“It is apparent to me that the possibilities of the aeroplane, which two or three years ago were thought to hold the solution to the [flying machine] problem, have been exhausted, and that we must turn elsewhere.” –– Thomas Edison, 1895

More than any era in American history, economics dominated the late 19th century. Historians downplay presidents like Chester Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, and Grover Cleveland because inventors and businessmen dictated the country’s direction. In the 1872 presidential election, for instance, members of Western Union’s board of directors chaired both major party conventions. Influence peddling (lobbying) is ongoing, though. What set this era apart was innovation and the changing role of workers. The Industrial Revolution had accelerated historical change since the 18th century, but the fifty years after the Civil War saw the most dramatic burst of technological ingenuity since the dawn of mankind. The rustic world of yokes and oxen gave way to harvesting combines, electricity, steam turbines, automobiles, planes, movies, phones, radios, record players, calculators/cash registers, petrochemicals, vending machines, antibiotics and, perhaps most importantly, running water/indoor plumbing. Many children were born into a world before the Civil War that more resembled the Middle Ages than the mid-20th century they’d live to see. Humankind has been around for ~ 300k years, but the current carnival ride of rapid change, on which our inventions and choices create our future, has only been around for two-and-a-half centuries.

As you read about this extraordinary era, don’t get bogged down in the details. The text includes names, places, dates, and intricate details just to orient you, but you don’t need to memorize these. Your task is to read actively after going over the 1302 Learning Objectives for this chapter (found under the Chapters-LO’s drop-down above). Condense your responses to these LO’s to three or four sentences. Don’t stop at very many links. They are there for your general edification if you’re confused about a term or would like to learn more, but you should generally pass over them. You should pay attention to images and maps, though. Always use the arrow down key ↓ instead of the scrollbar when reading online. If you’ve signed up for HIST 1301 rather than 1302, stop and read the Paleo-America & Columbian Exchange chapter instead.

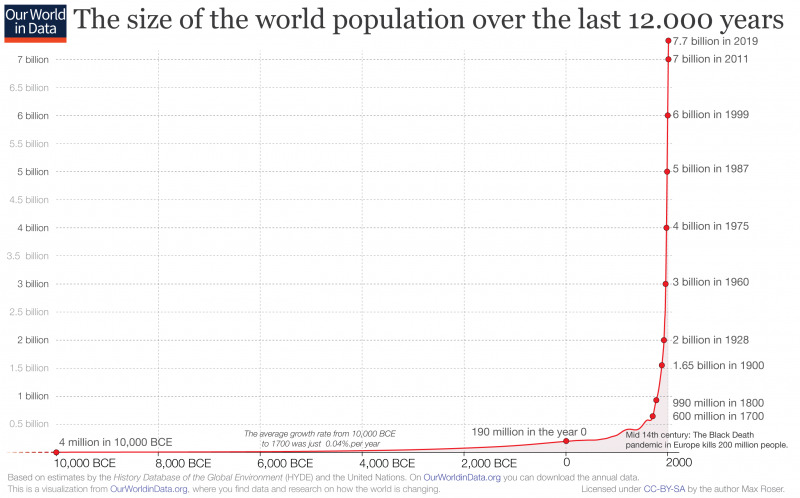

Visitors to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 who came to celebrate the nation’s 100th birthday saw inventions like bicycles, escalators, and typewriters amidst huge Corliss steam engines. They even tried a new concoction called Root Beer and an exotic, oddly-shaped fruit called the banana. Thomas Edison built America’s first power station six years later, in 1882. Siegfried Marcus built the first gasoline-powered car in 1864 and fellow German Karl Benz produced the first fully functional cars in 1885, paving the way for trucks, tractors, and boats/ships also powered by internal-combustion engines. Visitors to the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 saw its entire Columbian Exposition lit by electricity, and most had coal-fired electricity in their own homes by the 1920s. Almost all of the world’s population growth has come since the Industrial Revolution, which also sped up the rate of change in other areas of history: social, political, cultural, etc. Industrialized agriculture was crucial to population growth, especially the Haber-Bosch fertilizer process and other parts of the Green Revolution (mechanization, pesticides, high-yield crops). The universe is 13.8 billion years old. If we reduced ~ 14 billion to 14 years, Earth appeared five years ago, life seven months ago, dinosaurs three weeks, humans three minutes, and the Industrial Revolution six seconds ago. We’re in new territory. Nearly everything else we’ll cover in ensuing chapters felt the impact of this technological and economic transformation. And we’re in new imaginative territory because, amidst these rapid transformations, we now sense dramatic historical distinctions between the past, present, and future. Unlike most humans prior to the 19th century, we take it for granted that our lives are very different than those of our grandparents and grandchildren. With no Industrial Revolution, science fiction books like H. G. Wells’ Time Machine (1895) wouldn’t have envisioned a more advanced future.

In the late 19th century, industrial titans pioneered modern business and became the richest men ever while the poor lived in squalor, grinding out long, dangerous workweeks. The middle classes boomed with rising standards of living, increased life expectancies, and decreased infant mortality. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a crude but reasonably effective measure of overall output, grew most years. The exceptions were big recessionary panics in the mid-1870s and mid-1890s. These booms and busts were a familiar part of the economic landscape since the beginning of the Market Revolution that swept American farmers, craftsmen, and housewives into an integrated global economy in the early 19th century.

By the Civil War (1861-65), the U.S. was deep in the throes of an Industrial Revolution that began with the advent of steam power in England in 1698. Mechanical engineering, especially in textiles (clothing and other fabrics), and the application of coal-fired steam to factory production and transportation (locomotives and steamboats) took off after the War of 1812, when the U.S. had been temporarily cut off from British trade and became more self-sufficient. Because enslaved workers on southern cotton plantations weren’t paid, the overall cost of clothing made in northern and British textile mills was affordable — similar to how overseas sweatshops drive down wholesale costs today. Americans helped pioneer interchangeable parts and mass production in firearms, shoes, typewriters, and sewing machines. Improved agricultural implements led to more crops, moved around the country on a water highway of rivers and canals, the most famous and important being New York’s Erie Canal (built 1818-25). Most industry was in the North. Southern cotton fed northern textile mills, but only around 10% of factories were in the South, with most of those on the periphery of a vast agricultural area. While also boosting shipping, banking, and retail, cotton clothing was one big Atlantic economy with varying combinations of slavery/wage labor and manual labor/automation.

By the Civil War (1861-65), the U.S. was deep in the throes of an Industrial Revolution that began with the advent of steam power in England in 1698. Mechanical engineering, especially in textiles (clothing and other fabrics), and the application of coal-fired steam to factory production and transportation (locomotives and steamboats) took off after the War of 1812, when the U.S. had been temporarily cut off from British trade and became more self-sufficient. Because enslaved workers on southern cotton plantations weren’t paid, the overall cost of clothing made in northern and British textile mills was affordable — similar to how overseas sweatshops drive down wholesale costs today. Americans helped pioneer interchangeable parts and mass production in firearms, shoes, typewriters, and sewing machines. Improved agricultural implements led to more crops, moved around the country on a water highway of rivers and canals, the most famous and important being New York’s Erie Canal (built 1818-25). Most industry was in the North. Southern cotton fed northern textile mills, but only around 10% of factories were in the South, with most of those on the periphery of a vast agricultural area. While also boosting shipping, banking, and retail, cotton clothing was one big Atlantic economy with varying combinations of slavery/wage labor and manual labor/automation.

One could view the Civil War as a contest between a newer economy of factories, large family farms, and white wage labor versus a more traditional aristocracy in the South, where planters reinvested profits back into enslaved workers rather than machines while poor Whites made do on small family farms. The dynamic North prided itself as a land of opportunity while the South celebrated its stability and feudal ties to antiquity. The Civil War itself catalyzed industry by increasing railroad construction and demand for contractors to make weapons, sew uniforms, and slaughter meat for the Union Army. Post-war America confirmed the saying that to the victor goes the spoils, embracing the northern vision of industry, big banking, construction, family farming, and protective tariffs. Tariffs (import taxes) disrupted free markets, raising prices, but protected American industries from overseas competition, especially Europe, where manufacturers had access to cheaper labor.

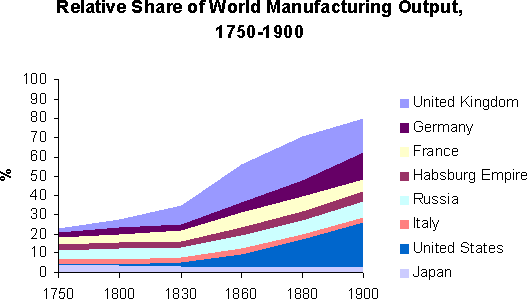

Fueled by hard-working immigrants, abundant natural resources, and innovation — both technical and managerial — the U.S. led the world in manufacturing by 1900. Cars we’ll cover later (Chapter 7) after they start having a more mainstream impact. In this chapter, we’ll focus on key sectors in this emerging market, including finance, electricity, communication, aviation, railroads, retail, steel, and oil. First, we’ll look at invention and innovation.

Innovation

Free markets create demands that spur innovation, but governments play an important role too, at a minimum establishing sound currency and protecting property rights while providing military protection and building infrastructure. They also provide a legal framework for innovation by guaranteeing inventors proprietary rights (short-term monopolies) for products they register with patent and trademark offices. The system doesn’t work perfectly because people still steal each other’s ideas but, without it, there’s even less motive for inventing other than for charity or tinkering. Patents have a long tradition in the West, dating back to ancient Greece and including the British colonies. The U.S. followed suit by passing its own Patent Act in 1790. These registrations benefit those willing to take time out from directly industrious pursuits to painstakingly develop new or better products.

Early U.S. history is littered with famous patent winners like Eli Whitney, Oliver Evans, Elias Howe, Charles Goodyear, and John Deere, who boosted productivity and created jobs for millions; though in the case of Whitney’s cotton gin, many of those jobs came without wages. Even Abraham Lincoln won a patent for a flotation device to help dislodge steamboats stuck on sandbars. Lincoln also worked as a patent lawyer, helping to sort out controversy over the mechanical reaper. The Kohler Company in Wisconsin made life healthier and more pleasant with patented enameled cast-iron “bubblers” (aka drinking fountains) and bathtubs that were really just repurposed hog scalders with four legs. British plumber Thomas Crapper held nine patents relating to the flush toilet, though, contrary to convention, he didn’t invent it. The rate of patent registrations picked up after the Civil War.

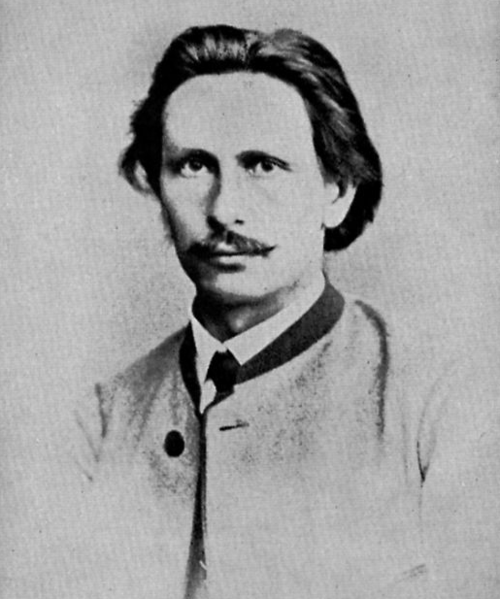

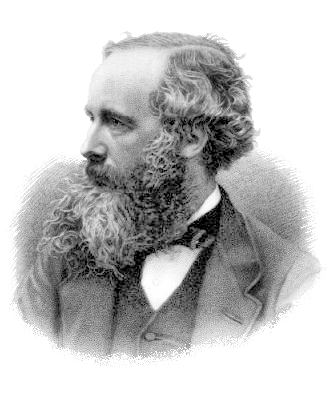

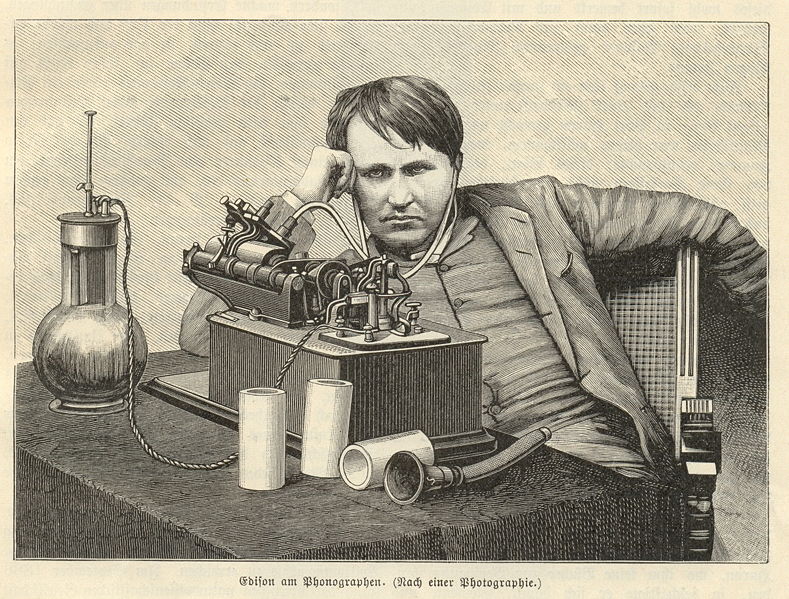

Inventor Thomas Edison (above) went so far as to create entire factories devoted to inventions in Newark, Menlo Park, and West Orange, New Jersey. You could say that he mass-produced inventions. The facility in West Orange, preserved as a National Historic Site, has been called the “Silicon Valley of the Industrial Revolution” because its productivity rivaled that of today’s Bay Area technology hub. Though a brilliant engineer, the formally “uneducated” Edison was arguably an even better businessman. He had a staff he called “muckers” that helped him come up with the light bulb, phonograph, rechargeable nickel-iron batteries, X-Ray, mimeograph, burglar/fire alarms, talking dolls, and movies in the span of a few years. They didn’t succeed 100% of the time, but they didn’t expect to, and Edison once said, “Failure isn’t a failure.” From failure, they learned new things they could apply to other projects. Their failed ventures with cheap iron ore, for instance, morphed into a profitable Portland cement business.

