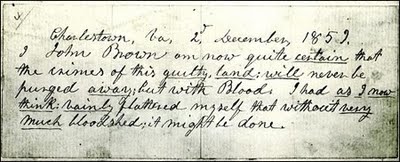

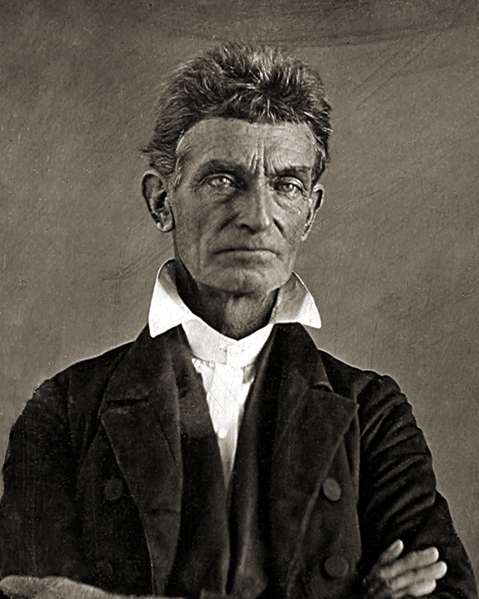

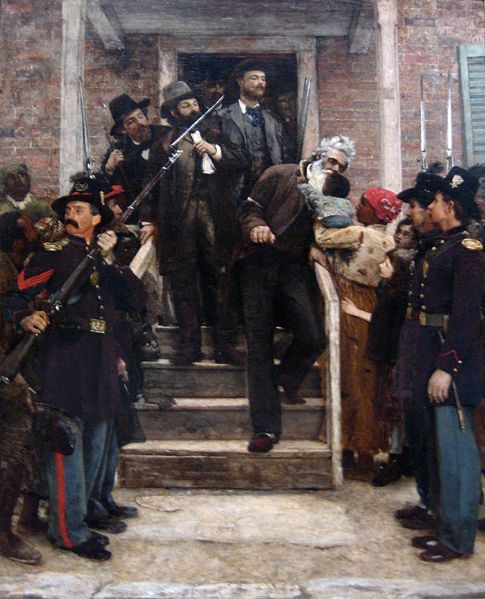

John Brown wrote these words just before he dropped from the gallows, sentenced to death by the U.S. government after a failed attempt to raid the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia to ship weapons to enslaved Southerners and incite an abolitionist insurrection. What is most surprising isn’t his famous prediction about the inevitability of an upcoming war between the states — many people anticipated that by 1859 — but rather his assertion that he’d hoped the sectional crisis could be resolved without bloodshed. After all, prior to Harpers Ferry, Brown and his sons were most famous for hacking apart a southern family at Pottawatomie Creek in the Kansas territory three years earlier. Inspired by the 1837 murder of abolitionist Elijah Parish Lovejoy in Illinois (Chapter 15), John Brown could be described as an early proponent of the “irrepressible conflict” school of thought historians later used to describe the idea that slavery presented a “logjam” in American history that could only be dislodged through force (war). Other historians countered that war wouldn’t have been necessary if not for a “blundering generation” of politicians on both sides overreacting and bringing it about unnecessarily. Either way, the earlier conflict in Kansas between pro-slavery Border Ruffians and free soil Jayhawkers had roots deep in American history, dating back to colonial times. In this chapter, we’ll examine why those tensions reached a boiling point in the 1850s that led to Civil War.

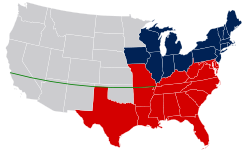

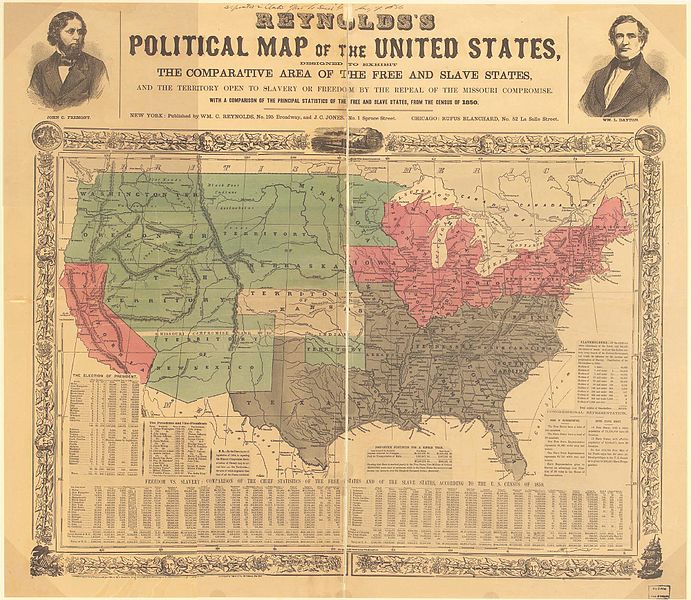

Western expansion and the Mexican War, in particular, disrupted the truce between North and South regarding slavery. The ensuing debate over slavery’s extension raged for fifteen years and was the primary cause of the Civil War. The Wilmot Proviso (bill), introduced in the Lower House in 1846 at the beginning of the Mexican War, signaled the fracturing of the Democrats. It called for banning slavery in the Mexican Cession but never passed the Senate. Its sponsor, Pennsylvanian David Wilmot, was a Democrat, the party that formed a strong north-south axis in American politics from the 1820s-1840s and had heretofore been united in their support of slavery. If the Wilmot bill was only a hairline fracture, the Democratic Party’s formal split into regional factions in 1860 signaled the onset of the Civil War, destroying the country’s last pillar of political stability.

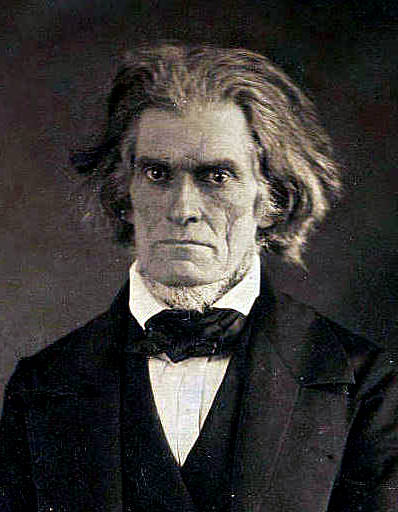

After Mexico, the leader of the Democrat’s Southern faction, South Carolinian John C. Calhoun, argued that any restriction on slavery in western territories compromised Whites’ Fifth Amendment right to life, liberty, and property, with enslaved workers serving as their property. Echoing Aristotle, he argued that democracy was impossible without slavery because slavery is what bound free people together. In 1850, Calhoun said, “With us, the two great divisions of society are not rich and poor, but black and white; and all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class, and are respected and treated as equals.” Along similar lines, he also thought that slavery was indispensable to capitalism because without it there was too much tension between wage workers and bosses.

Calhoun, you may remember from the end of the previous chapter, prophesied that the Mexican War constituted America’s “forbidden fruit.” Southern politicians pushed the war because, like tobacco, cotton exhausted soil quickly and planters thought that slavery had to expand to survive. Shortly after the Mexican War, radical southern leaders called Fire Eaters began agitating for secession and re-opening the Atlantic slave trade. In the North, the idea of free soil — that the West should be preserved for white farmers and wage-workers — worked its way into mainstream politics through a third party called the Free Soilers, then the new Republican Party. A series of compromises, clashes, misunderstandings, and controversies ensued that, collectively, explain why war broke out in 1861.

