“The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: if it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. The millions in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.” — Franklin Roosevelt, 1932

In the previous chapter, we saw that hungry, unemployed Americans demanded a new government strategy by the end of Herbert Hoover’s presidency in 1932. They got it in the form of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, but there was more continuity between Hoover and the early New Deal than most people realize, and more mixed messages coming from Franklin Roosevelt’s campaign than most historians remember. Democrats were also anxious to end Prohibition and Roosevelt’s theme song of “Happy Days Are Again” captured that mood even if Franklin himself wavered on the drinking issue. What’s interesting in retrospect is that Roosevelt wasn’t so much campaigning on the government intervention that characterized his coming administration as he was lambasting Hoover for too much intervention.

Out of one side of his mouth, Roosevelt (FDR) criticized Hoover for raising taxes, overspending and putting too many “on the dole” (welfare), not too few. Roosevelt’s VP candidate John Nance Garner of Texas accused Hoover of “leading the country down the path of socialism.” The Democratic Platform of 1932 called for a 25% reduction in federal spending, a balanced budget, and less government interference in private enterprise. From the other side of his mouth, Roosevelt told the appropriate voters on the left that he’d do more to help people and he’d already done just that as governor of New York with work programs and direct relief. The quote at the top of the chapter from a 1932 commencement address at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta promises government intervention, for instance. That was more in line with what actually happened once he got in office when his administration unbalanced the budget, expanded the government, and interfered with private enterprise more than any in history. We often accuse politicians of betraying campaign promises once they get in office when, really, they just encounter opposition or changing circumstances. In FDR’s case, though, he seems to have been either completely full of baloney or, to put it more charitably, very flexible and adaptable. Voters often respond more to personality and other subliminal messages than content and were clueless, forgiving, or adaptable enough themselves to vote Roosevelt into office three more times, in 1936, ’40 and ’44. Obviously, something worked and in 1932 they were, above all, desperate. In the 1932 election, there was indeed a candidate who promised more spending and government intervention as a solution to the Depression, but it wasn’t FDR; it was democratic socialist and Presbyterian minister Norman Thomas, who garnered 2% of the popular vote. As for FDR’s mixed message of doing more with less, Hoover called him a “chameleon on plaid.”

It’s no wonder that Hoover hated Roosevelt’s guts. After FDR crushed him in the Electoral College 472-59, winning 46 of 48 states, Hoover wanted to work with the incoming administration during the five-month interim between the election and inauguration. Roosevelt gave him the cold shoulder to accentuate the supposed contrast between their two approaches. FDR told one reporter off the record that the country’s troubles “weren’t yet his baby” and went fishing in the Caribbean. When he returned via Miami, an anarchist in the mold of the ones who’d shot McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt shot at Franklin five times but missed. When Franklin’s limo swung by 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to pick up Hoover on the way to his swearing-in ceremony in March 1933, you could have cut the tension between the two with a knife. Nonetheless, the tradition of president-elects picking up incumbents and traveling to the inauguration together to underscore the peaceful transition of power dates back to Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren in 1837 and continued through Trump and Obama in 2017.

Like Hoover, FDR wanted to firm up the banking sector, convince industry to keep wages artificially high, and create jobs through public works. Roosevelt aide Rexford Guy Tugwell said years later that, “We didn’t want to admit it at the time, but practically the whole New Deal was extrapolated from programs that Hoover started.” FDR’s cabinet was more radical than Hoover’s, though, when it came to the scale of intervention. Their main thrust early on was job creation, similar to what Hoover accomplished on a small scale with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation starting in 1932, along with that year’s Emergency Relief & Construction Act. Hoover wanted to launch big public projects like an interstate highway system, but he didn’t benefit from as much congressional cooperation as FDR. FDR criticized the RFC on the campaign trail as a sop to big business, but then used it to jump-start the New Deal, and it continued as a successful bridge between government and industry throughout World War II and the Korean War. While not preferring handouts, Roosevelt also made concessions on direct food relief that Hoover didn’t, like what he had already pioneered statewide as New York Governor. The New Deal started providing free lunches at public schools.

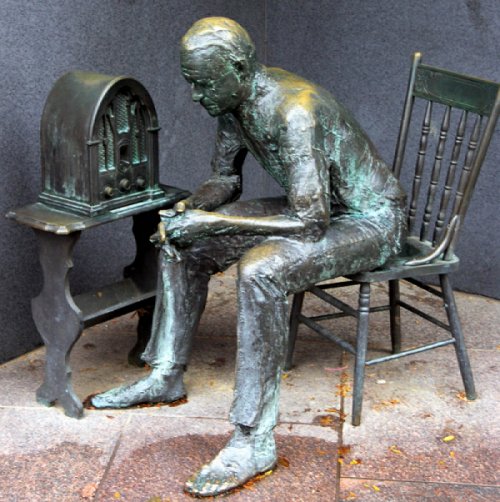

Like any president, FDR’s first order of business was to build a team around him. Most important to the New Deal were Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes and Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, the first female cabinet member in American history. These two mainstays stuck it out through Roosevelt’s entire presidency, through thick and thin. Another early New Deal architect, Harry Hopkins, Secretary of Commerce, organized most direct food relief. FDR, the New Deal’s public face, got his message to the people through radio addresses called fireside chats, emphasizing that the government was shouldering the burden of shoring up the economy. Hoover had barely taken advantage of radio, let alone embrace the concept of government as a safety net. FDR’s paternalism was a welcome shift from Hoover’s harder-nosed attitude for many and he won over even more friends by backing the repeal of Prohibition. Hoover was famously dry, whereas FDR wisely slaked voters’ thirst by waffling over to wet just prior to the election. Even before the Twenty-First Amendment repealed the Eighteenth, a new law legalized beer up to 3.2% alcohol content. People didn’t just want to drink legally; alcohol was a major industry and the country needed to put more people back to work. Alcohol also provided most tax revenue for many states prior to Prohibition, and its ban cost the federal government $11 billion in lost taxes over 14 years, plus $300 million lost to enforcement (PBS). According to one unsubstantiated legend, FDR confirmed the key decision to back repeal while drinking beer at a White House dinner.

Post-Prohibition alcohol was more regulated, though. Aside from bottles listing alcohol content, states instituted drinking ages and the government outlawed bribing voters with booze on election day — a time-honored American tradition dating all the way back to George Washington.

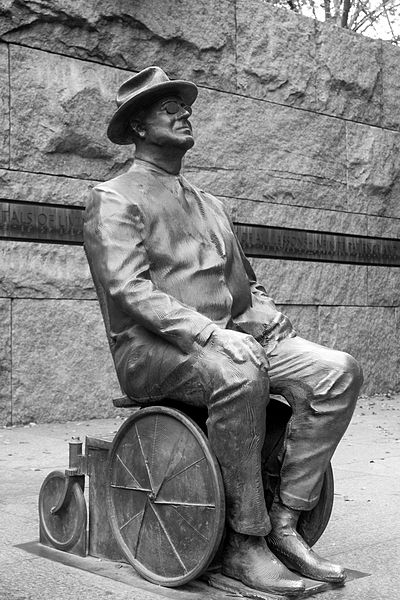

FDR was a pragmatist. When asked about his ideology, the polio-stricken FDR said only that he was a Christian and a Democrat and, beyond that, he was willing to try almost anything (some historians now suspect FDR might have suffered from Guillain-Barré Syndrome rather than polio). New Dealers did try almost anything and some of it worked and some of it didn’t. FDR’s aid Raymond Moley said, “To look upon these programs as the result of a unified plan was to believe that the accumulation of stuffed snakes, baseball pictures, school flags, old tennis shoes, carpenter’s tools, geometry books, and chemistry sets in a boy’s bedroom could have been put there by an interior decorator.” When another FDR adviser was asked if the basic economic principle behind the New Deal was sound, he replied that he wasn’t aware that it had one. There was no dramatic declaration or Emancipation Proclamation to announce a new strategy or present a master plan. The Depression didn’t lend itself to a simple, one-stroke solution because, as we saw in the previous chapter, it didn’t result from a singular cause. New Dealers tinkered as pragmatically as they could and, in the process, reshaped the relationship between Americans and their government — for better and/or for worse depending on one’s political leanings. Whereas the Depression led to fascism in Germany (next chapter), it bolstered liberal democracy in the United States. FDR underscored the stakes in a 1938 state-of-the union address, arguing that democracy is endangered if the economy doesn’t “distribute goods in such a way as to sustain an acceptable standard of living.”

By talking directly to Americans and promising them he had their backs and would create work for them, FDR dramatically expanded the expectations of the presidency and set a difficult standard for subsequent leaders to match. Many — including John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and (more surprising given his conservative platform) Ronald Reagan — looked to Roosevelt for inspiration. Barack Obama read six books on FDR between his 2008 election and ’09 inauguration. FDR’s administration was controversial then and now because today’s Democratic Party grew out of the New Deal framework. At the outset of Obama’s administration in 2009, conservative columnist Jonah Goldberg opined that “since the Democratic party is still for all intents and purposes a Roosevelt cargo cult, any Democratic ‘comeback’ would be a comeback for New Dealism as well…for liberals, to question [New Deal dogma] is akin to casting doubt on the geocentric universe in the 14th century” (see optional article below).

While the Progressive Era laid the foundation for intervention (Federal Reserve, Federal Income Tax, antitrust, child labor, and food and drug regulations), most Americans understand the New Deal as the main starting point for discussion about the appropriate role of government. Should, for instance, the government create jobs or provide a safety net for the poor, unemployed, elderly, or people with disabilities? Should the government take an active role in promoting home-ownership over renting? In this chapter, we’ll analyze how successful New Dealers were at accomplishing their goal of Relief, Recovery, and Reform (the “3 R’s”) and examine the long-term legacy of expanded government intervention in the economy.

