“Almost every achievement contains within its success the seeds of a future problem”

— U.S. Secretary of State James Baker on America’s Cold War victory

NATO conducted war games in Europe at the same time each year, so the Soviets knew they were exercises rather than a real attack. But a number of factors changed in 1983, including new leadership in Moscow, different radio communications by NATO, the arrival of new Pershing II missiles in Europe, and ongoing deterioration in U.S.-Soviet relations worsened by the recent downing of a South Korean airliner over Soviet air space. Consequently, the comrades entrusted with defending the Soviet Union were on edge that November before NATO’s Operation Able Archer 83. The Soviets didn’t know NATO’s mock attack was a drill and, according to some sources at least, they nearly retaliated with a real strike. They sent spy planes over Western Europe gauging the situation and the American Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, Leonard Perroots, didn’t respond to that provocation. The CIA had lost some faith in their pals at British MI6 after one of their spies, Kim Philby, fed secrets to the Soviets and defected to the USSR. But “Her Majesty’s Secret Service” played a key role here because one of its double agents working in the Soviets’ London embassy, Oleg Gordievsky, warned them that the Soviets mistakenly thought NATO was launching a preemptive attack. They quickly relayed that to the U.S., who scaled down the exercise. A Presidential Advisory Board investigation declassified in 2015 concluded that Perroots made a “fortuitous if ill-informed” decision to defuse the situation. Able Archer mirrored incidents when an American technician accidentally loaded a simulated Soviet attack into NORAD’s computer system in 1979 and another in 1980 when a worn-out computer chip caused a glitch, both causing momentary panic and confusion and triggering initial retaliatory protocol (NSA archives).

Some CIA sources claimed the Able Archer incident was overblown while other spies went so far as to say we nearly had World War III on our hands and were only spared by malfunctioning equipment. If the truth was somewhere in between, this was the closest the Americans and Soviets had come to a nuclear showdown since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Or, at least it was the closest we’d come since six weeks earlier when there was yet another close call. In September, Soviet radar indicated that seven American Minuteman ICBM’s were headed for the USSR. Luckily, Lt. Col. Stanislav Petrov suspected it might be a false read since there would be hundreds of missiles in the event of a preemptive strike, not a handful. Instead of reporting up the chain of command, which might have led to World War III, he investigated the situation and learned that the system malfunctioned because of sun rays bouncing off a rare alignment of high altitude clouds combined with the vernal equinox and complications over their satellite’s Molniya (elliptical) orbit. Cross-referencing a geostationary satellite confirmed that there were no missiles.

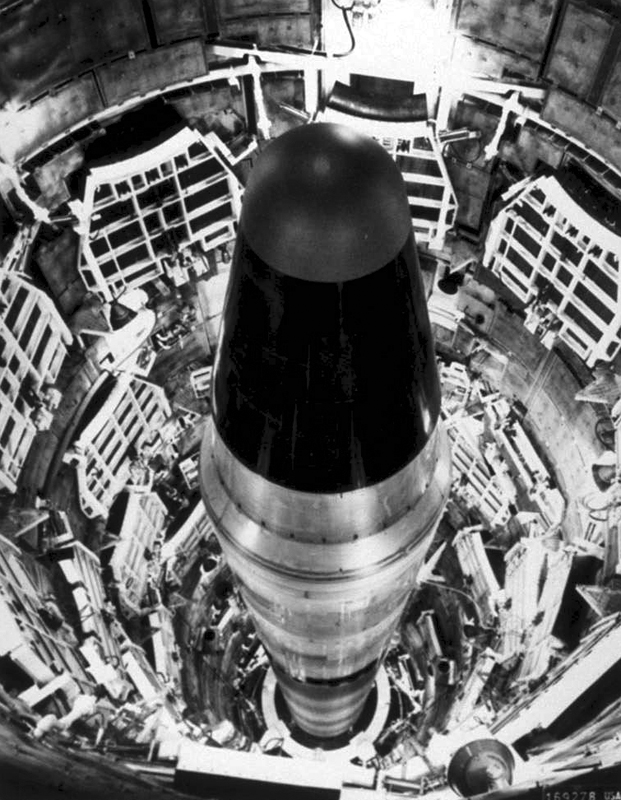

In 1980, a mechanic ruptured the fuel tank on a Titan II missile at the Damascus, Arkansas launch facility merely by dropping an 8-lb. socket off a ratchet 70 feet onto the thrust mount, from which it ricocheted into the skin of the tank, causing a fuel leak that filled the silo with vapors. If heat had expanded one of the two oxidizer tanks enough to rupture it, it might’ve set off a big enough explosion to detonate the hydrogen bomb. The missile also needed enough pressure in its leaking fuel tank to prevent collapsing on top of itself, which would’ve triggered a similar chain of events. Opening the silo hatch released dangerous fuel vapors but created the possibility of accidentally launching the warhead who knows where. As it turns out, hours later an explosion sent the warhead flying into a nearby ditch but, luckily, it didn’t detonate because it separated from its power source. If it had detonated, a blast 6x larger than Hiroshima would’ve decimated Little Rock and dropped radioactive fallout in whichever direction the wind blew. America’s Titan II’s were its most powerful warheads and bargaining chips, but there were numerous incidents with fuel leaks (10 in Arkansas and 17 in Kansas), killing dozens of workers.

Just as the movie China Syndrome coincided with the Three Mile Island nuclear accident a few years before, these Broken Arrows (near accidents) preceded a made-for-TV movie about nuclear war, The Day After; except that this time the 100 million Americans terrified by the fiction were blissfully unaware of the near-misses that transpired earlier that fall and in preceding years. But Able Archer seemed to change America’s new president, Ronald Reagan. Reagan was an outspoken critic of the Red Menace, once saying “a communist is someone who reads Lenin and Marx; an anti-communist is someone who understands Lenin and Marx.” When he first ran for office in 1980, he was full of talk about the Soviet “evil empire” and almost seemed to relish an apocalyptic showdown. He purportedly believed that the New Testament Book of Revelation predicted Armageddon between the Eagle and Bear, the respective symbols of the U.S. and Soviet Union. His inflammatory rhetoric was one of the reasons, in fact, that the Soviets half-expected the Americans to launch a preemptive attack, making the near-misses all the more frightening. But Reagan toned down his rhetoric after Able Archer.

Earlier, in a 1980 interview with the Washington Post, Reagan offered a more calculating and down-to-earth reason for his strategy of dropping the détente strategy of co-existence, instead trying to win the Cold War outright: that the Soviet economy couldn’t keep up with the U.S. in another arms race. The U.S. would go into debt, too (and did), but was Reagan correct that the Soviet Union would go out of business altogether trying to keep up? The opening of Soviet archives after the Cold War revealed that, while Reagan’s arms buildup did indeed alarm the Soviets, it didn’t cause any changes in their military spending; their economic problems were more fundamental than a high military budget.

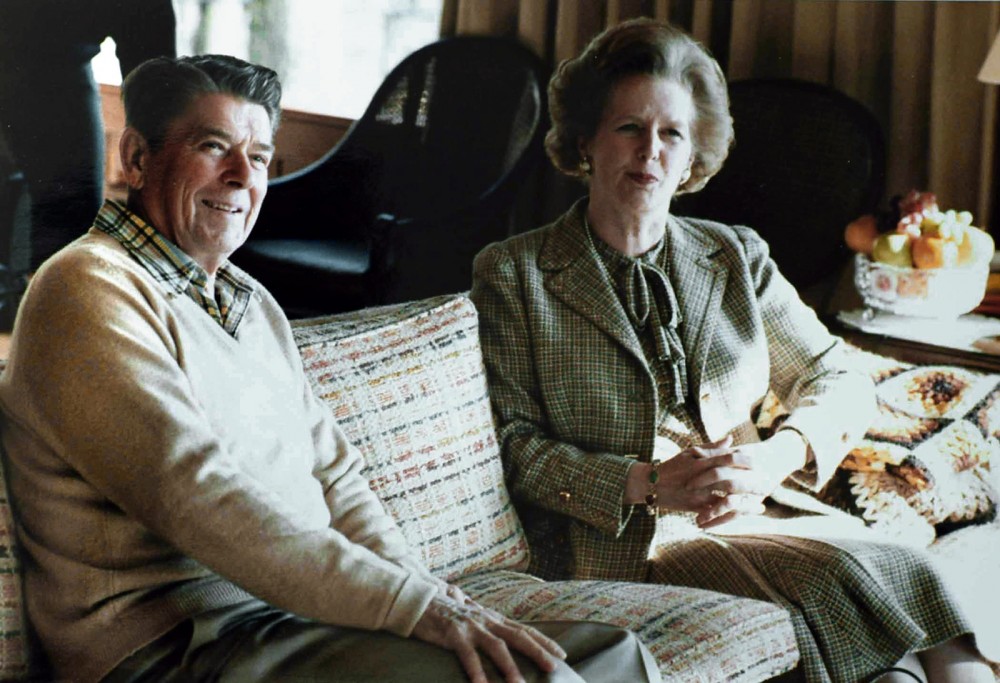

Ronald Reagan & British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher @ Camp David, 1984, White House Photographic Office

Each country was spending more than they had previously on intermediate-range missiles in Europe. America bought Pershing missiles for NATO-allied countries to oppose the SS-20 Sabers Soviets aimed at Western Europe. Jimmy Carter (D) spearheaded NATO’s “double-track” counter-move in 1979. Reagan (R) followed through with the support of conservative British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, French socialist President Francois Mitterrand, near-left German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and, after 1982, near-right Chancellor Helmut Kohl. Reagan promised to withdraw the NATO weapons if the Soviets did likewise. Though feared as too provocative by many liberals in Europe and the U.S., especially after Reagan took over from Carter, the Pershings led to a negotiated withdrawal of intermediate-range ballistic missiles on both sides of the Iron Curtain in a 1987 treaty.

