“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are…tied in a single garment of destiny.” — Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

America didn’t invent racism, but its combination of democratic ideals, slavery, and diverse population make race relations more combustible in the U.S. than elsewhere. Racism is America’s “original sin” and original sins aren’t cleansed overnight. While civil rights movements have addressed these relations throughout American history, the Civil Rights Movement in capital letters generally refers to the Montgomery-to-Memphis period from 1954-1968 — from Brown v. Board and the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the mid-’50s to Martin Luther King’s assassination in Memphis in ’68. That was a 15-year stretch of grassroots activism and stellar leadership among Blacks and Hispanics that, combined with unprecedented cooperation among a critical balance of Whites, allowed for progress on the legal status of minorities in America, in effect winning them citizenship but not economic equality. It was the most productive period since the Civil War, called Second Reconstruction because it dealt with many of the same issues that post-Civil War Reconstruction (1865-77) failed to resolve.

We’ll broaden the scope chronologically, tracing back to the early 20th century, then pick up the story in earnest during the New Deal and World War II, look at how black civil rights impacted movements among other groups, and conclude by examining the hot-button topic of affirmative action. Along the way, we’ll unpack more details concerning the famous period from 1954-68.

Early Civil Rights

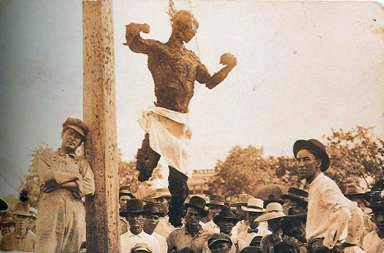

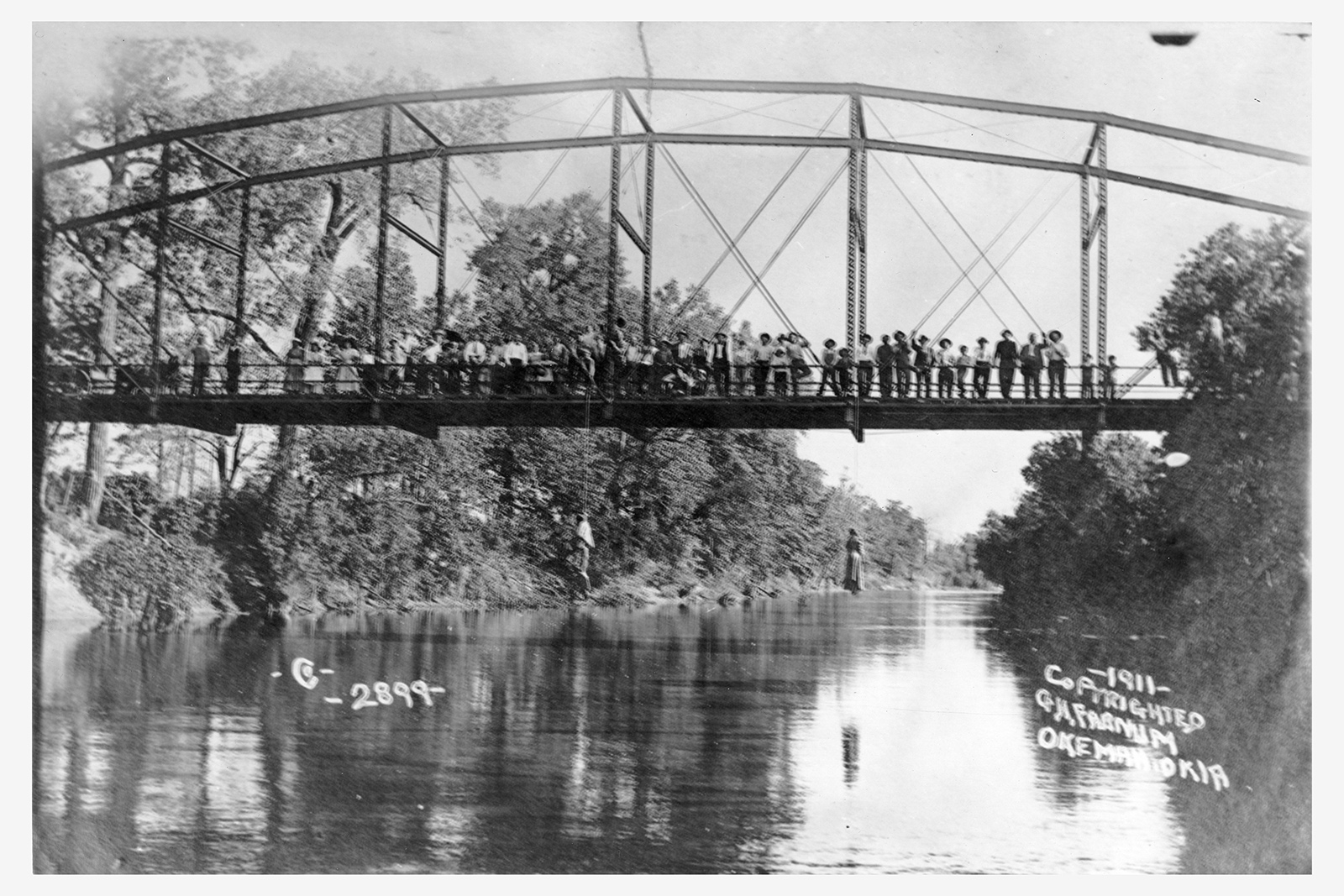

First, some background. After southern Democrats stopped civil rights in their tracks during Reconstruction, and the Supreme Court went along with weakening the Fourteenth (1868) and Fifteenth Amendments (1870), progress stalled in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The result was a tragic combination of disenfranchisement, segregation, false imprisonments/convict lease labor, vigilante murders, and poverty. It was a reverse revolution given some of the hopes raised by the Civil War and early Reconstruction. Black lynchings and ritual burnings attracted big crowds, who gathered around the corpse afterward to pose for photos. As we saw in Chapter 7, witnesses sent friends and relatives postcards of photos like the one on the left. Sometimes, as in the case of Mississippian Will Echols, the victim was made to kiss the Confederate flag before being killed. Victims included Blacks and Hispanics suspected of crimes or those deemed too successful, as was the case in Thomas Moss’ 1892 lynching in Memphis, that inspired his friend, suffragist Ida B. Wells, to pursue a career in activism. During the Bandit War along the Mexican border between 1910-1920, white Texans hanged, burned, or mutilated several non-combatant Hispanics during La Matanza (“The Slaughter”). Over 500 Mexican Americans were lynched between 1848 and 1928, some by Texas Rangers, others by mobs.

It’s been said, with some accuracy, that while the North won the Civil War the South won Reconstruction. While true to a point, it ignores the racism African Americans experienced in the North and West, including after the Great Migration to industrial cities during and after World War I. If it had been otherwise then southern racism wouldn’t have been a problem because Blacks could’ve just followed a red carpet north. Instead, what was red was the blood running into street drains when soldiers returned home from WWI to find Blacks and Mexicans living in their neighborhoods and working in their factories. Thus, 1919 became known as Red Summer which, as we learned about in chapters 6-7, carried over into the early 1920s. In the 1920s, Ku Klux Klan chapters were entrenched across the North.

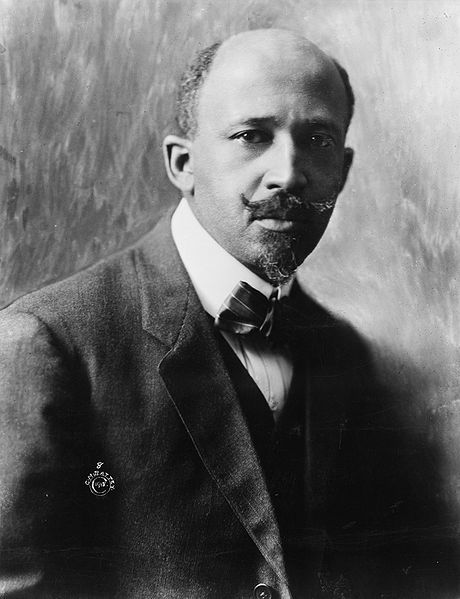

Early black activists disagreed over how to best rectify the situation. W.E.B. Du Bois wanted to use the courts to beef up the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, to secure basic rights of citizenship and voting. This push for equality was known as the Niagara Movement, named for the “mighty current of change” that swept over Niagara Falls. Du Bois was a co-founder, along with Jewish Americans, of the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and advocated restoring African pride, solidarity, and culture globally through Pan-Africanism. Booker T. Washington argued for a more gradualist approach advocating that Blacks get up to speed in segregated vocational colleges before pushing for full equality. His Atlanta Compromise acquiesced (temporarily) in white political domination in exchange for education funding and guarantee of due process of law. Washington, who was born into slavery, favored segregation as long as Blacks had genuinely equal opportunity. Jamaican Marcus Garvey shared Du Bois’ belief in Pan-Africanism and promoted black business ownership. These strategies weren’t mutually exclusive, but two of them – using the Constitution and promoting education – combined as important strategies of the modern Civil Rights Movement a generation later.

While the civil rights movement is most famously associated with black America, their tactics and spirit carried over into liberation movements among all oppressed Americans. As of the mid-20th century, that included pretty much anyone who didn’t fit the traditional WASP mold, depending on how one defines oppression. If your definition goes beyond outright violent harassment to include not having political equality, equal pay, career choice, access to capital or positions of power, then it included the vast majority of society. That was largely due to the inertia of tradition rather than the inherent evil of white males or Gentiles. Most people don’t ask fundamental questions about their society. Many Whites irrationally subscribed to a zero-sum game, whereby any gain in the dignity or status of minorities meant a corresponding drop in their own stature. Over and over again in the 1960s, we heard congressmen equate black citizenship with white slavery or complain that minorities seeking equality wanted “special treatment” (more below). One reason some blue-collar Whites abandoned the Democratic Party was their belief that, if Democrats embraced civil rights, they were abandoning white workers. Others subscribed to the racist biology of eugenics we covered in Chapters 4 and 10. Still others were just ignorant or mean.

Contralto Marian Anderson Prepares to Christen the Booker T. Washington, Los Angeles Times Photo Archive, UCLA

When things started to change, people of various races and backgrounds contributed to making America a more democratic society. Eleanor Roosevelt, for instance, was white, and reared in many of the typical attitudes of the patrician class, including intolerance of Jews and Blacks. She changed as an adult, though, often to the embarrassment of her husband Franklin. She publicly supported anti-lynching laws and she resigned from the Daughters of the American Revolution after their refusal to host black singer Marian Anderson in Constitution Hall. In 1939, the NAACP arranged for the contralto to sing in front of the Lincoln Memorial. President Roosevelt was skeptical about allowing Anderson to perform at the federal monument, especially since a recent KKK rally there had degenerated into a violent clash. Pressured by Eleanor, FDR gave the concert the go-ahead and 75k fans, interspersed with some protestors, heard Anderson sing a famous rendition of “My Country Tis’ of Thee,” highlighted by the line from every mountainside, let freedom ring (the song’s melody comes from England’s national anthem “God Save the Queen”). A quarter-century later, standing in that very spot, Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. paid homage, speaking those verses during his “I Have a Dream” speech. After Franklin’s death, NAACP board member Eleanor Roosevelt advocated tirelessly for civil rights, encouraging Harry Truman to work with the NAACP, helping to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott, promoting anti-lynching laws, and trying to desegregate hospitals.