First New Deal: Relief & Recovery

During the early New Deal, they hadn’t yet transitioned to the most lasting reforms of the Second New Deal (1935- ). Repealing Prohibition didn’t significantly lower unemployment, but it boosted morale and strengthened FDR’s relationship with the people. That was no small matter given his blue-blood background. Despite his patrician Northeast upbringing, FDR strove to connect to people all over the country, from the rural South to the Great Plains. Most urgent, toward the beginning, was the tattered and precarious state of American finance. Bank failures were rising again as FDR took office, with 4k closing in 1933 alone. Nine million savings accounts had been wiped out since 1929. Roosevelt closed all banks for a four-day “bank holiday.” They subjected them to what we’d today call stress tests to ferret out weaker ones, which were closed, and recapitalized the remainder. More than 5k banks in business before the holiday (around 5%) never reopened though the Treasury Department assisted their depositors.

Roosevelt sold the bank holiday through his first fireside chat — broadcast on a cold Sunday night as millions of Americans huddled around the stove with the lights out to save on electricity. He told them that “hoarding was now out of fashion” and that on Monday they should return their cash to the reopened banks. Without dozens of cable shows and conspiratorial blogs telling them otherwise, millions of people complied and did just that, helping turn around the banking disaster. The following Monday deposits exceeded withdrawals.

With Democrats victorious in the 1932 elections, Congress synced with Roosevelt. Ferdinand Pecora, Chief Counsel to the Senate’s Committee on Banking & Currency, spearheaded a sweeping overhaul of American finance. The Banking Act and Glass-Steagall Act set up the FDIC, regulated bank loans for on-margin investing, and separated regular retail commercial banking from investment banks that took greater market risks. The nation then went over half a century with no significant bank failures but Congress repealed this last portion of Glass-Steagall in 1999, contributing to the Financial Crisis of 2007-08 (at least true of Citibank and Bank of America, if not the investment banks at the crisis’ heart). From 1929-33, the connection of regular retail banking to the market’s whims was crucial to the Great Depression, so it made sense to build a firewall between commercial and investment banks.

With the FDIC, the government backed customers’ bank accounts up to $2.5k (now $250k). The idea had been out there for fifty years, but bankers had always resisted out of fear they’d be left funding the FDIC instead of the government. In truth, neither do. The FDIC doesn’t actually have nearly enough money to pay everyone if all banks failed, but its existence means customers don’t panic and rush banks, so it doesn’t have to.

Most of these early actions took place in FDR’s first three months in office, the so-called First Hundred Days, though when FDR coined the famous phrase he was referring to the congressional, not executive, branch. Many subsequent presidents have hoped to have a productive “first hundred days,” but only the Depression’s severity and nearly unprecedented cooperation on Capitol Hill (Congress) allowed it to happen in the First New Deal. In 1933, Democrats dominated both houses of Congress and had FDR in the White House, allowing them to pass legislation virtually unopposed. At the White House, Roosevelt also fêted America’s most popular radio broadcaster, Walter Winchell, who transitioned from gossip and entertainment into an influential New Deal supporter. Winchell also ridiculed the German American Bund (Nazis), marginalizing Nazism and helping prevent it from gaining serious traction stateside (more next chapter). And, at first, Roosevelt had William Randolph Hearst in his corner, who controlled a huge swath of America’s newspapers, magazines, and radio stations.

To protect government gold from American gangsters and potential European armies, New Dealers moved most of it from East Coast banks to Fort Knox, a remodeled tank base in Kentucky. And they tackled organized crime by expanding a better-armed FBI and building federal penitentiaries like Alcatraz, aka “The Rock,” in San Francisco Bay. Gangsters had gotten ahead of law enforcement during Prohibition, but the National Firearms Act (1934) regulated machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, silencers, grenades, missiles, bombs, and poison gas. A huge factor in fighting crime was just repealing Prohibition, but the “G-Men” (FBI agents) stayed busy after 1933. Prohibition revealed how support for law and order can potentially conflict with an individual rights-based Second Amendment. Ultimately, effective law enforcement needs firepower superior to the general population.

The government kept some gold under New York’s regional Federal Reserve. They also recalled gold bullion from citizens, exchanging it for cash, then used the gold backing to print more money, devaluing the dollar and ending deflation while staying on the gold standard. But FDR gradually converted the gold-dollar standard from $20.67 to $35 per Troy Ounce in 1933-34, and the U.S. left the gold standard completely in 1971 (Optional Listen). The stock market rose 87% in the first three months after FDR loosened the gold standard.

It may seem strange for the government to want inflation but, as we saw in the previous chapter, recessions cause too much deflation, hurting debtors who owe money calculated at the former rates and delaying purchases and investments because consumers and companies think prices will keep dropping. For homeowners, the real (inflation-adjusted) amount of mortgages grows as the value of currency deflates. Eventually, wages too must drop to account for the lower prices companies are charging, inverting the price-wage spiral. Companies laid off workers as consumers waited for prices to drop even more before buying things. In normal times, the Dust Bowl drought on the Southern Plains would’ve increased crop prices if anything, but deflation was so severe that wheat fell by over two-thirds, in that case impacted by increasing supply in Europe and Russia. Countries worldwide experienced severe deflation during the Depression, dropping prices to the point that companies and farms couldn’t generate enough income to survive. Consequently, governments have preferred to foster mild inflation ever since and getting away from gold standards has allowed them to.

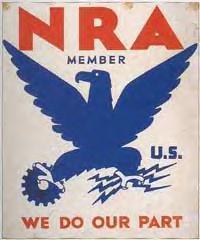

The First New Deal did nothing as radical as creating a safety net through Social Security or even alter the basic relationship of businesses and workers. Instead, it mostly requested the cooperation of industry in not cutting workers or lowering wages. In other cases, it demanded adherence to regulations. The First New Deal’s centerpiece was an unwieldy if well-intentioned bureaucracy called the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The NRA, formed by the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) and not to be confused with the National Rifle Association, at least offered up an example of federal action that many people rallied around. It was a pseudo-cooperative venture between government and business intended to patch up the worst economic problems without being too intrusive. The NRA was another example of continuity between the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations insofar as Hoover encouraged avoiding regulation and relying instead on “voluntarism” between government and business. The idea was to check “destructive competition” and get businesses within any one sector to voluntarily agree on propping up prices and wages and establishing codes of fair competition. Some consumers boycotted businesses that didn’t join and hang the sign in their window. Many businesses went along with its “blue eagle campaign,” but the natural instinct of any one company is self-preservation and most weren’t likely to try anything too altruistic if not compelled. They were obligated to themselves, their remaining employees, their shareholders (in the case of public companies), and even their customers, to do what they had to do to stay in business. Also, raising wages led companies to lay off workers, including thousands of African Americans.

There’s mixed evidence on the NRA’s impact. Conservatives claim it was detrimental, interfering with the natural competitive process and hindering recovery. Liberals point to a 55% boost in manufacturing between 1933 and ’35 and that over two million businesses signed on. In the process, the NRA informally helped to establish the minimum wage, 40-hour workweek, and abolition of child labor that later became legal mainstays of industrial America. These improvements bolstered unions, which is why the influential W.R. Hearst turned on FDR because of the NRA. Hearst had always championed the rights of workers and immigrants in his papers because that’s who he was marketing papers to, but his generosity didn’t extend to paying his own staff or newsboys good wages. Hearst saw the NRA as a communist threat to capitalism and swung so far right that he schmoozed with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and printed their translated editorials in his papers. This backfired because Hearst’s audience liked the New Deal, and subscriptions dropped off so much that his own corporate board demoted him. But Hearst’s sweeping charges of communism to describe anything he disagreed with on the left, including sending reporters to colleges to unmask communist professors, helped pave the way for McCarthyism during the early Cold War.

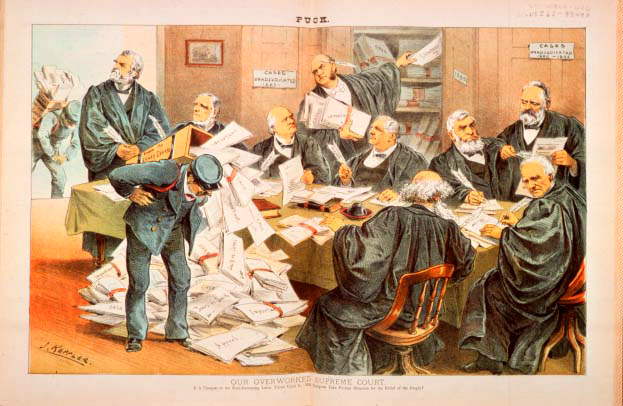

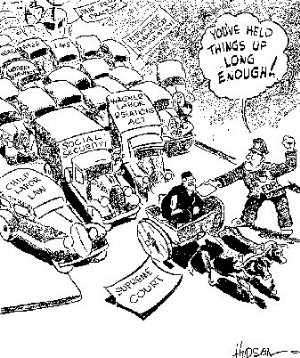

The Supreme Court shot the NRA down in 1935. If the NRA had been compulsory, it would’ve been a dramatic intrusion into the free market system, giving the government a major role in setting wages and prices. Yet, even with NRA membership being voluntary, the Court still ruled the agency unconstitutional.

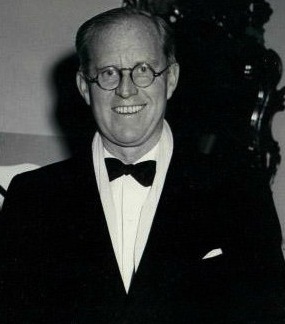

Consequently, the First New Deal had less long-term impact than the Second (below), but it expanded Hoover’s job creation programs, got the U.S. on a looser gold standard, shored up the banking system, spurred the stock market, and provided the public with some nutritional and psychological relief. Reforms regulating stock sales and creating the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1933-34 brought long-term stability to the stock market. Joseph Kennedy, Sr. engineered the reforms. Kennedy knew how corruption threatened markets because his own insider trading in the 1920s skirted the law and would be illegal today. Just as hacking into computers can earn you a job in cybersecurity today, FDR tapped Kennedy to clean up the stock market because his shady reputation qualified him, especially when combined with Kennedy’s genuine conversion to the notion that unregulated markets threatened the capitalist system. He loved capitalism and wanted to see it persevere over communism. Having a capitalist like Joe Kennedy on board helped FDR insulate the New Deal from right-wing criticism.