Compromise

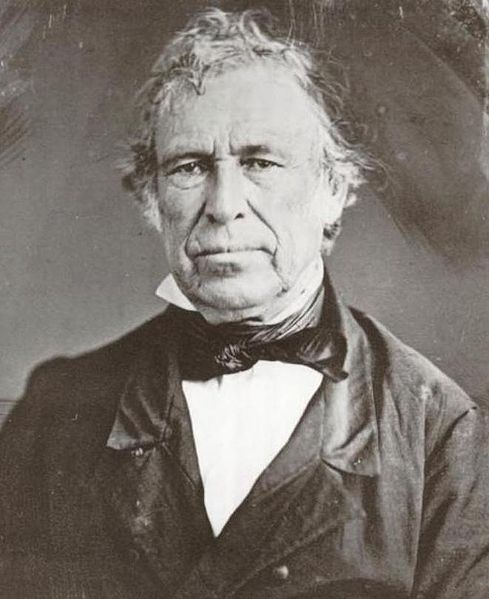

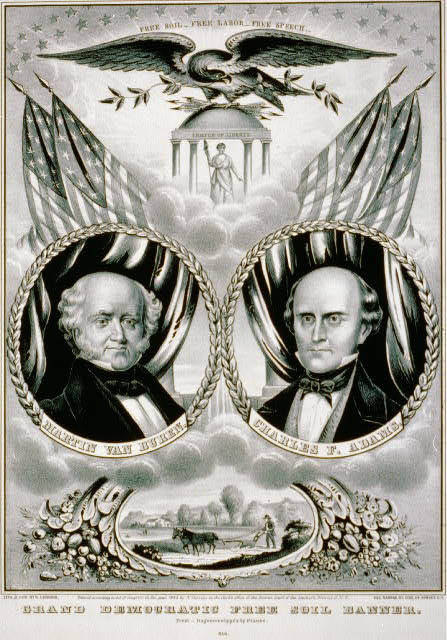

Through 2016, it was customary for new presidents-elect to escort the incumbent from the White House down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol steps for the inaugural ceremony (first in carriages, then limousines). The civility of the occasion underscored America’s proud tradition of peaceful power transitions. When Mexican War hero Zachary Taylor picked up his old boss James Polk in March of 1849, though, President Polk was in for a shock. Zach Taylor was a Louisiana slaveholder who presumably shared the Tennessean Polk’s pro-slavery views. Abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner condemned Taylor’s nomination as “an alliance between lords of the lash and lords of the loom (the southern plantations and northern textile mills who supported ‘Cotton Whigs’).” “Old Rough-n-Ready” had enjoyed such a commanding lead in the race that he chose to keep his foot out of his mouth, so to speak, and didn’t really campaign. It thus came as a surprise to many, not least Polk, to learn that Taylor had converted to the new Free Soil movement. The 1848 election had also included a Free Soil third party running former Democratic president Martin Van Buren. Founded in Buffalo, the Free Soil Party formed out of anti-slavery “Barnburner” Democrats and “Conscience Whigs” who broke away from fellow northern, pro-slavery “Hunker Democrats” and “Cotton Whigs.”

Zachary Taylor, though, hadn’t indicated anything one way or another, which was part of his appeal. Polk never guessed he’d become a Free-Soiler. Hadn’t they fought for slavery in Mexico, even as they denied it publicly? Now because of Taylor’s apostasy, Polk’s major accomplishment seemed to unravel right before his eyes, literally in the last minutes of his presidency.

Americans were divided either way, regardless of what Polk or Taylor thought. The nation almost went to war in the late 1840s as California raced toward free statehood during the Gold Rush. The incoming President Taylor and Senate majority leader Calhoun locked horns on slavery’s extension and Congress gridlocked until their deaths in 1850 — Taylor of food poisoning (milk or cherries) on the 4th of July and Calhoun of a heart attack after a fiery speech. The new president, Millard Fillmore, was more open to a settlement.

With the two uncompromising actors off the stage, Capitol Hill worked its magic and cobbled together a series of separate bills known collectively as the Omnibus Bill, or the Great Compromise of 1850. It was the latest (and last) in a long string of compromises over slavery dating back to the Declaration of Independence, Northwest Ordinance, and Constitution itself.

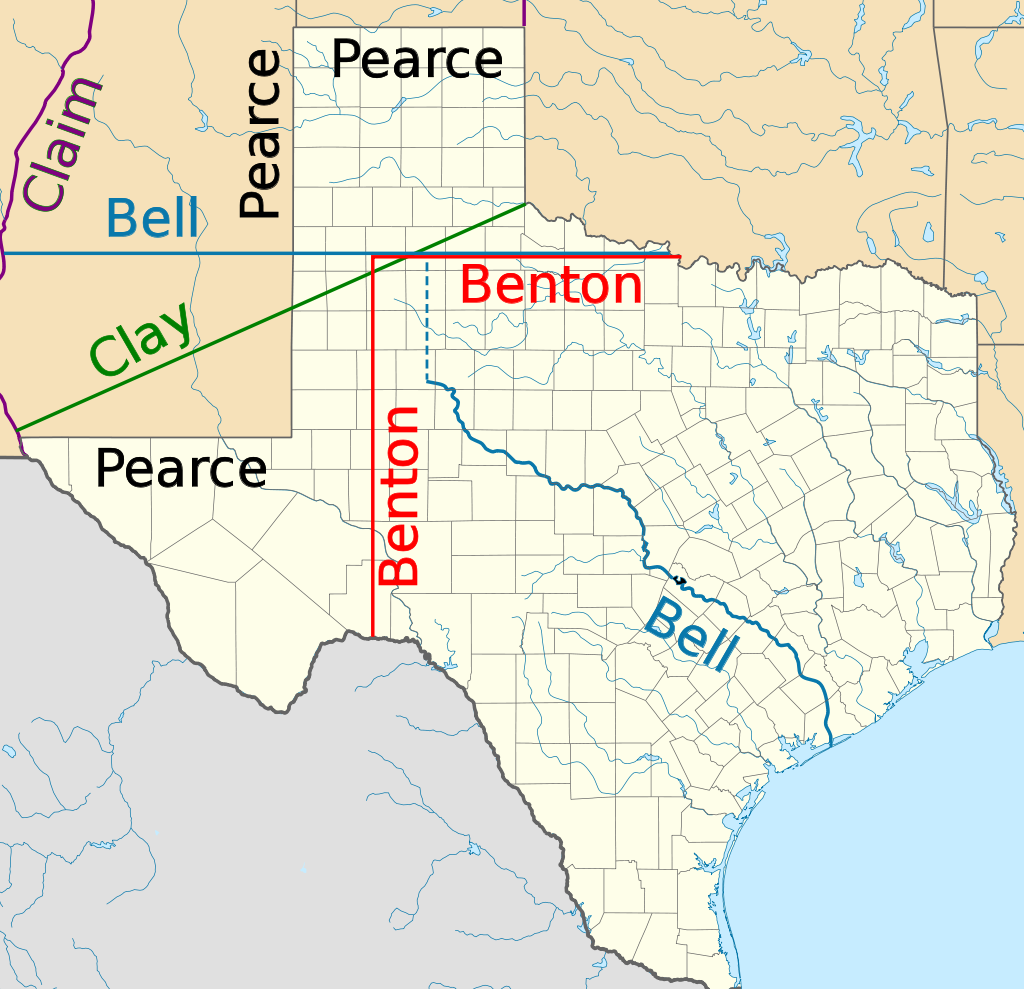

Sectional rumblings began amidst controversy over Missouri’s admission in 1819-20 because it was the first state west of the Mississippi River. Before that, the Mason-Dixon Line separating Maryland and Pennsylvania and the Ohio River served as the traditional borders between freedom and slavery. However, the Ohio River flowed into the Mississippi so the agreed-upon line ran out. With the Missouri Compromise, politicians came up with a new solution. They extended the southern border of Missouri, the 36°30′ Line, west to the Pacific Ocean, even though Missouri itself, north of the line, had slavery (right). That line could have sufficed in perpetuity but, in truth, both North and South wanted it all and, within a generation, neither showed much enthusiasm for 36°30′. The line just bought time before Americans started to move west in serious numbers, but didn’t quell foreboding. Thomas Jefferson wrote of Missouri “that this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed indeed for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence.” Earlier, in 1797, Jefferson prophesied that “if something is not done, and soon done” about slavery, “we shall be the murderers of our own children.”

