Bully Pulpit ~ (n): “An office or position that provides its occupant with an outstanding opportunity to speak out on any issue”

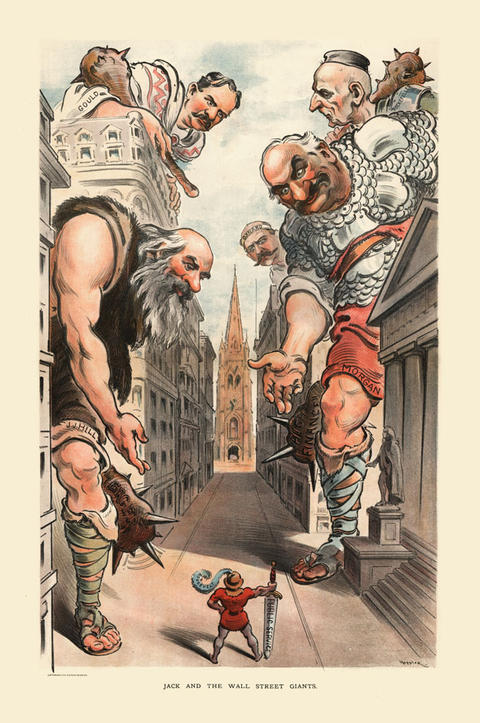

Here, we’ll pick up where we left off in Chapter 4 on the role of government in society, except that we’ll focus on the economy and unpack how the government’s economic role increased during the Progressive Era, both locally and nationally under presidents Theodore Roosevelt (R), William Howard Taft (R), and Woodrow Wilson (D). As we introduced in Chapter 2, commentators commonly visualize the degree of government’s role in the economy as a spectrum of greater role on the left and less on the right. Along the way, we’ll define ideologies and “isms” that people reference when debating politics. Toward the end of the chapter we’ll unpack the myriad and evolving meanings of liberalism and conservatism while diving deeper into the political-economic spectrum here in the opening section, with examples from Progressive-era economics sandwiched in between. Both conversations might leave you a little bleary-eyed but, if you can abide like “the Dude” in The Big Lebowski (1998), they will scaffold well into later chapters. As with any diagram, this one is a simplified abstraction and there are more elaborate two-dimensional political spectrum models, but it’s a basic starting point:

![]()

In modern America, we associate this left-right political spectrum with liberals on the left and conservatives on the right. The Left favors more government intervention on behalf of workers and consumers while the Right favors a freer, unregulated market. Liberals, for instance, brought about Social Security, 44-hr. workweeks, and the minimum wage in the 1930s, backing labor unions, whereas conservatives would prefer lower taxes and less regulation and don’t support labor unionizing for higher wages. You might remember that liberal and left both start with L, like the L.L. Bean retailer, and visualize Republican conservatives drinking RC Cola®. There are also some Roman Catholics (RC) that are conservative, or you could find a way to associate Republican conservatives with remote control or Red Cross. When people say near left or right, they mean nearer to the center; whereas, when they say far, they mean toward the edges. You’ll often see the French term laissez-faire (trans. “let it be”) to describe the right-wing, free-market approach.

In modern America, we associate this left-right political spectrum with liberals on the left and conservatives on the right. The Left favors more government intervention on behalf of workers and consumers while the Right favors a freer, unregulated market. Liberals, for instance, brought about Social Security, 44-hr. workweeks, and the minimum wage in the 1930s, backing labor unions, whereas conservatives would prefer lower taxes and less regulation and don’t support labor unionizing for higher wages. You might remember that liberal and left both start with L, like the L.L. Bean retailer, and visualize Republican conservatives drinking RC Cola®. There are also some Roman Catholics (RC) that are conservative, or you could find a way to associate Republican conservatives with remote control or Red Cross. When people say near left or right, they mean nearer to the center; whereas, when they say far, they mean toward the edges. You’ll often see the French term laissez-faire (trans. “let it be”) to describe the right-wing, free-market approach.

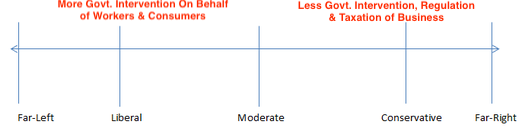

In modern politics left and right can signify one’s stand on a host of other issues — gender, church/state, guns, abortion, drugs, immigration, etc. Social, racial, and religious issues weave in and out of the political parties over history, but this economic spectrum has held steady for roughly a century, with the bow in the middle of the tug-of-war rope shifting gradually to the left and right — to the left with the Progressive Era and Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal of the 1930s and part way back to the right with Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Most presidents don’t have a lasting impact on “moving the needle.” What’s the difference between moderates and those on the edges? Unlike economic libertarians on the far right, most Republicans support moderate levels of socialism, like Social Security/Medicare, postal system, and K-12 public schools. Unlike communists on the far left, liberals and democratic socialists want most of the economy to stay in private hands (businesses/corporations, shops, farms, etc.), but also want the capitalist engine to redistribute wealth throughout society. Today, ~ 66% of economic activity in the U.S. is in the private sector. Politically, democratic socialists favor democracy whereas communists favor dictatorships.

As we saw in Chapter 2, socialism is a slippery term because it’s sometimes used interchangeably with communism, but can also mean any public sector of an otherwise capitalist economy like public schools, post office, police and fire departments, or safety nets like Social Security and Medicare/Medicaid. This confusion traps the sort of left-leaning Democrats that support, say, public health insurance, when journalists or citizens at a town hall meeting ask them — often with a raised eyebrow and air of a school principal interrogating a delinquent 5th grader — whether they are a “socialist.” Conservative spinners delight in leaving off the democratic qualifier of democratic socialism in hopes that their audience is inclined to equate the word with totalitarian communist dictatorships like the Soviet Union, Cuba, Venezuela, or North Korea rather than the democracies of Europe, Canada, Japan, and Australia that provide healthcare insurance or free college tuition. When journalist/historian John Steele Gordon said that democratic socialism is an oxymoron, he was really just underscoring that democratic communism is a contradiction in terms because, thus far, they’ve proven incompatible (no communist countries are or have been democracies). Moderate Democrats try the same trick on leftist Democrats, as in 1948 when Harry Truman called the Democrats’ progressive wing “a bunch of commies.” Yet Truman and conservatives have dictionaries on their side, be they Oxford or Webster’s, who define the term socialism narrowly just to include a centralized system whereby the government controls the means of production, more similar to communism. If you find yourself confused as to what socialism means, you’re not alone, as its meaning shifts. If you find yourself bewildered by all of these “isms” and “ologies” bear with me. It’s tedious but the confusion surrounding them is one reason why too many citizens disengage from politics. It should go without saying that you’re free to come down wherever you’d like along this political-economic spectrum; the goal is to understand what the spectrum means in the first place.

Here’s more detail on a spectrum otherwise consistent with the one above: The redistribution of wealth refers to funding public services and programs (education, roads/bridges, parks, mail, disaster relief, disease control, welfare, etc.) through taxes, toward which wealthier Americans pay a higher quantity if not a higher rate (more below). A quick look at the Google image page for “political spectrum” shows a bewildering array of one- and two-dimensional spectrums, with fascism (authoritarian ultra-nationalism) often seen on the far right, but economic libertarianism is a better fit for the far right on a political-economic spectrum, and libertarian shouldn’t be confused with liberal (more on both below), even if the two share the first five letters and sometimes overlap. To understand the left-right spectrum is to understand why right-wingers watching this 2023 video would consider what Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) is saying about Joe Biden (D) bad, while left-wingers would consider it good.

The redistribution of wealth refers to funding public services and programs (education, roads/bridges, parks, mail, disaster relief, disease control, welfare, etc.) through taxes, toward which wealthier Americans pay a higher quantity if not a higher rate (more below). A quick look at the Google image page for “political spectrum” shows a bewildering array of one- and two-dimensional spectrums, with fascism (authoritarian ultra-nationalism) often seen on the far right, but economic libertarianism is a better fit for the far right on a political-economic spectrum, and libertarian shouldn’t be confused with liberal (more on both below), even if the two share the first five letters and sometimes overlap. To understand the left-right spectrum is to understand why right-wingers watching this 2023 video would consider what Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) is saying about Joe Biden (D) bad, while left-wingers would consider it good.

We’ll get to Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) and Lyndon Johnson (LBJ) in later chapters but, for now, suffice it to say that Biden liked the video so much he put it to music and added: “The Biden Campaign Approves This Message.” It’s refreshing that they agree on the facts.

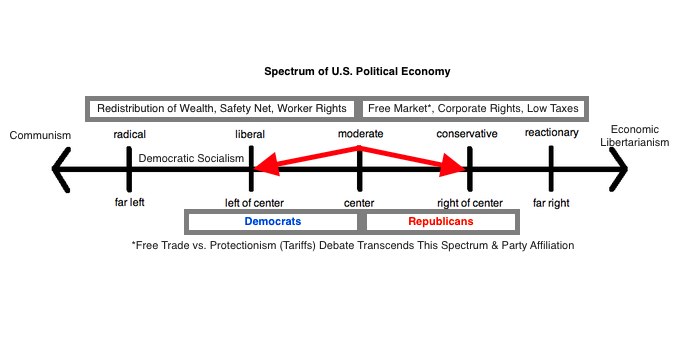

Democratic socialism basically entails a robust system of redistributing wealth via taxation on behalf of those less wealthy. A good example of wealth redistribution is your reduced tuition at Austin Community College. The laissez-faire/libertarian approach would be to keep the government out of education altogether: if you want a good job or the type of education and training that often qualifies you for one, then “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” by working hard and paying your own way at private schools. Maybe the elite private colleges can hand out a few scholarships here and there to the deserving poor so as to encourage a semblance of meritocracy and upward mobility. Liberals and moderate conservatives argue that, realistically, we’re not all born onto an even playing field and that one role of government should be to help aspiring people pull themselves up by their bootstraps with subsidized public education or training; otherwise, we’re basically living in a quasi-aristocracy, if not quite as stuffy or inflexible as England’s traditional version. It is society’s role, in their view, to offer that framework of opportunity and, if we don’t, that comes back to bite us anyway in the form of an untrained workforce, higher crime rates/incarceration, and poverty. In the U.S., we fund public education with taxes for K-12 and partially for public colleges like ACC, at which your “full tuition” is ~ 5x lower than it would be without public subsidies/taxes (see below). Whether you think that’s too generous or not generous enough indicates where you fall along this political-economic spectrum, at least for one issue. Left-wingers would argue that free community college tuition such as ACC’s Pilot Program will boost upward mobility, while right-wingers would argue that their property taxes are being wasted on students that mostly don’t finish their two-year degrees. Here is ACC’s revenue pie chart from a few years back: We’ve never had a market completely free of government interference, nor could we. Such an economy would be impossible in the modern age since there would be no infrastructure for businesses to get around on, protection of property rights, clean water or air, military protection, disease control or, so far at least, reliable currency. There would be no laws governing contracts, liability or bankruptcy. As economist Robert Reich paradoxically put it, “Without government, there can be no free market.” None of that stops politicians from making grandiose claims like history has shown that government can’t solve any problems or free markets solve all problems. History doesn’t back up either generalization about government or free markets and neither has it offered up any examples of communist countries that created strong government-planned economies by eliminating free markets altogether. Over the last two centuries, we’ve seen that capitalism spurs growth and innovation and has made most peoples’ lives more comfortable. And we’ve seen that free markets have flaws, including lopsided concentrations of wealth and poverty, monopolies, pollution, higher infant mortality, bad working conditions, and other externalities (economist jargon for drawbacks). Thomas Jefferson, the Founding Father most commonly enlisted in support of freedom and limited government, defined a “wise and frugal government” as one that should “restrain men from injuring one another” and “leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement” (1801 Inaugural Speech). That’s a balancing act because men sometimes injure each other in their own pursuits.

