History sheds some interesting light on the controversial border between Mexico and the American Southwest. It’s important to understand this history as we deal with issues like immigration, language, and labor across the entire United States. First, some geographical background is in order.

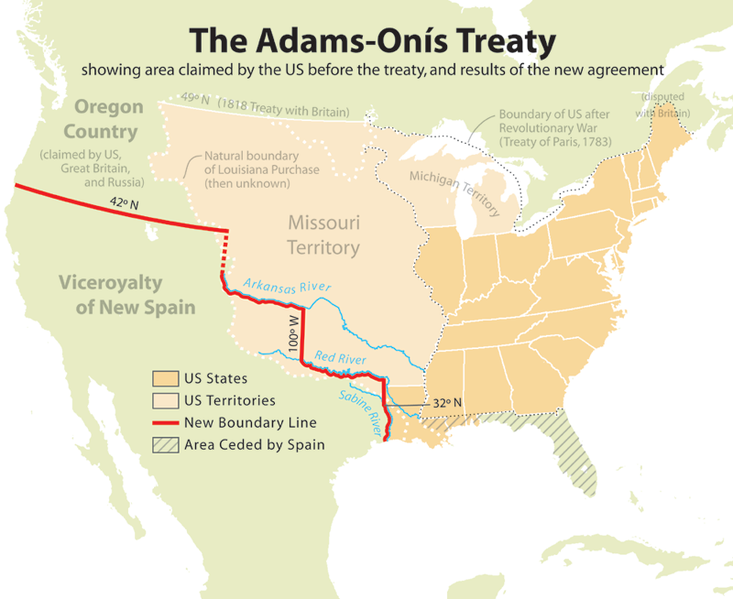

The U.S. signed the Adams-Onís Treaty in 1819, whereby Spain, weakened at home after fending off Napoleonic France, granted Florida — that Andrew Jackson had already invaded anyway — to the U.S., and the U.S. promised to never take the area south of the Red River (i.e. Texas). What’s now central Texas was called Nuevas Filipinas, or the New Philippines. It was a handy treaty from the American perspective because Spain ceded independence to Mexico in 1821, and the U.S. didn’t feel it had to abide by the Texas promise since Mexico wasn’t the country it signed the treaty with. Regardless, Mexico encouraged American settlement in its northeastern-most state, renamed after the Caddo word Tejas, to further populate and develop the area. They sold cheap land to Americans. The early Mexican government was beholden to free trade ideals and encouraged American trade. Tejas was sparsely populated and Mexico wanted a buffer of settlers, namely armed Americans, separating its valuable mines to the south from Apache and Comanche invaders who controlled the northern part of their country. Americans, in turn, that lost money in the Panic of 1819 could escape debt collectors by crossing the international border into Mexico. And land was much cheaper than in the Southeast, where the acronym GTT left on a sign meant “Gone to Texas.”

Early recipients of these Mexican land grants were called empresarios, among whom the most famous and important were Moses Austin and his son, Stephen. Empresarios would learn Spanish and pay the Mexican government around $30 U.S. dollars (~$800 today) after six years if they successfully developed the land. They parceled out their land, in turn, to other settlers — in the Austins’ case the Old Three Hundred between 1822 and 1828. Stephen extended the settlers’ new lands from the Brazos to the Colorado River.

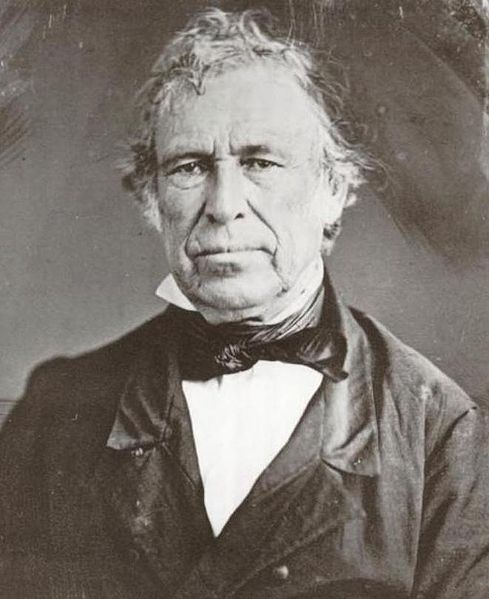

Stephen F. Austin (left) appreciated Mexico’s generosity and encouraged his fellow settlers to learn Spanish and serve in the Mexican military. That was partly because he stood to gain more land from Mexico the more people he drew in. But, despite signing contracts promising to speak Spanish and convert to Catholicism, most subsequent Americans didn’t come to acculturate as Mexicans, but rather to Americanize the region. It was the height of the Jacksonian Era and the U.S. was bursting at the seams with ambitions of western migration. And East Texas defined the western boundary of King Cotton.

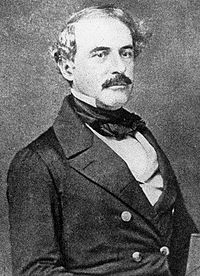

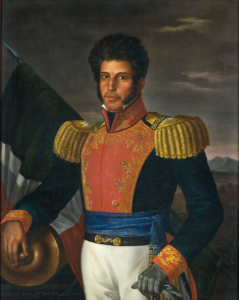

Many settlers were cotton planters who brought a dedication to states’ rights and slavery with them; only now, the national power in question was Mexico’s. Spreading slave economies was a core motivation for Americans to expand into Florida and Texas. That’s one reason why Texas, today, has the largest African-American population in the United States (Hispanic Texans are second behind California). But, under President Vicente Guerrero (right), Mexico mostly abolished slavery in 1829 and made Catholicism their state religion — both affronts to slaveholding Protestants accustomed to religious freedom. Most slaveholders didn’t comply while others forced their workers at gunpoint to sign lifetime indentured servant contracts. To tame the independent-minded gringos, Mexico set up customs offices, quit selling them cheap land, and tried to cut off immigration from the U.S. in 1830. However, it was too late.

