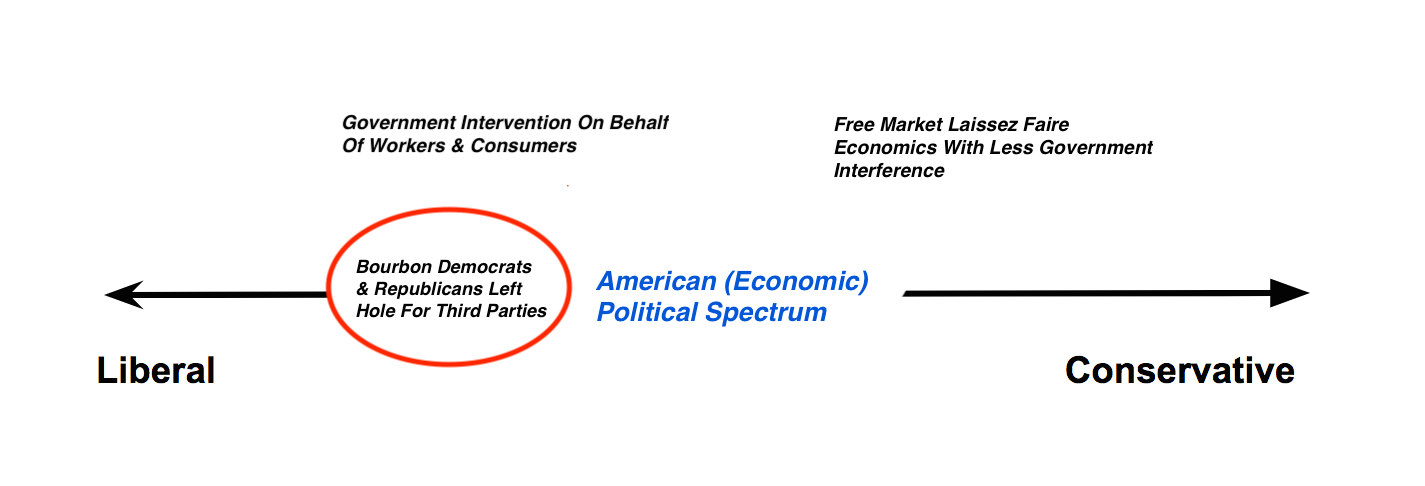

The first three chapters or so of this text are set in the Gilded Age. Mark Twain called the late 19th century the Gilded Age as a play on Golden Age, referring to the way people gilded things with a thin layer to make them appear as solid gold. His novel by that same name satirizes the age’s greed and corruption. Those traits defined the age in some ways — maybe they do all ages — but it was also an era of tremendous economic growth as we saw in the last chapter. With the economy expanding and changing so quickly, political parties were less defined in their platforms and constituents than they are today. The Republicans — or GOP, for Grand Old Party — spurred industry but didn’t cater to the masses of workers who made the engine run. Yet the Democrats didn’t take advantage of the opening that presented them by advocating directly for workers. That left a void filled by more active third parties than at any time in American history. In this chapter, we’ll look at how the political system, local and national, responded to the Industrial Revolution’s growing economy, worker unrest, and large-scale immigration.

Political Machines

The Democratic Party struggled to reinvent itself after the Civil War. They were, in effect, the war’s loser, but remained solidly in control of Southern states after the return of Redeemer (ex-Confederate) politicians in the 1870s. Democrats supported the Ku Klux Klan in the South while, in the North, they campaigned among the very Catholic, Jewish, and Eastern European immigrants the Klan hated and hoped to keep out of the country. From a national perspective, the Democrats were a mess because they cast such a wide net over a diverse working-class coalition.

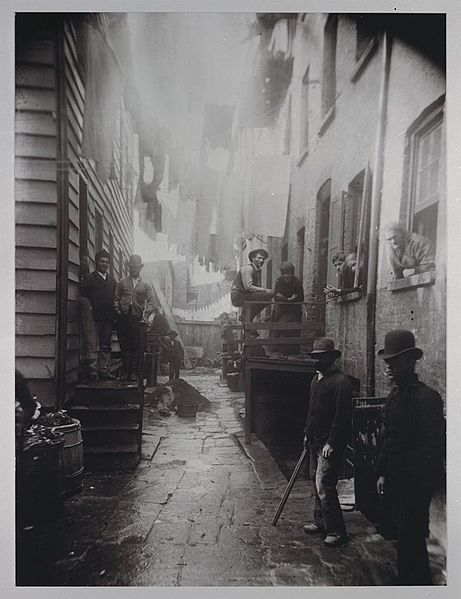

In the North, Democrats helped immigrants get on their feet in an era before employment agencies or institutionalized welfare. When immigrants arrived in New York’s Castle Gardens, or after 1892 Ellis Island, customs processed the vast majority, turning a few back for illness or quarantining them temporarily, like the young Vito Corleone in The Godfather II (1974). The teeming, ethnic neighborhoods of lower Manhattan and nearby boroughs were America’s prototypical “melting pots” and others landed in smaller ports like New Orleans and Galveston and moved to interior cities. Many newcomers arrived with few prospects or connections.

Onshore in New York or other big cities, a local precinct captain, alderman, or ward boss — a foot soldier for the Democratic Party — greeted such newly-arrived immigrants. They offered to set the family up in a tenement apartment, find them a job, or take care of other little concerns to ease their transition. Ward bosses could find a school or job for the kids (more likely job), keep utilities functioning, or even turn on the fire hydrant in summer heat. In exchange, it was understood that immigrants would vote Democrat. In fact, they had to vote Democrat, or else. Voting wasn’t yet private, so people, including those with baseball bats, could see your ballot. By maintaining single-party rule over big cities, Democrats created rings, or political machines. Both parties ran machines and still do depending on how you define them (see HBO’s The Wire for a look at modern Baltimore), but they’re most famously associated with big-city Democrats in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with Chicago’s Daley Machine starting in the mid-20th century after decades of two-party rule there.

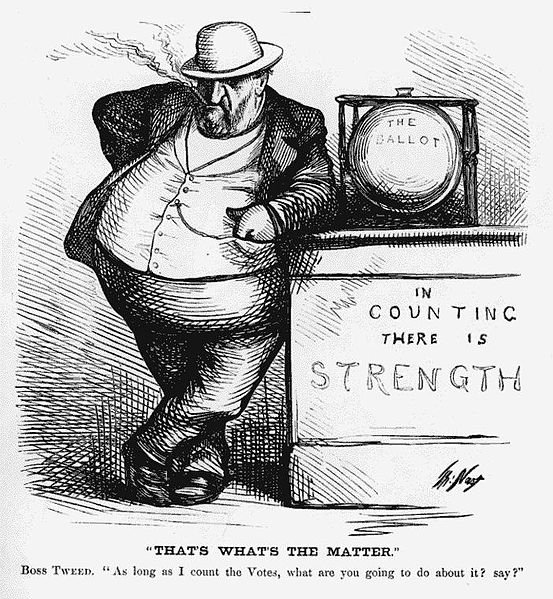

Democrats headquartered at Tammany Hall in New York City were infamous, as were their leaders Boss Tweed and George Washington Plunkitt. Tammany was a political pressure group (what we’d today call lobbyists) that campaigned for Democrats, supplied ward bosses and precinct leaders, and whose hall hosted conventions, serving as an informal headquarters of the Big Apple’s Democratic party. Firmly in control of political patronage (aka the spoils system), the mostly Irish-American machine enabled politicians looking to line their own pockets through graft: skimmed profit made possible by controlling the municipal government, including city hall, police, and utilities. Politicians charged with dispensing contracts to construction companies expected a kickback from winning bidders — enough to pay others to look the other way and keep the rest for themselves. Accountants can create false receipts at different prices. Or, if politicians were popular enough among voters, they could even force city employees to pay them for the privilege of not being fired. There was a lot of graft to be skimmed as cities were growing rapidly and putting in streetcars, water lines, and gas and electric infrastructure. Mayor Plunkitt later conceded that the rate of kickbacks rose “accordin’ to the opportunities.” In Pittsburgh, the Democratic Party gave up any pretense of public bidding and just started their own private road-paving company.

The system wasn’t entirely without merit, even as the machines left upper-middle-class reformers and taxpayers outraged. The initially Republican New York Times, for instance, railed against Tammany Hall corruption, as did upstate Democrats. But machines in Chicago rebuilt quickly after their disastrous fire in 1871 and San Francisco after its earthquake and fire in 1906. American cities were the best in the world by 1900 if measured by the quality of running water, access to electricity, or number of bridges, parks, and paved streets. In other words, stuff got done despite, or maybe because of, what Mayor Plunkitt called “honest graft.” Another upside was that the ward bosses provided some handouts to the working classes in an age before social services or any “safety net.” But their goal was not to lessen crime and disease by eradicating poverty so much as to capitalize on poor people by cashing in their votes. It was a parasitical, if functional, system. Tammany Hall supplemented their income by shaking down gamblers and prostitutes, leaving them in place to pay an informal tax, and even extorting protection money from small businesses in tandem with gangsters. Politicians “on the take” aren’t focused on fixing society’s problems so much as sponging off them.