We’ve never had a market completely free of government interference, nor could we. Such an economy would be impossible in the modern age since there would be no infrastructure for businesses to get around on, protection of property rights, clean water or air, military protection, disease control or, so far at least, reliable currency. There would be no laws governing contracts, liability or bankruptcy. As economist Robert Reich paradoxically put it, “Without government, there can be no free market.” None of that stops politicians from making grandiose claims like history has shown that government can’t solve any problems or free markets solve all problems. History doesn’t back up either generalization about government or free markets and neither has it offered up any examples of communist countries that created strong government-planned economies by eliminating free markets altogether. Over the last two centuries, we’ve seen that capitalism spurs growth and innovation and has made most peoples’ lives more comfortable. And we’ve seen that free markets have flaws, including lopsided concentrations of wealth and poverty, monopolies, pollution, higher infant mortality, bad working conditions, and other externalities (economist jargon for drawbacks). Thomas Jefferson, the Founding Father most commonly enlisted in support of freedom and limited government, defined a “wise and frugal government” as one that should “restrain men from injuring one another” and “leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement” (1801 Inaugural Speech). That’s a balancing act because men sometimes injure each other in their own pursuits.

As the tension between Jefferson’s injuring and industry-pursuing unfolded during the Industrial Revolution, most countries arrived at some compromise we can roughly call regulated capitalism. The United States is one such country. Compromises generally please no one, and there are plenty of intelligent people that would favor more extreme options on either end of the spectrum: the left toward greater government control, or the right toward less. In the U.S., a favorite among the far right is novelist Ayn Rand (1905-1982), whose Objectivist philosophy advocated a libertarian, laissez-faire society unencumbered by altruism. After coming of age in Revolutionary Russia, Rand moved to the U.S. in 1925 and anticipated “greed makes good” long before Gordon Gekko in Wall Street (1987). In Rand’s vision of minimal statism, citizens can’t use physical force to get what they want and a skeletal government exists to protect property rights. Beyond that, though, society should run on its own. In a passage from her most famous book, Atlas Shrugged (1957), the atheist philosopher inverted the Biblical phrase (KJV 1 Timothy 6:10) about money being the root of all evil: “Until and unless you discover that money is the root of all good, you ask for your own destruction. When money ceases to be the tool by which men deal with one another, then men become the tools of men. Blood, whips, and guns–or dollars. Take your choice–there is no other–and time is running out.” Given her Russian background, Rand suspected all governments of being inclined toward totalitarianism. The protagonists of Atlas Shrugged are a cabal of industrialists who destroy the government and its parasitical socialist “looters” and “moochers” so that they can rebuild it along minimalist lines. The first line of their revised Constitution is: “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of production and trade.” Ayn Rand’s followers include Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Senator Rand Paul (R-KY), former House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI), Donald Trump (though he’s more transactional than ideological), and Trump/Brexit campaign donor and Breitbart investor Robert Mercer, along with former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan (1987-2006). Rand inspired influential GOP donors Charles and David Koch, who wanted to abolish Social Security, Medicare/Medicaid, and welfare and have wielded their influence to delay action on climate change.

In its purest form, libertarian anarcho-capitalism is tough to test with so few real-world examples — part of why its founding text is a novel. Rules are the bedrock of any civilization just as they’re the defining essence of sports. One attempt was the Republic of Minerva on a reef south of Fiji in the early 1970s — free of taxes, welfare, subsidies or any form of economic intervention — but it didn’t last long and is now underwater, perhaps ironically so. Another from the same era was the short-lived Abaco Independence Movement in the Bahamas. Paypal co-founder Peter Thiel funded Patri Friedman’s Seasteading, that supports libertarian sovereignties on offshore islands, rigs or reefs. Based on the example of the Sealand abandoned/occupied oil rig off England, the United Nations won’t recognize such squatter sovereignty. The Citadel in northern Idaho was based on libertarian principles, but its emphasis was more political than economic. There’s a small but growing trend in this direction and those interested should see Raymond Craib’s CounterPunch optional article below. In The Not So Wild, Wild West (2004, review), the Hoover Institution’s Terry Anderson and Peter Mill argue that low-government “free-market environmentalism” functioned in the Old West of their native Montana, though they don’t provide verifiable economic or crime statistics. While libertarian communities are scattered and scarce, we can say that Ayn Rand’s dichotomy between libertarianism and totalitarianism is false since none of the near 200 countries on Earth are libertarian and most aren’t totalitarian (false dilemma fallacy). For reasons that confound historians of Revolutionary America, those that favor the individual over the collective also indulge fantasies of the Founders creating a society in 1776 with few rules or obligations. They did not, but it’s true that some of them envisioned a minimal role for the national government in relation to strong state governments and less social safety net. Was Rand at least right that there are some moochers exploiting governments that do provide a safety net? Undoubtedly, mixed in with the deserving poor, a few able-bodied slackers collect welfare or unemployment insurance longer than they should, as portrayed by George in the Seinfeld (1989-98) sitcom.

A big dose of libertarianism is built into all democracies, as they naturally value individual rights more than dictatorships or monarchies do. There is a more moderate American Libertarian Party (1971- ) that is more fiscally conservative than Republicans and at least as culturally liberal as Democrats. Their basic goal is to minimize the government’s role in society as much as reasonably possible. Its platform includes a leaner federal government, isolationist foreign policy (military for defensive purposes only), looser regulations on guns, and ending all drug prohibition. In different ways, anti-authoritarian rebellious streaks thread their way through the mainstream Republican and Democratic parties and among independents. These garden-variety forms of social and political libertarianism, as opposed to purely economic, are widespread and defy placement on the simple left-right spectrum above (e.g., being pro-choice is a mainstream libertarian stance). There are modern strains of conservatism, including Porchers and Ron DeSantis, that invert libertarianism by arguing for maximizing government power on behalf of social causes rather than limiting it (e.g. outlawing woke politics or privileging Christianity and traditional nuclear families, etc.). And there are hybrid ideologies like libertarian socialism that favors de-centralized control. Like states’ rights (versus national power) ideology, it’s rare for someone to be genuinely committed to libertarianism across the board. Most of us just cherry-pick these concepts selectively on behalf of certain causes, but are ideologically inconsistent.

If COVID-19 could think, it would’ve appreciated the libertarian “freedom to infect” that undermined collective efforts to stop its spread and/or discouraged vaccinations for anything other than sound medical reasons. Refined, utilitarian libertarianism argues for freedom from government interference if one’s actions don’t harm others. Cruder versions equate all rules with “Nazism” or advocate the right to reckless behavior dangerous to others on behalf of personal liberty and freedom from government interference. As many rebellious teenagers have discovered, default resistance to authority can be problematic if the advice of one’s parents is actually smart. Racists infiltrated the Libertarian Party recently because they were angry that they’d siphoned GOP votes in the 2020 election but, historically, libertarianism is neutral on race, favoring neither government policies aimed against minorities nor policies to counter discrimination (the Hill).

On the far left end of the spectrum, there’s no need for fictional speculation. We have historical examples of communism going far in the big-government direction, with the Soviet Union and other dictatorships that drowned in their own bureaucracy and stifled peoples’ ambition as they seized the means of production (farms, factories, businesses) to share the profit among all the people equally. Innovation has been virtually non-existent because they don’t reward risk, and the lack of profit motive undermines work ethic except among those truly dedicated to the cause. On the upside, communist societies lower crime and poverty, eradicate unemployment, and provide comprehensive healthcare coverage, albeit for mediocre healthcare. But they’ve also killed and imprisoned dissidents and starved people to death through misguided and poorly implemented economic planning. Communism’s main apostle, Karl Marx (right), also underestimated the capacity of capitalist democracies to appease workers through incremental and moderate reforms, trade unions, government pensions (e.g. Social Security), redistribution of wealth via taxes, child labor restrictions, free public education, and opportunities for upward mobility. Pollution, a byproduct of industrialization regardless of the political system, has been just as bad if not worse in communist countries as capitalist.

Beyond economic problems, communists have been unable or unwilling to operate within a democratic political framework. In other words, bona fide communism is decidedly not democratic socialism of the sort practiced in Western Europe, Japan, Canada, and Australia, and promoted in the U.S. by liberal Democrats. Instead, it’s led by a vanguard of leaders, typified first historically by Vladimir Lenin (left), that don’t trust the political instincts of the masses that they’re advocating for. For the now not-so-new New Left, we still haven’t seen genuine Marxism because real-world examples have been warped by the totalitarianism of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Pol Pot, Kim Jong-un, etc. After all, in the Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx predicted the state’s eventual dissolution after workers seized the means of production, but that proved unrealistic. That’s such a thorough list of despots — including several outright sociopaths worse than anyone elected in democracies other than Hitler — that it seems pure communism leads inevitably toward totalitarianism. While technically it’s too soon to tell after a century+, dictatorships are likely intrinsic, or essential, to communism. We have small examples of communes like the Israeli Kibbutz that have worked well but, when it comes to the sort of idealized, non-totalitarian, state-level communism imagined by Marxists, there’s less track record than even the libertarian, oceanic outcroppings, which is to say, none.

Beyond economic problems, communists have been unable or unwilling to operate within a democratic political framework. In other words, bona fide communism is decidedly not democratic socialism of the sort practiced in Western Europe, Japan, Canada, and Australia, and promoted in the U.S. by liberal Democrats. Instead, it’s led by a vanguard of leaders, typified first historically by Vladimir Lenin (left), that don’t trust the political instincts of the masses that they’re advocating for. For the now not-so-new New Left, we still haven’t seen genuine Marxism because real-world examples have been warped by the totalitarianism of Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Pol Pot, Kim Jong-un, etc. After all, in the Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx predicted the state’s eventual dissolution after workers seized the means of production, but that proved unrealistic. That’s such a thorough list of despots — including several outright sociopaths worse than anyone elected in democracies other than Hitler — that it seems pure communism leads inevitably toward totalitarianism. While technically it’s too soon to tell after a century+, dictatorships are likely intrinsic, or essential, to communism. We have small examples of communes like the Israeli Kibbutz that have worked well but, when it comes to the sort of idealized, non-totalitarian, state-level communism imagined by Marxists, there’s less track record than even the libertarian, oceanic outcroppings, which is to say, none.

