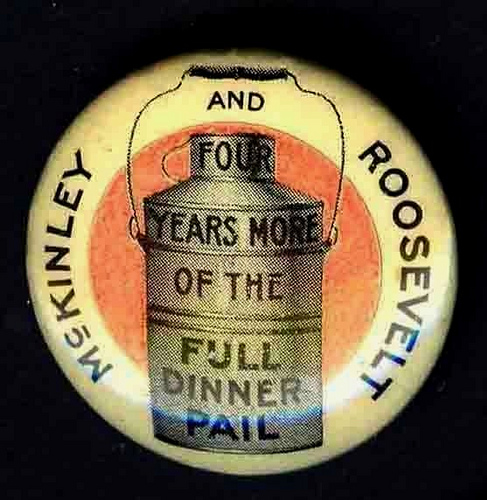

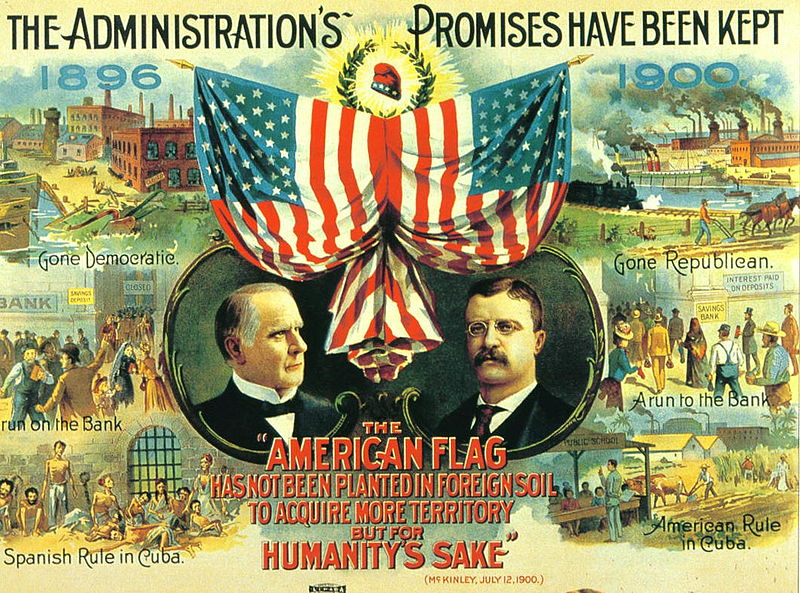

1900 McKinley-Roosevelt Campaign Poster Showing That Expansion During the Spanish-American War Created Jobs in Industry & Farming

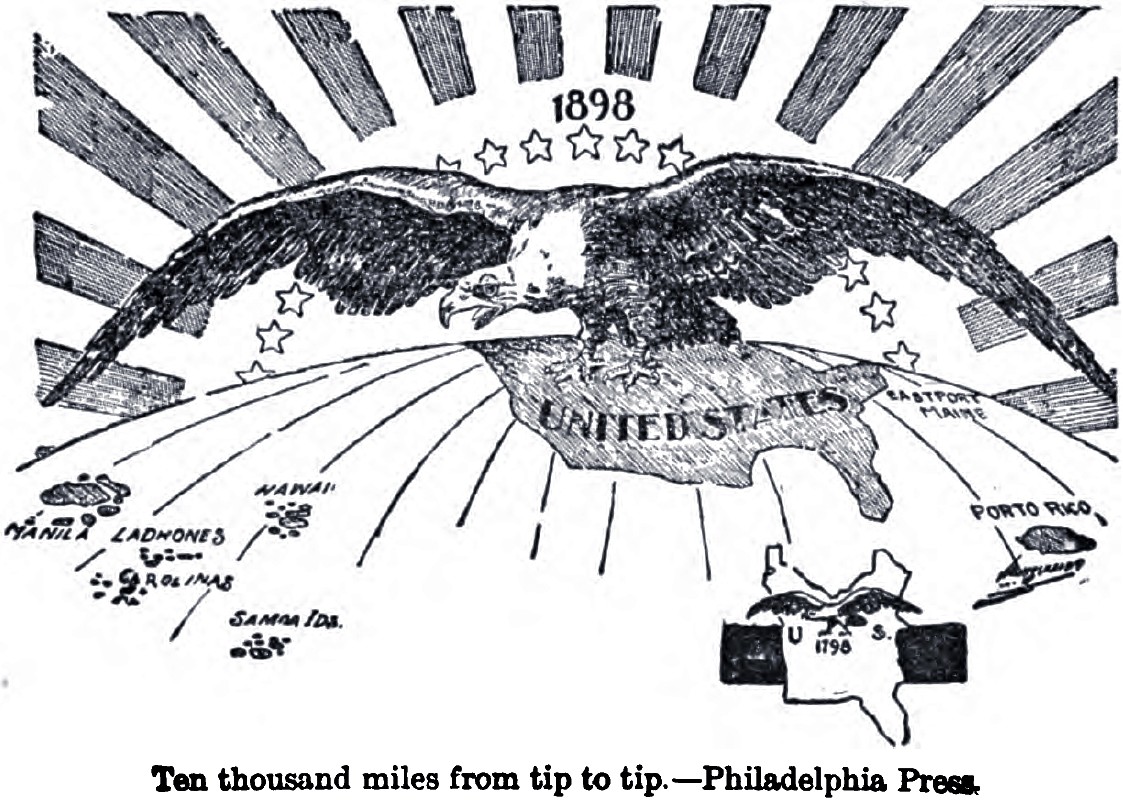

One interesting thing about America’s 19th-century Pacific expansion is that it happened during, and even before, its more famous western settlement. American missionaries and sugar planters were in Hawaii in the 1820s, a generation before the California Gold Rush or Mormon Trek to Utah. The reason is that, while oceans can be deadly in strong winds, water is normally easier to traverse than land — even the long and torturous pre-Panama Canal sea route around Cape Horn from the East Coast to the Pacific. By 1890, when the Census Bureau declared the western frontier closed, the U.S. had already laid claim to territory in the Pacific. By 1902, America controlled Hawaii, Alaska, the Philippines, Guam, Midway Island, part of Samoa and several smaller islands in the Pacific (e.g. Palmyra Atoll and Wake, Jarvis, Howland, and Baker Islands). Since its revolution and initiation of the Old China Trade routes starting in 1783, the U.S. coveted trading with Asians the way it had traditionally with Europeans. It signed a trade deal with Siam (now Thailand) in 1833 that’s still in place. In the 1850s, Commodore Matthew Perry sailed the U.S. Navy to China and Japan to increase trade in East Asia. By the turn of the 20th century, America was digging a canal shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific and was in combat defending its interests in Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. In this chapter, we’ll cover why and how America stepped out onto this world stage.

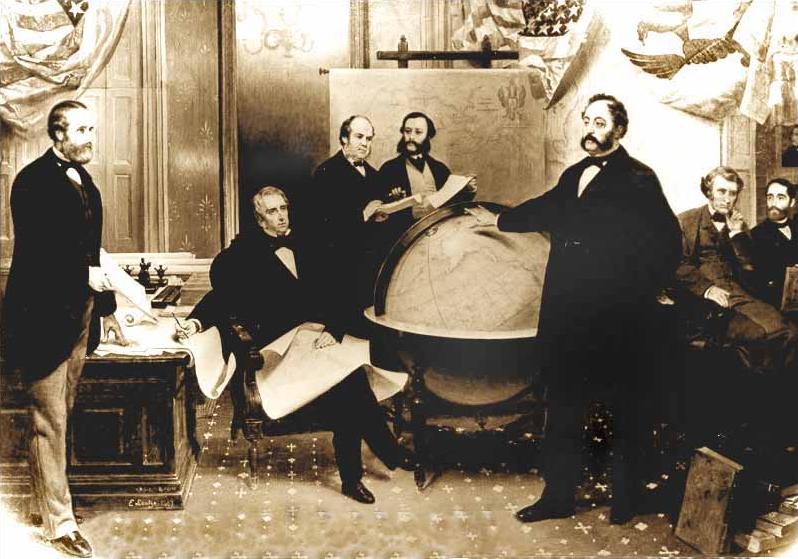

Closer to home and earlier, the United States was expansionary throughout its history, displacing millions of Indigenous Americans. The U.S. declared hegemony over the Western Hemisphere in the 1820s with the Monroe Doctrine, acquiescing in existing Spanish and Portuguese territories for the time being, but vowing to preclude any further colonization by any foreign power. The U.S. had control of Mexico at the end of the Mexican War in 1848 but voluntarily relinquished the country’s bottom 45% mainly because Congress didn’t want to integrate millions of Hispanic Catholics into its population. The U.S. tried twice to conquer Canada, once in 1775 (as Continental Congress) and again during the War of 1812. As the 19th century wore on, only industrialists kept the Canadian idea alive; neither the government nor public had much appetite. That prospect reemerged when the U.S. acquired Alaska in 1867, but Canada extended to the Pacific by acquiring British Columbia and building a transcontinental railroad, completed in 1885. When Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Seward, purchased Alaska from Russia, some critics derided him for wasting $7.2 million on an iceberg; “Seward’s Folly” they called it. But the U.S. spent around 2¢/acre for an area roughly 1/3rd the size of the Lower 48 that later yielded gold, oil, and fishing, to say nothing of its natural beauty and parks. Alaskans are fond of saying that, if Texans feel bad about living in the second-biggest state, they could split Alaska in half so that Texas is third. Put another way, Russia once controlled 20% of the current United States. Settler colonialism or imperialism define aspects of all domestic American history, but here we’ll examine U.S. expansion outside the Lower 48 during the Gilded Age.