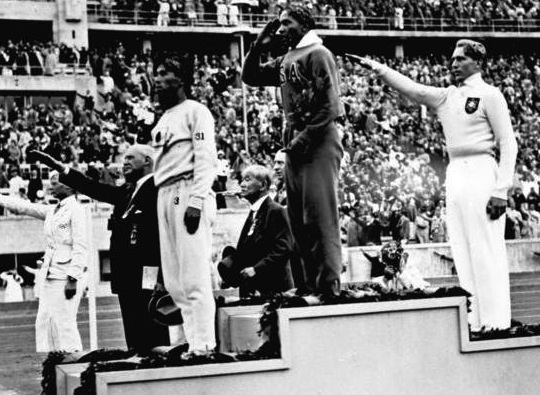

You could see other subtle changes in the 1930s. Many white boxing fans rooted for the “Brown Bomber” Joe Louis over his Nazi counterpart Max Schmelling in their bouts at Yankee Stadium. It’s unlikely American audiences would have done the same for heavyweight Jack Johnson in the 1910s, even against a Nazi. As an indicator of how conflicted America felt about race in the 1930s, New York gave Olympian Jesse Owens a ticker-tape homecoming parade upon his return from the Berlin Olympics in 1936. Yet, as we saw in Chapter 10, when he went to his own reception at the Waldorf-Astoria he had to ride the freight elevator. While much has been made of Hitler snubbing Owens and refusing to shake his hand (he quit shaking all hands after the first day to avoid such situations), Franklin Roosevelt snubbed Owens as well. Only white medalists were invited to the White House to avoid alienating southern Democrats. When Marian Anderson sang in Princeton, New Jersey, she and her white husband always stayed with Albert Einstein because no motel would take them. For pro-labor Democrats to stay united during the Depression, northern progressives had to put aside their differences with “Boll Weevil” southern Democrats and acquiesce in Jim Crow to secure passage of New Deal legislation, though they integrated some programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Jim Crow and Juan Crow were pretty much the way it was throughout America anyway, North and South. The most FDR could do was outlaw discrimination in public projects and, later, in the defense industry. Even that was seen as too much by many, but Roosevelt’s top priorities were to stimulate the economy and keep weapons moving to the battlefield during WWII.

World War II

World War II

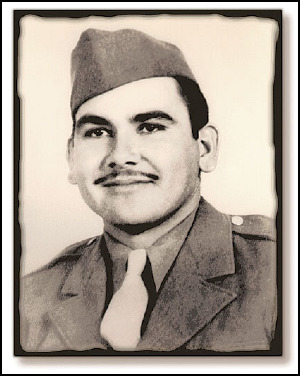

World War II ignited the Civil Rights movement more than the New Deal did. At Pearl Harbor, messman Doris Miller of Waco left his laundry on the USS West Virginia to rescue his captain, then man an abandoned anti-aircraft machine gun. The story garnered attention in the press and Miller earned a Navy Cross for bravery in combat (right). But more broadly, not only did minority troops fight in combat (nothing new), but Americans also looked hard-core racism in the eye when fighting Japan and Germany. Japan’s racially justified brutalization of other Asians and the horrific Jewish Holocaust made some, not all, Americans rethink their own racism. Minority soldiers who fought in the war were also less likely to accept America’s apartheid-like system when they returned. Josh White’s “Uncle Sam Says” protested the hypocrisy of asking people to fight for democracy abroad while denying their rights at home (YT). Many of the half-million Latinos who fought overseas began to fight back against segregationist policies, such as the protests of Medal of Honor winner Macario Garcia in Texas. Veteran Dr. Hector P. Garcia organized the American GI Forum to protest discrimination in the distribution of veteran benefits and the group morphed into a broader civil rights organization.

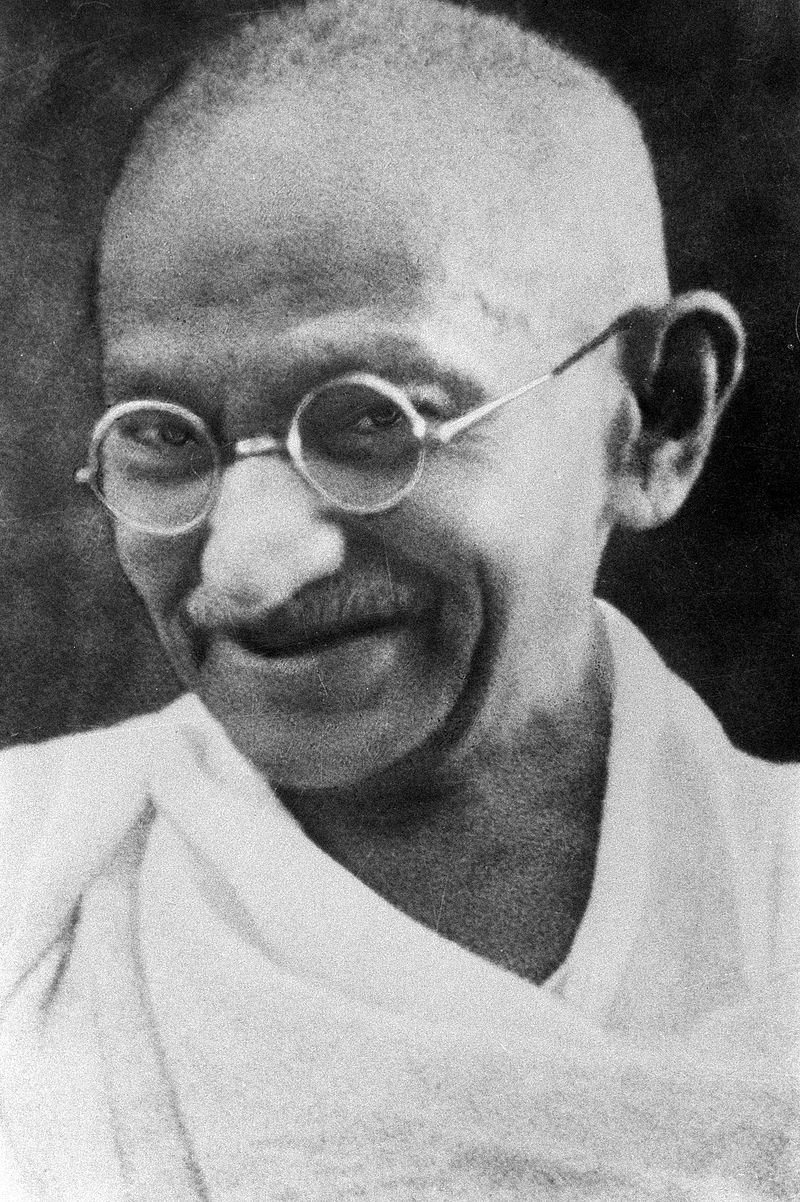

Black veteran/actor/singer Harry Belafonte said, “We came back from this war having expectations, and finding that there were none to be harvested, were put upon to make a decision. We could accept the status quo as it was beginning to reveal itself with all these oppressive laws in place. Or as had begun to appear on the horizon, stimulated by something Mahatma Gandhi (left) of India had done, we could start this quest for social change by confronting the state a little differently. Let’s do it nonviolently. Let’s use passive thinking applied to aggressive ideas, and perhaps we could overthrow the oppression by making it morally unacceptable.”

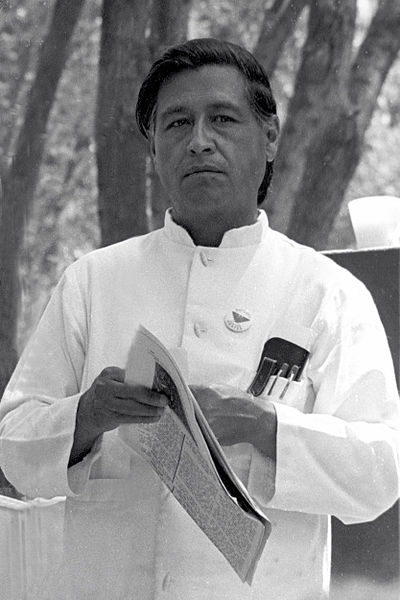

This tactic proved effective in Des Moines where protesters led by Edna Griffin forced Katz Drugstore to integrate its lunch counter through a case in the state’s supreme court in 1948. The passive approach took a variety of forms as we’ll see below, including marches led by Martin Luther King, Jr. and Caesar Chavez modeled on Gandhi’s 1930 Salt March. King also followed Gandhi’s American proxy, philosopher Richard Gregg. Nonviolent protests have been more effective, overall, than violent protests over the last century and have helped expand human rights considerably. However, passive resistance is only possible in societies like the U.S. and British Empire where the oppressors are reasonably civilized and don’t just execute protesters, as would happen in a more authoritarian state. In other words, protesters can only appeal to reason and justice if the authorities are somewhat reasonable to start with and agree on some semblance of justice. Indian independence finally happened when Britain’s government wanted out. The biggest challenge of Indian independence was maintaining peace between Muslims and Hindus, which led to the partition of Hindu India and Muslim (East and West) Pakistan.

The most important Supreme Court case regarding civil rights during WWII was seemingly a setback, but it provided hope nonetheless. In Korematsu v. the United States (1944), the Court ruled that Japanese internment camps were justified but only because of the wartime emergency and that, in the future, they would look skeptically at racially discriminatory laws. That was a bold claim for those that noticed, like the NAACP, because the U.S. had many such laws. After WWII, the U.S. phased out its exclusionary immigration policies toward Asians and granted citizenship to Asian Americans, overturning the precedent of the Supreme Court’s 1923 ruling on Indian American Bhagat Singh Thind that we saw in Chapter 7. The U.S. also granted independence to the Philippines in 1946, rejecting the sort of outright imperialism championed by Europeans in the centuries leading up to WWII.

As mentioned, FDR outlawed discrimination in the munitions industry, and he intervened to break up a Philadelphia transit strike protesting integration of their workforce that was slowing down commuters to the city’s naval shipyards (right). The national government hadn’t used force on behalf of Blacks since Reconstruction in the 1870s. By his third term in office, with the New Deal being phased out, FDR wasn’t as dependent on the support of southern Democrats and the NAACP pressured him to use black troops once the war broke out. In 1940, FDR ran against Republican Wendell Willkie and Willkie’s liberal stance on civil rights pressured Roosevelt to appear more progressive himself.

Many WWII soldiers in the Pacific had relations with Asian/Pacific Islander women or brought home APIA wives. That might not seem extraordinary today (if not, that’s a sign of progress) but, as of the 1940s, mixed-race relationships were illegal in many states. Yet, the willingness of some politicians to embrace civil rights legislation signaled light at the end of the tunnel. The Cold War also played a role after World War II. We learned in Chapter 14 about how the U.S. and USSR were competing among neutral nations to convince people that their way of life offered better prospects. As people in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia wondered aloud why the U.S. itself hadn’t evolved into a true democracy, pressure built in Congress to enact reforms, unsuccessfully at first.

While Congress defeated anti-lynching bills, the number of incidents began to drop off in the mid-20th century. The KKK lynched Michael Donald in Alabama in 1981 and racists dragged to death James Byrd, Jr. outside Jasper, Texas in 1998. In both cases, state governments executed the white perpetrators. Lynching was a common form of vigilante justice employed on suspects of all races but, by the early 20th century, it was used mainly against minorities. Of the 4,743 lynchings in the U.S. between 1882 and 1968, nearly 73% of victims were black (Source: NAACP).