On the side, Kennedy also started a liquor importing business with James Franklin, FDR’s son, after the repeal of Prohibition, though he didn’t drink himself. He had other irons in the fire, running RKO Studios in Hollywood while helping to raise nine kids in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. As we’ll see in the next chapter, in the late 1930s Kennedy served as FDR’s ambassador to Britain. As we’ll see in Chapter 16, his second-eldest son John became president.

The early New Deal also provided some relief to farmers through the Agricultural Adjustment Act, at least those that were already somewhat efficient and well-capitalized. Like banks, they weeded out the weak. Some Dust Bowl farmers on the Southern Plains profited from government programs by being paid to improve cultivation techniques or grow nothing and let their land return to grassland. As odd as it may sound, given widespread hunger and malnutrition, the government paid farmers to destroy wheat, corn, and cotton and slaughtered livestock (including six million pigs) in mass graves to raise falling commodity prices. Mules trained to walk between rows had to be re-trained to stomp on crops. To be sure, that helped farmers by raising prices but still seems crazy given that some people were going hungry. The counter-argument was that people weren’t going hungry because of actual shortages, but rather because they couldn’t afford what was available. Cutting agricultural production also forced tenant farmers off the land. But the New Deal provided some relief to small, struggling farmers by establishing colonies with small farmhouses, chicken coops, seed, and tools on twenty acres. Country singer Johnny Cash lived on such a farm as a young boy outside Dyess, Arkansas, where he worked long hours in cotton fields before a 1937 flood destroyed the colony — the source of his 1959 hit “Five Feet High and Risin’.”

Race & the New Deal

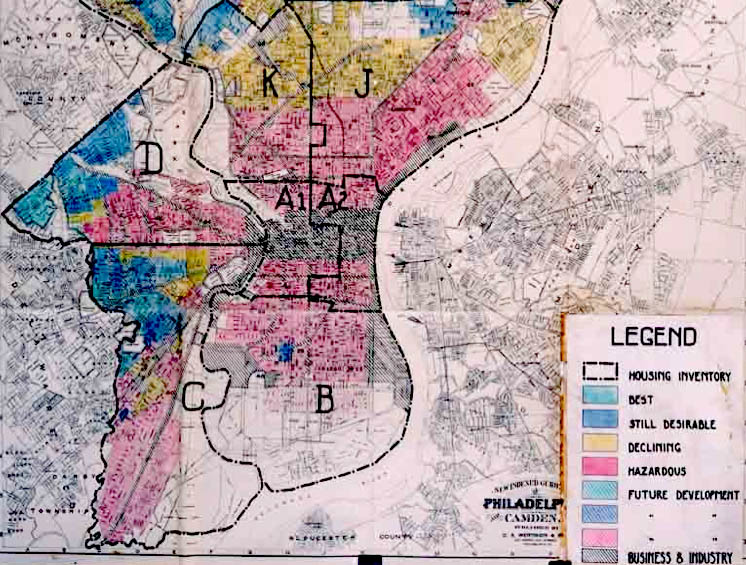

The New Deal excluded sharecroppers and tenant farmers from farming relief, though, perhaps to discriminate against minorities, and African Americans complained of discrimination by the forenamed NRA. The New Deal also denied domestic servants (often minorities) the right to collective bargaining while granting that same right to most unions. And as we’ll see in a section below, the Second New Deal’s housing policy discriminated by charging minorities higher interest rates. FDR maintained racial segregation in the Civil Service (agency employees, postal workers, etc.), as initiated by Woodrow Wilson. Also, early Social Security was at least incidentally racist, though another problem was that migrant workers, especially, were harder to track. The total number of Whites denied coverage was higher, but the proportion of minorities was higher (Social Security Administration): FDR’s administration made these decisions, not the Social Security Administration. Beyond the practical challenge of tracking mobile workers, why would FDR and Congress go out of their way to marginalize Blacks and Hispanics? To get Southern Democrats like Ellison “Cotton Ed” Smith of South Carolina and KKK-member Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi on board with the New Deal. Smith got his nickname by declaring that “cotton is king, and white is supreme” while Bilbo endorsed lynching Blacks who tried to vote.

FDR’s administration made these decisions, not the Social Security Administration. Beyond the practical challenge of tracking mobile workers, why would FDR and Congress go out of their way to marginalize Blacks and Hispanics? To get Southern Democrats like Ellison “Cotton Ed” Smith of South Carolina and KKK-member Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi on board with the New Deal. Smith got his nickname by declaring that “cotton is king, and white is supreme” while Bilbo endorsed lynching Blacks who tried to vote.

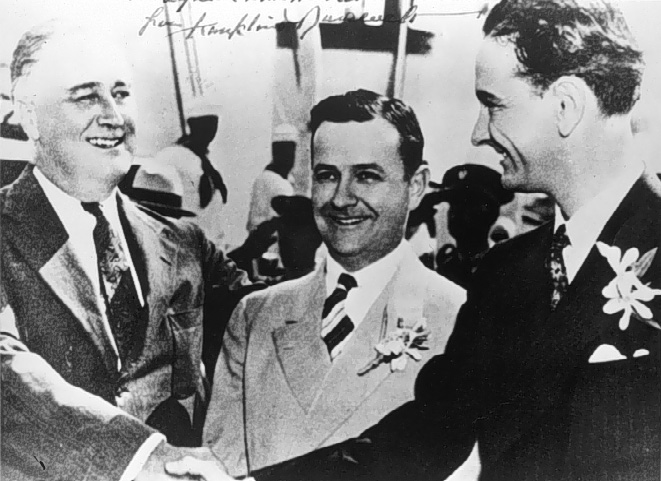

The key linchpins bridging the divide between FDR and Southern Democrats were Houston businessman Jesse Jones, who led the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and fellow Texan John Nance Garner (above), who served as FDR’s vice-president for two terms (1933-1941). As former Speaker of the House, “Cactus Jack” Garner could navigate Capitol Hill. While staunchly anti-union, Garner spearheaded the FDIC bank bill against FDR’s initial objections.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt with Tuskegee Airman Pilot C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson, 1941, Air Force Historical Research Agency

Keep in mind how divisive Democrats had been in the 1920s, torn between northern ethnic immigrants and rural, white Southerners. Roosevelt being a “party unifier” in the 1930s was code for civil rights would have to wait and minorities bore the worst brunt of the Depression. While there’s no “smoking gun” primary source evidence to support this conspiracy, the pattern is clear enough to make coincidence unlikely. Historian Ira Katznelson even argues that Southerners used the Great Depression to hijack American politics for another generation. Famous for its progressive gains, and rightfully credited for including more Blacks in the administration than any in history up until then, the New Deal was initially built on the foundation of Jim Crow. To keep Democrats united, FDR didn’t support a key anti-lynching bill. The NAACP called the new social safety net “a sieve with holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.” The New Deal was also indirectly racist insofar as it bolstered labor unions (more later), and unions often protected Whites and opposed immigration.

These New Deal flaws have led modern civil rights commentator Ta-Nehisi Coates to argue that modern liberalism is intrinsically racist, but many civil rights leaders have been leftists or liberals and even the New Deal helped minorities in important ways. It built low-cost housing, employed African Americans in the WPA and CCC (more below), and set up locally-run agencies in Puerto Rico to create jobs. There is no essential or lasting causal connection between liberal politics and racism. After all, the 1960s civil rights movement’s biggest gains happened during America’s most liberal phase: LBJ’s Great Society. In the 1930s, African Americans and Hispanics still did better than they had under Hoover because many New Deal programs covered all workers. Notably, the few Blacks who could vote migrated to the Democratic Party in the 1930s and, indeed, one of the New Deal’s biggest criticisms at the time was that it wasn’t racist enough.

But civil rights were not on the New Deal agenda despite the wishes of FDR’s wife, Eleanor (his 5th cousin), at least for the most part. But she successfully insisted that African Americans be included in the National Youth Administration (NYA) that focused on job creation for 16-25 year-olds. Eleanor, or ER, also worked tirelessly with the NAACP and the KKK once put a $25k bounty on her head. Anyone the KKK wanted to kill that badly is someone we should all take note of. Eleanor Roosevelt was the most political First Lady in American history and had earned her reputation advocating for the rights and good treatment of wounded Doughboys during WWI when she worked with the Red Cross. When WWII broke out, she defended the rights of African-American soldiers like the Tuskegee Airmen. By taking the lead on civil rights, ER served as a lightning rod for FDR, diverting attention onto herself so as to spare him the career-killing, coalition-busting, bad publicity of being an anti-racist.

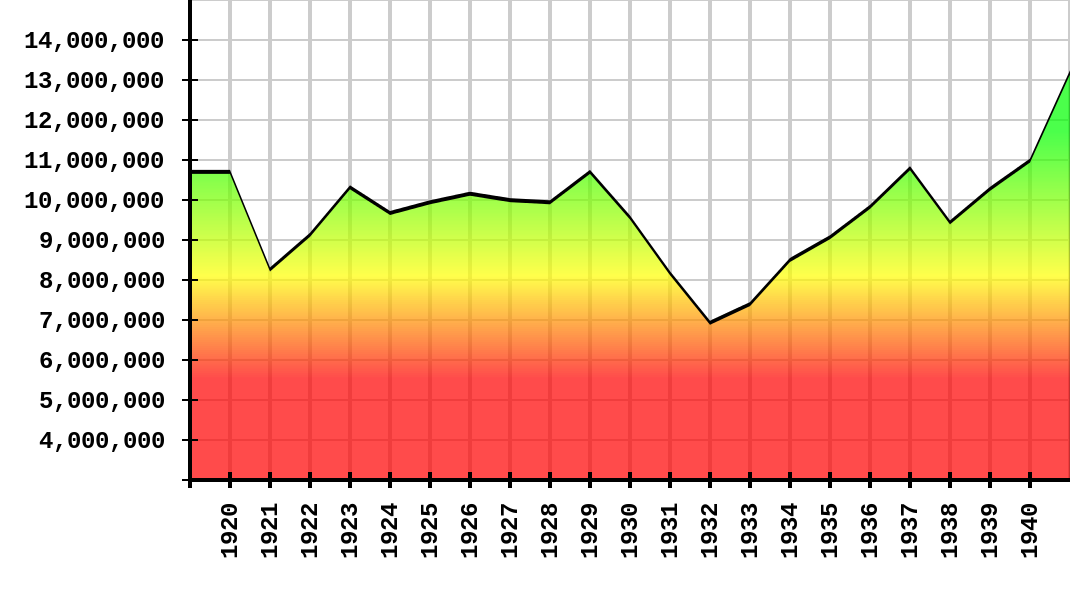

FDR couldn’t support civil rights without splitting the Democratic Party and that coalition still had big challenges in front of it. The Depression was bottoming out in 1933-34, or at least things weren’t getting worse. But neither was the economy rebounding toward anything like the 1920s boom years. Aside from reforming banking and Wall Street and feeding the hungry, the American economic engine still needed a spark.