Manifest Destiny

Overseas expansion forced America to confront conflicting sides of its collective personality — one championing self-determination, the right of people to rule themselves — rooted in its own emancipation from British rule in the late 18th century; the other based on its own sense of mission to spread its way of life and need for economic growth.

Nineteenth-century expansion played out under the ideological cloak of Manifest Destiny, the belief that God destined white Protestants to dominate inferior Indians, Mexicans, and Asians. Senator and historian Albert Beveridge said, “God has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man.” His message echoed a sense of mission and prerogative that traced back to 17th-century Puritans, and one that resonates among some today as a component of American Exceptionalism, though that idea means different things to different people. While religious nationalism might sound chauvinistic by today’s standards, keep in mind that most powerful empires have believed that God liked them better than others. That’s how Rome saw itself in antiquity and how imperial Japan and Germany viewed expansion in the 1930s. Fifteenth-century Catholic Iberians proclaimed their right to conquer everyone on Earth not ruled by a Christian sovereign in the Discovery Doctrine. Similar notions held true for the more restrained United States in the 19th century. Manifest Destiny is most famously associated with America’s spread across the American frontier, but the same hopes and ambitions projected simultaneously across the Pacific Ocean. Senator Beveridge’s comments came during America’s Philippines conquest in 1900.

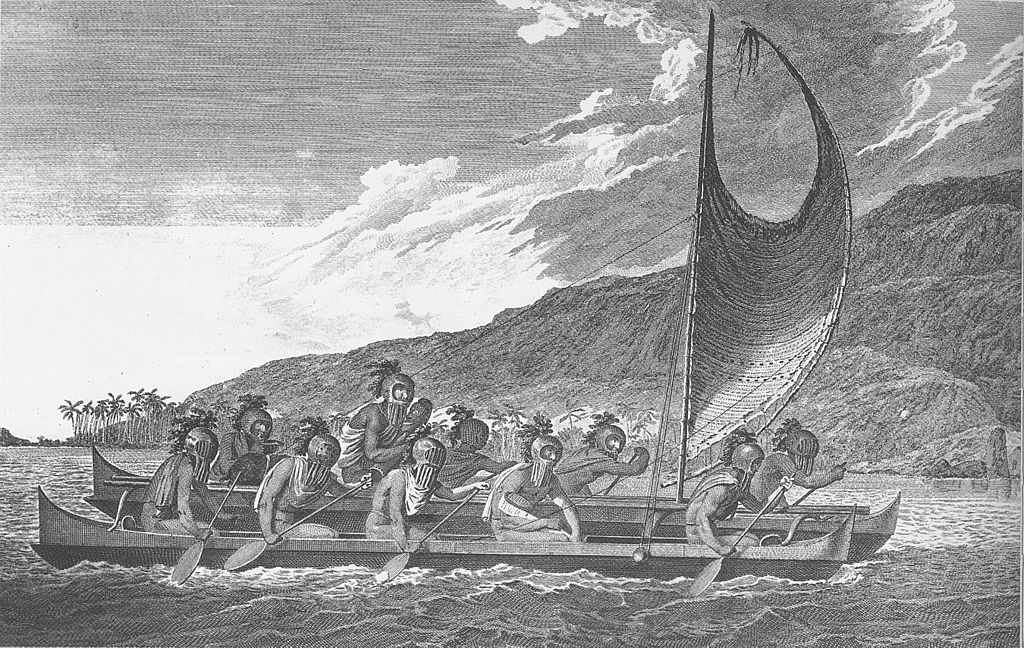

Hawaiians In Double-Hulled Canoes Greeting Cook’s Expedition In Kealakekua Bay (Big Island), John Webber, 1781

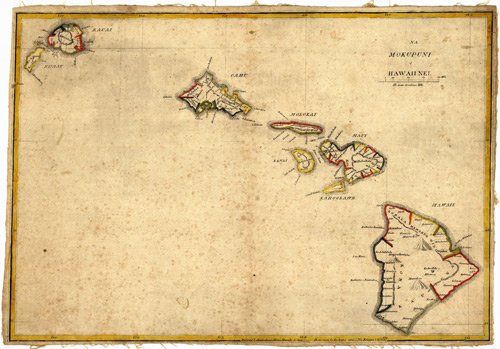

Hawaii

With their expert knowledge of currents, stars, and wind, Polynesians from Marquesas and Raiatea migrated to the Hawaiian Islands in double-hulled voyaging canoes (outriggers or catamarans) sometime around 500 CE. They brought with them the fishing and farming techniques, language, religion, social hierarchy, tools, and canoes common to what’s now French Polynesia. Another wave from Bora Bora and Tahiti settled in the 11th century. Following the same currents, British explorer and naval captain James Cook visited Oahu and Kauai in 1778 on his Third Voyage. Some Dutch and Spanish ships might have visited Hawaii before the British, but Cook’s crew were the first Europeans to make an impact on the indigenous population, at least that we have record of. But the Hawaiian term Haole, for outsider, predates Cook, who named the Sandwich Islands for his patron, Lord Sandwich. Returning from the Pacific Northwest later that year to Maui and the Big Island (Hawaii) — this time during a military exercise rather than religious celebration — Cook, four of his men and 17 Hawaiians were killed in Kealakekua Bay when Cook tried to kidnap and ransom a chief in a dispute over a stolen lifeboat.

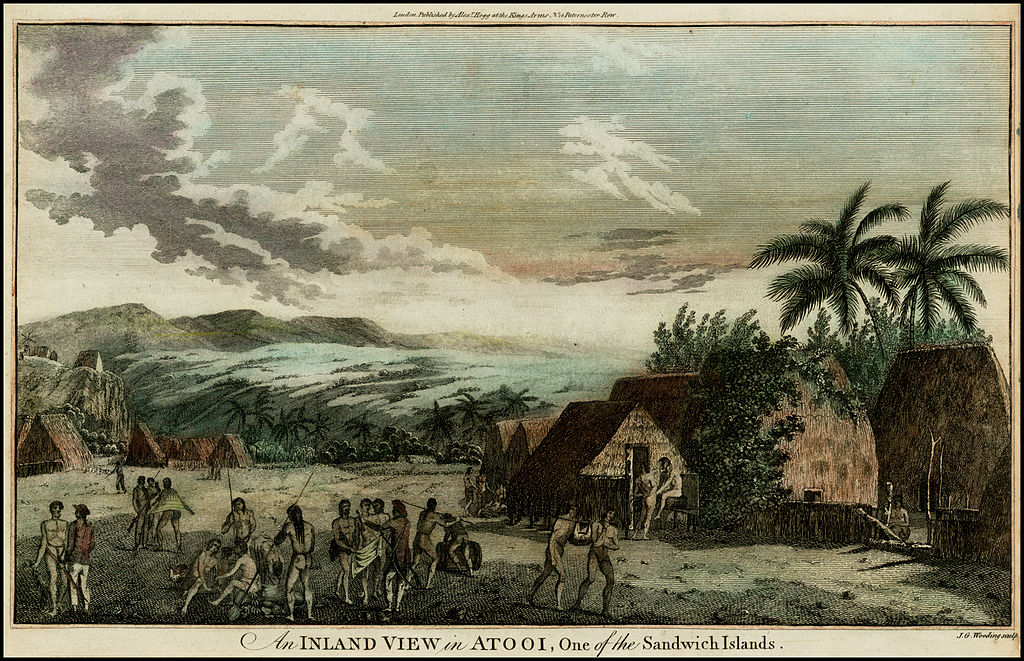

Lithograph Of Village Visited By Captain James Cook Near Waimea, Kauai, Based On 1778 Etching By John Webber, WikiCommons

Other Europeans, including Russians based out of Sitka, Alaska, followed for whale hunting, pineapples (especially on Lanai), and sandalwood for perfumes/cosmetics, medicine, and furniture. New England merchants, whose trade with Europe was disrupted by the War of 1812, sailed around South America, traded and hunted for sea-otter furs in the Pacific Northwest, swapped guns and iron tools to Hawaiians for pork, salt, freshwater and sandalwood, then traded sandalwood and sea-otter furs to China for porcelain, silk, and tea. Hawaiian chiefs used the guns to consolidate their power and fight each other and to control the common “callous backs” responsible for sandalwood lumbering.

Samuel Ruggles Was Among the First Groups of Missionaries in 1820 and Pioneer of Kona Coffee, Hawaii Gazette

By the 1820s, American planters grew coffee in the Big Island’s Kona district, with its nutrient-rich volcanic soil, and sugarcane elsewhere. Hawaiians felt Manifest Destiny’s impact when Protestant missionaries from New England led by Hiram Bingham I and Asa and Lucy Goodale Thurston set out to convert Hawaiians to Christianity, build schools, teach concepts of land ownership and money, and transfer the native language to writing, including the word Owhyee [Hawai‘i]. They discouraged nudity, hula dancing, religious music, polygamy, and even surfing because they saw all sports as a waste of time. Eventually, they even outlawed the native language they taught Hawaiians to write.

After struggling initially to develop the right technique, planters developed a sugar export economy to rival Cuban production. However, Americans, British, and Europeans (French, Germans, Russians) accidentally brought diseases that ravaged the Hawaiian population, including tuberculosis, STDs, measles, mumps, influenza, and smallpox. What transpired next was less a direct conquest than a messy, drawn-out economic and demographic infiltration complicated by the Hawaiian monarchy’s greed and manipulation of Hawaiians. The end effect, though, was simple if mostly bloodless conquest by Americans. While it’s impossible to ever nail down counterfactual history, it’s safe to say that Hawaii wouldn’t have remained independent without the American takeover, as either Britain or Japan likely would’ve colonized them.