Menlo Park Lab of Thomas Edison Replicated in 1929, Dearborn, Michigan at Greenfield Village-Henry Ford Museum

Their relentless work paid off. Edison registered 1,093 patents, documented here at Rutgers’ Edison Papers Project. He bought others’ patents and described himself as “more of a sponge than an inventor.” Like many geniuses, he had a knack for applying and borrowing ideas. Big cities were then building networks to pipe coal-gas for lanterns, cooking, and heating. Unlike other inventors, who were testing light bulbs hooked to batteries, Edison foresaw that electricity would someday be sent across wires directly into homes and businesses, similar to the way coal-gas was distributed in his time. He developed an appropriate carbon-filament light bulb for that high-voltage distributed energy system before it emerged. Yet, the most important thing Edison invented was a system of inventing: a research and development (R&D) lab with a staff earning shares in the company while tapping others’ ideas.

The romantic notion of geniuses working in isolation is a myth, to begin with. Creators in every field borrow from others. Geniuses never work in vacuums, but are ingenious at recombining networked ideas. That’s how the winepress inspired Johannes Gutenberg’s movable-type printing press in the 15th century, how Samuel Colt’s breakthrough for the revolver came at sea observing the ratchet and pawl mechanism on a sailing capstan in the 1830s, and why Motown Records’ Berry Gordy ran his Detroit studio like the Ford assembly line he’d worked on in the 1960s, churning out hits instead of cars. That’s also why the light bulb couldn’t have been invented in the Middle Ages, how sewing machines led to motion pictures and why, now, we can only proceed piecemeal toward future inventions. Inventions build on each other and the most advanced civilizations have always been traders because interaction triggers innovation. Igor Stravinsky took this notion a step too far, though, suggesting that “good composers borrow, great ones steal.”

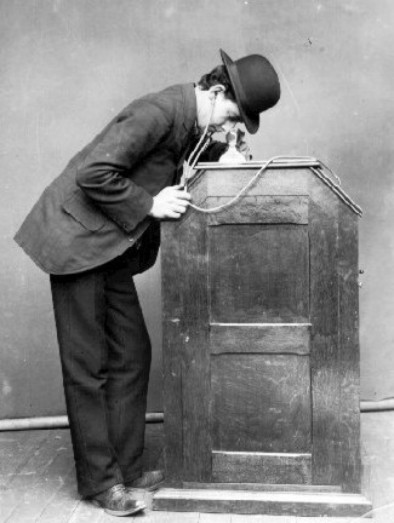

Motion pictures was one idea Edison pilfered, based on Eadweard Muybridge’s 1879 Zoopraxiscope. Muybridge built the device to help California Governor Leland Stanford win a $25k bet that horses’ hooves all leave the ground simultaneously when they gallop. Edison was locked in a patent contest with Frenchman Louis Le Prince over claim to the first motion picture camera when Le Prince disappeared off a train, never to be heard from again. After having seen Edison’s Kinetoscope in Paris, the Lumière brothers of Lyon, France invented the Cinematograph that used perforated rolled film for projection, borrowing the “grab advance” mechanism from sewing machines. Le Prince’s first movies, shot in Leeds, England in 1888, pre-date those of Edison and the Lumières by five years. Kodak founder George Eastman’s invention of rolling film — a by-product of developing compact, user-friendly cameras for the mass market — made all these subsequent applications possible.

Inventions are rarely an easy thing to track to any one person. Cars, planes, and flush toilets have the same tangled histories as film. Normally people point to individuals in their own country to describe an invention that was really a difficult-to-track, cross-fertilizing global process.

Dozens of inventors worked on light bulbs, for instance, hoping to improve on the natural gas lights and sperm oil and kerosene lamps then in use. In 1878, forty years after the first bulb patent, Edison was trying to find a filament that didn’t burn out too quickly (metal conducts electricity too well). According to legend, he happened upon carbonated cardboard by tearing off a piece of a box that was sitting on his table. Hiram Maxim also claimed credit for the light bulb but the patent office disagreed, so he had to settle for the machine gun, mousetrap, menthol inhaler (for asthma) and curling iron, along with researching how plane wings impact lift (more below). With its familiar vacuum-tube bulb and standard 27mm screw base, Edison’s incandescent light bulbs provided 1200 hours of light for the same cost as seven hours from a spermaceti lamp. However, the incandescent bulbs were less efficient than Peter Cooper Hewitt’s 1890 compact fluorescent lamps and, in 2007, the Bush administration mandated a transition to the more expensive but longer-lasting CFLs. LED bulbs are even more efficient than CFLs and don’t contain mercury.

Artificial light allowed factories to operate around the clock, for people to study and read at all hours, and made going out at night safer, boosting restaurants and any business or entertainment associated with nightlife. Prior to indoor lighting, people sat around fires all their lives, inhaling so much smoke that by middle age their lungs looked like what we’d see today only in a coal miner or heavy smoker. Candles reeked because they were made from animal fat.

Phonographs were another way that Edison changed people’s lives, allowing people to hear records of all styles and from all eras and regions. Previously, the only music anyone ever heard was live. Live music is great but, for most people, it didn’t amount to much variety. Phonographs were initially used more for recording than playback, with early uses including stenography (taking dictation) and answering machines. Edison was interested in the Spiritualism movement and even hoped that albums would be able to record and play voices from beyond the grave, like today’s purported EVP. He designed his Psychophone for that purpose.

Motion pictures, based on Edison’s Vitascope patent, were originally conceived as cheap carnival attractions, with brief five-minute “keystone cops” type films. But movies flowered into an entire industry and art form in the early 20th century, led by director Alice Guy-Blaché. America’s film industry started across the Hudson River from New York City, with Edison’s own revolving “Black Maria” soundstage, Universal Studios, and Fox in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Other companies popped up in New York and Philadelphia, but Edison owned the patent for 35mm film. Since southern California was near deserts ideal for shooting westerns and close enough to the Mexican border to escape the Edison Trust’s patent lawyers/detectives (mainly vandals), an orange grove called Hollywood emerged as the industry’s American base. Cecil B. DeMille and D.W. Griffith were among the first directors to make the trek west.

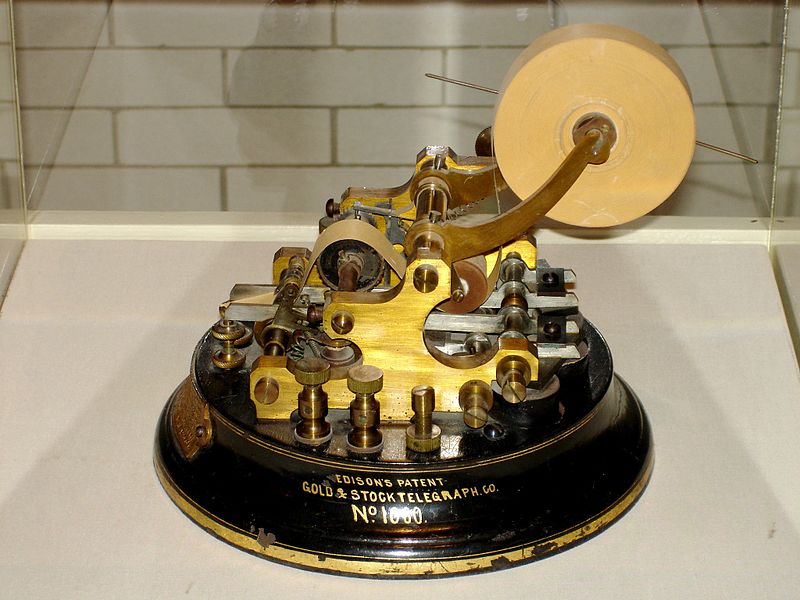

Finance

Financiers funded inventors who, in turn, impacted finance. One of Edison’s first inventions was the stock ticker, an accessory to the telegraph that sent up-to-date stock prices all over the country — an early version of today’s fintech. This helped centralize major markets in New York (stocks) and Chicago (commodities), whereas earlier trading occurred haphazardly around the country. New York journalist Charles Dow then codified and cataloged price histories, allowing people to study charts in an (arguably futile) attempt to divine patterns or guess future directions for stock prices now called technical analysis. He also created an index of top railroads, the biggest firms in America at the time and, in 1896, another of non-transportation companies known as the Dow Jones Industrials: thirty top companies that served as a bellwether of the market’s direction. The Dow inspired the broader S&P 500 and now indices for every imaginable sector, most with funds tracking them.

Americans had historically preferred bonds to stocks — Henry David Thoreau’s “joint stocks and spades” that were seen as too volatile and susceptible to manipulative schemes that emptied the pockets of unwary investors. Dow’s index and daily paper, the Wall Street Journal, didn’t eliminate these problems altogether, but seemingly tamed the markets enough to entice broader participation. This boosted public companies because they could raise more funding and spread more risk by selling public shares than by simply borrowing from banks or individual backers known today as angel investors or venture capitalists. That enhanced innovation. As we’ll see in the next section, competition between financiers spilled over into competition among inventors.

Electricity

Funding played a big part in the War of the Currents, an engineering and public relations (PR) contest over which type of current, alternating or direct, would power America’s new electrical grid. The story illustrates how multiple inventors work on similar things simultaneously, how history could’ve easily gone in different directions, and how engineers’ competition hinged on their respective investors.

