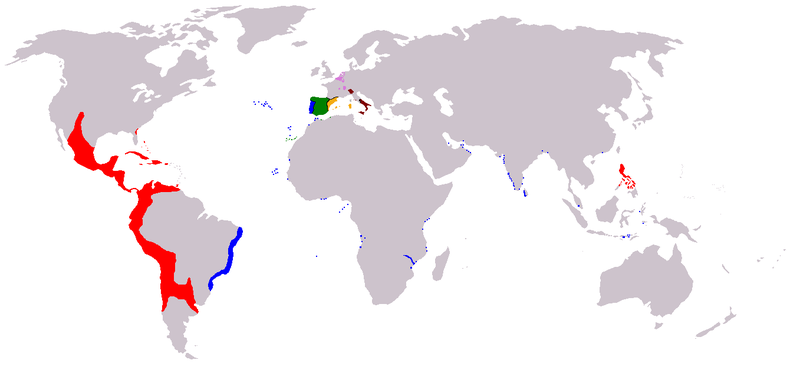

We learned in the first chapter how Vikings and maybe Polynesians skirted America’s shores inconsequentially, and in the second how Iberians (Spanish and Portuguese) led the way for Europeans during the Age of Exploration. Here we’ll examine America’s Spanish and French colonies before diving into the English and Dutch settlements that seeded the United States in coming chapters. You could begin to envision colonial North America as a jigsaw puzzle that we’ll start today with two big pieces, New Spain and New France. But we’ll start our story in the southwestern corner of Europe (left).

Spain’s New World exploration built on momentum from the Reconquista (re-conquering) of the Iberian Peninsula by Christians from Moors back in Europe. Moors were Arab, Berber, and converted Iberian Muslims who controlled this part of southwestern Europe starting in the 8th century CE. Moors were generally tolerant toward Christians and Jews as long as the latter paid taxes but a sporadic, centuries-long civil war culminated in Christian victory in Granada by 1492. Christians forced Jewish and Moorish Iberians to leave or convert. The victorious Castilian monarchy of Ferdinand II and Isabella I wanted to compete against their Portuguese neighbors for the lucrative international spice trade. They used wealth they confiscated from Jews to finance an expedition to Asia, or so they thought. Note: Castile (Castilla, above left) was in central Iberia, with Toledo its major city. Portugal was the kingdom in yellow along the west coast, with its capital in Lisbon (Lisboa on the map). Ferdinand and Isabella’s marriage unified Castile and Aragon. That same year, 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella’s moved into their new home at Alhambra in Granada, that eventually combined Arabic and Renaissance architecture.

At first, Castilians paid Genoese sailor Cristoforo Columbo (Columbus) to sit tight and not take his proposal to travel west to Asia to the French. They weren’t yet willing to gamble on him but they didn’t want him working for anyone else either. Eventually, Ferdinand and Isabella’s Jewish finance minister Louis de Santángel convinced them that a voyage was worth the risk, as Columbus might be able to convert Asia to Christianity. They sent him west to find a quicker route to Asia than their Portuguese rivals were then going south and east around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. As we saw in the previous chapter, Columbus’ brother Bartolomeu (Bartholomew) helped doctor maps, exaggerating the Cape’s size, to discourage Castilians from trying the African route. Portuguese King João II encouraged the ruse because he correctly thought that the Columbus brothers were underestimating the Earth’s circumference, which would foolishly inspire them to try a western route instead, but the Castilians got the last laugh because they discovered a new continent, America. English and French courts had denied Bartholomew’s petition for a similar voyage but Christopher knew that Spanish rulers wanted to expand their trade routes and played on their rivalries with Portugal and France. With little downside in their risk/benefit analysis, the Castilian Crown christened Columbus Admiral of the Ocean Sea and promised him a percentage of any future Asian profits.

Columbus was no stranger to navigation and trade. He’d searched for gold off the West African coast in the 1480s, sailed as far north as Iceland, and traded sugar in the Madeira Islands, where he married a Portuguese woman, Filipa Moniz Perestrelo. He’d survived a pirate attack by jumping overboard and swimming seven miles to the Portuguese shore. Columbus’ voyages to America also included Moorish crew members, like the Afro-Spanish Niño brothers. There’s also a fringe theory suggesting that there were already Moors in the Caribbean. But, if that was the case, they never returned to Europe, similar to the purported, un-proven pre-Columbian Welsh and Irish American explorations mentioned in Chapter 1. If they had, Columbus’ Moorish sailors would’ve known where they were going. One of the crew wrote of seeing a “mosque,” but might have meant a rock outcropping shaped like a mosque.

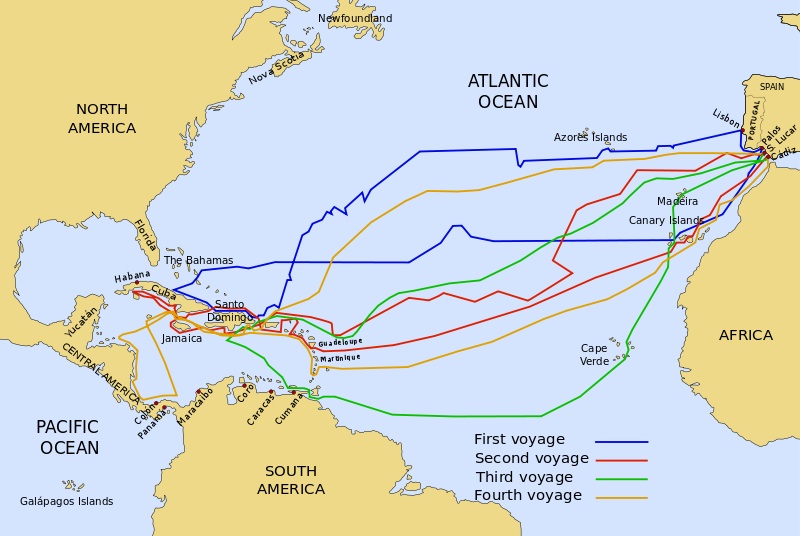

In October 1492, Columbus led three small ships — the Nina (Santa Clara), Pinta, and Santa Maria (La Gallega) — under the Castilian flag through the Bahamas to landfalls on the islands of Cuba and Hispaniola (modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). No one actually knows for sure which island he landed on first. Early Haitian colonies of La Navidad (“Christmas Town,” built from remnants of the grounded Santa Maria) and La Isabela struggled, but the Castilian settlement eventually took root. Columbus was searching for treasure and hoping to convert natives to Christianity. Much has been made about which of the “3 G’s” — God, Glory, and Gold — truly motivated Columbus, but there is no reason to think it wasn’t a combination. Columbus was a devout Catholic who wanted to get rich and famous.

More controversial has been Columbus’ reputation, which used to be above reproach in the U.S. but came under fire as the 500th anniversary of his first voyage approached. For years, led by Italian-Americans starting in 1866, the U.S. celebrated Columbus Day each October 12th as an official holiday. During Columbus’ lifetime, his hometown of Genoa was not part of Italy, which didn’t exist prior to 1861, so really he was neither Italian nor Spanish. In 1989, Native Americans poured fake blood on Columbus’ statue in Denver as Italian-Americans marched in their annual parade. The Indigenous Americans’ protest and other scholars’ reconsiderations trace to the demise of the Taíno–Arawak and Kalinago (Carib) Indians who were wiped out by the Spanish. The Spanish got along reasonably well with the Arawaks as long as they could swap falcon bells and trinkets for gold but, precisely because the Arawaks didn’t value gold, they hadn’t mined much of it. The Spanish enslaved them to mine more gold, at which point the Arawaks quit having kids and started committing suicide, necessitating the need for importing enslaved Africans. Aside from mining, the Spanish also raised cattle and grew sugarcane and fruit trees.

