“Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.” — Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 1865

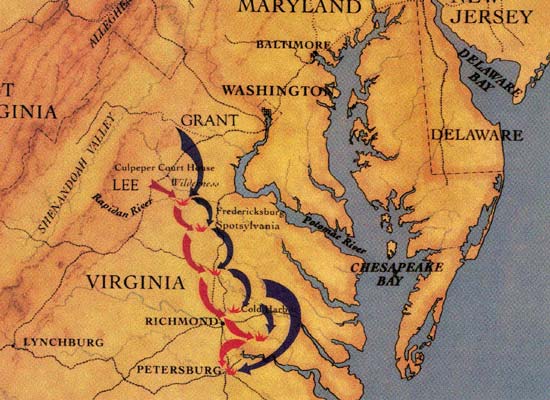

Momentum shifted in the Union’s favor in the summer of 1863. There were times in 1864 when the Confederacy nearly invaded Washington, or the North was on the verge of giving up, but Confederate forces suffered irreparable blows in 1863 on three main fronts: the West (Mississippi River), Upper South (Tennessee), and East, where Robert E. Lee failed a second time to invade the North in Pennsylvania. Three battles — Vicksburg (MS), Chattanooga (TN), and Gettysburg (PA) — turned the tide in favor of the North. European investors were evenly divided as to whom they predicted would win up until Gettysburg. Afterward, the percentage of speculators bullish on the Confederacy fell to 15%. Stonewall Jackson’s death at Chancellorsville, Virginia that spring also hurt Confederates’ chances, even though his Grays won the battle. Jackson lost his arm to friendly fire and died later from pneumonia. The Jackson-Lee combo had made the Confederates effective in Virginia earlier in the war, so the week-long bloodbath at Chancellorsville was a costly, or pyrrhic victory.

Momentum shifted in the Union’s favor in the summer of 1863. There were times in 1864 when the Confederacy nearly invaded Washington, or the North was on the verge of giving up, but Confederate forces suffered irreparable blows in 1863 on three main fronts: the West (Mississippi River), Upper South (Tennessee), and East, where Robert E. Lee failed a second time to invade the North in Pennsylvania. Three battles — Vicksburg (MS), Chattanooga (TN), and Gettysburg (PA) — turned the tide in favor of the North. European investors were evenly divided as to whom they predicted would win up until Gettysburg. Afterward, the percentage of speculators bullish on the Confederacy fell to 15%. Stonewall Jackson’s death at Chancellorsville, Virginia that spring also hurt Confederates’ chances, even though his Grays won the battle. Jackson lost his arm to friendly fire and died later from pneumonia. The Jackson-Lee combo had made the Confederates effective in Virginia earlier in the war, so the week-long bloodbath at Chancellorsville was a costly, or pyrrhic victory.

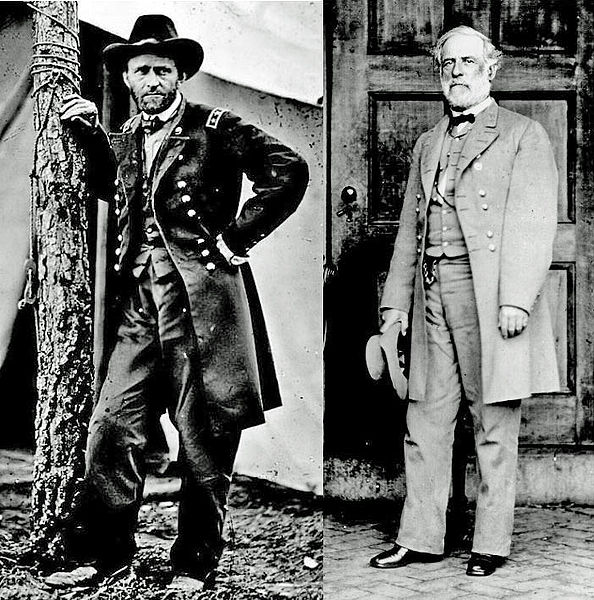

Ulysses S. Grant @ Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1864 (left) and Robert E. Lee, 1865, Photo by Mathew Brady, Montage of Two Wikipedia Images by Hal Jespersen

In the Western Theater, Union General Ulysses S. Grant continued his incessant Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, where residents were holed up in dugouts under the town. Grant eventually worked his way over the Mississippi River above the point where it widens and snuck in behind the besieged town. His forces rampaged the area in the process, living off the land, demoralizing civilians, and tearing up infrastructure. In combination with another victory at Port Hudson, Louisiana near Baton Rouge, where Confederates surrendered after a 48-day siege upon hearing of Vicksburg’s capitulation on July 7th, the Union now controlled the “Mighty Mississippi.” Animated Map Holding America’s main interior water route meant that Midwest farmers could export crops to Europe via New Orleans. Further north and east, farmers used the Great Lakes and Erie Canal for shipping, but winning the Lower Mississippi Valley swung many Butternut farmers just north of the Ohio River to the Union cause (they’d been so-called in reference to the yellowish brown color of some Confederate uniforms dyed from copperas and walnut hulls). Butternuts were carryovers from the pro-slavery northern “doughface” Democrats like presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. Copperheads was another name for northern Democrats that supported slavery and opposed the Union’s cause during the Civil War. The mines around Syracuse, New York and Erie Canal gave the Union a monopoly on salt and means to move it around. Salt gave them a critical advantage on food preservation and health (even brain function) after the Union cut off Confederate licks in the Chesapeake. Lincoln described this violent struggle for control of the Mississippi with an eloquent spin: “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”

In the Upper South, the Union made headway in its Chattanooga Campaign, giving them a shot at invading the Deep South the following year, in 1864. The Vicksburg campaign divided the Confederacy, isolating the western portion of Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, and the Union’s post-Chattanooga invasion divided the heart of the Old South in the east when they invaded Georgia.

Gettysburg

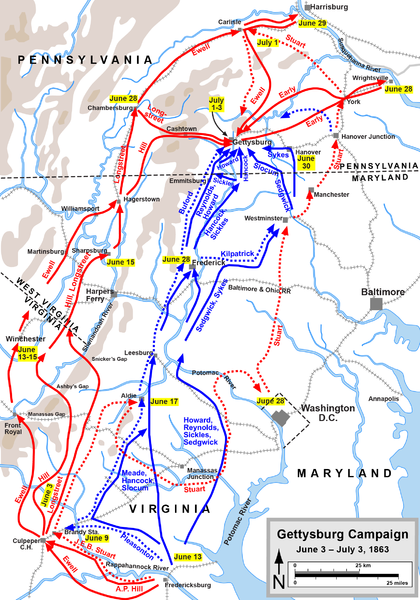

Leading the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee couldn’t gloat for long after his 10k outnumbered Grays defeated 20k Blues led by Thomas Hooker at Chancellorsville in early 1863. For one, Stonewall Jackson died after the battle, but Lee also figured that the South couldn’t win a protracted war against the North’s superior resources and decided to gamble on another northern invasion. Lee wanted to invade for many of the same reasons he had in 1862, when the Union thwarted Confederates at Antietam, Maryland. Like before, Lee hoped to make Northern civilians feel the sting of war, steal supplies (including ammo and shoes), kidnap free Blacks to sell into slavery, and gain control of key railheads — in this case, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Harrisburg was home to Camp Curtin, the largest Union arsenal. Lee hoped that by invading the North he could get to Washington, D.C. through its more exposed northern side or, at least, raze Baltimore or Philadelphia.

The Union’s Army of the Potomac was hot on Lee’s trail as he moved north, buffering itself between Confederates and Washington, D.C. This was one case where Lincoln didn’t want his army to concern itself with Richmond, but rather focus on Lee’s Army and protecting Washington. Commanding General Joseph Hooker resigned over this disagreement, as he saw Lee’s northern invasion as an ideal opportunity to attack Richmond. Lincoln, though, thought that if the Union took that bait, they’d get trapped south of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg. He cabled Hooker: “In case you would find Lee crossing north of the Rappahannock I would by no means cross south of it. If he should leave a rear force at Fredericksburg, tempting you to fall on it…getting an advantage of you Northward…I would not take any risk of being entangled upon the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence, and liable to be torn by dogs, front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick the other.”

The Union’s Army of the Potomac was hot on Lee’s trail as he moved north, buffering itself between Confederates and Washington, D.C. This was one case where Lincoln didn’t want his army to concern itself with Richmond, but rather focus on Lee’s Army and protecting Washington. Commanding General Joseph Hooker resigned over this disagreement, as he saw Lee’s northern invasion as an ideal opportunity to attack Richmond. Lincoln, though, thought that if the Union took that bait, they’d get trapped south of the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg. He cabled Hooker: “In case you would find Lee crossing north of the Rappahannock I would by no means cross south of it. If he should leave a rear force at Fredericksburg, tempting you to fall on it…getting an advantage of you Northward…I would not take any risk of being entangled upon the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence, and liable to be torn by dogs, front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick the other.”

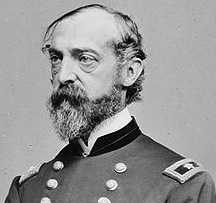

The Army of the Potomac couldn’t stop Lee as he moved north through Winchester, Virginia toward Harrisburg. These were tense times in the Union, with Democrats in Ohio and New York demanding that Lincoln release war protestors and Hooker seemingly unable to slow Lee’s advance. Lee was counting on northern Democrats to weaken the Union by gaining control of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio and pushing for a settlement. With the Union losing ~ 200 soldiers a day to desertion, the Confederacy even sent VP Lincoln Stephens to D.C. to negotiate a truce from their seeming position of strength, but Lincoln refused him. Instead, he replaced Hooker with little-known Pennsylvanian George Meade in the middle of the campaign. Meade had a steep learning curve: one day to prepare to defend his home state and, in turn, the entire Union. Confederates cut his telegraph line to Lincoln, so Meade was on his own. Lincoln waited things out anxiously in the telegraph office nonetheless, not even leaving when First Lady Mary Todd was seriously injured in a carriage accident.

Meade was a quick study and Lincoln’s gamble paid off when the two armies met outside the heretofore sleepy village of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in early July 1863. Animated Map It started as a skirmish between two small cavalry units. Lee heard that Meade’s main forces were there and, without scouting, ordered his entire army to converge on Gettysburg, even though he wasn’t entirely satisfied with the location. Within a day, around 90k Blues and 80k Grays converged on the town of 2400 — the largest assemblage of troops and artillery in North American history. Soldiers from nearly every state in the country waged relentless war for three days, often in hand-to-hand combat amidst cornfields, streets, barns, boulders, and peach orchards.