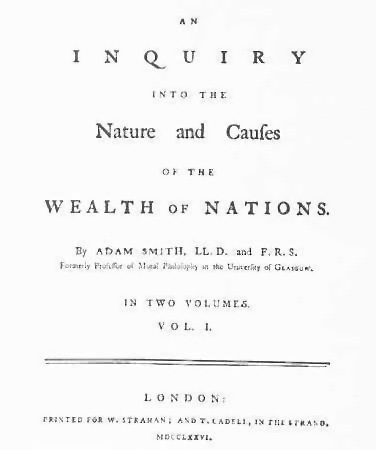

Marx in his purest form remains popular among young trustafarians and some academics — alone among dead white males, immune from cancelation or decolonization — but not politicians. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), for instance, is a democratic socialist but not a communist, which is fundamentally different. In America, the bearded sage of communism lives on mainly via microeconomic terminology and Academic Marxism, which doesn’t necessarily advocate a leftist political stance so much as a theoretical emphasis on economics and class-conflict as the driving force of history, or the best lens through which to understand society as opposed to politics, race, religion, war/diplomacy, gender, culture, etc. It’s impossible to imagine modern historiography, the study of history, without Marx because he applied theoretical frameworks that no one can ignore, regardless of political orientation. Before Marx, “history” was usually just a chronicle of top-down events concerning wars or dynastic changes, etc., not a thoroughgoing analysis of how society evolves as a whole. No one wrote history books from the “bottom up” discussing workers or regular people, or what power they might leverage collectively. And while most historians don’t reduce decision-makers’ motives or ideals merely to their economic interests or material circumstance, as would an absolute Marxist, they at least take those factors into account. Like historiography, economics traces to antiquity, but Enlightenment philosophers including Adam Smith (more below) pioneered the separate field of study and Marx expanded on that foundation, coining some terms used across the spectrum (Purdue).

However you may feel about pure left-wing and pure right-wing options — and thoughtful students should read widely with open minds — neither extreme is likely to play out in the U.S. anytime in the foreseeable future. Ayn Rand hasn’t gained mainstream traction and neither Rand Paul nor Paul Ryan suggested that we completely eliminate entitlements like Social Security-Medicare, though Ryan did say in 2009 that “we are now living in an Ayn Rand novel.” Donald Trump, often described as far right, has consistently pledged to never even reduce Social Security/Medicare benefits, let alone get rid of them, while claiming that all Democrats are communists.

In the meantime, the most practical way of approaching the role of government in the non-fictional, non-theoretical world is to debate the extent of government interference on an item-by-item basis, then argue it out in the public forum. Too many regulations can be counter-productive, and so can too few. Ayn Rand fan Alan Greenspan came around to the latter notion after the financial meltdown of 2008-09, lamenting the deregulation of Wall Street he’d helped bring about. Such centrism and moderation is boring, tedious, and frustrating and its advocates don’t enjoy the simple purity of Rand or Marx. True believers are in a perpetual state of disappointment that moderates aren’t being ambitious enough. Leftists, for instance, think near-left, moderate liberals are co-opted by the system and aren’t fighting hard enough against the Man; and right-wing commentators eviscerate moderate Republicans for selling out as Washington “insiders” or being part of the “swamp.” For Leftists like Noam Chomsky, America’s two-party system is a myth, with Republicans and Democrats really constituting one pro-business party and, sure enough, many corporations just bribe both equally with donations to cover their bases. Moderates answer that they’re doing what they can within real rather than theoretical constraints — the so-called “politics of the possible.” They can claim that the back-and-forth of compromise has produced the best real-world results we’ve seen so far.

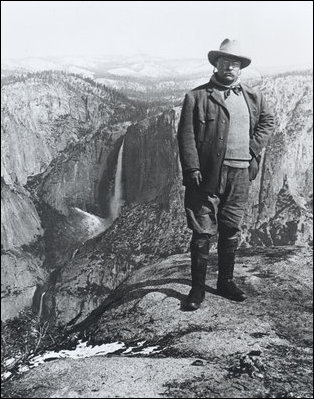

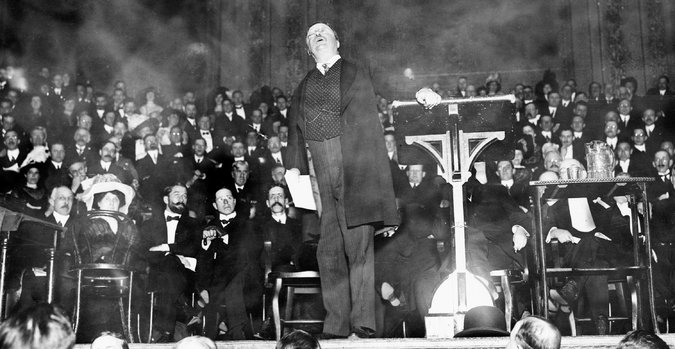

What was possible or impossible in America came into focus during the Progressive Era. In the last chapter, we saw Americans striking a balance between freedom and order on white voting, education, entertainment, food, drugs, and alcohol. Here, we’ve started with a head-spinning whirlwind tour of the political spectrum, but now we’ll home in on how the U.S. regulated capitalism in the middle regions of that spectrum during the Progressive Era. The central figure in the national government was combative and fiery president Teddy Roosevelt, whom one journalist described as a “steamboat in trousers.”

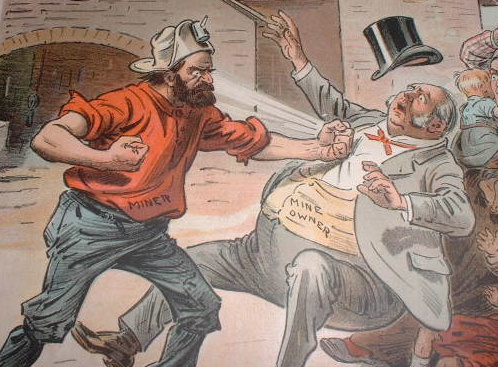

Though a writer and historian, “TR” didn’t worship the Founders and wasn’t hidebound by their original intention to create a smaller, weaker central government: “Our forefathers faced certain perils which we have outgrown. We now face other perils, the very existence of which it was impossible for them to foresee” (1905 Inaugural Speech). Founder Thomas Jefferson said as much himself in this 1816 letter, describing such “sanctimonious reverence” for the Constitution as “too sacred to be touched” as a man wearing a coat that fit as a boy. Though no fan of Jefferson, TR felt likewise and used his bully pulpit (public speeches, media, etc.) to take his case more directly to the American public than previous presidents. Modern politicians use a combination of X-Twitter®, press conferences, cable TV, and state-of-the-union addresses as their bully pulpits, just as Franklin Roosevelt used radio in the 1930s. Teddy Roosevelt used his speeches as a sounding board to broker what he called a square deal for everyone, both workers and management. He coined the phrase during the 1902 Coal Strike, the first strike in American history the government intervened in as a neutral arbitrator rather than on behalf of management. The Republican TR liked the ring of it and branded his overall economic policy the Square Deal, laying the foundation for his Democratic fifth-cousin Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s. In 1902, though, Franklin was a sophomore at conservative Harvard and criticized Teddy’s actions for interfering with the free market. Still, it was getting cold and the future president was grateful for the arrival of coal on campus for the stoves.

Roots of Economic Intervention

People often cite Franklin Roosevelt’s more famous and substantial 1930s New Deal as the fork in the road where America strayed off the free-market path toward a regulatory state, but that happened gradually and started earlier. We’ve already seen the government affecting trade through tariffs (import taxes), giving away land to favored recipients (railroads, farmers, universities), and influencing labor relations by intervening militarily on the side of management to break strikes.

The Constitution’s Commerce Clause (aka “Interstate Commerce Clause”) gives the national government the right to regulate commerce between but not within the states. This clause was an early legal axis around which those on the Left and Right argued not just about how much government intervention was preferable, but also allowable under the Constitution. Relying mainly on the Commerce Clause for constitutional justification, the government established legal authority over railroads, banks, pipelines and medicine between 1882-1906, long before Franklin Roosevelt arrived on the scene during the Great Depression of the 1930s. FDR’s New Deal of the 1930s built directly on the foundation of the Progressive Era. An early turning point was Swift & Co. v. United States (1905), involving Chicago meatpackers. That case, decided one year before the Pure Food & Drug Act, helped establish the Commerce Clause precedent and, along with lobbying and muckraking efforts mentioned in the previous chapter (Roosevelt, Sinclair, Heinz, etc.), led to the meat industry’s regulation. Swift & Co. v. U.S. also broke up a trust that wasn’t just one company monopolizing an industry but rather a series of companies colluding on pricing, agreeing to set a price basement. The same principle applied to railroads. Spurred by the Populists we studied in Chapter 2, the Interstate Commerce Commission under Teddy Roosevelt regulated railroad rates with the 1903 Elkins Act and 1906 Hepburn Act. This, too, was part of TR’s Square Deal whereby he didn’t redistribute wealth to the poor like his cousin Franklin later would, but he used intervention to prevent big companies from exploiting working Americans. In an unprecedented action for a president, TR rode the rails to campaign on behalf of railroad regulation the same way a politician would campaign for an election in a Whistle-Stop campaign.

The national government also outlawed alcohol and narcotics during the Progressive Era, both economic sectors in their own right. As the Industrial Revolution and immigration fueled rapid growth, these trends continued through the 1910s on national, state, and local levels. Below, we’ll cover national government intervention in the economy as it grew during the Progressive Era, including the Federal Reserve, Federal Income Tax, child labor laws, and trust-busting. These topics are dry but important. While our chapter title highlights Teddy Roosevelt as the movement’s figurehead, the Progressive Era includes William Taft and Woodrow Wilson’s presidencies and played out locally in states and cities.