The same senator who patched together the Missouri Compromise in 1820, Kentuckian Henry Clay, helped broker this latest in 1850 — thus his nickname, the Great Compromiser. California would come in as a free state and Texas would remain a slave state but shrink down to its current size, with New Mexico carved out of its western Rio Grande Valley. The New Mexico Territory (originally including Arizona) and Utah would be subject to free sovereignty, whereby the settlers who moved there would decide the slave issue on their own as they drew up their territorial and state constitutions. Lewis Cass of Michigan originally suggested this idea in the 1848 election. Free sovereignty, or popular sovereignty (or if you’ll pardon a third term, squatter sovereignty), became a sort of fallback compromise position helping to stave off war for a decade or so. Free-popular-squatter sovereignty had the advantage of being more democratic and, perhaps more to the point, the national government could shove a sticky issue off onto the people. It would be like settling our most contentious national debates of today in town hall meetings.

The 1850 Compromise dealt with other festering issues besides western expansion. Abolitionists and Europeans would now be spared the indignity of witnessing human auctions near the Capitol steps as the slave trade, but not the practice, was abolished in the District of Columbia. And the deal promised Southerners ramped up enforcement of the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act in the North, per their constitutional rights, and in California, where some illegal slavery persisted (Spanish settlers had enslaved Indigenous Americans there on missions earlier, Wiki). The Fugitive Slave Act legitimized bounty hunting and anyone could be deputized to capture escaped slaves. The country had stepped back from the brink of war and abolitionists were marginalized as having nearly caused the war.

The Compromise of 1850 is a good demonstration, though, of how different reality can appear as it’s unfolding into the future versus what historians see looking back with perspective. Fourth of July-like celebrations rang out across America as it seemed the promising young country had now solved its most vexing issue by compromising on western slavery. Civil War had seemed a real possibility, but that worst-case scenario was averted once and for all through legislative compromise. Alas, sleeping dogs did not lie and the settlement didn’t last. There were unforeseen flies in the ointment. If anything, the Compromise of 1850 bought time for the Union as they gained material resources, immigrants (potential workers, farmers, and soldiers), and moral arguments in the decade leading up to war. The stepped-up enforcement on runaway slaves seemed at the time to favor the South, but the new Fugitive Slave Act (1850) wound up awakening otherwise apathetic Northerners to bounty hunting, one of slavery’s seedier aspects. Free sovereignty only worked well in New Mexico-Arizona because there weren’t many settlers there. That gave politicians the false impression it could work well anywhere, including the new Kansas Territory.

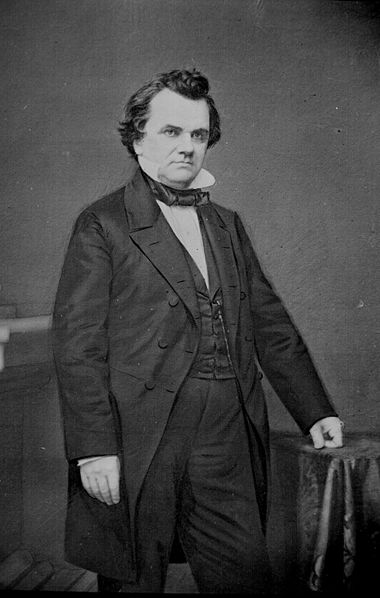

Bleeding Kansas

In retrospect, you could say the fiasco surrounding Kansas’ admission to the U.S. four years later was an opening salvo of the Civil War. Proportionally, the level of violence in Bleeding Kansas and neighboring western Missouri rivaled that of the upcoming war. The story starts with the ambitions of Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas, the “Little Giant,” whose main goal was to connect his home state to the mushrooming California population via a transcontinental railroad. Given how disruptive Native Americans could be toward railroad construction, Douglas thought the best prospect for getting tracks built across the Plains was to territorialize the region stretching from present-day Kansas north to present-day Montana, then known as Kansas & Nebraska. Instead of thinking through the slave debate implications of the acquisition, Douglas dreamed only about the sleepy village on the southwestern corner of Lake Michigan called Chicago and how it would soon grow into a bustling railroad hub. Remember the 36°30′ Line? At the behest of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (future president of the Confederacy), President Franklin Pierce repealed the old Missouri Compromise and Douglas supported repeal as a way to win Southern votes. Pierce argued that the Founders had believed “free white men” should rule over “the subject races…Indian and African.” Free sovereignty had worked in the New Mexico Territory, had it not? And it was undeniably democratic to have settlers hammer out their own issues; no one could argue with that. Consequently, they tacked free sovereignty onto the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 that territorialized the final piece of the Lower 48 U.S. jigsaw puzzle.

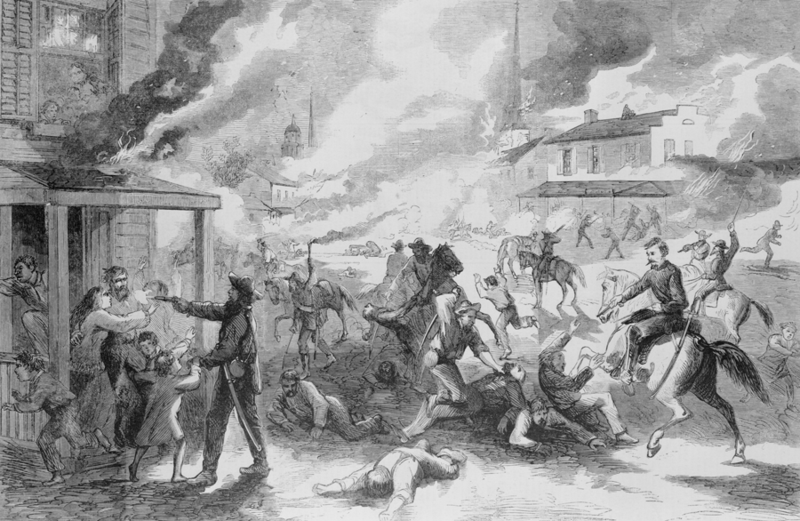

But Kansas was four years later than New Mexico and closer to eastern populations. Instead of settlers who might have incidentally differed assembling to have a constructive civic debate, partisans from both sides flooded in to fight out the slavery issue. Southern Border Ruffians (aka bushwhackers) mainly from nearby Missouri, burnt Free Soil Jayhawker towns like Lawrence and “Right-to-Riser” colonies. Jayhawkers were also known as “Red Legs” because of their signature pants, as depicted in Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Western The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966). Jayhawkers derived their name from Founding Father John Jay, an early abolitionist and Christian Nationalist. In the tellingly-named Squatter Sovereign, one bushwhacker op-ed writer proclaimed that slaveholders would not be deterred, “though our rivers should be covered with the blood of their victims and the carcasses of abolitionists should be so numerous in the territory as to breed sickness and death.” Missouri Senator David Atchinson encouraged bayonet-wielding Border Ruffians to stuff ballot boxes across the Kansas border, promising that “If we win, we can carry slavery to the Pacific Ocean.”

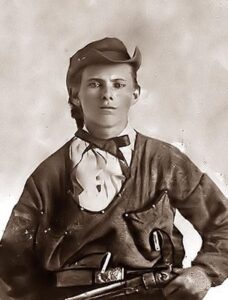

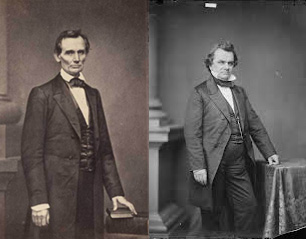

One passionate Jayhawker, the forenamed John Brown (upper right and top of the chapter), was motivated by an apocalyptic vision to end slavery by any means necessary and sought retribution for the Sacking of Lawrence. At Pottawatomie Creek in 1856, the maniacal Brown and his sons chopped up a pro-slavery family with their broadswords to avenge the burning of Lawrence. Retribution and counter-retribution followed. Bleeding Kansas is an instructive case study to show that shifting power from higher up — “distant elites” in the national government, if you will — to local authorities doesn’t magically solve problems just because it’s more democratic.

