liberty phrase, except that the U.S. didn’t allow independent life for Native Americans, or citizenship until 1924. The first exceptions to the contiguity principle were Alaska and Hawaii but they too came in as equal states in the 1950s. The first exceptions to the equality principle were territories gained in the Spanish-American War of 1898, including Puerto Rico and Guam. The idea of a written constitution, though, that we’ll unpack below, came from ancient Greece, not Rome or Britain.

Jefferson’s Land Ordinance of 1784-85 dictated how the territories would be further subdivided down into square-mile sections and acres. The Ordinance is responsible for the familiar checkerboard pattern you can see flying over flat farming areas today. Peter Ling’s optional article below argues that imposing these straight lines didn’t optimize yield or sustainability, especially out west, though future generations could’ve done things differently. Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance also encouraged new states to fund primary schools and public universities, both of which eventually happened.

Articles of Confederation: Failures

Overall, though, the Articles didn’t bind the country together tightly enough. Its drafters, including John Dickinson most influentially, took Thomas Paine’s advice of unifying the states but keeping most of the power at the state level. The national government had no significant executive branch or national court, and Congress couldn’t pass legislation without nine of the thirteen states agreeing to it. There was a president of Congress; John Hancock, Samuel Huntington and John Hanson of Maryland were technically the first American presidents, not George Washington, and Washington always politely referred to Hanson as the first president since he was the first elected and first to serve a full term. But these men just presided over Congress and didn’t have much power. The states also printed their own money and negotiated their own treaties with foreign countries. The U.S., in short, was heading toward an arrangement similar to the modern European Union, where an umbrella serves some purposes but doesn’t constitute a true country that citizens identify with. The EU is a confederal setup, a free association of states who maintain independent power. People identified mainly with their states and, even years later, when Jefferson said he “loved his country” he meant Virginia not the U.S. The same held true of Confederate General Robert E. Lee two generations later. While somewhat torn over allegiances in the Civil War, he ultimately chose to fight for his “country” of Virginia.

Second, the early states worked at cross-purposes, economically. Historian Fernand Braudel chronicled how, not only did the British profit by losing the Revolutionary War — reducing overhead administrative and military costs while maintaining trade — they also crippled the early American economy with high protective tariffs that Americans couldn’t retaliate against because they weren’t unified financially under the Articles of Confederation. This is a problem today in the European Union, which is a monetary but not fiscal union (to wit: European countries share a common currency, but individual countries set their own budgets). When the Founders replaced the Articles of Confederation with the new Constitution, they gave the national tier control over interstate trade with the Commerce Clause to prevent states from passing tariffs and barriers against one another. They could no longer coin or print their own money, void each others’ debts, or sign separate treaties with European countries.

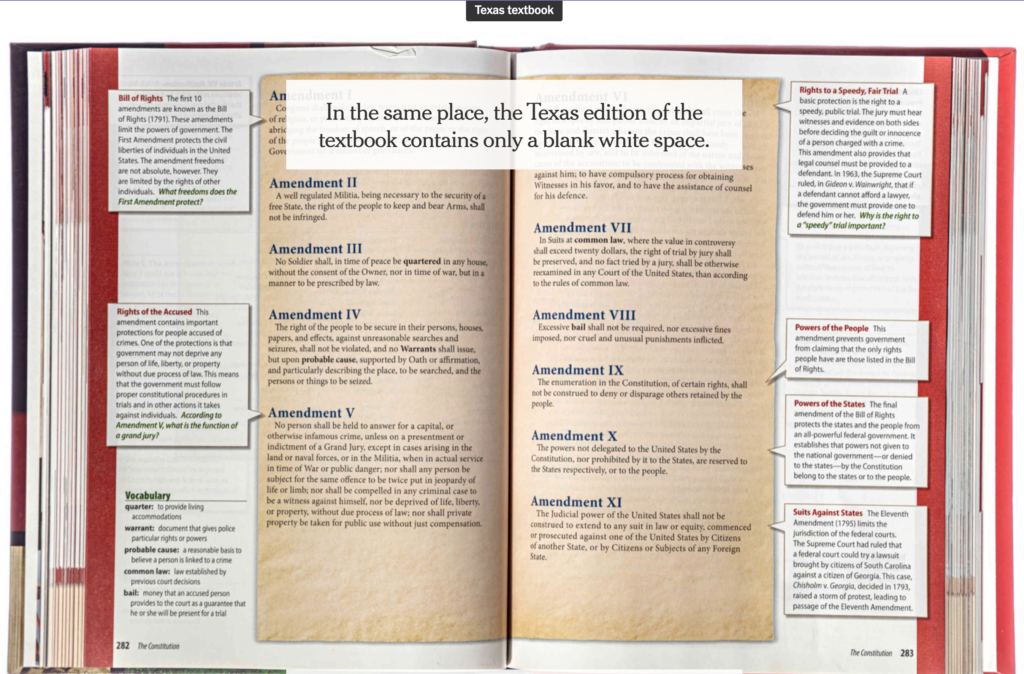

A third weakness was the Confederate Congress’s inability to tax. Without taxes, there was no military and, without a military, the U.S. had no real control over its own civilians or diplomatic leverage abroad or in relation to America’s original inhabitants. They maintained a one-regiment army between 1784 and 1789, but no sizable navy or marines. America’s best sailor, the forenamed John Paul Jones, signed on with Catherine the Great’s Russia as a rear admiral. State militias maintained most of the military power, which we’ll unpack more below in our discussion of the Second Amendment. As of the United States’ founding, Native Americans controlled most of the interior, regardless of what Europeans drew on maps or swapped in peace treaties. Spain, meanwhile, threatened from the South and Britain never bothered leaving their forts on the western frontier after the war, per the 1783 Treaty of Paris, because they knew the U.S. couldn’t force them to. Spanish Louisiana and British Canada also tried to lure American settlers with cheap land, favorable trade terms, and low taxes. Pirates didn’t recognize the U.S. flag, whatever design they tried, and plundered merchant ships at will once they figured out the country had no significant navy. One historian reduced the Articles of Confederation to nothing more than a mutual defense pact with no army.

Shays’ Rebellion

There were also problems under the Articles of Confederation controlling American civilians. Disgruntled war veterans from Massachusetts, led by Captain Daniel Shays, seized muskets and gunpowder at the state arsenal and marched east to appeal to the state government. Their goal wasn’t so much to kill people as to use the guns to get their point across. They opposed rising taxes, a requirement that they pay for goods in hard currency rather than barter, and high farm loan payments with usurious interest rates. They wanted transparency among political leaders in league with financiers and to prosecute corrupt officials.