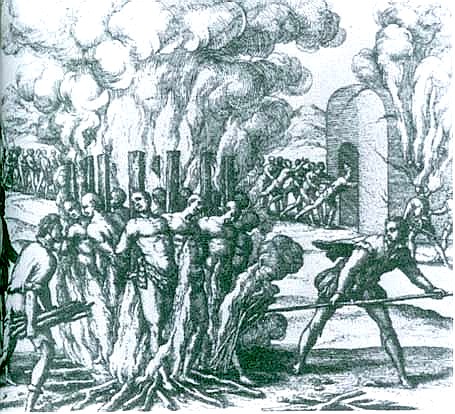

In 2006, more primary source documents shed light on the brutality of Columbus and his brothers when they governed Hispaniola. They purportedly swapped Native American women as sex slaves and hunted males to render as dog meat. Columbus not only amputated the limbs of Taíno-Arawaks and Kalingos unwilling to submit to slavery and paraded their dismembered bodies, he also treated his own men similarly – all this on a mission intended partly to spread Christian values. His men also made change purses out of castrated indigenous scrotums. Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, who accompanied Columbus on the second voyage, wrote in his Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies that the Castilians’ policy toward American Indians was to “exasperate, ravage, kill, mangle, and destroy.” He agreed with those who saw these actions as contradicting Christian values, while some historians suggest they were actually in keeping with 15th-century Spanish Catholicism insofar as Columbus hoped to convert Indians by force. The Castilian Crown hoped to bring about a new kingdom of God by imposing Catholicism globally, not just in Iberia. A generation after Columbus, the Castilian Crown laid out their religious justification for conquest more explicitly in their 1513 Requerimiento that clearly explained the consequences of resistance to Christian conversion. Resistance to conversion, in turn, justified conquering anyone who wasn’t Christian (“The deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault”):

But, if you do not do this, and maliciously make delay in it, I certify to you that, with the help of God, we shall powerfully enter into your country, and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their Highnesses; we shall take you and your wives and your children, and shall make slaves of them, and as such shall sell and dispose of them as their Highnesses may command; and we shall take away your goods, and shall do you all the mischief and damage that we can, as to vassals who do not obey, and refuse to receive their lord, and resist and contradict him; and we protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault, and not that of their Highnesses, or ours, nor of these cavaliers [conquistadors] who come with us. And that we have said this to you and made this requisition, we request the notary here present to give us his testimony in writing, and we ask the rest who are present that they should be witnesses of this Requisition.

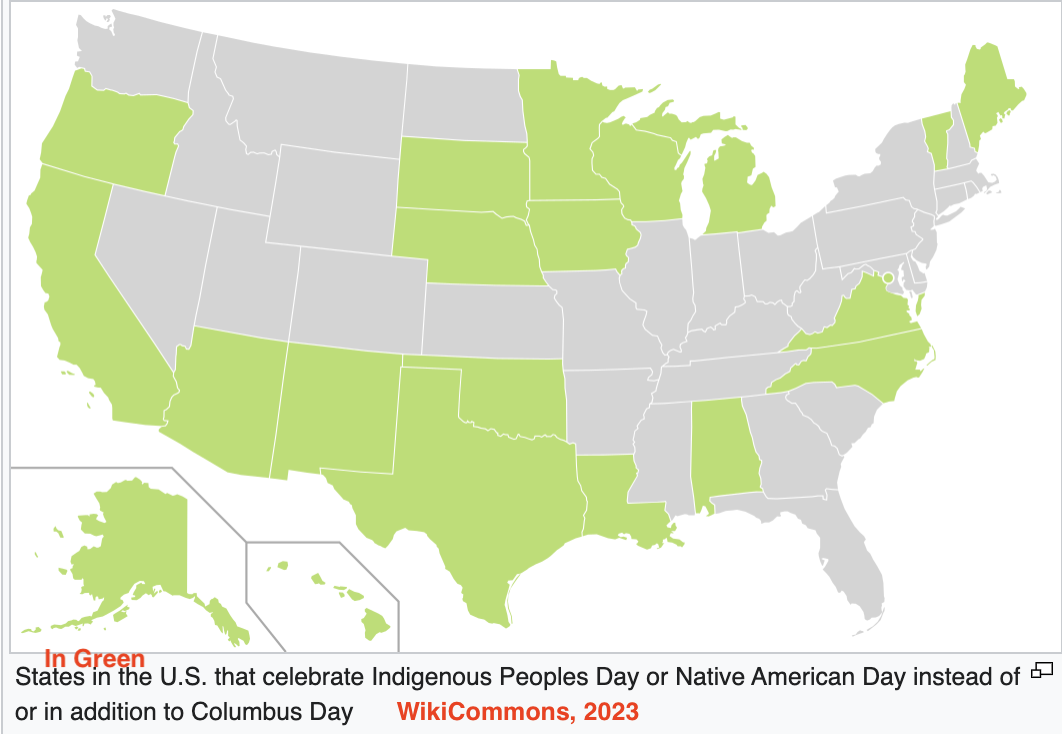

Columbus operated under similar directives after the Pope, in 1493-94, granted Spanish and Portuguese Christians control of the Western Hemisphere over Native Americans in the Bulls of Donations and Treaty of Tordesillas. Setting aside everyone’s love of getting a day off work or school, should the U.S. and other Latin American countries celebrate Columbus Day, given his sociopathic behavior? Or, does criticizing Columbus make us guilty of ahistorically applying modern standards to a different era? The Castilian Crown gave Columbus and his brothers a short six-week jail sentence in 1500, but their main concern was likely more his mismanagement of the colony and refusal to cede power to Francisco de Bobadilla on royal orders than his brutality. Bobadilla replaced him as governor, sent the Columbus brothers home in chains, and reported on Columbus’ brutality toward Native Americans, Spanish colonists, and his own officers. This is an instructive case in the complexity of interpreting primary sources because writers like Bobadilla may have had their own axes to grind and his report isn’t widely available in English. Still, we have multiple primary Spanish sources depicting Columbus as a barbarian, including Dominican friar Antonio de Montesinos, whose advocacy for Indigenous Americans, whom he described as God’s people, inspired Bartolomé de la Casas. There are also modern secondary sources depicting Columbus as an abolitionist living in harmony with Caribbean Indians, based on the key but subjective primary source of Columbus’ own journal. Even if innocent by 15th-century standards, does Columbus’ mere acquittal on a we shouldn’t judge by modern standards defense necessarily translate into we should, therefore, celebrate him with a holiday? Should holidays have a higher standard than mere non-condemnation — something we determine by today’s standards, regardless of what passed for normal in the 15th century? Holidays, more so even than monuments and building names, are selective and affirmative, guaranteeing anyone we celebrate a starring role in our culture wars. Some states and cities now celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, which originated in Berkeley, CA in 1992 to counter Columbus Day, though they don’t correspond neatly with red and blue states.