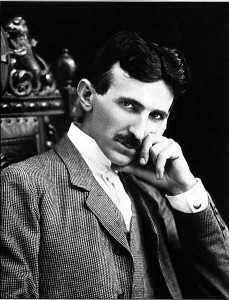

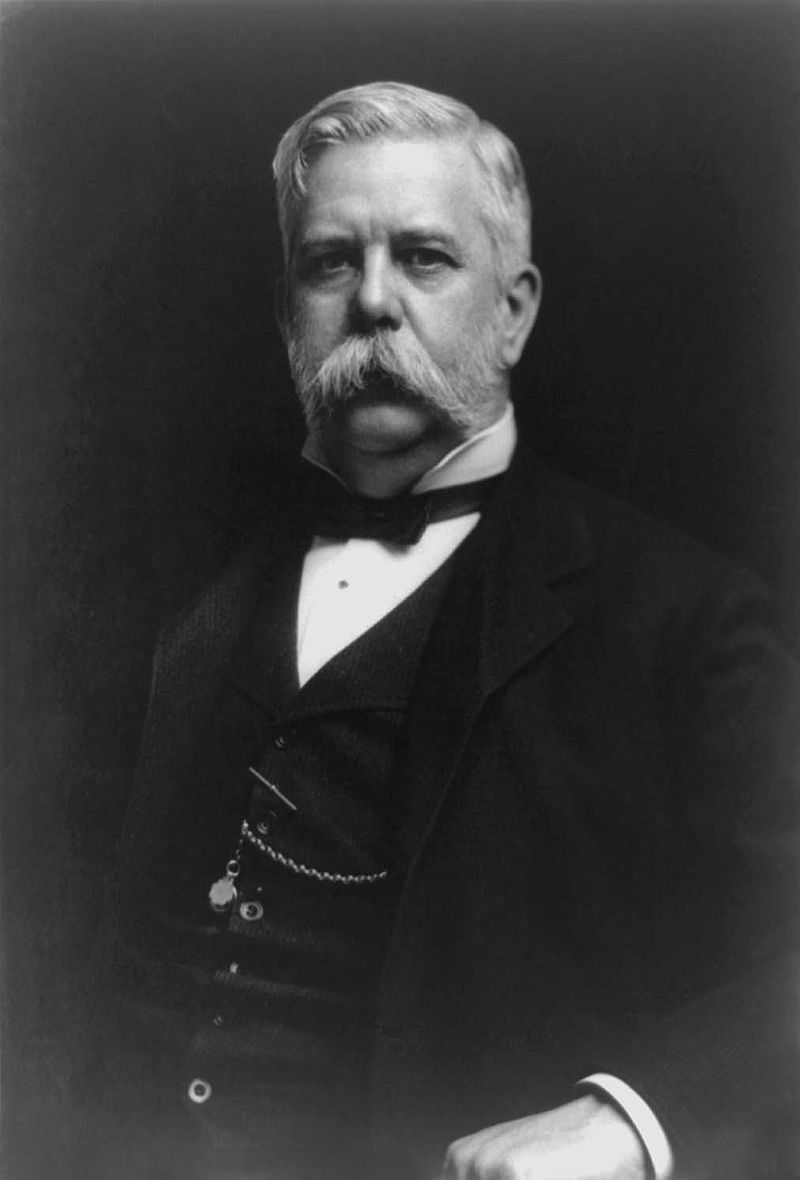

Edison, along with his financial backer J.P. Morgan and their corporation, Edison Electric Light Co., favored the direct current (DC) approach. Edison’s former employee Nikola Tesla and Tesla’s patron, George Westinghouse, backed alternating current (AC). Westinghouse liked that its voltage could be “stepped up” or down in transformers and built a small distribution network in Pittsburgh. Having developed important railroad patents, Westinghouse could mentor Tesla in bringing inventions to market. Pioneered by Michael Faraday and Hippolyte Pixii, AC was more promising for the grid since DC loses power over distance and, at the time, was intended mainly just for light bulbs rather than other machines and appliances. Alternating current was stronger but more dangerous.

Both sides tried to convince the public that their system was safer and that the other would lead to unnecessary deaths, as the Current Wars intertwined with advent of the electric chair. John D. Rockefeller, who dominated the kerosene market, had tried such shenanigans on Edison to scare people away from light bulbs. Edison’s staff invented the electric chair ostensibly as a humane alternative to lynching criminals. However, with Edison consulting and journalists observing, New York’s Auburn Prison set the prototype chair to torture convicted murderer William Kemmler before killing him. Edison hoped to create bad PR for AC just as the two companies vied to win the contract for a large generating station at Niagara Falls, New York that would power much of the Northeast. Instead, the cynical ploy backfired and damaged Edison’s reputation.

Westinghouse wouldn’t have been able to under-bid J.P. Morgan, but Tesla generously agreed to forfeit all his AC patent royalties. That saved Westinghouse enough money that he won the bid to electrify the aforementioned Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, which in turn won them the Niagara bid. The country’s first power plant, Edison’s Pearl Street DC station in lower Manhattan, that powered Wall Street and Morgan’s own home, gave DC an early edge. But the AC system Tesla and Westinghouse pioneered at the Niagara Falls hydropower plant near Buffalo proved more efficient for a decentralized system of stations connected across the country with medium-length power lines. Tesla imported pole-mounted transformers that powered down AC’s 100k volts to the 110v or 220v used in homes, making it safer. Today, ~99% of America’s grid carries AC. Tesla, in effect, developed the grid system that powers America. Still, many household items run on converted DC, including computers (laptops, desktops), phone batteries, and LEDs, and electric cars are DC. Televisions use AC. Edison’s high-voltage direct current lines (HVDC) are mounting a comeback because they’re practical for transmitting solar and wind power over long distances — a necessary feature to overcome the intermittency drawback of solar and wind. Edison and Tesla both predicted the advent of solar energy. There’s also talk of smaller, decentralized/distributed DC power stations.

The AC grid was arguably the most underrated engineering project in American history and created thousands of jobs for line-workers and electricians. A Popular Mechanics poll of engineers rated it ahead of the 1969 moon shot. It was dangerous work, though, especially for those used to low-voltage telegraph/telephone wires. In the late 19th century, career linemen suffered a death rate of nearly 50% — double that of soldiers in the Civil War. Later, J.P. Morgan ruthlessly threatened Westinghouse with lawsuits Westinghouse couldn’t afford to extort Tesla’s AC patent rights for himself. Thus, the Current Wars winner was the financial loser and vice-versa, and Edison built his own AC power grid in California between Sacramento and the Folsom Power House. Then Morgan edged Edison out of his own Edison Electric Co. by buying up shares and created General Electric to dominate the future market in generators and appliances. General Electric was the only modern company from the original Dow Jones Industrial Average until Walgreen’s replaced it in 2018.

Tesla rivaled Edison as an inventor and they shared a personal backstory behind the Current Wars. Born at midnight during a thunderstorm in Croatia in 1856, Tesla had a lifelong fascination with storms and electricity. He showed signs of genius at a young age, constructing toys powered by insects. After working in Edison’s Paris office, Tesla immigrated to America in 1884 to work for him, but they had a falling out over approach and money. Edison always had his eye on practical application, whereas for Tesla science was an artform, spurred by fantastic images in his head. Edison called Tesla a “poet of science.” According to Tesla, Edison challenged him to improve his “dynamo” (electrical) motor designs by promising, “There’s fifty thousand dollars in it for you, if you can do it.” When Tesla solved the problem and asked for his money, Edison dismissed him and said, “Tesla, you don’t understand American humor.” Tesla refused a smaller pay raise and quit. The War of the Currents is a good example of how overlapping ideas, patents, financing, and personal rivalries impact which direction technology takes us.

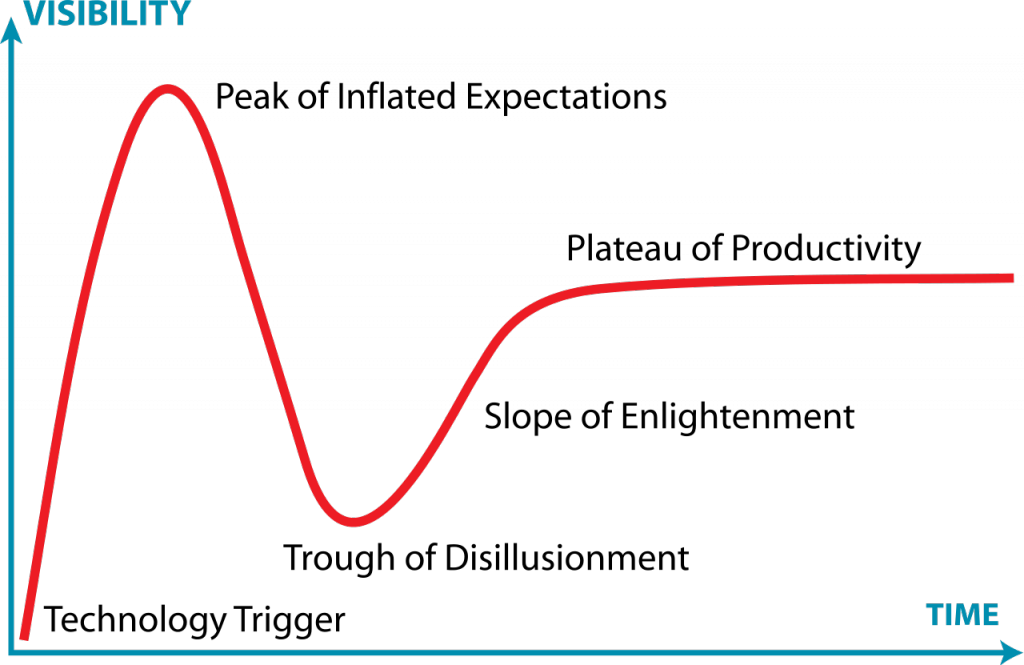

Electricity also exemplifies the difference between innovation and the widespread, practical application of technology. Nearly half a century passed between Edison and Tesla’s initial breakthroughs and the availability of electrical power for most American homes, businesses, and factories. Such was the case in steam technology, antibiotics, and robotics. Be wary of the “trough of disillusionment” phase after the initial hype cycles depicted in the diagram above regarding biotech, nanotech, T-Cell therapy, 3-D printing, improved robotics, geoengineering (e.g. carbon capture or solar radiation modification), and more ambitious forms of renewable energy like fusion. The solar energy that Tesla and Edison enthused about in the 1880s wasn’t efficient and cost-effective enough for widespread use until the 2010s. Long periods of dashed hopes could follow initial enthusiasm before today’s innovative technologies gain any traction or have a measurable impact. That’s the kind of insight you can only get with historical perspective. But also be wary of catchy concepts like hype cycle, which aren’t a consistent pattern that historians exhaustively researched so much as a theory market analysts trotted out for clients to underscore their investing insight or optimism. Many emerging technologies succeed right away or fail altogether, while others follow some variation on the pattern illustrated above. No one really knows, for instance, what will happen with cryptocurrency because the future is a blank slate with too many unforeseeable contingencies. Likewise, in 2023, media was abuzz with predictions about how quickly and dramatically artificial intelligence would change the world. That hasn’t materialized yet, but that doesn’t mean it won’t and isn’t starting to already.

Tesla invented generators, conductors, and engines that ran on AC current, including the induction motors used in today’s factories, appliances, and cars. Since these engines’ rotating magnets don’t touch, they generate less friction, heat, smell, and smoke than DC motors. Tesla also worked on neon and wireless fluorescent lights (what he called “cold lights” because their coil-lit gasses don’t heat up), turbine engines, speedometers, magnetic recording and data storage, loudspeakers/headphones, and helicopters. In a failed effort to communicate with Martians, Tesla laid the groundwork for radio, the first “wireless.” The U.S. Patent Office credited him for his work on radio posthumously in 1943 because Guglielmo Marconi utilized so many of his patents. Tesla died with over 700 patents. The real groundwork for radio was Scotsman James Clerk Maxwell’s discovery of electromagnetism in the 1860s, based on mathematical models rather than hands-on work (many things have been predicted by math before they were seen or discovered, such as black holes). Maxwell was first to understand that light, electricity, and magnetism are all waves. Albert Einstein said, “I stand not on the shoulders of Isaac Newton, but on the shoulders of James Clerk Maxwell.”

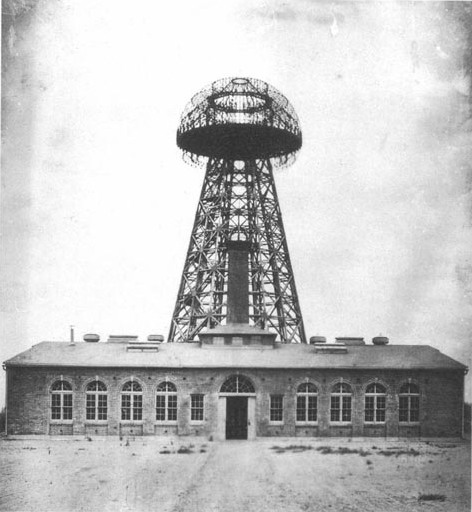

Tesla also invented remote control, demonstrated on toy boats, and worked on a death ray similar to today’s tasers. He envisioned solar and geothermal energy, claimed to have an earthquake machine that could bring down New York City, and hoped to develop a machine to control the weather. One reason for Tesla’s renewed popularity is that he envisioned a system of beacons similar to today’s cell phone towers that would eventually replace landlines. From his Wardenclyffe broadcast tower on Long Island (right), he hoped to transmit wireless audio and video around the globe but his hopes weren’t realized and he sank into debt, burning through 150k of J.P. Morgan’s dollars before giving up, at which point Morgan might’ve wished he’d left Tesla with Westinghouse after the Current Wars.

Tesla also invented remote control, demonstrated on toy boats, and worked on a death ray similar to today’s tasers. He envisioned solar and geothermal energy, claimed to have an earthquake machine that could bring down New York City, and hoped to develop a machine to control the weather. One reason for Tesla’s renewed popularity is that he envisioned a system of beacons similar to today’s cell phone towers that would eventually replace landlines. From his Wardenclyffe broadcast tower on Long Island (right), he hoped to transmit wireless audio and video around the globe but his hopes weren’t realized and he sank into debt, burning through 150k of J.P. Morgan’s dollars before giving up, at which point Morgan might’ve wished he’d left Tesla with Westinghouse after the Current Wars.