Aside from not being paid well to fight, many veterans never got their promised land after the war or the IOU notes (bonds) they got instead became nearly worthless. Or, at least they thought they had. After many sold their bonds to speculators, the government decided to make good on them at full face value and, adding insult to injury, they had to raise taxes on regular people like the veterans to pay off the bonds to the speculators who bought them cheap from veterans. The veterans/farmers’ frustration was understandable, to say the least. Shays received nothing for all his years of service and then returned home to find his farm getting foreclosed. That’s the thanks he got for helping to launch the United States. Also, monetary deflation increased the real value of farmers’ loan payments. Men like Shays wanted titles to be held by the farmers who were actually improving the land, not landlords or speculators.

“Shays’s Rebellion.” The portraits of Daniel Shays and Job Shattuck, leaders of the Massachusetts “Regulators,” Cover of Bickerstaff’s Boston Almanack of 1787, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

In the bankers’ defense, farmers had taken out loans they were forfeiting on and the bankers, who didn’t have anything to do with their low wartime pay, couldn’t just stand by and have their money stolen from them. While the lower house of Massachusetts’ legislature sided with the rebels, the upper house sided with the farmers’ creditors. There were small-scale skirmishes as the rebels closed down some state courthouses in the western part of the state but failed to seize arms at the federal armory in Springfield. Massachusetts raised their own militia from urban servants and arrested the rebels (two were hanged) but moneyed interests still found the whole episode unsettling. Shays’ Rebellion raised fears in other states and, at one point, troops even threatened the Confederation Congress in Philadelphia. It also echoed an earlier uprising in the Carolinas before the Revolution called the Regulator War, a drought and debt-fueled revolt of small farmers and tenants against corrupt officials and wealthy landholders.

Even before Shays’ Rebellion, a consensus was forming among the powerful that class war might only be averted with a strong, central government. They weren’t talking about arguments over whether the wealthy should pay 36% or 39% of their income toward taxes, the way we are today when we throw the term class warfare around; they were talking about class warfare of the sort that happened in Shays’ Rebellion, with guns and hanged rebels. The uprising underscored, for one, the necessity of establishing a more dependable and stable national currency. European traders skeptical of early state currencies were demanding gold and American merchants on the coast were, in turn, asking backcountry farmers for gold they didn’t have access to. High inflation followed by steep deflation whipsawed the young country’s fragile economy, leading to predictable conflict between lenders and borrowers. Inflation victimized eastern bankers (lenders) who lent to farmers but got less back and deflation victimized western farmers (borrowers) who had to repay more.

In short, someone from within or without likely would have overrun the U.S. if they hadn’t united behind a stronger central government — Britain or Spain from without or home-grown rebels from within. At a 1786 meeting in Annapolis, Maryland, five of the biggest states decided to hold a convention the following year in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation, plan canals that would improve commerce by connecting the eastern seaboard to the growing interior and, most of all, restore enough law and order to prevent uprisings like Shays’ Rebellion. George Washington was one leader displeased with Shays’ Rebellion’s broader implications and he backed the idea of a new government. Washington’s backing was essential in convincing a sizable minority of the need for a shakeup, and he presided over the Constitutional Convention the following Spring, lending it credibility.

Spirit of ’87: Safeguarding Against Democracy

That winter, leaders studied what was working in the various state constitutions and what was not. New Hampshire, for instance, put too much power in the peoples’ hands (in their opinion), with delegates from every town and village participating in state government. Two states, Pennsylvania and Georgia, took the inspiring language of the Revolution too far and spread the vote to regular white men — ones that didn’t own substantial property. New Jersey allowed single women and free blacks to vote from 1776-1807, at first as an oversight (optional article below). Pennsylvania’s unicameral (one-house) legislature eliminated the upper house and the governor, prompting John Adams to harrumph that the state was “so democratical that it must produce confusion and every evil work” (from James 3:16 KJV).

Regular people threatened the wealthy because of their potential to upend patriarchy, tax or pass crazy laws to forgive all debts, or force people to accept undependable state currencies. When it comes to money, the rich can be exploitative and the poor can be misguided, not realizing that you can’t just print more money and make everyone richer. Since most people are debtors, majorities would forgive debts but then no one would lend again, grinding state economies to a halt. Even Jefferson, the strongest promoter among leaders of universal white manhood suffrage — he included the provision for new states with the Northwest Ordinance — said something must be done to “silence the Democratick Babble.” Jefferson, though, would’ve preferred some minor tweaks to the Articles of Confederation rather than a new full-blown Constitution with a strong national government. Unfortunately for him, he wouldn’t be around to press his case since he was in Paris on diplomatic duty.

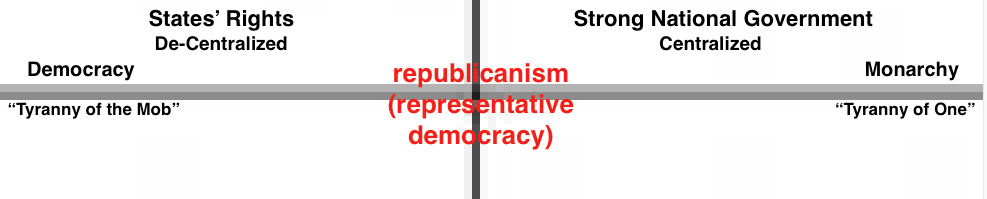

This spectrum measures how centralized or de-centralized a political system might be, with small-r republicanism as a compromise between the tyranny of the mob versus the tyranny of a king. It’s not to be confused with the more famous left-right spectrum used today concerning the degree of government involvement in the economy, or cultural/social issues.

The Founders wanted to avoid a pure democracy like Athens in the 6th c. BCE, whereby Greek citizens voted directly on issues without politicians intervening. Democracy, for them, was a pejorative term. Whereas the Spirit of ’76 helped mobilize the masses to defeat Britain, the Spirit of ’87, had they used such a phrase, was more about stuffing that revolutionary genie back in the bottle. Just as they wanted their version of republicanism to avoid a dictatorship of one (a monarchy), so too they strove to avoid a dictatorship of many (democracy). The mob, after all, was passionate and uneducated. Republicanism, or representative democracy, was an attempt to balance the fairness of democracy with the stability of monarchy. Founder Benjamin Rush explained that “power under the new system may be derived from the people, but they possess it on election day alone….[beyond that] it is the property of their rulers.”

James Madison also feared the “cabals of a few” emerging from the masses in his essay Federalist No. 10. Madison thought that peoples’ ideas should filter through elected officials in order to “refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.” The chart above gives you a rough idea of how they wanted a representative democracy that would avoid extremes of tyranny on either end: a dictatorship of one or a dictatorship of the mob. Madison wrote that “democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths.” John Adams put it more bluntly, calling normal Americans “vile, detestable and loathsome.” Adams prophetically, if un-democratically, wrote:

It is dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications of voters; there will be no end to it. New claims will arise; women will demand the vote; lads from 12 to 21 will think their rights not enough attended to; and every man who has not a farthing, will demand an equal voice with any other, in all acts of state. It tends to confound and destroy all distinctions, and prostrate all ranks to one common level. Adams to James Sullivan, May 26, 1776

Of course, it’s only fair to put Adams’ snobbishness toward commoners in perspective; he also thought the “Father of the Country” was unfit for public office: “That Washington is not a scholar is certain. That he is too illiterate, unlearned, unread for his station is equally beyond dispute.” Fearful of democracy, the Founders’ goal was to compromise with a republic, or representative democracy, whereby certain qualified individuals voted for politicians, who then made the decisions. Why? As George Washington put it, “for the same reason one cools down coffee by pouring it from a cup into a saucer.” We don’t often use saucers under our coffee cups anymore, but you get the point.