We still have some corrupt municipal politicians. While there are plenty of local and state politicians today from both parties that end up in prison (see list), the term corruption is a somewhat misleading way to describe the rest because campaign donations offer interest groups, lobbies, and individuals a legal and often even transparent form of quasi-bribery. Wealthy donors usually don’t need to break the law when they can just pay politicians to change the law. Thus, today’s fat cats are more likely to peddle influence with cash than to threaten violence.

Conversely, any traditional “machine” truly deserving of the term worked with and reinforced organized crime, unlike municipalities today. Gangsters “delivered” elections to politicians by intimidating voters or tapping union connections, most famously the Teamsters, who drove carts and trucks. Criminal control over the Teamsters Union, such as what occurred under the leadership of Cornelius Shea, meant that gangsters could demand political favors in exchange for delivering big blocks of voters and not disrupting the flow of goods in and out of a city. Gangsters beholden to politicians for keeping police off their backs could coerce unions to vote in one direction or the other. Politicians won elections with union voters and didn’t interfere with criminal rackets. Racketeering can refer to any type of organized crime, including extortion, numbers (gambling), vice (prostitution), drugs, etc. Organized crime thrives in societies with either corrupt or weak local governments and police. In U.S. history, often only federal law enforcement (or federally-backed local) has been strong enough to confront gangsters. Syndicates like the Mafia worked three sides of the organized labor equation: with companies to break strikes (intimidating strikers), with politicians to deliver votes, and with unions to intimidate strikebreakers (aka scabs), provide security, recruit new members, or jostle with other unions. Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters, for instance, drove off a rival CIO union in 1930s Detroit with Mafia backing. Then the Mafia borrowed from the Teamsters’ pension fund to build Las Vegas casinos and paid it back with cash skimmed from casino counting rooms while keeping plenty for themselves. Combined with torturing and brutally murdering anyone who interfered, this and similar gambits from other cities’ syndicates provided a sustainable business model and built the Vegas Strip, all without reducing truckers’ retirement checks. Las Vegas long remained an “open city,” meaning that gangsters operated at will, without being checked by local law enforcement, and even took it upon themselves to lessen petty crime and invest in schools, churches, etc. Nevada’s state government appreciated the economic boost while the Mob used casinos to make and launder money.

Some criminal intimidation goes on today to prevent unionization in packing plants and service industries (see Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation), but it’s not nearly as widespread as in the Gilded Age. Unions are weaker now than they were in the mid-20th century for other reasons, including automation, overseas outsourcing, and anti-union employer propaganda. In the early 20th century, gangs vied openly to control labor racketeering, as in New York’s Labor Slugger Wars of the 1910s and ’20s. Once unions or governments owed organized criminals favors, gangsters could turn off people’s power, make sure their garbage wasn’t picked up, or ensure they couldn’t get necessary building permits. These “shakedowns” were friendly reminders that businessmen had to pay them for the privilege of doing business in that neighborhood. If the business owner resisted this informal tax or didn’t understand such subtle reminders, “muscle” could destroy their shop or torture, maim, or kill them to send a message to others. Mobs offered “protection” to those that paid up insofar as they didn’t kill them and kept rival gangs away. Such extortion rackets represented an underbelly of Gilded Age political machines. In some ways, protection rackets are miniature versions of politics in its most rudimentary form. Medieval kings collected taxes in exchange for protecting their subjects and that was pretty much all European monarchies then did. We’ll examine organized crime more in Chapters 4 and 7 with Prohibition, and in Chapters 11 and 14 when the federal government cooperated with the Mafia in Sicily during World War II and during Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution.

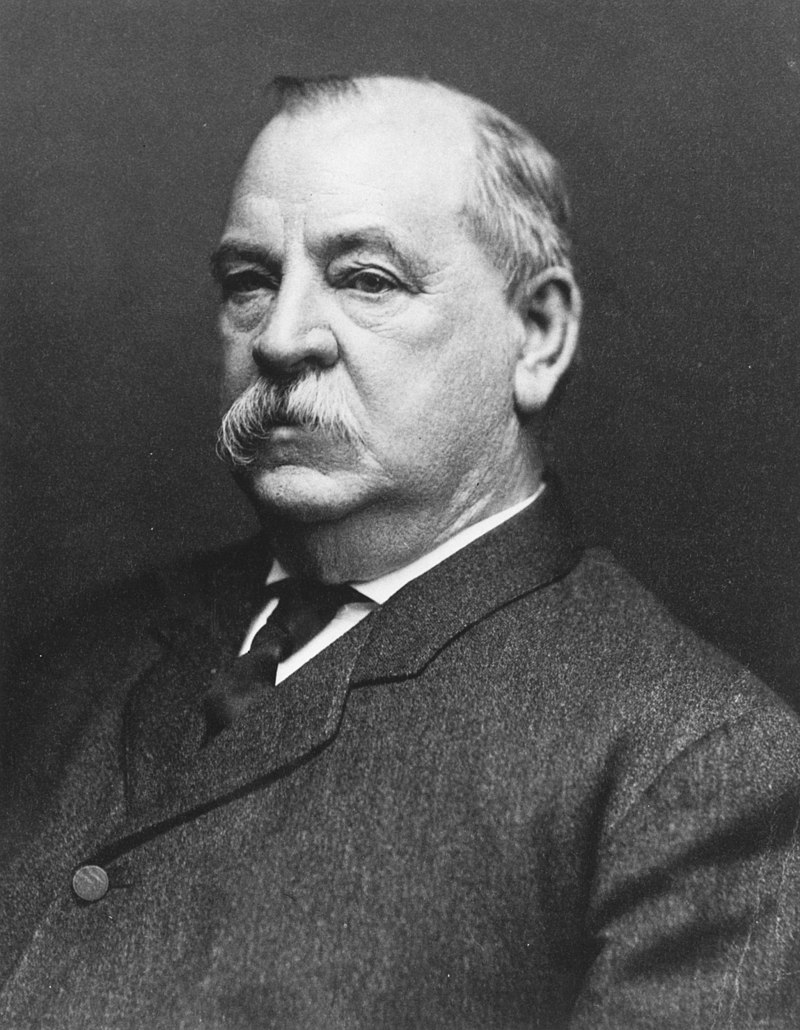

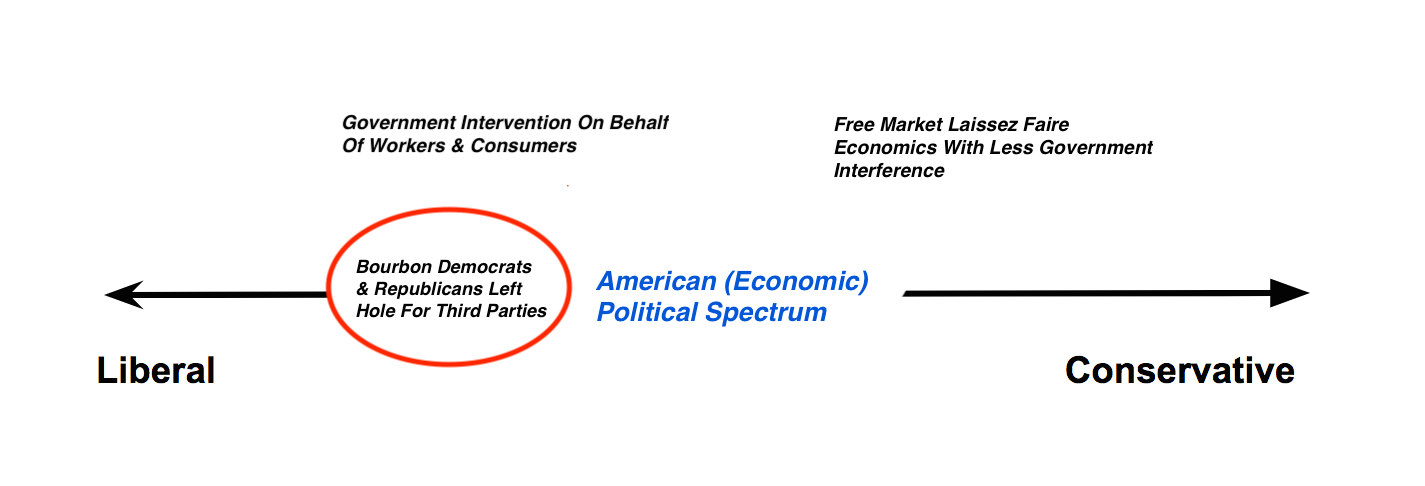

We’ve meandered around long enough exploring the disillusioning and byzantine underbelly of cities, where a lot of people owed a lot of other people a lot of favors. Keep some historical perspective when you hear about corruption in your own time as there were no “good ‘ole days,” and the progressive reformers you’ll read about in Chapters 3 and 4 had much to fix. The key takeaway is that, during the Gilded Age, the united Republicans (GOP) represented business interests and northern middle- and upper-middle classes while the Democrats were cobbled together. Democrats dominated local politics in the South by pandering to racism and in northern cities with political machines enabled by one-party rule and law enforcement too weak or corrupt to confront organized crime. They blurred the line between function and dysfunction. But by the Gilded Age, all white male adults could vote, and Democrats didn’t cash in on the GOP’s management leanings by making a concerted effort nationally for blue-collar workers on farms and ranches and in factories and mines. Instead, the Bourbon Democrats led by President Grover Cleveland (1885-89 & 1893-97) endorsed free markets and tried to compete with pro-business Republicans while distancing themselves from labor. The pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps, Horatio Alger-inspired American Dream idea had worked well, after all, for the Republicans after the Civil War; and for many immigrants, including those initially poor, meritocratic opportunity was part of the United States’ appeal. For Bourbon Democrats that hoped to compete with the GOP by appealing to upwardly mobile, ambitious or successful voters, that commitment seemingly conflicted with outright support for blue-collar workers. Democrats were aligned at the local level with northern political machines and southern Redeemer (neo-Confederate) governments, both of which included plenty of blue-collar workers, but they couldn’t envision or synthesize a healthy combination of robust worker rights and bootstrap upward mobility. Management took advantage by pitting workers against each other along ethnic lines, while workers accurately saw both parties as “in the pocket” of business interests, even if the Republican version was more protectionist (pro-Tariff) and the Democrats more free trade. This left a window of opportunity for third parties to appeal to workers on the political spectrum’s left side (below), which we’ll unpack later in the chapter. First, we’ll examine American labor in more detail.