King Kamehameha I united the islands in 1810 and, in 1839, Kamehameha III reformed Hawaii’s traditional regime into a constitutional monarchy with a Bill of Rights, similar to England’s. Hawaii was a sovereign nation with a parliamentary democracy and ambassadors to 150 nations. Kamehameha III’s Great Māhele intended to modernize the feudal land system in such a way that indigenous Hawaiians would retain rights to one-third of all property with the royalty retaining the other two-thirds. The policy failed as the aristocracy sold off land to Americans and commoners failed to file the proper claims. Foreigners ended up with most land. The growing U.S. provided a nearly insatiable sugar market, especially when the Civil War cut off California from the South and Cuba. Planters weren’t competing against each other for a limited export market because there was more than enough market to share, so they cooperated in building infrastructure and irrigation ditches, etc. Hawaiians lost more and more land as the Hawaiian crown became indebted to the sugar planters. Planters insourced workers from China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, and the Portuguese islands of Madeira and the Azores. A handful of Mexican vaqueros tutored Hawaiians in cattle ranching. The beleaguered Hawaiian population shrank rapidly in the mid-19th century and many young men left as sailors or to hunt whales or mine gold in California.

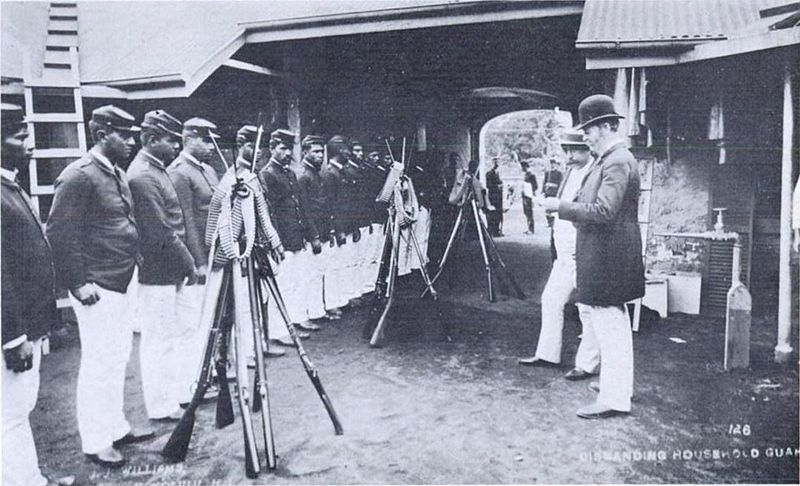

The Bayonet Constitution of 1887 forced David Kalakaua’s monarchy to capitulate most of its power to sugar planters, virtually turning him into a figurehead. The constitution granted the franchise to property owners (mostly white) but disenfranchised most Hawaiians, Chinese, and Japanese. King Kalakaua had revived traditions like hula dancing and surfing and, according to missionaries and planters, mismanaged finances. After the Bayonet Constitution, the British pretty much gave up any hope of taking over and ceded power to American planters, with “Uncle Sam” promising “John Bull” (British) trade access. King Kalakaua died in 1891, passing what monarchical power was left to his sister, Queen Lili’uokalani.

Rather than simply taking over the islands, Americans had (cynically?) helped transform feudalism into a constitutional, western-style monarchy for indigenous Hawaiians and then overthrew it in the “Spirit of ’76,” complete with declarations and committees of safety like those colonial British Americans wielded against the British in the 1770s. This charade climaxed in 1893-94 when rebel “Honolulu Rifles” backed by Marines and led by U.S. Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom John L. Stevens, Lorrin Thurston, and Sanford Dole of the famous Dole pineapples overthrew Lili’uokalani and created a republic with Dole as president. They allowed Hawaiians who pledged allegiance to the new regime to vote along with naturalized citizens (mainly Americans). Outgoing U.S. president Benjamin Harrison hoped that, with these qualifications in place, they might vote on a constitution so the coup would have some “semblance of having been the universal will of the people.” It was illegal, by American congressional law, for the U.S. to simply conquer other sovereign nations that it wasn’t at war with. The Provisional Government left the Hawaiian monarchy in place for purely ceremonial purposes.

Newly-elected president Grover Cleveland disapproved of the coup, but the junta (provisional republic), while led by Americans, didn’t initially answer to the United States and refused his order to stand down. But hadn’t Minister Stevens and U.S. Marines helped them overthrow the Queen? Historian James Haley notes: “The Junta’s conscience was untroubled by the irony that they had provoked American [military] intervention by pleading that their American lives and property were in danger, but now proclaimed for themselves this new national Hawaiian identity in order to tell the United States to get lost.” In keeping with their Spirit of ’76 spin, the Queen was purportedly overheard vowing to behead the rebels. The image of a Polynesian woman beheading white American businessmen, though likely fake news, played into the pro-annexation crowd’s hands in Washington, D.C. Moreover, rebel-supporting congressmen outnumbered Cleveland, who was a friend of Lili’uokalani’s. President Cleveland also didn’t realize at first that, during the coup, Lili’uokalani actually capitulated to the United States, not the Honolulu Rifles (Britain and France had taken over temporarily in the past when their subjects had tried to overthrow the Hawaiians).

American annexation wasn’t a foregone conclusion. The Hawaiian Patriotic League (Ka Hui Hawaii Aloha ʻĀina), composed eventually of native Hawaiians, successfully lobbied the Senate to oppose incorporation into the U.S. from 1893-1897, but the context of the unfolding Spanish-American War foiled their efforts (more below). Motivated by America’s need for a mid-Pacific fueling station, President William McKinley signed a congressional joint resolution — requiring only a majority vote instead of 66% required for a treaty (of annexation) — and the U.S. annexed the islands in 1898. Hawaii became a U.S. territory in 1900, with Dole as its first governor. By then, the Navy coveted the port at Pearl Harbor, Oahu that planners hoped would help the U.S. protect its Asian interests. Native Hawaiians later helped petition to make Hawaii a state in 1959.

In 1993, a century after the overthrow, Congress and President Clinton issued the Apology Resolution, formally recognizing that the U.S. overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom. Today, indigenous residents commemorate the pre-American era with the ‘Onipa’a (“steadfast”) celebration, named after a song Lili’uokalani wrote in captivity. Native Hawaiians are divided over whether they’d like to seek independence from the United States. Hawaii has the strongest economy in Oceania and one of the highest standards of living in the world.

Japan & Korea

Further west, the U.S. had no pretensions of taking over Japan the way it gradually had Hawaii. As mentioned above, the U.S. fleet of four warships under Matthew Perry sailed into Edo Harbor (Tokyo) in 1853 more in search of trade than territory. They also hoped for access to ports-of-call and to build coaling stations for the steamships Japanese called the “giant, dragons puffing smoke.” Given the language barrier, there wasn’t much dialog at first other than the unspoken gunboat message. Perry presented a letter (in English) from President Millard Fillmore requesting that Japan open its ports for trade and returned in 1854 with more ships. But the respectful tone of Fillmore’s letter contrasted with the intimidating white flag of surrender Perry handed them to raise in 1854, with the seeming implication of war if they didn’t comply with America’s trade and port access requests.

Japanese were divided amongst themselves during the Bakumatsu era of transition and factionalism between traditional shogunate rulers and ishin shishi that wanted to expand through more Western-style imperialism. The island had been mostly closed off to the outside world for centuries, other than a small island port at Dejima opened to Dutch trade and a brief period of Portuguese occupation in Nagasaki, from 1580-87.

Gasshukoku suishi teitoku kōjōgaki (oral statement by the American Navy admiral). A Japanese print showing three men, believed to be Commander Anan, age 54; Perry, age 49; and Captain Henry Adams, age 59, who opened up Japan to the West. The text being read may be President Fillmore’s letter to Emperor of Japan. Library of Congress

Perry’s arrival ignited anti-foreign sentiment that complicated things further. Leaders didn’t want a repeat of wars with Western powers that plagued 19th-century China (more below), so they complied and representatives of Tokugawa’s Shogunate reluctantly signed the Convention of Kanagawa, or U.S.-Japan Treaty of Peace and Amity, the terms of which historians in the respective countries dispute to this day. The upshot was that, through the implied threat of blunt force, the U.S. gained trade access at Shimoda and Hakodate and built a new consulate (embassy), but didn’t establish any of its own ports, and never attacked or tried to colonize. Japan also opened diplomatic relations with Britain and Russia. The Japanese Meiji (Restoration) Government that seized power in 1868 embraced Western science and technology they’d learned from the Dutch and favored more international trade. They argued that modernizing would prevent Japan from being partitioned by Europeans like eastern China.

American policy toward Korea’s isolationist Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897) followed a similar pattern to nearby Japan insofar as the U.S. wanted to initiate trade without conquering any area. However, things got more violent there in 1866 when Korea destroyed an American merchant steamer for coming too close without permission. The U.S. didn’t respond immediately, but sent a small fleet of warships in 1871 that Koreans fired on from a shore battery. In the Shinmiyangyo ten days later, U.S. forces invaded Ganghwa Island (near present-day Seoul), capturing several forts and killing 243 Koreans. The two nations weren’t on speaking terms for another decade as Joseons reaffirmed their isolationism. Eventually, Japan forced Korea to open its ports to trade, after which the U.S. signed the 1882 Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation that lasted until Japan conquered Korea in 1910.