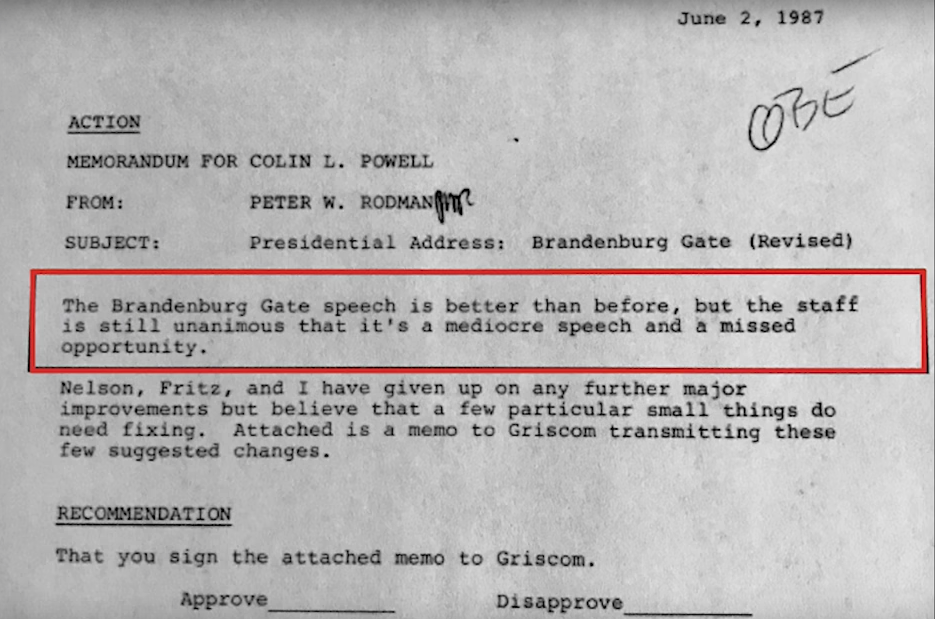

Ronald Reagan Speaking @ the Brandenburg Gate and the Berlin Wall, 1987, Reagan Presidential Library

As Reagan employed the peace-through-strength strategy, he also became less openly confrontational. He still liked to rattle the Soviets’ cage and, at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate in 1987, he famously told “Mr. Gorbachev” to “tear down this wall” in reference to the concrete barrier that separated Berlin’s eastern and western sectors. But, in his second term, Reagan became more measured in his speech, no longer talked about the Soviets as evil, and was more willing to talk arms reduction. Instead of sending in American troops to help the Polish Solidarity movement stand up to Soviet repression, he held back and sent money and communications equipment. Reagan’s now-iconic Brandenburg Gate speech almost never happened, as some people in the state department didn’t approve of writer Peter Robinson’s draft because it was too forceful and they didn’t want to disrupt the progress started at meetings in Reykjavik, Iceland in 1985 and ’86, when they laid the groundwork for medium-range missile reduction in Europe.

In 1985, a change in Soviet leadership opened an opportunity for more constructive dialogue than at any time since the Cold War started. In a 1987 United Nations speech, Reagan relayed that he and new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev discussed how well the two countries might cooperate if faced with an invasion of aliens from another planet. Neither the Right nor Left knew quite what to make of it all, with the Left accustomed to seeing Reagan as an Armageddon-seeking cowboy reactionary. Meanwhile, having over-learned and oversimplified the Lessons of Munich (Chapter 10), many conservatives were hesitant to endorse any foreign policy more dovish than perpetual antagonism. They leveled the same criticism at Nixon for normalizing relations with China in the early 1970s. But Reagan’s approach worked well. At the United Nations in 1988, Gorbachev announced that the Soviets were no longer interested in a military confrontation with the U.S. and that they were withdrawing troops from Eastern Europe.

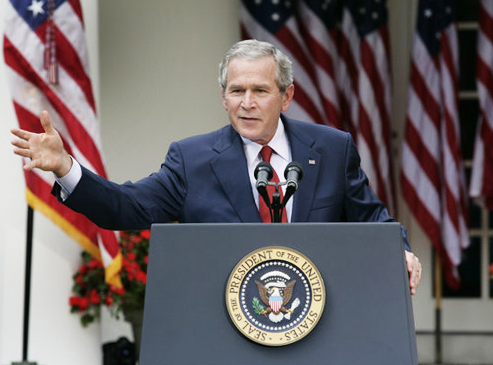

Reagan’s peace-through-strength strategy helped pave the way for the more constructive dialogue that ensued, but the causation isn’t as obvious as it may seem. As mentioned, the Soviets were threatened by Reagan’s military build-up, but there’s no direct evidence showing that it caused them to increase their military spending or raise the white flag of surrender. The USSR was struggling mightily for other reasons, including its weak economy and misguided venture into Afghanistan. What we do know is that Reagan and Gorbachev forged a constructive relationship that helped the two powers end the half-century-long Cold War in 1989. Then the Soviet Union collapsed altogether in 1991. It was left to Reagan’s successors to formulate America’s foreign policy in the new, but still dangerous post-Cold War world. His immediate successor, George H.W. Bush, called the new dynamic and vaguely defined new policy the New World Order, from H.G. Wells’ 1940 book that promoted a global legal system to bring about world peace. In a January 1991 State-of-the-Union address, Bush anticipated a New World Order in which diverse nations would be drawn together through a commitment to peace, security, and rule of law. However, his son, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump didn’t embrace his vision of American-led multilateral alliances like the United Nations and NATO.

The Middle East, Latin America & Afghanistan

Reagan had other foreign policy concerns. He wanted to fund right-wing guerrilla armies in Central America, exercising the authority perhaps implied but not stated under Teddy Roosevelt’s 1904 Corollary whereby the U.S. could overthrow and replace whichever governments it chose in Latin America to align them with U.S. interests. But Congress disagreed, wanting to avoid another potential quagmire so soon after Vietnam and blocked Reagan’s initiatives, other than an invasion of Grenada in 1983. Unlike many Cold War interventions, the Organization of American States requested the Grenada intervention and it led to constitutional government on that Caribbean island.

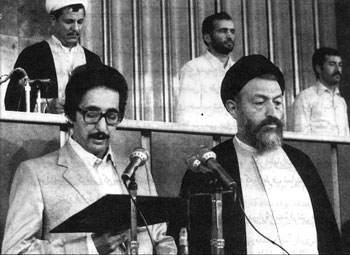

Additionally, Reagan wanted to pay Iranians ransom in the form of Israeli weapons to release more American hostages being held in Lebanon by a group Iran influenced called Hezbollah. The U.S., though, was formally embargoing Iran and giving weapons to its enemy, Iraq. Reagan was adamant about not negotiating with kidnappers during the 1980 campaign, but many suspected his camp negotiated with Iran even then to delay the release of the earlier, larger and more famous group of 52 hostages we read about in Chapter 20. Iran had been negotiating with Carter for their release earlier that fall and those talks broke down inexplicably, with Carter announcing they wouldn’t be released until after the election. For some reason, maybe just to punish Carter and not because of any extra deal with Reagan, Iran finally released those hostages twenty minutes after Reagan was sworn in as president in January 1981 as befuddled Americans watched both events simultaneously on a split screen. Reagan unfroze Iranian financial assets in the U.S. but Carter was also willing to do that and Carter was up all night negotiating with Iran just before Reagan’s inauguration. Reagan’s purported ploy was to prevent his opponent, incumbent Jimmy Carter, from getting an “October Surprise” boost at the polls just before the election. Reagan’s camp at the time included former and disgruntled OSS/CIA officials with good connections, including campaign director William Casey, even though Reagan wasn’t yet an elected official. Tampering with foreign policy as a private citizen, especially to the detriment of American hostages, is a serious charge — a felony under the Logan Act — that no one pinned on Reagan or his staff. In the early 1990s, both houses of Congress and several publications including Newsweek, Village Voice, and New Republic found no conclusive evidence supporting the claim and moreover debunked specific details of the October Surprise Conspiracy Theory, but PBS Frontline “debunked the debunkers” the following year, while still concluding that the evidence was murky and Americans would likely never know the full truth.

There is testimony suggesting that a deal was struck, including that from Reagan/Bush staffer Barbara Honegger and Iranians. After he was no longer under indictment and had no motive to plea bargain, arms dealer Djamshid Hashemi said he participated in the meetings, and Iranian president Abolhassan Bani-Sadr later insisted that they were negotiating with both campaigns, Carter’s and Reagan’s, and that Reagan’s camp even threatened him personally if they didn’t accept their deal of delaying the hostage release in exchange for unfreezing Iranian assets in U.S. banks and shipping weapons from Israel to Iran. The weapons deal did, in fact, happen later in the decade. Thirteen hostages sued the Reagan campaign for the delay, to no avail. Reagan said that his campaign staff did, indeed, negotiate with Iranians during the election not to delay their release, but rather to strike a deal to get them released as soon as possible. If he succeeded because he was offering weapons and to unfreeze assets while Carter was only offering to unfreeze assets, that explains why Iran released the hostages when Reagan was sworn in. In other words, Reagan’s camp might have inadvertently delayed the hostages’ release by outbidding Carter and offering a better deal even if that wasn’t their specific intention. More likely, they outbid Carter and secured the delay. Even the more innocent interpretation is a good example of why the Logan Act is wise insofar as America should discourage its private citizens from engaging in foreign policy, including the run-up to elections and interim between elections and inaugurations. Either way, serious negotiations didn’t begin until Carter lost the election to Reagan.

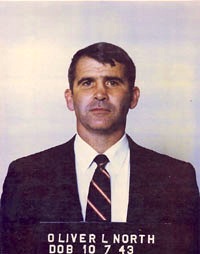

Whatever happened, Iran concluded that Reagan would negotiate if they took more hostages, so they subsequently aided Hezbollah terrorists in doing just that in Lebanon in 1984. These were the hostages that Reagan’s staff tried to get out by sending American-made weapons from Israel to Iran, leading to the Iran-Contra scandal. To kill two birds with one stone — Middle Eastern hostage release and aid to Central American guerrillas — the Reagan administration used a secret CIA cell to sell weapons to Iran (via Israel) in exchange for the hostages in Lebanon and payments. They laundered the money through Swiss banks before sending it to the Contra Rebels who were trying to overthrow the Sandinista socialist democracy in Nicaragua. The right-wing rebels had been relying on private funding (e.g., Joseph Coors), but Reagan went around the back of Congress and the public with the Iranian money, which didn’t make either happy when they found out about it. The Contras had a nasty reputation for kidnapping, torture, assassinations, and drug dealing, despite Reagan’s attempts to compare them to the Founding Fathers. The Contras’ opposition to democracy strained the comparison further.

When news got out about the Iran-Contra Affair in 1986, Reagan’s approval ratings plummeted, just as his own mental health was beginning to deteriorate with the early effects of Alzheimer’s disease. Reagan either authorized the plan, meaning he’d deceived the public, or he didn’t know about it, meaning he wasn’t in charge of his administration. In March 1987, Reagan addressed the nation, saying “a few months ago I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and my best intentions still tell me that’s true, but the facts and evidence tell me it is not.” The Reagan faithful pinned the blame on his VP, George H.W. Bush, contributing to a rift between the Reagans and Bushes. Like Watergate, some of the culprits involved with the scandal used the exposure from the controversy to catapult their careers, including Marine officer Oliver North, who went on to become a popular conservative commentator, author, politician, and president of the NRA.