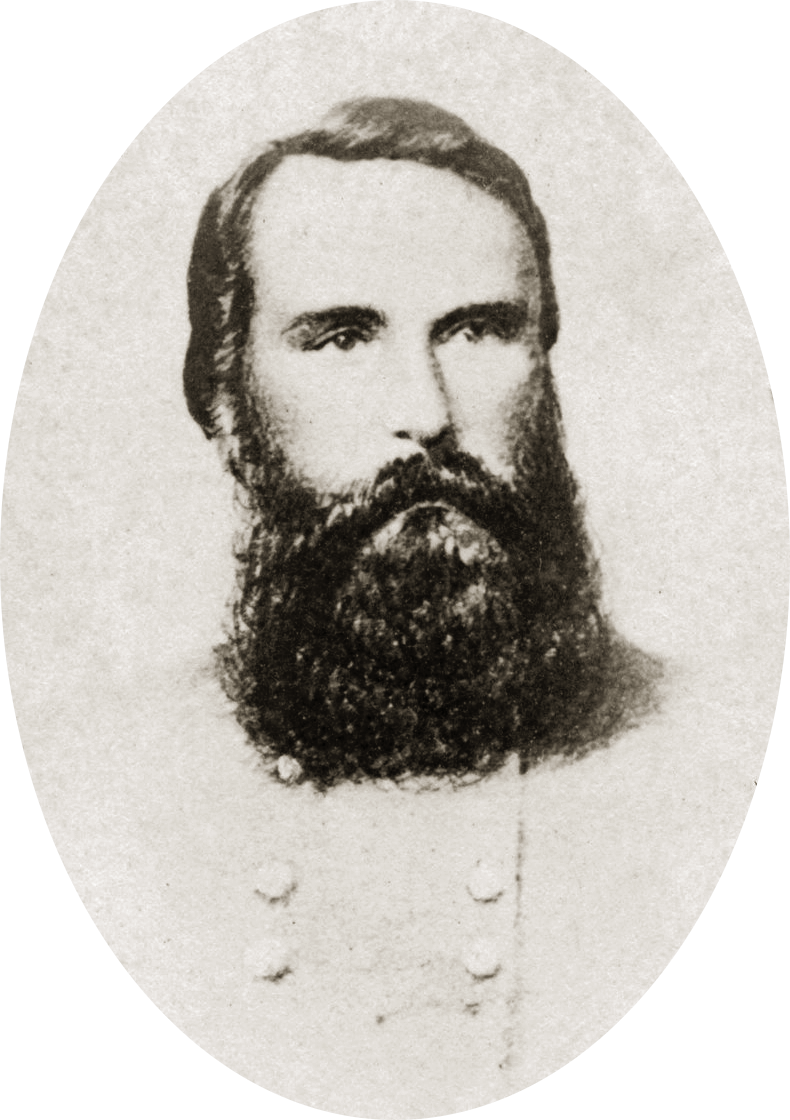

On the first day, they fought in and around the village, with victorious Confederates raising their battle flag (right) in the town square to celebrate their first victory on northern soil. Moreover, the Union lost their best general, John Reynolds. But when the initially outnumbered Union troops retreated, they fled to higher ground, giving them a good defensive position. Union reinforcements streamed in and went up the fishhook-shaped Cemetery Ridge south of town. By the time Lee’s Army of Virginia regrouped, their 80k faced a growing Army of the Potomac that swelled to 95k. Union Commander Meade warned that anyone who deserted the Cemetery Ridge would be put to death. Confederate General James Longstreet (left) thought they should attack the Union’s left flank, occupying the space between them and the road to Washington and forcing them to come down and chase them. But Commander Lee stubbornly pointed toward Cemetery Ridge and said, “the enemy is there and I am going to attack him there.” Robert E. Lee was a great general but, in this case, he should’ve heeded Longstreet’s practical advice; after all, their goal was to invade Washington. Instead of losing the battle but winning the war, as the phrase goes, Lee could have skipped the battle to win the war or at least forced the Union down off the hill before engaging.

On the first day, they fought in and around the village, with victorious Confederates raising their battle flag (right) in the town square to celebrate their first victory on northern soil. Moreover, the Union lost their best general, John Reynolds. But when the initially outnumbered Union troops retreated, they fled to higher ground, giving them a good defensive position. Union reinforcements streamed in and went up the fishhook-shaped Cemetery Ridge south of town. By the time Lee’s Army of Virginia regrouped, their 80k faced a growing Army of the Potomac that swelled to 95k. Union Commander Meade warned that anyone who deserted the Cemetery Ridge would be put to death. Confederate General James Longstreet (left) thought they should attack the Union’s left flank, occupying the space between them and the road to Washington and forcing them to come down and chase them. But Commander Lee stubbornly pointed toward Cemetery Ridge and said, “the enemy is there and I am going to attack him there.” Robert E. Lee was a great general but, in this case, he should’ve heeded Longstreet’s practical advice; after all, their goal was to invade Washington. Instead of losing the battle but winning the war, as the phrase goes, Lee could have skipped the battle to win the war or at least forced the Union down off the hill before engaging.

Gettysburg demonstrated the importance of high ground. The Confederates’ frontal, uphill assaults failed on Day Two even in spots where they had the Union outnumbered. When desperate Blues from Maine and Minnesota ran out of ammunition and bayonet-charged down Little Round Top, a Confederate recounted that the Alabama 15th “ran like a herd of wild cattle.” Thousands of John Bell Hood’s Texas Brigade and the 3rd Arkansas died in hand-to-hand combat amidst boulders in Devil’s Den, below Cemetery Ridge, as soldiers with no time or room to shoot and reload relied instead on bayonets and rifle butts. On the right flank, 1500 Federals held off 5k North Carolina Tar Heels and Louisiana Tigers. After more failures on Day Three, Lee finally ordered the heroic but futile Pickett’s Charge against Cemetery Ridge, but Union cannons mowed down most of Pickett’s men as they came across the field. When Lee first heard cheers from hundreds of yards away, he thought they’d won, but he was hearing Union soldiers. Honorably owning up to his hubris, he rode among his men and said, “All this is my fault…it is I who’ve lost the battle.” Seven million fired bullets later, the epic three-day Gettysburg battle had resulted in the highest casualty rates of the war, with ~ 50k dead or injured on the two sides.

Northerners saw the war up close for the first time as the small town was left littered with over 8k corpses and thousands of dead horses. Arms and legs dripping with blood and infested with maggots and flies piled up outside hospital tents that bellowed with screams and moans. Spectators who flocked there to rubberneck at the carnage were pressed into service dealing with scores of Union and Confederate wounded, who lay side-by-side. They did their best to bury the dead in lime-covered mass graves, but the stench was so powerful they were still rubbing peppermint oil under their noses when Lincoln arrived to commemorate the battlefield that November.

General Lee’s own health was deteriorating by this point and his Army of Northern Virginia never recovered its full strength after Gettysburg. Lee biographer Allen Guelzo wrote that, afterward, Lee “had too little left with which to limp” but argued that, despite the lack of execution, Lee was right that the Confederates’ best chance for victory lay with a northern invasion in the areas around Washington (Maryland and Pennsylvania). The Union, meanwhile, consolidated its defenses around Washington. Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ political support eroded in the South. Just as Antietam ended any hope of an overt (public) British alliance, Britain abandoned even its covert (secret) aid to the Confederacy after Gettysburg, cutting off production of two ironclad cruisers. That made it more difficult for Confederates to break through Winfield Scott’s Great Snake (or Anaconda) naval blockade. Here are videos of Blues and Grays uniting at the Gettysburg veterans’ reunions from 1913 (50th) and 1938 (75th):

Vicksburg and Gettysburg were key victories midway through the war, without which the Union wouldn’t have been in a position to win two years later. The most important thing about Gettysburg, though, was what didn’t happen. A Confederate win at Gettysburg might have brought the North to heel, breaking the Army of the Potomac or leading to Washington’s destruction. Lincoln might have been forced to capitulate or even been killed or captured. Had the Confederates made their way up Little Round Top on Day Two or across Emmitsburg Road in Pickett’s Charge on Day Three, the United States might not be here today in its present form. Nonetheless, the famous Pennsylvania battle didn’t win the war for the Union or turn an inevitable tide in their favor. They lost a huge battle at Chickamauga, in northern Georgia in September 1863, that tallied the second-highest casualty rates of the war behind Gettysburg. That temporarily blocked Union plans to invade the Deep South, which would have to wait until the following year. Moreover, at several points in 1864 the North nearly gave up and, if not for Lincoln’s reelection in 1864, made possible more by the fall of Atlanta than Gettysburg, the Confederacy very well could’ve gained independence, or at least maintained slavery. As late as March 1865, a month before the war ended, brokers bought enslaved people on the Richmond market and Dutch bankers bought Confederate bonds, if both at cut rates.

After the Gettysburg win on the Fourth of July 1863, Lincoln was relieved but surprisingly unhappy, even after word of the key victory at Vicksburg, Mississippi arrived on July 7th. He was distraught that General Meade allowed Confederate forces to retreat instead of chasing them down and finishing them off, especially since they were trapped on the northern side of the flooding Potomac River. In Meade’s defense, he was just following Lincoln’s direction to stay between Lee and the capital, and he’d heroically helped defend the country in his first week on the job. Still, the stressed-out Lincoln was dejected and frustrated that the war was going on so long. He penned the commander an angry letter, accusing him of blowing an opportunity to end the war by not chasing down Lee. “You had them in the hollow of your hand…and let them escape…you cannot imagine how upset I am.” But Meade’s battered troops weren’t spoiling for a fight after three horrific days at Gettysburg and who is to say how ferociously Lee’s troops might have fought with their backs to the flooding Potomac. Realizing perhaps that he was asking too much, Lincoln never sent the letter, though he replaced Meade shortly thereafter. Many Union forces were predisposed after Gettysburg, anyway. Less than a week after the battle, exhausted, sore, sunburned, and dehydrated troops trekked all the way across the cornfields of Pennsylvania and New Jersey to put down the bloodiest urban riot in American history: the New York City Draft Day Riots.

Draft Day Riots

Some background here is in order. Most Irish immigrants in New York were poor refugees from the Great Potato Famine of the 1840s. In America, they got low-paying jobs, often competing with free Blacks for menial labor. Southerners used Irish for dangerous work like loading cotton bales onto ships because enslaved Blacks were worth money. Once the war started, the Irish, aka the “Blacks of Europe,” were disproportionately represented on both sides’ front lines. Irishman Mathew Brady, many of whose portraits you’ve seen in the last couple chapters, took graphic photos of the war’s carnage and displayed them at his New York studio. Many of the victims were Irish.

“Incidents of the War. A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, PA. Dead Federal Soldiers on Battlefield,” Negative by Brady Employee Timothy H. O’Sullivan

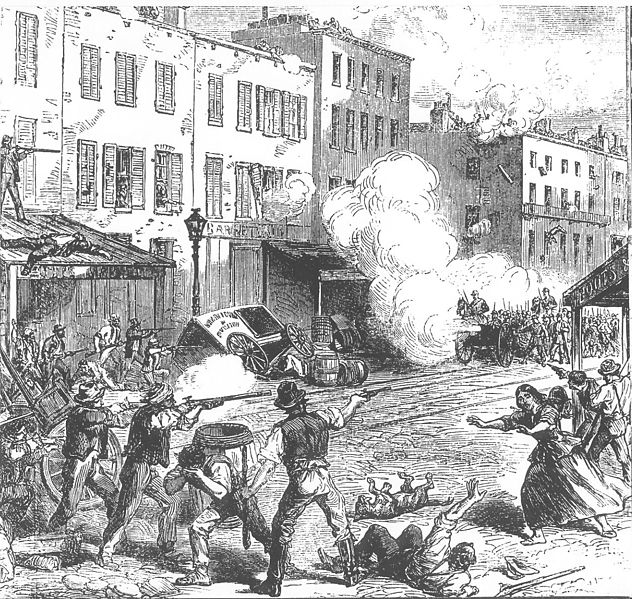

The way the Union draft worked, the rich could buy exemptions and the poor and middle classes did most of the fighting. They also scoured Europe for immigrants, including future journalist Joseph Pulitzer. Now, with the Emancipation Proclamation, the war’s aim included abolition and working-class Irish had no interest in helping to free enslaved workers. That would only lower their bargaining power for wages. Fueled by alcohol and aggravated by heat, they took out their frustrations on both Blacks and wealthy Whites in a riot that started during a draft lottery on the corner of 47th Street and 3rd Avenue. The mostly Irish Fire Engine Co. #33 broke up the lottery, arguing that firemen should be exempt from the draft.