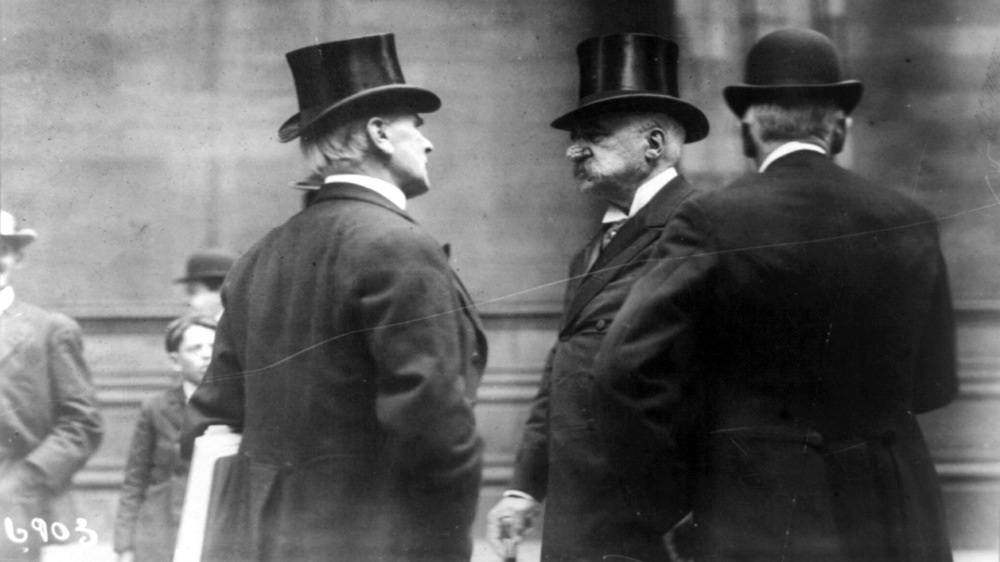

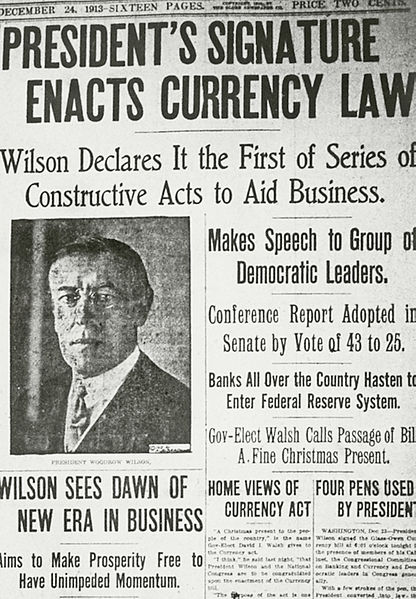

Federal Reserve

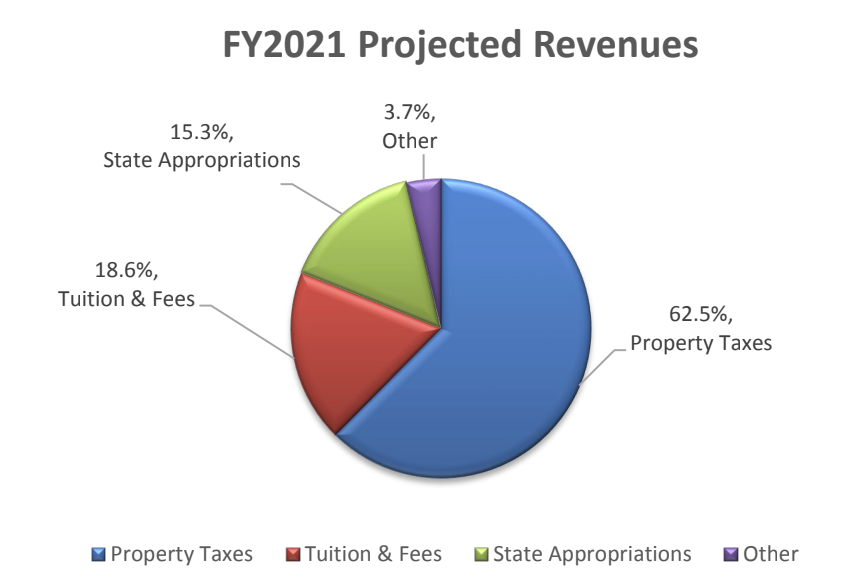

Congress created the Federal Reserve in 1913 in response to the Panic of 1907 to manage currency. In previous panics, only private “lender of last resort” J.P. Morgan (above, center) stabilized the government’s gold standard (1895) and saved the banks by lending them his own cash to offset their losses (1907). But private lenders of last resort couldn’t be counted on to always be there in the future. With “the Fed,” common shorthand for the Federal Reserve, the government would serve that purpose, pooling the resources of thousands of member banks. They added the dual mandate of maximizing employment rates and stabilizing prices in 1977, though the Fed has struggled more in those roles to have anything other than an indirect influence. The 1907 mini-meltdown also compelled the government to regulate the stock market for the first time. They created the Federal Trade Commission in 1914, a precursor to today’s SEC, or Securities & Exchange Commission.

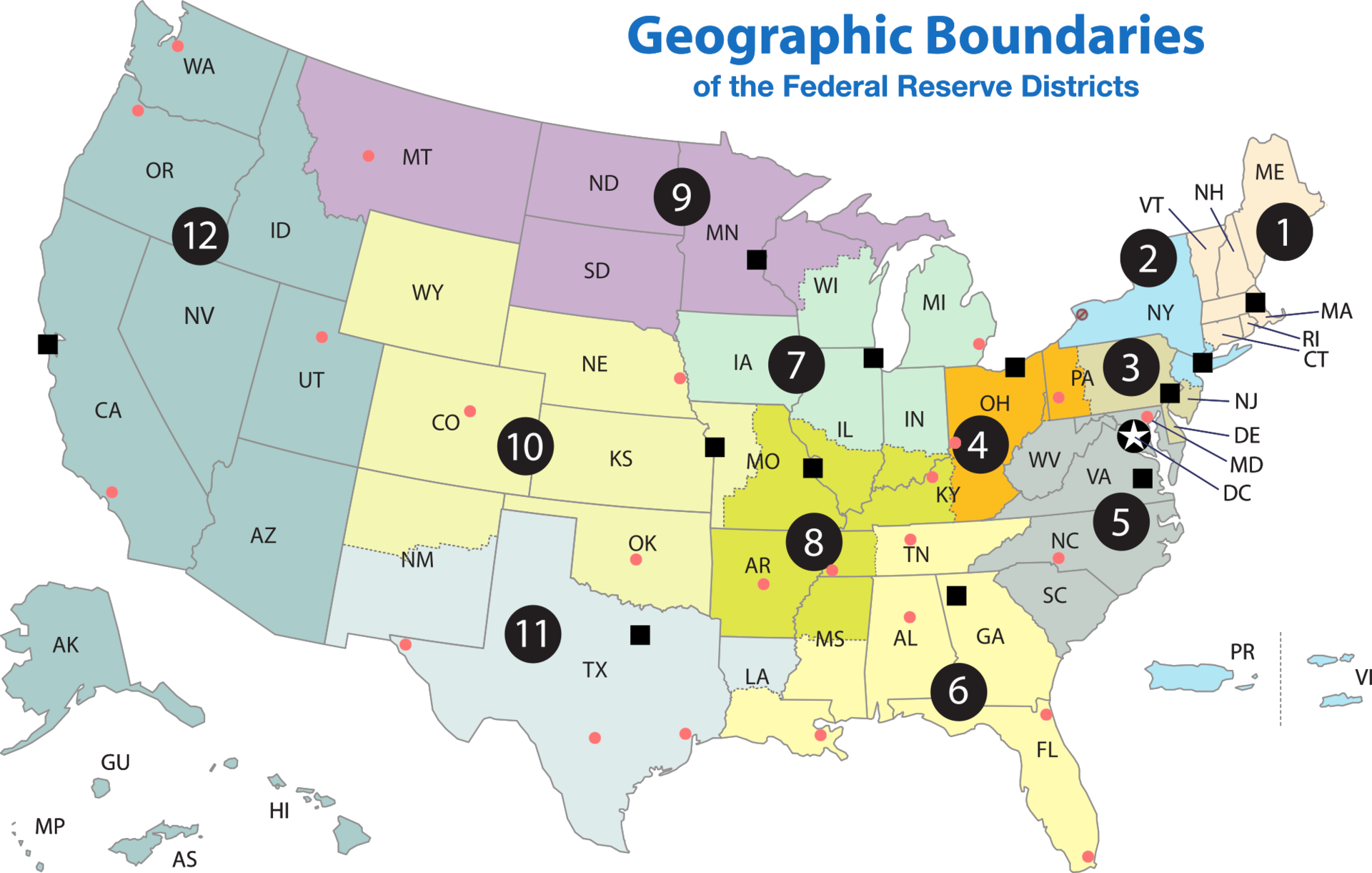

The Fed had moderate success in stabilizing the banking system, at least in comparison to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The in comparison is a key qualifier because there were serious problems in 1929-1933, the 1970s, and 2008-09, though the Fed came to the rescue in 2008-09 rather than causing the problem. Unlike the two earlier national banks (1791-1833), the Fed is a non-speculating (non-investing) bank set up to distribute money from the Treasury Department’s Mint (coins) and Engraving Office (bills) to regular banks through twelve regional reserves that maintain some private control. The Dallas branch (#11 below), for instance, serves Austin. Regionalizing the branches keeps cash from concentrating in certain regions.

You could think of the Fed as where “banks bank,” serving as what most countries call their central bank. The U.S. hadn’t had a central bank since Andrew Jackson vetoed re-chartering the Second Bank of the U.S. in 1833, which is why progressive government reformers meeting on Georgia’s Jekyll Island had to fend off the “ghost of Jackson.” Though Alexander Hamilton was a U.S. founder, he was more revered in Canada, where they followed his centralized, regulated banking model. But the post-Jackson U.S. had more decentralized, local and statewide unit banks, despite the government nationalizing “greenback” currency after the Civil War. With the revamped Federal Reserve, banks swap federal IOU’s (U.S. treasuries/bonds), municipal bonds, and mortgage-backed securities back and forth with the Fed in exchange for reserve cash through Open Market Operations — swap here meaning that they buy or sell these assets. After the Great Recession of 2008, the Fed purchased treasuries to infuse cash into the banking system, worrying critics that by loading too much cash into the economy they’d set the stage for future inflation. Banks also borrow and lend to each other through the Fed-influenced “repo market.” Each member bank has to keep ~ 10% of their customers’ money “on reserve,” depending on size, to stabilize the system, thus its name.

The Fed works with the Secret Service to check for counterfeit bills and replaces torn and tattered bills (helpful, too, because cash is unsanitary). The Chicago branch alone destroys ~ $23 million in old bills per day, along with 50 counterfeits, though those numbers will likely drop as we move toward a more cash-less society. With $70-80 billion on-site at any given time, the Fed branches are high-security with nobody working alone and cameras everywhere. Federal Reserve member banks also fall under FBI jurisdiction when robbed.

Created by Congress, the semi-independent Federal Reserve distributes cash from the U.S. Treasury and funnels profit back into the Treasury rather than to shareholders. The Fed doesn’t exist to earn a profit, but rather to stabilize the economy by furnishing an elastic currency. Unlike Hamilton’s earlier national bank(s), the Fed doesn’t compete with local banks for retail business. After its role expanded during the New Deal with the 1935 Banking Act , the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) has contracted and expanded the economy by influencing the short-term Target Federal Funds Rate: the interest rate on overnight loans that member banks with surplus cash loan to those just under the 10% reserve limit — influenced in turn by the Fed’s buying and selling of bonds and tweaking the reserve requirement, which in turn influences the interest rate the Treasury pays for bonds (U.S. Treasuries). Elastic currency is complicated, but understand the main concept depicted in the diagram on the right. The more bonds the Fed buys, the more cash in the banking system; the more cash in the system the lower the interest rates and vice-versa. It’s a target because the Fed is manipulating the rates consumers pay for business loans, homes, cars, tuition, etc. indirectly by setting the rates it charges banks. The Fed sets the discount rate they charge at their Discount Window for short-term overnight loans to banks. This is usually what the media is referencing when they say the Fed is raising or lowering interest rates. These benchmark rates, in turn, impact the prime interest rate (aka “prime”) that banks charge their favored customers. The Prime Rate is generally ~ 3% higher than the Discount Rate and the lowest rate at which customers (non-banks) can borrow from commercial banks. The Wall Street Journal prime interest rate rose from 3.25% to 7.5% in 2022, but that’s a rough average and not the exact rate any one person necessarily gets on any one loan. Open Market Operations and the Discount Window are Tools that enable the Fed to set monetary policy by moderating interest rates and controlling inflation (prices). Inflation, when prices rise, happens when too much money is chasing too few goods. History teaches us that inflation can destabilize society, as demonstrated in Weimar Germany in the 1920s and during the Age of Exploration, with its infusion of silver from the Americas into Europe. Higher rates also strengthen the U.S. dollar internationally, which is good for travelers and importers but bad for exporters.