Columbus operated under similar directives after the Pope, in 1493-94, granted Spanish and Portuguese Christians control of the Western Hemisphere over Native Americans in the Bulls of Donations and Treaty of Tordesillas. Setting aside everyone’s love of getting a day off work or school, should the U.S. and other Latin American countries celebrate Columbus Day, given his sociopathic behavior? Or, does criticizing Columbus make us guilty of ahistorically applying modern standards to a different era? The Castilian Crown gave Columbus and his brothers a short six-week jail sentence in 1500, but their main concern was likely more his mismanagement of the colony and refusal to cede power to Francisco de Bobadilla on royal orders than his brutality. Bobadilla replaced him as governor, sent the Columbus brothers home in chains, and reported on Columbus’ brutality toward Native Americans, Spanish colonists, and his own officers. This is an instructive case in the complexity of interpreting primary sources because writers like Bobadilla may have had their own axes to grind and his report isn’t widely available in English. Still, we have multiple primary Spanish sources depicting Columbus as a barbarian, including Dominican friar Antonio de Montesinos, whose advocacy for Indigenous Americans, whom he described as God’s people, inspired Bartolomé de la Casas. There are also modern secondary sources depicting Columbus as an abolitionist living in harmony with Caribbean Indians, based on the key but subjective primary source of Columbus’ own journal. Even if innocent by 15th-century standards, does Columbus’ mere acquittal on a we shouldn’t judge by modern standards defense necessarily translate into we should, therefore, celebrate him with a holiday? Should holidays have a higher standard than mere non-condemnation — something we determine by today’s standards, regardless of what passed for normal in the 15th century? Holidays, more so even than monuments and building names, are selective and affirmative, guaranteeing anyone we celebrate a starring role in our culture wars. Some states and cities now celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, which originated in Berkeley, CA in 1992 to counter Columbus Day, though they don’t correspond neatly with red and blue states.

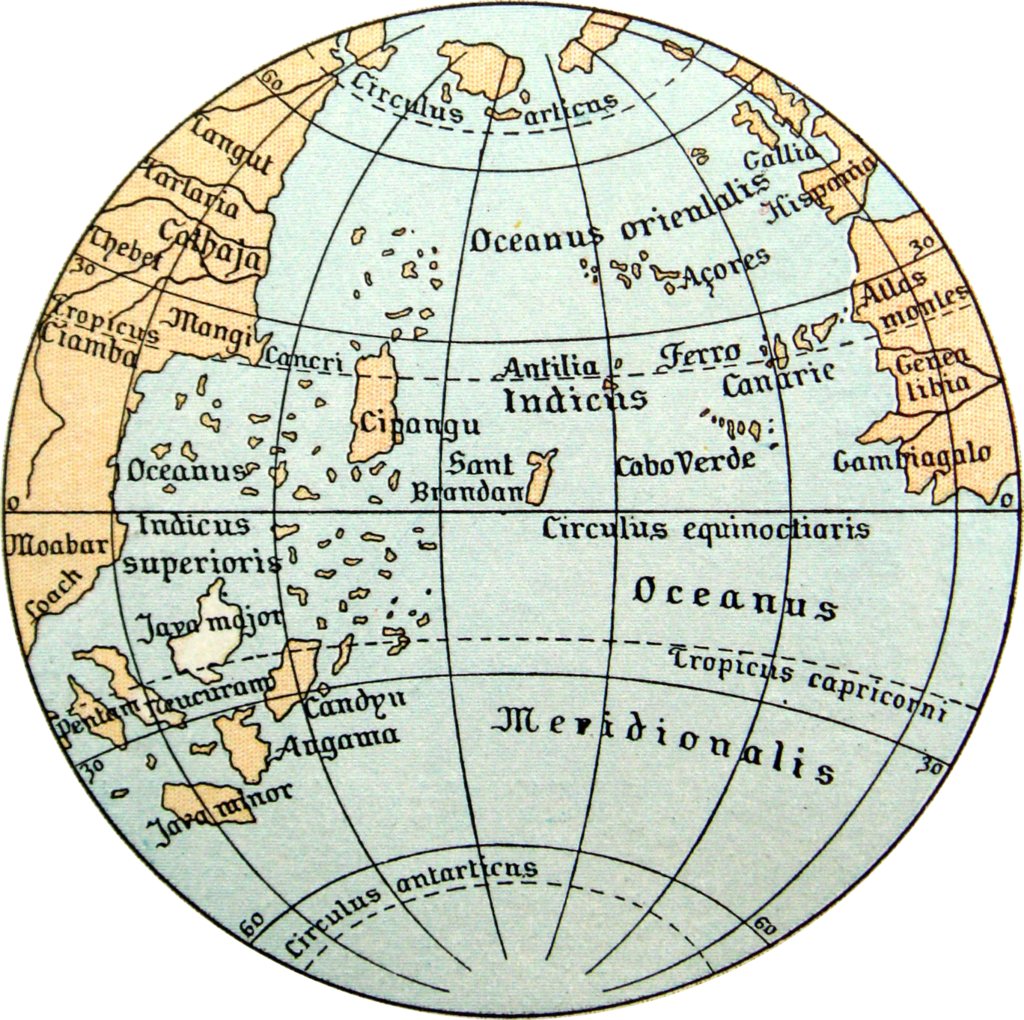

Martin Behaim’s 1492 Globe Showing Japan (Cipangu) in the Atlantic Ocean, Larousse Encyclopedia-WikiCommons

Regardless of Columbus’ personal reputation, the bigger issue is whether the European settlement of the Americas should be celebrated in the first place, with the date on which Columbus made landfall being symbolic of that broader development. Was European conquest of the Americas a good thing? Until recently, it was an obvious cause for celebration for both Hispanic and Anglo-Americans. But by Columbus’ 500th anniversary, in 1992, people felt more ambiguous about the near decimation of Native American civilizations. And people today are more likely to question the chauvinistic Discovery Doctrine whereby Europeans granted themselves the right to conquer all lands and enslave all people not governed by a Christian monarch, starting in 1452. These are questions each reader has to work out on their own. In 2023, the Catholic Vatican (Holy See) repudiated the Discovery Doctrine it advanced during the Age of Exploration.

Either way, Columbus contributed to geographic and navigational knowledge by exploring the Caribbean. He learned that easterly trade winds can carry boats there in the lower latitudes while, further north, westerly winds push ships back to Europe. Yet, while Columbus pioneered European exploration of the Americas, he maintained that he’d explored the outer islands of Asia — similar to Japan, Marco Polo’s Cippangu below and upper left — not a new part of the world. He never fully comprehended that he had discovered a different hemisphere, despite several trips back and forth between Europe and what he named the West Indies, and even a landing in Central America on his last voyage. Or, at least he never claimed to. Some historians theorize that he knew he wasn’t in Asia but reported that back home because his contract with the Crown only paid out for Asian goods. When he felt the strength of the Orinoco River near its mouth (off today’s Venezuela), he rightly theorized that a river of that size must have originated on a continent rather than a small island.

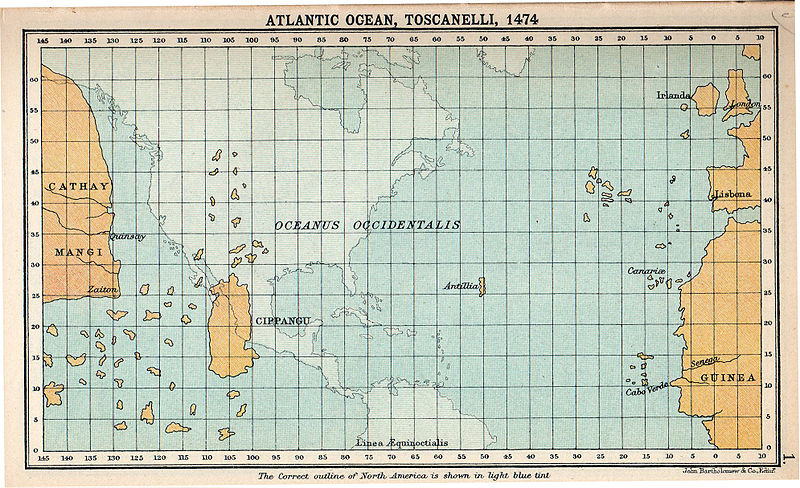

To see how Europeans viewed the Western Hemisphere as late as 1532, see this German map, which shows the globe being turned by a crank-wielding angel. Columbus’ confusion stemmed from reading a passage in Marco Polo’s Travels (Chapter 1) that suggested Asia was bigger than it really is, combined with using Egyptian Claudius Ptolemy’s miscalculations as to the circumference of the Earth — that Ptolemy had mistakenly updated in the 2nd Century CE from fellow Alexandrian Eratosthenes, who’d been virtually correct in the 3rd Century BCE. This 1474 map by Florentine astronomer Toscanelli gave the same impression as Behaim’s globe on the upper left:

Florentine Mathematician Paolo Toscanelli Inspired Columbus’ Voyage, But Neither He Nor Columbus Could Convince Portugal’s Leaders That It Would Be Easier To Circumvent Middle Eastern Traders By Going West Rather Than East

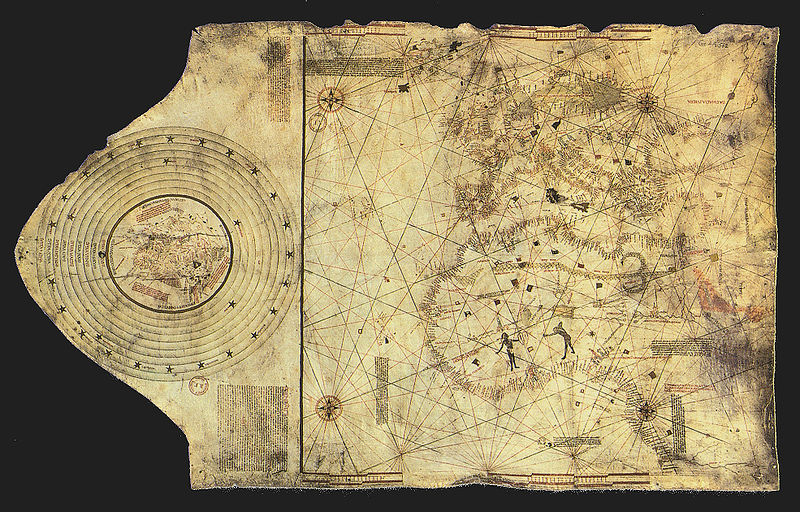

Columbus also consulted 9th-century Baghdad geographer Ahmad al-Farghani’s sounder calculations, but he used Italian rather than Arabic miles in his own charts, causing him to underestimate the world’s circumference. The result was that he thought the circumference was 15.5k miles instead of 25k and underestimated the distance west from Europe to Asia. This optional animated map details the confusion. While the Portuguese rightly guessed that Columbus was wrong in his calculations, they failed to realize that he’d discover America instead near where he thought Asia was. His crew would’ve run out of food and water had they not accidentally run into a different continent. To account for his mistake, Columbus even theorized that Earth was shaped like a pear instead of being round. This is likely the Columbus brothers’ own 1490 map drawn in Lisbon, though there’s no definitive proof:

This modern map shows Columbus’ four voyage routes:

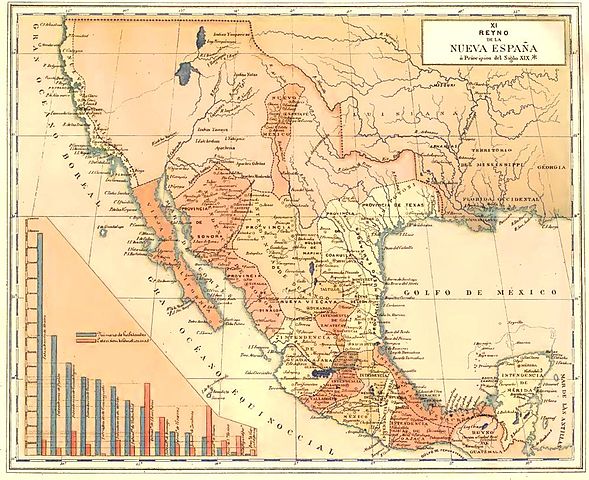

Columbus skirted the mainland briefly in 1498, but it wasn’t until a generation later that Spanish explorer/conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa understood the magnitude of the Pacific Ocean and that the Western Hemisphere constituted two continents separate from Asia. Far from being a bay separating Mexico and China, the Pacific is an ocean much bigger than the Atlantic. After Columbus’ accidental discovery of America, the Spanish carried on against Indigenous Americans in the New World with the same military momentum they’d built up against Moorish Muslims in the Old. Under the encomienda system, the Spanish awarded victorious conquistadors the right to govern, tax, and enslave those they conquered, giving their generals extra motivation to fight and gain territory that flew under New Spain’s flag.

Columbus’ successors explored the Central American mainland and claimed vast territory they called New Spain for the Castilian crown. Francisco Pizzaro went south to take Peru from the Inca, while Hernán Cortés claimed the area that’s now Mexico from the Aztecs, or Mexica (Aztec is Spanish for the Nahuatl-speaking Indians who called themselves Mexica). Cortés was a rogue explorer, unauthorized by the Spanish Crown to conquer land. His conquest of Mexico is notorious because of the improbability that his small group of men could gain control of such a vast empire but, as we’ll see below, that wasn’t really the case. The Aztecs also lacked guns and had never seen horses, let alone soldiers on horseback, which one can imagine was an intimidating sight. Epidemics also ravaged Native Americans in the early 16th century, though it’s been difficult for historians to distinguish between the smallpox Spanish brought with them and an ongoing cocoliztle epidemic carried by rodents and caused by El Niño-related fluctuations between drought and flood.

Romance also played a role. Cortés fell in love with a Nahua woman, Malinalli, who helped him negotiate the terrain and translated into Aztec for him after Cortés spoke in Spanish to Francisco de Aguilar, who translated into Mayan for Malinalli. Also known in Spanish as La Malinche or Doña Marina, she was first in a line of indigenous intermediaries who inadvertently helped along white expansion, including Pocahontas in the Chesapeake, Tisquantum in New England, and Sacagawea on the Lewis & Clark Expedition.