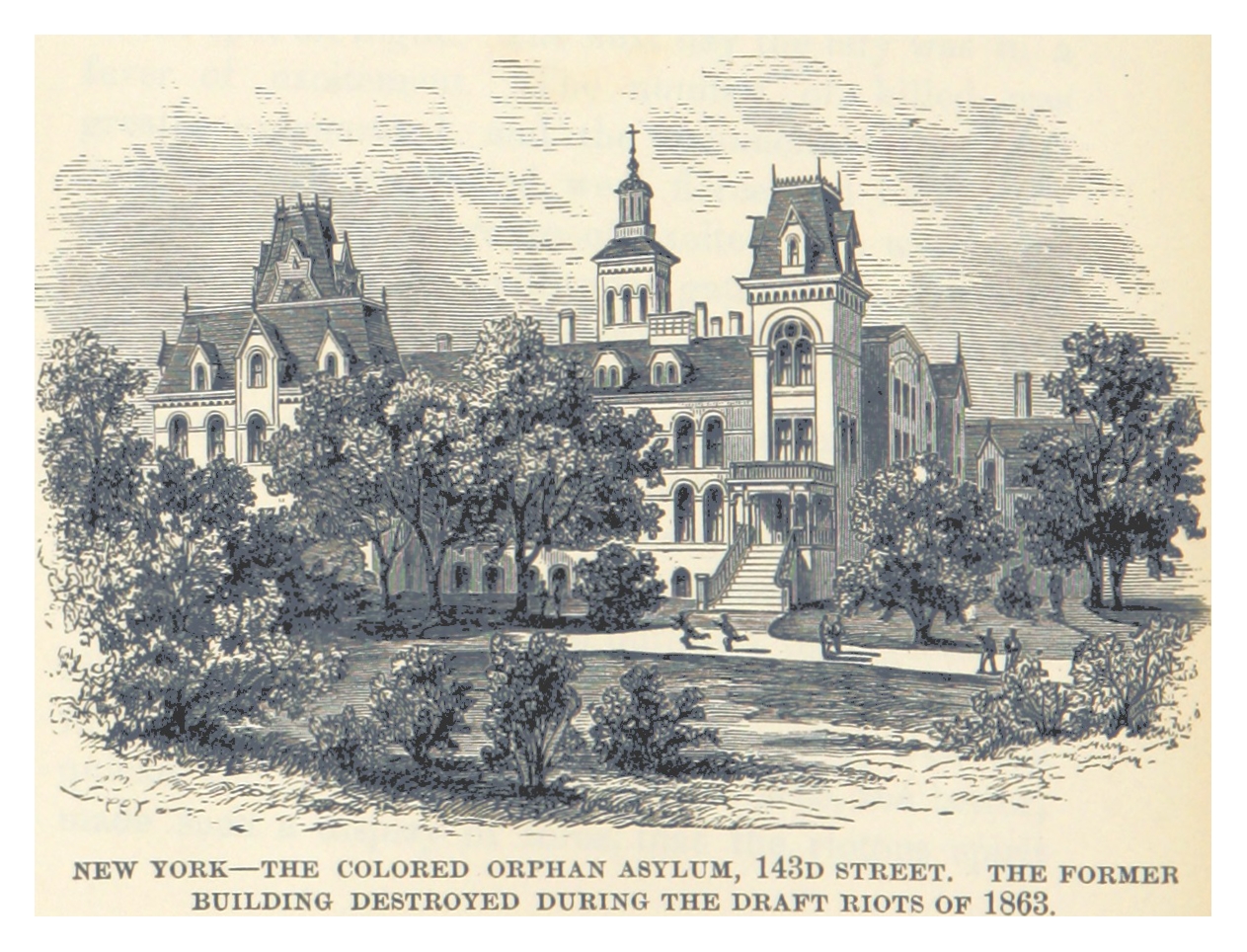

The police, many of whom were Irish themselves, lost control of the city and/or purposely gave up. (The term paddy wagon derives both from Irish “patties” arrested and from Irish police driving the wagons.) Twenty thousand troops who were usually stationed nearby had left to fight at Gettysburg. At one point, rioters nailed shut the doors and windows of a black orphanage (above), burning to death the kids inside. Women and children grabbed shovels, tongs, bricks, and coal-scuttles. The mobs went after the mayor’s home, railroads, and telegraph lines and the New York Times would’ve lost their office if not for three Gatling guns manned by newspaper staff. Some heroic police fought back and the department offered refuge to Blacks in its headquarters. Six Union Army regiments finally arrived and joined forces from nearby Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, firing cannons into the streets to put down the mobs. Some troops knew or were even related to the rioters they mowed down.

The Draft Day Riots symbolized broader discontent, as similar riots shook Albany, Newark, Hartford, and Boston on a smaller scale. New York City, especially, had been a hotbed of pro-slavery sentiment long after New York state abolished slavery in 1827, because its textiles depended on southern cotton. As we’ve stressed before, slavery was part of an Atlantic economy, not just the Southeast. In the 1850s, New York’s streets teemed with bounty hunters and kidnappers. Lincoln didn’t carry the city’s votes in either of his presidential bids, in 1860 or ’64. Not all Northerners, in general, were enthused with Lincoln turning the war into an abolitionist crusade and there were limits to how long the Union could tap working classes through the draft. Confederate arsonists, too, tried to burn New York in 1864, but Irish firemen doused all 19 of the blazes they set. Lincoln gambled with the Emancipation Proclamation, hoping the newfound support he gained from Blacks and abolitionists would outweigh the loss of support from racists or people apathetic to the cause.

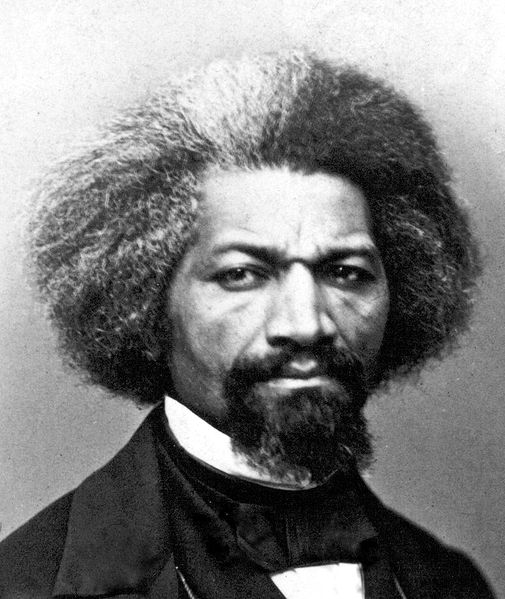

After much debate, including lobbying from Frederick Douglass and opposition from George McClellan, Lincoln decided to use black troops in combat. The soldiers fought in segregated units like the famous Massachusetts 54th Regiment or the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, making a strong contribution to their own emancipation as we learned in the previous chapter. By the end of the war, in a statistic that says as much about Confederate attrition as anything else, the North had more black soldiers than the South had white. Historians suspect that, without black soldiers, Lincoln would’ve been forced to settle for, at best, a negotiated settlement that retained some slavery in the Southeast. Douglass’ own son fought for the Union and he lobbied Lincoln for equal pay among all troops. Douglass was now firmly in the president’s camp.

Lincoln Reframes: Gettysburg Address

Lincoln had come a long way in a short time, since promising to preserve southeastern slavery in 1860 and advocating that Blacks be deported to Panama as late as 1862. While now a dedicated abolitionist and supportive of using black troops, he remained true to his earlier cause of preserving the Union. If anything, the cause of keeping the democratic experiment alive had more meaning now than ever.

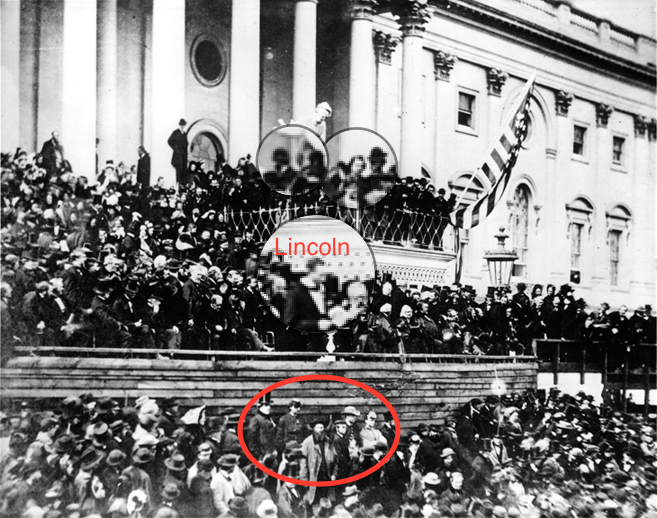

In November 1863, Lincoln was “asked to provide a few appropriate remarks” as the government consecrated a battlefield for the first time in its history. He traveled to Gettysburg to commemorate the big battle there and spoke about the Union’s mission. The battlefield was still fresh, with wolves having dug up some of the hastily buried corpses and the smell of death in the air. Few paid much attention at the time, but in his Gettysburg Address, Lincoln uttered some of his most famous words, recited in northern classrooms for generations and etched onto the interior walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. Then he wrapped things up in less than five minutes, amidst an early snow. The entire speech was only ten sentences long — so short that photographers were still setting up their equipment when he finished, which is why our only image is the fuzzy one above. The crowd stood silently at first because they didn’t think he was done. The president’s most inaccurate line was that “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here.” It’s true, at least, that the talk wasn’t strong on specifics. The president never explicitly mentioned the Union, Confederacy, secession, or slavery.

But Lincoln’s words were eloquent and inspiring. Instead of bowing to pressure and backing away from emancipation, Lincoln dedicated the fight to the proposition that “all men are created equal,” a proposition the Founders “brought forth on this continent…four score and seven years ago.” Four score (20) and seven was 87 years back to 1776, in keeping with Lincoln’s usual emphasis on the Declaration of Independence rather than the Constitution, ratified in 1788. He framed the Union’s efforts in an even bigger context, underscoring the fragility of democracy internationally and hoping that the men who died there, giving their “last full measure of devotion,” didn’t die in vain, but rather helped in making “government of the people, by the people, for the people” secure, so that it “shall not perish from the earth.” The U.S. would not only endure and outlast the current crisis, however bleak things seemed; it would provide a future beacon for other nations. Lincoln was playing to the theme now known as American Exceptionalism. He also issued a reminder to future generations of the ongoing struggle for freedom, saying that it was left “for us the living” to rededicate ourselves to the war’s unfinished cause.

As mentioned in the Secession Winter chapter, Lincoln had a point regarding democracy’s fragility. Representative government was in full retreat in Europe after a spurt of hope in 1848, and the U.S. was one of only a few major republics left, along with Mexico and Switzerland. Lincoln understood that democracy might fail altogether and that the U.S. might not survive dismemberment if the Confederacy broke away. Closer to home, Lincoln had grieving parents and relatives on his hands and had some explaining to do. Being steeped in Shakespeare and the King James Bible imbued him with a flair for expressing his sympathies and framing his cause better than any statesman in American history. Yet after the Gettysburg Address, one Pennsylvania newspaper quipped, “We pass over the silly remarks of the President…they shall be no more repeated or thought of.” A London Times correspondent wrote, “Anything more dull and commonplace it wouldn’t be easy to produce.” Lincoln wasn’t too high on it either, grumbling as he sat down, “That speech won’t scour [as in soil falling off a plow]. It is a flat failure.” Yet, Lincoln understood that quality trumps quantity and the short speech was ideally suited to the telegraph, much like the 280 characters in a Tweet®. It spread quickly to newspapers around the country and became famous even before the war was over.