Many settlers were cotton planters who brought a dedication to states’ rights and slavery with them; only now, the national power in question was Mexico’s. Spreading slave economies was a core motivation for Americans to expand into Florida and Texas. That’s one reason why Texas, today, has the largest African-American population in the United States (Hispanic Texans are second behind California). But, under President Vicente Guerrero (right), Mexico mostly abolished slavery in 1829 and made Catholicism their state religion — both affronts to slaveholding Protestants accustomed to religious freedom. Most slaveholders didn’t comply while others forced their workers at gunpoint to sign lifetime indentured servant contracts. To tame the independent-minded gringos, Mexico set up customs offices, quit selling them cheap land, and tried to cut off immigration from the U.S. in 1830. However, it was too late.

Heightening the tension, Mexico experienced a counter-revolution in its early history, with a dictatorship run by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna replacing its original republic. Mexico’s early political history was chaotic, with 14 men serving as president between 1824 and ’44. Tejas governor Agustín Viesca opposed this authoritarian trend, as did fellow politician José Antonio Navarro, who’d been an enemy of Santa Anna’s since Santa Anna sided with Spanish Loyalists during Mexico’s long struggle for independence from 1811-1821. Santa Anna plundered San Antonio de Béxar in 1813 during that war — a preview of things to come. A rough counterfactual analogy to Santa Anna would be if a former British loyalist had become U.S. president around 1800 and started to dismantle representative government in favor of authoritarian rule.

As relations worsened, the diplomatic Austin served as a go-between, lobbying the central government to at least separate Tejas as a single independent state from its neighbor to the southwest, Coahuila. The two were originally bound together as a double state, Coahuila y Tejas. Meanwhile, Austin encouraged white Texians (or Texicans, Texonians or Texicanos) to honor their Mexican citizenship. But just as the British lost a key ally and supporter in Benjamin Franklin by castigating him after the Tea Party, Mexico alienated their biggest Anglo ally, Austin, by jailing him in Mexico City. On his way home from Mexico City, the erstwhile loyalist who once championed Mexican citizenship picked up works on the English Revolution of 1688 and decline of the Roman Empire in a New Orleans bookstore.

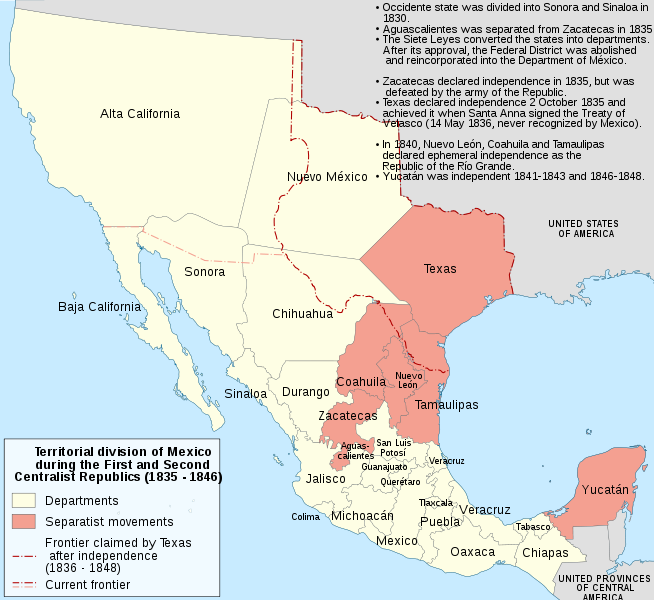

Tejas was one part of a broader-based rebellion against the increasingly authoritarian and centralized Mexican government. Separatist movements were brewing in the salmon-colored areas in the map on the left. Santa Anna was also tightening up trade restrictions, making it harder to ship tools and materials in and out of Mexico. In 1835, the Texians grew unruly, seizing fortifications and the “come and take it” cannon at Gonzales, and surrounding the missionary-turned-presidio (fort) in San Antonio known as El Alamo. They were victorious in the Siege of Béxar, the first and less famous Alamo battle. They allowed trapped Mexican soldiers to escape but declared independent statehood within Mexico. They also took the state’s other key fort, Presidio La Bahía in Goliad.

Tejas was one part of a broader-based rebellion against the increasingly authoritarian and centralized Mexican government. Separatist movements were brewing in the salmon-colored areas in the map on the left. Santa Anna was also tightening up trade restrictions, making it harder to ship tools and materials in and out of Mexico. In 1835, the Texians grew unruly, seizing fortifications and the “come and take it” cannon at Gonzales, and surrounding the missionary-turned-presidio (fort) in San Antonio known as El Alamo. They were victorious in the Siege of Béxar, the first and less famous Alamo battle. They allowed trapped Mexican soldiers to escape but declared independent statehood within Mexico. They also took the state’s other key fort, Presidio La Bahía in Goliad.

Santa Anna returned the following spring, 1836, flying a red flag of no quarter and aiming to put the Texians in their place. Two main roads led into Texas: one through Goliad near the Gulf Coast, and the other through San Antonio de Béxar defended by the Alamo. The white troops awaiting Santa Anna in the spring of 1836 were not just empresarios; they included Americans from all over who had followed the story in newspapers that winter. They described Catholic Mexicans as “tyrannical butchers in the service of the Pope.” W.B. Travis was an Alabama slaveholder, Jim Bowie was on the run from the law, and Tennessean Davy Crockett was a former U.S. senator looking to re-establish himself politically.