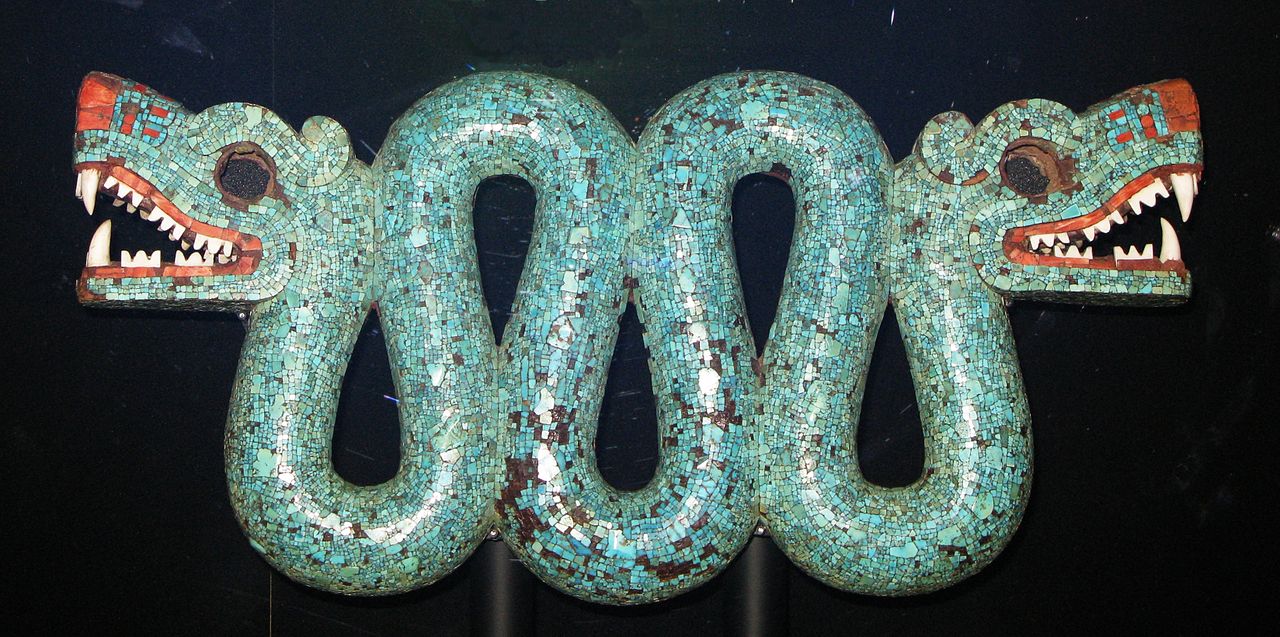

Double-Headed Serpent (Quetzalcoatl?), Possibly Gift From Montezuma to Cortes, Made of Turquoise, Spiny Oyster Shell & Conch Shell, British Museum

According to legend, Aztec leader Moctezuma II viewed the Spanish as the fulfillment of a religious prophecy: the arrival of Quetzalcoatl, the plumed serpent. But that story was concocted later by Spaniards who’d never been to the Americas. The Spanish mainly divided and conquered because of the Aztecs’ unpopularity. Aztecs had only recently gained control over the area themselves and their onerous taxes, which included one human sacrifice per day, made the region ripe for revolt (they sacrificed human blood to their Sun god Huītzilōpōchtli to keep the Sun rising). Thus, thousands of Aztecs joined Cortés’ troops and they weren’t really outnumbered after all.

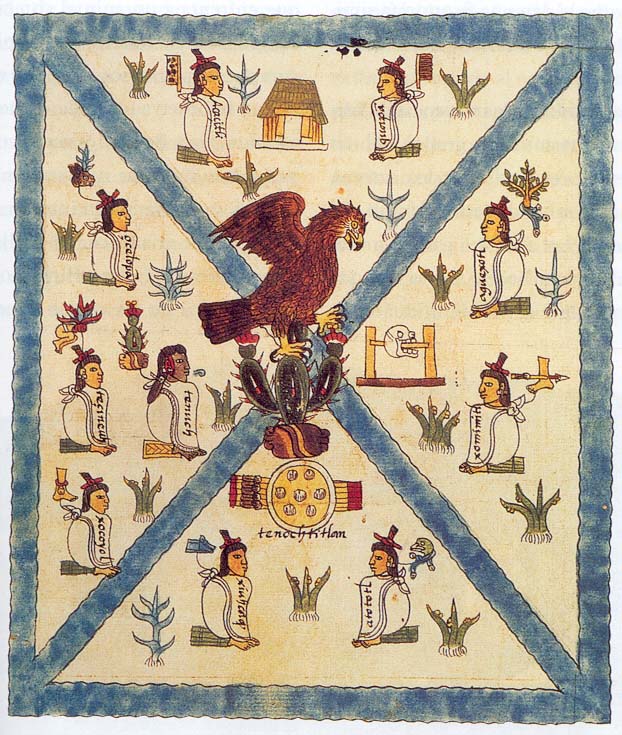

The Spanish destroyed most of Mesoamerican civilization to exert their dominance. The main exceptions are Mayan ruins they didn’t see because they’d been overgrown in the Yucatan jungle and codices that chronicled and illustrated Aztec traditions. Some of these codices are in the native Nahuatl tongue, while others were transcribed by friars to alert other missionaries what traditions they needed to stamp out. Whatever their origins, they’ve provided archaeologists and historians with a trove of information amidst otherwise scant primary sources from the Aztec perspective (or, in some of these cases, the Aztec perspective through the Spanish lens).

The victorious Spanish just replaced the Aztecs, though, and even kept their administrative districts in place for taxation. After a series of negotiations and battles, they set up headquarters in the Aztec capital of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, built on a dormant volcanic crater in Lake Texcoco. Broad causeways with aqueducts connected the mainland to this bustling island city of markets, zoos, and museum gardens. Today, the lake is drained and we know it as Mexico City.

Loyal Aztecs weren’t Cortés’ only foe. Before he could claim the area he had to contend with another band of Spaniards who landed ashore behind him in pursuit of gold. According to legend, Cortés begged the Aztecs, “Send me some of it, because I, and my companions, suffer from a disease of the heart which can be cured only with gold.”

Apocryphal or not, the quote captured the Spanish Conquest’s essence. A similar scenario played out in Pizzaro’s Incan conquest further south in the Peruvian Andes, with Atahualpa’s Incas being overrun by outnumbered Spanish with superior resources, and the Incas’ local support being undermined by having overrun earlier indigenous groups in Peru and Ecuador. The Spanish continued their search for precious metals throughout the continent and were the first Europeans to set foot on much of what’s now the southern United States. Animated Map Cabeza de Vaca was first into what’s now Texas, landing on Galveston Island in 1527. He attracted a large band of local followers as he made his way into New Mexico and back to Mexico, where these Native Americans were enslaved. Hernando de Soto was first into what’s now the Southeast, landing in Florida and exploring west as far as present-day Arkansas. You can begin to see one piece of our colonial jigsaw puzzle emerging in yellow below, though this map depicts 1750, including other French and British colonies that came later.

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado explored north into present-day Kansas in pursuit of Cevola, a purported city of gold, before slitting the throat of the man who sold him the bogus map. Coronado’s hungry group encountered Pueblo Indians near Taos, alienating them by eating cornmeal they put out as an offering for the Spring Solstice. Because Coronado found no gold or silver, remarking on the way that the Grand Canyon was the ugliest site he’d ever laid eyes on, the Spanish did not return to the Rio Grande Valley for another half-century. However, his own maps were crucial to the eventual Spanish settlement of the Southwest.

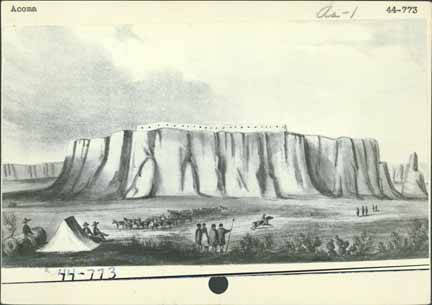

Juan de Oñate’s expedition returned north to the Rio Grande Valley from Mexico in 1598, performing plays re-enacting the Spanish Conquest of Aztecs for local tribes. It was cultural warfare intended to overcome the language barrier while showing Native Americans who was in charge. They met their fiercest resistance at a solitary butte in the desert west of Albuquerque called Acoma, or the “Sky Pueblo.” After an unsuccessful attempt to conquer the mesa in 1598, the Spanish returned in 1599 and decimated the village in the Battle of Acoma, killing, mutilating and/or enslaving its inhabitants. They rebuilt the town and a Catholic cathedral with the Spanish adobe-style of sun-baked mud bricks now familiar throughout New Mexico. Like Columbus, Oñate is a polarizing historical figure in the Southwest today because he, too, amputated the limbs of Native Americans who resisted his takeover. When local Hispanics celebrated the 400th anniversary of his expedition in 1998, some Indigenous Americans amputated Oñate’s limbs off statues with chainsaws.