Tesla was nuttier than a tree full of squirrels. He claimed to be in love with a pigeon in New York’s Bryant Park and, sadly, said he never recovered from the pigeon’s death. He was a germaphobe and couldn’t touch women’s hair. Tesla wrote, “I do not think there is any thrill like that of the inventor when he sees some creation of his brain unfolding to success. Such emotions make a man forget food, sleep, friends, love, everything. It is a pity, too, for sometimes we feel so lonely.” The eccentric inventor performed all tasks in groups of three or nine.

The U.S. government took his claims of earthquake machines and death rays seriously enough to rope off his room on the New Yorker Hotel’s 33rd floor and help themselves to his files and equipment upon his death in 1943. At the height of WWII, they suspected other countries would beat them to the punch if they didn’t. Today, Elon Musk’s company bearing Tesla’s name is marketing electric cars and batteries recharged by solar power. An induction motor 6x lighter and nearly 2x as powerful as a comparable internal combustion engine powered the Tesla Model 3 (cooling passively precludes the need for a radiator, fan, and water pump).

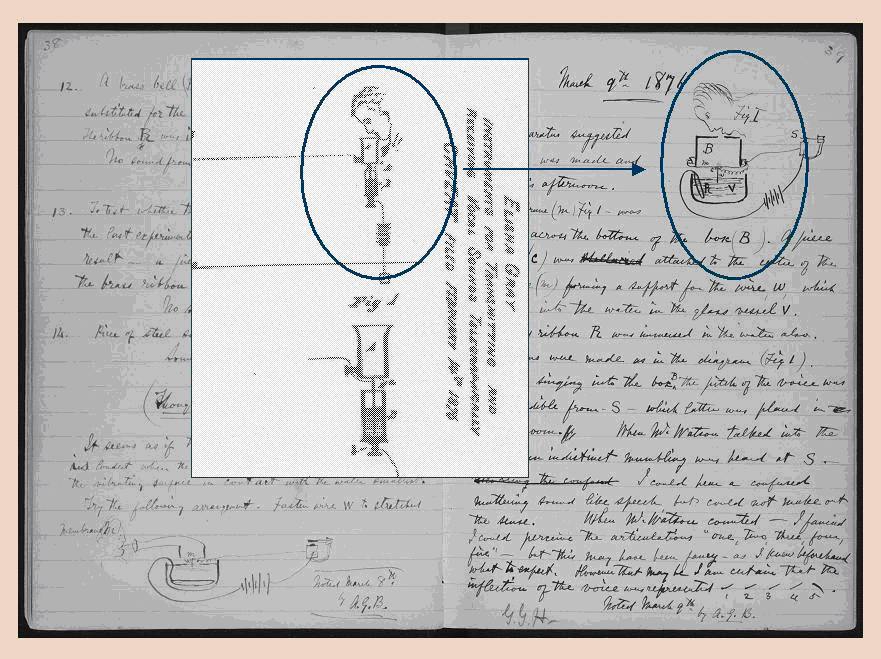

Portions of Elisha Gray’s Patent Caveat of February 14th and A.G. Bell’s Lab Notebook of March 8th, WikiCommons

Communication

Another inventor who took advantage of the patent system, beating rival Elisha Gray (Western Union) to the registration office on the same day, was Alexander Graham Bell. As the image above suggests, some historians suspect that Bell stole his key idea from Gray (controversy) and a patent clerk testified that Bell bribed him $100 to see Gray’s application. Gray’s key breakthrough was a liquid transmitter whereby a needle would vibrate in battery acid to modulate current passing through it. This was a key patent debate as Bell went on to form his namesake conglomerate that monopolized the country’s phone lines until 1984 — parent of today’s “Baby Bells” AT&T, Verizon, and CenturyLink. Bell said the clerk was lying and the Supreme Court narrowly ruled in Bell’s favor. Later, television would experience a similar, contested patent war of its own between Philo Farnsworth (Philco) and David Sarnoff (RCA).

Another inventor who took advantage of the patent system, beating rival Elisha Gray (Western Union) to the registration office on the same day, was Alexander Graham Bell. As the image above suggests, some historians suspect that Bell stole his key idea from Gray (controversy) and a patent clerk testified that Bell bribed him $100 to see Gray’s application. Gray’s key breakthrough was a liquid transmitter whereby a needle would vibrate in battery acid to modulate current passing through it. This was a key patent debate as Bell went on to form his namesake conglomerate that monopolized the country’s phone lines until 1984 — parent of today’s “Baby Bells” AT&T, Verizon, and CenturyLink. Bell said the clerk was lying and the Supreme Court narrowly ruled in Bell’s favor. Later, television would experience a similar, contested patent war of its own between Philo Farnsworth (Philco) and David Sarnoff (RCA).

As a teacher of deaf students, Bell thought the Morse Code system of tapping used in electric telegraphs could be improved by assembling an artificial ear on either end, though the design was far simpler (cameras were likewise based on eyes). At first, he experimented on the ears of cadavers. Phones used the same wires already up for the telegraph and were initially thought of as something only the government, police or delivery boys would have any use for. Ironically, Bell didn’t like a phone in his own study because he found them intrusive. Just as people couldn’t see any broader application of movies beyond the Nickelodeon machines at fairs, they didn’t envision that people would want to talk on the phone just to catch up. In 1876, President Rutherford B. Hayes remarked, “It’s a great invention but who would want to use it anyway?” A visionary he wasn’t.

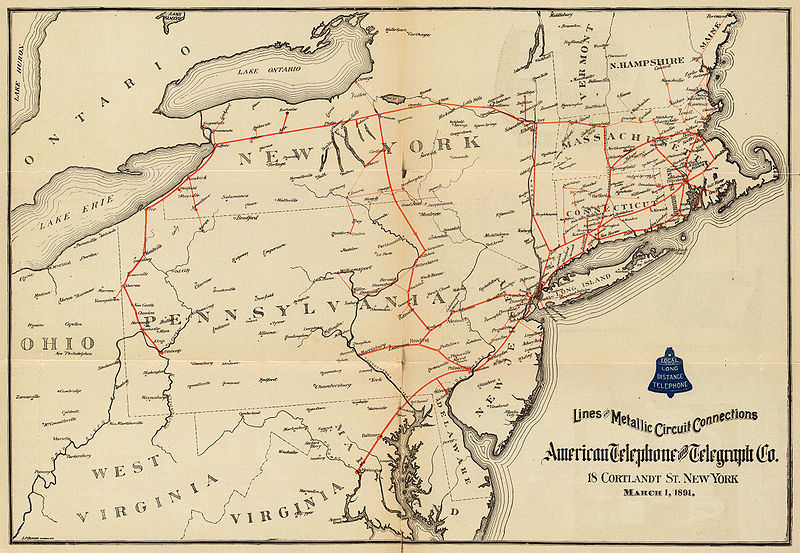

Lines and Metallic Circuit Connections, American Telephone and Telegraph Co. (i.e. Bell Telephone Co.), 1891

One inventor did foresee a problem with calling people who weren’t home. As mentioned, Edison invented the phonograph partly as a telephone messaging system. Edison also popularized “hello,” which caught on instead of Alexander Graham Bell’s “ahoy” as a greeting among callers (hello isn’t a common greeting in England, but there are Dutch and German variations). Like Edison, Bell had an eye for talent: a member of Bell’s 1908 aviation research team, Glenn Curtiss, was a primary founder of America’s aeronautics industry.

Aviation

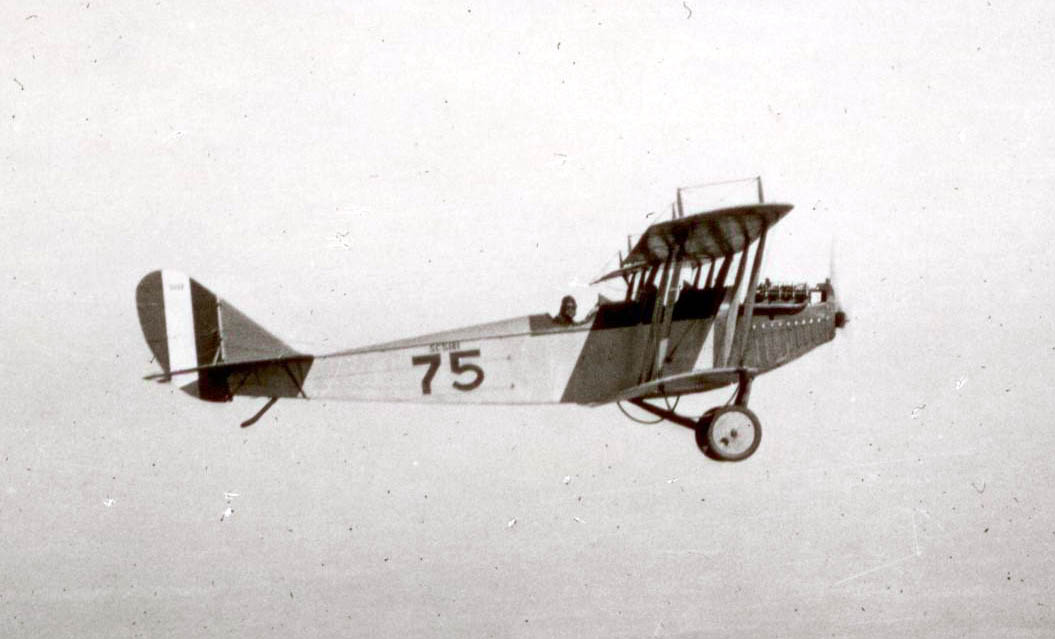

Contrary to the quote at the top of the chapter, Edison was wrong that planes (heavier-than-air craft) would never fly. And like other inventions, the engineers hoping to prove him wrong were spread around in different countries, including France, Germany, and the United States, where Michigan’s August Moore Herring built an unwieldy motor-powered glider in 1898. Two American bicycle mechanics, Orville and Wilbur Wright, tried giving the wings flexibility and stability, like those of a bird (wing warping). According to legend, this insight on balance came from twisting a cardboard bike inner tube box and seeing how the ends turned in opposite directions. If the story about Edison’s filament inspiration is also true, cardboard boxes were quite influential in the 19th century. The Wrights used their bikes, too, adapting steering handlebars to their planes and by testing wings on wheels attached to the front of bikes. With their shop staff’s help, they built a lightweight aluminum crankcase for their engine. The Wright Brothers tested kites, then gliders that they boosted with a 4-cylinder, 12-horsepower engine that connected to twin propellers with a sprocket chain drive similar to a bike.

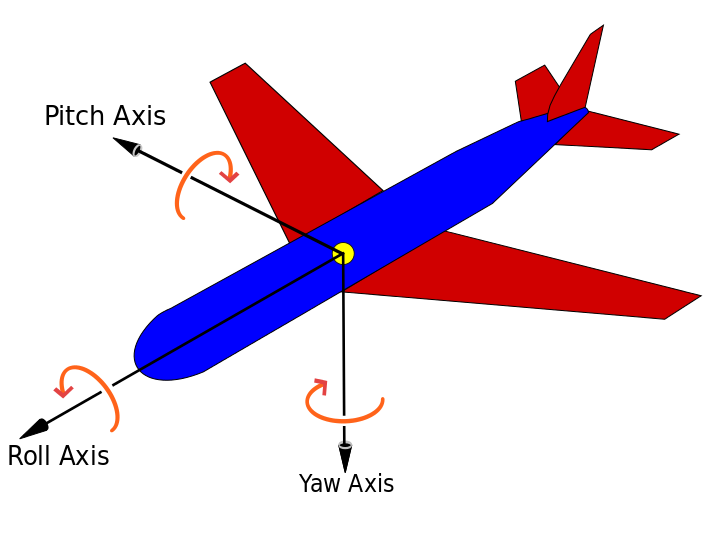

In 1903, after several trials, Wilbur got their namesake Wright Flyer off the ground for 59 seconds and crash-landed onto the sand dunes of Kill Devils Hill south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Theirs’ was the first sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air craft (not a balloon or glider). The Wrights cleverly figured out how to simultaneously stabilize three dynamics that powered flight must overcome: pitch, roll, and yaw: up-and-down pitch with a forward elevator, lateral roll with wing-warping by manipulating the angles of the left and right wings, and yaw (or sideways, horizontal spin) with a rear rudder. Their rudder was connected to the cables that warped the wings. Yet, the Wrights didn’t get much credit at the time because few people saw the flight. They wanted it that way because they didn’t want anyone stealing their designs, but that concern for patent protection proved to be a double-edged sword. Even their hometown newspaper in Dayton, Ohio didn’t recognize them as flying the first plane. The Wrights avoided air shows.