Priming The Pump

Roosevelt wasn’t a social revolutionary, Antichrist or dictator, as some conservative critics charged, and neither was he a full-blown corporate stooge sellout as his leftist critics charged. Then, as now, Americans sometimes struggle to wrap their head around the notion that politicians they don’t agree with aren’t devils or gangplanks to left- or right-wing totalitarianism (according to the British Guardian, as of 2013 ~ 20% of Americans thought Barack Obama might be the Antichrist). Yet, as is always the case in times of crisis, people really were asking fundamental questions about the American system. Some leftists in Hollywood were imagining a more effective New Deal with Gabriel Over The White House (1933), but the fictional president only brings about the desired ends by sidestepping democracy. Capitalism wasn’t the only thing looking bad ca. 1933, in other words: democracy itself was on trial.

Democratic-Capitalism wasn’t where the world was headed. The leaders of real totalitarian governments in the 1930s were FDR’s contemporaries in Europe — Stalin (USSR), Hitler (Germany), Mussolini (Italy), and Franco (Spain) — and the last thing he wanted was to see America go down the same path. At the same time, Roosevelt thought that, if he failed to try anything constructive to revitalize the economy, the U.S. might go down with him and that called for some government intervention, at first moderate (First New Deal) then, by American standards, a bit more radical (Second New Deal).

FDR didn’t want to overturn capitalism, but rather to “trim the weeds and vines.” The Far Left, if not the Right, agreed with that assessment of FDR if not the prescription. The U.S. Communist Party (CPUSA) wrote in 1933: “The New Deal is a blow against the workers and increases profits for Wall Street. All of this was done as the capitalist way out of the crises.” Roosevelt wanted to save capitalism from itself by making some adjustments, just as his distant cousin Teddy had before him. In that way, Teddy’s Square Deal was similar to Franklin’s New Deal, even though Teddy was a Republican and Franklin a Democrat. In his 1932 nomination acceptance speech, FDR pledged a “new deal for the American people.” His administration’s name got help from a 1932 book entitled The New Deal by Stuart Chase, which led to a cover story in the New Republic the week of his inauguration.

Chase’s ideas were more radical than FDR’s New Deal, but the name was perfect branding for what Roosevelt wanted to do. His ideas were new, but the word deal represented more of an opportunity or a mutually agreed upon arrangement than a strict policy being imposed from above by an unyielding government. There would be no public ownership of corporations or 10-year plans as in communist countries. The New Plan wouldn’t have flown in the U.S., regardless of how bad the economy was. Deals, after all, are what make commerce tick and what practical, hard-working people wanted to do more of in the future than they were currently doing. Not all such names stick. No one remembers Bill Clinton’s New Covenant, George W. Bush’s Ownership Society, or Barack Obama’s New Foundation. In 2021, the Democrats should’ve sampled their Build Back Better name with a sample audience, and should revive their traditional donkey. New Dealers also branded their bank “holiday” better than Hoover’s “moratorium.”

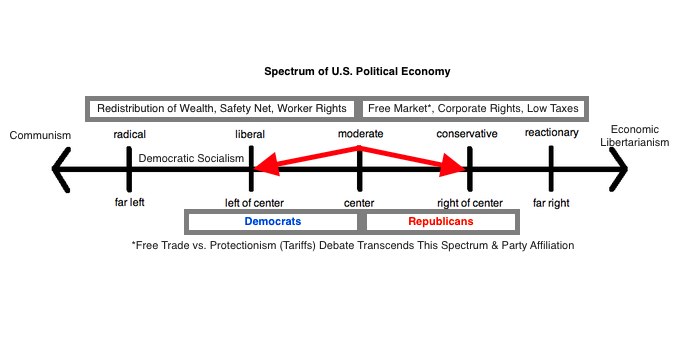

The New Deal technique for “priming the pump” of American capitalism drew on the counter-cyclical theories made famous a few years later by British economist John Maynard Keynes, who’d accurately predicted that the world economy would suffer from the Versailles Treaty indebting Germany. Keynesians, then and now (e.g., Paul Krugman), argue that governments should spend in recessions to stimulate economic growth and create jobs while not raising taxes or cutting programs, and then collect tax receipts at normal rates later to pay off the debt when the economy rebounds.

If such topics strike you as so dull that you’d rather have a root canal, take heart that previous victims have already nicknamed economics the “dismal science”, as opposed to the “sweet science” of boxing. Alas, it doesn’t follow that economics doesn’t impact our lives and here, as elsewhere, fun isn’t our primary goal. As a voting citizen, you should know that Keynes’ ghost will likely lurk in the shadows of nearly every economic debate you’ll ever hear. You can scarcely vote without taking a stand on Keynes, at least during downturns.

FDR was a moderate Keynesian insofar as, like Herbert Hoover, he wanted to use the government to create jobs, though he wasn’t keen at first on the deficit (debt) part of deficit spending and even reduced federal spending 10% his first year, but later he changed his mind. FDR wasn’t purely ideological in any particular direction, so much as he was willing to try anything and everything to get the economy moving. As mentioned, he was more of a pragmatic tinkerer. In Germany, on the other hand, Nazi economists embraced Keynesian economics more fully with around 4-5x as much spent per national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than the New Deal and succeeded more at first in turning their economy around. This strategy is sometimes called demand-side economics because the government, by increasing employment, is thereby increasing the demand for products and services (spending). Keynes pioneered macroeconomics by going past supply-and-demand to study the big picture and suggest ways to stimulate aggregate demand.

Another form of stimulus, employed by Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, is cutting taxes for the wealthy and corporations in the hope that more jobs will trickle down to the have-nots if money is in greater supply among the haves. This supply-side economics is also a Keynesian theory technically, even though it’s rarely thought of as such. Most advocates of tax cuts think they’re opposing Keynes, not realizing that he discussed tax cuts as another option to stimulate economies. Either approach is part of fiscal policy coming from Congress and the president as opposed to the monetary policy from the Federal Reserve with its elastic currency.

Both government spending (63% of Obama’s 2009-19 stimulus) and tax cuts (100% of Bush’s 2001 stimulus, 37% of Obama’s ’09) are forms of temporary government intervention to jump-start a stalled economy. Both ideas reject the notion that economies fix themselves naturally, or at least that doing nothing is the quickest way to revive an economy. Keynes just preferred the government spending option over tax cuts because it guaranteed money was put to work and not hoarded. In the tax cut option, though, no overhead is lost to government bureaucracy and advocates can hold out hope that the public forgets the temporary aspect and the cuts become permanent, as happened with the middle-class portion of the 2001 cuts before the new 2018 code.

In either case, spending or lower taxes, the government goes (further) into temporary debt in hopes of jump-starting the economic engine, at which point the debt can gradually be paid off. They are “priming the pump” the way one pushes the primer bulb on a lawnmower to get rid of excess air and fill the carburetor with the right amount of fuel. In this case, the fuel is money and the right amount is more of it — enough that consumers start spending. With the counter-cyclical option, the government goes into temporary debt by spending more; with the tax cut option, they go into temporary debt as revenues decrease initially, though the idea is that overall tax revenue will go up later anyway despite lower tax rates. Contrary to popular opinion, Keynes did not advocate long-term, structural debt, but rather short-term annual deficits that would be erased once the economy picked up and tax revenue increased. After the 2007-09 Financial Crisis and Great Recession, the U.S. was thus under the influence of two stimulus packages (Bush’s and Obama’s) that probably muted the crisis but ran the country further into debt, which all of us now contribute 17% of our taxes toward servicing.

While these theories may seem dry or abstract, it’s essential to learn about them because they’ve remained at the heart of our political debates ever since. For instance, the Obama ARRA Stimulus Package of 2009-19 was a combination of the two forenamed techniques, with 63% stimulus spending (on infrastructure, education, unemployment insurance, green energy) and 37% middle-class tax cuts (in the form of withholdings rather than rebate checks). The $831 billion ARRA package was widely criticized as being too small by Democrats and too large by Republicans. Though comparable to the New Deal in inflation-adjusted dollars, the country was much larger and the economy much bigger in 2009 than either was in 1933. For perspective, the Obama Stimulus was around 5.7% of GDP compared to 40% in the New Deal (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve).

While these theories may seem dry or abstract, it’s essential to learn about them because they’ve remained at the heart of our political debates ever since. For instance, the Obama ARRA Stimulus Package of 2009-19 was a combination of the two forenamed techniques, with 63% stimulus spending (on infrastructure, education, unemployment insurance, green energy) and 37% middle-class tax cuts (in the form of withholdings rather than rebate checks). The $831 billion ARRA package was widely criticized as being too small by Democrats and too large by Republicans. Though comparable to the New Deal in inflation-adjusted dollars, the country was much larger and the economy much bigger in 2009 than either was in 1933. For perspective, the Obama Stimulus was around 5.7% of GDP compared to 40% in the New Deal (Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve).