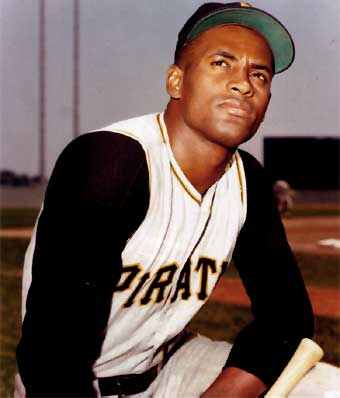

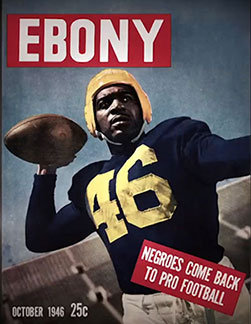

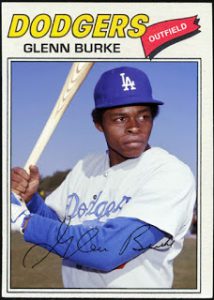

Integration of the military and pro sports in 1946-48 also helped lay the foundation for a brewing civil rights movement. Most important was Jackie Robinson’s integration of major league baseball, then the most popular sport in America. Calling him a “trial balloon,” Martin Luther King said of Robinson that “he was a sit-in’er before sit-ins and a freedom-rider before freedom rides.” Remarkably, before Robinson became a more outspoken civil rights leader in his own right, Gallup polls showed him as the second-most popular American behind Bing Crosby — ahead of Frank Sinatra, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Dwight Eisenhower. You can read more about influential sports and music stories like that of Robinson in the optional section at the end of the chapter.

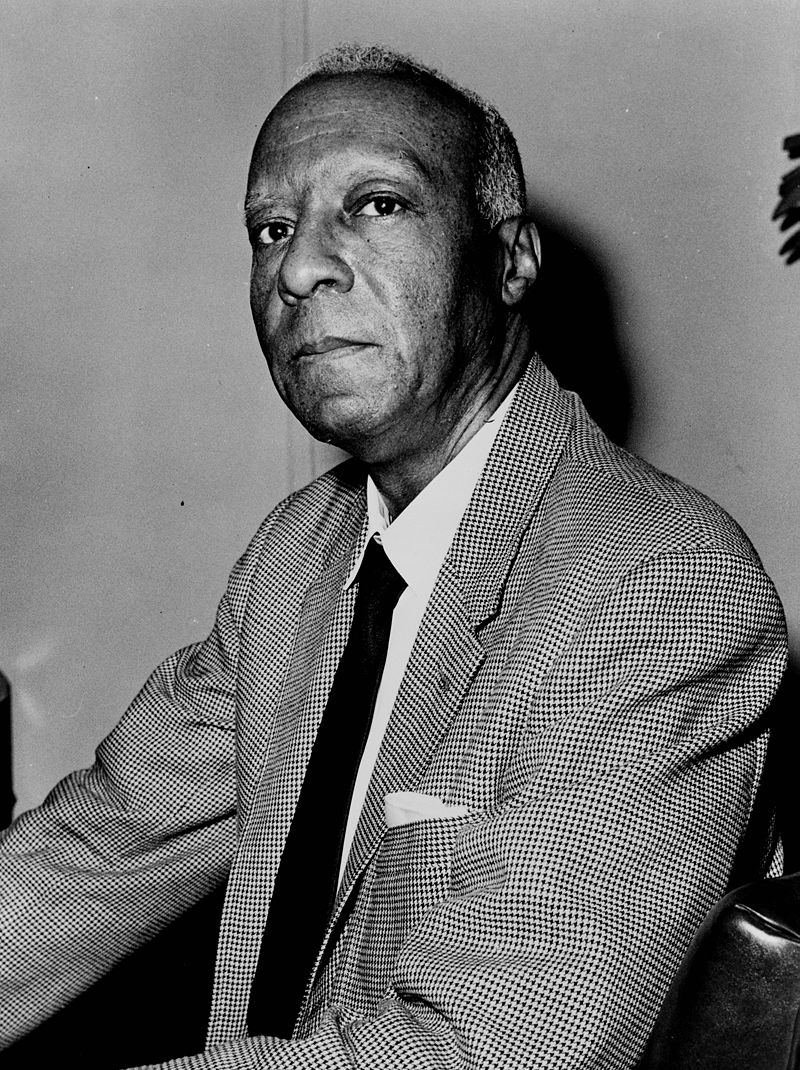

Just as Frederick Douglass was influential in changing Abraham Lincoln’s mind about using black troops during the Civil War, ex-porter and union organizer A. Philip Randolph lobbied Franklin Roosevelt to integrate the munitions industry during the war, influenced Harry Truman’s decision to integrate the armed forces after WWII, and pioneered the idea of peaceful marches on Washington, D.C. among Blacks. Randolph helped organize the famous March on Washington featuring Martin Luther King in 1963. If not the most famous civil rights leader, Randolph is the most underrated. Truman’s enlightenment was key for the Civil Rights Movement and the evolution of the Democratic Party, as he circumvented a reluctant Congress by changing what he could in the Justice Department, civil service, and military. As we saw in Chapter 15, he was outraged by the story of veteran Isaac Woodard, who’d had his eyes bludgeoned out by a South Carolina sheriff who was, in turn, acquitted. How could the U.S. lead globally in the Cold War when it couldn’t deliver on democracy at home? By tying civil rights to communism, racists were playing directly into the Soviets’ hands, essentially agreeing with him by arguing that being racially progressive was un-American. Truman formed a commission to study civil rights and cast his lot with the NAACP. At their 1947 rally in Washington, D.C., he denounced discrimination against anyone based on “ancestry, religion, race, or color” and advocated equality for “all Americans.” Beforehand, the former Missouri Klansman warned his sister in a letter that he was about to give a speech that “momma isn’t gonna like.”

Even the Ku Klux Klan came in for criticism after the war. As we saw in Chapter 15, Hollywood portrayed the Klan negatively starting in the late 30s. That wasn’t surprising given that most of the industry’s leaders were Jewish, but it was a far cry from the Klan’s protagonist role in Birth of a Nation (1915). Two North Carolina writers won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in 1953 for criticizing the Klan and Lumbee Indians routed Klansmen in a forest shootout at the Battle of Hayes Pond in 1958. While the government still wasn’t as focused on far-right groups as far-left during the Cold War, indictments increased some by the mid-20th century. Folklorist Stetson Kennedy went underground and joined the Klan to write a sensationalized exposé, reporting on violence and ridiculing silly terms like “klavalier.” He passed his research onto the writers of the popular Adventures of Superman radio show, which depicted the caped hero taking on the “Clan of the Fiery Cross.” In the 1920s, the KKK wouldn’t have minded a mole infiltrating their group; they would’ve bragged about their violence and racism. Now, they were on the defensive, the state of Georgia revoked their charter, and membership dwindled. Little kids were rooting for Superman to defeat them. The Klan firebombed Kennedy’s Florida home and temporarily chased him out of the country.

White supremacist groups didn’t go away and are still around today but, after WWII, they no longer marched down Main Street USA in parades with the marching band, fire truck, and Kiwanis Club. That wasn’t all good news, though. When the Klan went underground in the form of the White Knights of the KKK, they grew increasingly violent in the mid-1960s. Here we see another, underrated way that WWII connected to the Civil Rights movement. Many black activists were veterans and some, like NRA member and Negroes With Guns (1962) author Robert Williams in South Carolina, used their military background to train NAACP members on how to defend themselves. But, so too, many Klan members were veterans and used their knowledge of munitions to blow up black churches and homes in the mid-20th century, applying their skills to defeating democracy in their own country.

Why Jury Duty Matters

Why Jury Duty Matters

The Supreme Court slowly but surely started to signal its cooperation on civil rights, which it had more or less slammed the door shut on in the late 19th century. Hispanics won an influential decision in Hernandez v. Texas (1954) that gave all minorities the right to sit on juries. The Court ruled jury duty as fundamental to equal protection under the law. Today most of us just complain about being called to jury duty, but ethnic groups lacking that fundamental right were unlikely to experience anything approximating justice. The judge that oversaw Isaac Woodard’s blinding case, for instance, J. Waites Waring, wasn’t to blame for the sheriff’s acquittal and even became a civil rights advocate. It was the jury that made a mockery of justice. The same went for the case of African-American Recy Taylor (right), who was gang-raped in Alabama in 1944: two grand juries acquitted six white men who openly confessed their guilt. Jury duty is a fundamental right of citizenship, not just an inconvenience. Women, moreover, couldn’t sit on juries in some states until the mid-1960s.

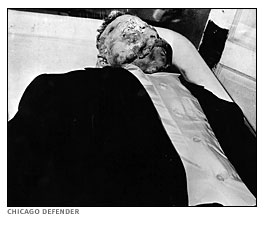

The Emmett Till case gave the TV-watching part of the American public an up-close reminder that, despite being a relative beacon of hope in a hostile world, the United States had some skeletons of its own in the closet. Emmett’s family was part of the Great Migration north, but they were back from Chicago visiting Mississippi relatives in the summer of 1955. The 14-year-old purportedly wolf-whistled to 21-year-old white clerk Carolyn Bryant at the local grocery store, perhaps saying something along the lines of “thanks, baby” after buying some candy. He didn’t realize that what might pass in Chicago broke important social mores in the Deep South. The clerk’s husband and stepbrother came to the Till farm, abducted Emmett, beat him up with a tire iron, gouged out his eyes, shot him in the head, tied him to a 74 lb. cotton gin fan with barbed wire, and threw him in the Tallahatchie River. Till’s mother insisted on an open casket so that the nation could see what the perpetrators had done to Emmett, and images appeared in black publications like Jet magazine and the Chicago Defender. Upon discovery of the body, the local sheriff suspected the murder was some “NAACP-sponsored scheme” to discredit white Mississippians, though normally false flags don’t go to such extremes and there was zero evidence of one here.

The Emmett Till case gave the TV-watching part of the American public an up-close reminder that, despite being a relative beacon of hope in a hostile world, the United States had some skeletons of its own in the closet. Emmett’s family was part of the Great Migration north, but they were back from Chicago visiting Mississippi relatives in the summer of 1955. The 14-year-old purportedly wolf-whistled to 21-year-old white clerk Carolyn Bryant at the local grocery store, perhaps saying something along the lines of “thanks, baby” after buying some candy. He didn’t realize that what might pass in Chicago broke important social mores in the Deep South. The clerk’s husband and stepbrother came to the Till farm, abducted Emmett, beat him up with a tire iron, gouged out his eyes, shot him in the head, tied him to a 74 lb. cotton gin fan with barbed wire, and threw him in the Tallahatchie River. Till’s mother insisted on an open casket so that the nation could see what the perpetrators had done to Emmett, and images appeared in black publications like Jet magazine and the Chicago Defender. Upon discovery of the body, the local sheriff suspected the murder was some “NAACP-sponsored scheme” to discredit white Mississippians, though normally false flags don’t go to such extremes and there was zero evidence of one here.