Iraqi President Saddam Hussein Greets Donald Rumsfeld, Reagan’s Special Envoy, in Baghdad, 1983, CNN

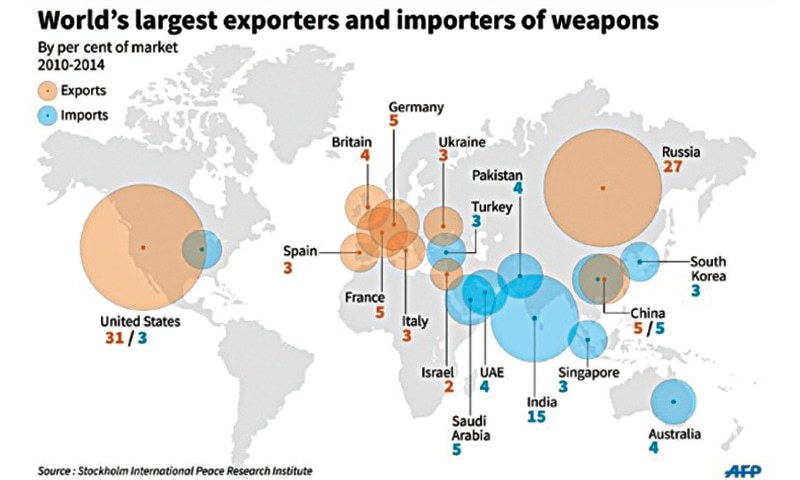

In 1983, the Reagan administration supplied Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein with weapons in his war against Iran. It was common for the U.S. to sell weapons to both sides in a war, the justification being that, if they didn’t, someone else would anyway. The chart above shows that the U.S. remains active in arms sales. Hussein was a dictator who’d alienated the West by nationalizing his country’s oil in 1972, meaning they booted out western oil companies and took over production. As director of the oil program, he skimmed profits and used them to systematically eliminate his rivals. The British and French had created Iraq arbitrarily on a map during World War I with the Sykes-Picot Agreement, partly to develop its oil. Britain was updating its Royal Navy from coal-fired steamers and needed oil it didn’t otherwise have much of. In the 1980s, common enemies made for strange bedfellows, and the U.S. supported Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88, even supplying Saddam with chemical weapons to supplement those they’d manufactured on their own.

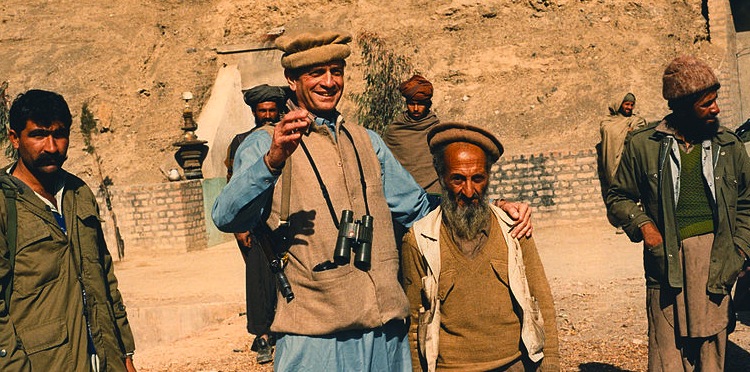

Further east, the U.S. was doing what it could to help Afghans repel the Soviets. Reagan’s U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick was famous for her doctrine of supporting any dictatorship, however brutal, as long as they shared America’s anti-communist leanings. In theory, the ally in question could eventually learn from America’s example and move toward democracy. That was in keeping with Cold War policy dating back to the Eisenhower administration and could apply to insurgents as well as dictators.

The CIA funded the Mujahideen resistance in Operation Cyclone (1979-89), one of the largest covert operations in American history. Through the back-channel dealings of Texas Congressman “Good Time” Charlie Wilson, the CIA delivered to insurgents anti-tank missiles and the handheld anti-aircraft artillery (stinger missiles) they needed to shoot down Soviet planes and helicopters. The Afghans’ victory ultimately helped bring down the Soviet Union and end the Cold War, though Gorbachev had already decided to withdraw Soviet troops before American aid kicked in.

But there was a fly in the ointment. The CIA had empowered anti-Western rebels that morphed indirectly into the Taliban over the next twenty years, though at first the Mujahideen fought against the Taliban. Wilson later conceded that the U.S. probably should’ve followed through in Afghanistan more after the Soviets left, developing a better relationship with the Taliban militia that took over the country in 1996 and harbored al-Qaeda. Osama bin Laden was a veteran of the fight against the Soviets.

Cold War Ends

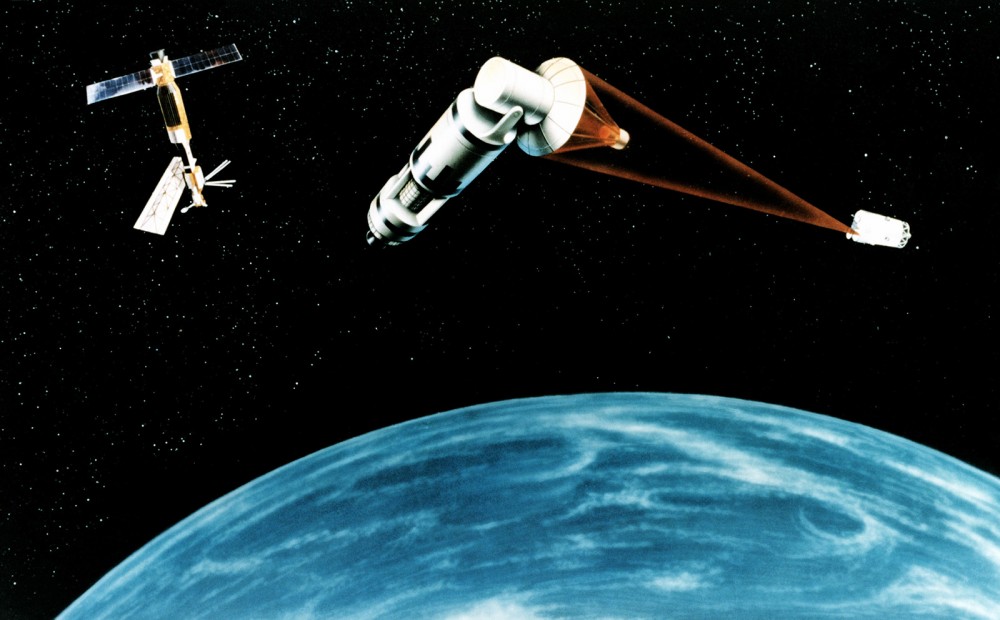

Reagan bounced back after the Iran-Contra Affair by continuing to pursue arms reduction with the Soviets. He was bargaining with power, as the U.S. had modernized its forces in the 1970s-80’s and the Soviets were worried that America would develop a missile shield of lasers, the Strategic Defense Initiative. Known informally as “Star Wars,” SDI was expensive, didn’t work, and lacked popularity, but Soviets took the threat seriously. Lead scientist Lowell Wood later called it technically feasible but impractical and “mainly for show…a feint that broke the enemy’s morale and treasury” (in 2015, Wood broke Thomas Edison’s American utility patent record of 1,084). NOTE: Weapons of mass destruction in space, as opposed to defense systems, are banned per the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, while the U.S. rejected a treaty banning traditional weapons in 2008 and Russia and China rejected a similar European Union proposal in 2014. In another case of strange bedfellows, Donald Trump and liberal astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson agreed on the need for the U.S. Space Force, founded in 2019.

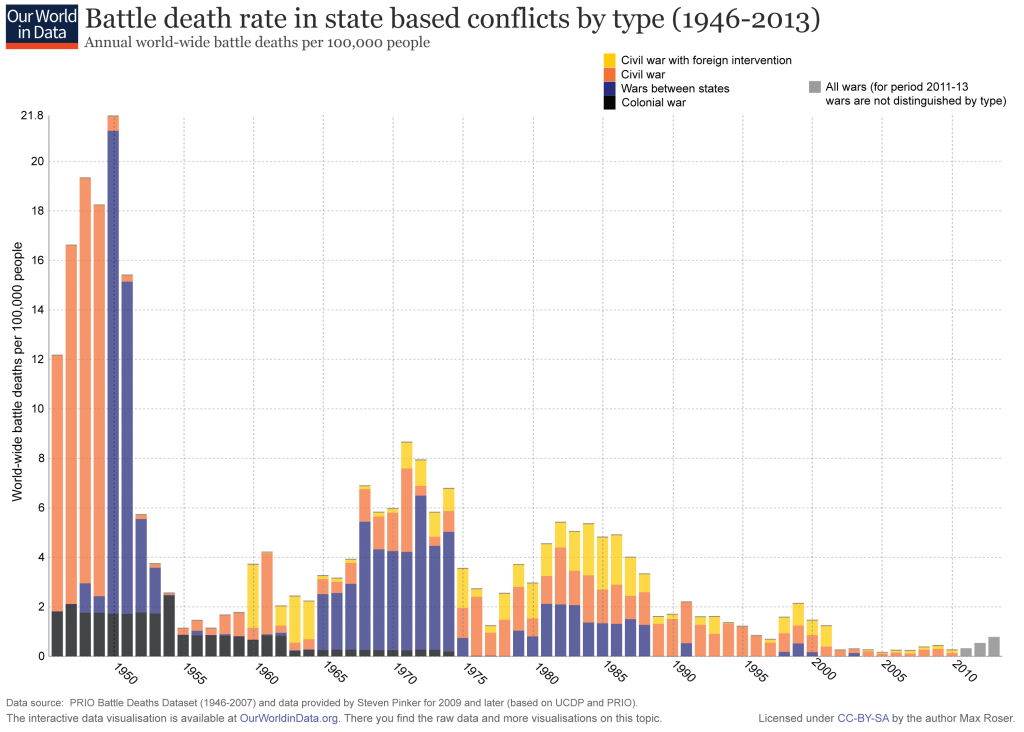

At home, Reagan’s emphasis on defensive weapons turned liberals into reborn advocates of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). As argued in this Rolling Stone article by William Greider in 1986, SDI might have upset the delicate balance of terror that had, in its own warped way, stabilized the world for decades, preventing major wars. Or it might lead to another arms race of new offensive weapons. Star Wars would have taken away the Soviets’ deterrent threat, especially if they didn’t share the technology. Or, if it had worked well, the Soviets might have stolen the technology the way they did with the atomic and hydrogen bombs, in which case the U.S. would have also lost its deterrent threat and we might have been back to settling our differences with machine guns, tanks, and napalm. Either way, Reagan wouldn’t back down on shelving the program and new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev cut his losses as best he could.