Portrait of David Crockett, by John Gadsby Chapman, Harry Ransom Research Center, University of Texas

Crockett was a frontier politician in the (Andrew) Jacksonian mold, famous for purportedly killing copious bears. But he broke with Old Hickory over the expulsion of eastern Indians, opposing what came to be known as the Trail of Tears. Upon arriving in Tejas, he agreed to serve in the militia to qualify for free land. By 1836, this was as much an American, as Texian, fight. The story unfolded just as the U.S. was starting to look west beyond the Mississippi and embrace Manifest Destiny, and just as steam presses increased papers’ circulations.

Tejanos were also in the Alamo — Mexican states’ righters, in this case, allied with white rebels. Tejanos were early advocates of American immigration to develop the northern economy and they supported slavery. There were also centralist supporters of Santa Anna in Tejas, especially in the southeast around Victoria.

Santa Anna’s troops surrounded the Alamo and the rebels inside fought heroically but lost after a 13-day siege, highlighted by a climactic 90-minute battle. The Mexican Army band signified their take-no-prisoners “slit their throats” policy by playing the El Degüello “give no quarter” bugle call continuously during the two-week siege. According to soldado José Enrique de la Peña’s memoir — a contemporary, eyewitness primary source now housed at UT’s Briscoe Center for American History — a few straggled out toward the end and were killed, though Santa Anna spared the women, children, and enslaved and sent them off with cash and blankets. Most historians think Davy Crockett was among those stragglers, though Peña didn’t initially know who Crockett was and didn’t revise his account to include the Tennessean until he later read reports in Detroit and New York newspapers and recognized his description. Only a handful of primary sources survived, but they confirm Peña’s account.

The Fall of the Alamo (or, Crockett’s Last Stand, Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, 1903, Texas State Archives

We’ll probably never know whether Crockett surrendered or went down fighting. According to de la Peña’s account, a Mexican soldier took the six white male prisoners to Santa Anna, who asked (in Spanish) “have I not told you before how to dispose of them?” Several soldiers plunged their swords into Crockett, including some into his heart as he lunged desperately toward Santa Anna before dying with an indignant, defiant look on his face. De la Peña wrote that he saw nobility in Crockett’s face and that Crockett bravely endured his torture without complaint. One reason this version of the story didn’t gain traction is that it doesn’t make either side look good. It dilutes the everyone-went-down-fighting version of the American story but also makes Santa Anna seem merciless. Generally, we shift our history around a bit here and there until it sounds like a story we want to hear. The mythologized version — that Anglos fought until the last man standing with Crockett (out of bullets) swinging his flint rifle “Ol’ Betsy” — was especially important to Texans’ identity after Mexican immigration picked up in the 1910s, and Americans were in no mood for Alamo revisionism toward the end of the Vietnam War, when archivists found the diary. In any event, at least most of the people in the Alamo fought to the death and Crockett died bravely even according to real evidence.

Early Hollywood renditions of the Alamo story, including D.W. Griffith’s Martyrs of the Alamo (1915) and John Wayne’s definitive 1960 version, bleached scenes of Tejanos on the inside of the walls to avoid confusing or angering white audiences. But it wasn’t just white Americans vs. Hispanics; it was Mexicans vs. rebellious Anglo and Hispanic Texans. Free Blacks also fought for independence, but not in the second Alamo fight. The 2004 Alamo movie showed a multi-racial force inside the fort but was most controversial because it included Crockett’s (Billy Bob Thornton) surrender as depicted in the primary sources, leading Fox News to urge a viewer boycott.

Early Hollywood renditions of the Alamo story, including D.W. Griffith’s Martyrs of the Alamo (1915) and John Wayne’s definitive 1960 version, bleached scenes of Tejanos on the inside of the walls to avoid confusing or angering white audiences. But it wasn’t just white Americans vs. Hispanics; it was Mexicans vs. rebellious Anglo and Hispanic Texans. Free Blacks also fought for independence, but not in the second Alamo fight. The 2004 Alamo movie showed a multi-racial force inside the fort but was most controversial because it included Crockett’s (Billy Bob Thornton) surrender as depicted in the primary sources, leading Fox News to urge a viewer boycott.

Had Tejanos been in charge of military strategy, they likely would’ve followed their normal pattern of just evacuating the area until Mexican forces left. Mobility had kept them alive during the fighting between Spanish and Mexican forces in the 1810s, and was a primary motive in their keeping livestock rather than growing crops. They thought defending forts trapped the defenders inside, which is exactly what happened to the rebels entrenched in the Alamo.

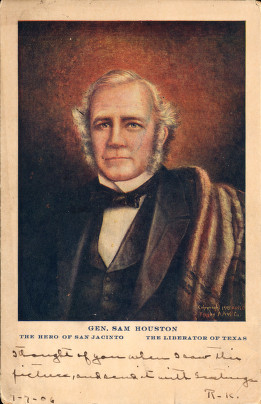

In 1836, the Texian Army to the east led by Sam Houston cut their losses and abandoned those in the Alamo in order to fight another day. In the last entry to his diary, the resentful Travis wrote, “our bones will reproach our fellow countrymen for their neglect.” In his defense, Houston had ordered the San Antonio area evacuated because, like the Tejanos, he knew it would be impossible to defend, so the men who chose to stay behind were defying his orders. Houston just sent them to the Alamo to retrieve the ammo and destroy the fort, but they chose to defend it. Houston hoped they would haul the cannons to Goliad, which was a more strategic spot. Why they stayed is a mystery and some researchers theorize that Jim Bowie might have been protecting buried silver under the Alamo from the San Sabá Mine in the Hill Country west of town. Bowie had fought off Indians hunting for the mine in 1831, with a story appearing two years later in the Saturday Evening Post. Archaeologists even dug up some ground under the Alamo in 1995 looking for the treasure but didn’t find it.