Instead of writing a state constitution together, each side met in their respective camps, Lawrence and Lecompton, and wrote up their own laws. More people voted for the slave camp’s version, the Lecompton Constitution, than even lived in the entire territory. It not only legalized slavery, it also made aiding and abetting enslaved escapees subject to capital punishment. In other words, if white Free Soilers were caught helping enslaved workers escape on the Underground Railroad, they’d be lynched.

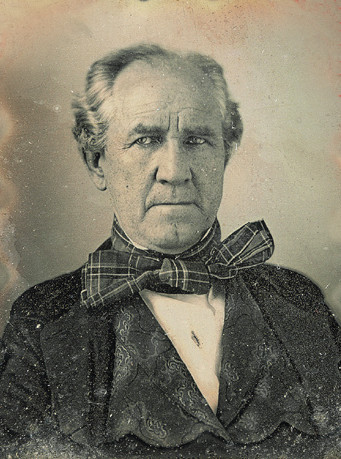

Having committed to the free sovereignty model, Washington politicians had to choose one or the other version of the constitution. Congress and President James Buchanan sided with the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution at first, but Kansas later became a free state in 1861. Violence continued there throughout the Civil War and afterward in Missouri. Bleeding Kansas led to a breakdown in the compromising spirit that had worked up through 1850, for better or for worse (worse from the enslaved perspective). Texas Senator Sam Houston cast the lone dissenting Southern vote against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, thinking that planters were getting too greedy in hoping to spread slavery to the Great Plains. Houston prophetically justified his opposition: “…what fields of blood, what scenes of horror, what mighty cities in smoke and ruins—it is brother murdering brother… I see my beloved South go down in the unequal contest, in a sea of blood and smoking ruin.”

Bleeding Kansas also represented a breakdown in law, as neither Brown nor any of the murderous arsonists among the Border Ruffians went to jail. Lawlessness and vigilantism characterized Kansas and Missouri throughout the Civil War era, spawning outlaws like Jesse James of Quantrill’s Raiders. In 1863, Abraham Lincoln wrote eloquently about what war does to society and men:

Blood grows hot, and blood is spilled. Thought is forced from old channels into confusion. Deception breeds and thrives. Confidence dies, and universal suspicion reigns. Each man feels an impulse to kill his neighbor, lest he be first killed by him. Revenge and retaliation follow. And all this…may be among honest men only. But this is not all. Every foul bird comes abroad, and every dirty reptile rises up. These add crime to confusion. — Lincoln to Missouri abolitionist Charles Drake, 1863

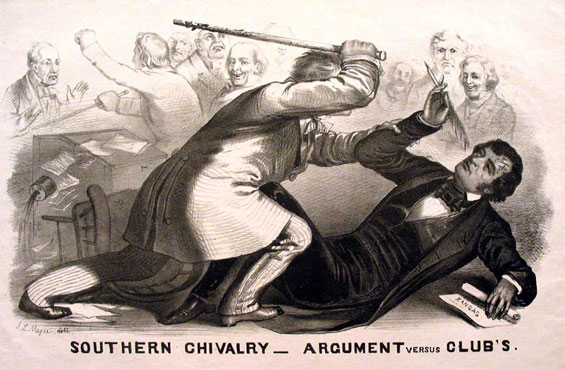

Five years before the Civil War, civility broke down in Washington politics, as well, illustrated by the “Caning of Charles Sumner” on the Senate floor after his anti-slavery speech “The Crime Against Kansas.” The erosion of civility in national politics, the most crucial institution, coincided with the rise of criminality among the people. During an uncomplimentary speech about the “drunken spew and vomit of civilization” spilling across the Missouri-Kansas border to promote slavery, the Massachusetts statesman rudely poked fun at a senior senator from Tennessee, Andrew Butler, calling his support of slavery “polluted” and pointing out how he drooled down his chin. He didn’t realize that Butler was the uncle of South Carolinian Preston “Bully” Brooks, who sauntered over to Sumner after the speech and proceeded to beat the daylights out of him with a gold-tipped cane. Massachusetts continued to vote Sumner into office while he convalesced so that his empty, bloodstained desk would serve as a reminder of southern barbarity. Massachusetts congressman Anson Burlingame goaded Brooks into challenging him to a duel that Brooks backed out of after Burlingame, a crack shot, accepted the offer. Meanwhile, in the South, souvenir canes inscribed with “Hit ‘em again Bully” sold like hotcakes.

Sumner’s caning was the tip of the iceberg. Historian Joanne Freeman chronicled 70 Incidents of congressional violence in the 30 years before the Civil War, mainly Southerners bullying Northerners physically until Northern voters caught on and started electing men specifically to fight. With statesmen wearing their holsters to work by the late 1850s, partisan Congress was obviously a long way from the compromising of 1820 and 1850. In 2023, Senator Markwayne Mullin (R-OK), a former MMA fighter, called for more violence in Congress, hoping it would increase the public’s respect for politicians. “You used to be able to cane,” he said, after challenging a Teamsters Union rep to a fight during a hearing. But, in the 1850s, the capitol circus helped plunge the country into civil war. News of Sumner’s caning is what sent John Brown off the rails, occurring just after the Sacking of Lawrence and days before his Pottawatomie Creek Massacre.

Birth of the GOP

Bleeding Kansas reshaped the political landscape, leading to the current two-party alignment. It gave rise to the Republicans, aka GOP for “Grand Old Party.” America’s party history is complicated because Thomas Jefferson’s old faction, that later became the Democrats, was first known as the Republicans in the 1790s. But the party of Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan and both George Bushes emerged out of Bleeding Kansas – opposing Lecompton and, more generally, the western expansion of slavery. They were not a single-issue party. They added the pro-business, strong national government brew of the Whigs and their forebears, the Federalists. The GOP didn’t start favoring a weaker central government than the Democrats until the 1920s-’30s. Newspaperman Horace Greeley — most famous for his phrase “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country” — underscored the new Republicans ties to the Federalist and Whigs’ American System, noting that “An anti-slavery man, per se, cannot be elected, but a tariff, river-and-harbor, Pacific Railroad, free homestead man may succeed though he is anti-slavery.”

In the 1850s, the Republicans’ Free Soil stance dovetailed with northern evangelicals and abolitionists naturally fell into the party’s ranks. While the Republicans weren’t as blatantly anti-immigration as the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, also known as the American Party or Know-Nothings, they looked out for the interests of WASPs, or White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. They were at least similar enough to the Know-Nothings to soak up that narrower party. The Whigs could not agree on slavery, so they split regionally, and they and the Know-Nothings gradually gave way to a regional showdown between the purely northern Republicans and mostly southern Democrats. Some northern “anti-Nebraska” Democrats defected to Republican ranks while others continued to support slavery. The Free Soil Party evaporated and melted into the Republicans along with the northern Whigs, abolitionists, and Know-Nothings, having served its purpose by seeding the Republicans. Its original organizer, Salmon Chase, led the Free Soilers’ transition into the new Republican Party. The regionalization of political parties didn’t bode well for the country’s near-term future.

It’s confusing, but the upshot is that a new two-party system, Republicans and Democrats, emerged in the 1850s that is still with us today. No one knows for sure where exactly the Republican Party originated — Ripon, Wisconsin and Jackson, Michigan are two claimants — or when exactly they emerged as the most powerful northern party, but they ran a presidential candidate in 1856, trailblazer John Frémont. Then, in 1860, they landed Abraham Lincoln in the White House.

Seismic shifts in politics such as the rise of the Republicans and demise of Whigs and Know-Nothings don’t happen overnight and indicate deeper cultural and economic cleavages. The North and South had always been co-dependent and grew more so in the 19th century as steamboats plied the river highways between the regions and trade picked up. Whites shared European ancestry, a common religion and language, and a short but proud national history. Northern mills manufactured much of the South’s slave-grown cotton into clothing and fabric. New York, especially, was home to many of the textile mills and was generally pro-slavery. It was second-last of the northern states to abolish it in 1827, followed by neighboring New Jersey. But by the 1850s, New York’s economic orientation was swiveling west toward the booming northern economy of family farming, industry, and railroads already connected to its deep-water port via the Erie Canal. Its financial markets supported corporations popping up mainly in the urban North and Midwest. It’s no coincidence that Abraham Lincoln was, by trade, a western railroad lawyer. Those connections helped him curry favor among East Coast politicians who quickly came to dominate the Republicans.