Lincoln contracted smallpox on the trip but got over it in a couple of weeks. His trusted black servant/valet, William Johnson, wasn’t so lucky. Lincoln said, “he did not catch it from me…at least I think not.” Typical of the convention of his times, Lincoln referred to the adult Mr. Johnson as his “colored boy.” An unsubstantiated legend grew that, when Johnson died, Lincoln engraved citizen on his tombstone in order to repudiate the Supreme Court’s earlier ruling in Dred Scott.

Lincoln Retools: Cabinet & Generals

Despite the victories of 1863, the Union was still nowhere near winning the war by then. Nor was the South about to give up. In fact, the South now had a more compelling reason to fight because it had turned into an all-or-nothing struggle. Abolition would upend their economy and disrupt their social structure. Prior to emancipation, the South could’ve lost, tucked their tail between their legs for a few years, and maintained slavery.

Lincoln, meanwhile, was not then viewed as the successful president most of us look back on him as being. Whatever he did displeased one faction or another in the North. He was, of course, hated in the Deep South and most of the Upper South. Ohio Republican William Dickson wrote that Lincoln “is universally an admitted failure, has no will, no courage, no executive capacity…and his spirit necessarily infuses itself downward through all departments.”

Lincoln continued to revamp his command structure. He’d been hiring and firing generals throughout and found a winner at the top with a new Secretary of War. He fired the corrupt Simon Cameron and replaced him with an old adversary, Edwin Stanton. Years earlier, Lincoln had been hired to represent the defendants in a patent suit brought by the McCormick Harvest Machine Company (now International Harvester). After preparing for weeks and traveling to Cincinnati, he arrived at the trial only to learn that the better-known Stanton had replaced him. No one even bothered to notify Lincoln and Stanton didn’t acknowledge his presence, except to lampoon him behind his back as a hick. But Lincoln stayed and watched the trial. He was impressed with Stanton and filed that away instead of harboring personal animosity. Then Stanton, a Democrat, was a harsh critic of Lincoln during the first year of the war, ripping him in the newspapers. Yet, Lincoln hired him and basically said (I’m paraphrasing), “Okay hotshot, I’m out of answers. You run the war if you’re so smart.” It was a wise move, as Stanton ended up being superior to Cameron in managing day-to-day operations. He worked 15-hour days at a stand-up desk and wrote an old colleague, “No men were ever so deceived as we at Cincinnati.” Such stories, common in Lincoln lore, didn’t unfold in the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis stubbornly refused advice and Southern congressmen fought amongst themselves.

Lincoln also shook things up on the battlefield in 1863. He brought his less highly reputed but more ruthless western generals to the fore: U.S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, commanders of the Army of the Tennessee. These warriors hadn’t graduated high in their classes at West Point and were known to be rough around the edges. This is another way that Gettysburg was a turning point – not just because of the damage to Lee’s army, but also because of Lincoln replacing Meade.

Sherman became a Southerner prior to the war, serving as superintendent of what became Louisiana State University (LSU), but he supported the Union. Grant had once owned an enslaved worker named Jones in Missouri but set him free even though he was short on money. He had failed at various businesses. Many politicians and newspapers were appalled that Lincoln would hire Grant to oversee the Army of the Potomac. He was falsely rumored to fight drunk while smoking his trademark cigars. Rival officers, jealous that Grant was promoted over them because of his talent training inexperienced draftees, claimed that he was drunk at breakfast the morning Confederates launched a surprise attack on his forces at Shiloh, in southwestern Tennessee, in 1862 (his men rallied and won a costly two-day victory). In response, Lincoln retorted, “Find out the brand of his whiskey, and I’ll give it to my other generals.” In truth, Grant didn’t hold liquor well with his 5’8″ slight frame, and he binged away from work, but he wasn’t an alcoholic. When asked the reason for promoting Grant, Lincoln said, “I can’t spare this man…he fights.”

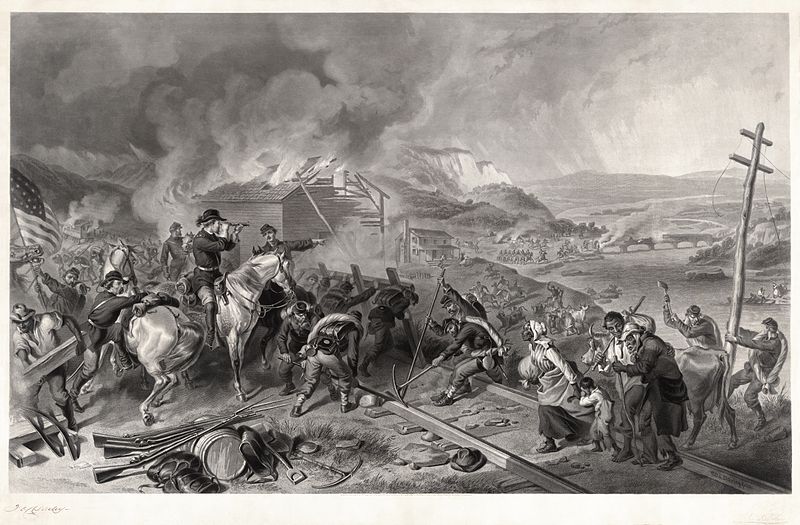

Sherman pushed for an invasive scorched earth policy into Georgia that Grant and Lincoln were both skeptical about at first because it involved Sherman leaving his army exposed, deep in enemy territory with no supply lines. His troops could’ve been swallowed up whole, never to be heard from again except as the subject of victorious anthems commemorating the birth of a new Confederate nation. The British Army & Navy Gazette called the idea either the most brilliant or foolish thing a military leader had ever done.

But Sherman’s plan was the type of strategy Lincoln himself had tried to impress on McClellan, Meade, and the others, at least toward Richmond. Now, Lincoln wanted to take the fight to the “sunny South,” as he called it. It wasn’t a matter of malice toward Southerners. Without tangible results on the battlefield, Lincoln thought he’d lose his reelection in 1864, in which case the war would likely be lost because he’d naturally attract an opposing candidate that appealed to the many Northerners who wanted to give up (spoiler alert: that will be George McClellan).

Without realizing it, Lincoln, Sherman, and Grant were putting the strategy in play that Frederich Engels described to Karl Marx in a letter two years earlier: “The loss of both these states [Tennessee and Kentucky] drives an enormous wedge into their territory. The sole route [then connecting the slave states] goes through Georgia…the key to the secessionists’ territory. With the loss of Georgia, the Confederacy would be cut in two sections, which would have lost all connection to one another.”

Sherman Skins the Hide

Sherman broke out of Chattanooga, Tennessee from Lookout Mountain and steamrolled through Georgia, decimating everything in his path. He promised to make “the South feel the heavy hand of war…to make war so terrible that the rebels would never take up arms again.” Sherman’s hard war was something akin to what we’d call total war today. Meanwhile, Grant would fight Lee in the war’s epicenter, Virginia, as Philip Sheridan pillaged farms and villages in that state’s Shenandoah Valley. Lincoln chillingly cabled Grant, “You hold the hind legs, while Sherman skins the hide.” Their goal was to destroy the South’s economy and the will of its people, expanding on the Anaconda Strategy to divide the Southeast in two, so the two snakes could then squeeze off two regions isolated from each other. Lincoln countered hard war critics by asking if they would prefer fighting with “elder-stalk squirts charged with rosewater.”

During Sherman’s March to the Sea, his “Little Devils” (mostly Midwestern teenagers) killed and stole livestock, burned crops, barns, and homes, broke levees, and tore up railroad tracks in a 50-100 mile-wide path of four columns. In a way, Sherman’s March wasn’t entirely dissimilar to a tornado cluster moving through Georgia, except slower. The official march portion of the campaign kicked off with the Battle of Atlanta, immortalized in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, culminating in the capture of Savannah on the Atlantic coast. Instructed to destroy everything of military value, the soldiers burned over 30% of Atlanta, the South’s major railroad hub and industrial center. Atlanta’s destruction helped secure Lincoln’s victory in the upcoming November election. Then, completely cut off from Union contact and supplies, Sherman issued a field order to his 60k troops to take what food they needed on their way to Savannah, bringing them into more conflict with the civilian population. Sherman had a map with census records including crop yields, so he knew where to send his “Bummers” to forage. Bummers/Little Devils looted and vandalized their way to infamy in Southern lore and even robbed graves in the Battle of Atlanta.

Sherman divided the inexperienced Confederate forces that blocked his path by feigning toward both Augusta and Macon, pulling them off in either direction, then forging between them. When Confederates did confront them, Union soldiers with Spencer repeating rifles mowed down the outgunned, mostly young and middle-aged militias. When Confederates planted land mines on the road, Sherman forced prisoners to march at the front of the line to search for them. Meanwhile, vigilantes hunted down Union foragers. Georgians destroyed some towns and crops preemptively in front of Sherman; that’s the flip side of scorched earth strategy, done to starve invading armies. Soviets employed that successfully against the German Wehrmacht in WWII, just as their Russian forebears had against Napoleon the previous century.

Sherman also freed enslaved people but didn’t want to take them along because that would’ve required yet more food. Despite his wishes, many refugees joined the growing sea of humanity as it made its way toward the Atlantic. Refugees joined and slowed the increasingly hungry army as it lumbered its way toward Savannah at 10-15 miles per day. A Union general by chance named Jefferson C. Davis took matters into his own hands in one of the columns. The Union built a floating pontoon bridge to cross Ebenezer Creek, just 25 miles from Savannah. After the white soldiers crossed, the pro-slavery Union general ordered the bridge cut away, leaving 600 recently freed enslaved people on the opposite bank, trapped between the water and pursuing Confederates led by Joe Wheeler. Several hundred perished trying to swim across while most of the rest were re-captured. Sherman approved of the heartless tactic and Davis went on to lead the first American soldiers ever stationed in Alaska. On his right flank Sherman had the “Christian General” O.O. Howard, one-armed brigade commander veteran of Antietam and Gettysburg who went to lead the Freedman’s Bureau during Reconstruction (next chapter), and founded African-American Howard University along with Lincoln Memorial in Tennessee for “mountain whites.”

“Sherman’s Boys” reached the coast after seizing Fort McAllister and would’ve destroyed Savannah just as they had Atlanta, but city leaders ransomed the cotton stored in their silos in exchange for preserving the city. Sherman presented Savannah as a Christmas gift to Lincoln in a letter. Around the same time, Lincoln got another Christmas present with Union victory at the Battle of Nashville, eroding the Confederates’ prospects in the western war. Then, Sherman’s Boys were on to South Carolina where, to the amazement of military planners on both sides, they waded through swamps at over ten miles per day holding their rifles aloft. Local Lumbee Indians, some of whom fought for the Confederacy earlier in the war, and a gang led by free Black Henry Berry Lowrie, helped them navigate the terrain. Sherman also had Oneidas from Wisconsin among his troops. Around 20-30k Indians fought in the Civil War, including slave-holding Cherokees for the Confederacy. In exchange for their service, they were allowed to sit in the Confederates’ Congress.