Created by Congress, the semi-independent Federal Reserve distributes cash from the U.S. Treasury and funnels profit back into the Treasury rather than to shareholders. The Fed doesn’t exist to earn a profit, but rather to stabilize the economy by furnishing an elastic currency. Unlike Hamilton’s earlier national bank(s), the Fed doesn’t compete with local banks for retail business. After its role expanded during the New Deal with the 1935 Banking Act , the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) has contracted and expanded the economy by influencing the short-term Target Federal Funds Rate: the interest rate on overnight loans that member banks with surplus cash loan to those just under the 10% reserve limit — influenced in turn by the Fed’s buying and selling of bonds and tweaking the reserve requirement, which in turn influences the interest rate the Treasury pays for bonds (U.S. Treasuries). Elastic currency is complicated, but understand the main concept depicted in the diagram on the right. The more bonds the Fed buys, the more cash in the banking system; the more cash in the system the lower the interest rates and vice-versa. It’s a target because the Fed is manipulating the rates consumers pay for business loans, homes, cars, tuition, etc. indirectly by setting the rates it charges banks. The Fed sets the discount rate they charge at their Discount Window for short-term overnight loans to banks. This is usually what the media is referencing when they say the Fed is raising or lowering interest rates. These benchmark rates, in turn, impact the prime interest rate (aka “prime”) that banks charge their favored customers. The Prime Rate is generally ~ 3% higher than the Discount Rate and the lowest rate at which customers (non-banks) can borrow from commercial banks. The Wall Street Journal prime interest rate rose from 3.25% to 7.5% in 2022, but that’s a rough average and not the exact rate any one person necessarily gets on any one loan. Open Market Operations and the Discount Window are Tools that enable the Fed to set monetary policy by moderating interest rates and controlling inflation (prices). Inflation, when prices rise, happens when too much money is chasing too few goods. History teaches us that inflation can destabilize society, as demonstrated in Weimar Germany in the 1920s and during the Age of Exploration, with its infusion of silver from the Americas into Europe. Higher rates also strengthen the U.S. dollar internationally, which is good for travelers and importers but bad for exporters.

The Fed’s manipulation of interest rates to smooth out boom and bust cycles is at the core of national macroeconomic monetary policy. Longtime Fed Chair William McChesney Martin (1951-1970) said the Fed’s role was to “take away the [spiked] punch bowl just as the party gets going.” In other words, once they’ve reignited the economy with “easy money” low-interest rates (more cash), they want to rein it in with higher rates (less cash) to avoid triggering high inflation. The less money in the system, the more interest a bank is likely to charge customers for a loan, due to the basic law of supply and demand. Customers’ rates are also impacted by their own credit ratings (their history of paying bills on time). Since the 1960s, Americans have the right to view their credit ratings. Borrowing money costs money, and how much has more impact on our lives than you might think, which is also why racially-mandated subprime rates caused systemic racism in the 20th century.

After 2008, the Fed under Chair Ben Bernanke kept rates low (0.00-0.25%), hoping that would fuel more borrowing and economic growth in the wake of the Great Recession, but also making it difficult for savers to earn interest on their money. They knew that such low rates would herd investors into investing in stocks instead of safer alternatives like bonds or bank savings accounts/CDs (certificate of deposit). The Fed pumped $85 billion a month into the banking system by buying up mortgages and long-term treasuries to keep yields low in a program called Quantitative Easing, or QE, and the economy slowly but surely mended. The Fed controls liquidity in credit markets, tightening or loosening lending rates, but can also undertake more unorthodox buying programs like QE to shore up banking and the stock market, or to encourage mild inflation (< 3%). When people said “money was free” during QE, they didn’t mean that the government was giving it away, but rather that the rates were so low that borrowing was free, meaning that those with the wherewithal larded up and used that money to invest or grow their companies.

Has the Federal Reserve done its job? It went to work quickly after it was set up in 1913-14, helping to stabilize the U.S. economy during World War I by shoring up the system. But the U.S. went off the Gold Standard during WWI, and the Fed struggled to balance the economy over the next twenty years as monetary policy seesawed, sometimes leaving the gold standard and other times increasing or decreasing the amount used to peg the dollar to gold. They reverted to the gold standard and stuck with it at the worst time, prior to the Stock Market Crash of 1929, decreasing the cash in circulation just as banks were running out, contracting the money supply. Then they doubled the reserve requirement (cash kept safe, out of investments) at an inopportune time in 1937, contributing to a recession within a recovery during the Great Depression.

The Fed also failed to raise interest rates in the late 1960s because they and President Lyndon Johnson didn’t want to weaken the economy, but inflation rose steadily and finally President Richard Nixon had to sever the dollar from the gold standard altogether in 1971. While the Fed is, in theory, independent from the executive branch, both Johnson and Nixon pressured the Fed to keep interest rates low to help the economy, and any president is well-served in the short-term by this “sugar high” of an economic boost, so their opinions are predictable. However, if employment is solid, low interest rates tend to boost borrowing and spending too much and cause inflation, and that very thing happened because of Johnson and Nixon’s influence, with the government itself borrowing to fund the Vietnam War and social programs. Inflation worsened throughout the 1970s with rising oil prices until Fed Chair Paul Volcker dramatically raised rates, deliberately causing a recession in the early 1980s to halt inflation. Then after a market crash in 2000 and 9/11 (2001), Alan Greenspan’s Fed kept rates low and pumped cash into the system between 2001 and ’05 even after the economy improved, helping to fuel a housing bubble — in that case, abandoning its mission to stabilize fluctuations in the economy.

History will judge the Fed’s massive infusion of cash into the system between 2008-2014, after that real estate bubble burst, and a second round during COVID-19. In late 2015, Chair Janet Yellen signaled that the Fed would reverse course. Their goal from 2015-19 was to slowly “take the punch bowl out of the party” by reversing quantitative easing, swapping treasuries back to banks for cash in an attempt to defuse inflation. In the meantime, the Fed held so many assets (including bonds, real estate mortgages, etc.), that the government (Treasury) made a lot of money from interest, which is good for citizens. In 2019-20, under Chair Jerome Powell, the Fed started gingerly lowering rates again, infusing the economy with cash. Meanwhile, President Trump — like most presidents more concerned with short-term growth than long-term inflation — pressured the Fed to lower rates faster yet, calling them “clueless, pathetic, boneheads.” COVID accelerated the loose monetary trend, with the Fed serving as the primary backstop to the economy and providing loans to businesses along with cash to banks, while Congress and the Treasury sent aid to citizens. But, in 2020, the Fed had less slack in the rope for looser monetary policy because they’d already been lowering rates when the economy was strong.

By flooding the system with easy money in the early 21st century, the Federal Reserve created the Everything Bubble that encouraged investing in real estate, stocks, private equity, and cryptocurrency. If you haven’t “cut the cord,” view any random business show on weekday cable and they’re more likely to be fretting about Fed rates than the actual earnings of the companies whose stock viewers are investing in. A common maxim is “don’t fight the Fed,” which is to say that you ignore at your peril the notion that the entire economy now revolves around the central bank’s axis. At this point, it’s safe to say that the Fed has added a third, unwritten mandate, which is to protect the stock market, but that could potentially conflict with the mandate to curb inflation. At the Everything Bubble’s peak, over half of the homes in Austin were bought by investors. If rates are low, it makes sense to borrow and invest and flip houses as much as possible, especially in growing areas. Just ask the Property Brothers.

Joe Biden was one of those unfortunate presidents in office when the Fed pulled away the punch bowl (raised rates) and the party guests weren’t happy, but they had no choice because, for the first time since the 1970s, they were fighting substantive inflation. Post-COVID inflation resulted mainly from shortages connected to disruptions in supply-chains (especially globally), tight oil supplies because of the [post-Ukraine invasion] Russian boycott and refineries that weren’t operating at full pre-COVID capacity, food and fertilizer shortages caused by the Ukrainian invasion, China tariffs initiated by Donald Trump and continued by Biden, and worker shortages (which raised wages, leading to a price/wage spiral) — all combining in a perfect storm to make demand exceed supply. When considering financial matters, always consider supply and demand. Fixing all those problems isn’t in the Fed’s wheelhouse because they really just control how much cash is in the economy, not how well supplied that economy is or how many willing workers it has. But, over the course of 2022-23, Powell’s Fed did their part, slowly but surely raising rates just enough to tame inflation but not enough to trigger a recession. So far, knock on wood, they seem to have pulled off just such a “soft landing,” though we’re not out of the woods yet. Powell signaled that they’d lower rates slowly in 2025 out of caution, for the same reason someone “drives slowly in the fog or walks slowly into a dark room full of furniture.”

There is no good evidence, in case you’ve heard rumors to the contrary, that the Fed is a conspiring cabal. It’s transparent relative to other agencies, and we might even take heart that this apparatus that controls our economic lives is boring and can really only move in two directions, limiting bad decision-making. Technocracy is much-maligned but, in this case, makes sense if the host exercises good judgment with the punch bowl. Yet, no one a century ago envisioned the Fed being more powerful economically than Congress and the presidency, let alone commerce itself.

Federal Income Tax

Federal Income Tax

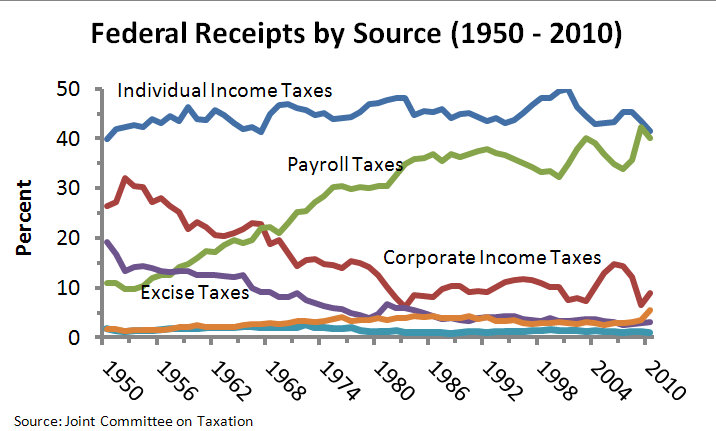

On to another boring but important topic. Benjamin Franklin once said that “in this world, nothing is certain except for death and taxes.” Yet, the U.S. had no federal income tax prior to 1913, except for briefly during the Civil War. Despite the Constitution’s Article I, Section 8 (aka the Taxing & Spending Clause), the Supreme Court declared an 1894 national tax unconstitutional in Pollock v. Farmer’s Loan & Trust Co. (1896). The Revenue Act and 1913 Sixteenth Amendment overturned that precedent, allowing the government to raise revenue in an era when it could no longer simply sell off western lands and depend on tariffs and bond sales. The revenue allows the government to conduct its basic functions, including maintaining a military, building infrastructure, and providing entitlements that include health insurance and a modest monthly pension for the elderly. Workers contribute to the latter via payroll deductions in their paychecks (itemized under FICA). Populists originated the national tax idea. The first 1913 bracket graduated or progressed upwards from just 1% for the poor to 7% for the wealthy, and the national government continued to rely mainly on excise or (regressive) sales taxes from 1913 to 1935. But, potentially, these graduated brackets were a variation, for income, on what Jefferson advised for property taxes when he wrote James Madison that “Another means of silently lessening the inequality of property is to exempt all from taxation below a certain point, and to tax the higher portions of property in geometrical progression as they rise.” (TJ to JM, 10.28.1785) The Founders didn’t restrict the national government from taxing in Madison’s Bill of Rights, even though there was more noise about such a potential Constitutional amendment in the 1790s than there was about guns, religious freedom, or legal rights.