Sectional Divide

Northerners were proud of how dynamic their economy was, with opportunities aplenty for white men who kept their noses to the grindstone. It was possible to rise up through the system by virtue of talent, ambition, sobriety, hard work, or ruthlessness. It wasn’t common of course — everyone can’t be rich, after all — but, among Americans who did strike it rich, it was common to have started from scratch and that really was unusual in world history. The Market Revolution (Chapter 14) saw the emergence of the American Dream, later captured in the formulaic rags-to-riches plots of youth novelist Horatio Alger. Keep this in mind in the next chapter when we ask ourselves why Union soldiers thought America was worth fighting for. They weren’t fighting to free Blacks and it would’ve been much easier to just let the South go. The North wasn’t fair in the modern sense of the word since the vast majority was shut out (all women, Blacks, Indians, white men from the wrong parts of Europe), but it provided more opportunity than Europe or the South, where wealthy landowners handed down their inheritance to their sons.

Northerners pitied poor, white Southerners, some of whom either owned a few people themselves or found work guarding slaves on plantations. The stable South was more economically stratified and proud of it. They had history and tradition on their side and, like the Greek philosopher Aristotle, they recognized slavery as the foundation of democracy because it bound the free citizens together. Rich southerners lived with class on their beautiful plantations the way only “old money” can and chortled that northern businessmen seemed like crass, aggressive money-grubbers. Like the protagonists of Downtown Abbey, they were hanging on to a privileged lifestyle that they feared was slipping away, except that their un-earned wealth depended on human trafficking rather than the mere exploitation of working classes. But with that wealth wrapped up in land and enslaved workers and planters unwilling to fund public education, poor Whites had no real prospects of moving up the ladder. Why would the rich fork over their own money to encourage upward mobility? The poor coaxed what living they could out of the soil, raised some livestock and made extra money on the side serving in militias that policed the enslaved population. They weren’t rich, but at least they were white. Some held out hope of becoming big slaveholders themselves, similar to the way working classes today hope to win the lottery. One foreign newspaper correspondent saw the potential problems between regular Southerners and planters threatened by geography:

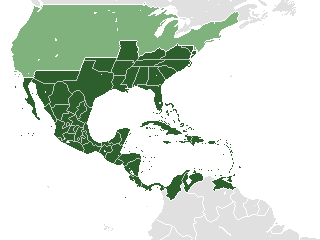

Only by the acquisition and prospect of acquisition of new territories, as well as filibustering expeditions (i.e. Central America) is it possible to square the interests of these “poor whites” with those of slaveholders, to give their restless thirst for action a harmless direction and to tame them with the prospect of one day becoming slaveholders themselves. A strict confinement of slavery within its old terrain, therefore, was bound according to economic law to lead to its gradual extinction, in the political sphere to annihilate the hegemony that the slave states exercised through the Senate, and finally to expose the slaveholding oligarchy within its own states to the peril from the “poor whites.”

If the picture doesn’t suffice, talk of hegemony and oligarchy is a clue to this journalist’s identity: Karl Marx. Despite living in London at the time, the communist revolutionary survived on $10/week from Horace Greeley’s New-York Daily Tribune as a correspondent and took an interest in the “great republic.” Marx understood the country’s regional connection, writing that “without slavery there would be no cotton, and without cotton there would be no modern industry.” He was rooting for the (northern) bourgeoisie capitalists to win out over the (southern) landed aristocracy as a necessary historical step on the way to wage workers toppling the capitalists. Whatever you may think of the feasibility or desirability of that pipe dream, you could do worse than Marx’s analysis of the Civil War’s root cause. For instance, you could read Jefferson Davis’ Rise & Fall of the Confederate Government (1881), the delusional prattle the former Confederate president wrote after the war to explain away the relevance of slavery (we’ll flog that horse in more detail in Chapter 22). What Marx was saying here, conversely, aligns with what southern expansionists wrote before the war. They didn’t just need expansion to appease regular Whites, but also to maintain their own standard of living in an age of soil exhaustion, before fertilizers and crop rotation. The ideal of bequeathing wealth to one’s heirs was easier said than done. Marx and his sidekick Frederich Engels corresponded throughout the coming war, with Engels focused mainly on military strategy and Marx on its political and economic ramifications (Engels predicted Confederate victory).

The North and South were growing apart religiously, as well, mostly for these same reasons. It says a lot about the importance of faith in American life that the sectional breakup of the Whigs, Know-Nothings, and Democrats came after two of the main Protestant denominations split in the mid-1840s. Methodists (1844) and Baptists (1845) split into northern and southern factions prior to the political parties and Presbyterians followed suit in 1861. It became impossible to work in southern ministries unless one could not only overlook slavery’s downside but also promote it as Christian and a positive good. Most churches don’t hire ministers to teach them something new; they hire them to teach what the congregation wants to hear. There’s no Scriptural evidence that Jesus opposed slavery and the Bible sanctions slavery in several passages (e.g. Leviticus 25:44, Colossians 3:22, Ephesians 6:5, Peter 2:18). A popular, if badly misconstrued, take on the Curse of Ham in Genesis (9:20-27) seemed to explain God’s take on race and slavery for those predisposed to racism. Scouring northern history for dirt, they fastened onto the Salem Witch Trials of 1692-93, accusing contemporary, intolerant “witch-burning Puritans” [abolitionists] of threatening plantation owners (Salem witches were lynched and pressed, not burned).

Northern churches, in turn, taught that the Second Coming of Christ required mankind ending his most egregious sins, including slavery. This is where bolstering the Fugitive Slave Clause as part of the 1850 Compromise came into play. That rule made otherwise non-committal northern Christians complicit in slavery and they resisted. This was especially true of the Quakers and evangelicals that, as we saw in Chapters 14-15, spearheaded the white abolition movement. While not racially progressive by modern standards, neither were many Northerners enthusiastic about helping bounty hunters track down humans like animals. In that way, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 backfired on Southerners, popularizing northern abolition.

Northern churches, in turn, taught that the Second Coming of Christ required mankind ending his most egregious sins, including slavery. This is where bolstering the Fugitive Slave Clause as part of the 1850 Compromise came into play. That rule made otherwise non-committal northern Christians complicit in slavery and they resisted. This was especially true of the Quakers and evangelicals that, as we saw in Chapters 14-15, spearheaded the white abolition movement. While not racially progressive by modern standards, neither were many Northerners enthusiastic about helping bounty hunters track down humans like animals. In that way, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 backfired on Southerners, popularizing northern abolition.