Acoma, New Mexico, Original Lithograph for Report of J.W. Abert of “His Examination of New Mexico in the Years 1846-47” to the Secretary of War

Beyond initial explorers, most Spanish in the upper Rio Grande Valley were missionaries — Franciscan or Dominican monks — who meant no harm to the Pueblos but whose strict ideas about religion and sex met with a lukewarm reception. Most Native Americans never saw European women, children, or families. In 1680, in the midst of a horrible drought, frustrated Pueblos led by El Popé rose up and drove the Spanish out of the valley. However, they invited the Spanish back after a short period to resume trading and help them fend off Apaches, who had migrated into the area from Canada around 1000 CE, and Comanches, who had broken off from Shoshone tribes in Wyoming and come south in the 17th century (some Apaches had helped the Pueblos in the original revolt).

The late 17th century was a violent period in colonial American history. In New England, Algonquian Indians fought English settlers in King Philip’s War in 1675-78; and white and black indentured servants rose up against Native Americans and white planters in Virginia in Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, both of which you’ll read more about in coming chapters. The 1680 Pueblo Revolt marked the limits of Indian independence in the colonial age, at least in the Southwest. Native populations became so accustomed to white trade and military alliances that, in the space of a few generations, they struggled to get by without them. If this seems surprising, readers should envision themselves making a living the same way their great-grandparents did a century ago. For most of us that is a humbling thought and helps us grasp how Pueblos might have gotten used to iron tools and other European items by the late 17th century.

As for the Spanish, they had a vast American empire but bit off more than they could chew geographically, including the Spanish Main (mainland) and Caribbean islands. It was too vast to govern effectively. With no gold or silver discovered in the northern part of New Spain, most of today’s American Southwest remained sparsely populated with scattered Catholic missions and Spanish presidios (military garrisons) amidst small indigenous settlements. Part of New Spain’s problem was that their centralized political system required almost all decisions to flow through the monarchy in Toledo, Spain — a bureaucratic logjam in an age before instant communication. All trade, meanwhile, flowed through Seville, Spain, which created less of a bottleneck but was still inefficient. Another problem was the arid environment in much of New Spain, which didn’t lend itself to productive agriculture. Americans later discovered gold and silver in the Southwest, but it was too late by then to help Spain (or Mexico).

Nonetheless, New Spain posed a formidable obstacle for European and, later, American rivals. The first Europeans to settle in the future U.S. spoke Spanish and the oldest existing American towns are Spanish: St. Augustine, Florida (1565) and Santa Fe, New Mexico (1610).

As this Library of Congress map shows, almost all the major towns and cities of California’s coast were originally settled as Spanish missions, from San Diego to Sonoma. Most importantly, with few Spanish women in their early settlements, Spanish men helped forge a new Latino ethnicity by marrying Native American women. Technically, Hispanic is a linguistic term and also applies to Iberians, but is commonly used to describe people of Spanish ancestry in the Americas and Philippines. The relative degree of European and American or African blood mattered as mixed-blood Mestizos formed the middle class with Native Americans below and lighter-skinned Criollos and Spanish-born Peninsulares above. Religions also blended, as Aztec traditions merged with the Christian Allhallowtide (i.e. All Saint’s Day) to form the Mexican Day of the Dead.

The vast treasure Spaniards mined from the southern part of their empire changed history. For one, their newfound wealth motivated jealous rivals like England and the Netherlands to colonize, even as Spain was trying to conquer both countries back in Europe. Moreover, the injection of gold and silver into the European economy (aka the Price Revolution) caused inflation that hurt the poor and created new upper classes. Some monarchs, including England’s Henry VIII, compounded inflation by debasing coins, melting them down and diluting them with un-precious metals to make two coins, an early form of counterfeiting. The Spanish also imported lucrative red dye into Europe for the first time — carmine from American cochineal insects — sought after by painters, weavers, and cobblers. Silver became the world’s first global currency and the Spanish Pieces of Eight coat-of-arms symbol morphed into the familiar $. In the mid-16th century, the silver mining hub of Potosí, Bolivia was likely the fifth-biggest city in the Christian world, behind London, Naples, Venice, and Paris. Silver’s influx into Europe gave Europeans a leg up on Asian trade since silver was the default trading currency in China. Like art, science always follows the money, and, as we saw in the previous chapter, the most cutting-edge scientific research shifted from the Middle East to Western Europe. This shift triggered the long-term relative demise of the Middle East in relation to the West and the Scientific Revolution in Europe that impacted all history thereafter.

While plenty of precious metals filled royal coffers, more money in circulation contributed to the relative rise of merchants and bankers in relation to the traditional feudal landlords (aka nobility or aristocracy) who had dominated medieval Europe. Put simply, new money gained even more ground than old money, especially in cases where the aristocracy had rented land to peasants on long-term contracts inked before inflation set in. Upwardly-mobile merchants and bankers also benefited from improved technology, communications, and libertine rules regarding interest rates, as we saw in the previous chapter. With new money came power, or at least the desire for more power. The emerging bourgeoisie, or upper-middle class, demanded political representation, weakening the absolute grip of monarchies and helping to usher in an age of republican revolutions that coincided with the rise of capitalism. In this indirect but important way, precious metals mined in America changed European history and set in motion more American settlement and its own evolving brand of democratic capitalism. NOTE: remember to distinguish between republicanism with a small-r, meaning representative government, and capital-R Republican referring to the modern American political party.

New France

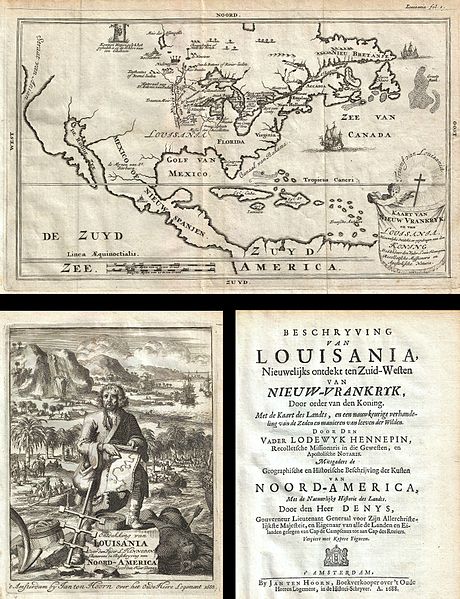

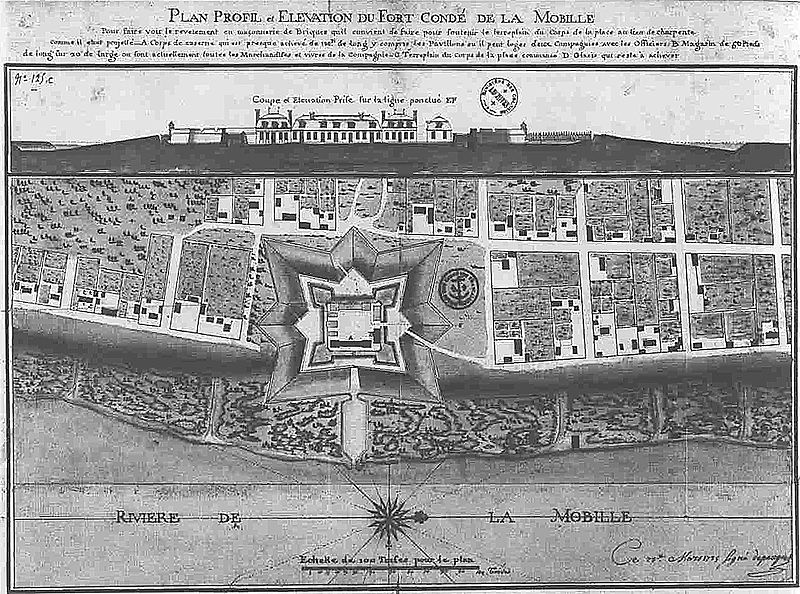

For a century before the arrival of the English or Dutch, Spain’s main American rival was France. The French established colonies throughout the Caribbean basin including Guiana on the northern coast of South America, Louisiana (1682) and, to a lesser extent, Florida. Animated Map Their first main port was Mobile (Alabama) in 1702, where they built Fort Condé and where Mardi Gras originated before the colorful pageant’s center of gravity shifted west to New Orleans.