Labor

Gilded Age politicians operated in the thriving industrial economy we saw in Chapter 1, but prosperity was unevenly distributed. Capitalist economies are cyclical, moving through cycles of booms and busts, and busts hit workers hardest. Bosses (management) and workers (labor) didn’t get along well in the late 19th century, especially during downturns like the Panic of 1873 and Panic of 1893. Miners and factory workers could unionize but management could fire the workers or break up strikes with force. Unions lacked the legal right to collective bargaining, meaning that management wasn’t compelled to negotiate with unions the way they were in many industries after the 1930s and some today.

Lowell & Lawrence Textile Strikers Confronting Strikebreakers and Militia Bayonets, Massachusetts, 1912, George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress

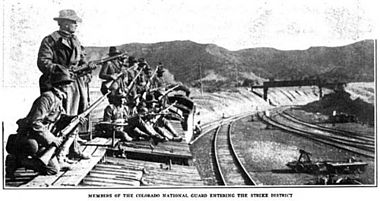

While government maintained a mostly laissez-faire, or free-market, hands-off policy toward business, they were willing to intervene in strikes on behalf of management. Business owners could call out state militias, federal troops, or Pinkerton or Baldwin-Felts detectives to dispel strikers or even attack them. If troops weren’t available, they could pay local muscle to beat up or kill workers. As you can see, if you were good with your fists you were never out of work in the Gilded Age.

“A Steeple-View of the Pittsburgh Conflagration,” Engraving Showing the Burning of Union Depot and Pennsylvania Railroad Yards, Pittsburgh, PA During Great Railroad Strike of 1877, Harper’s Weekly

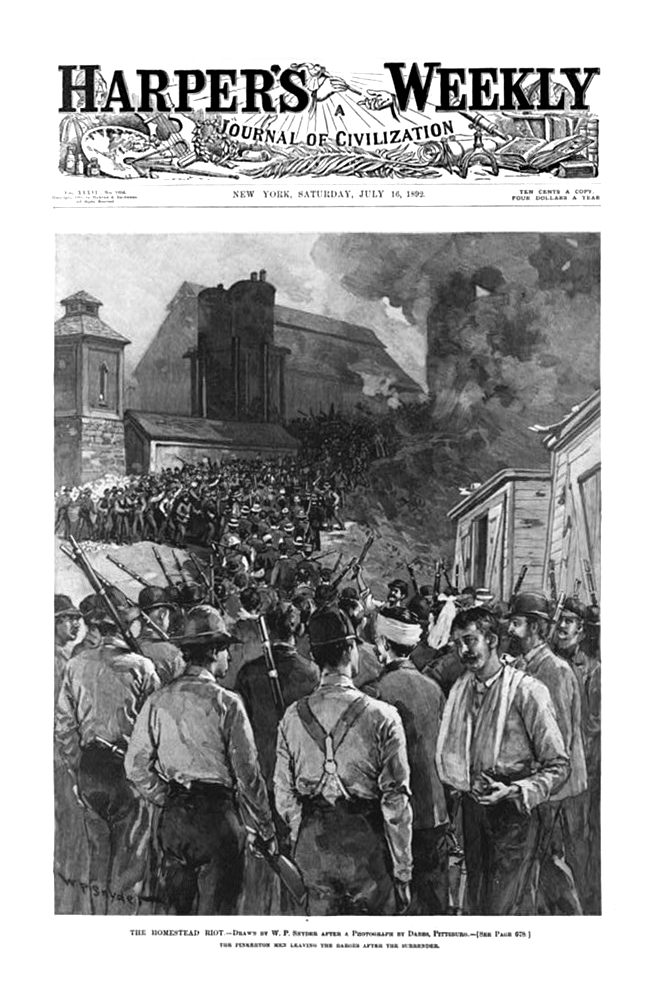

This happened several times in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Homestead Strike at Andrew Carnegie’s steel mill in 1892, the Pullman Strike in Chicago in 1894, and Rockefeller Jr.’s Ludlow, Colorado mine in 1913. Carnegie fancied himself as running a progressive company and didn’t have the nerve to crack down hard on workers who were protesting their 72-hour weeks. He hired Henry Frick as his right-hand man to deal with strikers, renegotiate contracts with suppliers, and cut labor costs, then left for his native Scotland on vacation. Workers took over Homestead and Frick hired the Pinkerton Detectives to break their strike. Pinkertons were America’s mercenary force, hired mostly to apprehend train robbers and, during the Civil War, to protect Lincoln from assassination. By the 1870s, they had more firepower than the slimmed-down U.S. Army. At Homestead, Pinkertons killed nine workers and the governor called in two brigades of state militia to restore order. They ended the strike and steel production resumed with no gains for workers. Carnegie was wise, if cowardly, to hide out in Scotland; the public blamed Frick and an anarchist shot and stabbed him, but he survived — luckily for us as Frick assembled a great art collection worth viewing if you’re ever in New York City.

This happened several times in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Homestead Strike at Andrew Carnegie’s steel mill in 1892, the Pullman Strike in Chicago in 1894, and Rockefeller Jr.’s Ludlow, Colorado mine in 1913. Carnegie fancied himself as running a progressive company and didn’t have the nerve to crack down hard on workers who were protesting their 72-hour weeks. He hired Henry Frick as his right-hand man to deal with strikers, renegotiate contracts with suppliers, and cut labor costs, then left for his native Scotland on vacation. Workers took over Homestead and Frick hired the Pinkerton Detectives to break their strike. Pinkertons were America’s mercenary force, hired mostly to apprehend train robbers and, during the Civil War, to protect Lincoln from assassination. By the 1870s, they had more firepower than the slimmed-down U.S. Army. At Homestead, Pinkertons killed nine workers and the governor called in two brigades of state militia to restore order. They ended the strike and steel production resumed with no gains for workers. Carnegie was wise, if cowardly, to hide out in Scotland; the public blamed Frick and an anarchist shot and stabbed him, but he survived — luckily for us as Frick assembled a great art collection worth viewing if you’re ever in New York City.

At Pullman’s plant, the disruption of train car manufacturing slowed down the region’s economy to the point that federal troops came in to break the strike, killing 30 and injuring 57 workers. George Pullman was a seemingly generous boss, building an upscale company town on Chicago’s south side with schools, churches, and nice homes that workers could rent but not own. But the Panic of 1893 caused him to lower pay and lay off workers without lowering rents, trapping them in his company town. This triggered a violent “wildcat strike” (strike initiated without union authorization) and boycott of all trains using Pullman cars (most). President Grover Cleveland sent in three Army regiments to break up the strike.

Even more dramatic, one of John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s subsidiaries, Colorado Fuel & Iron Co., ordered a military attack on its mining town in Ludlow in 1913, where the Colorado National Guard killed twenty-five people, including eleven kids, some asphyxiated in their tents. This company town, like others, paid workers in coupons only redeemable at the company store, and the death rate was double the already-high national mining average. In response to the National Guard’s massacre, coal miners retaliated throughout the state, killing dozens of troops and Baldwin-Felts agents. The Colorado Coalfield War, overall, was the worst strike-related violence in American history, prompting Congress to push legislation on child labor and the 8-hour day. Rockefeller himself ordered an investigation into the incident, though the strikers lost and went back to work.

While you could look at broken strikes as victories for management, Ludlow suggested that America was teetering on the edge of class warfare in the early 20th century. That prospect was potentially disruptive enough to business that management wanted to defuse the threat. This wasn’t the watered-down version of “class warfare” we use today to spin arguments over whether the rich should be taxed at 39% or 37%. In 1917, the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia demonstrated that there were more radical options out there if enough workers got pushed to the brink. The fact that American workers struck at all under their unfavorable conditions shows how desperate they really were. Who would strike today if it meant they were going to get shot? Often they worked 60-72 hours a week with no injury compensation or vacation and were forced to buy from company stores that overcharged them enough to keep them in debt, making it impossible to leave and find other work. All the money companies paid workers returned to the company. As country singer Tennessee Ernie Ford sang: “You load sixteen tons and what’ya get? Another day older and deeper in debt. St. Peter don’t ya call me ’cause I can’t go…I owe my soul to the company store.”