Is stimulus-oriented deficit spending merely a matter of “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” in this case robbing future taxpayers to pay current Americans? In other words, does it privilege the “seen” (jobs created) over the “unseen” (jobs lost to taxes and future debt)? It’s a fair question and a key theme for New Deal critics. But, according to the Keynesian school of thought, stimulus spending is worth it and provides a net gain because once the economy has turned around the government can well afford to pay off the debt, as its coffers will be filling up with more tax receipts after the lawnmower is up and running. For them, austerity or “tightening one’s belt” to avoid more short-term debt, as advocated by the Tea Party in the 2010s, might make sense in a household budget crisis but, nationwide, cutting spending during a recession is the worst possible time, roughly analogous if less extreme to putting a debtor in prison. Just as a debtor has no chance to repay his creditor if he’s in jail, we shouldn’t weaken the economy just as we’re trying to revive it. You could think of Congress cutting the budget during a recession as the equivalent of the Federal Reserve constricting cash at the wrong time, as they did in 1931-32. Believers in stimulus spending are putting weight on the idea that stimulus money jump-starts the economy, creating job growth that outweighs the down payment spent on the stimulus package. In a 1938 Fireside Chat, FDR said that most New Deal recovery was in the private sector, as intended, but that public spending had triggered private growth.

If the liberal spending approach seems spurious, remember that its conservative skeptics argue the same thing regarding the benefits of tax cuts. In each case, the government’s balance books temporarily get worse and, in each case, a dollar spent theoretically leads to three or four more dollars down the road in a multiplier effect. Think about that; if both sides are right, all we need to do is spend like liberals and cut taxes like conservatives and we’ll all have four times as much money down the road. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is currently biased toward the liberal view because it takes spending multipliers into account, but not tax cut multipliers. In either case, supporters of the 2009-19 package and many mainstream economists think the stimulus helped stave off a worsening recession and unemployment in the short run.

In Texas, Governor Perry initially turned down stimulus money in 2009 to oppose the principle of federal spending, but then asked for it in 2010 to cover $6.4 billion of the state’s $6.6 billion budget shortfall. That allowed Texas to preserve its $9.1 billion Rainy Day Fund and Perry to make his case that his state balances its budget better than the national government when he ran for president in 2012.

For conservative economists, Keynesian spending is not worth it. There’s “no free lunch” and the theory makes no more sense than saying that someone stimulates the economy by stealing from your bank and then spending the stolen money at the shopping mall. Yes, it stimulates business at the mall, but no more than would’ve been spent by those that had their money stolen; it’s simply a break-even diversion of funds, robbing Peter to pay Paul. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill supported some taxation as a price of civilization, but also said that “for a nation to try to tax itself into prosperity is like a man standing in a bucket and trying to lift himself up by the handle.” These critics obviously aren’t buying the theory’s jump-start portion. Keynes’ counterpart Friedrich Hayek believed that governments should balance their budgets and interfere as little as possible with the natural capitalist process of creative destruction. The Austrian economist argued against wealth re-distribution most famously in The Road to Serfdom (1944). For Hayek and American conservatives like Milton Friedman, stimulus spending is counter-productive hogwash, though Friedman endorsed the tax-cut version of stimuli.

But Friedman thought the government at least had a role via the Federal Reserve. His theory of increasing the money supply during recessions meant not only that the Fed should ensure that more money is in circulation — which they famously failed to do in the early 1930s because of their concern with staying on the gold standard — but also that consumers and companies should have a greater supply of money in hand by virtue of lower taxes. In his book Capitalism & Freedom (1962), Friedman laid out the limited-government supply-side economic theory that went mainstream in the 1980s under Ronald Reagan. As mentioned, conservative economists believe that tax cuts can even counter-intuitively increase government revenue because they stimulate the economy so much through the multiplier effect that more total tax money flows to the government even if the rates are lower. A theoretical “sweet spot” of optimum tax rates is known as the Laffer Curve (Laffer himself was a conservative arguing for lower taxes).

But Friedman thought the government at least had a role via the Federal Reserve. His theory of increasing the money supply during recessions meant not only that the Fed should ensure that more money is in circulation — which they famously failed to do in the early 1930s because of their concern with staying on the gold standard — but also that consumers and companies should have a greater supply of money in hand by virtue of lower taxes. In his book Capitalism & Freedom (1962), Friedman laid out the limited-government supply-side economic theory that went mainstream in the 1980s under Ronald Reagan. As mentioned, conservative economists believe that tax cuts can even counter-intuitively increase government revenue because they stimulate the economy so much through the multiplier effect that more total tax money flows to the government even if the rates are lower. A theoretical “sweet spot” of optimum tax rates is known as the Laffer Curve (Laffer himself was a conservative arguing for lower taxes).

We can’t measure these ideas in a controlled environment, only in all the moving parts of the real economy as it’s pushed and pulled by multiple factors. Also, while presidents take the lead in suggesting tax policy, Congress sets the rates: tax bills originate in the House and are approved by the Senate. John Kennedy’s tax cut jump-started the economy enough to increase overall tax revenues in the early 1960s, or at the very least coincided with the upturn. Between 2001 and 2008, George W. Bush’s tax cut raised revenue totals by 4% (adjusted for inflation), but revenues fell 13% in relation to overall GDP (Punditfact). At the state level in the 2010s, Kansas Governor Sam Brownback’s (R) tax cut didn’t work its multiplier magic, instead threatening the state’s budget.

As of 2020, Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cuts helped the economy but hadn’t increased tax revenue, instead adding to the debt, but it was too soon to judge their long-term impact before the budget ballooned because of the COVID-19 outbreak that spiked unemployment benefits suddenly, cut tax revenue, and included a whopping $2.2 trillion CARES Act stimulus and relief, with another half-trillion-dollar package on its heels. The CARES Act is more than double the size of the entire New Deal, even adjusted for inflation, but, here again, smaller in relation to overall GDP. The same goes with Joe Biden’s infrastructure bill, despite it being, in turn, trumpeted as big by its proponents or criticized as too big by its detractors. Biden’s bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) boosted $650 billion already allocated over five years to $1.2 trillion, with the extra $550 billion earmarked for roads/bridges/dams, rail (freight and passenger), grid upgrades, clean water, and broadband for rural areas. Today, Democrats and Republicans alike are Keynesians, just as they were as far back as the 1965 TIME cover on the right, while some modern economists doubt the capacity of the government to impact output much with either the Democrats’ demand-side or Republicans’ supply-side stimuli.

As of 2020, Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cuts helped the economy but hadn’t increased tax revenue, instead adding to the debt, but it was too soon to judge their long-term impact before the budget ballooned because of the COVID-19 outbreak that spiked unemployment benefits suddenly, cut tax revenue, and included a whopping $2.2 trillion CARES Act stimulus and relief, with another half-trillion-dollar package on its heels. The CARES Act is more than double the size of the entire New Deal, even adjusted for inflation, but, here again, smaller in relation to overall GDP. The same goes with Joe Biden’s infrastructure bill, despite it being, in turn, trumpeted as big by its proponents or criticized as too big by its detractors. Biden’s bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021) boosted $650 billion already allocated over five years to $1.2 trillion, with the extra $550 billion earmarked for roads/bridges/dams, rail (freight and passenger), grid upgrades, clean water, and broadband for rural areas. Today, Democrats and Republicans alike are Keynesians, just as they were as far back as the 1965 TIME cover on the right, while some modern economists doubt the capacity of the government to impact output much with either the Democrats’ demand-side or Republicans’ supply-side stimuli.

Grab A Shovel

FDR threw in with Keynes, just as Democrats and Republicans alike did in 2007-09 when the pressure was on and the economy was verging on collapse. It’s very difficult for elected leaders to tell citizens that they’re going to do nothing about an economic collapse, regardless of whether conservatives like Hayek and Friedman are right. With the economy on the verge of collapse in 2008, George W. Bush (R) said, “If this is Hoover (R) or Roosevelt (D), I’m damn sure going to be Roosevelt.” Government spending is something you critique from a comfortable perch, not when you’re hungry or unemployed or a politician trying to lure voters who are hungry or unemployed.

In a 1936 campaign speech at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh (left), FDR described why, to put food on people’s tables, he abandoned the balanced budget philosophy he brought with him to the White House: “To balance our budget in 1933, ’34 or ’35 would have been a crime against the American people. To do so we should either have had to make a capital levy [tax] that would have been confiscatory, or we should have had to set our face against human suffering with callous indifference…we accepted the final responsibility of government, after all else had failed, to spend money when no one else had money left to spend.” That same year, after being nominated to run for re-election, FDR gave his “Rendezvous With Destiny” speech at Franklin Field in Philadelphia, where he tried to shield himself from charges of socialism by instead depicting the wealthiest capitalists as “royalists” who were denying Americans basic freedoms in the same way British aristocrats had in the 18th century. It was a stretch, but he got his point across. As for the imperfections of the New Deal: “Better the occasional faults of a government that lives in a spirit of charity than the consistent omissions of a government frozen in the ice of its own indifference.”