French colonizers were less aggressive toward Native Americans than other Europeans but, like the Spanish, they claimed a huge swath of land. Most of that territory was in the north, in the areas now encompassing eastern Canada, the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys of the current United States. Unlike Spain, where Catholic Christians closed ranks in opposition to Jews and Muslims, early modern France was racked with religious wars between Catholic and Protestant Christians that had a mixed impact on American colonization. Mostly the Religious Wars hampered their exploration efforts, but they also motivated emigration among Catholic missionaries and Protestants fleeing persecution.

Like the Dutch and English, French explorers led by Jacques Cartier (right) hoped to find a Northwest Passage to Asia through which they could sail west from Europe to Asia without leaving their boats. Cartier mapped the St. Lawrence River that connects the Atlantic to the interior Great Lakes. French Jesuit explorer Jacques Marquette mapped the entire coastline of present-day Michigan in the Great Lakes searching for the elusive Northwest Passage. Such a route does not exist, except through the Arctic Ocean during (increasingly longer) warm months, but the dream of a more southerly route didn’t die until Lewis & Clark discovered the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains in 1804. Still, explorers discovered and mapped much of North America in search of the ephemeral route, including the entire East Coast and much of the interior — and all with the aid of native guides and translators. French settlers established fur-trading posts along the St. Lawrence River Valley, including Quebec City and Montreal, and explored all the way down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. Marquette and Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle were the first Europeans to explore the Mississippi Valley. While the French managed Indian relations better than the Spanish or English, they still brought disease and disrupted the environment. In 1534, Cartier reported native crops and orchards lining the St. Lawrence; but they were overgrown, and villages abandoned, by the time Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec and New France in 1608. In 1624, Champlain remained convinced that the Great Lakes offered what translates to “means of reaching easily the Kingdom of China.”

Like the Dutch and English, French explorers led by Jacques Cartier (right) hoped to find a Northwest Passage to Asia through which they could sail west from Europe to Asia without leaving their boats. Cartier mapped the St. Lawrence River that connects the Atlantic to the interior Great Lakes. French Jesuit explorer Jacques Marquette mapped the entire coastline of present-day Michigan in the Great Lakes searching for the elusive Northwest Passage. Such a route does not exist, except through the Arctic Ocean during (increasingly longer) warm months, but the dream of a more southerly route didn’t die until Lewis & Clark discovered the Continental Divide in the Rocky Mountains in 1804. Still, explorers discovered and mapped much of North America in search of the ephemeral route, including the entire East Coast and much of the interior — and all with the aid of native guides and translators. French settlers established fur-trading posts along the St. Lawrence River Valley, including Quebec City and Montreal, and explored all the way down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. Marquette and Rene Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle were the first Europeans to explore the Mississippi Valley. While the French managed Indian relations better than the Spanish or English, they still brought disease and disrupted the environment. In 1534, Cartier reported native crops and orchards lining the St. Lawrence; but they were overgrown, and villages abandoned, by the time Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec and New France in 1608. In 1624, Champlain remained convinced that the Great Lakes offered what translates to “means of reaching easily the Kingdom of China.”

Nicholas Sanson, Amerique Septentrionale, 1650. This Was First Map To Show Great Lakes & Mississippi Tributaries

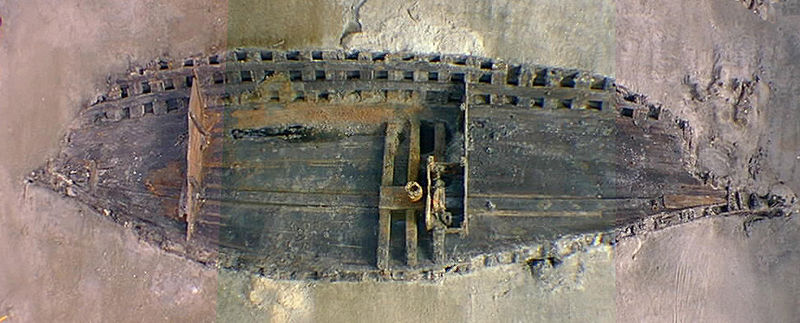

Subsequently, in 1684, La Salle tried to return to the Mississippi’s mouth from the Gulf side with four ships. Two were lost, one sailed for home, and they marooned the Belle off the coast in Matagorda Bay, near present-day Port Lavaca, Texas. The La Salle Expedition crew struggled to survive as they explored from their base, Fort Saint Louis, at Garcitas Creek, in today’s Victoria County. Stealing canoes incurred the wrath of local Karankawa Indians. Eventually, the surviving settlers mutinied and killed La Salle in 1687.

Modern-day shrimpers caught their nets on La Belle’s wreckage and hauled off some of its best cannons. In the mid-1990s, the Texas Historical Commission and Texas A&M’s Nautical Archaeology department built a cofferdam around La Belle and excavated the dry site. Artifacts included weapons (muskets, knives, gunpowder, and early grenades called firepots), a smelting crucible, wooden combs, a barrel of iron axe-heads, brass hawk bells, rings with Catholic insignia, the trophy skull of a deer with intact antlers, silverware, full wine flasks, and one sailor with part of his brain preserved by the anaerobic environment (thick, muddy sediments at the bottom of the bay). Many of the items are on display at the Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin and the Corpus Christi Museum of Science & History (not the brain, which was removed to the Texas State Cemetery). It’s a small boat but they actually brought it over in parts on bigger ships to use in bays and rivers, then ended up using it at sea. La Salle’s mostly failed expedition was still enough to give the French their first claim on Texas and the Mississippi Valley and goaded the Spanish into further developing the area in order to fend off the French. At various times over the next centuries, Spanish and French were the first two of six flags that flew over Texas.

Further north in eastern Canada and the Ohio Valley, initially most French were either Jesuit (Society of Jesus) missionaries or forest runners (fur traders) that married Indian women, with farmers (Habitants or “Habs”) arriving later. Offspring of these mixed marriages were/are the Métis, a smaller-scale version of Mestizos or Criollos in Latin America. Lower-case metis, with no accent on the e, means any descendant of Indigenous American and European, not just French. A Mini Ice Age in the mid-17th century fueled demand for furs in Europe, boosting Canada’s economy. Despite these fur profits, Canada developed a reputation back home for being cold, remote, and irrelevant. The French Philosopher Voltaire dismissed it as “acres of snow.” While French came to this part of North America first, English settlers quickly outnumbered them to the east and southeast along the Atlantic seaboard (examine the map below with English in red, French in blue, Spanish in peach). French farming — traditional feudalism with rich barons or lords overseeing peasant sharecroppers — wasn’t easily exportable to America, partly because peasants would just run off into the woods to trade furs with Native Americans. As mostly traders and missionaries, the French had no need to take land for family farms, as the English did. Instead, they lived amongst the indigenous population and spoke their languages. The English had a strong feudal tradition, too, but their American settlers carved out a new economy in small-scale family farming and they brought families that reproduced, growing their population larger than the French Americans’. The English needed land for farms and took it from Native Americans that they had no real interest in beyond taking their territory. The English, in this case, better typified the model of settler colonialism trending in modern historiography.