Sea Power

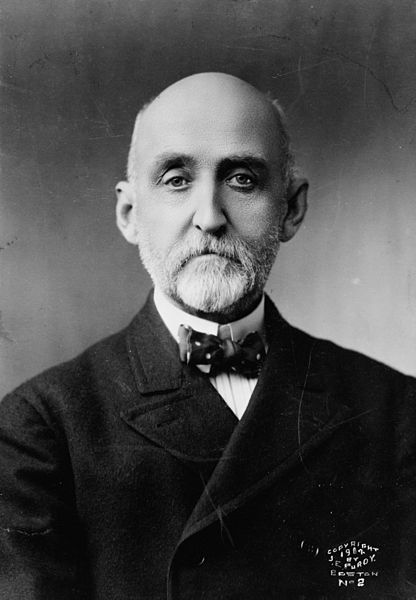

Foreign policy always connects to the domestic economy, as the late 19th century illustrates. America’s annexation of Hawaii and expansion into the Pacific connected to a major recession, the Panic of 1893. While the downturn had multiple immediate causes (stock market crash, run on gold, collapsing wheat prices, railroad bubble, etc.), it was increasingly apparent that the U.S. was a victim of its own success, out-producing its own needs in both farming and manufacturing. Some domestic markets were glutted or saturated, with production outstripping consumption, and others feared their sectors were trending in the same direction. What the U.S. needed was access to overseas markets and William McKinley (R-OH) won the 1896 election for the GOP by promising farmers and factory workers foreign markets, as we saw at the end of Chapter 2. And the president delivered, as advertised in the re-election campaign poster at the top of this chapter. In 1900, he offered those same blue-collar workers a “full dinner pail.” McKinley, his Assistant Navy Secretary, Theodore Roosevelt, and Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair Henry Cabot Lodge were all followers of retired admiral Alfred T. Mahan, president of U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, who wrote on the importance of sea power to America’s future. Updating Manifest Destiny to Hawaii, Mahan wrote: “In our infancy, we bordered on the Atlantic only; our youth carried our boundary to the Gulf of Mexico; to-day maturity sees us upon the Pacific. Have we no right or call to progress in that direction?”

Market access required a strong Merchant Marine, which required a strong Navy, which required distant harbors for maintenance, laying in supplies, and refueling and access to key canals and chokepoints, or bottlenecks. Navies and merchant fleets needed access, for instance, to the Suez Canal and Straits of Hormuz (Persian Gulf) and Malacca (Southeast Asia). Mahan advised that the U.S. attain Caribbean islands like Puerto Rico and Cuba to defend a canal that it would build across the Panamanian Isthmus to connect its Atlantic and Pacific navies. Such considerations also motivated the U.S. to acquire Hawaii and access to overseas harbors in Asia and Latin America.

Economic power is only as good as the strength used to protect one’s interests, as British history demonstrates. How did the small island of England become the most powerful country in the world, with territories in Canada, the Caribbean, Australia, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia? Aside from pioneering the Industrial Revolution at home, their Royal Navy ruled the waves. The British had naval superiority and were willing to assert influence over foreigners by subjugating them and building up their infrastructure. It’s been thus since controlling the Dardanelles and Bosporus gave Greeks and Romans access to Ukrainian wheat in Classical times and continued through the Venetians, Genoese, Dutch, Portuguese, and British in recent centuries.

By 1900, the British dominated global banking, finance, and insurance. London traders speculated on items they’d often never seen or felt, including South African gold, Malayan tin, Australian wool, Indian cotton, Jamaican sugar, Argentinian railroads, and even Peruvian guano for fertilizer. They transplanted Brazilian rubber trees to Malaya to support British Industry. As we’ll see below, their biggest racket was importing Indian and Afghan opium into China, against the Chinese government’s will. It all started with the Royal Navy. Maritime power is still important today since important dry commodities and oil can only be moved by ship, being too bulky for planes.

You can see the utility of racism in sea power’s 19th-century application and the British had plenty of it, but it was incidental to economic concerns. Other European powers did the same, if not quite as effectively. The 19th century saw the great Scramble for Africa, whereby post-Napoleonic Europeans carved up an entire continental map (other than Liberia and Sierra Leone, settled by expatriated enslaved Americans), while simultaneously ramping up colonization in the Middle East and Asia. Competition in Central Asia (e.g. Afghanistan) was especially tight between Britain and Russia in the so-called Great Game. All this incurred hostility among local populations that carries over to today. In 1800, Caucasians controlled around 35% of world land; by 1900, that figure jumped to 85%. Much of the change was in Asia. Not only did Brits control Burma, Malaya, Hong Kong, and parts of Shanghai, the Dutch held Indonesia and the French held Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) and shared Shanghai with the British, Americans, and Japanese. Take a minute to look at this map to see the extent of colonization dating from the Age of Exploration.

Theodore Roosevelt in Hunting Suit and Tiffany Hunting Knife and Rifle, Photographed by George Grantham Baine, NYC, 1885

Teddy Roosevelt

McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt, who succeeded him as president when McKinley was killed in 1901, both wanted to expand America’s military and commercial horizons overseas. Roosevelt was a product of his era, modifying Manifest Destiny idealism with a version of Social Darwinism. While Charles Darwin didn’t coin the phrase survival of the fittest, Social Darwinists thought that the idea was implied in his theory of natural selection and used it as an excuse to rationalize policies aimed at victimizing the weak. Roosevelt didn’t take it that far domestically and did much to champion the poor’s cause later in his career. But, internationally, he saw history as a biological struggle between races and expected Whites to come out on top. If you combined Manifest Destiny and Social Darwinism, that was how both God and nature wanted it.

Roosevelt was asthmatic as a child, grew more robust as a teenager, and set out west to the Dakotas as a young man for a life of ranching and hunting. Overhearing his parents say he’d probably die young of asthma motivated him to engage in relentless activity throughout his life. Unlike almost anyone who lived through or after the 20th-century world wars, Roosevelt saw war as a healthy enterprise, necessary to keep young males toughened up. He dreamt of war with Germany (though no clear reason had emerged yet) or perhaps with Britain to liberate Canada. He was a jingoist through and through who, true to his word, relished an opportunity to prove his own mettle on the battlefield. That gave Roosevelt the chance to one-up his father, whom he admired but who’d bought a draft exemption during the Civil War. To his credit, Roosevelt resigned his post as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1898 and enlisted when that opportunity for combat arose.

![Manuel Cuyàs Agulló, The Disembarkation of American Troops in Ponce [Puerto Rico], July 27, 1898 (1898) Manuel Cuyàs Agulló, The Disembarkation of American Troops in Ponce [Puerto Rico], July 27, 1898 (1898)](https://sites.austincc.edu/caddis/wp-content/uploads/sites/106/2015/08/Agullo-DisembarkationAmericanTroops.jpg)

Manuel Cuyàs Agulló, The Disembarkation of American Troops in Ponce [Puerto Rico], July 27, 1898 (1898)

Roosevelt’s chance came during the Spanish-American War of 1898. Spain had already lost many of its colonies and, by the late 1890s, was losing its grip on Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Americas and the Philippines and Guam in the western Pacific. The U.S. did a lot of business in Cuba and, initially, wasn’t as concerned with who controlled it as with avoiding any trade disruption and protecting its own interests. Twice during the 19th century, the U.S. offered to buy Cuba but Spain spurned their offers. Spain grew increasingly repressive as they struggled to keep down a Cuban uprising, though, and American public opinion turned in the rebels’ favor, embracing the cause of Cuba Libre! Up until his death in 1895, Cuban refugee José Martí organized rebels in Key West, Florida and among cigar workers at Ybor City, in Tampa. Having personally seen the bodies piled up at Antietam during the Civil War, President McKinley didn’t favor war, and the impatient Teddy Roosevelt complained that the president “had the backbone of a chocolate eclair.”

While the role of Yellow Journalist newspaper owners like William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer stoking the war flames has been overrated, eventually McKinley realized the Cuban conflict was an excellent pretext to acquire all of Spain’s territories in the Caribbean and Pacific. It fit perfectly with McKinley’s 1896 campaign promise to expand markets. This was an ideal case where the U.S. could stand up for freedom and expand its empire simultaneously. The penny presses weren’t inconsequential either. Hearst and Pulitzer inundated their readers with fake news and propaganda, including claims that Spain fed its POWs to sharks, and Hearst enlisted a New York Journal reporter to break Cuban rebel Evangelina Cosio y Cisneros out of jail and escort her to New York for a parade and sold-out event at Madison Square Garden. Hearst pressured McKinley and brazenly crowed in his paper’s masthead, “How Do You Like the Journal’s War?”

Then the USS Maine blew up in Havana Harbor, killing 266 American sailors. No one realized at the time that the boiler just exploded accidentally and the press and public naturally blamed the Spanish. Spain wasn’t a likely candidate in retrospect because they wouldn’t have wanted to lure the U.S. into the war and one of their cruisers, the Vizcaya, was due to dock in New York days later. Cuban rebels hoping to frame Spain or American journalists creating a sensational story would’ve been more likely suspects than the Spanish but, in any event, it was an accident. Suspicious of their fellow Americans’ intentions, Congress only authorized war with an amendment ensuring that the U.S. didn’t use the uprising as an excuse to take Cuba for itself.