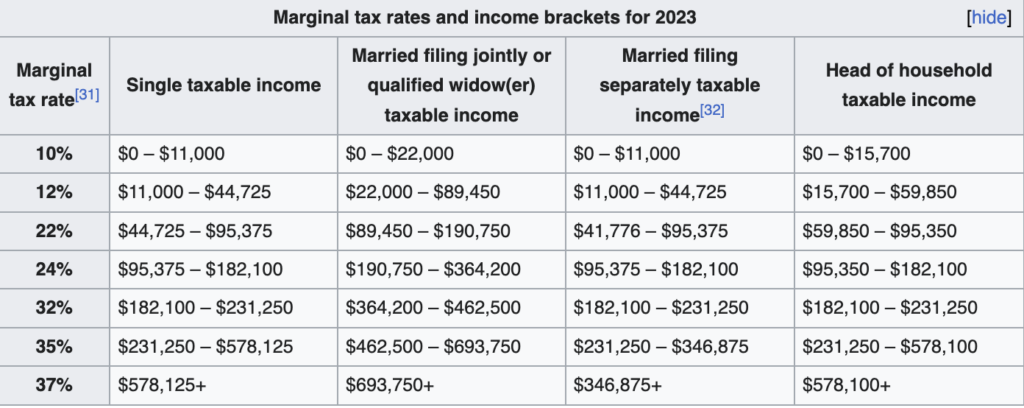

Today’s graduated brackets apply to everyone from lower middle-classes on up, with the rate of payments increasing as one moves up the scale, topping out at 37% for the upper bracket as of 2018 (here are the inflation-adjusted historic and 2015 rates). With recent legislation, the lowest bracket (earning $11k-$44) dropped from 15% to 12%. Contrary to popular belief, workers can’t barely increase their salary over a cut-off line and end up losing money. People only pay the higher rate on that extra portion of income in the higher bracket. No married couple, for instance, pays 37% on their entire income; only 37% on income beyond $693k. Everyone pays the same amount on the income earned within each bracket. Here’s a recent table: The rates vary depending on whether someone is filing jointly, or single, etc. Everyone that works outside a pension system pays a 6.2% Social Security payroll tax that contributes toward their own retirement. Sales taxes or local taxes on food are regressive since the poor use a greater portion of their money for essentials. Lottery tickets basically funnel money from workers into government coffers, but much of it cycles back to programs like education that help poor and middle classes.

The rates vary depending on whether someone is filing jointly, or single, etc. Everyone that works outside a pension system pays a 6.2% Social Security payroll tax that contributes toward their own retirement. Sales taxes or local taxes on food are regressive since the poor use a greater portion of their money for essentials. Lottery tickets basically funnel money from workers into government coffers, but much of it cycles back to programs like education that help poor and middle classes.

For most of the 20th century, the top rates were high, usually above 50%, but they dropped dramatically in the 1980s. While today’s income taxes are graduated, the tax on investments — dividends and capital gains — is only 15-20% for stocks held over three years. Since the wealthy derive most of their income from investing rather than income, their overall effective rates can be lower than people in middle classes paying 24-35%, though their totals are higher. Some are quick to complain of “class warfare” among anyone who doesn’t like this arrangement, but this regressive tax code even has some wealthy critics. Warren Buffet suggested a 30% overall bottom rate for the wealthy as defined by the top 0.3% (aka the Buffet Rule) and iconic conservatives Andrew Mellon (Treasury Secretary, 1921-32) and Ronald Reagan (President, 1981-89) favored taxing capital (investments) and labor (work) at the same rate. Buffet pointed out that, as a multi-billionaire, it was ridiculous that he paid a lower effective rate than his secretary. Currently, though, the bottom 99.7% is either fine with paying more, too fatalistic or apathetic to protest, thinks the lower capital gain rates spur the economy (“trickle-down”) or, most likely, doesn’t know exactly what’s going on.

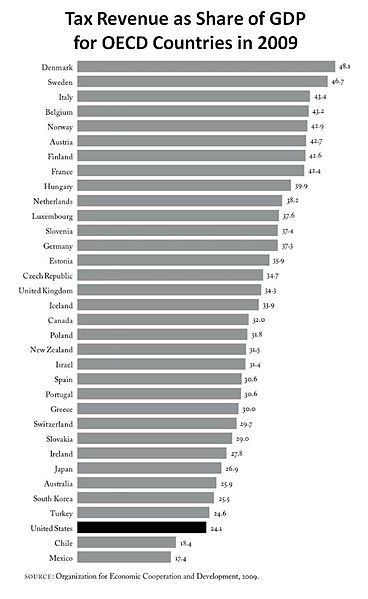

For all taxpayers, there are numerous write-offs for homeownership, home improvement, charitable donations, work-related travel expenses, etc. that lower one’s reported income. Total deductions of $900 billion in 2013 would’ve paid for almost all of the combined cost of Medicare and Medicaid. While America has made strides in lessening racial and sexual discrimination, home-owning voters of both parties continue to support rigging the tax codes against renters. The Home Mortgage Interest Deduction goes back to the beginning in 1913, to encourage homeownership, and the Charitable Contribution Deduction started in 1917. Overall, Americans today pay slightly lower rates than they did for most of the 20th century, but not significantly lower if one includes local taxes (state, county, sales, etc.).

American corporate rates dropped from 35% to 21% in 2018, but few pay the full rate. Some route their profits through Bermuda, Puerto Rico, Ireland (e.g. Apple), or other “tax havens” (low-tax jurisdictions). One downside of economic globalization for revenue-seeking governments is this legal tax dodge, creating a “race to the bottom” because, no matter how low corporate rates go, there’s always some other country willing to provide a haven by charging even less. Domestically, states like Texas poach companies from liberal states like California, enticing them with lower taxes (e.g. Tesla, Inc.). The same holds for individuals. Liberal and conservative elites might disagree on some things, but they bond over this important detail as they party in the Caribbean.

Due to the corporate tax code’s complexity and the corruption of lobbying, rates are distributed unevenly from company to company, usually favoring bigger companies with more political pull. Some corporations pay the full amount while others are, in effect, on welfare insofar as their rebates are more than their bills. The big Wall Street banks avoid taxes with offshore havens. Goldman Sachs, with direct influence in the cabinets of Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump, paid less than 1%. The overall American corporate tax average as of 2012 was 17.3% — just half the supposed 35%. It remains to be seen whether the new drop from 35 to 21% will be accompanied by stricter enforcement and closed loopholes, but don’t hold your breath.

According to Treasury Department estimates, if the U.S. got rid of all cheating, loopholes, and tax havens, the country could cut everyone’s taxes by 12% across the board and still balance the budget. We lose ~ $.5 trillion annually in lost revenue just to cheating (CRFB), meaning that, in some years (not recently), we could balance the budget by fully collecting revenue due. Yet, angry, suspicious, or duped non-cheating voters have instead irrationally cut funding to the Internal Revenue Service, easily the most cost-effective agency in all of government. The IRS can be heavy-handed, but it returns at least $2 for every $1 spent and even more when they go after cheaters. When the GOP took control of the House in January 2023, their first action was trying to repeal the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 provision that cracks down on wealthy and corporate “non-compliers,” but the workers that voted them into office don’t cheat. Trump-appointed IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig clarified that there would be no stepped-up enforcement for non-compliers making less than $400k under the IRA, but Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) warned FOX viewers that the IRS would descend on families and small businesses “like a swarm of locusts.” We should argue in good faith about what to spend on and who pays how much, but the only way to offset the revenue lost to tax dodgers is for the rest of us to pay more as the debt mounts. In both the 2023 and 2024 debt ceiling negotiations, Republicans negotiated to remove the stepped-up enforcement on wealthy cheaters (MarketWatch).

But a lot of lost revenue is rather from American corporations defraying taxes by keeping their overseas profits abroad in these tax havens rather than bringing it home. According to Bloomberg BusinessWeek, as of 2015 the top ten such tax dodgers alone — Microsoft, Apple, Oracle, Citigroup, Amgen, Qualcomm, JPMorgan Chase, Gilead Sciences, Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America — could’ve funded NASA, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Pentagon’s training of and equipping of security forces in Afghanistan, the Transportation and Security Administration, Social Security overhead, and the Departments of Justice, Commerce, Agriculture, Treasury, and Interior. In 2018, Amazon cleared $11.2 billion in profit and paid zero in corporate taxes, in their case because of reinvesting profit in infrastructure. Joe Biden and the U.S. Treasury helped broker the Global Minimum Corporate Tax Rate (GMCTR) of 15% with 135 other countries that would eliminate havens, set to start in 2023, but Congress backed out of the arrangement in 2022. The Inflation Reduction Act set the domestic corporate tax basement, after loopholes, at 15% (some companies will still pay 21%).

The 16th Amendment is an important watershed in American history. Since federal tax codes are graduated, it set up a mechanism for the government to redistribute wealth. As mentioned, for individuals that’s partially offset by capital investments being taxed at a lower rate than income but, even so, rich Americans pay far higher totals than poor. There are two ways to spin these statistics. The wealthy can complain that they pay a large proportion of revenues, while the rest can counter that the reason the wealthy pay so much in taxes is that they have such a high portion of the country’s money to begin with. The upper 1% have more money than the bottom 50% in America. For liberals, redistribution makes society more equitable and “evens the playing field” some. For conservatives, redistribution is unjust because graduated tax rates put the government in a permanent state of rewarding failure and punishing success, weakening everyone. While there are various rewards and punishments built into the tax codes (e.g., sin taxes on cigarettes and alcohol), most taxes aren’t punitive. They’re just being collected to fund the government, not encourage or discourage behavior. Taxes will remain at the heart of Republican-Democratic debates into the foreseeable future, regardless of what other issues come and go onto their platforms and who spins their party as “populist.” One thing voters in both parties agree on — other than accountants, who profit from the complexity of tax codes — is that they’d prefer to simplify the system by getting rid of all the complicated write-offs and loopholes…other than all the ones they like and profit from.