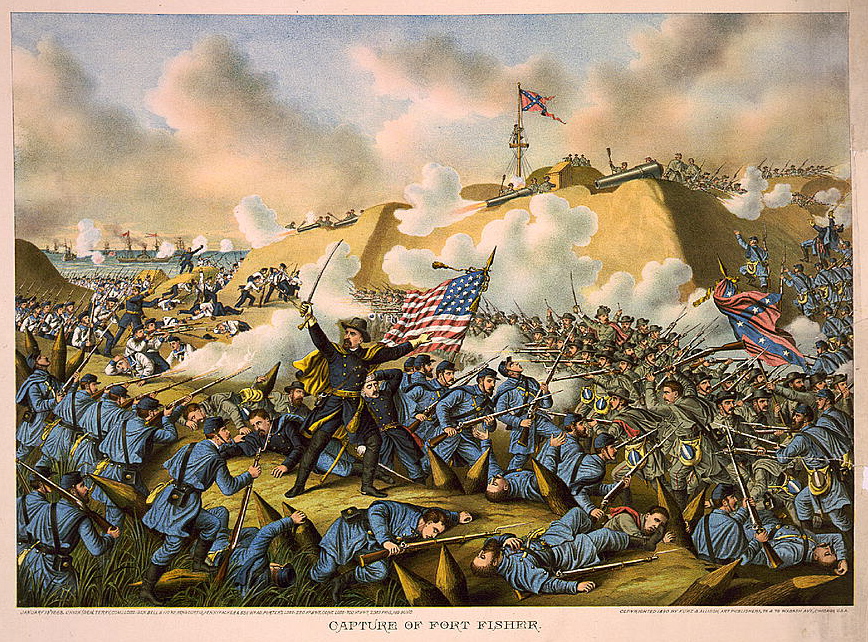

Though Sherman doesn’t seem to have ordered it himself, and even slept through it, his drunken soldiers reduced South Carolina’s state’s capital of Columbia to ashes, burning 84 square blocks. Sherman’s army wanted to burn the church where South Carolina voted to secede in 1860 but locals pointed them toward a different Methodist church, which they burned while leaving the intended target, First Baptist Church, standing. Since Charleston could be invaded from the sea — which it was that December, with Union ships taking Fort Sumter and Confederates moving John C. Calhoun’s coffin to avoid Union troops raiding his grave — Sherman’s army veered toward North Carolina, where the war wound down before he could link up with Grant in Virginia. In January, Union troops took Fort Fisher, near Wilmington, the last remaining Confederate port. Sherman went easy on North Carolina because they’d only narrowly decided to secede, but he exacted revenge on South Carolina because, “Here is where treason began, and here is where it will end.”

Capture of Fort Fisher By Union Troops, Chromolithograph by Kurz & Allison, Library of Congress, 1890

Sherman was successful, losing only 600 of his 60k troops, but left a trail of destruction along a fairly narrow path. I say narrow because the legend of his campaign grew in subsequent years so that you’d think his army marched along a 500-mile wide band killing everyone in sight, rather than 50-100. Sherman’s army revered him, calling him “Uncle Billy,” and he helped end the war by executing a daring campaign, preferring to destroy property rather than men as best he could. They say the victor writes the history but, in this case, Sherman played a bigger part in Confederate lore than Union. Even a century-and-a-half later, the name Sherman isn’t likely to pop up on any of the annual most-commonly-given-names-for-newborns lists, at least not in the Southeast. Sherman in Georgia, Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley, and Grant around Vicksburg are why resentful Southerners referred to the “War of Northern Aggression” with some accuracy. The “War Between the States” moniker popular among some post-war Southerners probably wouldn’t have made sense during the war because it conceded that it was a civil conflict whereas contemporary Confederates saw themselves as founding a new nation and fighting the “War for Southern Independence.” (Names of the Civil War)

Grant Holds The Hind Legs

Further north in Virginia, Grant’s men and their opponents hadn’t fared so well in terms of avoiding casualties. Grant calculated that Lee would run out of troops long before he did, even if he lost men at a higher rate, and that, at the very least, he’d preclude a third northern invasion by Lee. He thus fought a war of attrition against Lee, slamming into Lee’s troops relentlessly with frontal assaults and racking up staggering casualties on both sides in the spring and summer of 1864 during the Overland Campaign. Some called Grant “the Butcher,” while Lee’s men killed more Americans than Hitler or Tojo in the 1940s. In truth, neither liked war, but neither was one to shy away from a brawl. In the North, Grant’s jealous rivals and a war-weary public stuck him with the unfair “butcher” label and Southerners looking for another villainous scapegoat (besides Sherman) after the war perpetuated the myth.

At one grisly confrontation, the Battle of the Wilderness, thousands burned to death in forest fires set off by artillery. Grant refused to give up even though the Army of the Potomac had clearly lost the battle, taking a stand in the road and refusing to let the Confederates by. At Cold Harbor, neither Lee nor Grant would agree to stop fighting as wounded men baked in the sun for days, most of them dying.

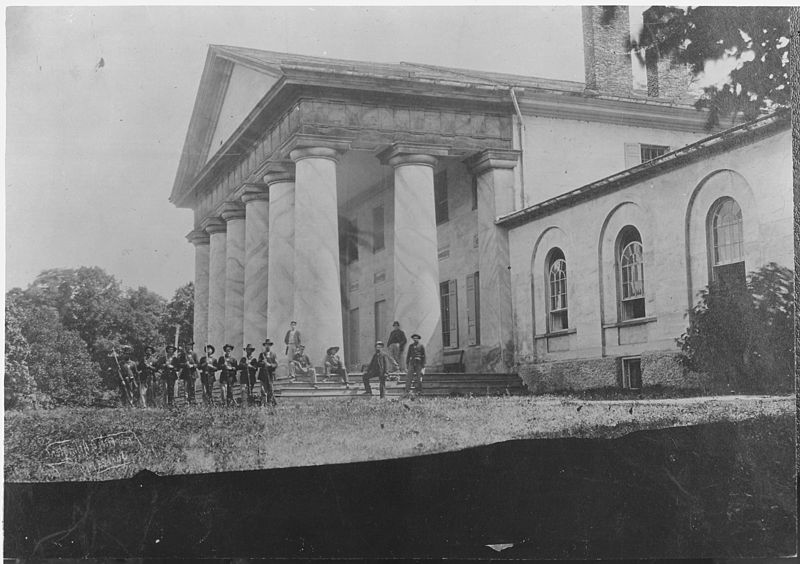

Unable to keep up with mounting corpses, the Union built a new National Cemetery outside Washington, next to Lee’s mansion in Arlington, Virginia so that he would have to spend his retirement looking at the tombstones. To Abraham Lincoln’s embarrassment, Mary Todd maneuvered to keep their oldest boy Robert out of the fray until things died down. He served as a captain under Grant in 1865. After Grant’s two-month bloodletting in the late spring of 1864, the Union was poised to lay siege to Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia.

1864 Election

The 1864 presidential election was arguably the most important in U.S. history. Many fellow Republicans wanted Lincoln out, seeing him as a decent person but unqualified for such a high office. While we normally dislike our presidents when they’re in office, it’s surprising that contemporaries also viewed Lincoln as a poor writer and speaker. Lincoln seemed to rise above the noise, even as Mary Todd felt the sting of his criticism. The Republicans re-nominated him, but opposing Lincoln for the Democrats was none other than his old nemesis, General George McClellan.

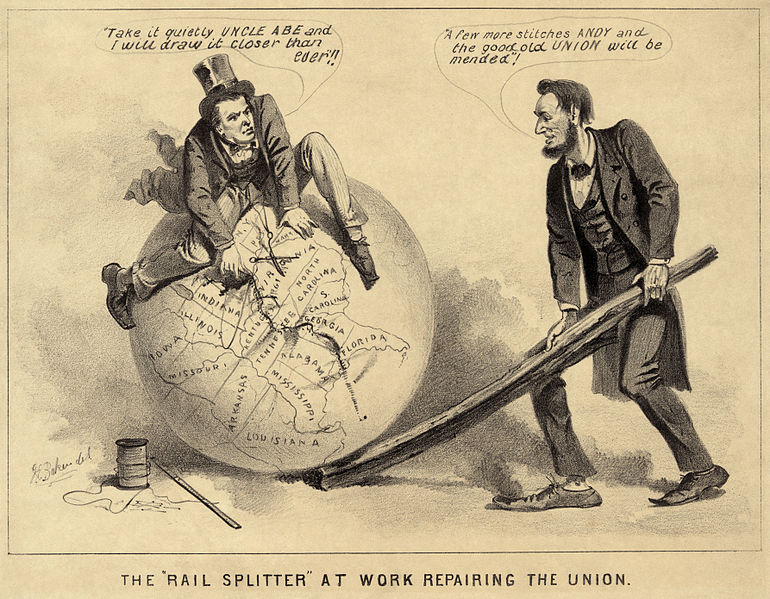

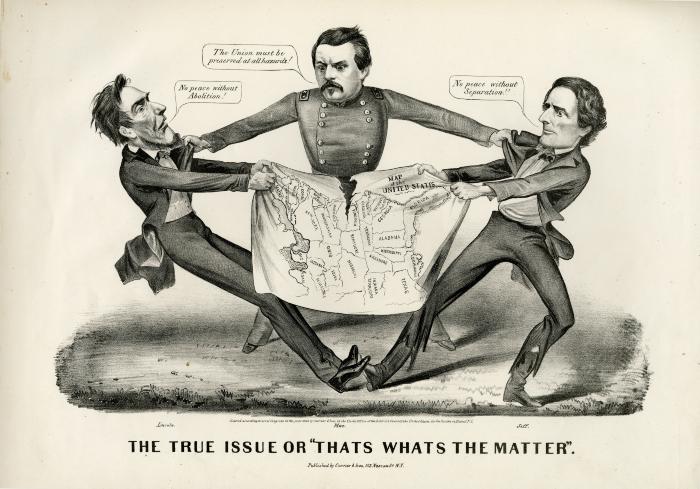

This Cartoon From New York’s Currier & Ives Firm Shows McClellan As The Only Hope for Peace, Keeping Lincoln and Jefferson From Tearing the Country Apart. However, While Only McClellan Favored Peace, Only Lincoln Was Likely To Keep the Map From Ripping (At Least From Ripping Apart a Country Free of Slavery)

McClellan wanted to drop the Emancipation Proclamation and Democrats invented the pseudo-scientific term miscegenation (mixed-race relations) to stoke interracial fears of “amalgamation.” Moreover, McClellan wanted to negotiate a settlement, a stance most historians and many voters at the time interpret/ed as meaning he would’ve given up. Lincoln not only wouldn’t give up, he steadfastly refused to drop emancipation from the Republican platform, arguing that the causes of unionism and abolition had fused. Yet the Republicans also toned down abolitionist rhetoric, instructing Frederick Douglass to lay low and completely avoiding the word slavery. To gain more votes, the Republicans carved out Union-held parts of northwest Virginia and formed the new state of West Virginia. The 39 counties actually voted on their own to secede from Virginia. Since many out west supported Lincoln, they rushed Nevada into statehood before it hit the customary threshold of 100k citizens.