Fellow Virginian Edmund Randolph said, “Our chief danger arises from the democratic part of our [state] constitutions.” Another fellow Virginian, Madison, said that something must be done to “check those who labor under all the hardships of life and secretly sigh for a more equal distribution of its blessings.” Translation: the people who actually do the work are going to tax the rich if we let them vote. John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court, didn’t mince words: “those who own the country ought to govern it.”

The Founders, as we call them, were the rich and powerful. They included business leaders and planters working with lawyers to maintain a system in which they could thrive. Emboldening, reinforcing or inspiring working-class Americans wasn’t on their agenda. In the North, at least, the U.S. provided avenues of upward mobility, whereas the southern economy relied on traditional slave exploitation by landowners.

After the January 6th insurrection, several candidates ran in the Fall 2022 elections on platforms opposed to, or at least in favor of weakening, democracy, hoping to capitalize on a key misinterpretation of the Founders. Rachel Hamm ran for California’s Secretary of State on the Republican ticket saying “I want to make it hard [to vote]” while Mike Lee (R-UT) said “we’re not a democracy. Democracy isn’t the objective; liberty, peace, and prosperity are. We want the human condition to flourish. Rank democracy can thwart that.” In Washington state, congressional Republican candidate Loren Culp called democracy “mob rule.” Finally, the new Speaker of the House elected in 2023, Mike Johnson (R-LA), a key player in the 2021 coup attempt, agreed that “We don’t live in a democracy.” But, while it’s true that America’s Founders created a representative democracy instead of a pure democracy à la ancient Athens, that accurate civic lesson isn’t a convincing cover for overturning the vote in a presidential election (e.g. fake elector plot), making it harder to vote, or suggesting that the U.S. transition toward a more authoritarian version of democracy à la modern Hungary. For most of modern U.S. history, including as recently as 2020, both political parties and nearly everyone associated democracy with American identity and patriotism, and voting is a key part of a representative democracy. But it is mostly a system of representative democracy with politicians as representatives instead of every issue being decided directly by voters through referendums, initiatives, propositions, bond issues, etc. One advantage of that is that on referendums voters will always vote to spend more money and cut taxes simultaneously on the same ballots indicating that, fiscally, we might need that protective layer of representation.

Before we transition to United States 2.0, this is a good time to reflect on what you’ve learned so far, absorb it, and take a break (drink water, walk around). Return when refreshed to read about how the Constitution we now live under came about.

Madison’s Plan

Unlike most of the men invited to the Philadelphia convention, James Madison studied all winter, including Greek, Roman, and British attempts at representative (or parliamentary) democracy and what the early American states had done with their own constitutions. You could call the proposed American system a democratic republic or representative democracy. From Paris, Jefferson sent Madison two boxes of books on the history of republicanism. Madison read Montesquieu, a French philosopher who wrote favorably on Britain’s parliamentary system in The Spirit of the Laws (1748). Along with John Locke, Montesquieu promoted and established the basic principles of republican government. Yet even Montesquieu was skeptical about republicanism working in large areas with millions of people. The early U.S. numbered roughly three to four million dispersed over an area larger than any country in Europe except Russia.

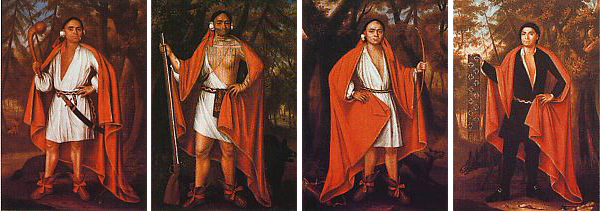

Native America also surrounded the Constitutional framers with small governments that included democracies. American Indians’ political organization, especially its relative lack of hierarchy, non-hereditary chain-of-command, and checks on centralized power, caught the attention of Montesquieu and other Enlightenment philosophes like Locke, Hume, and Rousseau infatuated with the “natural man.” The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy (right), founded in 1142 CE, was the most clearly defined and familiar to the Founders, and still operates today. In their multi-branch system, the role of clan mothers was similar to judges and the council chiefs/sachems of the Longhouse similar to Congress, with elaborate rituals approximating voting. Their republic also added multiple members, similar to how states would constitute the U.S. Ben Franklin negotiated directly with Haudenosaunee Mohawks on Pennsylvania’s behalf and there’s a persistent argument that their League’s Great Law of Peace influenced the Articles of Confederation or Constitution. Iroquois is French for Haudenosaunee.

Native America also surrounded the Constitutional framers with small governments that included democracies. American Indians’ political organization, especially its relative lack of hierarchy, non-hereditary chain-of-command, and checks on centralized power, caught the attention of Montesquieu and other Enlightenment philosophes like Locke, Hume, and Rousseau infatuated with the “natural man.” The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy (right), founded in 1142 CE, was the most clearly defined and familiar to the Founders, and still operates today. In their multi-branch system, the role of clan mothers was similar to judges and the council chiefs/sachems of the Longhouse similar to Congress, with elaborate rituals approximating voting. Their republic also added multiple members, similar to how states would constitute the U.S. Ben Franklin negotiated directly with Haudenosaunee Mohawks on Pennsylvania’s behalf and there’s a persistent argument that their League’s Great Law of Peace influenced the Articles of Confederation or Constitution. Iroquois is French for Haudenosaunee.

In 1740, Mohawk Chief Canassatego counseled Franklin to unite the colonies. Numerous colonists, including Roger Williams and Cadwallader Colden, Lt. Governor of New York Province, also commented favorably on Indian traditions of self-government and liberty. John Adams commented favorably on the separation of three powers among ancient Germans’ and modern Indians’ political systems, as “marked with a precision that excludes all controversy.” At the 1754 Albany Congress prior to the French & Indian War — the occasion for Franklin’s famous “Join or Die” cartoon and the first time representatives from the thirteen colonies ever met — Franklin named their body after the Haudenosaunee Grand Council, probably as a way to convey respect to the many Mohawk chiefs there in attendance whose alliance he hoped to secure for the upcoming war. The Grand Council grounded their theory of government in a fascinating way when they formed their confederacy in the 12th century CE. They not only sought strength through unity and peace, but they also hoped the respective chiefs of the Longhouse would complement one another similar to their Three-Sisters (companion) farming combination of corns, beans, and squash (beans climb corn stalks, replenishing nitrogen that corn leeches, while winter squash displaces pests and weeds on the surface; the harvest provides a diet rich in complex carbohydrates, fatty acids, and amino acids).