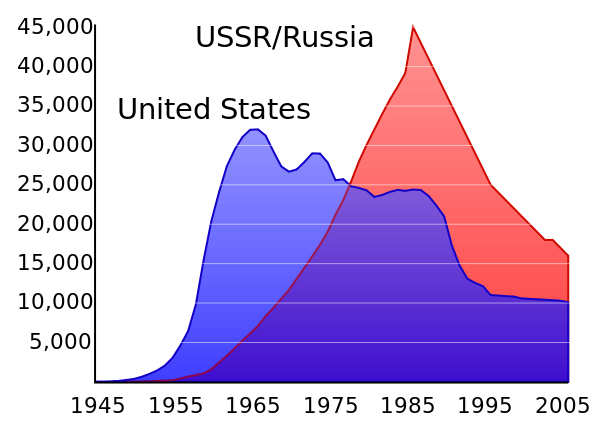

As we saw above, the U.S. and USSR removed their intermediate missiles in Europe and agreed to the right to inspect each other’s main arsenals. Reagan and Gorbachev’s most important meeting was the Reykjavík Summit in Iceland in late 1986. The table on the left shows that the Soviets had been continuing their long-term trend of spending a lot in the arms race just prior to signing the ensuing 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in Washington, D.C. The INF expired in February 2019 and the U.S. also pulled out of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABMT) in 2002, ostensibly to better defend themselves as targets from countries other than Russia like Iran or North Korea.

The graph also indicates that much of the defense spending in the Reagan era was on things other than nukes since America’s overall military spending rose despite cutbacks in missile development. Reagan was also the first president since Nixon to visit Moscow. He got flak from right-wing critics for negotiating with the Soviets, but the talks were constructive and saved the U.S. money. Even more important than largely symbolic arms reduction, big changes were underway within the Soviet Union and among its puppet states in Eastern Europe.

Ronald Reagan & Mikhail Gorbachev @ the First Summit in Geneva, Switzerland, 1985, Reagan Presidential Library

Gorbachev opened up the press some and allowed for some free-market play in the economy through his perestroika and glasnost programs. But the Soviet economic experiment was failing, unable to keep up without profit motives or access to information technology that provided big tailwinds for the West, despite their attempts to reverse-engineer consumer technology that the KGB smuggled out of Mexico. Soviet GDP shrunk 5% annually through the 1980s amidst double-digit inflation — an extreme case of stagflation. Despite the country’s enormous size and resources, its economy was roughly the size of Denmark’s. Communist countries might include citizens that are on board, but were/are obviously doing something unpopular when they had to build fences to keep people in rather than out. And the inclusion of the terms democratic and republic in their countries’ official names/acronyms was a PR concession to the popularity of letting people vote even though theirs couldn’t (e.g., USSR and twice each in GDR, DPRK). While the Soviets kept up with America in the arms and space race and performed well in Olympic sports and the fine arts, they underestimated the pull of Western consumerism that accelerated after World War II. In other words, they could build ICBMs but had no answer for IBMs, the Beatles, Levi’s® or bootleg VHS tapes. Young people behind the Iron Curtain yearned for American and British pop culture, even as liberal Western college students gravitated toward Marxism. The Catholic Church under Pope John Paul II started to push back against communist rule in Eastern Europe, also, especially in Poland, where Protestant evangelist Billy Graham missionized in tandem with Catholics.

Communication and soft power played a role, too. Soviet citizens were aware of their government’s control of information but could pick up Western broadcasts via shortwave (ham) radio. The government did what it could to jam broadcasts, but people found guilty of listening to British or American radio were usually just fined or suffered a job demotion rather than being imprisoned in Siberia the way they would’ve under Stalin. Reagan reinvigorated this ideological battle against communism that languished during détente. When he came into office Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty was still using 1940s vacuum tube technology and their towers were rusting. In the 1980s, the U.S. amplified intellectual dissidents like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Andrei Sakharov, and Václav Havel, who later became president of the Czech Republic. Their critique wasn’t the lack of consumer goods, but rather communist totalitarianism’s corruption, lawlessness, dishonesty, and brutality. Communication always impacts politics, just as it did with telegraphs during the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and social media during the 2011 Arab Spring.

Led by Lech Wałęsa’s Poland, Eastern Bloc countries Czechoslovakia and Romania cast off Soviet domination in 1989, and Gorbachev had already signaled that the Soviets would be ending their military occupation a year earlier. These revolutions culminated dramatically in the tearing down of the Berlin Wall and reunification of East and West Germany in 1990. A decade later, the European Market moved to establish a common currency, the Euro. It wasn’t simply a matter of the USSR trying and failing to hang on to Eastern Europe. Russians were as sick of the satellite countries as the satellites were of Russia because most of them were net economic liabilities. Russia subsidized them more than they contributed to the USSR, though these puppet governments did provide the Soviets a geographic buffer.

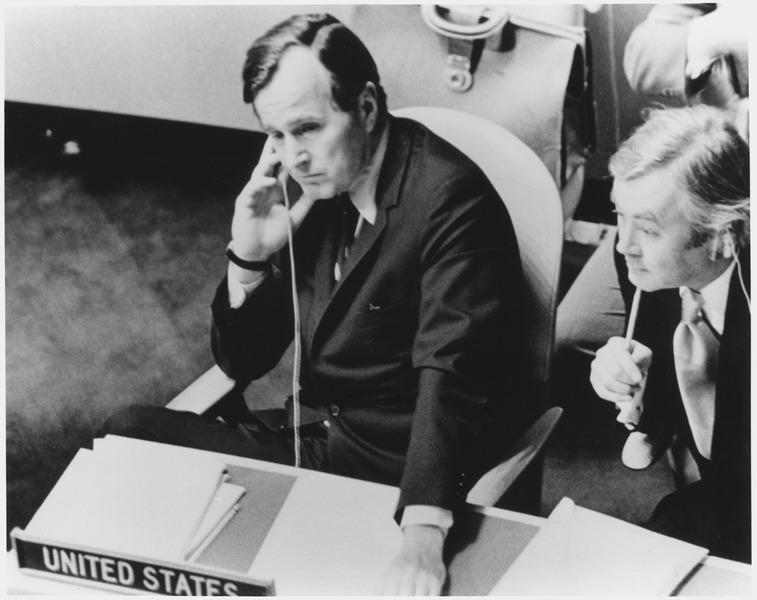

The Eastern Bloc’s disintegration was a lot to take in for the new U.S. President, George H.W. Bush — hereafter referred to as Bush 41 because he was the 41st president. But if anyone was qualified to deal with overseas affairs, it was Bush. He’d not only served in WWII but was director of the CIA and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Off the island of Malta in the Mediterranean, weeks after the Berlin Wall fell, Bush 41 and Gorbachev discussed future cooperation and declared the Cold War over. Their meeting is sometimes called the Seasick Summit because they met on ships anchored offshore in choppy seas. After 45 years and billions spent on defense budgets, one source of apocalyptic danger, at least, was diminished. Diplomat and co-architect of the containment strategy George Kennan (chapter 13) had been right all along: the strategy of holding ground and waiting for the Soviet economic experiment to fail from within had worked.

What happened next far exceeded what seemed to be a gradual and uniform relinquishing of Eastern Europe by the USSR. The Soviet Army decided to overthrow Gorbachev and reassert more traditional communist control, undoing his liberal reforms. They failed, but the man who stood up on their tanks and gave a confrontational speech to save the government was not the Soviet leader Gorbachev, but rather Boris Yeltsin, the President of Russia. Yeltsin came to power through popular elections. Russia was the main country within the Soviet Union, but the USSR also included Baltic countries (Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia), Georgia, Ukraine, Armenia, and big chunks of southern and northeastern Asia. As Yeltsin assumed leadership within Russia, the Soviet Union collapsed quickly and peacefully, and the rump state of Russia broke away on its own. In December 1991, ten countries within the former confederation, including Russia and Ukraine, formally announced that the USSR no longer existed, and Gorbachev resigned on Christmas. Amazingly, the CIA never saw the demise of the USSR coming, though various American journalists and academics had long predicted it. Reagan, for that matter, predicted the Soviets would be consigned to the “ashbin of history” in a speech before British Parliament in 1982.

Why it happened has been the subject of controversy ever since. Reagan supporters emphasize his hard-line stance and arms buildup, while others emphasize the structural weaknesses of the Soviet economy and, to a lesser extent, their disastrous foray into Afghanistan that lowered military morale and triggered a domestic drug epidemic. The truth is no doubt somewhere in between. More so than the wider public, professional historians are skeptical of theories that put too much weight on individual actions. They might look at the Revolutionary War, for instance, and argue that the U.S. didn’t win because George Washington was a great leader; rather, we think of George Washington as a great leader because the U.S. won the Revolutionary War for bigger reasons. Or they may look at media’s transformation (Chapter 20) and put more emphasis on technology and deregulation than individuals like Rush Limbaugh. Historians favor theories that emphasize interactions among many factors, agents, and forces, including the most overlooked factor of all: random luck. Just as the 15th-century Italian Machiavelli wrote about the tension between fortune and free will, modern historians focus on structural forces and individual agency. In this case, the structure was the long-term decline of communist economies, their lack of popularity among their own people, and their underestimation of how well capitalist democracies would appease their workers through incremental liberal reforms and compromises like entitlements, unionization, free public education, etc. Agency, on the other hand, was the individual actions of Reagan and Gorbachev. The individual agency vs. bigger context debate isn’t an either-or question, as causation runs in multiple directions. While it’s safe to say that most people outside the historical profession over-interpret individual actions to explain cause-and-effect, you can rest assured that Reagan’s liberal critics would’ve blamed him if things had gone awry with the Soviets in the 1980s. Likewise — though the topic isn’t nearly as important — conservatives quick to deny Barack Obama any credit for bringing down Osama bin Laden would’ve heaped scorn upon him had the Navy SEALs’ 2011 mission in Abbottabad, Pakistan gone awry for reasons outside his control.

Individual agency has some role in history, for sure, and, if it didn’t, we wouldn’t care who we elected. The U.S. presidency, in particular, is a powerful office on matters relating to war and foreign policy. We don’t call American presidents “leaders of the free world” for nothing. Reagan “standing tall in the saddle” (negotiating from strength) and then working constructively with Gorbachev was an important factor that influenced the demise of the USSR. Here’s more important food for thought: if Reagan’s initial hard-line “good vs. evil” stance was effective in this case, does that make it a surefire recipe for future success in other cases? If the same scenario popped up ten more times over the next few centuries, would Reagan’s work each time? On the other hand, would Kennedy’s restrained approach at the height of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis pay off ten times out of ten? We wouldn’t know the answer even if the scenarios were exactly the same as those of the early ’60s and late ’80s, let alone scenarios that will differ in the future. You can see that a panel of the hundred smartest historians on Earth wouldn’t be able to come up with any agreed-upon formulas to guide us into the future. We’re far better off knowing history than being ignorant of the past, but be wary of commentators drawing simple analogies between past and present-day events.