Technically, Lincoln didn’t run as a Republican, though, because he added loyal Southern “War Democrat” Andrew Johnson to his ticket, creating a new National Union Party. The Senator made a name supporting universal white manhood suffrage in Tennessee, took a controversial stand against secession there in 1860, and helped Union troops defend Nashville during the war. The cartoon above shows the former tailor Johnson helping Lincoln mend the Union back together. Meanwhile, with what little money they had, the Confederacy supported their old foe, McClellan, because they figured that if he won, he’d give up and they’d win. Northern Copperheads (Peace Democrats and Confederate sympathizers) also threw in their support for McClellan, along with other pacifists, churches, and some Republicans tired of the bloodshed.

If their exhaustion seems weak in hindsight, remember that Grant was losing more troops per month than the U.S. lost in Vietnam in nine years, from 1964-1973. If the Civil War took place today, then by the spring of 1864 around five million would’ve been dead and no one knew that the war would end within a year. How many of us today would really think that any cause other than mere survival was worth that?

Because of the stepped-up efforts of Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan — most crucially the Battle of Atlanta that July — Lincoln won reelection in November. Lincoln’s electoral fortunes swung when newspapers printed Sherman’s cable to Lincoln after the battle: “Atlanta is ours, and fairly won.” Union soldiers were allowed to vote, of which 78% voted for Lincoln, while Lincoln and McClellan split votes among northern white males.

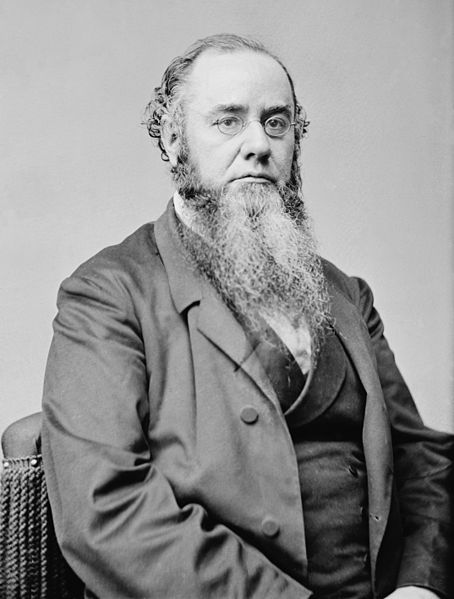

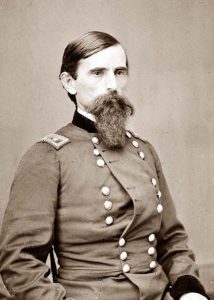

The 1864 election is one problem with the common interpretation that Gettysburg was the turning point of the Civil War. It was important, for sure, weakening Lee’s army for the upcoming battles of 1864-65; but if it had been that decisive the war would’ve ended in 1863 not nearly two years later. In July 1864, Jubal Early’s Confederate troops attacked Washington, D.C. Had the Confederates won the Battle of Monocacy outside Frederick, Maryland and/or the Battle of Fort Stevens three days later, in what’s now northwest D.C., Lincoln could have lost the presidency and maybe the war. The Union easily defended the fort, with Lincoln making a rare battlefield appearance and being told to get down so rebel snipers wouldn’t spot his conspicuous stovepipe hat. Had Lincoln lost re-election and the new Union president sought peace, the Confederacy likely would have become a nation. Sidenote: The Union hero at Monocacy, (Indianan) Major General Lew Wallace (left), went on to write the best-selling novel of the 19th century, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880).

The 1864 election is one problem with the common interpretation that Gettysburg was the turning point of the Civil War. It was important, for sure, weakening Lee’s army for the upcoming battles of 1864-65; but if it had been that decisive the war would’ve ended in 1863 not nearly two years later. In July 1864, Jubal Early’s Confederate troops attacked Washington, D.C. Had the Confederates won the Battle of Monocacy outside Frederick, Maryland and/or the Battle of Fort Stevens three days later, in what’s now northwest D.C., Lincoln could have lost the presidency and maybe the war. The Union easily defended the fort, with Lincoln making a rare battlefield appearance and being told to get down so rebel snipers wouldn’t spot his conspicuous stovepipe hat. Had Lincoln lost re-election and the new Union president sought peace, the Confederacy likely would have become a nation. Sidenote: The Union hero at Monocacy, (Indianan) Major General Lew Wallace (left), went on to write the best-selling novel of the 19th century, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880).

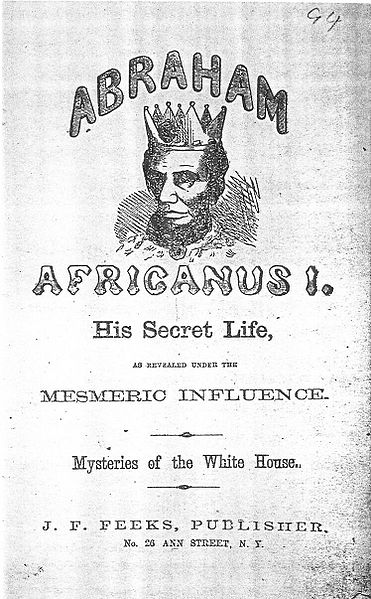

Democratic-Copperhead Pamphlet, 1864, Mocking President Abraham Lincoln, Published by J.F. Feeks, New York

What Lincoln would’ve done in the interim (November-March) had he lost the 1864 election, we’ll never know. He might have stepped up the pressure to try to secure a victory before McClellan took office if his generals and army went along with it. Instead, Lincoln won and Union forces won a decisive victory at Franklin, Tennessee in late November, dealing a crippling blow to Confederate forces in the Upper South. New VP Andrew Johnson had ruled with an iron fist keeping parts of eastern Tennessee loyal to the Union, contributing to the Union’s important victories in the Upper South. But Johnson surprised Lincoln after the election by asking if he should attend the inauguration party. Then he showed up drunk and embarrassed himself with a speech before the Senate. Johnson was suffering from typhoid fever at the time and had three glasses of “medicinal whiskey” to prep for the occasion. Frederick Douglass sensed right away that Johnson hated Blacks, a potential problem if Lincoln didn’t live out his second term. The incident didn’t bode well for how Johnson would lead when Lincoln left.

Abolition

By winter 1865, Union victory was a virtual foregone conclusion and Lincoln focused on getting a Thirteenth Amendment passed abolishing slavery. It was no easy task and involved a considerable amount of political maneuvering, though Congress rather than Lincoln spearheaded the amendment, just as they had pushed hardest for the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln mainly hoped that states would abolish slavery on their own, which several did, including Missouri, Kentucky, and Louisiana. The President has no formal role in the amendment process so Lincoln worked behind the scenes bribing, cajoling, persuading, etc. In 1861, Lincoln was only trying to hold the Union together, but the war transformed him and the country. Later, Lincoln thought that, without abolition, the war would barely have been worth fighting and only return the country to where it was to start with. He understood that the Emancipation Proclamation, a wartime act, wasn’t binding; they needed a real Constitutional amendment. In April 1864, the House of Representatives rejected the idea of an abolitionist amendment and many northern politicians either didn’t favor abolition or feared that it would complicate a potential capitulation on the part of the Confederacy.

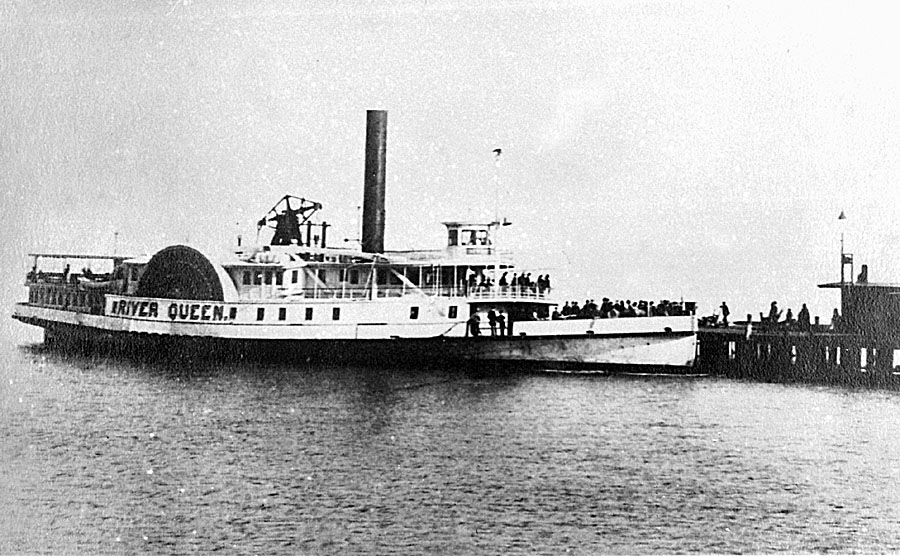

Perhaps the South could be persuaded to quit the war and stay in the country if they were allowed to keep their enslaved workers, similar to the original arrangement proposed by Lincoln in 1861. This was under discussion when Lincoln and William Seward met with Confederate representatives on a sidewheel steamer ferry at the Hampton Roads Conference in February 1865. Historians, unfortunately, don’t know many details as to what transpired aboard the River Queen because our only primary sources are retrospectives written by two Confederates, including VP Alexander Stephens. Lincoln’s old friend Stephens discussed Americans uniting in opposition to France’s invasion of Mexico (to bond by ganging up on a third party, the way Buchanan had proposed against Mormons in 1856), but Lincoln cut him off, redirecting the conversation to the all-important question of southern independence. Stephens reported that Seward was flexible on slavery but that the only ground Lincoln would yield other than financial compensation to slaveowners ($400,000,000) was a (legally problematic) delayed implementation of an abolitionist amendment. Lincoln believed that, under the Constitution, states had the right to maintain slavery, which is why the prospect of changing the Constitution permanently with an amendment was so important. The only agreement representatives struck at Hampton Roads was to resume prisoner exchanges.

Lincoln was negotiating from a strong position by early 1865 and he wanted both victory and abolition. As he put it, they “had the harpoon in the whale,” but the injured whale threatened to thrash its tail and overturn the boat. They needed to kill the whale, regardless of how many lives it cost over the late winter and early spring of 1865. He got his way, barely, when a lame-duck congress proposed the Thirteenth Amendment and sent it to the states. It only managed to pass the approval of ¾ of the states because the South wasn’t in the Union. The North fought the war to keep the South in the country, but already it saw the advantage of keeping the rebellious states out long enough to pass legislation favorable to its cause. With language drawn from the old Northwest Ordinance of 1787, that banned slavery north of the Ohio River, the Thirteenth Amendment outlawed slavery in the U.S. except for prison labor.

Lincoln Channels John Brown

In his Second Inaugural Address in March 1865, Lincoln returned to the more reconciliatory stance he’d signaled at Gettysburg, concluding that the war would wind down with “malice toward none, and charity for all.” He could’ve pointed out that a little extra malice helped get him over the top the previous fall, especially in Georgia. Indeed, Lincoln went on to point out that the bloodletting would continue until the South gave up. So he was reconciliatory and he wasn’t.

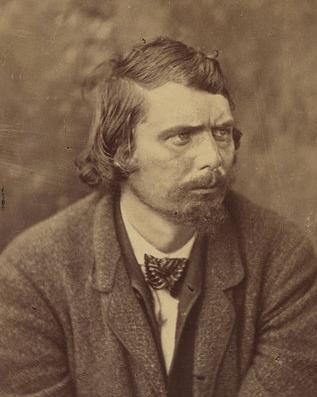

John Wilkes Booth @ Lincoln’s 2nd Inaugural In One Of The Loupes Above, With Fellow Conspirators Below, March 1864

Lincoln surprised everyone in the audience that day, including Frederick Douglass and John Wilkes Booth, by putting a religious, abolitionist-like spin on the war as a cosmic struggle resulting from God’s will to purge the sin of slavery from American soil. He’d hinted at something similar in Gettysburg. These words could’ve come out of John Brown’s mouth five years earlier, which is extraordinary considering that Lincoln had been viewed as a moderate early in the war. In 1861, Radical Republican Benjamin Wade said that Lincoln’s views on slavery were, “of one born of poor white trash and educated in a slave state [Kentucky].” That was a cheap smear even then, but Wade surely wouldn’t have said that by 1865. Only by understanding how radical true moral abolitionism was in the North can one appreciate Lincoln’s evolution on race and slavery. Or was he a pragmatic, closet abolitionist all along, doing what he had to do to put himself in a position to end slavery?