Historian and screenwriter C.K. Ballatore pointed out that Franklin admired the way the Haudenosaunee system was federated insofar as their Grand Council didn’t interfere much with local tribal matters. Though John Adams compared the Articles of Confederation favorably to the Iroquoian model in 1787, on the eve of the Constitutional Convention, the fact that he took the time to study it and write an extensive survey shows he took it seriously. Historian Charles Mann wrote that “colonists were pervaded by Indian images of liberty,” and it’s probably no coincidence that when rebels expressed freedom in the Boston Tea Party and Whiskey Rebellion (next chapter), they dressed as Indians.

This intriguing theory of Indian influence merits further investigation, but so far there are no primary sources demonstrating that framers based their Articles of Confederation or Constitution on the Iroquoian model. Despite Congress passing a resolution in 1988 affirming the Haudenosaunee contribution to democracy, few historians believe that Indians directly influenced the design of the U.S. government. The theory breaks down with the assertion that America’s framers had no democratic model other than that of the Haudenosaunee to base their experiment on. After all, the Founders’ final product wasn’t a radical departure from Great Britain’s parliamentary system or the American state constitutions, and their new government was more similar to the British and colonial American models than the Haudenosaunee’s. The same goes for theories on the influence of pirates or Freemasonry on the Constitution. It’s interesting that pirates employed voting, checks-and-balances, and a three-branch system with a court long before the U.S. Constitution (as argued by Peter Leeson), and the same is true of Masonic lodges. But, while the similarities of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and pirate and Masonic organizations are striking and they did precede America’s founding, it doesn’t follow that any of the three directly influenced the framing of the Constitution (of the three, Masonry would be the likeliest candidate since many Founders were Masons). There’s a rule-of-thumb called Occam’s Razor which teaches that, among competing theories, the simplest is often, but not always, the best. In this case the simplest, if least exotic, explanation is that the Founders studied the British and American state governments and, moreover, there is ample evidence that they did just that. Madison and John Adams wrote about what they did and why, so it requires an inside-out methodology of dismissing the best evidence to avoid seeing the European influence. For more on similarities between the U.S. Constitution and the Iroquois’ Great Law of Peace, see the optional PBS article below, but be wary of confusing association with causation (see Rear Defogger #6). The Iroquois Confederacy deserves credit in its own right and is worthy of study as one of the world’s longest-lasting democracies. Iroquois also pioneered the Seven Generation principal of basing political decisions on what would be best for future generations rather than short-term benefit.

Native Americans influenced the constitutional process in a more fundamental way, though, insofar as the need to project organized power into the interior was one reason why the thirteen states unified into a stronger unit than the Articles of Confederation provided. A true national government with a standing army, Bureau of Indian Affairs (1824- ), and powers of diplomacy, taxation and land management provided a more robust mechanism for expansion, while settler colonialism also enabled citizens to fight Indians on their own. The new Constitution authorized Congress to regulate commerce “with the Indian tribes.” Inversely, we mentioned disunity (military and linguistic) in Chapter 8 as undermining Pontiac’s attempt to form a pan-Indian alliance after the French & Indian War. New alliances formed like the Northwestern Confederacy (United Indian Nations) as Native Americans saw the young U.S. government manipulating individual tribes, but none on the scale of the U.S. government, or as lasting.

The American state closest to the mixed-system model of republicanism Madison used for the national Constitution was Massachusetts. Although the colony had famously bristled under British rule (the Massacre, Tea Party, Bunker Hill), the proverbial apple hadn’t fallen far from the tree; the state’s new government was essentially a miniature version of Britain’s. They had a bicameral (two-house) legislature patterned on Parliament’s House of Lords and House of Commons, a court system, and a governor similar to an elected king. John Adams authored the influential Massachusetts Constitution in 1779 with help from Samuel Adams and James Bowdoin.

The Philadelphia Convention

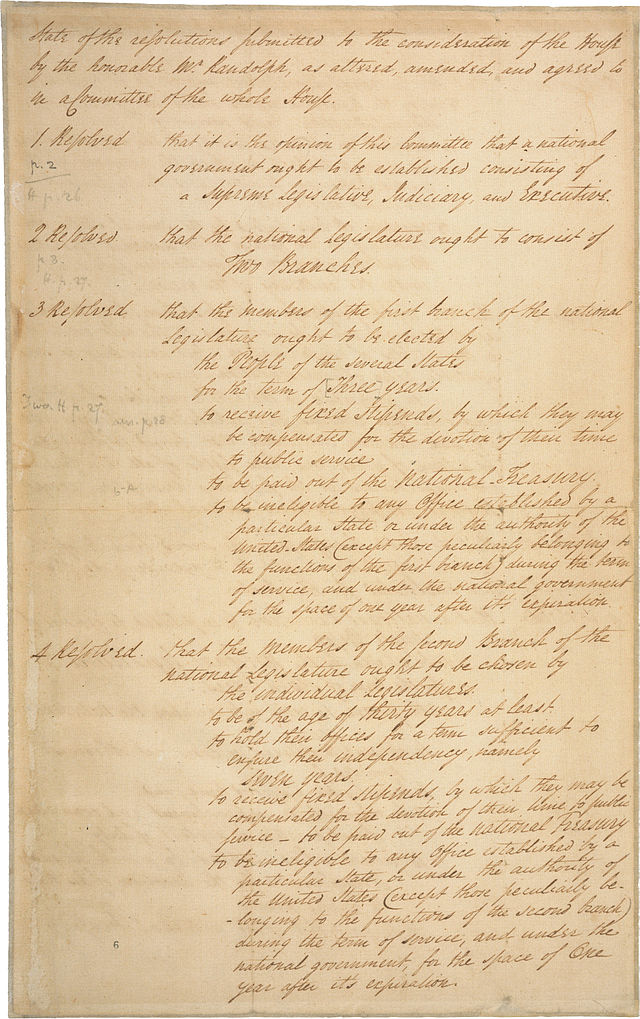

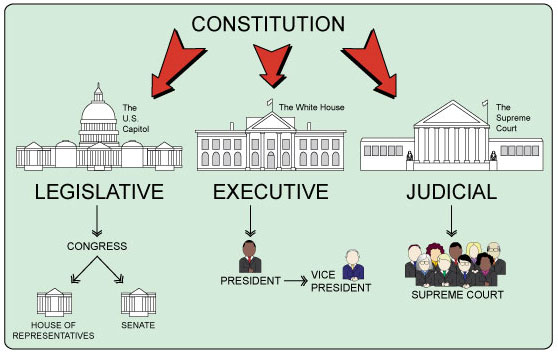

In May 1787, James Madison hit the ground running. At 5’3″ with a slender frame, one colleague described him as “no bigger than a half-bar of soap.” Yet, Madison had an outsized impact on the American Revolution and the country’s future. While the other 55 attendees (of the 80 invited) were still taking off their coats and saying their hellos, Madison was fast at work. He drafted America’s blueprint as they waited for the meeting to reach a quorum, or minimum number in attendance to vote. With the quorum satisfied, forming what they called the Committee of the Whole, Virginia’s Governor Edmund Randolph put Madison’s plan before the Convention forthwith. The Virginia Plan, so named for their home state, established Montesquieu’s three-branch framework on a national scale — the same one Massachusetts was already using at the state level.