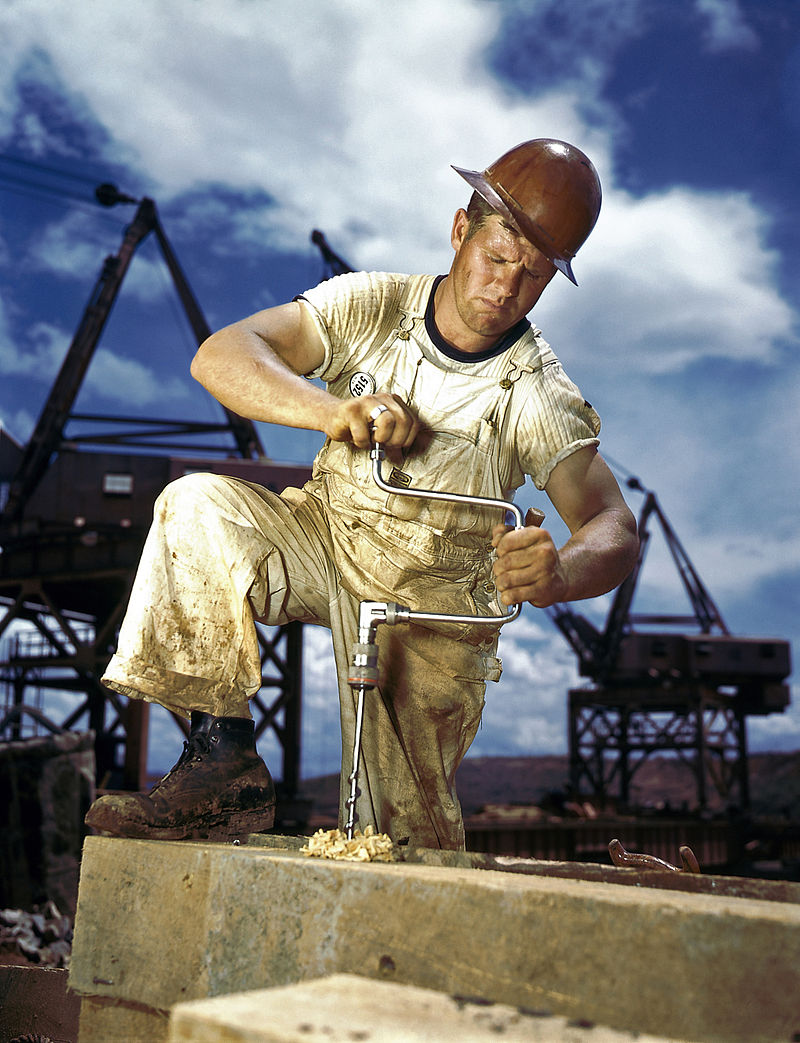

The New Deal provided some direct relief, but mostly it focused on creating jobs through a cavalcade of government-sponsored programs that put people to work. This is what Hoover started late in his term and would’ve liked to have done even more of had Congress cooperated. These programs straddled the First and Second New Deal and were known by a variety of acronyms, sometimes called alphabet soup, but their gist was the same: if there are no jobs, the government by God should make one up. It’s better than a handout. There is always work to be done in the form of construction, road building, clearing trails through national forests, fighting forest fires, etc. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was the biggest of these programs and oversaw smaller divisions. Not everyone grabbed an actual shovel; they even paid artists to paint murals (Public Works of Art Project), historians to interview 23 surviving ex-slaves (WPA Slave Narrative Collection), and photographers to document the times (e.g., Dorothea Lange for the Farm Security Administration). The WPA’s Federal Theater Project aimed to keep actors and writers employed. Eighty years before Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton (2015), the government funded Orson Welles’ “Voodoo Macbeth” (1936) with an all-black cast playing Shakespeare’s characters and the story set in Haiti.

Most hirees were laborers, though. A perfect example was the San Antonio River Walk. It didn’t have to be built, but it didn’t need to not be built either, so why not put people to work? In fact, this WPA project ended up boosting the city’s economy for years to come by attracting tourist dollars — a positive multiplier effect case study, with the initial cost no doubt paying for itself many times over. Like the Hoover Dam in the previous chapter, the River Walk had a head start before the Depression and, like Houston’s Ship Channel from Chapter 5, it tapped some private funds. But most of it was built with WPA money.

Encouraged by Austin’s pro-New Deal mayor Tom Miller, the WPA funded the University of Texas Tower (1937) and built much of Camp Mabry in west Austin. The city and Public Works Administration (PWA) jointly funded his namesake Miller Dam that generates electricity and helps control flooding on the Colorado River. Austin tapped New Deal funds to expand on an existing dam and sidewalks to build Barton Springs Pool. United States Representative Lyndon Johnson commandeered money for the country’s first federal housing projects, built for Austin’s Hispanic community in 1939. New Dealers built Longhorn Cavern State Park at Marble Falls and Buchanan Dam on the Colorado. Congress authorized Canyon [Lake] Dam in FDR’s last year, 1945. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built Texas state parks in Bastrop, Garner, Davis Mountains, Palo Duro Canyon, and Balmorhea and the trails along Austin’s Shoal Creek. Sometimes, crews used hand tools instead of power to ensure that the work would remain steady.

Nationwide, other crews built tunnels, bridges, airports, fire towers, waterfronts, post offices, city halls, playgrounds, fairgrounds, zoos, parks, fountains, museums, community centers, swimming pools, gyms, and sports stadiums around the country. The Civil Works Administration put four million to work in the winter of 1934 on projects like building the telephone lines and roads across Death Valley and cutting most of the Appalachian Trail. CCC workers planted an astonishing three billion trees and transitioned easily into the military after Pearl Harbor in 1941 because they were used to the work, regimentation, and low pay. Some of its workers were WWI veterans. The CCC worked in tandem with the Army (for its base camps) and Departments of Labor and Agriculture.

As chronicled by historian Douglas Brinkley in Rightful Heritage (2016), Franklin Roosevelt is underrated in comparison to his cousin Teddy when it comes to conservation. Brinkley knows both, having written the definitive account of Teddy’s conservation work in The Wilderness Warrior (2009). Not only did many state parks originate during the New Deal, but FDR also designated many areas that became national parks, including the Everglades, Joshua Tree, Big Bend, and the Smoky Mountains. The Department of Fish & Wildlife (1940- ) is also a New Deal product.

Both the right and left were skeptical of such agencies. Right-wing CCC critics likened it to Soviet-style socialism. They thought the worst workers ended up on the public crews and said the Works Progress Administration (WPA) really stood for “walk, piss and argue” or “we poke along.” It didn’t help to have jazz great Louis Armstrong sing: “Sleep while you work, rest while you play, lean on your shovel to pass the time away, at the WPA.” Some jobs were contrived or silly, created merely just to put people to work. According to legend, some people were paid to chase around tumbleweed on windy days. For the left, the work crews’ low wages hurt unions’ bargaining power. But New Deal “workfare” (as opposed to welfare) provided work for families in need and created lasting infrastructure.

Led by Harry Hopkins, the WPA started projects on the Southern Plains, for instance, in the heart of the drought-ravaged Dust Bowl. WPA crews paved much of Route 66, connecting Chicago to Los Angeles. Though derided as inefficient “boondoggles,” WPA projects built 75k bridges, 20k miles of water mains, 3k sports stadiums, over 12k playgrounds, and 116k buildings. The WPA built Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, Timberline Lodge at Mt. Hood (above), and Midway (Chicago) and LaGuardia (Queens) airports, all still in use. This Living New Deal map, with over 11k sites, documents the magnitude of achievement for agencies like the WPA and CCC — or waste depending on one’s political perspective. In either case, these crews were obviously doing more than just “poking along” or chasing tumbleweed.

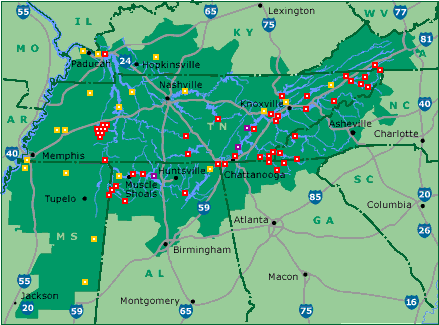

A struggling shoe salesman named Jack Reagan took a job as a federal relief administrator in Dixon, Illinois. It wasn’t the customary “pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps” all-American way to make a living, but it pulled the family through tough times. His son, Ronald, later opposed such government intervention as president in the 1980s, but he maintained his appreciation for the WPA. Ronald Reagan was less appreciative of the Tennessee Valley Authority public utility in the Southeast, which became a symbol of overbearing, technocratic government authority among conservatives, especially when it served as a failed model for modernization in developing areas like Vietnam (Mekong Delta) from the 1950s to ’70s. Reagan lost his job as spokesman for General Electric for criticizing the TVA.

TVA Worker on Douglas Dam in East Tennessee, 1942, Photo by Alfred T. Palmer, Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection,

The TVA built a series of hydro dams on the Tennessee River that, aside from employing many people and controlling flooding, brought power to the region, helping it to industrialize and create more jobs (map). Roosevelt was intent on bringing the southern economy into the 20th century. The TVA did just that but also damaged the environment and displaced people whose property was flooded. And, the public utility was another positive example of a multiplier effect. Today, much of the American auto industry has migrated from Detroit to the Tennessee Valley because of its cheap electrical rates. The TVA also powered Oak Ridge laboratory that helped build the atomic bomb during WWII, the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama that helped land men on the Moon, and even the famous Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Sheffield, Alabama that recorded numerous artists. One alt-country band, the Drive-By Truckers, had two songs about the TVA, one positive and one critical, symbolizing the conflicted feelings Southerners still feel for the organization.

The TVA led to the Rural Electrification Act (1935) that aimed to juice other un-electrified regions and erect telephone lines. Starting nearly from scratch, the REA brought electricity to 96% of farmers and phones to 65% within twenty years. Many REA-funded rural electrical co-ops are still in existence today and are adopting wind and solar energy for farmers. The Bureau of Reclamation took over construction of the Shasta Dam (1938-45) that tapped the Sacramento River for power and brought irrigation to California’s Central Valley. In the Northwest, New Dealers built a similar series of hydroelectric dams along the Columbia River, helping to irrigate and power an otherwise arid region in central and eastern Washington and Oregon. First dreamt of in the 19th century, then seriously considered by the Army Corps of Engineers and Bureau of Reclamation in the 1920s, the Grand Coulee Dam in central Washington was a centerpiece of FDR’s New Deal during its construction from 1933-41.

Desperate for shovel-ready projects to put people to work, Roosevelt also wanted to combat western drought by “making the desert bloom.” This “biggest project on earth,” the largest power-producing facility in the U.S., was controversial from the start — opposed by eastern GOP congressmen who questioned spending so much money in the middle of nowhere and Wall Street plutocrats who didn’t like seeing utilities come under public control. It riveted the public’s attention but Grand Coulee’s critics seemed right that it was a colossal boondoggle. There were engineering setbacks and altering the river devastated the Colville Reservation’s twelve tribes, who relied on the Columbia River for salmon. While salmon could climb ladders alongside smaller dams (e.g., the Bonneville Dam in the Columbia Gorge), they couldn’t get around the Grand Coulee, which had enough concrete to pave a highway back and forth across the country. Emblematic of the New Deal, the dam was strong on job growth and weak on civil rights and environmentalism. Moreover, seventy workers died being impaled on rebar, drowned in the Columbia, or torn up in conveyor belts.

But Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor came along just in time to vindicate FDR, coinciding with the dam’s opening. The Grand Coulee Dam not only successfully irrigated the interior, it fueled industry in Seattle and Portland during WWII, powering aluminum factories and production at Boeing and Kaiser Shipyards. Today, there are nine more dams on the Columbia and Grand Coulee alone provides enough clean energy to power Seattle.

Franklin Roosevelt Shakes Hands with Young Lyndon Baines Johnson, Galveston, Texas, 1937, FDR Library

Combined local and federal funds from the Metropolitan Water District of California and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation built the Colorado River Aqueduct connecting the Colorado River at Parker Dam (Lake Havasu) to greater Los Angeles. San Francisco got its water, meanwhile, from O’Shaughnessy Dam at Hetch Hetchy Valley in the Sierra Nevada range. Around Austin, the Lower Colorado River Authority was the local version of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The LCRA provides water, flood management, electricity (mainly hydroelectric), and parks around the Highland Lakes and Colorado River. The LCRA was an example of state-sponsored New Deal-type legislation, as opposed to that coming from the national bureaucracy. Austin got a lot of federal dollars, too, as 10th District Congressman Lyndon Johnson steered funds toward municipal projects. We’ll hear much more from the ambitious Texan when he becomes president in 1963 (Chapter 16).

Challengers Right & Left

Whether the New Deal was too far to the left or too far to the right depended on the observer’s perspective. Like any president, Roosevelt had his critics on both sides. America’s first radio shock jock, Father Charles Coughlin of Detroit, managed to be on the right and left simultaneously, lambasting the New Deal “socialist” cabinet as “Christ-killing Jews” while also imploring FDR to nationalize the banks. If he disliked socialism so much, why did he favor government taking over the banks? Coughlin called on his viewers to form a new Christian Front party to support Nazism before radio stations cancelled him. When radio stations or today’s social media silence voices, it’s not a violation of the First Amendment because that applies against the government not private sector. Whether private platforms should enable free speech or censorship is another matter that we don’t have time to unpack here.

On the true left, Jungle author Upton Sinclair ran for governor of California as a Democratic Socialist, fronting his End Poverty In California (EPIC) movement. FDR refused to endorse him and tried to convince him to drop out of the race. When that failed, despite the inconvenience of his paralysis, he boarded a train for the West Coast to campaign on behalf of Republican gubernatorial candidate Frank Merriam. That act alone says a lot about where FDR actually stood on the political spectrum. He preferred having a Republican governor of a big state rather than seeing someone take any more radical measures than his “trimming of the weeds and vines” of capitalism. Sinclair lost the three-horse race to Merriam and another centrist candidate. Meanwhile, another Californian, retired farmer and physician Francis Townsend, advocated a $200/month public pension system for retirees over sixty. FDR disliked the idea, thinking it verged on communism, but it was the basis for the Social Security system that he reluctantly went along with in 1935. A key difference is that under Social Security each worker funds the system directly as they go with paycheck deductions. In Revolutionary America, populist Herman Husband suggested a similar idea, but he was so far ahead of his time that he had no influence on what happened 150 years later.

Louisiana Governor Huey “the Kingfish” Long was FDR’s most notorious leftist critic and a potential rival for the presidency. His Share Our Wealth program diverted oil company profits to building roads, bridges, charity hospitals, and schools in that mostly impoverished state. Long understood that it all had to do with how you frame your message. He never went so far as to use the words socialism or communism, which would have torpedoed Share Our Wealth in an instant. He simply asked the poor majorities if they thought the time had come to redistribute some oil wealth, couching his policies in Christian themes. He mocked the moderate FDR for still being on his mother’s allowance. If Long hadn’t been assassinated in 1935, he may have challenged Roosevelt in the 1936 presidential race. Instead, FDR raised taxes on the wealthy to “steal [Long’s] thunder.” Today, it’s still the case that initiatives like public health insurance and green infrastructure poll far higher among voters, including Republicans, when words like socialism aren’t attached, which is why their opponents do all they can to attach them.

Teamsters Strike, Minneapolis, 1934. Strikers Beat Two Policeman To Death And Police Shot To Death Two Strikers.

This is a good time for a break, as this is a hefty chapter. Re-charge your battery and return when ready.

Second New Deal: Retirement Pension & Unemployment Insurance

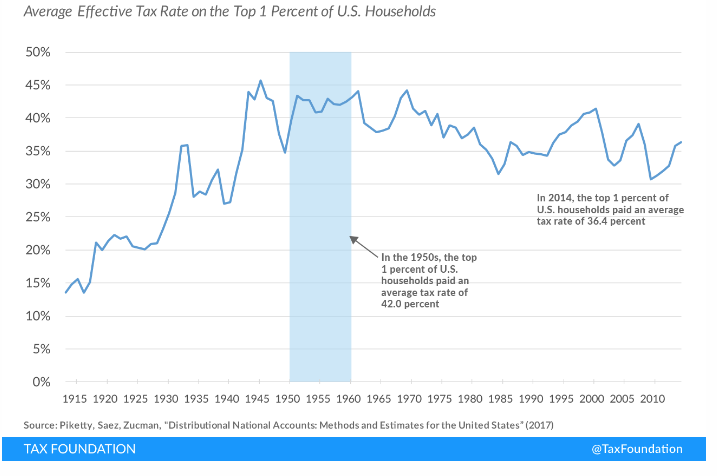

With critics like Long and Sinclair gaining popularity, and left-leaning Democrats winning in the 1934 midterm elections, Roosevelt abandoned his earlier polite requests to industry for cooperation (Hoover’s volunteerism) and sided unequivocally with labor. Playing the divisive politics card for the first time since he came into office, he now said of the wealthy, “I welcome their hatred…they’ll meet their master.” Whereas early New Deal funding had relied on traditional excise or sales taxes — the latter of which are arguably regressive (or, at least, not progressive) because everyone pays the same rate at point of purchase and the working poor spend disproportionally on staple items — 1935 Revenue Act raised income taxes on the rich to 75% for the top bracket, the portion over $1 million per year. And, in 1937, Congress passed another progressive law to crack down on tax evasion of the sort that disproportionally benefits the wealthy.

Franklin & Eleanor Roosevelt Whilst Courting, Campobello Island, New Brunswick, Canada, 1904, FDR Library

The hatred-master remark was strong words coming from a guy like FDR. Don’t get me wrong. You don’t run three+ presidential administrations from a wheelchair through a depression and world war without being tough as nails. But Roosevelt was an aristocrat just the same and Huey Long was right that he was still on his mother’s allowance. The van Rosenvelts were old money aristocracy dating back to the original 17th-century Dutch settlers in the Hudson River Valley (FDR also claimed to be a distant relative of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Douglas MacArthur, Winston Churchill, Queen Elizabeth I, and King Robert III of Scotland). By the mid-1930s, though, FDR’s sense of noblesse oblige (obligation of the nobility) surfaced in dramatic fashion, moving the needle of America’s political spectrum to the left.

The Second New Deal featured more lasting measures than the First, including Social Security, the right to collective bargaining for unions, minimum wage, and federal housing assistance. The first two were backed by a key member of FDR’s brain trust, New York Senator Robert Wagner, and all four changed subsequent American history. Social Security formed the basis of a new government “contract” unknown from 1776-1935. By now, the Teddy Roosevelt portion of the family (more conservative than their patriarch) had long since abandoned support for their “socialist” relative, as had the wealthy men Franklin went to private schools and Harvard with. But Roosevelt won over working-class America, forging the Democrats a solid nationwide coalition. One southern millworker captured the essence, calling him “the first president ever who understands my boss is a sonovabitch.” He won a landslide reelection in 1936 with every state but Maine and Vermont. If FDR was still only “trimming capitalism’s vines,” he was now revving the throttle on his string trimmer.

Though privately Roosevelt didn’t feel right about Social Security (presumably his mom’s allowance covered him), he was willing to agree if it was funded directly out of payrolls instead of its general fund, thus guaranteeing its solvency and giving all workers a stake in its survival. At first, Social Security provided a modest retirement pension and short-term unemployment insurance. Unemployment insurance was mostly administered at the state level, which turned into a mess in the 21st century when some states didn’t pay out, especially Florida, whose governor Rick Scott (R) made the paperwork so onerous that almost no one got relief until Congress picked up the slack with stimulus packages. Once he bought into Social Security, FDR played the religion card like any savvy American politician. On his “Sunday Sermon” fireside chat, he said that Protestants, Catholics, and Jews alike condemned the “unbrotherly [and uneven]….distribution of wealth.” Arguing that Social Security was the “Christian thing to do,” FDR decried the “spirit of Mammon [greed or wealth]” that had crowded out morality. Politicians and activists have used Christianity on both sides of nearly every major debate in American history and this was no exception. Critics, on cue, tied the collective nature of the New Deal’s retirement safety net to the Soviet Union’s godless communism.

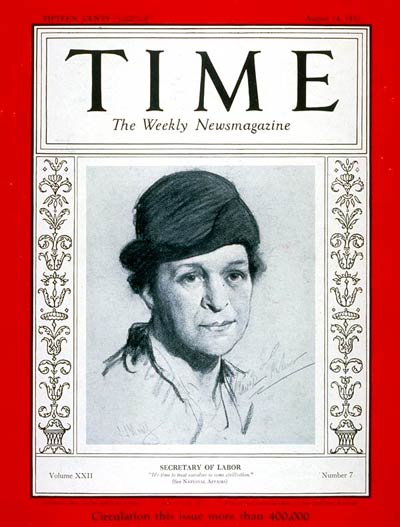

Social Security became law in 1935 with dependents added in 1939, COLA’s in 1950, and disability insurance in 1954. COLA’s are cost-of-living adjustments for inflation, not free Cokes®. Economists referred to Social Security as one leg in a “three-legged [retirement] stool,” supplemented by employer pensions and personal savings/investments. When the Depression hit, the U.S. was the only industrialized country in the world that didn’t already have some safety net for the poor and unemployed. A few states had meager systems and, as we saw above, Dr. Townsend envisioned such a system in California. While Senator Wagner provided important backing, the main architect of Social Security was Frances Perkins, who had made her name on New York’s Safety Commission after the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (Chapter 5). As Secretary of Labor, Perkins (right) contributed to many aspects of the New Deal and helped win labor’s support of FDR. If Perkins was the architect, the engineer of Social Security was Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Faced with the monumental task of tracking workers, early Social Security denied benefits to itinerant workers, servants, seamen, etc. and public employees who already had pensions. The result was at least incidentally racist insofar as 27% of Whites lacked coverage while ~ 66% of minorities weren’t paying in or receiving benefits. They fixed those problems in 1955, a decade before a lot of more famous civil rights legislation, which was both just and helped secure the transition of most minorities to the Democratic Party.