If you’ll pardon one psychoanalytic observation, only such a dramatic, history-changing cause could explain and justify to Lincoln the carnage his 1860 election and decision to fight had unleashed; mere preservation of the Union didn’t suffice. Abolitionism might have been a psychological necessity, along with being good politics. The Second Inaugural also explains why it’s difficult to categorize John Brown as a terrorist or fanatic, at least without qualifying or diluting the label considerably. The ideas of run-of-the-mill fanatics aren’t vindicated by the mainstream establishment five years after their crimes.

At no point in the Second Inaugural did Lincoln mention earlier promises to compensate slaveholders for emancipation. The speech was short and didn’t go over very well at the time, partly because Lincoln didn’t present any concrete plans for Reconstruction. But, if Lincoln had made the speech in our time, the part that would have occupied cable stations, Tweeters, and bloggers for the next week would’ve been his equation of the Civil War’s violence with the 250 years of violence toward enslaved Blacks that led up to it. “Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, ‘The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.'” Only after that whopper did Lincoln proceed to the more famous and generous “with malice toward none, and charity for all” line. The South should’ve grabbed the $400 million Lincoln put on the table at Hampton Roads when they had the chance.

The New York World, that only printed the speech “with a blush of shame,” was outraged that Lincoln would equate the blood that “trickled from the lacerated backs of the Negroes” with the carnage of “the bloodiest war in history.” The Chicago Times was likewise unfavorable: “We did not conceive it possible that even Mr. Lincoln could produce a paper so slip-shod, so loose-jointed, so puerile, not alone in literary construction, but in its ideas, its sentiments, its grasp.” Tough audience. Even Lincoln? These scathing criticisms came from New York and Illinois, Lincoln’s home state, not Alabama. Imagine how those incendiary lines went over with his future assassin, John Wilkes Booth, who was looming over the president’s left shoulder (above). Unlike Gettysburg, though, Lincoln liked the speech and said it would “wear as well – perhaps better than – anything I’ve produced.” It, too, is etched into the walls of the Lincoln Memorial.

Richmond Falls & Lee Runs Out Of Steam

By Spring 1865, Sherman had already rampaged through the Southeast and Grant’s war of attrition on Lee in Virginia was taking its toll. The South was running out of men and supplies, its soldiers now outnumbered by a 10:1 ratio. Richmond fell to Union troops on April 3rd, 1865. After Davis fled the Confederate capital in Richmond, Lincoln followed the army in and sat at Davis’ desk for hours. He had always wondered what his rival’s office looked like. The gossip was that Davis escaped in drag, but that was probably just editorial revenge for the stories of Lincoln covering himself in a shawl as he switched train cars in Baltimore on his way to Washington in 1861. Union troops finally tracked down Davis and temporarily jailed him, though he retired in relative luxury to his plantation in Biloxi, Mississippi and in New Orleans.

On April 9th, Lee sought re-supplies at a rail station near Appomattox, Virginia, but Grant beat him there in the “race to the rail.” Animated Map Lee’s trusted subordinate, General Porter Alexander, suggested dispersing the men into the woods to fight a guerrilla-type campaign against Grant, but Lee was having none of it. It was best, he said, to “look the fact in the face that the Confederacy has failed.” Grant and Lee met in a private Appomattox home adjacent to the courthouse and agreed to wind down their part of the war, which was the heart of the struggle even though smaller battles were still flickering across other parts of the country. Grant said, “Let us have peace.” In his Personal Memoirs (1885), Grant wrote:

What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us…We soon fell into a conversation about old army times. He remarked that he remembered me very well in the old army; and I told him that as a matter of course I remembered him perfectly, but from the difference in our rank and years (there being about sixteen years’ difference in our ages), I had thought it very likely that I had not attracted his attention sufficiently to be remembered by him after such a long interval. Our conversation grew so pleasant that I almost forgot the object of our meeting. After the conversation had run on in this style for some time, General Lee called my attention to the object of our meeting, and said that he had asked for this interview for the purpose of getting from me the terms I proposed to give his army.

The Union general fed the Confederates and told them to keep their guns for hunting and horses for farming, and to go home. The war died out over the coming weeks as word spread of Lee’s surrender. By surrendering his army intact at Appomattox, Lee helped prevent protracted guerrilla warfare.

McLean House @ Appomattox Court House Where General Lee Surrendered to General Grant, Major & Knapp Eng. Mfg. & Lith. Co. 71 Broadway, Library of Congress

The last battle was at Palmetto Ranch, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley near Brownsville. The last Confederate general to surrender was Cherokee Chief Stand Watie in Oklahoma. The outnumbered South had fought hard but finally crumbled in the face of superior firepower and numbers, along with the collective weight of railroads, telegraphs, industrial labor, and mechanized farming. CSA President Jefferson Davis said the South had gone to war without counting the costs. The Confederacy’s dream of founding a sovereign empire built around slavery and free trade was dead. Lincoln, the GOP, the Union Army (white and black), and abolitionists bent the arc of history.

The Last Victim

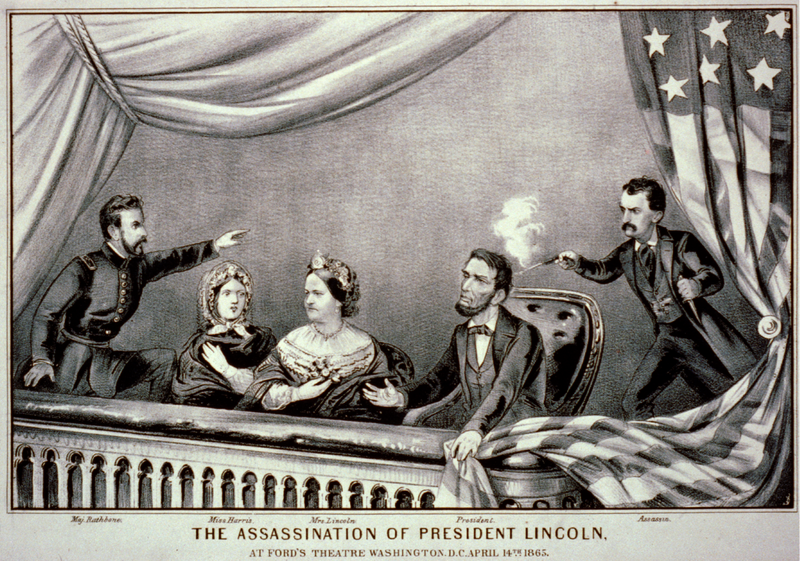

Lincoln, though, was about to make the same train trip as 1861 in reverse, this time back to Springfield, Illinois as part of his own funeral procession. He was killed a week after Lee’s surrender while viewing a play called Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater in Washington. Lincoln loved the theater and was even a fan of his own assassin, actor John Wilkes Booth. But Booth was a Confederate who despised Lincoln, especially Lincoln’s recent willingness to consider black suffrage for literate Blacks and army veterans (he mentioned as much regarding the legal status of Freedman in post-war Louisiana). According to witnesses, Booth said, “That means [N-word] citizenship, that’s the last speech he’s ever going to give, by God I’m going to run him through.” He thought the president had become a monarch by accepting a second term. Then, as with Andrew Jackson in the 1830s and today, people often thought democratically-elected leaders they didn’t like were dictators. Booth told his mother that he felt guilty having spent the war in theater while others fought on the battlefield, and it was too late for his original idea of kidnapping Lincoln to be worthwhile. Perhaps Booth could put his talents to even better use by killing him instead. Amazingly, Booth was engaged at the time to the daughter of an abolitionist senator, Lucy Hale. The actor was also locked in a bitter rivalry with his brother, Edwin Booth, a Unionist and abolitionist who was perhaps the most famous actor in America. Ironically, Edwin saved Lincoln’s son Robert by pulling him off railroad tracks earlier in Jersey City. One brother saved the son of the father the other brother would kill.

John Wilkes Booth and his conspirators all rented at Mary Surratt’s boarding house in Washington. Surratt’s son John worked as a courier in the Confederate army. Together, they resolved to take out the upper tier of the Lincoln administration, including the president, vice-president, and secretary of state. Booth knew that Ulysses Grant was supposed to attend the play that night with Lincoln and he planned to kill him, too. However, Grant’s wife Julia didn’t get along with Mary Todd Lincoln and they opted out, perhaps saving his life and the course of American history since Grant went on to become a two-term president.

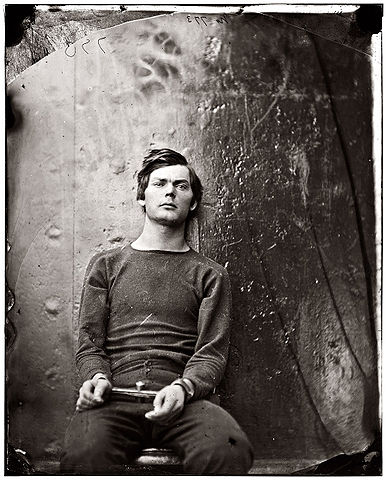

Lewis Powell (aka Lewis Payne), Taken On One of the Monitors, U.S.S. Montauk Or Saugus, Where the Conspirators Were Confined, Photo by Alexander Gardner

Booth’s compatriots didn’t hold up their end of the bargain. George Atzerodt (left) chickened out and didn’t try to kill VP Johnson. He never left the tavern he drank in to steel his nerves. Secretary of State William Seward’s would-be assassin, Lewis Powell, a strapping former Confederate POW, fought off Seward’s guards (including his son, Frederick, whom he pistol-whipped), entered his apartment and stabbed him in the cheek, but failed to slit his jugular vein. In the dark, he didn’t realize that Seward was wearing a metal splint around his neck and jaw after having been thrown from a carriage. The Seward men were seriously wounded, but both survived. William was badly scarred but went on to oversee America’s purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867.

Booth’s compatriots didn’t hold up their end of the bargain. George Atzerodt (left) chickened out and didn’t try to kill VP Johnson. He never left the tavern he drank in to steel his nerves. Secretary of State William Seward’s would-be assassin, Lewis Powell, a strapping former Confederate POW, fought off Seward’s guards (including his son, Frederick, whom he pistol-whipped), entered his apartment and stabbed him in the cheek, but failed to slit his jugular vein. In the dark, he didn’t realize that Seward was wearing a metal splint around his neck and jaw after having been thrown from a carriage. The Seward men were seriously wounded, but both survived. William was badly scarred but went on to oversee America’s purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867.