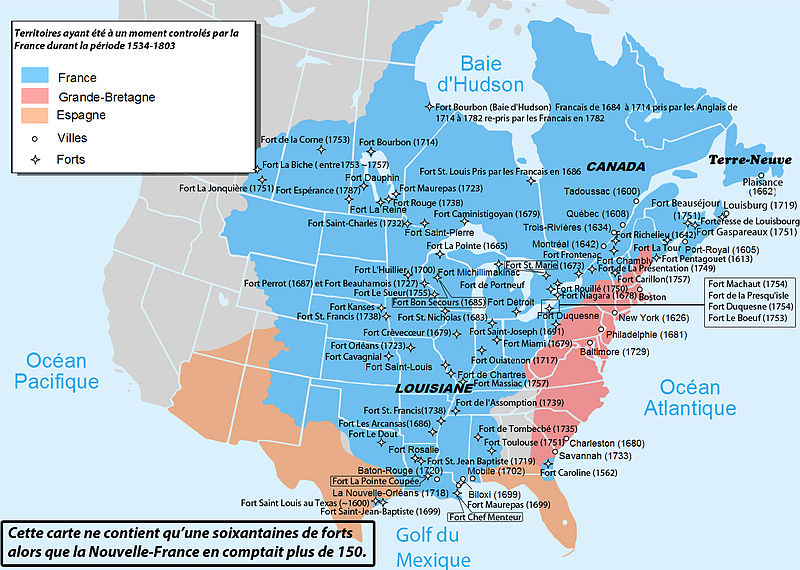

This modern map shows French claims in North America at their high-water mark, the second geographical piece of today’s colonial jigsaw puzzle. But remember that most historical maps just show European claims on America, ignoring that most of the interior, other than a few colonial outposts, was controlled by Native Americans. Maps don’t come to mind as quickly as weapons, boats or religious privilege, but Europeans wouldn’t have conquered big swaths of the world without them.

The French were more concerned than the English with converting Native Americans to Christianity. Jesuit Black Robes, as Algonquians called them, sent home letters to their superiors, bound and preserved for future historians in the multi-volume Jesuit Relations. Missionaries had a stake in exaggerating their success at conversions, but these primary sources nonetheless reveal a lot. It’s evident, for one thing, that the Pays d’en Haut — “upper ground” or Great Lakes area — was more an arena of trade and diplomacy than simple conflict, though there was plenty of violent torture, dismemberment, and death as well. A key factor was the English presence to the east that Indigenous Americans could manipulate for more favorable terms than they got later when dealing with only the English or Americans. The three respective parties (French, English, and Native Americans) triangulated the relationship as best they could in a complex web of shifting alliances, interspersed with gratuitous tit-for-tat violence and occasional wars. The British even tried to exterminate some French-allied populations, as when they put bounties on the scalps of Mi ‘ kmaq men, women, and children in Nova Scotia in 1749. The bigger conflicts occurred whenever England and France fought in Europe, which was quite often over the course of the late 17th and 18th centuries. Thus, colonial history is marked with a series of engagements, including King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War, and King George’s War, that didn’t significantly alter the territorial claims in North America because they happened before English colonies on the Atlantic encroached on French settlers in the St. Lawrence Valley.

George Washington In His Redcoat-Wearing Days (or at least red vest-wearing) As Colonel of the [British] Virginia Regiment, Painting by Charles Willson Peale, Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington & Lee University

This last of the Imperial Wars, known in America as the French & Indian War, was just one theater in the global Seven Years’ War that the British, French, and other Europeans fought across the West Indies/South America, India, Africa, and Asia (the Philippines). In North America, the British got off to a troubling start. Ignoring the advice of Americans familiar with Indian warfare, the British and their skeptical colonial subjects under Edward Braddock marched west across Pennsylvania toward Ft. Duquesne in bright red uniforms with drums and bugles announcing their every move. British soldiers wore their namesake “redcoats” to mitigate friendly fire amidst cannon and musket smoke. In this case, though, bemused Indian scouts working with the French easily tracked them on both sides. As the British spread out to cross the Monongahela River a coalition of Native Americans pinched them in a crossfire that destroyed almost their entire army, including Braddock, who took a musket ball in the lung. Daniel Boone and Washington (Braddock’s aide) were among those colonials lucky enough to escape. Washington was nicked several times but didn’t sustain any serious injuries. Meanwhile, Ben Franklin marched an army, including his son, to Lehigh Gap outside Philadelphia to rebuild forts that helped protect that city.

Braddock’s Defeat was one of the most inglorious in English-British military history but it taught them the importance of Native Americans. Prior to their siege of Fort Duquesne (later Fort Pitt), they feigned friendship with the Delawares and gave them blankets infected with smallpox. Colonel Henry Bouquet wrote to General Jeffrey Amherst, “I will try to inoculate the bastards with some blankets that may fall into their hands, and take care not to catch the disease myself.” Amherst approved along “with any other method that can serve to extirpate the execrable race.” Some captains traded infected blankets and handkerchiefs to Delawares, but it’s unclear how effective their germ warfare was since there was a lot of the disease in the area already.

Mostly, the British just bought off enough tribes to swing more alliances in their favor. They used their superior navy to blockade Atlantic entry to the St. Lawrence River, cutting off French trade to their Indian allies. The blockade proved decisive. The British captured Fort Ticonderoga in upper New York and the North American portion of the war more or less ended in 1759 when the British snuck up the cliffs behind French forces defending Quebec and seized that capital city. The next year they seized Montreal. Global conflict between the British and French continued through 1763, with the British ultimately pushing French colonial traders out of India. Meanwhile, French settlers escaping the island of Acadia, now in the Maritime Provinces, found refuge elsewhere in the French empire: southern Louisiana. There they created the distinct Cajun culture that remained largely isolated from the outside world until the 1930s. Today, Cajun Country is sometimes called Acadiana (flag on right).

Mostly, the British just bought off enough tribes to swing more alliances in their favor. They used their superior navy to blockade Atlantic entry to the St. Lawrence River, cutting off French trade to their Indian allies. The blockade proved decisive. The British captured Fort Ticonderoga in upper New York and the North American portion of the war more or less ended in 1759 when the British snuck up the cliffs behind French forces defending Quebec and seized that capital city. The next year they seized Montreal. Global conflict between the British and French continued through 1763, with the British ultimately pushing French colonial traders out of India. Meanwhile, French settlers escaping the island of Acadia, now in the Maritime Provinces, found refuge elsewhere in the French empire: southern Louisiana. There they created the distinct Cajun culture that remained largely isolated from the outside world until the 1930s. Today, Cajun Country is sometimes called Acadiana (flag on right).

North America was British as of 1763, but most French-American citizens stayed in Canada. Today, Quebec is still French-speaking, though most Québécois are bilingual. However, Britain’s costly victory had to be paid for somehow. From British Parliament’s perspective, American colonials had never been taxed and it was time for them to start paying their way, given how long and costly the effort had been to defend them from the French. British Americans argued that the war had been for Britain’s benefit, not theirs, and lack of representation in Parliament exempted them from being taxed. Thus began a series of disputes over taxes that culminated in rebellion against British authority in America — one that would ironically prove successful for the colonists because of French aid. Before we get to the Revolutionary War, though, we’ll examine the 17th and 18th-century British colonies in more detail.

Optional Reading & Listening:

Backstory, “1492: Columbus in American Memory” (Virginia Foundation for the Humanities)

Edmund Morgan, “Columbus’ Confusion About the New World,” Smithsonian (10.2009)

Joyce Appleby, “The True Value of Columbus’s Voyage,” History News Network (10.2013)

Sixteenth-Century Spanish Maps From Americas @ UT’s Blanton Museum (NPR)

Anne Twinum, “Purchasing Whiteness: Race & Status in Colonial Latin America,” Not Even Past (UT History Dept.)