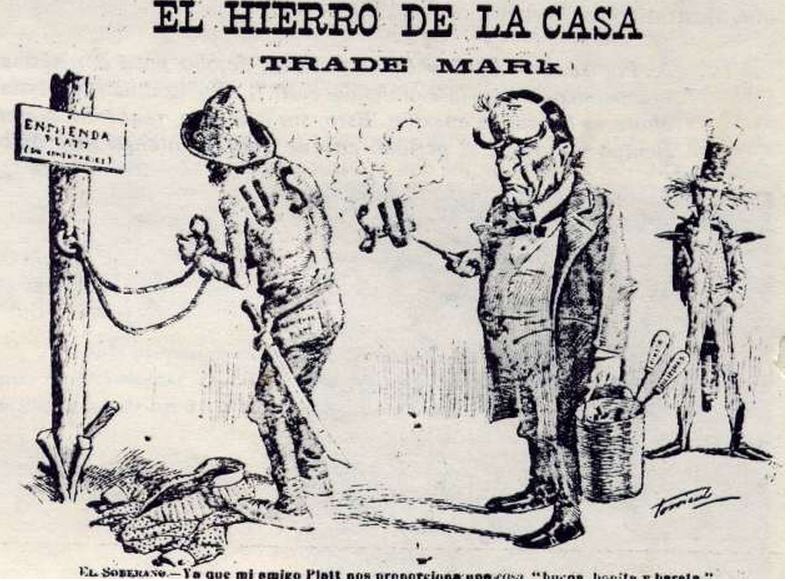

After the “Splendid Little War,” in which fewer Americans died from combat than from eating spoiled canned meat, the U.S. made Cuba a protectorate. When most Americans envisioned fully freeing the Cubans, they hadn’t realized that most rebels were black. American Commander William Rufus Shafter said, “These people are no more fit for [self-] government than gunpowder is for Hell.” In effect until 1934, the Platt Amendment allowed Cuba nominal self-rule, but the U.S. siphoned export profits, built military bases on the island, including Guantanamo Bay, and maintained control over Cuba’s choice of leadership. Simply put, the U.S. set up a puppet state in Cuba that was friendly to its interests. They dismantled Cuba’s three main representative political parties in 1899. The poster at the top of this chapter, an instructive primary source, shows the McKinley administration’s pride at having put Cuba under “American rule.”

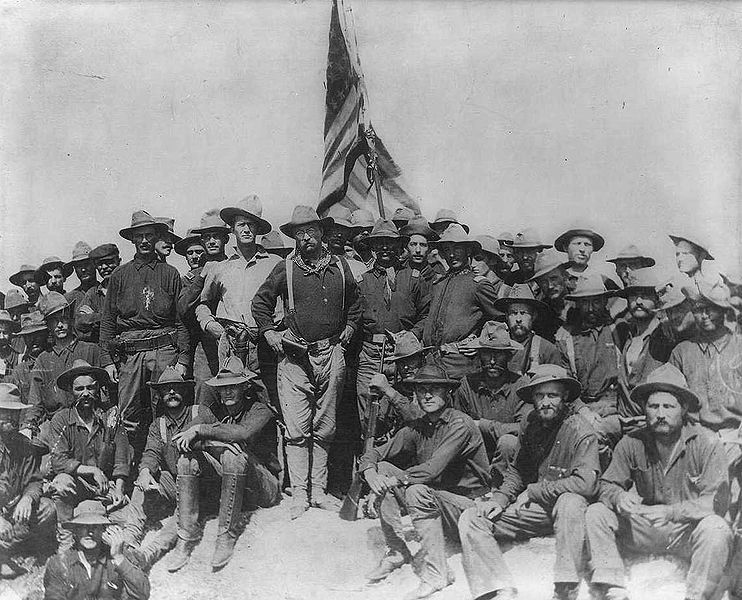

In the meantime, Roosevelt made a name for himself by forming his own cavalry regiment, the Rough Riders, and fighting in Cuba, making sure to get his troops filmed at every opportunity. The colorful group included Native Americans, miners, gamblers, college football players, and ranchers/cowboys among others, including former Confederate general Joseph Wheeler. In Texas, Roosevelt used the Menger Hotel bar in San Antonio as his main recruiting ground. The Rough Riders fought courageously, if recklessly, at the Battle of San Juan Hill. Roosevelt was proud that his regiment lost more than any other (89) and told a reporter that he lamented not coming home with a debilitating or disfiguring injury. His heroics helped catapult “TR” (Roosevelt) into the vice-presidency two years later and, then, the presidency a year after that in 1901 when William McKinley was assassinated.

Even before American soldiers set foot on Cuban soil, the U.S. was in Puerto Rico and Spanish-held territories in the Pacific, including Guam and the Philippines. They also territorialized Hawaii two months after hostilities commenced against Spain, in June 1898, though that wasn’t a Spanish colony. Admiral George Dewey’s Asiatic Naval Squadron demolished Spain’s fleet in Manila Harbor, the Philippines, in a single day. The U.S. acquired Puerto Rico as a territory, but not a state, and allowed unlimited immigration to the mainland for its citizens. By the mid-20th century, there were more Puerto Ricans in New York City than all of Puerto Rico. While eventually granting Puerto Ricans citizenship without full representation in Congress (commonwealth status), the U.S. built up the country’s infrastructure, including roads/bridges, sewers, and hospitals. In the meantime, American companies invested in sugar production. Most malevolently, mainland doctors had virtual carte blanche to experiment on Puerto Ricans.

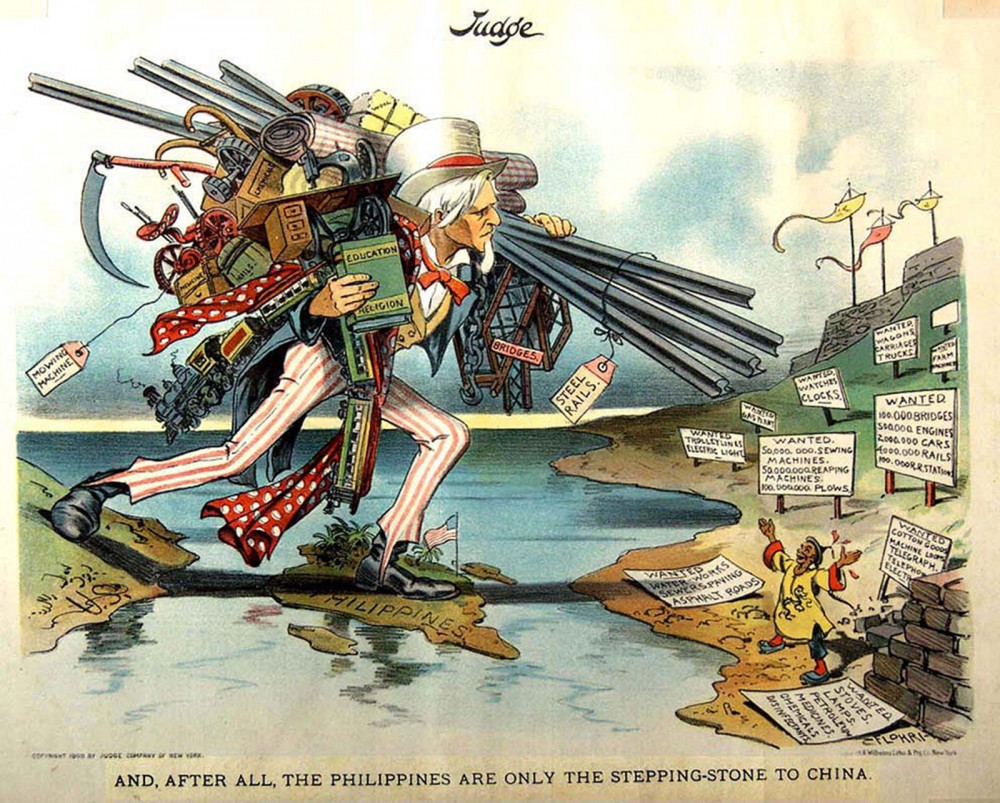

Across the Pacific, the post-liberation scenario was more contentious in the Philippines. Many Filipinos believed the initial spin, thinking the U.S. was only there to liberate them from Spanish control, not realizing the U.S. intended to replace the Spanish and make the islands American territory. The U.S. could build bases there, per Mahan’s sea power strategy, to bolster their military presence in Asia. President McKinley moreover worried that anything less than a complete takeover would create a power vacuum in which the Japanese and Europeans/British would fight over the Philippines. Realistically, most Filipinos knew that Americans would want something in the bargain and hoped at least for the protectorate status enjoyed by Cuba. But the U.S. wanted a full-blown colony, not another puppet state, at least temporarily until it trusted Filipinos to run their own democracy.

What followed was a brutal conflict in which the post-colonial United States found itself suppressing a colonial rebellion and, for the first but not last time, fighting in the jungles of Southeast Asia. American troops struggled to distinguish who the rebel forces led by Emilio Aguinaldo were, resorting to waterboarding (then known as “the water cure”) to interrogate prisoners and the same type of reconcentration camps the Spanish used in Cuba. Meanwhile, Thomas Edison filmed fake battle scenes in New Jersey for Nickelodeon audiences anxious to see Americans in combat:

Americans didn’t mind the inauthentic footage, but some objected to American imperialism. They pointed out the obvious fact that the proverbial shoe was now on the other foot, with the U.S. playing the role of Britain in 1776. Others objected on racial grounds, fearing that Filipinos would become Americans if the U.S. annexed the islands. Andrew Carnegie even offered to buy the Philippines for $20 million to evict American troops and exploit the islands’ iron ore deposits. Joseph Pulitzer, who’d enthusiastically supported the war when it was selling newspapers, opposed what he called “colonialism.” Mark Twain, who joined the American Anti-Imperialist League, was the most outspoken, especially in his criticism of the Moro Massacre in which troops killed 600 Muslim villagers. One soldier wrote home to his parents in Washington state, “All we want to do is kill [N-word]s…beats rabbit hunting all to pieces.” In 2016, presidential candidate Donald Trump fired up voters by reviving the apocryphal tale that Americans dipped their bullets in pig blood before executing Muslim rebels (Muslims don’t eat pork). Some “smoked Yankee” (black) soldiers defected to the other side to protest the killings. Meanwhile, Filipino insurrectos mutilated and tortured Americans whenever they had the chance. Five-thousand U.S. troops died in the war, along with around 200k Filipinos. Two primary sources capture at least part of the American public’s view. One war veteran, General Frederick Funston, wrote editorials to drum up support among the public. He penned this for the Kansas City Journal on April 22, 1899:

I am afraid that some people at home will lie awake [at] night worrying about the ethics of this war, thinking that our enemy is fighting for the right of self-government…[The Filipinos] have a certain number of educated leaders — educated, however, about the same way a parrot is…They are, as a rule, an illiterate and semi-savage people, who are waging war not against tyranny, but against Anglo-Saxon order and decency…I, for one, hope that Uncle Sam will apply the chastening rod good, hard, and plenty, and lay it on until they come into the reservation and promise to be good ‘Injuns.’