Within the national government were three branches – the executive (president), legislative (Congress), and judicial (courts) – tied together by a system of checks and balances (vetoes, overrides, appointments, judicial review) whereby no one branch had ultimate authority over the other two. Congress made laws, but the president could veto laws, but Congress could override the veto with a bigger majority. Whereas in British parliament, the unelected House of Lords (the aristocracy) can “ping” legislation back to the elected House of Commons, which can “pong” it back to override their ping, legislation can originate in either chamber of America’s Congress, the Senate or House of Representatives, and congressional majorities of two-thirds in both houses can override a presidential veto if the president doesn’t sign legislation passed with a simple majority vote the first time. The Senate is in charge of wars, treaties, and confirming presidential judge and Cabinet secretary nominations. Presidential impeachments originate in the House and are tried in the Senate.

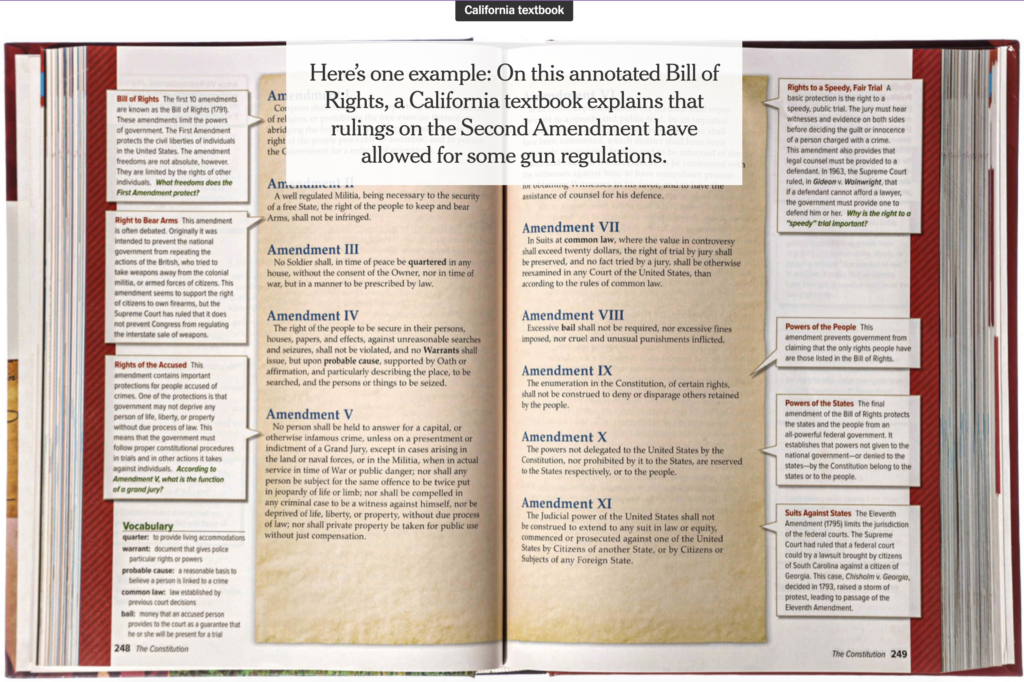

George Washington pressed for unlimited presidential veto power but lost out. The president assigned justices to the Court but Congress authorized the appointments. This is good basic knowledge to review in your history and government classes, as today fewer than 33% of Americans can name the three branches, let alone explain how they relate to one another. Immigrants score much higher and, indeed, have to in order to become citizens. Americans, for instance, shout during election campaigns about potential presidents abolishing the Second Amendment without realizing that presidents can’t repeal Constitutional amendments.

Minds like Madison’s don’t work in a vacuum so much as they recombine and re-adapt existing models. He cooked up a different recipe than Britain or Massachusetts but drew on the same ingredients. As mentioned, Madison was looking to strike the right republican balance between the tyranny of one king and the tyranny of a democratic majority. In 1787, Madison wrote, “Our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation [democracy?]…[laws] should protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.”

The minority in question was white male landowners, who presumably would be the only eligible voters and wield that power to defend themselves against the majority (everyone else). Interestingly enough, on this all-important question of suffrage — aka the franchise or voter eligibility — the original Constitution was silent, in effect punting the issue to the states under the Tenth Amendment. We’ll revisit the voter eligibility question more as the course proceeds because expanding suffrage is a key story in America’s evolution into a democracy.

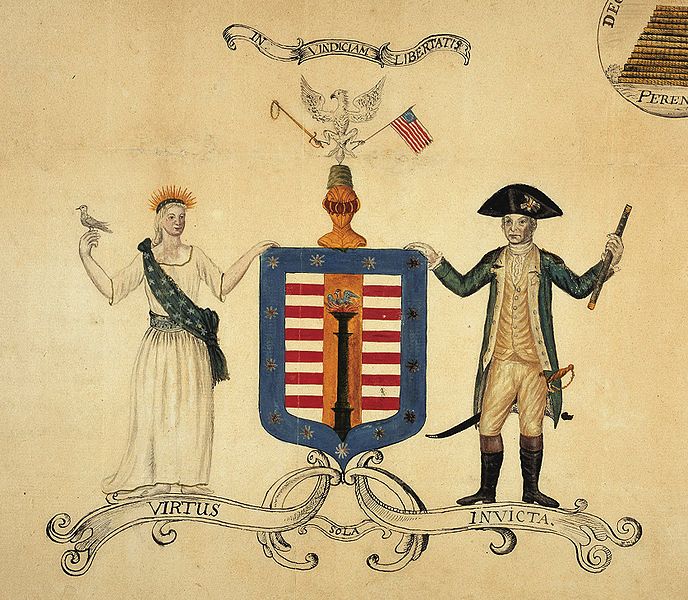

David Barton’s Design for the Great Seal of the United States Wasn’t Used, But It Is the First Appearance of an Eagle, U.S. Diplomacy Center, U.S. State Department

The Articles of Confederation weren’t revised in Philadelphia; they were torn to pieces and thrown in the trash straight away. No one mentioned canal building, the other supposed purpose of the 1787 meeting. Most opponents of a stronger national government, the Anti-Federalists, made the fatal mistake of boycotting the meeting (one notable exception was New York judge Robert Yates, who wrote newspaper editorials under the pseudonym “Brutus”). Their relative absence ceded initiative to the Federalists, so named not because they wanted to shift all the power to the national level, but because they wanted to federate by establishing a multi-tiered system of national, state, county, and city governments whereby they were united but still shared power. Dividing Founders into Federalists and Anti-Federalists is an oversimplification since most were somewhere in between and many Anti-Federalists supported some type of national government, just one weaker than what emerged. Likewise, most Federalists weren’t in favor of an overbearing centralized national government, but they wanted a stronger one than existed under the Articles of Confederation. The competing terms just describe which way Founders leaned in the debate over the power of the upper tier of government.