Government & Labor

Labor, meanwhile, focused on safety and hours more than wages in the Progressive Era. It wasn’t uncommon for blue-collar workers to put in 72 hours a week (6 days x 12 hours). One in eleven steelworkers died annually. Think about that. Would you work in a job where there was a 1/11 chance of dying in a given year? Those odds are worse than for soldiers or sailors in most wars or the most dangerous occupations today: lumberjack, fisherman, roofer, steelworker, pilot, and driver (taxi, truck, etc.). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the chance of a logger or fisherman dying in a given year is just over one in a thousand — a hundred times safer than a steelworker a century ago.

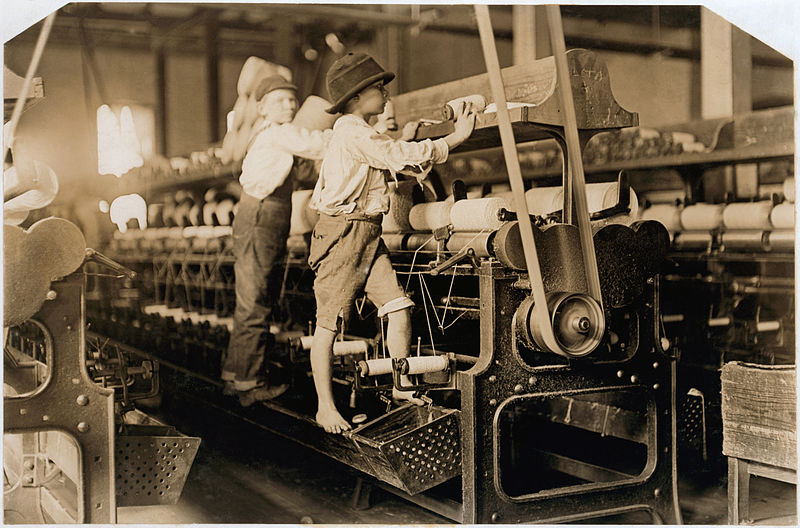

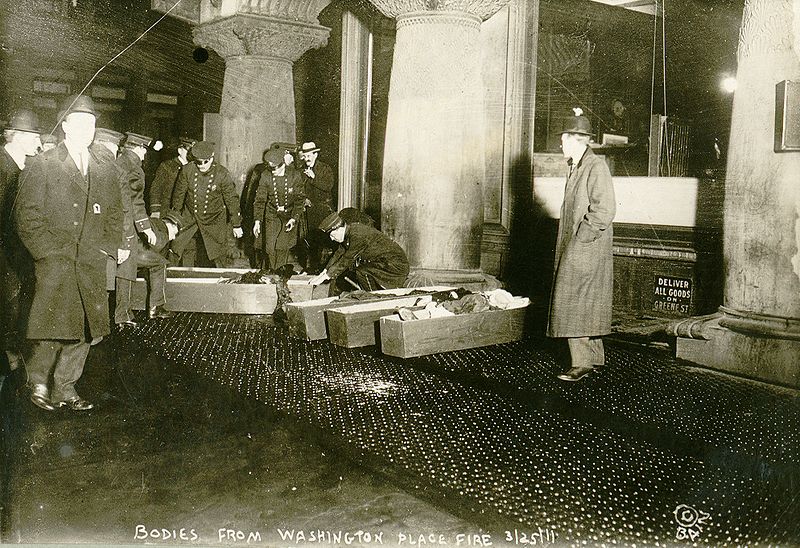

At the Triangle Shirtwaist factory in New York’s Garment District, 146 girls and women died in 1911, unable to escape a fire because their bosses nailed the exit shut to keep out union organizers or prevent workers from sneaking a break. When some made it out onto the fire escape, it collapsed under their weight. Others jumped to their death from the 11th-floor windows.

The fire led directly to building codes mandating multiple marked exits and outward-opening doors since many asphyxiated victims unable to get out an exit were trampled behind an inward-opening interior door. Happening in the middle of the day, just blocks from the New York Times office, the Triangle fire drew the public’s attention to child labor and union-busting, along with the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado in 1913 that we read about in the Gilded Age chapter.

The fire led directly to building codes mandating multiple marked exits and outward-opening doors since many asphyxiated victims unable to get out an exit were trampled behind an inward-opening interior door. Happening in the middle of the day, just blocks from the New York Times office, the Triangle fire drew the public’s attention to child labor and union-busting, along with the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado in 1913 that we read about in the Gilded Age chapter.

Unions gained some strength, but still lacked the right to collective bargaining, so management could simply fire or abuse strikers or union organizers. The Triangle Fire underscored these problems. The fight for worker safety and shorter work-weeks is a good example of how America’s three branches of government — congressional, executive and judicial — can check each other’s interests, with each never able to override the other two. Congress and the presidency, the two branches most closely connected to the people, favored regulating the workplace while the judiciary, led by the Supreme Court, saw such regulations as unconstitutional.

The Keating-Owens Act of 1916 set the age limit for miners at 16 and factory workers at 14 but, arguing that the Commerce Clause didn’t apply to production, the Supreme Court reversed the law in Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), a case where the plaintiff wasn’t management but rather a North Carolina family that needed their child to work. The Court wasn’t even friendly to state laws regulating worker hours unless they applied to women. In Lochner v. New York (1905), the Court shot down a state rule limiting the number of consecutive hours bakers could work without a break to 10 (several had collapsed from exhaustion and fallen into ovens). But the Court authorized a similar state law in Oregon that applied to female hotel workers. Courts and Congress locked horns on monopolies, or trusts, as well. During the New Deal in 1938, Congress and FDR outlawed child labor again and, that time, SCOTUS backed it unanimously in U.S. v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941). Dovetailing with Progressive-era states mandating education through age 16, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act outlawed non-farming work younger than 14, full-time work under 16, and hazardous work under 18 years of age.

Busting Trusts

Busting Trusts

In 1904, Lizzie Magie patented the Landlord’s Game. Dice-rolling players circled the square board buying up properties, railroads, and utilities and paying and collecting rent, all the while hoping to avoid “going to jail.” During the Gilded Age, Magie was a progressive reformer who, as political performance art, once advertised herself for sale in Chicago newspapers to draw attention to the greedy capitalists that wrote in to enslave her long after abolition. In the original game, some of the landlords’ rent goes into a public treasury to finance public good, based on progressive Henry George’s single tax idea. But she revised her game because players found the virtues of democratic socialism boring. In the meantime, she moved to Atlantic City, which explains the game’s place names. Baltic and Mediterranean, the poorest properties in Monopoly, were segregated ghettos there. Oriental Avenue was a row of rooming houses rented by lower-middle-class Jews. Boardwalk, the space with the highest rent, was where African Americans pushed vacationers up and down the town’s seaside walk. Like Upton Sinclair with The Jungle, Magie’s point was to underscore the evils of capitalism and unequal land ownership. Magie hoped to alert players that, “In a short time…[they] will discover that they are poor because Carnegie and Rockefeller…have more than they know what to do with.” As in the Jungle’s case, the public largely missed the point and her creation became the most popular board game of all time when marketed by Parker Brothers as Monopoly® in 1935, paradoxically taking off during the depths of the Great Depression. It turns out that players loved nothing more than the satisfaction of bleeding their opponents dry and giving them a friendly shove down the road toward bankruptcy, especially satisfying against one’s siblings. The snowballing effect of wealth accumulation is fun to experience, if only vicariously in a fantasy version. Today, Parker Bros. prints 30x as much fake monopoly money, annually, as the U.S. Treasury does real money. They bought out Magie’s patent and that of other money games, in effect monopolizing the Monopoly game, and ironically won an anti-trust suit against a game called Anti-Monopoly in the 1970s that was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1985. In real life, though, many Americans shared Magie’s dislike of trusts, as monopolies were commonly called. Progressive-era Congress responded by outlawing companies that acquired or maintained monopolies through unfair practices.

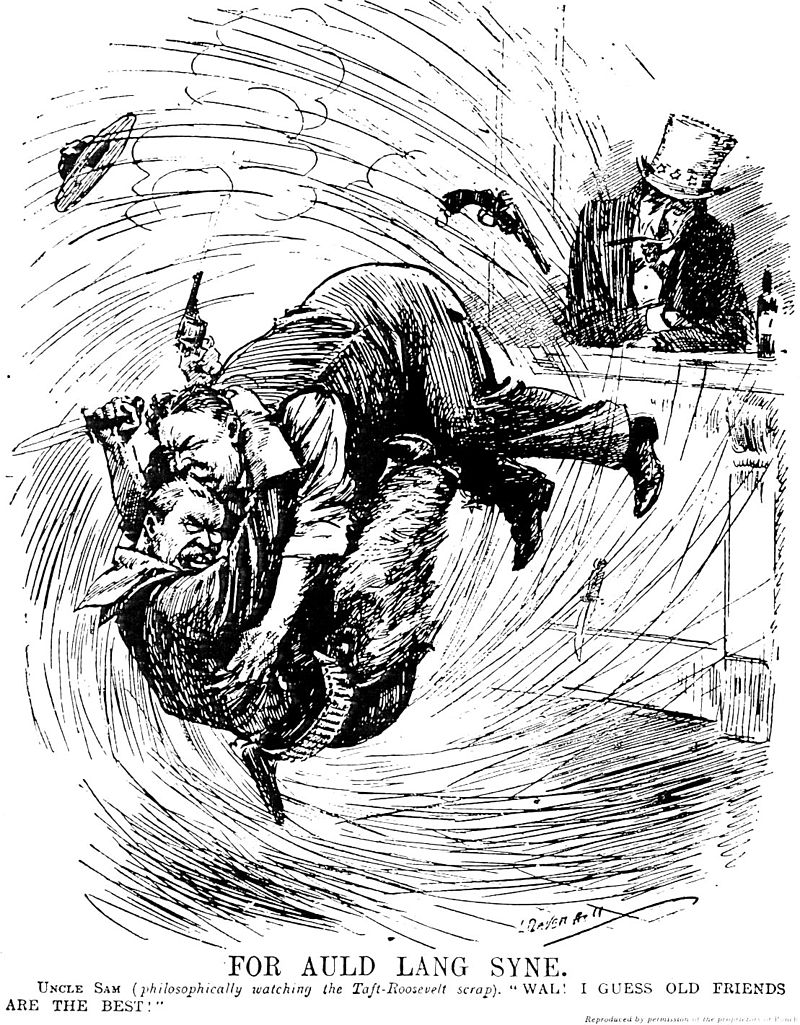

But the U.S. has a three-branch government and, just as the Supreme Court was lukewarm toward labor laws, so too they were skeptical toward the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act aimed at monopolies. The Court came to an accommodation with the Teddy Roosevelt and William Howard Taft administrations since those presidents only enforced the law in egregious cases. As we saw in the first chapter, Standard Oil was an early target, broken up in 1911, and in 1915 a federal district court ruled in favor of what became 20th-Century Fox, breaking up (Thomas’) Edison Trust and ushering in the competitive Hollywood era.