Bryant testified that Till grabbed her around the waist and made a lewd comment, though the configuration of the counter would’ve made that impossible. An all-white jury acquitted the killers, but they admitted their guilt to Look magazine four months later, still escaping justice because of the Constitutional restriction against double jeopardy (article). Television cameras captured the farcical trial for national news — coverage that did more damage to Jim Crow than a thousand protests could have before the TV age. The local press in Mississippi largely condemned the killing at first but some rallied to defend the killers when they learned that northern journalists were also critical of the trial. Bryant confessed to Duke scholar Timothy Tyson in 2007 that she made up the story about Till grabbing her and making lewd comments, stating that her views on race had changed and that the murder had ruined her life. At the time, she’d recently heard a speech from a state judge warning that school integration would lead to the widespread rape of white women. The incident augured things to come: subsequent civil rights battles played out in the nation’s living rooms, as both sides used the camera effectively to get their points across to broad audiences. Moreover, it testified to the lingering regional resentment from the Civil War and Reconstruction. Like Isaac Woodard, Emmet Till did not die in vain, as the mockery of justice surrounding his case helped propel the modern civil rights movement, just as Trayvon Martin’s 2012 murder sparked #BlackLivesMatter. Till’s death was also an early inspiration for Rod Serling to create the groundbreaking TV series Twilight Zone (1959-64).

Classic Phase

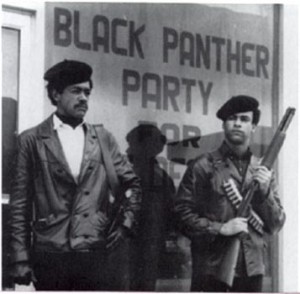

The most famous phase of the black Civil Rights Movement kicked in around this time. It was mainly Southern and Christian and focused on non-violent, passive resistance to injustices such as lack of voting rights and segregation. Ringleaders included Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Council), CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), and Ella Baker’s SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee). James Farmer’s CORE organized sit-ins and freedom rides. King skillfully brokered between younger leaders like Baker and Stokely Carmichael (future Black Panther Kwame Touré) at the SNCC and older gradualists like Roy Wilkins at the NAACP, though he could never seem to please both camps. CORE bridged the gap with white northern civil rights workers, who started integrated sit-ins at segregated establishments there during World War II. It’s not important to learn such acronyms, but rather to realize that change requires organization and to know what strategies these organizations employed.

There are many ways to “skin a cat” but, in this case, reformers used non-violence, politics (organizing/compromising), and biracial coalitions to great effect. Old-fashioned hard work and networking laid the foundation for the movement. Leaders like King played a critical role, but they rode the waves churned up by foot soldiers that went door-to-door and held countless meetings in church basements. Black churches were the nerve centers, serving a networking role similar to taverns during the American Revolution. As Ella Baker once said of King, “He didn’t make the movement, the movement made him.” At the same time, movements need figureheads and King’s eloquent idealism provided the inspiration that unified the Civil Rights movement. MLK optimistically said, “The moral arc of the universe bends slowly, but it bends toward justice.”

As we heard from Harry Belafonte, activists employed tactics Mahatma Gandhi used in India’s successful pursuit of independence from Britain in 1948. For inspiration, Gandhi preached reliance on satyagraha, loosely translated as the “truth force.” American writer Henry David Thoreau advocated a similar approach a century earlier in Civil Disobedience (1849). King distinguished his message from Gandhi’s: unlike the Hindu leader, the Christian King put no stock in fasting, joking that “Gandhi obviously never tasted barbecue.” More importantly, Gandhi lived in a country where 95% of the people were Indian, whereas King operated in a country only 10% black (today ~ 13%). But like Gandhi, King transferred the moral burden of violence onto his oppressors for all to see. One of the movement’s prominent historians, Taylor Branch, recalled a vivid example he witnessed personally. In 1962, a member of the American Nazi Party accosted King at an SCLC rally in Birmingham. Many of those in the audience thought it was staged to demonstrate a point, but it was a real attack. As he punched King in the face and landed body blows, King yelled, “Don’t touch him! We have to pray for him.” At other times during the Civil Rights movement, protestors fought back against the police with clubs, rocks, or knives to defend themselves.

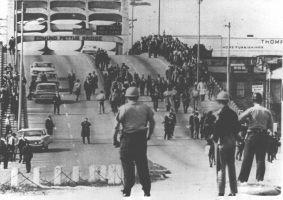

Like Thoreau and Gandhi, Reverend King argued that some laws were worth breaking on behalf of a higher moral cause in his Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963), that he wrote after being incarcerated for non-violent protest. Blacks and Whites sitting together at a lunch counter, for instance, broke society’s laws, but on behalf of an arguably higher cause. There were inter-racial sit-ins at drugstore lunch counters across the South (e.g., Greensboro Woolworth’s) including Austin, and also freedom rides on which Whites and Blacks rode buses together. King helped organize an inter-racial wade-in at the Monson Motor Lodge’s segregated pool in St. Augustine, Florida in Spring 1964, inspiring the motel’s owner to pour hydrochloric acid into the water to drive them out. The photo at the top of the chapter shows the inter-racial 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march. Many of the Whites were Southerners who’d had enough of Jim Crow or whose version of Christianity condemned racism and tapped into the long tradition of Christian Pacifism that weaves in and out of the Old and New Testaments. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel also inspired King to read Jewish scriptures beyond the Old Testament and influenced King’s controversial opposition to the Vietnam War. Heschel, whose Polish relatives died during the Holocaust, was a key crossover leader of the civil rights movement and forged a truce between Judaism and Catholicism whereby the Church stopped teaching that Jews were “Christ-killers” after the Second Vatican Council of 1962-65.

King channeled near Quaker-like pacifism, supporting a defensive war against Hitler but otherwise favoring peaceful paths to resolution. He preached loving thy enemy and turning the other cheek, interpreting Matthew 10:34-36 and Luke 22:36 figuratively and favoring passages like Matthew 5:43, Luke 6:27, Matthew 26:52, or Matthew 5:9: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.” Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) also influenced Mahatma Gandhi. For those more familiar with Game of Thrones, Dr. King would’ve favored “breaking the wheel” of endless cycles of vengeance and retribution; in that case, dynastic wars. It’s an inspirational philosophy and rings true in the long run, but hard to stick with in real life because sometimes groups need to fight for survival and, remembering past transgressions, incline toward settling scores. Taylor Branch wrote that MLK always had one foot in the Constitution and one foot in Scripture.

Black segregationists like Malcolm X and later the Black Panthers condemned this cooperation with white progressives as, of course, did white segregationists. Evangelist Billy Graham tried to walk the tightrope between King and segregationists like Texas Governor Price Daniel (D), arguing for racial harmony and disavowing the outright racism of old-school Protestants like Bob Jones, Sr., yet opposing legal integration and civil rights because “you can’t legislate morality” and opposing civil disobedience out of respect for the law. King seemed to call Graham and his flock out in Letter From Birmingham Jail, lamenting having to watch “white churches stand on the sideline and merely mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities.” But, realistically, the road to legal progress ran through more progressive white Christians along with white politicians such as Robert Kennedy, shown above and to the right speaking to a CORE gathering when he served as Attorney General under his brother John. The biracial Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party broke away from the mainstream Democrats in that state to demand representation at the 1964 Democratic convention, about which more below.

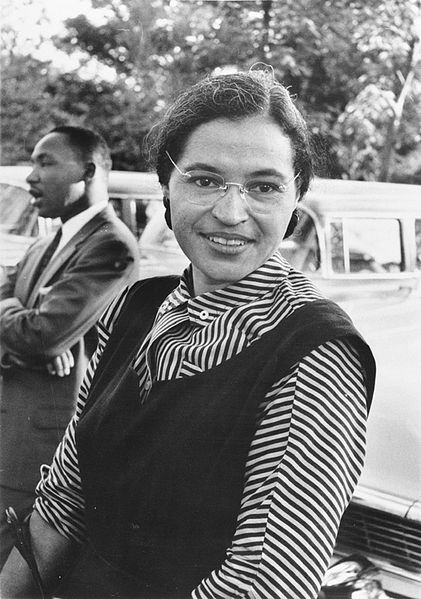

Typical of the non-violent movement was Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat at the front part of the back “colored” section of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama in 1955, when the front white section filled. Parks, a home-front worker at Maxwell Air Base during World War II, belonged to the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which had a long history of staging such protests, dating back to Philadelphia in the early 19th century. Parks had helped advocate for the forenamed Recy Taylor. Earlier that year, young women led by Claudette Colvin were arrested for not sitting in the designated black seats on a Montgomery bus. But given Colvin’s youth, volatility, and history of out-of-wedlock pregnancy, the NAACP picked Parks to be the public face of the protest (the same way the Dodgers had picked Jackie Robinson to integrate baseball). The resulting boycott of Montgomery’s public transit led to the integration of their system and made Dr. King a household name. It also included white allies who worked with African Americans to form networks of bikes, taxis, carpools, and horse-drawn buggies to enable the bus boycott.

Boycotts are a classic example of passive resistance dating to the American Revolution, when they were used effectively to check British authority and mercantilist trade policies. The Montgomery incident was also typical of this early phase of the movement insofar as it took place in the urban South and took aim at segregation in public facilities. Groups like the NAACP and SCLC used the courts to force integration in public education and transportation, combining W.E.B. Du Bois’ emphasis on legal/constitutional challenges with Booker T. Washington’s emphasis on schools and public institutions. In 1956, SCOTUS ruled in Browder v. Gale that state-mandated segregation in public transportation was unconstitutional.

The old separate but equal interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment that held for half a century after Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896) fell in two cases involving public education: Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and Brown v. [Topeka] Board of Education (1954) — both argued by Thurgood Marshall, who later became America’s first black Supreme Court Justice. Marshall partnered with then clerk Constance Baker Motley (right) to spearhead Dubois’ legal/constitutional line of attack. Heman Sweatt, the grandson of slaves, was admitted to the University of Texas’ “separate but equal” black law school. It was basically an empty desk in the basement with a used textbook on it and no professors or classes. UT scrambled to build Texas Southern, a black college in Houston, as the case made its way through the lower courts, but eventually lost in the Supreme Court, forcing the school to integrate its classrooms. The Klan terrorized Sweatt on UT’s campus, burning crosses and slashing his tires as the Austin police did nothing, but the case set a precedent for a broader ruling affecting K-12. Meanwhile, the University of Virginia was going through a similar experience and convinced African American Gregory Swanson to drop out.

The old separate but equal interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment that held for half a century after Plessy vs. Ferguson (1896) fell in two cases involving public education: Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and Brown v. [Topeka] Board of Education (1954) — both argued by Thurgood Marshall, who later became America’s first black Supreme Court Justice. Marshall partnered with then clerk Constance Baker Motley (right) to spearhead Dubois’ legal/constitutional line of attack. Heman Sweatt, the grandson of slaves, was admitted to the University of Texas’ “separate but equal” black law school. It was basically an empty desk in the basement with a used textbook on it and no professors or classes. UT scrambled to build Texas Southern, a black college in Houston, as the case made its way through the lower courts, but eventually lost in the Supreme Court, forcing the school to integrate its classrooms. The Klan terrorized Sweatt on UT’s campus, burning crosses and slashing his tires as the Austin police did nothing, but the case set a precedent for a broader ruling affecting K-12. Meanwhile, the University of Virginia was going through a similar experience and convinced African American Gregory Swanson to drop out.