The word federal is often confused with meaning national government because today we speak of “Feds” like the FBI or IRS at the top level. It’s very confusing because to federalize is to shift power to the national level, but people often talk of federalism as emphasizing local control, in opposition to centralization. Self-styled American Federalists in the 1790s wanted more centralization, while Mexican Federalists later wanted less centralization. Technically, federal means SHARED power at different levels, variations of which you see in most countries. Adding a con prefix, as in to confederate, usually implies more decentralized power. The 2014 Encyclopedia Britannica defines federalism as “unit[ing] separate states or other polities within an overarching political system in such a way as to allow each to maintain its own fundamental political integrity.” In that way, Barney Fife, as deputy of fictional Mayberry, North Carolina on the Andy Griffith Show, was just as much a “Fed” as the Men in Black. Your local town and county and are part of the same overall federal system as the national government.

The shared federal system idea was already established under the Articles of Confederation, despite that government’s reputation for granting most power to the states. They still had a national tier grafted on top insofar as the states had formed a union and fought as a country. There was a Continental Army, Continental Congress and president of Congress. In 1787, the Founders wrote the new Constitution to strengthen the upper tier. The Federalists, representatives of the establishment in the eyes of their critics, felt the Revolution had gone too far in the democratic, decentralized direction and wanted more law and order. Noticeably absent in the new Constitution are the words liberty, freedom or democracy. The general feeling was that Jefferson might have poured a little too much fuel on the fire with the Declaration. It was time for the Spirit of ’87 to check the Spirit of ’76.

Their first agreement was to shutter Independence Hall — the same building in Philadelphia where that same Declaration was signed eleven years earlier — and agree that no one would talk to the press for the duration of their meeting. However, it was never their intention to ram the new government down Americans’ throats without citizens’ feedback. They just wanted to finish crafting the government in private, without too many people in their ears, and then turn it over to special conventions called in each state. Under terms the old Congress authorized, it would become the new law of the land if nine of the thirteen states agreed to it. In this way, they didn’t completely trash the Articles of Confederation, because they granted the old government the right to approve the transition toward a new government. Why not give it to the state legislatures directly instead of special conventions? Because the states had no motive to relinquish any power to a new national government when, under the Articles, they were pretty much in control.

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, Howard Chandler Christy, 1940, U.S. House of Representatives

While they kept no official minutes, we know from Madison’s journal and Robert Yates’ notes that the basic parameters of debate never left Madison’s original framework. While Madison can’t be trusted as an impartial source — and legal historian Mary Sarah Bilder has documented how he continuously revised his “notes” between the Convention and his death in 1836 — the final result was similar to his Virginia Plan. There was a three-tiered national government (executive, legislative and judicial) tied together by a system of checks and balances that left no one branch in charge of the other two. The remaining months were spent hammering out details like representation, the Electoral College, slavery, and the Bill of Rights. The term electoral college came later; the Constitution just mentions electors.

No one mentioned slavery until Benjamin Franklin introduced a Quaker petition calling for its abolition, that he’d signed as well. Southern states demanded that northern states figure out a way to deal with emancipated slaves, such as repatriation to Africa, but they’d prepared no such plans. Georgia and South Carolina threatened to stay out of the U.S. if slavery was abolished, just as they had with the Declaration of Independence. So it was not, and slavery’s legality is implicitly acknowledged at several points: the Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2) obligating Northerners to return enslaved runaways (strengthened in 1793 and 1850), the ban on Atlantic trading after 1808, and the infamous 3/5th Compromise allowing Southern states to count 60% of their black populations when determining their number of representatives. Contrary to popular perception, the South wanted to count their enslaved workers, not the North. That gave the South more senators, representatives, and votes in the Electoral College. The workers themselves were not counted as 3/5th of a person; they were counted as 0/5th of a person in terms of their own rights and citizenship. The South wanted to count enslaved people for representation purposes but not let them vote and got their way.

Historian David Waldstreicher wrote that the Constitution was “deliberately ambiguous but operationally pro-slavery.” Yet, critically — and this point is often overlooked at the expense of slavery’s indirect acknowledgement — the Constitution didn’t sanction or endorse slavery outright by enshrining it legally. This, too, was important going forward as the debate reignited before the Civil War. We saw earlier in this chapter how the Northwest Ordinance banned slavery north of the Ohio River. Subsequently, the majority of European immigrants flowed into free, northern territory as farmers or wage workers in the 19th century, increasing its population and countering the effect of the 3/5th Compromise. Also, the mostly effective 1808 ban on the Atlantic slave trade limited the number of enslaved workers. That triggered their forced migration to the south and west when cotton boomed and tobacco floundered, lessening their number in the Upper South which, in turn, made it easier for the Union to control slave states like Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware in the Civil War. In short, the Founders damaged slavery just enough to help the Union later win the Civil War in the 1860s and abolish slavery altogether. In the optional article below, historian William Freehling challenges readers to imagine a country where northern slavery and the Atlantic trade remained legal.

The states also reached a compromise on other aspects of representation. Small states wanted to continue the one-vote-per-state direct, or equal, method of representation used under the Articles of Confederation. Per Madison’s Virginia Plan, larger states (or small states that were growing) argued, logically enough, that their larger populations should get more votes. Why, today, should Wyoming have equal power with Texas, when Wyoming has only half the population of Travis County, Texas? Thus, one advantage of the bicameral legislature, with an upper Senate and lower House of Representatives, was that they could mix these two otherwise imperfect systems, with direct representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House. The idea was known as the Great Compromise, or Connecticut Compromise because its author Roger Sherman hailed from that state. Today Texas and Wyoming have two senators each, but Texas has 38 representatives in the House to Wyoming’s one.

The disadvantage of equal representation is that rural Americans have an increasingly out-sized influence in the Senate the more cities grow. According to Harvard political scientist Miles Rapaport, the U.S. is approaching a situation whereby 30% of Americans control 70% of the Senate seats. It’s understandable why the Founders mixed the two systems in the House and Senate, but since rural America is so overwhelmingly white, African-Americans have only 75% as much Senate representation as Whites and Hispanics only 50%. For perspective, consider that California, with 150 million residents, has two senators; both Dakotas and Wyoming, with ~ 1.5 million, had six senators. In those states 1% as many people have 3x more power in the upper house. This matter moved front and center in the early 21st century as rural, white evangelicals mobilized politically to defend what they sensed as encroachment from diversity and immigration on their quintessentially American identity.