Around thirty men finally made their way from Gonzales to San Antonio for relief in 1836, but it wasn’t enough. At least Houston’s men could cash in on the victims’ martyrdom with one of the most famous rallying cries in history, Remember the Alamo. The Battle of the Alamo was one of the most famous in American history, partly because it symbolized fight-to-the-death heroics and partly because it suggested that Americans were the victims rather than the aggressors in settling the frontier. There’s a notion in history that victors tell the tale, but the tales they choose to tell might not necessarily be victories. Likewise, the other really famous battle in western history was Little Bighorn, or Custer’s Last Stand in 1876. In that case, Indians rather than Mexicans wiped out Whites. In both cases, the tale justified the retribution that followed. On the other hand, recent surveys show that many visitors to Alamo and students of grade-school Texas history aren’t aware of who won the battle despite knowing a lot of its lore and details, in which case this theory doesn’t apply.

Things didn’t go any better — worse, in fact — at Goliad, where Mexicans slaughtered 342 of the fort’s defenders, including their leader Colonel James Fannin, after they surrendered at nearby Coleto Creek. Even more would’ve died if not for the intervention of Francita Alavez, the “Angel of Goliad,” who snuck some out of the fort and persuaded the Mexicans to treat others humanely. The remaining Texian settlers across the state hastily packed whatever they could and high-tailed it for the Louisiana border in the great Runaway Scrape, allowing several enslaved workers to escape in the process (some emigration had been ongoing since the threat of war). One advantage of people vamoosing from an invading army is that the pursuer never expects the pursued army to turn back into them, the way buffalo roam into a storm instead of being chased by it. According to one primary source, Houston may have had no choice. One soldier’s letter read: “The General says he will fly to the Trinity River. The soldiers say, almost to a man, they are determined not to follow him any longer in that direction. I presume, however, that if the soldiers will not follow the General, the General will follow the soldiers.” But Houston may have been luring Santa Anna into a vulnerable position, with San Jacinto Bay behind him. That’s at least the Hollywood version in The First Texan (1956).

Houston and his Army of the Republic of Texas turned and snuck up on Santa Anna’s forces at San Jacinto, a swampy area near present-day Houston. According to legend, the general himself was predisposed with a practitioner of the world’s oldest profession – an indentured servant named Emily West later known as the Yellow Rose of Texas. Houston sent Emily into the Mexican camp and freed her after she accomplished her mission. Other Mexican soldiers were with soldaderas (female soldiers or camp followers) when Texians attacked. Santa Anna was still fumbling with his trousers when Houston’s troops came out of nowhere, routing and brutalizing his men in less than twenty minutes. Recent archaeological research shows that, with the Mexican army firing their cannons over the Texan army, the Texans moved their cannons into closer range. Tejanos like Juan Seguín wore tags on their hats to avoid being killed by friendly fire and one of the best accounts of the battle was chronicled by patriot José Antonio Menchaca.

Houston’s forces had destroyed the main bridge out of the bayou, making it impossible for Santa Anna’s men to escape. Most of the Mexican forces were actually elsewhere and remained intact to still outnumber the Texians. Santa Anna ordered the rest to San Antonio and Victoria to regroup. But, as they retreated to a defensive position between the San Bernard and West Bernard Rivers, they bogged down in what they called the El Mar de Lodo (Sea of Mud), leading to infighting between Generals Vicente Filisola and José de Urrea. As demonstrated by amateur archaeologist Gregg Dimmick MD, torrential rains played a big part in helping Texas gain its independence when it did.

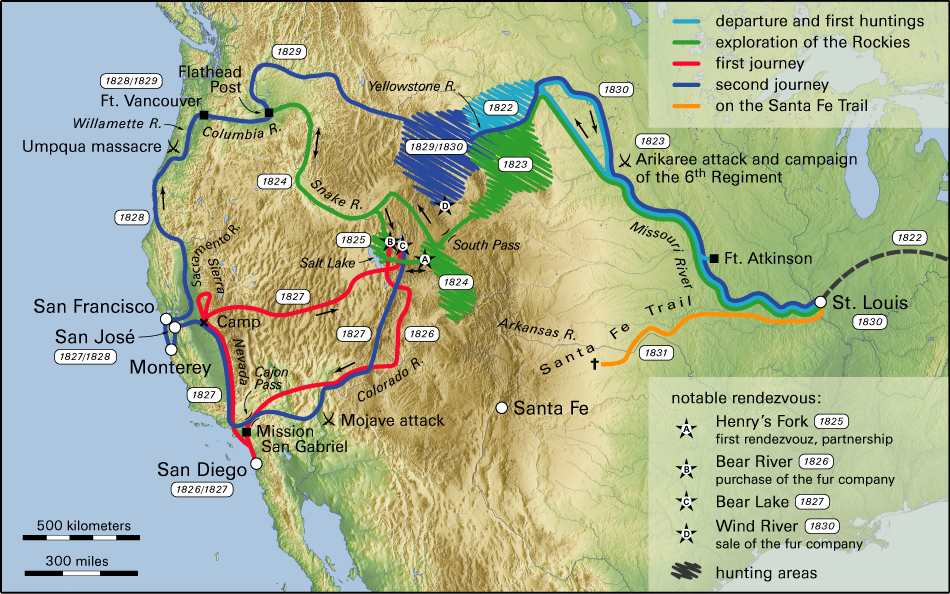

Santa Anna reluctantly signed off on Texas independence from Mexico in the ambiguous Treaty of Velasco, though Mexico denied his authority to sign it. The victors nicknamed their new country the Lone Star Republic because they could now take down the double-starred Coahuila y Tejas flag and replace it with their own single-starred red-white-and-blue national flag of Texas. The Lone Star idea also drew on a similar design by the short-lived Republic of West Florida (1810-1812). Santa Anna later claimed he’d only ceded the area as far south as the Nueces River, rather than the Rio Grande, an important distinction because the Rio Grande River was the main artery connecting the Santa Fe and Rocky Mountain fur trade to Europe. Santa Anna’s forces retreated beyond the Rio Grande, but Mexico later claimed the treaty only ceded land north of the Nueces.