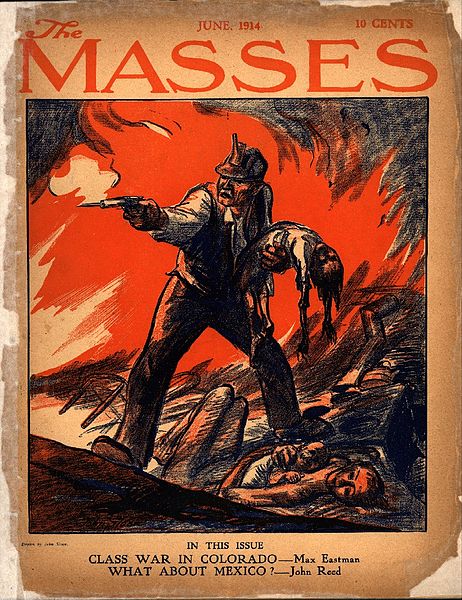

Cover of the June, 1914 Issue of The Masses by John French Sloan, Depicting the Ludlow Massacre, Michigan State University Digital Collections

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, 1902, Library of Congress. Jones was denounced on the U.S. Senate floor as the “grandmother of all agitators.”

That form of virtual or quasi-enslavement is called peonage and its victims are known as debt peons. When Blacks in the post-Civil War South tried to break away from sharecropping and farm their own land, they often found themselves in peonage. For excellent cinematic treatments of the miners’ plight see John Sayles Matewan (1987), set in a West Virginia coal-mining town in 1920, and Barbara Kopple’s 1976 Kentucky documentary Harlan County, USA. Like Ludlow, federal troops attacked Matewan’s workers, in this case bombing them from Martin MB-1’s. Matewan climaxed eight years of labor tension and violence in West Virginia known collectively as the Mine Wars. While mining companies supplemented troops with hired muscle in the form of Baldwin-Felts agents, coal miners led by Mother Jones, now famous for a namesake leftist magazine, armed themselves more heavily than in most labor disputes. Near the town of Matewan in 1920, around a hundred miners and strikebreakers died in the Battle of Blair Mountain, leading to nearly a thousand arrests after the biggest armed shootout in the U.S. since the Civil War. West Virginia’s state government declared martial law, seizing thousands of high-powered rifles and rounds of ammunition along with a few machine guns and assorted blackjacks, daggers, bayonets, and brass knuckles. The short-term result was a victory for management and membership in the United Mine Workers plummeted in the 1920s. However, widespread anger over Ludlow and Matewan rallied workers nationwide and helped lead to the right to collective bargaining during the 1930s New Deal and the strengthening of a larger umbrella labor union, the AFL-CIO.

Prior to the 1930s, American workers had less leverage than those in other countries because there were ongoing waves of immigrants willing to work for lower wages than the preceding group. It was advantageous for management to pit ethnic groups against each other, precluding them from uniting. When Chinese workers arrived in Rock Springs, Wyoming in 1885, willing to work for lower wages than Irish and Italian miners, the Union Pacific’s coal department naturally hired them and fired the Europeans. Euro-Americans took matters into their own hands, killing 28 Asian-Americans and burning 75 homes. You might think the government would’ve supported them in that case due to racism, but they backed the Chinese because they provided cheaper labor. Troops escorted the survivors back to town.

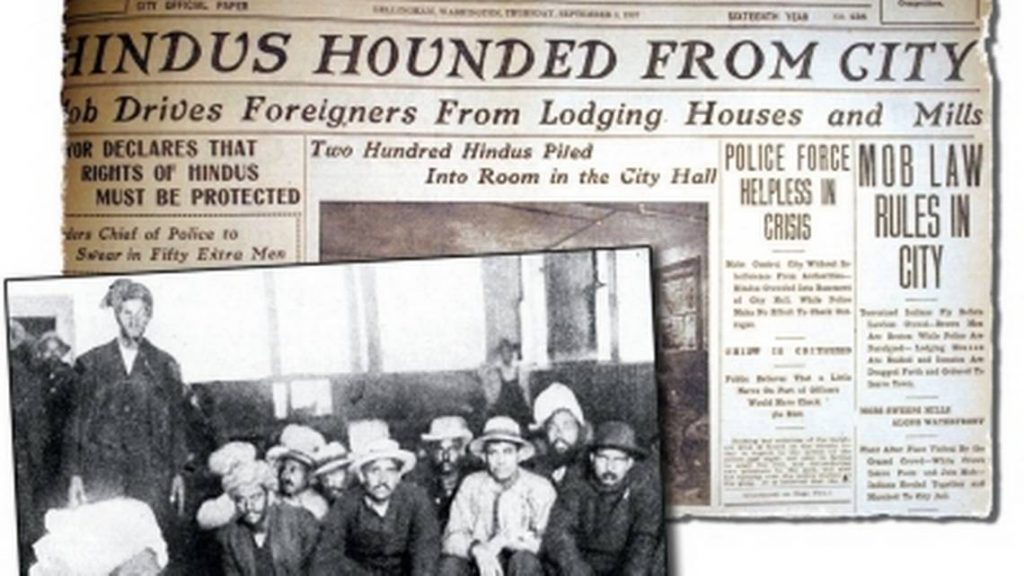

Rock Springs triggered smaller, sporadic violence against Asians across the West, such as an 1885 attack on Chinese hop pickers in Squaw Valley (now Issaquah, Washington), near Seattle. The Chinese had served their purpose by building railroads and laying bricks, so “Native Americans” (Whites) in the Northwest chased most away. Some Asians thrived as merchants, especially in the West (Chinese once made up 10% of the Montana territory’s population). But the U.S. passed anti-immigration legislation aimed at Chinese in the 1880s while some of those already in the country were literally forced underground in Seattle and Portland, despite their American-born children winning citizenship in U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). South Asians fared no better than East Asians. In the 1907 “Hindu Riots” in Bellingham, Washington (above), locals burned down the homes of Indian Americans hired to work dangerous close-to-the-blade jobs in board mills, pelting them with rocks as they fled until local police provided shelter in the city hall. They were all fired the next day and returned to India. Such episodes weren’t confined to the Gilded Age. When the Great Depression hit, white militias attacked Filipino farmers in the 1930 Watsonville Riots that spread to bigger cities.

Exhibit 129a from the Haymarket trial, an unexploded bomb found in the home of Louis Lingg. Chemists testified the bombs found in Lingg’s home matched the shrapnel recovered from the Haymarket bomb. Chicago Historical Society

Political Spectrum & Third Parties

Commentators envision a left-right spectrum of political economy whereby the Left favors more government intervention on behalf of workers and consumers while the right favors a freer, unregulated market. Working-class Whites had won the right to vote in America in the 19th century, but during the Gilded Age neither major political party seemed eager to court their vote. Republicans represented management and Bourbon Democrats were hesitant to be associated with any labor groups that middle classes viewed as anarchistic or revolutionary. Democrat Grover Cleveland made sure that American Labor Day would be September 1st, not the May 1st celebrated in many countries as International Workers’ Day. America also had a small but vocal handful of bona fide violent anarchists, who believed that all government was oppressive and all capitalism was theft, who made it harder for the near left labor movement to gain traction. Left-leaning historians tend to dismiss or downplay their domestic terrorism, but anarchists killed dozens of innocent American priests (Denver 1908, NYC 1914), journalists (Los Angeles 1910), police officers (Milwaukee 1917), and bystanders with bombing attacks in the early 20th century, including financiers on Wall Street that we’ll further unpack in Chapter 6 and the assassination of President William McKinley that we’ll cover below.

In 1886, someone threw a bomb into the crowd at the Haymarket Riot in Chicago, killing seven policemen. The gathering had begun as a peaceful demonstration in favor of eight-hour workdays. No one knew who actually tossed the bomb, but newspapers were quick to depict all the strikers as violent revolutionaries and a chemist testified that shrapnel found at the scene matched a bomb found in one anarchist’s apartment. President Cleveland (D) came down on management’s side, just as he did in the Pullman Strike eight years later (Cleveland was the only president to ever serve discontinuous terms, though Teddy Roosevelt tried and failed).

Leftist unions like the Industrial Workers of the World (aka Wobblies), with loose ties to more violent anarchism, also fought back against authorities, willing to fight back against repression with their own baseball bats. However, that made them susceptible to being arrested or deported. During World War I, a Tulsa World editorial urged the government to kill Wobblies: “Don’t scotch ‘em, kill ‘em. And kill ‘em dead. It is no time to waste money on trials…” There’s a saying that “if you lie down with dogs, you get up with fleas.” Associating with anarchists likewise undermined more legitimate labor groups like the Wobblies, doing the American left a disfavor and counter-productively strengthening capitalism by forfeiting moral authority. When many middle-class Americans heard the word labor, they thought of bombs, not baseball bats, let alone fair wages or hours and safe working conditions. Management benefited from the confusion, undermining regular workers’ prospects.