Voting For Presidents: The Electoral College

The Electoral College, used to elect the president, also drew from this mix, with the total number of presidential votes (electors) from each state equaling that states’ combined number of Senators and Representatives (Article II, Section 1, Clause 2-3). Even countries that modeled their constitutions directly on the U.S. — Liberia, and post-war Japan and West Germany, for instance — dropped this undemocratic feature and a majority of Americans have opposed it throughout its history. Pennsylvania’s James Wilson wanted a straight popular vote but the leading framers opposed it. From the North, Alexander Hamilton opposed a popular presidential vote because of his general opposition to creating a democracy. In Federalist No. 68, Hamilton explained that, while “the sense of the people (voters) should operate in the choice,” electors would “most likely have the information and discernment” to make sure the candidate was qualified for higher office. Hamilton’s argument was reminiscent of the virtual representation argument the British had made to justify colonists not having representation in Parliament. The Virginian Madison, meanwhile, cynically argued that a popular vote would be unfair to the South because the North had more eligible voters since enslaved Southerners didn’t have the franchise. While the electoral college ended up favoring rural states, it especially favored rural states with a lot of enslaved workers because of the 3/5th’s compromise, enabling the South hold on to power for most of the 19th century. It paid dividends in the 1800 election, for instance, when Virginian Thomas Jefferson beat New Englander John Adams in the electoral college 73-65 (Chapter 12). On HBO’s Real Time With Bill Maher, the comedian asked of the Founders who created the electoral college, “what were they smoking?” On cue, columnist George Will replied “Virginia tobacco.”

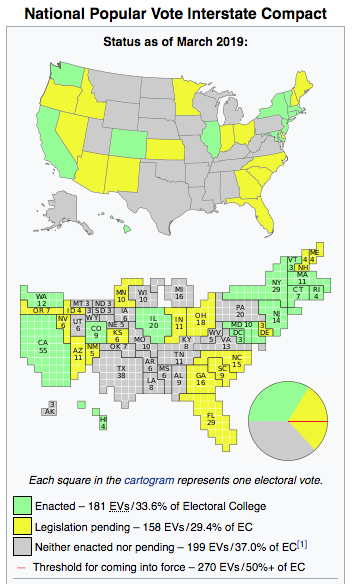

A popular vote for the presidency might have been impractical in the 1780s but could easily work today with quicker communications and no slavery factor. However, that’s proven impossible because it would require an amendment agreed upon by ¾ of the states. The smaller states would never agree to it because the current formula of figuring electors favors them. Adding senators to the total, which small states have as many of as big states (2), gives the small states a boost they would lose in a straight popular vote. Without the Electoral College, presidential candidates would skip the “flyover states” altogether and focus mainly on urban areas. Also, one party or the other is usually benefiting from the arrangement because it’s stronger in rural, less populous states. Today that’s the Republicans but it was Democrats a century ago. That party naturally doesn’t favor determining the president via popular vote. Currently, the Democrats endorse a Constitutional work-around plan called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact — whereby state electors pledge to cast their votes with the national popular vote winner rather than their state’s popular vote winner — but red-leaning Republican states haven’t signed on and the plan wouldn’t kick in until enough states agreed to gain the necessary 270 electoral votes (currently, they’re only ~ 66% of the way toward that goal, see map on right). As pointed out by former Republican National Committee chair Michael Steele, it’s likely near-sighted of his party to oppose the deal, though. If Texas “flipped blue,” for instance, Republicans would lose all the conservative votes there under the electoral college, just as they currently do in California and New York, because in most states it’s winner-takes-all. Because of their greater populations, there are likely more Republican voters in all the blue states (including California, New York, and Illinois) than all the red states combined minus Texas. In any event, it’s unclear whether a popular vote compact would hold up in the Supreme Court, though the Constitution grants states the right to handle their electors as they see fit (Article II, Section 1, Clause 2).

A popular vote for the presidency might have been impractical in the 1780s but could easily work today with quicker communications and no slavery factor. However, that’s proven impossible because it would require an amendment agreed upon by ¾ of the states. The smaller states would never agree to it because the current formula of figuring electors favors them. Adding senators to the total, which small states have as many of as big states (2), gives the small states a boost they would lose in a straight popular vote. Without the Electoral College, presidential candidates would skip the “flyover states” altogether and focus mainly on urban areas. Also, one party or the other is usually benefiting from the arrangement because it’s stronger in rural, less populous states. Today that’s the Republicans but it was Democrats a century ago. That party naturally doesn’t favor determining the president via popular vote. Currently, the Democrats endorse a Constitutional work-around plan called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact — whereby state electors pledge to cast their votes with the national popular vote winner rather than their state’s popular vote winner — but red-leaning Republican states haven’t signed on and the plan wouldn’t kick in until enough states agreed to gain the necessary 270 electoral votes (currently, they’re only ~ 66% of the way toward that goal, see map on right). As pointed out by former Republican National Committee chair Michael Steele, it’s likely near-sighted of his party to oppose the deal, though. If Texas “flipped blue,” for instance, Republicans would lose all the conservative votes there under the electoral college, just as they currently do in California and New York, because in most states it’s winner-takes-all. Because of their greater populations, there are likely more Republican voters in all the blue states (including California, New York, and Illinois) than all the red states combined minus Texas. In any event, it’s unclear whether a popular vote compact would hold up in the Supreme Court, though the Constitution grants states the right to handle their electors as they see fit (Article II, Section 1, Clause 2).

It’s a myth, though, that the popular vote doesn’t matter. Why? Because electors cast their ballots in favor of whoever won their state’s popular vote. Or, at least, usually they do. The Constitution doesn’t actually mandate that, but rather leaves it to the states to decide “in such a manner as the legislature thereof may direct” and, today, 17 states, including Texas, have no official requirement that electors vote for the popular vote winner in their state, and only nine states nullify votes that contradict that states’ popular vote. That’s why the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact might be theoretically legal, even if electors went against their own state’s popular vote. Still, as of 2016, there have been only 167 “faithless electors” in U.S. history, and they’ve never swung an election. 2016 was the worst year, with eight Democratic and two Republican electors refusing to vote for Trump or Clinton, respectively, instead casting votes for a variety of politicians and, in one case, Native American activist Faith Spotted Eagle. However, there were no faithless electors in 2020 and that year the Supreme Court confirmed that states could punish them, effectively outlawing it. After Trump tried to assemble alternate electors in states that he lost in 2020, Congress reached a bipartisan agreement in 2022 to refine and improve the 1887 Count Act (passed after the contentious 1876 election) to prevent future problems. The 2022 mid-terms included candidates that favored Trump’s Eastman Plan, which would’ve severed presidential elections from the people altogether by allowing partisan state legislatures to choose their own electors with no regard to the popular vote, but most of them lost. The Eastman Plan would’ve been radical indeed, insofar as it would’ve more or less ended America’s 231-year experiment in democracy, at least temporarily. Today, ~ 66% of Americans favor sticking with the Constitutional system whereby presidents rotate in via elections.