Santa Anna reluctantly signed off on Texas independence from Mexico in the ambiguous Treaty of Velasco, though Mexico denied his authority to sign it. The victors nicknamed their new country the Lone Star Republic because they could now take down the double-starred Coahuila y Tejas flag and replace it with their own single-starred red-white-and-blue national flag of Texas. The Lone Star idea also drew on a similar design by the short-lived Republic of West Florida (1810-1812). Santa Anna later claimed he’d only ceded the area as far south as the Nueces River, rather than the Rio Grande, an important distinction because the Rio Grande River was the main artery connecting the Santa Fe and Rocky Mountain fur trade to Europe. Santa Anna’s forces retreated beyond the Rio Grande, but Mexico later claimed the treaty only ceded land north of the Nueces.

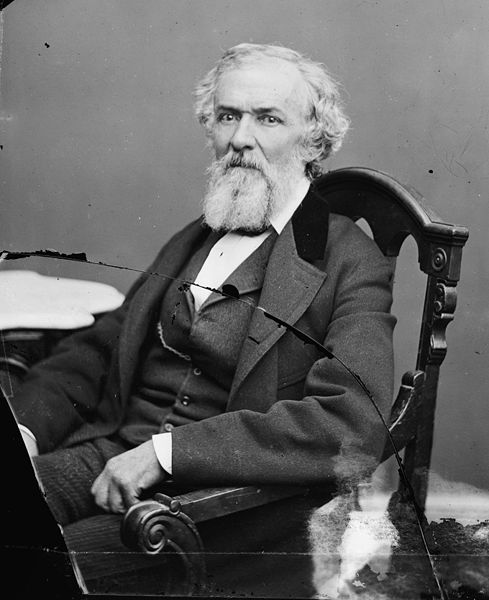

David Burnet was the first president of the new country, but Sam Houston quickly succeeded him. The vice-president was Tejano Lorenzo de Zavala, succeeded by Mirabeau Lamar. Under Houston, the new Republic of Texas (1836-45) expected annexation to the United States, but its admission as a state quickly bogged down in the brewing sectional crisis over slavery and concerns over its debt. Former President John Quincy Adams led the opposition. Texas would throw off the balance between northern and southern states, especially if it could sub-divide into five smaller states, which its constitution allowed for when it finally became a state in 1845.

In the meantime, Houston fended off and courted offers for colonization from France and Britain while the country filled up with Americans. He cleverly played the U.S. and Britain against each other, maneuvering each into thinking he’d go in the other direction, all the while planning on annexation into the United States. Britain would’ve allowed independence within their Commonwealth realm, but had banned slavery in 1833 and insisted that Texas do likewise. Of course they wouldn’t have agreed to that given that was a key reason why they seceded from Mexico in 1836. Houston loved the U.S., would later serve as U.S. Senator in Washington, and was a staunch unionist who opposed Texas’ secession from the U.S. in 1861. After Texas’ admission into the U.S., he became governor. Since he’d been Tennessee’s governor in his earlier life, Houston became the only man in American history to have been governor of two states. As Texas President, Houston even courted colonization efforts from the far-off Ottoman Empire (centered in modern Turkey), wearing the red velvet suit and fez hat they gifted him.

Lamar evicted free Blacks from the state, but Houston reversed that order. While they were at it, Texans also ejected Kickapoo and Cherokee Indians, sending them scattering to Coahuila or back to Oklahoma. And as they gained critical mass, new American arrivals had no appreciation for Tejanos’ participation in the revolution or their rights as citizens, for that matter. They disenfranchised Hispanics and took their land, just as 49’ers would in California. As the saying went, “If a Mexican won’t sell you his land, his widow will.” Seguín, who was elected senator in the new republic and later mayor of San Antonio, had to flee to Mexico in 1842. By then, Hispanics had already left an indelible imprint. As ACC history professor Andrés Tijerina researched, much of what makes Texas distinct — including cattle trails, longhorn herds, mustangs, and mavericks — trace to its Hispanic heritage. American cowboy and rodeo culture grew mainly out of Mexico’s vaquero tradition.

Some argue that the story of Texas represents the triumph of illegal immigration, only the immigration they’re talking about is from the U.S., not vice-versa. It would be more accurate, along those lines of thinking, to argue that it was the triumph of legal and illegal immigration since Mexico’s policy vacillated between allowing and barring American immigration. The important thing is whether the racially dominant group uses its power to protect citizenship or enforce a discriminatory caste system. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century white Texans chose the latter.

Mexican War

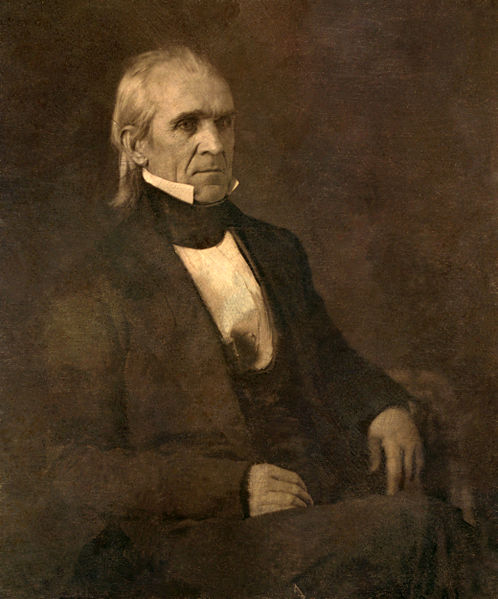

Slavery wasn’t just controversial in the potential new state of Texas. Its continental-wide western extension was so divisive that, during the 1844 presidential election, front-runners like Martin Van Buren and Henry Clay were hesitant to talk about it. That left an opening for dark horse Tennessee candidate James Polk to emerge from the pack by promising both the North and South geographical prizes: Texas, and potentially the rest of the Southwest, would come in as slave territory, and Polk supported U.S. claims on the Oregon Country as potential Free Soil territory. Polk’s strategy dovetailed perfectly with the brewing spirit of Manifest Destiny and seemingly satisfied everyone — other than, of course, the region’s indigenous inhabitants, Mexico, Russia, and Britain.