In 1903, after several trials, Wilbur got their namesake Wright Flyer off the ground for 59 seconds and crash-landed onto the sand dunes of Kill Devils Hill south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Theirs’ was the first sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air craft (not a balloon or glider). The Wrights cleverly figured out how to simultaneously stabilize three dynamics that powered flight must overcome: pitch, roll, and yaw: up-and-down pitch with a forward elevator, lateral roll with wing-warping by manipulating the angles of the left and right wings, and yaw (or sideways, horizontal spin) with a rear rudder. Their rudder was connected to the cables that warped the wings. Yet, the Wrights didn’t get much credit at the time because few people saw the flight. They wanted it that way because they didn’t want anyone stealing their designs, but that concern for patent protection proved to be a double-edged sword. Even their hometown newspaper in Dayton, Ohio didn’t recognize them as flying the first plane. The Wrights avoided air shows.

Consequently, Glenn Curtiss stole the spotlight by piloting the first public demonstration in 1908 for Scientific American magazine, flying his June Bug for two minutes and nearly a mile outside Stony Brook, New York. The Wrights’ biggest concern for patent theft was Edison, but they turned down an offer from Curtiss to improve their engine for the same reason. Eventually, the Wrights won Patent #821,393 for their “flying machine,” but their monopoly on warped wings only inspired Curtiss to improve on the idea. Instead of adjustable wings, he attached flaps (French: ailerons) onto fixed wings and boosted power with his 40-horse engine. Fixed-wing planes won out just as alternating current did in the Current Wars.

When the Wright Brothers agreed to showcase their own fixed-wing plane in 1908, they had mixed results. One flight crushed Curtiss’ record, staying aloft for over an hour, but another wrecked after its propeller shattered, seriously injuring Orville and killing Army Lt. Thomas Selfridge. They still won the initial U.S. Army Signal Corps contract they were bidding on, but Curtiss was in their heads. They were so obsessed with protecting their patents that they spent more time in court than their shop and aviation passed them by, even as they won royalty suits and twice bankrupted Curtiss. Journalist Clive Irving wrote, “It’s as though Steve Jobs, having delivered the original 1984 Macintosh, had stopped right there.” Yet, we should also remember that securing patents was what motivated these pioneers in the first place, so patents have a mixed effect, mostly positive.

Curtiss got advice from the legal team of automaker Henry Ford, himself no stranger to patent wars, but time-consuming legal battles stifled American aviation while Germany made strides leading up to WWI. When war broke out, the government had to loosen up patent restrictions because, after Wilber’s death, Orville couldn’t fill the demand for planes. Germany, meanwhile, had 50k planes before the U.S. entered the war in 1917. Curtiss built a base in San Diego to train Army and Navy pilots and sold Uncle Sam 7k “Jenny’s” (JN-4), the surplus of which supplied the 1920s barnstorming craze.

Curtiss, along with William Boeing, turned aviation into a profitable business. Though only educated through the 8th grade, Curtiss got interested in mechanics working for Eastman Kodak. His interest in cameras and stencils eventually gave way to bicycles and motorcycles (Curtiss was a record-holding “Hell Rider” racer), and then to airplanes. Alexander Graham Bell considered Curtiss the “greatest motor expert in the country” but he also had a savvy head for business, earning millions even after his two bankruptcies, and his background as a daredevil prepared him to pilot his own designs. Curtiss later helped the U.S. keep pace with Japan in developing seaplanes and “flat-tops” (aircraft carriers) critical during and after World War II.

After the three erstwhile bicycle mechanics died, their companies merged into Curtiss-Wright (est. 1929), a leading contractor during WWII that is still around today. While planes didn’t gain significant commercial or military importance prior to WWI, the postal system used them for air mail in the 1920s and barnstormers entertained the public, keeping some manufacturers and pilots employed. In 1933, Boeing introduced the 247, the first metallic passenger liner.

Early aviation is a good example of most inventions’ messy early histories. Engineers and lawyers alike have to work out kinks, the public and leaders have to buy in, and companies and organizations have to “scale up.” The World Health Organization, for instance, had to implement a vaccine globally to wipe out smallpox which, in its own way, was as impressive as Edward Jenner inventing one in 1796 (and likely couldn’t happen again anytime soon). Likewise, it was a long way from the Kitty Hawk rising above the sand dunes momentarily to us hopping on Southwest for an easy jaunt to Las Vegas, let alone the Space Shuttle. Stay tuned, as we’ll return to aviation and aerospace in future chapters.

Rail

Rail

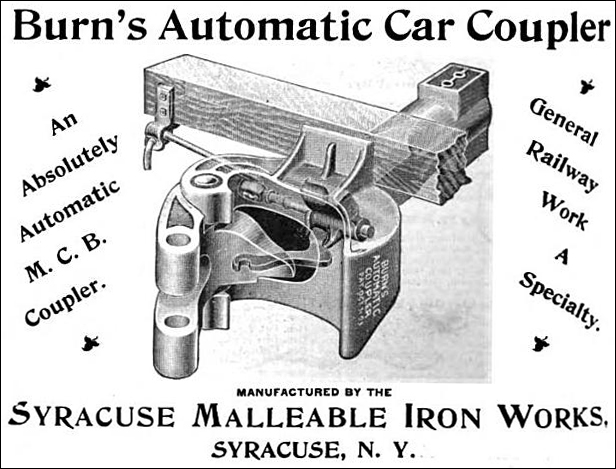

Trains, not planes, were the dominant mode of transportation in the Industrial Revolution’s post-Civil War phase. Investments and ingenuity accelerated all the major industries, but none more so than the “iron horse.” The English invented trains in the early 19th century and they quickly made their way to America. Their impact was limited prior to the Civil War, though, because of mechanical drawbacks and no agreed-upon width for the distance between the rails, or gauge. Cars were difficult to stop without any braking system other than pure friction as brakemen pulled on levers, and men charged with hooking the cars together could be squashed between. George Westinghouse’s application of hydraulics (air pressure) to braking systems improved the former while automatic couplers, aka “knuckles,” solved the latter. Westinghouse contributed to both railroads and electricity, as we saw above.

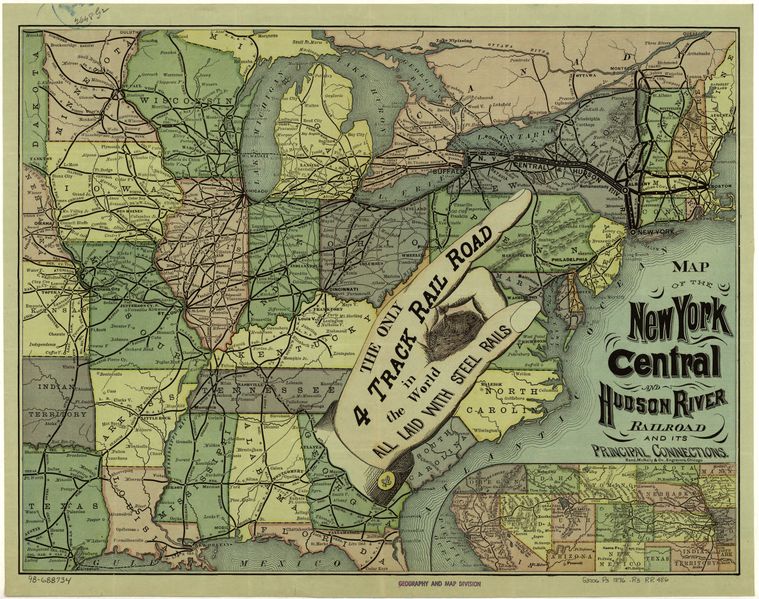

During the Civil War, the North agreed on the standard gauge of 4′ 8.5″ (the origin of that width is a story in its own right, but George Stephenson, an early English steam locomotive inventor, first suggested it). The common gauge enabled an integrated system of rails to connect, leading to the advent of freight companies. Before that, individual companies bought their own small lines and rolling stock. In the late 19th century, these freight networks were the heart and soul of the American economy and are still vital today, which is why the government intervenes to arbitrate their labor disputes to avoid strikes. Trains not only moved products around, allowing for the growth of large companies, but the railroad companies themselves were also primary customers for steel (rails and cars), timber (ties and cars) and coal (to fire the steam engines). They also made men rich. The richest of all was former shipping magnate Cornelius “the Commodore” Vanderbilt, who consolidated eastern railroads, including the New York Central and built Grand Central Station. Vanderbilt’s preferred tactic was inflicting enough temporary damage on his rivals to lower their stock price, then scooping up enough shares at a discount to become majority shareholder. He no doubt had an Edison stock ticker on his desk.

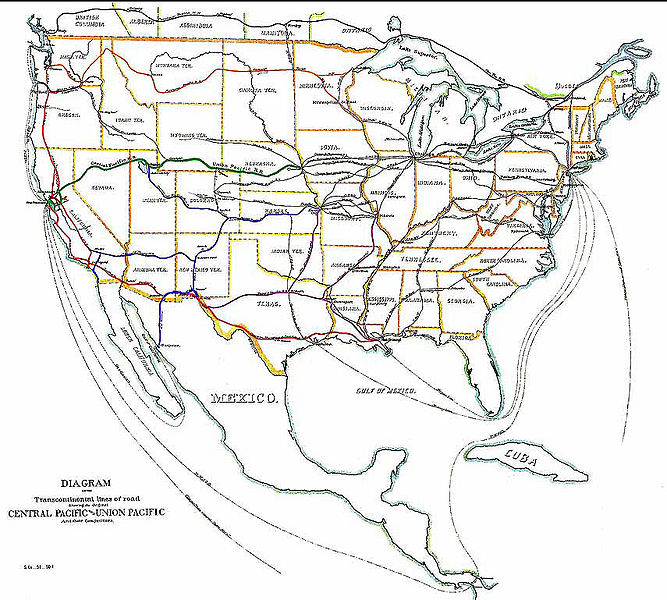

When Abraham Lincoln arrived in Washington in 1861, he saw the U.S. as, in effect, three countries: the North, the Confederacy, and California. California was already a state, but developing an economy all its own, far removed from the line of settlement in the Midwestern prairie states. Most of the Plains and mountains in between were unsettled by Euro-Americans, except for Mormons in the Great Basin. The North and South squabbled for years over where to best build a transcontinental route and, even aside from politics, multiple, unavoidable mountain ranges made for challenging engineering. When the South left the country in 1861 the Union could do as it pleased, and Lincoln and Congress immediately set upon building a track connecting the Midwest to California.

Lincoln doubled as a railroad lawyer along with being a politician, and his administration thought the free market offered insufficient incentive for large-scale infrastructure. James Hill later built the Great Northern Railway with minimal public support, but the near-consensus at the time was that tracks would cost more to build than any one company could ever recoup with freight or passenger service, at least within the lifetimes of original investors. So the government offered loans, land grant subsidies, and exclusive rights-of-way for companies that could lay the most track. Based on similar logic, the national government also built out the electrical and telecommunications grids, paved the interstate highways, invented the Internet, built bridges and dams, and subsidizes rural broadband. Unlike the later projects, the transcontinental project was plagued by corruption, bribes, kickbacks, and shoddily built lines.

Nonetheless, the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 culminated in the first western route from Omaha, Nebraska to Sacramento, California by 1869. Since it took a while to build the bridge from Omaha across the Missouri River to Council Bluffs and the “Iowa Pool” connecting to Chicago, the first operational western route went through Kansas City. The Central Pacific Railroad built west from California with Chinese coolie laborers, while the Union Pacific used military-style discipline to drive ex-enslaved, soldiers, and immigrants to lay ties and pound spikes across the Plains and through South Pass in the Rockies. It wasn’t easy or fast work. Each side had progressed only about fifty miles by Lincoln’s death in 1865. But the pace picked up in the east after the war, and the Chinese were better able to blast tunnels through the Sierra Nevada Mountains after Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel invented dynamite in 1867, a more manageable way to stabilize nitroglycerine. By 1900, five routes crossed the west, including James Hill’s, all used today by freight and Amtrak.