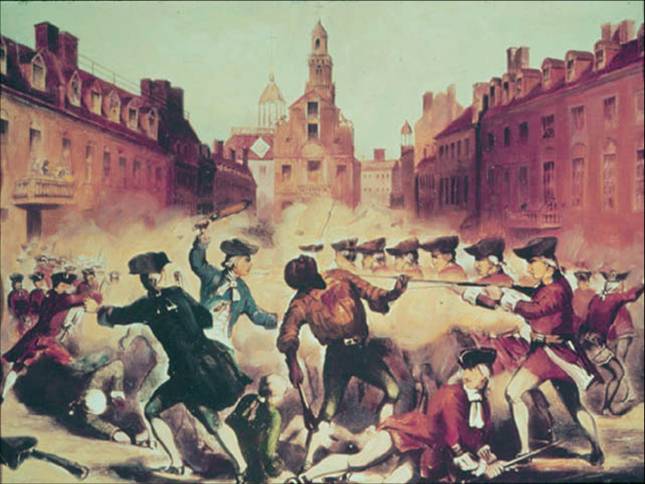

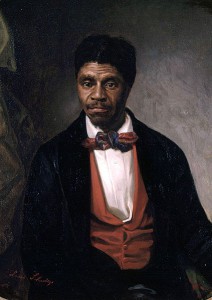

Northerners liked slavery even less after publication of the century’s second best-selling novel in 1852, Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (best-selling was Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ). Fittingly enough, Stowe’s father was a well-known evangelical minister, Lyman Beecher. The book tapped into Northerners’ dislike of the Fugitive Slave Clause and helped abolitionism gain more mainstream traction. Uncle Tom’s Cabin showed how slavery undermined white character and morality while depicting the anti-Christian way that slavery tore apart black families. Stowe wasn’t alone in her observation that slavery messed up Whites; Thomas Jefferson complained that planters’ sons were difficult to educate because they were so conditioned to defy authority and abuse people under them instead of accepting instruction. Midway through the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln purportedly welcomed Stowe to a gathering at the White House by saying, “so you’re the little woman who wrote this great book that started this big war.” It was an exaggeration since no one person started the war, and she didn’t mention the incident in a letter she wrote her husband that night, but the anecdote underscores her influence. Stowe reinforced the connection between Christianity and abolitionism among a broad audience, including Europeans. British called abolitionism “Uncle Tomism.” Meanwhile, anti-slavery advocates distributed photos like this one of a Baton Rouge slave named Gordon during the Civil War. Native and African-American stevedore Crispus Attucks went from being absent in 18th-century paintings of the Boston Massacre to being featured front-and-center as the first man to die in the American Revolution, which he was:

Dred Scott Case

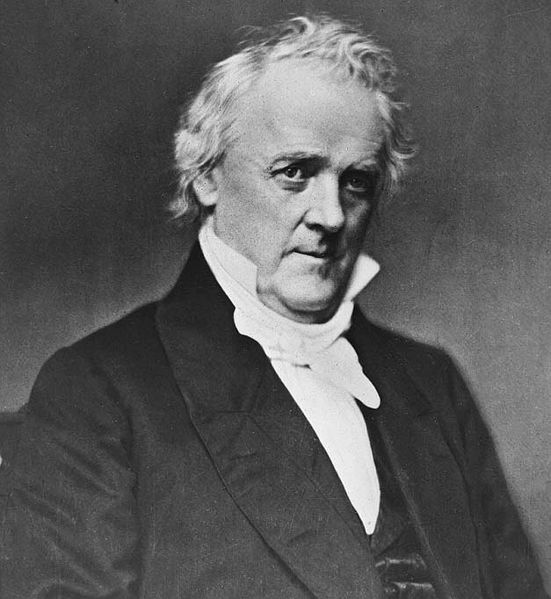

With Stowe’s book and stage play making waves in the North, Kansas-Missouri in turmoil, and a new political party dedicated to stopping slavery’s expansion, President-elect James Buchanan was desperate to stave off war and diffuse the sectional standoff. Buchanan was a pro-slavery northern Democrat. As we saw in Chapter 16, he tried to unite the sections in a common war out west against Mormons, but that fizzled out. First, though, as president-elect he encouraged the Supreme Court, dominated by southern Democrats after years of pro-slavery presidents, to resolve the controversy over western slavery once and for all.

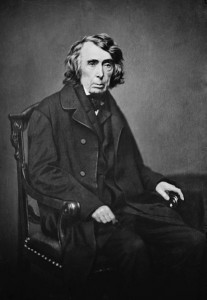

In the months between Buchanan’s election and when he took office, Chief Justice Roger Taney presided over the case of Dred Scott, originally from Missouri, who sued for freedom because he lived with his army doctor owner in the free territories of Illinois and Minnesota (then part of Wisconsin). There was a gentleman’s agreement that southern planters could spend summers cooling off at Cape Cod or Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts with some enslaved workers, as long as their vacations didn’t last more than a few months. Scott, though, had spent over a decade held in free territories. Taney (below, right) knew Buchanan wanted clarity and he delivered. He ruled that Scott could not even use the court system and that those of African descent, free or enslaved, had “no legal rights whatsoever” that Whites were bound to respect. He concurred with John C. Calhoun’s view of the Fifth Amendment that Whites had the right to black property and argued that no western territory had any right to restrict slavery in any way.

The Dred Scott interpretation of the Fifth Amendment showed just how hollow and self-serving the concept of freedom could be — in this case one person’s freedom literally being defined as another’s bondage. For that matter, most laws both restrict and secure freedom. Restrictions on murder, rape, and robbery, for instance, protect one’s freedom to not be killed, raped, or robbed but deny freedom to murderers, rapists, and burglars.

Taney’s ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1856) played into northern fears of what Salmon Chase called the “Slave Power Conspiracy,” a cabal of politicians, businessmen, and justices hell-bent on promoting slavery not just out west, but ultimately coercing northern states into re-legalizing it. King Cotton, it was said, “owned the press, pulpit, politicians and people” of the South.

Indeed, southern planters spearheaded by the Knights of the Golden Circle were looking to expand slavery into Latin America and the Caribbean, especially Nicaragua and Cuba (map above). Historian Walter Johnson argued that the future ambitions of slaveholders of the southern Mississippi Valley were even more focused on Latin America than Bleeding Kansas or the West. Dred Scott also swung southern politicians firmly in favor of national power over states’ rights. That may sound counter-intuitive at first but, rather than letting new western states decide slavery on their own, they wanted the national government to impose its interpretation of the Fifth Amendment everywhere.

Panic of 1857

Southerners thought the North was reeling anyway with a downturn caused by the Panic of 1857 that hurt the North more than the South. On the other hand, the northern population was growing faster, despite pro-slavery Democrats’ control of the Court, Presidency, and Congress. In fact, the Panic of 1857 was caused mainly by overly rapid growth in the northern economy and, in that way, was symptomatic of emerging northern strength. The downturn had multiple causes. Northern railroads used land the government granted them adjacent to tracks to finance mortgages they re-packaged and sold as bonds in Europe, that European investors dumped suddenly when it appeared that southern politicians would be able to disrupt the land grants. Abraham Lincoln, un-coincidentally, was actively involved as a lawyer and politician in helping the railroads maintain access to these grants in the mid-1850s. In addition, the side-wheel steamer SS Central America carrying a massive stockpile of gold from California sank in an Atlantic hurricane, disrupting the banking system.

Fallout from the 1857 Panic impacted the re-shuffling of parties that was going on already in the wake of Bleeding Kansas. Each party wanted a stimulus package to revive the economy, to borrow a modern phrase. Southern Democrats wanted to annex Cuba, to increase slave territory and import enslaved Cubans to Louisiana and Mississippi. Republicans wanted to give western settlers land and build them universities to go along with the railroad grants. Many northern Democrats and Whigs favored the GOP approach and defected, bolstering Republican numbers and hastening the regionalization of the new two-party system. Republicans were still a third party prior to the economic downturn and debate over what to do about it. The new two-party system of Democrats and Republicans emerged after Bleeding Kansas and crystallized in the wake of the Panic of 1857.

Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Taney’s ruling in Dred Scott was a direct challenge to this rapidly growing Republican Party, whose platform focused on blocking western slavery — similar to what Jefferson had tried but failed (by one vote) to do in western territories in 1784. The Court had just ruled that any restriction on slavery in western territories was unconstitutional, delegitimizing the Republican party’s main objective. Something had to give. That was the context of Abraham Lincoln’s un-retirement back into politics. Lincoln, a former Whig politician, returned to Illinois politics after Bleeding Kansas and Dred Scott, reborn as a Republican.

Lincoln challenged Stephen Douglas, the incumbent Democratic Senator who authored the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Douglas didn’t see much advantage in debating, but Lincoln goaded him into a series of long exchanges that made the 1858 Illinois senatorial race the most famous in history, and more famous historically than the presidential elections of 1852 and 1856. Each year, C-SPAN re-enacts the Lincoln-Douglas Debates. There were no microphones or megaphones so each candidate had to belt out their long half-hour turns followed by rebuttals, Lincoln in his native Kentucky accent. He challenged Douglas to reconcile free sovereignty with Dred Scott, that denied settlers’ right to restrict slavery. Douglas countered with his Freeport Doctrine that settlers should just ignore the Court, but that hardly sufficed as a permanent solution. Lincoln understood that, since state constitutions are drawn up during the territorial phase, the Dred Scott case was, in effect, denying states’ rights when it came to establishing free soil, despite Southern Democrats’ much-ballyhooed commitment to states’ rights.