As we saw in the previous chapter, the U.S. and Britain shared the Oregon Country, which then stretched up to the 54º40′ parallel to include present-day British Columbia, per an 1816 agreement set to expire in 1846. Polk presumed the British wouldn’t be interested in defending such a remote territory with no Atlantic access. But the British called Polk out on his “Bluff and Bluster” strategy of promising 54º40′ or Fight! They guessed that Polk’s real ambition was to conquer Mexico and spread slavery, so they correctly figured he didn’t want two wars at once. He quickly settled for halfsies, with Oregon divided along the 49th parallel — the same straight line extending from Minnesota west. The Brits even wanted the line curved downward at the end to include all of Vancouver Island and Polk again complied. Suffice it to say, Northerners weren’t happy. They questioned why the Oregon Boundary Dispute wasn’t the Oregon War when Polk seemed intent on gearing up for a real one with Mexico.

As Northerners and British rightly suspected, Polk was more dedicated to the cause of spreading slavery into the Southwest than he was tussling with Redcoats over some Douglas Firs and salmon. And he coveted the deep-water ports of San Diego and San Francisco, as did the British and French. But Texas was the top priority. After William Henry Harrison died from pneumonia shortly into his presidency in 1841, his VP John Tyler (the other half of Tippecanoe & Tyler, Too) dedicated himself to acquiring Texas for the U.S. It finally happened toward the very end of his administration, but Mexico never relinquished its claim on Texas, even after Santa Anna’s loss at San Jacinto. They invaded Texas twice in 1842. The U.S. annexed Texas as a state in 1845, severing relations with Mexico, and Polk moved to solidify American claims on the upper half of Mexico.

Similar to its inconsistent trade policies in Tejas, Mexico variously welcomed then banned American trade in Santa Fe. And similar to Tejas, far northern Mexico resisted Santa Anna’s efforts to centralize power. Santa Fe, or La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís (Royal Town of the Holy Faith of St. Francis of Assisi), was a nexus for furs, turquoise, blankets, and silver during the Rocky Mountain trade era of the 1820s and ’30s, and Americans defined Santa Fe as being in far western Texas. By the 1840s, it was too late for Mexico to divert economic traffic along a north-south axis toward Mexico City. Santa Fe was Americanizing, regardless of who its official ruler was. California was too, especially after the establishment of the Old Spanish Trail connecting Santa Fe to Los Angeles. California’s Hispanic population, meanwhile, was sparse, numbering only 3.5k.

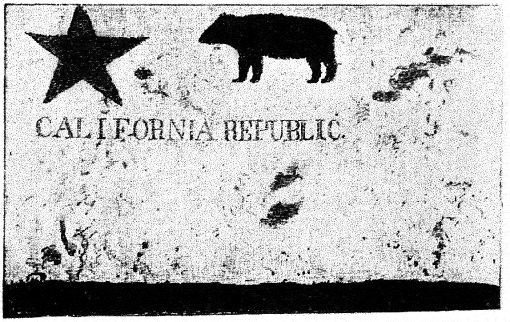

In 1846, California underwent a sped-up version of the Texas independence movement called the Bear Flag Revolt, this one also launched by a biracial alliance but opposed by most Californios, especially those in Los Angeles and San Diego. The white Bear Flag rebels were already squatting on their land by that point, so there was never the strong early alliance enjoyed by Texians and Tejanos, despite an earlier generation of white merchants from the East Coast having assimilated in the 1830s. Having large Anglo populations and American economic control in upper Mexico made the military takeover in California easier than Texas.

In 1846, California underwent a sped-up version of the Texas independence movement called the Bear Flag Revolt, this one also launched by a biracial alliance but opposed by most Californios, especially those in Los Angeles and San Diego. The white Bear Flag rebels were already squatting on their land by that point, so there was never the strong early alliance enjoyed by Texians and Tejanos, despite an earlier generation of white merchants from the East Coast having assimilated in the 1830s. Having large Anglo populations and American economic control in upper Mexico made the military takeover in California easier than Texas.

President Polk offered to buy the upper half of Mexico, the part that really interested the U.S., for $30 million (25 for Upper California and 5 for New Mexico). Undoubtedly, Polk would’ve preferred this situation over war, and it was fair to make the offer, but unreasonable to demand that Mexico accept the offer. Mexico refused diplomat James Slidell’s proposal and another $3.75 million to settle the Rio Grande/Nueces dispute in Texas. Polk either feigned outrage or was genuinely upset at the show of disrespect. “Slidell’s Rebuff” was Polk’s justification for a declaration of war against Mexico. But Mexico refusing to sell half of itself to the U.S. wasn’t the firmest grounds for war, even Polk realized, so he had American troops stir up an incident between the contested Nueces and Rio Grande rivers, which was then tacked onto the war declaration message. Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to march south of the Nueces from Corpus Christi and build Fort Texas across the Rio Grande from Matamoros, Mexico. Mexico took the bait and ambushed Taylor’s dragoons (mounted cavalry), shedding “American blood on American soil” as Polk wrote about what Mexico claimed was a defensive maneuver. With superior numbers, Mexico’s forces defeated American forces upriver from Zachary Taylor’s camp.