Indiana Senator Beveridge, of the Manifest Destiny quote toward the beginning of the chapter, defended American tactics on the floor of Congress: “We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee under God, of the civilization of the world…it has been charged that our conduct is cruel. Senators, it is the reverse. We are not dealing with Americans or Europeans; we are dealing with Orientals.” That’s the dark side of Alfred T. Mahan’s plan, if indeed it was even necessary to conquer the islands to trade in Asia. The U.S. mostly got control by 1902 — the Moro Rebellion in the southern Philippines lasted until 1913 — but, suffice it to say, there were no homecoming parties for troops. The entire episode, in fact, didn’t make it into American history textbooks until around the 1980s, and there are plenty of people today that would just as soon “flush it down the memory hole.”

“Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took the Philippines,” New York Journal, May 5, 1902

Teddy Roosevelt objected to the term imperialism to describe U.S. actions, preferring “large policy.” In 2010, the Texas State Board of Education proposed banning public school textbooks from using the term imperialism to describe U.S. policy in this era. That flies in the face of what happened in the Philippines, especially given the existence of an organization at the time that opposed American imperialism. Unlike the normal routine in European colonies, though, the U.S. eventually came through on its promise to grant independence to the Philippines in 1946. Like European colonizers, the U.S., especially under future President W.H. Taft, also built roads, bridges, schools, and ports. Later, it liberated the islands from Japanese control during World War II. The U.S. signed a binding treaty to protect the Philippines in 1951, though recently the country has started to swing its allegiance away from the U.S. toward China.

China

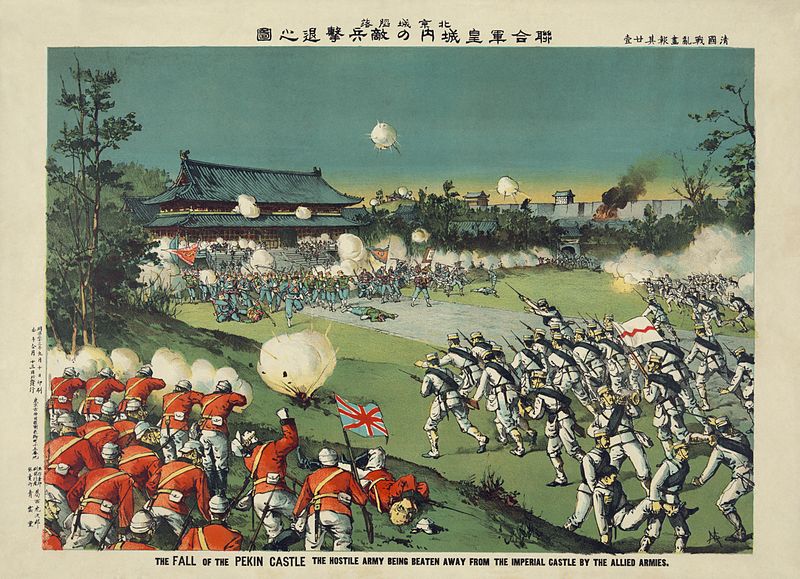

Many American troops fighting in the Philippines shipped to China in 1900 to put down the Boxer Rebellion, a two-year nativist uprising that killed 30k Chinese Christians and over 500 “foreign devil” missionaries and merchants. Westerners called the rebels boxers to describe their martial arts, though they called themselves what translates directly into “Righteous Harmony Fists.” The Boxers held Peking (now Beijing) under martial law for 55 days and ceremoniously tossed opium into the sea. Such anti-foreign sentiment could be found anywhere — the U.S. was then experiencing its own anti-Asian movement on the West Coast — but Boxers were reacting to an actual loss of Chinese sovereignty on their home soil. Some background is in order.

Europeans called the parts of China they cordoned off spheres of influence. Britain pioneered the Asian sphere idea, carving out enclaves in Hong Kong and Shanghai starting in the 1840s. Under the guise of free trade, they acquired the ports fighting Opium Wars to maintain their trafficking of South Asian drugs to the Chinese. The British were feeling the effects of a worldwide silver shortage and they needed a trade item to offset their high-volume purchases of Chinese tea, so as to not transfer too much of their silver coinage. They offered up Wedgwood pottery, woolen fabrics, and fine instruments and tools (e.g. clocks), but the Chinese weren’t buying, and the Hawaiian sandalwood trade was in decline. The British had access to poppy fields in eastern India (Bengal) and Afghanistan, from which they could process opium from the latex of immature seeds. Through their British East India Company, they fueled a drug epidemic, exacerbated by some opium production within China. (The BEIC will sound familiar to students who’ve studied the American Revolution, as it was involved in the 1773 tea crisis). The BEIC, which governed India until 1858, professed ignorance as to what happened after the drugs were auctioned off in Calcutta; but they, along with American shippers, used subsidiaries to import it to China through corrupt Chinese customs officials. From time to time, customs officials would engage in a half-hearted chase of smuggling boats to make it appear they were trying to keep the opium out. The BEIC laundered the silver from opium sales back through its banks in India before returning it to China to buy tea and pocketed the surplus.

China had outlawed opium in 1729, but Britain went to war to keep their illicit drug trade alive. At the First Opium War’s (1839-42) conclusion, they acquired river deltas and five ports in the Treaty of Nanking, including Shanghai and the prized deep-water harbor of Hong Kong. They took over customs and legalized opium, helping to weaken the already crumbling Chinese empire. Qing Viceroy Lin Zexu wrote “there is a class of foreigner that makes opium and brings it for sale, tempting fools to destroy themselves, merely in order to reap a profit” while British Prime Minister William Gladstone later said, “a war more unjust in its origins, a war more calculated…to cover this country with disgrace, I do not know and have not heard of.” Eventually, the British addicted over 12 million peasants, supplying 20% of total revenue for their government in India. Warren Delano, maternal grandfather of future U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, made his fortune in Hong Kong distributing opium from a barge. British businesses like Jardine, Matheson & Co. and HSBC (Hongkong & Shanghai Bank Corporation) set up around the opium-for-tea trade and fostered more wholesome growth in construction, retail, and real estate. However, Chinese tea production went into decline as the British established competing plantations in India.

Soon, other Western powers wanted a sphere or two for themselves, though the U.S. was content with the nearby Philippines and a slice of Shanghai. After the Second Opium War (1856-60), all Chinese government documents had to be written in English. By 1900, the British, Russians, Germans, and French controlled 13 of 18 Chinese provinces between them. Animated Map As China’s long-standing Qing Dynasty weakened, imperial powers moved in to carve up the country’s eastern portion that included enclaves (harbors) along the Pacific coast. The U.S. brokered an agreement called the Open Door Policy, dictating that each country could develop railroads and telephone lines in their respective sphere but had to maintain open trade with the other countries. Each sphere would maintain what we today call “most favored nation trading status” with the others. Most observers thought the whole country would be divided up, partitioned among the various powers that circled it like sharks smelling blood in the water. Unsurprisingly, some Chinese objected and fought back with the Boxer Rebellion.

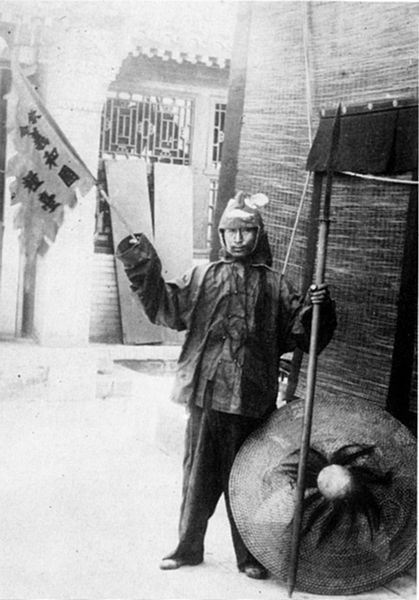

Chinese Boxer (flag says, “欽令 義和團糧臺), 1900, Department of the Army, Office of the Chief Signal Officer, National Archives

The Boxer Rebellion was grounded in complications stemming from the Opium Wars and their aftermath but, as you’ll see from this brief digression, opium was causing problems in Europe as well. While Britain hoped initially to just foster an epidemic in China, opium use spread to Europe and Britain. The advent of the hypodermic needle made it easier for users to get morphine, a strong opium derivative, directly into the blood system. Laudanum, an opium tincture (alcoholic extract) with about 10% morphine, was generously stocked on grocery and pharmacy shelves and popular among working classes on weekends. Women couldn’t drink or smoke tobacco in Britain, but some had ornate syringe kits in their purses similar to a makeup compact and could shoot up under the table.