Individual agency has some role in history, for sure, and, if it didn’t, we wouldn’t care who we elected. The U.S. presidency, in particular, is a powerful office on matters relating to war and foreign policy. We don’t call American presidents “leaders of the free world” for nothing. Reagan “standing tall in the saddle” (negotiating from strength) and then working constructively with Gorbachev was an important factor that influenced the demise of the USSR. Here’s more important food for thought: if Reagan’s initial hard-line “good vs. evil” stance was effective in this case, does that make it a surefire recipe for future success in other cases? If the same scenario popped up ten more times over the next few centuries, would Reagan’s work each time? On the other hand, would Kennedy’s restrained approach at the height of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis pay off ten times out of ten? We wouldn’t know the answer even if the scenarios were exactly the same as those of the early ’60s and late ’80s, let alone scenarios that will differ in the future. You can see that a panel of the hundred smartest historians on Earth wouldn’t be able to come up with any agreed-upon formulas to guide us into the future. We’re far better off knowing history than being ignorant of the past, but be wary of commentators drawing simple analogies between past and present-day events.

In any event, Bush 41 wasn’t sure what to do at first when the USSR broke apart in 1991. Should he formally recognize Russia or wait to see if the Soviet Union reemerged? If the Soviets reasserted power after Bush recognized Russia, he’d be in an embarrassing situation and ruin the goodwill engendered at Malta with Gorbachev. In Kyiv, he’d even given a talk nicknamed the “Chicken Kiev speech” in which he cautioned Ukrainians against seeking independence, angering Ukrainian nationalists who declared independence soon thereafter. But Bush 41 eventually threw his weight behind Yeltsin and independence for all the Soviet republics (including Russia and Ukraine), Gorbachev retreated into retirement, and the USSR (1922-1991) was no more. Former communist leaders scooped up much of the wealth — the state had owned everything under communist rule — and Russia became a capitalist oligarchy and kleptocracy whereby thieves, in effect, took over the government to loot public money and steer government contracts into their own wallets. In a betrayal of democratic aspirations — and in an attack far more violent than Trump’s later January 6th Insurrection — Yeltsin had his tanks open fire on Russia’s parliament in 1993, killing 100 people, injuring 800, and ending the prospect of western-style separation of power.

Former KGB operative Vladimir Putin led the oligarchy after Yeltsin’s retirement in 1999-2000. After Bill Clinton met Putin in Moscow in 2000, he warned Yeltsin that Putin didn’t “have democracy in his heart,” poking Yeltsin’s heart to make his point. By the time Yeltsin died in 2007, he realized that Clinton was right and regretted having promoted Putin by making him head of the FSB (successor to the KGB), then prime minister and president. Putin gained notoriety and masculine photo-ops putting down a separatist uprising in the Russian province of Chechnya ordered by Yeltsin. Putin blamed a deadly series of apartment bombings in Moscow on Chechens, though they were likely false flag Reichstag fires used as a pretext for him to consolidate power.

Post-Cold War NATO & Trump-Putin

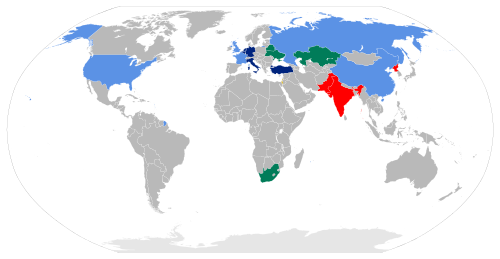

Would the multilateral alliance that formed in 1949 to counter Soviet expansion continue after the Cold War? If so, would NATO expand to include a unified Germany and former Warsaw Pact countries in Eastern Europe? Would Germany even unify, east and west, after the Cold War? Britain and France opposed German reunification, but Bush 41 and the U.S. supported it. In 1989, Lt. Col. Vladimir Putin was a young KGB counter-intelligence officer in Dresden, East Germany and returned home after the Cold War upset that Russia had lost its stature in the world. A decade later, he wrote that his resentment stemmed from negotiations over NATO.

NATO did expand but, in Putin’s view, the West promised that it wouldn’t during the negotiations for a Soviet withdrawal from East Germany. For many years, Western leaders insisted that they promised no such thing. We now know that the subject arose in negotiations between Gorbachev, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, and NATO Secretary-General Manfred Wörner (NSA Archives). In these talks, the West perhaps implied but did not promise in writing that NATO wouldn’t expand. West German foreign minister Dietrich Genscher said there would be no “expansion of NATO territory to the east, in other words, closer to the border of the Soviet Union.” Baker went furthest in these promises, guaranteeing how NATO troops wouldn’t expand “one inch” further east, but this was in the context of a February 1990 meeting specifically about if and when NATO troops would replace Soviet troops withdrawing from East Germany, not about the overall question of whether NATO would expand throughout Eastern Europe (including all the way up to Russia’s doorstep). According to Condoleezza Rice, then Soviet advisor to Bush 41, the National Security Council quickly reeled in Baker after this quote, which they realized might be misconstrued. Baker later admitted that “I may have been a little forward on my skis on that, but they changed it, and he (Gorbachev) knew that they changed it.” There was never a formal deal concerning NATO expansion and, later in 1990, Gorbachev continued to negotiate on the premise that they’d never formalized a deal even about East Germany, let alone the rest of Eastern Europe. But Gorbachev, normally friendly toward the West, said later that while Baker’s “one inch” talk was understood just in the context of East Germany, broader NATO expansion into Eastern Europe was a violation of the spirit of the statements and assurances made in 1990 (Brookings Institute). Boris Yeltsin, also relatively pro-American, likewise called NATO’s expansion into the former Warsaw Pact countries illegitimate. Yet, the concept that any newly-liberated country had the autonomy to decide NATO membership on its own was implicit in the German Unification Treaty of 1990. Either way, primary source documents indicate the negotiations in question were focused on Germany, not the rest of Europe.

But, as Putin conceded in a 2016 interview with American filmmaker Oliver Stone, the promise to not expand NATO “wasn’t enshrined in paper.” It may go down as one of the more infamous examples of the admonition to “get it in writing” because, instead, the formal agreement gave the newly-independent countries of Eastern Europe the freedom to form their own alliances and they increasingly chose the western alliances of NATO and the European Union (EU). Putin told Stone that primitive behavior on the Soviets’ part forced the West to form NATO in 1949, but that it no longer had any purpose other than the U.S. needing an enemy and client states in Europe.

In 1993, Bush 41’s outgoing administration never told Bill Clinton’s incoming administration about the controversial verbal quasi-promise to not expand NATO at the end of the Cold War. Most Eastern European countries eventually joined NATO which, in turn, insisted that they operate under Western guidelines of open elections, free markets, and civilian-military control in exchange for protection that has given them the breathing room for internal reform while minimizing the external Russian threat. The West brought much of the former Soviet Bloc, in other words, into the rules-based Liberal International Order. Meanwhile, NATO formed various agencies that fostered goodwill with Russia (e.g., NRC), but they were ineffective. Russian president Boris Yeltsin (1991-99) and then-former Secretary of State Baker briefly floated the idea that Russia itself should join NATO, to diffuse the tension altogether, but had they done that its members would’ve no doubt wondered why it still existed at all. But Gorbachev and Putin early in his career also briefly considered the idea of Russia joining NATO which, if nothing else, would’ve diffused the tension. Gorbachev thought a NATO-Warsaw Pact merger could reinforce the shared history of Soviets and the West defeating Nazi Germany.

In 1994, Bill Clinton’s team created the Partnership for Peace (above) as a kind of intermediary stage for NATO candidates where they’d have time become inter-operable with Western military, get their citizens’ feedback, and prepare to transition quickly, as Finland did in 2023 — kind of like the waiting room on Zoom. The PfP even included Russia though, in their case, not military coordination. It worried Clinton to “draw a new line” in Eastern Europe that left Ukraine on the Russian side, but bloodshed in Moscow compelled Eastern European countries to join while, at home, Clinton’s rival Newt Gingrich promoted expanding NATO Article 5 protection in his Contract With America. In 1997, Clinton pushed to expand NATO into Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia joined NATO, along with the Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), in the so-called “Big Bang” of 2004, followed by Albania and Croatia in 2008. NATO then pressed up against Russia’s borders, at least in the case of two of the Baltic States, but didn’t include Ukraine or Finland east of Scandinavia. As a senator and ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Joe Biden (D-DE) was instrumental in recruiting new countries into the pact.

In the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, signed by Russia, the U.S., and Britain, Ukraine gave up nuclear warheads in exchange for much-needed Western economic aid and a promise that Russia would respect its sovereignty, along with that of Belarus and Kazakhstan. This was no small matter as, when it declared independence in 1991, Ukraine became the third-biggest nuclear power on Earth, its 1250 warhead all aimed at the United States (there was also “loose nukes” in Belarus and Kazakhstan). Ukraine likely interpreted the U.S. as agreeing to defend them against Russia since the U.S. was anxious for them to give up their nukes. Ukraine got “assurances” in the Budapest Memorandum that America protect them from Russia, but no “guarantees.” This raised false hopes in Ukraine while simultaneously enraging Russia. At the 2008 NATO Summit in Bucharest, Romania, NATO pledged to someday include Ukraine and Georgia, leading to Russia’s brutal crackdown in Georgia, a former Soviet republic. Georgia ended up with a pro-Russian puppet government while Ukraine vacillated between the West and Russia for the next decade. Eventually both sides reached an informal, unsigned accommodation whereby Putin would respect Ukraine’s independence in exchange for NATO not arming Ukraine or newer NATO states. Putin cited his NATO grievances when Russia cracked down on democracy in Georgia in 2008 and invaded Crimea in 2014 after a pro-Western government took control of the rest of Ukraine a year earlier.

Putin brooked no dissent within Russia about their aggression toward Chechnya, Georgia, or Crimea, or disregard for liberalism widely defined: human rights, free speech, democracy, etc. In 2006, he celebrated his October 7th birthday by having democratically-leaning journalist Anna Politkovskaya killed. And he would love to break up NATO and the European Union and sow as much disunity as possible within the West through soft power like social media and hacking emails, and isolated violence like poisoning uncooperative foreign journalists. The less confidence Westerners have in their own core institutions — free elections, free press, courts, etc. — the stronger Putin’s case for authoritarianism within Russia. So, naturally, he prefers western leaders that erode citizens’ confidence in democracy by eroding their faith in elections and the media.

George Kennan (1904-2005), the original co-author of Cold War containment policy who thought creating NATO was “over-remembering Munich” (Chapter 13), said shortly before his death that NATO expansion in Eastern Europe was unnecessary and would only provoke Russia in the future, counter-productively making democracy there less likely. In his diary, Kennan wrote that it was clear the “Russians would not react wisely and moderately to the decision of NATO to extend its boundaries to the Russian frontiers…I would expect a strong militarization of Russian political life, to the tune of a great deal of historical exaggeration of the danger, and of falling back into the time-honored vision of Russia as the innocent object of the aggressive lust of a wicked and heretical world environment…There will be efforts by the Russian leadership to develop much closer relationships with Iran and China with a view to forming a strongly anti-Western military bloc as a counterweight to a NATO pressing for world domination…Thus will develop a wholly and even tragically unnecessary division between East and West and, in effect, a renewal of the Cold War.” Kennan could’ve added Syria as a smaller authoritarian ally.