In 1954, the Court integrated all U.S. public schools in the Brown v. Board case. UT protested these cases by naming a dorm after Confederate soldier, KKK leader, and law professor William Stewart Simkins (they changed the name in 2010). President Dwight Eisenhower wasn’t a big fan of the Brown ruling, either. He’d appointed Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren, who’d overseen Japanese internment camps as California’s Attorney General, under the impression that he was more conservative. Eisenhower overlooked that California had integrated its schools under Warren. Even before Sweatt, Mendez v. Westminster (1946) outlawed segregation in California’s public schools, though that case didn’t challenge the separate but equal clause directly. Likewise, Texas state courts partly integrated their schools by re-classifying Mexican-Americans as white in Delgado v. Bastrop Independent Schools (1948). With President Eisenhower unenthused, not much happened in the immediate aftermath of Brown v. Board regarding enforcement of integration in the nation’s schools. But Eisenhower advocated ending segregation in the District of Columbia and, more importantly, protecting Blacks’ right to vote. He also signed the watered-down 1957 Civil Rights Act that added a civil rights division to the Justice Department but didn’t include any voter protection. Another bill passed in 1960 that gave the federal government the right to inspect voting polls, a precursor to stronger legislation in 1965. NAACP leader Roy Wilkins called these diluted bills “soup made from the bones of an emaciated chicken who’d starved to death.”

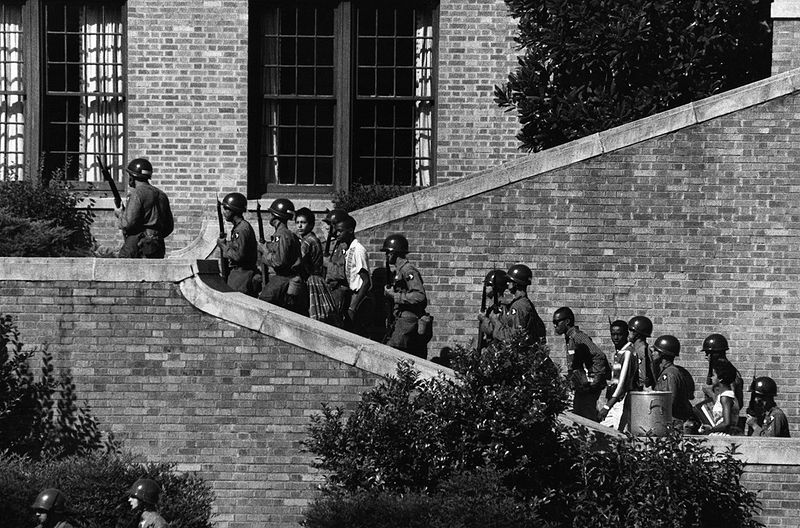

Most famously, Ike took a stand against the Arkansas National Guard being used to keep black students out of Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957. He didn’t like a state so brazenly defying a Supreme Court ruling, even one he didn’t personally support, and he knew that American racism was feeding Soviet propaganda. Communists everywhere, including Cuba, cited the U.S. as an example of how democracies mistreat minorities. Ike sent in troops and federalized the Guard, as presidents can do through executive order. The 101st Airborne Division escorted the same Little Rock 9 (black students) into the school that the Guard had just kept out before it was federalized. Whites threw acid in one black girl’s eyes and a few tried unsuccessfully to burn her alive in the girls’ bathroom.

Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus eventually closed all the city’s public schools to protest the courts rejecting an appeal to delay integration a few years. The Little Rock incident was ironic since Eisenhower privately opposed school integration but felt obligated to honor the Supreme Court whereas Governor Faubus privately supported integration but opposed it publicly to support his state. Ike and Faubus met ahead of time to choreograph their showdown appropriately. It was the first show of federal force in the South since Reconstruction but didn’t do much to actually integrate schools across the country. Over a hundred congressmen signed the 1956 Southern Manifesto opposing integration in schools or elsewhere. White Flight suburbanization and lack of compliance mostly saved Whites from the feared indignity of their kids sharing classrooms with minorities. Public pools followed a similar pattern of “desegregation without integration” as Whites across the country abandoned integrated public pools in favor of suburban public pools, backyards or private country clubs. In such scenarios, poor Whites lost public facilities as unintended victims of structural racism.

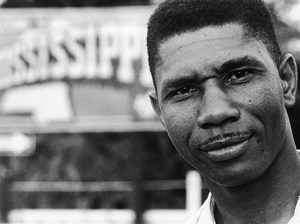

Whites demonstrated similar resistance in higher education at the Universities of Alabama and Mississippi, nicknamed Ole’ Miss for a term enslaved workers used for their masters’ wives. At the Ole’ Miss Riot of 1962, federal troops sent in by President Kennedy overcame protesters, including one fraternity led by future U.S. Senator Trent Lott, to escort in black WWII combat vet James Meredith. An all-night riot killed two people and students worked in shifts to taunt and harass Meredith the rest of the semester, with one bouncing a basketball above his dorm room all night every night. Some white students dropped out while others rallied around Dixiecrat Governor Ross Barnett and the Confederate flag at Rebel football games. Ole’ Miss’ integration claimed another life indirectly, that of WWII veteran and NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers. Evers was most famous for investigating the Emmett Till murders, and there were several attempts on his life before racists shot him in the head on the heels of Ole’ Miss’ integration in 1963.

At the University of Alabama, similar rioting ensued and Governor George Wallace (D) took advantage of the media exposure. Just as civil rights advocates could take advantage of photojournalism and film, so too could its opponents — in this case from “the cradle of the Confederacy and very heart of the Anglo-Saxon Southland” as Wallace put it (South Carolina might have contested the first part). The WWII vet and former boxer and judge had been a New Dealer who initially resisted the Dixiecrats splintering from the Democrats. He even called African Americans “mister [last name]” from the bench, which was rare among judges at the time. But Wallace lost Alabama’s gubernatorial nomination in 1958 to a Klansman. He vowed he’d never “get out-[N-word]ed” again, apologized for not joining the Dixiecrats in 1948, and won the gubernatorial race in 1962. Evoking the Civil War and Reconstruction, the man SNCC co-founder Julian Bond called the “Hillbilly Hitler” pledged to take on the “integratin’, scalawagin’, carpetbaggin’ liars from the North” who were trying to ram integration down white Southerners’ throats. President Lyndon Johnson, a southerner himself who by the early 1960s was wrangling with the more racist wing of the party, called Wallace a “turd in the crystal bowl.”

With the cameras rolling in 1963, Wallace blocked the entrance to the University of Alabama and gave the pro-segregation speech that helped launch him to national fame and a presidential run in 1968. He plucked his most famous quote at the Stand in the Schoolhouse Door from his inaugural speech the year before: “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” After the Guard radioed President Kennedy, the governor stepped aside to allow students Vivian Malone and James Hood through the door, while Wallace promised “rebel protest…against communistic amalgamation.” We slip into thinking that performative politics are a function of social media, but it’s old as politics itself. Wallace lost his presidential bid in 1968 and was shot and paralyzed during the 1972 race, after which country music legends George Jones and Tammy Wynette headlined a “Wallace Woodstock” fundraiser. As we learned in the previous chapter, he successfully won re-election as Alabama Governor in 1982, asking forgiveness from the black community. Wallace said, “I was wrong. Those days are over and ought to be over.”

Public schools that allowed Blacks too much access incurred the wrath of politicians. The University of Texas allowed its first class of African-American students in 1956, earlier than most Southern schools. It was costly, though, as they had to re-do all their plumbing so the races weren’t sharing bathrooms or drinking fountains. Today you can still see marble slabs next to drinking fountains where they removed the secondary plumbing in the 1970s. Black music major Barbara Smith Conrad won a part as the Queen of Carthage opposite a white male in the Opera Dido & Aeneas. After several campus groups and parents protested, the controversy spread to the state legislature and garnered national coverage. The music department had to remove Conrad from the role to preserve UT’s state funding, the loss of which at the time would’ve led to UT’s closure (today the state only provides 12% of UT’s funds). Harry Belafonte financed Conrad’s move to New York, where she became a successful mezzo-soprano, and UT stayed open. Dwonna Goldstone’s Integrating the Forty Acres (2006) chronicles UT’s racial history for students interested in further reading.

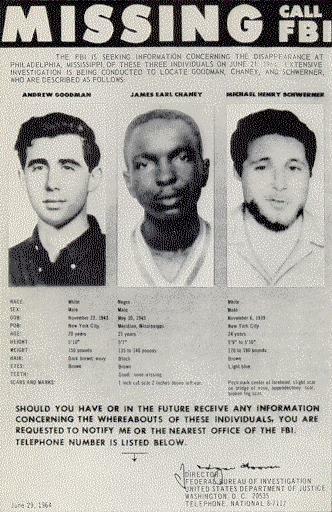

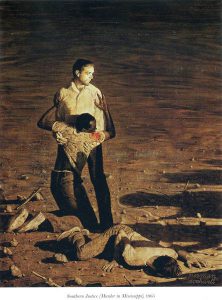

Schools were just one part of the controversy stirring across the country, but the mixed-race leads in the UT opera symbolized part of the problem. Many southerners resented the interracial aspect of the early civil rights movement, especially if Yankees were involved. In Philadelphia, Mississippi in 1964, the White Knights branch of the KKK killed three civil rights workers, including one Black and two Jewish New Yorkers, and buried their bodies in an earthen dam. The volunteers were part of the Freedom Summer project based at Miami University (of Ohio), where SNCC trained Whites to help Blacks register to vote in Mississippi. The project’s story and the fate of the three volunteers later inspired the movie Mississippi Burning (1988). At the time, the tragedy inspired painter Norman Rockwell (right), who was known mainly for decades worth of all-American, main street scenes on Saturday Evening Post covers.

As in the Emmett Till case, the perpetrators thought they could escape justice. Why wouldn’t they? Their own sheriff engineered the killings and the original jury was white. This time, though, the FBI and Justice Department intervened, leading to the conviction of seven of the eighteen conspirators in U.S. v. Price (1966). When the White Knights firebombed the home of civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer in Hattiesburg, Mississippi three years later, killing him, the FBI even enlisted mobsters to pistol-whip confessions out of the perpetrators. The Mafia and Klan had a combative history dating back to the Prohibition era.

Reconstruction 2.0

The early 1960s saw racial changes more dramatic than any the country had seen since Reconstruction 1.0 after the Civil War (1865-77). Mississippi and Alabama were the epicenters of protest and reprisal. In 1963, activists lured Birmingham mayor and former Klan member “Bull” Connor into using attack dogs and fire hoses on innocent teenagers, turning public opinion against the oppressors for those who saw the news coverage. It was a classic case of political jujitsu, or turning an opponent’s force against him. “Bombingham” was notoriously violent, partly because dynamite from local quarries was used for dozens of fire-bombings inflicted on black homes and churches. Birmingham was also home, at times, to Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK) and his family.

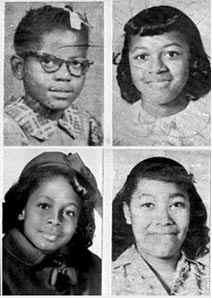

The KKK’s White Knights blew up the 16th St. Baptist Church in September 1963, killing four girls in a terrorist act that swung public opinion more in favor of the civil rights movement. In the Freedom Summer of 1964, the forementioned volunteer campaign to register black voters in Mississippi, racists burned 35 black churches and, echoing Tulsa 1921 and Germany’s Kristallnacht 1938, destroyed 40 black businesses. With MLK in a Birmingham jail, younger protesters hit the streets to keep the movement alive. Protests in Birmingham and in Montgomery, Alabama morphed into a major march on Washington in 1963, where King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. He’d given the same speech several times already, including in Detroit two months earlier to a crowd of over 100k.