Douglas also countered that Lincoln liked Blacks. Lincoln recoiled from that charge, reiterating that Blacks should never be able to vote or hold office and that, as much as any man, “he was in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.” But Lincoln also steadfastly supported Blacks’ right to work as free laborers and not be owned, saying “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy.” He was sensitive about that partly because of his own father sourcing him out for labor. He often called slavery the “theft of labor.” But Lincoln also said in the September 18th debate that differences “would forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.” Whether or not Lincoln endorsed that policy or was just offering a sobering appraisal is hard to say. He’d even defended slave owners early in his law career, but his views evolved over his lifetime. We don’t know if Lincoln was saying what he actually thought in the Douglas Debates; politicians often don’t. In any event, he seemed then to think the prospects of a functional, integrated society were bleak, which explains his stance on colonization, the relocation of the formerly enslaved. Lincoln credited Henry Clay in an 1852 eulogy with promoting colonization to help relieve planters of the potential “troublesome presence of free negroes.”

Meanwhile, though, Lincoln wanted to block the spread of slavery in the short term and seemed to hope for its ultimate extinction. In the Douglas debates’ most famous words, drawn from Mark 3:25, Lincoln said a “House divided against itself cannot stand. I believe that this government cannot endure permanently, half slave and half free. It will become all one thing or all the other.” The words echoed those of another Republican, William Seward, who talked of an “irrepressible conflict.” Seward later served as Lincoln’s Secretary of State. Both Lincoln and Seward thought an actual war could be avoided as historical forces would eventually eclipse slavery peacefully. Lincoln lost the 1858 senatorial race to Douglas — as it turns out, voters in southern Illinois did see him as too pro-black — but the campaign garnered the attention of Republicans looking for someone with frontier credibility to run for president in 1860. Lincoln’s 1858 senatorial campaign was one of the most fruitful losses of all time.

Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men

Lincoln’s formal stance, that he stuck with through the 1860 election until midway through the Civil War, was to support slavery where it already existed in the Southeast but not allow any further expansion — similar to what Thomas Jefferson tried and failed to enact further east in the mid-1780s. Lincoln opined, “If you had a barn full of rats, it wouldn’t be worth burning down the barn just to get rid of the rats; but if you built a new barn you wouldn’t go toss rats in it.” The rat analogy was meant to symbolize slavery, but for many northern voters, it could have just as well symbolized Blacks. After all, Free Soil states didn’t just outlaw slavery; they very nearly outlawed free Blacks.

In varying degrees, northern states denied free African Americans citizenship, restricting immigration and disallowing property ownership. Oregon’s exclusion of “all free negroes and mulattos” passed their legislature by an 8:1 margin in 1857. That same year, as the leader of Iowa’s colonization society, J.C. Hall said, “As long as they remain, they must be outcasts and inferiors. They can have no aspirations except as the objects of an unwelcome, hesitating and noisy charity.” It wasn’t just the warped, exploitive form of the South’s biracial society that alienated Northerners; they were grossed out by the fact that it was biracial to start with. If anything, it was even truer in New England than in the Midwest or West. New England had been mainly an Anglo society for a couple of centuries, similar to what the Ku Klux Klan wanted things to be like everywhere after the Civil War. When they looked to the South, New Englanders saw not just Blacks, but also an unseemly amalgamation of French, Spanish, Indians, and Whites who slept with Blacks. Tapping into this long-standing racial hostility, the Republican Party broadened its appeal by de-emphasizing abolition for morality’s sake, instead stressing the need to keep the West open for Whites — this, despite the fact that bona fide abolitionists, veterans of Bleeding Kansas, actually started the Republican Party in places like Ripon. The same phenomenon had played out when Indiana and Illinois debated their new state constitutions in 1816 and ’18, with anti-slavery factions appealing to racism. The problem with slavery for most Northerners was that it brought in Blacks who displaced white wage workers and plantation owners who displaced yeoman farmers. Salmon Chase’s Republican mantra of Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men really meant Free [White] Men. Among Free Soilers, opposing slavery was compatible with racism.

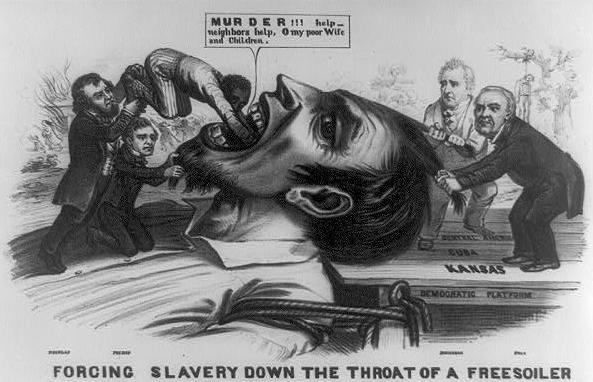

John Magee’s 1856 cartoon depicts a giant Free Soiler being held down by James Buchanan and Lewis Cass standing on the Democratic platform marked “Kansas”, “Cuba” and “Central America”. Franklin Pierce also holds down the giant’s beard as Douglas shoves a black man down his throat.

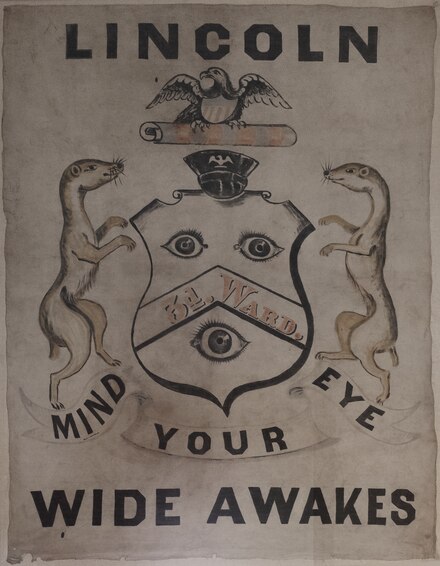

The 1856 Republican platform clarified that “all unoccupied territories of the United States, and such as they may hereafter acquire, shall be reserved for the white Caucasian race — a thing that cannot be except by exclusion of slavery.” The Civil War could be re-cast not as abolitionists vs. slaveholders, but as a collision of two incompatible types of racism. White Southerners saw Blacks as property or unpaid servants at best, bestowed upon them by a seemingly racist God. Presaging the 20th-century KKK, most Northerners wanted to keep the country bleached to preserve wage jobs for Whites. Integrationists they were not. One kind of racism had to give. To be sure, there were genuine white abolitionists who cared for the enslaved (even they usually supported colonization rather than integration), and they could join the Republican coalition too because it offered them the best chance of upending slavery. And there were half a million young progressive Wide Awakes, to boot, who guarded abolitionist speakers and, later, Abraham Lincoln (a vigilante secret service). But an overriding goal of the Free Soil movement was expressed most succinctly, fittingly enough, by a literature professor from Harvard, Charles Eliot Norton: “to confine the Negro within the South.” There was also a southern critique of slavery voiced by otherwise racist Hinton Rowan Helper, whose Impending Crisis in the South (1857) echoed Northerners, and Karl Marx, in pointing out that southern aristocracy blunted upward mobility for poor Whites — a line of criticism planters started calling “Helperism.”