The Bolshevik (Marxist communist) solution of workers seizing the means of production for themselves — factories and mines in this case — never caught on. America was defined by opportunity and the right of enterprising people to rise up and get ahead, not a place that punished those that got ahead by stealing businesses from them. And virtually no Americans favored suspending representative government in favor of a communist dictatorship. What could American workers do to get a fair shake with neither major party, Republican nor Democrat, on their side and their most passionate advocates throwing bombs? Many gravitated toward more moderate solutions like democratic socialism, Populism and, by the 1930s, stronger labor unions with the right to bargain within the capitalist system.

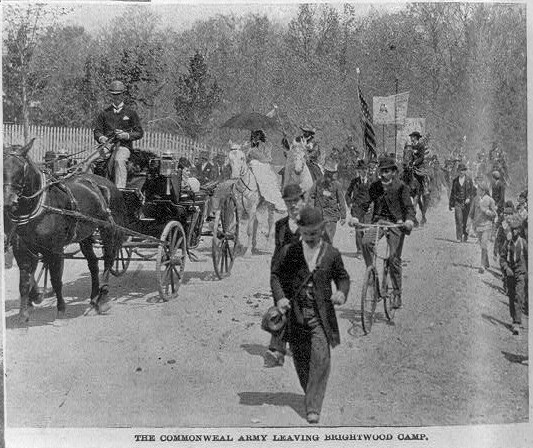

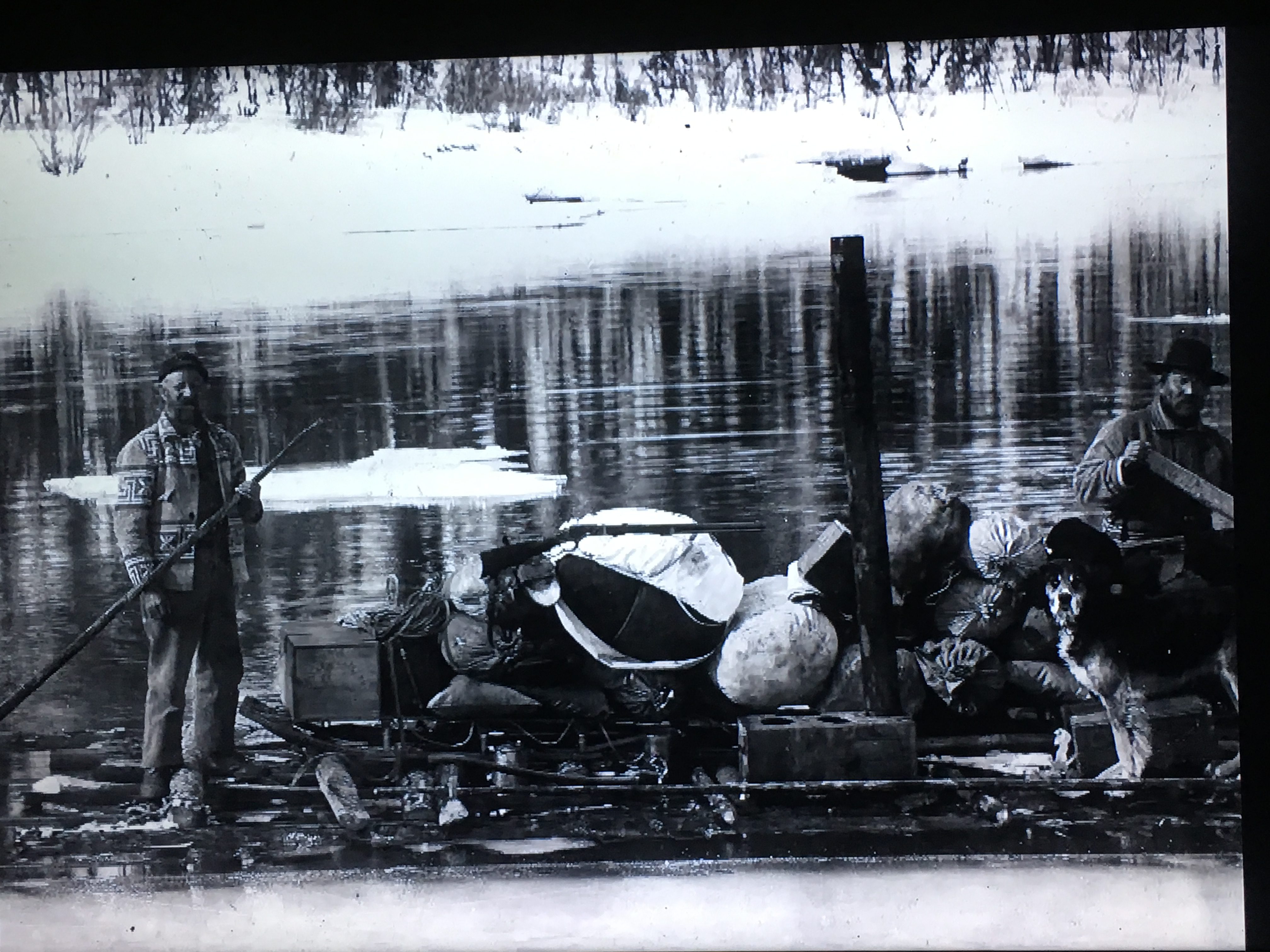

In 1894, Coxey’s Army, officially the Army of the Commonweal in Christ, tried a different tack. Hundreds of unemployed marched on Washington — the first of many such marches in U.S. history — to demand that the government create public works jobs for them, paid in newly printed currency to put more cash in circulation. Thousands fell in and joined Coxey as his army marched halfway across the country, while others rode trains from the West. Since there was massive unemployment of ~ 20% after the 1893 Panic and roads were in terrible shape, why not have the government put people to work building and repairing roads? Instead, they were arrested for stepping on Capitol grass and the movement dwindled. They fined Coxey $5 and sentenced him to 20 days in jail for carrying a picket on Capitol grounds. While lambasted and lampooned by politicians of both parties and journalists, Coxey’s idea laid the foundation for public works stimulus packages during the Great Depression in the 1930s. It was a non-revolutionary idea, completely within the system.

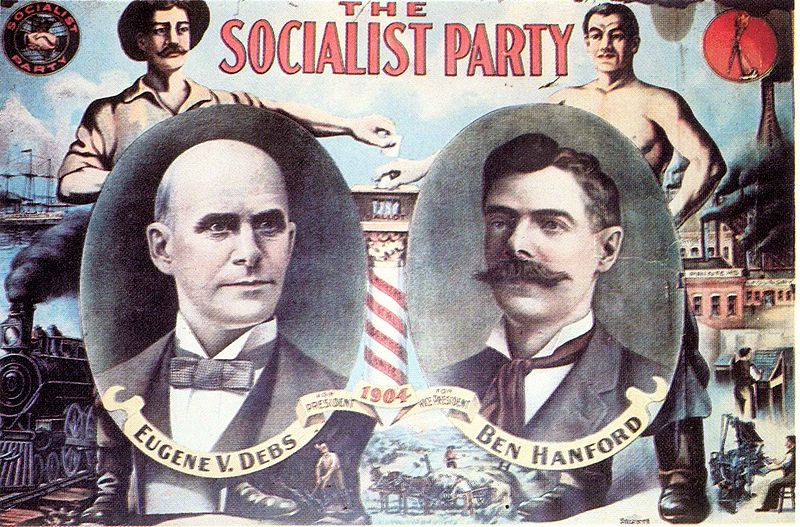

Democratic socialism — like what’s practiced today in Europe (especially Scandinavia), Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and, to a lesser extent, Japan and South Korea — was a more popular option than anarchy, Marxism, or walking a thousand miles only to be arrested for trampling congressional grass. Though often conflated with communism, democratic socialism uses voting to create a regulated capitalist economy that benefits all rather than just a few. It’s a democracy, as its name suggests, rather than a dictatorship. Depending on whose definition you consult, democratic socialism can either work within a market economy (contemporary Europe, modern progressive Democrats, etc.) or situate itself as incompatible with and hostile toward capitalism altogether. There is no agreed-upon definition. American democratic socialist Eugene V. Debs, who favored what later seemed to be moderate proposals like 40-hr. workweeks, child labor bans, and the right to unionize, garnered 6% of the presidential vote in the 1912 election, an impressive showing considering that it was a four-horse race, including another progressive in Teddy Roosevelt, and that the Left had no mainstream history to build on in America. Debs started out working on railroads as a teenager and organized his fellow locomotive firemen (a dangerous job), then broadened the guild to include all rail workers with the American Railway Union and spearheaded the Pullman Strike. The government jailed Debs for overriding a court injunction to lead the secondary (concurrent) railroad boycott during that strike in 1894, charging him with conspiracy. In jail, he read up on democratic socialism, liked the sound of it and converted. We’ll revisit Teddy Roosevelt more in Chapter 5 but his brand of democratic socialism, if someone were to label him as such, was more the moderate, reform-capitalism-from-within variety. That was likewise true of Debs, especially earlier in his career, with his most ambiguous stance being his opposition to wage slavery.