Earlier in the 19th century, Romantic poets like Lord Byron, John Keats, Percy Shelley, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge popularized opium, along with Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. By the late 19th century, Britain and Western Europe were in the throes of an epidemic as people used opium for minor ailments like stomach aches and headaches. When German pharmacists at Bayer tried to concoct a weaker opiate to gradually break addictions, they inadvertently invented a more addictive one in heroin (based on the German heroisch, for heroic or strong). At first, though, people didn’t appreciate its addictive and degenerative effects, so doctors prescribed heroin both for everyday medicinal purposes like coughs and colds and as a way to ratchet down morphine addiction.

To make a long and sordid story longer, Christian missionaries in China trying to help addicts were passing out heroin-laced “Jesus pills,” unwittingly making the problem worse. Chinese Viceroy Lin wrote to Britain’s Queen Victoria, appealing to her Christian values to stop the opium traffic but Victoria never replied. The ensuing Boxer Rebellion was aimed not just at businessmen and opium dealers, but all foreigners, including missionaries and their converts. Far more Chinese died in this uprising than foreigners. Hardcore “iron hat” rebels thought their spirituality would shield them from bullets and distributed leaflets in the countryside that said it wouldn’t rain until foreigners left the country. After initial hesitation because she partly feared the Boxers, the Empress Dowager Cixi (Qing Queen) supported the war on foreigners, complaining that, “foreign warships occupy our harbor, foreign armies occupy our forts, foreign merchants administer our banks, foreign gods disturb the spirits of our ancestors…is it surprising that our people are aroused?” Drought and hunger compounded their frustration.

In reaction to the Boxer Rebellion, a multi-national force of Open Door members, including European, American, and Japanese forces, put down the Boxers and quashed any hope of self-rule by the Qing Dynasty. The forces reached 100k at their peak and were led first by the British, then Germans. According to Chinese textbooks, occupying troops looted and massacred citizens in Peking (Beijing), with corpses piling up in the streets. According to British textbooks, China was only spared from being completely taken over “because European powers feared the ambitions of each other more than they wanted to rule China.”

Japan took advantage of chaos in China. Already, even before the Boxer Rebellion, Japan had fought China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) and extracted a £30-million war indemnity that China couldn’t afford. That forced China to turn to Western banks who loaned them money in exchange for mineral rights, railway contracts, and more land. At the time, the U.S. and Britain supported Japan because they wanted a strong Japan to check Russian aggression in East Asia and didn’t mind them weakening China.

All that started to change in the early 20th century as Japan asserted its power in the region. Just as the United States claimed control over the Americas with the Monroe Doctrine, Japan eventually claimed its right to do likewise in East Asia, though they went about it with more suddenness and brutality. By the 1930s, the Open Door had shut, as Japan took advantage of its close proximity to conquer most of eastern China. This caused World War II in the Pacific, triggered by the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-41).

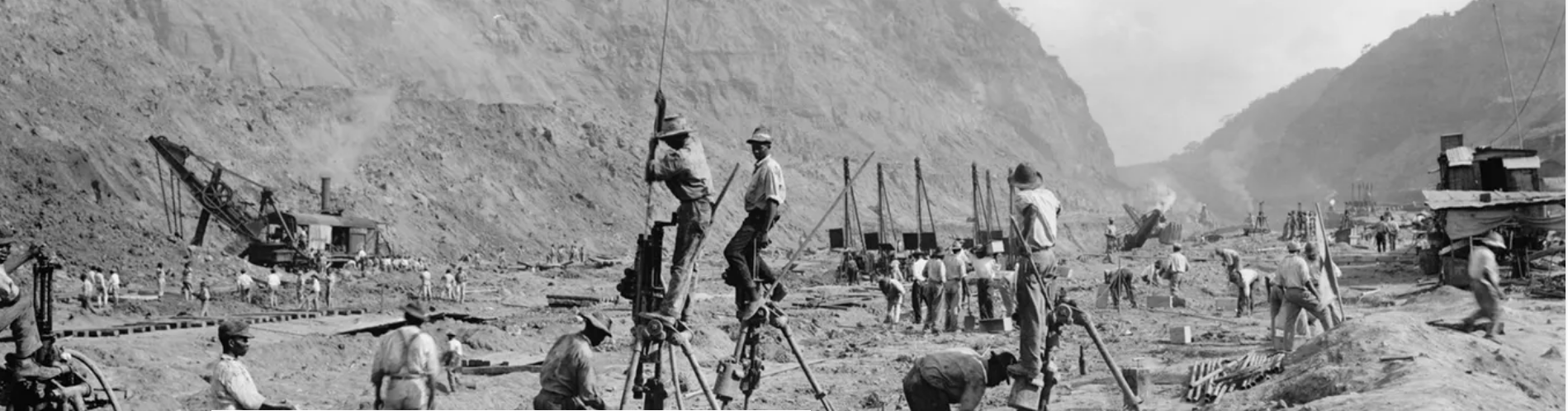

Panama Canal Construction Workers Drilling Dynamite Holes In Bedrock & Steam Shovels Moving Rubble To Railcars, 1913, Everett Historical & Shutterstock

Panama Canal

Panama Canal

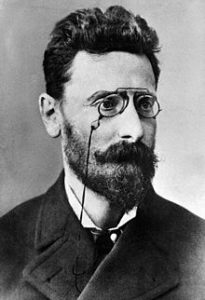

Fighting the Spanish-American War simultaneously in the Pacific and Caribbean underscored America’s need for a canal through the Western Hemisphere’s narrowest point. Without a canal, the U.S. had to operate two separate navies, and merchant shipping between the East Coast and West Coast and Asia had to wind around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America. To see how challenging that was, go to windy.com anytime and navigate down to where the Atlantic and Pacific are colliding to form what often looks like a Category 1 hurricane. Nicaragua would’ve been a good choice for a canal, with a good system of natural rivers to build on, but French investors who stood to gain from completion of a Panamanian project that they’d begun and given up on convinced U.S. Senators that Nicaraguan volcanoes posed too much danger (bribed, more likely). Colombia controlled this narrower portion of Central America where the French started building a sea-level ditch in the 1880s, and President Roosevelt manufactured a false flag incident by finding some Colombians dissatisfied with their government. At first, Colombia agreed to sell the land but when they doubled the price Roosevelt said he wouldn’t be highballed by “Bogota jackrabbits.” The U.S. helped rebels claim independence in the area that became known as Panama in 1903. Regardless of false flags or real flags, there are always a handful of people in any country that might want to overthrow their government. That northwest portion of Colombia had rebelled before, but this time the U.S. Navy blocked Colombia’s warships when they went to suppress the uprising. Of course, the U.S. got the Canal Zone as part of the arrangement with the new country of Panama; the Navy doesn’t work for free. One journalist wrote that the U.S. had “stolen the land fair and square.” However, journalist Joseph Pulitzer (right) of the [New York] World accused the U.S. of colonial aggression and uncovered corruption in the canal’s financing, prompting Roosevelt to unsuccessfully sue him for libel. Pulitzer’s victory in the libel case was also a victory for the First Amendment right to free speech. Roosevelt boasted in his autobiography: “I took the canal and let Congress debate, and while the debate goes on, the canal does also.”

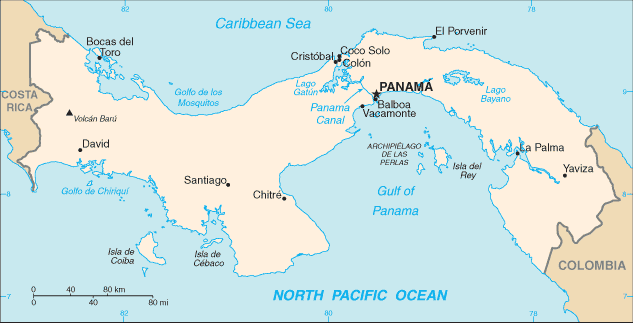

The French engineers were the same ones who dug the Suez Canal and, at first, the U.S. followed their lead of trying to build a sea-level canal. But rather than digging a ditch all the way across the isthmus like the French, the U.S. built locks and a dam that raised water to the level of man-made Gatun Lake in the middle (enlarge this detailed map). As you can see on the map below, the Atlantic entrance is actually west of the Pacific entrance. Roosevelt enlisted America’s best minds and Caribbean laborers in the biggest engineering challenge in history up until that point, and TR even became the first U.S. president to leave the country while in office when he visited the Canal Zone.

The canal made use of steel, oil, and electrical technology that evolved during the Industrial Revolution and was financed by Wall Street tycoons like J.P. Morgan and what’s now Citibank. Mosquitoes plagued the workforce with malaria but quinine vaccines alleviated that danger and they doused breeding waters with kerosene. Still, ~ 5600 workers died of accidents and disease during the U.S. construction phase (the French had lost 200 per month). The Panama Canal project took 14 years, from 1901-1914. This stupendous feat didn’t gain much fanfare or media coverage when finished because its opening coincided with the start of World War I (when the U.S. entered the war in 1917, they built ships in Seattle and sent them to the Atlantic via the canal). The U.S. ceded canal control to Panama in 1977 and, today, a second wider canal completed in 2016 runs parallel to the first, expediting shipping between Asia and Gulf/Atlantic harbors like Houston, Miami, Norfolk, and the Port of New York & New Jersey.

Roosevelt Corollary

Panama’s takeover occasioned a Monroe Doctrine update on Teddy Roosevelt’s part the following year. The U.S. would not only repel any new foreign interference in Latin America, as proclaimed in 1823; it would also intervene to resolve disputes on its own behalf. Without saying as much, the U.S. assumed the right to overthrow and replace any Latin American regime unfriendly to American interests. This was the 1904 Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. The U.S. had decided by then to not make any of the banana republics U.S. states or even to govern them directly as colonies, but rather to utilize diplomatic leverage to exert its influence and keep profits flowing to American companies like United Fruit and Standard Oil. The key Latin American exports to the U.S. were copper from Chile, tin from Bolivia, coffee and sugar from Brazil and Costa Rica, fruit and sugar from the Caribbean and Central America, and petroleum from Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico.