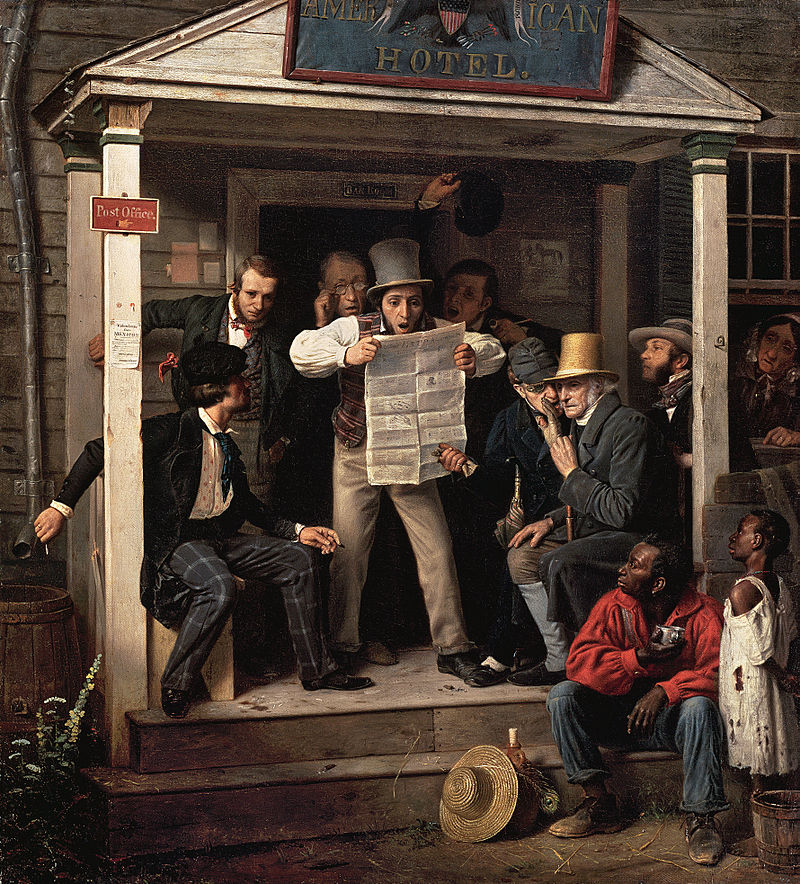

“War News From Mexico” (1848), Richard Caton Woodville, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR

This Thornton Affair, along with Slidell’s Rebuff, was among the “wrongs which were forced upon” the U.S. that Polk listed in his proclamation, in which he asked fellow Americans to “abridge the calamities…with the last resort of injured nations [war].” Ulysses S. Grant, later a famous general in the Civil War, was involved. As he put it, “We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico commence it.” Grant called the war “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.” Manufacturing incidents well is a subtle art, but not everyone bought this one. Whig Congressman Abraham Lincoln attached riders to all his subsequent bills questioning whether the area between the rivers was really even American to start with. They became known as Lincoln’s Spot Resolutions and were virtually the only thing he was known for nationally prior to running for the Illinois state senate in 1858. Ex-president John Quincy Adams said the coming war was for “slave owners and slave breeders,” pure and simple. Henry David Thoreau authored his famous essay Civil Disobedience partly to protest the war. But Congress voted overwhelmingly in favor of Polk’s declaration.

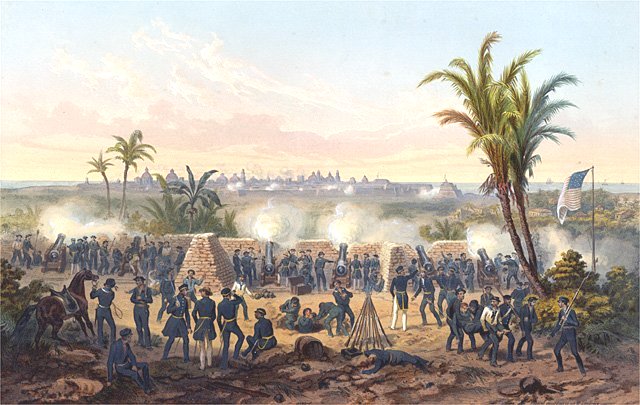

The U.S. easily took control of present-day New Mexico, Arizona, and California in the first year of the Mexican War. Mexico had invaded Texas during its nine-year stint as a nation, but the U.S. solidified its claim on west Texas & the Rio Grande Valley in the first year as well, with Taylor winning two battles along the border at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. The tougher part of the war was the southern half of Mexico. The U.S. sent one invasionary force led by Zachary Taylor south from Texas toward Monterrey while a second led by Winfield Scott landed on the coast at Veracruz. Both moved toward Mexico City despite stiff resistance and struggles with guerrilla fighters, dysentery, malaria, and the latter’s associated, bloody “black vomit” discharge. American troops were outnumbered in most battles but their troops were well trained and they had superior cannons. The Mexican military was antiquated, inefficient, and over-staffed but fought hard to protect its homeland.

The Mexican government changed hands throughout the war, at various points evaporating altogether. There were factions among the wealthy and within the Church that resisted Mexican leadership, including polkos, named for President Polk, who opposed the government confiscating Church property. Meanwhile, 175 Catholic defectors from the U.S. Army in St. Patrick’s Battalion — refugees from the Irish Potato Famine who opposed the anti-Catholic spin on the war — switched sides and fought for Mexico, with the survivors later executed in a mass hanging. Zachary Taylor’s troops conquered Monterrey, but agreed to an armistice and allowed the Mexican troops to escape.