Social Security became law in 1935 with dependents added in 1939, COLA’s in 1950, and disability insurance in 1954. COLA’s are cost-of-living adjustments for inflation, not free Cokes®. Economists referred to Social Security as one leg in a “three-legged [retirement] stool,” supplemented by employer pensions and personal savings/investments. When the Depression hit, the U.S. was the only industrialized country in the world that didn’t already have some safety net for the poor and unemployed. A few states had meager systems and, as we saw above, Dr. Townsend envisioned such a system in California. While Senator Wagner provided important backing, the main architect of Social Security was Frances Perkins, who had made her name on New York’s Safety Commission after the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (Chapter 5). As Secretary of Labor, Perkins (right) contributed to many aspects of the New Deal and helped win labor’s support of FDR. If Perkins was the architect, the engineer of Social Security was Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr. Faced with the monumental task of tracking workers, early Social Security denied benefits to itinerant workers, servants, seamen, etc. and public employees who already had pensions. The result was at least incidentally racist insofar as 27% of Whites lacked coverage while ~ 66% of minorities weren’t paying in or receiving benefits. They fixed those problems in 1955, a decade before a lot of more famous civil rights legislation, which was both just and helped secure the transition of most minorities to the Democratic Party.

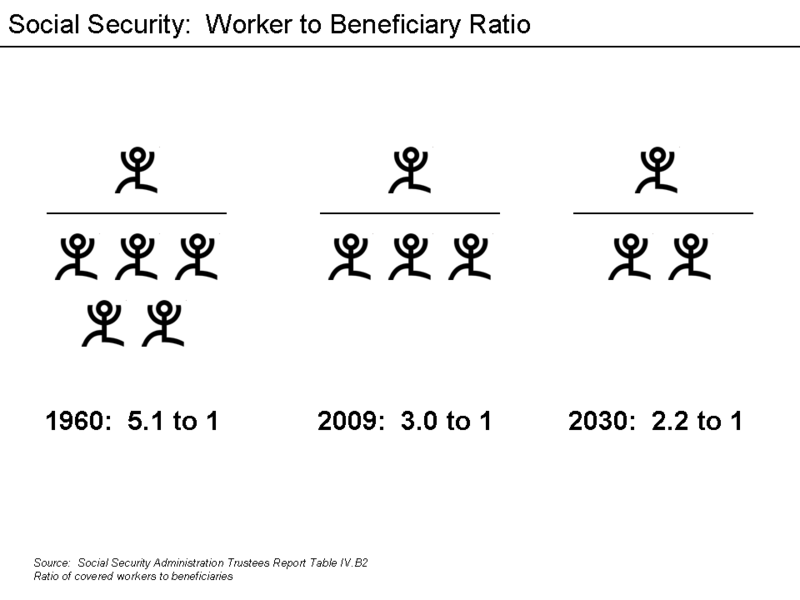

While Social Security has worked well so far and remains popular among most citizens, demographic projections show it will no longer operate in the black by the 2030s (or sooner, depending on COVID-19’s impact). At that point, the trust fund wouldn’t run out, but to remain solvent (in the black, not the red) recipients would have to take a 25% or so cut in benefits. The only way to avoid that (extrapolating current trends, which is never entirely accurate) would be for workers to accept a 2.5% increase in their paycheck’s payroll tax portion. The problem is that with Baby Boomers retiring and living longer than their parents’ generation, the ratio of retirees to workers paying into the system will grow to ~ 1:2 based on current projections.

That’s why critics of Social Security such as former Texas governor Rick Perry called it a Ponzi scheme. Real Ponzis aren’t transparent and are devious schemes to steal money, neither of which apply to Social Security. But it’s nonetheless true that Americans will eventually need to either reduce benefits, raise taxes, or increase the age at which benefits kick in. Even the full benefits were originally intended as a supplement rather than something retirees could solely survive on. Moreover, the act was passed when workers retired at 65 and life expectancy was around 67 (life expectancy at birth in 1930 was 58 for men, 62 for women, SSA). With people living longer now the eligibility age will have to be raised. A bipartisan act passed in 1983 kicked in a gradual increase from age 65 to 67 so that people born after 1958 will get full benefits at 67. You can choose to start collecting a smaller share at 62 instead, but that means you don’t get the full share later. There’s a common misconception that undocumented immigrants are benefitting from Social Security without contributing but, if anything, the opposite is true: they pay in with fake SS#s or ITINs but can’t receive benefits because they have no real number. Immigration, in general, benefits Social Security by creating more young workers paying in.

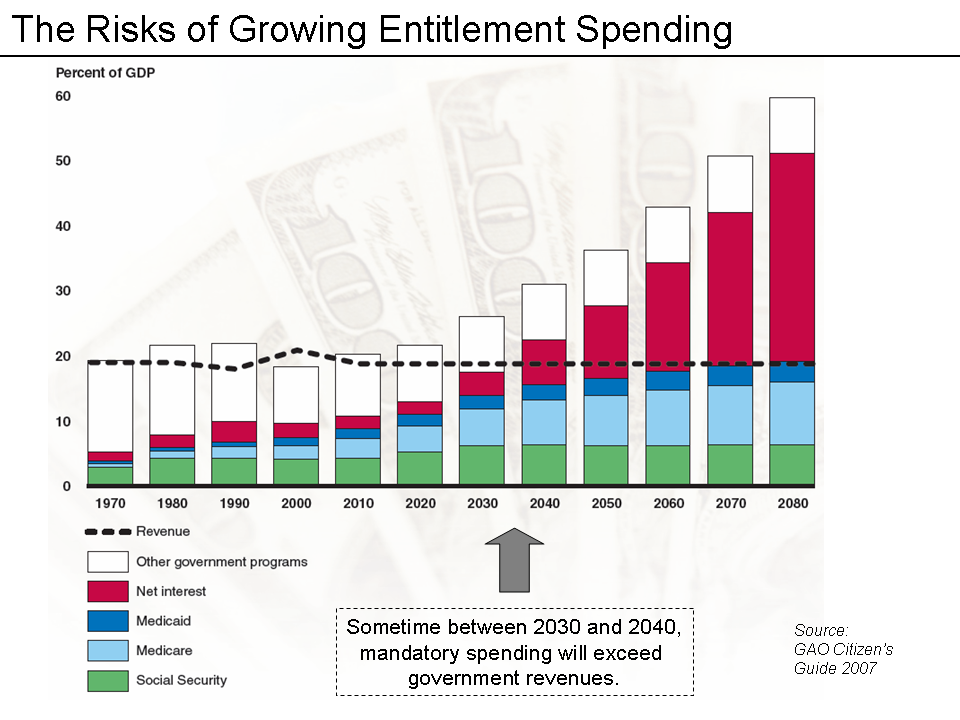

Polls show that a majority of young Americans don’t think Social Security will be around when they retire, but the popular program is in decent shape and could be fixed altogether with relatively painless tweaks. It won’t go away altogether because we’re a democracy and voters will demand to keep it. But we demand more than we’re willing to pay for, and the disadvantage of democracies is that it’s political suicide to ask voters to make even a small sacrifice or balance a budget. So, Americans will pay increasingly more interest on the debt (red on the chart below), burdening future generations. Probably the best solution is for some politicians to lie during campaigns by promising to not fix Social Security, then fix it and not run for re-election.

As history goes, all this may not seem quite as exciting as wars or moon landings, but it’s something every society has to deal with one way or another, and matters to all of us who don’t die young or inherit wealth. Crow Indians used to encourage but not force their elderly to commit suicide. Bolivia’s Sirionó Indians abandoned them when they became a burden. Presumably, we are going to stick with a more compassionate approach, especially since we don’t lose our voting rights when we retire. Happily, Americans on average are living longer. Unhappily, the current entitlement system struggles to keep up with costs at current tax rates, especially on the healthcare portion of Social Security added in 1965. America, Western Europe, and Japan have all made bigger commitments to their retirees than they can handle without moderate adjustments, faster-growing young populations, increased immigration, or explosive economic growth.

The fastest-growing part of America’s safety net is Social Security’s offshoot cousin Medicare, added in 1965, that provides moderate healthcare coverage to the elderly, including subsidies for drug prescriptions since 2005. The default Part A provides hospital insurance while the extra Part B provides general health insurance. With more and better treatments being offered and no price controls on providers (hospitals, doctors, pharmaceuticals), costs have far outrun the general inflation rate over the last generation. Inflation will continue to be a problem in healthcare regardless of whether costs are covered by the government, private insurance, or out-of-pocket. Medicaid, mostly state-funded aid for the poor, faces similar challenges. Under current law, Americans and their employers each contribute up to 7.65% of gross pay for Social Security and Medicare — 6.2% for S.S. and 1.45% for Medicare.

The chart above shows the breakdown in federal spending as of 2015, with interest payments at just 6% compared to today’s 17%. The red and blue portions represent entitlements, including regular Social Security and Medicare, respectively. Technically, defense is one of twelve departments included under discretionary, though some charts list defense as a separate category. Discretionary spending is appropriated annually and includes other agencies, foreign aid, PBS-NPR, and research on science, medicine, and weather. PBS and NPR are fair game in debates about the government’s role in media, but budget negotiations are merely a pretext for cutting them. PBS currently costs the average taxpayer $1.50 per year, or one-hundredth of one percent of the federal budget.