Once out of jail, Debs started the Democratic Socialist Party of America in 1901 and gained a significant following in Southern Plains states like Texas and Oklahoma, running for president in 1912. Then, arrested for protesting America’s entry into World War I, Debs garnered 3.4% of the presidential vote from prison in 1920, setting the record for inmates before President Warren G. Harding (R) commuted his sentence to time served in 1921. The Democratic Socialists never got close enough to whiff real power during the Gilded Age, but their demands for basic worker rights and trust-busting nonetheless absorbed into mainstream politics in a delayed reaction via the Democratic Party in the 20th century. Third parties like the Democratic Socialists and Populists filled the worker-friendly void left by the Republicans and Democrats.

More popular among farmers and rural workers was the People’s Party, or Populists — “Pops” for short — an initially loose conglomeration of granges, co-ops, and alliances that emerged in response to exploitive railroads and banks. The revolution began in Kansas led by Annie Diggs and Mary Elizabeth Lease but spread across rural America in the 1890s. Populists included grain and cotton farmers, coal miners, and railroad workers, among others. Friction with railroads stemmed from all the free land the government had doled out to freight companies. They didn’t grant just narrow strips, but rather wide swaths to re-sell cheaply or give away as farmland (in yellow below). West of the Mississippi, the government gave more land to railroads than the total size of New England. When railroads re-sold the land, it was a seemingly great deal for European immigrants and Eastern farmers looking for a fresh start, but there was a catch. Similar to how printers are cheap today but ink is expensive, farmers got cheap land but then had only one option to ship produce and livestock back east. The freight companies could charge what they pleased, including different rates to different customers depending on how vulnerable they were.

More popular among farmers and rural workers was the People’s Party, or Populists — “Pops” for short — an initially loose conglomeration of granges, co-ops, and alliances that emerged in response to exploitive railroads and banks. The revolution began in Kansas led by Annie Diggs and Mary Elizabeth Lease but spread across rural America in the 1890s. Populists included grain and cotton farmers, coal miners, and railroad workers, among others. Friction with railroads stemmed from all the free land the government had doled out to freight companies. They didn’t grant just narrow strips, but rather wide swaths to re-sell cheaply or give away as farmland (in yellow below). West of the Mississippi, the government gave more land to railroads than the total size of New England. When railroads re-sold the land, it was a seemingly great deal for European immigrants and Eastern farmers looking for a fresh start, but there was a catch. Similar to how printers are cheap today but ink is expensive, farmers got cheap land but then had only one option to ship produce and livestock back east. The freight companies could charge what they pleased, including different rates to different customers depending on how vulnerable they were.

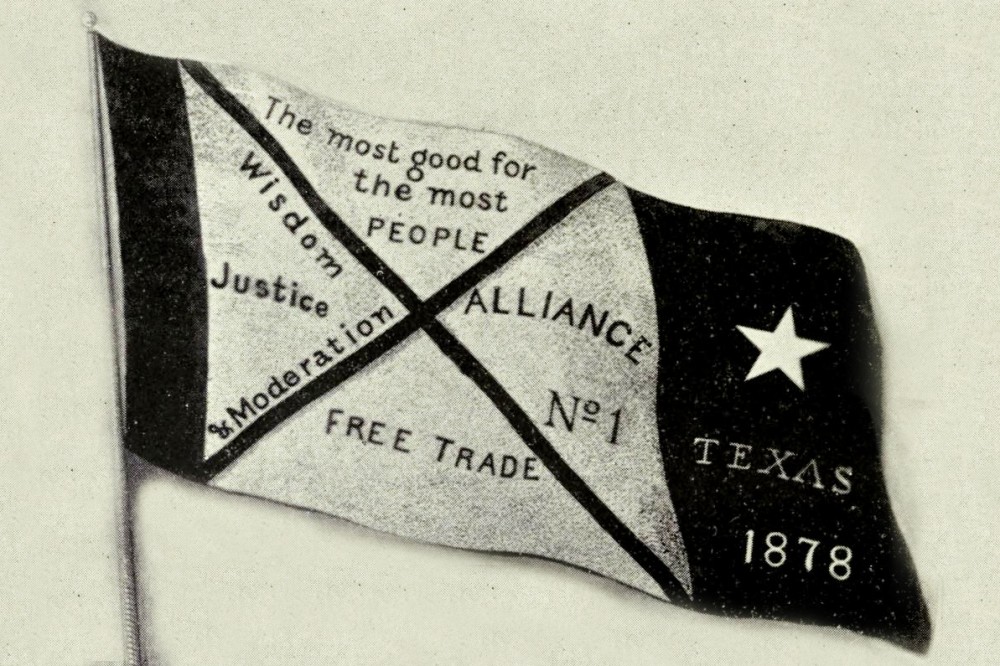

Desperate farmers joined forces, similar to the way factory workers formed unions. In the farmers’ case, they formed cartels called granges to set price basements, below which no one would sell commodities to the railroads. They were organizing in the same way on the supplier side, if in a more transparent way, as railroads or buyers that colluded to fix shipping rates or commodity prices. The biggest such organization struggled to come up with a snappy name, eventually settling on the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry. In 1875, the first Farmer’s Alliance formed in Lampasas County, Texas to protest the power of commodities brokers to dictate which crops farmers grew. Populists eventually formed cooperatives (co-ops) at local grain elevators to pool their resources, as European farmers were doing around the same time. Granges congealed into the broader Populist movement by 1892 that impacted many things beyond farming, including that we pay income taxes, regulate utilities, and vote in private (including for referendums and senators). While the granges’ original purpose was economic, they expanded into dances, barbecues, and sewing bees, contributing to the rural America’s social fabric in the late 19th century. No one wants to pay unfair shipping rates, but it’s also important to gossip, have a good time, and marry off your kids.

The Populists were the first grass-roots political party in U.S. history and illustrate both the potential of participatory democracy and its limitations. Without big financial backing, they never actually won the presidency or control of Congress, but they appealed to enough voters that the two-party system had to take notice of their platform. Populists eventually influenced Democrats and progressive Republicans even though, at first, nothing came of their 1892 Omaha Platform. But starting in 1894 the Democrats endorsed the Populists’ idea of a national income tax to redistribute wealth and some claim that Populists also originated the idea of a Federal Reserve (central bank). Other Populist ideas gradually came to fruition, including railroad and bank regulation and the first major regulatory agency, the Interstate Commerce Commission.

Populists influenced two constitutional amendments: the 16th of 1913 that created the Federal Income Tax and the 17th mandating direct election of senators. Citizens first only voted for the lower House of Representatives while state legislatures elected Senators. The 16th Amendment redistributed wealth since the tax code was graduated, or progressive, with rates (not just totals) escalating with higher incomes. Redistribution wasn’t dramatic at first but was significant in the mid-20th century before the top brackets came back down in the 1980s, and even today top rates are moderately higher for income but not investments (more in Chapter 5). There was a national income tax once before, briefly during the Civil War, but the Supreme Court deemed it unconstitutional prior to the 16th Amendment.

Populists also supported private or secret ballots (aka Australian or Massachusetts ballots) so that voters could no longer be intimidated, bribed or charmed at the voting booth. Today both parties complain from time to time of voter intimidation at the polls, but whoever is doing the intimidating can’t see who the voters are voting for anyway. Exit pollsters can ask who you voted for, but sharing your information is voluntary. In the Gilded Age, making voting private undermined political machines or intrusive bosses that employed intimidation to swing votes (more below).

Populists also advocated public ownership of telephone-telegraph companies. As we saw in the previous chapter, Ma Bell, named for telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell, broke up in 1984, leading to the private “Baby Bells.” But, between WWI and the 1980s, the government oversaw the one phone company.

If all that’s not enough, Populists brought about, for the first time in U.S. history, direct democracy in the form of referendums, propositions, recalls, and initiatives still used for some ballot issues, but not to govern the entire country. Direct democracy was not a prospect that endeared America’s Founders to classical Athens, Greece, and they took pains to avoid it. They preferred the one-step-removed republican or representative democracy model, with its role for elected politicians as intermediaries. Representative democracy is sometimes called a parliamentary democracy or constitutional republic. Populists not only accomplished much for a third party, they undoubtedly accomplished more than the major parties usually do in such a short time period. Populists, aka the People’s Party, demonstrated the power of grass-roots politics and how third parties can impact the mainstream “from the bottom up.”