Then Mexico’s exiled leader, our old friend Santa Anna, approached the U.S. with an offer. If they would agree to smuggle him back into the country, he would settle on terms generous to the U.S. They complied but the “Cat with Nine Lives” (Santa Anna) welshed on the deal, brazenly demanding Taylor’s immediate surrender. Taylor exhibited an admirable economy of language in his three-word reply: “Go to Hell.”

By now, Polk wanted to rein in Taylor some and allow Winfield Scott to catch up, and not just for tactical reasons. There was a pattern of successful generals ending up in the White House — Washington, then Old Hickory Jackson, Old Tippecanoe Harrison, and now Old Rough-n-Ready Taylor threatened to make it four, three no less with nicknames starting with Old (later the Lincoln campaign trotted out Old Honest Abe). The easygoing Taylor — a veteran of the 1832 Black Hawk War along with Lincoln and future Confederate President Jefferson Davis — was popular among his men and he didn’t hide his ambition to become president. As it turns out, Polk didn’t run for a second term and Zach Taylor, sure enough, won the 1848 election. That suited Polk since he eventually decided that he preferred Taylor to the other prominent general, Old Fuss-n-Feathers Winfield Scott, and it seemed that whoever emerged as the war’s biggest hero with an obligatory old nickname would be the next president.

After bombing the coastal city of Vera Cruz from the sea, Scott made an amphibious landing and moved west along the same route Hernán Cortés had used three centuries earlier in the Spanish Conquest (Chapter 3) while Taylor defeated Santa Anna’s forces in the north at the battle of Buena Vista. Scott won the race to the capital through mountains and jungles aided by a brilliant engineer and lieutenant, Robert E. Lee. After the climactic Battle of Chapultepec outside Mexico City, one of Santa Anna’s officers purportedly muttered, “God was a Yankee.” At the very least, the story dovetailed well with Americans’ sense of Manifest Destiny.

By the time U.S. troops got into Mexico City, with some soldiers jumping to their deaths rather than surrendering to U.S. troops, the government had crumbled and it was unclear whom to negotiate with. It also wasn’t clear who should do the negotiating for the U.S. either because Polk had already fired Nicholas Trist, the diplomat on task traveling with the army. It seems that Trist’s final act of insubordination was to delay his own firing with a 65-page counter-proposal. As a non-employee of the U.S. government, he wrote up the treaty to end the Mexican War, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed by people who didn’t really run Mexico (no one did). Under these circumstances, Congress didn’t have to sign a treaty allowing Mexico to retain the bottom 45% of their country. Then again, Congress doesn’t have to sign any treaty. This feature of the U.S. Constitution (Article II, Section 2) makes it confusing for other countries to end wars with the United States, especially problematic after World War I.

The U.S. fought hard for two years to conquer most of the bottom half of Mexico but now didn’t seem to want it. Americans debated on Capitol Hill and in newspapers and determined that Mexico had too many non-WASPs (white Anglo-Saxon Protestants) for their liking, though they didn’t use that acronym. Senator John C. Calhoun (D-SC) opposed incorporating anyone but Caucasians, while Senator John Clarke (W-RI) said, “There is a moral pestilence to such a people that is contagious — a leprosy that will destroy [us].” The “All of Mexico” movement also would’ve encountered fierce resistance from the Mexican population, who was already fighting a guerrilla war against American troops. The U.S. took the upper 55% and paid Mexico $15 million – half what Slidell offered Mexico earlier for the same thing. Many Americans were baffled as to why the U.S. would pay anything for territory they just conquered, but the settlement put a better spin on what was, essentially, a war of naked conquest. But adding insult to injury, Americans found gold in northern California just as the war was ending, worth far more than the Guadalupe settlement.

As with the War of 1812, the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-48 was sectionally divisive, with Northerners, especially Whigs, skeptical of the war’s aims. However, unlike the War of 1812, the Mexican conflict failed to unify Americans upon its conclusion. Ironically, the war caused more unity south of the border where, despite the loss, it forged a sense of Mexican nationalism. Even in the first year of the three-year war, U.S. politicians argued over how to divide the Mexican Cession (salmon color, above). Democrats had been unified north and south on supporting slavery, but now cracks began to show in their alliance. Northern Democrat David Wilmot (PA) introduced legislation in the House to ban slavery in the Mexican Cession, signaling that party’s ultimate fracturing along regional lines, even though his bill failed in the Senate. In the next chapter, we’ll see how the Democratic Party’s role in binding the country together ended at their 1860 convention when they split regionally, leading to the Civil War. The Whigs, especially those that would launch today’s Republican Party in the 1850s, were mainly a northern enterprise to begin with.

In some ways, Mexico benefitted from the war more than the U.S. despite losing. Similar to Canada during the War of 1812, the conflict forged Mexican identity in a way that the country’s initial independence from Spain hadn’t, partly because scorched earth tactics had victimized the civilian population. Meanwhile, Americans argued for the next fifteen years over whether or not to extend slavery into new western territories, precipitating the Civil War. Names later made famous by that war – U.S. Grant, George McClellan, Robert E. Lee, and others – met at West Point and fought together in Mexico, but ended up on opposite sides in the Civil War. As South Carolina Senator Calhoun presciently said at the time, “Mexico is our forbidden fruit.”

Optional Viewing, Reading & Listening:

Handbook of Tejano History (Emilio Zamora & Andrés Tijerina)

Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Commission

Max Flomen, “The Long War for Texas: Maroons, Renegades, Warriors, and Alternative Emancipations in the Southwest Borderlands, 1835-45,” JSTOR > Journal of the Civil War Era (2021)

Brenda Gunn, “Davy Crockett is Dead, But How He Died Lives On,” American Antiquarian Society (2006)

Joshua Zeitz, “The President Who Did It All In One Term – And What Biden Could Learn From Him,” Politico (2022)