Kennan’s prediction was prophetic, though we’ll never know whether Putin wouldn’t have invaded surrounding countries had NATO disbanded in 1991 or stood pat in the West. Perhaps he would’ve still fantasized about restoring a vast Russian sphere, especially after having spent hours poring over centuries-old maps in the Kremlin library during COVID-19. In the 2012 presidential debates, Barack Obama stressed that the Cold War was over, but Republican Mitt Romney rightfully countered that Putin was changing tactics, hardening his anti-Western stance. Russia sided with the Iranian and Syrian regimes at nearly every turn in opposition to the U.S. and West, though they’ve also sided at times with Iran’s enemy Saudi Arabia. Putin’s biggest obsession, though, was Ukraine (left, in green).

From 2015-19, Russian and rebel Ukrainian forces struggled for control of eastern Ukraine and, as mentioned, Russia conquered Crimea (in light green on the map) in 2014. In Foreign Affairs, an aging George Kennan accurately predicted that, after such aggression, proponents of NATO expansion would “say that we always told you that is how the Russians are,” thinking that danger justified expansion without realizing that NATO’s post-Cold War expansion was what caused Russian aggression in the first place — a self-fulfilling prophecy — and that very thing came to pass in 2022 when Putin invaded Ukraine. In this line of thinking, expanding NATO has undermined NATO’s purpose. Putin aired his usual grievances in 2022, vowing to kick NATO out of former Warsaw Pact countries (Eastern Europe) and vowing to get the U.S. out of Western Europe (i.e. disbanding NATO). Yet, instead of just emphasizing NATO in 2022, Putin unconvincingly and irrelevantly stressed “denazification” to justify the invasion. The revanchist Putin seemed intent, instead, on rebuilding the former Soviet empire or an even larger, historical Russian sphere, aka Russkiy Mir (Russian World), just because those territories were once Russian or its inhabitants speak Russian or similar dialects. Russian mercenary general Yevgeny Prigozhin, who contributed to the pro-Donald Trump social media blitz in 2016 by overseeing the Saint Petersburg troll farm (IRA) and led ex-convicts into battle on Putin’s behalf, undercut all of Putin’s justifications for the Ukrainian invasion, arguing instead that it was “so a bunch of animals could exult in glory.” Prigozhin had also done Putin’s dirty work in Syria and the Central African Republic (for diamonds and gold), having his deserters beaten to death with his trademark sledgehammer.

More background is in order here. Relations between Russia and the U.S. had been tense throughout the early 21st century. While Putin initially wanted to cooperate with Bush 43 against terrorism after 9/11, he suspected that America was meddling in Russian elections and was behind the Chechen uprisings and more Color Revolutions against Russian authority in Georgia (Rose), Kyrgyzstan (Tulip), and Ukraine (Orange) via NGO’s like the National Endowment for Democracy. George W. Bush openly promoted and encouraged democracy in Georgia. America purportedly spent about $5 billion to successfully promote democracy in Ukraine, an adjacent country that Putin sees as a virtual extension of Russia. He was also put off by the Bush and Obama administration’s support of regime change in the Middle East in Iraq, Egypt, and Libya. To Putin’s chagrin, the U.S. went around the U.N. Security Council to avoid a Russian veto of the Iraqi invasion in 2003.

Putin wanted to define the “war against terror” as including Color Revolution rebels against his authoritarianism in countries adjacent to Russia, like Ukraine, where he tried to maintain puppet regimes. But the U.S., regardless of whether or not they were aiding these anti-Russian rebels, was unwilling to group them in with ISIS or al-Qaeda. From America’s perspective, people that want a pro-Western government in Ukraine, for instance, aren’t “terrorists.” Also, NATO put medium-range missiles in Eastern Europe ostensibly to protect Europe from potential terrorist attacks from the Middle East, but Putin interpreted them as really intended for him. In front of an audience that included American politicians like John McCain and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Putin denounced America’s unilateral power and democratic agenda in a 2007 speech in Munich (right), also declaring his opposition to further NATO expansion. According to some reports, during the Arab Spring of 2011-12 (a series of uprisings against authoritarian rule), Putin was obsessed with footage of rebels brutally killing Libyan dictator (and real terrorist) Muammar Gaddafi, that Hillary Clinton had supported as Obama’s Secretary of State and was caught on camera in a salon chair callously laughing about, saying “We came. We saw. He died.” Obama’s administration also supported the overthrow of Egypt’s dictatorship, leading Putin to counter by backing Syria’s brutal suppression of democracy there. Putin even wrongfully feared that a potential Clinton administration would try to do the same to him. While that was no doubt paranoid, even delusional, it didn’t help matters when Oliver Stone told Putin in the 2016 interview that he had firsthand knowledge that such a coup was in the offing (Episode 1; Min. 0:50, 2.16). At the very least, Putin thought Secretary of State Clinton was behind the 2011-2012 protests against him in Moscow (featuring footage of election fraud on his behalf on social media), after which he had several unsupportive journalists killed. Putin’s work in counter-intelligence inclined him toward conspiracy theories and paranoia.

Putin wanted to define the “war against terror” as including Color Revolution rebels against his authoritarianism in countries adjacent to Russia, like Ukraine, where he tried to maintain puppet regimes. But the U.S., regardless of whether or not they were aiding these anti-Russian rebels, was unwilling to group them in with ISIS or al-Qaeda. From America’s perspective, people that want a pro-Western government in Ukraine, for instance, aren’t “terrorists.” Also, NATO put medium-range missiles in Eastern Europe ostensibly to protect Europe from potential terrorist attacks from the Middle East, but Putin interpreted them as really intended for him. In front of an audience that included American politicians like John McCain and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Putin denounced America’s unilateral power and democratic agenda in a 2007 speech in Munich (right), also declaring his opposition to further NATO expansion. According to some reports, during the Arab Spring of 2011-12 (a series of uprisings against authoritarian rule), Putin was obsessed with footage of rebels brutally killing Libyan dictator (and real terrorist) Muammar Gaddafi, that Hillary Clinton had supported as Obama’s Secretary of State and was caught on camera in a salon chair callously laughing about, saying “We came. We saw. He died.” Obama’s administration also supported the overthrow of Egypt’s dictatorship, leading Putin to counter by backing Syria’s brutal suppression of democracy there. Putin even wrongfully feared that a potential Clinton administration would try to do the same to him. While that was no doubt paranoid, even delusional, it didn’t help matters when Oliver Stone told Putin in the 2016 interview that he had firsthand knowledge that such a coup was in the offing (Episode 1; Min. 0:50, 2.16). At the very least, Putin thought Secretary of State Clinton was behind the 2011-2012 protests against him in Moscow (featuring footage of election fraud on his behalf on social media), after which he had several unsupportive journalists killed. Putin’s work in counter-intelligence inclined him toward conspiracy theories and paranoia.

Putin thus favored Donald Trump over Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in the 2016 election, interfering directly via WikiLeaks and social media with Trump’s encouragement on the bet that Trump was willing to lessen sanctions, withdraw American support for NATO, or at least withdraw support for the new pro-Western Ukrainian government. Putin hoped that Trump would weaken the western alliance and destabilize American politics because of his volatility. Trump also shared Putin’s dislike of American military interventions in the Middle East. This was the first time an American candidate openly encouraged a foreign adversary to commit espionage against a domestic opponent (7.28.16), in this case, finding (and hopefully dumping) Hillary Clinton’s emails, though Trump later said he was joking. But Russia started searching for her emails that very day. A June 2016 Trump Tower Meeting pointed to a quid pro quo of sanction relief for dirt on Hillary Clinton. Complicating things further — and this is why all previous presidents had turned over tax returns and divested from any personal business that might conflict with, or compromise, foreign policy — Trump was trying to build a hotel in Moscow during the 2016 election. Donald Trump, Jr. told a business conference in 2008 that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets,” and Trump sold a Palm Beach, Florida home to Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev for $95 million that he’d been unable to sell for a cheaper price.

Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort delivered polling data to Russian intelligence officer Konstantin Kilimnik. As chronicled in the Mueller Report (p. 130) Manafort seemed inclined to auction off American support for eastern Ukraine in exchange for political favors that would help Trump defeat Hillary Clinton, though the report didn’t implicate Trump in that plan directly. But Congress later increased American military aid to the region (javelin missiles) and then-president Trump signed off on it, which his predecessor, Obama, hadn’t out of fear that it would provoke Russia.

President Barack Obama didn’t want to look like he was favoring fellow Democrat Hillary Clinton during the 2016 election, so he suggested a joint statement with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (KY-R) condemning Russian interference, but McConnell (left) refused, saying that he didn’t believe the FBI and CIA. Coincidentally, Russia then built an aluminum factory in his home state of Kentucky as “Moscow Mitch” blocked funds for improved election security in the states. Moreover, Russians bought off the British Conservative Party, including prime ministers David Cameron and Boris Johnson. Cameron merely argued for improved Russian relations in exchange for campaign funds, whereas Johnson blocked investigations into Russian interference in British elections, just as Trump tried to do in the U.S. during his presidency. This was new territory for the U.S., as partisanship had degenerated to the point that one party was siding with an enemy against the other party and against America’s own intelligence agencies. The Founders, including George Washington in his 1796 Farewell Address, had warned against that very thing, but it didn’t happen much between the 1790s and 2016 (Bunk History).

President Barack Obama didn’t want to look like he was favoring fellow Democrat Hillary Clinton during the 2016 election, so he suggested a joint statement with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (KY-R) condemning Russian interference, but McConnell (left) refused, saying that he didn’t believe the FBI and CIA. Coincidentally, Russia then built an aluminum factory in his home state of Kentucky as “Moscow Mitch” blocked funds for improved election security in the states. Moreover, Russians bought off the British Conservative Party, including prime ministers David Cameron and Boris Johnson. Cameron merely argued for improved Russian relations in exchange for campaign funds, whereas Johnson blocked investigations into Russian interference in British elections, just as Trump tried to do in the U.S. during his presidency. This was new territory for the U.S., as partisanship had degenerated to the point that one party was siding with an enemy against the other party and against America’s own intelligence agencies. The Founders, including George Washington in his 1796 Farewell Address, had warned against that very thing, but it didn’t happen much between the 1790s and 2016 (Bunk History).

Manafort, who orchestrated Trump’s 2016 GOP convention and its surprisingly pro-Russia platform, had worked as an attorney for Viktor Yanukovych, leader of the puppet pro-Russian Ukrainian government prior to its overthrow in 2014 by Petro Poroshenko, whom Barack Obama supported because of his pro-Western leanings. In their 2010 election, six years before Trump supporters did likewise with Hillary Clinton, Yanukovych supporters chanted “Lock Her Up” toward their rival, Yulia Tymoshenko (right), whom they imprisoned until 2017 on spurious charges after defeating her.