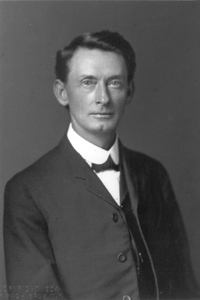

Despite including many black farmers, Populism often had racist undertones, including anti-Semitism toward purported Jewish influence on Wall Street and opposition to immigration. Some Populist leaders differed from Eugene Debs, who, as a staunch critic of Jim Crow, would’ve at least preferred for the Democratic Socialist Party to integrate; though they, too, feared that would scare away white workers. Favoring immigration might seem like a logical populist stance since most immigrants are workers but, as we saw above, workers feared immigrants taking their jobs or working for less, just as they do today. Anti-immigration is a centerpiece of today’s small-p populism. Tom Watson (right), a prominent Georgia Populist, editor, Senator, and Democratic vice-presidential nominee, wrote:

Despite including many black farmers, Populism often had racist undertones, including anti-Semitism toward purported Jewish influence on Wall Street and opposition to immigration. Some Populist leaders differed from Eugene Debs, who, as a staunch critic of Jim Crow, would’ve at least preferred for the Democratic Socialist Party to integrate; though they, too, feared that would scare away white workers. Favoring immigration might seem like a logical populist stance since most immigrants are workers but, as we saw above, workers feared immigrants taking their jobs or working for less, just as they do today. Anti-immigration is a centerpiece of today’s small-p populism. Tom Watson (right), a prominent Georgia Populist, editor, Senator, and Democratic vice-presidential nominee, wrote:

“We have become the world’s melting pot. The scum of creation has been dumped on us. Some of our principal cities are more foreign than American. The most dangerous and corrupting horde of the Old World has invaded us. The vice and crime they planted in our midst are sickening and terrifying. What brought these Goths and Vandals to our shores? The manufacturers are mainly to blame. They wanted cheap labor, and they didn’t care a curse how much harm to our future might be the consequence of their heartless policy.”

Watson’s brand of xenophobia weaves its way in and out of American history and we’ll revisit immigration in Chapter 7 when the U.S. passes a law keeping out most Old World “hordes” from 1924 to ’65. Asians were already restricted from 1882-1965. Populism presents a quandary for historians prone to dualistic stories of good guys (immigrants and working classes) versus bad, “The man” (management). As developed in more detail in the optional article at the bottom of the chapter, working classes already in America usually don’t favor lenient immigration. Likewise, some Suffragists allied with racists to oppose black men winning the vote before white women. A full picture of Populism includes its bigoted underbelly, along with consideration for the fact that banks who loan farmers money have a right to expect it back under agreed-upon terms. Otherwise, for one thing, they’d eventually go out of business and be unable to lend to future farmers. However, banks charged usuriously high interest rates of 20-30% to some during the Gilded Age. Many of these sodbusters remembered a time when they were more or less self-sufficient and naturally resented falling further and further behind to Eastern corporations despite working hard. For many, fighting back politically wasn’t just a matter of resentment, but even survival.

While the Populist Party isn’t around anymore, the granger spirit lives on in member-owned companies called cooperatives. The first co-op predated the Populists and was also the nation’s first department store: Brigham Young’s Zionist Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI) opened in Salt Lake City in 1868. Cooperatives aren’t cartels like the granges, but their businesses keep control in the hands of members and employees instead of upper management, corporate boards, or shareholders. Independent retailers, for instance, “chain” together to form Ace Hardware and True Value. Credit unions are member-owned banks. Texas has rural electrical, food, housing, and radio co-ops and even an incubator called Cooperation Texas. Here in Austin, we have Wheatsville Food (1976- ) and Black Star Pub & Brewery (2010- ) that, in turn, inspired more brewpub co-ops in Austin (4th Tap), Los Alamos, NM (Bathtub Row), Seattle (Flying Bike), Minneapolis (Fair State), and Dayton (Fifth Street). Not all co-ops are small. There’s the national REI retail chain and farmers/ranchers own St. Paul-based Fortune 100 company Cenex Harvest States, or CHS. Others include W.W. Norton & Co. (publishers), Land O’Lakes, Ocean Spray, Sunkist, Welch’s, Organic Valley, and New Belgian Brewing (Fat Tire) from 1991 to 2019. Nearly a billion people worldwide belong to cooperatives of some sort, ~ 12% of the human population. Despite being solidly Republican today, North Dakota still retains vestiges of its socialist/Populist past with a state-owned bank, grain mill, and grain elevator.

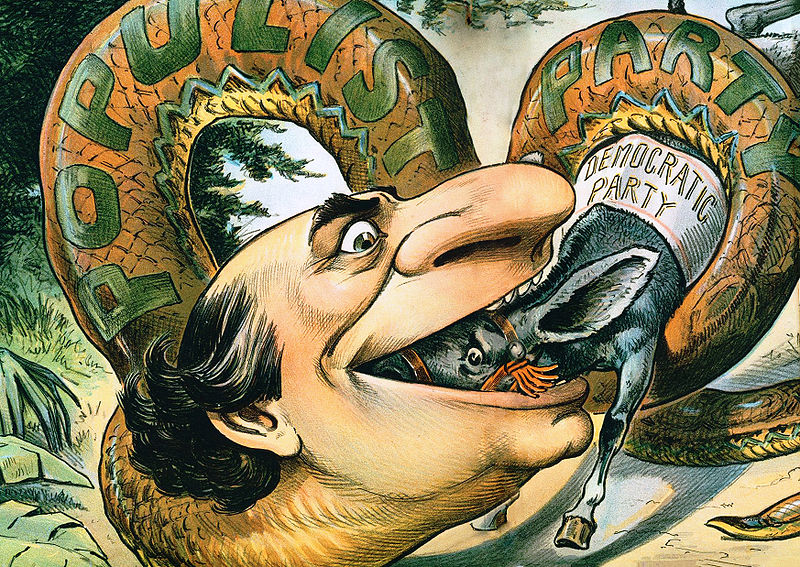

The Populists were waning by the late 1890s, but they still had too much power to be ignored. Most of the accomplishments just listed, in fact, came after 1900. Democrats co-opted them, just as mainstream Republicans have soaked up the Sarah Palin/Tea Party-Freedom Caucus/Donald Trump faction more recently. In this case, Democrats got crushed outside the South in the 1894 midterms and needed to expand their geographic footprint onto the Great Plains, where Populists lived. One historian noted that third parties are like honey bees: “Once they’ve stung, they die.” But that historian was wrong: co-opting cuts both ways, as the cartoon below suggests, with a Populist snake devouring the Democrats. Modern “establishment” Republicans discovered the same, with Palin, the Tea Party, and Trump reshaping the GOP in their image. The former mainstream Republicans have to tuck their tails and apologize, not the other way around. In the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Democrats gradually morphed from the Confederacy’s worn-out remnants and a handful of big city machines into a broader workingman’s party because of their overlap with the Populists. Their fusion precluded the Democratic Socialists from gaining traction, but Populist and democratic socialist elements infused the Democratic Party after Woodrow Wilson’s election in 1912 and, especially, with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s/40s.

William Jennings Bryan/Populism as a Snake Swallowing Up the Mule Representing the Democratic Party, Judge Magazine, 1896

Note:

The term populist — like enlightenment, reconstruction, progressive, democrat, and republican — has a different meaning depending on whether or not it is capitalized. The Populists were the conglomeration described above, but populist with a small p is used to describe any politician, group or policy more popular among the “people” than “elites.” Bernie Sanders (D), Palin (R), and Trump (R), for instance, are each populists by some broad definition. Historian Francis Fukuyama described populist broadly as “a label political elites attach to policies supported by ordinary citizens they don’t like.” But GOP columnist David Brooks reminded readers of the potential downside of populism, writing in the New York Times op-ed page that “Populism doesn’t demand the effort required to understand the best that has been thought and said. Populism celebrates the quick slogan, the impulsive slash, the easy ignorant assertion. Populism is blind to mastery and embraces mediocrity.”

Silverites vs. Goldbugs

Democrats also tapped into farmers’ frustration at the lack of currency in circulation. They pushed for printing more money by converting the U.S. from a gold standard, whereby paper money corresponded to bullion in treasury vaults, to a bimetallic standard of gold and silver. The government tied paper money to the finite gold supply and, even now, all the gold ever mined would only fill up three Olympic swimming pools, or a third of the Washington Monument. Printing more money is inflationary, but farmers were more likely to be debtors, borrowing in the spring to plant and paying back in the fall after harvesting (why poor farmers were subject to peonage). Business leaders and creditors (lenders) supported the traditional gold standard and disliked inflation. Unlike debtors who profit from inflation (e.g., students, homebuyers, farmers, governments), creditors lose money when people repay later after the original amount borrowed in nominal dollars is worth less than the real amount in adjusted dollars. Earlier, similar logic sparked the Greenback movement among farmers because the real value of their loans was going up with deflation (Greenbacks ran James Weaver as a third-party presidential candidate in 1880). The Greenback movement folded into the broader Populist/People’s Party, then into the mainstream Democrats. Democrats lobbied for unlimited silver coinage after debate at their 1896 convention in Chicago, where Silverites derided incumbent president Grover Cleveland and the Bourbon Democrats for catering to banker J.P. Morgan by keeping the U.S. on the gold standard.