The 1856 Republican platform clarified that “all unoccupied territories of the United States, and such as they may hereafter acquire, shall be reserved for the white Caucasian race — a thing that cannot be except by exclusion of slavery.” The Civil War could be re-cast not as abolitionists vs. slaveholders, but as a collision of two incompatible types of racism. White Southerners saw Blacks as property or unpaid servants at best, bestowed upon them by a seemingly racist God. Presaging the 20th-century KKK, most Northerners wanted to keep the country bleached to preserve wage jobs for Whites. Integrationists they were not. One kind of racism had to give. To be sure, there were genuine white abolitionists who cared for the enslaved (even they usually supported colonization rather than integration), and they could join the Republican coalition too because it offered them the best chance of upending slavery. And there were half a million young progressive Wide Awakes, to boot, who guarded abolitionist speakers and, later, Abraham Lincoln (a vigilante secret service). But an overriding goal of the Free Soil movement was expressed most succinctly, fittingly enough, by a literature professor from Harvard, Charles Eliot Norton: “to confine the Negro within the South.” There was also a southern critique of slavery voiced by otherwise racist Hinton Rowan Helper, whose Impending Crisis in the South (1857) echoed Northerners, and Karl Marx, in pointing out that southern aristocracy blunted upward mobility for poor Whites — a line of criticism planters started calling “Helperism.”

Raid on Harpers Ferry

John Brown, he of the broadsword in Kansas, wanted to stop slavery altogether, not just its expansion. It was time for him and a mere 22 of his followers to “take the fight into Africa,” their code word for the South (an illuminating term when one considers the preceding section). To that end, Brown raised funds from fellow abolitionists to arm a slave insurrection in the upper South. Mary Ellen Pleasant, who’d profited from the California Gold Rush (Chapter 16), contributed $30k, amounting to over a million dollars adjusted for inflation. Boston merchant Amos Lawrence, who financed the founding of the University of Kansas, also contributed a large sum, along with the “Secret Six.” The plan was to seize the Federal Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia on the Potomac River then distribute 100k rifles to enslaved workers for use against their owners.

Brown may have been a visionary, but planning wasn’t his forte. They didn’t even pack lunch. The first fatality, ironically, was a black porter named Hayward Shepherd who overheard their plan on the train and may have attacked them. Brown had no real notion as to how he was going to steal weapons from the U.S. military. Frederick Douglass, who otherwise advocated armed slave insurrections, expressed reservations and refused to participate. Even with a couple hundred pikes and Beecher’s Bibles (breech-loading Sharps rifles), Brown didn’t stand a chance. For one, he didn’t realize that there weren’t many enslaved people in northern Virginia, the reason 39 counties broke off to form Union-held West Virginia in the ensuing war. Most enslaved captives in northern Virginia were in coffles heading to the Ohio River on their way to the Deep South.

Marines led by Col. Robert E. Lee surrounded Brown’s men and some hostages they’d taken, including George Washington’s great grand-nephew, Lewis. J.E.B. Stuart approached them with a white flag offering to spare their lives if they surrendered, but Brown said he’d rather die inside. The Marines obliged and rammed open the door, eventually killing ten, including Brown’s sons Oliver and Watson. Another son, Owen, escaped. They captured the others, including John Brown. If Stuart and Lee’s names sound familiar, it’s because they went on to become famous Confederate generals in the Civil War. Confederates, in turn, also raided and took over Harpers Ferry during the war.

The morning they took Brown to the gallows, he wrote his final words: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Brown may have been crazy, arguably even a terrorist, certainly something of a lunatic, but he was right that slavery wouldn’t be abolished peacefully, and he stood for a cause most Americans would agree with today. Does that excuse his murders in Kansas? Does it exonerate him from being labeled a terrorist or fanatic based on the failed Harpers Ferry Raid? Historians and students have argued over the latter ever since, but it’s not the type of question that lends itself to a definitive answer. If one believes that war was the only viable solution to the slavery issue, then a case could be made that Brown helped speed along that process. Or, maybe he was just symptomatic of larger issues that were unfolding anyway, with or without him.

At the time, church bells rang for Brown in select parts of the North, especially New England, where he was seen as a martyr to the abolitionist cause. Julia Ward Howe’s The Battle Hymn of the Republic, later the Union’s anthem during the war, used music originally penned as “John’s Brown’s Body.” In the South, Brown seemed like a realization of their worst fears, evoking memories of Nat Turner’s Revolt in 1831. No amount of assurance from the Republicans distancing themselves from Brown assuaged those fears. The GOP even avoided nominating an abolitionist in 1860 because of Brown’s raid, though there was good reason for Southerners to suspect that Lincoln was a closet abolitionist. Lincoln, for his part, instructed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to not endorse him for that very reason. But all hope of congressional compromise evaporated after Harpers Ferry. Capitalizing on the Second Amendment’s original intent, militias formed and trained across southern states in reaction to Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry. These same militias morphed into the Confederate Army two years later. Brown drove the wedge deeper between the North and South.

Conclusion

Was John Brown right that slavery could only be jarred loose by violence? This is what Lincoln’s future Secretary of State William Seward implied with his 1858 “Irrepressible Conflict” speech. Or, as some historians have charged, did a “blundering generation” of politicians plunge the nation unnecessarily into a war that could’ve been avoided? White House Chief of Staff John Kelly got himself into hot water in 2017 by saying that the Civil War resulted from lack of compromise — partly because there had already been so many compromises preceding the war, but mainly because the blundering generation theory seems premised on slavery continuing in some form as part of a compromise. That’s likely why the theory is increasingly outdated in favor of the logjam idea, despite White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee’s defense that there is “pretty strong consensus…from the Left, the Right, the North, the South” that a lack of compromise caused the war. We can only say for certain that by the time the GOP nominated Lincoln for the 1860 election, all of America’s major institutions – mainline Protestant churches, courts, political parties, and the people themselves — were divided over slavery, though the reasons why they disagreed varied. Southerners also rejected compensation for freeing their enslaved workforce. One thing Northerners and Southerners of the 1850s would’ve agreed on if they’d hopped in a time machine to visit us would be their surprise at our reluctance to see slavery as the issue dividing them. Around half of modern Americans cite slavery as an influential cause of the Civil War, but the stumbling block is often more emotional than intellectual or, as we’ll see in the next chapter, the fault of local politicians influencing school curriculums and textbook publishers.

As the Mexican War was being fought, and Kansas was being settled, as Dred Scott was asking for freedom, as John Brown was trying to take over the Federal Arsenal, not a soul in sight was arguing over tariffs, economics, honor, or states’ rights, except insofar as they connected to slavery, though the latter three no doubt overlapped. Harriet Beecher Stowe didn’t stoke arguments because she favored the national government over state governments; in fact, she thought the reverse because she favored the right of states to defy the national fugitive slave law. Southern militias didn’t form to crusade against tariffs. All the major arguments of the 1850s had in common the “peculiar institution” at their core. As war was breaking out, all discussions about potential compromises concerned slavery. After the war started, negotiators from neither camp mentioned anything other than slavery. Ultimately, this was one issue — the only so far in American history — that couldn’t be settled through democracy and had to be decided on the battlefield.

However, as we’ll also see in the next chapter, the respective sides didn’t go to war for the same reason. The South seceded because they thought Lincoln’s election threatened slavery while the North fought initially just to keep the Union together, not to end slavery. For the North, the primary concern with slavery wasn’t moral, but rather that slavery displaced white wage labor and led to racial integration.

Saul Cornell, “The Lessons of a School Shooting – In 1853” (Politico, 3.24.18)

Matthew Karp, “In the 1850s, the Future of American Slavery Looked Bright” (Aeon, 11.1.16)

Rich Lowry, “There Are Certain Things The Supreme Court Can’t Settle (Slavery & Abortion)” (Politico, 5.5.22)

Joshua Zeitz, “Why You Should Be Worried About the Split in the Methodist Church [over LGBTQ]” (Politico, 12.9.22)

Clint Smith, “The [Real] Man Who Became Uncle Tom” Book Review (Atlantic, 10.23)

Karsten Fitz, “Commemorating Crispus Attucks: Visual Memory & the Representations of the Boston Massacre, 1770-1857” (JSTOR, Amerikastudien 2005) Log In w. ACC ID

Gal Beckerman, “Should We Still Read Uncle Tom’s Cabin“ (Atlantic, 9.23)

Danny Schraffenberger, “Karl Marx & the American Civil War” (International Socialist Review, Winter 2016-17)