Manafort, who orchestrated Trump’s 2016 GOP convention and its surprisingly pro-Russia platform, had worked as an attorney for Viktor Yanukovych, leader of the puppet pro-Russian Ukrainian government prior to its overthrow in 2014 by Petro Poroshenko, whom Barack Obama supported because of his pro-Western leanings. In their 2010 election, six years before Trump supporters did likewise with Hillary Clinton, Yanukovych supporters chanted “Lock Her Up” toward their rival, Yulia Tymoshenko (right), whom they imprisoned until 2017 on spurious charges after defeating her.

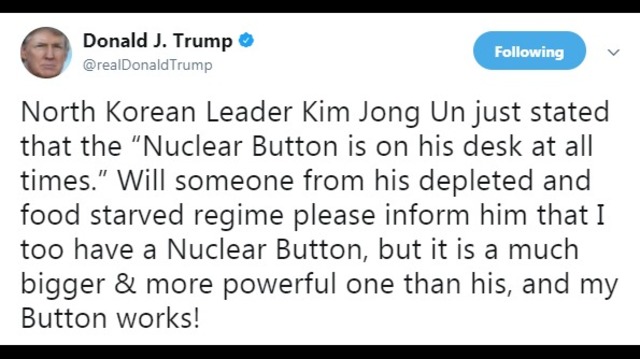

As the GOP debated its platform at their summer 2016 convention, Trump argued that Europeans should be responsible for any aid to Ukraine, that America’s best interests lay in improving Russian relations, and that the region wasn’t worth starting WWIII over (MR 133/488). Aside from his promise to lessen sanctions and potential to disrupt American democracy, Putin favored Trump because of his skepticism toward NATO. Shortly before taking office in January 2017, Trump called NATO “obsolete,” though he softened his stance and declared conditional support after he took office as long as other members started contributing a higher share to defense spending. In April 2017, Trump said NATO is “no longer obsolete,” but when he spoke at NATO headquarters in Brussels the next month, he avoided underscoring the an-attack-on-one-is-an-attack-on-all commitment of Article 5, instead berating the other leaders for not contributing their fair share. While there’s no evidence that Putin encouraged Trump to delete the “27 words” that reaffirmed American military commitment, the speech dovetailed well with Putin’s goal of sowing discord within NATO. Member countries have agreed to move toward a goal of each spending 2% of GDP on defense, but only the U.S. (3.6%) and four of the other 28 countries currently do: Great Britain, Greece, Estonia, and Poland. There is no group fund, though, as Trump often implies. The following month, pressured by his advisers, Trump reiterated American commitment to Article 5. In December 2017, Congress passed the aforementioned legislation sending javelin weapons to eastern Ukrainians fighting against Russians and Trump signed off on it under GOP congressional pressure, also perhaps trying to distance himself from Russia amid the Mueller investigation. However, in 2018, Trump told journalist Tucker Carlson that NATO was for the Europeans’ benefit, not America’s. White House Chief of Staff John Kelley said that, when Defense Secretary Jim Mattis talked Trump out of withdrawing from NATO, Trump purportedly called the staff who gave him a crash course in the western alliance “dumb” and “babies.” John Bolton called it likely that Trump would’ve followed through on disbanding NATO had he won re-election in 2020 and that “Putin was waiting for that.” On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump said he’d even encourage Russia to invade any delinquent country that hadn’t paid its fair share (e.g. Lithuania, who actually led European countries, proportionally, in aid to Ukraine) and was willing to “let Russia do whatever the hell they want” to any country that didn’t pay enough. Around the same time, Vladimir Putin told Tucker Carlson that Poland instigated World War II because, since they weren’t willing to give up territory to Germany, German was left with no choice but to conquer them.

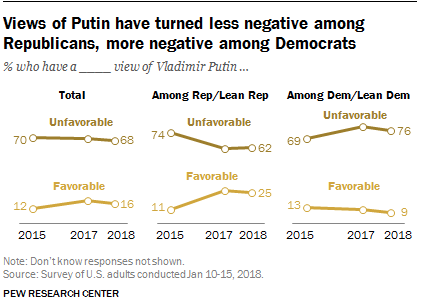

In the meantime, Putin’s popularity crept up among conservatives in America (right). Setting aside the fact that Ukraine is striving to become a pro-Western democracy while Russia is a de facto dictatorship, Richard Nixon’s speechwriter and longtime commentator Pat Buchanan called Putin the voice of “conservatives, traditionalists, and nationalists of all continents and countries” who were standing up against “the cultural and ideological imperialism of . . . a decadent West.” In short, by 2016 the U.S. didn’t really know who they supported in the rivalry between Ukraine and Russia. Democrats, establishment Republicans, hawkish Republicans (e.g., John Bolton), the State Department, FBI, CIA, and both parties in Congress favored Ukraine, whose pro-Western government wanted to join NATO and the EU, but Trump and his followers seemed to lean toward authoritarian Russia. Trump “joked” that he’d like to deal with critical journalists the way Putin did (kill them). Republicans in Congress were caught in between, favoring Ukraine and sending javelin missiles — after having criticized Obama for not doing enough on its behalf — while catering to Trump voters. Putin got a boost in 2020 when KCXL Kansas City starting broadcasting six hours of translated Russian propaganda (Radio Sputnik) per day, defined as “the things that the liberal media wont [sic] tell you.”

In the meantime, Putin’s popularity crept up among conservatives in America (right). Setting aside the fact that Ukraine is striving to become a pro-Western democracy while Russia is a de facto dictatorship, Richard Nixon’s speechwriter and longtime commentator Pat Buchanan called Putin the voice of “conservatives, traditionalists, and nationalists of all continents and countries” who were standing up against “the cultural and ideological imperialism of . . . a decadent West.” In short, by 2016 the U.S. didn’t really know who they supported in the rivalry between Ukraine and Russia. Democrats, establishment Republicans, hawkish Republicans (e.g., John Bolton), the State Department, FBI, CIA, and both parties in Congress favored Ukraine, whose pro-Western government wanted to join NATO and the EU, but Trump and his followers seemed to lean toward authoritarian Russia. Trump “joked” that he’d like to deal with critical journalists the way Putin did (kill them). Republicans in Congress were caught in between, favoring Ukraine and sending javelin missiles — after having criticized Obama for not doing enough on its behalf — while catering to Trump voters. Putin got a boost in 2020 when KCXL Kansas City starting broadcasting six hours of translated Russian propaganda (Radio Sputnik) per day, defined as “the things that the liberal media wont [sic] tell you.”

Trump didn’t allow his own aides in on the 2018 Helsinki Summit with Putin and even his translator had to burn her notes. When the CIA, FBI, NSA, and five European intelligence agencies accused Russia of meddling in the 2016 U.S. election, Trump sided with Russia and, at Helsinki, he publicly backed Putin’s denial, leading the normally humorless Putin to nearly burst out laughing in the lectern next to him and the White House staff to later claim that he misspoke. Meanwhile, at home, he obstructed and discouraged Robert Mueller’s investigation (MR Volume 2). Later, after the House chose not to take up impeachment charges because of the Mueller Report’s lack of “smoking gun,” and AG William Barr didn’t suggest they do so, Trump and House Republicans hoped to frame Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Ukraine instead as having interfered in the 2016 election, a theory that American intelligence labeled a hoax (Wiki). When the Ukrainian government wouldn’t go along with that conspiracy theory (why would they’ve conspired against Clinton when they favored democracy and wanted her to win?) or agree to dig up dirt on Hunter Biden (who’d worked for a Ukrainian energy firm and whose father, Joe, Trump anticipated running against, and who really was corrupt), Trump withheld military aid for their fight against Russia, pleasing Putin while undercutting Zelenskyy, and leading to Trump’s first impeachment hearings in the House in 2019. When a whistleblower leaked the extortion plot, they released the funds and Trump instructed his staff that there was no quid pro quo, but numerous witnesses testified that there was prior to the leak. Though whistleblowers aren’t spies and these ones (e.g., Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman) followed protocol, Trump implied that they should be executed for treason: “You know what we used to do in the old days when we were smart? Right? With spies and treason, right?” In Russia, they still can.

In 2022, former U.S. president Donald Trump praised Putin’s savvy and genius in the run-up to Russia’s Ukrainian invasion, gloating that he’d gotten the best of Joe Biden and proudly reminding his audience that “I know him [Putin] very, very, very well.” Trump’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani gushed, “They [Russia] have a president, we don’t,” while Congressman Madison Cawthorn (R-FL) called Ukrainian President Zelenskyy a “thug” and accused Ukraine of promoting “woke ideology.” Tucker Carlson promoted Putin’s fake conspiracy theory about U.S.-funded biolabs in Ukraine so faithfully that they re-broadcast FOX on Russian state TV, while right-wing OAN supported Putin’s theory that the hospital bombing in Mariupol, Ukraine was a hoax. At a critical point in the war, in May 2022, Rand Paul (R-KY) stalled a $40 billion (mostly) bipartisan aid package to Ukraine on a seeming technicality. In 2023, Trump called for withdrawing military support for Ukraine unless Congress agreed to investigate Joe Biden’s corruption, in effect doubling-down on the ploy that led to his first impeachment (AP). Once re-elected in 2024, Trump installed Putin’s biggest American supporter, Tulsi Gabbard, as director of National Intelligence. Like Carlson, Gabbard is shown regularly on Russian state TV.

Cold War Coda

Let’s backtrack to 1989-91. No one who lived through the Cold War ever imagined it would end so quickly and peacefully, but its conclusion didn’t rid the world of danger. Would Russia have good relations with the U.S. and Europe? What about the soldiers and weapons, including nuclear warheads, located in all those former Soviet countries besides Russia? What about the experts who knew how to use them? We saw above the Ukraine was the third-biggest nuclear power when they broke away — bigger than, for instance, Britain, France, or China. Ukraine gave up their nukes but, elsewhere, engineers and weapons would be up for sale to the highest bidder. With the bipartisan Nunn-Lugar Act, the U.S. quickly moved to curb nuclear proliferation as best it could, hoping to keep nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons out of the hands of people who dislike America, aka rogue states. What, in general, would this “New World Order” be like?

America isn’t perfect but, if someone must fill the power vacuum, it’s far preferable to Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, or Soviet Russia — all recent contenders for the role of top dog. And if the billions spent on America’s military budget helped stave off WWIII, then it was money well spent, especially for its allies that got free protection under the nuclear umbrella. Others argue that all the madness of the Cold War was a colossal waste of money that, unnecessarily, nearly caused WWIII while wasting our resources. Most historians who criticize the overall agenda of the Cold War are left-wing, but not all. Conservative John Lukacs disagreed with New Left historians that the Cold War was America’s fault, but also argued that Eisenhower missed a chance to end it in 1953 when Joseph Stalin died.