Although he and Bobby helped get MLK released, President Kennedy feared violence and tried to talk black leaders out of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He expressed public support for a peaceful march as he was starting to rally support for a civil rights bill, but he didn’t want a march on the capitol building, especially, and authorized use of federal troops to control protestors. March leaders agreed to rally at the Lincoln Memorial instead of the Capitol, and organizers struck the portion from SNCC Chair John Lewis’ speech where he threatened a non-violent version of “Sherman’s [Civil War] March through the South.” Lewis didn’t mention Sherman but used the term black instead of negro, which was cutting edge in the early ’60s. Kennedy was willing to tolerate the march as long as King fired two purported communists in the SCLC, Jack O’Dell and Stanley Levison, men that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover claimed to know were communists from wiretaps. King fired the African-American O’Dell but retained the white Levison, though the tapes revealed no evidence of communist ties for either man.

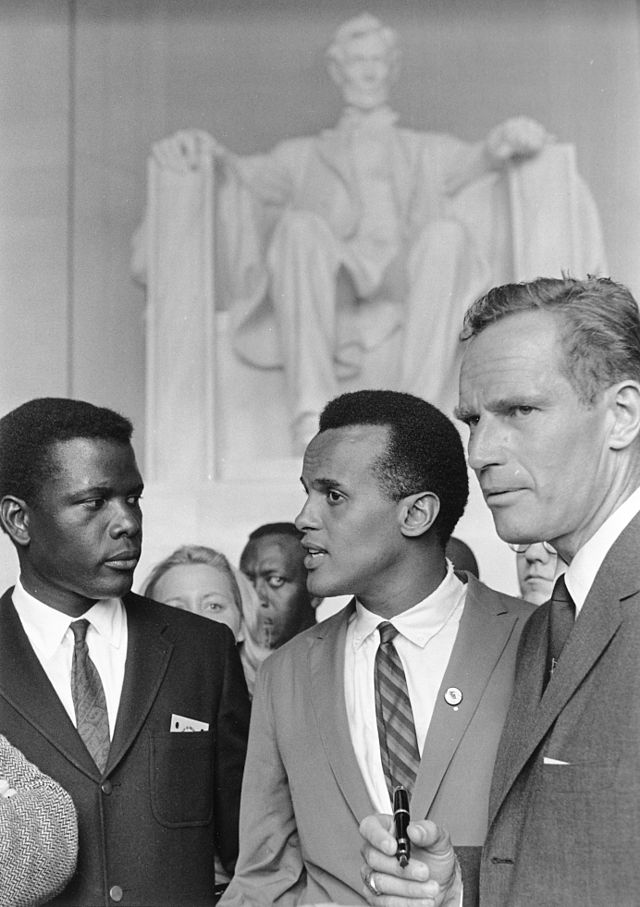

The person A. Philip Randolph and MLK put in charge of organizing the March on Washington, Bayard Rustin, had leftist leanings and was gay. Yet Rustin was able to muster celebrity support in Hollywood, led by “chairman” Charlton Heston and including Marlin Brando, Steve McQueen, James Garner, Paul Newman, Burt Lancaster, and Tony Bennett. A critical balance in Hollywood had swung left since the blacklistings of the early Cold War. White folk singers Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and Bob Dylan sang to the “salt and pepper” audience. Harry Belafonte rallied support among African-American celebrities like singers Sammy Davis, Jr., Marian Anderson, and Lena Horne, author James Baldwin, and actor Sidney Poitier.

They and the rest of the audience perched in trees and gathered around the Lincoln Reflecting Pool and at home on television heard Reverend King give his inspirational sermon in which he put the civil rights movement in the context of American democracy as a whole. If they’d seen the dark side on TV months earlier from Birmingham, they saw the best that day. In his “I Have A Dream” speech, King didn’t say, “We have a radical new idea that will take some getting used to because none of you have heard of it and will involve tearing down American civilization.” He said the Founders had issued a promissory note [Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence] and “it is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’” This appeal only made sense in a country where some sort of obligation, however unfulfilled, was understood to have existed in the first place. No Declaration, no MLK. When King followed, optimistically, that “We refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt,” a critical balance of white Americans understood what he meant. Historian Yoni Applebaum wrote: “The United States possesses a strong radical tradition, but its most successful social movements have generally adopted the language of conservatism, framing their calls for change as an expression of America’s founding ideals rather than as a rejection of them.” Conversely, movements predicated on more radical change, like completely overturning capitalism, are doomed to failure in the U.S., or at least have been so far. Of course, this strategy only makes sense in a society with an imperfect liberal tradition to fall back on; it wouldn’t hold for rebels living under authoritarian rule.

Following King’s speech, the main speakers walked directly over to the White House for photo-ops and handshaking with President Kennedy, who was no doubt relieved things had gone well.

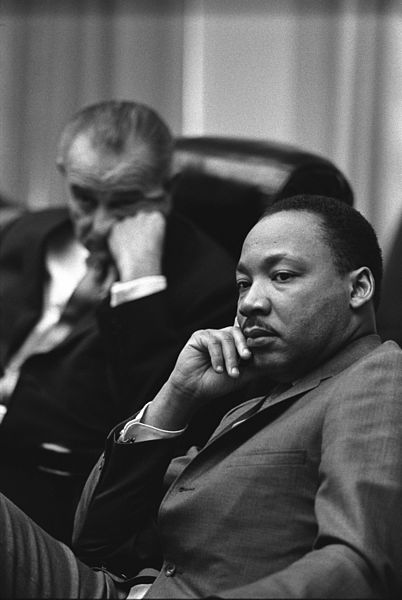

The March on Washington and events in Alabama and Mississippi contributed to major civil rights legislation the following year, passed after Kennedy’s assassination. Kennedy had opposed civil rights legislation as a senator in the 1950s, hoping to court southeastern votes for a future run at the White House, but he evolved gradually once in office. MLK said that “at last we finally have a president with the intelligence to understand the problem, the political skills to solve it, and the passion to see it through…I’m certainly convinced of the first two.” Kennedy was an incrementalist that didn’t want to push too fast, fearing that would endanger the movement. In the first two years of his presidency, JFK was mostly just annoyed that civil rights demonstrations like sit-ins and the Freedom Rides interfered with his focus on foreign policy and the Cold War. One of JFK’s first decisions was to disinvite black Ratpacker Sammy Davis, Jr. from the inaugural ball when he discovered that his wife was white (that led Dean Martin but not Frank Sinatra to boycott the event). But in the last year of his life, provoked by the church bombing in Birmingham, Kennedy developed the passion that MLK hoped for, declaring that “race has no place in American life or law.” Birmingham had a similar effect in Kennedy as Isaac Woodard’s mutilation had on Truman in 1946. JFK said, “We face a moral crisis…it is time to act.” Just before Kennedy’s assassination, he told Walter Cronkite in a CBS interview that he’d be willing to sacrifice the votes of southern states in his 1964 re-election bid, especially since many there didn’t like him much anyway.

Like Booker T. Washington’s gradualism in the early 19th century, Kennedy’s incrementalist idea wasn’t entirely without tactical merit, given peoples’ resistance to sudden change. But by the mid-20th century, such arguments had long since outlasted their shelf life, used mainly as an excuse for perpetual inaction. Kennedy’s VP, Lyndon Johnson, acknowledged just that in an underrated speech he gave at the Gettysburg Battlefield on Memorial Day 1963, commemorating the centennial of the famous Civil War battle fought there. The speech responded to the promotion of non-violent tactics MLK expressed in Letter From a Birmingham Jail. LBJ said, “For years I’ve heard wait!…It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. The wait almost always meant never. The Negro today asks for justice. We do not answer him — we do not answer those who lie beneath this soil [Union soldiers] — when we reply to the Negro by asking for patience. It is empty to plead that the solution to the dilemmas of the present rests on the hands of a clock.” These were strong words, indeed, coming from a Texan who led the conservative Democrats in the 1950s. LBJ, after all, was who made sure the watered-down 1957 Civil Rights Act didn’t include provisions to protect minority voting rights. But, by the late ’50s, Johnson had started to change and he, along with Al Gore, Sr. of Tennessee, refused to sign the aforementioned Southern Manifesto to resist school integration in 1956. Vice-presidents don’t garner much attention, and LBJ’s quick two-hour round-trip helicopter ride from D.C. to Pennsylvania was lost amidst famous speeches that same year by MLK in Washington and JFK in Berlin. For that matter, Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address wasn’t noticed much in 1863, either. But LBJ was a changed man and the U.S. was in for some dramatic changes of its own.

When JFK died, President Johnson pressured the FBI to crack down on the KKK rather than Martin Luther King (later the FBI tried to intimidate MLK into committing suicide). Though they later split over the Vietnam War, King worked with LBJ the same way Frederick Douglass worked with Abraham Lincoln in the 1860s and A. Philip Randolph worked with Roosevelt, Truman, and Kennedy. Another important conduit between Blacks and white politicians was Whitney Young, president of the National Urban League. Young urged Johnson to commit money to fight poverty in the same way that the U.S. used the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after World War II. Johnson also had an alliance with Texas Hispanics dating back to his teaching days in the Rio Grande Valley and the case of Felix Z. Longoria after WWII. Longoria was a Purple Heart winner who died in the Philippines in 1945, but whose body wasn’t returned to the States until 1949. A funeral parlor in his hometown of Three Rivers denied him wake services (to allow his remains to lie in state) because he was Mexican-American. Freshman Senator Lyndon Johnson worked with the forenamed Dr. Hector P. Garcia to have Longoria interred at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors, along with 18 others. While JFK courted Hispanic voters in his Viva Kennedy drives, with Jackie speaking Spanish, he’d turned his back on them after the election. LBJ, on the other hand, was committed to promoting civil rights for all minorities.