Meanwhile, a precursor to Western Union built a transcontinental line of its own, connecting a telegraph wire from the eastern U.S. to San Francisco in 1861. By the time Lincoln died, the continental U.S. or “Lower 48” we see today was on its way toward becoming an integrated country. That wouldn’t have happened, at least not in the same way, without the Union winning the war and building the railroads and telegraph. The most important connection in realizing Lincoln’s dream ended up being the Santa Fe Railway (ATSF) that connected southern California to the Midwest and East. Without that link, neither Chicago nor Los Angeles/Hollywood would’ve grown into huge cities.

Railroads were America’s first big industry. Aside from creating a huge labor market, they led to other industries like traveling salesmen, circuses, vaudeville acts, national parks, and lecturers like the “Great Agnostic” Robert G. Ingersoll (right), who was known to clerics as “Injuresoul” but who introduced audiences to Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory and whose fans included Clara Barton, Frederick Douglass, W. C. Fields, Andrew Carnegie, Margaret Sanger, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, and Thomas Edison. Ideas, information, and entertainment spread on rails along with goods and commerce.

Traveling “Big Top” circuses, with their sideshows and menageries, provided a colorful experience that Americans from different regions could share and introduced many people to electricity, jazz/ragtime, trapeze artists, African animals, and movies, though the latter eventually contributed to their demise. Empresarios like P.T. Barnum and the Ringling brothers were among the country’s biggest business tycoons and among the first to take advantage of trains. This map shows how Barnum’s footprint expanded when he put his circus on rails in 1872:

James Hill’s son Louis Hill of the Great Northern Railway built chalets in Montana’s Glacier National Park, nicknamed “America’s Switzerland.” Railroads built park lodges and hired artists to promote tourism at Yosemite (Southern Pacific), Yellowstone (Northern Pacific) and Grand Canyon (Santa Fe), hoping to augment their freight business with more passenger traffic. Time Zones, originally the idea of Benjamin Franklin and later legalized during World War I, came into use to better coordinate timetables. Railroads were the first industry big and controversial enough to necessitate regulation from the national government: the Interstate Commerce Commission.

Railroads also changed political campaigning. Unable to get around and meet people effectively prior to the Civil War, candidates could now crisscross the country on whistle-stop campaigns, stop in every town en route, and step out the back car or caboose to give a brief speech. The festivities often included bands, bunting, and throngs of people anxious to hear and shake hands with prominent figures they’d otherwise have no way of ever meeting.

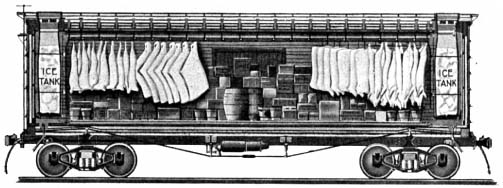

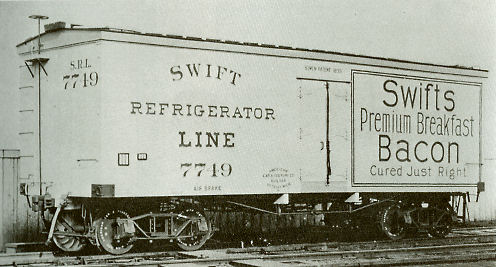

Railroads even changed our bodies. Refrigerated boxcars and steamboats allowed relatively fresh produce to ship around the world all year, whereas people traditionally had only eaten local fruits and vegetables in season. Railroads and steamships shipped produce from Latin America, Hawaii, and the West Coast to other parts of the country. Local in-season produce is kind of like live music insofar as it’s great, but also limiting depending on where one lives. Why were visitors to the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition so amazed to see bananas? Before refrigerated transport, produce couldn’t stay fresh between Central and North America, so no one in the U.S. had ever seen one. Access to better nutrition caused Americans to get taller. That’s why the door jams are noticeably lower and the beds shorter in 19th-century homes, and why Lincoln was seen as so tall at 6’3”. Having a president 6’3” during the Civil War would be like having one 6’6” today.

The Industrial Revolution’s long-term impact on nutrition is complicated, though, because modern agriculture and food processing corresponded with the rise of Western Diseases (or Diseases of Affluence) that include varieties of heart disease, cancer, and diabetes — compounded by more sedentary (immobile) lifestyles and impacted by genetics. Initially, scientists thought that the upsurge in these illnesses was due merely to fewer people dying young in infancy or from infectious diseases or other Diseases of Poverty (e.g. malnutrition). However, our focus on agricultural yield (quantity) has led to a corresponding decline in the nutritional value and diversity of crops, and we now know that, despite widely varying diets, people who survived infancy and dodged infectious diseases in non-industrialized societies rarely died from heart disease, cancer, or diabetes. It’s a good time to specialize in nutrition or soil science because we’re still sorting out how industrialized agriculture has helped and hurt our collective health.

Subways also came of age in the late 19th century. The London Underground started in 1863 and Boston opened the first American subway in 1897 (above), followed by New York (1904), Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Chicago. Horses weren’t just up against the internal combustion engine, as we’ll see below, but also electric motors. The Boston subway ran on Frank Sprague’s “self-regulated motor” that he pioneered in engineering Richmond, Virginia’s electric streetcars on spec, whereas London’s “Tube” initially ran regular coal-fired steam locomotives, creating ventilation problems. Italian and Irish-American laborers dug Boston’s entire system by hand, with picks and shovels, for 15¢/hour (~ $4.50 today). Sprague, who, like Tesla, worked for Edison before going it alone, invented a motor that could bear different loads at the same speed, making it attractive to industry, elevators, and transportation. Edison told reporters that it was the best motor and later bought out Sprague and changed his company’s name to Edison.

Subways were a tough sell for a public leery of going underground both for religious and safety reasons, especially when the Current Wars and real accidents made them fear electricity, mining accidents were common, and tuberculosis, a leading killer in the 19th century, was associated with stuffy, unclean air. But initial riders were pleasantly surprised at how clean, dry and fast the system was and soon Boston’s streets weren’t jammed with horse-drawn carriages.

Retail

Moving goods over rail allowed for national companies. These same firms could become multi-national by linking up with steamships. Recognizable brand names like Kellogg’s, Standard Oil, and Coca-Cola could now be found all over the country and, soon, the world. Isaac Singer’s sewing machines and Henry Heinz’ pickles and ketchup could travel by rail across the country, then by ship across the oceans in the precursor to today’s container-based intermodal system. Advertising via women’s magazines like McCall’s and Ladies Home Journal reinforced brand recognition and helped transition the U.S. to a more retail-oriented economy by the 1920s (married women made most household purchases). It’s no coincidence that Coca-Cola, along with being one of the most profitable companies in history, is arguably the most successful and prolific advertiser in history. Likewise, Wrigley’s gum overwhelmed competition like the Chicle Co. trust with advertising. These companies were big enough to require specialists to run them. Unlike customary “mom-and-pop” operations where families ran the whole business, big firms needed departments of advertising, accounting, and management. Soon, colleges followed suit, offering business majors in these sub-fields.

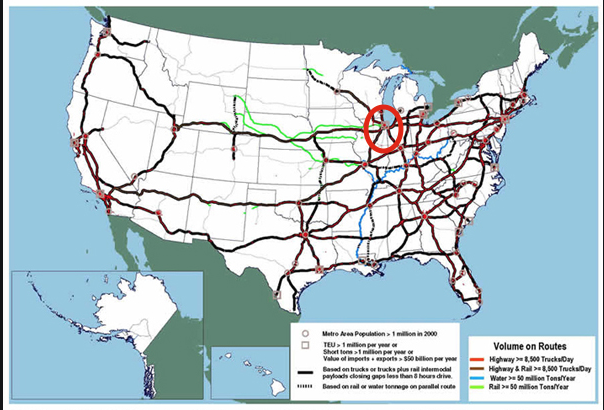

Many companies headquartered in Chicago. Its location at the southwestern corner of Lake Michigan, western-most among the Great Lakes, made it a natural hub for western railroads (above). For many years, Chicago was America’s stockyard and lumberyard. Other rail towns like Minneapolis, St. Louis, and Kansas City emerged to process grain but, initially, most livestock made their way to Chicago’s stockyards and slaughterhouses. Timber came in from Michigan and Wisconsin. They manufactured farm implements there and in outlying parts of Illinois and Iowa, along with train cars, both box and passenger. Large “departmentalized” stores like Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery Ward shipped products by rail from Chicago to rural communities, as did the Wrigley Company. Klein Tools, founded in 1857, sold hand tools to the growing nationwide market of electricians and linemen. Subsidized public mail service kept their costs down. Retailers took advantage of subsidized mail the same way Amazon, Netflix, and eBay take advantage of free Internet today.

Richard Sears started selling pocket watches but branched out to nearly everything then commercially available, including even build-it-yourself home and barn kits. Sears understood that economy of scale allowed him to undersell local merchants through his iconic mail-order catalogs, which doubled as toilet paper in thousands of outhouses across America before the invention of that now taken-for-granted product. Sears was detail-oriented. For instance, he observed that people stacked magazines and catalogs in a pyramid so he made his cover dimension smaller to end up on top. Sears’ pickers roller-skated from shelf to shelf loading goods onto trains in a centralized Chicago warehouse.

Eventually, pneumatic tubes moved goods around even quicker. Sears warehouses presaged the bulk stores of today and the assembly line system later implemented by Henry Ford. Ford studied Sears’ system and those of meatpacking plants in Chicago and Cincinnati. Sears sponsored Saturday night dance shows when radios came around and helped pioneer employee profit sharing and corporate philanthropy, building African-American schools in the South. With 1/30 American adults working at Sears in the early 20th century, it occupied a similar spot in the economy as Walmart does today. Walmart applies the same principles of efficiency, low prices, and intermodal transport, except on a more global scale.

While Sears developed a nationwide model, Memphis grocer Clarence Saunders reinvented interior food retail starting in 1916. In traditional grocery stores, customers placed an order at the counter and the clerk went back to the stockroom to retrieve the goods. Saunders brought the stock out into the open and had customers collect it themselves. While this introduced the potential downside of shoplifting, it was more time-efficient. Saunders’ simple breakthrough is the sort that, after you learn about it, makes you frustrated that you hadn’t thought of it yourself. His Piggly Wiggly stores were the first supermarkets and their nonsensical name reinforced awareness as customers thought about what the name meant. Clothing, hardware, and other stores quickly adapted the customer retrieval model. Saunders ruined himself financially, though, when his short squeeze on his own stock backfired.

Steel

What Sears did for retail, Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller did for steel and oil, respectively. Carnegie emigrated from Scotland at age 12 with his mother and “pulled himself up by his own bootstraps,” as the saying goes. Rockefeller did likewise, supporting his family as a boy after his snake oil salesman father abandoned his family. Their stories were the classic fulfillment of what came to be known as the American Dream: that through hard work, ingenuity, and “keeping one’s nose to the grindstone,” anyone could make it rich in the Land of Opportunity. Ample opportunities for advancement set the U.S. apart in the 19th century, at least for certain demographics. There were near limitless opportunities for northern white males from the right parts of Europe, just as there are for most of us today — something immigrants often recognize more than native-born Americans. Those of us who don’t strike it rich today have mainly ourselves and our own lack of talent, skill, brains, good looks, ruthlessness, hard work, luck, or ambition to blame (along with our parents, since some rich people just inherit wealth). Only a small fraction actually pulled off the American Dream in the 19th century — more would’ve ruined the dream — and today the U.S. has less upward mobility than Europe. But millions succeeded on a less dramatic scale than Carnegie or Rockefeller, as they do now. Today, over 70% of America’s billionaires are self-made, meaning that they didn’t inherit their wealth.