Workers and consumers were also agitating to break up the big trusts run by Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and John D. Rockefeller and wanted an income tax on the wealthy to replace tariffs as a source of federal revenue. This was a significant transition for the Democratic Party, which had been a party of Jeffersonian small government since its inception in 1791 (they formally became a party in 1828). Populists and Democrats (and some “Silver Republicans”) all nominated the same man to lead the bimetallic charge as their presidential candidate in 1896 and 1900: fiery Nebraska populist William Jennings Bryan, with the forenamed Tom Watson as his vice-president in 1896. Bryan inverted trickle-down economics (he called “leak”) by arguing that if politicians legislated to benefit the masses, workers’ wealth would instead trickle-up to the classes that depend on their labor. Pioneering the whistle-stop campaign (previous chapter), W.J. Bryan appealed to his constituency by arguing that cities needed farms more than farms needed cities: “Burn down your cities and leave your farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.” Channeling a Christ-like martyrdom in support of the bimetallic standard, Bryan declared, “You shall not crucify mankind on a cross of Gold!”

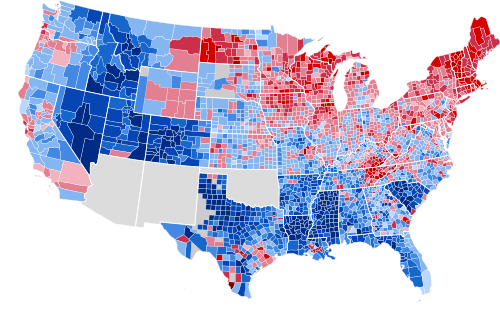

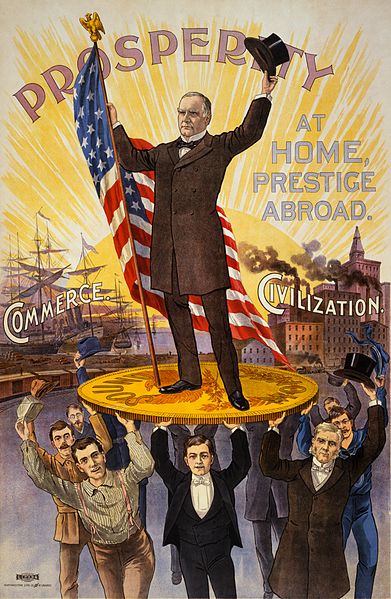

1896 Election

William McKinley (R), a Civil War veteran, defeated William Jennings Bryan (D, P) twice, in 1896 and 1900. The 1896 election signaled the two-party system’s entrenchment, with the Democrats having soaked up the Populists even though, according to our cartoon, it was really Democrats being digested by the Populist snake. The GOP, which had soaked up the anti-immigration Know-Nothing party before the Civil War, shed its anti-immigration stance enough to appeal to Catholic voters for the first time in 1896, though we didn’t have a Catholic president for another 64 years in Democrat John Kennedy. It was also the first election when Republicans openly collected corporate campaign donations. Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Morgan resolved to put their differences aside temporarily and buy themselves a president, each pitching in around $20 million (adjusted for inflation). That bought them, among other things, editorial rights over their candidate McKinley’s speeches.

Some background on campaign finance is in order here. In 1881, a campaign supporter killed President James Garfield because the incoming Garfield administration denied him a government post. Congress responded by creating the Civil Service to provide such jobs based on actual merit, cutting off patronage as a source of campaign influence. However, in a classic case of regulation solving one problem by creating another, that had the unintended effect of sending candidates elsewhere for support. GOP campaign manager Mark Hanna demanded campaign donations from the country’s biggest corporations, impressing upon them that the alternative of having a worker-friendly president and “revolutionary, anarchistic” Democrats would be far worse. That wouldn’t have been the case if Grover Cleveland was still the Bourbon Democratic candidate, but the populist/Democrat W.J. Bryan threatened the “Top 1%.” The results were nearly as regional as the Civil War-era 1860 election.

The Industrial Revolution pitted workers against the wealthy and leftist historians mark the 1896 election as a point when money and capitalism won out over democracy and equality. The government crushed labor as we saw above, then Robber Barons bought the 1896 election, blunting the peoples’ will, according to this narrative. The GOP told workers that they were already being paid well and that their paychecks were only worth something because the government backed their cash with gold. However, in 1896 the Republicans didn’t just quash farmers, miners, and factory workers; they made their own policies more worker-friendly.

Here’s how. The overriding problem plaguing the American economy was over-production. Farmers were growing more food than Americans could eat and factories were making more goods than Americans could consume. Simply put, production was outrunning consumption. The solution Republican candidate William McKinley offered was to expand militarily and tap overseas markets. That would not only be good for business, it would fill the plates of workers. McKinley flipped the script on Bryan’s trickle-up theory, arguing instead that money would trickle down from spenders and job-creators to workers — or, as he put it in his 1900 campaign slogan, a “full lunch pail.” For good measure, Republican managers told factory workers they’d be locked out if they voted for William Jennings Bryan and monitored polling stations. The 1896 election thus led directly to the forementioned secret ballots (private voting) because of the backlash against employers controlling employees’ votes. For good measure, the GOP dropped alcohol prohibition from its platform, hoping to win some “wet” immigrant votes. Appealing to Catholic immigrants helped, but most working-class Catholics voted Democrat until Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in the 1970s.

The discovery of gold in Alaska and the Yukon Territory in 1896, the same year as the election, allowed the government to print off more money while staying on the gold standard, ending the bimetallic controversy. The monetary stimulus helped the economy revive. Since 1971, U.S. currency is fiat, untied to any commodity, as are most cryptocurrencies.

Also, just after the 1896 election William Jennings Bryan introduced the tradition of the concession speech, whereby the loser validates the victor and underscores America’s peaceful transition of power with a telegram, call, speech, or (looking ahead) Tweet®. The tradition lasted for 120 years, through the 2016 election. While peaceful transfers of power might seem like a symbolic feature of democracy, they are really the linchpin because they’re essential to elections in general. Concession speeches and the tradition of newly-elected leaders riding with incumbent presidents down Pennsylvania Ave from the White House to the Capitol inauguration, dating from Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren’s carriage ride in 1837, symbolized that peaceful transfer.

And, after the 1896 election, the two main parties colluded to make it more difficult for third parties like the Populists to get on ballots. Like their southern Democratic counterparts, northern Republicans instituted literacy tests, in their case to disenfranchise immigrants rather than Blacks and Hispanics. The main parties also pioneered caucuses to help determine candidates in the 1890s, allowing eligible voters to meet in schools, church basements, and living rooms to debate whom the candidates should be. Having excluded much of the “riff-raff” they didn’t want in the democracy, the parties felt comfortable turning to primary elections, aka primaries, to decide their candidates. These are informal elections whereby parties decide their candidate before the general election. Primaries, especially those utilizing caucuses meeting locally often excluded minorities, immigrants, and radicals. These segregated caucuses weren’t prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment’s ban on state-sponsored racism because, like private businesses, political parties aren’t officially connected to, or formed by, the government, even though they operate within the government. Unlike primaries conducted since the 1970s, older versions were just elaborate opinion polls rather than being binding, but they nonetheless had an important role in parties deciding their nominees. Since today’s primaries actually determine candidates (superdelegates notwithstanding) and changes in the 1960s banned voting restrictions like literacy tests or segregated caucuses, this Gilded Age practice enacted to make the country less democratic ironically made it more democratic in the long run by introducing primaries and inclusive caucuses that give Americans greater say in choosing their leaders. When everyone is invited, caucuses and primary election campaigns provide a grass-roots connection to the major parties.

Wash Drawing by T. Dart Walker Depicting the Assassination of President William McKinley by Leon Czolgosz at Pan-American Exposition Reception on September 6, 1901

President McKinley defeated W.J. Bryan again in 1900, but loner anarchist Leon Czolgosz (shul-gosh) shot and killed him at Buffalo’s Pan-American Expo in 1901, catapulting his new VP Teddy Roosevelt to office. Czolgosz, a Polish immigrant, had been laid off at a steel mill overtaken by J.P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel conglomerate and he thought McKinley was to blame. After his bosses blacklisted him for striking he took on the alias Nieman, German for nobody. Some Thomas Edison footage captured the crowd outside the building as the news spread. The wounded McKinley told the crowd to go easy on Czolgosz and to break the news gently to his wife, Ida, as they took him off to a makeshift operating room to repair his torn stomach. He died a few days later, saying, “It is God’s way…His will be done.” Edison capitalized twice, by also filming a re-enactment of Czolgosz’s electrocution during the War of the Currents.

In the next chapter, we’ll examine how McKinley and Roosevelt had already expanded America’s fledgling overseas empire, even before McKinley’s assassination. In the chapters after that, we’ll see how the ornery Teddy Roosevelt (TR) took on the very corporations that put his fallen boss McKinley in office, likely threatening the status quo as much as W.J. Bryan would have. After the Ludlow Massacre, for instance, TR called the Rockefellers “a bunch of crooks.” Roosevelt made a prophet out of McKinley’s aid Mark Hanna, who’d opposed putting TR on the ticket as VP and asked, “Don’t any of you fools realize that there’s just one life between that damned cowboy and the White House?”

Optional Reading:

Joshua Zeitz, “Historians Have Long Thought Populism Was A Good Thing. Are They Wrong?” Politico (1.14.18)

Li Zhou, “The Long History of Anti-Asian Hate in America, Explained,” Vox (Updated 3.5.21)

Ben Railton, “Considering History: Seattle & the Worst and Best of American Expansionism,” Saturday Evening Post (7.11.23)