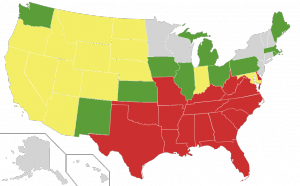

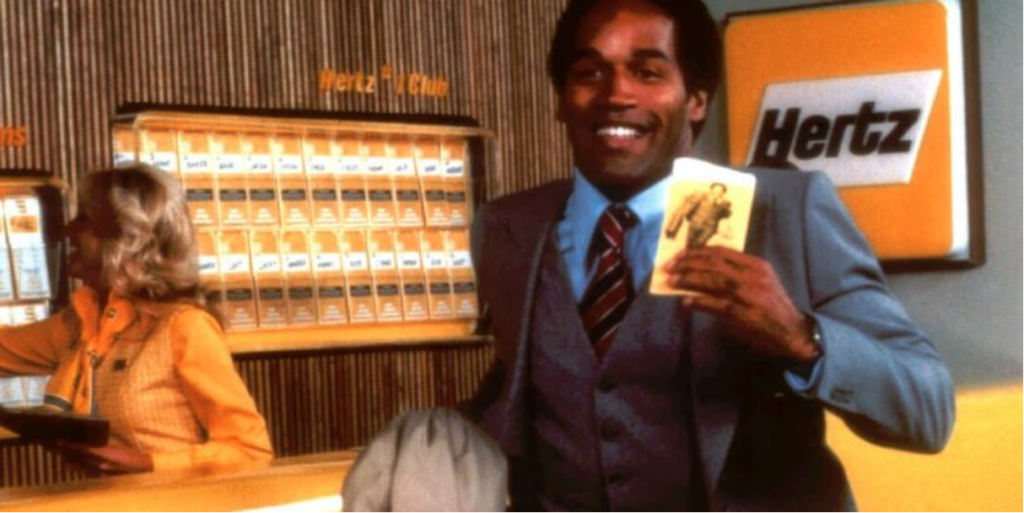

As we saw in the previous chapter, Congress and Johnson signed legislation outlawing racism in public establishments, including privately-owned businesses, with the 1964 Civil Rights Act. That law, along with the Heart of Atlanta Motel court case the same year, beefed up the Fourteenth Amendment considerably to outlaw formal racism anywhere in any state, not just state-sanctioned racism as it had been interpreted since 1883. The Negro Motorist Green Book we saw in Chapter 15, for instance, went out of publication in 1966. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, combined with the Twenty-Fourth Amendment (1964) and Harper v. Virginia (1966) beefed up the Fifteenth Amendment, outlawing all the various excuses states used to keep Blacks and Hispanics from voting like literacy tests and poll taxes. Though presidents don’t have a direct role in amendments, John Kennedy set the Twenty-Fourth in motion by encouraging Congress to introduce the amendment in 1962 and send it to the states. The final version of the 1964 act passed after LBJ called in favors and made deals was exactly the same as the last version JFK saw. Watching news of JFK’s assassination on TV, MLK’s eight-year-old daughter, Yolanda, told her dad “We’re never going to get our freedom now,” but daughter and father were pleasantly surprised that the conservative Texan LBJ grabbed the civil rights baton from JFK.

Just as the protests and bombings in Birmingham led to the March on Washington and 1964 Civil Rights Act, two main developments furthered the cause of voting reform. First, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party — that demanded representation as part of their state’s delegation to the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City — drew attention to voting discrimination even though the group failed at the time to win voting seats. On the right is one of their leaders, Fannie Lou Hamer, a gospel-singing activist who’d been viciously beaten by blackjack-wielding police in Winona, Mississippi. The spirituality of leaders like MLK and Hamer lent the cause moral credibility, helping to steer public opinion in favor of civil rights reform. The public associated that particular type of baton with the Nazi Gestapo and attacking leaders like Hamer allowed cartoonists to lampoon authorities. In contrast to the Civil War era, some white ministers in the South started to lead their flocks toward enlightenment and justice.

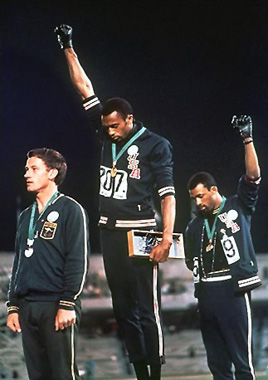

Second, the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery Marches (in the photo at the top of the chapter), led by the SNCC and SCLC, bolstered support for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. This, too, had Christian undertones as the beating death of Baptist church deacon Jimmie Lee Jackson at the hands of Alabama State Trooper James Bernard Fowler spurred the march. Fowler pled guilty to manslaughter in 2010 and was sentenced to six months in prison. State troopers accompanied by deputized, armed citizens met the marchers at the Pettus Bridge east of Selma, attacking them with tear gas, cattle prods, and billy clubs on “Bloody Sunday.” They fractured the skull of the forenamed John Lewis, who served as a Georgia congressman from 1987 to 2020. The sheriff had ordered all white males over 21 in Dallas County to be deputized. Despite the KKK assassinating several leaders, a federal judge granted the protesters the right to march and petition Governor George Wallace at the capital. When marchers finally made it to Montgomery two weeks after Bloody Sunday, they were greeted by a concert featuring Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis, Jr., Joan Baez, Frankie Lane, Nina Simone, and Peter, Paul & Mary. The classically-trained Simone captured the spirit of the era with her angry hit “Mississippi Goddam” (YouTube). LBJ chided Governor Wallace and, two days later, presented a bill to Congress that became the Voting Rights Act. Most bills originate in Congress, but LBJ led the charge himself on civil rights from the executive branch. Johnson echoed the “We Shall Overcome” theme of the Alabama marches when he pressed Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act.

Collectively, the ’64 Civil Rights Act and ’65 Voting Rights Act were the most significant steps forward since Reconstruction a century earlier, or backward for racists and states’ righters. There’s more in an optional section below about how the VRA has been weakened but not overturned in the 21st century. While racism, discrimination, and economic inequality still existed after 1965, minorities had at last won full U.S. citizenship. Reverend King said, “It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important.” After two centuries of resistance, the U.S. had become a full-blown democracy on paper at least, though at this point boys old enough to fight in Vietnam (18) still couldn’t vote because the age limit was 21.

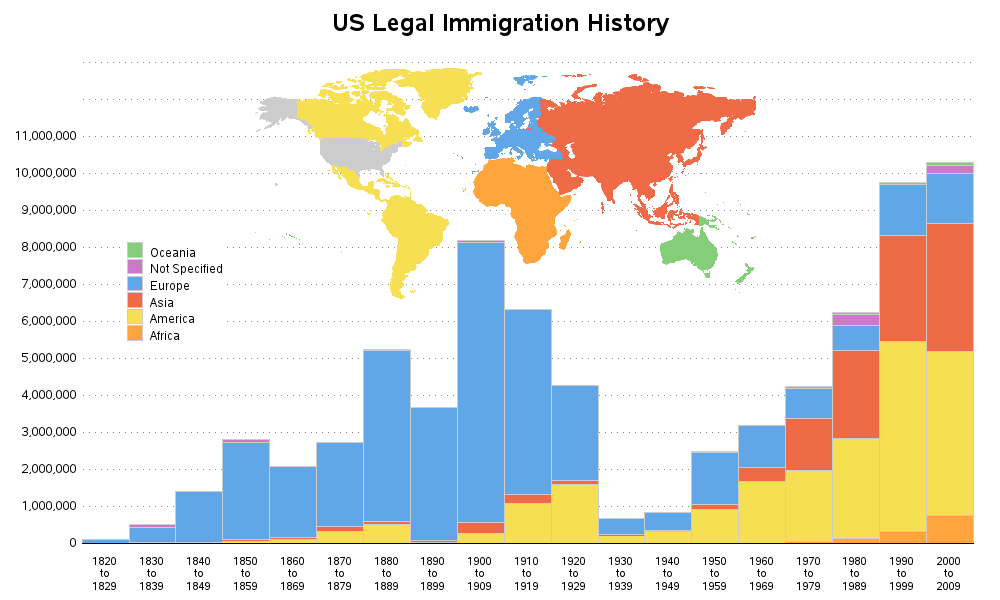

Three other laws/rulings rounded out the famous legislation of 1964 (Civil Rights) and ’65 (Voting Rights). Immigration laws mostly shed their racist qualifications with the 1965 Hart-Celler Immigration and Nationality Act, as the U.S. once again welcomed people from around the world by abolishing the national origins quota system that had been in place since the 1920s and slightly loosened up in 1952. UT Historian Madeline Hsu learned that, while this law occurred during the Civil Rights movement, it was motivated at least as much by Cold War considerations. The U.S. feared, for one thing, that its racism was causing “brain drains” such as Chinese-American engineer Qian Xuesen emigrating to China to seed their space program.

President Johnson sensed that immigration reform wasn’t that popular and Congress pushed the legislation through as quickly and quietly as possible. One of its sponsors, Emanuel Celler, assured the public when asked that it wouldn’t increase immigration from Africa and Latin America very much anyway because it mostly allowed in skilled workers. Politicians didn’t anticipate how dramatically the 1965 law would diversify the United States.

As globalization kicked in by the 1990s, business leaders pushed for lax enforcement of illegal immigration laws, creating a political firestorm that we first explored in detail in Chapter 7. Under the Bill Clinton-era PRWORA Act (1996), legal immigrants can’t receive welfare benefits for the first five years of their citizenship and, contrary to skewed information from the CIS, undocumented immigrants get no benefits beyond public schooling and emergency-room care, though some pay into the system through taxes. The shibboleth that illegals are milking the system is wrong because it’s impossible to receive Social Security or Medicare/Medicaid benefits without a Social Security number. Historian Maddalena Marinari pointed out that a racial hierarchy also emerged within illegal immigration making it easier for undocumented Europeans to attain citizenship than others.

Then, in 1967, the Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law banning interracial couples was unconstitutional per the Fourteenth Amendment, overturning numerous precedent cases and similar laws in fifteen southern states. The Court ruled that marriage was an inherent right. The movie Loving (2016) tells the tale of Richard and Mildred Loving’s nine-year struggle to live as a family in their hometown of Central Point, Virginia. The 2010 Census classified 10% of marriages as mixed-race, 25x more than 1960. Then again, we now know enough about genetics to understand that, in the big scheme of things, all of us are related anyway. Finally, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in 1968 that banned the discriminatory practices in real estate we covered in Chapter 15. The housing act ensconced JFK’s 1962 executive order as part of a bigger bill that also ensured Indigenous Americans protection under the Bill of Rights. These three laws/rulings involving immigration, interracial marriage, and housing are important but less-known aspects of the civil rights movement.

The Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act overcame epic filibusters in the U.S. Senate. Leading Democrat Richard Russell, Jr. of Georgia, LBJ’s old mentor, warned that the new legislation would lead to white slavery, and destroy any chance of opportunity for the ordinary “garden variety type American.” Then, as now, American is often used as code for white. Russell was concerned that giving minorities citizenship would “upset harmonious racial relations.” He was echoing graver concerns of Mississippi’s Governor Barnett, who warned that liberating Blacks would lead to certain genocide for Whites. George Wallace equated white freedom with black oppression: the “federal force-cult”’ was trying to push the white South “back into bondage” with a liberal state more powerful than what “Hitler, Mussolini, or Khrushchev ever had.” Just one southern Democrat voted in favor: referring to Confederate Civil War revisionism, Charles Weltner (D-GA) said “We must not be forever bound to another Lost Cause.”

Victims of the zero-sum fallacy, these politicians couldn’t wrap their minds around a scenario in which neither race discriminated, enslaved, or killed the other, unwittingly revealing much about their subconscious take on white history. They now saw themselves as victims of reverse-discrimination, with “negroes being served everything on a silver platter,” as one put it. There was a grain of truth to the zero-sum line of thinking only for those Whites whose pride and identity was grounded in racism. In a 1971 interview with Playboy magazine, actor John Wayne said, “I am a white supremacist…we can’t all of a sudden get down on our knees and turn everything over to the leadership of the blacks.” To clarify, so far in all of recorded American history not a single person has ever suggested that Whites forfeit their citizenship or freedom or “turn everything over” in the process of granting minorities citizenship.

Senator Russell lamented JFK’s assassination because he was confident the Senate could’ve defeated him on civil rights. As former ringleader of southern Conservatives, LBJ was another animal altogether. By 1964, the first Southern president since James Polk (1849) had dedicated the nation to more truly realizing the idea Jefferson wrote about in 1776. Said Johnson: “We believe that all men are entitled to the blessings of liberty. Yet, millions are being deprived of those blessings…The reasons are deeply embedded in history and tradition and the nature of man…We can understand — without rancor or hatred [toward Whites] — how all this happened…But it cannot endure.”