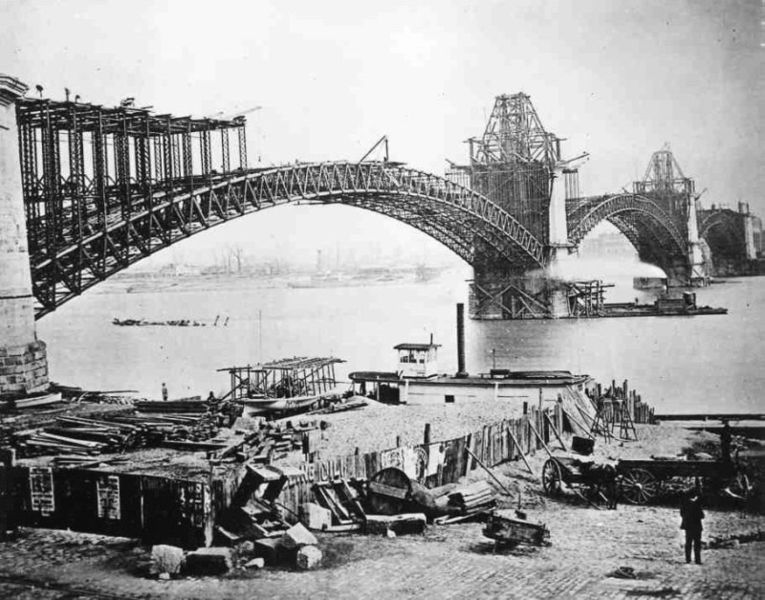

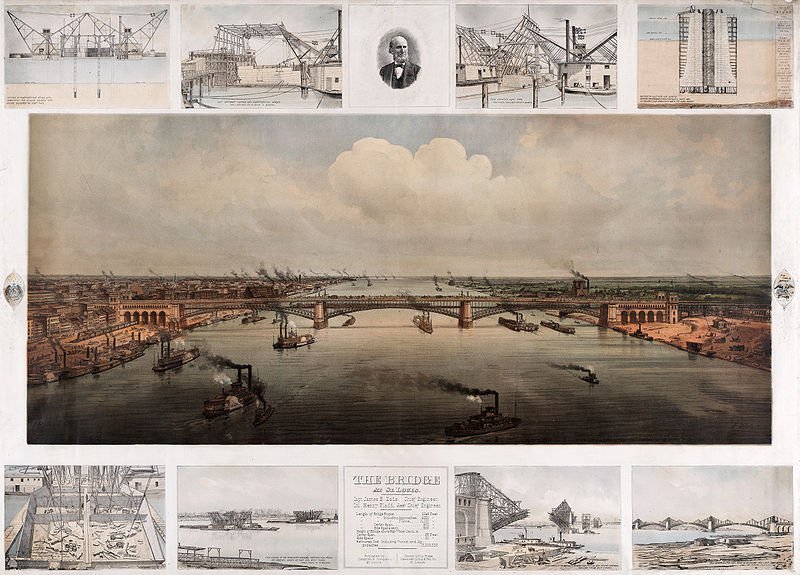

Carnegie succeeded on a colossal scale. He is a good example of being well situated, vocationally, to stay abreast of developments. He worked in the telegraph office of a railroad as a teenager, giving him an ideal vantage point on two leading industries and showing him the importance of steel to America’s future. He worked his way up through the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), the biggest corporation in the world at the time. His work as a subcontractor on the St. Louis Eads Bridge in the 1870s awakened him to the need for better and cheaper ways to manufacture steel. The bridge across the Mississippi River was the first use of structural steel as the primary material.

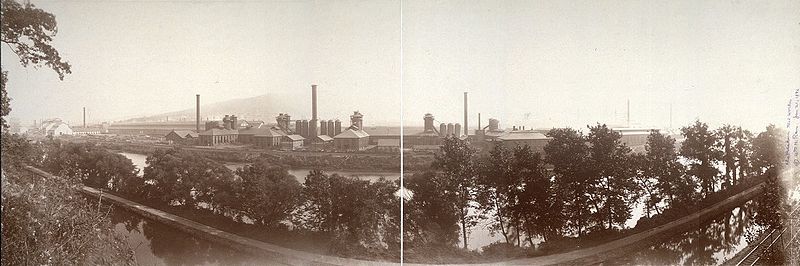

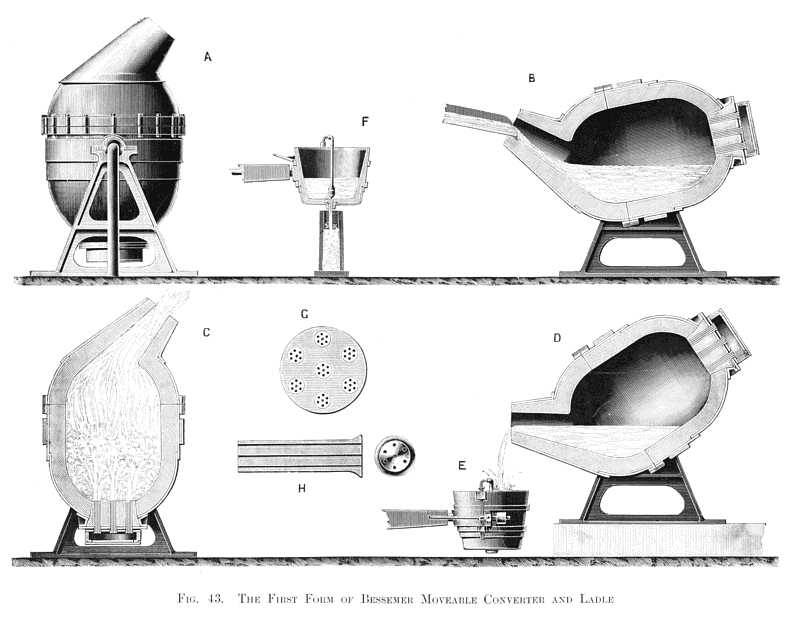

Carnegie built his own steel plant outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. More than any industrialist of his era, he understood the importance of what’s now called Research & Development, or R&D. Rather than simply pocketing profits, he plowed them back into researching ways to make stronger steel and stay ahead of the competition. Carnegie outsourced some research to Edison’s lab in New Jersey. He was looking for better ways to transform iron, the high carbon-content of which makes it too brittle for big heavy structures, into steel with the highest ultimate tensile strength (UTS). One exception was Gustave Eiffel’s namesake “Iron Lady” tower in Paris, but Eiffel used steel to support the skeleton of the Statue of Liberty that France gave the U.S. to celebrate the Union’s victory in the Civil War. Cast iron holds compression better than shear and tension, as shown by the Ashtabula River railroad bridge disaster in Ohio in 1872. Structural steel has a tensile strength nearly twice that of wrought iron used in England’s Clifton Suspension Bridge (1864), then the biggest such span in the world (today’s engineers often prefer concrete). While on a working vacation in Germany and England, Carnegie researched the (Henry) Bessemer process of mass-producing steel from molten pig iron, the purified derivative of oxygen-free iron, by combining it with other elements. He imported the Bessemer technology to his new plant in Pennsylvania. Carnegie’s steel helped build America’s railroad tracks, suspension bridges, skyscrapers, and revamped Navy.

Carnegie built his own steel plant outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. More than any industrialist of his era, he understood the importance of what’s now called Research & Development, or R&D. Rather than simply pocketing profits, he plowed them back into researching ways to make stronger steel and stay ahead of the competition. Carnegie outsourced some research to Edison’s lab in New Jersey. He was looking for better ways to transform iron, the high carbon-content of which makes it too brittle for big heavy structures, into steel with the highest ultimate tensile strength (UTS). One exception was Gustave Eiffel’s namesake “Iron Lady” tower in Paris, but Eiffel used steel to support the skeleton of the Statue of Liberty that France gave the U.S. to celebrate the Union’s victory in the Civil War. Cast iron holds compression better than shear and tension, as shown by the Ashtabula River railroad bridge disaster in Ohio in 1872. Structural steel has a tensile strength nearly twice that of wrought iron used in England’s Clifton Suspension Bridge (1864), then the biggest such span in the world (today’s engineers often prefer concrete). While on a working vacation in Germany and England, Carnegie researched the (Henry) Bessemer process of mass-producing steel from molten pig iron, the purified derivative of oxygen-free iron, by combining it with other elements. He imported the Bessemer technology to his new plant in Pennsylvania. Carnegie’s steel helped build America’s railroad tracks, suspension bridges, skyscrapers, and revamped Navy.

Steel skeletons could support skyscrapers and were fire-proof (and, in the 21st century, interfere with cell phone signals). After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the Windy City rebuilt much of its prime business district real estate with the country’s first tall buildings, taking advantage of their rail network to transport the steel. Civil War bridge engineer William Le Baron Jenney, the “Father of the American Skyscraper,” built Chicago’s pioneering Home Insurance Building in 1884 and the Horticulture Building of that city’s aforementioned 1893 World’s Fair that Westinghouse and Tesla lit. Skyscrapers, in turn, brought about the elevator; otherwise, who’d want to work on the 50th floor? Elisha Otis patented the first safely functional elevator in 1854. At the New York World’s Fair, he personally demonstrated the safety brake that stops the elevator if the main hoisting cable fails (see image). Steel skeletons allowed for lighter “skin” materials like glass on tall buildings, whereas it would’ve been impossible to build high with heavier stone or iron. Later, air conditioning made it more tolerable to work on high floors in the summer.

Carnegie steel built Louis Sullivan’s first skyscrapers in Chicago and the famous Brooklyn Bridge. Rival Bethlehem Steel built the Chrysler Building in New York and Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. Both contributed to the transcontinental rails and military. In his quest to stay ahead of the competition, Carnegie would close plants in his native Pittsburgh, often throwing hundreds out of work, and re-open better plants a few years later. The best was a plant outside Pittsburgh called the Homestead Steel Works. Homestead made many of the I-beams and girders that built America’s growing cities.

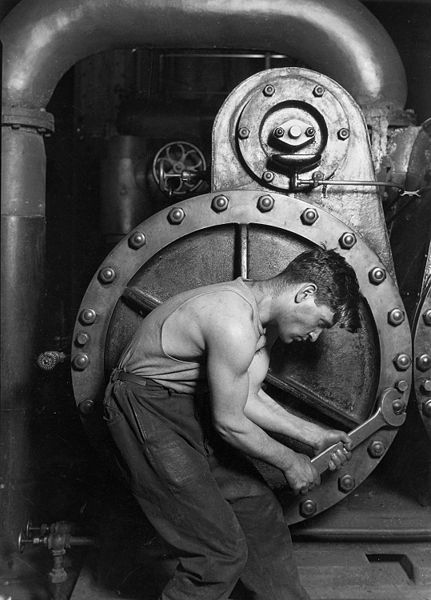

Working for Carnegie was hard and dangerous and the hours were long: 12-hours a day, six days a week. It was so hot in his mills that keys and coins melted into the skin of those who mistakenly left them in their pockets. Casualty rates were high. In the next chapter, we’ll see how Carnegie and his manager Henry Frick dealt with unhappy workers (spoiler alert: not nicely). In 1900, Carnegie sold his firm to banker J.P. Morgan for just under half a billion dollars (~ $15 billion today), briefly making him the richest man in the world. Morgan merged Carnegie Steel with others, forming U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar company. Football fans will recognize the familiar logo on the Pittsburgh Steelers’ helmets.

Working for Carnegie was hard and dangerous and the hours were long: 12-hours a day, six days a week. It was so hot in his mills that keys and coins melted into the skin of those who mistakenly left them in their pockets. Casualty rates were high. In the next chapter, we’ll see how Carnegie and his manager Henry Frick dealt with unhappy workers (spoiler alert: not nicely). In 1900, Carnegie sold his firm to banker J.P. Morgan for just under half a billion dollars (~ $15 billion today), briefly making him the richest man in the world. Morgan merged Carnegie Steel with others, forming U.S. Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar company. Football fans will recognize the familiar logo on the Pittsburgh Steelers’ helmets.

There was no federal income tax prior to 1913, but Sears, Carnegie, and Rockefeller — like Bill Gates, Sam Walton, and Warren Buffet later — gave back to society in the form of philanthropy. Carnegie built concert halls, libraries, and hospitals all over the country. Rockefeller, whose oil business we’ll cover momentarily, was at one point worth 2% of the entire country’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and built an endowment that later financed New York’s Rockefeller Center, Lincoln Center, and World Trade Towers, along with Teton National Park, a wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (and Cloisters), the University of Chicago, and the United Negro College Fund. Rockefeller and Carnegie competed almost as hard giving money away as they had making it. Others like Cornelius Vanderbilt (shipping and railroads), Leland Stanford (railroads and timber), and James Duke (tobacco and utilities) founded colleges, as well. While some of Rockefeller and Carnegie’s money later went toward nefarious purposes like eugenics research (Chapter 4), it continues to fund charities and causes today. Their endowments, along with that of fellow industrialist and banking magnate Andrew Mellon, later helped transform Pittsburgh into a model “turnaround city” of clean, high-tech industries after the American steel industry began to fade in the 1970s.