TR’s first big target was J.P. Morgan’s railroad conglomerate Northern Securities in 1902. You may remember Morgan from Chapter 1 for backing Edison and, later, Tesla after he poached Westinghouse’s Tesla patents. He bailed out the economy in 1895 and 1907 as we saw above, leading to the Federal Reserve to take such responsibility out of individual hands. The Supreme Court went along with the government’s injunction against his railroad empire in a 5-4 ruling, but Roosevelt was still fuming that his own appointee, Civil War veteran and Associate Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes, voted against and wrote a dissenting opinion. Holmes argued that capitalism encouraged competition then outlawed whoever won the competition with the Sherman Act. Wasn’t horizontal integration a natural and fair goal of any big company? TR, conversely, saw monopolies as undermining competitive pricing and told the newspapers that he could “carve a judge with more backbone [than Holmes] out of a banana,” which was funny but didn’t directly address Holmes’ concern (TR no doubt would’ve held his own on social media). Roosevelt also resented the dismissive way that Morgan had tried to buy him off when he became president, in the same way that he’d negotiate with another industrial titan. When TR first broached the subject of breaking up U.S. Steel, J.P. Morgan chuckled and contemptuously telegrammed that he would send his man down to talk to Roosevelt and work out the problem. While Roosevelt’s courage was laudable, U.S. Steel ultimately won that case in 1911.

Breaking up monopolies is a big intrusion into the free market but, left on their own, economies will naturally tend toward concentrations of power. Bigger companies gain efficiency advantages as they scale up, aka economies of scale, which can benefit consumers in the form of lower prices. Yet, if a company corners an entire market, they can raise prices to the disadvantage of consumers. The advantage of capitalism from the consumers’ perspective is competition and monopolies can destroy competition even as they bring efficiency and order to industries, the way Rockefeller did with Standard Oil. Many of today’s billionaires, like Bill Gates (former chair/CEO of Microsoft) or Mexican telecom mogul Carlos Slim, made their money by finding niches in the economy with barriers to competition. Wise investors love these “wide moats,” but they make it hard for smaller, up-and-coming firms to compete, leading to the capitalist “snake eating its own tail” as the anti-trust line of thinking goes.

Yet, the Sherman Act doesn’t outlaw monopolies outright, just those acquired through illegal or unfair practices. Also, as we saw in Chapter 1, patents award short-term monopolies through proprietary rights before the patent expires. The Clayton Anti-Trust Act of 1914 supplemented the Sherman Act by prohibiting any anti-competitive mergers. The ambiguity of illegal, unfair, and anti-competitive has complicated attempts by the Justice Department (Anti-Trust Division) and Federal Trade Commission to bring antitrust suits against companies like Microsoft (for exclusively bundling the Internet Explorer browser with its own operating system), Google (for favoring itself and its clients in searches), Amazon (for not allowing its vendors to sell their products cheaper on other platforms), and Apple (for conspiring with publishers to raise e-Book prices). After initially losing an appeal, the government essentially won the first “Browser War” against Microsoft in 1998-2000 through a compromise based on the Sherman Act, though they never broke the company up into two “baby Bills” as originally proposed. Given the dominance of its operating systems on PCs, we’ll never know — just as we can never know any counterfactual (what if?) history — whether Google would’ve emerged or Apple reemerged had Microsoft been allowed to continue bundling its browser and operating system. The anti-trust laws’ ambiguity frustrates the companies and their legal teams as they struggle to survive and compete with one another. In addition, globalization has brought American companies like General Electric and Microsoft under the jurisdiction of foreign agencies. The European Union blocked GE’s merger with Honeywell and continued to dog Microsoft after the second Bush administration settled out of court in America. Pro golf is now subject to anti-trust debate because the Saudi Arabian LIV tour accused the American and European PGAs of being monopolies and, now that the three tours have merged, they definitely are. But courts have generally given pro sports a free pass because it’s practical having one main league in each sport.

Today, Alphabet (Google) dominates Internet searching, Meta (Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, WhatsApp, etc.) dominates social media, and Amazon dominates online retail enough that each represents a concentration of power, especially with more artificial intelligence on the horizon. Still, their familiarity is convenient and their big scales allow them to develop features attractive to their customers. Big tech’s lawyers will be busy for the foreseeable future in endless cases involving anti-trust and patents. Two examples: Apple fending off legislation to ease the downloading and data sharing of outside apps on their phones; and Samsung losing a 2017 case and paying Apple for use of its slide-to-unlock technology. In the optional 2024 video below, Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Kahn explains how the FTC tasked with enforcing anti-trust laws is currently dealing with Amazon, Facebook, drug companies, and Artificial Intelligence. For Kahn, just as the separation of powers prevents a monarch from taking over the political realm, anti-monopoly laws prevent single monarchs from taking over economic sectors.

Progressive Politics: Bipartisan & Local

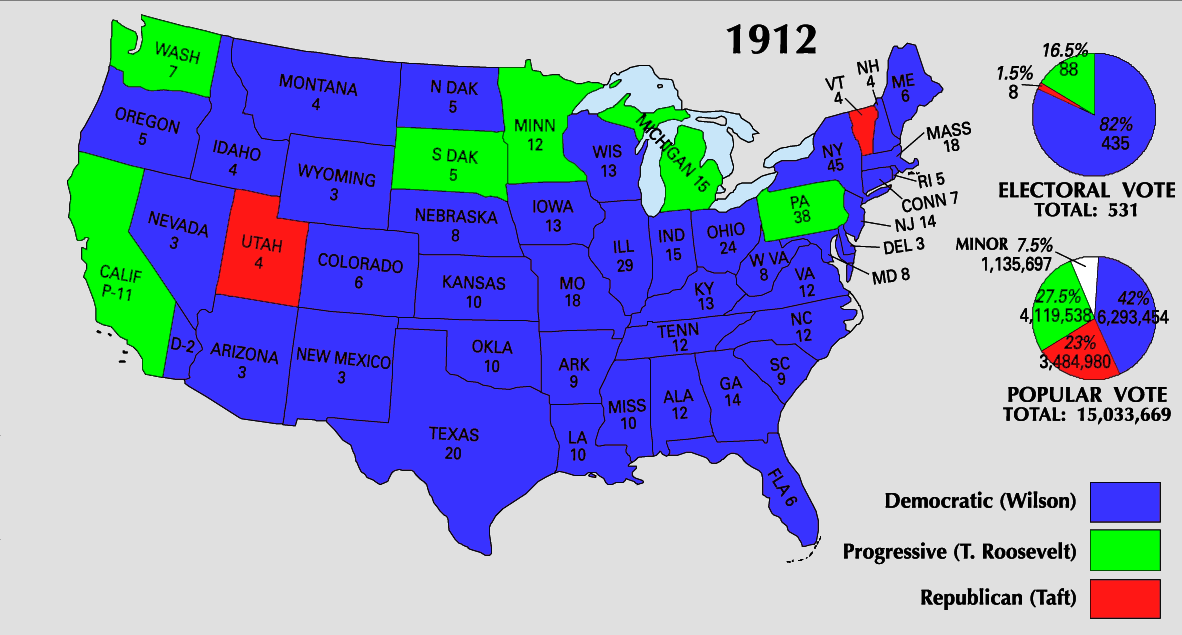

These Progressive Era battles did not break down neatly into Democrats versus Republicans. Today it’s not an oversimplification to classify most Democrats as liberal and Republicans as conservative, at least by American standards. We’ll explore that terminology more below because both terms have complicated histories, but most of us know roughly what they’ve come to mean. Each side even grades their own politicians and each other as to how loyal they stay to their party’s ideological principles. But such hardened categories weren’t defined in the early 20th century. Both parties had progressive and conservative elements within their ranks. Republicans led the charge nationally by regulating food and drugs, civil service reform (awarding government jobs by merit rather than mere patronage or the spoils system), and breaking up monopolies. Republicans also helped bring about public utilities, including sanitation, sewage, and water. Cleveland Democrat Tom Johnson pioneered the concept of publicly-owned utilities as a mayor elected by Populists and labor unions. Detroit’s Republican mayor Hazen Pingree grew vegetables in vacant lots, “Pingree’s Potato Patches,” to feed the poor during the 1890s depression.

The most famous and influential Progressive Republican at the state level was Wisconsin’s Robert La Follette, who served as governor and U.S. senator. “Fightin’ Bob” fought corporate influence on politicians and pioneered government-subsidized mass transit to reduce congestion and pollution. Wisconsin passed the country’s first environmental restrictions and La Follette capped sailors’ workweeks at 56 hours. As a presidential nominee of his own Progressive Party in 1924, La Follette won an impressive 16% of the vote. To this day, progressive politics are sometimes referred to as the Wisconsin Idea. Wisconsin pioneered the primary system to give voters a greater say in who the respective parties nominated to run in general elections.

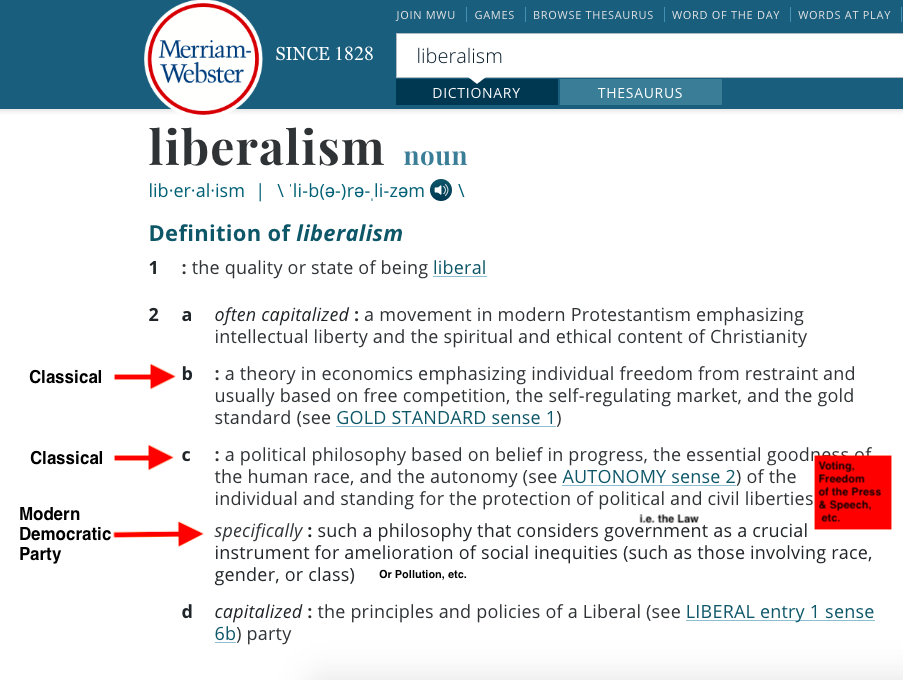

Montana pioneered campaign finance reform by restricting corporate lobbying after the Anaconda Copper Mining Co. of Butte bought off its legislature. That law was overturned, though, by Citizens United v. FEC (2010) and an unsuccessful challenge to Citizens United in Western Tradition Partnership, Inc. v. Montana (2012). A lot of Progressive politics was local rather than national or a combination.