Houston, Texas felt the impact of these new laws right away. The stadium their Colt 45’s baseball team played in was humid and mosquito-infested. The National League granted them the franchise with the understanding that they’d try to build the first-ever indoor ballpark. At first, they thought they could manipulate the soil and find a way to grow grass through a partly clear ceiling. When that didn’t work, they invented Astroturf (necessity is, after all, the mother of invention). The problem was they needed voters to pass a bond issue to build the new Astrodome and Blacks could now vote. Their only choice was to cave in and allow Blacks to attend events there. Appropriately enough, the stadium opened in 1965 with a Judy Garland and Supremes double billing. You can rest assured that the Supremes, a Motown group, wouldn’t have opened for Garland without the Voting Rights Act. President Johnson attended the Astros’ opening night that month to celebrate the stadium, but everyone understood the city was crossing a bigger hurdle than playing history’s first indoor baseball game. He needed to look no further than the integrated crowd around him to see the impact of the laws he’d signed the previous year.

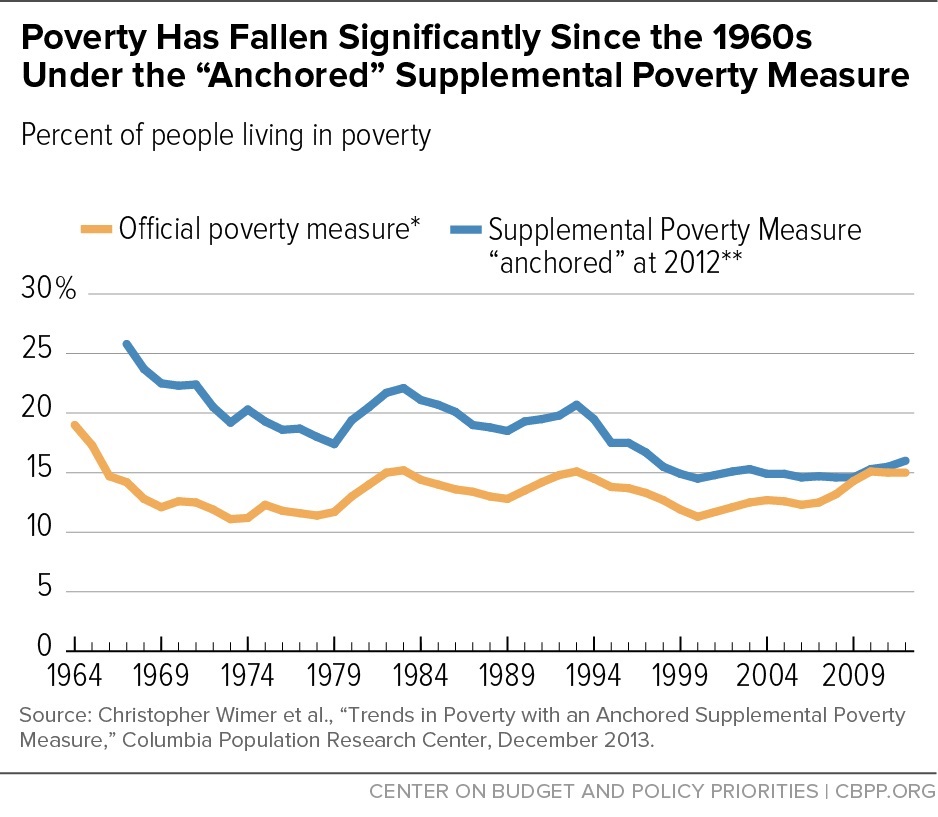

President Johnson’s Great Society had mixed results. Genuine and substantive political gains didn’t translate into dramatic economic reform. MLK understood the economic components of what we call structural or systemic racism and what he called “entrenched financial privilege,” noting late in life that it “didn’t cost a penny” to integrate lunch counters or give Blacks the vote, but creating equitable economic opportunity would cost billions. That’s what the Great Society attempted with mixed results. It lowered the rate of black poverty and malnutrition, affordably despite taxpayer’s complaints, bolstering the black middle class. Among American adults in 2021, 47% of African Americans and Asian Americans qualified as middle class — earning between 43k-130k per year — compared to 49% of Hispanics and 52% of Caucasians (PEW; the figures don’t include those above middle class). The percentage of African Americans without indoor plumbing dropped from 40% to 17% between the 1960 and ’70 censuses. Overall poverty rates dropped, if not as “significantly” as the caption to the right suggests. This success resulted not just from economic aid, but also the various civil rights acts of 1964-68. Yet, minorities lost ground during the Great Recession starting in 2008, with middle-class black and Hispanic net worth dropping nearly 50% initially and the poverty rate going back up to 24% before dropping back down to 18.5% by 2018. As of 2020, the average net wealth of African-American families ($17k) was just one-tenth that of white families ($171k). Prior to the Great Society, net wealth averaged 5% that of Whites instead of 10%, while surveyed Whites estimated that it jumped from 50% to 90%.

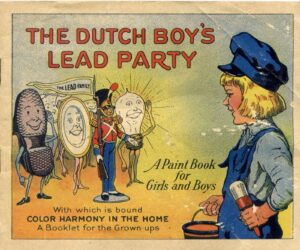

Many African Americans and Hispanics remained in poverty in poor neighborhoods and “second-hand suburbs,” with underfunded public schools and poor municipal sanitation, exacerbated by single-family zoning mentioned in Chapter 15. Veterans were denied benefits and veterans’ widows could be denied pensions based on spurious charges of “immorality” not applied to Whites. The historic legacy of redlining, subprime mortgages, segregation, and neighborhood covenants we saw in chapters 7 and 15 was still in place even after the Fair Housing Act, creating residual, systemic racism, along with food deserts devoid of nutrition. The Trump Management Company’s wrangling with the Justice Department in the 1970s was typical of friction in many cities. African Americans remain far more likely to live in poverty than the rest of the population, and more exposed to pollutants like particulate matter (PM) that damages lungs and likely causes pediatric asthma. The Associated Press ran a series on health disparities among African Americans in 2023 (link). Poor neighborhoods are more prone to lead poisoning from old paint and dilapidated plumbing, with effects too numerous to unpack here. Two recent examples of lead poisoning were in Flint, Michigan (water) and East Chicago, Indiana (soil) in the Calumet federal housing project built atop a former smelter. Poor minorities still live in districts in, or adjacent, to those zoned for industry — aka, fenceline communities — and insurance companies can measure life expectancy by zip code partly for that reason (see the optional article on Dallas, below). Almost all of the garbage incinerators and landfills are near African Americans in Houston, along with most of the petrochemical industry along its Ship Channel. (e.g. Pleasantville). Many minorities and poor Whites live in sacrifice zones beyond any near-term hope for environmental reclamation. How many wealthy environmental skeptics live in fence line communities? That’s holding steady at 0.00.

There’s also a history of medical discrimination too legion to unpack here, ranging from the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-72), in which, without their consent, some African Americans infected with the disease were immunized and others given placebos to serve as controls, to migrants being bathed in kerosene and doused with DDT to rid their bodies of lice (more than 100 men died in the Tuskegee study). Any child without access to a public pool is less likely to learn how to swim and, thus, more likely to drown. African-American women are three times more likely to die during childbirth than white women. School integration hasn’t progressed since the 1980s, which is especially unfortunate given studies showing that African-American children who benefited from busing in the 1960s and ’70s had higher rates of academic success and lower rates of incarceration than those that didn’t. Since American public education is often funded by property taxes, resources and money flow to wealthier kids. Landlords are less likely to rent to minorities with the same financial profile as Whites, and federal rental assistance is essentially a lottery system while, meanwhile, the government continues to pay homeowners through the mortgage-interest tax deduction. Senator Corey Booker (D-NJ) had a white couple stand in with realtors so that he and his wife could buy a house in suburban New Jersey.

The criminal justice system metes out higher bails and longer sentences to minorities than Whites for like crimes and there are even prosecutors who teach workshops on how to toss out minority jurors in the selection process since all-white juries are more likely to convict minorities. African-American men are still targets of racial profiling by police, employers, and other citizens, making it harder to find good jobs. You’ll meet very few law-abiding black men who haven’t been pulled over or strip-searched for no good reason. Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) told NPR he was pulled over seven times in one year in Washington for DWB and was once denied entrance to the Capitol despite showing his Senate badge. A seven-year Stanford study of footage from Oakland Police dash-cams showed that initial greetings between officers and pulled-over drivers were similar across races but that white police explained to minorities why they were being pulled over less frequently and later than they did to Whites. Two-thirds of the time sociologists could determine the race of the driver from the text of the exchange without viewing the footage. African Americans are ~ 5x more likely to be pulled over for traffic stops, and fewer Whites nationwide were shot in stops that originate with trivia like broken turning signals. While studies showed that Blacks were no more likely to abuse drugs than Whites, and no more guilty of violent crimes when adjusted for unemployment rates, young black males filled the rapidly growing prison system in the fifty years after the Civil Rights movement. Blacks were twice as likely to be arrested for drug offenses and 12x more likely to be wrongly convicted of drug crimes. Those released from prison lacked hard-won rights such as voting, and prior arrests made it more difficult to get hired. Predictive policing algorithms used by judges in sentencing just reproduced data already impacted by discrimination in a feedback loop (e.g., the software predicted that future crime would occur in previously overly-policed neighborhoods). With few employment prospects, many cycled back into the prison system (recidivism) in what litigator Michelle Alexander called the New Jim Crow. Those interested in ongoing controversies surrounding structural racism and critical race theory (CRT) should see the optional section below.

Rioting & Police Brutality

The Civil Rights Movement had never been seamlessly unified, but the rupture between the passive resistance phase and a more militant strain grew wider in the mid-1960s, as rioting plagued cities outside the South. And none of the legal reforms of the mid-60s dealt directly with the still-contentious issue of police brutality. One major riot in the Watts section of Los Angeles came just days after passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act. The Watts Riots led to 34 deaths and $40 million in property damage before being put down by 4k California National Guard. Watts got associated with the phrase Burn, Baby! Burn! that, like Defund the Police in 2020, repelled moderates (including many African-Americans) and played into the hands of “law and order” conservatives like Richard Nixon.

Yet, on one revealing memo archived at the LBJ Library in Austin, President Johnson scribbled ”I’d be mad as hell, too” next to a passage on black rioting. He wasn’t referring to the Watts incident in particular. Harlem, Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Newark (NJ) also experienced breakdowns in race relations as police and National Guard struggled to maintain order. One poll showed that Whites who thought LBJ had “pushed too fast” on civil rights jumped from 28% to 52%. One inventory from the 1967 Newark Riots found about 100x more National Guard shells than those fired from the guns of black rioters. Rioting was widespread after Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, with unrest in 125 cities leading to 46 deaths and thousands of injuries. The 82nd Airborne Division surrounded the Capitol with sandbags and gun emplacements. Baltimore never really recovered from the fire damage Blacks inflicted on businesses in their own neighborhoods in the wake of King’s death.

In 1967, MLK said that “a riot is the language of the unheard.” On the surface, there was plenty of blame to go around, starting with Whites’ initial discrimination after the Great Migration, without which none of this would’ve happened, and including outnumbered white police going overboard harassing Blacks, and rioting Blacks killing innocent Whites and destroying their shops. Yet, we also have to ask ourselves about the root cause of rioting, regardless of what transpires. Criminology bibliographer Thomas Kessler wrote of violent uprisings that “understanding and acknowledging a disease is in no way synonymous with endorsing, supporting, or liking its symptoms and effects.”