The U.S. didn’t want Europeans interfering in Latin America by trying to collect debt the way they had in the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902-3. Britain still considered Argentina, for instance, as part of its Informal Empire. The U.S. would restructure debt obligations during a regime change if need be, but they didn’t want British or Europeans nosing around anywhere in the Americas in the meantime. The Roosevelt Corollary goal became a reality during and after World War I, when Britain and France were too preoccupied to exert much influence in Latin America.

Lending money with strings attached empowered the U.S. in a sort of “imperialism lite” system called Dollar Diplomacy, known to some as Gunboat Diplomacy because it carried with it the implicit threat and occasional use of force. Roosevelt’s presidential successor, William Howard Taft, named this softer side of the coin “dollar diplomacy.” The U.S. intervened wherever necessary, as it did off and on in Nicaragua from 1909-33 and in Haiti (see optional article below). The U.S. ostensibly wound down the Roosevelt Corollary in 1934 during the presidency of Roosevelt’s distant cousin, Franklin, whose Good Neighbor Policy ended American occupation of Nicaragua and Haiti and ended U.S. sovereignty over Cuba. The Clark Memorandum of 1928/30 had already stated that future U.S. intervention relied simply on its rights as a state instead of the Monroe Doctrine. Dollar Diplomacy wasn’t all bad for debtor nations. Cuban sugar production improved under American control, for instance. However, it was understood that the creditor had ultimate control over the debtor’s politics.

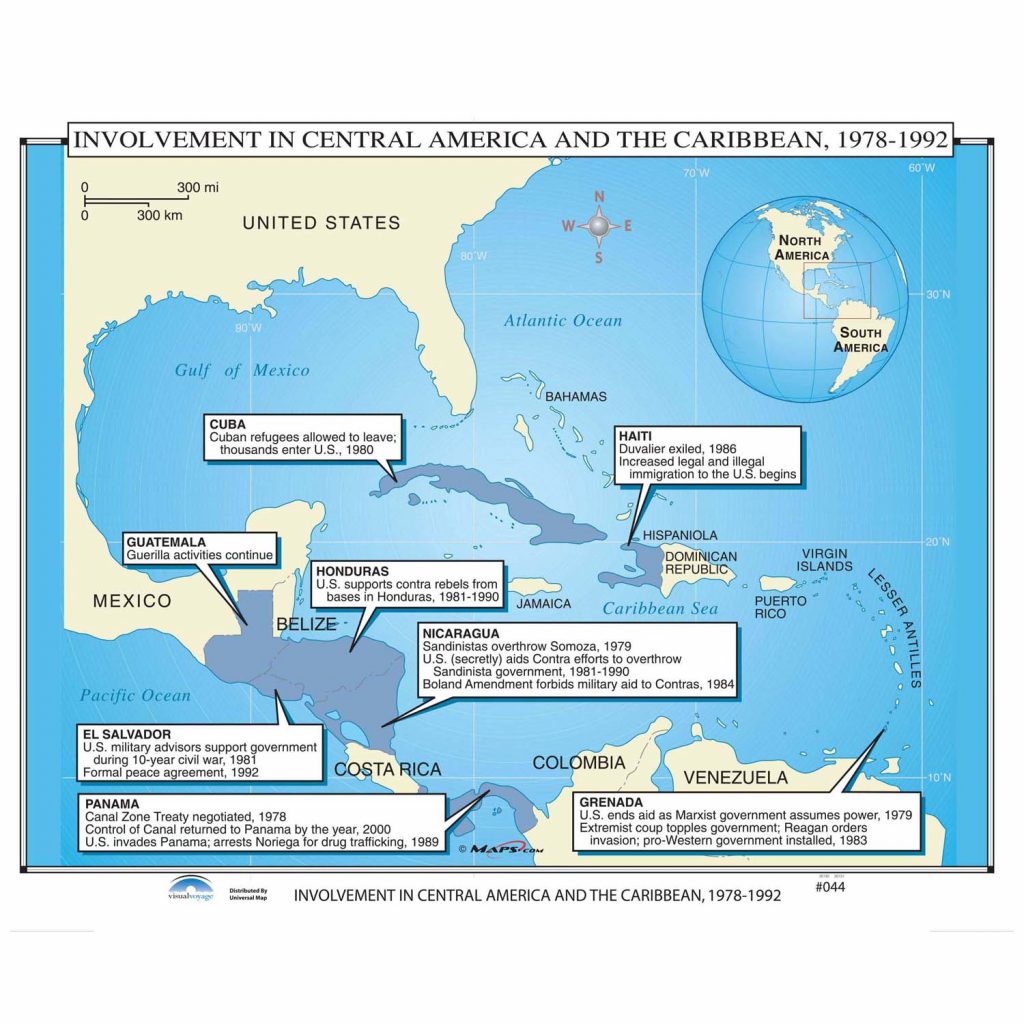

The U.S. resumed a more active role with the Cold War’s onset in 1945, backing right-wing dictators in Cuba (Fulgencio Batista), Nicaragua (Somozas), the Dominican Republic (Rafael Trujillo), Guatemala (Castillo Armas), Chile (Augusto Pinochet), Haiti (François “Papa Doc” Duvalier), and elsewhere. Latin Americans, by and large, had fewer freedoms than landholding colonial Americans under British rule in the 18th century. American control wasn’t nearly as direct as Soviet control over Eastern Europe but neither was it in the interest of capitalism to encourage democracy in the region, whereby voting might’ve resulted in left-leaning socialist democracies unfriendly to U.S. corporations. Speaking to Latin American diplomats in 1962, President John Kennedy said, “those who make peaceful revolution impossible, will make violent revolution inevitable.” What he meant was that, with less harsh control and more compromise on issues like voting, land control, and toleration of unions, the U.S. and its right-wing allies wouldn’t create such fertile soil for alternatives like Fidel Castro’s communist dictatorship in Cuba. But Kennedy’s successors didn’t share his goal of more democratic governments in Latin America, as shown in the map above from just 1978-82. The result, especially in Central America, was ongoing civil wars between pro-American right-wing dictators and their anti-American left-wing counterparts.

Great White Fleet

As Teddy Roosevelt liked to put it, from a West African proverb he’d heard, “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” One big stick Roosevelt now enjoyed was a revamped Navy, built with Andrew Carnegie’s reinforced steel. While still not as large as Britain’s Royal Navy, it was obvious the U.S. was stepping onto the international stage dominated by Europeans for centuries. Sixteen new Navy battleships, nicknamed the Great White Fleet, embarked on a world tour in 1907-1908 — a demonstration that included politely but proudly sailing in and out of key ports for others to see. Admiral Perry would’ve been proud.

Conclusion

The U.S. was late to the colonial game, having been occupied with its own continental expansion. It had less appetite for the old-fashioned, naked conquest-type imperialism pioneered by Europeans, whereby the mother country plants its flag and administers the area politically on unwilling natives. Why not save the bother and expense and just have a military on call ready to ensure that profits flowed back to the mother country? While the U.S. took over some areas, elsewhere it preferred to exert influence through Dollar Diplomacy. Because of the Industrial Revolution, they needed markets and were wielding a “big enough stick” to gain those markets. The U.S. acquired Alaska, American Samoa, Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, a small share of Shanghai, China outside the walled city, and the Panama Canal Zone while exerting influence over Cuba and other countries in Latin America. Many of these are insular territories, protectorates, or states today. In other ways, though, the Industrial Revolution mitigated the need for actual colonies. The advent of synthetic rubber, for instance, meant that industrialized countries didn’t need territories with rubber trees.

To this day — based on an outdated ruling that its citizens are too alien to comprehend Anglo-Saxon principles — the U.S. hasn’t granted full rights to residents of Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Marianas or the Virgin Islands. Americans in unincorporated Insular Territories are U.S. citizens (except Samoans), serve in the military, and pay payroll taxes but can’t vote in national elections and don’t pay federal income tax. Their congressional representatives can serve on committees and even sponsor legislation, but not cast final votes. Roughly similar to the Thirteen Colonies in relation to the British Empire prior to 1776, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1901 that the “Constitution does not follow the flag.” Hawaiians and Alaskans, however, enjoy full rights (and obligations) as those territories became states in the 1950s. Still, America’s foray into old-fashioned, overseas imperialism was brief — preceded by a long history of relative isolationism/continental expansion encouraged by the Founding Fathers and followed, especially after World War II, by foreign policy more focused on alliances and ideologies rather than acquiring new territory.

Optional Reading & Listening:

Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaii, 1897, National Archives

Jerry Hendrix, “The Age of American Naval Dominance Is Over,” Atlantic (April 2023)

Alvita Akiboh, “The ‘Massacre’ and the Aftermath: Remembering Balangiga and the War in the Philippines,” U.S. History Scene (n.d.)

Aroop Mukharji, “The Psychology of Stickiness: What the U.S. Can Learn From Its Annexation of the Philippines in 1898,” War On the Rocks (5.5.22)

Caroline Leiffer, “The Panama Canal’s Forgotten Casualties,” Conversation (4.18)

Gebrekidan, Apuzzo, Porter & Méheut, “Invade Haiti, Wall Street Urged. The U.S. Complied,” New York Times (5.26.22)

Casey Michel, “Russia’s Slaughter of Indigenous People In Alaska Tells Us Something About Ukraine,” Politico: History Dept. (10.27.23)