These are all speculative theories that can’t be proven one way or another. This much we know: by 1990 the U.S. stood as the lone economic superpower and top military power and had to decide what it would do with that opportunity. Would it work to make the world a better place? Would it just look out for its own interests? Would it work together with its allies? Would America go it alone? These were challenging questions for the post-Cold War administrations of Bush 41, Clinton, Bush 43 and Obama — in some ways more complex than what Cold War presidents had to deal with. Their world was frightening and challenging, but simpler. For the post-Cold War presidents, the agreed-upon goals included curbing nuclear proliferation and continuing to protect American oil interests in the Middle East.

On the Senate Armed Services Committee, Sam Nunn (D-GA) and Richard Lugar (R-IN) pushed through the non-proliferation act and led efforts to buy uranium from Russia to use in American power plants. Between the end of the Cold War and 2013, the Megaton to Megawatts program shipped enriched uranium from Russian decommissioned nuclear weapons to American power plants. For twenty years, an astounding 10% of all electricity on the American grid was powered by uranium from former Soviet nukes.

Persian Gulf

Jimmy Carter had succinctly expressed America’s Middle East policy in a 1980 State of the Union address. “Let our position be clear: an attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” The dynamic changed some between the Carter Doctrine and George H.W. Bush’s presidency. During the Cold War, the heavy hands of the U.S. and Soviets had at least served to keep smaller wars from escalating. Now that dynamic was gone with the USSR’s collapse and countries like Iran and Iraq no longer felt as though they were on either the American or Soviet leash. Iran threatened shipping lanes out of tiny oil-rich Kuwait, resulting in the U.S. flying the American flag over Kuwait’s ships. That led, indirectly, to the USS Vincennes accidentally shooting down an Iranian airliner (Iran Air Flight 655) in 1988, killing 290 passengers.

Meanwhile, desperate to pay off debts run-up in their 1980-88 war against Iran, Iraq rolled into Kuwait in 1990 looking for oil and port access to the Persian Gulf, claiming American support. Either Saddam Hussein misread the signals or the U.S. changed its mind and withdrew the go-ahead shortly thereafter. That’s unclear and revolves around the diplomacy of ambassador April Glaspie, who Iraq claimed expressed American neutrality. It may have taken the U.S. and others a while to digest the economic ramifications of Iraq’s invasion. Iraq already controlled 10% of the world’s crude oil supply and a Kuwaiti takeover would’ve given Saddam unacceptable leverage in world markets. Whatever the initial U.S. reaction was, American allies weren’t happy with the Kuwait invasion, especially Saudi Arabia (just south of Kuwait), Western Europe, and Japan, who relied on Middle Eastern oil.

Brigade of 3rd Armored Division in Saudi Arabia Preparing for Iraq Invasion During the Gulf War, February 1991, U.S. Army

Neither was al-Qaeda, comprised mostly of Saudi Arabians who wanted to repel Saddam themselves, without U.S. help and without the U.S. using the occasion to beef up its Saudi bases. The argument over who would have the honors of removing Saddam from Kuwait caused the initial rift between the U.S. and its old ally from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Saudi Osama bin Laden, though no one in America took notice of it at the time.

Neither was al-Qaeda, comprised mostly of Saudi Arabians who wanted to repel Saddam themselves, without U.S. help and without the U.S. using the occasion to beef up its Saudi bases. The argument over who would have the honors of removing Saddam from Kuwait caused the initial rift between the U.S. and its old ally from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Saudi Osama bin Laden, though no one in America took notice of it at the time.

The U.S. has enjoyed a mutually beneficial and reasonably stable oil-for-protection relationship with Saudi Arabia since Standard Oil of California (later Chevron) discovered rich deposits in the Ghawar Field on the country’s eastern shore in the 1930s. FDR sealed the alliance with the House of Saud shortly before his death in 1945. Osama’s own family was a direct beneficiary of the relationship though they made their fortune in construction rather than oil. As we saw in Chapter 19, the U.S. has juggled Israeli support and Saudi relations in order to keep the oil flowing. Saudi rulers have gotten rich, but the country still has a sizable population of Muslim fundamentalists who resent the American ties and despise Israel. In Osama bin Laden’s case, that resentment even spilled over into one of the families in the ruling oligarchy.

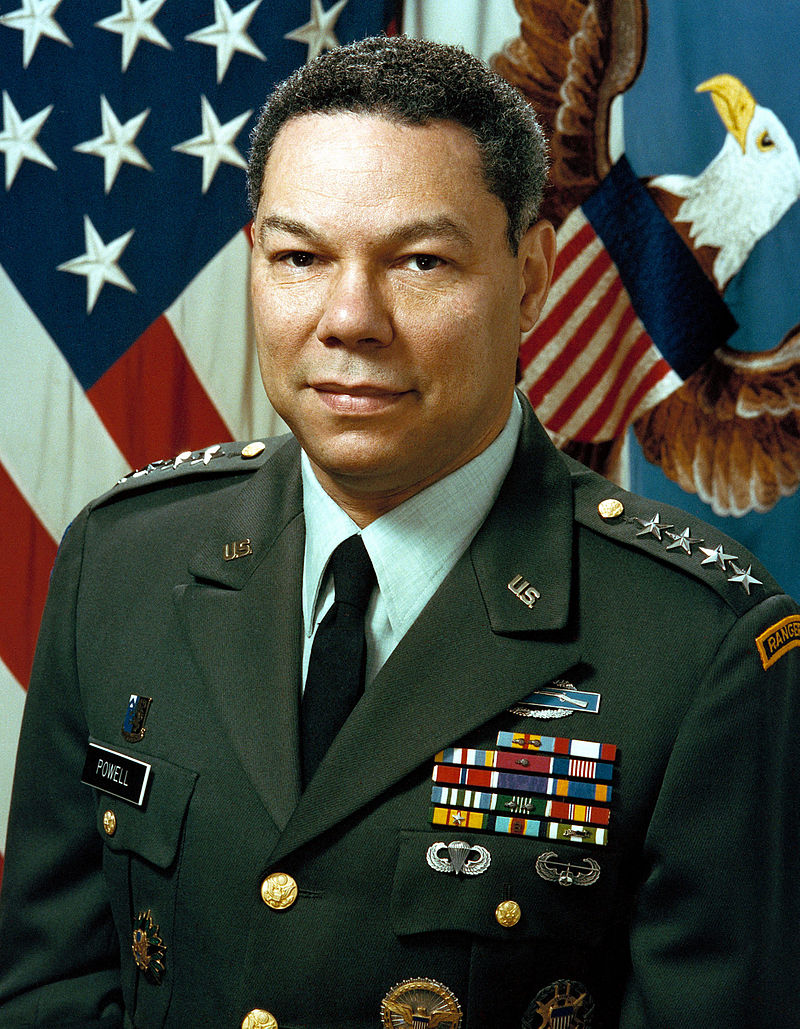

In 1990, Bush 41 employed his New World Order plan of strengthening collective security, hoping to beef up the United Nations (U.N.) now that the Cold War was over and have the U.S. lead the world multilaterally through its allies. He worked overtime on the phone, getting Coalition Forces arrayed against Iraq, though Israel was excluded at Saudi Arabia’s insistence. Still, Israel loomed large: Hussein signaled his willingness to withdraw peacefully from Kuwait if Coalition leaders agreed to a conference on the future of Palestine, but the U.S. was unwilling partly because of its alliance with Israel (see Chapter 19). Bush followed the recommendation of the Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Colin Powell, to use overwhelming aerial bombardment early and they destroyed Iraq’s Air Force as their first order of business. As a Vietnam veteran, Powell formulated his namesake Doctrine aimed at winning wars early and decisively with full public support, while always maintaining exit strategies.

Desert Storm Map

Desert Storm Map

In the 1990-91 Gulf War (aka First Persian Gulf War or Operation Desert Shield), the U.S. decimated targets with precision lasers, sometimes from control centers miles away, and ran the Iraqi ground troops out of Kuwait, mowing down those who didn’t surrender, which many of Saddam’s elite forces did. Iraqis fought back with Scud missile attacks against targets in Saudi Arabia and Israel but never broke out chemical weapons in retaliation. Coalition Forces’ use of Global Positioning Satellites (GPS) provided early warning against Scud missiles and helped in coordinating the “Left Hook” picture above. Many U.S. troops suffered a mystery illness that chemicals may have caused, though others suggest it was a natural airborne virus. Others argue that afflicted troops correspond with where the U.S. used depleted uranium weapons. Iraq had no nuclear weapons, partly because Israel preemptively bombed the Osirak plant near Baghdad in 1981. The facility may have been intended as a power plant, but was most likely for weapons.

Having kicked the Iraqis out of Kuwait during the Gulf War, the U.S. and U.N. had to decide whether or not to invade Iraq and overthrow Saddam. At first, Bush encouraged protesters against Saddam to rise up in Iraq, but then he changed his mind. Colin Powell and Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense, opposed the move, hoping Saddam could serve as a bulwark against Iran. When the U.S. changed its mind, Saddam slaughtered the Shias and Kurds who rose up against his Sunni Ba’ath Party. In his 1998 memoir A World Transformed, Bush 41 explained how overthrowing Saddam would have overstepped the United Nations mandate to simply protect Kuwait. It would have left the U.S. “occupying a hostile country with no viable exit strategy” and they might have had difficulty apprehending Saddam. In most ways, his concerns proved prophetic, the only exception being that U.S. forces were able to apprehend the fugitive dictator during the Iraq War of 2003-2011 when the U.S. decided to overthrow him (more below).

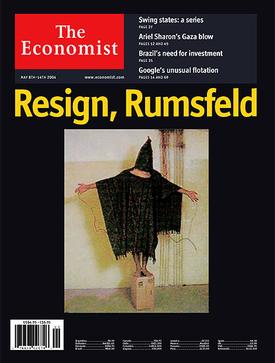

Having kicked the Iraqis out of Kuwait during the Gulf War, the U.S. and U.N. had to decide whether or not to invade Iraq and overthrow Saddam. At first, Bush encouraged protesters against Saddam to rise up in Iraq, but then he changed his mind. Colin Powell and Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense, opposed the move, hoping Saddam could serve as a bulwark against Iran. When the U.S. changed its mind, Saddam slaughtered the Shias and Kurds who rose up against his Sunni Ba’ath Party. In his 1998 memoir A World Transformed, Bush 41 explained how overthrowing Saddam would have overstepped the United Nations mandate to simply protect Kuwait. It would have left the U.S. “occupying a hostile country with no viable exit strategy” and they might have had difficulty apprehending Saddam. In most ways, his concerns proved prophetic, the only exception being that U.S. forces were able to apprehend the fugitive dictator during the Iraq War of 2003-2011 when the U.S. decided to overthrow him (more below).