Two states today, Nebraska and Maine, vote proportionally based on their state’s popular vote, but it’s winner-takes-all “general ticket” in the other 48. In 2020, Trump won Nebraska overall but Biden got one vote for one district, and vice-versa in Maine. In the other 48, tens of millions of Americans are, in effect, shut out of meaningful presidential votes, including conservatives in California, Illinois, and New York and liberals and most minorities in big swaths of the Deep South, Great Plains, and Mountain West. However, if the U.S. switched to proportional electoral votes, states would have to allocate those by total votes rather than congressional districts, the way Maine and Nebraska currently do, because of heavily gerrymandered districts drawn up by dominant parties in their legislatures to maximize their prospects (more extreme today with sophisticated software). Had Maine and Nebraska’s system been in place nationwide in 2012, Mitt Romney would’ve defeated Barack Obama in the electoral college despite losing the popular vote by over five million. Nebraska is also the only state with a unicameral rather than bicameral legislature.

A candidate can’t win the electoral vote while losing the popular vote decisively but can when losing narrowly. Five times in American history the winner of the popular vote has lost the election: 1824 (Andrew Jackson), 1876 (Samuel Tilden), 1888 (Grover Cleveland), 2000 (Al Gore, Jr.), and 2016 (Hillary Clinton). But Clinton’s victory in the popular vote over Trump wasn’t that narrow at 2.1% (48.2 to 46.1) and Trump beat Clinton decisively in the electoral college, 304-227. Unsurprisingly, GOP voters’ support for the electoral college surged after 2016. If we continue with the electoral college, the future of the executive branch hinges disproportionately on Texas and which Texans vote. That’s why debates over immigration, polling station accessibility, and voter ID are so contentious there. But two of the reasons for having an electoral college instead of a popular vote — the difficulties of vote-counting before modern communication, and rigging the system in favor of slaveholders — are long since outdated.

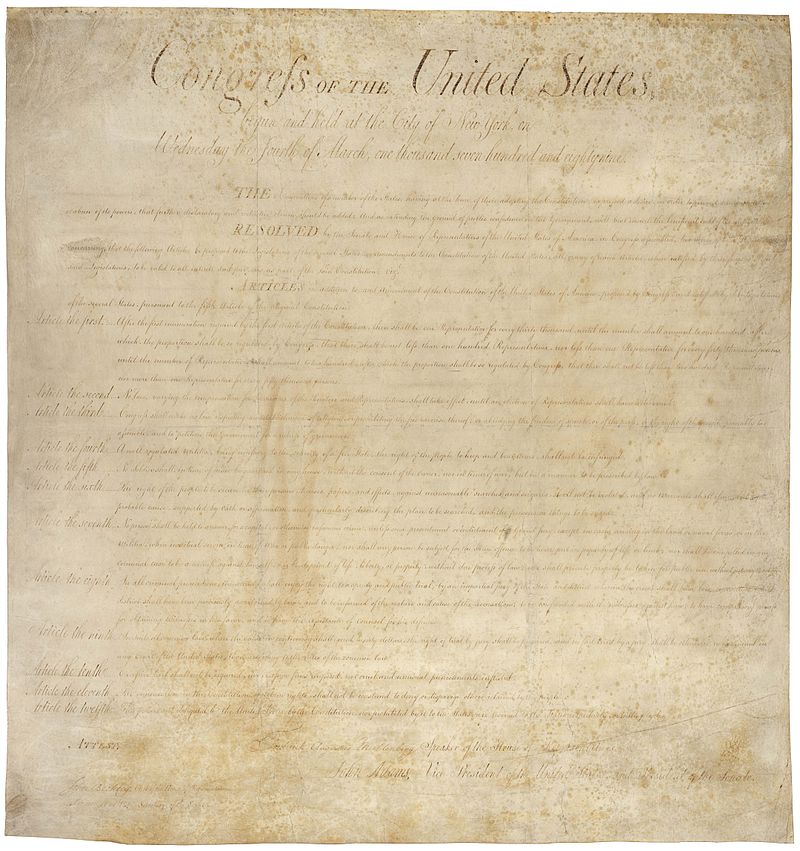

Amendments

Given all these disagreements and compromises and future uncertainty, it was wise to include a provision to tweak the Constitution. The amendment system, borrowed from Pennsylvania’s state constitution, gave the government the ability to change and adapt to new circumstances without scrapping it and starting over. Two-thirds of either Congress (both houses) or the states can propose an amendment and ¾ of the states (either legislatures or special conventions) are required to ratify the amendment. Without this feature, the Constitution would no longer be around. The U.S. is not the oldest country, but their written constitution is the oldest among major countries and amendments are partly why. An amendment changing presidential elections to a popular vote has failed over 800 times, though, constituting ~ 10% of all failed amendments.

Pinckney’s Plan

One of the reasons we think of James Madison as the main Constitutional architect is that his journal is one of the few direct primary sources. But we know from piecing together letters written years later by conventioneers, including Anti-Federalists, that Madison shortchanged South Carolinian Charles Pinckney in his account (the two later faced off in the 1808 presidential race). Madison mentioned that Pinckney brought a plan with him to Philadelphia but didn’t elaborate on the details. Pinckney’s role is controversial, and Madison and others vehemently downplayed it, but most historians think that he and Pennsylvania’s James Wilson were more responsible than anyone in shaping Article II, the portion of the Constitution dealing with the presidency. Historians found Pinckney’s Plan in Wilson’s papers. When Wilson proposed having an individual run the executive branch, Randolph of Virginia accused him of inserting into the Constitution the “foetus [fetus] of monarchy.” Keep in mind, though, as we learned in Chapter 8, that many colonists had been upset with King George III not for being too strong, but rather for being too weak in protecting them from Parliament. The long-winded, 30-year-old Pinckney, a Revolutionary War veteran and POW, argued for using Roman terms like president and senate, for establishing a procedure to get rid of unlawful presidents via impeachment and trial, and for requiring the executive to deliver periodic State-of-the-Union updates to Congress. Pinckney also pushed through the Fugitive Slave Clause (not expunged until the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery) and a line in Article 6 that exempted public figures from any religious test — a radical departure for the time that distinguished the U.S. from European countries. Unlike the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution didn’t claim to derive its justification from a higher power.

Pinckney also wanted the president to run the military as Commander-in-chief, but that the president could “neither raise nor support forces by his own authority.” Presidents have varied widely in how hands on they were in working with military planners during wars. Abraham Lincoln, for instance, was hands-on during the Civil War with the aid of the telegraph. Harry Truman, though, wasn’t entirely in charge of where the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Japan at the end of WWII, or necessarily even whether it happened in the first place. Pinckney, George Mason, and others also pushed for a feature that’s easy to overlook now but was critical to the country’s power structure: putting the military in the hands of the newly invigorated national government rather than the states. Pinckney wanted “no states to keep a naval or Land Force militia,” for Congress to “regulate militia throughout the country” and appoint war officers, and for the Secretary of War to be housed in the executive branch. Article 1, Section 10 of the final draft reads:

“No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.”

Militaries & Second Amendment