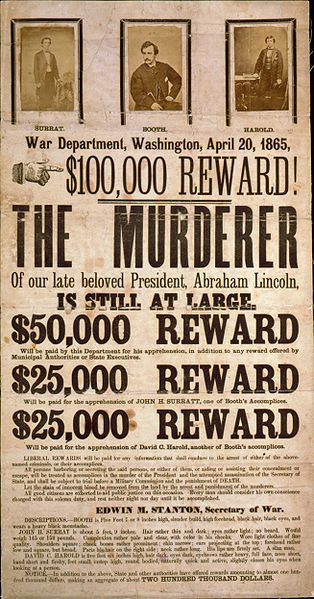

Broadside Advertising Reward for Capture of Lincoln Assassination Conspirators, illustrated with Photographic Prints of John H. Surratt, John Wilkes Booth, and David E. Herold, Library of Congress Rare Book & Special Collections Division

Booth was a recognized actor and familiar with the interior of Ford’s Theater. Earlier that day, in a small antechamber in Lincoln’s box, Booth carved a mortice to brace a tenon (stick of wood) in, the other end of which could be used to bar the door from the inside. During the first act of the play, he drank beer across the street. After intermission, he entered the theater and gave Lincoln’s valet Charles Forbes a calling card that Forbes accepted because of his fame as an actor. Booth entered the box with an eight-ounce .44 caliber Derringer pocket pistol and English hunting knife, locked the door behind him with the wooden stick, and shot Lincoln behind the ear at close range. Major Henry Rathbone, Grant’s replacement, tried to apprehend Booth, but the stronger actor broke free and slashed Rathbone in the cheek and on the arm with his dagger. Then Booth jumped down onto the stage and yelled “Sic semper tyrannis,” Latin for thus always to tyrants. This line from Julius Caesar’s assassin Brutus became Virginia’s state motto in 1776 and Booth likened himself to a modern-day Brutus (also his father’s middle name). Like Brutus, Booth saw himself as a patriot, but his patriotic duty compelled him to slay his tyrannical leader. Suiting his profession, Booth at least had some dramatic flair.

When someone asked if Lincoln’s wound was serious after they broke through the door, Major Rathbone purportedly held out his hand and said, “Yes, these are his brains.” They took Lincoln across the street to a boarding house and spread his 6’3” frame diagonally across a regular double bed where he died the next morning, the last victim of the Civil War. Coincidentally, Booth had napped in the same bed a year earlier when visiting a friend. As Lincoln passed, War Secretary Edwin Stanton said, “Now he belongs to the ages.” Stanton also took charge of the investigation. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was disappointed the other assassins hadn’t gotten Stanton and VP Johnson, which would have “made the job complete.” By chance, Lincoln started the Secret Service the day before his assassination, but it was only for ferreting out counterfeiters prior to 1902. They disinterred Lincoln’s beloved son Willie and the two made their way back to Springfield, their procession stopping in major cities along the route. In New York, 500k onlookers, a quarter of the city’s population of two million, swarmed 5th Avenue for the processional. Even in the countryside, mourners lined the tracks to catch a glimpse through an open boxcar door of a soldier guarding two caskets, one big and one small.

The ensuing manhunt was one of the biggest in history, with a $100k price tag on Booth’s head and several unfortunate lookalikes accidentally being shot in the North. After his horse fell on him, breaking his leg, Booth limped across Maryland, getting his leg set by Dr. Samuel Mudd. Others said he broke his leg when he snagged his spur on the bunting below Lincoln’s box and landed awkwardly on stage. Eventually, forces surrounded Booth in a barn at the Garret Farm in Virginia, set it ablaze, and shot him. They drug him out as he choked to death on blood while photos of actresses fell from his pocket. Rumors of his survival and escape to Texas and Oklahoma lingered on because all of the troops present at the barn had a stake in saying it was him to get a portion of the reward. According to the men who shot him, Booth’s last words were “useless, useless.” As indicated by his journal, he’d seen southern newspapers and realized that he wasn’t being lauded as a hero by most Confederates, despite Jeff Davis’ approval.

Like Brutus, Booth only succeeded in elevating his victim to sainthood. Lincoln’s death on Good Friday suggested that, just as Christ died to save souls, Lincoln had died to save the Union. His popularity shot up even among the millions of Northerners who’d loathed him just a week earlier. The following day the Richmond Enquirer, of all papers, headlined with, “The South Has Lost Its Best Friend.” Booth had done the region a disservice because it’s likely the northern government would’ve gone easier on the South had Lincoln not been killed.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Slavery is the only issue so far that American democracy was unable to work out, so it was settled instead on the battlefield. Outright slavery was dead in the U.S. after 1865. At least on paper, the war secured the unity of the country, with no sign of secession in the early years of the 21st century other than some marginal grumbling (e.g. Texas under Obama, California under Trump). Linguists have even tracked a subtle change in the language after 1865, as people started saying the United States is this or that, instead of the United States are… Still, the Southeast didn’t re-integrate enthusiastically and, for a century afterward, became instead what journalist Tony Horwitz called (harshly, if somewhat accurately) a “stagnant backwater, a resentful region that lagged and resisted the nation’s progress.” Union and emancipation, the two great achievements of the Civil War, were both compromised in the century that followed as resentment boiled in the South and African Americans transitioned from slavery into lives of poverty, discrimination, violence, intimidation, and second-class citizenship.

But at least full-blown slavery was abolished and the country stayed intact. That unity forged at the cost of 720k lives and possibly another 50-100k civilians — what would be at least seven million proportional to today’s population, including nearly 20% of fighting age Southern males. Civilian casualties are harder to measure, but most historians estimate north of 50k, almost all in the South. Most of the guerrilla fighting around the periphery, extra-judicial executions, and torture never made the history books. Old estimates of 650k soldiers killed have been revised lately as historians have learned how many immigrants died that were never registered with the U.S. Census. Entire towns in the South lost all their eligible husbands and fathers, leaving young women with no one to marry. An astounding 73k Union soldiers died of syphilis contracted from camp-following prostitutes. Another 44k died of dysentery (diarrhea). Counting both sides, dysentery was the biggest killer in the war. A quarter of the 60k who underwent amputations died from diseases caused by unclean saws and hands.

Virtually no one in the South and few in the North were untouched or unaffected by the psychological trauma, as nearly everyone had loved ones killed or wounded in the war. The cost of the war — around $10 billion in 1860 dollars, or $300 billion today — could’ve more than paid for the large-scale planter compensation plan Lincoln advocated at the outset but, then again, the South wasn’t planning then on losing either the war or their enslaved workers.

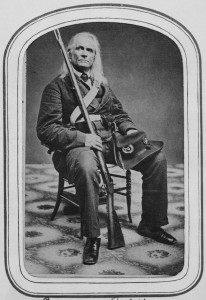

At stake was the West and America’s future. The North won both, though they never realized the Free Soilers’ dream of an all-white workforce. They freed enslaved workers but never sent them to Central America or Africa. Through Lincoln, the Republicans fused Free Soilers with white evangelical and free black abolitionists, bound together by a commitment to preserve the United States. Backed by superior industry, a bigger population, more food-producing farms, and an army whose leadership improved over the course of the war, they outlasted the Confederacy, eclipsing their dreams of independence, slavocracy, and free trade. Edmund Ruffin (left), the Fire Eater (and pioneering soil scientist) who fired the first shot at Fort Sumter, committed suicide in 1865 rather than “submit to Yankee rule.”

Even as the war was being fought, Northern congressman un-encumbered by southern representatives were giving away western land to farmers and railroads, encouraging expansion. Lincoln launched the first transcontinental railroad during the war as a way to tie the North to the growing California economy, and a telegraph line preceded it. The government and military grew around 10x bigger each, spelling doom for the Plains Indians whom the North turned their wrath on even before finishing off the South. When he arrived in Washington, Lincoln saw three separate countries: the North, the Confederacy, and a remote economy in California spurred by the Gold Rush (even though California was, by then, a state). In between the Midwest and California, Native Americans lived freely on the Plains and in the Rockies, obstructing the advance of white settlers and railroads. By the time Lincoln left office, the government was well on its way toward tying the three regions of the country together and subduing Plains and Southwest Indians. There were several horrific but little-known battles between the military and western tribes during the Civil War, including the Dakota War (1862), Snake War (1864-68), and brutal Bear River Massacre of Shoshone Indians in Idaho. The U.S. government gained control over the Lower 48 in the 1860s. Lincoln was also motivated to bring the West under Union control because he feared that the South would encroach on that territory if they won.

Lincoln also wanted to educate workers, especially in frontier areas. In 1862, the government issued land grants to found colleges featuring agriculture and engineering along with liberal arts (including Greek & Latin) — schools that today end in State or A & M, along with Rutgers, Arkansas, Purdue, and Clemson, and some that were private or partially private like Cornell University and M.I.T. in Boston. The first recipient was Kansas State Agricultural College, today Kansas State, in 1863. Many of the colleges in the Upper South, Plains, and Midwest are land grant schools, as is the University of California-Berkeley. Land grant money also built up schools that began before the war, like Louisiana St. (LSU) and Wisconsin.

The country maintained its strong agricultural base, but embraced industry, banking, and construction wholesale, while the Old South faded into memory. Southern aristocrats lost power just as feudal barons and lords would in Europe around the time of World War I, while “new money” industrial magnates rose to the top of the economic ladder. Congress passed tariffs for many years to come, helping to incubate American industry. The Industrial Revolution kicked into high gear and was itself propelled by the war. The Union Army’s need for beef led to the first mechanized factory in world history: Philip Armour’s meatpacking plant in Chicago, a precursor to the assembly lines of the next generation. Samuel Colt won the contract to provide rifles. Government orders demanded that military uniforms be sewn on a mass scale, propelling the advent of sizes in clothing. Before that, tailors measured people individually.

Hospitals with nursing staffs evolved so that the Union could triage casualties. The government stepped into a new role coping with the dead during wartime, using dog-tags, notifying next-of-kin, developing an ambulance corps, building national cemeteries, and establishing Memorial Day. The military started a pension system for survivors. Photography advanced as journalists raced to document the conflict (one reason for all the photos of dead soldiers is that battle scenes would’ve been blurry). Baseball spread from big northeastern cities across the country as bored troops passed the time between battles, spreading to the South and becoming the “American Pastime.” Before POW camps degenerated midway through the war, Union prisoners taught their southern captors baseball. The war also brought us Thanksgiving, as Lincoln and Grant strove to remind Americans of their historical unity, and Cinco de Mayo, as Mexico staved off France’s attempt to take over its country while the U.S. was too pre-occupied to enforce the Monroe Doctrine.

Then there were more intangible costs. How many soldiers never became husbands and fathers because they died on the battlefield? How much labor did they fail to contribute to the country’s fields, mines, offices, and factories? Were there any geniuses among them, any future Einsteins or Edisons, who might have made a lasting impact, cured cancer, or invented a labor-saving tool we still lack today? How much hate and bitterness was engendered between North and South, and how much lingered for at least a century afterward? Could it all have been avoided by better statesmanship between blundering politicians as some historians have charged or was slavery a logjam that necessitated violent upheaval? Based on slavery’s continuing expansion as of 1860 and the plantation owners’ unwillingness to accept compensation, it seems that war was the only path to emancipation.

Optional Reading & Viewing:

Civil War: 150 Years (National Park Service)

Battlefield Research (Civil War Trust)

Civil War-Era Collection of Primary Sources (Gettysburg College)

Explore: Visualizing Emancipation (NEH / Univ. of Richmond)

Civil War History & Studies (Jonathan Allan)

Tony Horwitz, 150 Years of Misunderstanding the Civil War

Elizabeth Mitchell, “How Abraham Lincoln Confronted — And Spread — Misinformation” (TIME, 10.6.20)

Michael Ventura, Did Abraham Lincoln Deserve a Second Term?