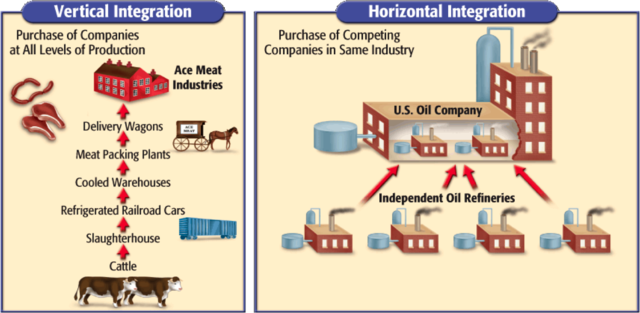

Also similar to Sears, Carnegie and Rockefeller took advantage of economies of scale, in each case more ruthlessly. Both Robber Barons, as they were known to their critics, cut overhead costs by buying up the entire process of production, or supply chain, from extracting raw materials “upstream” to shipping to manufacturing in factories or refineries to more shipping to point-of-sale/retail “downstream.” If they’d only made steel or refined oil, they would have spent much of their profit paying others to mine iron ore, drill oil, ship materials on railroads, and sell to the public. By buying the mines themselves and negotiating railroad discounts, they still had to pay overhead but not as much. They minimized their overhead as best they could through vertical integration, transforming variable costs into fixed costs. Today, when oil companies do their own exploration, drilling, shipping, refining, and retail (gas stations), they’re called integrated energy companies.

Another example of vertical integration was the Hollywood studio system of the early- to mid-20th century. Studios filmed in back lots rather than out “on location,” hired from a pool of company actors under long-term contracts, distributed the films, and owned their own theaters across the country. Boeing was originally more vertically integrated because they made their own engines along with fuselages and owned United Airlines, whereas today they mainly just assemble planes and missiles with parts from elsewhere. A modern example of vertical integration would be a search engine company like Google (part of Alphabet, Inc.) developing its own browser (Chrome), mobile operating system (Android), and broadband hardware (Google Fiber). H-E-B Grocery stores own some plants, fishing boats, dairies, and bakeries. Netflix makes its own movies and shows rather than just providing a platform for other studios. Another example of vertical integration is Amazon doing its own shipping via drones or Prime Air rather than using UPS, FedEx or USPS.

Oil

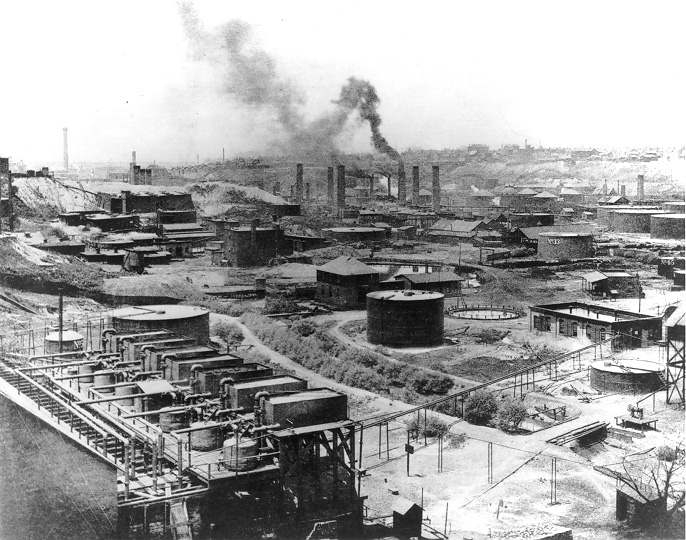

John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil employed vertical integration on a monumental scale, buying up ships and leveraging railroad discounts to move petroleum products. Later he got around railroad tank cars altogether by building his own pipeline, triggering a collapse in the railroad bubble in the 1870s. His Refinery #1 in Cleveland was situated near Great Lakes shipping and railroads. He bought coal mines in Colorado to run his ships and refineries until he transitioned to gasoline engines. Rockefeller wasn’t a total vertical integrationist, though, because he avoided the dicey business of extraction. Geologists at the time thought that oil moved around underground and, at first, it wasn’t subject to normal mineral rights law, but rather the English Common Law “finders keepers” rule applied to disputes between landowners and hunters (like wild game, oil purportedly moved and couldn’t be owned as property). “Wildcatters” could cut diagonally under landowner’s property or cheaply lease small patches just big enough for the oil well. Like gold and silver mining, drilling was a sort of “wild west” business that mixed real engineering with bribery, violence, luck, and supernatural aids like divining rods and spiritualist consultants. Rockefeller recognized that the contentious, hit-and-miss world of drilling was for gamblers and focused instead on something boring that he could control: refining oil efficiently. Let others find it. Likewise boring, the name Standard marketed his kerosene as safer and more dependable than that of his competitors. He wisely branded his company the industry’s “standard-bearer.”

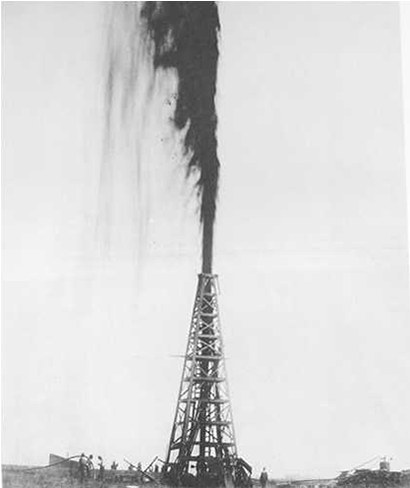

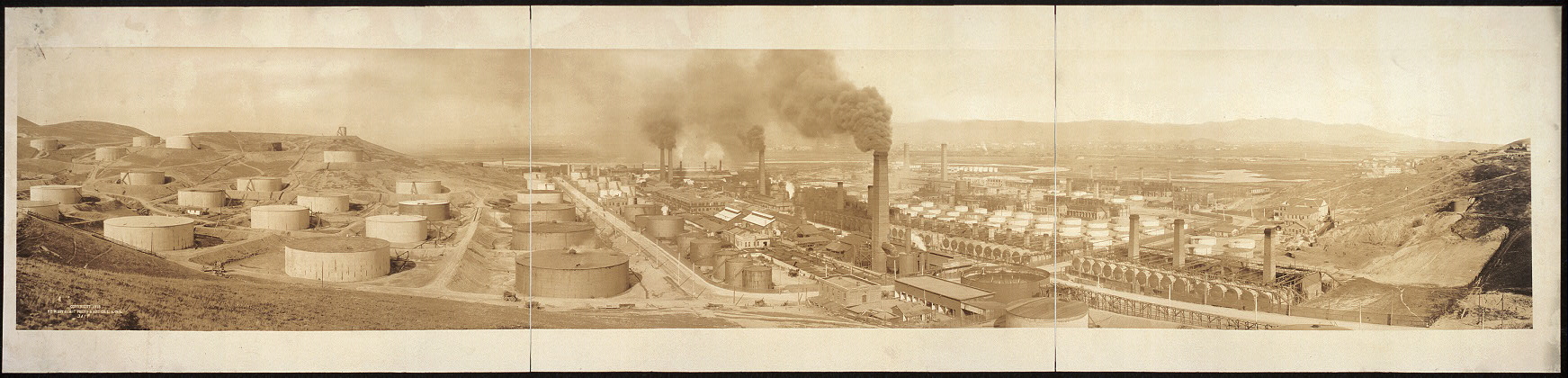

In Cleveland, Rockefeller was near rich oil deposits. Edwin Drake of Pennsylvania successfully drilled oil on a worthwhile scale for the first time in 1858 and bigger strikes in eastern Ohio, southeast Texas/Louisiana, Oklahoma, and southern California (Kern Field) followed in the coming decades. On the upper right is Lucas Gusher in the Spindletop Field south of Beaumont, Texas. In the 1930s, “Dad” Joiner’s Gusher in the East Texas Oil Field supplied one-third of America’s total petroleum.

Four-Stroke IC Engine: 1) Intake 2) Compression 3) Power 4) Exhaust, Courtesy of Zephyris-Wiki Commons

At first, oil was used mainly as a lubricant and to light kerosene lamps after the near extinction of whales. Rockefeller would have been rich just with these earlier uses given the growth of industry and the need for lubricants and light. You could even say that he lit the country before Edison. But what made him far wealthier yet, and kept Standard on top after light bulbs, was the internal combustion engine’s application to cars, trucks, tractors, and ships (later planes). The concept had a long history in the 19th century, overlapping with steam which fires external combustion engines. In 1876, German Nikolaus Otto developed the first efficient four-stroke engine that burned fuel in the piston chamber while producing measurable power. The forenamed Karl Benz used such an engine in his pioneering Motorwagen, while Gottlieb Daimler applied the engine to motorcycles and other vehicles around the same time. They used English railroad engineer Beauchamp Tower’s hydrodynamic technique to lubricate their engines with pressurized oil, reducing friction by maintaining a thin film between the moving parts. France was an early manufacturing center and their words automobile, garage, sedan, coupe, grand prix, and chauffeur remained in English. Chauffeurs doubled as mechanics.

Rockefeller worked with early automotive engineers to power engines with gasoline that, until then, had been a wasteful and toxic byproduct of petroleum refining. You might say he was an early and prolific recycler. Rockefeller used gasoline power himself with the giant engines that ran his refineries. Heating furnaces used oil, too. The discovery of huge oil deposits drove down prices, steering the market toward gasoline and away from steam and electric-powered cars, both of which were common in early automotive history, but gasoline engines continued to use electricity for the starter, ignition, and other systems. Stanley Motors made the most famous steam-powered horseless carriage, the “Stanley Steamer.” The first president with limousine service, Teddy Roosevelt, rode in a 1907 White Steamer. At first, electric cars were marketed mainly toward women because they were less noisy and smelly than gas-powered. Henry Ford (famous for gas cars) and Thomas Edison pushed electrical cars as late as the 1910s, envisioning drivers re-charging their batteries at their own off-grid generators that, at first, would be powered by fuel but eventually transitioned to windmills. This clean, quiet, self-sustaining transportation system never came about during the Brass Era because of oil’s declining costs, the greater range of gas-powered cars, the power of oil cartels, battery monopolies driving up prices, patent strangleholds, and problems with batteries either having too much resistance in nickel-iron form or being too heavy in lead-acid form. And steam wasn’t well-suited for the stopping and starting of cars, with the driver basically being in charge of a small power plant (there’s a reason steam train drivers were called engineers). Ironically, electric starters in gas cars doomed electric cars, at least for a century, because it made gas cars easier to start than they had been with hand cranks. Finally, World War I created a huge need for vehicles just as internal combustion was gaining an advantage over electric. In ensuing decades, General Motors colluded with oil and tire companies to buy up and destroy cities’ electric streetcars, as we’ll see in Chapter 15. As we saw above, electric motors are now mounting a comeback against internal combustion.

Karl Benz’ 1886 Patent Motorwagen w. Four-Stoke, Water-Cooled Internal Combustion Engine, Electrical Ignition, and Rack & Pinion Steering. Photo by Author from Petersen Automotive Museum, Los Angeles

Rockefeller was also a pioneer in horizontal integration, the process of monopolizing a sale or service to the greatest extent possible to gain market share. While competition is a key advantage of capitalism from the consumer’s perspective, it’s easy to forget that sellers would prefer to eliminate their competitors or at least build “wide moats.” The goal of horizontal integration is to displace rivals so that you no longer have to compete with them. One way is to just sell a superior product. Another technique is to undersell competitors until they go out of business, then raise prices. Amazon operated at a loss for years underselling companies like Diapers.com while cornering retail markets, willing to forego short-term profit to gain market share. Another legal way to expand horizontally or vertically is through mergers and acquisitions. If a fast-food chain bought a rival, that would be horizontal integration; if it bought cattle ranches, potato farms, bakeries, and a fleet of delivery trucks, that would be vertical integration.

A helpful mnemonic device might be to remember V.I.P. and H.I.M., for vertical integration process and horizontal integration monopoly. Horizontal integration is basically a fancy term for gaining a monopoly, or at least heading as far in that direction as possible. The impact cuts both ways on customers because companies attain pricing or market power by eliminating competition, but economy of scale can also allow the monopolizer to lower costs. Standard Oil, for instance, lowered the price of kerosene five-fold between the Civil War and early 20th century. But the government broke up their monopoly because they were leveraging their market share to negotiate unfairly low and exclusive railroad rebates, muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell (right) exposed their corruption, and competitors were unable to turn a profit with prices so low, similar to how the affordability of subsidized renewable energy today gives pause to fossil fuel and nuclear power companies making capital investments. Rockefeller cornered the oil market by temporarily underselling local competitors long enough to drive them out of business, using moles to spy on their R&D departments and bribing politicians. At age 33, Rockefeller controlled 90% of North America’s oil market, creating the nation’s first monopoly, or what was then called a trust. Trust-busting became an early form of government intervention in the economy as ripped off consumers and exploited workers objected to such “concentrations.”